|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 292 (April 20, 2012). On the occasion of Sylvia’s retirement from print, we conduct a fond appreciation of Sylvia and her creator, Nicole Hollander, and we showcase a notable quantity of editorial cartoons from the last month. We also rehearse Paul Krassner’s obscene pranks and discuss the whys and wherefores of the most tabooed word in English, the F-word. And we report on Andy Capp’s sobering up, Corey Randolph’s retirement of The Elderberries, Brooke McEldowney’s latest daring in 9 Chickweed Lane (unwed motherhood!), cartoons in Playboy, the resolution of the disgraceful case of Canadian border guards seizing a computer and its owner for allegedly possessing child porn (it was manga), plus reviews of Stan Lee’s Mighty7 and commentary on Catwoman, Franchesco’s She Dragon, Fatale, Lobster Johnson, Batman, Mud Man, and All Star Western, and obits for Rex Babin, Moebius, Fran Matera, and Mike Wallace, a dramatist whose connection with cartooning is obscure. But first—

BUNNY BULLETIN: Announced Monday, April 16, Matt Wuerker of the online and multi-media political news organization Politico won the 2012 Pulitzer for editorial cartooning. He’d been a finalist twice, in 2009 and 2010, and he is also a Herblock Prize winner (2010). Interviewed by Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs, Wuerker said: “This feels fantastic, to state the obvious. This is a dream come true. I’ve been cartooning for some 30 years now, and up until a few years ago, I didn’t think anything like this was vaguely possible.” Wuerker freelanced editorial cartoons for most of his career until 2007 when he was invited to become a founding staffer at Politico. And that, he said, profoundly changed his career.“I credit the people aboard the good ship Politico,” he said. When he came aboard, he thought he’d have a nice ride on a tidy little ship. And then the ship became a rocket ship. “I can’t thank everybody enough — Jim VandeHei and John Harris [executive editor and editor-in-chief], in particular, for all of the creative license that they’ve given me,” he said in Politico’s report. “I feel like a piccolo player, and I’m in this great big orchestra, and as a piccolo player, if I’m just out there playing my piccolo, I’m just this annoying guy with this little instrument in the corner. But I’ve had the great, great fortune of finding myself in this great orchestra with major players and fabulous conductors and a fabulous concert hall, and that’s what this is about. So I share this with all of you. The much more serious players at Politico will be picking up [Pulitzers] in the years ahead.” Read more at ComicRiffs.com and/or Politico.com (both for April 16) and watch a video of Wuerker describing his feelings and overwhelming sense of good luck (can be seen at either). We’ll have a selection of his cartoons in the next opus, next month. And now, we resume our regular programming. Because of the vast length of this opus, you may wish to take a breather halfway through—that is, just after reading about Nicole Hollander. You choose. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Mandrake Movie Glen Keane Leaves Disney after 38 Years Matheson Case Ends Unhappily in Plea Bargain PayPal Bans Sales of Erotica Superman Letter Up for Auction Unconventional Editoons Reap Awards Jack Ohman Collects Scripps Howard Award Nick Anderson Gets Berryman Dr. Seuss Gets Insulted by “The Lorax”

PLAYBOY, GRAPHIC NOVELISH AND CARTOONS What To Do about the F-word Stan Lee in Time Stan Lee Court Case History Corto Maltese Screwed Up Academy Awards History—Not!

SYLVIA HOLLANDER, ICON Nicole Retires From Print

EDITOONERY Tony Auth Leaves Philadelphia Inquirer Signe Wilkinson Stays On Nate Beeler Goes to Columbus Dispatch The Future of Editorial Cartooning, Self-Syndication and False Cheer ROUND-UP OF THE MONTH’S EDITORIAL CARTOONS Paul Krassner and Outrageous Iconoclassicism (Mickey and Charlie Brown Fucking)

Loaded Words Not Permitted in New York Schools

THE FROTH ESTATE (Alleged News Institution)

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Darrin Bell and Rudy Park Funky is Forty Corey Randolph and The Elderberries Brooke McEldowney Does It Again—Unwed Motherhood Pastis’ Pearls Too Self-Referential? Andy Capp Sobers Up

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST Harold Camping and the End of the World Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious

BOOK MARQUEE More Wimps Bruce Timm’s Naughty and Nice Girls

BOOK REVIEWS Barney Google Hark! A Vagrant Comics and the U.S. South (Scholarly Essays) Two Krazy Kat Books Nancy Is Happy Stan Lee’s Secrets Behind the Comics The Complete Peanuts: 1983-1984 FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Stan Lee’s Mighty 7

FOUR-COLOR FANTASIES I’M READING THESE DAYS Catwoman and Guillem March Franchesco’s She Dragon Fatale Lobster Johnson Batman Mud Man All Star Western (Jonah Hex)

PASSIN’ THROUGH Obituarial Appreciations of Rex Babin, Moebius, Fran Matera, Al Ross And, Mike Wallace

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits PARADE, THE SUNDAY NEWSPAPER SUPPLEMENT that

usually includes (however postage-stampish) a “cartoon parade,” contained no

cartoons whatsoever, parading or otherwise, in its April 1 issue. I put it down

as a perverse April Fool’s joke, but when the April 8 issue showed up likewise

cartoonless, I began to fear for the perpetuation of the artform: Parade has

been a stalwart in publishing cartoons, but after two weeks in a row without a

giggle, could it be giving up on cartoons? Then came the issue of April 15—and

a welcome reprieve: two postage stamp cartoons within. ... Caricaturist Steve

Brodner does a regular “Brodner Minute” of animated editorial cartoonery at

washingtonspectator.org. ... Jules Feiffer received the 2012 Fischetti

Lifetime Achievement Award. ... Archie is getting married again in the current

Archie title continuity: another trip down Memory Lane, this time it’s

Valerie’s, the African American member of the Pussycats, who dreams she’s

marrying Archie. ... “Christians BD” (bande dessinee, French for “drawn

strip,” or comic strip), an ecumenical group of Catholic and Protestant comic

book makers with 25 years experience amongst them, appeared again this year at

the International Comics Festival at Angouleme, France, in a special

“Christians BD” section; the group’s objectives are to promote the comic book

style of explaining Christianity, to establish a link between faith and reason,

and to attract more authors. ... And, not to abandon Archie Comics too quickly,

the alternate cover of the second issue of Kevin Keller is by Dan

Parent, an echo of the cover of Archie No.1, this time with Kevin on

skates jumping the barrel on the frozen pond. Why the pond would still be

frozen by mid-April, don’t ask. ... And right here, just at the corner of your

eye, we have posted one of those mind-boggling instances of the right hand not

knowing what the left hand doeth when it comes to displaying sexy covers in Previews. And yet, both hands are in plain sight all the time. Who are these people?

Moral self-righteousness gone amuck (but containing, therein, a lesson for us

all: suppression of sex will never succeed). Warner Bros is conjuring up Mandrake the Magician in celluloid, picking up the movie rights to the classic comic strip with Atlas Entertainment producing, reports Borys Kit at hollywoodreporter.com. Created in 1934 by Lee Falk (who also created The Phantom in 1936), Mandrake is an illusionist who has the power to quickly, instantaneously, hypnotize his foes. Forever attired in top hat and tails, “Mandrake fights evildoers ranging from gangsters to masters of disguise to aliens. Mandrake is one of those characters that Hollywood has long tried to nail down in a viable movie adaptation. Columbia Pictures made a 12-part serial in 1939, and a TV movie aired in the 1970s, but nothing has made it to screens since.” Animator Glen Keane, a 38-year veteran of the Walt Disney Animation Studios who worked on such classics as “The Little Mermaid,” “Beauty and the Beast” and “Aladdin,” announced last month that he is leaving the company. According to HollywoodReporter.com, he said that while the studio has been his "artistic home," he decided after "long and thoughtful consideration" that there are "endless new territories to explore" and so he is moving on. The announcement came as a shock. "He's such a Disney icon and an inspiration to so many people," one source said. Confirming his departure, a Disney spokesperson said, "Glen Keane has decided that the time has come to take the next step in his personal exploration of the art of animation. As much as we are saddened by his departure, we respect his desires and wish him the very best with all his future endeavors." In 2000, someone broke into Nicolas Cage’s house and stole his mint copy of Action Comics No.1; in April last year, the priceless artifact (one of only two in such pristine condition known to experts) was found in an abandoned storage locker in California's San Fernando Valley by a man who had purchased the contents of the locker. It returned to Cage just in time to help the actor with his financial travails, which saw him face bankruptcy for failing to pay taxes despite having earned more than $40m in 2009. Cage sold the funnybook for a record-breaking $2.16m in November. And now this whole preposterous adventure may find its way to the big screen: Lionsgate is reported to be interested, and the spec screenplay “takes the form of a heist comedy in which a group of fanboys break into Cage's home and steal the comic,” reports Ben Child at guardian.co.uk.

BORDER ORDEAL ENDS BUT JUSTICE HAS STILL GONE AWRY ICv2.com reports that the Canadian government has dropped all criminal charges against Ryan Matheson (previously referred to as "Brandon X"), an American computer programmer whose laptop was seized by Canadian customs officials when he traveled to Canada from the U.S. in 2010. He was arrested and detained based upon images in his laptop that customs officials deemed “child pornography.” In a plea bargain that resulted in the dropping of all criminal charges, Matheson pled guilty to a non-criminal code regulatory offense under the customs act of Canada and will not stand trial. Matheson's defense cost $75,000. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund helped by recruiting expert witnesses for the trial and providing $20,000, while the Comic Legends Legal Defense contributed $11,000, but that still leaves Matheson with nearly $45,000 in debts relating to the case. The CBLDF is currently seeking funds to help pay off Matheson's debt and to create new tools to prevent future cases. Visit cbldf.org for details. The ICv2 report continues: Now that the case has been settled the details of Matheson's arrest and detention have come out. Matheson was subjected to abusive treatment by the police when jailed and then placed under harsh bail conditions. His life was severely disrupted for two years during which was unable to use computers or the Internet outside of his job because of the strict conditions of his bail. In an accompanying statement Matheson described his situation: "I was given extraordinarily strict bail conditions considering it was my first offense of any kind and I had a totally clean record. My bail conditions tightly restricted my use of computers and the Internet. My conditions had even specifically named a single company I could work for, which prevented me from advancing my professional career. I am a computer programmer and I've been in love with computers ever since I was seven years old. To place such overbearing conditions on me was heart-wrenching and very difficult to endure. Even for people who do not have a life and career based on computers, I believe completely restricting Internet access is wrong; too many things in life and society nowadays rely on the Internet. In my opinion, it's like restricting use of basic utilities like water and electricity." Matheson also describes his longstanding interest in manga and anime, which had led him to study Japanese language and culture: "I first got into anime when I was about eight years old by watching Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball Z that aired on tv at the time. Soon after I started reading manga with my first volume of Ranma and began drawing my own illustrations and making my own animation flipbooks. To this day I still draw and have attended art and drawing classes. I have been studying Japanese since high school. To have this healthy and fulfilling hobby of mine deemed ‘unfavorable,’ ‘deviant’ or ‘criminal’ by ignorant government officials is insulting and degrading not only to me, but also to the millions of fellow fans who take part in enjoying this art. After going through such a challenging and difficult period of my life, my own convictions about what anime and manga mean to me have become stronger than ever before." At last the image that Canadian customs found so objectionable has been identified publicly, a moe-style parody of a classic Japanese wood block prints called the "48 Positions," which were wrestling positions in the original classic print and rendered as sexual positions in the parody. As anyone familiar with manga and anime knows, "moe" refers to cute, often diminutive characters, which undoubtedly led the overzealous customs officials to suspect child pornography, though it is totally obvious that no underage models were used to create the illustration, which contains very little detail in the rendering of the sexual acts.

PAYPAL BANS TRANSACTIONS INVOLVING EROTIC STUFF In early March, Betsy Gomez at Comic Book Legal Defense Fund reported that PayPal told publishers that they cannot sell erotic material that depicts incest, pseudo-incest, rape fantasies, bestiality (including non-human fantasy characters), and BDSM. “Selling these materials will result in the deactivation of the publishers’ PayPal accounts. As a result of PayPal’s new policy, many publishers are taking down erotic work. Anyone who uses PayPal is subject to their terms of service. The banning of the erotic work may have less to do with PayPal’s opinion of the work and more to do with business practices. Commentary on both ZDNet and Daily Kos notes that erotic work carries a high likelihood of buyer’s remorse, and credit card companies charge higher fees for returns on such high-risk content. PayPal likely instituted to practice to avoid these fees.” In response, CBLDF reports, the American Book Sellers Foundation for Free Expression and the National Coalition Against Censorship sent PayPal a letter decrying the policy. The list of organizations signing on to ABFFE and NCAC’s letter is growing, and CBLDF has joined the coalition against PayPal’s erotic content policy.

AGED SUPER ARTIFACT Shed Light on Siegel and Shuster Rights A check for $412 is being auctioned off, and 12 bids so far have jacked its value to more than $25,000. The check on the block is the one endorsed by Jerome Siegel and Joe Shuster when they signed over their rights for creating Superman. Bidding at Comicconnect.com began March 27 and will close April 16. “The check includes an accounting,” writes George Gene Guistines at the New York Times: “$130 for the rights to Superman, $210 for stories in Detective Comics and two $36 payments for stories in More Fun and Adventure Comics. The back of the check includes a stamp from a United States District Court from 1939, when it was used as evidence by DC Comics in its successful copyright infringement lawsuit against Victor Fox, a publisher who unveiled Wonder Man, a hero deemed too similar to the Man of Steel. “The signing away of the rights to Superman long plagued his creators, and their heirs have been waging a court battle to restore their claim on the copyright. In March 2008 a federal judge in Los Angeles ruled that the heirs of Siegel were entitled to claim a share of the United States copyright to the Superman character. Time Warner, which owns DC Comics, would keep the international rights to the character. Last month, the Hollywood Reporter said that Warner Brothers Studios and DC Comics had filed a brief before the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit to try to hold on to all rights to the character.”

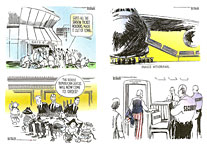

UNCONVENTIONAL EDITOONS REAP AWARDS Portland-based editooner Matt Bors won the prestigious Herblock Prize for 2012, becoming the first alternative political cartoonist to win the award. In reporting the Herb Block Foundation’s March 12 announcement, Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs remembered Bors’ “withering Steve Jobs obituary cartoon” (you can see it at Opus 285, and while your off surfing, stop in at Opus 288, where we recollect Bors’ Christopher Hitchens obit cartoon, embodying a similarly off-beat approach). Nationally syndicated by Universal/Uclick, Bors has also done cartoon reportage, visiting Haiti last year and, the year before, trekking off to Afghanistan with Ted Rall (see Ops. 265 and 267). Two of Bors’ masterpieces in a minor key appear down the scroll. "It's an honor and was completely unexpected," Bors told Cavna. "I'm humbled to be included in the group of previous winners" — a list that includes such recent recipients as Politico's Matt Wuerker and the Washington Post's Tom Toles. The honor comes with a $15,000 "after-tax cash prize,” which, Bors said, is “more than I've ever made in a year from my editorial cartoons.” An editor at the Cartoon Movement website, Bors plans to use the money to redesign his site (MattBors.com) and find ways “to keep this going for the long haul." Bors's cartoons are "relevant, smart, surprising, wickedly funny," said Toles, who was one of the judges along with the Philadelphia Daily News' Signe Wilkinson and Jenny Robb, curator at OSU's Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. Wilkinson cited Bors's memorable Jobs "obit" cartoon, which she said was "the most masterful cartoon of this masterful collection." This year's finalist for the Herblock Prize is another altie-editoonist, Jen Sorensen, whose Slowpoke she syndicates herself. Sorensen, who will receive a $5,000 cash prize, said: "It's so nice to see our genre of political cartooning acknowledged after so many years in the wilderness. I'm, of course, deeply flattered,” she said to Cavna. The

Herblock Prize honors "distinguished examples of editorial cartooning that

exemplify the courageous standard set by" legendary Washington Post political

cartoonist Herblock. Bors and Sorensen will receive their awards May 10 in a

Library of Congress ceremony, at which Doonesbury creator Garry

Trudeau will deliver the annual Herblock Lecture. “As you might have guessed, this one is about last month’s [“I thee rape”] Doonesbury strips, which over 50 newspapers refused to print. Personally, I'm surprised the number was that high. I may be an easy audience, but I thought the strips were witty and tastefully done. Thursday's comic was intense, but it was hardly in poor taste. Have these editors not seen reality television lately? Compared to that, Doonesbury read like a Lewis Lapham essay. “Notably, this week's cartoon marks the first time I've had a strip pulled in over a dozen years of drawing Slowpoke. One of my weekly papers is owned by a daily paper that decided not to run the Doonesbury strips, so the editor, who actually liked my comic, had to ask for a substitute. The layers of irony here are impressive.” The last cartoon (lower right) in the exhibit is by Jack Ohman of the (Portland) Oregonian, who won the Scripps Howard Award for editorial cartooning and received $10,000 and a trophy chiefly in recognition of the effectiveness and initiative shown in his multi-panel cartoons on Sundays. In nominating Ohman, his editor, Robert Caldwell, wrote: “Jack addresses issues of child abuse, the death penalty, and the unemployed in Oregon; he goes out into the community and reports in a spare, stark style. He has pioneered this local approach to the point that readers view this as the equivalent of a popular local column. ... Jack’s style excels because of his boldness, his attention to detail, and his topic selection. He doesn’t go for the typical gag approach, and you can see the fine line of irony instead of the sledgehammer. ... His work is highly original, he doesn’t employ cliche, and he claims that he has forgotten how to draw Uncle Sam. There are no labels. ... His caricatures are dead-on.” I concur on all counts, adding only that Ohman is perhaps the most skillful caricaturist working in editorial cartooning today. And here are a couple of those Sunday extravaganzas with national targets.

Berryman Winner The Houston

Chronicle reports that its editorial cartoonist, Nick Anderson, has

been honored with the Clifford K. Berryman and James T. Berryman award for

national cartooning “for work that exhibits power to influence public opinion,

plus good drawing and striking effect.” Anderson won the Pulitzer Prize in

editorial cartooning in 2005; in 2006, he joined the Chronicle, where he

has pioneered a method of coloring his cartoons using a computer program that

creates digital paintings characterized by subtle textures and striking images.

Near here, we’ve posted a couple exemplary Andersons. The Berryman Award started in 1989 when Florence Berryman, former art critic of the Washington Star, endowed an annual award in memory of her late cartoonist father and brother, both Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonists. The winner receives a $2,500 prize and an engraved crystal vase, usually presented at the National Press Foundation's Annual Awards Dinner in Washington, D.C.

Fan Starts Medal Campaign for Garry Trudeau Michael Masley, a 59-year-old Los Angeles-based musician, has launched a Facebook campaign to get the cartoonist the nation's highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Writes Patrick Gavin at Politico.com: “The campaign, which currently has more than 1,800 members after a week, praises the totality of Trudeau's career” as one of “democracy’s closest friends, whose protean originality, courageous breadth of thought, generosity of spirit, great sense of justice and uniquely brilliant wit, have so well served American Culture for decades.” "Trudeau has balls," Masley told Politico. "He's one of the most responsible celebrities out there. He's an icon. He's a national treasure." Gavin closes by noting “a bit of irony when it comes to mixing Trudeau with the Medal of Freedom: when Frank Sinatra was given the honor in 1985, Trudeau ended up in hot water for using the occasion to rib Sinatra's alleged mob ties.”

A Wretched Lorax I haven’t see “The Lorax” yet. And I may not—if I am to be guided by a local Mile High critic, Jonathan Lack, who, writing in a giveaway weekly tabloid, calls the film a “wretched insult” to Dr. Seuss. The book, Lack remembers, “is a sad, uncompromisingly bleak story of a world desolated by greed.” In the book, a boy living in this barren waste seeks knowledge to restore the environment and make the world right again. In the movie, the kid is living in luxury in a thoroughly modern city. When he leaves to wander the wasteland beyond the city’s borders, he does so merely to impress the pretty girl next door. “Instead of a serious, down-to-earth fable about the environment, the film is a broad, pandering comedy, filled wall-to-wall with terrible jokes, endless slapstick, pop culture references, horrifyingly awful musical numbers, and long, complicated car chases. Yes, you read that right: ‘The Lorax’ now includes car chases.” The animation is “stupendous,” Lack says---”lush, gorgeous, immaculately detailed and beautifully colored. In every other regard, the movie is an utter failure. ... If there was one thing we know Dr. Seuss believed in, it was that children are worthy of the best. Ignoring all its other sins, ‘The Lorax’ film violates that crucial principle, and that alone makes it an abject failure in my book.”

READ AND RELISH (A Short Break From Rampant Seriousness) Three Rules for Old Guys (from the autobiography of Piers Anthony): 1. Never pass up a restroom. 2. Never trust a fart. 3. Treat every erection like a gift from the magi.

THE GRAPHIC NOVEL & CARTOONS IN PLAYBOY Also Sex Playboy has lately taken to glorifying the graphic novel form. Almost. In the January/February 2012 issue, 6 pages are devoted to “Superjail!,” a static rendition of Adult Swim’s animated series of the same name by Christy Karacas, which is now in its third season, commemorated, perforce, by this episode in Hugh Hefner’s magazine. A little too manic in both art and concept for my taste. More to my liking is the offering in the April issue: by Walking Dead’s Robert Kirkman, “Michonne’s Story” recounts a turning point in the life of the katana-wielding survivor. More ambulatory dead people, but appealingly interpreted by artist Charlie Adlard in his best Caniff-like manner, enhanced by Cliff Rathburn’s gray tones. And while we’re pausing here at the body shop, let’s take inventory of Playboy’s cartoon content as we’ve been wont to do occasionally as the magazine sinks slowly in the West. Despite the snark, Hef’s not doing bad with cartoons. The number of full-page color cartoons remains approximately constant, about 5-6 per issue; and the smaller cartoons are slightly more numerous in these two issues, 10 in each. Not counting the Olivia pin-up page, which carries a caption so it effectively doubles as a cartoon (but I’m not counting it, as I said). Both issues also continue to offer Bobby London’s half-page strip Dirty Duck and Meaty Myths by an indecipherable signature that looks a little like Schin. Less important than the gross number, however, is the ratio of cartoons to page count since the number of cartoons is likely determined to some extent by the number of pages available to print them on. The January/February issue’s ration of full-page cartoons is 1/30; April, 1/28 (that is, one full-pager for every 30 pages; ditto every 28 pages). For the smaller cartoons, it’s 1/21 in the January/February issue; 1/14 in April. The January/February issue also offers a two-page retrospective of Erich Sokol cartoons, 8 in all, but since they’re reprints, I’m not counting them in the calculation. (Sokol’s cartoons showed up in Playboy just about the time Jack Cole offed himself, and because Sokol’s wimmin looked somewhat like Cole’s, I always thought Hefner recruited Sokol as a replacement for Cole. But years later, I discovered that the time sequence doesn’t support this fond notion. If I remember aright, Sokol had started appearing while Cole was still alive.) One of the full-pagers in this issue is by editoonist Bill Schorr, who enjoyed a brief career at Playboy some years ago when he helped in the brief revival of Little Annie Fannie. Since Schorr lost his newspaper perch a few years back, he probably has a few more spare hours a week than previously, so, one assumes, he fills them by doing gag cartoons to submit to Playboy. Not an altogether safe assumption. He also continues to produce a daily newspaper comic strip, The Grizzwells, and does some editorial cartoons for syndication through Cagle Cartoons, so I’m not sure how many erstwhile idle hours he may have. (Another fond notion evaporates.) In any event, it’s fun to see him in Playboy. That the January/February issue has more full-page cartoons than the April issue (7 versus 5) should not surprise: it’s a “double issue” and it has more pages, 210 versus 142. But as a “double issue,” it isn’t, as you can plainly tell, twice the size of a “normal” issue. It’s only 32% larger. So it has 32% more full-page cartoons. But not, alas, 32% more of the smaller cartoons: both issues have only 10. This

is a feckless quibble, of course. The “double issue” has two Playmates, after

all—two gatefolds—plus the usual 11-page round-up of the year’s Playmates and a

stunning 10-page pictorial featuring Lindsay Lohan as Marilyn Monroe, posing

naked on that legendary crimson cloth in nearly perfect imitation of Marilyn’s

appearance in the first issue of Playboy, 59 years ago. And here, at

your elbow—as promised—the pertinent visual aid. (Are you glad that you’re a

$ubscriber?). The “double issue” also includes the customary year-end report on “The Year in Sex.” Here again, Playboy is playing fast and loose with the language: just as the “double issue” is not twice the size of the usual issue, “The Year in Sex” is less than complete by at least half. Nowhere in the six pages of photos do we find any pictures of naked men. Barenekkidwimmin abound, bosoms flaunting. But no naked men. One male, however, saves the sex: Vladimir Putin appears bare-chested. Judging, as we must, from this plethora of pendulous female pulchritude, we must assume that for Playboy, “sex” has come to mean, simply, “naked women.” Perhaps only a linguistic perversion, but a perversion nonetheless.

***** OUR VOCABULARY is perversely puny on matters of sex. Take the word fuck, for example. Fuck, a perfectly serviceable word for sexual intercourse, has been replaced by right-thinking people who talk about their bed-rattling adventures as “having sex.” Having sex? Having a donut? Having a dish of ice cream? Having a night out? Can’t we do better than that? We don’t “have” sex: we experience it. Sometimes we wallow in it. And in the height of that transcendent experience, we are nearly overwhelmed by it. “Having sex” is much too effete a term for what transpires. “Making love” is better, a teense poetic, but two words, not one and therefore not, strictly speaking, a good passionate alternative to fuck. We have other words for sexual intercourse: fornicate, copulate, coitus. But these are a little clinical, too Latinate. “Let’s copulate.” Doesn’t work. And coitus is a noun, not a verb. Closer to real life are such slangy terms as screw, hump, bang, rock-‘n’-roll, swive, lay, ball. But the first two seem crude—too much in the same vein as fuck; the latter two are better, but they seem somehow passive. Fuck is much more active—an aggressive, fun-loving word. Bang comes close, but it’s a little too fun-loving, too noisy—a clang of cymbals instead of the earnest thump of bellies bumping. Rock-‘n’-roll, like bang, is close, but it is so closely associated with the music industry that it’s too ambiguous for our present purpose. And swive is simply archaic. Fuck is the best word for it. By far. In the landmark opus The F Word, Roy Blount, Jr. opts for fuck. “Sounds a little like a suction-cup arrow hitting a wall,” he muses. “Or someone pulling it off. Or putting a foot down in a quagmire. Or pulling it out. Connection, detachment. The old in-and-out,” he finishes, deploying yet another slangy but not quite right term. “Fuck,” saith Charles Panati in his Sexy Origins and Intimate Things, “is lusty, aggressive, and erotic and more truthfully reflects the expression of passion.” If fuck sounds so right, why are we so reluctant to use it as the term for sexual intercourse? Although fuck has suffered as a verbal taboo for centuries, it’s now infiltrating ordinary everyday conversation like never before in the history of the English language. “It’s our worst word, at least of one syllable,” says Blount, “and maybe out strongest. Shakespeare, Dickens, Mark Twain never used it, at least in print.” As recently as 1948, the publisher of Norman Mailer’s war novel The Naked and the Dead persuaded the author to render the soldier’s commonest epithet as fug—“which led Dorothy Parker to tell the young novelist, when she met him at a party, ‘So you’re the man who can’t spell fuck.’” And yet, by 1995 when The F Word was published, fuck was being heard “in the best-regulated livingrooms.” But it wasn’t being used as the best word for “sexual intercourse.” It was used as a curse word, an adjective—absofuckinglutely. And it still finds employment in these somewhat marginal ways. But not for the old in-and-out. Only the very youthful and hip use it to describe copulation. And the very youthful and hip eventually grow older and become less hip and less fucking glib, too. Despite its frequent cropping up in ordinary conversation, fuck isn’t home free just yet. In the Introduction to The F Word, editor Jesse Sheidlower writes: “The increasing acceptance of fuck in American society is not a sign that its use should be encouraged. ... It would be as misguided to say that fuck should be used everywhere as it would be narrow-minded to insist upon its suppression.” He reminds us of George Carlin’s classic list of “Seven Dirty Words” that can’t be used on radio or tv: fuck, shit, piss, cunt, cocksucker, motherfucker and tits. Times have changed a little since Carlin conjured up his list. Many mainstream publications—Harper’s, Atlantic, Playboy—print fuck without apology. As they should. But newspapers don’t use it. While taboos are weaker, they’re still healthy enough to inhibit our uttering fuck whenever we think of it—particularly in reference to sexual intercourse. The word is simply a verbal stink bomb. The word is very very old. At least a thousand years old. Probably more. Maybe as old as oral language itself. And according to researchers, it has always been taboo. Always. (And still.) It’s origin is Germanic—foken or ficken, meaning “to beat against” or “to thrust,” allusions to the male body bumping the female while fornicating. The taboo about fuck is so strong that it prevented the word from being printed until 1475, its earliest known appearance in print in English. But everyone agrees that fuck was spoken and heard for centuries before finding its way, at last, into print. Why are words like fuck and cock and cunt so offensive? Freud gives one explanation: “The off-color saying is like undressing the person of the opposite sex to whom it is directed. ... It obliges the attacked person to fancy that part of the body [cock, cunt] or that action [fuck] to which the word corresponds.” Panati offers another: “Dirty words have a great capacity for arousing emotions, for awakening passion. The appeal of erotic literature is based on its use of racy language. ... Dirty talk adds a dimension to passion. Obscene words are an aphrodisiac. Erotic literature is ancient, existing in all cultures. ... Surveys show that three little words—fuck, cock, cunt, the act and the organs engaged in it—are the most taboo and, hence, erotic in the English language. The forbidden word is graphic, a turn-on—the reason it’s forbidden.” Now we’re getting somewhere. Fuck is forbidden because it alludes to sexual passion and therefore can arouse lust. My guess is that as human sapiens (sic) moved out of caves and began standing upright and, at the same time, started establishing communities and—presto!—civilization, they had to learn to control their lusts. Lust violates decorum and thereby threatens the order essential to civilization. Thus, the thriving of civilization and its very survival required that lust be kept in check. And words that might arouse lust—like fuck—were therefore banned, forbidden. Tabooed. My theory explains the taboo, and the explication also asserts the power of the word, accounting for its endurance—and its attraction. Among the other human traits that had to be controlled was individuality. The basic unit of human society after the family is the tribe, and the survival of the tribe (and therefore the species itself) required that individuals sacrifice their private, personal aspirations to those of the tribe. That’s how it worked for a long time. But given the egocentricity of each representative of the human (sic) sapiens, over the centuries, the individual gained ground; eventually, the individual acquired a societal value that rivaled that of the tribe. And the more the individual emerged, the more society realized that it would not be destroyed if it permitted individuality, deviance and diversity, in deeds and thought. Hence, democracy with its accompanying individual liberty. By the same token, if society could survive the emergence of individuality, it could probably survive the loss of a taboo about fuck. And so we find the word bandied about in even polite society these days. For a while. But societal fear of lust is strong. All religions lobby against the word. Even linguists like Jesse Sheidlower warn against it. We may yet see a return to those dear dead days of yesteryear when fuck was forbidden wholesale, everywhere. After all, as Blount says, “There are limits!” He foresees a return to euphemism. The F-word will become, simply, eff. “Effing will come back, and other eff-words,” he speculates, providing a conversational example: “You’re lookin’ mighty effable this evenin,’ Miss Effie—pardon my effrontery in bein’ so effusive.” “Why thank you, Eph, don’t mind ef’n I do. And may I say you’re lookin’ mighty efficacious, y’self.” But, adds Blount slyly, “there will be no doubt what they’re thinking.”

STAN LEE REDUX AND REDUX If you can’t

get on the cover of Time, the next best place is the last page in the

magazine. (Think about what you do when you first pick up a magazine at the

newsstand: you thumb it, flipping the pages from the back to the front, and the

first interior page you see is the last page.) And that’s where Lee is in the

March 19 issue, answering in the “10 Questions” feature, which is illustrated with

a handsome photograph of the Man Himself. Asked if it’s true that he’s been married for 64 years to the same woman, Joanie, Lee said: “Oh, yea. I wouldn’t lie about it.” Does a long marriage require a superpower? “You must marry the right girl,” said Lee. Meanwhile, a defunct entity known as Stan Lee Media Inc. is suing Stan Lee over the rights to characters the latter allegedly created. You can find the convoluted details unraveled by Brad Stager at www.movieline.com/2012/03/07/stan-lee-vs-stan-lee-the-epic-legal-follies-of-a-comics-mastermind In the course of the piece, Slager rehearses the history of post-Marvel Stan Lee; to wit: In the early 1990s,”Lee was still the figurehead at the then-struggling Marvel. Throughout that decade the comic company over-leveraged acquisitions and hemorrhaged enough money to land in bankruptcy. By 1998, the company used that proceeding to end Lee’s contract of $1 million annual salary for life. Lee left Marvel and started a new company, Stan Lee Entertainment (soon becoming SLMI) as a way to maintain control over his intellectual property. The company was started by Lee with a close friend [that’s what it sez here, “close friend; some friend], Peter F. Paul — a man with a checkered history of federal drug and conspiracy convictions for crimes including, but not limited to, selling $8.7 million worth of ‘nonexistent coffee’ to Fidel Castro. Paul was to have an equally troubled future that would soon ensnare his new partner Lee. “Initially the company made an impact with online animated comics, developing new characters on Web sites with the expectation of spinning them off into various media. The company enjoyed initial success. The creation known as The 7th Portal, for starters, had been acquired by Fox television for foreign broadcast, and was featured as a 3-D attraction for Paramount Theme Parks. “Like so many digitally-based companies of the era, SLMI foundered with the bursting tech bubble. Then, after Peter Paul secured a bridge loan to prop up the struggling enterprise, he and numerous board members dumped large amounts of holdings ahead of the ultimate stock collapse. The Securities and Exchange Commission feared insider trading, and Paul feared the SEC — so he fled for Brazil. The company's stock price plunged to $.13 per share by the end of 2000, and it filed for bankruptcy in February 2001. Sensing both SLMI's downfall and encroaching legal troubles, Lee founded POW! Entertainment — a new company that was strictly his own. He transferred the rights of his properties to POW! during bankruptcy and then departed SLMI. ... “The latter events coincided with Marvel's incredible comeback. Led by Vice Chairman (and longtime Marvel power broker) Isaac Perlmutter, the company had climbed out of bankruptcy by licensing the film rights for several of its highest-profile characters including Spider-Man (which Sony would soon develop into a box-office behemoth), X-Men and the Fantastic Four (both successfully adapted by Fox). In light of this swift, lucrative reversal of misfortune, Lee brought suit against Marvel for terminating his contract and demanding payment on the promise of 10 percent of profits earned by characters of his creation. Yet even while he pursued this lawsuit, Lee — and his intellectual property — returned to Marvel. ... In 2005, Marvel and Lee settled their case before going to jury; the court records were sealed, although Marvel later reported a $10 million write-down with regard to Lee.” Without doing any more research than quoting Slager, it would seem that Stan Lee is still collecting checks from Marvel, assuring him a comfortable retirement; and he goes on inventing new stuff, too. Meanwhile, on March 21, the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals denied SLMI’s bid for rights to Spider-Man, delivering a momentary setback to the company. But, says Eriq Gardner at HollywoodReporter.com, “SLMI is not finished in its long-running effort to reclaim property the company argues was stolen out of bankruptcy, hoping that the latest appellate decision opens the door for the company to pursue legal action in California against Lee himself.”

DESECRATION AND DISAPPOINTMENT OVER SALT SEA Corto Maltese, the laconic early 20th century seafarer created by Italian cartoonist Hugo Pratt, is returning to these shores in the first English translation in twenty years, reports John Seven at Publishers Weekly. (The last time Corto reached us in English it was in seven black-and-white volumes translated for and published by NBM in the late 1980s.) Seven rehearses briefly the intellectual origins of the character: “Just before Pratt was devising his character, Malta had become independent of Britain and stood as a Mediterranean symbol of freedom,” says Seven. “The character of Corto was born in the capitol of Malta, La Valletta, and functions as a walking extension of that symbolism.” The newest book recording his first adventure, The Ballad of Salt Sea (initially published by Casterman in 1975; then NBM in comic book format, seven issues, 1996; translated by Ian Monk), is now on the stands. But it isn’t winning kudos from fans, whose hopes were soon blasted. The ComicsBeat reports that “although the new edition uses the color of the original Casterman edition ... it also uses the redesigned page format of the Casterman editions, and the files are at a very low res, resulting in ugly scratchy-looking art. “When we eagerly flipped open the pages of the edition when it arrived we were ... underwhelmed. Quite frankly, the rugged beauty of Pratt's line has been made ugly, rough and amateurish by this awful low res version.” Designer Chris McDonnell explained that he had asked for the original format pages and better quality line art files, “but the files that we ultimately used were the only option for files provided by the licensor or the estate (I don't know who).” ComicsBeat continues: “When, over the years, we asked why there was not a good English version of Corto, we were always told that it was because the licensor couldn't come to an agreement with the U.S. That made it sound like quality concerns were the issue. But instead, it seems that somehow Casterman and Rizzoli have produced an awful looking, budget version of the story.” ComicsBeat goes on to quote from a letter to the publisher from Big Planet Comics, a retailer with stores in the Washington, D.C. area: “The art has been scanned at a low resolution, leading to pixelization that obscures or erases the smoothness of the fine and precise art of Hugo Pratt. ... Most offensively, the original panels of Hugo Pratt's art have been resized, cut, and cropped to fit this amateurish new layout scheme, in some cases removing over a third of each panel, or splitting a panel into two new panels. Some panels appear to have been zoomed in, resulting in further loss of quality and removing more of Hugo Pratt's art. These terrible mutilations of Hugo Pratt's art are insulting enough, but there are numerous panels where someone has taken upon themselves the hubris to fill out the gaping holes in the modified panels by adding to the art itself.” Sad. But at least we have the NBM books.

Please Don’t Shoot My Dog While watching Billy Crystal’s Big Show last month, I was reading, during commercials, a vast tome entitled The Academy Awards: The Complete History of the Oscar by Gail Kinn and Jim Piazza (2002). In 1931, the Best Director statuette went to Norman Taurog for “Skippy.” The title role was played by Taurog’s nephew, Jackie Cooper, who was famously able to cry on cue because his uncle told him if he didn’t, he’d shoot the kid’s dog. The role made Cooper’s reputation as a child actor, and he went on to play hundreds of other parts in movies and tv productions. But he never forgot his uncle: when he wrote his autobiography, Cooper entitled it Please Don’t Shoot My Dog. The pages of this history devoted to each Oscar celebration offer numerous other tidbits under such headings as “Firsts” and “Unmentionables.” Taurog’s threat appears under the latter. Under the former, comes this: “Jackie Cooper’s vehicle, ‘Skippy,’ was unquestionably the first and only time a peanut butter was named after a movie.” The two could have handily reversed categories. Nowhere do Kinn and Piazza mention that the movie gave celluloid life to Percy Crosby’s hugely popular comic strip, Skippy, from which the peanut butter criminals stole both the name and a familiar graphic (the fence with “Skippy” lettered on it). And so we have an object lesson in why anyone’s “Complete History” of anything ought to be glimpsed askance: too much history gets rolled up, over and over again, until telling pieces of it are ground out of existence. For the complete story of the Great Skippy Robbery, visit Harv’s Hindsight for April 2004.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment and in what follows under the guise of “news” is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

SHORT ANNOUNCEMENT. Here at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer, our news department has been systematically supplied with news about all things comics for several years. Our supplier, the dedicated and diligent Mike Rhode, decided recently to gafiate for a while. Said Rhode: “After 11 years and 4 months, and over 102,000 citations, I'm going to step back from doing Comics Bibliography. I've just been spending too much time on this, and not enough time on the comics and books that inspired it, let alone the rest of my life.” In exiting, however, he sounded a note of cheer: “The mass growth of stories on comics and cartoons—the 'success' story of the [comics] industries—has meant that the amount of time it takes to do this has grown to hours per day. Backing off will hopefully help me relax and enjoy comic art more again.” We envy Mike the time he thinks he’ll now have to peruse the hobby that inspired his daily toil for more than 11 years. We should probably do the same. But we won’t. The news coverage we’ve been lavishing on R&R readers, however, might be a little less lavish—er, loquacious. After you’ve waded through this posting, you’ll probably be thankful. And so are we—to Mike Rhode. P.S. Gafiate is the verbal buzz word with roots in the fan expression Getting Away From It All, “all” being, usually, all things fannish.

QUOTES AND MOTS “Santorum is more worried about how easy it is to get sex than how hard it is to find work.”—Ted Rall “What we’re getting this year is not a presidential election: it’s an auction.”—John Hightower “I offer my opponents are bargain: if they will stop telling lies about us, I will stop telling the truth about them.”—Adlai Stevenson “Don’t vote. It only encourages them.”—Anonymous

THE ICONIC NICOLE HOLLANDER The Demise In Print of Sylvia ON

APPROXIMATELY March 26, Nicole Hollander started off her blog with a ringing

phrase of just two words: “I quit!” she wrote. “That phrase has been running

through my brain for years now,” she continued, explaining that she was finally

moved to utter it because the Chicago Tribune had dropped her comic

strip, Sylvia, and since she couldn’t read her strip in her hometown

newspaper, she felt the loss. So she’ll give up the print Sylvia but

promised to continue to please her fans by creating an online presence for her

sardonic cigarette-smoking matronly broad. Hollander observed in the same posting that “Dick Cheney received a new heart. Let us hope that it is a generous heart, one that feels remorse and wants to right as many of his wrongs as possible. What do they do with the old hearts? Are they recyclable? Sylvia has retired from her comic strip and Dick Cheney got a new heart! Whew! What a week. “But do not worry!” she went on: “I have 33 years of Sylvia comic strip archives! I’ll be going through them, and every day there will be a strip on the blog which is relevant and probably one you have never seen before.” Sylvia, like most iconic personages in life and literature, began by doing walk-ons in a comic strip that Hollander conducted in the 1970s pages of The Spokeswoman, a monthly feminist magazine that she, as its graphic designer, had transformed from its earlier manifestation as a newsletter. While laying out pages, Hollander sometimes added doodles of a politically incendiary nature, and around 1978, she started a comic strip, The Feminist Funnies. It was in this strip that the character that eventually became Sylvia first appeared. Selections from The Feminist Funnies showed up in Hollander’s 1979 book, I’m in Training to Be Tall and Blonde, and the book’s success persuaded Field Enterprises in 1981 to syndicate Sylvia nationally as a daily newspaper comic strip. Since then, as Hollander observed, Sylvia has never been at a loss for words. Or opinions. And neither is Hollander, who confessed to feeling vaguely uneasy if she doesn’t manage to insinuate an overtly political comment into the strip at least once a week. The strip must, she once said, contain a kernel of outrage, albeit (I say) often subdued in deadpan delivery. Some years ago—in other words, long before the current excitement about abortion—Hollander’s newscaster in the strip, Patty Murphy, reported as follows (the ellipses indicating transition from one panel to another in a sweetly timed sequence): “The state legislature passed a law today ... that would outlaw abortion ... unless the doctor’s life is in danger.” In her insight laden history of her comic strip, The Sylvia Chronicles (2010), Hollander muses about the state of feminism: “When did we get to the postfeminist era? Was I asleep, in a coma, or otherwise engaged? Do we have equal rights, equal pay, equal opportunity in education? Equal professional opportunities? When my local dry cleaner charges the same price to launder and press women’s blouses as men’s shirts, I’ll know we have arrived.” In the mid-1980s or thereabouts, Hollander jumped the syndicate ship and started distributing Sylvia herself. I’m not sure of the details, but from what I’ve gathered, she was reacting to the unfortunate situation in Detroit. The syndicate salesman called on one of the city’s two daily newspapers, and the comics editor there bought the strip but never published it; he probably just wanted to keep it out of the rival paper. That sort of thing went on a lot in those days. Hollander, miffed, withdrew from her syndicate contract and started distributing it herself, reasoning that she could probably avoid such dire Detroitish outcomes if she were doing it herself. Sounds like the sort of thing Sylvia would do. Hollander enjoys the regard of cartoonists as well as that of passionate readers. Said Jules Feiffer: “When the news is distorted, slated, or misreported, that’s what we call it: news. When it is reported truthfully, we label it satire. ... Nicole Hollander has been one of our nation’s leading satirists. This means she is in the business of telling the truth and making it funny. She is right about almost everything. And because she is right and she is funny, she has no power whatsoever. ... She is a radical social critic who is certain that nothing works, and so what? —a revolutionary who believes in the hell with it, I’m going shopping.” Barbara Ehrenreich in the Introduction to Tales from the Planet Sylvia wrote: “What working commentator can confront Sylvia’s range of subject matter—from macro-economics to stretch marks, from foreign policy to kitty litter—without gnawing anxiously on his or her writing instrument? ... her supernatural insight into matters of public policy, her ability to see, as with x-ray vision, through the stupefying drone of media rhetoric.” And there’s more. Herewith—:

Michael Miner at the Chicago Reader: This week Nicole Hollander dropped the second shoe. She announced that she's bringing her comic strip Sylvia to an end in April. The first shoe fell 26 months ago, when her hometown Chicago Tribune canceled the strip, cutting Hollander's income roughly in half. On March 28, I asked Hollander how she's doing. "I'm fine," she said. "I'm in the stage after you ask for a divorce and you feel really terrific." What's the next stage? I wondered. "Sometimes it's a sense of loss," said Hollander, who went through a divorce from Hungarian sociologist Paul Hollander in 1962 after only a few years of marriage. "I remember the stages,” she said. “Not quite as many stages as dying, but it's in there." But Hollander doesn't intend to stop drawing Sylvia altogether, nor does languishing fit into her schedule. She tells me she's been confronting certain personal deficiencies. "I don't know how to embroider or sew," she says. "I worked with a woman from Lill Street. She knows how to embroider and she taught me as much as she could. But I will never learn the womanly arts." She learned what she needed to know. [For a local exhibit,] she just did a drawing of Marie Antoinette and embroidered a great big pimple on her nose. She wrote on the drawing "Marie Antoinette has a pimple on her nose. HEADS WILL ROLL!" "I always hope I'll have a show," says Hollander. "Now that I have time to think of these things, I'm thinking of approaching galleries with this work my house is full of." She recently spent time at Ragsdale working on a graphic memoir, huge sheets of paper she's drawing on in charcoal to remember the life she lived from the age of six to 14 in a yellow-brick six-flat at 3914 W. Congress. "I started doing it in black and white," she says, "but I took a photo on Google maps and blew it up and there was actually a parking space in front of the apartment so I put my father's Hudson in it in color." She's assembling the drawings into strips 16 inches deep and seven feet wide. She's finished five strips so far. The last time I talked with Hollander, in November of 2010, she was bouncing back from the Tribune cancellation and trying to figure out the Internet. The good news was that a young 'net whiz named Alicia Eler had decided to take Hollander in hand. [Her successor], Deanna Trejo, manages the website Eler created for Hollander, BadGirlChats.com, and also Hollander's Facebook page. The other paid member of Team Sylvia is Laura Zinger, a documentary filmmaker whom Hollander calls her financial "strategist," explaining: "Because the blog is not monetized, I have to think of some way to earn money to keep going. And what she helps me do is contact libraries and universities. I give talks and I get paid. It's a mystery to both of us how you get ads [online]. We'll learn it eventually. Laura felt I should tweet. We did that for a while—I would write it and she'd put it up. But that did nothing. "I haven't figured out how to put the cat to work,” she continued. “It's the way I've lived my whole life. A little bit of money comes in every month, from unexpected sources." She mentions book illustrations, an assignment from Lilith magazine when it redesigned, a poster for a Nancy Pelosi event. Hollander is 72 years old, and although Sylvia never ran in many papers, Hollander's been drawing her for more than 30 years; and there are ways to monetize icons. ... "I've been sitting here answering the comments on the blog, which are really touching," Hollander says. "Some people have decided to be in denial, and some are saying they don't see how they can be happy for this. I say I'm retiring and I have the blog and the blog is really satisfying, but I think they're worried they won't have new strips and I won't be commenting on things that are happening right now. My partial answer is that I have 32 years of strips and many of them, unfortunately, are as relevant now as they were then." [Having looked all the way through Hollander’s 1986 collection, The Whole Enchilada, searching for examples to post later, on down the scroll, I agree: 26-year-old Sylvia is astoundingly pertinent.—RCH] She intends to dust off and post those old strips as appropriate. "And if I don't have to do six strips a week, I think I can manage one that is current. You heard it first." When we talked in 2010, we discussed her Wikipedia entry, which was four lines long and didn't even say that Hollander was born in Chicago. On this front, the progress has been astonishing. Her current Wikipedia entry is a thing of beauty, rich in biographical detail, references, links, and even "critical commentary." I ask if Eler put it together. No, she says, it's a guy who lives near Seattle who's a fan. He used to be a senior editor at Encyclopedia Britannica here in Chicago. She's never met him.

***** Here’s Donald Liebenson’s earlier report in the Libertyville Review on the famed cartoonist and feminist icon before we knew Sylvia was ending in print: Sylvia is Hollander's signature creation. Running in more than 30 newspapers across the country, the comic strip is a rarity on the comics pages: woman-drawn with a woman at its center. And what a woman: in a youth-obsessed culture, Sylvia remains as ever a 50-something, chain-smoking, cat-loving, liberal feminist who dispenses cynical, satirical and ironic potshots at political and societal absurdities. As a feminist, Hollander, 72, was born to the breed. When she was about six, her father brought her along when he joined his union, and the women in her family worked when June Cleavers were the norm. "The minute there was a movement, I got it," she said. "It was seamless. The feeling that certain groups in our society were oppressed or cut out of reaching their full potential; I went right from there to women." As a cartoonist, she was a late bloomer. She was 40 when she created Sylvia, who made her inauspicious debut in a feminist newsletter, The Spokeswoman. Hollander had originally envisioned herself as a serious painter probing her "tormented soul." [When she said this, Hollander probably smiled, maybe even chuckled a little as she sometimes does when uttering vaguely self-deprecating humorous asides.—RCH] She became a graphic designer and was charged with making The Spokeswoman look more like a magazine. "I started drawing political illustrations for them," she said. "It was a chance to be sort of a bad girl. I could caricature judges as pigs. I didn't have to be careful." The earliest incarnation of Sylvia appeared there and in a proposed book of cartoons that became Hollander's first collection, I'm in Training to be Tall and Blonde. [A typical Hollander remark. See what I mean by self-deprecating comedic asides?—RCH] The character introduced each chapter. She was depicted berobed, sitting in a chair, her hair in pin curls, and wearing backless Mules. The editors called her Sylvia the Slattern. "I went through the roof," Hollander said, "but I thought Sylvia was a great name. It reminded me of my mother and her friends. I got my sense of humor from her and her interaction with these funny, very quick-witted women." Ironically, Sylvia has always depended on the kindness of enlightened men. When Hollander first pursued syndication, she was told her work was "deep but narrow." "That has always been a problem," she said. "Unless there were men who got my humor, I never would have gotten my first book or into any newspaper." But the times they may be a-changin'. "I received a letter from a 10-year-old boy who said he loves Sylvia," she said. "Maybe little boys today see something (in her) that makes them laugh. Maybe it's that edginess." Sylvia was dealt a setback two years ago when the Chicago Tribune stopped carrying it. Hollander jokes that she is presently doing the same amount of work for about half the income. Expanding her horizons, Hollander started a blog, www.BadGirlChats.com, featuring cartoons, posts, and guest submissions. The blog fosters a sense of community among people for whom Sylvia (and by extension, Hollander) say the things they are thinking but lack the platform to express. Hollander is also working on a memoir, which she developed while in residency at Ragsdale in Lake Forest. Sylvia was originally going to get older, but a funny thing happened. "She was older than me when I started," Hollander laughed. "But I couldn't bear to make her any older. That's something I have control over (unlike myself)." So what would Reagan-era Sylvia say to Obama-era Sylvia? "Isn't it amazing how the same awful things happen over and over again?" Hollander supposed. Take Rush Limbaugh and the recent imbroglio over his intemperate slurs against Georgetown law student Sandra Fluke. The immediacy of the blog allows Hollander to comment on breaking news. In this case, she posted a link to a website mounting a drive to urge sponsors not to advertise on Limbaugh's radio show. When the news serves up the comic equivalent of a 16-inch softball begging to be hit out of the park, does Hollander hear Sylvia's voice in her head demanding to let her comment? "I hear my own voice," she laughed. Now, here is an assortment of Sylvias—after which, we’ll return for an insightful footnit.

ALTHOUGH PRODUCED BY A THOROUGHLY ACCOMPLISHED cartoonist, Hollander’s comic strip betrays a secret shortcoming. You’ll notice in the foregoing culling a preference for rendering her heroine in profile. In the latter years of the strip’s run, Hollander reported that she had, very early on, produced the perfect Sylvia profile. Try as she might, she could not reproduce the perfection perfectly in subsequent renderings. So she stopped trying. Instead, she photocopied the perfectly profiled Sylvia and pasted it onto strips whenever possible. After sticking the photocopy down, Hollander took an exacto knife and performed careful surgery, cutting out a hank of hair in order to put a decorative kerchief on Sylvia’s head or slicing off an earring in order to draw in a newer, more outlandish piece of ear wear. Hollander sometimes committed this “self mutilation” on so many aspects of the original profile that only Sylvia’s nose, eye, and chin remained of the initial perfection. No matter. It was the perfection of nose, eye and chin and Hollander wanted to preserve. And so she did, as we can plainly see among the evidence above.

BADINAGE AND BAGATELLES “Sex after marriage, the old saying goes, has three phases: kitchen, bedroom and hallway. Kitchen sex is the spontaneous type spouses have when they first get together. Bedroom sex is the more routine lovemaking that sets in after a few years. And hallway sex is when husband and wife pass each other in the hallway and say, ‘Screw you.’”—Belinda Luscombe, in Newsweek “I am a hospice chaplain. I visit people who are dying—in their homes, in hospitals, and in nursing homes. What do people who are sick and dying talk about? Mostly, about their families, their mothers and fathers, their sons and daughters. They talk about how they learned what love is, and what it is not. That is how we talk about the meaning of our lives. That is how we talk about the big spiritual questions of human existence. We don’t live our lives in theology and theories. We live our lives in our families. This is where we find meaning; this is where our purpose becomes clear.”—Kerry Egan at CNN.com

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted THE RANKS OF FULL-TIME STAFF EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS have diminished by two with the death of Rex Babin (see Passin’ Through for an Appreciation) and the departure of Tony Auth, the 69-year-old Pulitzer-winning editoonist at the Philadelphia Inquirer, who left at the end of March the paper where he’s been for just weeks shy of 41 years. Auth wasn’t forced out: he took a buy-out. But the buy-out was part of the owner’s effort to trim 37 jobs from the payroll of the Inquirer and its sister paper, the Philadelphia Daily News. Auth told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs that he’d started feeling burned out, doing one cartoon a day, five days a week, for four decades. And a recent illustration job convinced him that he wanted to make room in his life to do more of that sort of work. So when the buy-out offer came, Auth was ready: "It was pretty clear,” he said to Cavna: “I had come to the conclusion that I wanted to move on and, hopefully, grow as an artist. I saw a path I wanted to follow, this buyout came and it seemed like the right time. This has more to do with what I want to do than [the Inquirer’s financial dilemma]." At the DailyCartoonist, Alan Gardner discussed the “uncertain future” of the two Philadelphia dailies: “Currently the two papers and their joint web property, Philly.com, are up for sale and the papers are being combined with editorial separation. Buyouts are being offered to employees with the hopes of trimming the employee count.” The Inquirer’s executive editor Stan Wischnowski put a spin on what was doubtless a purely financial consideration about another staff editoonist: “Tony Auth’s name might be more synonymous with the Inquirer than perhaps any journalist we’ve had. You don’t replace somebody like that. You don’t replace a legend.” After Auth’s departure, Daily News editorial cartoonist Signe Wilkinson is the last staff editoonist in the city. After a couple of suspenseful weeks during which the paper’s management dawdled and pondered while she wondered if she’d still have a job at all, she finally learned that her job was, for the nonce, safe: she was told she’d be appearing in the Inquirer thrice a week in addition to continuing her regular daily gig at the Daily News, five times a week. “It was a huge relief,” said Wilkinson, the first woman to win a Pulitzer for cartooning (in 1992). “It was a terrible, terrible, terrible couple of weeks. So many people’s jobs have been up in the air.” Other staff members “look at you like you’ve got terminal cancer,” she joked. “They touch you on the shoulder. I kept saying, ‘No, no—I’m going to live. I’m alive.’ The only good thing about these past weeks was the amount of support I got from all quarters”—newsroom colleagues, executives and letter-writers who rallied around her. Auth will continue doing editorial cartoons, 2-3 a week for syndication, but he’ll devote more effort to doing animated editoons for the local PBS radio station’s website, NewsWorks.org, where his work will accompany news reports and features about some of the region’s significant stories. He’ll develop depictions of complicated city governance issues and create behind-the-scenes pieces that show slices of life at venerable city institutions, creating “video cartoons” drawn and recorded with an iPad app called Brushes. “He then overlays the video with audio commentary,” Gardner explained. Said Auth: “I’ve been fooling around with Brushes for several months. That’s been a joy! Just using the medium, I’m trying to build time and motion into it. Watching people draw is magic. These videos invite people into the process.” Auth remembered that his job at the Inquirer began with a “weeklong job interview” in 1971: “My task was to attend editorial board meetings, take positions, argue my point of view, win some arguments, and lose others. In short, for a week I did everything a political cartoonist does at a newspaper—except draw cartoons. I lost most of those arguments, but won the job. ... The Inquirer was taking a chance on me. I was working as a medical illustrator in Los Angeles, and I also supplied three cartoons a week to the UCLA Daily Bruin. So the rules at the time reflected that lack of experience.” Writing a farewell to Inquirer readers on April 1, Auth remembered his first editor: “Creed Black was a moderate Republican. He'd not be welcome in today's Republican Party, but that was a long time ago, in what seems like a far away galaxy. Creed would never tell me what to draw, he said, but wanted a choice of drawings to pick from. That led to some game playing by the two of us. If I had what I thought was a really good drawing, and he picked one of the other two sketches I submitted that day, I would show up the next day with the remaining two. If he picked the ‘wrong’ one again, I would only submit the one he'd turned down twice on the third day, and we'd fight about it. I lost a fair number of those fights, but also won my share. We came to an understanding, and by the time I won the paper's second Pulitzer in 1976, I was submitting one cartoon a day just like any regular contributor.” About his stint at the Inquirer, Auth said: “For the vast span of 40 years, I've been in-cred-ibly appreciated. It’s been a great ride. With the possible exception of Herblock's [situation at the Washington Post], there cannot have been a better environment for me to function in," nodding in appreciation to such editors as Creed Black, Ed Guthman, Gene Roberts and Chris Satullo (who is now at the PBS radio’s NewsWorks). “Other cartoonists complain about their editors, for me it was a fabulous environment with lots of freedom. I was never hassled by editors. “Over the years,” he continued, “people have often said to me, ‘You're so lucky, you can work from home.’ Why in the world would I want to work from home, and deny myself the pleasure of working in a building filled with smart, insightful, irreverent, funny, energetic, and engaged people? Colleagues at the Inquirer created an atmosphere of give and take, one where I could show my sketches to the reporters who wrote the stories I was commenting on to get their feedback; an environment that was stimulating and nurturing, and that still exists at the paper.” Looking around, Auth is saddened to see the gradual disappearance of the artform he spent his life practicing: "It's just sad to see such a historically wonderful genre kind of disappear," Auth told Cavna. "I think newspapers are to some extent responsible because they've always [divided] our profession over seriousness versus laughs. ... For as long as I've been doing this, there’ve been two divided camps." He

criticized such editorial packaging as the New York Times' old

"Laugh Lines," which he says never picked the best editorial

cartoons. "They printed me once in a while, but never the good ones,"

he says. "They'd run four cartoons with

COLUMBUS DISPATCH REPLACES STAHLER Nate Beeler, erstwhile editoonist at the Washington Examiner, is leaving to take the same job at the Columbus Dispatch, where Jeff Stahler worked until forced to resign last fall over a plagiarism allegation (see our story at Opus 291). Beeler has been at the Examiner since it started in 2005, working first as a page designer. “I cut my teeth as a cartoonist here when it was still fighting for a foothold in D.C.,” he told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs. “I’ve seen other employees come and go in the newsroom, and I kept plugging away at my drawing table. However small it was, it feels like I had a hand in building the Examiner into the Washington fixture it is today, which makes my departure a bit bittersweet. I’ve always felt incredibly privileged to draw editorial cartoons in the nation’s capital, and I will miss the energy of its politics — no matter how ridiculous it is at times.” But when the Columbus Dispatch beckoned, Beeler didn’t hesitate. “I couldn’t say No,” he said. “It’s the number one newspaper in Ohio, and Columbus is both the state capital and my hometown. My parents live there, and this was an opportunity for my son to grow up with his grandparents being a big part of his life.” “We were fortunate to have a strong pool of applicants for this position,” said Dispatch editor Ben Marrison. “Nate’s artistic and journalistic talents made him our top choice.” Beeler begins his work at the Dispatch within the month. His editors at the Examiner bade him adieu with a notably gracious memo: "Nate joined the Journal Newspapers in 2003, a year after his graduation from American University, and stayed with the paper when it became the Washington Examiner in 2005. He has been turning out five cartoons a week, and we gave him prime real estate – half of page 2 – so readers would be sure to enjoy his work as much as we did. We've also featured his cartoons on our website and mobile app, and sent them to thousands of email subscribers. Only 31, Nate is a fine draftsman, a natural wit, and a first-rate journalist. And while each of his cartoons has a distinct point of view, he is no ideologue. We may have endorsed Romney for the Republican nomination, but Nate subsequently drew him as Frankenstein, proving emphatically that he is no slave to editorial policy." Among other awards, Beeler won the 2009 Thomas Nast Award from the Overseas Press Club and the 2008 Berryman Award from the National Press Foundation. The judges for the 2009 Nast award said: “Nate Beeler’s entries stood out for their powerful and vivid composition that brings the message home regardless of whether the cartoon centers on a conversation or a visual punch line. Notable for his use of color and for meticulous art work that, in the words of one of his editors, ‘treats each cartoon like a painting.’”