|

||||||||

Opus 287 (On the Cusp of Christmas 2011;

December 20). Cahoots, still celebrating the Year of the Rabbit, joins me in

wishing you a Merry Christmas—with all the trimmings, as you can see. Christmas is capitalism’s secular religion, in overt recognition of which, we proclaim the instrument of capitalism, money, the god in whom we trust by saying so on every denomination of our coinage. Because we are all capitalists, we should feel no hesitation in wishing each other a “merry Christmas” when the anyule occasion arises. And so I feel no hesitation. When I say “merry Christmas,” I’m not thinking of mangers and stars of Bethlehem. I’m thinking of Charles Dickens and a reformed Scrooge and old Fezziwig and Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim and the Christmas goose. Goodly fellowship and good intentions and good food. And songs—the spirited old carols of my youth and, still, of my dotage. I’m thinking of Christmases past, and the memories heap up and make each year’s holiday a nostalgic visit to family and to friends of yore. That’s a merry Christmas: in every Christmas Present, Christmases Past. That’s Christmas in a capitalist society. The anyule event of a wholly secular religion. And if some capitalists find another religion lurking in the holly and the ivy, that’s fine; that’s their business, their preference, their faith. Live and let live, I say. And if Bill O’Reilly wants to start another crusade, this time about St. Valentine’s Day, I say let him.

BUT WHILE I’M WORKING UP to that, we have a heap of book reviews this time, too late, alas, to help your spouse find a suitable gift for you, but not too late for you to make good use of the money your mother-in-law gave you for Christmas (because she was afloat on the capitalist wave of the occasion, mind you). After the briefest nod in the direction of some of the news of the day that gives us fits and a pause at a magazine cover that’s an editorial cartoon, we review the following books, in this order:

African-American Classics Dr. Seuss & Co. Go To War Cartoon Marriage: Adventures in Love and Matrimony by The New Yorker’s Cartooning Couple I Thought You Would Be Funnier What I Hate From A to Z Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon (comic book): The Complete Series, Volume One Milton Caniff’s Male Call: The Complete Newspaper Strips, 1942-1946 Setting the Standard: Comics by Alex Toth, 1952-1954 Alex Toth: Last Chance Genius Isolated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth The Quality Companion Will Eisner Conversations Walt Disney’s Donald Duck: Lost in the Andes De: Tales: Stories from Urban Brazil Nuts: A Graphic Novel The Adventures of Herge (in graphic novel form)

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits Despite webrumors that the charge was dropped against Susie Cagle for “failing to leave the scene of a riot” as police attempted to mop up Occupy Oakland, as of December 11, she’s still charged according to her father, editoonist and syndicate mogul Daryl Cagle, who attempts to correct the web at his blog at Cagle.com. ... The newspaper Sunday supplement Parade magazine had no cartoon in either its December 11 or 18 issues; the “Cartoon Parade” has been staggering lately, sometimes with only one cartoon, typically about the size of a postage stamp. Now, it looks as if it may be gone forever. But we hold out hope for a Merry Christmas—i.e., the next issue. In Time magazine’s round-up of “the best in culture of 2011,” Kate Beaton’s book of cartoons, Hark! A Vagrant, ranked seventh in the top ten non-fiction books; Daniel Clowes’ graphic novel, The Death-Ray, tenth. This is the first time, methinks, that cartoonists’ books have made a MSM’s top ten. This “cultural report” is provocative in a probably unintended way. “Culture,” to Time, means mostly tv and movies: tv and movies get 3 pages each; books, pop music, and technology, 2 pages each; games and theater, one page each. By this measure, “culture” is actually just “popular culture”; it doesn’t include art (painting, sculpture, etc.), religion, architecture, politics, mores, custom, or any of the rest of the traditional accoutrement counted as part of a society’s culture.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS Interviewed at CBR-tv about her new book, Malibu Cheesecake, Olivia said she’s been coming to San Diego Comic-Con for 25 years because pin-up artists have no other natural “home.” “There’s really no place for me,” she said, “—all my friends are there. There’s a place in comics for pin-ups.” But comic-cons have some strange rules. Zombies can be disemboweled at one booth, but at the next, aereolas are forbidden: “They’re dangerous,” Olivia said with a puzzled grin. She has drawn the full-page pin-up in Playboy for maybe 10 years. She goes to see Hef once a week, and Hef writes the captions for her pictures. Sometimes she tells him a caption isn’t funny. But that’s okay: “Sometimes he tells me the picture isn’t sexy,” she said.

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted As Newt takes

his turn at the head of the pack of the Grandstanding Obstructionist

Pachyderms—where he will be, for a short time, conspicuous enough to attract

all the detractors in the woodwork, whose detractions will effectively destroy

his popularity and, ipso facto, his candidacy—The Week magazine

arrived in our mailbox with the cover you see at your elbow. We’re posting this

colorful cover not so much because I agree with its message (I do, As for the GOP practice of destroying its candidates by making their advocates more knowledgeable about them, it is, without a doubt, the best way of advertising that the Tea Baggers and the rest of the loud-mouthed minions of the Right are, fundamentally, ignorant. They are enthusiastic supporters of one candidate after another only as long as they remain ignorant of the candidate’s character and credentials. In their ignorance lies the power of the candidates, one at a time.

THE SPOUSE LIST: PART TWO, TOO LATE Now, For Auntie Em HEREWITH, THE SECOND INSTALLMENT of our anyule list of books you might want for Christmas. By now, it’s probably be too late to use this list as a prompt for your spouse, but it’s not too late to use it yourself as you try to decide how to spend the money your favorite aunt gave you for being good all year. Some of the ensuing reviews are quite short because sometimes this department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we sometimes do here, starting with—:

African-American Classics By Various 144 7x10-inch pages, color; Eureka Productions paperback, $17.95 AN EXTRAORDINARY book in an extraordinary (and lamentably unheralded) series of graphic novels, this is the 22nd volume in Eureka Productions’ Graphic Classics, which includes titles that adapt to the visual form the work of Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, Louisa May Alcott, Oscar Wilde and many other well-known authors. In this volume, all the stories are written by African American authors and drawn by African American cartoonists/illustrators. Among the former, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charles Chestnut; among the latter, Glenn Brewer, John Jennings, Keith Mallett, Shepherd Hendrix. In all, about two dozen stories and poems; the stories vary in length from 3-4 pages to 15-20. Kyle Baker moodily illustrates “On Being Crazy” (1907) by W.E.B. DuBois on the craziness of racial bigotry. “Two Americas” (1921) by Florence Lewis Bentley, about black and white soldiers in the American army in World War I, is drawn by Trevor Von Eeden, whose style here is more comfortably relaxed than the stiffer manner he used early in his superhero comic book career. It’s a delight to see Milton Knight with his comedic extravagance on Zora Neale Huston’s humorous “Filling Station” (1930). Leila Amos Pendleton’s “Sanctum 777 N.S.D.C.O.U. Meets Cleopatra” is drawn by Kevin J. Taylor, notable in the past for highly erotic graphic novels such as NBM’s Girl. The book concludes with six pages of biographical information on the writers and artists. Eureka’s production standards maintain the highest quality in reproduction, and I have no explanation at all for why the books produced by this publisher aren’t on everyone’s shopping list—at this season and all others. For the complete list of titles, visit graphicclassics.com.

Dr. Seuss & Co. Go to War Edited by Andre Schiffrin 280 9x9-inch pages, b/w; 2009 New Press hardcover, $21.95 INTENDED AS A “COMPANION AND SEQUEL” to Dr. Seuss Goes To War, a 1990s collection of Theodor Geisel’s World War II editorial cartoons, this volume includes the political cartoons of other cartoonists who drew occasionally for PM, the liberal newspaper founded in 1940 by Robert Ingersoll, an editorial genius who’d worked at The New Yorker and distinguished himself as an editor at Time, Fortune, and Life. Although most of the cartoons herein are by Dr. Seuss, Eric Godal also appears often, particularly at the close of the War, and, surprisingly, so does Saul Steinberg, frequently with a comic strip ridiculing Hitler. Other cartoonists include Melville Bernstein, Daniel Fitzpatrick (the grim grease-crayon expert who made his name at the St. Louis Post Dispatch), Matt Greene, John Groth, Leo Hersfield, Louis Raemakers, Arthur Szykk, Carl Rose (famous for his New Yorker cartoon in which a child at table is saying to her mother, “I say it’s spinach and I say to hell with it,” Rose was possibly the most prolific book illustrator of his generation), Mischa Richter (whose style had not yet matured), and, astonishingly, Al Hirschfeld (albeit with only 2-3 cartoons). Schiffrin, who, as a founding director of New Press, is responsible for the publication of Studs Terkel’s The Good War and Art Spiegelman’s Maus, provides an array of lucid introductory material about PM (which for a long time accepted no advertising and was rescued by millionaire Marshall Field, who also started the Chicago Sun), the War, the cartoonists, and the issues they dealt with in their cartoons, the targets of which have otherwise become over the years too obscure. The book is organized topically (“Leading Up to the War,” “The Home Front,” “The War Begins,” and so on) and the cartoons are arranged chronologically (and dated) within each chapter. A bibliographically meticulous production, the volume ends with a chronological list of the cartoons, their cartoonists, and dates of publication, plus the titles of recommended reading, annotated, and a website offering more information on cartoons about the Holocaust, other than PM’s: wymaninstitute.org.

Cartoon Marriage: Adventures in Love and Matrimony by The New Yorker’s Cartooning Couple By Liza Donnelly and Michael Maslin 300 8x8-inch pages, b/w; 2009 Random House hardcover, $24

I Thought You Would Be Funnier by Shannon Wheeler 120 9x9-inch pages, b/w; Boom! Town paperback, $19.99 BETTER KNOWN, perhaps, for his Too Much Coffee Man, Wheeler also does single panel gag cartoons that often appear in The New Yorker. This volume collects, at the rate of one per page, many of the latter and some that have appeared, probably, elsewhere. Dan Pirarro of Bizarro fame supplies the Introduction, which he begins by asserting the primacy of the medium: “For my money, no graphic art form says more about human creativity than the single panel comic.” And he proceeds to make his case by observing, first, that cartoonists who have panel cartoons like Family Circus or Dennis the Menace have the advantage in making jokes that is inherent in the personalities of their continuing cast. Comic strip cartoonists have another advantage: they have space in which to build to a gag. “But in the one-off-single-glimpse-out-of-nowhere cartoon,” Pirarro continues, “all of that must be done in a few words and a single momentary glimpse in time. ... It is to our society’s great shame that so few venues remain for this kind of [superior] humor. ... People like Shannon Wheeler are paupers as a result.” Pirarro doesn’t say that in a good single panel cartoon, words explain the picture and vice versa, thereby decoding what is at first glance a visual mystery; and with the mystery solved, laughter blurts out. He doesn’t say that, but he means it. A disturbing number of Wheeler’s cartoons are like most cartoons in The New Yorker: they barely need the pictures. The captions alone are comedy: “A memoir should not be about writing your autobiography.” “If only I’d started procrastinating last week.” But in many others, the mystery of the picture is solved by the caption beneath it, as in our examples, culled from the book and posted just before this entry.

What I Hate from A to Z By Roz Chast 66 7.5x9.5-inch pages, b/w; Bloomsbury, $15 ON THE COVER of this book is a version of Edward Munch’s “The Scream,” rendered by The New Yorker’s Chast, who is one of the magazine’s stable of cartooners who don’t draw well. In Chast’s case, lame artistic ability is compensated for by verbal hilarity. Each letter of the alphabet is represented in a two-page spread: text on the left-hand page, one of Chast’s “drawings” on the right. She explains the concept for the book in an opening salvo that recommends an antidote for sleeplessness: pick a category and list one thing in it for every letter of the alphabet instead of lying there with your thoughts “running around pointlessly like overtired, sweaty, cranky children.” One night, she continues, “I though about rooftop swimming pools filled with heavy, heavy water; the age and possible decrepitude of the bridges and tunnels that subway trains ran over or through; the continued existence of my appendix; wires in the walls; our boiler; the person my parents knew who had been killed by a flowerpot falling out of a window; various upcoming medical exams; and other things. At some point, I wondered whether I actually had an aversion for every letter of the alphabet. It turns out I did.” And this book is the result. Introducing the letter B, which she illustrates with a picture of balloons at a party, she writes: “Many terrible things begin with B: bears, blindness, boilers, bats, bridges, and brain tumors. But no one brings any of those things to a party to up the fun quotient. When I look at a balloon, all I see is an imminent explosion. Where’s the fun in that?” Elevators, she says, are “the perfect storm of claustrophobia, acrophobia, and agoraphobia.” And she accompanies this with four panels illustrating: “You can get stuck by yourself ... You can get stuck with a crowd ... You can get stuck with a psycho ... And then there’s the obvious”—the picture shows the cables that hold an elevator up breaking. I enjoy this book more than most Chast cartoons. Illness: “The main thing about illness is that you don’t know which way it’s going to go. When I’m sick, I always wonder: Is this a cold? Or is it an incurable malady I picked up the other dak when I rode the subway and held onto the pole and then bought a bag of mini-pretzels that I ate without first washing my hands?” The picture shows a guy looking into the mirror which reveals that his face has broken out in postules of the plague.

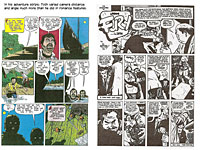

Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon: The Complete Series, Volume One By Milton Caniff; edited by Dan Herman, publisher 256 7.5x10-inch pages, color; Hermes Press hardcover, $49.99 THE NEXT VOLUME in this Hermes Press series will probably reprint the Harvey Comics Steve Canyon, which reprinted the earliest years of the newspaper strip. This volume, however, consists entirely of the comic book stories written and drawn expressly for Western/Dell, all seven issues that were published in the Four Color series from 1953 (No. 519) through 1959 (No. 1033). In these 32-34 page stories, Steve is back in the Air Force, and by the last one, he’s the commanding officer at Big Thunder Air Force base, which is where he’d be seen as impersonated by actor Dean Fredericks on the tv “Steve Canyon,” which ran through the 1958-59 season only. The quality of reproduction is as high as we can expect when the source material is the comic book pages themselves rather than original art (which is doubtless long lost). My only quibble with the publication is that the issue dates of the comic books are not given on the Contents page or on the first page of each story; they are cited, however, on the indicia page of the volume. Many Caniff fans have scoffed somewhat at the Dell Steve Canyon because the stories are not written and drawn by Caniff. And while that is generally true, it’s not entirely true. The first Dell story was probably written by Caniff, as John R. Ellis says in his Introduction; and judging from Steve’s occasionally snappy patter and shorthand slang in this story, Ellis is surely correct. And Caniff undoubtedly drew Steve’s face in all the stories; and he may have tinkered with other faces and visual details if the spirit moved him and he had the time (he was, after all, simultaneously producing the newspaper strip). Ellis says the first story was drawn (except for Steve’s face) by William Overgard, a life-long fan of Caniff’s and a protégé since his teens, who by this time had drawn a couple weeks of the newspaper strip when Caniff was too ill to work (in February and September 1952). By the December 1953 publication of the first Dell book, Caniff had developed a way of working with assistants. After suffering two debilitating illnesses in the same year, Caniff finally took on a full-time assistant, Richard Rockwell (nephew of famed illustrator Norman), who penciled the strip for Caniff’s inks. Rockwell’s work began appearing early in 1953; by the end of the year, Caniff was fairly adept at insinuating his distinctive visual mannerisms into the work of another artist. The other six Dell Canyon stories were drawn by Ray Bailey, who had assisted Caniff during the World War II years: he never worked on the Terry strip, but he helped with promotional drawings and finished art for military unit insignias, of which Caniff did a great number in those years. Bailey also helped occasionally on Steve Canyon, drawing backgrounds chiefly. Paul S. Newman, who holds the Guinness world record for writing the most comic book stories (4,100, totaling an estimated 36,000 pages), wrote the stories Bailey drew. In his brief Introduction, Ellis, who is spearheading the effort to restore and re-release the tv “Steve Canyon” (visit stevecanyondvd.blogspot.com), adds to Caniff lore with comments on various aspects of the Dell stories, quoting correspondence and noting visual oddities.

Milton Caniff’s Male Call: The Complete Newspaper Strips, 1942-1946 By Milton Caniff; edited by Dan Herman, publisher 144 9x12-inch landscape pages, b/w; Hermes Press hardcover, $39.99 THE MOST COMPLETE reprinting of the World War II weekly comic strip that Caniff produced for military base newspapers and magazines, this volume includes not only the Male Call strips, but the so-called “Burma strips” that inaugurated the idea of a morale-boosting comic strip featuring a sexy camp follower who reminded soldiers of what they were fighting for, the Male Call strips that were rejected for being too sexy, and many of the drawings of Male Call’s heroine, Miss Lace, that Caniff did for various military publications in the years since she officially retired in 1946. The quality of reproduction, from proofs at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University, is very high, and the strips appear in generous dimension, only two to a giant page, with dates of release through the Camp Newspaper Services, the military syndicate that distributed the feature. The

book’s other supreme virtue is that it commences with a lengthy Introduction by

Yrs Trly, That Dear Sweet Boy We All Know and Love, R.C. Harvey. The essay is

actually pieced together from the pages of my Caniff biography, Meanwhile,

and it gives the whole history of the strip, from Caniff’s earliest exploration

of the possibility for doing such a feature through its run and the complaints

and plaudits the strip earned to its final days. The mystery of the “Burma

strips” is also explained. At first, Caniff’s moral-booster was entitled Terry

and the Pirates and consisted of extra-continuity episodes he drew,

concentrating on the blond bombshell of the syndicated version. But one of Terry’s client newspaper publishers objected to the appearance in a nearby base

newspaper of a strip he was paying for exclusive rights to publish; so Caniff

retired Burma and The Introduction is accompanied by numerous illustrative materials, many of them never before published. In an Afterword, Harry Guyton, Caniff’s nephew and CEO of the Caniff Estate, recalls visiting his famous uncle while he was growing up and, later, when he was in the military himself.

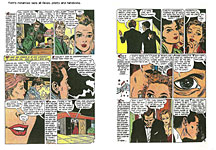

Setting the Standard: Comics by Alex Toth, 1952-1954 Edited by Greg Sadowski 432 7.5x10.5-inch pages, color; Fantagraphics paperback, $39.99 Alex Toth: Last Chance 160 8.5x10.5-inch pages, b/w; Pure Imagination paperback, $25 Genius Isolated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth Edited and written by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell 328 9.5x13-inch pages, b/w and color; IDW Library of American Comics, hardcover, $49.99 THIS TRIO OF TOMES proclaims like nothing else that 2011 was a good year for fans of Alex Toth. By the period covered in the Fantagraphics volume, Toth had developed his distinctive storytelling mannerisms but he had not yet evolved the simplified stylistic drawing tropes for which he is renowned. Over half of the 60 or so tales herein are romances; the rest are science fiction, horror, crime, and war. For those in the latter groupings, Toth emphatically varied camera distance and perspective for dramatic impact. In the romances, Toth habitually focused on formula beautiful faces for the women and on handsome chiseled profiles for the men, deploying close-ups sometimes so tight that only a giant eyeball is visible.

The book begins with an insightful 32-page interview with Toth, conducted by Bill Spicer and Richard Kyl in the summer/fall of 1968 and illustrated with snippets from the work of artists Toth admired. Toth counts as major influences Noel Sickles (after Toth learned that Milton Caniff’s chiaroscuro technique was inspired by Sickles) and Harvey Kurtzman, who thought in terms of pictorial continuity—telling stories through pictures “flowing through the camera.” Typically, Toth’s storytelling relied upon the traditional grid of panels: “I liked the challenge of working within a fixed format,” he said. “A movie screen doesn’t change its shape, scene to scene, and I didn’t think the size or shape of comic panels necessarily had to change either. ... More important to me is what the artwork does within the frame, not the frame’s size or shape itself.” Believing that comics are essentially a visual medium, Toth looked for minimal verbiage in the stories he drew, but he also respected the writer’s contribution. “As artist, I weld pictures to words to build the framework for a strong visual story. ... The artist is responsible for ‘plussing’ a script and editing it, if need be, to make it work for picture continuity, for an action strip ought to have action and not embroidered phrases filling up all the panels.” About action, Toth said it “should be like the point of impact when a bag full of glass is dropped—angles, not curves, jaggedly exploding in all directions.” Action is masculine, angles; curves are feminine. After doing his bravura one-page continuing adventure strip, Jon Fury, for a weekly army newspaper while in the military in Japan in 1955, Toth would have loved to have gotten it syndicated, but syndicates were no longer buying adventure strips. So he returned to comic books.

THE PURE IMAGINATION BOOK offers 8 stories from 1957-1963, six of them Westerns. Several of the stories display distinctively Sicklesan techniques, but in one of them, Toth uses a felt-tip pen, etching the unvarying line that marks his later work. The artwork is produced from printed comic book pages from which all color has been bleached, then the remaining black linework retouched, a painstaking process known as “Theakstonizing” (named after PI’s publisher Greg Theakston, who developed it). Fine lines are often lost in this process, or matted together in unsightly blotches. But the black-and-white printing of this volume emphasizes the dramatic visual role of solid black in Toth’s work and makes these stories a pleasure to watch. Incidentally, I don’t think Theakstonizing is used much anymore anywhere except at Theakston’s Pure Imagination studio. When he developed the process a couple decades ago, it was by far the least expensive way to reproduce vintage comic books; once the color was bleached out of actual comic book pages and the black lines restored, the artwork could be photostatted and re-colored, producing a passable facsimile of the original publication. But digital sophistication has now become the least expensive—and most accurate—way of reincarnating Golden Age funnybooks; so Theakstonizing is fading away. Or so it seems to me.

THE IDW BOOK is the piece de resistance—a gorgeous and lavish production in the IDW tradition that we have come to admire and expect. The first of a monumental three-volume biography of Toth, it covers his life and art through about 1960, when he angrily stalked out of Western offices in Los Angeles and began concentrating on animation. Mullaney and Canwell spent over a year conducting interviews with dozens of Toth's peers, friends, and family members. To quote from the accurate description at the IDW website: “The book has been compiled with complete access to the family archives, and with the full cooperation of Toth's children. Toth fans and friends throughout the world have loaned original artwork reproduced in the entire series. Included are many examples of Toth's art, from complete stories to rare pages, as well as an unfinished and unpublished penciled story from the early 1950s! The tome covers his earliest stories at DC in the 1940s, his defining work at Standard, his incomparable Zorro comics in the 1950s, and a special section collects, for the first time, the complete Jon Fury pages that Toth produced while in the army, a section that alone is worth the price of admission.” Mercifully, not much of Toth’s juvenilia is on display herein; apart from a few samples of his earliest published work (all of thoroughly professional caliber), the visuals begin in earnest with 1948/49 covers he did for DC Comics, most spectacularly, those depicting Johnny Thunder on All American Western. Several complete stories are produced from the original artwork (including one that also appears in the Pure Imagination book; and a few that are published in the Fantagraphics volume); much of the original art herein consists of individual sample pages isolated from the stories of which they are a part. Among the completed stories is “Battle Flag of the Foreign Legion” (from Danger Trail No. 3, November 1950), which the editors call “one of the most influential comic book stories published in the early 1950s.” A tale of cowardice and courage, the narrator is the flag. Three of the 8 pages are reproduced from original art; the rest, from published pages of the comic book. The artwork is arranged in chronological order, accompanied by a biographical narrative and analytical text that is generously laced with photographs and out-takes from Toth work described in the prose. The book ends with samples of Toth’s comic book adaptations of tv series for Western/Dell, including the 24 illustrations Toth did for the 1959 children’s novel based upon “Maverick” starring James Garner. And a Toth bibliography fills the last five pages with a year-by-year listing by first publication dates. Although the list appears to be exhaustive, I can’t find two of the stories in the Pure Imagination book; maybe I’m not looking in the right place. But that’s a minor quibble of nearly massive inconsequence in the face of the joys and pleasures that abound in this volume.

The Quality Companion By Mike Kooiman and Jim Amash 288 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w with a color section; TwoMorrows paperback, $31.95 THIS LANDMARK VOLUME is, as the publisher claims, “the first dedicated look at the prolific Golden Age publisher that spawned a treasure trove of beautiful art and classic characters.” The Quality line was perhaps the most sophisticated of the Golden Age comic books. As a kid, I read with fascination the adventures of Doll Man, the Blackhawks, Plastic Man, the Spirit, Manhunter, and the Human Bomb—awed by the high quality of the drawings but not quite appreciating the kinds of stories and art on display. I got Superman: invulnerable guy in blue tights fights crooks. I got Captain Marvel: invulnerable guy in red tights fights crooks. But Quality’s Rusty Ryan baffled me; what are he and his band of comedic oddballs up to, wandering around the world? TwoMorrows profiles all the Quality characters: in addition to the ones I just named, Black Condor, the Barker, Captain Triumph, the Jester, Kid Eternity, Lady Luck, Jack Cole’s comedic Midnight, the Ray, and a few dozen more. The book includes a 25-page history of Quality, during which, for the first time, we learn that the publisher, Everett “Busy” Arnold—whose nickname, Busy, no one has, heretofore, decoded—acquired the moniker as a kid because he was “fidgety,” his son explained: “He never sat still.” We also learn that Quality Comics is not the official, legal name of the company: it was at first Comic Favorites, Inc.; then, Comic Magazines, Inc. The Quality history is followed by an abridged DC Comics history because DC acquired the Quality characters when “Busy” went out of the business and, at various times, revived some of them. Next comes short biographies and “comicographies” of the artists and writers (in alphabetical order)—such legendary luminaries as Lou Fine, Reed Crandall, Jack Cole, Matt Baker, Chuck Cuidera, Will Eisner, David Berg, Dick Dillin, Gil Fox, Fred Gardineer, Paul Gustavson, Bob Powell, Bill Ward, Klaus Nordling, and Chuck Mazoujian (to name a few)— followed by detailed profiles of the characters themselves, giving short bibliographies for each (also in alphabetical order). Many of the artist bios are cross-referenced to past issues of TwoMorrows’ Alter Ego in which interviews with them have been published. The book concludes with lists of Arnold’s various publications, including comics, supplemented by another list that details the content of the major Quality titles (Feature Comics, Smash, Crack, Hit, National, Military [but not, oddly, its continuation as Modern], and Police), issue numbers and dates of characters’ appearance, and the names of those who produced each feature. In the Feature Comics listing, for instance, we learn that Blimpy the Bungling Buddha appeared in Nos. 64-133, January 1943 - April 1949, by Seymour Reit and Al Stahl with Jack Cole doing it Nos. 76-77. Other lists give the first appearances of characters and the number of issues they appeared in. Photographs and out-take illustrations appear throughout, on every page. If this isn’t an encyclopedia of Quality—comprehensive in every conceivable detail—it comes so close that omissions, if any, are probably so irrelevant as to be incongruous. The bonus of bonuses is new with this addition to the TwoMorrows Companion series: this one opens with a 40-page section that reprints, in full color, several key stories from rare collector’s 1940s comics featuring the Ray, Phantom Lady (the more modestly attired specimen), the Black Condor, the Human Bomb, Uncle Sam, Midnight, Firebrand, Wildfire, and Madam Fatal. This section is alone worth buying the book. Individual entries in the volume set forth a wealth of trivia. Under Plastic Man, we learn that his bumbling sidekick Woozy Winks, who debuted as a petty criminal in Police No. 13 eventually to be reformed by Plastic Man, had acquired invulnerability and immunity from pain early in his career. I don’t think I ever knew that. In his earliest appearances, Woozy is referred to as “the man whom nature protects”; he’s the reverse of accident-prone, and because he never suffers any painful consequences, he thinks he’s immune to pain. But I always thought it was just in his head, not all over his body. I knew, however, that in National No. 18, Uncle Sam takes off to fight the Japanese who are bombing Pearl Harbor; Lou Fine’s splash page appears in the book in the Uncle Sam section. Just a patriotic effusion, you’d say. But National No. 18 had a December 1941 cover date, which meant it hit the newsstands in late October or early November—well before December 7, the day that lives in infamy because that’s when the Japanese actually bombed Pearl Harbor. The story carries Will Eisner’s byline (despite Lou Fine’s artwork), and I asked Eisner one time what went through his mind on December 7. Here is an actual event that the comic book seemed to have anticipated by more than a month. Surely, he must’ve been astounded. Oddly, he couldn’t remember having any deja vu sensations at all. Nothing. Maybe not so odd. Uncle Sam was battling spies and saboteurs all over the place in those pre-war years. He even went to the Philippines to help forestall an invasion. Maybe the National Pearl Harbor story, which Eisner must’ve written in August or September, was simply too distant a memory, or it was just one of so many pre-war tales he’d conjured up that year that he couldn’t distinguish it in his memory from any of the others. Dunno. But the TwoMorrows book is a treasure and a delight.

Will Eisner Conversations Edited by M. Thomas Inge 260 6x9-inch pages, 14 pages of b/w illustrations; University Press of Mississippi, $25 in paperback; $65, casebinding THE EIGHTEEN INTERVIEWS in this volume are dated from 1965 until 2004, and the interviewers include several noted scholars and/or practitioners of the craft—John Benson, Dave Sim, Jerry DeFuccio, Cat Yronwode, Ben Schwartz, Stephen Bisette, Tom Heintjes, and Danny Fingeroth, to name a few, and moi. Among the interviews we can find what is perhaps the most celebrated of Eisner’s utterances on comics: “My interest always was, from the very earliest days, in extending the medium as far as I possibly could.” For a detailed albeit short discussion of just how he did this, you should probably dash right out and buy a book of mine, The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History, in which I spend an entire chapter discussing how Eisner extended the art of the medium. For a longer discussion of how he advanced the artform, you need Tom Inge’s book—or one of Eisner’s, Comics and Sequential Art. Among the pieces in the book is a 1990 essay by Eisner himself. Written for the New York Times Book Review, it’s an autobiography in which the author manages to get several key dates of his career wrong—Eisner and Jerry Iger started their comics production company in 1936, not 1937; The Spirit debuted in June 1940, not 1939. He correctly observes, however, that “the great breakthrough that enabled comics to emerge as literature came with the ‘underground comics’ of the politically and socially explosive 1960s.” One of the best and shortest articles is the book’s first by Marilyn Mercer, who worked for Eisner from 1946 to 1948 along with Jules Feiffer. “As I remember it,” she says, “I was a writer and Jules was the office boy. As Jules remembers it, he was an artist and I was the secretary. Will can’t really remember it very clearly. It is his recollection that Jules developed into an excellent writer and I did a good job of keeping the books. Neither one of us could, by Eisner standards, draw.” She goes on to report on her 1965 conversation with Eisner, reviewing his career, creating thereby the necessary foundation of elementary facts about him that are subsequently illuminated by the rest of the interviews. My interview with Eisner took place in February 1998 in his studio in Tamarac, Florida. We talked for several hours, including lunch, but I didn’t have a tape recorder running all that time. At one point, Eisner said, “You really should be recording all this.” I hadn’t been taping anything because I wanted to luxuriate in a sort of free-wheeling bull session with one of the medium’s founding masters on whatever topics cropped up as we meandered through a conversation. Subsequently, I taped the portions of our talk that focused on instructional comics and on the graphic novel and the future of comics. These interviews appeared in Cartoonist PROfiles, Nos. 131 and 132, September and December 2001. Eisner was intrigued by my wanting him to talk about instructional comics: “Not much has been done on that part of my career,” he said. Inge lightly edited and used the interview on the future of comics, that part of the discussion that deals with marketing graphic novels.

Walt Disney’s Donald Duck: Lost in the Andes By Carl Barks 240 7x10-inch pages, color throughout; Fantagraphics hardcover, $24.99 THE “SQUARE EGG STORY,” to which the title of this tome refers, may be the most celebrated of Barks’ Duck oeuvre—it was Barks’ favorite—and now we have it between the covers of a hardbound book so it’s not likely to get lost in comic book storage boxes (where both of my reprint copies languish). The first of Fantagraphics’ Carl Barks Library reprints, this volume includes three other of his one-shot issue-length adventure yarns (“The Golden Christmas Tree,” “Race to the South Seas,” and “Voodoo Hoodoo”) and nine of the 10-page stories from Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, all from 1948-49, by which time, Barks had reached a “peak period” (the FantaCatalog avows) in his artistic career. In addition to the stunning reprints (the color pages on matt-finish rather than garish glossy paper re-create the visual sensation of the comics’ initial publication when I first encountered them as a mere broth of a boy), the book concludes with a section notes on the stories by an assortment of scholarly Barks aficionados writing about their favorite stories (Alberto Beccatini, R. Flore, Craig Fischer, Jared Gardner, Leonardo Gori, Rich Kreiner, Stefano Priarone, and Francesco Stajano). And in the introductory biographical essay, Donald Ault quotes Barks’ explanation for why Donald Duck seems such a complex personality—flighty and bumbling and forever exasperated and frustrated in the 10-pagers but resourceful and dedicated and mostly successful as an adventurer in the long stories: for Barks, Donald was an “actor” who played “roles” in the stories, changing his personality to fit the parts he was playing. Priarone sees “the square egg story” as an allegory about conformity: Plain Awful, the South American valley in which Donald and his nephews find the square eggs, is populated by square people who “are unable to conceive of, or, indeed, accept, any shape other than a square,” and when the nephews blow round bubbles with their bubble gum, they are condemned to a life of hard labor in the stone quarries. Through a ruse, they save themselves by blowing square bubbles and escape the valley. But I’ve never understood the tale as a cautionary on conformity. Within the evils of conformity lurks another kind of narrow-mindedness akin to all sorts of prejudices, racial and all the rest, but particularly racial. The Plainawfulians are prejudiced against anything different—anything not square. Their squareness (in both figurative and literal senses) chokes off all diversity and initiative. The fact that they speak with a distinct southern dialect and their favorite song is “Dixie” suggests that Barks was thinking of racial prejudice as well conformity when he wrote this story. In the Stajano-Gori essay on the “South Seas” story, we learn that this is the first time since the story’s initial publication that the pages have been shot from Barks’ original art. Most of the stories herein are shot from photostatic copies of the art or use publisher’s negatives, but these materials for this tale were lost, and all subsequent reprints have been shot from restored pages of the published comic book. Until now. The book is laden with publication data and other information that enhances its value as a slice of authentic history, but mostly, it is a Barksian delight, edged with moral implications and full of narrative humor and pictorial comedy of the most exuberant and enjoyable sorts. If you never read any other Barks duck stories, this collection is surely enough to convince you that Barks stands in the very first rank of cartoonists of the last century. Maybe, even, he alone is the first rank.

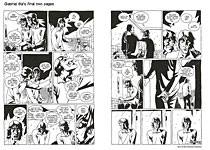

De:Tales: Stories from Urban Brazil By Fabio Moon and his twin brother Gabriel Ba 112 6x9-inch pages, b/w; 2010 Dark Horse hardcover, $19.99 BEFORE THEY DID Matt Fracton’s Casanova books and Gerard Way’s Umbrella Academy and then soloed on the spectacular 10 issues of Daytripper and others of that ilk, the Brazilian brothers did the stories in this book, a dozen of them. They are all highly personal in the sense that they are experimental: in their late teens, the brothers are testing their nascent comics storytelling skills, and for material, they turn to their own daily lives. Interviewed at comicbookresources.com in September 2010 when the book was published, Moon said: “I think we were trying to grow as artists and as people. I think growing up made us look more at our daily life, our reality, and how to make that work, and daily life wasn’t the fantasy and adventure tales we used to read in superhero comics, but it was intriguing, interesting and strange all the same. A lot of those stories were reactions to our real life, even if completely fictitious reactions. And we were always interested in how the characters feel, their emotions, and I think working with somewhat Brazilian characters, and setting the stories in Brazil, helped us find the authenticity of the emotions we were searching for.” In a one-page story, a man awakens when his alarm clock goes off, and he smells coffee and goes into the kitchen and joins his brother for breakfast. End of story. Several of the stories explore the tender relations between a man and woman—not sexual relations, but the seemingly magical connections between them. Love? Probably. Or at least, a desire for love. These are the kinds of comics that talented artists produce when they want to draw—to explore the storytelling capacities of the medium—but have no particular stories in mind to tell. So they fool around with pictorial techniques—layout, panel composition, symbolism, camera angles and distance. Several of the stories are wordless: the pictures do all the narrating. Some of the stories touch upon the mysteries of identity. The most intriguing of them, “Reflections,” appears twice, once drawn by Moon; then again, by Ba. The brothers believe the story is about a missed moment, a chance not taken. True, on the surface of the tale. But it’s also about who the characters are, their identities—a theme possibly not unexpected from artists who are twins, living together all their childhood and in Moon and Ba’s case, looking almost exactly alike. If that wouldn’t create a preoccupation with identity, I dunno what would. The script for the tale, in which a man meets himself (or another man who looks just like him) at the urinals in the men’s room, had been written for a friend of theirs “who wanted to do comics but didn’t have a story,” as Moon explained: “Ba wrote the script for him to practice.” But when the friend didn’t do the story, the brothers decided to do it themselves. “We wanted to show how the same story can be told in very different ways,” Moon continued, “but at the same time, there are certain parts of the story which are better told in a specific way, and these parts are similar in both versions. We were experimenting, practicing, doing it to show that the story only works when it’s done and that you, as an artists, have to learn how to make the story work out even if your take is a little different. It’s like that story says—you can’t think about it too much and do nothing or you lose your chance.” Both of the men bumped into a girl at a party; one stopped to talk; the other didn’t, thereby forfeiting his chance with the girl. Moon took five pages to tell the story; Ba did his in four. Here are the last two pages of each.

Fascinating as the differing details are—pacing, composition—the stories also end differently. In Moon’s, the protagonist is left leakless at the urinal; in Ba’s, the protagonist at last is peeing. What does that mean? It’s up to you.

Nuts: A Graphic Novel By Gahan Wilson 146 8x8-inch pages, b/w; Fantagraphics hardcover, $19.99 IF, BY GRAPHIC NOVEL, you mean a continuous narrative with a recurring cast of characters, this is not quite it. The cast seems to be the same throughout—a little boy whose clothing swallows him whole, leaving exposed only a pinched face and squinting eyes to peer out at a world he can never understand. And his dog Waldo. But each page of this tome reprints one stand-alone installment of the Nuts comic strip that Wilson did for National Lampoon from 1972 through 1981; the strips were not conceived as parts of a larger story but as stand-alone episodes, like any gag strip. The title Nuts evokes Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, but Wilson’s kid is nothing like Schulz’s, as Wilson says, quoted in Gary Groth’s analytically appreciative Afterward: “His strips were little moral fables. He did exactly what he set out to do, and it’s quite extraordinary stuff ... but it has nothing to do with children. ... My rationale was, in the Lampoon style, a rebellion against this: let’s do a children’s strip about children, which was a great motivator. What is it like? What does this little kid go through? ... Constantly forced to obey the incomprehensible rules of a society they cannot even dimly begin to understand, menaced by awesome diseases and fearful technological poisons, endlessly presented with unanswerable questions, these tiny creatures, in a brave if faltering attempt to explain their basically alien environment to themselves, have created one of the richest troves of strange beliefs ever assembled.” And Fantagraphics has assembled them all for an encore in this slim but horrifying volume.

Read it and shudder as you relive the mysterious and threatening childhood you thought you’d left well behind.

The Adventures of Herge Written by Jose-Louis Bocquet and Jean-Luc Fromental Illustrated by Stanislas Barthelemy Translated by Helge Dascher 72 8x11-inch pages, color; Drawn & Quarterly hardcover, $19.95 A GRAPHIC NOVEL version of the life of Georges Remi, famed creator of the international favorite Tintin, Adventures is drawn in the clear line manner of Herge and it rehearses the chief episodes of the cartoonist’s life—his youthful career in Scouting, joining the Xxe Siecle staff, producing his first comic strips, meeting Germaine Kieckens (whom he subsequently married), meeting Chang who inspired Tintin’s adventures in China (and, later, in Tibet), drawing for a Nazi-owned magazine during World War II, being reinstated after the War, meeting Fanny Vlamynck, a colorist on his staff with whom he had a life-long affair while still married to Germaine (whom he later divorced to marry Fanny), supervising the first Tintin movie, being called a racist because of his picture of Africans in the Tintin in the Congo book, and visiting the U.S. The book concludes shortly after Steven Spielberg takes an interest in making a Tintin movie; Herge’s death is fantasized as a journey on an aircraft bearing the letters RG (pronounced “herge”) and the number 83, the cartoonist’s initials and the year of his death. The narrative of Herge’s life is an overview rather than an examination: events are dutifully recorded but their significance is not noted. Chang’s impact upon Herge is only hinted at in the excitement that suffuses their reunion after a 50-year hiatus, and the reason for Herge’s alleged collaboration with Nazis is not mentioned at all. (Mostly, he needed work, and the only work he knew was producing Tintin; and the Nazis wanted the celebrated comic strip hero in their magazine.) The complexity of Herge’s relationship with the two women in his life is merely portrayed not examined. His marriage to Germaine was probably instigated by the editor of Xxe Siecle, the “combative priest” Norbert Wallez, and the marriage was more friendship than romance. Herge’s affair with Fanny, however, is handled in somewhat more detail, and her influence is duly noted. (Since she, after Herge’s death, owned and directed the Tintin universe, the writers of this book may have been flattering her, perhaps in the hope of continued access to the Herge trove.) Herge’s continued friendship with Germaine even after his marriage to Fanny is recorded here but, again, not explained. Herge also has an affair with a hotel maid, suggesting that the two women in his life were not enough for him. Herge is never shown drawing Tintin except on the book’s title page. And the extent of the work of his assistants—Edgar-Pierre Jacobs and Bob De Moor, who, for different but long periods, drew the detailed backgrounds in Tintin, giving the production its distinctive ambiance—is mostly overlooked. When Herge dismisses the work of sometime collaborator Jacques Van Melkebeke, the cartoonist is portrayed as a somewhat snooty megalomaniac. In a rather playful ploy, Herge is sometimes shown meeting people in his life whom he later “employs” as characters in Tintin. The book’s most helpful section for people interested in the facts of Herge’s career is a concluding appendix in which brief biographies are given for all the people in the cartoonist’s life (including, even, Andy Warhol, whom Herge met briefly during a trip to New York). An somewhat abridged version of this book was published in Drawn & Quarterly Vol. 4 in 2001, but it’s nice to have the whole thing now, particularly the concluding section.

Next Time: WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH Jerry Robinson Joe Simon

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY The Thing of It Is ... Our country faces huge problems but we have only petty politicians.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

||||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |