|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 295 (July 2, 2012). To kick off Open Access Month here at Rancid Raves, we have a brief report on the roaring success of Denver’s First Comic-Con (held June 15-17) plus, in honor of the possible resumption of Occupy efforts this summer (a vain hope, alas), a long review of Che, a graphic novelization of the icon’s life by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon, plus shorter essays on the end of Life in Hell, some of the best editoons of the past month, and reviews of numerous new books on comics and some funnybooks: Allan Holtz’s Encyclopedic American Newspaper Comics Guide, Health Care Reform, Sunday Funnies, Best of the Three Stooges Comicbooks, Adventures Into the Unknown: Pre-code Horror Anthology, Crime Does Not Pay, Issues 1-4, Jim Henson’s Tale of Sand, Boody: The Bizarre Comics of Boody Rogers, The Revolutionary Icon: Che; and a handful of funnybooks—Minutemen, Dan the Unharmable, Fury Max, Powers, Super Crooks, All Star Western, Bad Medicine, The Spider. And farewell to Ray Bradbury (with an emphasis on his engagement in comics and the Sandy Eggo Con), LeRoy Neiman (and the Femlin), and Herman’s Jim Unger. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Wimpy Kid Inspired by Big Nate Bagley Gets Mayor’s Award Times-Picayune To Print Only Thrice Weekly Steve Kelley Laid Off in October Life in Hell Ends

DENVER COMIC-CON A BIG SUCCESS

Ed Stein Hangs Up Editooning

EDITOONERY Comments on Supremes Upholding Obamacare Some of the Best of the Month

Gossip & Garrulities Gaiety Rancid Raves Gallery Rozanski’s Ink

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Garfield Anniversary Funky Anniversary Memorial Day Strips Outrageousness

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST Zuma Gets Cocky

BOOK MARQUEE Allan Holtz’s Encyclopedic American Newspaper Comics Guide Health Care Reform Sunday Funnies Best of the Three Stooges Comicbooks Adventures Into the Unknown: Pre-code Horror Anthology Crime Does Not Pay, Issues 1-4 Jim Henson’s Tale of Sand

BOOK REVIEWS Boody: The Bizarre Comics of Boody Rogers The Revolutionary Icon: Che

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Minutemen Dan the Unharmable

Fury Max Powers Super Crooks All Star Western Bad Medicine The Spider

PASSIN’ THROUGH Ray Bradbury and the Comic-Con LeRoy Neiman and the Femlin Jim Unger

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Parade for May 27 had no cartoons in it; June 3, one cartoon; June 10, two; and two again on the 17th and the 24th. We may have a rhythm here. Then, three—THREE!—in the July 1 issue. ... “The Avengers,” having raked in $207 million, may set a world record for a movie opening. ... X-O Manowar, the first of the new Valiant line to hit the newsstands, finished in 40th place in the top 300 in sales for May, a good sign. ... I neglected to mention in my report on the National Cartoonists Society’s Reubens weekend in Las Vegas that attendance was 335, including wives, children and friends as well as 161 NCS members, less than last year’s bash in Boston, we were told; NCS membership totals 514, of which 369 are “regular” members (who earn their livings mostly by cartooning). Lincoln Pierce’s Big Nate books reprint some of his comic strip by that name in addition to offering new material, mostly prose. The books are obviously aping Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid tomes: they even display strips drawn by sixth-grader Nate on lined paper, hallmark of the Wimpy works. But it turns out Pierce has an earlier association with Kinney: the latter wrote Pierce a fan letter when he was a student at University of Maryland 20 years ago. “We had gotten to know each other,” said Pierce, “and he introduced me to some publishing house and helped me get my foot in the door.” So who’s imitating whom? Looks like Kinney was inspired by Pierce—lined paper and all—not, as I’d supposed, the other way around. Every year the Salt Lake City Mayor's Office awards individuals and organizations who have made significant contributions to the artistic landscape of the community. This year, on June 22, The Utah Arts Festival and Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker presented the Mayor's Artist Award to editorial cartoonist Pat Bagley, who, for 33 years, has cartooned at the Salt Lake Tribune. Winner of the 2009 Herblock Award, Bagley is syndicated through CagleCartoons. He was born in Salt Lake City but raised in Oceanside, California where his father worked in city government (probable source of the cartoonist’s canny insight into modern-day chicanery—er, politics). Bagley served a Latter Day Saints mission to Bolivia and later cut his teeth on cartooning at Brigham Young University’s campus newspaper, the Daily Universe. He currently describes himself as "Mormon Emeritus." When I interviewed him in the 1990s, he said he was a “lapsed Mormon,” but when I asked him last month about that designation, he said he preferred Mormon Emeritus because it had “a ring to it.”

BAD NEWS ALL AROUND FOR PRINT JOURNALISM And for Editoonist Steve Kelley The New Orleans Times-Picayune announced in mid-June that starting in the fall, it will publish a print version only three days a week, resorting to the Web for daily news coverage, as will other Advance Publications newspapers in Birmingham, Huntsville and Mobile, Alabama. Steve Kelley, editoonist at the Times-Picayune since 2002, is one of 600 people in New Orleans and Alabama to be laid off by Advance. “I used to joke with people that for a political cartoonist, living in New Orleans represented job security,” Kelley said via e-mail to Rob Tornoe at Editor & Publisher. “Okay, so I was wrong.” Kelley will remain on staff until October 1, when the Times-Picayune begins its new print schedule. He will continue drawing his nationally-syndicated editoons for Creators Syndicate, and he will also continue to write Dustin, the syndicated comic strip about an unemployed college grad moving back home with his parents. The strip, exquisitely drawn by Jeff Parker, editoonist at Florida Today, was concocted by Kelley several years ago and is now in over 320 newspapers. “In the face of losing his perch as New Orleans’ cartoonist, Kelley remains remarkably understanding of the tough decisions management has been forced to make,” Tornoe marveled. “I look at the Times-Picayune’s decisions as their business. It must be very difficult to lay off scores of excellent journalists, and I can’t imagine they would do so without reason,” Kelley remarked. “That said, I would have encouraged the paper to transition away from print editions more gradually.” Moreover, Kelley told the Washington Post’s Michael Cavna, the move into the digital ether may not be the best move for newspaper journalism. “I just think you’ll end up with collateral damage. In a sense, you’re training people out of the habit of newspaper reading. … Once we teach people that they didn’t need their Monday paper and their Tuesday paper, they’ll start to ask themselves whether they need their Wednesday paper, too.” Kelley relocated to New Orleans in 2002 to take the Times-Picayune cartoonist slot vacated by Pulitzer Prize winning editoonist Walt Handelsman. Kelley was fired from his first cartooning job at the San Diego Union-Tribune, after 20 years, when editors accused him of sneaking a cartoon into the paper featuring the exposed butt cracks of several teens wearing baggy, low-riding jeans. Kelley, who I count as a friend, has maintained that the episode was the result of misunderstanding, and his recitation of the events leading to his firing has convinced me that he is correct. It’s also likely that his dismissal was at least in part over his “right of center” political philosophy. (Visit Opus 62 for all the sordid details.) Kelly has won many awards over his long cartooning career, including the National Journalism Award from The Scripps-Howard Foundation and the National Headliner Award. “He’s a really fine cartoonist, and he’s been great to work with,” a shaken Terri Troncale, the Time-Picayune’s editorial page editor, told Tornoe. “Cartoons are very important, and I’m sad he’s not going to be here to work with.” “The paper can get by without locally-produced cartoons, I suppose, but what if our former mayor is indicted?” asks Kelley. “What if the Saints go on another championship run? What if there’s a hurricane? Like a pistol in the nightstand, it’s good to know the political cartoonist is there when needed.”

HELL ENDS Matt Groening’s idiotically long-lived weekly comic strip, Life in Hell, finally ended: after 1,669 installments over 34 years, the release for June 15 was the last. "I've had great fun, in a Sisyphean kind of way," Groening said in an e-mail to the Web site Poynter.org, "but the time has come to let Binky and Sheba and Bongo and Akbar and Jeff take some time off." The visually diluted cartoon that introduced the aforementioned characters – three bucktoothed, anthropomorphic rabbits and a fez-wearing gay couple – first appeared in Wet Magazine in 1978, moving to L.A. Weekly and then the L.A. Reader to spread the toxic infection of Groening's sardonic perspectives on childhood, dating, family and rock-music criticism. “Life in Hell prevented me from doing other projects,” Groening told Jefferson Graham at USA Today, “—because the comic strip kept me tethered to the drawing table every week, and it will be nice to see what happens without it. Quitting will open me up to new things, more animation, more stuff. I may just sit and stare into space.” “In a telling tale of the times,” Graham continued, “Groening not only wasn't getting rich off the comic (papers paid just $18 a week for the strip), but he also was losing money on it for 10 years, says Sondra Gatewood of ACME Features, Life in Hell's syndicator. At its height, Life in Hell was distributed to 379 newspapers, she says. Now it's down to just 38. The final strip ran June 15, but reruns will continue through July 13.” Why pull the plug on Life in Hell now? asked Richard Gehr at Rolling Stone. Did you simply run out of jokes? “It's pretty obvious that I ran out of jokes a couple of decades ago,” Groening laughed, “—but that doesn't stop any cartoonist!” But Gehr persisted: “Seriously, though, what drove you to keep drawing it week after week for all those years?” Said Groening: “When I started doing the comic strip, it was a great forum for all of my creativity. I'd think about the comic strip all week, spend a day drawing it, and then start thinking about the next one. It was my complete and total focus. Then ‘The Simpsons’ came along to preoccupy me, and I decided to see how long I could keep the comic strip going. Actually, a tv producer sneered at the strip and said, ‘Why do you bother? Give it up.’ Because of that, I dug in my heels and kept it going two decades longer than I might have. I also liked the idea of having one slice of my creative output being completely solo, unlike tv animation. It's very satisfying to sit down at a drawing table by yourself and solve a puzzle with a deadline.” Groening remembers fondly the time he thought he was famous. “I was walking down Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles with Gary Panter one day, and both of us were thrilled when we saw our strips soaking in the gutter. We were part of the landscape!” Groening, like many cartoonists of his generation, says Charles Schulz’s Peanuts was his initial inspiration: “It was a strip about neurotic turmoil that was drawn very simply,” he told Rolling Stone’s Gehr. “As astute followers of Life in Hell will notice, Akbar and Jeff wear the same striped T-shirt as Charlie Brown. Peanuts was very important to me. I remember one comic in which Lucy makes a row of sand sculptures with her bucket and then stomps each one in succession. She looks at Charlie Brown and says, ‘I am torn between the desire to create and the desire to destroy.’ As a kid I thought, ‘That's me! I can relate!’” In his 1990 anthology, The Big Book of Hell, Groening elaborated along those lines: “All my life I’ve been torn between frivolity and despair, between the desire to amuse and the desire to annoy, between dread-filled insomnia and a sense of my own goofiness. Just like you. I worry about love and sex and work and suffering and injustice and death, but I also dig drawing bulgy-eyed rabbits with tragic overbites. Hence, Life in Hell, an ongoing series of self-help cartoons—the self being helped being me.” Beyond Schulz, there were other inspirations, Groening admits. “There's also Jules Feiffer, because he was able to do a weekly comic strip in the Village Voice as well as books and screenplays and everything else. He was a great role model. And then of course my former Evergreen State College classmate Lynda Barry, whose Ernie Pook's Comeek didn't treat the comic strip like old-time vaudeville. It wasn't setup, setup, punch line. She's an under-acknowledged pioneer of a lot of things people are doing in graphic novels and graphic memoirs.” Life in Hell, as everyone reading this knows (or should), is responsible for “The Simpsons,” Glen Weldon reminds us on npr: “In 1985, producer James L. Brooks asked Groening if he wanted to turn his scribbly, scathingly satiric strip starring anthropomorphic rabbits with overbites and existential dread into a series of animated shorts to be featured on ‘The Tracey Ullman Show.’ Groening, wisely, knew that doing so would relinquish his ownership of the characters, and pitched a series of cartoons based on his own family instead: keep the overbites, the dread, the satiric impulse, but lose the rabbit ears and add a bit more heart (Brooks' influence).” “How did you wrap it all up?” Gehr asked. “What happens in the final Life in Hell?” Groening said: “Binky says to his girlfriend, ‘Just once I want to hear the three sweetest little words in life come from your lips.’ She says, ‘I forgive you.’ And he says, ‘Close enough!’" In the corner of your eye are manifestations of the strip—a recent one compared to three from the 1980s, when it was still funny. Can you pick out the most recent?

This selection, culled, mostly, from that 1990 anthology, includes what I believe to be the arrival of Bongo, the one-eared offspring.

FIRST DenComCon ROARS TO SUCCESS The first Denver Comic-Con, June 15-17, was, from my point of view, a huge success. My point of view? Cartoonist, comics chronicler and one-time convention manager. Over the last 10 months, I’ve been meeting off-and-on with the planners of the Con, giving them the dubious benefit of my vast past experience (30 years doing 4-5 conventions a year). Turns out, they needed no advice from me: they have among themselves all the genius, talent and skill necessary for throwing a bang-up show. Inaugural events such as this are expected to come with a few glitches and organizational hoe-downs, but not this one: it looked and felt like dozens of other comic-cons I’ve attended over the years—and that’s a compliment; that is, the Denver Comic-Con worked like a con put on by professionals who’d been producing it for half-a-dozen or more years. They may have been first-timers, but there was absolutely no evidence of that. The Denver Convention Center’s second-floor exhibit hall was festooned with booths selling comic books, games, toys, costumes, and everything else the Sandy Eggo Con has taught us to expect, plus lots of distinctive touches—aisle markers and unique overhead banners, a rock band playing almost all the time, vintage tv-series automobiles on the floor (attending professionals were invited to draw pictures on one), spacious and extensive Artists Alley, Con souvenirs and merchandise, a knowledgeable volunteer army in red t-shirt uniform, and, even, Golden Age comic books. Just inside the door was the Comic Books in the Classroom “corral” where kids could assemble at tables and draw pictures and make comic books of their own. The Con raised money for the CBC, a free non-profit after school program for fourth- and fifth-grade students that enhances literacy and teaches art using comic books and graphic novels as teaching tools. By the end of the six-week program, created for schools in socio-economically challenged neighborhoods, the kids have written and designed their own comic books. Said Frank Romero, president and co-founder of CBC and one of the honchos of the Con: “Kids learn how to create characters, form a plot, layout a page and create a comic. They learn how a story is put together and how pictures can enhance what the story is trying to tell the reader. Along the way, students learn that they have a voice. They can use that voice to tell any kind of story they wish. That is their superpower, and it is an extremely powerful ability. “There would be no reason to do the Con without a charitable component,” Romero went on, talking to John Wenzel at the Denver Post. “For me, it’s really integral that the literacy portion is pretty front and center.” “So,” Wenzel continued the story, “when Romero and life-long friend [cartoonist] Charlie La Greca started batting around the idea for the Denver Comic-Con three years ago in La Greca’s parents’ basement—surrounded, appropriately, by hundreds of comic books—they knew it had to serve a higher purpose than simply letting nerds gather and play.” “What we also offer,” said co-founder La Greca, “is that we’re really pulling that comic book culture out of the back room of those other fests and cons, where they’re subjected to a smaller area, and we’re making that the main event.” Which explains, in part, why the Artists Alley at DenComCon was almost equal in square footage to the booth display area. Presentations on aspects of comics art and popular culture entertainment went on in meeting rooms a floor below the exhibit. Across the street in the host hotel, gaming transpired, and films were screened. The preamble to the Con, arranged by Christina Angel, was a two-day conference of academics discussing comics; it went off without a hitch, lending a literary patina to subsequent events. Scott McCloud gave a rousing concluding speech, demonstrating once again his impressive command of modes of presentation from a stage. The registration desk for the Con opened at 4 p.m. on Friday; the line of the preregistered stretched out into the street and down the block, but in a hour, the line was gone. The registration system, augmented by computer, of course, sped everyone on the way. Grand total attendance, 27,000. Typically, the Con had a star-studded guest list from television, film, comics, and animation. Of film and television fame were such stars as James Marsters from “Buffy The Vampire Slayer,” Kristin Bauer from “True Blood,” Colin Ferguson from “Eureka,” Jasika Nicole from “Fringe,” and Bruce Boxleitner and Cindy Morgan from the movie “Tron.” Of comic book fame were such artists as Jason Aaron, Michael Allred, Laura Allred, Mike Baron, and Greg Guler. Among the animation guests were Billy West from “Futurama” and “Ren & Stimpy,” Tom Kane from “Star Wars: The Clone Wars,” “Wolverine,” and “X-Men,” Greg Weisman of “Gargoyles” fame and Colorado’s own Steven Seagle. Throughout, teaming multitudes of cosplayers thronged and paraded, costumed like favorite tv and movie characters. Among the usual Star Wars storm troopers, Klingons and zombies, one guy appeared in a huge white fuzz-ball, and when I asked him who (or what) he was, he said: “Sasquatch with shaved legs.” Bada-boom. A young woman endowed for the part wore a Power Girl costume one day. The next, she had on a red wig but a different costume albeit with an equally spectacular neckline. After studying the prospect for a while, I asked her if she’d been Power Girl the day before, and she said she had. “I thought so,” I said, “—I recognized parts of you.” Bada-boom. Sexist? Of course. But if she hadn’t wanted the recognition, she wouldn’t have worn Power Girl’s outfit.

GAIL SIMONE REACTED HAPPILY to the festivities at 606Studios.com: “Boy, am I glad I came. This is the first year of this convention, Denver has apparently never had a real comic convention of any size before. Being a first convention, there are always concerns about attendance and organization. Sheesh, both Friday and Saturday completely sold out, the place was packed. There are tons of interesting guests, lots of great panels, and a real emphasis on diversity. The attendees included huge percentages of females, there's more cosplayers here than any con this size I have been to, and very welcome indeed, there are lots and lots of kids. “The attendees here are magnificent, hugely diverse. Lots and lots of poc attendees and creators, and the welcome from the local lgbt geek community has been very very wonderful, very moving. Lots of dads with their kids, lots of MOMS with their kids, every kind of person has come to my table, and it's really overwhelming to see how the readership is stronger and more committed than ever. Some of the kind, personal things people have said to me here, I will remember forever. “TONS of Batgirl love. I lost count of the Batgirl shirts and cosplayers. And it's surprising how many people are responding to the compassion and social issues raised in the book. As always, trauma survivors often tell their stories, and it means a lot to them to see that reflected in a major superhero book. Lovely. Very emotional. I don't always have the proper words to respond to some of the kinder things, so please just know that it means the world to me.” After doing a panel for DC/Vertigo, Simone was on the panel “at one of the best lgbt panels I have ever been on. I was not familiar with most of the panelists but they were absolutely fascinating and sincere, and it was very moving. The audience was amazing, lively and smart. A RIDICULOUSLY handsome African American gentleman in the audience got the biggest hand of the night when he brought up interesectionality [maybe a typo? “intersexuality”?—RCH], in a roundabout but very moving way. He said he had watched as the portrayals of black people in comics had improved from the jive-talking characters to genuine heroes he could root for, and he felt that was happening in comics with lgbt characters. I wanted to cheer also, such a great moment. “Panels like that, I am delighted just to sit back and listen. It's an honor just to be there at all. ... Great, great con so far. THANK YOU for making this Oregon girl feel so welcome, Denver!

ON THE LAST AFTERNOON, it was announced over the loud-speaker system in the exhibit hall that Stan Lee had confirmed to be a guest at next year’s Denver Comic-Con. And so this year’s achievement was crowned by anticipation of even greater dazzle for next year. Incidentally, the giant blue bear on the cover of the Con program is inspired by the giant blue bear that stands outside the Denver Convention Center, peering into the building. Inside, he saw me at my table in artists alley, trying to sell caricatures and books. Here are some other glimpses of the festive weekend.

STEIN CALLS IT QUITS ON EDITOONING For the last couple of years, Ed Stein has been producing a daily syndicated comic strip, Freshly Squeezed, about three generations of a family living together because the senior couple’s home was foreclosed on, but Stein began his cartooning career as an editorial cartoonist, spending most of it at Denver’s Rocky Mountain News, and he just gave up what remains of that endeavor. When the Rocky folded in 2009, Stein continued editooning through syndication with Cagle Cartoons. But that proved unsatisfying. Stein told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs that he’d been thinking about retiring for months “for several reasons,” he said: “I just wasn't enjoying it anymore. The passion was gone. Not having a newspaper and a local readership was part of it, and the workload of a daily comic strip plus editorial cartoons was another factor. The toxic political atmosphere certainly contributed, as well. It seemed that what I was doing was increasingly irrelevant, given today's political climate and the declining impact of newspapers. One of the reasons I decided to hang it up is that I no longer have that feedback loop with the readers, and drawing only for syndication isn't nearly as satisfying. Even the hate mail isn't as intimate and personal.” Stein is grateful for the three decades he cartooned at the Rocky: “The Rocky gave me a fabulous soapbox — a big daily newspaper with a statewide reach. I had supportive editors who trusted me and let me do my work without interference and who let me experiment. I always thought of the job as an ongoing conversation with readers, and I think I developed a genuine rapport with the readers of the Rocky, especially after I started Denver Square, my daily comic strip about life in Denver.” Stein is fairly glum about the future of editorial cartooning. “I wish I had any idea where editorial cartooning might find its salvation, now that newspapers are dying. My career spanned the arc from the great rise in editorial cartooning during Watergate and Vietnam to the virtual extinction of the newspaper cartoonist. Yes, there still are a handful of cartoonists doing important, original work, but much of what I see now is uninspired, repetitive and dull. The alties seem to have the energy, and some of them are doing genuinely original stuff, but their circulation is so marginal they don't have much impact. The web gives us an unlimited potential audience, but the reality is that it's so fragmented it's almost impossible to build an audience comparable to what a big newspaper used to provide—not to mention the question of how to make a living without an employer.” Stein’s advice to wannabe editoonists? “Run! Throw that pen away and go to bartender school. I have no idea how to make a living as an editorial cartoonist now. I think it's up to the next generation to figure out. The only real advice I have is to perfect your craft and assume a market will find you if you're good enough at what you do. If cartooning is your calling, then know what you're about and why you're doing this. “Having a political philosophy and point of view isn't enough,” he continued. “Don't illustrate the news. Draw about the issues behind the events, not the events themselves. Advocate for people, not politicians. Don't be an unpaid huckster for a political party. Resist the temptation to support their daily talking points. Constantly question your own motivation. Do your research. Know the facts and avoid the spin. Admit it when you're wrong. Don't be lazy; don't do what everyone else is doing. Support ideas, not ideologies. Say something in every cartoon; make every drawing count. And I could go on.” But he won’t. Not at editorial cartooning. He’ll continue his comic strip, though. “Being able to concentrate on it will give me a chance to improve it and build it,” he said, hopefully. “And I do have a number of new projects in mind. I don't know yet which ones I'll work on first.”

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

PERSIFLAGE AND BAGATELLES In a recent issue of The New Yorker (April 23), Anthony Lane reviewed “Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope,” the new Morgan Spurlock film, saying “the best thing about it is that it will save you from going to Comic-Con. If you have, like me, felt a secret squirm of curiosity about this event—a vast annual splurge of pop culture—then Spurlock’s documentary will tell you how, and whether, you should join the pilgrimage. Because I have never watched ‘Battlestar Galactica’ and because of my absurd reluctance to dress up as Wonder Woman, I wouldn’t last five minutes. ... What regulars love about Comic-Con amid the depictions of interspecies mayhem is the warm sensation of being in a comfort zone.” Joss Whedon, Harry Knowles (who founded the website Ain’t It Cool News) and Stan Lee are interviewed on camera, Lane reports. “All three gentlemen are in good humor, as well they might be, since they are executive producers of the film. Indeed, the whole thing is so incestuous, like an episode of ‘The Borgias,’ that you soon forget the existence of a galaxy beyond San Diego. ... All negative remarks are shunted into the closing credits, and even then, the harshest gibe is that the atmosphere at Comic-Con—not the mood but the stuff you breathe on the floor of the convention—is, let us say, memorably aromatic. One guy says that, being tall, he is ‘above the stinkline.’ “What Comic-Con requires,” Lane concludes, “is neither fan nor foe but an anthropologist, someone who could discover why an adult human male would wait in line two days for ‘an eighteen-inch Galactus,’ which sounds like something you buy online under a pseudonym. Then, there are the obvious questions: Do Comic-Conners vote? Does Ron Paul ever swing by? Do they have sex, and, if so, do they keep their outfits on? Does crime go up or down in San Diego during convention week? How about drunkenness—are the jail cells full of sobbing Princess Leias and vomiting Batmen? This movie was our chance to find out; now we’ll never know.” But you might pick up a clue at the Con itself—this year, July 12-15. See you there? I’m on a couple panels (nothing sensational, alas), but the rest of the time, I’m wandering. Unless I’m resting at the booth of the National Cartoonists Society.

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted

When in danger, when in doubt, Run in circles, scream and shout.

AS I WRITE

THIS, we’re only two days into the wake of the Supreme Court decision on

Obamacare, so editoonists haven’t had long to cobble up reactions. Still, the

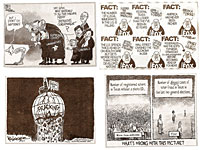

culling at hand seems to run the gamut of possibilities. Jeff Darcy, next around the clock clockwise, explains why Roberts jumped over to the so-called “liberal” side of the Court. Apart from the row of rubber stamps on the right (a regimental line-up that conveys part of Darcy’s message), the point is made verbally rather than pictorially. And columnist Charles Krauthammer said much the same (at greater length, of course): “Roberts is Chief Justice and sees himself as uniquely entrusted with the custodianship of the Court’s legitimacy, reputation and stature.” And a few decisions of recent years—notably the Bush vs. Gore decision that won the White House for GeeDubya, then the Citizens United case—have tarnished somewhat the reputation of the Court. Roberts didn’t want the Roberts Court to go down in history as the political handmaiden of the Republican Party as these two decisions seemingly branded it. Krauthammer continues: “Roberts’ concern was that the Court do everything it could to avoid being seen, rightly or wrongly, as high-handedly overturning sweeping legislation passed by both houses of Congress and signed by the president.” And so he contrived a masterful decision that cowtowed to the conservatives by denying Commerce Clause imperialism to Congress on the one hand but, on the other, recognized the legitimacy of laws created by an elected body. “Result? The law stands, thus obviating any charge that a partisan Court overturned duly passed legislation. ... Law upheld, Supreme Court’s reputation for neutrality maintained. Commerce Clause contained, constitutional principle of enumerated powers reaffirmed.” Only a few pundits last winter foresaw that Roberts might do what he did—act for the Court’s reputation rather than out of some other conviction. Clockwise some more to John Cole, who uses two panels to remind us that Obamacare is really Romneycare. So when Romney rants on, post-Supreme decision, calling Obamacare bad law, he merely exemplifies the hypocrisy that has lately distinguished just about every public action of the GOP. The crowning hypocrisy, of course, is that the most despised part of the Obamacare law—according to Republicons—is the mandate, which is exactly the device the GOP proposed to fund its aborted 1990s health care plan. In fact, many believe Obama included the mandate in order to appeal to Republicans for their support. Now the GOP regards the mandate as government overreach, the onset of Socialism if not an Obama monarchy. Hypocrisy raised to the status of the Big Lie, which, as the Nazis taught us, will be believed if it is repeated often enough. Finally, Pat Olipant takes us beyond the decision itself into the inevitable politics that will ensue. Romney’s drooping axe is wonderfully emblematic, an astute visual metaphor for the ineffectiveness of the Republicon scheme to “repeal” Obamacare by judicial activism. Now what? “Do you have a Plan B?” asks Punk the Oliphant penguin. Just Romney. The Romney plan is simply to get the guy elected and then, single-handedly, he’ll repeal the law. That’s what he said. In the few hours he has off from constructing single-handedly the Keystone pipeline from Canada to the Texas coast (so oil and gas can be exported to other countries), he’ll repeal Obamacare. What are the chances of repeal? Remote to nonexistent. Even if Romney is elected—a highly unlikely possibility—he’d need both chambers of Congress overwhelmingly Republican to repeal Obamacare. The House is already in that balliwick, and it’s conceivable that in the Senate, the Democrats might lose their slim majority. But it’s not likely that the Republicons will get 61 seats in the Senate, the number they’d need to jam through whatever legislation the GOP House passes. Even in a minority in the Senate, the Democrats could consistently block with filibuster threats any Republicon legislative progress, just as the GOP has done so consistently throughout the Obama administration. Why won’t the GOP get 61 seats in the Senate? Because, as Tip O’Neill famously said, “All politics is local.” Entire legions nationally may despise GOP senators—all of them, that is, except “our guy,” the senator elected in your state. Chances are very good that he’ll be re-elected. And that’s true for almost all of the 100 crooks who presently occupy the Senate. So why rant on about repealing Obamacare? Because this Big Lie, like most of the other GOP utterances lately, provides a rallying cry for the demented who flock to the Pachyderm banner. The Republicons keep saying Obamacare is an unpopular law. But it isn’t that unpopular. At focus groups reported post-Supreme, it seems that once people learn that the new law won’t require them to change anything in their present medical coverage, they are virtually indifferent to the law. If the GOP rides this issue up to Election Day, it’ll be entirely for the sake of the hot air being generated by candidates. Poll figures are no more definitive. From 2009 to 2012, those who favor Obamacare number between 30-40%; those opposed, 39-48%. Given the usual plus-or-minus 3%, we have a nearly equal division of public opinion. Polls assessing the anticipated public response to the Supreme decision in the weeks before it was announced divide into thirds, regardless of the decision—one third pleased, one third displeased, and a third third with mixed feelings. Most Americans think health care needs to be reformed, but approval of various proposals has steadily declined since June 2009, when 50% were in favor and 45% opposed; by January 2010, support had dropped to 40% and opposition increased to 55%. The diminishing approval over the years is probably due to the steady pinging of the GOP lies about what Obamacare entails. Even so, Gallup finds that few Americans so far in 2012 mention health care as one of their most pressing concerns. Moreover, only when health care is among the questions asked in surveys do Americans think of it as an important issue. Not that the GOP cares about such facts. They have a program to jam through regardless of facts. Another of their Election Year propaganda assaults is citing Attorney General Eric Holder for contempt of Congress. (If contempt of Congress is illegal, then the authorities are going to have to cite and punish over 80% of the American public. Shesh.) The loony Right thinks it knows what the administration is covering up by not releasing certain of the Justice Department documents on the Fast and Furious fiasco, said editoonist/columnist David Horsey at the Los Angeles Times: Fast and Furious, the Righteous Right insists, was an elaborate White House plot to incite a bloodbath in Mexico so as “to undermine the Second Amendment and take away citizens’ guns.” That’s why the National Rifle Association is calling for Holder’s head: it’s writing down names, too, and those members of Congress who didn’t vote in favor of the contempt citation will run up against NRA opposition in the forthcoming election. No greater political force exists than the NRA. Fear and trembling pervade Congress. Wait a minute. Wait a minute. White House plot? Which White House? Fast and Furious has its origins in a 2005 ATF initiative in Texas that went national in 2006—that is, while a bunch of gun-totin’ politicians were occupying the White House. Were they seeking to undermine the Second Amendment? It doesn’t matter. No fact can deter the Pachyderm juggernaut, once fueled with useful fictions and pointed down the campaign trail. Fictions triumph. Fabrication reigns supreme in the American politics. Facts? Truth? Phooey. Sigh. I’m not sure I can last the year. The only way to survive is to laugh a lot. Fortunately, we have in Congress several hundred of the world’s foremost comedians. Will Rogers famously dubbed them all professional comedians when he was miffed at one of their number disparaging him as just “a professional comedian.” Rogers said he was a mere amateur compared to Congress. They are the real professionals, he said. The difference between them and him, he said, was that when they told a joke, it became law. But we’re lucky, as I said: we not only have a class of clowns to make fun of, we have a profession devoted to leading us in laughing—the nation’s editorial cartoonists, to whom we now turn, again, for the respite of risibility.

EDITORIAL

CARTOONS, skillfully done, provoke thought as well as laughter. As, for

example, in the array nearby of highly effective editorial cartoons, in which

the inky-fingered fraternity has undertaken to understand Mitt Romney, the Ken

doll of plastic plutocrats. Finally, we have Pat Oliphant, another editooner specializing in uproarious silliness, which means the Ken doll candidate is right up his alley. And here, he laughingly demonstrates how apt that assessment is. Despite

what the so-called news media convey to us daily, there are other issues in

America than which of the two presidential candidates has collected the most

money to spend on paving his way to the White House, and in our next exhibit,

we examine a few of those other issues. Next in clockwise order, we come to yet another Bagley cartoon, this one relying upon a sequential heaping up of ludicrousness rather than a single image. The shame, of course, is that the cartoon is portraying a typical conservative posture, all at odds with the facts. Then we come to Nick Anderson’s joyous indictment of the movement to create fraud-free election procedures. He’s talking about Texas because he’s at the Houston Chronicle, but the same kind of statistical refutation applies in every state where the Grand Obstructionist Pachyderm is crusading for stricter voter registration procedures. The GOP is attacking a fiction that they’ve created in order to attack it. For shame. Finally, a favorite of mine, Milt Priggee’s revelation about fracking, or “hydraulic fracturing,” to invoke its official name. This is the procedure of forcing chemically enhanced water deep underground to fracture the rock within which oil and gas are trapped; fracking releases the oil and gas. The issue is alive and well here in Colorado, and opposition is equally engaged (albeit perhaps not as effectively as the oil and gas people, who managed to get Dick Cheney to write environmental regulations that permit the oily and gaseous to do pretty much whatever they want to extract oil and gas and get rich doing it). Fracking is dogged by problems. The residual water and chemical compounds are likely to contaminate the water supplies in the vicinity of the fracking; the air is likewise at risk because of the fumes that are discharged at the fracking site. And, finally—here in Colorado anyhow—where is all the vast quantify of water needed for fracking going to come from? Western states already face water shortages of daunting dimension. (Last week’s Denver Post urged home-owners to water only twice a week. On the prairie side of Denver, where it’s as arid as a desert, that would mean no more lawns. And maybe lawns are a luxury we must forego in a water-starved region. The point is, as I said, where is all the water that frackers need going to come from?) So the sensible question is: why do the fracking? Are we really so desperate for oil and gas that we are willing to risk the quality of drinking water for people and irrigating water for crops? The purity of the air we breathe? The supply of water itself? One hopes not, but Cheney and his bunch are reckless in their pursuit of wealth and power. Meanwhile, as Priggee so aptly puts it, fracking will blow the bottom out of everything.

IN OUR NEXT

EXHIBIT, we have some of the champion editoons of the month.

MOTS & QUOTES Youth is a gift of nature; age is a work of art.—Greeting Card “The world as an art is the play of the Supreme Person reveling in image-making. You may call it maya (illusion) and pretend to disbelieve it; but the great artist, the mayavin, is not hurt. For art is maya, it has no other explanation but that it seems to be what it is.”—Tagore “Silence is the unbearable repartee.”—G.K. Chesterton

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing Gaiety is breaking out all over. It must be the year for it. Not long ago, Kevin showed up in Archie Comics, and last month, The Big News in four-color frolics was that the Green Lantern is gay. Not “the” Green Lantern, mind you, but the Earth 2 Green Lantern. This is Alan Scott, who, in a previous incarnation, was married and had a child. Not that such a pre-existing condition would prevent his being gay. And over at Marvel, Northstar married his long-time boyfriend. Then, to top off the month’s gay tsunami, Entertainment Weekly’s June 29 cover story is about all sorts of Hollywood types being gay—and six of them are pictured on the cover. The point of the story within is that celebrity gays are finding low-key ways of revealing their sexual orientation. No big cover stories, in other words. Except at EW. My all-time favorite coming out story took place on Ellen DeGeneres’s “Ellen” tv show. Ellen is at the airport for some reason, and for another reason equally lost in the dim recesses of the Harv brain pan, she has to tell a clerk behind the counter that she’s gay. But she doesn’t want to make a big deal about it, so she, in effect, murmurs the Big Reveal to the clerk. Alas, she does this when her mouth is right next to the microphone for the airport’s public address system; she doesn’t realize that the mic is “on,” so “I’m gay” goes out in at several hundred decibels to all and sundry. Wonderful. Beautifully satirical. All the more so these days.

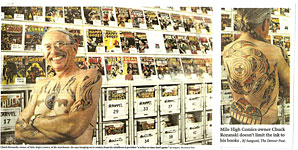

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words

But, heart cracked and/or shattered, he’ll still buy those collections and then sell ’em. Asked why many people prefer print comics to online comics, Rozanski said: “With comics, the tangible has a gratifying aspect. If I want to read my 1950s Disney comics, there’s no way I’d want to read them on my iPad or Kindle. I want to hold them. There’s a sense of ownership. You enjoy the linear progression as a collection. To actually hold an issue in your hand, and know it’s one of less than 100 surviving comics in the entire world? Well, that’s pretty special.”

PERSIFLAGE & FURBELOWS Maggie Roswell, Denver resident for the last 17 years, was the voice of Maude Flanders when “The Simpsons” began 24 years ago. Since Maude was killed off by a t-shirt cannon, Roswell has voiced Helen Lovejoy, Miss Hoover, Luann Van Houten and others. Said Roswell: “I used to fly into L.A. on Thursday and fly back that night, and do that on Monday again. It was getting to be too much, too expensive, they wouldn’t give me a raise, so I quit on the 10th year. Then they killed my character, Maude Flanders. The cast was as shocked about my death as I was. Then I came back on the 13th year. Now we do a phone patch to L.A. I do it from home, and I could not be more grateful. We work from march until November, two weeks on, one week off. I get SAG insurance. It’s great. I am living the life.”

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Jim Davis’ Garfield, starring in

the world’s most ubiquitous comic strip (reportedly in nearly 2,400

newspapers), celebrated his 34th “birthday” on June 19, and, as

always of late, the actual anniversary was preceded with a week’s worth of

strips in which the fat orange feline bemoaned his fate as an aging cat. We’ve

produced a few of this year’s crop in the visual aid nearby. This display also

includes the March 24 release (the bottom strip) in which the strip’s enduring

fiction—that Jon does not hear Garfield or actually converse with him,

regardless of what the speech balloons seem to imply—is iterated for all to

see. The rationale for this handy fiction is simple, and wholly realistic:

Garfield, like all household pets, understands his master perfectly; but, like

all pet owners, Jon hasn’t the foggiest notion of what his cat is

thinking/saying. At the very bottom of the page is the “splash” or opening

panel from a Sunday Garfield some weeks ago: I like the boldly casual

rendering of the cat—not to mention the colors and design. Perhaps in celebration of the occasion—although probably not—a Garfield comic book was launched in May, written by veteran Garfield animation scripter Mark Evanier and drawn by Gary Barker, who has been penciling the strip (keeping it “on model,” as he says) for several generations. Davis originally thought the strip would be about Jon Arbuckle, a cartoonist, who owned a fat cat. “But every time I wrote a gag,” Davis said, “the cat took the punchline.” Davis surrendered to the obvious inevitable and re-named the strip for the cat, reported Bill Hutchinson at the New York Daily News. The first newspaper to drop Garfield, the Chicago Sun Times—within just a few months of the strip’s 1978 launch—was bombarded by protesting readers. “I think it was the cat lovers who came to Garfield’s rescue,” said Davis. At the Washington Post, Ben Bradlee, the curmudgeonly pooh-bah of the paper, rejected the strip at first, saying: “I don’t want a strip I can’t drop: you can’t drop an animal strip. I’m not taking it.” He eventually changed his mind.

ANOTHER

ANNIVERSARY is feted in our next exhibit— Funky Winkerbean’s 40th. In

the next exhibit at hand, we have some borderline outrageous strips, beginning

with two Zits releases in which teen pregnancy is the topic. As for Dilbert, one wonders— doesn’t one?— just what the cash cow is manufacturing. Judging from the expression in the second panel and the anatomical analysis in the third, the lucre is of the somewhat filthy sort— merde, in other words. You’d think the Moral Majority would object to that, too—for purely sanitary reasons. I clipped the Funky strip last December because of the name of the “rest home,” Bedside Manor. For that alone, Batiuk deserves an Oscar. Or a Tony. Or a Reuben. And, finally, in the last clipped strip, we learn that cartooner Rob Armstrong is as big a comic book fan as all of us. A comfort to know in these otherwise uncertain daze.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. From the Wall Street Journal (via The Week): the Quaker Oats man has gotten a makeover as part of owner PepsiCo’s efforts to reinvigorate the brand. The new look for “Larry” involves a haircut and the removal of his double chin, plus a new logo shape and color scheme. “We took about five pounds off him,” said a member of the brand’s redesign team, but left “a little sparkle in his eye.”

ZUMA GETS COCKY Fails to Keep Pecker in Pants—Again (and Forever?) The membrum

virilis of Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s fatuous and famously womanizing prez,

has just been immortalized in a painting by Brett Murray: entitled “The Spear,”

the acrylic on canvas portrait depicts Zuma posed like Lenin but with his naked

peter dangling out of his pants. “Obviously, he unzips a lot and is proud of it,” said Mondi Makhanya, also in the Times. “Frankly, our president is a stallion, and his sexual escapades have been public since before his election. During a trial in 2006 when he was accused of raping a friend’s daughter (the sex was ruled consensual and he was acquitted), Zuma treated us all to lurid details of how he was turned on by the woman’s dress and how he made sure to shower after sex because he believed that would protect him fro contracting HIV.” Subsequently, the country’s premier editorial cartoonist, Zapiro, depicted Zuma with a shower faucet protruding from his head. Zapiro has been a thorn in Zuma’s side ever since; for a history of their relationship, visit Opus 241 and 263 (pictures at the latter). Zuma launched a law suit against Zapiro, a practice he is apparently continuing with Murray. “Zuma ought to just laugh it off,” said the Cape Town Cape Times. “That he has chosen to respond with a lawsuit is evidence of a disturbing drift toward authoritarian tendencies—and he has displayed those tendencies before in his battle against Zapiro. More to the point, however, by overreacting, he’s sent half of South Africa to go look at the painting”—which, alas, they can no longer see. ANC supporters of Zuma entered the gallery and defaced the painting, which has now, as a result I should think, been removed. Why, I wonder, would a womanizer like Zuma object to the painting, which portrays his member at a magnificent dimension. Maybe, like most of the male animal, he believes it is actually much larger and is therefore upset by the diminution of his manhood.

READ AND RELISH Jon Stewart: “The systemic nature of congressional elections is so heavily weighted toward the incumbent that even 50 percent outrage isn’t going to make that much of a dent in the incumbency rate. You could literally have the fucking storming of the Bastille—a French Revolution, with people getting decapitated—and their heads would still get re-elected to fucking Congress because of the way it’s gerrymandered. Somehow, their district happens to be all headless people, so they wind up getting in.” “The beginning of wisdom is the fear of the Lord. The next and most urgent counsel is to take stock of reality.”—William F. Buckley, 1964 “From a Buddhist point of view, if you don’t know how to do nothing, you don’t know how to do anything properly or fully.”—Waylon Lewis, The Elephant Journal

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—:

Allan Holtz’s long-awaited tome, American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide, is about to appear from the University of Michigan Press. At 624 pages with over 3,100 color and b/w comic strip illustrations, this book, which I saw in its pre-Michigan state, will be the authoritative source of basic data about newspaper comic strips. Listing over 7,000 different comic strip and cartoon features from American newspapers, Holtz’s book goes well beyond the typical comic strip history books, all of which focus on the most popular features: this book is encyclopedic, all-inclusive, providing detailed information on important but previously overlooked artists and features. The result of more than twenty years of meticulous research, American Newspaper Comics offers a wealth of information, including the start and end dates of features, their format, frequency, creators, and distribution companies. The book has handy cross-indexes and lists book-length compilations of newspaper cartoons and comics. In addition, the book includes a CD with samples of more than 2,000 cartoon features, including some that may be new to even the most ardent fan or collector. I can’t wait to get a copy.

IN A SURPRISINGLY EXTENSIVE USED BOOK STORE in tiny North Platte, Nebraska, I saw a graphic novel entitled: Health Care Reform: What It Is, Why It’s Necessary, How It Works by Jonathan Gruber, drawn by Nathan Schreiber and pubbed by Hill and Wang (2011). Had no time to evaluate the effectiveness of the graphic novelization; can’t say, therefore, how adept Schreiber is at deploying the conventions of comics. But I was (and am) intrigued by the mere fact that the day’s most inflammatory political topic would be given graphic novel treatment. The medium has clearly matured and is now fully mainstream; it’s graduated even beyond the covers of Entertainment Weekly, which superheroes grace regularly these days.

The Sunday Funnies, No. 1 48 22x16-inch pages, color; published by Russ Cochran, $30 THE FIRST TWO issues of Russ Cochran’s nostalgic visit to the excellences of yesteryear’s Sunday newspaper comics is out, and I finally laid hands on the first issue, which, I surmise, is probably typical of what Cochran describes as a quarterly publication. It comes in three sections of 32 giant-sized pages (the size the Sunday funnies used to be). The first page of each section presents an amazing puzzle of a full-page “strip,” Crazy Quilt, that is clearly there for its overwhelming novelty: the “strips” crisscross the page and each other, and where they meet, the stories coincide, too; 4 pages altogether, April 9 and 26, 1914, and May 3 and 10, 1914. In every section these strips appear: Gasoline Alley, October 24, 1920 through May 15, 1921, 30 pages in all (including the arrival of Skeezix on February 20 in the Sunday strip; he showed up on Walt’s doorstep in the dailies, six days before—on Valentine’s Day); Alley Oop, September 9 through December 30, 1934, 17 pages in all (including the celebrated dinosaur scrapbook page at the upper right on each page); Hal Foster’s Tarzan, January 1 through March 19, 1934, 12 pages (Foster’s Tarzan has six-pack abs—I never noticed before!); Fred Harman’s pre-Red Ryder strip, Bronc Peeler, October 7 through December 30, 1934, 14 pages (some continuity; featuring a big cowboy “lore” panel in mid-page, and the blue-ink Uncle Bill strip at the bottom of the page starts November 4); Wee Willie Winkle, August 19 through September 9, 1906, 6 pages (two undated). Eight pages present early George Herriman: 4 Krazy Kat (February 5 through March 5, 1922) and 4 Stumble Inn (December 9 - 30, 1922). And there are four early Dudley Fisher Right Around Home pages (January 15 and 22, February 26, and July 9, all 1939), that peculiar but heart-warming domestic comedy displayed from a bird’s-eye perspective, with all the neighborhood commenting individually on whatever the mischievous Myrtle is up to this week. I am particularly pleased to see a healthy sample of Harman’s Bronc Peeler, which is so far evaded any substantial reprinting; ditto Fisher’s Right Around Home, the unusual perspective of which always fascinated me as a kid, laying on the livingroom floor reading the Sunday funnies every week. The quality of color is somewhat iffy—that is, faded. And uneven. Some strips were originally published with only two or three colors (black and one or two others; and at least one Gasoline Alley uses only blue, red and yellow). I suspect, then, that not much digital alteration has taken place with these pages; they do, however, accurately reflect the quality of their initial publication. The color is better by the 1930s, so Bronc Peeler, Tarzan, and Right Around Home look fairly good. They’re all shot from the initial publication pages, and the yellow-browning of old newsprint shines through. The paper Cochran is using is heavy-duty stuff, not flimsy newsprint; and matt-finish, not garish glossy. These pages will last and last. The second issue reached me just as I was finishing off this Opus. And the color throughout is vastly improved. The Tarzan pages are from the year before those in the first issue of Sunday Funnies (and Tarzan hasn’t developed six-pack abs yet). Cochran has added Buck Rogers pages from 1930 and Connie from 1938 and some pages of Frank King’s Bobby Make-Believe, the Nemo imitation at the Chicago Tribune. Otherwise, he’s continuing Alley Oop, a few more Bronc Peeler, and lots and lots of Gasoline Alley. Truth to tell, I’m getting a little tired of Gasoline Alley Sunday strips: they weren’t all, every one of them, that special. But I realize I’m pretty much alone in this benighted opinion. In all, Sunday Funnies is a fine effort. And Cochran is now offering subscriptions at russcochran.com.

The Best of the Three Stooges Comicbooks: Volume 1 By Norman Mauer and Pete Alvarado 192 7x10-inch pages, color; Papercutz hardcover, $19.99 NORMAN MAUER was one of my favorite cartoonists as I was growing up and “apprenticing” at the craft by copying the cartoonists whose work I admired. I admired his work, but I never copied him. Seeing his work in Gleason comics (Boy, Daredevil), I knew his realism was too much for me to emulate at that time in the infancy of my career, but when, in 1953, he started drawing the Three Stooges, I hesitated; but I finally decided he was still too expert for me to imitate. This book prints about two dozen Stooges stories: all of three issues of the St. John comic (Nos. 1, 4, and 5; 1953 and 1954), eight stories drawn by Mauer; and the first three issues of the Dell Stooges (1959-60), drawn by Alvarado. He’s deft enough, but it’s Mauer’s bold outlines and finicky fineline embellishment that, still, captures my eye and admiration. The art appears to be shot directly from old comics, and that’s as it should be—un-Theakstonized and not retouched much if at all. But the slick paper taints the colors garish; I’d have opted for matt-finish paper that doesn’t reflect the light. An introduction by Joan Mauer, daughter of Stooge Moe Howard, succinctly rehearses her marriage to Mauer and his career in comics and, later, in movies.

Adventures Into the Unknown: The Pre-code Horror Anthology, Issues 1-4 Foreword by Bruce Jones 220 7x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardcover, $49.99 ANYONE HANKERING after the horror genre probably knows what Bruce Jones tells us in his introduction: “American Comics Group’s Adventures into the Unknown preceded EC’s first horror release [in the spring of 1950] by years”—nearly two, since the first Unknown is dated fall 1948. The stories are mostly unsigned and uncredited but supposedly include the work of Al Feldstein, Fred Guardineer, Edvard Moritz “and others” (two of whom, Edmund Good and Leonard Starr, signed their work). The paper is matt-finish, but the reproduction is achieved by digital reconstruction, which does about as much damage to the artwork as Theakstonizing does—fine lines are mashed together, creating blotches; details are often lost. All of the first four issues appear herein, even some advertising pages and text stories. Jones’ prefatory paragraphs are informative and low key and, as far as I can tell, accurate. The stories are grisly but highly entertaining. And there’s little or no actual gore—entrails dripping out and the like. Insightful, though, into a genre that would soon self-destruct in its own excesses.

Crime Does Not Pay, Volume 1: Issues 1-4 Foreword by Matt Fraction 280 7x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardcover, $49.99 IN HIS FOREWORD, Matt Fraction scarcely covers ground akin to that surveyed by Bruce Jones in the Unknown. Fraction doesn’t explain, for example, that the reason the first issue of Crime Does Not Pay (July 1942) is numbered 22 is that the book replaced an earlier Gleason title, Silver Streak, which ceased with No. 21. No thanks, then, to the exuberant but largely fact-less Fraction Foreword, what we have in this tome is the first four issues of the comic book that shaped the post-World War II comic book industry, yielding, eventually, the EC crime and horror books and, inevitably, the subsequent Wertham destruction of the funnybook biz. This is the title that precipitated it all, kimo sabe—the whole tragic malfunction. This book, another of the Dark Horse Archives, is more historically complete than the above Unknown: names of authors and artists are given when known, and as a result, we can find a couple of seriously illustrated stories from Bob Montana (whose pictures of women betray his Betty-Veronica tendencies), a couple by Norman Mauer before his distinctive drawing mannerisms emerged, and a couple by the unmistakable Dick Briefer (in one of which, “Corpses for Sale,” a good likeness of Igor, Dr. Frankenstein’s assistant, appears). As with Unknown, the artwork is digitally restored, but the final printed appearance is better in this title—perhaps because the comic books that provided the source were in better condition.

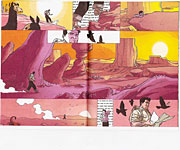

Jim Henson’s Tale of Sand By Jim Henson and Jerry Juhl, realized by Ramon K. Perez 152 8x11-inch pages, color; 2011 Archaia hardcover, $29.95 THE BEST DRAWN book I’ve seen in a long time, A Tale of Sand is the graphic novel adaptation of an unproduced, feature-length screen play written by Jim Henson and his frequent writing partner, Jerry Juhl. The book follows scruffy nobody, Mac, who wakes up in a strange town, and is commissioned to perform an unspecified task whereupon he is chased across the desert of the American Southwest by all sorts of surreal entities—native Americans, football teams, cavalry, etc.—who come and go at whimsy’s behest. The story itself is a bad dream that repeats itself, but Perez’s art is endlessly superb—the sort of pictures you return to again and again, simply to contemplate how wonderful drawn pictures can be. I first encountered the book in the local library, but I love it so extravagantly that I bought one to have forever at hand, to knit up the tattered sleeve of art appreciation whenever necessary. Here are a couple pages, showing the variety of Perez’s scope, the perception of his visual imagination, and the extravagant adventurousness of his page layouts.

I love the way Mac’s walking across the desert sand kicks up little puffs of dust as he shuffles along. Wonderfully authentic touch.

QUIPS & CLIPS “If there are ice cream trucks in the summer, why are there no hot chololate trucks in the winter?”—Aaron Karo’s Ruminations “Why is that 98.6 degree weather feels to unbearably hot? Shouldn’t that feel just right?”—More Aaron Karo

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets

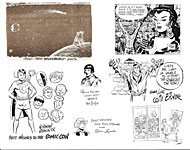

Boody: The Bizarre Comics of Boody Rogers Edited by Craig Yoe. 144 7.5x10-inch pages, color; 2009 Fantagraphics paperback, $19.99 THE MOST NOTABLE of Zack Mosley’s assistants on the harem-scarem aviation comic strip Smilin’ Jack was Gordon "Boody" Rogers, a fellow Oklahoman, who achieved comics history by contributing a one-page strip, Rattlesnake Pete, to the first newsstand comic book of original art (not reprinted newspaper strips), a weekly tabloid called The Funnies (1929-1930), and, much later, concocting two of the medium’s most outlandish creations: Sparky Watts, which starred a super-powerful bespectacled character, a parody of “the underwear boys” Rogers said, and Babe, an equally powerful female of the species. Sparky Watts graduated from newspaper strip to comic book, but Babe, although intended as a comic strip heroine, never appeared except in funnybooks. Introduced

with a short biographical essay by Yoe, who imitates Rogers’ way of talking in

deference to the man he doesn’t hesitate to call “the Greatest Cartoonist of

All Time!,” both Sparky Watts and Babe are given ample display in

the volume at hand, and Yoe has tossed in for giddy pleasure a Dudley story and

Jasper Fudd story. But these minor creations can’t hold a baby birthday candle

to Sparky or Babe. Sparky Watts doesn’t dwell so much on the eponymous

hero’s feats so much as his sidekicks’ feet: Slap Happy has giant feet, and

Hattie is all hat and feet and no other anatomy. Freaks, including alien beings

from outer space, were the stars of Sparky Watts. Talking with Michael Lorah at newsarama.com in 2009, Yoe revealed the background of Rogers’ strong woman: “Babe, Boody told me, got her name from ‘Babe’ Didrikson, then the first female Olympic superstar. Some might deem the hotties depicted by Boody as sexist, politically incorrect, but there never was a stronger, more confident woman in comics than Boody's Babe. I read the Babe stories to my girls, Avarelle and Valissa, to help instill in them a healthy self-esteem—and it worked! I'm proud to say that both are strong, smart young women with great confidence—and I owe it all to Boody's comic books!” But freakishness invades the pages of Babe’s stories, too. In one reprinted herein, her neck is broken during a wrestling match, and Babe wanders around with her head akimbo for the rest of the story. In another adventure, she is courted by a female impersonator, who looks like Clark Gable (except that Babe’s admirer has shaved off his moustache). Rogers had been among Mosley’s numerous wannabe cartoonist roommates during his early sojourn in Chicago, and he was Mosley’s first assistant, starting when Smilin’ Jack went daily in 1936 and continuing until 1939, when Rogers invented Sparky Watts. Rogers’ other distinction is producing the screwiest cartoonist autobiography on the market. Entitled Homeless Bound, it’s about 200 6x9-inch pages long, decorated with a few drawings and photographs, but nowhere in the book does Rogers discuss his cartooning career. The focus of the book is highschool hijinks and comical military maneuvers in WWII. The dedication of the book is revealing: “Dedicated to what’s his name, the guy who caused me to write this book. I was in a Manhattan bar, and the bartender said, ‘Get the hell out of here before I smash your face. Go some place and write your story: I’m tired of listening!!!’” The book consists of nothing more than a string of similarly punctuated would-be amusing anecdotes of the sort men who hang out in bars tell to keep the beers coming. A couple of them retail adventures of cartoonists Rogers knew, but he says nothing about his work on Smilin’ Jack, or Sparky Watts. Or Babe. Editor (cartoonist, book designer and publisher) Yoe surrendered while talking with Lorah to the temptation to compare Rogers’ work to that of another off-beat cartoonist, Fletcher Hanks, some of whose endeavors Fantagraphics published in I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets! Said Yoe: “I think there is a good comparison in that both cartoonists did far-out, wild and wooly works. Hanks did nutty stories because he was, apparently, nuts. Boody achieved his nutty oeuvre because he just loved way-out crazy funny stories. This was probably from growing up in the last of the Old West in Texas (he was born in Oklahoma territory before it was a state) and hearing the far-fetched yarns of cowboys gathered in his dad’s eateries. Boody developed his chops through hard work and training under some of the best cartoonists of the time, resulting in a fantastic ability to craft his comics. Boody went to Chicago and studied at the cartooning school of the Chicago Academy under Pulitzer Prize winner Carey Orr. And he hung out with or met Chester Gould, Harold Gray, Zack Mosley, Bill Holman, Carl Ed, and Reamer Keller. So, you see, he was in the right time and atmosphere for a talent like him to blossom.” But Rogers’ fame is the stuff of legend and cult rather than world-wide adoration. “Boody’s strips didn’t get into a lot of papers as it was a very small syndicate that distributed Sparky Watts,” said Yoe, “and his comic books were published by a smallish publisher, too. So I don’t think he got a lot of fan mail. He did get in his whole career one letter of criticism from a minister that complained about the sexy stuff in Boody’s comics. That really deeply bothered Boody. Though he had good red blood flowing through his veins, I don’t think Boody really was aware how weird his comics were and how salacious the ‘soft and round’ cartoon cuties he drew could be. I think he was just having good innocent fun in his mind and didn’t see how they could offend. And certainly I think he was oblivious to some of the more Freudian aspects of his work. I imagine Boody was primarily writing and drawing to amuse himself and his cartooning buddies, and the audience, then and now, were the lucky recipients of his brilliant stories and art.” Rogers was a star athlete in high school, Yoe reported, adding that Rogers told him he got his nickname, “Boody,” because “he was able to boot the football clear down the field.” (“Boody” was actually “booty.”) After leaving comics in about 1952, “Boody opened a couple of art supply stores in Arizona— Gus Arriola of Gordo used to come in for art supplies [when he lived in Phoenix]. Boody made enough to retire to a small town in Texas. He gathered with old farts there every day for coffee at the drug store and swapped stories.” Here are a couple Sparky Watts strips and a couple Babes, culled from the last four pages of Homeless Bound —the only comics work Rogers displayed in his autobiography. Mosley’s influence is apparent: in the three years Rogers worked on Smilin’ Jack, he learned to ape Mosley’s style perfectly.

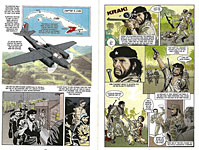

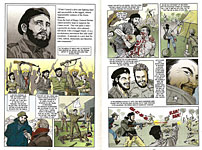

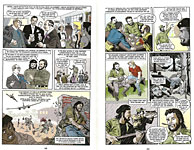

THE REVOLUTIONARY ICON Now that

Occupiers have emerged from winter hibernation, the mask of Guy Fawkes is back,

and so, in other corners, is the perpetual image of Che. The face, it seems, is

everywhere. The touseled tangle of hair, the wispy moustache, the eyes staring

into a distance none of the rest of us can see. And the beret, cocked at a

rakish angle—like the man, defiant of convention. A romantic image of an

idealistic revolutionary, a fighter for freedom, the dedicated foe of

oppression. Che. The image has been reproduced millions of times on millions of posters on millions of walls in college dorm rooms and on bullet-riddled buildings. Che. Photographs repeat the image, adding a cigar and a twinkle in the rebel’s eye: here is the swashbuckler for freedom. Fun and bloodshed on the revolutionary trail. But is the man a crusader or a hobo delinquent? Ernesto “Che” Guevara was ostensibly Fidel Castro’s faithful second-in-command of the Cuban revolution. Che was aboard the decrepit yacht Granma that sailed from Mexico in late November 1956 with 82 fighters to invade Cuba and free it from the cruel toils of Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship. Only Castro and Che and 15 rebels survived the first encounter with Batista’s troops. They took refuge in the Sierra Maestra mountains of southeastern Cuba and attracted recruits from the ranks of unsuccessful bandits, adolescent malcontents, unemployed dreamers and poverty-stricken peasants and opportunists looking for a way to strike it rich and powerful—the usual suspects in any would-be revolution. They gradually built a band of a couple hundred guerrillas with which to launch a war from the sidelines, chipping away at Batista’s regime, defeating small isolated units of his soldiers as the ragtag ensemble marched (limped, rather—swaggering a little from time to time) up the island towards Santa Clara (which Che, now in command of a secondary column, took in December 1958) and then Havana, which Che reached on January 3, 1959, two days after Batista fled the country and five days before Castro entered the city in triumph. While all of this was transpiring in the Caribbean, I was attending classes at the University of Colorado, assuming, at various times, sundry editorial positions on the campus newspaper. One summer (1958? or was it 1959?), I published an account of the revolution sent in by an on-the-scene eye-witness, a one-time CU student, body-building enthusiast and, eventually, soldier of fortune named Bob Brown, who would later found a magazine, Soldier of Fortune. But such were the distracting rigors of studying on the campus of one of the nation’s reputed top party schools that I barely knew who Castro was, let alone Che. So I was happy to see the “graphic biography” by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon when it appeared in 2009. This is at least the third time Jacobson and Colon have teamed to produce serious books in graphic novel form. Two of their previous ventures came out of the 9/11 catastrophe: After 9/11: America’s War on Terror (2001 - ) and The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation. I hoped in their Che (124 6x9-inch pages, color; Hill and Wang hardcover, $22), I’d find out what the Argentinian physician had really done for the Cuban revolution. Why the everlasting devotion by the young? Why the poster and its perpetual appeal? I found two other graphic novelizations of Che’s life and iconography among the bibliography in the Rancid Raves Book Grotto: Spain Rodriguez did Che: A Graphic Biography in 2008, and, also in 2008, manga artist Chie Shimano drew Kiyoshi Konno’s Che Guervara: A Manga Biography, re-issued by Penguin in 2010. The Manga Biography is a blatant act of hero worship, a symptom of the Che phenomenon, not an explanation. Rodriguez’s is a little better, but here, too, Che is a heroic figure, safe from any criticism. We’ll get back to both anon. In the Jacobson-Colon Che, Jacobson’s research and recitation seem meticulous. In addition to tracing the chief events of Che’s life and his engagement in Castro’s revolution, the book provides ample context—a survey of the plight of Latin American countries in the 1950s and the history that led to that decade (15 pages), the worldwide circumstances of the Cold War, and the careers of two of Latin America’s great liberators, Simon Bolivar (1783-1830) and Jose de San Martin (1778-1850). The text is pretty tedious stuff, but Colon’s drawings enliven every page. Sometimes, he is merely illustrating Jacobson’s captions; but often, the pictures and speech balloons offer supplemental information, augmenting the largely factual text with interpretive commentary, fleshing out the personality of Che, for example, adding drama to the emotionless recitation or reminding us that warfare is violent and bloody.