|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 276 (May 5, 2001). The Year of the Rabbit

continues to wend its wayward way through April and into the month of May, and

all of us at Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer wend right along with it,

offering this time another monster-size installment of Rants & Raves.

NOUS R US Free Comic Book Day and “Thor” First Silver Age Comic Book to Break $1 Million Scrooge McDuck Is the Richest Garfield is 30, Ziggy is 40 and So Is the Comics Buyer’s Guide Ziggy’s Nudity Issue New Animated Peanuts, Not Much Too Many Superheroic Movies Royal Weddings Cartooned GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Downturn Still in Comics Shops Tokyopop Shuts U.S. Office Village Voice on the Fate of Cartooning Sendak and Seuss Return EXTRA: Long-Lost Seuss Story Posted in Rancid Raves

PRIZE WINNERS IN EDITOONING Pulitzer: Mike Keefe Herblock: Tom Toles Criterion Criticized Troubletown Ends

WHY DIDN’T WE KNOW BLACKBEARD DIED?

EDITOONERY Some of the Best This Month Libyan Cartoonist Killed As He Cartoons

THE FROTH ESTATE Civil War Osama bin Laden Assassinated; Cartoonists React Film Critic Wins Caption Contest

Newspaper Comics Page Vigil Gas Alley Bids Good-bye to Brenda and Little Orphan Annie

BOOK MARQUEE Skippy vs. the Mob Working with Disney Denis Kitchen’s Chipboard Sketchbook 101 Funny Things about Global Warning Old Farts Are Forever Wild Wood [Wally]: 100 Pages of Art and Text Edie Ernst: USO Singer, Allied Spy The Complete Peanuts: 1979-1980

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Erik Larsen’s Herculian Butcher Baker Last Issue of Fantastic Four Stan Lee’s Starborn No. 4 The Mission

THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Plutocracy in America Paul Ryan’s Scam

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits We’re just a few ticks on the clock away from Free Comic Book Day (FCBD), on which day, Saturday, May 7, comic book shops pay homage to their raison d’etre by giving away a certain number of comic books. And you thought their reason for being was to sell comic books, eh? Not on May 7. At least, not for selected, specially-manufactured-for-the-event titles. When the event began several years ago, comic book shops simply permitted customers and visitors, lured there by the prospect of free comics (these were the folks for whom the idea was originally conjured up), to glom up as many of comic books from the freebie pile as they could carry. Subsequently, as FCBD became institutionalized, two things happened: first, comic book publishers in producing books expressly for the occasion, converted many of them into simple (and blatantly so) promotional pamphlets for the rest of the publisher’s line; second, comic book shopkeepers began rationing the freebies, putting out at one time only a few of the titles supplied by publishers. You can’t fault them: after all, they had to buy the books they were now giving away for free. But now, if you go to your favorite shop with the object of picking up, say, a copy of IDW’s Locke & Key (“soon to be a tv series”) or Drawn & Quarterly’s John Stanley’s Summer Fun, you won’t know in advance if those titles will be available for the taking when you get there. Used to be you just went early and hoped. Now you’re left with just hope no matter how early you go. You won’t find out until you get there which of the touted FCBD titles the shopkeeper has put out for pick-up just then. Again this year, a superhero flick opens the door for FCBD by premiering on Friday, the day before. This year, it’s “Thor,”starring Chris Hemsworth, who, for USA Weekend (April 15-17) recalled the first time he donned the requisite costume: “I walked onto the set, and Anthony Hopkins and I were in our full get-ups. We looked at each other, and he said, ‘Well, there’s no acting required here, is there?’”

***** ANOTHER COMIC BOOK has joined the million-dollar club: a copy of Amazing Fantasy No. 15, the issue in which Spider-Man debuted, graded 9.6 (Near Mint) by the Certified Guaranty Company (CGC), sold for $1.1 million on March 7 in a private sale brokered by ComicConnect.com. This copy, “the highest graded copy to day,” according to Brent Frankenhoff at Comics Buyer’s Guide (CBG), is “the first Silver Age comic book to break the million-dollar barrier and joins only three other comics sold for that amount or more”: Action Comics No. 1 (Superman arrives), $1 million on February 22; Detective Comics No. 27 (Batman begins), $1,075.500 on February 25; and another copy of Action Comics No. 1 for $1.5 million on March 29. Next we’ll hear that Iron Man has joined the club; then Doctor Strange and Scooby Doo. Funny, neither of the illustrious Captains America and Marvel has joined the club yet. “The Book of Mormon,” that irreverent and potty-mouthed musical created by “South Park’s” Trey Parker and Matt Stone (graduates of the University of Colorado just up the road from Rancid Raves Worldwide HQ), will go into the Tony Award ceremonies with 14 nominations, just one short of the record held by “The Producers.” Scrooge McDuck topped this year’s Forbes’ list of the richest imaginary characters; his wealth, mostly gold in coins, soared 30 percent this year to an imaginary $44.1 billion. Of the fifteen listed, five are comics characters: in addition to Uncle Scrooge, Richie Rich is in fourth place; Tony Stark, sixth; Bruce Wayne, eighth; and C. Montgomery Burns from “The Simpsons,” twelfth. ... The Wyndham Grand Pittsburgh Downtown, a hotel, is collaborating with Pittsburgh’s ToonSeum, to provide on-going exhibition space. ... Steve Bodner, master of the caricature of gross albeit recognizable distortion, displays a limited animation enterprise at http://stevebrodner.com/2011/04/15/ saleh-plays-dress-up/ ... Daniel Frankel at Parallel Universe on MSN reported that Warner Bros. Pictures and Legendary Pictures announced April 10 that Michael Shannon will star in the role of General Zod in director Zack Snyder's new Superman film, titled, "Man of Steel." Henry Cavill plays the new Clark Kent/Superman in the film, the cast of which also includes Amy Adams as Lois Lane, and Diane Lane and Kevin Costner as Martha and Jonathan Kent. ... When Warner Bros tweaked the new Wonder Woman costume for the better, it appears it wasn't the end of the story—those offensive shiny pants are back, but there's also a third costume in the offing, although not yet (as of April 18) visible. I gather that all three rigs will be used in the forthcoming production. ... The last three issues of the Sunday supplement magazine Parade carried three cartoons in the “Cartoon Parade” feature, a return, perhaps, to the glory days or yore? From ICv2.com: After a Near Mint copy of Amazing Fantasy No. 15, spotlighting the first appearance of Spider-Man, set a sales record for Silver Age comics, it probably should come as no surprise that a 9.9-graded copy of Incredible Hulk, No. 181 (November 1974), which features the debut of Wolverine, should sell for $150,000. Still the sale represents a new high water mark for a “Bronze Age” comic. No comic published in the 1970s has ever sold for more than this book, which is the highest-graded copy of Hulk No. 181 in existence. Also at ICv2.com, they’ve noticed that Boom!, the presumptive publisher of Disney comic books, has stopped soliciting for new issues of its Kaboom! titles based upon such classics as Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, et al. The supposition is that Disney is bringing all those products back into its tent to be published by Marvel, which became a Disney armature two years ago. “Boom! has done a nice job with its Disney titles; will Marvel do as well? So far, the biggest change has been in format, where Marvel has announced magazine-sized titles for both its Muppets- and Pixar-based titles.” Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard, notorious for his caricature of the Prophet Mohammed wearing a turban shaped like a bomb with a lit fuse, said April 15 that he had not been informed that he was on trial in Muslim Jordan and that in any case would not attend. “I have no intention of going even if I am asked to,” he said, quoted by straitstimes.com, adding, “I do not want to risk becoming familiar with the Jordanian prisons, which would be hell. I have not done anything illegal in Denmark. I only did my job and I will always defend the right to freedom of expression,” he concluded, reiterating meanwhile that he had “never had the intention to offend Muslims and their faith with my caricature.” The drawing, he continued to insist, was “a condemnation of terrorists who commit acts of terror in the name of Islam.” North of the border on this continent, the Canadian Press reported that the Sun News Network launched on April 18 with a showing of Westergaard’s cartoon and the rest of the Danish Dozen on the fledgling network’s very first show, “The Source with Ezra Levant.” “Levant discussed his decision to publish the cartoons back in 2006 when he was editor of the Alberta-based political magazine the Western Standard. A graphic of the magazine spread appeared onscreen during his Monday show that clearly showed the 12 controversial caricatures of Muhammad. ‘What's the big deal?’ said Levant. ‘We just showed it. Nothing bad happened.’” Meanwhile, in Afghanistan, Islamic hooligans continue to seize upon whatever provocation they can find to riot in the streets and kill people, claiming they are acting to preserve and protect the sacred traditions of their so-called religious beliefs. This time, they got all weirded out because that nutjob in Florida, Terry Jones, claiming to be a preacher of the Winnfield moustache (that’s the name of the style he affects), burned a copy of the Koran, just as he promised he wouldn’t last year. Which side is the more foolish is debatable. Jones of the Church of the Moustachio is a blatant publicity-seeker with a one-trick stunt, the performance of which endangers lives of Westerners throughout the Muslim world; but the hysterical Muslim hoodlums, so opposed to idol worship that they condemn making images of Muhammad because they might be tempted to worship the pictures, seem perilously close to treating their holy writ as an idol. Fantagraphics announced in March that will join comics historian Rick Marschall in producing a line of books, Marschall Books, devoted to reprinting comics, cartoons and graphic humor, drawing upon Marschall’s extensive collection of original art, complete runs of comic strips (beginning with 1893 strips), humor magazines, political cartoons, comic books, protest graphics, posters, toys and games, postcards, greeting cards, pinbacks, cartoonist letters and sketches, biographies and anthologies. Among the publishing projects mentioned in the press release, “a definitive three-volume history of cartoons in advertising.” But the list of possibilities is nearly endless.

Anniversaries Go On and On Garfield is 30 this year, and Ziggy is 40, and so is the Comics Buyer’s Guide (CBG). In honor of the fat orange cat, Papercutz announced that it will celebrate the history of Jim Davis’ comic strip with the publication of two volumes based on the “new hit Cartoon Network show”—Garfield & Co., Vol. 1: Fish to Fry; and Vol. 2, The Curse of th Cat People.” Ziggy also gets a book, Ziggy: 40 Years, “a lavish hardcover featuring the best Ziggy panels spanning 1971-2011,” quoth a press release. I’m not convinced that we’re any the better for four decades of Ziggy’s sentiment-soaked witticisms, but 40 years’ worth suggest I’m not typical in holding this opinion. However, I have a nominee for the best Ziggy panel ever. It was perpetrated in December 2009 at the instigation of Stephan Pastis, whose Pearls Before Swine was concluding a sequence in which Rat expressed outrage that the Ziggy character never wore pants. His moral sensibilities offended, Rat went on a rampage to remove this blot on the escutcheon of American decency. At DailyCartoonist, Alan Gardner reported that Pastis phoned Ziggy’s Tom Wilson, explaining the Pearls storyline and asking if, on December 16, Ziggy could wear pants to coincide with the conclusion of the Pearls story. At his blog, Pastis rehearsed the conversation, saying that he told Wilson: “Rat is going to declare victory and say that you—Tom Wilson—have agreed to put pants on Ziggy. Do you think there’s any way you can put pants on Ziggy that day in your panel?” Wilson said, “Sure.” He was, Pastis attested, “as accommodating as can be. He could not have been nicer.” After Pastis did his finale strip, he e-mailed Wilson to remind him that December 16 was the pivotal date, and Wilson confirmed that Ziggy would wear pants on that day. But he didn’t. On the next day, however—December 17—the panel we’ve posted at Rancid Raves Gallery below appeared. (You can quick like a bunny scroll down there and see it.) Wilson tweeted that there had been “an unfortunate mix-up in cartoon placement for the week.” Pastis fired up his blog on the 17th: “Fine, he still isn’t earing pants. But Rome wasn’t built in a day. And, sure, Ziggy creator Wilson had agreed to put pants on Ziggy yesterday, but maybe he needed to warm up to it. Take a few baby steps. And today’s panel is that first step. One small step for Ziggy, one giant leap for decency. The ‘Pants on Ziggy’ people’s movement has borne fruit.”

WE MAY NOT BE AN IMPROVED SPECIES as a consequence of reading (or of avoiding) Ziggy, but we’re undoubtedly a much more sophisticated and aware coagulation of funnybook readers because of CBG. It started, as several of its articles in the commemorative June issue (No. 1678) assert, as a monthly adzine in tabloid newspaper format, cobbled up by Alan Light, a 17-year-old comics fan in Moline, Illinois, and dated February 1971 (the third issue is dated May). Called, then, The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom (quickly, in the custom of those yesteryears, dubbed TBG), it consisted almost entirely of ads and was distributed free for its first two years: printing and postage expenses were covered entirely by ad revenues. How Light unearthed the initial bunch of advertisers and, subsequently, promoted TBG and stupendously increased its circulation (and, hence, its ad rates) is an epic the telling of which the current editors of CBG forego regaling us with. In the initial issues of The Comics Journal 30 years ago, when it was called The New Nostalgia Journal, editor Gary Groth created a minor sensation by detailing the ruthless practices Light employed to stifle all competition. But that’s another story for another day. Although silent on that subject, CBG’s editors devote several pages of their anniversary issue (which, alas, runs to a meager 58 pages, perhaps an all-time low) to reprinting the covers of some of the more noteworthy issues, including Light’s last issue, No. 481 (February 4, 1983), in which he thanked his parents, who “never questioned my sanity when I told them I wanted to quit college and publish a paper about comic books of all things.” He sold TBG to Krause Publications, a specialist in hobby periodicals, and Krause hired Don and Maggie Thompson as editors. The Thompsons had been hanging around in fandom since at least 1960, when they published a fanzine called Comic Art, arguably the first of the breed, and Don was a practicing newspaper reporter in the adult world, so the choice was a happy one. Their first issue, No. 482 (February 11, 1983), carried the new streamlined title, The Comics Buyer’s Guide (from which “The” was eventually deleted), and was entirely typeset; until then TBG’s typography had been by typewriter, its ads often hand-lettered by the advertiser. That amateur informality disappeared with Krause underwriting the effort. With the February 23, 1996 issue (No. 1162), CBG was redesigned as a square, bound newspaper; then it went monthly as a magazine in June 2004 with No. 1595, glossy covers and a few slick paper pages within, fore and aft, embracing the usual allotment of newsprint pages. With its third issue, TBG published a letter from Tony Isabella (who still writes a column for CBG) and soon thereafter was publishing text articles as well as ads. With No. 18 (August 1, 1972), TBG went bi-weekly, and two years later, weekly (with No. 87, July 18, 1975). By then, it was publishing a gossipy column by Murray Bishoff, whose name doesn’t crop up in this issue of landmarks and remembrances. (Bishoff graduated to grown-up journalism as managing editor of the Monet Times in Monett, Missouri, where, saith Wikipedia, he gained a measure of notoriety researching and writing about the 1901 fifteen-hour lynching spree in Pierce City, Missouri, during which white residents murdered three African American residents and inspired nearly 300 others to flee the city.) Shortly after Bishoff became a regular contributor, cat yronwode (who refused to capitalize either her name or the first person pronoun) was producing an increasingly ambitious weekly round-up of news and reviews; she isn’t mentioned in this anniversary issue either. The Thompsons were also doing a column called Beautiful Balloons, which is mentioned, eulogized even, in this issue: Maggie does a whole song and dance about the column and its name. In this celebratory issue, most of the current CBG columnists tell us how they got involved with the magazine, but Craig “Mr. Silver Age” Shutt pauses to remember 1971 as a year of several watershed events in comics. Jack Kirby had just left Marvel for DC in October 1970, so 1971 was his first full year producing material for DC; The New Gods, The Forever People, and Mister Miracle all debuted in 1971. The notorious Comics Code was modified somewhat early that year, attempting to accommodate the country’s evolving mores. Marvel sought to evade even the modified Code by producing a couple of black-and-white magazines, Savage Tales and Kull the Conqueror. DC and Marvel increased comic book cover prices from 15 cents to a quarter, compensating for the increase with a bigger page count. At DC, Carmine Infantino was made publisher, the first artist to occupy the position, resulting in the arrival of several new artists. Rolling Stone featured the Hulk on its issue for September 16, and inside, a big story on comics and their creators, perhaps the first time a national magazine (albeit a counter-culture publication) had devoted so much attention to what had always been seen as a minor, junk-publishing enterprise—funnybooks. And in 1971, Air Pirates Funnies included scabrous versions of Disney mice (having sex and doing drugs) in its July and August issues, prompting Disney to sue for copyright infringement. The case and its subsequent appeals went on for years; it was finally resolved when ug cartoonist Dan O’Neill agreed not to draw any more Disney characters. Quite a year.

Leave Peanuts Alone The new animated Peanuts, “Happiness Is A Warm Blanket,” isn’t so hot, saith Charles Solomon, animation historian, who conveyed his review at herocomplex.latimes.com, to wit (in italics): The new film is largely based on two long continuities that Charles Schulz drew decades ago about Lucy trying to break Linus of his blanket habit. In early 1961, she buried his blanket, forcing him to dig up the entire neighborhood searching for it. Lucy made the blanket into a kite that blew away in mid-1962. Despite the solid source material, the story rambles aimlessly. Several minutes elapse before the plot actually begins and the narrative is padded with irrelevant moments taken from decades of Schulz's work. Violet, Patty and Shermy, whom Schulz lost interest in and dropped from the strip, turn up to re-create some of the first published Peanuts strips. Obvious commercial breaks and the 44-minute running time remind us that the film was crafted to be a one-hour TV special. In fact, this is the 45th entry in the series but the first without Melendez, suggesting just how much pressure was on the new team [writers, son Craig Schulz and Stephan (Pearls before Swine) Pastis; drawn by Bob Scott, Vicki Scott and Ron Zorman]. Mark Mothersbaugh, the Devo co-founder whose music credits in animation includes "Rugrats" and "Clifford the Big Red Dog," delivers a score that is pedestrian at best, and the animation itself is surprisingly uneven. Sometimes the characters have the lively feel of the old specials; sometimes they stand or move awkwardly. The backgrounds include garish colors Schulz never used, and they're too big and fussy. Although Schulz's earliest strips featured broad exterior vistas and carefully rendered rooms of mid-century furniture, he quickly abandoned that look. He stripped his settings to an almost arid minimum, focusing tightly on the characters. During one of the many false endings of "Warm Blanket," Linus stands atop Snoopy's dog house and bluntly denounces everyone else's failures and insecurities. The moment is completely out of character for the gentle, theologically oriented Linus — and a very, very long way from his understated recitation of the Gospel of St. Luke, the moment that spoke to the Holy Ghost that was at work in the best "Peanuts" animation. RCH: We all knew Schulz was right when he determined that no one should continue his work. Now we know it all over again, and we have an object lesson to invoke.

A Surfeit of Superheroism Writing in the May issue of Vanity Fair, James Wolcott says he’s had enough. Running through the list of impending comic book superhero flicks—“Thor,” “X-Men: First Class,” “Captain America: The First Avenger,” “The Avengers,” “Iron Man 3,” “Green Lantern,” another Superman reboot, ditto another Batman, and on and on—he finds his enthusiasm waning. None of these movies are fun anymore, he says: “The more ambitious ones aren’t meant to be much fun, apart from a finely crafted quip surgically inserted here and there to defuse the tension of everybody standing around butt-clenched and battle-ready. ... The superhero genre is an American creation, like jazz and stripper poles, exemplifying American ideals, American know-how, and American might, a mating of magical thinking and the right stuff. But in the new millennium no amount of nationally puffing ourselves up can disguised the entropy and molt. ... Since Vietnam, whatever the bravery and sacrifice of those in uniform, America’s superpower might hasn’t been up to much worthy of chest-swelling, chain-snapping pride (invading a third-rate military matchstick house such as Iraq is hardly the stuff of Homeric legend). ... The movie that mirrors this post-millennial letdown isn’t a movie at all but Julie Taymor’s Broadway musical “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,” savaged and mocked for months by just about everyone with Internet access. ... The haphazard storytelling of the musical muddled Taymor’s vision-idea, but at least there was an idea here to muddle, which is more than most superhero movies have.” It’s been a few years since I’ve seen one of these epics, but judging from the last Batman movie I saw, the genre is distinguished by loud noise and exploding visuals, not ideas.

Marriage at the Upper Crust In honor of the royal wedding of Prince William and commoner Kate Middleton, London’s Cartoon Museum mounted a special exhibition of satirical drawings about the monarchy and nuptials through the years. “The Cartoon Museum,” writes Sophie Grove at herocomplex.latimes.com, “is a quirky converted dairy in a back street tucked behind the British Museum with a library and a permanent exhibition of around 2,000 cartoons, caricatures and comics from 18th century engravings to modern-day animation and comic strips.” The special exhibition, "Marriage à la Mode: Royals and Commoners In and Out of Love,” is “a revealing, barbed view into changing attitudes toward marriage, class and morality in British society.” Among the pictures on display is William Hogarth's 1743 series of scathing caricature engravings titled "Marriage à la Mode" — the story of a wedding across class lines and for all the wrong reasons. “The engagement gathering isn't going well,” Grove says, describing the first picture in Hogarth’s series: “A scrofulous groom-to-be gazes admiringly in a mirror, while his distraught, porcelain-skinned fiancée sobs into a handkerchief. At their feet, a shackled pair of dogs symbolize the ill-fated union that is to come.” The exhibition runs a little thin beginning in the Victorian era, Grove observes, when “the shenanigans of the upper classes were deemed off limits to the press.” The blackout lasted through the early 1930s when the press displayed remarkable restraint in not mentioning the affair that the Prince of Wales, heir to the throne, was conducting with the American divorcee, Wallis Simpson, whom he later gave up the throne to marry. But by the 1970s with the savage advent of such visual excesses as those produced by Gerald Scarfe and Ralph Steadman, satire was back. Scarfe’s version of the nuptials (for The New Yorker, May 2) can be found at Rancid Raves Gallery below. “The visual vitrol” that plagued the marriage of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer “makes today’s images of Kate Middleton look mild,” said Grove, citing the remark by the show’s curator, Anita O’Brien: “So far, Kate has been exemplary in her behavior: she hasn’t put a foot wrong.” Too bad for cartoonists.

SATIRE, HOWEVER, WAS SCARCELY DEAD at the Royal Wedding. It was perched on the heads of most of the ladies in the crowd. Any time the Queen is in attendance, British women are expected to wear hats. The Queen always wears a hat when she’s out in public, and her hats are always remarkable—plain, unadorned, but notably large. Otherwise undistinguished, you might say—if you didn’t opt for “ugly.” For the wedding of William and Kate, she wore a bright yellow hat with a wide brim and a crown of surprising altitude. It came close to rivaling Abraham Lincoln’s top hat. Perhaps as a subliminal critique of Her Majesty’s choice of chapeau, the women in Westminster Abbey and beyond were wearing the most outlandish headgear—swirling knots of cloth, riots of fake flowers, off-kilter tilts, lopsided brims of vast dimension, frizzes and fizzes, curls and loops. Acts of stand-up comedy, every one. If they weren’t staging a satiric protest against the dictate of custom that required them to wear hats, they should have been. It sure looked like satire to me.

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES It’s contest season again. The Comics Buyer’s Guide lists its nominees for the annual CBG Fan Awards in the June issue of the magazine, and I just got a ballot listing the Eisner Award nominees. I voted in one of these polls one year (it was probably the year my Milton Caniff biography was among the nominees and I voted for it), but I usually don’t vote because the categories, particularly with the Eisner, are much too esoteric for me. Best Reality-based Work? Best Publication for Kids? Best U.S. Edition of International Material (Asia)? CBG’s categories are easier to sort through, albeit a little simple-minded—Favorite Inker, Favorite Character. Highschool stuff. But the real reason I don’t vote is that I don’t read enough comics to recognize names or titles in all the categories. And how can one decide which comic book has the Best Lettering—in an age when most lettering is done by a computer program? Best Coloring? All coloring these days is pretty stunning stuff. When TBG was the industry bible, we all bemoaned the sad state of coloring in American comic books compared to the painterly look of European comics. Now we’ve caught up. Took only 40 years. Time magazine’s May 2 “double issue” lists the world’s 100 most influential people. Gratifyingly, Sarah Livingston Palin isn’t among them—although Michele Bachman is. There are numerous other silly choices (Mia Wasikowaska, “an actress who is bold enough to be shy”; actors Colin Firth, “a king with a common touch” and Chris Colfer “for his pitch-perfect portrayal of a gay teen”), but the list is infused with dozens of persons who are not white Westerners, indicating an enhanced cosmopolitanism that we are not used to seeing in American publications. Still, David and Charles Koch (pronounced “kook” despite the advisory “coke”) are here, rapid right-wing bankrollers of Tea-bagging ideologies; as is Arianna Hufington, “baroness of the blogosphere.” But no cartoonists. Unless you count Pixar’s John Lasseter. No Art Spiegelman. No Garry Trudeau. No Charles Schulz, and if Gabrielle Giffords is there, extolled by Baracko Bama’s text as “a symbol of civility—embodying the best of what public service should be,” Schulz could surely stand for the best that comic strips can be.

IN THE LATEST ISSUE of the Previews catalog (April, No. 271) we find a great wad of Doctor Who stuff; he must be making yet another come-back. And in another indulgence of high camp, you can buy a Wimpy Kid action figure. What’s the action? Whimpering? You can also get a Snow White statuette: based upon the Grimm Fairy Tales incarnation, she’s dressed in a short-skirted schoolgirl outfit, pictured below in the Rancid Raves Gallery at the end of this Terribly Informative Section. Too many publications in Previews are dubbed “events”—“a comic book event.” A comic book event is somehow better than a simple comic book? Among the “events” are DC’s Flashpoint series and Marvel’s Fear Itself. I confess that I got tired of these integrated issue min-series almost from the beginning. They pretty quickly evolved into little more than marketing machinations: in order to fully grasp the import of such “events,” you had to buy every title partaking of the theme—twenty? thirty titles?—and you had to read them in order or you’d be more baffled than usual. That’s labor-intensive, kimo sabe, and I’m a funnybook reader for the fun of it, not the work. So for 3-4 months now, I won’t be buying DC books or Marvel’s because I can’t understand what’s going on in a given title without having read all the titles in the series. Sigh. Wonder Woman’s old uniform is back in No. 612 of the eponymous title. Or so it appears. That didn’t take long. Image and Dark Horse, freed of the compulsion to produce only superhero adventure titles, are publishing some engaging titles dealing with human dimension themes, seems to me. And at Avatar, a whole batch of Warren Ellis titles are offered again. Bluewater is going into biobooks in a big way with titles featuring Lady Gaga (expanded and revised in defiance of the subject’s objection to being comicbooked), George Carlin, Hillary Clinton, Keith Richards, and Tiger Woods (how big a role will the bimbos have in this title?). Don Rosa’s magnum opus, The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck, is being offered again, and Classic Comics has arrived at yet another of its sumptuous reprint series, John Culllen Murphy’s Big Ben Bolt Dailies, 1950-1952, the story of a gentlemanly prize fighter limned by one of the medium’s superlative illustrators. And Sunday Press is back with another in its landmark vintage newspaper-sized reprints, Forgotten Fantasy: Sunday Comics 1900-1915, compiling runs of beautifully rendered strips usually overlooked by fanciers of the funnies—such as Lyonel Feinigner’s Kinder Kids, Winsor McCay’s Wee Willie Winkie, and George McManus’ Nibsy the Newsboy, plus Naughty Pete, The Explorigator—all beautifully drawn and handsomely printed in those golden years of yore, and now painstakingly restored digitally and reincarnated by the man who loves four-color beauties, publisher Peter Maresca. In one of those anomalies that infect publications of the sort Previews is, we have Warlord of Mars: Dejah Thoris No. 4 being touted in a variety of cover renderings of Dejah Thoris herself, an understandable marketing ploy because her costume is nearly nonexistent, and we all know that pictures of barenekidwimmin sell—well, whatever it is they’re deployed to sell. On page 262, Dejah’s ample left breast appears in a stunning profile, tipped by the tiniest of pastie-like coverings (the sort of thing Janet Jackson so memorably revealed during a Super Bowl halftime show a few scandal-ridden years ago); then—here’s the anomaly—on page 278, the same cover appears again, but this time, Dejah’s spectacular diamond-studded boob is covered, blotted out—totally obscured—with a yellow censoring starburst bearing the legend “Risque Cover.” The second, er, “appearance” (or, if you will, “non-appearance”) takes place on a full-page ad of Dynamite Entertainment books, constructed, we suppose, by the publisher, which proves to be more sensitive to the threat of hyper moralism than Previews publisher Diamond, which, we suppose, reproduced the cover exactly on the page for which it is solely responsible. Ah, what fun we’re having in these tediously moralistic times. (On the other side of the $ubscriber wall in Rancid Raves Gallery below, we’re posting the two objects of our ridicule in this paragraph.)

RANCID RAVES GALLERY And here,

safely on the far side of the $ubscriber’s wall, are the pictures we’ve alluded

to ere now—Scarfe’s royal couple, Ziggy without pants (still), Snow White in a

tiny skirt, and the variously adorned hooter of Dejah Thoris.

Downturn Plunges on Glen Weldon at npr.org reports that retail sales of both monthly comics and graphic novels are down “and have been for a while. For thorough, clear-eyed accounts of exactly how far down ‘down’ is, and why ‘down’ can mean either ‘flat’ or ‘not all THAT bad, depending on how and what you measure,’ the website ICv2 is indispensable. Things are tough all over,” Weldon continues: “Borders' recent bankruptcy is only beginning to hit the sales of graphic novels hard.” Weldon went on, toting up signs of a withering comics industry: Top Cow “consolidating efforts—and staff—with its parent, Image Comics”; Wizard ceasing its print version. “And as we noted last year, the manga market, once booming, is now bust-ing out all over. Big picture: It's not looking good. Now, sure, ‘not looking good’ has been the comics status quo for years now, and no one seriously thinks comics are going away. But there are some hard questions to be asked about the quality and quantity of stuff publishers continue to crank out, now that readers are spending less.” The Beat recorded on April 15 the biggest casualty so far: Tokyopop shutting down its U.S. operations as of May 31. “The German office will stay open to handle publishing rights and the film division will continue. Founded in 1997, Tokyopop and its founder Stu Levy were at the forefront of the manga revolution in the U.S., introducing such hits as Sailor Moon, Chobits and Love Hina to the US market in the ‘unflipped’ format for the first time. Sales surged as the manga bookstore revolution took over in the early part of the last decade.” Levy left a parting message: “Over the years, I’ve explored many variations of manga culture ... Some of it worked, some of it didn’t—but the most enjoyable part of this journey has been the opportunity to work with some of the most talented and creative people I’ve ever met.” And he finished with a defiant flourish: “Now, fourteen years later, I’m laying down my guns. Together, our community has fought the good fight, and, as a result, the Manga Revolution has been won—manga has become a ubiquitous part of global pop culture. I’m very proud of what we’ve accomplished —and the incredible group of passionate fans we’ve served along the way (my fellow revolutionaries!).”

VILLAGE VOICE

FAUX PAS BIG TIME But Poynter’s Jim Romenesko recorded “harsher criticism from writer and cartoonist Mimi Pond,” who posted her reaction in the Voice comments section: “Village Voice, you have got some nerve printing this story after you asked me and god knows how many other cartoonists to contribute free work for this issue—with the stipulation that it would be ‘good exposure’ for me. You can go fuck yourself! You used to pay me decent money back in the 80s to do full-page cartoons for Mary Peacock’s V section. The 80s were very very good to me. I had a real career as a full-time cartoonist and illustrator. I stopped for a minute to have children and then when I looked up again, my career had fallen off a cliff. So thanks, Village Voice. Thanks a lot.” Dan Perkins, who produces the comic strip This Modern World as Tom Tomorrow, pointed out that “the Village Voice Media chain is one of the major culprits in this—their decision to ‘suspend’ cartoons [in 15 papers in 2009] dealt a serious blow to the struggling subgenre of alt-weekly cartoons.” Tom Tomorrow returned to the pages of the Voice within a few months. But others are still out in limbo. At first, Voice editor Tony Ortega explained with a straight face, telling Romenesko: “This was a special issue celebrating and commiserating with cartoonists on the tough state of their industry. In order to fill it out with so much art, we asked some artists to donate their work. We then felt we couldn’t do that without disclosing publicly [they weren't paid]. I figure it’s better to speak up about something like that than do otherwise.” A confused noblesse oblige at best. The next day, Ortega wiped the egg off his face, apologized and said all the cartoonists would be paid. “I wanted to have a big special comics issue, but I had a limited budget. So in a well-meaning effort to make this work, I asked some cartoonists to provide work without compensation. In the last couple of days, it's been pointed out to me quite clearly that this was not the best way to help out the cartooning industry. The thing is, we're not a company that expects people to work for free for the exposure. And I'm making this right: I'm paying all of the artists in the special issue. And hopefully buying them beers and working with them again soon.” Fine. Now that the episode has been cleansed of its peccancy, we can quote Edroso about the ludicrous conditions under which freelance cartoonists—no, make that most cartoonists—labor. Almost no one who calls him/herself a cartoonist makes a living at it. Syndicated cartoonists come close: although the per-paper rate might be as high as $100/week (depending upon the fame of the comic strip and the circulation of the newspaper), some papers pay only $5/week. My guess is that $15/week is a good average. Mort Walker, Jim Davis, Garry Trudeau, Scott Adams, Dean Young, Jim Borgman and Jerry Scott, and a dozen or so more with 1,000 or more subscribing newspapers might be millionaires; but most cartoonists, even syndicated ones, are borderline paupers like all the rest of us. And I suppose comic book artists fare no better, although Edroso doesn’t say anything about them. Good ones, those who are popular with comics fans, do well; others don’t. And many of the most brilliant stylists are living in other countries—in South America, the Phillippines, Spain—where standards of living don’t require huge quantities of income. They do all right with a corporate pittance. Editorial cartoonists are a vanishing breed as newspapers try to get out of the budget red by firing editoonists. And magazine cartooning has been all but dead for decades. But to scrape together a living, nearly all cartoonists do other, albeit sometimes related, things: they teach, do illustrations, give lectures and workshops to wannabees, blog, draw trading cards, write and/or illustrate children’s books (if they’re lucky and very very talented) and do whatever else seems likely to (1) bring in money and (2) advertise their availability to do paying work in some drawing-related endeavor. They all diversify to put food on the table and pay the rent. “Most comics people have to hustle at the outset of their careers,” Edroso writes. “ That's expected. At least it makes for funny stories.” And he goes on with Tony Millionaire’s tale (in italics): In his salad days, for example, Tony Millionaire (Maakies, Sock Monkey, Drinky Crow) would take the train from New York to towns in Westchester County, and look on a map "to find where the streets were curvy," he says, "because you'd know that's where the hills were." Then he'd walk up to the lavish hillside homes and leave cards in mailboxes or tucked into screen doors, announcing that he would draw the house for a small fee. His success rate was three gigs per hundred cards. "Yeah, I really outsmarted the world," he laughs, "and got into a job that paid hardly fucking anything." The New York Press picked him up at $35 a strip and eventually upped it to $100. When Millionaire went to the Voice, they gave him $150. In cartooning, that's a bidding war. The pathetic pay gets less funny as you get further along in your career. [End italics] Edroso cites the experience of Harvey Award and Xeric Grant winner Jessica Abel. In addition to making graphic novels (La Perdida, Life Sucks, Radio: An Illustrated Guide with Ira Glass), she edits the Best American Comics series, teaches, gives workshops and lectures, does illustration, and blogs. “But busy is good, right?” Edroso asks, rhetorically. "It is and it isn't," says Abel. "It's not all stuff that pays. Like the website [for her and Matt Madden's Drawing Words and Writing Pictures book] doesn't pay anything. I want to do it, I enjoy doing it, it's valuable in many, many ways. But it doesn't pay me a cent. And I spend a lot of my time doing that." She feels she has to do it, and a lot of other self-promotional stuff, "because if you don't," she says, "your career is going to suffer." But she's painfully aware that it keeps her from working on comics ideas "that might turn into something great." What about the online future? “Computers are the future, right? They certainly are, which means that while a few intrepid pioneers have a staked profitable claims, most Web comics are still looking for a waterhole. Edroso turns to Dorothy Gambrell, whose Cat and Girl is “one of the best-known webcomics.” Gambrell thinks “neither [print nor online] is better than the other, but one is happening now and the other no longer exists. Now it's easier to reach people online, so it's easier to make a living that way," she says. But the living isn’t much, Edroso points out: “Gambrell has posted her revenue mix for 2010 as a chart, and it is a fascinating document. The chart shows how much of her income came from prints, original art, merchandise, conventions, publication work, the Donation Derby feature through which she accepts money from fans and draws cartoons about how she spent it. She reports that in 2010 she made $21,098.54.” In other words, she’s very possibly poverty-stricken. The official, government poverty line for 2011 was set at $22,350 (total yearly income) for a family of four. Dunno if Gambrell is married or how many children she has. Wikipedia says that “most Americans (58.5%) will spend at least one year below the poverty line at some point between ages 25 and 75.” But it sounds to me as if Gambrell is making a career of it. And she’s not alone. Jason Yungbluth, who drew Deep Fried, “a big underground hit with the comics cognoscenti 10 years ago,” now works the Web with installments of his “ever-evolving epic, Weapon Brown, starring a sort of grown-up, weaponized Charlie Brown, plunked down in a dystopian future.” Yungbluth sells book compilations of his cartoons on his website. “A third of his income comes from the site; another third comes from freelance assignments (he frequently appears in Mad magazine), and the rest from a one-night-a-week gig teaching cartooning. So how's he doing? "I have a roommate," he says. "I drive a good car, but a very old car. I rent, I don't own. Put it this way: I'm on Medicaid." He hopes to produce a Weapon Brown graphic novel and he’s saving money, hoping to be able to pay for a table at the New York Comic Con to launch the book in 2012. “Those are expensive tables. I'm trying to find someone who'll split some space with me." Most freelancing young cartoonists learn pretty fast that “making comics wasn’t ever going to be about making money.” They do it out of the sheer love for the medium. But wouldn’t it be nice if they could make a living at their passion?

AT THE HERBLOCK FOUNDATION, alarm over the dismal future foretold for editoonists has prompted the governing board to conduct a survey, preparatory to issuing a report “on the future of editorial cartooning in the face of the massive technological advances that are reshaping the American news media.” The report will serve the founding purposes of the Foundation, which was established and funded by cartoonist Herb Block to foster editorial cartooning. Herblock once wrote about his profession: “Cartooning is an irreverent form of expression, and one particularly suited to scoffing at the high and the mighty. If the prime role of a free press is to serve as the critic of government, cartooning is often the cutting edge of that criticism.” And, hence, vital to the functioning of democracy. Over th signature of chairman of the board Frank Swoboda, a letter went out to editorial cartooners at the end of March, aiming to collect data about the present state of the profession. The accompanying questionnaire probes editoonists’ sources of income and syndication status as well as job requirements and the like. Respondents are also asked to offer “any thoughts” they may have “regarding the current state of editorial cartooning and what, if any, changes you believe are needed to assure survival of the art form in the digital age.” Foundation representatives will also interview syndicates, newspaper publishers, and journalism school officials “as well as experts in emerging technologies” and “any other thoughtful individuals who might have something worthwhile to say.” It’s a noble and needed endeavor, and I wish it success in every sense.

Cartoonist Storytellers for Children Return FOLLOWERS, ADHERENTS AND OTHER DEVOTEES of children’s literature created by cartoonists were no doubt delighted at the news that new books by two giants at the craft will appear this fall. Maurice Sendak (whose controversial In the Night Kitchen was inspired by Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo) has written and illustrated his first new book in 30 years. Bumble-Ardy tells “the story of a young pig who has never had a birthday party so on his ninth, he takes matters into his own hands and invites nine pigs over for a forbidden party,” Deborah Netburn reports at the Los Angeles Times. Sendak first developed the character in 1971 for a Sesame Street short, and the character lodged in the backroom parts of the author’s mind. “He was funny. He was robust. He was sly. He was a sneak. He was all the things I like,” Sendak said in a New York Times interview. In the Sesame Street project, Bumble-Arby was a boy, not a pig, but those he invites to his party are all pigs, nine of them, whom he offers birthday cake and wine; in a surrender to current over-active sensibilities, “wine” becomes “brine” in the book. Perhaps, however, the book will preserve Bumble-Arby’s mother and the “glorious epithet” she shrieks when she comes home to find it full of “swilling swine”: “Split, get lost, vamoose, just scram, or else I’ll slice you into ham.” The rhyme evokes the other author making a surprising comeback. Random House breathlessly proclaimed in early April that it would publish in September seven “lost” stories by Dr. Seuss (aka Theodore Seuss Geisel, doncha know). But the Seuss sauce in The Bippolo Seed and Other Lost Stories was scarcely “lost” in the usual sense. All these stories were originally published in Redbook magazine in 1950-51 and qualify as “lost” only insofar as they’ve never been collected in book form. “Random House,” wrote Rebeckah Denn at csmonitor.com, “describes the stories as ‘transitional’ ones in Seuss’s approach to writing for children, written in a period during which he shifted from writing predominately in prose to his well-known rhymes.” Among the stories in the book is “The Strange Shirt Spot,” called the “inspiration for the bathtub-ring scene in The Cat in the Hat Comes Back.” The stories, known mostly to Seuss scholars and collectors, surfaced in an entirely modern manner: Dr. Seuss’s art director stumbled into eBay and saw magazine tearsheets for the stories on sale. No word about whether they are illustrated by Seuss in his distinctive flap-foot style, but my guess is they are. Meanwhile, here’s a sample of Seuss’s work from his cartoonist period, poached from the September 27, 1930 issue of the humor magazine Judge. PLUS—fanfare! ruffles! flourishes!—a 6-page long lost story! Discovered, quite by happenstance, by Yrs Trly in the March 1938 issue of Judge. Send out bulletins! Notices! Sky-writing aeroplanes!

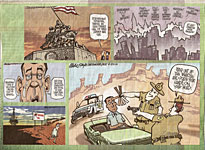

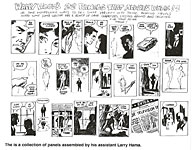

PULITZER PRIZE FOR EDITORIAL CARTOONING Editoonist Mike Keefe found himself on the front page of his newspaper on Tuesday, April 19, as a proud Denver Post announced that he’d won journalism’s highest honor for editorial cartooning: “Just when he figured his window of opportunity had closed, longtime Denver Post editorial cartoonist Mike Keefe on Monday won this year’s Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning,” wrote reporter Kevin Simpson. "I am gobsmacked," said Keefe, 64. "In recent years, the Pulitzer has gone to much younger folks who are newer in the business. I've always done pretty classical editorial cartooning. I thought my day had passed." Unlike that younger generation Keefe referred to, he does no animated editoons on a regular basis. His cartoons appear Wednesday through Sunday, and on Sunday, he and letters editor Cohen Peart do a weekly "Name that 'Toon" feature to which readers contribute captions to Keefe's drawings. Off campus, he and retired (involuntarily from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette) editorial cartoonist Tim Menees create satirical news and visual commentary at President Ruttles website, ruttles@sardonika.com, Finalists in editorial cartooning were Matt Davies of the Journal News in Westchester County, N.Y., and Joel Pett of the Lexington Herald-Leader in Kentucky. Both have previoulsly won. Like all candidates for the Pulitzer, Keefe submitted a portfolio of 20 editorial cartoons, which judges cited for their wide range and the way he used a "loose, expressive style to send strong, witty messages." Alas, this is the lingo of people who don’t quite grasp what editorial cartoons do: all editoonists produce “strong, witty messages” on a “wide range” of topics or they couldn’t keep their jobs, and their drawing styles differ, some drawing loose, sketchy pictures; others, tight renderings complete in every detail. Neither manner is superior (more Pulitzer-worthy) than the other. But, what the hoot—Keefe’s stuff over the last year was more than pretty good: he deployed visual metaphors inventively, ingeniously—unexpectedly—to create powerful and memorable images. Keefe’s work shows up regularly in our Editoonery department (in this very issue, as it happens—and as recently as last time, Opus 275, if you’d like to revisit a couple). When he began at the Post, Keefe’s drawing style, deploying a fragile wandering line, strenuously resembled Gahan Wilson’s. For the last couple decades, though, Keefe has evolved a strong clunky but simple outline style for delineating his gnarly anatomies which he then decorates with restrained flicks of hachuring. Hardly, I would say, “loose”; “loose” is Pat Bagley, a champion at it. Keefe’s winning this year complete’s the Post’s record: all of its editorial cartoonists have been Pulitzer winners since Paul Conrad won in 1964, just before leaving for the Los Angeles Times; and his successor, Keefe’s predecessor, Pat Oliphant, after figuring that the Pulitzer committee usually gave the Prize for sentimental, maudlin cartoons, doped out one of his own tear-jerkers soon after arriving at the Post and won with it in 1967. Keefe told Simpson that his style has evolved from "analytic" early days, when he dissected the work of his favorite cartoonists to figure out how they arrived at their takes on issues of the day. With time, that process became internalized. "It's rare to get one of those 'light bulb' ideas," Keefe said. "Mostly, it's a long process of selecting a topic, writing down what I believe about this issue and then looking for connections to other things that are happening in society that I could possibly use as a metaphor to make my point. Sometimes humor is the vehicle, sometime irony, sometimes drama. It's all over the place." Simpson reported that Keefe joked that he's lucky to get paid for doing basically the same thing he did in third grade, when he doodled in the margins of his notebook and made fun of the teacher. Turning serious, he said his colleagues shared in his award. "This is recognition of the whole paper," he said. "I get support from the editorial page, the art department and reporters. I couldn't have done this without you guys." Although he felt he had some strong entries in his portfolio, he had no inkling that this would be his year. "It's up and down, like being a baseball player—if you're hitting .300, you're doing well," Keefe said. "I felt good about this year, but I didn't know if this would be a Pulitzer year. It caught me by surprise." Keefe joined the Post in 1975, launching his second career. The first, commenced after two years in the Marine Corps, was as a math instructor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, where he completed course work toward a doctorate, but he also cartooned for the school newspaper, the University News. Watergate was headlining the news then, and Keefe became an expert at rendering Prez Nixon’s ski-chute nose. “With material this rich,” Keefe once wrote, “I was fooled into believing that cartooning would always be easy.” He gave up math and went to the Post. Post publisher William Dean Singleton said Keefe's work underscores the importance of newspapers in generating original content, which, ironically, eventually winds up on the Internet, contributing to the slow extinction of the print medium. "Mike's award certainly is symbolic of the hard work that our entire staff does every day," Singleton said. "And it emphasizes once again that virtually all content starts with print newspapers." He called the Pultizer recognition “long overdue,” adding: “Mike's been here almost 36 years, and he's put out award-winning work almost since the day he arrived. The two who preceded him were legends. I think Mike is now a legend too." In

the same issue of the Post with Keefe on the front page, the paper

published a full-page ad inside, announcing his achievement and printing some

of his 20-cartoon portfolio. Hereabouts is the cartoon part of the ad. CURIOUSLY, THIS YEAR the Pulitzers arrived with almost no anticipatory rumors and excited speculations paving the way. The untoward circumstance attracted the attention of Roy J. Harris Jr. at Poynter, who wrote about the “evaporated” buzz about this year’s top journalism prize: “Why has discussion nearly evaporated this year about who will win in the 14 Pulitzer journalism categories? (There are also seven prestigious Pulitzers for arts-and-letters and music, of course.) In addition to a shrinking supply side—with fewer journalists these days trying to pry the names of finalists from jurors who met at Columbia University March 7-9—it could be argued that there’s a much weaker demand side, too. In part, the decreased pre-Pulitzer interest stems from the explosion of other, earlier journalism-award announcements.” For editorial cartoonists, nearly a dozen awards wait every year to be conferred upon a steadily diminishing number of practitioners—the Herblock, National Headliner, Sigma Delta Chi, Thomas Nast, NCS’s Reuben, Robert F. Kennedy, John Fischetti, Berryman, and Ranan Lurie. And most of these are awarded before the Pulitzer winner is announced, which, Harris observes, puts the 19 Pulitzer Prize board members in the position of “annointing” work that has already been recognized. Understandably, there is less fuss and feathers by the time we reach the end of the parade. Another reason for the seemingly diminished buzz may be that part of the world that delighted in buzzing is smaller: print journalism, which is still the chief focus of the Pulitzer, is scarcely as ubiquitous or powerful as it once was. And buzz these days, if it occurs at all, occurs on the Web or tv, not in newsprint.

THE MOST RECENT WINNERS OF THE PRIZES enumerated a couple paragraphs ago (the Herblock, National Headliner, etc.) all appear in the third annual Prizewinning Political Cartoons: 2011 Edition, edited by Dean P. Turnbloom, who supplies a description of each award (plus a caricature of the person for whom the award is named) and a short biography of each winner (112 8.5x11-inch pages, color; Pelican paperback, $19.95, less at Amazon). The winners herein: Mark Fiore, Matt Wuerker (twice, once as Pulitzer runner-up, once as winner of the Herblock), Robert Ariail, Tony Auth, Nate Beeler, Dwayne Booth (“Mr. Fish”), Mike Peters*, John Sherffius, Dana Summers, Stephen Breen, Bill Day, Alexander Hunter, Mike Keefe (the Berryman), Mike Luckovich*, and Jack Ohman*. All except those marked with an asterisk (*) are accompanied by several of their cartoons, and since the cartoons are award-winners, the book as a whole is vivid testimony to the power of editorial cartooning. John Sherffius’ brilliant deployment of symbols is always striking, and it’s nice to see several of his all at once, but the eye-opener for me was the work of Alexander Hunter, who joined Sun Myung Moon’s Unification movement in the early 1980s and wound up as art director of Moon’s Washington Times, established in 1982. Apart from illustration and design, Hunter does a weekly full-page cartoob, sometimes in comic strip format, which, as you can see from the examples near here, is well-drawn and memorably eloquent

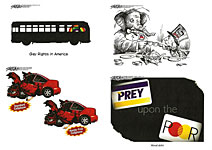

VARVEL GETS HIS Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com received a tweet by Gary Varvel on April 18 (at just the time the Pulitzer winners were announced) saying Varvel received this year’s Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for editorial cartooning. Said Gardner: “Gary did a 11-part series, called ‘The Path of Hope,’ that highlighted some of the underprivileged living in the Indianapolis area. ... Twice a month, Gary would head out of the office and interview individuals, their friends, pastors, teachers and those who work to help a less fortunate person climb out of their difficult circumstances. Gary tells me that he even spent a week traveling on the local bus system to better understand how difficult it was for one family to simply get fresh groceries because the bus route takes so long from the store to their home (think about the slowly melting ice cream or other refrigerated foods). ‘The Path of Hope’ gave Gary a full color page to tell their story. For speed in producing the page, he blends his line art with photo art processed to look cartoonish. Along the way, Gary says he’s grown to appreciate the challenges some people are given in life and their tenacity to pull themselves, and pave the way for others, to get out of poverty.” Here

are a few Varvels to marvel at.

TOLES GETS ANOTHER HERBLOCK When in 2001 the legendary Herblock died at 91 leaving vacant at the Washington Post the editorial cartooning chair he’d occupied there for 55 years, speculation ran rampant through the profession about who would succeed to the nation’s most influential editooning perch. The suspense ended a year later when Tom Toles moved into Block’s old office. A couple weeks ago, Toles picked up, poetically speaking, the rest of his legacy when he was awarded the Herblock Prize. Mike Cavna at ComicsRiffs reported that Toles is the eighth cartoonist to win the award, which was created in 2004 "to encourage editorial cartooning as an essential tool for preserving the rights of the American people through freedom of speech and the right of expression." What the Pulitzer is to journalism generally, the Herblock is to editorial cartooning specifically—the most prestigious award in the field. Toles received a tax-free $15,000 cash prize and a sterling-silver Tiffany trophy. “The Post swept the awards,” Cavna said, “—Ann Telnaes, who creates animated cartoons for Washingtonpost.com, was the first finalist to be publicly announced.” "I walk in Herblock's slippers," Toles told Cavna, alluding the Herblock’s customary garb at work. "I am highly honored." Toles won the Pulitzer in 1990 while at the Buffalo News. A graduate of the State University of New York at Buffalo, he has also drawn for the Buffalo Courier-Express, New York Daily News, and the magazines New Republic and U.S. News and World Report. Previous recognition of his cartooning excellence include John Fischetti Award, the H.L. Mencken Free Press Award, the National Headliners Award and the Overseas Press Club Thomas Nast Award. The judging line-up for the Herblock this year included two editoonists, both Pulitzer winners—Politico’s Matt Wuerker and the Philadelphia Daily News’ Signe Wilkinson—as well as Harry Katz, curator of the Herb Block Foundation. Cavna quotes all three about their choice. Wilkinson commented: "Day in and day out, Tom Toles uses his minimal style to maximalist effect. ... He is a worthy heir to Herbert Block." Wuerker said: "It's a magical combination of sharp and timely political insight mixed with humor, all served up with a disarmingly whimsical drawing style." And Katz, waxing a little more poetic than insightful, said: "Working with the cauldron of Washington politics he cooks up a potent brew of humor, outrage and irony, representing the best traditions of American political cartooning." Soon after the announcement, the judges decided to “lift the veil” about their decision-making process, and Cavna posted the results, as voiced here by Wilkinson and Wuerker (in italics): Before the judging, it was agreed that this year the finalist would also be recognized. We knew the job was to come up with two top cartoonists. We had a great, broad sampling of political cartooning today: lots of traditional single-panel cartoons, plenty of stellar 'altie' work, a number of great ventures into cartoon journalism and, of course, the animation submissions. We even had cartoons rendered with actual oil from the BP spill. In the apples and oranges comparisons that are such a big part of the process, it was hard to measure the simple punchy genius of single panels by the likes of Lexington Herald-Leader's Joel Pett and the (Illinois) State Journal-Register's Chris Britt against long-form docucomics that went beyond the headlines, like those submitted by the (Portland) Oregonian's Jack Ohman, the Boston Globe's Dan Wasserman and Indianapolis Star's Gary Varvel, or for that matter animated reporter's sketchbooks such as the engaging submission from the Sacramento Bee's Rex Babin. The Free Press's Mike Thompson's finger on the pulse of Detroit crime and United Features's Bill Day's attention to child abuse were both powerful uses of our medium. For taking us where cartooning had not gone before, Universal Uclick's Ted Rall's enterprising trip to Afghanistan was particularly noteworthy. Salt Lake Tribune's Pat Bagley's wonderful loose humorous style and his engagement with his readers made him a contender. The 'alties,' led by Matt Bors and Jen Sorensen, all made it to the semifinal pile, as did Investor Business Daily's Michael Ramirez, whose graphic punch and strong, clearly expressed political opinions kept him in the running right up to the end. We all agreed that, to the best of our abilities, we'd not judge according to our political bent but solely on the quality and consistency of the cartooning found in the portfolios we were looking at. Though former (N.Y.) Journal News cartoonist Matt Davies [now with the Hearst papers] had what we all agreed was the single best cartoon of the year, “Peek-a-Boo” on WikiLeaks (by the way, a non-animated black-and-white single panel ), the quality and creativity of the Toles and Telnaes portfolios put them at the very top. Choosing between the two was excruciating and took a while, but in the end we felt the overall consistency of Toles's complete portfolio made him the winner, with Telnaes No. 2 by a hair ... or a .3 Micron line. [Terminus italics.] This discursive roll call of the final contenders is much superior to the Pulitzer committee’s rather lame attempt to say what they were thinking: at least with the Herblock group, we get a notion of the sort of daunting assignment the judges undertook. Stacking up the competition suggests a measure of Toles’ and Telnaes’ achievement, and then the judges say explicitly that they were looking for quality and consistency, consistency ultimately deciding the issue.

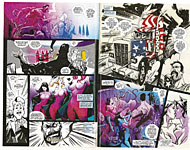

BUT “CONSISTENCY” AS A CRITERION is alarmingly shaky when we realize that the judges were looking at a portfolio of only a couple dozen cartoons from each cartoonist’s annual output. Each cartoonist would naturally fill his portfolio with what he regarded as his best work, creating an artificially induced consistency that may not be so much in evidence over twelve months’ cartooning. “Consistency” becomes thereby an ineffective criterion because it must be presumed to be everywhere in the portfolio: and if it’s everywhere in the portfolio, then it cannot distinguish one cartoon from another, or the work of one cartoonist from that of another. By an ancient axiom of logic, anything that’s everything winds up being nothing. That leaves “quality,” and it leaves it as illusive a criterion as ever. (Besides, what, exactly, is “consistency” in editorial cartooning if it isn’t “consistent quality”?) But

this clutch of judges offers a clue about what they mean by “quality” in the

cartoon they confidently dubbed “the best of the year.” I’ve included this

exemplar with three of Toles’ efforts in the proximate visual aid. But when we note what spectral Death is saying, Davies’ composition assumes another aspect, complicating and thus multiplying its meaning. Judging from its remark, Death—and its handmaidens, the governments and military forces at work on the far side of the wall of War—seems to resent the peeping tom’s prying into the bloody business being so efficiently dispatched over there. Death et al would much prefer to pursue their grisly operations without the interference of busybodies who want to get at the “truth” of the ways a political war is being waged. In sum, the window Wikileaks opens on the wars may be infinitesimal, but in such ghastly matters, any peek, however small or short, makes a convenient secrecy difficult, if not impossible, to maintain. By this insight, we may assume, I think, that “quality” for this year’s Herblock judges has to do both with the clarity of the metaphorical language and with its nuances, complexity inherently deepening the meaning of any such endeavor. One of Toles’ cartoons performs in a similar fashion. The helmeted rifle as tombstone combined with Congress’s comment makes a powerfully ironic statement about gays in the ranks. And the comic strip that portrays the strategic deviousness of Obama’s presumed manipulations is an equally clever deployment of metaphor to depict the imagined expertise of the Prez’s machinations behind the scenes. But “Two-Teared Economy” achieves a slightly greater measure of complexity. The two tears in the picture are a pretty puny demonstration of commiseration; crocodile tears always are phony, by definition. But with a different spelling, “two-tiered economy” deftly alludes to the class warfare inherent in any confrontation these days between the Republicans and the Democrats (and most of the rest of us, too). The two tiers are the rich and the not-rich. The next step in translating Toles’ picture is to realize that the person the croc is addressing is sitting on a plate: he’s destined to be the creature’s next meal. No wonder, as he contemplates his dinner, the croc isn’t weeping tears of genuine sympathetic understanding. And to make sure we realize that getting eaten is the fate of all of us on the plate, the croc makes another appearance in Toles’ corner at the lower right: it’s not a handkerchief the croc is holding but a napkin, an accouterment of the dining table. Complexity and nuance are undeniably vital ingredients in the best editorial cartoons. In other words, the best editorial cartoons do more than merely throw stones at those with whom the cartoonist disagrees. (And even if we carp about the operational validity of such alleged criteria as “consistency” and “quality,” we do not, in the least, question the validity of this year’s choices: Keefe and Toles are undeniably first-rate, unflinching editorial cartoonists. It’s just difficult for judges to describe how and why they are so good.)

TOLES’ PROFESSIONAL BIOGRAPHY is outlined at Politico.com/click by Keach Hagey, who calls Toles a chip off the old Herblock. Majoring in English, Toles found extra-curricular satisfaction in doing three-dimensional illustrations for the campus newspaper, The Spectrum, and when Toles showed some of his creations to the editor of the Buffalo Courier-Express, Douglas Turner, he was hired part-time as a caricaturist. But Turner began at once nudging Toles towards political cartooning. Toles resisted: “I said ‘No, I don’t want to do that,’” he recalled. “‘I don’t have the skills. I don’t have the interest. I don’t have the knowledge.’ That seems like a pretty good case, right? Three disqualifiers.” But, said Hagey, Turner wanted him to try it anyway, so he did. “I kept trying to get out of it. Hated it. Just hated it. And I was pretty bad, in my opinion. But he just kept at it and at it and at it.” Turner pushed because he saw something special in the young artist., telling Hagey: “He had a political consciousness, and he just saw through all the crap. He had the moral strength.” Toles claims his evolution into a fully fledged editoonist was a long slow process, but it was accelerated when the Courier-Express was bought by Cowles Media Company in 1979. His new bosses, instead of choosing a daily cartoon from several possibilities he offered them, told him to pick his best idea and that’s what would run. Said Toles: “All of a sudden the content of what was going into these [sketches] changed completely. I was amazed at how much I had been tailoring. I didn’t do anything I didn’t believe in, but it was ‘What can I do within this framework that’s actually going to get in the paper?’ So then it changed a lot. I started doing what I wanted to do.” There was an initial outcry from readers, Hagey reported: “One day,” Toles said, “every single letter in the paper was a condemnation of me. Every single one.” But the publisher stood by him. “He said, ‘Just keep doing what you are doing,’ and it’s been that way ever since.” And when Toles came to the Post in 2002, he demanded a similar relationship with editorial page editor Fred Hiatt, and he got it. “Luckily,” Toles said, “Herb had that deal, so it’s been the same since then.” Toles regularly stoked a certain amount of unhappiness for the first eight years of the new century by criticizing the Bush League. “While he said he has no trouble finding absurdities to mock under the Obama administration,” Hagey observed, “he admits it falls closer to his own sensibilities.” Said Toles: “Obama is the kind of president I like. He’s thoughtful in the way I like. He’s liberal, moderate in the way I sort of think of myself.” Toles said he doesn’t relish making readers angry, but that’s a natural consequence of editorial cartooning: “Cartooning is essentially a negative art form,” he said. “It’s a criticism form.” Added Hagey: “He credits his own weirdness with helping him come up with the original ideas required for political cartooning. While there is a mechanical process of reading the news and making lists that leads up to his creative effort, and a mechanical process of refinement and execution that follows it, the central leap he has come to see as a result of ‘bad wiring.’” Toles explained: “It’s kind of like this big electrical storm, and things are associating with things in ways that normal brains don’t do quite as easily,” he said. “For the last few years,” Hagey added, “Toles has found a new outlet for his electrical storm, as the drummer for the journalist-government bureaucrat supergroup Suspicious Package, a five-piece band with members from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, Bloomberg, the Los Angeles Times and the Department of Housing and Urban Development.” During his day job, though, Toles keeps the beat by pounding miscreants in public life.

Troubletown’s Troubles End in April LLOYD DANGLE WORKED FOR A FEW YEARS at the Village Voice and others of the ilk, then self-syndicated his Troubletown cartoon, beginning with the San Francisco Bay Guardian in 1988. At blog.cagle.com, Daryl Cagle reported that “Dangle grew his list of subscribers to upwards of 30 alternate newsweeklies and lefty political magazines before tough economic times hit the newspaper industry and slowly whittled his list down.” In March, Dangle announced that after more than two decades, he’s “retiring” his strip to move on to other projects; the last strip appeared at the end of April. Cagle interviewed him, asking the obvious question: why quit now? To which Dangle said: “I have changed over 22 years, and the thrill is gone. Having to read so much news and opinion to stay on top of events is a grind that I would like to be free of. It has nothing to do with the state of the industry though. I’ve been satisfied with my relationships with my newspapers and thrilled that I’ve had the readership I’ve had.” One of the projects he’ll now have time for is finishing the novel he’s writing. “Of course, [book-] publishing is a crap shoot,” he acknowledged, “but at least I’ll be able to amuse my friends with it.” Dangle also expects to do a little cartooning. “After a break I imagine that I’ll get the bug from time to time,” he said. “I’m going to continue blogging at troubletown.com, where I’ll post sketches and commentary and share weird things that I discover. I also tweet acerbic comments occasionally.” Asked about his favorite cartoonists, Dangle named “young up and coming” cartoonists like Jen Sorensen and Matt Bors. “I also love the old timer Pat Oliphant. David Sipress is my favorite of the New Yorker style cartoons.” But he doesn’t think there’s much of a future for cartooning with the models we’re familiar witih. “The Internet hasn’t been our friend,” he said. “I hope they find a way to make it work.” As a commentator who leans over to the left, Dangle doesn’t have a high opinion of Obama: “Obama is a stuffed suit who put together a very convincing, even inspiring campaign, but is now governing as a moderate Republican. Why he’s so hated by the right is baffling to me.” Conservative cartoonists bore him: “I find [conservative] cartoons tedious except for the ones I really like. Conservatives, when they try to be funny, annoy me, but not so much that I would write them the kind of e-mails I receive. I find liberals ridiculous too.” Here,

by way of waving a fond Rancid Raves farewell, are a few Troubletowns.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”—Martin Luther King, Jr. About developing new tv shows, network boss Jack Donaghy (Alec Baldwin) said: “We produce more failed pilots than the French Air Force.” “Intelligence tests are biased toward the literate.”—George Carlin “Education is the inculcation of the incomprehensible into the indifferent by the incompetent.”—John Maynard Keynes