|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 297 (July 27, 2012). Approaching the end of Open Access Month here at Rancid Raves, we report (in order, down the scroll) on the horrors of the Batmovie midnight massacre and on the various joys and excesses of the recent San Diego Comic-Con (including lots of pictures and a couple reviews, of sorts), and we look at two new books about Superman and another anthology of Crime Does Not Pay. Until August 1, you can read it all—including the massive R&R Archives and all of Harv’s Hindsight—without having a $ubscription. Startomg August 1, we put up the $ubscriber’s Wall again, so to avoid running headlong into it, why not subscribe now— a measly $3.95/quarter. A trifle. A pittance. How can you go wrong at this price? And now, a generous sample of the sort of thing we do here, to wit—:

BATWEEK From the Laughably Ludicrous to Senselessly Savage BATMAN ACHIEVED greater visibility the week of July 16 than he usually enjoys. The week began with him on the cover of Entertainment Weekly: the Batcover treatment of the Christopher Nolan movie, due to debut the following weekend, was another in the seemingly endless EW affirmations of comics as social detritus with cultural significance—despite the magazine’s offhand treatment of funnybooks as the founding impulse of the San Diego Comic-Con, which, in another effusion of cultural approval, was given full-scale post-con reportage in the next issue of EW. The week before the Con, as we reported here in Opus 296, EW published a 25-page “preview” of the Comic-Con, but only two of those pages were devoted to comic books; for the rest, it was movies and tv. The post-con report was even more of a back-of-the-hand compliment: in a 15-page report (which included 8 pages of photographs of actors and actresses at an EW party in San Diego), comic books were mentioned only three times. Once at the beginning: “From July 12-15, more than 125,000 fans—so many in costume, it puts Hallowe’en to shame—descended on San Diego to attend the sold-out annual gathering, which began in 1970 as a weekend-long hangout for a few hundred comic book aficionados and has evolved into the single most important showcase for Hollywood’s biggest (and most expensive) projects.” Twice at the end in a report by “Firefly” star Nathan Fillion, who admits he did some autographing of Marvel comics but then goes on: “Comic-Con is more than comics. More than the merchandise packed into over-sized shoulder bags. More than the cosplay enthusiast and doodad collectors. It’s not the sneak previews or the special surprise guests ... it’s the freedom to geek out in wild abandon, to enjoy freely and without judgment. It’s the best part of fandom. It’s the best part of excitement and dedication. It’s generosity of spirit. It’s the best part of thousands of people in one place at one time.” But, whatever it is, it’s “more than comics.” Back-handed, as I say. The week that began with the EW’s Batcover about Nolan’s “Dark Knight” continued with Rush Limbaugh, who decided that the movie’s arch villain, Bane, had been concocted deliberately to benefit Barack Obama’s bid for prez by branding Mitt Romney, the Ken-doll candidate, as evil because he founded the sound-alike Bain company, a vicious venture capital operation. Saith Rush (write this down: we’ll refer to it again): "Do you know the name of the villain in this movie? Bane. The villain in the ‘Dark Knight Rises’ is named Bane. B-A-N-E. What is the name of the venture capital firm that Romney ran, and around which there's now this make-believe controversy? Bain. The movie has been in the works for a long time, the release date's been known, summer 2012, for a long time. Do you think that it is accidental that the name of the really vicious, fire-breathing, four-eyed whatever-it-is villain in this movie is named Bain?” It was clear as crystal to Rush. The Batman movie was a Democrat conspiracy to discredit the plastic plutocrat’s bid for high office. And it was equally clear to many of Rush’s listeners and to comic book fans who heard about it. And they spewed forth opprobrium in vast quantities. Even Rush was impressed: "I have had more reaction to that than anything—including the Fluke thing," he said, referring to the outrage that erupted earlier this year after he called Georgetown law student Sandra Fluke a "slut" and a "prostitute.” In the heat of this new uproar, Rush pronounced that he had not, not really, said Bane was in the movie to discredit Bain and, thereby, Romney. Vehemently, he claimed he’d been misquoted. As Ethan Sacks in the New York Daily News said, conservative comic book fans have long recognized “a school of thought that Bruce Wayne—a billionaire with a passion for law and order issues—would naturally be a Republican.” Sacks goes on to quote Rush: "I even said yesterday, at the end of my whole Batman discussion, that Batman is more like Romney," Rush said in the wake of the disturbance. "Made the point that the rich, wealthy hero in the Batman movie is more like Romney and that the Bane guy seems more like an Occupy Wall Street guy. And yet, here I am, supposedly articulating a conspiracy between the comic book creators and the Obama campaign that somehow they created this villain with the same name as Romney's private equity company. No, all I said yesterday was that the Democrats are going to try to make that linkage." No: that’s not quite all he said yesterday. And on her MSNBC show, Rachel Maddow played the tape of Rush’s initial pronouncement (which I’ve quoted verbatim above) to keep the blowhard honest.

EDITOONISTS ROB

TORNOE AND MIKE KEEFE supply a visual transition between the high

comedy of Limbaugh’s silliness to the shock of the movie theater slaughterhouse

at the end of Batweek. Many at first thought they were witnessing special effects created for the movie’s debut. It wasn’t until they began to choke on the smoke and fumes that they realized they were the victims of a cruel plot. “The dark theater quickly filled with acrid smoke,” said the Denver Post report. “Moviegoers dropped to the floor and crawled over one another to get out. Some dragged out bloodied bodies, lining them up in the lobby. ... After exhausting the shotgun rounds, the gunman calmly dropped the weapon and resumed firing with the rifle as he made his way up the aisle.” The good news: police were on the scene within 90 seconds of 12:39 a.m. reports about the shooting; one of Holmes’ guns jammed, resulting, presumably, in less loss of life; and out back of the theater, Holmes was captured without making any resistance. Once Holmes was in police custody and his identity ascertained, police went to his apartment, which turned out to be booby-trapped with 30 golf-ball sized explosive devices, connected by trip wires intended to set off the explosions as soon as someone came through the door. Clearly, Holmes had carefully planned his midnight massacre. The movie’s director, Christopher Nolan, released a statement on behalf of the cast and crew of “The Dark Night Rises”: “I would like to express our profound sorrow at the senseless tragedy that has befallen the entire Aurora community. I would not presume to know anything about the victims of the shooting but that they were there last night to watch a movie. I believe movies are one of the great American art forms and the shared experience of watching a story unfold on screen is an important and joyful pastime. The movie theater is my home, and the idea that someone would violate that innocent and hopeful place in such an unbearably savage way is devastating to me. Nothing any of us can say could ever adequately express our feelings for the innocent victims of this appalling crime, but our thoughts are with them and their families.” Almost immediately after the news broke, the usual uproar about gun control commenced. Those who seek tougher laws will, as usual, be frustrated because politicians are paralyzed with fear. As Roger Ebert put it: enacting any laws about restricting the sale or possession of firearms is doomed because “the issue has become so closely linked to paranoid fantasies about a federal takeover of personal liberties that many politicians feel they cannot afford to advocate gun control.” The Washington Post’s E.J. Dionne Jr. echoed Ebert’s sentiments, adding that one of the gun lobby’s favorite maneuvers in the immediate aftermath of such a slaying as this is to head off stricter gun control laws by accusing anyone advocating reform of “exploiting” the deaths of innocent people. Said Dionne: “God forbid that we question even a single tenet of the theology of firearms.” Close on the heels of these gun lobby machinations is another favorite: if everyone is carrying a gun, we’d all be safer because the Holmeses of the world would be quickly shot before they could do much damage. Really? Prudence suggests that returning fire in a dimly lit theater full of smoke is scarcely a guarantee of safety or survival for innocent onlookers. No matter: background checks for people wanting to buy guns in Colorado jumped more than 41 percent on Friday after the shooting was reported. We’ve tried restricting the sale of weapons. But whatever the restrictions, they won’t catch every culprit. All Holmes’ weapons were obtained legally, as were 6,000 rounds of ammunition, the latter purchased over the Internet and delivered to his home over a period of weeks so as to avoid arousing suspicion. If we can’t solve the problem with tougher gun laws, then maybe we can successfully prevent the sale of weapons to mentally unstable persons. Not likely. We tried that, too. Seung-Hui Cho, the Virginia Tech shooter, was reported unstable several times before he went on his rampage killing 32 and wounding 27. Chuck Murphy at the Denver Post said that a former professor who’d had Holmes in his neuroscience classes (in Holmes’ Ph.D. program) spoke anonymously (how brave, saith Murphy) about how Holmes was “very quiet, strangely quiet” in his class and “socially off.” That same faculty member said he actually wasn’t surprised when he learned that the James Holmes he knew was the accused gunman. “Let that sink in,” Murphy finished. We just haven’t adequate mechanisms to diagnose the deranged without endangering civil liberties willy nilly. We seem to be better at catching the mentally unstable after they’ve committed some offense than we are at heading them off before they do something. “For the past 50 years,” Murphy writes, “inpatient treatment of the mentally ill has moved from hospitals to jails,” and he quotes a recent study that notes the number of beds available for inpatient psychiatric treatment has fallen from 339 per 100,000 Americans in 1955 to 22 per 100,000 in the year 2000. “Either we have gotten a lot saner as a nation, or we have chosen to ignore the real problem. Other evidence suggests it is the latter.” Today, he continues, the percentage of our inmate population suffering from psychiatric conditions “stands between 16 and 24 percent,” and they receive “only the bare minimum in treatment before being released at the completion of their sentences.” And with the Batweek massacre, we’ve already started to label Holmes’ disorder. Reports circulate that he had colored his hair red and called himself the Joker when arrested. The impulse here is to blame his reading of comic books for his behavior. But the Joker has green hair, which, if Holmes were a fanaddict about comics, he’d have known. My guess is that before I post this, the red-haired Joker rap will have been disproved. The final clue to its lack of validity: the cops found no comics or Batman movie posters or anything else remotely connected to comic book mythologies in his room. All they found was bombs. Holmes’

costume for the evening was more Bane than Joker. The image, however, lends itself to another albeit erroneous interpretation: in a quick reading that overlooks the label across Batman’s chest, Batman himself seems to be attracting the crows and their gunplay. Ergo, comic book superheroes (particularly of the psychotic sort like Batman) encourage violence in real life. And that interpretation will surface soon if it already hasn’t by the time you read this. If Batman isn’t blamed, he is, thanks to Holmes, forever branded. At the New York Times, Ross Douthat held forth: “The villains in Nolan’s Batman trilogy are distinctive, even by the standards of summer-movie bad guys, in that they seek nothing but destruction. Money does not sway them, political power does not interest them, and any ideological posturing—Bane, the villain in ‘The Dark Knight Rises,’ poses for a time as a left-wing revolutionary—is a flag of convenience, a mask to be worn and then discarded. Some of the villains are lunatic moralists for whom Armageddon is the purifying punishment that modern civilization deserves. Some of them are lunatic nihilists, men who (as Bruce Wayne’s butler, Alfred, says of the Joker) ‘just want to watch the world burn.’ Either way, they cannot be bargained with or reasoned with, and all they want from us is death. “Now Nolan’s fictional villains and a very real one will be forever intertwined, after James Holmes massacred moviegoers at a midnight screening of the movie. Mass murderers usually seek the spotlight, and by exploiting a cultural phenomenon that trades on our fears of precisely the kind of evil that he represents, Holmes fastened on a horrifying resonant way of solidifying his own notoriety. In the process, his crime has probably also solidified the Batman movies’ status as a cultural touchstone for our era of anxiety.” And that’s too bad. By all accounts among critics, “The Dark Knight Rises” is a stunning success, much more than a touchstone for our era of anxiety. Time’s Richard Corliss said TDKR may not top the year’s earlier megahit, “The Avengers,” but part three of Nolan’s trilogy is “for grownups, with bold nuanced performances ... and apocalyptic import. For once, a comic-book movie comes within hailing distance of the Greek mythos or a Jonathan Swift satire. ‘The Dark Knight Rises’ is that big, that bitter—a film of grand ambitions and epic achievement.” But it bears a brand now. Beyond branding Batman, Holmes’ rampage may change forever how we go to the movies. We are already hearing from various quarters about the likelihood that metal detectors will be installed in movie houses, and some theater operators have announced that they will no longer permit patrons to come in costume. Neither of these maneuvers that would have frustrated Holmes, who entered the theater without arms or armor. In our final exemplary cartoon, David Fitzsimmons captures in a single image the now-familiar post-tragedy ritual enacted in the nation’s mass media. It’s a game, just another game, with sadly predictable moves. But the uproar will soon subside, as it has so often in the past. Any unbiased reading of the Second Amendment yields only one opinion: possession of personal firearms is guaranteed by the Constitution. And it’s unlikely that the Constitution will be amended to ban private ownership of weapons. Guns are too deeply ingrained in our culture to be legislated away. Instead, we will simply learn to live with spasmodic episodes of abhorrent killing of the kind we’ve just witnessed in Aurora. Inexplicable massacres of this kind will be accepted as casually—albeit, sorrowfully—as multi-car accidents. They’re just part of modern life. Can’t help it. We’ve already moved a long way in that direction. Columbine, another Colorado shooting, has already become but a distant although tragic memory. How will we cope? By heeding the observations and advice of Michael Johnston, a Colorado state senator. “James Holmes took 12 lives Friday,” Johnston wrote in the Post, but “love saved 28 lives. Policemen on the scene in minutes, strangers carrying strangers, nurses and doctors activated all over the city” in six hospitals to care for the injured as they were brought in, often by policemen who’d loaded up their patrol cars with wounded or by private citizens eager to help any way they could. “How do we fight back?” Johnston asks. “The answer is we love back. We deepen our commitments to all the unnumbered acts of kindness that make America an unrendable fabric. ... In a movie theater in Aurora 50 years from now, one of Friday night’s survivors will be waiting in the popcorn line and mention that he was in Theater 9 on that terrible summer night in 2012. And, inexplicably, with an armful of popcorn, a total stranger will reach out and give that old man a huge hug and say, ‘I’m so glad you made it.’ “Love back. “We’ve already won.”

San Diego Comic-Con International STUPENDOUS!!! That’s the only word for it. Stupendous!!! With at least three exclamation points hammered onto the end. And an emphasis on the “stupe” and a sob at the “endous.” It’s the Grand Bazaar of Geekdom. On the ground floor of the city’s gigantic convention center, from one end of the exhibition hall to the other, the marketplace stretches out: starting with stuffed animals and t-shirts at one end, the exhibit booths march down the aisles eddying with milling humanity. The booths display comic books new and old, graphic novels, fantasy weaponry, small press publications, illustrators’ wares, and video games and toys for all ages. Two-story displays loom over the aisles to tout DC, Marvel, IDW, Image, Dark Horse and then Lego, Mattel, Hasbro, and Lucasfilm.

The aisles are a human slurry, polluted profusely with people in colorful costumes. Not just the costumes of funnybook superheroes: numerous other fantasy characters abound, and many cosplayers (a new geek term combining “costume” and “player”—i.e., actor) wear costumes of their own manufacture, cloaking characters of their imaginations in the raiment of fictional “reality” for the nonce—for young and nubile women, the briefer the wardrobe the better. One guy was naked from the waist up, skin-tight flesh-colored leotards below the waist. Asked if he were a new, unknown superhero or just a guy in his underwear, he confirmed the latter. Zombies wore no particular costumes: they just splashed themselves with imitation blood and gore and lurched into the slurry. On my first entering this teeming amalgamation, I had the eeriest sensation: I felt at home. “At home”? In this menagerie? Near naked bodies, colorful skin-tights, staggering zombies? “At home”? When I mentioned this feeling to Luann’s Greg Evans, he grinned: “You’ve passed over,” he said. “You should be very worried,” said Keith Robinson, overhearing my confession. But later, on my way back home stopping to visit an old friend in Berkeley, he reminded me: “You and I have been counted among the weird of the world all our lives. Nothing new here.”

I ARRIVED ON THURSDAY this year. For all but one of the previous 21 years, I’d come in on Wednesday in time for Preview Night. But this year, the complexities of registering for the Con nearly defeated me: were it not for the intervention of a Con staffer on my behalf, I would have failed to registration altogether. And getting a hotel room proved well nigh impossible. I was tuned in at the announced hour that hotel reservations opened, but, within five minutes, all of the downtown San Diego hotels were fully booked. I tried for Mission Valley: I named two hotels then checked the block that instructed the factotums running hotel reservations to book me into whichever of the other hotels was available. A week later, I got a response: None of your requested hotels are available. None? In the last analysis, I’d asked for “whatever was available” and there were none of those? Again, I prevailed upon an acquaintance. Suspecting that hotel reservations open for exhibitors before us hoi polloi get a shot at them, I pleaded with an exhibitor whom I know to book me a room on his company’s rooming list, but the room wasn’t available on Wednesday. So I arrived on Thursday morning. The point of this divarication is that gaining entrance to the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con has become needlessly complicated by (1) the sheer number of attendees (limited to 130,000 by the San Diego fire marshal) and (2) the “new improved” computer programs for registration and housing. Before one can register, one must obtain a “member ID,” a procedure littered with hoops to jump through. And after getting a “member ID,” you wait until your computer tells you to register. Professionals, among whom I number, wait even longer. And then if you’re not at the keyboard for the few hours “pro registration” is open, you lose. On-site, picking up one’s name badge (the emblem of being registered) was simplicity itself. Lines evaporated before my very eyes. I wandered into the cavernous exhibition hall, and after stopping to say hello at the National Cartoonists Society’s booth (to which I’d return whenever I needed to sit down and rest), I spent a couple hours browsing in the venue of small presses. This is my favorite section of the exhibit—an enclave where cartoonists, artists, and other craftees display their wares. Most of the cartoonists are animators during the day, and they are impressively skilled: the energy of their drawings is infused with a surpassing quality of design quality; their booklets and posters and postcards are a feast for the eyes. Not all the Small Press exhibitors are animators. I said hello to Keith Knight and Stan Yan (of Denver) and Sergio Aragones at their display tables. Knight has a new collection of his K Chronicles out, The Incredible Cuteness of Being, featuring cartoons about his “progeny” (i.e., his child) and America’s first black president. And I ran into John Jennings, a comrade from my former Illinois environs, lately moved off to the East Coast. I stopped at Bill Holbrook’s table: it was his first Comic-Con, and he was selling the books that reprint two of his comic strips, Kevin & Kell and On the Fastrack, from the latter, the collection features his newest character, Dethany Dendrobia, a corporate goth. Andrew Pepoy thrust into my hand a copy of his latest self-published comic book, Monica Moon, a space fantasy with a leggy heroine; visit spicytomato.com. I saw Randy Reynoldo and picked up a copy of his latest Caniff-style Rob Hanes Adventures, No.13, as crisply rendered as ever. Reynoldo’s handling of solid black is not as drenching as Caniff’s, but the clarity of his line and his adroit use of gray tone evokes the best of Caniff’s pre-war work on Terry and the Pirates. Find Reynoldo at wcgcomics.com. At Ryan Claytor’s table, he told me about his autobiographical graphic novels in which he is exploring the nature of autobiography. In one of his collections of strips, And Then One Day, he announces that since autobiography is just one person’s subjective opinion of himself, it is no more truthful or valid than fiction, and so he decides to strive for greater objectivity by assembling an autobiography from the opinions that friends and acquaintances have of him. He devised a series of questions on flash cards and put friends in front of a tape-recorder to answer the questions. Then in the book, he reports what they said, depicting each of them speaking directly to us (“into the camera”). In effect, they write the book. “In this book,” as Supernatural Law’s Jackie Estrada says in a blurb, “we learn all about cartoonist Ryan—the good, the bad, and the smelly—from everyone else’s perspective.” Claytor’s work-in-progress is entitled Autobiographical Conversations, and in it, he avidly, doggedly, pursues answers to questions he has about the validity of autobiography, discussing the issues with a college English professor. Should an autobiography aim for factual truth or emotional truth? Which is truer? They go around and around, digging deep into esoterica. The book is mostly talking heads, but at the end, the talking stops, and pictures take over. Claytor is, after all, a cartoonist, and it is autobiographical comics he wants to produce. In the closing pages he depicts himself puttering around his room, e-mailing the professor with more questions and ideas. Here, his narrative achieves its authenticity. And that may be what every autobiography should strive for. For more, visit ElephantEater.com. Leaving the Small Press “Pavilion” (as they call similar clusters of kindred productions—elsewhere, f’instance, the Gold and Silver Age Pavilion for old and newer comic books), I headed for Batton Lash’s booth, 1909, where he sells and autographs reprints of his famed comic book creation, Tales of Supernatural Law in which two attorneys, Wolff and Byrd, go to court on behalf of monsters and other malefactors of horror—the lawyers are “counselors of the macabre,” it says on the covers—aided, in some cases, by their secretary Mavis. Lash is renowned here at Rancid Raves for the clarity of his line and the precision of his compositions—and, in person, for his wardrobe. Although typically attired in a three-piece suit, he usually completes his costume by wearing tennis shoes. This year, he had given up tennis shoes in favor of striped socks, at which, as you can see in the accompanying visual aids, he is bested by Yrs Trly, wearing rainbows.

I took the photos at his booth as he autographed the book I bought and then as he entered into a spirited discussion with an actress who desperately wants to play Wolff, the platinum blonde half of the starring partnership. The actress, whose tresses are black, said she’d wear a blonde wig—anything to get the part. That evening, I was on a panel about “The Myth of Nostalgia: Collecting and Memory.” I met fellow panelists Bob Foster (of Moose fame), Grant Geissman (EC expert), Pete Maresca (Sunday Press) and Kirstie Shepherd and Cesare Asaro, creators of the most elaborate and entertaining hoaxes: they manufacture nostalgia in the form of two volumes that ostensibly reprint the popular comic strip Frank and His Friend, by Clarence “Otis” Dooley, who died in 1984. Like Dennis the Menace, Frank and His Friend appeared as a panel cartoon on weekdays; comic strip format on Sundays. But there is a difference: Frank and His Friend never existed as a syndicated cartoon. It’s all made up, its history, its creator—all of it, pure fiction. One of the books is of the dimension and production values of IDW reprints; the other, Time for Frank and His Friend, takes the form of a paperback reprint of the kind we no longer see in the stores, a little 4x7-inch tome (with the hoax price, $1.25, proclaimed in the upper right-hand corner of the cover; but its actual cost is about $15). Both books, magnificent fakes—perfect in every detail. The larger of the two, Finding Frank and His Friend ($40), publishes for the “first time” penciled versions of printed strips that, it is claimed in the Foreword by Melvin Goodge (who also annotates the contents), were found in a box by Dooley’s son Lance while “remodeling the family’s home in Sandusky, Ohio to expand the jigsaw puzzle room to accommodate 5000-piece projects.” (If that snatch of syntax doesn’t tip you off to the hoax being perpetrated, the “About the Author” note on the preceding page ought to: “Melvin Goodge is a tenured professor at the Huntley Smoot University of Comic Sciences and serves on the selection committee of the university’s prestigious Inker-in-Residence program.” Melvin Goodge is actually Shepherd.) As we see hereabouts, the pencil sketches of strips appear throughout the book on the left-hand pages, facing the ostensibly “published” version of the same cartoon or strip. Asaro’s lively pencils are deftly translated into ink and then colored. Asaro enhances the illusion of authenticity by “aging” the final “printed” version, tinting the “paper” newsprint brown and adding a mildew stain or two. Delicious. Hereabouts, preceding copies of a two-page spread from Finding are photos of Asaro and Shepherd at their table. Delicious.

Both books are available on Amazon, or at the website of the “publisher,” Curio & Co., curioandco.com. At Amazon, we find this: “Curio & Co. creates collectibles and memorabilia from an alternate history—pop culture that never was—to play with the power of nostalgia to re-create warm memories from the past. ... Their latest book, Time for Frank and His Friend, ‘brings back’ U.S. paperback comics published in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. The book is designed as a 1979 first edition paperback comic by fictional artist Clarence 'Otis' Dooley, creator of Frank and His Friend, a popular comic strip featured in newspaper funnies. This book, Time for Frank and His Friend, recreates the moment when popularity for the newspaper comic swelled. To meet the demand of fans, Dooley created all new work for a paperback, rather than publish a collection of strips previously printed in newspapers.” The best fake around. And funny, too. Delicious.

I MADE MY WAY to the opposite end of the massive exhibit hall to sample the wares in Artists Alley. En route, I saw Stan Lee plunging through the crowd with an associate running interference for him; they looked as if he was headed for a scheduled appearance somewhere. Stan Lee was present all over the Con: posters and giveaway cards announced another of his latest endeavors—Stan Lee Comikaze, “the official convention of Stan Lee, L.A.’s largest pop culture expo. Comics, gaming, horror, sci-fi, anime—cosplay and TCG tournaments with 1000s in cash prizes!!!” September 15-16 at the L.A. Convention Center; comikazeexpo.com for more. In the exhibit hall, you can’t walk faster than the slurry moves: it’s too thickly populated, visceral almost, impenetrable. Once in the flow, you go with it. I escaped the current briefly by leaving the hall to make my way through the slightly less dense mob in the lobbies of the halls. I heard my name shouted and turned to see Frank Cho, who wanted to know what I’d been up to. I was telling him about my 24-hour comic experience, when a security guard approached us. “You have to keep moving,” he said. “You can’t stand here.” “Here” was the lobby, simply an open space; but it’s also a gigantic traffic pattern, and we were, it seems, blocking it. Two people in a wide ocean of space—admittedly filled with milling bodies, but still, lots of room. Like sharks, we had to keep moving. The Con is a police state. Security guards are posted about every twelve feet. Their assignment is to prevent you from doing anything that might interfere with the traffic flow. Or might, in the event of a conflagration, prevent the crowd from quickly leaving the premises. A kid was leaning against one of the doors in a bank of doors leading into (and out of) the exhibit; the door was closed, not needed for entrance and egress during “open” hours. But if a fire broke out, the crowd inside would doubtless push through that bank of doors, including the one the kid was leaning against. A guard told him not to lean against the door. The hallways at the upper level of the Convention Center run between banks of meeting rooms, and for the duration of the Con, they are designated one-way halls; if you try to go the “wrong way” down one of these one-ways, a guard stops you and turns you around so you’re obeying the signs. I finally reached Frank Cho at a table in the Illustrators Pavilion. He’d produced a 2013 calendar for the occasion, and he told me he’s hoping to direct soon a movie that he wrote. Meanwhile, he’s drawing Wolverine. Across the aisle, Stan Sakai handed me a copy of his latest sketchbook, which, in addition to representative pictures of his samurai rabbit Usagi Yojimbo, includes breakdown sketches for a 6-page story published therein and a two-page extravaganza in which Sakai interviews Usagi.

WHENEVER I GOT TIRED OF WALKING AND STANDING, I took refuge at the National Cartoonists Society’s booth, where I could sit down. Or I went to a panel presentation in a meeting room in the upper reaches of the Convention Center. On Friday, I went to a session about Siegel and Shuster and Finger, featuring the authors of two new books: Larry Tye, Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero; and Marc Tyler Nobleman, Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-creator of Batman (i.e., Bill Finger). According to Tye, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were a pair of underdog geeks living in Glendale, a mostly Jewish suburb of Cleveland, where they created the Man of Steel. Tye finds elements of Jewish culture in Superman—his Judaic-sounding name, Kal-El (“El” in ancient Hebrew meaning “all that is God”), his Moses-on-the-Nile arrival on earth in a space capsule shot from the disintegrating Krypton. Said Tye: “When a last name ends in ‘man,’ the bearer is Jewish, a superhero—or both.” Tye sees Siegel and Shuster as bullied kids who semi-consciously saw themselves as mild-mannered, spectacled youths like Clark Kent, scorned by the girls but, in reality, superheroes under their outerwear. This supposition flies on only one wing, methinks. Some years ago, I gave a presentation about how Jews invented comics (nor not) at the adult education program of a nearby Reform Jewish temple founded by a friend, and I followed the usual line about Siegel and Shuster being put-upon nerds who invented Superman as a balm to their bruised adolescent egos. And then a member of the audience arose to say that in the mostly Jewish community of Cleveland’s Glendale, every kid in school was a “nerd” if “nerd” meant striving for academic excellence and ignoring football and other such extracurricular preoccupations of teenagers. “Nerds,” in other words, would not be denigrated or ostracized in such a community. Well, maybe so; but Siegel and Shuster weren’t making points with the female population like they wanted to, and that may have made them feel like outsiders even among fellow nerds. One of Tye’s sources for Siegel’s feelings of being a bullied outsider in high school is an unpublished memoir Siegel wrote. But I have to wonder how reliable such a document is: Siegel was, after all, a storyteller, and if he portrayed himself as bullied and ridiculed as a teenager, that made his story a little more interesting. Tye also sees Superman as a fiction that dominated popular entertainment in all its forms like no other, and for longer. I wanted to remind him that Tarzan did all that Superman did (except fly and bounce bullets off his chest)—comic books, comic strips, radio, tv, Saturday cartoons, plus prose novels—but I didn’t get the chance because there wasn’t much of a question period. Tye’s last utterance was about Shuster, who, he said, “was really a good guy who never quite got justice at the end.” The other half of the presentation concerned Bill Finger, who did as much, probably more, than Bob Kane to create Batman: Finger wrote the Batman saga. In a belated recognition of Finger’s contribution to comics history, the Eisner Award for comic book writing is named after him. Mark Evanier, who was moderating the panel (and sometimes, as is his wont, dominating it in order to elicit comment from those on the dias), engaged in some frivolous word play about the Finger Award, saying it was fandom’s way of “giving the Finger” to an industry that had ignored for so long one of its chief architects. It was Jerry Robinson, another of Kane’s creative stable in the early years, who proposed that an award for comic book writing be given in Bill Finger’s name. He phoned me one time, a couple years before the award was invented, asking what I thought of the idea. “Of course,” he cautioned, “we’ll have to be careful how we refer to the award—probably shouldn’t call it just ‘the Finger Award’; always the Bill Finger Award.” He doubtless knew that was a futile caution.

ON SATURDAY, I went to a session touting Archie Comics—chiefly because the program listed Nancy Silberkleit as being on the panel as well as co-publisher Jon Goldwater with whom, I thought, she was on the permanent outs. In fact, last I heard, she had been enjoined not to make appearances on behalf of Archie Comics and not even to go to the office. Yet here she was. A possibly reliable source next to me in the audience opined that there had been some sort of “settlement.” Silberkleit,

the widow of the son of one of the company’s founders, opened the proceedings

by reading from a prepared written statement about her aspirations for Archie

Comics. Nothing inflammatory or revealing therein. But she’d doubtless been

permitted to talk only if she submitted her remarks to the Archie moguls in

advance—and, dutifully, she said nothing else the whole hour. I attempted a

caricature of her at the bottom of the visual aid nearby; I got the snarl

right, I think, but not the rest. Missed on the hair altogether. I submit,

however, that I produced more acceptable renditions of Michael Uslan, Jon

Goldwater (the better of two versions is on the left), and Victor

Gorelick, Archie’s long-time editor. His expression, a sort of bored

tolerance, didn’t change for the whole hour. He chewed gum with determination

and stared at the microphone in front of him. When I saw that famed ug cartoonist Gilbert Shelton was spotlighted, I went to see what he would say. (“Say” in a manner of speaking: I don’t hear well enough to hear whatever most people “say” from the dias. But I sort of read lips; hence, I “saw” what he had to say.) Shelton doesn’t get to this country much from France, where he, like R. Crumb, now resides, but his hand has lost none of its facility. As he talked, he drew a couple of his characters, and an overhead projector let us watch them materialize as he drew.

Earlier, the technician running the gadgets had asked me to loan him a piece of paper from the sketchpad I had on my lap. Shelton drew on my paper, and afterwards, I told the technician I wanted my paper back. No cigar. I also went to a session featuring four syndicated newspaper cartoonists—Morrie Turner (Wee Pals), Bill Amend (FoxTrot), Greg Evans (Luann), and Lynn Johnston (For Better or for Worse), who, by virtue of her animated facial expressions (on an attractive face) commanded the attention of my camera on the visual aids posted nearby.

I WENT TO THE

EISNER AWARD CEREMONY on Friday evening. I’ve never gone before. I would have

gone the year I was almost up for one (for my biography of Milton Caniff)—but

the nomination, by the publisher, Fantagraphics, wasn’t enough to secure me a

position among the finalists. So I didn’t go. I’m not sure anyone attends who

is not a nominee or the family or friends of a nominee. Why would anyone else

go? Apart from a passable buffet dinner for nominees and presenters (drinks at

your own expense), the attraction must be entirely the prospect of winning an

Eisner (officially, the Will Eisner Comic Industry Award). Otherwise, you sit

and watch a parade of presenters announce the nominees in each of about thirty

categories (that means listening to about 150 names of creators and their

creations being rattled off), followed, in each instance, by a shorter parade

of winners, who come to the podium to accept their statuette and express their

appreciation and gratitude. All worthy activities, no question, but of

interest, almost entirely, as benchmarks in the history of the medium not as an

evening’s entertainment. I was invited to accept for Rudolph Dirks, who was being inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame. A pioneering newspaper cartoonist who has been dead since 1968, Dirks’ achievement—and, hence, his right to a place in the Hall of Fame—might not be readily apparent to an audience of today’s funnybook fans, so I was instructed to acquaint them with Dirks’ works. Dirks is eminently qualified for the Hall of Fame solely as one of a triumvirate named by comics historian Coulton Waugh as “founders” (or creators) of the newspaper comic strip, which, Waugh proclaimed, consisted of three elements: (1) a narrative sequence of pictures in which (2) speech balloons are included in the drawings, the combination showcasing (3) a character or characters who reappear with each publication of the feature. This last quality seems to me to be somewhat trumped up. The first two aspects of the medium are rooted in its form; the third refers to content. As I’ve said elsewhere on other occasions, clearly, a narrative sequence of pictures in which the characters speak through balloons is a comic strip whether or not the characters appear again and again. Waugh’s character qualification was probably tacked on in order to eliminate all predecessors to the Yellow Kid. According

to Waugh, the continuing character aspect of the a-borning comic strip was

contributed by James Swinnerton, who was cartooning a cute bear cub in

the San Francisco Chronicle through early January 1894, and by Richard

Outcault, whose Yellow Kid debuted in 1895. The narrative sequence of

pictures, saith Waugh, was tried out experimentally by Outcault, used regularly

for the first time by Dirks, and refined in technical details by Swinnerton.

And including speech balloons in the drawings began sporadically with Outcault

but was developed into true comic strip form by both Dirks and Swinnerton, as

well as by Outcault in his later work. But mostly—and most consistently—by

Dirks, who, after a couple pantomime strips, sometimes with captions beneath

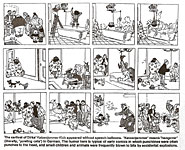

the pictures, resorted to speech balloons routinely after the debut of his Katzenjammer

Kids on December 12, 1897. Waugh was wrong about the earliest sequencing of narrative pictures: “strips” of this kind had appeared in numerous forums well before Outcault’s use of the maneuver—notably in weekly humor magazines on both sides of the Atlantic. For the pure sake of closing the circle on the invention of the newspaper comic strip form, we need Outcault, Swinnerton, and Dirks in the Hall of Fame. Outcault is already enshrined therein; now, this year, it was Dirks’ turn. Swinnerton maybe next year; and maybe Coulton Waugh, too. He was the first to attempt anything approaching a comprehensive history of the American newspaper comic strip in his 1947 book, The Comics. But this year, it was Dirks. Apart from being a member of Waugh’s triumvirate, Dirks deserves to be in the Hall of Fame for at least three other reasons. His Katzenjammer Kids is the longest running newspaper comic strip: a Sunday only strip now produced by Hy Eisman (who also produces the Sunday Popeye), it’ll be 115 years old next December. But Dirks himself created another landmark in the medium’s history. He established by law suit the legal right of a cartoonist to his creations, his characters. According to the myth that has arisen about the event, Dirks wanted to take a vacation in 1913, but his employer, William Randolph Hearst, didn’t want to let him wander off for as long as Dirks wanted to go. Dirks went anyway. Hearst hired someone else to produce the Katzenjammer Kids in Dirks’ absence, and when Dirks came back from his jaunt to Europe, Hearst declined to give him his old job back. Dirks then went across the street to a rival paper and drew the Katzies there. Hearst sued. The judge ruled that while Hearst owned the title of the strip, Dirks owned the appearance of the characters. So Dirks retitled his rogue creation Hans and Fritz (after its juvenile delinquent stars) and plunged onward. It was later re-titled again, The Captain and the Kids, because, during World War I, all things Germanic—like the names of the Tectonic Twins (which had been inspired initially by the German cartoonist Wilhelm Busch’s Max and Moritz —were rigorously eschewed. But Dirks and his Kids are also responsible, albeit somewhat indirectly, for the emergence early in the medium’s history of the erroneous supposition that newspaper comics were for children, not for adults. Fact is, the comics were always for adult readership: the Sunday supplements in which they appeared initially were concocted in imitation of the weekly humor magazines (Judge, Puck, and Life), which were addressed to adult readers. But the low-brow antics of the Katzies and the Yellow Kid and other early evidences of that ilk disturbed “decent citizens” who found these strips “vulgar”—probably a bad influence on children should they fall into sweaty young hands. Which they almost certainly would, the paper being for the whole family after all, children as well as adults. To appease the protestors, newspaper editors began to remind their cartoonists to draw for the whole family, children as well as adults. They were advised to keep the child reader in mind when devising pranks for their kid protagonists. Cartoonists’ consciousness about child readers being raised, they drew their cartoons for the whole family—children as well as adults, making sure that nothing the kids in the comics did would set bad examples for child readers. Ergo, by the sort of leap of rationale for which our mass media are distinguished, comics were, perforce, for children. Outcault subsequently launched another comic strip, Buster Brown, the weekly installments of which featured Buster’s mischief but ended by blatantly enunciating a moral that advised against deviant behavior. Dirks’ characters were distinguished by the violence of their pranks and were therefore surely among the most “vulgar” of their four-color brethren, exemplifying as few other funny page fictions did, the vulgarities about which decent citizens complained. Thus, Dirks can be seen as among the chief causes for erroneously labeling newspaper comics as child fodder. For that alone, Dirks deserves a niche in the Hall of Fame. I am not a big fan of awards in the comics business. They are, with only a few notable exceptions, popularity contests rather than reasoned assessments of the artistic excellences of the awarded works. But among the Eisners awarded this year were several that I applauded because the artistry deserved the recognition. Jim Henson’s Tale of Sand picked up three awards—best penciler/inker (Ramon Perez), best design (Eric Skillman), and best new graphic album. As I told Perez as he walked off the stage with his Eisner trophy in hand, if anything could revive my faith in the efficacy of awards of this kind, his winning for penciler/inker would do it. Darwyn Cooke was recognized for best short story and best graphic novel reprint for his work with Richard Stark’s Parker, and Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips with their Criminal endeavor got best limited series. The works of two creators were recognized with awards that seemed tangential to their actual achievements: Roger Langridge got best publication for kids with Snarked although I don’t see that excellent title as kiddie lit; Stan Sakai got best lettering for Usagi Yojimbo but he deserves an Eisner for his long-running storytelling achievements with that title. Morrie Turner received the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award for his labors on behalf of bettering common humanity in his comic strip Wee Pals, wherein children show us all how a diverse society should behave. Bravo.

FINALLY, AS A CONCLUDING FLOURISH, a few of the photos I took outside the Convention Center. In an effort to portray the venue from the exterior, I shot at the milling throngs and successfully captured evidences of this year’s phenomenon—namely, the yellow signs held aloft by the Inspired Righteous, urging us all to come to Jesus. I don’t begrudge their enterprise in seizing the opportunity to display their convictions before the largest crowds in San Diego, but I do find the use of children as shills a little discomfiting. Isn’t that child abuse? Surely the children don’t understand fully the implications of what they’re doing; so they’re doing it at the behest of their parents and/or teachers, who are cajoling (or enticing) them to do something they would not, of their own volition, do. Isn’t that a form of child abuse? Finally (again and at last), at the end of the ensuing Gallery are glimpses of the interiors of books I acquired while lurking through the Small Press Pavilion. Delicious stuff. I like the sketchbook sort of publication so much I’m never able to control completely the impulse to take large bundles of them home with me. You’ll notice a high percentage of female nudity per square inch. I don’t know why that is; I don’t know why I seem attracted to that sort of picture. But I am. Biology, I suppose. Or some other impulse. Take, for example the cover to the Craig Elliott book. A barenekidwoman. I bought this book, however, because its dust jacket (the one on display here) is the “original” painting. The publisher, Elliott told me—Flesk—was leery of bringing out a book with such blatant nudity on it. So Elliott did a second version of the same painting, this time with a shred of two more clothing. Flesk still leery. Elliott did a third painting with lots more garment on display. Books with all three dusk jackets were on display in his booth. I bought the “original” so I’d have this story to tell.

And if you want to see cosplayers galore, go to ICv2.com and click on Comic-Con in the blue box at the left; that’ll take you to dozens of photos of costumed geeks.

INCIDENTALLY, the dates for next year’s Denver Comic-Con: May 31-June 2, 2013.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping AS PROMISED LAST TIME, here’s the week of Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts celebrating the Comic-Con.

And in our second visual aid, we see that Hector Cantu and Carlos Castellanos have taken their eponymous Baldo (with his buddy Cruz) to the Comic-Con in a much more authentic representation of what transpires among those multitudes. At the bottom of the page, we’re back at Mutts, this time to observe the visual impact that this installment achieves. Back in the day (as they say—but what does it mean, actually?), strip cartoonists every once in a while did something eye-catching like this, seeking to captivate the roving eyeballs of comics page readers. And here, McDonnell is remarkably effective. On

our next exhibit, a couple more eye-catchers, this time in Mort Walker’s Beetle

Bailey. Returning to Baldo for the rest of the page, here we have quite another sort of visualization going on. Last April, Cantu and Castellanos resorted to illustrative technique for the rest of the story of Baldo’s infatuation with Estella. In the first strip, we see the results of Baldo’s courtship: she has turned him down when he asked for a date. But in exhibiting the next two strips, I flash back to the moment she gently rejects him. During this part of the encounter, Castellanos draws the characters realistically: the idea, Cantu once told me, is to heighten the emotional impact by showing the characters to be “real people.” Besides, he said, it gives Castellanos something different to draw. And in the last panel of the last strip on the page, Castellanos takes the “something different” to an extreme: it not only expresses Baldo’s confusion, but the picture is an eye-catcher. Our

final example is another instance of a cartoonist producing eye-catching

imagery.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. Digging around in an old Austrian castle, University of Innsbruck archeologists found four linen bras, carbon-dated to the Middle Ages. Researchers were astounded: the bra has, until now, been commonly thought to be little more than 100 years old. “From all we knew,” the archeologist who made the discovery told the Associated Press, “there was no such thing as a bra-like garment in the fifteenth century.” So the feminine urge to lift and separate is older than we thought. From McClatchy Newspapers: Two miles of concrete barriers. More than 5 miles of 9-foot “anti-scale” steel fence. Nearly 8 miles of light-weight metal barriers and portable vehicle barriers designed to withstand the impact of a 15,000-pound vehicle at 50 mph. According to a federal contract request released recently, these are some of the items the Secret Service is seeking to protect the Democratic National Convention when it meets in Charlotte in early September. The New York Times reports that for every U.S. soldier killed on the battlefield this year, about 25 veterans will commit suicide. About 6,500 veteran suicides are reported every year—more than the total number of soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Here are the names of the actresses who’ve played Catwoman and the dates of their performances: Julie Newmar (on the campy tv “Batman”), 1966; Eartha Kitt, who purred her way into the same series in 1967; Michelle Pfeiffer, “Batman Returns,” 1992; Halle Berry, in “Catwoman” in 2004; and now, Anne Hathaway in this year’s “The Dark Knight Rises.”

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—:

Crime Does Not Pay Archives, Volume 2: Issues 26-29 By Charles Biro et al; Foreword by Greg Rucka 262 7x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardcover, $49.99 FOUR MORE ISSUES OF THE INFAMOUS CRIME COMIC BOOK from Lev Gleason, complete with advertising from 1943 and art by Charles Biro, Norman Mauer, Alan Mandel, Sam Burlockoff, Jack Alderman and Dick Briefer. Issue No. 26 begins with a letter from Gleason himself: he’s in training in the Army Air Corps but wants to assure his faithful readers that “while I am away in the Army of our country, your favorite comic books will be kept at their high level and steadily improved—to suit your taste—by those swell comic artists and editors, Charles Biro and Bob Wood. Well, fellows,” he goes on, “before I get back to work there’s one important thing I want to tell you. All of us in the Army feel confident that we can and will do the big job—we’ll wipe out the Nazis and the Japs for keeps!” In addition to tales of the usual criminal nastiness (Lucky Luciano is taken for a ride, stabbed repeatedly and then tossed out of the car on a lonely country road) told by the spectral Mister Crime, these issues are laden with patriotic wartime messages. At the end of one story, a cute plump fellow recites this ditty: “Said a tailor named Mr. I Pressem, ‘Our soldiers need backing, God bless ’em ... And I’ve bought for their sake, all the bonds I can take—Yes, I’m proud and I’m glad to possess ’em!’” Mauer, one of my favorite artists of the period, has yet to develop his distinctive style, but he and Briefer are thoroughly competent companions for the others who drew these stories. The art has all been Theakstonized and reconstructed, but the styles involved survive handsomely, and although re-colored, the paper is matt-finish, without glare, so the pages don’t appear garish as they say often do in projects employing this method of reprinting.

Superman Versus the Ku Klux Clan: The True Story of How the Iconic Superhero Battled the Men of Hate By Rick Bowers 160 6x9-inch pages, mostly text with a few b/w photographs and 4 pages of color; National Geographic hardcover, $16.95 AND Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero By Larry Tye 428 6x9-inch pages, all text except for a 16-page section of color photos; Random House hardcover, $27 RADIO’S SUPERMAN took on the Ku Klux Klan in sixteen episodes in the summer of 1946, and Bowers outlines the story as broadcast and also tells the story behind the story, but the confrontation of the book’s title takes only the last 25 pages of the book; the rest of this slender volume, aimed at young adult readers, is devoted to rehearsing the history of Superman’s creation, the formation of the KKK in the years after the Civil War, and the biographies of William J. Simmons, who, with publicity mavens Bessie Tyler and Edward Young Clarke, revived the Klan in the 1920s, and Robert Maxwell Joffe, who, as pulp writer Bob Maxwell, produced the radio program and used information collected by Stetson Kennedy, an anti-bigotry crusader who had infiltrated the Klan in order to expose it. Unhappily for his credibility, Bowers skims over some of his histories, leaving us to wonder how thoroughly he did his research. In tracing the lives and careers of Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, he fails to mention Malcolm Nicholson-Wheeler, the man who published the comic books in which the youths’ other creations appeared—including Action Comics No.1 (cover-dated June 1938), where Superman eventually debuted. For Bowers, DC Comics (or National Allied Publications) was all Harry Donenfeld, bootlegger and porn peddler, and Max Gaines, scrapping syndicate salesman and would-be publisher. And the Klan was formed as a joke, he alleges, admitting at the same time that the joke-birth is but one of several origin stories. In somewhat the same casual if not outright wrong-headed way, Bowers admits that Kennedy’s connection to Superman’s battle with the KKK is disputed, and in the same spirit of candor, he allows as how the radio Man of Steel’s battle against the Klan was not, single-handedly, responsible for the KKK’s failure to revive itself again in the 1940s. Among the other sideshows Bowers illuminates is how the Nazis during World War II regarded Superman, who frequently battled them on the homefront. That Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels “exploded” in rage over the anti-Nazi exploits of the Man of Steel Bowers avers is “almost certainly exaggerated if not outright false.” But the weekly newspaper of the Nazi Secret Service denounced Superman: “In April 1940, the paper ran the proclamation ‘Superman ist ein Jude!’ (Superman is a Jew!”) The sarcastic, mocking piece referred to Superman’s primary creator as Jerry ‘Israel’ Siegel and accused him of sowing hate, suspicion, evil, laziness, and criminality in young hearts”: “Jerry Siegel, an intellectually and physically circumcised chap who has his headquarters in New York, is the inventor of a colorful figure with an impressive appearance, a powerful body and a red swim suit who enjoys the ability to fly through the ether. The inventive Israelite named this pleasant guy with an overdeveloped body and underdeveloped mind ‘Superman.’ He advertised widely Superman’s sense of justice, well-suited for imitation by the American youth. As you can see, there is nothing the Sadducees [an ancient Jewish sect] won’t do for money! Jerry Siegellack stinks. Woe to the American youth who must live in such a poisonous environment and don’t even notice the poison they are swallowing daily.” Takes a poisoner to allege another, I suppose. Bowers believes that Superman incorporates aspects of Jewish culture, but he, like so many (including Larry Tye) who see Moses in the bullrushes in Kal-El’s arrival in a space capsule from Krypton, he overlooks the otherwise obvious fact that the Old Testament’s Moses story is part of the Christian Bible as well as the Jewish Torah (the first five books of the Old Testament and, sometimes, all 24 books of it). Superman the Moses stand-in is therefore both Christian and Jewish, a manifestation of the Judeo-Christian tradition in Western culture. No matter: it’s a trivial demurer. No one can deny that Siegel and Shuster were Jews; and no one is seeking to in this venue. Moreover, both Bowers and Tye see a Christian element in the Superman mythology: Kal-El’s father sends his son to Earth to save it. Jesus in blue tights. A sociologist who views religions as social phenomena rather than as matters of faith might view Superman not so much as a reflection of Judaism or Christianity but, instead, see all three as reflecting a basic human need to escape responsibility for our lives, to worship (admire and fear) something more powerful than ourselves in an effort to comprehend an otherwise inexplicable fate. Superman, in short, grows out of the same fundamental need that also fosters religion.. Tye’s book provides an overview of Superman’s history as an entertainment icon. Tye traces the character’s evolution through comics to radio to television and to blockbuster movies, supplying mini-bios of the various entrepreneurs and performers who have participated in the creation of the vehicles by which Superman took possession of popular imagination. In this tome, Major Malcolm Nicholson-Wheeler briefly takes center stage: Tye incorporates into the usual myth of Superman’s initial publication the testimony of the Major’s son, Douglas, who maintained (first in Alter Ego No. 88) that his father recognized Superman’s appeal and planned as early as the fall of 1937 to use the character to launch his newest comic book, Action Comics. Superman’s appearance in that title’s first issue (June 1938) was scarcely fortuitous despite the tradition that Shelly Mayer was the first to recognize the merit of Superman or that Vincent Sullvan, editor of Action Comics, was nearly the first. The Major was ahead of them both, it seems. (Or maybe he wasn’t: maybe Superman went from Mayer to Sullivan, as is the customary handoff, and then to Wheeler-Nicholson—the relay occurring several months earlier than tradition has it.) Tye tries to integrate these various traditions, mentioning Max Gaines and Harry Donenfeld as pivotal: Donenfeld was looking for material for the first issue of Action Comics, which he’d just bought from the Major, and asked Gaines if he had anything at hand. Presto, up-up-and-away with Superman. But Tye doesn’t explain how Siegel and Shuster initially found the Major to publish some of their earlier creations (Doctor Occult and Henri Duval). And he leaves the Major dangling after he promised the youths to publish their Superman. Did Donenfeld phone Gaines to get more material for Action Comics No.1? Or did he inherit Superman from the Major when he bought all the Major’s comic book titles? The latter seems more likely to me, but Tye prefers the former, probably as a result of wanting to incorporate into one narrative the variant threads of the numerous traditions associated with the birth of Superman (many of which are more myth than fact). Tye also accepts the idea that it was the death of Spiegel’s father during a robbery of his store that inspired his son Jerry to create a “protector” of super-dimensions. I think the connection between these two events has been previously disproved. Beyond re-telling the creation story and the publication debut story, Tye adds numerous other tales about the evolution of Superman as a commercial entity, and none of these have been adequately explored before. I haven’t finished the book, but it promises to be engaging if not highly informative as well, and I look forward to reading the rest of it.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |