|

|||||||||||||||||||

Opus 303 (Christmas 2012; or December 20). This year, December has five Saturdays, five Sundays, and five Mondays. Just like that—in a row, one after the other, five times. This happens, we were assured by some Internet pontif, only once every 824 years. It means, of course, that we’ll be going over the fiscal cliff as we have every 824 years. And everyone’s taxes will rise—except John Boehner (pronounced Boehner), who, as usual, dodges the bullet.

When I told my lawyer daughter that December had five 3-day weekends, her incisive legal mind engaged immediately: “Great!” she exclaimed; “No one had better complain this year about not having enough weekends for Christmas parties!” Alas, the Web oracle was lying. Just as the Mayans lied about the world coming to an end this year (on December 21, the digital prognosticator was fibbing about the 824-year interval. December has five Saturday-Sunday-Monday weekends every time December 1 falls on a Saturday. That’s happened four times since 1990. Besides, even five Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays in December were not enough to enable me to assemble my anyule shopping list of Suggested Good Cartoon-Related Books to Buy in time for you to pass the list on to your spouse as suggestions for what to put under the tree for you. And so, once again, you should regard the List as suggestions for how you may spend the Christmas stocking money your Great Aunt Debra gave you. Ten books about comics, cartooning, and cartoonists, plus one graphic novel (listed immediately below); and 14 funnybooks (ditto), plus the year’s very best comic book series, Punk Rock Jesus by Sean Murphy. The longest, most detailed review is of Sean Howe’s new Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, during which I wander off his gossipy terrain into the well-trammeled sideroads about Marvel and its minions, including an examination of the original art for the first Spider-Man story—the only documentary evidence we have about who, Stan Lee or Steve Ditko, was the shaping genius. We also get a report on how S. Clay Wilson is faring after his accident in 2008, and we bid farewell to Spain Rodriguez and Jeff Millar. Here’s what else’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Katzenjammers Are 115 Steve Ditko Surfaces Zuma Drops Some of His Suits Against Zapiro Barney Google’s Back Topps Discontinues Bazooka Joe Stan Lynde Saddles Up for Ecuador James Gunn Sexist S. Clay Wilson’s Slow Recovery (Book Review: The Art of S. Clay Wilson)

EDITOONERY Some of the Best of the Month Dana Summers Laid Off RANCID RAVES GALLERY Stereotyping

BOOK REVIEWS Sean Howe’s Untold Story of Marvel Comics (Ditko and Lee on Spider-Man: Documentary Evidence) Comics about Cartoonists

BOOK MARQUEE The Lost Art of Zim Matt Baker: The Art of Glamour Marie Severin: Mirthful Mistress of Comics Totally Mad: 60 Year Anniversary Mort Drucker: 50 Years of His Art Ralph Steadman’s Extinct Boids

GRAPHIC NOVEL Lover’s Lane: The Hall-Mills Mystery

COLLECTOR’S CORNICHE Allen Saunders’ Self-portrait

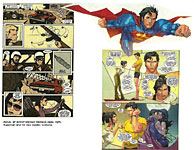

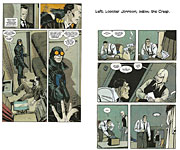

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE What I’m Readin’ Lately Batman: The Dark Knight, nos. 10-11 Happy Wolverine Max, no. 2 Black Kiss II Daredevil, nos. 18-20 Hawkeye, no. 4 Superman, no. 14 Lobster Johnson Where Is Jake Ellis The Creep Bad Medicine, Criminal Macabre The Saint (Eduardo Barreto)

Punk Rock Jesus: The Best Comic Book of the Year

PASSIN’ THROUGH Spain Rodriguez Jeff Millar

PUNDITRY Campaign Finance: A Novel Notion by James Carville

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

The Katzenjammer Kids are 115 years old this month: Rudolph Dirks introduced them to the world on December 12, 1897. For the first episode, there were three Katzies. What happened to the other rowdy kid? Some speculate that he was just a random neighbor kid, not one of the family, so he wandered off. The strip is still going, by the way—which is the chief reason for taking notice here. New stuff, all created by Hy Eisman (who also does the Sunday Popeye).

GLIMMERS FROM THE CAVE Steve Ditko has long enjoyed the reputation as comics' J.D. Salinger, said Chris Arrant at robot6.comicbookresources.com, “—rarely releasing new work and eschewing the modern notion that creators engage with fans and press. Stan Lee, he's not,” Arrant concludes with what I imagine must be a satirical sneer: Ditko, who had more to do with creating the Spider-Man character than Lee, quit Marvel ostensibly because he could no longer get along with Lee, who, Ditko realized, was claiming all the creative credit for the Marvel Universe. Since then, Ditko has maintained a stoic silence on his life and his career at Marvel. But recently, Arrant reports, “Ditko has written several essays about Spider-Man in various independent publications. ... Earlier this year, Ditko published an essay called ‘The Knowers & The Barkers’ in his comic book #17: Seventeen, and a second just popped up in the comic fanzine The Comics Vol. 23 No.7, published by Robin Snyder, Ditko's former editor at Charlton and Archie. This second essay, ‘The Silent Sel-Deceivers,’ reportedly runs a page and a half and features Ditko addressing the creation of Spider-Man. “In this essay,” Arrant continues, “Ditko discusses the original take on Spider-Man by Jack Kirby before Ditko was asked to come up with his own interpretation of Lee's idea for a spider-based hero. These pages, which Ditko says number five in total, have never been published or seen on the original art market. Lee, in a 2000 interview for Greg Theakston's The Steve Ditko Reader, said he rejected Kirby's work as ‘too heroic.’ On several occasions, Kirby later claimed he contributed many ideas that ended up in the character's formal debut in 1962's Amazing Fantasy no.15. Ditko talks about that in this essay, as well as Lee's own contributions to the Spider-Man concept.” Ditko’s fugitive essays, which promise much, are often disappointing. I’ve read a smattering of these over the years in Snyder’s newsletter, and Ditko employs a high-fallutin’ vocabulary of abstract expressions and arcane buzz words that he often fails to fasten securely to the actualities he seems to be discussing—like what, exactly, was his contribution to the invention of Spider-Man. He garbles on about “art” and “creativity,” championing both and sometimes asserting, through a generous deployment of these terms, that he was the creative artist on Spider-Man. I don’t question that, but I always hope he’ll say as much in unequivocal, ordinary language, minus Ayn Randian locutions. Details on ordering the books containing these essays, and seeing Ditko's modern cartooning work, can be found at the Ditko Comics Blog. And on the other side of the $ubscribers Wall, I report on my examination of the original art for the first adventure of Spider-Man, wherein pencil marginal notes make revelations.

ZUMA VS. ZAPIRO SOME MORE In order to “avoid setting a legal precedent,” South Africa prez Jacob Zuma recently withdrew his claim for damages against cartoonist Jonathan “Zapiro” Shapiro. Zuma had sought R5m in damages for defamation and impairment of his personal dignity over the publication of Zapiro's Lady Justice rape cartoon in 2008. The cartoon depicted Zuma loosening his trousers while Lady Justice was held down by Julius Malema, president of the African National Congress Youth League at the time, Congress of South African Trade Unions general secretary Zwelinzima Vavi, South African Communist Party general secretary Blade Nzimande and ANC secretary-general Gwede Mantashe, all saying: "Go for it, boss." (We posted this cartoon in Opus 263; scroll down to “Zapiro: Thorn in the Side.”) Zapiro and Zuma have often clashed over the numerous satirical depictions of him, said Bekezela Phakathi on bdlive.co.za, adding what Zapiro said in addressing the Cape Town Press Club after Zuma dropped his suit: Zapiro said Zuma always tried to play the victim and "he is a master at it. ... He has a number of defamation suits against a lot of people and he has not dropped them. He has not, by the way, dropped another defamation suit against me which stands at — I am told by my lawyers — at R10m ... the figures are stupid ... they could never get these kinds of amounts, and it is all about intimidation. But I think South African media people are feisty and thank goodness for that," he said. In October, Zuma's spokesman, Mac Maharaj, said the decision to withdraw the defamation suit against Zapiro was informed by three major considerations, Phakathi quoted: "Whereas the president believes that in an open and democratic society, a fine and sensitive balance needs to be maintained between the exercise of civil rights such as freedom of speech, and the dignity and privacy of others, that balance should be struck in favor of constitutional freedoms.” He added that Zapiro's views on Zuma "did not necessitate a comment from the Presidency.”

BARNEY TO RETURN TO THE HILLS Barney Google, once the nameplate character in the strip now known as Snuffy Smith, will be making one of his periodic returns to the strip soon. John Rose, the current master of the revels, brought Barney back briefly last February; at the time, it had been about 15 years since the guy with the goo-goo-google eyes had been in the strip. Rose frequently makes appearances before civic and corporate groups, and in one of them recently, someone asked where Barney and Spark Plug (Barney’s race horse) were. Said Rose: “I thought it would be fun to bring the characters back. I approached Brendan Burford, King Features’ comics editor, with the idea and he was all for it. So away we went!” The entire robust history of Barney Google from Spark Plug to Snuffy is retailed in Harv’s Hindsight for December 2009 (on the other side of the $ubscribers Wall, naturally).

NAME-DROPPING AND TALE-BEARING Steve McGarry, a Brit now living in this country and a former prez of the National Cartoonists Society and creator of Biographic and TrivQuiz on GoComics, is bringing to these shores his “western” comic strip, Badlands, which started in 1988 and ran for 12 years in Britain. The strip features the puerile antics of Marshall Mask and his “motley mob of maladjusted misfits”; the strip will appear, I gather, at the GoComics website. Topps recently announced the discontinuation of its long-running Bazooka Joe comic strip, since 1954 a popular enclosure in its bubblegum packaging. The strip has a storied history (ironically the subject of an upcoming celebratory book from Abrams ComicArt, Bazooka Joe and His Gang: A 60th Anniversary Collection). For many years the gags were written by Underground comics legend Jay Lynch and drawn by former Tijuana Bible cartoonist Wesley Morse. According to The New York Times, the gum company executives have decided to rebrand, reducing the iconic character to the role of occasional spokesperson/mascot, stating, "What we're trying to do with the relaunch is to make the brand relevant again to today's kids." And here I thought all along that bubblegum alone would do that.

SADDLING UP FOR ANOTHER HEMISPHERE Stan Lynde, the 81-year-old creator of the Western comic strips Rick O’Shay and Latigo, is leaving Montana, where he grew up and spent most of his life, for Ecuador. He and his wife, Lynda, have divided and donated all of the memorabilia associated with their past life between their children and the Montana Historical Society and plan to pack what’s left into four suitcases, two backpacks, and a camera bag and move to Ecuador. Starting in 1958 as a spoof of “Hollywood westerns,” Rick O’Shay eventually achieved a circulation of about 100 papers and became increasingly a realistic portrayal of life in the Old West. After a 1977 contract dispute ended Lynde’s involvement in his first-born, Lynde launched a new realistic strip, Latigo in 1979 with Field Syndicate; it ran until 1983. He also wrote a Western comic strip Rovar Bob and other comics for Swedish publications. In the years since Latigo ceased, Lynde’s deep engagement in America’s Old West inspired him to produce eight novels staring Merlin Fanshaw about the period. They, like his comic strips, smack of the West in both incident and lingo. The Lyndes plan to return to Montana every fall for a few months. We’ll have a long piece about Lynde and his comic strip creations in the next Hindsight, to be posted before the end of the month—a happy new year token.

WHO’D A-THOUGHT: SEXISM IN HOLLYWOOD From Lady Geek Girl at ladygeekgirl.wordpress.com: James Gunn, if you don’t know who he is, is the director who has been tapped to helm the upcoming Marvel Cinematic Universe movie, Guardians of the Galaxy, due in 2014. He is also the author of this post, “The 50 Superheroes You Most Want To Have Sex With.” There is nothing wrong with being attracted to a superhero character. There is nothing wrong with wanting to screw a superhero. (I would be lying if I said I wouldn’t sleep with Batwoman, for example.) But the way Gunn comments on the entries in his list makes him sound less like a respected director and more like an unwashed neckbeard who has never seen a woman outside of bad porn. Here’s a highlights reel of the commentary, care of tumblr’s othothegreat and buckycaps: The art he chose in general, especially for the female heroes, is really gross and terrible, but here are a few more sexist, misogynistic, sex-shaming gems: “for those men that love rude bitches, [emma frost] the white queen is the way” [on natasha romanoff, the highest debut] “considering she’s fucked half the guys in the marvel universe, that’s quite a feat” [on elektra] she’ll “give you a nice, ninja-trained blow job” [on black canary] “I used to think she was the hottest chick in the dcu, but then I remembered that she fucks green arrow” [on dazzler] “a friggin’ great vagina” [on kitty pryde] “I want to anally do her” [on choice of art for jade] “I picked the one with the big tits” [on batwoman] “i’m hoping for a dc-marvel crossover so that tony stark can turn her; she could also have sex with nightwing and still be a lesbian” This same article also includes such charmingly puerile humor as calling Gambit a “Cajun fruit” and sharing his vivid imaginings of “my balls slapping against Gambit’s” which, he immediately points out, “makes me sick to my stomach,” just so you don’t get the wrong idea. He goes on to make fun of Dr. Manhattan’s penis size, and then this: ”Many of the people who voted for the Flash were gay men. I have no idea why this is. But I do know if I was going to get fucked in the butt, I too would want it to be by someone who would get it over with quick.” And he STILL manages to treat the male characters with more respect in general than the female ones.

S. CLAY WILSON: SOME MORE OF THE STORY Smashed up and in a coma when found unconscious the night of November 1, 2008, famed iconoclastic buccaneer undergrounder S. Clay Wilson has disappeared from public view. He’s recuperating. Wilson’s live-in lover Lorraine Chamberlain writes: “I have been flirting with S. Clay Wilson for forty years, lived with him for ten, visited him in the hospital every day for a year, and brought him home to take care of ...” She continues at http://www.punkglobe.com/sclaywilsonarticle0610.html —(in italics):

WILSON WAS IN A COMA FOR THREE WEEKS until he was taken off the ventilator. They had removed it once before in the first week, but he failed this breathing test and had to be intubated again. He suffered from a bout of pneumonia after that, so it was frightening when the neurosurgeon told us he may not make it when they removed the machine again. Thankfully, he gradually opened his eyes and continued breathing on his own. ... We had no idea how severely impaired he was for many months after that day. Always an uncooperative personality, many times he told people to “get lost" when they came to visit. Some took it personally, some blamed it on me, and some let it roll off their backs to return another day for a more successful visit. He had bouts of outrage when he was in the rehab facility, trying to escape with all of his belongings crammed into the legs of a pair of sweats, like a duffel bag. He spent days ranting about vivid characters and scenarios not based in reality. It took me awhile to realize that many of these wild delusions were really "verbal drawings"—not hallucinations at all. He couldn't draw them, so he spoke them. It took several months before he could even write his name. I brought him a small sketch pad which he kept close by but left blank. One day I looked in it to discover his famous signature! It brought me to tears, offering hope for the first time about his ability to draw again some day. Soon after that we discovered a face he'd drawn on an easel in the dining room. A friend thought it looked like me. Two days later, I discovered four Checkered Demon faces on the same easel. I saved these little gems to show him later, thinking we would have a great laugh at their simplicity. ... Since returning home, he spends many days drawing, followed by days or sometimes weeks off. He has completed several remarkable pieces here at home, but said recently that he is weary of his characters. This worries me, of course, but I do not nag him. I try to keep him engaged in any way possible, exercising, walking, and visiting with his friends. We go to museums and galleries together, and once in awhile to a matinee. He loved “Avatar” and “Alice in Wonderland,” as well at “Crazy Heart.” ... Wilson is not a blank slate. In many ways, he makes more sensitive observations than he ever verbalized before his accident. He cannot problem solve, however, and can do very little for himself without help. His short term memory is shot, and he no longer talks very much since he now has aphasia. Sometimes it is hard for him to express himself, but since we are together most of the time, I can usually help "put words in his mouth" so he can get it out. (He's always quick to tell me if I'm getting it wrong, however.)

THE PUNKGLOBE.COM site from which I’ve just quoted the foregoing paragraphs has some photos and brims with Chamberlain’s affection and regard. She outlines other aspects of this tragedy at sclaywilsontrust.com (in italics): S. Clay Wilson was [not coming home from a bar; he was] trying to get home from a friend’s house November 1, 2008, the night his life changed forever. We will never be certain if he fell or was attacked, since he has no memory of it. The numerous injuries on his face and head made him look like he was beat up. Two good samaritans found him unconscious between parked cars, face down in the rain, and called an ambulance. (I have tried to find them in order to express my gratitude for saving his life, but have had no success.) He’d suffered a Traumatic Brain Injury, bleeding in three hemispheres of his brain. He spent three weeks in a coma, and we had no idea how severely impaired he was for many months. Once he began to speak again we realized he hadn’t just “awakened” to resume life as it had been before. We’d been flirting since we met in 1968. I have been living with him since June 2000, visited him every day for the year he was in the hospital, and brought him home November 10, 2009. Taking care of him 24 hours a day is a daunting task, but one I am devoted to. He cannot go out on his own or he would get lost immediately, nor can he be left alone in the house. He cannot problem-solve, nor do anything for himself. Yet somehow he is aware of this loss of freedom, and some days I can tell it saddens him. The days he spent drawing were his happiest, but after the first year at home, he stopped doing it. He did about 15 drawings the first summer he was home, but by the next Christmas he would no longer go in his studio. Yet he thinks about drawing all the time, and frequently brings piles of his art supplies onto the bed. I continue to hope this means one day he will resume drawing. ... He is very quiet now after being a motor mouth all his life. But he is not a blank slate. ... He is more sensitive now, and needs reassurance every day. He’s always asking if I still love him, and reaches for my hand when we’re walking or watching a movie. I have put together a Special Needs Trust for him since he is no longer capable of earning a living. He will need 24-hour care from now on since the little details of daily life are a mystery to him now, and he is easily confused. This gifted artist worked as hard as he partied and was a playful, brilliant person. Although he is still capable of worrying about the future, he does not fully understand what has happened to alter it. He is now in need of help. This is a tragic turn of events for a proud man. The Trust is set up so it can only be spent on him. We pool our meager resources for basic expenses. I hope people will find a way to donate what they can to give him a better quality of life and assist in his ongoing care. Donations can be made here [i.e., sclaywilsontrustfund.com] by clicking on the yellow PayPal button. Or mail to PO Box 14854 San Francisco CA 94114 Look for his Facebook page at S. Clay Wilson. Thank you! Lorraine Chamberlain

RCH again: In case you’ve forgotten the products of Wilson’s twisted but highly comedic imagination—the Checkered Demon, the loathesome pirates, the rapacious wimmin—here is an assortment taken from The Art of S. Clay Wilson (172 9x12-inch pages, color and b/w; Ten Speed Press hardcover, $35).

While such specimens as these are probably review enough for this tome, I can add that there is no text in the body of the book itself, but it is generously prefaced by persons who know (and even understand) the noxious humors of the underground’s most outrageous cartooner: R. Crumb, Mark Pascale (Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, whose essay was written “as a defense for an acquisition” of Wilson art), John Francis Putnam (writing in The Realist), Charlie Plymell (Wilson’s first publisher), and Bob Levin (whose astuteness is legendary around Rancid Raves). Crumb writes of his first meeting with Wilson, which took place just as his Zap Comix no.1 was being printed by Plymell. Wilson, erupting with “inspired patter,” showed him a portfolio of his drawings. Says Crumb: “It looked like folk art, like old-time tattoos, like some demented highschool hotrodder’s notebook drawings. The drawings were rough, crazy, lurid, coarse, deeply American, a taint of white-trash degeneracy. Every inch of space was packed solid with action and crazy details. The content was something like I’d never seen before, anywhere, the level of mayhem, violence, dismemberment, naked women, loose body parts, huge, obscene sex organs, a nightmare vision of hell-on-earth never so graphically illustrated before in the history of art! Wilson was the strongest, most original artist of my generation that I had yet met. ... He’d been through art school and was barely touched by it.” Putnam writes about Wilson’s “single page explosions of mayhem, with people stabbing switchblades into eyeballs, people sticking shotguns into vaginas and pulling the trigger. Everywhere, bits of flesh and bone flying about as those who are involved in the melee make with exhortations like ‘Take that, you black-hearted cunt!’ ... Wilson has an American passion for accurate detail: a pirate pistol blowing off the top of a girl’s head has the correct fire lock. ... The focal point of Wilson’s fantasy is, quite simply, revenge. And who doesn’t dig revenge fantasies? ...With him, every fuck is a Grudge Fuck! ... Cocks are wonderfully distended and throbbing; cunts are prehensile and ever-receptive. ... The Dyke, in Wilson’s drawings, strides pridefully through all the mayhem. The Dykes actually win!” Charlie Plymell supposes about Wilson’s work that “a better label than Grotesque is the Carnival.” Bob Levin talks about Wilson’s art “of ball-bat outrage and white shark excess, chain saw intelligence and rattlesnake wit. ... He has (imaginatively) scaled the peaks and plumbed the depths and balanced on the edge, and he has emerged bearing guffaws. ... I don’t know about you, but I am even going to have trouble taking penises and vaginas so seriously again.” Speaking for myself (nothing remarkable about that, I realize), I am eternally grateful to Wilson for inspiring such flights of linguistic excess as those I’ve just quoted. And his pictures? Well, we all love to be grossed out from time to time. I would not part with this 2006 retrospective of his work from 1961 to 2006 for any amount of money.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Quotes and Mots The cartoonist makes love to his reader a meager minute or two each day; for the remainder of the twenty-four hours that elfin darling who paid for the copy of the newspaper is gamboling about among the other strips in the same or similar sections. Because of the brevity of assignation, the comic artist tries to fashion a thin, taut wire of continuity upon which he hangs baubles of incident, hoping to hold the customer’s affection even while his worship cavorts below the fold with the blowzy product of a rival syndicate.—Milton Caniff

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted NOW THAT THE ELECTION is over and the Major Issues of Our Times have been resolved, we’ve descended back into the Dark Pit of Politics As Usual—which means, news media exaggeration and its accustomed frenzy of preoccupation with petty peccadilloes and molehills. And here,

briefly, is an overview of the last month or so. Going clockwise, we start with Mike Luckovich at the upper left. His visual metaphor isn’t particularly striking, but a fat Tea Bagger leaving home in a juvenile fit of pique is wonderfully apt and echoes my view succinctly. “Quick, change the locks” indeed. This one runs a perfect parallel to Pat Bagley’s two-panel comment last fall (Opus 301) on the political climate in the aftermath of each Debate, wherein he depicts the Democrats as assuming blame for the failure of their man (“Obama blew it”), but Republicons never taking responsibility but blaming everyone else when their man fails (“it’s the moderator’s fault,” “it was rigged,” and so on). Joe Heller provides a nifty metaphor for the troubles afflicting David Petraeus and his be-ribboned ilk: simple silhouettes tell the tale. Next on the clock is Pat Bagley with a telling visual that puts the Benghazi episode in proper context. The Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm persists in making a huge deal out of the death of four Americans who were serving their country in a powder-keg of a foreign country. Yes, we are diminished by their deaths, each one of them. But presumably they all knew the risks. Meanwhile, we are also the poorer for the 7,000 who died in the deserts and mountains of Iraq and Afghanistan for reasons that now seem petty and obscure. Incidentally, by way of putting these honorable deaths in a context: in World War II, on the average, 6,600 American soldiers died every month; that’s about 220 a day. And now the GOP wants us to rend our garments and tear our hair over four deaths—all for the political advancement of the Party of Tease, of course. About the looming Fiscal Cliff, John Darkow has an image that works for me and anyone else who’s ever watched big horn sheep fight: they just butt heads over and over again until they’re both worn out. Big horny bastards engaged in head-butting to prove their machismo. The perfect metaphor. That our National Life is threatened as we teeter on the brink of the Fiscal Cliff reminded a friend of mine of one of the best bon mots to emerge from tv’s “Smothers Brothers” when Tommy Smothers says: “Let’s all get behind the President and Congress —and shove.” Our

next visual aid is not, strictly speaking, an array of political cartoons, but

gag cartoonists often supply startling insights into the way we live. The Humor Times ran a short piece by S.L. Chandler on Schwadron, who admits that cartooning as a profession has “lots of low points,” explaining: “Cartooning is filled with rejection. For every cartoon sold, there are hundreds that are submitted and rejected in the freelance field.” But he still enjoys the work: “Coming up with ideas is sometimes difficult,” he admits, “but the drawing—putting ink on paper—is a joy.” Despite the rejection, Schwadron advises young aspiring cartoonists “to follow their hearts and hope for the best.” Which Schwadron does with his 9 to 5, syndicated by Chicago Tribune Media Services, and in countless single panel cartoons that have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Readers Digest and other outlets, and in the illustrations for numerous books (including 25 different Chicken Soup for the Soul tomes). “As for the graphic novel,” Chandler goes on, “which permeates much conversation about cartooning these days, Schwadron says he doesn’t think he ‘could do graphic novels. I have a short attention span. Doing individual cartoons is more up my alley.’” Schwadron has a moustache and a beagle. You can find more of his work at schwadroncartoons.com.

COMINGS AND GOINGS. Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com reports that Dana Summers, editorial cartoonist for the Orlando Sentinel, announced on Facebook that he had just been laid off from the paper due to cutbacks. Jim Romenesko at his blog reports that several Sentinel employees, including Dana, took a buyout. Dana mentions that he’ll continue to syndicate editorial cartoons through his syndicate and focus on his two comic strips Bound and Gagged and the Middletons. Jeff Parker, editoonist for Florida Today, posted the following comment from Summers: "Well, earlier today, my 30 years at the Sentinel ended due to cutbacks. It was a good run—longer than many more-talented cartoonists I know. When I was a kid, all I ever wanted to do was draw cartoons and get paid for it. The Sentinel afforded me the opportunity to do just that. So, after thousands of drawings, I won't be signing the Orlando Sentinel after my name. I'm still drawing for TMS—editorial cartoons and the two strips. Except I'll be doing it in cutoffs and a T-shirt. No shoes. Thanks to all who read my cartoons in the paper." We reported earlier that the number of full-time staff editoonists stood at 54 following the departure of Jack Ohman from the Portland Oregonian; but Ohman then joined the staff of the Sacramento Bee, so the number reverted to 55. But with Summers’ departure, we’re back at 54. The Sacramento Bee pursued Ohman. He will take the perch left vacant when Rex Babin died last year. As it happens, Ohman and Babin were good friends. And Ohman was thinking about leaving the Oregonian. (Maybe because he heard buyouts were going to be offered; and he might not have had much choice later on. Dunno for sure.) In any event, the Bee’s editorial page editor, Stuart Leavenworth, was actively looking for a new staff editoonist. Rob Tornoe, reporting in Editor & Publisher (December 2012), wrote: “For Leavenworth, the role of the editorial cartoonist is more essential now to newspapers than it ever has been, and he knew that even though he would never be able to replace Babin, it was important to preserve the power and irreverence of his voice in the community.” Tornoe quote Leavenworth: “Rex had a really strong commitment to doing local cartoons, and since he passed away it’s been such a huge loss for our pages. ... Readers not only miss Rex, they miss a local cartoonist. It’s going to send a big jolt of energy to our readers when Jack starts in January.”

Persiflage and Furbelows: Why? Why do supermarkets make the sick walk all the walk to the back of the store to get their prescriptions while healthy people can buy cigarettes at the front? Why do banks leave vault doors open during the day and then chain the pens to the counters? Ever wonder—: Why the sun lightens our hair but darkens our skin? Why ‘abbreviated’ is such a long word? Why is lemon juice made with artificial flavoring, and dishwashing liquid made with real lemons? Why is the man who invests all your money called a broker? Why do they sterilize the needle for lethal injections? Why there isn’t mouse-flavored cat food? If flying is so safe, why do they call the airport the terminal? Why you never see the headline “Psychic Wins Lottery”?

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution WARREN BUFFETT, THE NATION’S WALL STREET ICON, went on a newspaper spending spree this year, reported the New York Times. “He bought more than 60 newspapers from Media General and a small stake in the newspaper company Lee Enterprises, a chain of mostly small dailies based in Iowa. At the time, he stressed that he had great confidence that newspapers would continue to be solid investments for decades to come: ‘I think newspapers in print form, in most of the cities and towns where they are present, will be here in 10 and 20 years,’ Buffett said. ‘I think newspapers do a good job of serving a community where there is a lot of community interest.’ Buffett has purchased 63 papers and a 3% stake in Lee Enterprises. Buffett being the economic bell wether that he is, we must all, now, take heart.

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE “The Democrats’ big advantage is that they have non-solipsists at the top of their party. The Democrats have a leadership class of Clintons and Obamas who are bgetter at reaching beyond the epistemic closure of their own tribe than anybody in the GOP.”—David Brooks “The modern purifiers start to resemble the Puritans of yore. Thomas Macaulay wrote 150 years ago that ‘the Puritan hated bear-baiting not because it gave pain to the bear but because it gave pleasure to the spectators.’ Similarly, our purifiers go after outdoor smoking, not because it’s a serious menace to public health but because someone is drawing some solace from tobacco. I have an even darker theory to explain the vigor of this crusade. Many political revolutions started in smoke-filled coffee houses. Just as soon as the authorities finish banishing the smoke, they’ll start going after coffee so they can stay in power.”—Ed Quillen, the late Denver Post columnist

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words CARTOONISTS GET ACCUSED all the time of perpetuating stereotypical images. Naturally. Of course. They’re the bread-and-butter of the craft. Stereotypical images are the visual shorthand for conveying a message. Elephants, donkeys, Santa Claus, half-naked wimmin—all stereotypes. Still, some of the Perpetually Concerned wring their hands about all these stereotypes. I occasionally do that, too. How can we do any original thinking when we think, always, in stereotypes? But,

like it or not, our society is awash in stereotypical imagery. We see it

everywhere, not just in comics. Take the picture below, which appeared to

illustrate

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. While I'm waxing philosophical, let us consider that the religion of America is America. It even has a holy trinity: the father of the country, George Washington; the savior of the country, Abraham Lincoln; and the "holy spirit"—namely, the Constitution, which Quixotically embodies the notion that it's possible to have a democracy in a capitalistic society.

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets

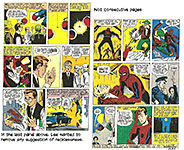

Marvel Comics: The Untold Story By Sean Howe 488 6x9-inch pages, no pictures; Harper hardcover, $26.99 A HISTORY THIS IS NOT. It is anecdotal rather than documentary. At best, it is a book of gossip; at worst, it is inaccurate. All history is gossip so we can scarcely fault Howe for spreading lots of it in this book. But recognizing the book as more gossip than ascertainable fact is a good way to prepare for reading it. Despite this debatable shortcoming, The Untold Story has been receiving favorable reviews hither and yon, mostly because (a) Marvel is big in the entertainment biz; no longer merely a simple publisher of funnybooks, (b) many of those doing the reviews don’t know much about Marvel so this tome seems gloriously juicy with insight, and © everyone dotes on gossip, the nastier the better. Howe is not particularly nasty although he does manage to make Marvel into a sort of simmering stew of fights, feuds, squabbles, power plays and bad feelings fostered by a boss, Stan Lee, who appears increasingly more concerned with promoting himself rather than Marvel Comics. Several times (enough to be monotonous), Howe records the departure of a Marvel staffer by saying: “His feelings about Marvel would never fully recover.” Or words to that effect. Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Roy Thomas—in short, anyone important to the creative processes of making comic books eventually leaves with a bad taste in his/her mouth. Lee is not a bad man in Howe’s estimation; but he seems oblivious to the effect on artists and writers of his decisions that advance the fortunes of Lee (and, to be fair, also of Marvel) at the expense of creative enterprise. Much of the narrative is a litany of people who were so slighted or put upon by Lee or by corporate preoccupations that they quit the company, leaving behind a crushed and bleeding spor of shattered dreams and broken promises. In some ways, Howe shows, Lee was as much a victim as any of his cohorts. When Marvel began to be noticed for producing comic books about unusual superheroes, longjohn legions “with problems,” Lee, as the editor of the line, would be interviewed by newspaper reporters and very often his enthusiasms led his interviewer to believe that Lee was the sole creative personality at Marvel. This is an old story. Kirby created the Silver Surfer, Howe says; but Lee has always referred to the character as his creation, not Kirby’s. Ditto with Spider-Man and Ditko. Only in the last 15-20 years has Lee pointedly acknowledged that the creative machinations at Marvel included artists at his elbow. Incidentally, on my recent weekend sojourn in Washington, D.C. for the convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, I spent a couple of hours in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress, looking at original art for the first Spider-Man story, which was donated by “an anonymous” person. Ditko?

Interlude with Spider-Man. Judging from the evidence at hand, Ditko submitted his work to Lee in its penciled state. In this inaugural two-part Spider-Man tale, Lee asked for three adjustments, two of which would have required re-drawing a panel or whiting-out offending visual elements. But the original art for the pages I contemplated featured no paste-overs and no white-out, which would have been visible if the adjustments had been made after the art had been inked. So Lee was looking at the penciled pages, which Ditko adjusted according to Lee’s directions when he inked. Or, as it happens, did not adjust. Lee

made his suggestions in pencil in the margins. The notes have been erased but

they are still discernable. The first one occurs on page 3 of Part One. The

eighth panel shows a speeding automobile that almost runs over Peter Parker

because he is so absorbed in thought that he is oblivious to his surroundings.

The penciled art apparently included an arm protruding from the interior of the

car, and that, Lee thought, implied that the car was being drive recklessly, so

he asked Ditko to remove the arm so as not to suggest to young impressionable

readers that reckless driving was acceptable. And Ditko removed the arm, as we

see in the accompanying illustration. On the last page of Part Two (shown above), Lee’s comment focuses on the sixth panel. Here, he asks that Ditko “lift up” the second policeman’s head. In the original, apparently the second cop’s head is lower down in the panel—or perhaps just smaller. “Lifting it up” enhances its visibility, and Ditko complied with the suggestion. But

the other comment Lee made, his third instruction, Ditko ignored. On page eight

of Part Two, Lee’s penciled comment is next to the third panel: “Steve, omit

crook! Show door slamming!” Ditko quite sensibly ignored this command. Ditko may also have realized that the crook’s face, which establishes his identity at the end of the story (look again at the previous visual aid), needs a little more exposure than even the close-up of the next panel supplies. The figures of the crook in both second and third panels are small, but the heavy eyebrows provide a quick and certain means of identifying him. The profile in the fourth panel confirms in detail the distinctive eyebrows, but profiles, as a general rule, are not useful in identifying anyone except in profile; and the crook at the end does not appear in profile. Without page eight’s several exposures of the crook’s face, including the detailed profile, we might not be equipped to share Spider-Man’s moment of recognition at the end, and the story with its heart-rending moral lesson would be substantially spoiled. Ditko was right to ignore Lee’s dictum here. Judging solely from this instance—perhaps the only “documentary evidence” we have—Lee, as editor and scripter, influenced how Ditko told the story that Lee plotted, but Ditko did the actual storytelling, enhancing its emotional highs and lows, and he didn’t always do what Lee wanted him to do. Ditko is clearly the better storyteller; Lee’s advice is either off the mark or almost superfluous.

Back to Howe’s Book. The relationship between plotter/writer and artist, between Lee and Ditko—and that between Lee and Jack Kirby—epitomizes the “Marvel Method” of creating comic books. Lee conjured up a plot and outlined it to an artist, and the artist then drew the story and then passed the finished pages of visual storytelling, first in pencil then in ink, back to Lee, who then created speeches and captions that knitted the pieces together. (Although sometimes, as gossip has it, Lee couldn’t remember the plot when confronted by the pages it inspired. He made do, though—larding the tale with witticisms and quips, thereby, almost incidently, creating the Marvel mystique.) The “Method” served the purpose for which it was devised: by sharing the storytelling load, Lee was able to produce great quantities of comic book stories that he could not have created had he tried to write complete scripts for the artists, the practice followed by DC and most other comic book publishers in the early days. But the “Method” also fostered the notion that Lee was the creative engine at Marvel; artists were secondary. The actuality, however, was quite the reverse. And the artists resented it. The unhappiness fostered by the “Marvel Method” of creating comic books—and the bickering struggle over possession of original art and all the rest of the more sordid sensational aspects of Marvel’s history—have been aired before in a 2004 biography of Jack Kirby written by a man going by the name of Ronin Ro, which, as I recall, is a pseudonym. His Tales to Astonish, rift with scandalous revelation, has a good deal in common with Howe’s book: both rely upon interviews with persons who were engaged in producing Marvel Comics; both dwell upon the discontent of these persons and the injustices they complain of. Mark Evanier, who worked on projects with Kirby in the latter part of the artist’s career, was among those “Ro” interviewed, and Evanier said he was surprised at how short the interview was. “If I’d been him and I had a chance to ask me questions,” Evanier reported in his newsfromme.com in September 2004, “I’d have asked a lot more than he did. ... As I page through the finished volume, I find myself impressed by his knowing a couple of things that I know I didn’t tell him—but also annoyed about a number of things that I could have corrected if he’d run them by me.” After reading the book, Evanier decided he didn’t want to review it. He felt Ro “made a sincere effort ... and did a better job than I’d have imagined from a guy who was so far removed from Jack.” But Evanier didn’t want to “endorse everything in the book” because there were inaccuracies; nor did he want to go through the volume, page by page, to point out the errors. He finally decided to say, simply, that he had mixed feelings about the book and to caution against believing everything in it. Interviews with Jim Steranko provide one of the more enthralling episodes in Ro’s book. In the struggle over possession of original art, Steranko got his pages back by simply taking them. They were among piles of original art on shelves where they’d been stowed after being returned from the printer. No security. And unauthorized persons were taking them and selling them at conventions. Steranko confronted Lee and said: “Unless I get my pages back, I’m gonna go to the IRS and tell them about the original art inventory.” By then, Steranko reasoned, the inventory had to be massive, going back to Timely and Atlas, and “worth a fortune” even at only a few bucks a page. When Steranko told Lee that if IRS found out about the inventory, Marvel would have to pay taxes on it, Lee told him to “do whatever you have to do—but I never want to discuss this again, ever.” Steranko took his pages. “And when Stan saw I had my originals for display at conventions and shows and exhibitions sometime later, he never mentioned it,” Steranko said, “and I never mentioned it again either.” Ro, like Howe, sometimes quotes his sources directly and sometimes simply constructs a narrative from what they’ve told him. His story dashes on, headlong, usually without the specific underpinning of the sources of its presumed facts. No footnotes. No bibliography at the end. None of the apparatus you’d expect to find in an authentic history. And that makes it questionable. In sharp contrast to Ro is the biography of Stan Lee written by Jordan Raphael and Tom Spurgeon, Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, which appeared the year before Ro’s Kirby book. Spurgael (or Rapheon), to bundle the pair, includes an extensive bibliography, arranged by chapter (almost like footnoting), which attests to the seriousness of their endeavor and the likelihood of its historical accuracy. The authors shore up their narrative with analysis and opinion, as do Ro and Howe, but Spurgael does not expend as much of this effort on fanning the flames of sensation. They conscientiously looked for truth among the gossip and rumors. Their book seems factual and therefore a good history. Howe, on the other hand, seems to leave history to Spurgael. His narrative, liberally laced with gossip and the dubious testimony of disaffected writers, tumbles along, aiming for the Big Finish when the company is rescued by blockbuster movies based upon Marvel characters. In effect, Howe’s book, after the obligatory review of juicy discontent created by Lee, takes up the Marvel epic where Spurgael and Ro left it and advances the narrative to Hollywood. We can see substantive differences in the emphases inherent in the books’ page counts. Spurgael is a shorter book—about 300 pages, 80 of which are devoted to Lee and Goodman and comics history from the 1930s to 1960; 26%. Howe’s longer treatise, almost 500 pages, devotes only 25 pages to whatever happened before 1960; 5%. (In reporting the 1992 death of Martin Goodman, Howe comes close to attributing to “the founder of Marvel” the creation of the entire comic book industry; but he slights the man’s contribution by gliding so quickly over Goodman’s early history.) Howe does, however, footnote exhaustively, impressively, and he lists all those he interviewed between 2008 and 2012 (something like 150 persons). Still, the accuracy of Howe’s reportage is suspect. On page 12, he commits a blunder that makes me wonder how thoroughly he looked into his subject: “Legend claimed that the publisher of Wonder Man, one of the earliest and most blatant imitations [of Superman], had been an accountant for the head of National [Superman’s publisher] until he saw the numbers on Action Comics and [so] quickly set up his own company” to cash in on the phenomenon. Legend? What part of that scrap of history is legend rather than fact? That Victor Fox, an accountant at National, left the company (now DC) to form his own company when he saw sales figures that convinced him that comic book publishing was the coming thing? I believe that whatever Howe thinks is legendary in that sentence is actually pretty well accepted as fact. But if he didn’t research the matter enough that he’s driven to saying it’s legend, then I wonder what else he didn’t research enough. On the next page, Howe says the appearance of the Submariner pages in Marvel Comics No.1 was “compromised by cheap printing, which muddled everything into a purple sludge.” Yes, the artwork looked smudgy, but that was caused by artist Bill Everett using Craftint paper for shading, the slanting and cross-hatched lines filling up so much of the art with gray tones that the addition of color could only muddy the appearance. Cheap printing it was, but the appearance of the artwork was compromised by the artist’s choice of medium, not the printing press. Two slips in as many pages persuaded me that I could skim this book rather than read it closely. But I am as intrigued by gossip as much as the next guy, so as I paged through the book, pausing here and there, I started paying closer attention until, by the end, I was reading every word. Long before then, however, I’d happened upon another couple of Howe missteps. On page 32, he mentions the blunder Martin Goodman made in 1957 when, suddenly stuck without a distributor, he signed on with the only show in town, Independent News, which was owned by DC Comics. Independent News struck a hard bargain to protect the company that owned it from a competitor: Goodman, who had been cranking out titles by the dozens (reputedly as many as 80 a month at one point), would be restricted to no more than eight titles a month. “The Timely line,” as Howe puts it, “was decimated instantly.” In fact, Timely was rescued by Stan Lee’s consummate skill as a production manager. First, he gradually reduced the frequency of Timely titles to bimonthly, which permitted the company to produce as many as sixteen titles, not just eight. Then as Goodman began demanding the addition of superheroes to the line, Lee juggled to avoid going over sixteen—cancelling titles, adding features within existing titles, renaming books. This feat Spurgael discusses in some detail, but Howe never mentions it. Similarly, Howe slights Roy Thomas, who joined the Marvel staff after the Independent News deal went away. By then, Marvel was adding titles as fast as exploiting the market demanded. And one of the things that contributed to Marvel’s success in the 1970s was the introduction of comic books about the Robert E. Howard character, Conan, who was bought into Marvel by Thomas. Conan was a big hit, Howe says, but says no more about it or about how Thomas negotiated the licensing deal, which eventually led to other licensing deals. Nor does Howe mention Barry Windsor-Smith, whose growth as a visual stylist while helping Thomas adapt Conan to comic book format assured its success. Howe’s sourcing is impressive, but however scholarly the apparatus, he is relying largely upon the testimony of writers and other factotums at Marvel, and very little on artists. On the one hand, this practice is fruitful: writers, in particular, are articulate about their experiences and their views of what was transpiring at the “House of Ideas.” On the other hand, writers, particularly those who create works of fiction, are, by nature, tempted to make things up—or to emphasize selected instances for dramatic effect. In short, since writers make their living by fabricating the best tales they can, isn’t it likely that they’ll deploy their talent during interviews about their, and Stan Lee’s, past? How reliable are they as sources? Jim Shooter, whose persona in Howe’s book emerges largely from the testimony of the writers he bullied, comes off as a ranting tyrant, demanding substantial changes in books on the day before they are scheduled to go to press. Jim Starlin and Steve Englehart partied all day and dropped acid before plotting their books. How reliable is their testimony? Still, Howe has cobbled up an engaging narrative. He may not have interviewed many of the artists, but he is astute enough as a reader of comics that he can assess the art and articulate his appreciation of it, thereby filling out portions of his narrative. He alternates plot summaries about the comic book adventures with gossip about writers, artists and editors. Anticipating the Hollywood crescendo that ends his tale, Howe threads throughout the book Stan Lee’s longing for the career of a Tinsel Town mogul. Howe’s method produces a highly readable (however dubious factually) book. In the last analysis, Howe’s method is no different than any historian’s. He is forced to rely upon questionable witnesses. As are we all. So is all history but the sum and substance of gossip? Probably. And we are therefore well advised to remember that. In his handling of the desertion of Todd McFarlane and Jim Lee and others to form Image Comics, Howe apparently doesn’t realize that the name of the new publishing company was intended to proclaim the victory of artists over writers in a dispute about which was the most important in producing comic books. Image Comics were concocted by the artists, who worked up plots and stories without any assistance from writers, making them “poster boys for artistic autonomy”—and setting Comics Journal editor Gary Groth off on one of his celebrated tirades (which Howe quotes): “The founding creators have managed to dumb down and vulgarize an idiom not known for its application of intelligence or sensitivity and have consistently displayed an arrogant contempt for the medium and an unbridled ignorance of its history, coupled with a moral obtuseness rivaled only by the corporations to whom they owe their success.” McFarlane’s scorn for comic books and costumed heroes and the industry that grew up around them is dutifully presented. Since he was the ostensible leader of the Image revolt and embodied the attitudes upon which it was based, it’s no wonder that most of the Image founders we don’t see around much anymore: almost as if to reinforce an image (ha!) of artists as infantile conductors of temper tantrums and otherwise too childlike to sustain an adult enterprise, most of the founders have disappeared into other endeavors. The Image Comics now on the newsstands are being produced by a second or third generation of artists; the first bunch, McFarlane’s crew, have long receded from view. Except Erik Larsen, whose Savage Dragon continues, unabated. Larsen obviously loves making comics. And the comics he produces are exciting and readable. Perhaps not as intellectually challenging as Groth might wish, but superheroes were not conceived as anything but devices for exciting visual storytelling, and Larsen does that with elan and panache. I enjoy his work chiefly for the visual energy it embodies. Savage Dragon is virtually a model for superheroicism in comics. What more can we ask? The creation of Image Comics, while a momentary sensation, soon contributed to the temporary collapse of the direct sale business: the jubilant outlaw artists weren’t production-minded enough to publish their books on schedule, and comics shops that ordered the books (and, as required, paid for them in advance) soon exhausted their financial resources and began closing. Eventually, the direct market recovered; by then, the original Image guys had moved on. Building up to his big screen conclusion, Howe details Marvel’s insane appeal to the so-called “collector market” (which turns out to be not as large as everyone imagines) and the company’s equally nutty devotion to marketing tricks (cover enhancements, anniversary issues and other gimmicks) that were detrimental to the future of the company and of the medium itself. Anticipating fan interest, comic book stores bought huge inventories of such confections and were then stuck with them when the fans weren’t quite as interested as the marketing department at Marvel thought they’d be. The Marvel marketeers were killing off the stores that were feeding Marvel. Stores were closing and “actual comics readers ... were fed up with paying jacked-up prices for hologram covers” and left. But the disaster brought on by greed would be spectacularly quelled by Hollywood blockbusters. In the last 100 pages of his book, Howe conducts a masterful review of Marvel’s years in the hands of a succession of Wall Street raiders who bought and sold the company—Ron Perelman, Ike Perlmutter, Avi Arad, names that ring the doomsday bell. They wanted a company they could sell for a fortune. But not being comics people, they believed the long-standing Stan Lee hype that Marvel characters were as ubiquitous in popular culture as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. But Marvel was not Disney (not until just recently anyhow). In an effort to monopolize the marketplace, Marvel inaugurated the distribution wars—buying a distribution company and constructing a diabolical distribution system that presumed that comics stores were so eager for Marvel books, so dependent upon them for financial success, that they would stop buying all other publishers’ comic books if a system could be devised that punished them enough for not buying Marvel books and rewarded them for buying them. The validity of this marketing gimmick soon collapsed of its own fiendishness. Meanwhile, “the number of comic shops, which had already fallen from 9,400 to 6,400 in just two years,” Howe notes, “soon dropped to 4,500.” Marvel, which was the best selling comic book publisher at the time, was financially a shambles, approaching bankruptcy. The Wall Streeters’ response: put all editorial decisions in the hands of marketing personnel. “Perlmutter saved money by sacking executives. ... The joke everyone muttered was that if Perlmutter had his way, Marvel would consist of one guy in an office with a phone, licensing the characters.” And on the West Coast, those characters were slowly mustered for making movies. Joe Simon, who was engaged in yet another fight to regain the Captain America copyright, “could see that it was movies, not publishing, where the future lay—comics, he said, were for the ‘masturbation generation,’ a parade of big guns and big breasts. ‘The business is going to hell in the first place,” Howe quotes him saying, “‘but the characters are more valuable than ever. So, we’ll do the best we can’” to gain control of what was once the biggest character of all. Avi Arad, busy putting together movie deals, assessed the situation: “Publishing was where it all started, and [comic books were] a great source. You had readymade storyboards to look at to understand how to lay out stories. But the big deal for the company was merchandising—everything from cereals to shirts to video games to shoes, you name it. That’s where the serious revenues were coming from.” “By 2004,” Howe says, in one of his sporadic citations of date, “Marvel was employing statistical analysts to feed information about creator and character performances into algorithms that determined launches, cancellations, and frequencies of publication. The company embraced the concept of crossovers as never before, with a relentless chain of big-event storylines that determined the course of multiple other titles. In turn, each of these massive arcs—which included prologues, epilogues, and entire spin-off series—fed into the one that followed. Major characters were torn in half, died in explosions, sacrificed themselves, lost their memories, regained their memories, lost their powers, or were revealed as shape-shifting Skrull aliens who’d posed as the real thing for years while the original hero was kidnaped on a spaceship.” In short, the company had deteriorated into a vast marketing scheme not comic book creation. But the successful movies began to stack up—Spider-Man sequels, X-Men sequels, and so on—predicting even greater success. “The strategy was to corner the market on films about the individual members of the Avengers: they’d get back the rights to Iron Man ... roll out “Captain America” and “Thor.” ... And then, for the coup de grace, they could build on brand familiarity with the Avengers and combine the franchises into a monster-sized team-up movie. ... The circle was closing. The interweaving intricacies of the Marvel Universe, in all their glory, would be replicated as synergistic Hollywood franchises.” It all culminates, exactly as planned, Howe says, on the first weekend of May 2012 when “‘The Avengers’” broke the record for the biggest box-office debut in movie history. A week later, it had grossed more than $1 billion worldwide.” Such success should, by all rights, blast its comic book incarnation to bits. But it hasn’t. Not yet. Marvel comic books continue to come out. Revitalized? I don’t know: I don’t buy that many Marvel titles. The few I buy seem pretty much the same old schtick, with an occasional new twist torqued in. DC, in contrast, seems always poised to try something new, something different. Howe is not convinced that the “Hollywood rescue” (as I call it) is good for Marvel. It performed a financial miracle of sorts, but the comic book universe it rescued has been modified and amplified and glorified out of its previous virtual reality by means of the endless tinkerings and alterations necessitated by the heroes’ appearance in other media, passing, en route, through the hands of a seemingly endless parade of temporary custodians. The comic books still come out, but they appear in the service of larger market considerations. They are commodities, not artistic creations. Howe’s “untold story” has actually been told before, as I mentioned, by Ro and Spurgael, among others. But the title leads the uninitiated among book reviewers to suppose that the book is full of “inside” information, tantalizing backstage stuff that the public, which seems panting for the next superhero movie, is hungry for. Maybe we are. I am famished enough that I’ve now read this whole book—even though I know much of it is gossip, like most histories that are fed by the prejudices of eye witnesses. I do wish, however, that it weren’t so difficult to find dates in Howe’s book. When he says, for instance, that “for the next three weeks” a disaster fomented, you have to flip back for pages to locate the month and year those crucial three weeks took place in. Still, Howe’s is an impressive performance. He demonstrates superior organizational skills in assembling a massive quantity of information and in arranging a cogent order for its presentation. And his tumbling narrative is highly readable, a pleasure to wade through—although splashing might be a better metaphor for the delights of the experience.

FOOTNIT: The Week magazine asked Sean Howe to participate in its weekly “Best Books” feature in which a chosen author lists his choices as the best books in his field. Taking Marvel Comics as his field, Howe listed these books: The Golden Age of Marvel Comics, Vols. 1 and 2; Masterworks Fantastic Four, Vols. 5 and 6; Daredevil, Vol. 2; Masterworks Spider-Man, Vol. 4; Masterworks Uncanny X-Men, Vols. 4 and 5; and Marvels, that painted extravaganza by Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross.

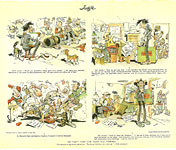

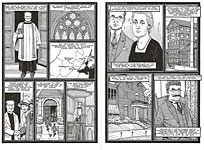

Comics about Cartoonists: Stories About the World’s Oddest Profession Edited and designed by Craig Yoe 232 8.5x11-inch pages, color; IDW Yoe Book hardcover, $39.99 THIS TOME IS ANOTHER in what is becoming a long shelf of delightful and superior Yoe Books, volumes distinguished by the obvious affection their editor/author, himself a cartoonist, has for the medium. That applies not only to the selection of content but to the design of the book that showcases the material. Take, f’instance, this volume’s endpapers. Why bother with endpapers? Who looks at endpapers? Craig Yoe (with whom I sometimes share a hotel room at the San Diego Comic-Con) evidently does. And he thinks others who admire cartooning and its history might also look at endpapers if those endpapers have something to do with cartooning. So the endpapers of this book display numerous of the ads that appeared during the first 70 years or so of the last century in sundry sorts of magazines, each ad offering training in cartooning via mail order courses. Dozens of the profession’s practitioners took correspondence courses in their youth—Milton Caniff, Elzie Segar, Jack Cole, Carl Barks, Chic Young, Bill Mauldin, Floyd Gottfredson and so on. And here we see the come-on ads that seduced young scribblers to part with their allowances: “How To Make Money with Simple Cartoons,” says one; another, “Cartoon Your Way to Popularity and Profit” (illustrated with a picture of a young cartoonist surrounded by pretty girls); “Do You Like to Draw?”; “Your Future Depends on You!” In the same spirit of informing and entertaining, the first seven pages of the book are devoted to spot drawings of cartoonists by the great Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman, the first big-foot cartoonist of any eminence in the profession. And, yes, he also ran a correspondence school. As you can tell from its title, the book is devoted to reprinting comic book stories about cartoonists—almost 40 stories, drawn by nearly three dozen cartoonists (some, H.T. Webster, Milt Gross and Winsor McCay, represented by more than one story). With few exceptions (like those just named, plus Elzie Segar and Al Capp), the cartoonists labored in our favorite four-color pulps rather than in newspapers. The content is punctuated by fifteen comic book covers depicting comic book characters working as cartoonists (Bugs Bunny, Wacky Duck, even Superman and Batman). The longest story in the book is by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon: their cartoonist is the protagonist in a love story from the romance title, In Love, but the tale also traces the guy’s progress from novice to full professional, supplying en route glimpses into the intricacies of syndicated comic strip cartooning. The shortest stories are one-pagers—Hey Look! by Harvey Kurtzman, a couple of Grossly Xaggerated by Milton Gross, and four of the eight or so one-page autobiographical comics Collier’s published in 1948 (Milton Caniff, Ham Fisher, Chester Gould, and Ernie Bushmiller). Some of the works represented are classics—a Spirit story by Will Eisner, a six-page Scribbly continuity by Sheldon Mayer, an adventure with Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel’s manic Funnyman and another with Basil Wolverton’s zany-off-the-wall Scoop Scuttle—all particular favorites of mine. And in an Inkie story, Jack Cole supplies his usual dose of wacky visuals coupled to routine insanities. One character threatens the cartoonist with a bottle of camel poison, saying: “We’ll poison all da camels, den dere’ll be no camel’s hair fer brushes an’ all da artists’ll starve.” “You fiend!” exclaims the cartoonist. “You have me in your power!” And there are some rarities like a cartoon done by Jack Chick before he took up salvation as a subject matter, “Kar Toon and His Copy Cat” by Martin Filchock, and a 1953 horror story by Jay Disbrow, who draws, here, better than I remember his doing. “Suzie,” attributed to Harry Sahle, is a spritely leggy-sexy funny romp with the title character modeling superheroine garb for a cartoonist. The collection ends with another classic, Wally Wood’s legendary “My World.” The reprinted pages are reproduced directly from their initial incarnation in the funnybooks, complete with out-of-register color sometimes (not often), but lacking altogether (thankfully) any recoloring with garish hues in a misguided attempt to refurbish the art to make it look “new.” On the first page of every item, Yoe supplies the source (comic book title, number, and date) and the name of the cartoonist—invaluable. Yoe’s Introduction, laced with some rare one-panel cartoons (many from his stupendous stash of originals), explains obscure references and reminds us of who some of the cartoonists are (Frank Frazetta worked for Al Capp on Li’l Abner for a time before catapulting himself into fantasy illustration). This is his favorite book, Yoe says; and it may be mine, too. We’ve posted a few pictures from the book hereabouts; you can get an even better idea of the content at the video posted at youtube.com/watch?v=IYqQGMcIIoU

Or watch it here...

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, this time, by way of giving you a Christmas shopping list to present to your spouse, starting with—:

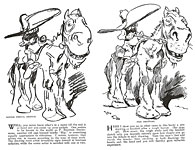

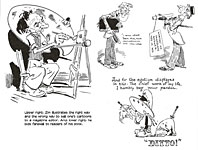

The Lost Art of Zim: Cartoons and Caricatures By Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman; edited by Joseph V. Procopio 128 5.5x8.5-inch pages, b/w text and pictures; paperback from Lost Art Books, an imprint of Picture This Press, $19.95 IF ZIM DIDN’T INVENT “BIGFOOT” CARTOONING in America, he was at least the foremost practitioner of the form during his career on the staff of the humor magazine Judge, roughly 1885 - 1910. He continued freelancing his cartoons and various writings until his death in 1935 at the age of 73, and he also conducted a correspondence course in cartooning and, in 1910, produced an instructional tome on the subject, which Joseph Procopio has now carefully reproduced in the book at hand, adding to its pages from an earlier (1905) Zim effort, This and That About Caricature. The book brims with sound, practical advice about drawing—some of it, like the caution against having lines overlap in a picture, not readily available elsewhere anymore. But Zim infiltrates the how-to’s with other valuable tidbits: “In the first place, try to forget that you are a great artist and lead a natural life. Don’t be too eccentric. Be like other poor mortals who love to earn an honest living, and the world will love you the better for it.” “When you make a character sketch, be sure to append an appropriate foot. ... It’s the proper treatment of details that earns big salaries.” Illustrated with an array of different footwear. “Perhaps the hardest simple object to draw correctly from memory is a silk plug hat [top hat]; it is so perfectly shaped that the slightest discrepancy in drawing it is perceptible. ... An open umbrella is also very difficult.” “Refrain from caricaturing acquaintances unless you are sure they are not of a sensitive nature, else you may incur their enmity. If they are sensitive or vain, they do not deserve the attention of your pencil or pen. You may ridicule, but don’t offend.” “Sage advice,” saith Procopio, “on a variety of esoteric subjects, including Swiping, Booze and Bohemianism, Dealing with Editors, and Cartoonists and Marriage. About Bohemianims, Zim cautions: “To follow this life in its true sense is all very well, but the average art student is quite apt to mix it up too freely with beverages of amber and more ruddy tints—a nerve-wrecking and career-destroying course.” And marriage: “In the face of the facts before me, it would be safe for me to state that a man, to be successful in any matter he undertakes, should be either married or unmarried.” “The main point in the profession is ‘The Lead Pencil.’ Whenever you sketch in public, in order to throw your audience off the track and make them think that you are a full-fledged caricaturist, always wear a reckless air and a common twenty-five cent necktie.” Apart from such wisdom as the foregoing, the book contains a wealth of Zim drawings—more than you’ll find anywhere else. And since Zim’s drawings constitute most of his appeal to me, I’ll conclude this short review with a smattering of pictures from the book—and then I’ve added some more from other sources, just to give you a comprehensive understanding of America’s most eminent bigfoot cartoonist of his day.

Fitnoot: Lost Art Books’ inventory includes several other notable works about artists or cartoonists, including: The Lost Art of Frederick Richardson (a newspaper artist in the 1890s whose illustrations for the Chicago Daily News were incredibly detailed), The Lost Art of E.T. Reed: Prehistoric Peeps (recording Reed’s discovery of a comic goldmine in anachronistically combining drawings of prehistoric men and dinosaurs with modern life), and two volumes of Heinrich Kley drawings. Dover did a couple volumes of Kley drawings many years ago, but these two Lost Art Books add many more to the store, including many in color. We expect to review all of these delectable publications in a not-too-distant opus. Forthcoming in 2013, it sez on the website, a tome that reprints all of Matt Baker’s delectable and thoroughly decent Canteen Kate, a coincidentally happy event that will juxtapose delightfully with the book we review next. Look for all of these at LostArtBooks.com, whence you can also order your own copies thereof. I did.

Matt Baker: The Art of Glamour Edited by Jim Amash and Eric Nolen-Weathington 192 8.5x11-inch pages, 96 in color; TwoMorrows hardcover, $39.95 MATT BAKER IS THE GOLDEN AGE artist everyone’s heard about but no one knows about: everyone knows that he was one of the few African Americans working in comics in the 1940s and 1950s and that he drew gorgeous women in a surpassing style, but no one knows much more. A long-awaited and expertly accomplished treatment of an admired but mysterious master comic book maker, this volume delves into both his artistry and his biography. Unconventionally, the book begins at once with Baker’s pin-up heroines: no preamble, no title page—nothing bookish or bibliographic—the first page reproduces the most famous Good Girl Art of all time, that cover rendering of Phantom Lady whose battle togs are designed to plunge from her clavicle to her navel in order to display her nearly naked chest. This titillating spectacle is followed by a Phantom Lady story, another of her covers, another story and cover, then a Sky Girl story (she wears conventional waitress garb, but her dress is always blowing up to reveal shapely legs). Then comes the text, amply illustrated with Baker drawings and photographs of a gorgeous black man (all obtained from Baker family members, who have carefully prohibited their reproduction elsewhere). Alberto Becattini supplies the basic biographical text, culled from sources scattered hither and yon, and amplified elsewhere in the volume by a 2004 Jim Amish interview with artist’s nephew, Matt D. Baker, and his half-brother, Fred Robinson, and interviews with Baker’s friends and co-workers, accompanied by numerous drawings, many previously unpublished. Becattini and Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. provide an annotated index of Baker’s professional work, arranged alphabetically by comic book title and amply illustrated with cover art and interior pages. The book includes several samples of the syndicated comic strip that Baker drew for a short time, Flamingo, about an exotic dancer (no, not a stripper) and concludes as unconventionally as it began, this time with a Canteen Kate reprint in color and two stories shot from original art—Kayo Kirby (manager of a female wrestler) and Tiger Girl. More than seductive, his pictures of girls revealed a sense of humor—with a turned ankle, or raised chin. Born in 1921 in North Carolina, Baker became a professional comic book artist at the tender age of 23—an extraordinary achievement for an African American in those days of aggressive segregation (and therewith, a ringing testimony to his talent early on). He joined the Iger Studio on the strength of a single sample of his art, Jerry Iger said—a color sketch of “naturally, a beautiful gal!”; his first published art appearing in Jumbo Comics No.69 (November 1944). Once established as a good girl art practitioner, Baker took assignments illustrating stories in pulp magazines, and in 1955, became art director of an early Playboy imitator, Nugget. Afflicted as a boy with rheumatic fever that weakened his heart, Baker died in 1959 of a heart attack—just a short 15 years into a career that might have been even more stunning than it was. This volume, with its insights and careful documentation, is a thorough treatment of one of the industry’s most remarkable artists. We’ve longed for it for a long time, and we recommend it highly, without reservation or quibble. Lots of pictures, ample demonstration of Baker’s mastery of his medium. A well-designed book that seems to spare no expense to capture and convey the essence of the artist. The color pages are shot from comic books and are not noticeably retouched or reconstructed: this is Baker’s work as we saw it when it first hit the newsstands. Here’s an ample sample of the Baker art that graces the production.