|

|||||||

Opus 305 (February 13, 2013). The sensational and scandalous Al Capp is, at last, the subject of a biography based in large measure on papers and files not usually accessible; we review it at length, and we take a somewhat shorter look at the 2013 edition of the Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year under its new editor. We also sneer long and vociferously at the delusions about the alleged superiority of stickfigure funnies on the Web, discuss the ludicrous accusation of editoonist Bill Day’s “self-plagiarism,” and examine the supposed anti-Semitism of a recent cartoon by Brit cartoonist Gerald Scarfe. All that and even more, as you’ll see by scanning the list of contents below. Before that, though— I should mention that I have a page in Facebook where I post something 3-5 days a week. No long essays. Pictures, mostly—some are my cartoons; some are favorites I have discovered hither and yon in my travels through dusty tomes. Be sure to ’toon in. And now, here’s what’s here, by department, in order—:

NOUS R US George Washington’s Birthday Man Jailed for Porno Comics Wasserman Quits Globe Trove of Comix Found New Yorker Covers

ANTI-SEMITISM IN SCARFE

COPYCATTING and PLAGIARISM Bill Day

Further Adventures of Maggie CBG Thompson

FATE OF THE FUNNIES Part One: Stickfigures on the Web (Doonesbury’s Slam?) Part Two: King Features’ Prices

EDITOONERY Motto from Mister Dooley

Newspaper Comics Page Vigil Beetle, Zits, Garfield, Jump Start, Cows in Blondie, Free Range

BOOK MARQUEE New Seuss Book Is Reprint of an Old One

BOOK REVIEWS Al Capp Biography Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year, 2013 Edition

PASSIN’ THROUGH: Chris Cassat Al Stine

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits BUT FIRST, A CELEBRATORY INTERLUDE—:

Poor George’s Dilemma As We Approach His Alleged Birthday As your resident paranoid, I'm doubtless in a better frame of mind to appreciate George's Dilemma than most, and it is therefore logical that it should fall to me to bemoan his fate on this otherwise festive occasion. (I'm also the resident bemoaner and that makes it all the more fitting that I undertake The Task That Everyone Else Shies Away From.) My calendar says it’s George Washington's birthday on February 18. But it isn’t. It’s merely the third Monday in February. The calendar is lying. Ironic— isn't it?—that the birthday of George Washington, fabled as the kid who couldn't tell a lie, should be celebrated on February 18 as the consequence of a monstrous mendacity. But that is the merest tip of the iceberger, folks: it gets worse. Even if we wait four days and try to celebrate his birthday on the 22nd of February, we'd still miss the mark. George wasn't born on the 22nd of February either. Sad but true. The perpetration of the hoax by which we've all been hornswoggled began (believe it or not) with old Julius Caesar, who, as far as we know, didn’t even know Washington. Before Julius was stabbed in the back, he devised a calendar that was 6 hours too long every year. By 1582 this little miscalculation had resulted in shoving the year out of sinc with the seasons so far that the vernal equinox had slipped back to Ground Hog Day. Something had to be done, or we'd wind up mowing our lawns in two feet of snow. Pope Gregory XIII, after several sleepless nights, hit upon the solution: he suppressed 10 days. That's right. Popes could do anything in those days. He woke up one morning and instead of saying Happy Valentine's Day, he said it was February 24th. You can imagine the broken hearts at that. Everyone had to save their Valentines until 1583. Except in England. Thanks to Henry VIII (who had been dead a scant thirty years or so at the time), no one listened to the Pope anymore. They went merrily on their way with a slipped sinc in their equinox for nearly 200 years. Finally, by 1752, England's calendar was 11 days behind the Continent's. (So if you were in France and wrote a letter to a friend in England, he’d probably get the letter before you wrote it.) It was impossible to conduct a decent war under these conditions, so England (at last) followed Pope Gregory's lead and suppressed 11 days (skipped from September 29 to October 11, I think it was) and thereby caught up with the rest of the world. The British Colonies in this hemisphere did the same thing shortly thereafter. And everyone born before 1752 (and that included Poor George) had to add 11 days to their birthdates in order to keep up. (You can imagine the consternation among the parents of those scheduled to be born between September 29 and October 11, 1752; in fact, given the suppression of all the dates between September 29 and October 11, exactly no one was born on any of those dates, and a lot of birthday cakes had to be auctioned off at stale bread sales.) Yep: George was really born on February 11. But we've uncovered only part of the catastrophe. Before England did the 11-day Gregorian Hiccough, New Year's Day fell on March 25. After 1752, we changed years on January 1. Since George's birthday fell between these two dates, he changed birth years as well as birth days. (The alternative was to add a year to his age, and we know that anyone vain enough to put up with bad fitting wooden false teeth wasn't about to be any older than he had to be.) It's distressing to imagine the consequences of all this for George's psyche. Think of the identity crises he must’ve gone through. When just a lad of twenty (or was it twenty-one?), his birthday was uprooted and flung around the calendar. It gave him such a bad temper that he started a revolution as a way of striking back at the British. The only way to calm him down was to name a city after him. Then there's the Washington Monument. The Washington Monument is probably the most apt of memorials to Poor George. I'm sure that after all that happened to him, it more accurately represents his state of mind than any other kind of structure—that colossal finger, gesticulating rage and disdain to the world.. So George is resting in peace these days, even if Washington is still celebrated as the citadel of falsehood. It’s probably a good thing to keep in mind when visiting the nation’s capital. Or a voting booth. Oh—almost forgot—George Washington wasn't the first president of this country either. But that’s another story. ...

MORE OUTRAGEOUS ATTACKS ON PRIVACY AND INDIVIDUAL LIBERTY From the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund: In Missouri, Christjan Bee, 36, was sentenced recently to three years in federal prison without parole, followed by five years of supervised release because authorities found on his computer comics that the government characterized as “pornographic”—i.e., depicting “children engaging in sexual behavior.” Prosecutors assert the material “is categorized as obscene and therefore illegal,” despite the fact that the material was not tried in court under the Miller obscenity test. CBLDF was not involved in the case but its Executive Director Charles Brownstein was nonetheless concerned, saying: “At this time, little is known about the material Bee pleaded guilty to possessing. Based on the government’s characterization of the material, I remain unpersuaded that it is legally obscene under the Supreme Court’s Miller obscenity test. It is also distressing that Bee is being sent to prison for mere possession of obscene material, where there is precedent that the court’s power ‘does not extend to mere possession by the individual in the privacy of his own home.’ Even absent full specifics on the material Bee pleaded guilty to possessing, this is, on many levels, a distressing case.” It is, in fact, a grotesque perversion of justice. The Justice Department states that a forensic examination of Bee’s computer produced “a collection of electronic comics, entitled ‘incest comics.’” The comics are described to contain “multiple images of minors engaging in graphic sexual intercourse with adults and other minors.” The DOJ asserts that the comics lacked serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value — areas that would have been tried if Bee’s case went before a jury. Brownstein said the government’s description “may be enough to make the work distasteful, but that’s not enough to deem a work obscene. The government’s description can easily describe a variety of comics that possess artistic and literary merit, including Robert Crumb’s ‘Joe Blow,’ a story I frequently lecture about because it was the subject of a badly reasoned obscenity conviction in the 1970 case People v. Kirkpatrick. It could also apply to any number of meritorious works of comic art, including the works of Alan Moore, Ariel Schrag, Phoebe Gloeckner, and others. Distasteful or disturbing subject matter does not make work obscene.” Noting his disappointment that Bee did not reach out to CBLDF, Brownstein concludes: “We’re alarmed that the government continues to prosecute readers of comics at the cost of taxpayer dollars that would be better spent going after criminals who prey on and abuse real children. The key lesson here is that when a First Amendment emergency strikes, make CBLDF your very first call.”

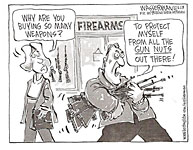

NAME DROPPING & TALE BEARING In September 2010, Borja Garcia noted via tcj.com that in Spain there was then a comic strip cartoonist who has been drawing the same strip, Don Celes, for 88 years—goes by the name Luis del Olmo Alonso; “in the beginning, I think it wasn’t a daily strip.” Don Celes is the Beetle Bailey of Spain, sez here—started in 1945, and as far as I know, both Olmo and Don Celes are still going. If so, that’s 90 years for Olmo, who long ago beat an earlier record set by Australian cartoonist Jim Russell, who died in 2001 after having drawn The Potts for 62 years. Russell’s record was busted last fall by Mort Walker, whose Beetle Bailey started in September 4, 1950. A highly fictionalized Walt Disney is the protagonist in an opera written by America’s “most famous living composer,” Philip Glass. In his “The Perfect American,” Disney, as Lisa Abend puts it in Time for February 4, is “crippled with anxiety about his legacy and fighting desperately against his impending death. ... After a lifetime spent creating illusions, he finds himself no longer able to stave off reality ... and rages against the end.” The opera opened in Madrid on January 2. Said Rancid Raves correspondent Bill Black, who sent me a clipping: “This is bizarre. Maybe someone will write an opera about Walter Lantz and start a trend.” EgoBoo. Among my books, the second to be published, The Art of the Comic Book, is the bestseller at 5,334 paperback copies as of June last summer; next is The Art of the Funnies at 3,513 in paperback. Then probably Meanwhile, my Milton Caniff biography; I think it’s sold more than 3,000 copies. Finally, Accidental Ambassador Gordo with 2,785 in paperback. Paltry numbers in the book publishing racket, I realize, but impressive to me and my relatives. In Boston, editoonist Dan Wasserman has left the Boston Globe. As reported by Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist, Wasserman will work out of his Globe office and will produce a local cartoon for the paper’s Sunday edition, and he will continue doing cartoons for syndication by Tribune Media Services, which the Globe typically uses several times a week. But he’s no longer “on staff.” Calling this arrangement a “buyout-leaseback,” Wasserman also acknowledges the economic impetus, saying, “More freedom for me, less overhead for the paper.” There are now only 53 full-time staff editorial cartoonists still standing. Here’s a sample of Wasserman.

A TROVE OF UNDERGROUNDERS CGC, the comic book grading company that panders to investment addled comics fanaddicts, has acquired lately what is called “the Haight-Ashbury Collection,” consisting of almost 500 underground “comix” and magazines. From a press release we learn: The collection is named after the section in San Francisco where the hippie subculture reigned in the mid-to-late 1960s. “This is a rare and exceptional collection of underground books that has never been seen before in such high grades. The pages are in beautiful condition and the covers have bold colors. CGC is thrilled to be a part of the first underground pedigree to hit the market,” said Paul Litch, CGC Primary Grader. Among the first few books graded by CGC are Death Rattle No.1, CGC 9.8; Zap No. 3, CGC 9.2; Zap No. 4, CGC 9.4; Arcade No.1, CGC 9.8, Freak Brothers No.1, CGC 9.2; Snatch No. 3, CGC 9.8 and American Splendor No.1, CGC 9.6. The comics were collected by a single individual from San Francisco starting in 1970. After obtaining his first batch of underground comics, the owner started putting aside new issues every week for the next five to six years, never reading them. Although he was not a comic collector, he collected other items and knew it was important to store them carefully. From 1976 to 1981 he added a few comics and associated publications to his collection, but nothing like the early years. Late last year the owner came across the comics he put away decades ago and decided to sell them. As a result of being stored meticulously, the books have fantastic color and look like they were printed yesterday, CGC said in a release. Howard Greber, aka Eggs Ackley on the CGC Chat Board, contacted the owner and purchased the entire collection. Greber has been collecting and selling comic books since the mid-1960s and currently specializes in the underground “comix” genre.

NEW YORK CRAZE It’s that time of year again: every year, as we approach the end of February, The New Yorker publishes, for the umpteenth time—usually—the Rea Irvin drawing that adorned the magazine’s inaugural issue February 21, 1925. But this year, for only about the tenth time, the cover drawing, while echoing Irvin’s iconic portrait of a bemused but bored boulevardier inspecting a butterfly through his monocle, is something different. Lee Lorenz, a long-time cartoon editor of the magazine, told me that they kept using the Irvin drawing every year because they could never thing of an alternative that would be as significant. So on and on and on. That stopped in 1994 when the magazine’s new editor, Tina Brown, put Robert Crumb’s drawing of a modern boulevardier—a slacker—on the cover. Outrage ensued among longtime New Yorker perusers. But Brown kept on for a couple more issues; finally, though, she surrendered and went back to Irvin. For a few issues. Then she left and David Remnick assumed the throne. He, too, kept on with Irvin’s picture. For a while. And

then, subsequently, an alternative anniversary cover strategy was developed:

just mimic Irvin’s classic pose and poseur, giving the latter somehow

contemporary garb or accouterments. “Greiner, who used to have a studio in Williamsburg, has been known to ride his bike around Brooklyn. He has a beard, but adds, ‘I’ve had a beard for as long as I remember.’ He has no tattoos.” I don’t know enough about Brooklyn or the beards thereof—or the tattoos—to properly appreciate Greiner’s accomplishment. But here are some of the hundreds of submissions to this year’s Eustace Tilley Contest (Eustace Tilley being the name eventually given to Rea Irvin’s dandy by the advertising department, recruiting new subscribers; Tilley had no name at first).

WHAT? ANTI-SEMITISM? WHO? ME? Not Bloody Likely THE CARTOON

AT YOUR EYE’S ELBOW was published in the Sunday Times of London on

Sunday, January 27, in recognition of the re-election the previous week of

Israel’s prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a man not known for his

conciliatory efforts with Palestinians and whom, consequently, the cartoon

attacks for continuing to “cement the peace” in his usual fashion, deploying an

image that references the “fence” or “wall” that Israel has erected between

itself and the West Bank in order to stop suicide bombers from entering Israel. Immediately, outraged Jews in Britain and everywhere else accused the Times and the cartoonist, Gerald Scarfe, of anti-Semitism, heinous enough anytime but even more so in this instance since it occurred on International Holocaust Memorial Day. At first, the Times defended its decision to publish the cartoon, saying it was “aimed squarely at Mr. Netanyahu and his policies, not at Israel, let alone at Jewish people. It appeared yesterday because Mr. Netanyahu won the Israeli election last week.” Martin Ivens, the paper’s acting editor, quoted in the New York Times, noted that the Times “has long written strongly in defense of Israel and its security concerns.” But it was too late for rational response. Rupert Murdoch, owner of the Sunday Times, was compelled to take to twitter on Monday, January 28, saying that cartoonist Scarfe, “has never reflected the opinions of the Sunday Times. Nevertheless, we owe major apology for grotesque, offensive cartoon.” The next day on a BBC radio broadcast, the Guardian’s Steve Bell, a cartoonist Scarfe’s equal in gross and perverted imagery, responded during in a heated on-air discussion that when Scarfe depicted President Bashar al-Assad of Syria in a similarly confrontational light there had been “not a squeak” of criticism. By then Scarfe, who has been failing to reflect the Sunday Times’ opinions in cartoons since 1967, had already apologized. The Jewish Chronicle quoted him as saying he “very much regrets” the timing the cartoon’s publication. In a message to the newspaper, he “said that he had not been aware it was Holocaust Memorial Day.” On this side of the Atlantic, the Baltimore Sun’s editoonist, Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher, who lived and worked in England for years and is still the Economist’s cartoonist, said: “Anyone who has been watching Scarfe cartoons over the last 40 years will know this cartoon is standard fare for the artist. Strong caricature, powerful imagery, a spattering of blood and, of course a wall. [Scarfe is notorious in England for his illustrations for Pink Floyd’s 1979 album The Wall and for the 1981 feature film it inspired.] “The cartoon,” KAL continued, “was both typically Scarfe and entirely fair commentary. The furor is just another example of an aggrieved group thinking they are being singled out for abuse in a cartoon. I was delighted to see Steve Bell articulate a strong pro-cartoon rebuttal. Here in the U.S. we are accustomed to the muscle of the Jewish lobby and its ability to influence the public discourse. What surprised me in this instance was the power the U.K. Jewish lobby was able to assert over Murdoch.” I agree. The Jewish community around the world has developed a super-sensitivity, it seems to me, about such slights, both real and imagined. A cartoonist who draws any sort of big-nosed character in connection with Israel is bound to be accused of anti-Semitism by one or another of the numerous anti-defamation agencies established, seemingly, for the express purpose of seeing offense where none is intended and then protesting loudly. At the same time, I realize acutely that any people whose history includes a wholesale effort by depraved racist bigots to wipe them out of existence—an effort largely ignored by the rest of the world while it was taking place—is entitled to make a fuss any time the sentiment that permitted the Holocaust surfaces again. And in Britain, that tendency apparently has deep roots. Scarfe’s unfortunate use of bloody imagery raised immediately the spectre of the ancient canard about Jews—the so-called “blood libel,” a term denoting medieval superstitions falsely accusing Jews of using the blood of gentile children in religious rituals. The cartoon thus reflected a “vile piece of anti-Semitism” of the sort that is common in cartoons in today’s Arabic newspapers in the Middle East. The Jerusalem Post even asserted that the blood libel notion originated in England—in 1144 in Norwich. And Jennifer Lipman, an editor at Britain’s Jewish Chronicle, remembered that “perhaps the most famous example of a blood libel occurred in thirteenth century Lincoln [in England], when 18 Jews were hanged after being falsely accused of the murder of a local boy. So it's not exactly baffling that a depiction of flowing blood, next to cartoons of innocent people being attacked by the leader of the Jewish state, might raise eyebrows among anyone with a basic awareness of history.” That Jews, particularly Israelis, might see an anti-Semitic conspiracy lurking in Britain is even more understandable in the light of the events surrounding the formation of Israel after World War II. Britain, we recall, had “the mandate” to govern or oversee the governing of Palestine, out of which Israel was formed in 1948 by a United Nations action. But Britain withdrew from Palestine shortly after the U.N. declaration, leaving the new Jewish state defenseless against the enraged Arab world that immediately invaded with superior military force. That Israel survived and was even victorious in this historic confrontation is one of the luminous aspects of the nation’s history, a history in which Britain appears in a less than favorable light. So why wouldn’t Jews feel that the British look upon them with disdain? At the Jerusalem Post, the Scarfe incident seems a typical episode of anti-Semitism, the paper seeing prejudice even in the cartoonist’s apology: “Most anti-Semites nowadays are remarkably practiced in accompanying their invective with such instant disclaimers—by now an expected part of the pattern. It is politically incorrect to even hint at their thinly disguised anti-Semitism. That immediately turns them into the muzzled good guys and the protesters into loathsome Jews seeking to silence yet more righteous critics of Israel with their doomsday weapon—charges of anti-Semitism. ... This diabolical yet prevalent deformation of perceptions confers on all anti-Semites the freedom to slander, while denying Jews the right to speak the truth. “It is a foolproof arrangement,” the Post continued: “Jew-revulsion now masquerades behind inflammatory anti-Israel and pro-Arab propaganda, whose disseminators inevitably deny anti-Semitism. Their favorite ploy is to present Israel-bashing as just deserts for the Jewish state's policies. Post-Holocaust circumspection has bred cleverly camouflaged anti-Semitism—not less dangerous or less in-your-face but more cunning and deceptive. Scarfe is only one of many. The British establishment, which defends him on the grounds of ‘freedom of expression,’ would have been scandalized had anything similar smeared Muslims or indeed anyone of Asian or African ancestry. In their case it would have been incitement to hate.” The Post went on to recall “an eerily comparable British precedent for Scarfe's vulgar defamation, published exactly 10 years ago.” This was a cartoon by the Independent’s Dave Brown, who depicted a naked Ariel Sharon devouring a Palestinian baby, with a "Vote Likud" ribbon functioning as his fig leaf. Another blood libel, much more obvious than Scarfe’s. Said the Post: “Not only was Dave Brown's obscenity in the Independent not denounced, but it gallingly went on to win the Cartoon of the Year prize at the British Political Cartoon Society's annual competition.” The Post concludes its reaction to the Scarfe incident by saying: “Scarfe's distasteful cartoon is not a justifiable response to Israeli policy because it miserably fails Jewish Agency chairman Natan Sharansky's ‘3-D test.’ Judeophobia must be suspected when purported criticism slips into demonization, delegitimization and double-standards. Scarfe resorted to crude demonization, delegitimized the Jewish state's right to even passive self-defense (the fence) and evinces gross double-standards in ignoring the genocidal atrocities perpetrated by Israel's enemies.” Looking at Scarfe’s cartoon, it’s difficult to discern all three of the D’s. Demonization maybe, but scarcely delegitimization. And no editorial cartoon is ever likely to present at the same time both sides of an argument, so by the reasoning of the 3-D test, all editorial cartoons are exercises in double-standards. Still, it’s educational in the extreme to learn about the 3-D test. Another British cartoonist, Martin Rowson, who freelances to the Guardian and the Independent with cartoons as scathing as Brown’s and Scarfe’s (Rowson habitually depicts prime minister David Cameron as a spoiled brat in beribboned Lord Faukntleroy duds), writes in the Guardian as another oft-attacked practitioner, saying: “Scarfe’s Netanyahu cartoon was offensive? That’s the point.” He continues in the same vein: “If, like me and other cartoonists, you've produced cartoons critical of the actions of the state of Israel and then received thousands of emails, most of which read ‘Fuck off you anti-Semitic cunt,’ you tend to get a bit jaded. But over the years I've received similar responses—and worse, including death threats—from Muslims, Catholics, U.S. Republicans, U.S. Democrats, Serbs, atheists and the obese, as well as from supporters of Israel. After a while, the uniformity of the response can tempt you into thinking that this is all contrived and orchestrated, and certainly a lot of it is. “In the long shadow of the Holocaust,” he continues, “perhaps it's just about understandable—if not forgivable—that each time I drew Ariel Sharon, a fat man with a big nose, as being fat and having a big nose, it was therefore considered reasonable for me to be equated with mass murderers. “The responses, though, probably have more to do with the nature of the medium than its content. Visual satire is a dark, primitive magic. On top of the universal propensity to laugh at those in power over us, cartoons add something else: the capacity to capture someone's likeness, recreate them through caricature, and thereby take control of them. This is voodoo—though the sharp instrument with which you damage your victim at a distance is a pen. None of this is benign. It's meant to ridicule and demean, and almost all political cartooning is assassination without the blood. “But add to that the way we consume this stuff and you get the perfect recipe for offense. In newspapers, cartoons squat like gargoyles on top of the [opinion] columns, and while you nibble your way through the columnists' prose for several minutes, you swallow the cartoon whole in seconds. The internet has also changed things. British cartoonists find their work being consumed, via the web, by people in nations who haven't had more than 300 years of rude portrayals of the elite.” Asked by Americans offended by his disrespectful portrayals of U.S. presidents how he’d feel if American cartoonists dealt similarly with British royalty, Rowson remembered James Gillray’s 18th century depictions of George III shitting on the French fleet. “Indeed, in the mid-1780s, the French ambassador warned Versailles that Britain was teetering on the verge of another revolution, 150 years after they'd last cut off their king's head. His evidence? The kiosks stretching down the Strand, all selling satirical prints depicting the royals in the most disrespectful and disgusting ways imaginable.” As for Scarfe, “he, like the rest of us, is there to offend everyone.” And at the Independent, Lipman, guesting from the Jewish Chronicle, delivers what I hope is the final verdict—a measured reaction. She begins: “What is anti-Semitic is always unpleasant, but what is unpleasant is not always anti-Semitic. That was my take on Gerald Scarfe's now infamous cartoon. ... As political cartoons go, it's not much for subtlety; the clear message is that the Israeli leader is an obstacle to peace and responsible for vast amounts of Palestinian bloodshed. “Plenty of historic bloodshed has had nothing to do with Jews,” she continues, “and cartoonists like Scarfe are known for pushing the boundaries of taste. Scarfe's drawing, while undeniably unpleasant—and hardly a nuanced depiction of the political reality (where is Hamas in this picture?)—is not to my mind anti-Semitic.” The chief difficulty with the Scarfe cartoon, she says, is timing. “Scarfe may well not have known when the cartoon would appear, as he has claimed, but the [Sunday Times] editor could not have been blind to the date—after all, the paper's explanation of the inclusion points to a feature criticising Holocaust-denier David Irving in the magazine of the same date. ... I do not believe the Sunday Times is in any way ant-Semitic, or that Gerald Scarfe is. But the cartoon is still deeply, deeply unpleasant.” Undoubtedly. But Scarfe has made a career out of such images. In 1974, he marked the resignation of disgraced President Richard Nixon by drawing him wiping his butt with the American flag. And Britain’s prime minister Margaret Thatcher earned Scarfe’s special vehemence: he drew her as a battleaxe, a blind atomaton and a bloody-fanged pterodactyl. “I would always draw her as something acerbic and cutting, like an axe or a knife,” he told BBC News in 2008. “It’s great fun transmorgrifying politicians into other objects.” In any event, Bibi Netanyahu is likely to be seen as cementing a wall against peace for some time hereafter. And not without justification.

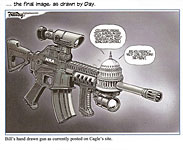

COPYCATTING AGAIN Accusations of plagiarism, appropriating the work of another and passing it off as your own, are once again inflaming the multitudes who watch what editorial cartoonists are up to. The most recent uproar, however, was stirred up by something quite different. Bill Day, who has won numerous awards for his editooning, used a picture of an assault rifle as the principal visual element of a cartoon in which he depicted the capital building as a part of the weapon. The message: Congress is a part of the gun control problem. Day presumably drew the building but, as it turns out, not the gun, a representation of which he found on the Web and appropriated—believing it was a generic photograph and not, as it happened, someone’s rendering of the gun. Caught, Day re-did the cartoon, substituting his own drawing of the rifle for the one he’d imported.

Why stealing a photograph would be somehow more permissible than stealing a drawing is an issue the ensuing brouhaha avoided. Regardless, artists presumably have been borrowing anonymously created images from the Web for some time, willy nilly. Presumably, the borrowed images are usually altered (if not entirely drawn or redrawn) for the “transformative” purpose of helping to convey a cartoon’s message. The Web is a vast resource—a morgue of unmatched dimensions—and the temptation is great. The sin was compounded in Day’s case by his being the recipient of donations intended to enable him to keep his home while continuing to draw editorial cartoons. Day was budget-cut three years ago from the Memphis Appeal job he’d held for more than a dozen years. Since then, he’s been working part-time jobs during the day and freelancing cartoons by night (between 9 p.m. and the wee hours, he says). His editorial cartoons have been syndicated by Cagle Cartoons, whose proprietor, Daryl, launched an Indiegogo campaign to raise money for Day, over $40,000 last I looked. So here is a guy accepting largesse from his readers and colleagues while he steals images from others. Suddenly, a sense of betrayal took possession of the so-called minds of Day’s brethren, inflaming the outrage among the inky fingered fraternity, which began denouncing Day in loud derogatory terms—ignoring the achievements of a 30-year career and a trophy shelf of awards. Borrowing others’ images, however, was not the extent of Day’s transgression. It was found that he’d also been borrowing from himself—a dubious crime laughably dubbed “self-plagiarism.” More like re-cycling. Day re-used dozens of his own cartoons, changing minor visual aspects of them and offering them for sale again. And, apparently, again and again. Each alteration changed the target in some way. That, however, was not change enough for those who decried Day’s economies.

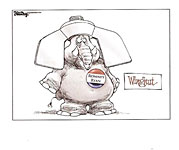

As

you can tell, I was not as outraged as many. I thought of Day slaving away at

his chosen profession every night from 9 p.m. until the wee hours of the next

day. I thought of his ingenious devising of the “right wing nut” emblem of the

Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm’s Tea Party subdivision. I thought of the daily deadline that most editoonists face, the pressure to produce by clock as much as by inspiration. I thought of the number of cartoons I’ve seen of a husband and wife on a couch watching tv and commenting upon what they’ve just heard. I thought of the number of cartoons I’ve seen of a pollster asking someone, usually a couple at the door of their domicile, a question to which they respond with a politically savy (or politically ignorant) quip. How much originality is on display in such tired tableaux, repeated again and again? Leaving aside that the cartoonist had to labor to produce a different drawing for each of these boringly repetitive pictures, Day’s recycled images don’t seem such an affront to morality as the shouters and proclaimers are shouting and proclaiming. In fact, devising new ways of using an image bespeaks a somewhat greater inventiveness than drawing a man and a woman seated on a couch watching tv. In short, I think Bill Day got trampled and didn’t deserve it. The tools of technology have enabled cartoonists to take shortcuts in drawing that were impossible a generation ago. The definition of plagiarism remains the same, but, if Day’s fate is any guide, that definition is now in a transformative stage.

CODA While the dust was settling on the stomping ground of Bill Day, cartoonist Elena Steier observed that “cartoonists have a bunch of different words for plagiarism: swiping, switching, cloning, pastiches, homages, appropriation, and probably more that I haven't researched on wikipedia.” She added that “it's like the Eskimos and their many words for snow”; the more words for a single phenomena, the more common the phenomena. “If nothing else,” she concluded, “that should tell you that everybody has higher standards than we have.”

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES Of Fandom’s Den Mother Emeritus THE INESTIMABLE MAGGIE THOMPSON, erstwhile senior editor of the Comics Buyer’s Guide before it was unceremoniously defuncted last month by its private equity firm owners, continues in fannish activity (as she would say) by contributing to Comic-Con International’s Toucan Blog, her own blog at MaggieThompson.com, and, most recently, to Gemstone Publishing’s email newsletter, Scoop, with a column called “Turning Points.” Said Steve Geppi, President and CEO of Gemstone Publishing: “I am very happy to welcome Maggie Thompson to Scoop. She has been an Overstreet Advisor for years, but even before her tenure began at CBG she and her late husband, Don, had been making tremendous contributions to fandom by documenting our history. And she’s never stopped! We are honored that she has chosen us as one of the outlets for her post-CBG career.” To which Robert M. Overstreet, Publisher of Gemstone Publishing, added: “Maggie Thompson has been correctly recognized as a treasure to the comic book world for many years. I was personally very happy when she formally became an Overstreet Advisor, and I’m even happier to have her regularly contributing to Scoop.” Said Maggie: "In the half-century since comic book readers began to come together in their own pop culture field, many of us who grew up on comics stayed as adults to celebrate, study, and build that field. An integral strength of today's world of comics is that Steve Geppi, Bob Overstreet, and their staffs have built an environment in which fans, professionals, and scholars alike enjoy the art form, each to their own tastes. It's a rare treat for me to have been offered the opportunity to participate in what Scoop offers its audience." Judging from the first column, which will run weekly hereafter, “Turning Points” will list significant dates in comic book and pop culture history, ranging from births and deaths to first appearances and sea changes in the industry. “Having Maggie Thompson on board Scoop is really a grand bit of wish fulfillment,” said J.C. Vaughn, Associate Publisher & Executive Editor of Gemstone. “We’ve had a great relationship for years, most of which I’ve spent simply in awe of the amount of knowledge she possesses. And in typical fashion, she turned in her first four columns at the same time and has already started on the next.” Scoop is published each week, generally on Friday, by Gemstone Publishing, Geppi’s Entertainment Museum, Hake's Americana & Collectibles, Diamond International Galleries, and the Fandom Advisory Network.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS “How much do we know, really, about facts?”—Bill Maher “The ripple effect needs to start somewhere.” —Dunno

THE FATE OF THE FUNNIES: PART ONE An Admittedly Hysterical (in the Psychological Sense) Rancid Raves Diatribe It’s been coming at us for quite some time. The death of good drawing. It started, regrettably, with James Thurber at The New Yorker. People managed to convince themselves that his pitiful scrawls were drawings, that they represented art instead of mere ineptitude. Charles Schulz continued undermining public perception with Peanuts—although in Schulz’s case, the confidence he deployed in rendering the simple linework displayed an elegance that imparted to the result at least a persuasive aspect of artistic ability, a definite cut above Thurber. There’s something streamlined about Peanuts’ simplicity. But Schulz’s success with simplicity opened the door for other cartoonists whose ability to draw, judging from their endeavors, was nearly nonexistent. The early years of Garry Trudeau on Doonesbury, f’instance. And after that, a deluge. But the tsunami hit with the Web. Web comics are, with a few shining exceptions (Sinfest most notably), purely execrable. That would be bad enough in itself, but then here comes explication—intellectual justification— for the execrability. The offal is being explained as something highly desirable. The

most notable of the latest examples of this offense to sense takes place in Time’s February 11 issue. Therein, Adam Sorensen writes of several web comics,

concentrating upon the dubious success of Matthew Inman, creator

(although it pains me to use that term to describe what he does) of Oatmeal, a

web comic that features the artistry of the compass, the ruler, and the French

curve. Now that’s funny. Idiotic but funny. And I submit that it’s banal utterances like that, with which Inman’s impoverished attempts at drawing are oft festooned, that make Oatmeal popular. Not the art itself. But funny as such illogical extremities are, they become even funnier when coupled to pathetic drawings. Cartooning has always been about words and pictures in concert. But with Oatmeal, the verbal-visual blend barely takes place. The words do not explain the pictures or vice versa, as they do in traditional cartooning—the blending making a comedic sense that neither words nor pictures make alone without the other. Instead, in Oatmeal the verbal stands apart from the visual (and vice versa), each idiotically quite independent of the other, their mutual independence making each even more idiotic. And yet in tandem, each idiocy makes the other funnier. But that’s not the reason for my complaint here. No, what’s genuinely offensive is the attempt by Inman and others to explain—to justify—their malodorous ineptitude. Sorensen is a willing participant in this fraud, saying: “Inman believes that the doughy characters he draws with a keyboard and mouse in a basic Web-design program are more relatable than his own likeness. ‘It’s funnier because when you see them, you project your own character into it.’” And others flock to agree. Says gadfly Ted Rall: “The simpler the style, the more people can relate to them.” Time accompanies its article with illustrations from two other web comics—Randall

Munroe’s xkcd, a stick-figured enterprise, and Dinosaur Comics, for which Ryan

North supplies different dialogue for clip-art dinosaurs that have remained

precisely the same, panel by panel, for over ten years, a mind-numbing

accomplishment in audacity albeit not artistry. Within a week of Time’s arrival in my mailbox, here comes the February issue of Editor & Publisher with an article about “comics journalism” by cartoonist-reporter Rob Tornoe, who quotes Erin Polgreen, founding editor and publisher of Symbolia, a new iPad magazine “taking a unique approach to journalism—telling stories exclusively through the use of sequential art.” Saith Polgreen: “There’s an immersive element to comics that makes it easy for a reader to identify with the subject at hand. When you simplify an image and render it to its essentials, you make it a lot easier for people to draw parallels to their own lives and experiences.” What unadulterated balderdash. What unrequited horse pucky. What a load of crap. Intellectual hogwash meant to razzle-dazzle us with high fallutin’ verbiage so we’ll overlook the absolute absence of drawing skill on display in the visuals. It’s an attempt to justify in pseudo philosophical terms something too trivial for notice otherwise—namely, the so-called art of most web comics. Simple

drawings make it easier for people to “relate” to them? As if simple drawings

were superior to more complicated ones as communicative maneuvers. And here we

resort to the adjacent visual aids for elucidation. Yes, there’s an immersive aspect to visual art that draws viewers into the pictures. People become involved with whatever the pictures are depicting. But it’s the visual aspect—a pictured reality—that makes the art immersive, not simplicity. Well, not simplicity in the stick-figure extreme. All visual art simplifies through the process of selection: selecting what to draw simplifies the visual aspect of reality. But simplification taken to the extreme of stick-figure visuals does not make the picture more relatable than all pictures generally are. Simple stick-figure visuals may be more engaging: after all, to understand them, the viewer must spend several minutes trying to figure out what the sticks represent. We have to work harder to understand, and the work is, perforce, engaging. Engaging but not relatable. A distinction without a difference perhaps, although I think there’s a difference: one may become engaged, involved, with something without seeing himself in it, without relating to it. Regardless,

there’s no denying that more complex art is more entertaining from a purely

spectator perspective than simple art with no flourishes or folderols.

FOR THE RELATABLE THEORY we doubtless have Scott McCloud to thank. In 1993, he wrote and drew a very persuasive book, Understanding Comics, in which he belabored the difference between representational art in depicting a face and the abstracted version thereof in the circle, two dots (eyes) and a curved line (smiley mouth) of a stick figure’s face. Because the representational drawing looks like someone, the viewer tends to see it as the face of another; the abstract face, however, looks like no one and therefore “resembles” everyone, including yourself. So you see yourself in it. You therefore relate to it. This is a wonderful argument, and it serves McCloud’s purpose admirably: he wants to convince us that “there’s a lot more to cartoons than meets the eye” (to deploy one of his facile phrases). Cartoons are more than just pictures: they’re profound visions of our inner selves (among many other things, most of which he also details). Cartoons, in other words, are important. They’re important because we relate to them: and the simpler they are drawn, the more readily we can see ourselves in them. That’s his argument about the abstract (simplified) face vs. the representational one. It’s a theory. A convincingly developed theory, but still, just a theory. No scientific study has validated the theory of relatability. With equal foundation in science, I can say that the theory of relatability is nonsense. That’s my theory. Particularly as it applies to crudely, simply, drawn pictures. The presumed logic of this “relatable” theory in that context is an affront to reason. We want to understand the otherwise inexplicable appeal of pathetically inept drawings, so we leap to accept this facile but fraudulent “reason”: we relate to them. The appeal is easily explained without employing any such far-fetched theory: as I said above, it’s the idiotic coupling of banal utterances with inept pictures. We marvel at the mental gymnastics such couplings seem to expect of us. And we laugh as we realize we’ve been fooled. We like laughing, so we line up to be fooled again. But the “relatable” theory is not only fraudulent: it’s insidious. It ushers in at least one other load of crap—er, fraudulent notion—plus a screamingly erroneous supposition fraught with hazard for the medium. For the first, Tornoe cites Susie Cagle, the current idol of cartoonist-journalists. “Cagle said the biggest hits among readers have been explainer infographics, in which she uses her cartoon style to break down complex issues into a visually appealing narrative that’s not intimidating to digest.” She simplifies complexity. Whenever complexity is simplified, nuances of meaning and significance are left out. For a generation of so-called “readers” who communicate in 140-character texts, leaving complexity out is a way of life. But it’s scarcely intelligent or even reasonable. Life is complicated. And you cannot conceivably solve the problems it poses if you simplify the complexities away. Solutions reached in this mindless manner never address much of the problem because much of any problem tends to reside in its complexities. The hazard that championing stick-figure funnies introduces is the idea that the superiority of the Web’s simply-drawn comics will bring about the death of newspaper comic strips. The danger in this illogic is that it may become a self-fulfilling prophecy: if you keep talking this way, someone—newspaper editors seeking to save money—may well come to believe it. As a breed, newspaper editors have displayed an astonishing inability to understand the Internet, and I’ve seen nothing in their behavior that suggests they can see the flaws in the reasoning that asserts the superiority of stick-figure funnies over the traditional drawn kind in their newspapers. If newspaper editors come to believe that everyone (everyone under the age of 55, say) prefers the Web’s abysmally simplistic cartooning, they they’ll start dropping other comic strips from their content because they’re desperate to attract readers under the age of 55. This train of thought makes no sense—at least, not the way I’ve so baldly stated it; but the absence of sense has not deterred newspaper editors from doing any number of senseless things. Editors will look at Web comics, and they’ll realize that in their own comics sections, strips like Pearls Before Swine and Cathybert and Drabble—all painfully simple scribbles—are among the most popular, ergo the lesson: get rid of every other strip and keep the crudely drawn ones.

AND THE

CHAMPIONS OF WEB COMICS will cheer them on while also urging everyone to

abandon print altogether in favor of a glowing electronic digital universe.

Those self-same Lochinvars of illogic have managed to accuse Garry Trudeau in Doonesbury on February 2 of conducting an elitist screed. “Now, I love Doonesbury. I also love newspapers. I don’t want print media to go away. That said, saying it’s the only way (especially for comics) is just plain insulting, and reeks of elitism. All due respect to Garry Trudeau, whose work I adore and respect, but this strip represents an archaic, narrow-minded, elitist mindset.” That’s the kind of so-called reasoning that the trends of simplification foster. The supersensitive souls in their electronic bubble see Trudeau’s championing of print as, ipso facto, an assault on digital, exhibiting the kind of paranoia that is, alas, a sign of our times. Everywhere. The strip says, merely, that if newspapers go away, so will newspaper comic strips—leaving “nothing” in their stead. No newspaper; no newspaper comic strips. A commonplace. A foregone conclusion. In urging readers to “stick with print,” Mike Doonesbury is implicitly denigrating digital, but the purpose of the strip is not to attack the ethereal empire but to urge no further neglect of the print medium. But even that interpretation misses the mark Trudeau intends. The February 2 strip is not a stand-alone joke. It’s a Saturday strip, the conclusion of the preceding week of Doonesbury—Mailbag Week, which, this time, has yielded no letters. Not even e-mail. Instead, readers are communicating by Twitter, which Zipper and Jeff (dawg and the dude), who begin the week, applaud because it keeps the questions concise. And these two are not thinkers enough to enjoy dealing with complicated questions. But they recognize that in tweets, quality can suffer. In the same fashion, every concept toyed with during the week finishes by being contradicted or undermined, ridiculed, usually by some aspect of the concept itself—just as tweets are concise but devoid of quality. As usual during Mailbag Week, the characters are messing with the fourth wall—despite one tweet which cautions against it. And when another tweeter wonders if the “millennials” are taking over the strip, Zipper and Jeff are immediately replaced in the next panel by Zonker and Mike, vividly demonstrating that strip stardom is transitory—even, we must suppose, for Zonker and Mike. The February 2 strip is a continuation of the self-ridicule that is the week’s theme. The blank in the middle leads to the day’s punchline, but it’s more than just the day’s punchline: it’s the week’s punchline. All week long, the strip’s cast members have been doing or experiencing the opposite of what they seem to recommend—just as they do on Saturday. Doonesbury advises readers to “stick with print” while the strip has already abandoned print for tweets in the Mailbag—as Portland’s Hal so acutely observes in the Blowback comment section of the Doonesbury website: “Trudeau, as usual, is throwing us a whammy of social satire,” Hal says, “—this one so subtle that it seems to have gone over the heads of just about everyone [commenting in Blowback]. ... [The February 2 strip is] the perfect punchline for a bunch of related satirical sub-points in every panel of every strip the whole week. Brilliant! I burst out laughing so hard my vision started to blur.” The strip makes a dramatically convincing statement on its own about what happens to newspaper comic strips if newspapers die, but it is also a summation of the week’s self-contradictory theme—something entirely overlooked by all those whose mental faculties are impaired by their enthusiastic involvement in the simplicity of web comics. See what simplification can lead to? I rest my case. Luckily, some hardy souls amongst the digitally damned found a way to laugh atTrudeau and filled the telltale gap in his strip with a response in the same vein of ridicule. Not convincing in any profound way, but fun. And if newspaper comics—indeed, all print-based visual storytelling—were not undermined by the tunnel vision of digital’s simplified reasoning, they will most assuredly be destroyed by the tone-deaf salesmanship of the syndicates that distribute newspaper comics, as exemplified in Part Two, herewith—:

THE FATE OF THE FUNNIES: PART TWO At the Duluth News Tribune, editor Robin Washington explained why the paper was dropping Blondie. I’m reprinting almost his whole explanation here because of what it reveals about the syndication business, in general as well as for King Features: On Wednesday, Blondie will no longer appear. A new strip, Pearls Before Swine, will take its place. Before I get to why, let me state that I like Blondie. She’s a sensible, devoted mother and wife who’s aged well (the clock stopped when she hit 40 or so) and if the punch line relies on the same old antics, they’ve more or less kept pace with the times (today’s strip is about streaming the Super Bowl on electronic devices). An exception is Mr. Dithers’ roll-top desk and overstuffed swivel chair, but you try getting him out of it. There aren’t a lot of readers who remember, but when Blondie made her debut in 1930, she was portrayed as a gold digger. It turned out to be a bum rap, and she and Dagwood married for love. His father disinherited him, however, and Dagwood’s been a working stiff ever since. So it’s not surprising to find Blondie again at the center of a financial dispute, if through no fault of her own. The Duluth News Tribune is one player and the other is King Features Syndicate, which licenses and distributes Blondie and many other comics to newspapers and other media. Syndication is a perfectly fine business. What’s not fine is that the DNT is charged roughly twice as much for Blondie as for any other strip, and more than five times higher than some. The Sunday Blondie is billed at $62.01 per week. By contrast, Hi and Lois costs $32.22, and Beetle Bailey only $11.67. Both of those are also distributed by King. It may sound like I’m penny-pinching, but automatic, recurring charges add up; think of your cable bill. Yearly, the Sunday Blondie alone comes out to $3,224.52, which could easily be allocated to other needs for the paper. (New digital emergency radio frequencies require us to buy a new police scanner that goes for $500.) The bigger issue, though, is the explanation for why we’re paying so much, which I asked of the company’s salesman on his last visit here. His answer? The DNT is a “legacy” subscriber, going back years (Blondie first appeared in the Duluth Herald and Sunday News Tribune in May 1937), and therefore subject to yearly price increases. In essence, our benefit for being a longtime customer is we get to pay more. I suggested that maybe we should cancel it and start again, but he warned me I didn’t want to do that — and launched into the story of how the News Tribune once canceled Beetle Bailey and the Budgeteer [then a rival paper] picked it up and made hay out of it. I don’t know if he heard me say that’s unlikely these days because the DNT and Budge are now the same company. Regardless, if he didn’t want to talk about it then, he certainly hasn’t made much of an effort since. For at least a year I have called and e-mailed him repeatedly with no call back. So has my assistant. Zip. No response to our director of finance, either. Someone at the syndicate finally did acknowledge our flat-out notice to cancel, so that’s what will happen, effective this Wednesday. In its place will be Pearls Before Swine, a more contemporary, offbeat strip. It’s nothing like Blondie, but the syndicate that handles it is nothing like Blondie’s, either. To start with, they called us back. And they offered a very reasonable price, though that isn’t the only consideration. If you like it, tell us. If you don’t, tell us also, and we may consider something else. Maybe the King Features guy will read this column and call us back to renegotiate. I hope he does. Blondie’s a nice lady, as I said, and doesn’t deserve the gold-digger rap.

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted THE MOTTO ABOVE, which was adopted long ago by some gaggle of wags who otherwise drew editorial cartoons, doesn’t mean what it meant originally, when coined in 1902 by Finley Peter Dunne in the person of his fictional bartender, Mister Dooley, who said: “The newspaper does everything for us. It runs the police force and the banks, commands the militia, controls the legislature, baptizes the young, marries the foolish, comforts the afflicted and afflicts the comfortable, buries the dead, and roasts them afterward.” (My emphasis.) Mister Dooley was being sarcastic, of course, “damning journalists of his day for their bias and presumptuous sanctimony in picking winners and losers, advancing their own pet causes and editorializing in the guise of reporting” said Mike Rosen, a right-wing columnist at the Denver Post.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS “It’s just plain common sense that there be a waiting period to allow local law enforcement officials to conduct background checks on those who wish to buy a handgun.”—Ronald Reagan, endorsing the Brady handgun control bill, March 1991. “This is a matter of vital importance to the public safety. ... While we recognize that assault-weapon legislation will not stop all assault-weapon crime, statistics prove that we can dry up the supply of these guns, making them less accessible to criminals.”—Ronald Reagan in a May 3, 1994, letter to the U.S. House of Representatives

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution NBC’s Brian Williams has the crookedest face on tv. Look at him straight on: his nose bends one way, his mouth tips in the other direction, and his eyebrows aren’t even when raised. Knowing this helps those of us who aren’t, like Williams, making a living on our looks.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

Zits gave me a chuckle because it imparts visual substance to the expression "liar, liar, pants on fire." And it makes comedic sense only if you know the expression. Even then, you have to think about it for a minute in order to realize what Jim Borgman and Jerry Scott have done herein. Our

next exhibit is an odd miscellany of wholly unrelated moments of joy on the

funnies page. The Garfield gag seems obvious, but that’s why it’s funny and I love it. And in Jump Start, Robb Armstrong reminds me of something that I’d forgotten, the racial identity of Alexander Dumas. Also reminds us that February is Black History Month. Ray Billingsley usually spends a week or so in Curtis on black history, but so far this month (as of February 9), he hasn’t done more than devote a Sunday strip to a joke about Curtis’ scheme to avoid writing an essay about an African American he admires. In Freshly Squeezed, a strip about three generations of the same family squeezed into the same household because the older generation lost its home to foreclosure, the senior male of the ensemble announces that he’s taking a cartooning course from “a former left-wing editorial cartoonist whose newspaper folded,” exactly the situation of its cartoonist, Ed Stein, who, for at least a generation, editooned for the now defunct Rocky Mountain News. The cows in Blondie surprised me. Never saw cattle in Blondie before. They’re perfectly serviceable cows—and in the drawing style of the strip, too. Nifty. Finally, in Free Range, we are reminded of the towering silliness of the one of the slogans that the National Rifle Association and its minions adopt every time their guns are threatened. As a semantic fact, if pies are outlawed, only outlaws will have pies. By definition. Silliness, as I said.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. THE INAUGURATION on January 21 was a fake inauguration: Bronco Bama was actually sworn in the day before, but because it was a Sunday, tradition puts off the public ceremonies for a day in honor of the national pieties that prohibit anything from happening on Sunday except going to church. And the Superbowl. Reminds me of the most picturesque of American presidents, David Atchison of Kansas. Atchison was president pro tempore of the Senate on March 4, 1849, when prez-elect Zachary Taylor decided to postpone the swearing in for a day because March 4 was a Sunday, so because the presidency of his predecessor, James Polk, ended, by Constitutional fiat, at noon on March 4, the country would be without a chief executive for twenty-four hours until Taylor would be sworn in at noon on Monday. As prez-pro tempore of the Senate, Atchison was next in succession, so he was prez for the day, March 4. But because he’d just been elevated to prez pro tempore on March 3, the day the new Senate convened, he went out to celebrate that night and drank so much that he spent the entire next day passed out in bed. It was the shortest presidency on record and the only one to claim zero accomplishments. Also zero gridlock.

THE COLUMBIA JOURNALISM REVIEW reported in its September/October issue under “Currents” the attractions of a New York bar called Tom and Jerry’s, the name of which is derived from the Christmas cocktail “not the ultra violent cat-and-mouse team” of the animated cartoon series about Tom, the household cat, and Jerry, the house mouse. Ultraviolent? That’s the new politically correct way to describe it, I suppose, and if I am going to be consistent in my insistence that we must reduce the violence in our entertainments as a way of changing the culture of violence that fosters gun play leading to mass killings, then I guess I have to frown at the “ultraviolence” of Tom and Jerry. But it don’t feel right somehow.

SARAH LIVINGSTON PALIN lost her job last month when Fox News declined to renew her $1 million-a-year contract. Fox honcho Roger Ailes was reportedly pissed that she wouldn’t take his advice to be less confrontational with her critics, but what really set him off was when she announced that she would not be running for Prez during a radio interview—not on Fox News. “I paid her for two years to make this announcement on my network,” Ailes reportedly fumed. Fox offered to renew her contract if she’d take a substantial pay cut, but the Palin would have none of that: she quit, saying she had grown to like being “off the stage.”

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—:

Just What the Doctor Ordered: Early Writings and Cartoons by Dr. Seuss Edited with an Introduction by Rick Marschall 144 8x9.5-inch pages, b/w; Dover paperback, $14.95 IF YOU’RE A DR. SEUSS FAN, you probably already have The Tough Coughs As He Ploughs the Dough, a 1987 book that is exactly the same as the title above. Just What, in fact, seems to have been photographed from Tough Coughs, page for page, and the reproduction suffers slightly as a result. Don’t be fooled by a new publication date and name: it’s the same book. Worth owning if you don’t have the other one and you’re a Seussian.

MOTS & QUOTES “If you agree with me on 8 out of 12 issues, vote for me. If you agree with me on 12 out of 12, see your psychiatrist.”—The late Ed Koch, colorful three-term mayor of New York

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets

Al Capp: A Life to the Contrary By Michael Schumacher and Denis Kitchen 318 6x9-inches pages, text with b/w illos, photos, and a color insert; Bloomsbury hardcover, $30 DENIS KITCHEN, WHOSE Kitchen Sink Press published compilations of Al Capp’s Li’l Abner dailies from 1934 through 1961 in 27 volumes (1988-1998), had developed a rapport with Capp’s family, widow and children, that gave him extraordinary access to Capp’s papers—letters, documents (including an unpublished autobiography) and memorabilia the Capp family had in storage boxes. As the authors say in their Acknowledgements: “We spent countless hours constructing timelines, checking and corroborating the facts, reading through thousands of pages of news clippings, letters, and official documents; we watched old recordings of his television appearances. We interviewed, in person, over the phone and via 3-mail, anyone who could supply us with needed information and details.” The result is this remarkable biography, rich in the details of the major events in Capp’s life. Before we plunge further into this review, I must alert you to the possibility that my biases may affect my opinion of the book. Kitchen has been acting as my agent for several years in an effort to find a publisher for my own Capp book, Hubris and Chutzpah, about the sensational feud between Capp and Ham Fisher, creator of Joe Palooka, a strip equal to Li’l Abner in popularity but entirely different in its themes. After many years, Kitchen has been unable to find a publisher, and so I’ve published the book myself, posting it to Harv’s Hindsight early this month. So my biases, however discernible they may be, spring, on the one hand, from a long and friendly relationship with Kitchen; on the other hand, from his failure to find a publisher for my book. (To be fair, I wasn’t pushing him very hard at any time because I was always so deeply into other projects I could not have spared much time to do the book if he’d found a publisher. I don’t think I’m at all miffed about this, but maybe I am and don’t know it.) Whether these confessed biases influence my attitudes about the Schumacher-Kitchen book for the better or for the worse you must decide for yourself as you read through this review. The chief occurrences of Capp’s life are treated in great detail: the loss of his left leg at the age of nine and the probable psychological consequences; his education at a succession of art schools he was too poor to pay tuition to; his apprenticeship to Ham Fisher and the dispute about who created the hillbilly Big Leviticus in Joe Palooka; the resulting feud, its nastiness, and Fisher’s attempt to smear Capp’s reputation; Capp’s emergence as a pop culture celebrity; his shrill attacks on the New Student Left on college campuses, protesting the Vietnam war by trashing the administrative offices; his notorious visit to John Lennon and Ono; the subliminal eroticism in Li’l Abner; Capp’s extracurriular sex life, preying upon show girls and college co-eds, and his fall from grace as a result. In every instance, the book offers insights into these events that are new to me (and I’ve researched Capp’s life for my book, at least as much as publicly available documents permit). About Capp’s womanizing, for instance, I learned that for over a year (1940-41) he conducted an affair with a young singer in California. The book quotes from her letters to him (found, I assume, among Capp’s papers) and, remarkably, from his letters to her, obtained from the daughter of the woman in question. This was no simple dalliance: they were obviously in love. The authors also interviewed Patricia Harry, the University of Wisconsin co-ed at Eau Claire whose misadventure with Capp became national news when she sued him. Her detailed account of the rape is chilling and disgusting—and entirely new; until reading it, I had assumed, with the rest of the world, that the charges against Capp were all about his attempts (attempted adultery and attempted sodomy [oral sex]) rather than his dubious success in sexually assaulting her. With the detail of these two revelations in mind, it is remarkable that the authors’ treatment of the erotic images in Li’l Abner is so restrained. Fisher accused Capp of mking pornography, and one of the issues raised by the accusation was whether Capp had drawn the pictures in question. Capp denied it. But he did draw the pictures; and in my Hindsight piece, I provide visual evidence to support this contention. Schumacher and Kitchen agree that Capp drew the offending pictures albeit their assertion is considerably more circumspect than mine: “For discerning readers, including Fisher, Capp’s frequent visual and verbal double entendres were indisputable, but they were always clever enough to be ambiguous and thus fly below the radar of the vast majority of unassuming readers.” In support of this view, they reprint a couple of the tamer specimens, both of which I’ve included in my piece. I also include many others, most of which are much more blatant comedic examples of sexual imagery in the strip, albeit still equivocal and subject to alternative interpretation. Clever, as they say. Schumacher and Kitchen navigate their way through the episode by focusing mostly on the second issue that Fisher’s accusation raised: was he the person who circulated carefully cropped panels from Li’l Abner to newspaper editors, claiming the pictures showed that Capp was a pornographer and expecting that the editors would therefore drop the strip? And did Fisher send those same images in 1951 to a New York state legislative committee investigating comics to see if they should be censored? By this indirection, Schumacher and Kitchen avoid dealing at length with the more scandalous aspect of the affair—namely, that Capp was producing subliminal pornography. My answer, as I’ve said, is that he most assuredly was. That’s their answer, too, but circumspectly stated, as we’ve seen. As for Fisher’s hand in the affair, Schumacher and Kitchen decide, as I have, that Fisher did smear Capp by circulating the incriminating pictures. The National Cartoonists Society reached the same conclusion and suspended Fisher for conduct unbecoming of a member. At the time, with Fredric Wertham blathering on about comic books turning children into criminals, Fisher’s circulating nasty pictures purportedly being drawn in a daily newspaper comic strip threatened all syndicated cartoonists as well as comic book publishers. Fisher, humiliated by the expulsion, could no longer play the role he so enjoyed—that of the cartoonist celebrity. Within a year, he’d committed suicide. An explanation for the gingerly way the authors deal with Capp’s career as a pornographic prankster may be that the Capp family—his widow, daughter, and grandchildren—didn’t want this dirty linen aired, and since Schumacher and Kitchen depended upon their help (giving access to Capp’s papers and being interviewed), the authors may have been reluctant, understandably, to upset their sources. But they persisted and were finally given permission to use even copyrighted material without any conditions except for including a disclaimer on the book’s copyright page: “Neither Capp Enterprises, Inc., nor any affiliates, including members of the family of Al Capp, attests to the accuracy of any statements, facts, or conclusions set forth by the authors. Capp Enterprises, Inc., in no way endorses the content of the book nor does it imply that the book is in any way an authorized biography of Al Capp.” Pretty severe, you’d think; but, given some of Capp’s adventures related therein, the disclaimer amounts to a ringing affirmation of the book’s accuracy. The essence of all of Capp’s career, if not in every sordid detail (but in detail enough), is here, at long last. Schumacher and Kitchen have squelched rumor and hearsay with reasoned argument and persuasive fact. The result is a genuinely impressive and authoritative insight into an overlooked but morbidly fascinating corner of comics history. Their resolution of the hillbilly dispute that prompted the feud is similarly satisfying. They credit both Capp and Fisher with aspects of the creation of Big Leviticus while also concluding the Capp’s version of the story is probably more fiction than fact—something that was often true of Capp’s accounts of events in his life. In their Big Leviticus scenario, Schumacher and Kitchen manage to favor both sides of the debate by knitting a few known facts together with a few reasonable speculations and adding some probably fictional connective tissue to create a cohesive story. In their conclusion, they decide for Fisher. They suppose that Capp brought the idea of hillbillies to story conferences with Fisher, and Fisher, even though not initially keen about using such characters, wrote a script for the Big Leviticus adventure. In support of this contention, the biographers cite a long-standing custom in the syndicate business that cartoonists submit scripts to their syndicates for approval 6-8 weeks before scheduled publication. This interpretation of events is as plausible as any other. But the explanation is scarcely leak-proof. Not all syndicated comic strip cartoonists were required forever by their syndicates to submit scripts for approval in advance. And by 1933, Fisher’s strip was roaringly successful; it’s at least probable that he wouldn’t have been expected to get approval in advance for his stories. Moreover, in support of Capp’s version of events, Big Leviticus’ behavior is more akin to the sort of comedy Capp would later develop in Li’l Abner than anything Fisher had done or would do. Still, Schumacher and Kitchen find it highly unlikely that Fisher, a notoriously fussy man, would have permitted his “brand new assistant” to solo on the Big Leviticus story so soon after joining Fisher; the Big Leviticus story appeared in late October, and Capp had joined Fisher only five or six months earlier. In their narrative, Fisher did not, as Capp always maintained, go on vacation the preceding summer; he was present while Capp drew the sequence. Big Leviticus shows up again in the strip a few months later, and it was during this time that Fisher probably went on vacation. Capp was just confused in his memory of the sequence of events. Schumacher is the chief writer of the book; Kitchen, the researcher and fact-checker. “After decades of seeking,” Kitchen told me, “I had amassed a full file cabinet, several binders and about six storage boxes of newspaper, magazine articles, interviews, photos, clippings, correspondence, an unpublished autobiography, and ephemera of all kinds. And I had been talking to [Capp’s] associates and relatives for years. That was my primary contribution. Once we agreed to co-author, we divvied up the new interviews and shared everything. And Michael is the more experienced writer, so he did all the first drafts, then we’d go back and forth until we were both happy.” Schumacher’s narrative manner is novelistic. He often says what Capp and others “thought” or “suspected” or “hoped.,” creating a mildly annoying nag at the back of the scholarly reader’s brain. Clearly, he cannot know what these people were thinking or what they suspected. But he works within the tradition, speculating reasonably from the evidence of letters and interviews and the like. And his style, brisk and confident, persuades me that he knows what he’s talking about even when he seems, impossibly, to be inside the heads of his subjects. Despite such quibbles, I enjoyed the book immensely, and I learned many things I never knew. The authors go into some detail in describing the functioning of Capp Enterprises, for instance—the entity Capp established to market his creations. Several sections of the book reveal the seemingly endless quarreling between Capp and his brother Bence, the chief operating officer of Capp Enterprises. And buried in a footnote is one of the most revealing insights in the book. After mentioning the unpublished autobiography Capp wrote, Kitchen says: “More than forty-five years after he worked for Fisher, Al Capp’s emotions still ran high when he discussed the details of his employment and Fisher’s character. He was becoming so enraged when typing the manuscript that he [hit the keys so hard they] would punch holes in the paper when he was typing lower-case o’s. Entire pages dealing with Fisher are perforated, whereas all the other pages are clean” (268). The book is amply but not excessively illustrated with photographs and a dozen or so Li’l Abner strips. The authors mention and discuss most (if not all) of the fondly recalled of the strip’s lore—Sadie Hawkins Day, the shmoo, Lower Slobbovia, Fearless Fosdick, and the like. But, strangely, there is little or no analysis of the strip as pervasive satire. The shmoos, for example, supply humans with food and loving companionship and are therefore a threat to so-called civilization: humanity loses the motivation to go to war and to engage in every sort of capitalistic enterprise. Why bother? Shmoos provide everything one needs. And for that very reason, in Capp’s satirically warped mind, the shmoos had to be destroyed wholesale. Otherwise, they would “corrupt” society, demolishing the very things upon which civilization is founded—namely, greed and need. And Lower Slobbovia, Capp’s satire about U.S. foreign aid, is similarly slighted; the authors mention this miserably poor “country” only in connection with the Lena the Hyena contest to draw the world’s ugliest woman. (For the whole Lena story, see Harv’s Hindsight for May 2011.) At first blush, the absence of any discussion of Capp’s satirical genius seems a colossal oversight. Li’l Abner was the first overtly and doggedly satirical comic strip in syndication, breaking long-standing taboos in the industry by having a point-of-view, and Capp achieved fame outside the strip as a satirical commentator of raucous but keen social and political insight. His fame, built upon satire, was so great that he was the only cartoonist other than Walt Disney to have a theme park built upon his creation—Dogpatch, U.S.A. Capp was one of a handful of genuinely trail-blazing newspaper comic strip cartoonists, and he is in the forefront of that small but significant procession. Without any discussion of the workings of Capp’s satire, we can’t have much appreciation for the profound achievements of his career. In defense of the authors, however, I direct attention to the subtitle of the book: it’s the “Life” not the “Life and Art” of Al Capp. The emphasis is, as predicated by the title, on the cartoonist’s life not on his artistry. And his life was, as his brother once said, at least as interesting—as compelling a narrative—as the fictions Capp told about himself.

BEFORE WE LEAVE AL CAPP, one more historic scrap. You may have noticed, as thousands have, that the part in Li’l Abner’s hair shifted around: first on the right; then on the left. Asked which side his hillbilly parted his hair on, Capp usually said, “On the side facing the reader, naturally.” And so it was for over four decades. But before Capp fell into that groove, he experimented, briefly—only four or five times—with Abner have a part on only one side of his coifure. And herewith, we present the evidence.