|

|||||||||||||

Opus 269 (November 7, 2010). Our Big Stories this time include reviews of the life and work of Milt Gross as reflected in Craig Yoe’s new book; IDW’s new Secret Agent Corrigan reprint; and appreciations of the work of two cartoonists who left us last month—Leo Cullum and Alex Anderson. Shorter articles on spiked editorial cartoons, candidates to replace Cathy, comic book future as seen from Portand comic shops, an unusually long news report, and more, much more. (Not to mention, in other words, the usual political screed, this time inspired by the recently deceased election.) Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US Doonesbury in Plethora Great Pumpkin Cleats No More Searching for Cathy’s Successor Portland Foreshadows Comics Future? Homer’s Religion Hip and Hoodie Superman? Cartoons in American Heritage Conan’s 40th at Marvel Comics Turn Pink Hefner Documentary & Playboy Cartoon Count Updated

EDITOONERY Campus Cartooners Chastised Spiked Cartoons

THE FROTH ESTATE Juan Williams Mike Thompson and Bill O’Reilly

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Boobs Covered Tea Party Strips Iron Jaw Returns

Sex in America The Prostitutes of 1880 The Prostitutes of Craigslist

BOOK MARQUEE The Odyssey Graphic Novel

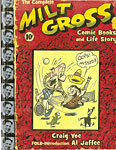

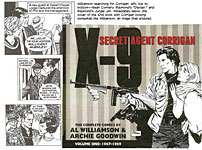

BOOK REVIEWS The Complete Milt Gross: Comics and Life Story Secret Agent Corrigan by Al Williamson and Archie Goodwin

PASSIN’ THROUGH The New Yorker’s Leo Cullum Bullwinkle’s Alex Anderson

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits On October 26, Doonesbury reached the 40th anniversary mark, and festivities broke out all over. Rolling Stone’s November 4 issue has a long interview with creator Garry Trudeau, and SLATE is featuring a dozen articles, including several with nicely provocative titles: “Me and Uncle Duke” (“what happened when Hunter Thompson told me Garry Trudeau was spying on him”) by arch conservative Nicholas Von Hoffman; “Uncle Duke is My Hero” by Walter Isaacson; and another interview with Trudeau (on his stamina, the difficulty of satirizing Obama, and “the most bizarre attack on his strip ever"). In addition to all that effusion, two coffee-table style books came out last month: 40: A Doonesbury Retrospective, an 11-pound tome that gathers, according to Trudeau’s estimate in his introduction, a mere ''13 percent of the over 14,000 published strips” accompanied by 18 character essays by the cartoonist; and Doonesbury and the Art of G.B. Trudeau, the only one of the two that I’ve actually seen (272 9.5x11-inch landscape pages, b/w and color; from the University Press of Trudeau’s alma mater, Yale; $49.95) by Brian Walker, who says, at SLATE: “I have long felt that Doonesbury creator Garry Trudeau hasn't received adequate recognition for his talents as an artist and graphic designer. His strip, which earned a reputation for being poorly drawn in its early days, has been one of the most graphically innovative strips on the comics pages since the mid-'80s. And Garry's art has never been confined to the strip. In 1983, I curated the Doonesbury Retrospective at the Museum of Cartoon Art. While researching this exhibition, I had seen illustrations, sketches, and designs Garry had done for special projects. I knew there was a wealth of other material waiting to be uncovered.” And he has uncovered lots of it. This book, which I’ll review at greater (and doubtless more tedious) length later—when I also get my hands on Retrospective—will lay to rest, finally, the contention that Trudeau can’t draw.

SPEAKING OF ANNIVERSARIES, it’s the 50th for Frederico Fellini’s classic “La Dolce Vita.” ... The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported on October 19 that American Splendor creator and Cleveland native Harvey Pekar died July 12th of an accidental overdose of two anti-depressant medicines, according to the Cuyahoga County Coroner's Office. No foul play; but then, I didn’t think there was. Ironic, though—and Pekar would doubtless be the first to appreciate this—that the famously grumpy Pekar should die of anti-depressant meds. ... The next print edition of The Comics Journal, No. 301, has ballooned to about 600 pages, we’re told, and won’t appear until early next year. They vowed the print version would be like a “book,” and it looks like that’s what it’ll be, kimo sable. (Looking at what’s happened to this installment of R&R, I can understand how the subjects being written about sometimes run away with the horse they climbed on, willy nilly.) ... New York magazine reported that Jim Russell, the disgraced GOP House candidate in Westchester who wrote an article warning of the evils of interracial mixing, is suing various journalists for $1 million, alleging that they “smeared his name” by pointing out how racist he is. Among those being sued is Matt Davies, Pulitzer-winning editoonist at the Journal News in White Plains. ... In Entertainment Weekly (Reunions Double Issue): “You know New York Comic-Con has gone to hell when the plushies start showing up” (with a picture of some sort of hairy being—maybe a human in costume? Maybe not?). Howard Kurtz in the Washington Post quoted Jon Stewart who told National Public Radio last month that, in his view at least, he and Glenn Beck are not so different. Said Stewart: "He's a reaction to what he feels like is the news, and so are we. We actually share quite a bit in common in terms of, not point of view necessarily, but reason for being. We're both in some ways an op-ed. We consider ourselves editorial cartoonists in some respect." To which one editooning wag responded: “He's so right, although I'd venture they're really more political cartoon characters than cartoonists, especially if you throw Colbert in there. Still, I think we should all be flattered.” The latest edition of the Guinness World Records, which goes under the 2011 banner, says unequivocally that the San Diego Comic-Con is the world’s largest comic convention. It has other things to say about the comic book firmament, among them, that X-Men No. 1 recorded the highest print-run of any funnybook, 8.1 million. The first graphic novel that called itself a graphic novel was Bloodstar by Robert E. Howard; but others came in close—George Metzer’s Beyond Time; and Red Tide by Jim Steranko. Joe Simon, born in 1913, is the oldest living comic book writer. (I suppose it’s impossible to have the oldest dead comic book writer, so that expression—oldest living, which I deployed here—is tautological. Sorry.) The United Kingdom’s Dandy magazine, launched December 4, 1937 and still publishing, is the longest running weekly comic book; our home-grown Detective Comics, dated March 1937, is the longest running monthly comic book, and it’s older than Dandy. The most banned book, which distinction it has enjoyed every year since 2006, is And Tango Makes Three about two male penguins who raise a baby penguin; the cause of the banning (surely you saw this coming) is that it promotes a homosexual life style. According to an article posted on HuffingtonPost, Homer Marciniak was looking for buyers for his collection that he started when he was six years old. The collection was valued between $40,000 to $100,000. Police suspect that Homer approached Rico Vendetti, a tavern and restaurant owner who once owned a collectibles business and that Vendetti and an accomplice entered Homer’s home to steal the collection. During the robbery Homer was allegedly hit in the face requiring a hospital visit. After police questioning the next day, Homer died of a heart attack.

AMERICA REDOUX The November 5 issue of Entertainment Weekly has Captain America on the cover—namely, Chris Evans, the final choice to play the part in next summer’s movie, wearing the modified iconic costume. Instead of the traditional flag-striped gala, the new uniform mutes the colors, substitutes a leather jacket for the chain-mail, and encumbers the actor with suspicious accessories— leather gloves, boots, and harness with straps, buckles, and belts. No pictures of Evans wearing the helmet with the little wings, though. Evans turned down the part three times because he was afraid it would lock him into the role for his entire career (the contract originally called for him to commit to nine movies in the role; he agreed to six), and when he finally took the leap, the first thing he did was to check the Web to see what Marvel fans thought of the casting. They thought he needed more muscles, so he got some more, and EW, eager to cater to superhero fans everywhere, publishes a photo of Evans with his naked, hairless chest hanging out; impressive with ponderous pecks and big biceps, he’s being filmed exiting Project Rebirth whereby Steve Rogers gets transformed from skinny kid to muscle-bound super soldier. Retailing Captain America’s origin, the movie takes place in the Marvel fantasy of World War II but plays down the flag-waving jingoism of the 1940s comic book tales because Marvel is leery of irritating one or the other of the nation’s current political polarities. Director Joe Johnson wanted a movie “about international cooperation,” and in this re-telling, Captain America is the leader of a team of elite soldiers from various nations. Said co-producer Stephen Broussard: “It’s not about running from [political interpretations] or being afraid of saying anything, but just staying true to what the story has always been. I welcome whatever kind of healthy debate comes from it,” he added, apparently not aware that “healthy” debate is no longer an aspect of American political life. By the time “Captain America: First Avenger” opens July 22, the next of the six movies Evans will play the role in will be into production—“The Avengers,” studded with stars; besides Evans: Robert Downey Jr. (Iron Man), Samuel L. Jackson (Nick Fury), Scarlett Johansson (Black Widow), Mark Ruffalo (Hulk), Jeremy Renner (Hawkeye), and Chris Hemsworth, who will be reprising his role as Thor in the movie of that name that will open three months before “Captain America.” After which, Evans will have four more turns as Cap: two solos in “Captain America” sequels, and two as part of the gang in subsequent “Avengers” films.

WE’LL BE WAITING NEXT YEAR, TOO The Hallowe’en issue of Parade, the Sunday newspaper magazine supplement, celebrates the holiday with an article by Eric Konigsberg about his initial exposure to the Great Pumpkin when he was eight years old. Linus sped his first letter to the gourd god in 1959, and he’s awaited the sanctified arrival in the pumpkin patch every year since—to no avail. “As I child,” Konigsberg writes, “I felt for Linus, whose faith in something unprovable was stingily rewarded, if at all, with the knowledge that he’d maintained his belief in the face of ever-increasing doubt. ... The true genius,” he goes on, “of the Great Pumpkin may be the way it sends up other holiday parables by having a character seek a deeper meaning in the sole holiday that has no real lesson to teach. Is there any other day we celebrate that is as empty of moral or historical significance?” Then, saying that “the story can be seen as an allegory of the irrationality of belief or as a satire of religion,” Konigsberg quotes Charles Schulz’s biographer, David Michaelis: “On some level, Schulz was showing us how some people would so much rather live with this craziness of false belief instead of just being quiet and resolute in their faith. He was saying, ‘Be careful what you believe.’” Or maybe, Konigsberg says, “Schulz might have actually been paying tributre to the gleeful earnestness of Hallowe’en and of childhood itself.” In referring to Michaelis’ Schulz biography, Konigsberg ratifies the belief of many Peanuts fans (and of the cartoonist’s widow and children) that the book tarnished Schulz’s reputation and memory: “the artist lost a degree of luster in the minds of some Americans ... [because he] was portrayed as gloomy and self-absorbed, jarring traits for the creator of such sweetly memorable lines as ‘Happiness is a warm puppy.’” For Konigsberg, however, it was exactly those aspects of Schulz’s personality “that gave us his delightfully frank, slightly cynical body of work.” As you might expect, I don’t agree. Peanuts was the product of all of Schulz’s personality, not just his dark side; and the prevailing comedy was the result of a world view that was essentially playful and joyous, not gloomy. Incidentally, this issue of Parade is missing altogether the cartoon feature, which, lately, has been staggering between one cartoon a week, usually, and, rarely, the customary two or three.

HINDS

HANGS UP CLEATS That's quite different from the “crazy slapstick” in Hinds’ strip for Sports Illustrated, Buzz Beamer, and from Jeff Millar's satirical writing in Tank McNamara. “Speaking of Tank,” Hinds said, “some people couldn't seem to separate Cleats from Tank. The term Tank Lite came up a few times online, and the Cleats writing was occasionally attributed to the innocent Jeff Millar. In the last couple of years the writing in Cleats has become quirkier as I decided to entertain myself. I can't think of a particular strip that stands out in my mind, but Edith and Dee are my favorite characters. By the way, many of the characters in Cleats are based on real people, including Jack's grandmother Bertha who is based on my wife's grandmother Bertha. The real Bertha is in her late 90s, and is disappointed about losing her celebrity status.” The final Cleats, which we post herewith, as promised, is a sweet humorous melding of what might otherwise be ghoulish Hallowe’en themes and the death of a strip whose creator loved it.

SEARCHING FOR CATHY’S SUCCESSOR As soon as Cathy Guisewite announced her impending retirement—and Cathy’s—the comic strip universe began trembling as a scramble commenced among survivors to fill the vacant slot in over 700 newspapers—a virtual windfall of opportunity not experienced since The Far Side ceased on January 1, 1996, a day after Calvin and Hobbes retired. At Editor & Publisher (October’s issue), cartoonist-reporter Rob Tornoe summarized the contest by reviewing the availability of comic strips about women by women, assuming that newspaper editors, known to be a somewhat knee-jerk lot when it comes to their comics sections, would be looking for an exact replacement for the profession’s iconic strip about female issues by a female. Judging from his article, Tornoe sees only four “female-centered” strips that might meet the knee-jerk criteria; and here they are: Rina Piccolo’s Tina’s Groove (launched in 2002), about “a single, smart, attractive waitress ... Shrewdly self-aware, Tina refutes cliched notions of single women as neurotics obsessed with career or [getting married].” Sandra Bell-Lundy’s Between Friends (1994) “celebrates the essence and angst [lovely phrasing—RCH] of three contemporary women friends in their forties ... [who deliberate] about office politics and body image and snicker about their ex-husbands’ girlfriends.” Jan Eliot’s Stone Soup (1995) is about “an extended family living in two households. ... Women may be the central characters of the strip, but its kindness toward men and a wide array of children characters [of different ages]... create a big tent for comics readers of all ages.” And Terri Libenson’s The Pajama Diaries (the newest of the crop; started in about 2006), which appears as illustrated pages of Jill Kaplan’s diary, wherein she records her efforts to “juggle her work [she works at home as a graphic designer], family [husband and two children], and sex life—or lack thereof—without going bonkers.” These are all excellent strips—well-drawn realistic comedy on every hand—and no newspaper editor can go wrong in resorting to one of them to replace Cathy. An obvious candidate, Lynn Johnston’s For Better or For Worse, is probably not eligible: chances are it already appears in most of the papers looking for the next Cathy. Hilary B. Price’s Rhymes with Orange, although by a woman, doesn’t concentrate on women’s issues enough to measure up. Nicole Hollander’s Sylvia is probably too satirically edgy to compete in the same competition. Besides, Sylvia is an “older woman.” But there are two other well-drawn strips with strong young female characters facing contemporary women’s issues in life and, in one, careers. They are both, however, disadvantaged in this age of tit-for-tat so-called thinking because each of them is written and drawn by a male cartoonist. In the alleged minds of too many newspaper editors, Guisewite’s Cathy cannot—heaven forfend!—be replaced by a strip produced by a male sensibility. Too bad: these two are at least a match for any of the others Tornoe mentions—and often regularly surpass them in sensitive humor in arenas of human endeavor that all of us care about. Brooke McEldowney’s 9 Chickweed Lane focuses on the lives and aspirations of three women at that address: the daughter, her mother and her grandmother. The daughter has graduated from high school and is on her own in New York, working in a ballet company, and living with her dancing partner, a gay man; she has entered a romantic relationship with her highschool chum, and a year or so ago, they both lost their virginity in a beautifully comedic but sensitive sequence that lasted weeks. The grandmother has been telling the story of her World War II experiences as a USO entertainer, falling in love with two men (an American and a German), another empathetic and mature narrative that lasted more than ten months—an unheard of achievement with today’s short-attention-span audience. But it was done superbly— suspensefully, tastefully, wonderfully. The mother, a college professor, married a colleague a couple years ago, and their passionate relationship provides an occasional interlude. In my view, 9 Chickweed Lane is one of the two or three very best newspaper comic strips now running (one of the others is Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury)—mature, realistic storylines with gentle humor, beautifully drawn. Greg Evans’ Luann, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary, is another of the very best comic strips around. The eponymous Luann, a teenager, faces the usual array of problems (dating, grades) encountered by highschoolers, and she is surrounded by a collection of friends that keep the incidents interesting and engaging and realistic. But it is the romance between her nerdish older brother Brad and his beautiful paramour Toni Daytona that best demonstrates Evans’ gift for witty dialogue and humane dilemmas. Too bad McEldowney and Evans are men. Some newspapers, Tornoe speculates, will not look for a square peg to fit in the rectangular hole Cathy leaves behind. Quoting Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com, Tornoe agrees that some editors “will use this departure to run a near endless stream of comic strip trials, which they can usually run for free until they find a permanent replacement.” Well, maybe. At first, I guessed that the strips by Rina Piccolo, Sandra Bell-Lundy, Jan Eliot and Terri Libenson will be recruited pretty fast. But Gardner found out differently by doing some research. Gardner gathered and analyzed information from several sources to try to find out which strips most benefitted from Guisewite's retirement. First, he consulted the syndicates themselves, asking them to name which three of their strips were selling the best. Here are the results (strips with a * indicate a feature launched this year): Creators: *Dogs of C-Kennel, *Diamond Lil, Free Range; King Features: *Dustin, Zits, Rhymes With Orange; United Media: Pearls Before Swine, *Freshly Squeezed, Big Nate; Universal Uclick: Stone Soup, Cul de Sac, *ThataBaby!; Washington Post Writers Group: Pickles. Only one of Tornoe’s list made it—Stone Soup. But Gardner wasn’t content to let the question dangle solely on the testimony of self-interested syndicates. He also watched Google News for announcements from newspapers about which strips they were putting in Cathy’s place, and he assembled some additional stats from syndicates. He determined that all three sets of data pointed at these three strips as the top contending Cathy replacements: Dustin by Steve Kelly and Jeff Parker; Stone Soup by Jan Eliot; and Pickles by Brian Crane. Gardner cautioned that newspapers do not necessarily replace one strip with another of the same sort. But some do. “For those editors looking for a strong female character, Stone Soup was the go-to strip,” he reports. “Out of curiosity, I added up all the female character strips in the Google News dataset and compared their sales to the total. Papers purchased less than 10% female lead character strips. I wish I had better data regarding how well female strips did. I doubt that the 10% is accurate; it just seems too low, but from anecdotal conversations while at the Festival of Cartoon Art, I have no reason to believe that female strips as a whole did very well compared to all sales.”

STAN LEE GIVES ACTING ADVICE Rick Marshall at MTV News asked Stan Lee what advice the co-creator of Spider-Man might have for actor Andrew Garfield, lately chosen to play the part in the next Web-slinger movie. Said Lee: "The best way to bring Spider-Man to the screen is to make it seem very natural—just to be a very simple, everyday, ordinary kid who happens to be good at science and wishes he were more than he is. He wishes he were more popular with the guys. He wishes the girls would pay a little more attention to him. He wishes he could make more money because he worries about his aunt who has to pay the rent, and it's kind of tough for her. He doesn't want her to lose her house." According to Lee, Marshall said, “the essence of playing a believable Peter Parker is not so much in the super-powers and snappy comebacks, but in finding your inner, awkward teen.” Lee

continued: “He should have the kind of concerns that so many teenagers have.

The thing about Spider-Man, one of the things that makes him so popular, is the

fact that you can relate to him. He's not that different from the average guy,

except he's able to crawl on walls and swing on webs." Lee laughed.

COMICS IN PORTLAND—A GAUGE OF INDUSTRY HEALTH? Erik Henriksen at blogtown.portlandmercury.com, realizing that the comic book industry is “in a state of flux” trying to integrate itself into a digital universe without being quite ready to abandon olde timey print, thinks “what will happen in local comics shops across the country in the next few years will affect any number of things—from the existence of tiny nerdy supply stores in small towns to the omnipresent power of kajillion-dollar superhero blockbusters.” Because Portland, Oregon is “a city that's home to a huge array of comics creators, the Stumptown Comics Festival, publishers like Dark Horse Comics, Oni Press, and Top Shelf Productions, and some of the best comics shops in the world,” Henriksen thought its comics shops might supply insights into the future, so he e-mailed some of their owners and employees and asked them what they thought about the future of the medium and of their business. He was surprised to learn that most of those he talked to “kinda like” digital comics. “They like 'em because they feel digital comics will bring new readers to brick-and-mortar shops,” he said. And then he quoted some of his sources. "Digital comics are here to stay, but it's not going to be a big deal. Just like VHS/Betamax/DVDs/Netflix didn't kill the movie theater, nor will digital comics kill the comic shops," says Michael Ring of Bridge City Comics. "The people that come in looking for comics want to read comics. They want to hold them in their hands and be able to loan them out and pass them down to their kids. Digital comics are great as a low-cost way to sample new series." From a creator's perspective, Steve Lieber sees huge potential for getting the work of comics professionals in front of more readers. "As a freelancer, I don't have access to the numbers that would make it possible to talk about the effects [of digital sales] on brick-and-mortar retailers—but to be honest, I don't think the publishers know either," Lieber says. But that doesn't stand in the way of his enthusiasm. "I'm incredibly eager to see the digital market grow," he says. "There aren't nearly enough brick-and-mortar stores in the US to serve all the people who would like to read comics. Making it easier to get comics is the single best way to expand our readership." Henriksen also got an earful on another hot topic—the cover price of funnybooks. Said Lieber: "Shop-owners I've spoken to have told me that the $3.99 price point was chasing away a number of once-steady customers.” Unsurprisingly, Marvel and DC's recent announcements that they plan to ease up on charging $3.99 per issue have been welcomed by both readers and retailers. Henriksen continued: “With the pricing and the format of comics in motion—and with both of those factors affecting small, local shops—I asked Portland's comics shop owners about the state of the direct market in general. Unlike their responses to digital comics and pricing, their answers were more varied.” "We'd love to see the industry loosen [Diamond Comic Distributors'] virtual monopoly on distribution," say shop operators Allie and Jeremy Tiedeman. "While [Diamond has] a lot of good qualities, it's discouraging to see their monthly catalog brimming with superhero and genre comics but short on a lot of awesome indie stuff. We'd love to see a more well-rounded distribution, whether via Diamond or some other company. We think comics will continue to spread throughout the culture, especially via indie and literary comics and graphic novels. We hope to see the self-publishing market in Portland continue to grow and flourish." At Excalibur, Rosko (whose first—or last?—name I’ve irresponsibly lost; sorry) sees a general increase in comics reading, in part thanks to how successful superhero films have been in recent years. That interest, he says, will keep comics shops around. "Every time an ‘insider' says the industry is going to take a crap, it comes back in a big way. I've been hearing ‘It's all over in five years' for the last 15, and I'm sure they've been saying that longer than that," he says. "That's what makes comics so interesting an industry—it changes and adapts and always finds a way to survive. We've also been noticing kids are coming in, looking to explore comics at an exponential rate. Kids have been devouring the books we give them. They see the characters on TV or in movies, and they want more adventures with their favorite characters. Luckily in some cases there are 40, 50, 70 years' [worth] of material they can read! We also have adults feeling the same way. Comic book characters and storytelling has permeated the popular culture—people more and more are now interested in reading comics."

HOMER’S RELIGION Just as we were approaching that infamous religious holiday, All Hallows Eve (or, as it’s sometimes known, Hallowe’en), came the news that Homer Simpson and the rest of his jaundiced brood are good Catholics, viable candidates, we’d suppose, for celebrating All Hallows Day on November 1. This news arrived through one of the world’s last remaining infallible sources, L’Osservatore Romano, the official newspaper of the Vatican, and if it doesn’t know about Catholicism, who does? In an essay in the paper published October 17 (just as the Festival of Cartoon Art was concluding at the Ohio State University in Columbus), Luca M. Possati supported his contention about the Simpsons by citing a Jesuit priest's study of the 2005 episode, "The Father, the Son and the Holy Guest Star," in which Bart attends a Catholic school and Homer tries out the practice of confession. But Al Jean, an executive producer and show runner of "The Simpsons," disagrees. Quoted at Entertainment Weekly’s website, EW.com, he said the Simpson family attends the First Church of Springfield, which is "Presbylutheran," adding: "We've pretty clearly shown that Homer is not Catholic. I really don't think he could go without eating meat on Fridays—for even an hour." “Catholicism isn't the only religion with a soft spot for Homer and his family,” said David Itzkoff in the New York Times artsbeat.blog: “The Homer Calendar website uses Simpsons characters to illustrate the traditions of Passover and includes many links to discussions about the Jewish content on the show.” Matt Groening, who was a featured speaker at the OSU Festival (a triennial event sponsored by the Billy Ireland Library and Museum of Cartoon Art), was not, I assume, available for comment, but in the Playboy Interview of June 2007, agreed with his interviewer who said “The Simpsons” regularly make fun of religion. Groening remembered an episode during which Homer is chased by a mob, “and Homer runs away, yelling, ‘Save me, Jebus!’ He can’t remember the guy’s name. We also did a parody of a commercial about the new Catholic Church that was shot like a beer commercial.” Scarcely a deferential Catholic attitude, I’d say. But the question was rendered moot a couple of days after Reuters broke the story. BusinessWorldOnline reported that the author of the cited study claimed the Vatican newspaper had misinterpreted his work. "I wouldn't say they're Catholic,”said Francesco Occhetta, a Jesuit priest and staff writer for the Rome-based journal Civilta Cattolica. “I would say they're people of faith." Occhetta, who is also writing a doctoral thesis in moral theology at the Vatican university, said he is an avid viewer of the popular series and can see important spiritual life lessons in the adventures of the Simpson family. Said he: “I would say that the Simpsons are open on the question of God. The authors are fiercely critical of some religious people but they respect faith, openness to God, prayer and going every Sunday to listen to their pastor—even if they sleep or eat popcorn when they go," he added. "There's this idea that faith unites the Simpsons," he continued. "It's not like Walt Disney. They're not just good people or bad people. The characters have both good and evil traits. Just like real life.” And there you have it: a Jesuit priest affirms the reality of the Simpson family.

LYND WARD PRIZE ANNOUNCED In a press release early in October, Penn State University Libraries and the Pennsylvania Center for the Book announced the creation of the Lynd Ward Prize for Graphic Novel of the Year. “The Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize honors Ward’s seminal influence in the development of the graphic novel and celebrates the gift of an extensive collection of Ward’s wood engravings, original book illustrations and other graphic art donated to Penn State University Libraries by his daughters, Robin Ward Savage and Nanda Weedon Ward. Between 1929 and 1937 Ward published his six ground-breaking wordless novels—Gods’ Man, Madman’s Drum, Wild Pilgrimage, Prelude to a Million Years, Song without Words and Vertigo,” all of which have been re-issued lately by The Library of America in a two-volume boxed set entitled Lynd Ward: Six Novels in Woodcuts, “the first time the nonprofit publisher has included a graphic novelist in its award-winning series.” The Lynd Ward Prize will be presented annually to the best graphic novel, fiction or non-fiction, published in the previous calendar year in the United States by a living American citizen or resident. The announcement of the award will take place each spring, and the prize of $2,500, the two-volume set of Ward’s novels, and a suitable commemorative will be presented each fall to the winner at a ceremony to be held at Penn State.

JUST HOW HIP IS SUPERMAN THIS TIME? The razzle-dazzle foofaraw began on Monday, October 25, saith Glen Weldon at National Public Radio, with an article in the New York Post, which “touched off a mainstream media firestorm. Outlet after outlet took the bait; many seized the opportunity to make with the hacky hipster jokes, viz: ‘Will the Fortress of Solitude be a Williamsburg Food Co-op?’ Blah blah blah hoodie blah low-cut jeans blah moody blah blah Twilight blah. Good heavens! Will Superman ever be the same? Short answer: Yes.” What got Weldon’s wattles in an uproar is all the publicity suddenly converging on the hardcover graphic novel Superman: Earth One when it hit stores nationwide at the end of October. You have to look twice to comprehend that the character on the cover is Superman/Clark Kent. “The big ‘S’ is still on his chest,” reported the Associated Press, “but the new Superman is not exactly the chipper and bright-eyed optimist of lore.” Probably the AP hasn’t been reading comic books lately; Superman stopped being bright-eyed and chipper even before he married Lois Lane. But AP, undeterred, goes on: “The kid from Kryton [in this book] sports a hoodie, a brooding brow and fashion sense that wouldn’t put him out of place in hipster lairs.” The AP quotes DC Comics co-publisher Dan DiDio: “We always knew that we wanted to do a real, contemporary interpretation of Superman. He's young, he's hip, he's moody. He really fits in with the types of stories people are looking for today," DiDo concluded, interviewed by USA Today, which, in turn, finished: “With writer J. Michael Straczynski at the helm and Shane Davis doing the art, it should be interesting to see where our hero goes.” A super slacker? Weldon rampages on to point out that it’s all happened before: “This is only the latest iteration of the most-told tale in comics—that of Superman's origin. It's a story that exists in a continual state of reinterpolation: in 2009's Superman: Secret Origin, Geoff Johns and Gary Frank retold it in six issues; in 2005's magnificent All-Star Superman, Grant Morrisson and Frank Quitely managed to bust it out in just 4 panels and 8 words: ‘Doomed planet. Desperate scientists. Last hope. Kindly couple.’” The ritual re-telling, like all folk tales, has “been going on for decades, and every time, the cultural touchstones of Clark's youth edge closer and closer to the present day. Over the years, phone booths made way for smart phones. ‘Dese-and-dose’ gangsters morphed gradually into technological terrorists.” The current excitement, in other words, is simply another “variation of the oft-written ‘They're Making a Change to That Thing You Dimly Remember From Childhood Shock Horror!’ story that the media has seized upon since Lincoln Logs went plastic.” Well, yes, Clark Kent in a hoodie is just another in a long and increasingly boring series of make-overs that the Man of Steel has endured over the last forty years. It’s boring to long-time fans because we’ve seen it all before: we know the origin of Superman. And whatever the new take on it, it’s usually a matter of infinitesimal tweaks rather than major overhauls. But this time, I wonder. Looking through the last several issues of Diamond’s Previews catalogue, it’s clear that Batman titles outnumber Superman titles. Perhaps this hardcover re-do of the iconic DC character is a corporate effort to reclaim the company brand from under the grim glint of the Bat signal. The eruption of media attention, after all, was doubtless sparked by publicity releases from DC; the fuss Weldon decries was scarcely a spontaneous generation of interest. Maybe the Powers That Be (the earth-bound, corporate suits, that is—not the caped and spandexed kind) want to restore the company’s patriotic patina by unseating the psychotic Dark Knight and putting the cleaner-cut Superman back on the throne. Maybe. But then again, the hoodie Clark Kent has about him something of the psychotic aura ...

CARTOONS IN AMERICAN HERITAGE The current issue of American Heritage (Fall 2010) uses cartoons as well as photographs to illustrate virtually ever article—origin of the Korean War, capture of Jeff Davis after the Civil War, Congress vs. the President. Editor Edwin S. Grosvenor explains: “Time and again, political satirists and propaganda artists got right to the core of issues we were going to bring alive. Political cartoonists sharpened their editorial knives way back to the earliest days of the Republic, as you’ll see.” Among the cartoons are several embellishing Nat Gertler’s essay on the 60th anniversary of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. No profound insights herein; just a nicely abbreviated biography of the cartoonist and a short history of the strip and descriptions of the main characters (with only one typo: editorial cartoonist Steve Kelley, whose cartoon on the day after Schulz’s death ends the article, spells his last name with two e’s). But the notable part of the article is the preface by Schulz’s daughter, Amy Schulz Johnson, who writes: “My father signed with United Feature syndicate believing that his job was to help editors sell newspapers. He started in seven papers. Fifty years later, with the strip appearing in a record 2,600 newspapers, Dad still went to work motivated by that same belief. As I grew up, I regarded my father not as Snoopy’s dad but mine. I wasn’t quite convinced he had a real job like other dads: he didn’t go off to work like other dads but worked in a studio on our property in Santa Rosa, California. He never worked past 5 p.m. nor on weekends. His children would think nothing of walking into the studio, right past the secretary, and into his office. I can picture him looking up and immediately putting down his pen to talk to me. He never once asked me to wait while he finished a drawing or some lettering. Whenever my brothers asked him to play baseball—even in the middle of the day—he happily complied. As much as he loved the strip, he loved his children even more. “Life gives birth to pure art, and a true artist pays attention to the details around him—not just the details in his life but in all life. My dad’s gift for observation was proven by the fact that hundreds of millions of people throughout the world would wake up every morning and turn the newspaper page to his strip—nearly 18,000 strips in all—because they had grown to love the characters as real people.” I don’t remember reading any passage like this in David Michaelis’s biography of Schulz.

THE CHARLES SCHULZ FAMILY is launching a few new Peanuts projects. The initial idea after Spark’s death was that the strip would go into perpetual rerun and everything else would stay the same except for contriving new merchandise. But a new animated film is set for release next spring, the Associated Press reports, called “Happiness is a Warm Blanket, Charlie Brown.” And a new “social media game” has begun on Facebook and Twitter and at a popular gaming website for children. Meanwhile, ABC has signed on for five more years of airing Charlie Brown holiday specials.

MORE ANNIVERSARIES GALORE Celebrating

its 40th anniversary right alongside the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide is Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian. Roy Thomas, one-time editor-in-chief

and longtime Conan scribe, remembers discussing the possibility of adapting

Conan at Marvel: "Stan Lee had no feel for what sword and sorcery

was, but I had bought (though I hadn't read them) all the Conan paperbacks that

had come out to date, largely because of the Frazetta covers."Thomas told

Diamond’s Scoop that he wrote a memo to Marvel publisher Martin

Goodman saying that a sword and sorcery comic would contain some of the

same qualities super-hero comics did—a strong hero, beautiful women, monsters,

and villainous sorcerers. Conan No. 1 sold well, but each of the next half dozen issues dropped in sales.

Thomas recalled Lee stepping in around the eighth issue. "Stan 'suggested'

that we have more humanoid foes for Conan on the covers than giant spiders,

man-headed snakes, apes in armor, and women turning into tigers. With Nos. 8-9

and afterward, the sales [consequently] picked up, and afterwards Conan was

never in danger of cancellation for another 25 or so years." ***** Remember when comedians were leery of making jokes about Baracko Bama (probably because he’s black)? That’s changed. The Associated Press reports that through Labor Day this year, late-night comics Jay Leno, David Letterman, Jon Stewart and Jimmy Fallon joked about O’Bama 309 times. That makes him a laughing stock. Sarah Livingston Palin, with only 137 jokes, was runner-up. You wonder who (or what entity) in these troublesome times bothers to keep such scores. It’s the Center for Media and Public Affairs.

THE RANKS OF PINK At DailyCartoonist.com,

Alan Gardner reported that several King Features comics participated in a

“Cartoonists Care” initiative on Sunday, October 10 (10-10-10, kimo sabe!). In

support of National Breast Cancer Awareness Month, more than 50 of the King

Features strips “turned pink” and a special Dan Piraro Bizarro signature art piece was auctioned off. Each comic strip featured the

internationally recognized pink ribbon for breast cancer awareness, emblazoned

with the tagline “Cartoonists Care.” The pink strips ran in newspapers across

the country and online; you doubtless saw some of them in the Sunday funnies of

your local newspaper on October 10. But you probably didn’t see Piraro’s

special artwork for the campaign. So here it is. “It’s very inspiring to see so many of our cartoonists come together to rally around such an important cause,” said Brendan Burford, comics editor at King Features Syndicate. “Nearly everyone has a connection to this heart-wrenching disease, and we felt it was important to make a powerful statement to help support for Breast Cancer Awareness Month. We could think of no better way to do that than by turning the funny pages pink! We hope the ‘Cartoonists Care’ initiative will help raise awareness and encourage our millions of readers across the country to do whatever they can in the fight against breast cancer.” This is not the first time syndicated cartoonists have come together to help publicize an important cause, Gardner noted. In November 2001, the entire National Cartoonists Society cartooning community participated in Thanks&Giving, in which special cartoons, created for Thanksgiving Day, were auctioned and the proceeds donated to the September 11th Fund, established by The New York Community Trust and United Way of New York City. In April 2008, 45 King Features cartoonists created Earth Day-themed comics to raise awareness for the environment and health of the planet. But the first such effort materialized on Thanksgiving Day 1985. Garry Trudeau, Milton Caniff and Charles Schulz mustered over 175 of their colleagues, each of whom produced for the holiday their usual strip but featured food or being hungry in order to promote reader consciousness of worldwide hunger. Later, all the strips were published in a booklet entitled Comic Relief, the sale of which raised money for Africa’s hungry and homeless. This year’s “Cartoonists Care” participating comic strips include:

Apartment 3-G by Frank Bolle and Margaret Shulock Arctic Circle by Alex Hallatt Baby Blues by Jerry Scott and Rick Kirkman Barney Google & Snuffy Smith by John Rose Beetle Bailey by Mort and Greg Walker The Better Half by Randy Glasbergen Between Friends by Sandra Bell Lundy Bizarro by Dan Piraro Blondie by Dean Young and art by John Marshall The Brilliant Mind Edison Lee by John Hambrock Buckles by David Gilbert Crankshaft by Tom Batiuk and Chuck Ayers Crock by Bill Rechin Curtis by Ray Billingsley DeFlocked by Jeff Corriveau Dennis the Menace by Marcus Hamilton Dustin by Steve Kelley and Jeff Parker Edge City by Terry and Patty LaBan Family Circus by Bil Keane and Jeff Keane Flash Gordon by Jim Keefe Funky Winkerbean by Tom Batiuk Grin & Bear It by Fred Wagner and Ralph Dunagin H”agar the Horrible by Chris Browne Heaven’s Love Thrift Shop by Kevin Frank Hi & Lois by Brian Walker, Greg Walker and Chance Browne Judge Parker by Woody Wilson and Mike Manly The Lockhorns by Bunny Hoest & John Reiner Mallard Fillmore by Bruce Tinsley Mark Trail by Jack Elrod Marvin by Tom Armstrong Mary Worth by Karen Moy and Joe Giella Moose & Molly by Bob Weber Sr. Mother Goose & Grimm by Mike Peters Mutts by Patrick McDonnell My Cage by Ed Power and Melissa DeJesus Ollie & Quentin by Piers Baker Oh, Brother! by Bob Weber, Jr. and Jay Stephens On the Fastrack by Bill Holbrook The Lockhorns by Bunny Hoest and John Reiner The Pajama Diaries by Terri Libenson Pardon My Planet by Vic Lee The Phantom by Tony DePaul and Paul Ryan Popeye by Hy Eisman Pros & Cons by Kieran Meehan Retail by Norm Feuti Rex Morgan M.D. by Woody Wilson and Graham Nolan Rhymes With Orange by Hilary Price Sally Forth by Francesco Marciuliano and Craig MacIntosh Sherman’s Lagoon by Jim Toomey Shoe by Chris Cassatt, Gary Brookins and Susie MacNelly Six Chix (There are six different female cartoonists on this comic, one for each day of the week, but the artwork for Breast Cancer Awareness Month was created by Anne Gibbons) Slylock Fox by Bob Weber Jr. Tina’s Groove by Rina Piccolo Todd the Dinosaur by Patrick Roberts Zippy the Pinhead by Bill Griffith Zits by Jim Borgman and Jerry Scott

MORE EXCITATION AT PLAYBOY I watched the documentary “Hugh Hefner: Playboy, Activist, and Rebel” last month, hoping I’d be able to contradict Michael O’Sullivan at the Washington Post, who said the film left him with an impression of Hefner that “seems less a playboy, activist or rebel than a dirty old man.” The movie, by Brigitte Berman, is highly sympathetic to Hef’s view of himself as not only the founder of an “iconic skin mag, but as a tireless champion of gay and civil rights, free speech and liberty, and as a ferocious opponent of censorship, violence, war, and religious persecution. ... Yes,” O’Sullivan goes on, “he opened—or, rather, kicked down—more than a few doors” and he hardly seems the threat to American social order than his critics, a few of whom appear among the supportive talking heads, want us to believe he is. But Hefner, perpetually attired in his pajamas with a bevy of blonde bimbos less than half his age always awaiting him in his bedroom, seems more satyr than savior. And most of his crusades—for freedom of speech and press and sex, homosexual as well as heterosexual, and feminism and the rest—all serve to support the continued publication of Playboy. These activities of the activist publisher are therefore scarcely unencumbered altruism. He’s not Tom Paine or Mohandas Gandhi. But who of us is? I applaud Hefner’s efforts in keeping the press and speech free, in promoting the feminist causes, and in raising the visibility of African American performers and pin-ups, but why must he persist in perpetuating a persona as an ever-ready stud? He’s 84. It’s time to rest. Most males that age do. But Hef takes Viagra and goes on pumping away as if he were twenty again and working on a mink farm. That’s okay if it gives him pleasure; but why does he feel his public image requires such constant burnishing? Dick Cavett, one of those interviewed, summed up the happiest interpretation of this circumstance, drawling (long pauses between words) that Hef provides “wonderful hope ... to ... men ... over 100.” I was glad, though, to hear Hefner defend his magazine against the threadbare charge of objectifying women. “Of course, they’re sex objects,” Hef snorted. “If they weren’t, the species would die off in a generation.” And men to women are sex objects, too. Female lust is inspired by different parts of the male anatomy—the butt rather than the boobs, say, hirsuteness rather than naked flesh—but neither gender is immune from the charge that is so often leveled at Playboy alone. By the way (although not at all incidentally), the current (November) issue of Playboy has a total of 14 cartoons—5 full-pagers and 9 smaller, plus the “pin-up cartoon” of Olivia and two strips, each a half page (Dirty Duck) or less (Meaty Myths). In May and July, the last two issues I did a count in, the total was 12 (4 full-pagers and 8 smaller), so this issue may represent an improvement, however slight. The page-count is higher—138 vs. 126/130; and the ratio of cartoons to pages is better this time: 1/27 for full-pagers vs. 1/32 in May and July (that is, one full-page cartoon for every 27 pages in November); 1/15 for smaller cartoons vs. 1/16 in May and July.

***** Apropos by reason of both preoccupation and vicinity—Bob Guccione, founder of Penthouse magazine, died October 20 at 79 in Plano, Texas, after a long struggle with cancer. Following a failed teen marriage, Brooklyn-born Guccione drifted around Europe and North Africa, “sketching café patrons” until, settling in London, he decided in 1965 at the age of 35 to challenge Playboy. While Playboy had spawned a host of copy-cats, most were cheap imitations, but Penthouse easily matched its inspiration in gloss and literate (albeit somewhat more lascivious) content. Guccione modified his mockery in a significant way, noted Time: the Penthouse models were not “the girl next door” of Playboy fixation; instead, they were decidedly “naughty, looking away from the camera to emphasize the magazine’s ‘voyeurism.’” Penthouse was the most successful of the Playboy entourage, and upon this foundation, Guccione built a pornographic empire, General Media, Inc., which, by 1982, yielded him a net worth of $400 million. But in later years, he lost most of his fortune through bad investments and risky ventures. General Media filed for bankruptcy in 2003, and creditors descended on Guccione’s lavish Manhattan townhouse, auctioning off its furnishings. The one-time porn mogul spent his last years on a much less extravagant scale of living.

FUTURE EVENTS CAST SHADOWS BEFORE I attended the 10th triennial (once every three years, aristotle) Festival of Cartoon Art staged by the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum (once, back in the yawn of time, dubbed the Milton Caniff Research Room because when he donated his papers and original art to his alma mater that collection was the foundation of the present edifice) October 15-16. I’ll have a report next time. But I’ll mention now that one of the presenters at the comics confabulation was one-time DC president, Paul Levitz, who said he’d been signed on by Taschen to supply text for the illustrations the publisher had assembled for the gigantic 75 Years of DC Comics tome; and he supplied 300,000 words for 20,000 illustrations, he said. He also said Taschen is printing 250,000 of the book, a whopping number—probably anticipating huge sales in Europe, where Taschen hangs its hat. Yes, I know: I promised a review of NBM books this time, coupled to a short history of the publisher. But I’ve been overwhelmed, as you can plainly tell; so, next time. Next time, too, some of the cartoons Ted Rall and Matt Bors did about their Afghan jaunt, and a few of their comments. AND—a report on the annual so-called “Cartoon Issue” of The New Yorker. And more, much more (as usual). Before Christmas, I’ll tell you about my visit in early October to the Fred Harman Museum in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, where the creator of Red Ryder and Little Beaver returned to oil painting to finish his career.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES & MOTS “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Live the life you have imagined.”—Henry David Thoreau "Life is not a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in one pretty and well-preserved piece, but to skid across the line broadside, thoroughly used up, shouting 'Geronimo!'"—Hunter S. Thompson “Linguists have discovered a new language spoken by a remote tribe in India that’s understood by only 1,000 people. I believe the language is called ‘tech support.’”---Jay Leno

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted CENSORSHIP OR EDITING: CALL IT WHAT YOU WILL Two cartoons published in September in the Daily Campus, student newspaper at the University of Connecticut, touched off an outcry on campus. Victory Lap by Zack Wussow carried the message, "Forget sugar and spice and everything nice. Try crabs, scabs and everything viral. That's what girls are really made of." The other comic, Milksteak and Jellybeans by Alex Dellin, showed a male tossing a diamond ring into a bedroom, while a girl, tongue hanging out, chases after it. The cartoon, reported ctnow.com, implied that the diamond ring—or maybe the promise of marriage—had persuaded the girl to have sex. Nellie Stagg, a student, wrote in her letter to the paper: "Your writers' flagrant disrespect of women and approval of the rape culture that we live in has given me reasonable belief to discredit your entire operation." Miranda DePoi, a junior who is a teaching assistant with the Violence Against Women Prevention Program, said of the cartoons: "They weren't witty, they weren't clever. It was a complete and total disrespect of my gender. … I thought the image of the girl running into the bedroom with her tongue hanging out was very degrading." Cartoonist Dellin, a senior, said he was sorry if people were offended by the Milksteak and Jellybeans episode, but he thinks the connection that some have made between his cartoon and sexual assault is farfetched. "It was a play on an old cliché," said Dellin. "There's a sleazy guy trying to get laid, a girl he's trying to dupe, if you will. … The whole point was: this doesn't work. Obviously, this doesn't work. At some point, it's kind of ridiculous that I can't make a little ring joke in the commentary section." I dunno: an eager-looking girl with her tongue hanging out doesn’t look like Dellin was trying to say the ring on the bed “doesn’t work.” Wussow, the creator of Victory Lap, submitted a statement to the Daily Campus that "what was meant as an absurd exaggeration appeared to many as a literal statement. Most of the time, people seem to get what I'm saying. This time, it really missed the mark." That’s the trouble with irony and satire, Wuss: it often looks like a literal statement. The Daily Campus editor, John Kennedy, said his staff will be working on a "stronger policy" regarding what is allowed into print, and staff will attend workshop on violence against women.

ELSEWHERE,

the Eastern Echo, the campus newspaper at Eastern Michigan University,

had the inordinate temerity to publish the cartoon we’ve posted in this

vicinity, and, according to Melissa Lutomski of the Echo, people at the

University and, I assume, in town got their shorts all bunched up over it

enough to prompt serious responses from the University administration and the

paper’s editors. Said the editors: "We understand the cartoon may have offended some readers. We apologize for the lack of sensitivity some felt we showed for publishing the cartoonist's work. The cartoon points out the hypocrisy of hate-filled people. Its intent was to ask how can someone show affection for one person while at the same time hating someone else enough to commit such a heinous act as hanging.” The cartoon reeked of irony, but irony, as we’ve seen in Connecticut, is tough for some people to process. Apparently, lots didn’t process it here. The editors continued: “We wish to remind readers that they are free to express their opinion on our discussion boards and we hope to continue to foster free thought and open discussion on campus and in the community." EMU’s management chimed in with support for a student free press (doubling as CYA for the administration): "The students are responsible for writing and editing the entire newspaper. The University does not exercise any editorial control over the content of the newspaper. The University does not condone or support any actions that are racially offensive or insensitive." Most of the comments I read online at wxyz.com supported the paper.

NEWSPAPER EDITORS, whether on college campuses or elsewhere, run the risk of raising reader ire every time they publish an editorial cartoon. Editorial cartoonists express points of view—vividly and often simplistically (that’s what cartoons are supposed to do; and they’re good at it)—and some readers might not agree with the point of view (or the simplicity of the imagery). They might, as a consequence, phone the paper’s editor to complain about the cartoon, consuming valuable time that the editor would otherwise be devoting to the latest escapades of Paris Hilton or to the marble-mouthed bromides of John Boehner. And editors don’t like anyone to impose upon the way they choose to spend their editor energies. So sometimes, rather than risk the aforementioned ire, editors just spike a cartoon they think might offend enough readers to take them away from Important Stuff. Here’s

one that Rob Rogers did last year. His editor at the Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette spiked it, but it avoided crucifixion by escaping through the

syndicate pipeline. Others

of Rogers confreres aren’t usually that lucky when they get one of their

favorites spiked. In its September issue, Editor & Publisher ran a

gallery of half-a-dozen editoons “deemed by editors to be too ‘hot’ to run.”

Here they are, and attached to them are the cartoonists’ explanations for the

short lives of their creations. The subject of spiked editorial cartoons is given book-length treatment by David Wallis in Killed Cartoons: Casualties from the War on Free Expression, a 2007 paperback (290 6x8-inch pages; Norton, $15.95) that examines scores of cartoons that never made it into print in their newspapers; most of them are of fairly recent vintage. Fascinating reading.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution If you pay any attention to the tv news reports about NPR’s firing of analyst Juan Williams, you’d think he was fired for saying something inappropriate about Muslims. According to Matea Gold of the Chicago Tribune, here’s what Williams said in a discussion with Bill O’Reilly: “I mean—look, Bill, I’m not a bigot. ... But when I get on a plane, I got to tell you, if I see people who are in Muslim garb and I think, you know, they’re identifying themselves fist and foremost as Muslims, I get worried. I get nervous.” He also immediately noted that it was not fair to see all Muslims as extremists. No matter. These days, you don’t want to say anything inappropriate about Muslims because a radical few of them, suffering from too tender sensibilities, go all bloodthirsty when you do. So NPR, anxious not to have its blood spilt, severed its connection with Williams. But that wasn’t the Real Reason Williams was fired. The Real Reason was that Williams’ remarks “were inconsistent with NPR’s editorial standards and practices and undermined his credibility as a news analyst with NPR,” according to an official statement from the network. And what are those standards and practices? In the initial reports, no one (except Matea Gold) cited them. I watched an analytical discussion of the matter on PBS’s “NewsHour” the other night, and none of the “experts” said what those practices might be. Not even a sister operation in the media defended NPR. One could well go away supposing that it was the Muslim name-calling that got Williams canned. But not according to Gold. Gold quotes Dana Davis Rehm, NPR’s senior vice president for communication, who said Williams’ comments “violated internal ethics policies that prohibit NPR journalists from going on other media and expressing ‘views they would not air in their role as an NPR journalist.’ The guidelines also prohibit NPR journalists from participating in programs ‘that encourage punditry and speculation rather than fact-based analysis.’” So Williams was actually fired because he expressed opinions—any opinion, liberal or conservative—that would get him fired had he expressed them on NPR. But Williams has been under contract at Fox as well as NPR for some time, years maybe. How come NPR didn’t have any second thoughts about that arrangement? Did management there actually believe that Williams could go on Fox, a hotbed of journalistic opinion posing as news, and not express views that he wouldn’t express on the air at NPR? Seems like NPR should have terminated Williams’ contract at the time he started moonlighting over at Fox. Why wait until now? Probably it was, after all, the Muslim business. That expression of opinion made Williams a little more visible than any other opinion he might’ve expressed on Fox before this. And another factor looms. NPR as well as PBS is constantly under fire from the Right for being left-leaning rather than “objective” in reporting the news. This criticism is a knee-jerk reaction by right-wingers to the criticism they hear about Fox being slanted to the right. If Fox veers off to the right, say the Fox fans, so what? —PBS/NPR veers off to the left, so we’re even. My guess is that PBS/NPR works pretty hard to avoid appearing to favor the Left (or the Liberal or the Progressive or the Right). In other words, they make a concentrated effort to be as “objective” as they claim to be. They want not only to be objective in covering the news: they want to appear objective. And if one of their employees goes over to another network and starts making noises that are far from objective, PBS/NPR gets nervous. That’s exactly what they want to avoid—any appearance that their journalists harbor opinions that might affect how they report the news. Williams fell into that hole. He fell into it the minute he accepted the moonlighting gig at Fox, but, well, you don’t want to fire him because it might appear that you are racist. So you hold your piece. But this time, Williams just went too far. Still, in all the muddle, I think NPR would have been smarter not to fire Williams. It just looks bad. What NPR intended as an assertion of its objectivity came out as a liberal attack on conservative free speech.

OH—BEFORE WE LEAVE

THE SUBJECT, here at hand is Mike Thompson’s cartoon on this infamous

episode. It may be the most accurate portrayal of the Foxes that we’ve had yet.

I’ve always thought Bill O’Reilly is just a joke of a journalist. But he isn’t

just a joke here: he’s a caricature. And so are they all. Thompson’s cartoon—happily, the goal of every editoonist—got under one of its target’s skin. O’Reilly was upset. And so he fulminated on the air about Thompson: “Believe me when I tell you the far left is seething over all of this NPR stuff,” he said. “The blowback has begun. Take a look at this political cartoon in the Detroit Free Press by Mike Thompson featuring me wearing ‘Obama equals Hitler’ stuff.” Then O’Reilly fomented what he conceived as a response fitting the crime: “Please don’t sink to his level,” he cautioned his viewers, “but can you let him know what you think?” Then he gave Thompson’s e-mail address on air. “Keep it respectful,” Old Bill said, “don’t be like Mike.” For days, O’Reilly had been frothing at the mouth about the unprofessional behavior of NPR in firing Williams: a journalist, O’Reilly averred, should not be fired for speaking his mind. No, apparently—if we are to judge from what transpired— a journalist who speaks his mind should have his e-mail inbox crammed with threatening, disparaging e-missives. (Or, in O’Reilly’s case, with bundles of loofahs.) Thompson weighed in a few days later at his blog (in italics):

O’Reilly stressed that his viewers should take the high road in their e-mails to me, which is a little like placing a bowl of Halloween candy in front of kids and telling them not to gorge themselves. O’Reilly’s smart enough to know what would happen. E-mail me they did, more than 2,500 e-mails, many of them unsuitable to publish here, clogged my inbox. I bring this up not because I’m upset; I’ve grown pretty much immune to insults after 20 years in my profession and realize that I forfeit the right to complain about getting bopped in the nose when I voluntarily step into a boxing ring. Besides, I’d like to thank O’Reilly for the significant bump in traffic to my blog. No, I bring this up because I find it strange that O’Reilly and some of his followers fail to grasp the irony of their actions. While defending Williams’ right to free speech, O'Reilly and a number of his viewers tried and failed to bully me for exercising my right to free speech. What it all boils down to for people who behave like this isn’t defending the concept of free speech, rather defending free speech that agrees with their partisan point of view. Many of them decry Williams losing his job because, in their view, he was too conservative. But they want to defund NPR and cause everyone else at the broadcasting company to lose their jobs because, in their view, NPR employees are too liberal. Many of them would stand silently next to people carrying “Obama = Hitler” signs at Tea Party rallies that O'Reilly encourages and promotes, but scream foul when I put the slogan on his shirt in a cartoon. These same people decry what they see as a journalist being punished because of political correctness, then turn around and exercise their own form of political correctness by sending torrents of disparaging and threatening e-mails in a failed attempt to intimidate a journalist who doesn’t agree with their worldview. Then Thompson samples his incoming e-mails:

“I’m not suppose to stupe to your low level. but oh what the hell. I will . I’d like to kick your left wing a--.” “I did not find your cartoon of the NPR firing scenario of Juan Williams to be fair and I will try my hardest to get you fired.” “I had seen your comic strip on Oreille. Your views make you look like a buffoon and a pinhead.” “To call you a scumbag would seriously denigrate all self-respecting scumbags, so I won't do that. You are in-fact a double-douche bag, but I have the same concern..." "I CANT WAIT TO PISS ON YOUR GRAVE...," “YOU CAN'T SEEM TO APPRECIATE AMERICA SO GO TO ANOTHER COUNTRY!!!!!!! FREEDOM OF SPEECH!”

Finally, Thompson concludes (in italics): It goes without saying that O’Reilly has the right to voice his opinions, just as I have the right to voice mine. But his request to his viewers that they carpet bomb me with e-mails was clearly a rather weak attempt to attach a punitive consequence to me speaking my mind. I just hope O’Reilly and his followers can grasp the irony of doing so while simultaneously complaining about NPR attaching a punitive consequence to Williams speaking his mind.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS Mell Lazarus, interviewed in one of last spring’s issues of the newsletter of the Comic Art Professional Society (CAPS), said about his career: “I created Miss Peach in 1957, wrote and drew it until 2002, when I retired the feature. Momma got started in 1970, which had me writing and drawing the two features concurrently until I retired Miss Peach. If my arithmetic serves me, it comes to a total of 85 comic strip years, so far. That means, I’ve produced around 31,025 strips (except for a total of perhaps 9-10 weeks of vacation reprints).”

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words Here are a

couple bimbo covers of forthcoming funnybooks. Don’t misunderstand: I love ’em,

and that’s why I’ve posted them here. Mostly, however, we’re celebrating the

happy coincidence that they appeared in the same issue of Previews. The

Bomb Queen display is delightfully, hilariously outrageous! Just like the

interiors of the books. Tank Girl is somewhat more demure, but still,

seductive. Finally, remember the Tea Party comic strips? Comics with a tea-flavored slant? Concocted by Ward Sutton with Joe Smith on ink-and-instrument? We posted a couple examples last time; now, here’s the whole enchilada, lifted from the pages of Funny Times, a monthly 24 ad-free-page newspaper of comic strips, editorial cartoons and humor columns that is currently celebrating its 25th year with a circulation of about 70,000 or so. You can subscribe (and I recommend it) at funnytimes.com; $25/12 monthly issues. Now, here are those Tea-time comic strip parodies.

When I was cobbling up the Hindsight report last month on the fearsome Iron Jaw of Gleason’s Golden Age Boy Comics, I didn’t realize that this brute who made a comic book career out of returning from the dead had done it again: in January 1992, a villainous character called simply Jaw showed up in the inaugural issue of James Bond Jr. Same scenario—youthful crimebuster and hulking monster with metallic mandible. I ran across the first issue during one of my periodic prowls of flea markets, and there was old Iron Jaw himself on the cover. See for yourself. James Bond Jr. ran for another 11 issues until the end of the year; dunno if “Jaw” returned after his parachute accident in the No. 1, but my guess he did.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv.

SEX IN AMERICA In late September, my wife and I journeyed across Colorado into the largest designated wilderness area in the state wherein, at its center, we stopped at Lake City, the only incorporated municipality in Hinsdale County. En route, the towering vistas on all sides were quivering gently with autumn’s yellow leaf laughter, the green velvet of the pine-covered mountain slopes flecked and often aflame with patches of aspen trees, turned bright yellow and sometimes orange against the green. This annual pageant is one of Colorado’s most spectacular, and every year, Coloradans turn out by the thousands to cruise the canyons and passes in order to witness it. Our views, on this jaunt, were further enhanced by the snowfall of the previous evening, which capped the distant peaks with white—yellow, green, and white, mountain majesty. Lake

City is a tiny town (pop. 375), just a notch above a village: it is today what

Aspen was when I first went there 60 years ago, before it became a haven for

celebrities—a nearly abandoned remnant of bygone glories as a mining “camp” (as

such settlements were called when they cropped up in the 19th century). Some of

the houses are Victorian mansions, gussied up a little by their current owners;

some were Victorian cottages, gussied up likewise. At a tiny steepled church at

the end of a street at the foot of a mountain slope, the sign read: Standing

Tall on Bluff Street. With a few aspen in yellow leaf up the hillside behind

it. Late in the afternoon, almost closing time, I sauntered down the main street. On both sides, 19th century storefronts had become inhabited by 20th century businesses, some, like the hardware store, supplying the needs of the citizenry; others, like antique and collectible shops, tempting tourists. I stopped to inspect the display in the windows of one shop, the signboard of which proclaimed it Artists Cooperative. In one corner of the window was a poster that read: Trollops Framed. I was pondering the import of this information when the proprietor of the shop stepped out to enjoy a few moments of late afternoon air. “What’s this mean?” I said, pointing to the sign. “Come in,” he said, “—I’ll show you.” His art, it turned out, was collecting and framing antique documents—maps and public papers of various kinds. He pointed to the wall where a picture frame embraced what looked like an old ledger-page. It was, he explained, a page of the 1880 census of Lake City, the page that listed the occupants of one of the town’s many saloons. About 10 names adorned the page, 2 men and 8 women. The men gave their occupations as “saloon keeper”; the women, as “prostitute.” I marveled out loud that the whores of yesteryear would be so forthright as to identify their occupations so unabashedly. The man smiled. “Oh, yes,” he said, “they all did, all over the country. According to the 1880 census, there were 2,800 prostitutes in the United States that year. Most of them were in California,” he continued with a grin, “but there were 80 in Colorado, 60 in Leadville [a famous mining camp of that era]. But Lake City had almost all the rest, 8.” Later, pondering these figures, I questioned them. Denver had a fairly active red light district in those days, and I’m sure it was home to more than the remaining 12. But I didn’t think of that until I’d left the shop and its tart enthusiast. “These saloon keepers,” he gestured at the framed document, “were later jailed for some offense— but not keeping a brothel, which is what their saloon was upstairs.” Five years later, in 1885, Colorado conducted its own state census, he said. And the same 8 women were still at work at their 1880 place of business, but this time, they all gave their occupations as “dress maker.” They got religion in just five years. Another sign caught my eye. “Men Taken In and Done For.” It was apparently part of the exterior furnishings of the aforementioned saloon. “If you had to ask what the sign meant,” my informant explained, “they said it referred to laundry.” In various corners of our modern, up-to-date 21st century society, we’re almost as forthright about prostitution as we were in the 1880s. Craigslist, for instance achieved notoriety for its “adult services” section, but the classifieds behemoth has lately shut down this section, pasting a “censored” label over it: the management was reacting to adverse public opinion and pressure from 18 states attorneys general, all of whom objected to the ads for prostitution, saying Craigslist was pimping in a virtual red light district. One of the prostitutes, Melissa Petro, writing at HuffingtonPost (and quoted in The Week) said she had a different perspective. “I was a bored, uninhibited graduate student in need of extra cash, so I advertised my services on the site. By carefully scrutinizing the responses, I screened my ‘dates,’ and best of all, kept every penny I earned. Renting my body to strangers wasn’t much fun,” she admitted, “—in fact, it was emotionally taxing and spiritually bankrupting, which is why I quit. But if consenting adults are involved, it’s not the state’s responsibility—not its right, in fact—to protect people like me from our own decisions. Whether I go on Craigslist to sell a couch or myself is my business.” In another issue—off on a related tangent, I ween—The Week reported October 1 that Men’s Health magazine rated American cities according to how much sex takes place in them. “Seven of the top 15 cities were in Texas, including No. 1, Austin.” In determining the temperature of a city’s six drives, the magazine took into account “condom sales, birth rates, sex-toy sales, and STD rates.” That the ranking was conducted by Men’s Health says something, I reckon, about what is healthy for men. But don’t tell anyone I said so.

***** “Raw Data,” a regular feature in Playboy, recently made the following report (which seems somehow pertinent here): “Up to 80% of women admit to faking orgasms to speed up their partner’s ejaculation because they are bored, tired or in a rush; and 87% of women said they exaggerate pleasure with moans and vocal exclamation because they want to be nice and boost their partner’s self-esteem.” But anyone who’s seen “When Harry Met Sally” already knew. Mostly.

***** ELIOT SPITZER, THE ERSTWHILE GOVERNOR of New York who defrocked himself when his dalliances with a call girl were divulged, has returned to public life---this time, as half host of a CNN talk show; the other half is Kathleen Parker. Which development prompted Laura Kipnis at the Washington Post to observe that Spitzer is not alone in his absolute shamelessness. Take Spitzer’s call girl, f’instance: she is now an columnist at the New York Post, dispensing advice to the lovelorn. But it scarcely ends with this pair, Kipnis goes on: “Family values champion Newt Gingrich continues to pursue the limelight, even after he was exposed as a serial adulterer. [He converted to Roman Catholicism after his third marriage and persuaded the Church to annul his previous marriages; wotta guy!) Even dog torturer Michael Vick of the Philadelphia Eagles has been restored to the pedestal of stardom. With no universal standard of immorality, we no longer put sinners in the stocks. Instead, we put them on tv, forcing them to perform their contributions as mass entertainment.”

***** GAPTOOTHED MODELS are now all the rage, saith Jessica Yadegaran at the Contra Costa Times. That little open space in the middle of the upper dental line-up of a toothy smile (for which Lauren Hutton became famous some years ago but that no other models apparently could duplicate—until now), called a “midline diastema” by practitioners of the dark dentistry arts, is on display on fashion runways all over the place. And last month, Yadegaran reports, on “America’s Next Top Model,” host Tyra Banks sent a 22-year-old contestant from Boise, Idaho, to the dentist to widen her gap. The beauty blogosphere has been buzzing ever since.

***** IN BOULDER, COLORADO, as many as 8,000 of the faux undead were expected at the Zombie Crawl on Saturday, October 23. At the University of Colorado at Boulder, Stephen Graham Jones teaches a course in zombie lore (English 3246). He also teaches Zombie Defense Tactics, or ZDT. The popularity of zombies has been on the rise, he claims, since 9/11. “This year is very zombie-rich. The vampire is just too civilized, elite.” Interviewed by the Denver Post’s Bill Husted, Jones says the great thing about zombies is that they have no responsibilities: “When you’re a zombie, all you have to do is eat. You don’t have to worry about the world anymore.” To which Husted reposited: “Now I get it. If you’re a vampire, you’re in relationships. If you’re a zombie, you just walk around stiff-legged and eat people. The choice is obvious.”

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions Gareth Hinds, whose self-published graphic novel of Beowulf attracted the attention of the publisher Candlewick, continues his self-imposed project of reinterpreting classic texts in the graphic novel format with his 256-page version of The Odyssey in watercolor and pastel. Hinds and Candlewick hope to find a wide audience in schools and libraries, while still appealing to adults. Since Beowulf, Candlewick has also published Hinds' takes on “King Lear” and “The Merchant of Venice,” the latter of which Hinds had also previously self-published. Hinds notes he is attracted to classic texts because they "have so much depth that I can delve into."