|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 274 (February 28, 2011). The Year of the Rabbit continues apace as we report on the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University—its history, Ireland’s biography, and the 2010 Festival of Cartoon Art that the Cartoon Library sponsored. (Maybe a bit too much on OSU doings, but Ireland’s life and art are fascinating and well-illustrated, and this section is arranged so you can steer up to Ireland and then beyond without wasting valuable time on badly reported presentations that your half-deaf reporter can barely hear, let alone report.) We review a new history of American Political Cartooning and books about The Punch Brotherhood and Five Decades of Sergio Aragones’ cartooning at Mad, plus John Byrne’s Next Men and Fantastic Four No. 587 wherein the Human Torch goes out. And we spend far too much time listening to Gareb Shamus, Wizard CEO, explaining that nothing’s amiss there even though the Wizard mag has ceased. Also: drama critics have at Spider-Man, Superman flick cast, Trudeau’s data verified, Reuben finalists announced, black cartoonists are revisited for Black History Month, and Carl Barks makes cameo appearances in Disney comics. And we bid farewell to Bill Crouch and Dwayne McDuffie. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US 60TH Anniversary for PS Magazine Reuben Finalists Parade at Sandy Eggo? Archie Graphic Novel, Politics at Riverdale Bill Holbrook Site & Books Spiegelman Gets Angouleme’d

RANCID RAVES AT THE MOVIES Superman Cast Forthcoming Superflicks

CONGRESSMAN IN THE COMICS John Lewis Writing a Graphic Novel/Autobiography

SLINGING AT THE WEBSLINGER Critics Open Up on Broadway’s Spider-Man Wizard the Magazine Ceases But CEO Gareb Shamus Goes on Forever Comics Buyer’s Guide Reigns

YOUR EUSTACE Contest to Portray New Yorker’s Mascot Tina Brown and Newsweek Light Fireworks

BLACK CARTOONERS REVISITED RCH Meets Pearls’ Pastis and Lives Despite Devastating Satirical Attack

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL RETURNS Trudeau’s Accuracy

Jivey Department

BILLY IRELAND CARTOON LIBRARY & MUSEUM Lucy Caswell Retires Short History of the Cartoon Library Brief Biography of Billy Ireland 2010 Festival of Cartoon Art: A Report Celebrating Krazy’s 100th

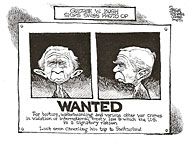

EDITOONERY Revised History of American Editorial Cartooning

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE A Valentine from Thomas Jefferson Machamer

BOOK MARQUEE Art of Modern Rock: Mini No. 2, Poster Girls The Punch Brotherhood Sergio Aragones: Five Decades of His Finest Works

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE John Byrne’s Next Men Returns Fantastic Four’s Human Torch Goes Out ODDS & ADDENDA: Daredevil Reborn, Eisner’s Spirit Carl Barks Celebrates 70 in Disney Comics from Boom! Jake Ellis, Tom Strong Time Travel, John Severin in the Old West, Jordi Bernet’s Hex, The Man of Glass

PASSIN’ THROUGH Bill Crouch Dwayne McDuffie

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

BUT BEFORE WE GET STARTED, if you haven’t inspected our list of Books for Sale, now’s a good time to make the trip. Just click on Books at the left, and you’ll be transported to a list of Great Buys: if these books are not rare and therefore somewhat vintage (as some are), then they’re either brand new or read only once. And the prices are usually less than half the cover price (except for the rare ones, the prices of which scrape the ceiling). Among the numerous treasures for sale are such recent arrivals as: Shameless Art, a spectacular collection of pin-up and paperback book cover art by all your favorites; Chic Young’s Blondie: The Complete Daily Comic Strips from 1930-33; and The Best of Simon and Kirby, showcasing representative works by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, starting in the 1940s and through 1966. Try it; you’ll like it. Now, as we were saying, here we go again—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits EVERY ONE OF MARVEL’S MARCHING MINIONS who cares about such matters now knows that the member of the Fantastic Four who died in issue No. 587 is Johnny Storm, aka the Human Torch. For more, see Funnybook Fan Fare ’way down the Rancid Raves Scroll. ... This may be the first time an animated feature film was in the Oscar competition for Best Picture—“Toy Story 3,” which was also in the Animated Feature category against “How to Train Your Dragon” and, surprisingly, “The Illusionist.” ... .Joanne Siegel, the widow of Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel and the model for Lois Lane, died February 14 in California. She was 93. ... DailyCartoonist sez: BOOM! Studios has announced that it is beginning a new association with Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, and that its kids imprint will henceforth be known as Kaboom! Fantagraphics Books is currently publishing the chronological reprints of the Peanuts strips, so BOOM!'s packaging will presumably employ some other content. Perhaps the old Peanuts comic book stuff. Joe Kubert and Paul E. Fitzgerald have started a year-long blog salute to the Army’s PS Magazine in honor of its 60th year. Fitzgerald was the magazine's first managing editor (1953-1963), and is the author of the 2010 Eisner Award-nominated history, Will Eisner and PS Magazine. He will make “best of” selections from the 227 issues Eisner produced over his 21 years with PS; Kubert, who has just completed his tenth year as the contractor for the magazine’s creative art, design and pre-press services, will make selections from all issues since February 2001, and the magazine's existing staff will choose from issues by the six art contractors between Eisner and Kubert. Of the eight contractors responsible for producing PS, Eisner served the longest; next with 150 issues are Jack and Diane Backes. Murphy Anderson served twice, 111 issues (and he had worked in Eisner’s PS shop). Kubert has so far produced 124 issues and is still the contractor. The blog, which apparently will post new material daily, can be found at thebestofpsmagazine1951-2011.blogspot.com From Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist (February 4), the latest chapter in the Danish Dozen adventure: “The 29-year-old Somali man that allegedly tried to break into Kurt Westergaard’s home with an axe was found guilty. The sentence is nine years in prison plus a fine of nearly $2,000. After being released, he will be expelled from Denmark. Defendant said he just wanted to scare Westergaard, not kill him.” Finalists for the “cartoonist of the year” award (the Reuben) conferred by the National Cartoonists Society (NCS) are Glen Keane (animation), Stephan Pastis (Pearls Before Swine), and Richard Thompson (Cul de Sac), the latter two strip cartoonists have been previously nominated for the honor. The winner will be announced at the Reuben Banquet during the NCS annual convention held over Memorial Day weekend, this year, in Boston. Best known for his character animation at Walt Disney Studios for such feature films as “The Little Mermaid,” “Aladdin,” “Beauty and the Beast,” “Tarzan,” and “Tangled,” Keane received the 1992 Annie Award for character animation and the 2007 Winsor McCay Award for lifetime contribution to the field of animation. Bil Keane, Glen’s father, collected the Reuben for 1982. The last cartoonist in animation to receive the Reuben was Matt Groening who received his for 2002; no other animators have ever won the Reuben. Someday, maybe as early as 2012, the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con might begin with a parade through downtown San Diego. It’s an idea being touted about by City Council President Tony Young, reports Jen Lebron Kuhney at signonsandiego.com Young, a “self-proclaimed comic book collector and sci-fi novel fan,” thinks a parade would be a good way to involve the city in the Con. “The problem with Comic-Con sometimes is that San Diegans can't really participate in all the spectacle,” he told Kuhney. “They can't take part if the Convention Center's full. So this is a way for that guy who's in his Chewbacca outfit or whatever to take his kids and come down and watch this parade. They're going to be hungry, they're going to go to restaurants and they're going to spend money. The other thing is, you know CNN, and all the networks are going to show this. This is going to be a great way to highlight San Diego. The bottom line,” Young ranted on, “is San Diego needs to let its hair down a little. We can get so tied up in some of these major issues, which of course are important, but to be a big city you have to have great events and you have to let down your hair some. I want to see the mayor in his Batman costume that I know he has tucked in the back of his closet somewhere and I want to see him leading the parade.”

***** Calvin Reid at publishersweekly.com reports: “For the first time in its 70-year history, Archie Comics will publish an original graphic novel later this year—a major change for a company that still leans heavily on newsstand sales of single-issue comics and digests for the lion's share of its revenue. The new graphic novel, Archie Babies, will be written by Mike Kunkel, who wrote and drew the first issues of Billy Batson and the Magic of Shazam! for the DC Comics' DC Kids line. The artist for the project is Art Mawhinney, who has worked for DC, Marvel, and Nickelodeon. The book will be distributed by Random House. Archie Babies was originally announced as a monthly series, but Jon Goldwater, co-CEO of Archie, said the company is putting renewed emphasis on graphic novels since signing a distribution deal with Random House last September. "We are going to put a lot of emphasis on our graphic novels," he said. "It is a very, very important part of our business here at Archie Comics." Archie’s latest foray into the future will result in digital versions of its comics being online the same day as print editions hit the newsstands, reports George Gene Gustines at artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com. Postings will begin in April, but already comic shop retailers are a little upset, fearing the web exposure will sabotage sales in their stores. Archie is getting so up-to-speed that politics have intruded into the otherwise balmy afternoons at Riverdale High School. In Archie No. 616, Archie and Veronica are depicted talking environmental issues with President Obama, and Reggie gets his photograph taken with Sarah Palin. “Both political alliances are used for Archie and Reggie to further their campaigns for student-body president,” said Ken Tucker at EW.com’s Shelflife blog.

**** Bill Holbrook, who confounds us all by producing three daily comic strips, writes: “On January 1, the websites for On the Fastrack and Safe Havens (fastrack.com and safehavenscomic.com) were redesigned with new features. Most importantly, they now display the strips themselves in addition to an archive. The purpose behind this is to build an online community around them similar to what has developed for my online strip Kevin & Kell (kevinandkell.com). Basically, I've created three stages of interactivity: A weekly news update, a blog written by one of the strip's characters that allows reader comments, and also a comment section for each individual strip. Reader participation will hopefully create a feeling that they're invested in the strip's success, and will support it financially. That's basically what's kept Kevin & Kell going all these years.” The site also offers book collections of Holbrook’s strips, each containing a year’s strips: Fastrack is in New Hair Day (2005), Merger! (2006) and Bug Zapper (2007); Safe Havens is in Taking Wing (2005), Resident Advisor (2006) and Extreme Vows (2007). Holbrook continued: “I'm currently working on the next Kevin & Kell collection called Honeymoon 2.0, the complete run of strips from 2009. Still in the works is a possible TV series which is in the process of being pitched.” And then there’s a special iPhone/iPad app by the WareTo company, visible here: itunes.apple.com/us/app/kevin-kell/id404235152?mt=8 “An additional note,” Holbrook added last week, “is that one of my Fastrack characters, Dethany the perky Goth, is going to start a Twitter feed and a Facebook wall. The later is still under construction, but the Twitter account was launched last night at twitter.com/dethany_d .”

***** In early February, maus-man Art Spiegelman accepted Angouleme’s Grand Prix honor, knowing that acceptance entails being president of the Angouleme International Comics Festival next year—and that means guiding the festival's exhibits and conferences and programs. "I don't know whether you should say 'congratulations' or 'condolences,' " said Spiegelman when he was interviewed by ComicRiffs’ Michael Cavna. But, he went on, "I didn't think I could say 'no' without causing an international incident of Bush-like proportions." The four-day fest, which debuted four decades ago, now draws roughly 200,000 visitors to southern France. Joking aside, Spiegelman recognizes the Grand Prix as a distinct if perhaps (in his case) misplaced honor: "It would have made sense 15 years ago," he said. "I feel like President Obama and the Peace Prize—the timing's all wrong." It might be wrong, but Spiegelman has scarcely left his 1992 Special Pulitzer Prize for Maus behind: his latest project is "Metamaus," a look back at the landmark Holocaust-memoir graphic novel that is still his best known work.

RANCID RAVES AT THE MOVIES “The New Superman” is on the cover of last week’s Entertainment Weekly (February 25)—in the person of British actor Henry Cavill, who got the part in the forthcoming Superman movie because he wore the costume without inspiring laughter. That was the test. The Laugh Test. Said director Zack Snyder: “If you can put that suit on and pull it off, that’s an awesome achievement.” And Cavill did it. “He walked out and no one laughed,” Snyder said. “Other actors put that suit on and it’s a joke, even if they’re great actors. Henry put it on, and he exuded this kind of crazy-calm confidence that just made me go, ‘Wow. Okay, this is Superman.’” Snyder phoned Cavill with “good news and bad news.” The good news : he got the part; the bad news : he needed to start working out. Cavill was thrilled.. He thinks of the role as “the biggest job in history.” That’s a little extreme, I ween—I mean, bigger than Prez of the U.S.? Bigger than King of the World? Bigger than Rush Limbaugh? But Cavill’s overblown (somewhat) excitement is a measure of the cultural status of funnybook superheroes these days. And the EW cover treatment is another indication that the spandex bunch have Arrived. Nothing is a measure of Human Achievement so accurate as getting into the movies. In our culture, the movies confer the ultimate accolade. They represent the pinnacle of success. Forty years ago, comic book writers were chagrined if they had to admit they wrote comics for a living; if at all possible, in the same breath as their confession, they’d strenuously imply that they were actually working in comics as a way of developing the skills they’d need in their Real Profession, which, they’d say, was writing movie scripts. Nowadays, the two, movies and comic books, have become so intertwined that comics have achieved a respectability and acceptance, and comic book writers need no longer snivel apologetically about their work life. Superman isn’t the only superhero to achieve status through the movies and cover treatment at EW. Batman’s been there; ditto Captain America. And in the “Superman issue” of EW, we find a handy role call of forthcoming superhero movies, a positive orgy of status symbols: Thor gets the season off to a hammering start on May 6 (the door-opener for this year’s Free Comic Book Day on May 7); “X-Men First Class,” June 3; Green Lantern, June 17; Captain America, July 22. Next summer’s offerings are all apparently definite enough that EW can announce opening dates for all but the Wolverine flick: the Avengers will debut on the silver screen on May 4; Spider-Man’s back on July 3 and Batman on July 20. And more—many many more—are doubtless in the offing. One of the more unusual is Matthew Vaughn’s a-borning project. ICv2.com reports that even as Vaughn is still editing “X-Men: First Class,” he’s already thinking about his next project, “The Golden Age,” described as “a saga about the denizens of a retirement home for superheroes, who have to come to the aid of their grandchildren after their middle-aged offspring screw up the world. “The Golden Age” is based on an unpublished comic book series written by Jonathan Ross, the British talk show host, who is a huge comics fan and the author of Turf, which is drawn by Tommy Lee Edwards and published by Image.” The aging superheroes concept of “The Golden Age” is not exactly new, ICv2.com points out. Frank Miller may have initiated the genre with The Dark Knight Returns, and Working Title films has an adaptation of Kurt Busiek’s Astro City in development. Vaughn’s project appears to be in its early stages: he told Deadline that he is not sure if his writing partner Jane Goldman will write “The Golden Age” screenplay, or if he will direct as well as produce the movie. The project is not related to the James Robinson Elseworld's mini-series from 1993, which was also called “The Golden Age,” and which dealt with Golden Age DC heroes entering their twilight years in the 1950s and dealing with McCarthyism. In other celluloid configurations: ICv2.com reports that Adrianne Palicki, who starred as Tyra Collete in “Friday Night Lights,” will play Diana Prince/Wonder Woman in the new NBC series being developed by David E. Kelley. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Kelley’s conception of the Diana Prince character is that of a modern woman who is trying to balance her life as a successful corporate executive, and a crime-fighting vigilante. As I contemplate her physiognomy, Palicki “looks” more like a tough lady WW than, say, the sweetly pretty Lynda Carter of yore.

CONGRESSMAN IN THE COMICS Civil rights pioneer Congressman John Lewis of Georgia is writing a graphic novel about his lifelong crusade for human and civil rights. Lewis began organizing sit-in demonstrations in 1959 in Nashville, Tennessee. In 1961 he was beaten and jailed for his participation in the Freedom Rides that were launched to desegregate interstate bus depots in the South. From 1963-1966 Lewis was Chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He coordinated the Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964, and he led the voting rights march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where the marchers were attacked by Alabama State Troopers on what became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Despite being arrested over 40 times, physically assaulted and severely injured repeatedly, Lewis remained unwavering in his commitment to non-violence. He has served as the Congressional Representative from Georgia’s 5th District since 1986. Entitled March, the graphic novel will be a history of the civil rights movement as well as Lewis’ personal story. It will be published by Top Shelf in 2012. Lewis is writing with his Congressional aide Andrew Aydin, a comic book fan who is the one who put it all together, said Top Shelf Co-Publisher Chris Staros, who lives in the Congressman’s home state Georgia. Reports Vaneta Rogers at newsarama.com: “It all started when Aydin discovered the historic importance of a comic book called The Montgomery Story, which was published by the Fellowship Reconciliation in 1957. The comic told the story of the Montgomery bus boycotts, but also talked about Gandhi, Dr. Martin Luther King and nonviolent social resistance.” When Adyn asked Lewis about the comic book, Lewis said he could remember people saying The Montgomery Story was one of the things that inspired them to join the Freedom Rides. Said Aydin: "I was hooked right there. I started asking him, 'Congressman Lewis, why don't you write a comic book?' He would laugh and smile and sometimes even say maybe." A few weeks passed and Aydin was out on the hustings with the Congressman during the 2008 campaign when a volunteer mentioned something about comic books, prompting Aydin to pose the proposition one more time. This time, Lewis said he’d do it if Aydin would write it with him. Once they started writing, Aydin approached Top Shelf, and Staros was interested. And when he read the script, Staros became enthusiastic about March. "I knew the idea was good, but execution is key. So they sent me the first half of the graphic novel. And Andrew and the Congressman had done a fantastic job with it," Staros said. "It really read like a graphic novel. It was going to convert digitally to comics form exceedingly well. So once I read that, I was elated, because I knew this was a winner. I knew this would be an important literary work." None of my sources here, USA Today and newsarama.com, named an artist who would produce the visuals from the Lewis-Aydin script.

SLINGING AT THE WEBSLINGER The review crew along Broadway in New York has been pouting about the Spider-Man musical. The show has yet to experience an “official” opening: it’s still in a “preview” phase as it tries to work the, er, bugs out of its numerous mechanisms, and until it opens officially, the unwritten rule along the Great White Way is, apparently, that critics refrain from reviewing the production. But the show has itself broken plenty of rules. “It’s had more previews than any musical in history,” says Robert Siegel at NPR—60 as of February 7. And when the “official” opening was postponed again from February 7 to March 15, the critics club balked at tradition. They’re a snotty bunch anyhow (not unlike comic book critics): they act as if Broadway theater was their stage. In any event, the vultures descended on February 8, spewing up 11 reviews. “Every one of them,” as Jeff Lunden reported at npr.com, “—negative.” The Washington Post’s Peter Marks was a little uneasy: “I think it clearly makes you a little uncomfortable to be reviewing something before the production claims it’s quote-unquote ‘ready.’ but the other side of that is this show decided that, you know, it was okay to charge Broadway prices [top price, $275, and sales remain strong throughout the “previews”] while they screwed in the nuts and bolts.” Marks plunged into the fray regardless of his discomfort. Saying the show was 170 spirit-snuffing minutes long, he went on to say it lacked a coherent plot, tolerable music, and workable sets. To be sure, the hero soars over the audience, he concluded, “and yet, the creature that most often spreads its wings in this show is a turkey.” Cute. Ben Brantley at the New York Times is quoted in Time, February 21, from his February 8 review: “The sheer ineptitude of this show ... loses its shock value early. After 15 or 20 minutes, the central question you keep asking yourself is likely to change from ‘How can $65 million look so cheap?’ to ‘How long before I’m out of here?’” At Hollywood Reporter, David Rooney wrote: “What really sinks it is the borderline incoherence of its storytelling.” It is a mistake to include a musical number, “Deeply Furious,” in which “Arachne [a villainess] and her Furies go shoe-shopping before entering the human world. Seriously.” Steven Suskin at Variety doesn’t like the show either and hopes the ever-forthcoming changes will include surgery to remove “Deeply Furious”—“the spiders-in-heels number that is fast developing into musical-theater legend.” Not a good thing, apparently. Charles McNulty for the Los Angeles Times said: “Spider-Man is a teetering colossus that can’t find its bearings as a circus spectacle or as a rock musical. ... Nothing,” he finishes, “cures the curiosity about ‘Spider-Man’ quite like seeing it.” So much for Broadway’s critical chorus, united, it seems, in utter disparagement, leaving only the immortal Glenn Beck as Spider-Man’s champion. John Lahr in The New Yorker (February 28) says Beck has seen the show four times. “With his canny nose for truthiness,” Beck has declared it “the best show I’ve ever seen. Bar none. Heads and shoulders above anything else.” What’s the attraction? Said the guru of dramaturgy: “I want to see if Spide-Man falls on the audience.” Concludes Lahr: “Producers take note: people are paying top dollar for a Flying Wallenda moment.” In the midst of this tsunami of snark, I was happy to see Peter David, an actual comic book guy, wade into the fray in Comics Buyer’s Guide No. 1676 (April). Upon first seeing the topic of his column, I thought maybe his sympathies and his understanding of the source medium and of the characters enacted on stage will dilute his verdict. Maybe not. David begins by accusing carping commentators about the show of “showdenfreude, a variation on the German schadenfreude (enjoyment of other’s problems), it involves bystanders eagerly rooting for, and taking personal satisfaction in, the failure of a tv program, movie or—in this case—a Broadway show.” He continues with a metaphor that seems not to bode well for his final verdict: “‘Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark’ is like a homerun hitter. It doesn’t know how to lay down a bunt or just try to make contact. It consistently swings for the fences. It strikes out more than it should—and with big strokes. When it connects, however, it knocks it out of the park.” Alas, it doesn’t connect very often. Costumes, sets and special effects are “amazing,” David said. And “the Green Goblin and Sider-Man slugging it out while soaring over the audience [is] the most totally immersive super-hero experience I’ve been to since Spider-Man ride at Universal.” And in Act 2, is “a haunting sequence involving a sleeping Peter being seduced in his dreams by the villainess Arachne that is simply one of the most astounding visuals I’ve ever seen on stage, period.” That’s about all the homeruns for David. The first act “stumbles,” he says, “right out of the gate with the introduction of The Geek Chorus.” I suppose it was just too tempting to concoct the modernization of a classical theatrical device, “the Greek chorus” that comments on the action as it transpires. The device has possibilities, David allows—“the discussions they have about free will versus determination (Was Peter Parker destined to be bitten by a spider as opposed to its being random chance?)” are exactly “the kinds of debates one sees on message boards all the time.” David sees a theme buried in the show’s mechanical rubble: “Spider-Man is part of a mythic architecture that goes back centuries and is as old as mankind’s ability to sit around a campfire and say, ‘Once upon a time.’” But the plot that wanders off into Never Never Land in the second act sabotages this ambitious notion. David doesn’t like the music either. Announcements that the show’s opening is being delayed so more work can be done on the book and the songs “is both good news and bad,” he says. “The good news is: thank God; it needs it. The bad news is: Bono and The Edge are coming back to write new songs, while I’m not blown away by the ones they’ve got.” One observation David makes is a welcome scrap of fact that should unhorse much of the commentary about (as Adam Markovitz says in Entertainment Weekly) performers injured by high-flying stunts. (Commentary that I’ve participated in by repeating it here). “It should be noted,” says David, “that none of the injuries since the show opened in previews has been associated with the flying effects.” David’s bottom line about the most expensive musical ever mounted on Broadway is this: “At the curtain call, the audience gave the show a standing ovation because of what the show as—a sheer spectacle, unlike anything else that has ever hit Broadway, that was a culmination of nearly a decade of work. Not a trace of showdenfreude in the house.” Nicely done, Peter, and thoroughly authentic sounding, too.

Magazine Publication, the Web, Fate, Wizard, And Our Deluded Niche Audience as Seen by One Who Pretends to Know A FULL-PAGE ADVERTISEMENT in Time (February 21) claimed that the magazine industry is in a glorious state of fiscal health and expansion. “Barely noticed amidst the thunderous Internet clamor is the simple fact that magazine readership has risen over the past five years. Even in the age of the Internet ... the appeal of magazines is growing. Think of it this way: during the 12-year life of Google, magazine readership actually increased 11 percent.” Dunno what, exactly, the ad is selling. Magazines, I suppose. Conde Nast, a magazine publisher, apparently placed the ad. In any event, if the assertions are true, print journalists aren’t out of work yet. Except, maybe, in the comics niche of the magazine publishing environment. Wizard, the glossy monthly magazine about comics, is no longer in print. Ditto the publisher’s ToyFare magazine. Starting this month, the print Wizard will be replaced by a digital version called WizardWorld. It will cover comic books, toys, and superheroes and the personalities behind them, kittyspride.com announced at the end of January. The publisher recently went public as Wizard World, Inc., and it seems focused now on its program of popular culture shows, the Comic Con Tour, that is supposed to convene all around the country in 12 cities this year. According to Gareb Shamus, Wizard World President and CEO who has, for twenty years (since the debut of Wizard in 1991) catered to pop culture fans, the death of his two print magazines is simply a matter of evolution. Interviewed at ICv2.com, he seemed deliberately to avoid saying that the magazines died as a result of drooping circulation, the slow evaporation of print media generally, or the emerging dominance of the Internet. In fact, he maintained that Wizard was a champion seller to the very end. But times they are a-changin’ and Wizard has to change with them. “The market’s changed,” he said. “When I started 20 years ago, I was pioneering in the publishing world in terms of creating a product that got people excited about being involved in the comic book and toy and other markets, and we could do a lot of really cool and innovative things. Unfortunately right now being involved in the print world is very stifling, in terms of being able to leverage your content and your media and your access to the world out there.” The print world is failing publishers not because of declining readership or advertising (the usual culprits) but because it’s “stifling”—not adaptable enough for the times. And Shamus is all about creating a product for a new market: “Through Wizard World, I’m starting an all new free weekly digital magazine. By doing it digitally, we have direct access to our consumers. There are no intermediaries between us now and our end consumer in all the businesses that I’m in now. When you look at my ability to sell tickets to fans, or get fans excited about our digital offerings now whether it’s through Wizard World, our new digital magazine, or Geek Chic Daily, I have direct access right now to the consumers who are our biggest fans. They’re the ones who support us, they’re the ones who get excited about what we do, and now we have direct access in all areas of the world I live in.” WizardWorld will be on the Web and available in an app download for any format people have access to. And Shamus is not the Lone Ranger in his move into digital ether: at the ComicsPro meeting in Dallas, February 10-12, Diamond Comic Distributors announced a partnership with ComicsPlus reader developer iVerse Media to offer digital comics exclusively through comics retailers, beginning in July.

WHEN THE ICv2.COM INTERVIEWER pointed out that comic book shops have made a lot of money selling the print Wizard and that he was leaving them in the lurch, Shamus admitted no responsibility and shifted the blame for the dire circumstances of retailers to comic book publishers. Wizard, he professed, was a gold mine to retailers: “Until we ceased publishing,” he said, “Wizard probably sold better than 95% or more of every single comic book out there in terms of sheer units. Forget about even dollars because it was a higher cover price.” He said he feels bad for the retailers: “They have a very difficult situation ahead of them. I read a lot of their newsletters in terms of their struggling, their crises, having their worst sales ever.” But that’s not his problem: “The problem is the comics industry has not taken a leadership position in helping these guys. Their sales continue to fall, they’ve been falling for a long time, and nobody’s taken a leadership position in helping these stores pay their bills. I don’t make the product; I make the magazine about the product, so it’s up the people that make the product to figure out how to support the system that gave them their livelihood.” If publishers took the leadership role Shamus urges on them, they could take his company’s modus operandi as a model: “When I go into a city with a show, I do everything I can to sell tickets. I do everything I can to get the word out. I do everything I can to get people to come to the show and have a great time and get exhibitors and get dealers. I do everything. I work with everybody. I do everything I possibly can, and the companies in the [comic book] industry aren’t doing everything they can. They’re picking and choosing when they should be doing everything. Mattel and Hasbro don’t sit there and say, oh well, no tv or no radio, or no this or not that. They work with everybody. They support everybody that supports them.” SHAMUS SEEMS TO VIEW THE DIGITAL MAGAZINE chiefly as a marketing tool for the Comic Con Tour. The inherent strategy of the Tour is to capitalize on two aspects of such events: “When you think about what these events are about,” Shamus said, “it’s really a social gathering of people who are interested in pop culture, whether it’s comic books, toys, games, animation, movies, television, and when you look at people who attend these events, it’s a local thing. ... Consumer shows are really built around consumers that live within a radius of the local market. We’re strategically targeting areas throughout the country where we know there are pockets of people who are interested and excited about what’s going on in the pop culture world.” Hence, the strategy of the Comic Con Tour: “Companies that want to reach this audience don’t want to reach them at one time in one place; they want to reach them all the time all over the place. We’ve found it’s impossible to build momentum when you have one-off events. By being able to create momentum from city to city, throughout the tour and throughout the year, companies and people and artists and celebrities can benefit from being around all the time and building the momentum we can create from city to city.” Shamus was asked about the suppose competition between Wizard World and Reed Exhibitions. Wizard has run the Chicago Comic Con for almost 15 years, and Reed’s running a new show there and in New York. Wizard acquired the Big Apple show and at one point had a show scheduled the same weekend as Reed’s New York Comic Con. But Shamus denied the obvious competition: he thinks Wizard has the superior events: “At the end of the day when we create a compelling event, our audience comes out to see us. I’ve been marketing and promoting and been involved with this fan audience for 20 years now and when I put on an event, my audience responds. So it actually doesn’t matter what anyone else does out there. We don’t have competition. So if someone’s going to spend money with San Diego and not with us then it wasn’t in their budget. We don’t fell like there’s any competition for us.” And then, as if to promote his show over that of the competition’s (because they are competitors as Shamus’ every utterance attests), he veered off into extolling the features of the Wizard Con over all other rivals: “If somebody wants to meet Julie Benz, they’re coming to our show. If someone wants to meet Bruce Campbell, they’re going to come to our show. If they want to meet Felicia Day, they’re going to come to our show. If they want to meet Ethan Van Sciver, they’re coming to our show. Just because Bruce Springsteen is playing and we’re Bruce Springsteen, if some little band is playing across the street, then nothing’s going to stop them from coming to see us in concert. ... There’s nothing that’s going to stop fans from coming to our show if we do a good job and create a compelling event.” And the alleged competition is in the same game: “If people like what someone else is doing, they’ll go to both,” Shamus said. “People don’t just buy one video game, if they want two video games, they’ll buy both. If there are two movies that they want to go to, they’ll go to two movies, but if there’s only one that they want to go to, then they’ll go to one. It’s my position that if we create a compelling event that people will come out for it.” Spoken like a tooth-and-claw competitor.

WITH THE EXPIRATION of Wizard magazine, the venerable Comics Buyer’s Guide (CBG) now stands alone as the only monthly magazine about comics. The Comics Journal went digital in December 2009 (at tcj.com), resorting to print only once a year in a “book format,” the first “issue” of which is coming in at around 600 pages and is poised, even as I scrawl this unrepentent prose, to emerge. At the CBG, editor Brent Frankenhoff can’t help but insinuate a tiny note of victory in his announcement of Wizard’s demise: launched in 1991, Wizard: A Guide to Comics was, Frankenhoff says, “a glossy comics magazine designed to compete with many other comics-related magazines [most obviously, given the deployment of the term ‘guide,’ CBG]. In the years since, all of those publications have changed formats or frequencies or gone out of business”—except, he might have added, but had the surpassing insouciance not to mention, the Comics Buyer’s Guide. Were I he, I must confess, I’d have rubbed my hands in glee and done the happy dance, figuratively speaking, at the ultimate triumph of my magazine. CBG abandoned its weekly newspaper format for a slick-paper color-cover monthly magazine about 4-5 years ago; it was an obvious attempt to meet the perceived competition of Wizard. (But Frankenhoff is careful to note that “others may have perceived a rivalry [between CBG and Wizard, but] we’ve always had friendly relations with Gareb and his staffers at his many shows.” Of course; why not be friends? You can be friends with your competition. No law against that. But friendly relations do not eliminate rivalry.) After a few years going head to head, toe-to-toe, now CBG is the last of its breed still standing. CBG has endured some financial doldrums lately—giving up its monthly “price guide” section, for instance, an expensive luxury these days—but it’s still producing a print edition on a regular schedule. Maybe appealing chiefly to the “collector/speculator” was a canny move, despite my disparaging of it lately. But CBG’s publisher, Krause/F+W Media, has apparently given up on its toy collector magazine: I’ve forgotten its name, but I see no evidence of it at the F+W Media website. Conte Nast’s magazines may be thriving in these straitened economic times (and maybe their cheery ad in Time is designed to lull potential advertisers into buy ads in Conte Nast magazines), but in the universe of comics, survival is a struggle, it seems.

YOUR EUSTACE, 2011 Eustace Tilley, the so-called “mascot” of The New Yorker, is, as he has been for almost all anniversary issues of the magazine, on the cover of the issue closest to the actual date of the first issue, February 25, 1925, where Eustace debuted with the magazine. This year, that issue is the one dated February 14 & 21. Only a few things vaguely at variance with actuality in the foregoing. Rea Irvin’s mockery of the twenties’ Broadway dandy by deploying an image of an antique, the top-hatted Regency boulevardier inspecting a passing butterfly through his monocle, seemed, at the time, oddly out-of-place. But Harold Ross, the magazine’s founder, wholly at a loss as to what to use for the inaugural issue, picked it for reasons he could never explain. Turns out, it was perfect, as we can read at the newyorker.com —“a gentle barb (aimed, in this case, at the city’s fossilized high society” by portraying it with an out-dated image, “and, perhaps, self-mockery (aimed at the fledgling magazine’s own ambitions).” But Eustace was never intended as a mascot. He showed up on the cover of the first anniversary issue because Ross, once again, couldn’t think of anything better. And after two appearances, the tradition was rutted, seemingly, forever. Cartoonist Lee Lorenz, who was the most recently reigning “cartoon editor” (the title was never part of Ross’s wayward vocabulary about his staff) before the current Cartoon Editor (the title now established), Robert Mankoff, told me that the staff struggled every year to contrive something other than Irvin’s insouciant lepidopterist for the anniversary issue and, forever failing, resorted to tradition year after year. And Irvin’s dandy had no name at first. He appeared later in the inaugural year, reports Louis Menand, in a series of humor pieces lampooning corporate promotional advertisements. Written by Corey Ford, these effusions purported to offer an inside look at the way the magazine was produced. Irvin’s image was given a name, Eustace Tilley, and a function, supervising, for example, the felling of “specially grown trees to make paper for The New Yorker.” “Almost all anniversary issues” is correct. Starting in 1994, Irvin’s drawing disappeared for several years as other artists took their turns at re-interpreting the iconic image. R. Crumb started it with Tilley as a callow slacker; R.O. Blechman did a female Tilley. And others had their way with the character. But Tilley returned in his Irvin glory in 2001 and has continued, every year since, with occasional errant divergences. But

the desire to tamper with tradition wells up irrepressibly at the magazine, and

beginning in 2008, the management has sponsored a contest every year to let

outsiders lambast the Irvin tradition. This year, more than 600 iconoclasts

submitted drawings, and the editors picked twelve winners, all of which are

displayed at newyorker.com under the heading we have above; a couple, you can

see hereabouts. As an unabashed luddite traditionalist, I’m happy that the magazine has, for the most part, resumed the anniversary cover tradition by finding another way to permit, even encourage, deviant creativity.

Herewith, An Irrelevant Interlude at the Froth Estate

IT WAS TINA BROWN, magazine journalism’s wunderkind from Britain, who shattered the hoary tradition of the Tilley anniversary cover: she commissioned Crumb’s slacker Tilley in 1994. Brown’s editorial strategy was once described as “kissing the ass of celebrity,” and the first two magazines she rescued from obscurity were periodicals that exploited the famous to titillate their readers. She had established herself as a writer of bright witty prose while still a student at Oxford, but some of her career advances came as a result of her relationships with writers Auberon Waugh, whom she profiled for a student magazine, and Martin Amis, whom she dated for a time. In 1974 at the tender age of 21, she was introduced to Henry Evans, editor of the London Sunday Times, who gave her assignments. He divorced his wife in 1978 and married Brown in 1981. By then, Brown’s freelance writer career was over: in 1979, she had become editor of tiny, almost extinct society magazine Tatler, which she transformed into a modern glossy with covers by famous photographers and interiors written by equally celebrated writers. Tatler’s circulation soared from 10,000 to 40,000. Brown went back to freelancing for a short time after Tatler had been bought by S.I. Newhouse’s Conte Nast in 1982, but then Newhouse brought her to the U.S. in 1983 to advise on Vanity Fair, a venerable magazine he resurrected that year from the grave it had been moldering in since 1936. She advised briefly and then became editor-in-chief in 1984. She described the magazine then as "pretentious, humorless” and not too clever—“It was just dull." She changed all that and made Vanity Fair a notable commercial and critical success, winning four National Magazine Awards As an indication of her editorial sagacity, Wikipedia notes, one of her VF editorial decisions was in October 1990, two months after the first Gulf War had started, when she removed a picture of a blonde starlet named Marla Maples from the cover and replaced it with a photograph of the much better known Cher. The reason for her last minute decision, she told the Washington Post, was that "in light of the gulf crisis, we thought a brunette was more appropriate." It was this kind of so-far-outside-the-box-that-it’s-In instinct would also rescue The New Yorker, another Conde Nast magazine, that Brown was invited to take over in 1992, which she did—reviving yet another moribund periodical. She introduced photography and color to the staid New Yorker’s interior pages and, firing 79 writers over the next few years and hiring 50 new ones, she restored to the magazine the irreverence and lightness of touch as well as the literary voice that she had found in founder Ross’s magazine. Then, with three successful revivals on her resume, she left in 1998 to found the monthly glossy, Talk, another celebrity mag that triumphed until advertising dried up in the wake of 9/11. Talk died in January 2002, Brown’s “very first public failure.” But she had no regrets about embarking on the project, according to Wikipedia, which quoted her: "My reputation rests on four magazines— three great successes, one that was a great experiment. I don't feel in any way let down. No big career doesn't have one flame out in it and there's nobody more boring than the undefeated." A celebrity herself by now, Brown went on to a career in talk-show tv then wrote a book about Princess Diana, further polishing her reputation. Then in October 2008, she teamed with Barry Diller to launch The Daily Beast, an online news magazine that mixes original reportage with news aggregation and a touch of sensationalism. It was almost immediately successful, and last fall, when The Daily Beast merged with the foundering Newsweek magazine to form The Newsweek Daily Beast Company, Brown emerged as Editor-in-Chief of both. I was preparing to let my subscription to Newsweek lapse, but when I heard of Brown’s arrival there, I renewed—chiefly to see what she would do with the magazine. Until the February 21 issue, nothing much was in evidence. Newsweek under prior management had abandoned news in favor of in-depth features on current events and a plethora of opinion columns. That continued. Then with the February 21 issue, the Brown touch began surfaced: the cover was a vast expanse of white with a tiny picture of Obama in the lower right hand corner and a screaming headline in 96-point extraboldface type—“Egypt: How Obama Blew It.” The cover story was the inaugural column by a British historian turned pugnacious journalist, Niall Ferguson, known for “counterfactual history.” Counterfactual history is a form of historiography that uses “what if” situations to examine the relative importance of an event, incident or person that the counterfactual historian is negating, saith Wikipedia. For instance: What would have happened if Hitler had drunk coffee instead of tea on the afternoon he committed suicide? Probably nothing different: he would probably have committed suicide anyhow. But if the assassination attempt in July 1944 had achieved its objective, the extermination of Hitler, the probable result would have been the end of World War II. Thus, counterfactual history, in this case, proves “how important Hitler was as an individual and how his personal fate shaped the course of the war and, ultimately, of world history.” This is the guy Brown has brought on board to help her rescue Newsweek. In his curtain-raiser, Ferguson says we’ve just witnessed a “colossal failure of American foreign policy”: when Egyptians swarmed in the streets of Cairo, Obama had a “historic opportunity” to align the U.S. with the “revolutionary wave” sweeping across the region. Instead, Obama dithered. But it wasn’t all his fault: the real responsibility for this failure rests with the people he has surrounded himself with, namely National Security Council members who haven’t formulated a “grand strategy” to resist the spread of radical Islam, to limit Iran’s ambition to dominate the Middle East, to contain the rise of China as an economic rival, and so on. Naturally, Ferguson offers no alternative here, counterfactual or factual: he has no “grand strategy” to offer. Perhaps because he doesn’t want to admit that no single nation, even one as presumably powerful as the U.S., can dictate the fates of other nations. But counterfactual historiography ought to have come to his aid. What if the U.S. had jumped in to support overtly (instead of covertly) the Egyptian protesters? Without much question, the result would have been to lend support to Hosni Mubarak’s claim that the uprisings were being driven by a foreign power. And that might well have inspired the Egyptian military to suppress the demonstrations, thus foreclosing on the possibility of their succeeding. Instead, Mubarak was forced out. Counterfactual reasoning proves Obama did exactly the right thing. You can’t argue with success, said Thomas DeFrank in the New York Daily News, quoted by The Week magazine. Mubarak is gone. America’s relationship with this vital strategic partner is intact, and Obama “burnished his image” by managing a foreign-policy crisis that ended in a positive, peaceful way. Actually, The Week continues, paraphrasing Aaron Miller in Foreign Policy, the White House was smart to keep its distance from this crisis. The U.S. has supported Mubarak for decades out of pure self-interest, so to turn on him too quickly and too decisively would have seemed hypocritical [and might have persuaded other American allies in that region and elsewhere to doubt U.S. reliability—and if the U.S. cannot be trusted, what happens to alliances worldwide?] Obama’s only real option was the one he took: walking the political tightrope in his public statements while, behind the scenes, pressuring Mubarak to leave. In the end, Obama played a bad hand pretty well. In any event, from the evidence of the Newsweek cover of February 21, it’s clear that Brown’s rescue operation for the magazine is to emphasize the opinion columns in the most sensational tub-thumping way possible. It’s celebrity journalism in another guise.

***** IT GLADDENS MY HEART to be able to report that Ferguson is not as humorless as the ferocity of his prose would suggest he is. In his second outing at Newsweek (where he enjoys the lead-off position in the magazine), he turns to the deficit and suggests a cure: sell or lease sections of the Interstate to private enterprise for whopping fees, which will wipe out the debt in no time. Leading up to this massive remedy, he pens this penetrating observation about how we got into this fiscal mess to begin with: “The root of the problem is, of course, a lack of political will, extending down from the president himself to the lowliest Tea Party activist living on Social Security and Medicare.”

Irrelevant Interlude Over: Return to Regular Regaling

ANNIVERSARIES SOME MORE. The immediately expiring year marked the 70th anniversary of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories (see Funnybook Fan Fare up ahead). And it was the 100th anniversary of Krazy Kat. Two signal events that we ought to have commemorated extensively here at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer; but, alas, following the example of the inestimable Homer, we nodded off instead. Propensity of the gaffer. We also missed heralding the 100th birthday of Herge, creator of Tintin, in 2007. In preparation for that, I tried to read all of Tintin and got about half-way through. Maybe some other day. I just got a copy of Pierre Assouline’s Herge: The Man Who Created Tintin, which, by quoting directly Herge’s first wife, substantiates, at last, the innuendoes of previous books about Herge to the effect that his first wife, Germaine nee Kieckens, didn’t love him much, which serves to explain and perhaps excuse Herge’s having an affair with a colorist on his staff while still married to Germaine. Later, after divorcing Germaine, he married his paramour, Fanny Vlamynck. Since most of the previous biographies were produced by persons with close ties to the Herge establishment, operated to a large extent under the watchful eye of Herge’s widow, the aforementioned second wife Fanny, the biographers’ slighting remarks about Herge’s first marriage and wife seemed like slurs, perpetrated to enhance the reputation of his second wife—take a breath here—rather than ascertainable fact. But Assouline, by quoting the first wife, Germaine, directly, confirms the erstwhile slights as fact not spiteful fiction. Assouline’s book, which I’ve only browsed through, not read with thorough attention, covers Herge’s love life in some detail (although not at all salaciously). In 1960, after 28 years of marriage and a four-year affair with Fanny, Herge left both women. Briefly. Then Fanny forced the issue, and Herge separated from Germaine. But it would take 17 years for her to grant the divorce. “Throughout, Germaine clung to the hope that he would return. He did not abandon her, either materially or morally. Until the end of his life, he would spend Mondays with her in what had been their home in Ceroux-Mousty.” If the rest of the book is as detailed and fastidious as this, it’s a fine biography indeed. No pictures, though. Not even a photograph—except one of Herge on the dust jacket. Odd.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment (and much of what follows immediately) is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS “We have to believe in free will. We have no choice.” —Isaac Bashevis Singer Things to remember when you’re growing up and older: “Never pass up the opportunity that a restroom affords, don’t ever waste a hard-on, and never trust a fart.” —Edward Cole (Jack Nicholson in “The Bucket List”)

BLACK HISTORY MONTH Reprising Black Cartoonists Last year during Black History month (February), we paused in our headlong dash to the Next Thing to remember and recognize the marks that some African American cartoonists have made in the medium of newspaper comic strips and elsewhere in cartooning. We began with our discovery of Tempus Todd, a comic strip that started in 1923 and may have been the first strip with an adult male African American protagonist. Until Todd’s advent, most African American characters in cartoons and comic strips had been children, or, if adults, they filled secondary roles as servants or other kinds of menials and fools, importing their imagery and comical conduct from black-face minstrelsy, which is to say, not from actual African Americans but from whites with burnt cork on their faces, “caricatures derived from the popular stage routines of white males’ gross parodies of ‘black life,’ originally the slave life of blacks,” according to Steven Loring Jones in “From ‘Under Cork’ to Overcoming: Black Images in the Comics” at ferris.edu. Tempus Todd, as the star of his own strip, represented, therefore, a marked departure in role if not in portraiture. The strip was written by Octavus Roy Cohen, a Jew from Charleston, South Carolina, who started as an engineer, graduating from Clemson Agricultural College in 1911, but soon turned to journalism, working on several newspapers around the South before deciding to study the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1913 and hung his shingle in Charleston, but when he sold his first short story in 1915, he quit the law and concentrated on writing fiction. I first ran across Cohen in the pages of the Saturday Evening Post, where he achieved some popularity (as well as a measure of notoriety in literary annals) with stories featuring egregious comic stereotypes of African Americans, who spoke an exaggerated “black dialect” that Cohen deployed for comic impact. They were, in effect, still “under cork.” The stories, usually starring a “sepia gentleman” named Florian Slappey, known as the “Beau Bummell of Bumminham,” were handsomely if stereotypically illustrated in gray wash by J. J. Gould, a mainstay at the Post since early in the century. The eponymous Tempus Todd of the comic strip, however, was drawn by H. Weston Taylor, who also did work regularly for the Post. In a 1997 Newspaper Research Journal article analyzing black images in comic strips, Sylvia E. White and Tania Fuentez say that Tempus Todd’s all-black cast is depicted “as individuals” and that Taylor “avoided the traditional minstrel face (protruding white lips, bulging round eyes in a totally black face).” I haven’t seen any more of the clickingly christened Tempus Todd than the drawing we posted at Opus 257 (where these paragraphs first appeared, just last year), which appears at lambiek.net under Taylor’s name, but with no more evidence than this before me, I’m not sure I’d agree that Taylor avoided “protruding white lips” and “bulging round eyes” although Todd, if this is he, doesn’t have the totally black visage and grossly liver-lipped portrayals typical of the day. Todd is a cab driver, say White and Fuentez, and the comedy in the strip arises in his encounters with his passengers, all of whom spoke in the minstrel dialect that Cohen had perfected for characters of color. With only White and Fuentez’ cryptic paragraph for guidance, I don’t know when Tempus Todd ended, but Taylor pursued cartooning in the infant comic book industry, working 1940-42 in the Jacquet Shop, where he produced features for Centaur comics (“Dr. Synthe,” “King of Darkness,” and the briskly named “Dash Dartwell”), Novelty (“Lucky Byrd”), and Quality (“Scarlet Seal,” “Ace of Space,” and “Counterspy”) before dropping from sight. After Tempus Todd, African American characters in mainstream newspaper strips reverted wholly to their traditional subservient comic relief roles, playing the buffoon in white society—portrayals that white readership could countenance because they presented blacks in non-threatening ways. Moreover, as Jones points out, “The image of the stereotypical black servant or fool permitted middle-class white audiences to vicariously indulge in attitudes and behaviors otherwise off limits in ‘genteel’ society. At the same time the pathetic black character offered the white working class an image to whom they could feel superior, no matter how bad their lot in life might be.” Black community activists were outraged at the picture of blacks as “ebony humanoid clones,” Jones continues, and occasionally forced such raw unfeeling caricatures out of the newspaper, sometimes through court action. In the early 1930s, a comic strip based upon the popular radio program “Amos and Andy” was cancelled due to black objections. Until quite recently, only in black ethnic newspapers did African Americans find themselves in positive, identity-affirming positions in the funnies—the most celebrated, probably, was produced by Harlem’s fabled black cartoonist Oliver Harrington. For more about Harrington and his single-panel creation, Dark Laughter, re-visit Opus 257, where we also survey the landscape populated by Torchy Brown and Bungleton Green and the creations of Morrie Turner, Ted Shearer, Ray Billingsley, and Milton Knight. We didn’t explore much the contemporary achievement of Aaron McGruder or Keith Knight, but that’ll come along later. Meanwhile, celebrate by re-visiting last year’s festivities. For even more about African American cartoonists, use your browser to find Pioneer Cartoonists of Color, a website operated by Tim Jackson, a black editorial cartoonist at the Chicago Defender.

***** Sadly, before Black History Month was over and just as we were getting ready to post this Opus, a seminal figure in the history of African Americans in comics died. Dwayne McDuffie, on February 21. Scroll down to “We’re All Brothers...” for a too hastily assembled assessment of his role and tributes.

CRITICISM AND UNWITTING SELF-SATIRE You may remember a short contretemps we had hereabouts a year or so ago in which I unburdened myself of a few thoughts about Stephan Pastis’ drawing ability in his widely beloved comic strip, Pearls Before Swine. Among other things, I said Pastis insulted his colleagues by drawing less expertly than his ability would allow. Some of Pastis’ colleagues got all wee-wee’d up about it, kidnaped me and tied me to a stake and then set fire to the stake. I burned up. Pastis, however, is smarter than all of us. On the back cover of his latest Pearls reprint, When Pigs Fly, he publishes the following blurb: “Pastis is an arrogant egomaniacal blowhard who scoffs mercilessly at his readers and his fellow cartoonists. How can I say that? Come now: anyone who names his comic strip Pearls Before Swine is expressing an overweening disdain for his readers. Day after day, he casts his ‘pearls’—his comic strip—before the ‘swine,’ his readers. The conclusion is inescapable.” The quotation continues: “When he draws his characters in a way that they resemble hors d’oeuvres on toothpicks, we know he’s doing minimal work, artistically speaking. In effect, he’s ridiculing his hardworking fellow cartoonists, many of whom spend almost every waking hour making the elaborate drawings in their strips. I can almost hear Pastis scoffing: ‘You fools! You spend your lives pushing ink around on paper, but I have achieved fame and fortune with the barest resemblance of drawing in my strip. Don’t you wish you’d thought of this?”—R.C. Harvey This quotation is followed immediately by this: “You fools! You spend your lives pushing ink around on paper, but I have achieved fame and fortune with the barest resemblance of drawing in my strip. Don’t you wish you’d thought of this?”—Stephan Pastis Not only does Pastis get the last laugh, he proves that, all along, while everyone around him was setting their hair on fire and running around screaming, he, with his pervading sense of self-deprecating humor, saw comedy where others saw only bad manners. I

finally met Pastis, by the way, at last summer’s Sandy Eggo Con. Jeff Keane,

president of the National Cartoonists Society, had to step between us to

prevent Pastis from tearing my throat out, a moment of high dudgeon captured in

this photo taken by the omniscient Keith Robinson. Thanks to the back cover blurb, we know, now—as we never knew before—that the title of Pastis’ strip is ironic, sarcastic of course, but also deeply ironic, just the sort of thing a twisted albeit self-deprecating mind might toss off in an attempt at humor. And as we arrive at this Truth, I must confess another. When, years ago, I was formulating an opinion about Pearls Before Swine, I wrote disparagingly about the so-called drawing displayed in it. Pastis was favored by Scott Adams, whose Dilbert was yet another offense to artistic sensibility. Both, I thought, were greasing that slippery slope to mediocrity in picture-making—the sort of thing that Jackson Pollock might enthuse over but that I was appalled about. But when I came up with the notion that the name of the strip was an overt insult to its readers and that Pastis’ characters looked like hors d’oeuvres on toothpicks, my critical acumen ran away with me. Seduced by the convoluted reasoning I was committing, I didn’t realize, until some months later, that my analysis of Pearls Before Swine, with its inherent insult and its hors d’oeuvres, embodied a shrewd (if unconscious) satire of intellectual or academic criticism. It was literary criticism gone completely out of control, barking mad. I was, inadvertently of course, satirizing myself.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping IN GARRY TRUDEAU’S DOONESBURY for Sunday, February 13, Mark Slackmeyer, radio personality, is musing: "What are we like as a people? Nine years, ago we were attacked—3,000 people died. In response, we started two long, bloody wars and built a vast homeland-security apparatus—all at a cost of trillions! Now consider this. During those same nine years, 270,000 Americans were killed by gunfire at home. Our response? We weakened our gun laws." A reader asked PolitiFact about the accuracy of that number—270,000 Americans killed by gunfire at home. And editor Bill Adair examined the evidence and determined that Trudeau was Mostly True. “Mostly” requires a little amplification. Adair contacted Trudeau, who said he had extrapolated the number, using the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For six years, Trudeau discovered—from 2002 through 2007—the number of gun deaths per year was pretty stable, “around 30,000. So in my judgment, multiplying 30,000 times nine yielded a figure reasonable and accurate enough for rhetorical purposes without using hyperbole. If anything, it may be slightly on the low side." “We found that Trudeau was basically right,” Adair said. Using the same source, he came up with a slightly higher number (281,757) “because we not only extrapolated out through the end of 2010 in our calculations but also included the final three months of 2001.” The number included all gun deaths in several categories: suicide, homicide, accidental, legal shootings and “undetermined.” What gave Adair pause, however, was Slackmeyer’s qualification—“at home.” If that means in or near someone’s home, Trudeau’s number couldn’t be correct, Adair said. But when he asked Trudeau about it, the cartoonist clarified: "I didn't say ‘in the home,’ I said ‘at home’ as opposed to abroad, where the wars are. Failure to communicate clearly, I guess. Rats." I read it the way Trudeau intended it to be read: in context, Slackmeyer is contrasting deaths in the U.S. (“at home”) with “two long bloody wars” overseas. But Adair wasn’t entirely persuaded: “Reading through it again, we think Trudeau’s explanation sounds reasonable. But we decided to mark Trudeau down slightly because we think it’s also reasonable for people to make the same initial assumption we did, that ‘at home’ means in or near one’s home. So we’ll rate the comment Mostly True.” Mostly fair, I say.

Feverish Foonit. We pause, here—a fittingly theatrical gesture—to note the return to Rancid Raves’ digital ether of this department, Newspaper Comics Page Vigil, wherein we marvel at the bump and grind of daily comic stripping. For the past 15 months, we’ve been perpetrating this watchdog function at The Comics Journal website, tcj.com, in a regular thrice weekly blog, Hare Tonic. But the Journal Management, ever questing for engaging ways explore its domain, has re-purposed the site, eliminating blogs. So we’re back.

JIVEY DEPARTMENT Jim Ivey,

you’ll readily recall, is a political cartoonist, former curator of his own

cARToon Museum in Madeira Beach and, later, in Orlando, and all-time beach

AMONG THE HORDES AT THE CARTOON LIBRARY’S HOARD Caswell Retires—Almost Lucy Shelton Caswell has been curator of the Cartoon Library since it was called the Milton Caniff Research Room at its founding in 1977. The Library is now called the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum because it has outgrown a “room” and now archives much much more than Caniff’s papers, the donation of which instituted this unique special collection of the Ohio State University Libraries. After 33 years, Caswell announced her “semi-retirement” as of December 31. The new curator is Jenny Robb, erstwhile Caswell’s assistant (and onetime student), who left the OSU campus briefly to be director of the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco (cartoonart.org). But Caswell will re-appear in the Cartoon Library as curator of special projects, chief among them, the renovation of Sullivant Hall as the new home for the cartoon holdings. When it opened, the Library for Communication and Graphic Arts (a more dignified, institutional name than Milton Caniff Research Room even though the latter was on the bronze plaque at the door) occupied two converted classrooms in Ohio State's Journalism Building at 242 West 18th Avenue. From this inauspicious beginning, Lucy Caswell spent the next three decades building the Library into “the widely renowned facility it is today, one of the most admired and sought-after caretakers of legacy collections” as press releases put it. Thousands of donors have contributed to the collection, with gifts ranging from one item to tens of thousands. The first donation came from another OSU alumnus, illustrator Jon Whitcomb. Then came the Philip Sills Collection of over 100,000 motion picture posters and stills dating from 1927 to 1964. After that, dozens of cartoonists seeking a secure place to deposit usefully the remnants of their life’s work found the Cartoon Library. Sometimes they sought out Lucy; sometimes, she cultivated potential donors and secured their materials. The Will Eisner Collection was established in 1984 and additions were received following his death. Other cartoonists who have their work archived in the Library include Nick Anderson, Jim Borgman, Eldon Dedini, Edwina Dumm, Walt Kelly, and Bill Watterson. The Jay Kennedy Collection includes more than 9,500 underground comic books, one of the most extensive in the world. The records of several professional organizations—the National Cartoonists Society, the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, Newspaper Features Council, and the Cartoonists Guild—are archived in the Library. In 1992, the Robert Roy Metz Collection of 83,034 original cartoons by 113 cartoonists was donated by United Media, and in 1998, Bill Blackbeard, director of the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art, donated its collection, the largest aggregation of newspaper comic strip tear sheets and clippings on the globe. In 2007, the entire holdings of the Mort Walker’s International Museum of Cartoon Art (IMCA), numbering more than 200,000 originals, was transferred to the Cartoon Library and Museum with the caveat that the art be regularly displayed in a suitable permanent gallery—hence, the Sullivant project. With the addition of the IMCA's extensive permanent collection, the Cartoon Library now houses more than 450,000 works of original cartoon and comic art, 50,000 books, 61,000 serial titles, 3,000 linear feet of manuscript materials, and 2.5 million comic strip clippings and newspaper pages. The Library also has an extensive collection of Japanese manga. In addition to fulfilling its basic mission to develop a comprehensive research collection documenting American printed cartoon art, archiving and organizing materials and providing access to them, the Library, according to its brochure, “promotes the study and appreciation of the art form by sponsoring a variety of educational programs and publications including exhibitions, catalogs, lectures and panel discussions.” For a time, it also published a scholarly journal of cartoon and comic art studies, Inks (1994-97). But its most consistent outreach program is the triennial Festival of Cartoon Art, which I’ll report on as we unroll the scroll. Now arguably the world's largest collection of cartoon art and comics material, the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum is currently located in the lower level of the Wexner Center for the Visual Arts complex. Its new, permanent home in Sullivant Hall will expand its space from the current 6,808 square feet to more than 40,000 gross square feet, with a spacious reading room for researchers, three museum-quality galleries, and expanded storage with state-of-the-art environmental and security controls. The addition of exhibition galleries dedicated to cartoon art will facilitate public display of the Library's extraordinary collection and satisfy the IMCA’s proviso.

I HAVE KNOWN LUCY CASWELL as a professional colleague for nearly 30 years. It seems strange to me to realize the length of this relationship: most of the people I’ve known for three decades, I’ve known since we were children together, and Lucy and I were never children together. I met her in 1982 at the 75th birthday party held at Ohio State University for Milton Caniff, whose “definitive biography” (his term) Caniff had invited me to write. At the time, I recognized that Lucy was an exceedingly nice person—too nice, I thought, to have allowed herself to fall in with such a disreputable gaggle of people as cartoonists almost inevitably are. Nothing much has happened in the years since to change my mind. I still believe all of that—she’s still too nice, and cartoonists still gaggle disreputably. But along the way, I’ve learned more about Lucy. I am a chronicler of cartooning; and she is the keeper of the pertinent trove. It was inevitable, given the mission of the Cartoon Library and my obsessions, that we would spend more time together than was possible at the Caniff birthday fete. A couple years later, I returned to OSU to became one of the first persons to make extensive use of the holdings of the Cartoon Library in assembling material for the biography. I spent a week pawing through the papers that Caniff had bequeathed to the University. I came back on other occasions to continue the research, but that first week was the most memorable. In those years of the infancy of the Cartoon Library, it was housed in three small rooms in the old Journalism building. Researchers like me were supposed to do their work in the first of the rooms. In the other two rooms, the holdings of the Library were archived. As soon as I unpacked my pencil and paper in that first room, Lucy explained the protocol. She presented me with a loose-leaf notebook, the pages of which listed the Caniff materials available. I was to thumb the pages and pick which of these hundreds of items I wanted to inspect and read, and Lucy’s assistant would disappear into the two-room bowels of the Library, find the item I’d asked for, and bring it out to me, so I could read it seated comfortably at the table in the front room. This system, for all its admirable aspects, soon revealed an unfortunate drawback. The catalogue notations on the pages of the loose-leaf notebook were, of necessity, cryptic rather than amply descriptive. And so when Lucy’s assistant, Luther Boren, brought me the first item I requested, I knew at a glance that it wasn’t, quite, what I’d expected. So Luther took it back while I picked another item, and then he disappeared again to retrieve it for me. This next item, like the first, was not what I thought it would be: it didn’t contain the sort of information I was looking for. So I tried again. Luther disappeared again. Again, no luck. This procedure, due, doubtless, to my own lack of perspicacity and experience as a researcher, was simply not working. At this rate, I would wear out my thumb and Luther his shoe leather long before I discovered anything useful for the Caniff biography. Lucy, bless her, realized the fruitlessness of this endeavor long before I did. And she immediately took remedial action. She told me to take my pad and pencil and the catalogue notebook into the second of the three rooms, where there was a work table I could sit at. There, I was closer to the material I wanted to inspect—namely, Caniff’s records, syndicate proofs of his comic strips and some original art, and, most important, his correspondence, which, filed by year, was immediately behind me in a dozen or more filing cabinets that had been transported, whole, from his studio. Lucy then invited me to help myself to the files, provided I would be exceedingly careful to return each of the files to its appropriate place in the filing cabinet when I’d finished with it. I was happy to agree. And Lucy started holding her breath. I hasten to say that nothing this informal prevails at the Library these days. Today’s researchers, among whom I am still numbered, adhere religiously to accepted protocols that are designed to preserve the material in pristine condition while also assisting the researcher. Today, we have to wear white cotton gloves to handle any of the materials we want to inspect. But we still start with catalogues—i.e., looseleaf notebooks with pages of cryptic annotations. Still, I hesitated before committing this anecdote. I suspect that had the Grand High Director of Ohio State University Libraries known that Lucy had let me into the inner sanctum sanctorum and permitted me to rummage through the files willy nilly, Lucy might not have lasted until such an occasion as official retirement, semi- or wholesale. But those were the early days of the Cartoon Library, and all of us were sort of feeling our way. I learned, and Lucy learned. And the Cartoon Library grew and grew until it is now the country’s foremost research facility in the history and art of cartooning. And I doubt that it would have grown to such impressive dimensions if Lucy had not been the kind of curator she was then and is now. There is an entirely practical reason for such special collections as this one, and, as Lucy demonstrated in the Milton Caniff Research Room during my first visit there, she knew the practicalities and could adapt to serve them. The practicalities have no doubt changed greatly as the collection grew, and perhaps such solutions as Lucy found in those early days would no longer apply (or be acceptable) now. But Lucy can find a way. She found a way to assist me in my baptism as a researcher, and she found a way to bring to publication the biography that I finally wrote about the man whose papers started this special collection, a man whose talent and dedication shaped the newspaper comic strip medium, and the cartooning profession, in ways few others have. And I have no doubt that Lucy has found other ways to achieve other objectives over the last 30 years. She is, after all, an expert in practicality. She is also dedicated as few are to the preservation of as much of the history and artifacts of cartooning as possible. But it was her practicality that impressed me 28 years ago, and continues to impress me. And she is also—above and beyond dedication and practicality—too nice to have fallen in with such a disreputable lot as cartoonists.