|

||||||||||

Opus 304 (January 17, 2013). It is with sadness and acrimony that we note the death of the Comics Buyer’s Guide: after 42 years of banding fandom together, it falls victim to the machinations of yet another private equity firm. By way of commemorating CBG’s considerable accomplishments, we review its history, warts and all, starting with ruthless Alan Light, the founder, and carrying on through the professional years of Don and Maggie Thompson. We also ponder another death, the peculiar expiration of Spider-Man, and we offer a fool-proof solution to the gun violence epidemic in the U.S., after glimpsing editoons on the subject (and on the perils of the fiscal cliff). And we do short reviews of Black Kiss II, Hawkeye, Comeback, Foster, Black Beetle and All-New X-Men. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order—:

NOUS R US Comics Buyer’s Guide Ends* Spider-Man Ends (Sales Boosting Dodges) Stan Is 90 Name Dropping & Tale Bearing Graphic Novels in Schools Tardi Refuses Shel Dorf in Unmarked Grave Skippy and Spam

* HISTORY OF TBG/CBG Alan Light and the Thompsons

EDITOONERY Guns and the Cliff Editorial: The Happy Harv’s All-Time Solution NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Baldo Funky Winkerbean Beetle Bailey

BOOK MARQUEE Tarzan’s 100 and a New Tarzan Book

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Short Reviews of— Black Kiss II Hawkeye Comeback Foster Black Beetle All-New X-Men

UNDER THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Congressional Retirement Pay Exposed

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Comics Buyer’s Guide Falls Off the Edge Can’t say we didn’t see the scrawl on the wall for this. The shrinking page count over the last couple years was ample indication of the venerable fanzine’s growing financial embarrassment. And last summer, CBG, for the first time in my memory, didn’t have a booth at the San Diego Comic-Con. It was, I thought, only a matter of time. Then on January 9, CBG editor Brent Frankenhoff posted the bad news for Krause Publications, the magazine’s publisher: after 42 years, CBG will cease with the March 2013 issue. It’s No.1699. When CBG reached No. 600 in May 1985, Don and Maggie Thompson, the editors at the time, took note: “In the comic-book field, there isn’t another publication that has made it to 600 issues.” Too bad, now, that Krause (or the private equity firm that owns CBG and Krause; no, not Bain) couldn’t have held off just one more issue to establish the publication’s record in a nicely rounded number, 1700. But the decision to kill the longest-running magazine in comics fandom was made after No.1699 had gone to press. It was kaput, and that was that. No more discussion. It’s done. The last issue is thus denied the possibility of dying with dignity. The issue contains no sentimental farewells by staff members, no round-ups of achievement to marvel at. Nothing. Cause of death? In the realm of print, it’s the same old story: diminishing advertising revenues coupled to the competition of free content on the Web made CBG increasingly irrelevant and financially unrewarding for the publisher. Said David Blansfield, president of the parent company: “We continuously evaluate our portfolio and analyze our content strategy to determine how well we are meeting consumer and Company goals. We take into consideration the marketplace we serve and the opportunities available for each of our magazine titles. After much analysis and deliberation, we have determined to cease publication of Comics Buyer’s Guide.” Translation: “We’re not making the kind of money we used to make, and we want to make even more money than we used to.” That’s how you keep a private equity firm at bay: make more money. Current subscribers to the magazine will receive a one-for-one conversion to CBG sister publication Antique Trader: a biweekly that has served the antiques and collectibles community since 1957. Right: we’re all going to give up collecting comics and start collecting antiques. The www.CBGXtra.com site and its Facebook page will exist as an archived resource administered by Antique Trader. At his website, newsfromme.com, Mark Evanier expressed the feelings of many who had grown up and into comics fandom with CBG: “I go way back with the publication, back to when it started as The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom, published by Alan Light in February, 1971. My then-partner Steve Sherman and I were, I believe, its first columnists. We did one in the fourth issue but never followed-up on it. I then became a columnist for them 23 years later. ... When Alan ran it, the newspaper was a fine place to read ads and a few good articles but not much more than that. Still, at that price — free for the first years of its existence, darned cheap thereafter — it was a must-get for most of us in and around comics. “In 1983, he sold it to Krause Publications, a firm which specialized in hobby-oriented material. Don and Maggie Thompson were hired to run it and the publication was quickly revamped into the central nervous system of the comic book field with timely news, opinions, articles on comic book history—and lots of ads. The ads never interested me much but I found other things to enjoy—and in every issue. “Since the Internet flourished,” Evanier went on, “we’ve watched CBG shrink like Ray Palmer after a gastric bypass. I hardly know what to say about its termination except that this does not come as a surprise. I’ll miss it—but then I’ve missed it the last few years as each issue arrives with fewer pages than the one before. It was a great thing in its day and I’m sorry that day is over.” But these few cryptic paragraphs scarcely tell the story. Writing to celebrate 40 years of CBG’s publication in June 2011 with No.1678, columnist Michelle Nolan comes close by remembering that when TBG/CBG began, “there was no Internet, no eBay, and no Heritage auctions. There was only CBG if you wanted to read about comics, to write about comics, and to buy inexpensive issues. And that was true for many years.” Cartoonist and life-long comics fan Jim Engel comes even closer, when he begins his Facebook reaction to the announcement of the end of CBG by saying: “TBG/CBG was for me (as I'm sure it was for many of you) a true institution in my life, for a long time. I think my subscription began with the 5th or 6th issue, and it was a much-anticipated highlight of my week every week.” I quote all of Jim’s remarks later, down the scroll, on the other side of the $ubscribers Wall, where we have room to mark the passing of this landmark fanzine properly.

ANOTHER SUPERHERO, ANOTHER DEATH Spider-Man is celebrating his 50th anniversary this year by dying. Some party. At wired.com, Laura Hudson reports, somewhat bitterly, that “five years after the webslinging superhero was forced to retroactively erase his marriage to Mary Jane in a desperate deal with the devil (true story), things are about to get even worse for Peter Parker in Amazing Spider-Man No. 700, a issue so controversial that it inspired numerous death threats against the book's long-time writer Dan Slott. So what could happen to Spidey that would make his satanic retroactive divorce look tame in comparison?” Easy: he dies. Humberto Ramos draws the death issue. Says Hudson: “Supervillain Doctor Octopus secretly takes over Spidey’s body to become the new Spider-Man. After a climactic confrontation where Peter Parker forcibly transfers his memories — and apparently, his morality — into the mind of his body-stealing enemy to make him a better man, the physical form of Doctor Octopus expires, taking Peter with it. Reborn as a hero, but still somehow a pompous jerk, Doc Ock declares that he will become a superior Spider-Man, a turn of phrase that segues neatly into the January launch of the comic book Superior Spider-Man, starring Doctor Octopus as Spider-Man.” Readers, naturally, were outraged. Foaming at the mouth outraged. And the Internet gives them a worldwide, cosmos-spanning place to air their fury. “In Slott's case,” Hudson writes, “this meant a long series of Twitter death threats where readers actually tagged the writer in their tweets. "Did I know fans were gonna be passionate about this? Sure," Slott told Hudson. "When we started dropping hints about what was coming up in Amazing Spider-Man No. 700, I was the first to make the jokes that when the issue came out I was going to have to pull a ‘Salman Rushdie.' But let's be honest about this. Comic fans have always been this passionate. They just haven't always had a place to put their knee-jerk reactions that was as instantaneous as the Internet." Slott says the story has been in the works for 100 issues, eight years, and it represents a concept that is startling: “At their core, Spider-Man and Doctor Octopus are not truly that different.” Said Slott: "[Doctor Octopus] is the bespectacled nerd caught in an radioactive mishap that made him an analog of an eight-legged creature. Sound familiar?" asked Slott. "When we first met Otto Octavius, he was just like Peter Parker at the start of [his debut in] Amazing Fantasy No.15. The difference is, [Octavius] was older, set in his ways, he never had someone like Uncle Ben in his life and he [never] learned the lesson of ‘great power and responsibility.' Now that Peter Parker has set him on the right path, this is his second chance." The new title presents “a reversal of expectations that fundamentally changes the relationship between the reader and the hero,” Hudson said. “In the traditional Spider-Man stories, Spidey was forever on the run from policemen and angry, mustachioed journalists who thought he was a menace, while readers cheered him from the sidelines because they knew he was actually a hero.” "Now all of that is flipped," said Slott. "The people, police, and Avengers see him as a hero. They think they know the whole story. And the readers think he's an undeserving menace. The readers are now J. Jonah Jameson! That makes this Spider-Man the most meta Spider-Man of them all! If he can win over the audience by becoming a hero in their eyes, that will truly be an astounding feat!" Well, sure. But Slott’s world-altering rant notwithstanding, superheroes die every other month or so, but their deaths are never permanent. Captain America died, Superman died, Batman died, the Human Torch died—but all these deaths were subsequently reversed. So we can expect Spider-Man to reclaim his body from Doc Ock someday. That’s because superhero worlds are worlds of myth, Hudson points out: “They're worlds of enduring myths that are often elastic enough to stretch into temporary new configurations, but always seem to contract back into their original shapes. The point of stories where prominent characters die isn't that they die (they don't), but the potential for innovation that those temporary absences offer, and whatever the writers and artists manage to do with it.” DEATH! SEX! The Comic Book Sales Bump. At businessweek.com, Eric Spitznagel focused on the business implications of Spider-Man’s demise: “In comic book publishing, the decision to kill off a long-running and beloved character may seem, at first glance, like a terribly unwise business move. But when Marvel Comics released its latest issue of Amazing Spider-Man—No.700, which ends with Peter Parker, the webbed crusader's alter ego, getting murdered—the issue began flying off the shelves.” And Spitznagel goes on to quote Axel Alonso, the editor in chief at Marvel Comics: "The sales are phenomenal. Amazing Spider-Man No.700 has sold nearly 250,000 copies in print alone; final digital orders aren't in yet. This is the best-selling comic book at this price-point of the last decade, at least." But Marvel is scarcely plowing new ground with the ploy, Spitznagle says. Killing off major characters—usually title characters—has become “a common practice,” he notes, “which gained attention in the 1970s but reached new heights in the early 1990s, when DC Comics destroyed its most famous character, Superman, in a publishing event that fueled sales across the world.” He goes on to list four of “the most surefire, lucrative, and reliably controversial methods that comic book creators use to gain readership and boost the bottom line.” Embrace alternative lifestyles: funnybooks’ casts more and more include gay characters like Marvel’s X-Man Northstar, DC’s Batwoman, and Archie’s Kevin Kelly. Court ethnicity: African American mostly, but also Latino, Italian and Jewish. When, in August 2011, another new Spider-Man showed up in spider-duds, it was Miles Morales, half African American, half Latino, a development that inspired one of the nation’s most visible bigots to utter another of his transparently racist comments: Glen Beck discussed the bi-racial Spider-Man on his radio show, saying: "The new Spider-Man looks just like president Obama. I think a lot of this stuff is being done intentionally." No, Glen: it’s an accident. Sex it up: Spitznagle thinks superheroes/heroines wear tight NSFW costumes in order to advertise their sexuality (but it’s really because, originally, the artists liked figure-drawing), but lately the characters are slipping out of uniform for coital exploits, he goes on to say, pointing to Catwoman’s “violent sex” with Batman in the New 52's first issue of her title. At Dark Horse, sex led to pregnancy and abortion. More sales boosting excitement. Kill your icons: since Peter Parker’s girlfriend Gwen Stacy died in the early 1970s, comic book characters have been dropping like fruit flies, their demises “usually followed by a tsunami-size media response and a comic-buying frenzy,” Spitznagle says, quoting Brandon Zuern, store manager of Austin Books & Comics in Austin, Texas: “As far as what kind of controversy equates to biggest sales, it's always been and always will be the death of a major character. I think death in comics is way overused, but people keep buying them." The best part of killing an iconic character is that the fans do most of the work for you. And

then comes the fun of resurrecting the dead guy/gal, which is almost always

accomplished with as outrageously improbable a plot clank as possible. One can

weary of it—as did three editorial cartoonists when Superman died.

STAN IS 90 Stan Lee passed his milestone ninetieth birthday on December 28, and Michael Cavna at Washington Post’s ComicRiffs blog asked the living legend how it feels to be a nonagenarian. To which Stan reposited: "One bit of philosophy I made up some time ago—it’s a bit of a paradox: everyone wants to live to a ripe old age — but no one wants to be old!" Lee had pacemaker surgery last fall, but, said Cavna, “Lee defies a sense of seeming ‘old,’ forever moving like a human torch of kinetic energy.” When he came back from the hospital, Lee wrote: “In an effort to be more like my fellow Avenger, Tony Stark, I have had an electronic pace-maker placed near my heart to insure that I'll be able to lead thee for another 90 years!" In a more reflective moment, Lee remembers the 1961 debut of the Fantastic Four, calling it "the turning point of my life."

NAME DROPPING & TALE BEARING In a Chicago highschool honors class, sophomores are analyzing Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood by contrasting it to the graphic novel, Capote in Kansas, by Ande Parks and Chris Samnee. The Chicago Tribune’s Diane Rado says educators’ acceptance of the graphic novel “illustrates how far the controversial comic-strip novels have come. ... Once aimed at helping struggling readers, English language learners and disabled students, [comic books—] graphic novels—are moving into honors and college-level Advanced Placement classrooms and attracting students at all levels. There's no data on precisely how many schools nationwide use graphic novels. But no one disputes that in other markets the popularity of the comic-style books — adapted to classic literature, biographies, science, math and other subjects — is on the rise.” Jacques Tardi, one of France's most famous cartoonists, has turned down the country's highest civilian honor. On January 1, he was named among other recipients of the Legion d’honneur, but he refused it. Quoted at bbc.co.uk, Tardi explained: "Being fiercely attached to my freedom of thought and creativity, I do not want to receive anything, neither from this government or from any other political power whatsoever. I am therefore refusing this medal with the greatest determination." Tardi, who created the Adele Blanc-Sec series and graphic novels about the horrors of World Wars I and II (inspired by the experiences of his grandfather and father), said he had always ridiculed institutions. From Rich Johnston at bleedingcool.com: Shel Dorf basically founded the San Diego Comic-Con, now a massive media event, bringing in billions of dollars. Dying in 2009, he is buried in an unmarked grave in Home of Peace Cemetery. During the Detroit Fanfare convention, which hosts the Shel Dorf Awards, one group began raising money for a gravestone to commemorate the life of the man. They are looking to raise $2,200 for a stone the size of his parents’ gravestones, next to whom he is buried. It’s very possible that a reader of this website [bleedingcool.com] might be able to fund the whole thing. Or maybe just help with a few dollars. You can contact Jill Smethers for more at info@sheldorfawards.com

SKIPPING SPAM Although I like peanut butter (the crunchier, the better), I haven’t bought Skippy peanut butter for years. I’m boycotting it because the original brewer of the spread stole the name from Percy Crosby’s famous comic strip about an energetic 7-8 year old boy named (right) Skippy. Crosby’s Skippy was enormously popular, so the peanut people thought it would help sell their confection. They even stole the wood board fence that served as a logo in Crosby’s strip and slapped it on the peanut butter jar for a label. Crosby never gave them permission to use the name; nor did they ever compensate him for it. His daughter, Joan, has been waging a battle against the Giant Nut Corp for decades. (For chapter and verse on this heist, visit Harv’s Hindsight for April 2004 where the whole sordid history is painfully reviewed.) Today, bad news arrived here at the Rancid Raves compound, brought by the venerable Associated Press. I’ve been an enthusiastic user of Spam, the tinned meat concoction, for generations. For years, it was my daily sandwich. (The flavor was just nondescript enough that it never disappointed.) Now—tragic!—I read that the maker of Spam, Hormel, has bought Skippy. The idea is to “increase Hormel’s presence” in supermarkets and in China. Skippy is the leading peanut butter brand in China, where Hormel is trying to build up its Spam biz for years. Skippy will no doubt help. In this country, Skippy is offered in 11 varieties and has about 17 percent of the market. The market leader is Smucker’s Jif (which I buy) with 37 percent. So now that Hormel is an accomplice in the Skippy theft, must I give up Spam? Below

(or somewhere hereabouts) is the first Skippy cartoon. He started as a

single-page feature in the old Life humor magazine, and the page

reproduced here is “Skippy, No.1,” which appeared in the issue for March 22,

1923. Click on the image, then if you can’t read it, click on Page, then Zoom,

then 150%.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

WHERE DO YOU GET YOUR IDEAS? Quoted in The Lost Art of Zim, famed cartoonist W.A. Rogers responded to the question of where he got his ideas: “They might as well ask of a farmer, ‘Where did you get all that corn?’ The farmer could tell you that he planted it and broke his back hoeing it; otherwise, the crop would fail. The cartoonist plants his garden with carefully selected facts. No matter how dry these little seeds may seem, he knows that with proper cultivation they will produce a crop later on. There lies the whole secret of a cartoonist’s bag of tricks laid bare.” In the same vein in the same book, here’s another early twentieth century cartooner, Saturday Evening Post’s Herbert Johnson: “Cartoon ideas come to me as the result of deliberate cerebrations and constructions. When I am absolutely up against it, the editor sometimes gives me an article to illustrate, an editorial to read, or suggests something which helps. This is rare, however, A cartoonist is expected to hit ’em out. The editor may tell him when to bunt, but doesn’t bat for him.” Finally, there’s me: Where do I get my ideas? Schnectedy. (Dunno where I heard that, but I’ve always liked it as an idea whose time has come.)

BIDDING TBG/CBG A FOND ADIEU I SAW MY FIRST copy of The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom in about 1972. I must’ve sent off for a sample copy. I’d run across a few issues of the Menomonee Falls Gazette, the memorable weekly newspaper reprinting adventure comic strips published by Mike Tiefenbacher and Jerry Sinkovec, in a bookstore in the scruffier section of Hennipen Avenue in Minneapolis in the spring of 1972, and MFG led me, as I recall (however shakily), to TBG, “The Buyer’s Guide,” as the publication’s title was abbreviated and then abstracted in the common parlance of the day, incorporating into the initialized acronym even the definite article (“The”) that was part of the title. An awkward but rigidly followed practice in fandom. TBG had been functioning for only little more than a year. It had been launched by a 17-year-old kid in East Moline, Illinois. Alan Light was producing fanzines, Comic Cavalier and All-Dynamic, but wanted to do a newspaper for comics fans. When Mark Hanerfeld had been unable to continue The Comic Reader, which listed forthcoming funnybooks and their content—which was about all the “news” comics fans wanted at the time—Light hoped to take it on, says Bill Schelly in his Golden Age of Comic Fandom, but “Paul Levitz was publishing Et Cetera, very much in the TCR mold, and Light could not get access to news of the pros. ... A rebuffed Light decided to publish an adzine called The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom,” mimicking the title of a local free shopper called The Big River Buyer’s Guide. “For Comic Fandom” was printed in much smaller type. The publication’s name on its cover was the only thing set in type. Like almost all fan publications of the day, TBG was typewritten, not typeset. But it was printed not mimeographed. Almost by necessity, economic necessity—in time as well as money. Light solicited ads, which arrived on 8.5x11-inch sheets of paper; old and new comic books were listed for sale, the lists handwritten or typed. Light took these sheets as he got them and pasted four together to form pages measuring 17x22 inches. These, he took to a printer, who reduced Light’s paste-ups to fit an 11x17-inch page, then printed them two-up on sheets of 22x17-inch newsprint. The result, an unholy hodge-podge of cramped handwritten and typo-laden typewriter type “quarter page” ads, was sometimes painfully difficult to read. One advertiser as late as the spring of 1976 headlined his ad: “Squint and Save!” Whatever its faults, TBG became the most successful fan publication of the era. The interior was a mess, visually speaking, but handsome cover artwork was supplied by accomplished fan artists, even pros. The 22x17-inch publication was folded twice: first, to make a tabloid-size paper; then again for a convenient mailing-size, with the cover printed on one of the two visible outside pages. Light recruited his whole family—mother, father, sister and grandmother—to help him wet and stick mailing labels on the first issue, 3,000 copies, which were mailed out February 1, 1971. Light had bought a two-page ad in G.B. Love’s Rocket’s Blast-Comic Collector, then fandom’s premiere publication; the TBG ad appeared in No.76, December 1970. Light wasn’t sure when he sent the ad off if Love would accept and publish it: RBCC ran ads as well as articles, and TBG was an obvious competitor that, if successful, would take business away from Love. And it did. Three years later, in 1974, Love found himself with a dwindling income and sold RBCC to his assistant, Jim Van Hise. Van Hise took over with No.113 and published the magazine every six weeks or so until he moved to California whereupon the publication schedule flagged; the last issue, No.151 limping into the mail in October 1980. Light’s TBG was initially distributed fee to anyone who asked to be put on the mailing list, and its ad rates, Light claimed, were the lowest in comics fandom. In the ad in RBCC, Light even audaciously compared his $16 full-page rate to RBCC’s $15, emphasizing that TBG would more readers than RBCC—5,000 vs. 2,000. But most of Light’s 5,000 were fictitious as his first print run indicated. Light had started TBG in an auspicious year. In 1971, the comic book industry was having growing pains. The reviled Comics Code was modified for the first time since its adoption in 1954 to reflect changing mores and fashions; more daring stories (and pictures) resulted, attracting and holding older readers. Marvel and DC had raised cover prices from 12 cents to 15 cents in 1969, then jumped to 25 cents in 1971, dropping back to 20 cents almost at once—but increasing page counts. More comic for your money. Jack Kirby left Marvel for DC in 1970, but it wasn’t until 1971 that his New Gods and Forever People titles started, creating an entirely new kind of fiction for comics. Marvel began publishing black-and-white “magazine” comic books in May. DC changed publishers in 1971, installing an artist in the job—Carmine Infantino, whose influence brought new talent into the company and inaugurated much experimentation. Fandom was in full swing. Shel Dorf and a cadre of young friends launched the San Diego Comic-Con in 1971: first with a trial balloon, one-day event on March 21; then the first three-day Con, August 1-3, at the U.S. Grant Hotel downtown. And Robert Overstreet published the first of his Comic Book Price Guide in 1971, and that codified pricing—and selling. TBG, the new adzine on the block, walked right into an enormously lucrative opportunity—a burgeoning marketplace for selling old and new funnybooks. TBG circulation passed 4,000 in early 1972, and that summer, Light went from monthly to bi-weekly with No.18, August 1, 1972. Three years later, TBG started weekly publication with No.87, July 18, 1975. Circulation would hit 10,000 in 1977.

IN 1972 WITH NO.26 (December 1), Light started charging a subscription fee ($2 for 23 issues), disregarding his initial pitch, “free for life”; and he added editorial content to TBG to satisfy the Postal Service’s requirement that in order to enjoying cheap second class postal rates, only 75% of the publication’s content could be advertising. Light’s assistant Murray Bishoff started his column, Now What, joining Don and Maggie Thompson as content providers. Their Beautiful Balloons had started with No.19 (August 15), the second issue of the bi-weekly TBG. Cat Yronwode took over Bishoff’s column with No.329 (March 7, 1980), renaming it Fit to Print and turning Bishoff’s breathless gossipy enterprise it into a lively, informative newsy feature. Bishoff’s seat-of-the-pants journalism once resulted in DC instructing its staff not to talk to him “except in the case of emergency.” His column was full of noisome unenlightened opinion, frantic “stop the presses” rumor, and labored self-justification. And news. Some news made it through the fog of balderdash and bluster. Here are some samples of Bishoff’s journalistic panache: “With both Roy Thomas and Jack Kirby in California now, much of the comic industry’s nerve center has shafted from the East coast.” “Here I am, a little late this month because we had a death in the family, and I was forced to leave town for a week at a most inopportune time for this column. However, I shall make it up to you here and in the next issues.” Clearly, a death in the family was not as important to Bishoff as his monthly column of trivia and insignifica. “The big news this month,” he trumpets, “—Charlton has not folded! ... I have printed these rumors to give you all the information, right or wrong, as it has surfaced.” But he could get serious. He could get angry. F’instance—: “As you know, once a month I sit down at my desk, take the conversations, articles, and notes I have gathered and assemble them into this column. In this sense, I fancy myself as a journalist. I know more than most fanzine writers that journalism demands certain responsibilities, which brings us to the case of the Hollywood Star. [The Star was a screaming supermarket tabloid, and Murray was taking issue with its front page story that Walt Disney was homosexual, to which he objected as a matter of bad taste and bad journalism.] Written by the man to ‘whom it happened,’ the editor of the paper, and certified by a sworn notarized statement. ... The subject of homosexuality raises a lot of furor nowadays. No type of prejudice in our society surpasses the antagonism felt toward homosexuals. ... I have no use for such slander, nor for a person who would brandish such a label on a headline for cheap sensationalism in hopes of making another dollar. Sometimes, I am glad organizations like Walt Disney Productions have an army of lawyers.” In the same spirit of outraged sensibility, Murray pondered that celebrated sequence in Doonesbury wherein Joanie goes to bed with Rick. Sez Murray: “The problem of artistic freedom comes down to a series of basic questions. Why does Doonesbury exist? To entertain? Whom does it entertain, and at what cost? Is it worth offending some readers to reach others or to challenge tradition in the name of innovation and irreverence? In some cases, yes. Mr. Trudeau’s use of homosexuals, simply to show that people are still human beings despite their sexual outlook, deserves great praise. [As for Joanie’s romp with Rick,] does Mr. Trudeau have the freedom to do this in the name of realism, or should he restrain himself because pre- or extra-marital sex tears at the fiber of our society’s value structure? ... I feel the newspapers should not censor Doonesbury, for [that would] keep us from knowing the facts. If Mr. Trudeau wants to shock me, let him. If he wants to risk offending me, he can suffer the consequences if I decide not to read him anymore.” But Murray “Weird Hat” Bishoff comes down in the right side of the issue: if an editor is offended, he should say so—or drop the strip. But if the editor continues to subscribe to the strip, he should let it run as Trudeau has intended. (Bishoff was often pictured in photographs that decorated the heading of his column, and in many of them, he wore a funny hat.) Light’s TBG was a grand pulsating parade, firing off in every direction exploding fireworks of news, pseudo-news, and speculation and opinion. And it made the drum major a wealthy mogul. By 1976, Light was reportedly operating a business earning a quarter million a year and pulling a salary of $1,000 a week. And then he ran into a little speed bump.

GARY GROTH ACQUIRED AN ADZINE called The Nostalgia Journal, and in his first issue, No.27 (August 1976), he discussed Light’s ruthless operating practices, designed to force all competition out of business, making TBG a ruling monopoly in the adzine business. “Light has brought to comics fandom the essence of what is wrong in the world of high finance and corporate America,” Groth began. “American business is, in some ways, akin to a pool of piranha, devouring anyone or anything that gets in its way. If expansion and profit maximization mean stomping whatever gets in the way or rolling over opponents like a juggernaut, then that is perfectly all right. Corporate abuses are many and varied, in and out of the consumer spectrum: stock raids, swindles, manipulations, unfair influence, intimidation, falsification. It’s a world coming closer and closer to merging with our own microcosm of comics fandom.” To illustrate, Groth detailed several of Light’s past efforts to crush competition, including Light’s refusal to accept advertising from fanzines that rivaled TBG. One such was Groth’s. (Light had clearly learned from Love’s RBCC experience.) Light also cancelled without refund subscriptions of people he regarded as “annoyances.” One such was Groth’s. Groth quoted from Light’s letters to the former owners of TNJ. To eliminate the competition, Light offered to buy TNJ, but his offers were usually cloaked in threatening language: if you don’t agree to my terms, I’ll force you out of business. Then Groth described a series of mysterious postcards sent to TNJ advertisers, telling them that the zine was going out of business. These missives, ostensibly from Gordon Bailey, TNJ’s editor, advised advertisers: “Please do not send us any future advertising. We will refund on your account soon if necessary.” But it wasn’t Bailey who sent the cards. And TNJ was not going out of business. Groth strenuously implied that Light sent the postcards and cited a letter that Light wrote to Bailey, apologizing for his strong-arm tactics in trying to buy the zine and for “anything and everything I’ve done.” Light also promised to reform. Groth didn’t believe Light, interpreting his mea culpa letter as an attempt to persuade Groth not to run the revelatory article that Groth subsequently published. Groth eventually morphed TNJ out of the adzine mold and into the frankly journalistic Comics Journal, a magazine of news and reviews and interviews. (Remember, by the way—although probably not at all incidentally—that I have written for Groth’s Comics Journal for over 30 years, and Fantagraphics published my definitive biography of Milton Caniff, Meanwhile. And my feelings about Light are not pure and unvarnished: he doctored the only drawing I ever submitted for the cover. He published it, but he’d changed it—subtly, as you can see in Harv’s Hindsight for August 2011, “Zero Hero”; but change is change. So I’m scarcely an unbiased observer here, but Groth’s revelations about Light are fully documented. And he was never sued for liable or slander.) Groth concluded his expose by pointing out that Light’s business practices ill-served fandom. TBG was fandom’s most widely read publication, and by shutting out the competition, Light kept his readership ignorant of other news and opinions. “Keeping an audience ignorant and in the dark is, to my mind, a supremely irresponsible and downright harmful technique of manipulation. Widespread ignorance of issues and alternatives have helped political hacks gain public office in this country for years, and consumer ignorance is just as large a problem.”

BUT GROTH’S REPORTAGE was only a speed bump for Light; and like any speed bump, it barely slowed him down. A little, maybe. The expose attracted attention to TNJ, making it visible enough to survive. But Light continued to operate TBG, although perhaps a little less high-handedly, and TBG continued to dominate the adzine field in comics fandom. Then in 1983, Light sold TBG to Krause Publications of Iola, Wisconsin for enough money, doubtless, to commence living a life of ease ever after. In his final issue, No.481 (February 4), he thanked his parents, Lavon and Jerome, who “never questioned my sanity when I told the I wanted to quit college and publish a paper about comic books of all things.” Light banked his bundle and took off for Hollywood, where, as far as I know, he has lived ever since, working once a year as a “seat filler” during the Academy Award ceremonies. (He and numerous others of the same persuasion occupy the seats of actors, directors and the like when these dignitaries leave their seats to collect awards or go to the bar or to the bathroom. Seat fillers enable tv cameras to sweep the audience, showing an auditorium full, nary an empty seat in sight, so as far as the tv audience is concerned, seating for the ceremony is at capacity.) Krause, which specialized in publishing hobby-oriented periodicals, hired the Thompsons to edit TBG with No.482 (February 11, 1983), and, taking advantage of Don’s experience as a reporter and editor on the Cleveland Press, the erstwhile adzine became a true newspaper, tabloid format: instead of a cover, it had a front page that published newsstories, not fan art. All the text throughout the paper was set in type, even the ads—which inspired criticism from one reader, who complained that he could no longer tell which sellers were idiots by the appearance of their ads. As

a hobby- and collector-conscious publisher, Krause changed slightly the name of

Light’s publication to emphasize its purpose, adding “Comics” to the title, and

so The Buyer’s Guide became The Comics Buyer’s Guide, and TBG morphed

into CBG. In devising the publication’s new logo, the words of its title

were superimposed upon a speech balloon. Beautiful. And so we entered what I think of as the heyday of CBG. With a professional journalist at the helm and typography throughout, CBG looked and behaved like a grown-up newspaper. New columnists showed up—Tony Isabella, Heidi MacDonald, Bob Ingersoll, Peter David, Mark Evanier. The paper reported industry news, including censorship cases and similarly alarming events. And Don reviewed comic books with a flair for the turned phrase and an eye for idiocy as well as excellence. CBG was undeniably better journalism, but it was not as much fun as TBG. Light’s TBG was not unalloyed terrible. Apart from its nightmare appearance, it was full of news and comment and fan art of stunningly varied degrees of incompetence. TBG jammed its 25% news hole with clippings culled from newspapers and magazines, mostly, pasted onto pages, interspersed with typewritten items and articles supplied by off-again-on-again correspondents. Columnists came and went. David Scroggy did a regular report, West Coast News and Reviews. Martin Greim, also a fan artist of modest distinction, produced Crusader Comments. In Media Reports, David McDonnell reviewed tv, movies and comics. Shel Dorf interviewed famous cartoonists. For a brief time, Don Rosa opened an “annex” to his Information Center, which was, still, at that time, a regular feature at RBCC; but loyalty to Love and Van Hise presumably prevailed, and Rosa soon closed the annex. The big news and information department was the Thompson’s Beautiful Balloons. The column logo was different every time: the column often ran for several pages, and a new fan-drawn logo appeared at the top of each page. The BB pages frothed with newspaper and magazine clippings as well as typewritten lists and reviews. And letters. BB had its own letters department.

THANKS TO ITS ENTHUSIASTIC COLUMNISTS and contributors, TBG was a flowing fountain of information about cartooning, a constantly bubbling watering hole for all of fandom, a hitching post where we all tied up once a week. The pages and pages of ads selling old comic books and new attracted some, but others of us read the columnists. In Crusader Comments, Greim interviewed Lee Falk, creator and scripter for Mandrake and The Phantom. Among the things he learned: Falk designed the Phantom’s costume, but did not specify color. He thought that if he had made the decision, he would have colored it green to blend with the jungle foliage and provide camouflage. Falk always wanted to have Mandrake and the Phantom meet, if only to shake hands; but the syndicate nixed it: in some cities, the strips appear in rival papers. On another occasion, Greim’s Crusader Comments column was devoted to Bob Cosgrove’s report on a meeting with Frank Thorne, who had just started drawing Roy Thomas’ Red Sonja. Asked why he left DC, Thorne said that much as he respected Joe Kubert and enjoyed working for him, he got tired of hearing how much his style looked like Kurbert’s. Said Thorne: “Neither Joe nor I can see the resemblance.” Funny. I once placed Thorne in the “Sickels/Caniff school” of cartoon art, but when I asked Thorne about it, he said he worshiped at the alter of Alex Raymond. More from Cosgrove: “Frank expressed pleasure at working for Marvel, and admiration for writer Roy Thomas. He added that Red Sonja has brought him an upsurge in fan mail, from several letters a year to several letters a week; though he reads all his mail, this also means further demands on Frank’s time. Interestingly, when Frank first drew Sonja, he was given only the Howie Chaykin version as a guide, and that explains the large lips on the first Frank Thorne Sonja effort.” Light also published letters in TBG Mailbag. Here’s a memorable one from Joe Kubert: “Dear Alan: A personal ‘thank you’ for your great columns describing the formation of my school. The school’s successful opening is a direct result of the fans who read The Buyer’s Guide. For years, I’ve known they were ‘out there’ —but not until now did I realize the heavy numbers, or the tremendous warmth that’s generated by them. I hope you feel some personal satisfaction for being implemental in the schools creation. You should.” And here’s a sampling of the art that festooned TBG’s pages. In no particular order, just as TBG itself was assembled.

.

BACK AT KRAUSE, for the next dozen years, CBG’s evolution all but ceased. Until 1992. In 1991, a formidable competitor appeared: Wizard was published on glossy paper and focused on comic books and movies and interviews; it was monthly, but every issue included a price guide. CBG modified its appearance in 1992, converting its front page to a color cover. Every issue was jammed with news and reviews. To ease the workload on Don, Brent Frankenhoff was hired as his assistant in September 1992. But in 1993, the comics industry was on the cusp of a disastrous collapse. And so was Don Thompson. I started contributing a column, called Rants & Raves (surprise), with No.1067 (end of March 1994). But the big change in CBG came on Monday, May 23, 1994 with the unexpected death of Don Thompson at age 58. His widow, the remarkably resilient Maggie, took the reins with No.1074 (June 17), which was in production at the time and almost ready to go to press. At the last minute, Maggie added an obituary for her husband. They had just returned from a weekend in Madison where they’d gone for the graduation of their son Stephen from the University of Wisconsin. It was, Maggie wrote, “one of the most wonderful weekends of our lives. ... We were all feeling great, and there was a lot of hugging and kissing and sharing and relaxed family time. We were exuberant for the entire weekend, and Don and I laughed and talked happily all the way on the drive back home to Iola from Madison.” They spent Sunday evening watching favorite tv shows. The next morning, they followed their usual routine: Don arose first, took his medications, and went back to bed for a few more winks while Maggie got her breakfast and showered. When she went to awaken Don, he wasn’t breathing. She tried CPR, then phoned the ambulance service, then resumed CPR. Don never regained consciousness. Cause of death was presumed to be congestive heart failure. Don had already written his Comics Guide column for No.1074, doing several reviews of new comics. While criticizing one of the books for its cavalier attitude about spelling, Don went off into a witty apostrophe about how no one seemed to care about grammar or spelling anymore. Don, a whose profession was words, cared. And he was disgusted that even the latest Merriam-Webster dictionary didn’t care; it contends, Don said, “that any word spelled and used any way by anyone, anywhere, is okay.” He ends the column right after that, saying: “We have seen the future, and it is determinedly stupid.” Don began his columns each week with some sort of quotation. This column’s quotation was terribly ironic. He quoted Herbert Spencer: “Time: that which man is always trying to kill; but which ends in killing him.”

MAGGIE WOULD CONTINUE as the solo editor of CBG for several years until John Jackson Miller took it on; and then, Frankenhoff. In both instances, however, Maggie continued as senior editor, a sort of super-advisory role. Soon after Maggie took over, the evolution of CBG resumed, but now, more and more, in a flailing about mode, as if desperately in search of a new niche because the Web was siphoning off advertising of vintage comics. CBG experimented with coverage of manga and then games and toys. Meanwhile, the comics industry itself seemed about to limp into oblivion. With No.1162 (February 23, 1996), the tall rectangular tabloid shape was abandoned for a smaller square configuration to conserve paper. (The square meant the pages were somewhat smaller than previously, using less of the expensive newsprint paper.) The industry seemed to revive after the turn of the century, and news displaced cover art on CBG’s front page with No.1482 (November 23, 2001), but three years later, with No.1595 (August 2004), CBG gave up being a weekly newspaper and became a monthly magazine with a slick full-color cover. In an effort to displace Wizard and stimulate newsstand sales, CBG also began running a price guide for current comics in every issue. In his recitation of the history of TBG/CBG at ComiChron.com, John Jackson Miller, who graduated through the ranks of CBG from writer to contributing editor to managing editor to editorial director (first of Krause’s comics division then of the company), departing finally in 2007, noted that it became apparent that “nostalgia was the unifying factor in CBG’s readership,” and the magazine added columnists who focused on the fond past: Craig “Mister Silver Age” Shutt and Andrew “Captain Comics” Smith. They fit right in to the new editorial concept—features. I don’t think attempts to enhance newsstand sales paid off. Years ago, I traveled around a good bit, and wherever I dropped into a comics store, I’d look for CBG in vain. Surprised, I asked about it, and invariably was told that none of their customers wanted it. In the comments postings after Miller’s history, Daniel Veltre, who operated a comics store for 20 years, said the same. My column ceased with CBG’s conversion to magazine format. I submitted some, but none were published. No one explained why, so I was left to dope it out for myself. I was too long-winded, I suppose, for the condensed magazine version of what had once been a voluminous newspaper. As a monthly magazine, CBG had to forego coverage of hard news because so much of it would no longer be timely when an issue was published (as long after going to bed as two months). It was assumed, I suspect, that the industry’s news would be available to everyone as it broke on the Web; I’m not sure that ever really happened. (Name the website where you can find what CBG once offered in news coverage.) Converting CBG from news to features was, I think, a signal mistake: no other publication in comics fandom came out as often as the weekly incarnation of CBG. As a news vehicle, CBG was ahead of the competition. In 2005, the magazine launched a website, CBGxtra.com, that promised to cover breaking news, but it seemed to me never to offer much news; instead, it announced the features in forthcoming issues and flogged special CBG publications. It was, in effect, the magazine’s promotional arm; eventually, it would serve as a sort of storage shed. Another mistake, I think, was in assuming that the audience for CBG was increasingly people who collected comics as investments rather than simple fans of the medium. Pandering to the investors, the magazine stepped up coverage of auctions and evolving prices (“Amazing Fantasy No. 15, the first appearance of Spider-Man, sold for $1.1 million March 7") and produced the Standard Catalog of Comic Books, a monster price guide. (It was also a detailed listing of comic books by number and date of issue, and it included other incidental information of value to historians of the medium.) Alas, investors found their prey on eBay, not in the pages of a monthly print magazine. They deserted CBG, but there probably weren’t many of them to begin with. By appealing to them, CBG had become a niche publication for the tiniest of niches. CBG had given up the thing that had made it unique in fandom at the time—news coverage—in order to court a small audience that would soon abandon it. No wonder it died. And then there’s the pernicious effect of private equity operations under which Krause had been working since acquired by a private equity firm in 2002. We learned during the recent presidential election that private equity firms are not at all hesitant to shut down businesses if the profits aren’t there. And with CBG, the profits had been shrinking for several years. Advertising had all but disappeared and, as Miller points out, “since ad pages determine the number of editorial content pages, subscribers saw less of CBG in their mailboxes.” Deterioration set in steadily. “Color pages became black and white, glossy paper became newsprint.” It was sad to witness. In assembling the information for this report, I wandered through a few old files (as you can tell from the illustrations we posted a few paragraphs ago), and I was reminded of how important and vital TBG/CBG had once been. As with my friend Jim Engel, the weekly arrival of TBG was a highlight of my week. Not in my fondest dreams had I ever imagined getting so regular a fix in my addiction to comics. Engel captures a lot of that feeling; to wit—:

"So THE

BUYERS GUIDE is coming to an end after 40 years,” he wrote. “TBG/CBG was

for me (as I'm sure it was for many of you) a true institution in my life, for

a long time. I think my subscription began with the 5th or 6th issue, and it

was a much-anticipated highlight of my week every week. Alan Light published a

good amount of my stuff (weirdly, but perhaps most significantly, those little

"IT'S HERE!" cartoons that ran in the address box), including the

DRAWN version of "FANDOM CONFIDENTIAL"... He published TONS of my

friend Alan Jim Hanley's work (and we were all richer for it), as well as work

by my friend Russ Maheras...great columns (Don & Maggie Thompson, Cat

Yronwode, Shel Dorf), great strips by a wide variety of excellent cartoonist

(Fred Hembeck, Terry Beatty, R.C. Harvey, Eddie Eddings, George Erling... I

apologize for the tons of guys I'm forgetting)... Chuck Fiala, Russ Maheras,

Roy Kinnard & I once took a road trip to Alan Light's house in East Moline,

and saw the whole TBG set-up (Alan barely tolerated my smart-assedness)... when

Alan got rich selling it, the CBG era began under the most qualified people

there could be—Don & Maggie. I enjoyed their friendship via the paper

(where they too printed my stuff, and supported Chuck & I and our friends

Jerry Sinkovec & Mike Tiefenbacher (of THE COMIC READER) in our various

endeavors (most notably, when Mike, Chuck & I had our great moment—the publication

of the FUNNY STUFF STOCKING STUFFER, intended to kick off our revival of the DC

Funny Animals in a new line of kids books) ruined by DC & Dick Giordano

jacking us around and re-writing all our dialogue at the 11th hour. I sent

D&M a xerox of OUR version, and they reviewed the book explaining our

plight, and praising our intended work over the published one. We felt somewhat

vindicated, and I will be forever grateful for THAT)... I enjoyed their company

(and a GREAT, eclectic collection of other comic industry folks) at several of

the CBG PICNICS they graciously held in Iola... this truly DOES end an era... a

bridge from my teenage to middle-aged years... sure, I can still have great

conversations with Maggie when I run into her at cons, but it'll be a bit weird

to think there's no CBG anymore... Alan, Don, Maggie— THANK YOU!"

AT THE END OF MILLER’S history of the magazine at ComiChron.com, one of those who comments is Alan Light, who says: “Thanks, John, for this good retrospective. It seems like another lifetime ago, another person actually, who founded and published TBG. Months go by went I don't even think about it, but today is a sad day for me. But everything ends. What a great run it had.”

NOT EVERYONE HAS UNADULTERATED HAPPY MEMORIES. From James Van Hise, who navigated RBCC into its grave and is therefore somewhat experienced at magazine deaths and hence oughta know better than most what kills publications, came this comment: “Well this is no surprise. Page counts in CBG during the last 2 years have averaged less than 60 pages. I even told them 2 years ago that it was obvious the magazine would fold because at 60 pages it wasn't very appealing to subscribers any more, nor to comic book stores to carry. Its problems obviously began years ago when they started slashing the magazine's budget. ... “In the 1990s, after Don Thompson died, CBG stopped reporting on any comics news which might make the comic book industry look bad. Marvel's bankruptcy problems were covered by printing Marvel press releases. CBG stopped reporting on publishers that owed money to writers and artists. The letters column, which used to be a clearing house for professionals to air their opinions on the industry, became just another fanzine lettercol with nothing of significance. When a major independent publisher in Florida was months behind paying contributors and was clearly in deep trouble, CBG reported nothing. Even when that company folded after months of public acrimony, CBG just published a squib saying that the company had folded, with no recounting of what led up to it. CBG had made itself inconsequential years ago. “Twenty years ago The Comics Journal had regularly criticized CBG as being an uncritical cheerleader for the comic book industry. While I didn't believe it was true then, that is exactly what CBG became in the last 15 years. CBG had become so meaningless that there was nothing left to miss. I feel like CBG really ended years ago. In the 1980s when it was weekly, each issue was eagerly awaited to see what the latest important industry news was. That had stopped even before the Internet supplanted it. CBG chose its own path to oblivion. I miss the CBG of 20 years ago, not what it was in recent years when it was a pale shadow of what was.” After posting this in the Comments section, Miller chimed in and disagreed with some of Van Hise’s assertions. Much of what fouled the air for Van Hise happened on Miller’s watch, after all—so what do we expect? Miller says most of the business news was covered in Comics Retailer, another Krause publication. And he claims better “footwork journalism” developed when the budget expanded. But Don Thompson managed pretty decent reportage on a shoestring, so money isn’t everything. (Helps, though.) Journalistic will and expertise counts for more. Miller admits that some of what Van Hise complains about was brought about by decisions in “the front office”—“and I regret just about everything about it.” Mostly, from my observations of CBG over the years, I agree with Van Hise. Except that even before Don’s death, they’d shied away from reporting bad news about the industry. When Jim Shooter was fired at Marvel in May 1987, for instance, CBG could find nothing to report about why he’d been fired. Don always refused to print rumors, and for the first couple weeks after the firing, rumor was about all their was. But eventually—somewhere—someone had to know facts about it. If so, we never read about them in CBG. In No.704, the week after announcing Shooter’s firing, CBG published an editorial that attempted to counter all the nasty rumors about Shooter’s conduct as Marvel’s editor-in-chief by pointing out the good things he’d achieved. Balance, at least, if not all the facts. Still, I wrote in high dudgeon to accuse Don and Maggie of conducting cover-up.

BUT WHAT OF MAGGIE? She and Roy Thomas are the last of the pioneers in comics fandom who are still active in it. She and Don met in 1957 at a picnic of sf fans. Maggie, age 14, was with her mother, another sf fan; Don was 21, a journalism student at Penn State where he had been president of the sf society, and on the basis of their sf interests, the two young people found they also liked comics. “We hit it off right away,” Maggie remembered in her obit for Don. “Don and I spent the day talking. We talked about science fiction. We talked about fantasy. We talked about our favorite sf artists. We even talked about comic books. Amazingly, our tastes were virtually identical. ... He was great.” She then shifted to a wholly unrelated but revealing topic: “When he first encountered Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, he thought he’d never be able to afford to buy a copy, but he was so impressed by the play that he copied it out in longhand. He joked in later years by admitting that he’d bogged down before finishing the task. That he would start such a project was the sort of thing that drew me to him.” “We started corresponding,” Don recalled in a 1992 interview quoted in Schelly’s history of fandom, “and I visited her a few times. Our relationship grew out of that.” They married in June 1962 after a two-year engagement. She was an English major at Oberlin College, and after they were engaged, Don took a bus to see her every weekend. Maggie graduated in 1954 and worked as an assistant children’s librarian in the Cleveland Public School until she quit to have children (Valerie and Stephen). Don had started his 22 ½ year career at the Cleveland Press. A mild disagreement hovers over which of two fanzines was the first in comics fandom. The Thompsons published Comic Art No.1 in March or April 1961; Jerry Bails, a professor at Wayne State University in Detroit, published the first issue of Alter-ego in March that year, most of it written by Bails and a twenty-year old English and history major at Southeast Missouri State College, Roy Thomas. “Jerry didn’t get his copy of our Comic Art until April,” Don said, explaining the dispute about which was first; “so he figured that Alter Ego had come out ahead of us.” Thomas is still at it: after a long career writing and editing at Marvel and then freelance writing (including helping Stan Lee on the Spider-Man newspaper strip), Thomas revived Alter Ego (with a capital E) in the summer of 1999, and remains at the helm. Comic Art came out irregularly. “We never printed a publishing schedule,” Maggie once said. “So no issue was ever late.” They published a number of excellent historical articles. Comic Art printed the first articles on Carl Barks by Malcolm Willits and Mike Barrier. Willits had sent Barks a letter requesting an interview, and the Duck publisher forwarded the letter to the Duck artist. “Carl thought it was a joke from the guys in the office,” Don said, “because he had never receive any fan mail before.” “We got letters of comment from people like Harvey Kurtzman and Crockett Johnson,” Maggie added. Comic Art ran up seven issues until expiring in 1968. By then, the Thompsons were having more fun producing another fanzine, Newfangles, which they started in March 1967 to focus on fans and their activities rather then the comics industry. Maggie explained the zine’s name: combine “New Fan Angles” and “newfangled.” Great name. But not all the news in Newfangles was about fans. Newfangles No.10 (March 1968), Maggie recently recalled, reported winners (including Will Eisner) of the National Cartoonists Society awards; deaths of cartoonist Rudolph Dirks (91) and mystery writer and sf editor Anthony Boucher (56); variant pricing of 15 cents of Gold Key comics in New York City and on the West Coast; publication of Zap Comics ("We blithely admit we didn't understand it, but we dig it. Crumb, says [Bill] Spicer, draws like a retarded Basil Wolverton. True." Sigh. Showing our age and non PC-ness, even then.) Newfangles hit its 54th issue in December 1971, and when Don and Maggie announced they were ending the publication, that kid from East Moline offered to continue publishing it if they’d provide the content. They said no thanks, and he started TBG. Soon, as we’ve seen, Don and Maggie were doing Beautiful Balloons in TBG. Miller refers to Don and Maggie as “the George and Martha Washington of comics fandom,” a deserved honorific. I like to think of Maggie as the den mother of fandom, a title someone else conferred years ago. So what, now, of the comics and sf fan who made a life’s work out of her hobbies and amusements? Maggie soldiers on, putting a smiley face on the otherwise dim prospect of the end of much of what she’d worked at all her adult life. At her blog, maggiethompson.com, she writes (quoted here in italics) about her forced departure at the demise of a publication she’s devoted years to fostering: It's been a delight to have had the opportunity for the last three decades—plus a prior decade with the magazine's creator, Alan Light—to communicate so wonderfully with comics collectors, comics fans, and comics professionals. Over the years, we were able to reach out in a variety of ways, including coming up with the term "Done in One" (to identify stories told completely in one issue, announced in CBG for April 5, 1996). We also helped create a trade journal that was the inciting force behind the Free Comic Book Day outreach project that Diamond Comic Distributors implemented and that continues every May. Don and I were excited by Krause Publications' challenge of revamping an advertising newspaper into a full-fledged information resource. It has been an energizing challenge to adapt to the changes of the field, as it grew from a niche interest to something popular enough to command the covers of national pop-culture magazines. How about me? Hey, the same week that Krause Publications announced the end of CBG saw the first installment of my contribution to a new outlet for me: a monthly post on Comic-Con International San Diego's "Toucan" blog. Hope you enjoy it!

AS A PARTING from an enterprise she’s spent so much time, energy and love on, these two short paragraphs seem a little flat, almost perfunctory. Maybe she was still in shock; we don’t know if she and the rest of the CBG staff knew about the falling curtain much before it actually fell, ending, as it descended, the magazine’s last act. If these are the first words off her keyboard after getting the news—well, yes, shock may be the word to use. But there’s also a kind of weariness in her words. As CBG began to fail over the last months, Krause management probably did a lot of hand-wringing around the office. Witnessing that sort of thing’ll wear a person out. But she seems determined to keep on keeping on, sending us all off to her new endeavor. At “Maggie’s World,” the aforementioned blog within a blog, Maggie posted her first effusion: all about “Why I Love Comics,” it included an excerpt from a fanzine published by her mother and father (Betsy and Ed Curtis, a college professor) in 1949. Written by Maggie’s mother (a big Pogo and Walt Kelly fan, a trait her daughter inherited), it was inspired by the growing furor about comics—whether they were bad for young readers (maybe they even encouraged criminal or other kinds of deviant behavior). It’s a little dated perhaps, but everlastingly cogent, too; here it is (in italics):

Best Sellers So many friends have asked me in grim or pathetic tones, “Do you approve of comic books?” that I feel I must make some public statement which I can hand out to such gals and run for cover while they are reading it. The question, of course, makes about as much sense as “Do you approve of books?” but it is hard to say this without being thought impertinent or irrelevant by the questioners. Comic books are naturally appealing. Pictures, like stage drama, are more interesting than mere print. The rapid action of most of the plots and the excitement of adventure hold a child’s attention in comics as they do in western movies. Passages of slow moving description are not necessary when the action is presented in pictures. Many objections to comic books have to do with their subject matter. It is certainly not surprising that the children of avid whodunit readers should like detective comics and that children who are offered few fairy tales should satisfy their craving for fantasy with Superman and the Green Lantern (whose doings are in their way more moral than “Big Claus and Little Claus” and most of the contents of the Red, Violet, and Blue Fairy Books). And comics are cheaper than “good” fantasy—the Oz books are still retailing at $2. I wish I could afford to supply Judy [my nickname in 1949—Maggie] with books which she would enjoy more (and there are plenty) than comics. Some mothers object that their children bury themselves in comics and no longer spend time in active “fantasy play” with their friends. Cops and robbers are supposed to have given way to afternoons in the corners of the sofa with piles of comics. Comics are also supposed to have replaced “real literature” in the lives of our young. I can see no reason why there should not be a “real literature” in comic form. It is slow in taking shape, but the work of such artists as [Morris] Gollub, [Dan] Noonan, and Kelly give promise that comics can be good reading for children. Certainly these stories have been acted out by children—I’ve seen and heard it. Comic art is a young art. When better comics are printed, kids will read them. I have considerable faith in the taste of children: they like good fiction better than bad. But as long as they are offered only mediocre, bad, and worse, in a form that is more appealing and cheaper than good stories, they will continue to read mediocre, etc. I don’t know how to get good comics on the market any more than I know how to encourage the writing and publishing of other good books for children—but I am hopeful that artists and publishers will come across in time for our grandchildren to have lots of fun at a very moderate cost. The largest number of periodicals in our household seems, in spite of culture and refinement, to be made up of comic books. Most of our collection are really intended to be comic—that is, funny. Most of them are published by the Dell Publishing Company and portray the doings of urban children (Little Lulu, Henry) or urban animal child-substitutes (Walter Lantz, Merrie Melodies, Walt Disney, Tom and Jerry, etc.). The cream of the crop were, in the recent past, Our Gang, Raggedy Ann, and Fairy Tale Parade (still Dell) with the excellent drawing, interesting stories and amusing dialogue of Walt Kelly, Dan Noonan, and Morris Gollub; but these three gentlemen seem to be deserting the comic book business and two of the publications are no longer in existence. The least painful comics still on the market other than the ones I have just mentioned seem to be the Disney ones. I should recommend a recent special, still on the stands in Canton—“Donald Duck in the Treasure of the Andes” [Dell Four Color No.223, actually “Lost in the Andes” by the then-anonymous Carl Barks]—as the best of the recent dime publications for the four- to eight-year-old. We do seem to have accumulated a number of Superboy, Wonder Woman, and Bat Man opera, but these do not hold the attention of our six-year-old for more than five or six readings. Even Raggedy Ann can beat that.

***** AND ON THIS EMINENTLY REASONABLE NOTE, we bid adieu without further ado to the Comics Buyer’s Guide, the 42-year-old veteran of comics fandom, once vital, lately a fossil; and we wish Maggie, the eminently reasonable den mother of fandom, the best in whatever she may choose to do. Whatever it is, I hope it brings her to places where I can run into her and exchange lies about our grandchildren.

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted TWO ISSUES

HAVE ENGAGED the hot sweat attention of the so-called “news” media over the

past month—the mass murders at Newtown, Connecticut, and the Fiscal Cliff over

which we were destined to tumble (and still are). Both engaged the imaginations

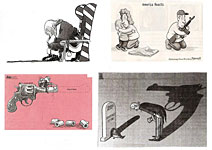

and anger of editorial cartoonists. Our first visual aid reflects the initial horrified reactions at the news of the deaths at Sandy Hook Elementary School on December 14, less than two weeks before Christmas. Chip Bok starts us off at the upper left: it’s the Christmas season, season of joy and of giving—the season of children—and he captures the agonizing irony of inflicting this season with this horror in his picture of Santa Claus grieving. In poignance, Bok’s picture is unrivaled; and its message is emphasized by the focus on the innocent children who have died. Next in clockwise order is Clay Bennett whose mute tableau dramatically poses the rival factions whose feelings are aroused by the tragedy. The echoing imagery makes a telling contrast. I can’t make out the signature on the next cartoon (sorry), but its haunting imagery silently characterizes the society as a gun culture whose grief, while real, is deeply equivocal. Finally, another cartoonist whose signature I can’t read suggest that our usual responses—just shortening the barrel of the gun—do not attack the real problem, the gun itself. Gun supporters take some deserved lambasting in the next batches posted here.

At the upper left of our first exhibit, Jimmy Margulies provides an accurate picture of the reaction of the National Rifle Association, crying crocodile tears. In the ancient proverb, a crocodile moans and sobs like a person in great distress in order to lure a man into its reach, and then, after devouring him, sheds bitter tears over the dire fate of its victim. Hence, “crocodile tears” indicate gross hypocritical grief, make-believe sorrow. Probably, that characterization is a trifle unfair; but editorial cartoons best accomplish their purpose by being one-sided. Mike Luckovich, on the other hand—next on the clock—isn’t being unfair by pointing out the ludicrousness of gun owners having assault weapons for hunting. But I purely love Pat Bagley’s politically barbed comment at the lower right. A deliciously perverted interpretation of a gun enthusiast’s caution about weapon handling applied to cunningly reveal the nature of the NRA’s political power—its, er, “hold” on the machinery of government. Finally, Randall Enos furnishes a suitably ironic comment on NRA executive Wayne LaPierre’s absurd contention that “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” Enos’ message is not as dependent upon blending word and picture as are the other cartoons we’ve looked at so far, but it’s a fine ironic reminder of the gun tragedy of last winter. In the next quartet of toons, Rick McKee leads off on the next phase of the gun dilemma: how to legislate gun violence out of existence. Part of the problem is simply cultural: our entertainments—Hollywood movies, tv, video games—all champion gun violence. And against those models, what effect can the sober instructional posture of NBA have? The excitement in our entertainments trumps sobriety every time. In the next cartoon, Nate Beeler wonders whether it’s even possible to have a rational discussion about gun laws, his heroically exaggerated portraits of the debaters emphasizing their irreconcilable positions. And Jim Morin, just below Beeler, deploys the much over-used “cliff” metaphor of the past month, producing an image that suggests that the our attitude about guns has us teetering on another kind of cliff over which we will inevitably fall unless, somehow, we act. Finally, Ted Rall, ever ready to carry sarcasm angrily to the ludicrous extreme that reveals the inherent absurdity of any inherently absurd proposition, provides a sequence of conversations among gun proponents that gets progressively more idiotic—but also, as NRA’s LaPierre demonstrated, a near approximation of the actualities we face in trying to control violence and guns in the face of vehement opposition by criminally misguided gun proponents. Some of the latter fervently believe that they must have arsenals of assault weapons in the closets of their homes in the event that the government sends armed marines to deprive them of liberty and life. As one wag observed, if that were to happen, our way of life will have deteriorated so badly that gun ownership will be the very least of our concerns. But before we pursue more cliff notes, let me pause to cogitate about guns and violence.