|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 265 (August 10, 2010). Headlining this Opus, our extravagant Report on the San Diego Comic-Con, including book previews (Frank Miller’s non-Batman Batman), the contest between Jon Goldwater and Stan Lee, the chances of the Sandy Eggo Con moving out of San Diego, and photos galore, plus Arlo & Janis’ 25th, the Bard in two panels, a Muslim cartoonist talking about Draw Muhammad Day, an exemplary crop of editoons last month, how the news media are screwing us up, and a fond farewell to John Callahan, the most dangerous cartoonist in America. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US Lily Renee Returns The Fifth Wimpy Kid Book Comics Journal Website Goes International Ted Rall Goes to Afghanistan Zuma Some More Ed Stein’s New Comic Strip Muslim Cartoonist Talks about Draw Muhammad Day

SANDY EGGO CON Eisner Awards News at the Con Frank Miller’s New Non-Batman Book Crowd Control Gone Mad Archie Comics Con’s Importance to San Diego

Schulz’s Peanuts Legacy by the Numbers

EDITOONERY This Month’s Exemplars New Staff Job A-borning Steve Breen’s Oils

THE FROTH ESTATE Shirley Sherrod Shows How Badly Journalism Is Being Done Ditto Gulf of Mexico and the Deficit Wash Post Scores Big and Behaves Like a Journalistic Enterprise Newsweek Saved Dan Schorr and the 24-Minute Gap

BOOK MARQUEE The Man with the Getaway Face Bite-sized Bard

PASSING THROUGH Fierce John Callahan on Wheels

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits Newsweek for August 9 includes a highly unusual “news” article—a three-age discussion of a comic book artist who hasn’t produced comic book drawings for over fifty years. Lily Renee is a familiar name to comics historians who frequent the books and articles of “herstorian” Trina Robbins, but neither Renee’s name, her former celebrity or her current work justify a “news” article, so this piece, entitled “A Real-life Comic Book Superhero,” is clearly an accolade of respect and affection by Adriane Quinlan. Renee, whose actual last name is Phillips, disappeared from the comic book industry in about 1949, and many may have presumed that she died long ago. She didn’t. Not in the post-war period during which she married and began raising a family. And she didn’t die in the years before World War II either—when she, a Jew, fled her native Austria and lived for two years a teenage refugee in England. How she finally reached the U.S. and a career as a model and then as a comic book illustrator at Fiction House doing “good girl art” (which Quinlan doesn’t quite understand) is the gist of Quinlan’s article, worth reading and filing. The last of Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid books, entitled The Ugly Truth, will reach the market on November 9 with a massive five million first-printing from Amulet Books, an imprint of Abrams. "To me, the fifth book is the linchpin of the series," said Kinney in a statement sent to John Sellers at publishersweekly.com: "Since Greg Heffley is a cartoon character but also a literary character, I've always wondered if he should grow up or stay in a state of arrested development forever. This book answers that question once and for all." From

Calvin Reid at publishersweekly.com: The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, a

nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting the First Amendment rights of

comics artists, publishers, retailers and librarians, announced that comics

retailer Chris Powell is stepping down as president and that cartoonist Larry

Marder has been elected to succeed him. In addition, Dale Cendali, an

intellectual property lawyer and partner at the firm, Kirkland & Ellis, has

been named to the CBLDF board. Marder, probably best known as the creator of

the critically acclaimed comics series Bean World, was elected unanimously by

the board. Marder is also editor of the Liberty Comics Annual, as yearly

comics anthology featuring some of the best known comics creators that is used

to raised funds for the CBLDF. The Liberty Annual has raised more than

$50,000 with its first two issues and there will be a new issue of the

anthology in October, featuring such artists as Garth Ennis, Don Simipson,

Evan Dorkin and more. By

the time you read this, the indefatigable cartoonist gadfly Ted Rall will be en route to his destination in Afghanistan and those environs, from

whence he and a couple other cartooners, Matt Bors and Steven Cloud,

will tell us the truth about the “stans.” Rall reports that his beard, which he

has grown in order to blend into the local populace, is looking better. He’d

better be careful: if it looks too good, it’s a dead give-away as being the

beard of a despised foreign infidel. Or so I’ve been told. Here’s Rall’s first

cartoon filing on the adventure. Zuma some more: in the July 5 issue of The New Yorker, Charlayne Hunter-Gault, the distinguished African American journalist once with the PBS News Hour and now freelancing, spending half the year in South Africa, produces a long article on South African President Jacob Zuma, a personage we’ve spent a little time pondering lately while considering Zuma’s threats to the political cartoonist Zapiro. Hunter-Gault puts the best spin on all of Zuma’s endeavors, but near the end of the article, she summarizes as follows: “Since coming to power, Zuma has consistently countered expectations: he has defended his personal promiscuity while become an avowed AIDS activist; he is a populist who has maintained free-market economic policies and alienated the poor; he is a powerful leader in a dominant party who has a hard time taking action.” Scarcely a ringing endorsement. Editoonist Zapiro might be right about Zuma. Arlo & Janis, the comic strip that began as the chronicle of a Baby Boomer couple and its young family, passed the quarter century mark on July 29. To commemorate the occasion, cartoonist Jimmy Johnson ran some vintage strips in print, and online, at his website, he supplied commentary. Said Johnson at his site on Monday July 26: “I really wanted to do a comic strip about a society of talking dogs, called ‘Baskerville,’ but talking-animal strips were out of favor with newspaper editors at the time, and young families were all the rage. “Most of the family-oriented strips targeted at the baby boomlet of the 80s are gone now, and most of the mega-strips launched since then have involved talking animals, but I’m not complaining. Incidentally, a lot of us are again talking of moving to the country and growing much of what we need.” Arlo

& Janis is perhaps the only comic strip that reminds us regularly that

its title characters are sexual human beings who love each other, and Johnson

always manages to perform this feat with great empathy as well as comedy.

Here’s my all-time favorite. ***** Quoting Editor & Publisher: The Standard-Examiner in Ogden, Utah, recently received an unusual request from a man on trial for murder: Bring back two comic strips. Jeremy Valdes, who is facing the death penalty in a double homicide, recently sent an e-mail to the Standard-Examiner in which he commented on a June 25 hearing on a motion to suppress his apparent confession to the murders. In the e-mail he commented on a police officer cousin's testimony against him, calling another officer drunk on the stand, and calls into question the credibility of his co-defendant Miranda Statler, the primary witness against him. Valdes also took the Standard-Examiner to task for its coverage, and ended his note by asking that two comic strips be reinstated: "While I have you here, my friends and I would like to request that you bring back the comics Pearls Before Swine and Garfield. Thank you." His attorneys objected: "We absolutely do not like clients doing that," Ryan Bushell, Valdes' lawyer, told the paper. "It hinders what we're trying to do with a case. We want to control what goes out to the press." [So, apparently, does prisoner Valdes.—RCH]

***** Here’s a note from my friend Ed Stein, formerly the editorial cartoonist on the Rocky Mountain News, freelancing since the demise of that honored albeit tattered tabloid: “On September 20, my new comic strip, Freshly Squeezed, distributed by United Feature Syndicate, will launch in daily newspapers. Those of you who followed my Denver Square comic strip feature in the Rocky Mountain News will recognize the characters, although they’ve been updated a bit. In the new strip, Irv and Sarah, Liz’s parents and Nate’s grandparents, have lost their retirement savings in the economic collapse, and have moved in with their grown children and their grandchild. That’s when the inter-generational fun begins. “According the Pew Research Center, multi-generation families are growing rapidly, with 49 million Americans living in multi-generation homes as of 2008, largely as a result of economic trends, and that number is surely larger today. Folks over 65 are the most likely to live this way. In other words, the strip is relevant and timely. And well-drawn and funny, and emotionally honest, if I do say so myself.” Probably Stein can get away with saying the strip is honest because, deprived of a salaried perch for the last 18 months or so, he has probably faced situations not unlike those Irv and Sarah are facing. Stein’s Denver Square strip was a gem, a shining moment in newspaper comic strippery, as some of you, who recall Opus 224 where we reprinted some of the strips, will attest. Samples of Freshly Squeezed appear here: http://www.indenvertimes.com/announcing-%E2%80%9Cfreshly-squeezed%E2%80%9D-my-new-comic-strip/

**** A

Muslim Cartoonist on "Draw Muhammad Day" Regardless of the fudge on her profession, Wilson seems to me to have something valuable to say on the Muhammad cartoon controversy. I don’t really intend to revive that issue, flames and all, with this, but it was gratifying to read something that very nearly echoed my own sentiment—and this time, written by a Muslim. Herewith, her entire Washington Post “On Faith” blog of July 15:

When Seattle cartoonist Molly Norris was put on an Al Qaeda hit list for her Draw Muhammad Day project, my inbox started filling up. Since I'm one of the only practicing Muslims in the American comics industry, people assumed I had some kind of profound insight into the reasons these cartoon incidents keep flaring up. But the only explanation I have is too simple to satisfy anyone: they happen because hate sells. It sells in the West, where anti-Muslim hate groups feed on incidents of Muslim rage; it sells in the Muslim world, where extremists are only too happy to use examples of Western intolerance to win over new recruits. This is the reality we live in: any satirized depiction of the Prophet Muhammad feeds into a global propaganda war, whether the artist intends it or not. There is no longer any such thing as artistic immunity in the battle of images, and to think otherwise is fatally naive. Molly Norris thought otherwise. But as soon as she realized what she'd gotten herself into, it was too late: by taking the offending images off her website and issuing a bewildered apology, she enraged the Islamophobes who were ready to hail her as a martyr to their cause. In the opposing camp, Al Qaeda spokesman Anwar Al Awlaki was unwilling to give up such a plum opportunity to rally support for his jihad. A tepid explanation was not what either party wanted. Extremists of all stripes need blood and conflict in order to survive. Molly Norris has no true supporters: in order to be of any use to either the Islamophobes or the jihadis, she must be a blasphemer whose life is in jeopardy. As a peacemaker she loses her utility. This is the central tragedy of these endless cartoon scandals. No one is looking for a resolution. Drawing insulting depictions of the Prophet Muhammad has become a favorite pastime of hipster racists, whose bulbous-nosed bushy-bearded 'satire' resembles the anti-Semitic cartoons of the Third Reich. Thanks in no small part to the vigorous, often violent outcry from hardliners in the Muslim world, these artists are elevated to a kind of freedom-of-speech sainthood whether their work has any real merit or not. Death threats are issued, lives pointlessly imperiled, careers of pundits—never themselves in any danger—made overnight. Noted American Muslim leader Imam Zaid Shakir put it best: this isn't the clash of civilizations; it's the clash of the uncivilized. Molly Norris never drew a picture of the Prophet Muhammad as a wild-eyed Semitic bogeyman. She drew a cartoon teacup, the sort of thing you might find in a children's picture book. Her intent was to inject a little innocent humor into an increasingly absurd conflict. What she didn't realize is that there is no room left for innocence or humor in what has become a cynical exercise in mutual provocation. In honor of Draw Muhammad Day, her legion of unasked-for followers posted cartoons that were more and more grotesque and hate-filled. The result was a threat against Norris's life from an Al Qaeda spokesman—and fellow American—who does a better job of caricaturing himself than a cartoonist ever could. She disavowed her own comparatively innocuous cartoons, took down her website, and went into hiding. But the battle begun in her name rages on. What Norris failed to understand is that by creating events like Draw Muhammad Day, artists hurl rhetorical stones that go straight through their enemies and hit Muslims like me. Al Qaeda isn't hurt by Draw Muhammad Day. Its entire PR campaign is built on incidents like these. Without the Molly Norrises and Jyllands Postens of the world, Al Qaeda would have to get a lot more creative with its recruitment strategies. Artists who caricature the Prophet inevitably claim, as Norris has done, that they never meant to hurt ordinary Muslims, but ordinary Muslims are the only ones who are hurt. As a Muslim in the comics industry, I spend more time than is good for my mental health defending the art and the religion I love from each other. Events like the fallout from Draw Muhammad Day make me think I'm wasting my time—the hate runs too deep on both sides. My conscience won't let me support the criminalizing of art, but neither will it let me support a parade of cartoons depicting lurid, racist stereotypes of Arab men and passing them off as satire of a holy figure. Molly Norris claims she never meant for this event to become a hate-fest. As silly as that sounds—anyone who's spent more than half an hour on the internet could have told her how this would turn out—I believe her. If provocation was her objective, she could be basking in the light of notoriety as we speak. Instead she's being vilified not only by extremists like Al Awlaki, but by her own former supporters. She's learned the hard way that this conflict was never about her art or her ideas. As her fans turn their backs, looking for someone with a better stomach for scandal, it's clear that no one was ever really interested in what she had to say. RCH again: I’m not sure whether Wilson knows Norris, but if they don’t know each other, it’d be a trifle strange: they both live in Seattle in a hotbed of alternative and would-be cartooners.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

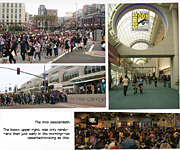

THE SANDY EGGO CON Gauging the Chaos and Playing Dress-up Color, sound, and slurrying lines. The gigantic exhibition hall of the San Diego Convention Center is filled with a riot of color, hundreds of exhibit booths, each screaming in the vibrant hues of its product for our attention. The visual cacophony is augmented by the voices of thousands of people creating a monotonous drone of sound, punctuated occasionally by a shriek of joy or shouts of excitement, and through it all, a distant rhythmic beat of the sound of combat coupled to the orchestral din of some new movie’s sound track, volume cranked up to advertise itself. And the aisles teem with costumed humanoids, moving to and fro in lines because no other way of moving is possible: only lines move. And they move slowly. People are packed in so close together that they bump up against one another as they move, all at the same speed, a processional crawl, a never-ending stream, a flood, of bodies. We may now safely assume that the Comic-Con has arrived as a fixture of American popular culture. Both USA Today and Entertainment Weekly did articles about the event in the weeks leading up to it and covered it feverishly once it got going. The Comic-Con has arrived, but comic books have not. In fact, they’ve been shoved quietly into remote niches. Only one of the USA Today stories was about comic books, a focus on small publishers (IDW, Top Shelf, etc.). And in its post-convention report—an extravagant 11 pages—Entertainment Weekly concentrated solely on movies: “For four days every summer,” the magazine gushed, “the geeks inherit the earth—or at least Hollywood. From July 22 to 25, the entertainment industry relocated to San Diego ... to stoke the buzz among the 150,000 fanboys and fangirls in attendance.” Actually—or, at least, according to David Glanzer, the Comic-Con’s pr guy—attendance was 125,000-130,000, almost exactly the limit imposed by the city’s fire marshal. Movies and tv shows previewed or excerpted included Green Lantern, Captain America, Tron: Legacy, Thor, Cowboys & Aliens, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, The Green Hornet, True Blood, Dexter, The Big Bang Theory, Hawaii Five-O, The Event, The Walking Dead, Falling Skies, The Avengers, No Ordinary Family, Nikita, and The Cape among, I assume, a few dozen more that I missed references to, many, like Scott Pilgrim and The Walking Dead, based upon their comic book origins. In USA Today’s wrap-up on Monday, July 26, reporter Bill Keveney speculated that “press and fans wondered if one of the new tv shows presented could break out as Lost once did, capturing the public imagination and attracting both diehard and casual fans. It’s too early to tell whether any of this season’s entries will become an immediate hit, as Lost did in the fall of 2004 after screening at Comic-Con in the summer.” But everyone involved in these shows hopes, Keveney goes on, “to generate early positive buzz, one of the great potential benefits of a Comic-Con screening.” In the five pages EW devoted to these subjects, comics were not mentioned. Not once. And in the ensuing six-page glimpse of “The Stars of Comic-Con,” no cartoonist was mentioned. Just actors and actresses. USA Today’s film reporter Scott Bowles noted (July 23) one of the highlights of actor appearances during the Con (July 23). Promoting the animated film Megamind, Will Ferrell arrived, “dressed as his all-blue villain character and looking a lot like a Smurf on steroids. ‘I brought breakfast!’ Ferrell exclaimed, bringing out six donuts and a jug of orange juice for the standing-room-only auditorium. ‘Sorry,’ he continued, ‘—I wasn’t expect this many people. You can share.’” Five minutes of the film were shown, and the female audience screamed when it was announced that Brad Pitt would drop by to answer questions. He didn’t, but “it wasn’t a preposterous notion,” Bowles said, “—his companion, Angelina Jolie, was here to promote her new movie, Salt.” Actors all over but not so many cartoonists. What can we expect? The Comic-Con itself is startlingly shy of cartoonists and comic books. While this year’s special guests included comic book artists and writers, they numbered only a third of the total of 60; and only two, Keith Knight and Berkeley Breathed, were syndicated newspaper, or comic strip, cartoonists (and Breathed, having given up the game, is history not contemporary). A far cry from the Con’s early days when strip cartooners were conspicuous at the event. (Knight, by the way, was presented with the once-prestigious Inkpot Award during his Spotlight Session.) And in the exhibition hall of the world’s biggest comics convention in the booths of the country’s two largest comic book publishers, DC Comics and Marvel, no comic books were on display. Not one. Every now and then, the proprietors of these gargantuan two-story, high-rise booths gave away copies of a title, but nothing was on display—no rack of comic book covers representing the dozens of titles each company publishes every month. Instead—action figures galore. Life-sized and small. Giant-sized renderings of superheroes on billboard walls. Movie sets for superhero movies. But no comic books. Golden Age funnybooks have all but disappeared. The good stuff has long gone; what’s left are the comic books of Charleton and other small bore publishers, all priced too high for me. The “Gold and Silver Age Pavilion” consisted of four or five short (six booths long) aisles, a net square footage a little less of just that of the booths of Hasbro and LucasFilm combined. Or Leggo, Mattel and Toynami combined. Or an area called “Toygrowers Cultyard.” (Note: there are no longer enough Golden Age comic books to justify a “pavilion”—aka, a reserved section of booths—all to themselves; Silver Age must be added in, and the Bronze Age, 1970-85, is likewise a presence in the “old comics” pavilion.) Movies, tv shows, action figures, toys, islands of illustrators selling their wares (pricey prints as well as original art), webcomics. And costumes. Everywhere you look, on parade your favorite superheroes and superheroines, the latter often in the scantiest version imaginable of their usual apparel. But some costumes do not seem to denote any familiar comic book character. These are solely the inventions of their wearers who have seized upon the wholesale opportunity the Con offers to play dress-up. That’s what all the costumed masses are doing—playing dress-up. And on every side, as they strut their stuff through the hallways and byways of the Convention Center, are lines of amateur photographers peering into cell-phones as they focus on the colorfully attired objects of their temporary affections. G4, a tv network, was on hand and broadcast four continuous hours of interviews with actors and producers on Saturday. The principal on-camera personnel were a man and woman whose exuberance was hyper, like little kids on Christmas morning nearly knocking over the tree in a panic to find their presents beneath. The woman (sorry: names escape me), like all tv

interviewers I saw eddying about the premises, was movie-starlet attractive,

and she was wearing a short dress, thigh-high boots, and a sleeveless top with

a plunging neckline. Her long black hair hung down both behind and in front of

her shoulders, the latter tresses frequently obscuring our view of her bosom,

but she was aware of this wardrobe malfunction and had developed a habitual

gesture of flicking her hair out of the cleavage and back onto her shoulders—a

repetitive gesture that was just frequent enough that it was annoying, ruining

the eroticism. But maybe only DOMWFOF notice such things (Dirty Old Men with

Food on Faces). Despite all this carping, the Comic-Con, even with a mere dearth of comic books visible, has enough that appeals to the same sensibilities as dote on comics. Withal, it’s the only giant comics mall in America, a massive opportunity to buy comics stuff or to get comics stuff free. Still, cartooners like Scott Kurtz, creator of PVP, aren’t keen on the “new” ambiance: “Comic-Con is hurting nerd culture in a broad and permanent way,” Kurtz told Wil Wheaton at techland.com. Wheaton almost agreed: “I’m not thrilled when I sit in the lobby of my hotel and see twenty fancypants Hollywood types for every authentic geek.” But he doesn’t think the Comic-Con’s “evolution” is hurting our “culture.” “Nerd culture”? Well, I suppose. But I’ve always thought a “nerd” is a person outside of mainstream culture, so how could there be a “nerd culture”? A ponderable. For another time, doubtless. Yes, I’ll be back next year. You can’t find comic books at DC Comics or Marvel, but you can find graphic novels at IDW, Dark Horse, Fantagraphics, and Image and in the small publishers’ section, and reprints of masterpieces in the medium, and original art in Artists Alley and elsewhere in the hall where cartoonists and illustrators sit behind display tables, showing their wares. And I’m not the only one who’ll be back: you could buy a ticket for next year’s Con this year during the festivities. Reportedly, 15,000 tickets for next year have already been sold. But for the moment, in a confessedly futile attempt to capture and convey to you, the readers of a static medium, some sense of the color, sound, and slurry of the actual Con, here’s an extensive gallery of real-life photographs by Yr Intrpd Rprtr.

THE TOP WINNER AT THE GALA EISNER AWARDS ceremony held July 23 was graphic novelist David Mazzucchelli, whose critically acclaimed Asterios Polyp (published by Pantheon) garnered the Best Graphic Album–New award as well as Best Writer/Artist and Best Lettering. The other creators who received multiple awards were manga creator Yoshihiro Tatsumi for A Drifting Life (Best Reality-Based Work and Best U.S. Edition of International Material–Asia), published by Drawn & Quarterly; artist Jill Thompson for Beasts of Burden (Best Publication for Teens, Best Painter), published by Dark Horse; artist J. H. Williams III for Detective Comics (Best Penciller/Inker, Best Cover Artist), published by DC; and writer/artist team Eric Shanower and Skottie Young for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Best Limited Series, Best Publication for Kids), published by Marvel. A complete listing of all the Eisner winners can be found at comic-con.org. At The Comics Journal website (tcj.com), blogger Alex Boney wasn’t thrilled to pieces by the Eisner results.”I’m not surprised by most of it,” he writes, “but I’m pretty disappointed with a lot of it. I have a hard time believing this many people voted for Captain America No. 601 as the best single issue of the year, and I can’t believe I’m the only reader who thinks Walking Dead peaked a couple years ago. I’m also surprised that Vertigo got shut out with as many quality new books as they’ve debuted in the past year. It’s ridiculous that The Unwritten received no industry recognition.” And Boney took a short detour away from listing prizes to notice that “Denis Kitchen announced at Friday’s Eisner Awards that Will Eisner’s A Contract With God is currently in film development. The film will be produced and adapted from Eisner’s book by Darren Dean, and the four narrative chapters will be directed by four different directors: Alex Rivera, Barry Jenkins, Sean Baker, and Tze Chun. I’m just thanking the gods that Frank Miller didn’t get his hands on this one,” Boney snarked.

*****

NEWS AT THE CON. Sandy Eggo is the place where announcements are made and new projects flogged mercilessly. Here, for instance, is a news release from Abrams ComicArts announcing that it will publish Harvey Pekar’s last book, Yiddishkeit, which had been completed by the time he died earlier this month. The book’s title means “Jewishness” in Yiddish, an expression generally used to refer to Yiddish culture, and that, not surprisingly, is what the book is about: following an autobiographical section at the beginning, the main narrative of the volume consists of stories on different aspects of Jewish and Yiddish culture. Paul Buhle, who edited a number of books written by Pekar, assembled the book; at approximately 240 pages, the volume is slated for publication in the fall of 2011. Forthcoming tomes for the fall include Jerry Robinson’s biography, subtitled Ambassador of Comics. Robinson is the only cartoonist to have served as president of both the National Cartoonists Society and the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, and among his other accomplishments is working out the pension deal for Siegel and Shuster with Warner Bros. His watershed history of comics will also be reprinted this fall. And Chip Kidd has another of his fancy-footwork books on deck, Shazam: The Golden Age of the World’s Mightiest Mortal, touted here as a 250-age “finely designed coffee table book.” That means, no doubt, that Kidd’s book design, as is almost always the case with him, will be more prominent than the content of the volume. The irony here is that the artist whose style formed the image of Captain Marvel, C.C. Beck, was famous for his irascible objection to the modern tendency to draw heroic bodies with every tendon delineated in detail. My guess is that Beck would favor a simple-looking tome. The oddest book I saw as I was buffeted down the bustling aisles was Siegel and Shuster’s Funnyman: The First Jewish Superhero (194 7x10-inch pages, b/w and color; paperback, Feral House, $24.95). The book reprints several of Funnyman’s comic book stories, some Sunday strips, and some dailies, and it comes with argumentative text by Thomas Andrae and Mel Gordon. Among Gordon’s pronouncements: the Jewish sense of humor was born in a July day in 1661. I haven’t read much of the tome, but I fully expect that it will assert Funnyman’s Jewish roots; but I’m not sure it will do so in all seriousness. Something about Gordon’s prose leads me to think he may not be altogether serious about his thesis. We’ll see. And when we do, I’ll let you know. Deb Aoki at publishersweekly.com reports that “lots of news and trends” in manga were announced during the Con: “The most intriguing developments to come out of this year's show were both a nod to manga's past and a look toward its digital future. Indie publishers like Fantagraphics, Drawn & Quarterly and Top Shelf have been making more moves toward publishing classic manga in classy, collectible and affordable editions. For the future, Japanese publishers Square Enix and Kodansha announced plans to offer manga online in English to international markets (including North America), and U.S.-based manga/manhwa publisher Yen Press revealed more about the new online-only edition of their Yen Plus anthology magazine.” “Despite the bombast of Hollywood studio hype,” publishersweekly.com’s Heidi MacDonald said, “indie comics publishers still made some noise with their own announcements.” Drawn & Quarterly plans to produce a memoir, Over Easy, by Mimi Pond, “a cartoonist-illustrator and writer perhaps best known for writing the first episode of ‘The Simpsons’; her book will tell the tale of her youth in the growing punk rock scene of 70s Oakland. ‘In this day and age of the graphic novel, it's astonishing to come across a fully-realized and seasoned cartoonist who has yet to release comics in long-form,’ said acquiring editor Tom Devlin.” D&Q will also add to its growing library of "gekiga" manga “two books from manga legend Shigeru Mizuki, perhaps the most famous living cartoonist in Japan. Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths is a semi-autobiographical account of the final weeks of WWII, as Japanese soldiers deal with orders to die for their country. (Mizuki served in the war and lost an arm.) NonNonBa is a less horrific story set in Mizuki's youth in the 30s, as he dreams of creating his own worlds with the help of an old neighbor woman.” Top Shelf announced “a slew of new projects”: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century No. 2: 1969, the latest in the series by Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill, and new works by the publisher’s regular stable of cartoonists: The Homeland Directive by Robert Venditti and Mike Huddleston, Any Empire by Nate Powell, Super Natural by Matt Kindt; The Underwater Welder by Jeff Lemire; and a new volume of Incredible Change-Bots by Jeffrey Brown. The publisher also has new works by Jess Fink and Jennifer Hayden on tap as well as a reprinting of Kagen McLeod's Infinite Kung Fu, and Masahiko Matsumoto's Cigarette Girl, “a collection of short stories by another founding father of gekiga who worked alongside Tatsumi. Finally Top Shelf will bring to English Lucille by Ludovic Debeurme, a recent prizewinner at Angouleme.” Fantagraphics astonished classic comic strip fans with the news that they were teaming with Disney to publish all of Floyd Gottfredson's Mickey Mouse strip, which Gottfredson produced from 1930 to 1976, in a series of deluxe reprints. “Considered the definitive version of the Mouse,” MacDonald noted, “Gottfredson's Mickey is a bold adventurer with a temper and a tart tongue. In his 45-year run on the strip, Gottfredson introduced such characters as the Phantom Blot and Mickey's nephews, Morty and Ferdie. The multi-volume series begins publishing in May 2011 and will be designed by Jacob Covey.” At a panel session during which Fantagraphics’ Gary Groth announced the Mouse plan, longtime Disney fan Dana Gabbard of the Duckburg Times was flabbergasted and expressed both astonishment and disbelief: “Did you really say you were going to publish all of Mickey Mouse?” he blurted out. “Yes,” said Groth. Later, Gabbard voiced his wonderment to me: Disney has always been so hard-nosed about reprint rights—sinking Gladstone’s comic book business, for instance—how did Fantagraphics get the Mouse job? My guess: Fantagraphics has established its grown-up bona fides with the Peanuts books.

FRANK MILLER’S RAGE Ever since 9/11, Frank Miller has been brooding darkly about a Batman story that would send the Caped Crusader on a blood quest against Al Qaeda, and that story is on the cusp of finally appearing, albeit not from DC Comics—and the protagonist isn’t Batman. Over coffee at the U.S. Grant hotel during the Comic-Con, Miller told Geoff Boucher at the Los Angeles Times that “it’s almost done; I should be finished within a month. I decided partway through it that it was not a Batman story. The hero is much closer to 'Dirty Harry' than Batman. It's a new hero that I've made up that fights Al Qaeda. The character is called The Fixer,” Miller went on, “and he's very much an adventurer who's been essentially searching for a mission. He's been trained as special ops and when his city is attacked all of a sudden all the pieces fall into place and all this training comes into play. He's been out there fighting crime without really having his heart in it—he does it to keep in shape. He's very different than Batman in that he's not a tortured soul. He's a much more well-adjusted creature even though he happens to shoot 100 people in the course of the story. My guy carries a couple of guns and is up against an existential threat. He's not just up against a goofy villain. Ignoring an enemy that's committed to our annihilation is kind of silly. It just seems that chasing the Riddler around seems silly compared to what's going on out there. I've taken Batman as far as he can go." Miller continued: "It began as my reaction to 9/11 and it was an extremely angry piece of work and as the years have passed by I've done movies and I've done other things and time has provided some good distance, so it becomes more of a cohesive story as it progresses. The Fixer has also become his own character in a way I've really enjoyed. No one will read this and think, 'Where's Batman?'" The

book’s title is Holy Terror, and Miller doesn’t have a publisher yet: he

wants to finish the book before finding a publisher.

THE COMIC-CON HAS BECOME SOMEWHAT BETTER at crowd control over the years. Registration lines moved faster this year than in previous years, seems to me; certainly, the credentialing of pre-registered professionals was smooth and quick. Or maybe I just got there at the right instant to avoid a long line. Managing the mob is the assignment given to security firms, and the Con hired several this year instead of relying upon a single firm, which, David Glanzer averred, “kept any one firm from being stretched too thin and increased response time.” Dunno about “response time” (first responders?), but security gorillas were everywhere in their t-shirts uniforms of different colors, and, as always with security personnel, they were expertly clumsy in bullying innocent bystanders into obeying numerous secret rules. Once, for instance, I was standing near a railing that overlooked the escalator that was transporting fans from the first floor to the second. I was merely killing time until a session would begin in the meeting room behind me. A gorilla in a white t-shirt came up and told me I couldn’t stand there, leaning on the rail: “Fire marshal rule,” he explained. In my experience, fire marshals generally seek to keep passageways to exits free of encumbrances and also prohibit crowds from becoming too numerous for a given facility. The central idea of a fire marshal’s function is to ensure safe egress for people in the event of a fire. I don’t know how my standing next to a railing would interfere with anyone’s leaving the building—neither the rail nor I were blocking any exit routes—but you don’t argue with security gorillas: generally speaking, they haven’t the subtlety mental faculty to deal with such nuances. Once on the floor of the exhibit hall, a phalanx of security gorillas formed to block one of the main aisles. Apparently the lines forming to collect free stuff at a booth had jammed the aisle, so the gorillas’ solution to the dilemma was simply to shut off the traffic down that aisle, so to get to a booth a few feet down the aisle—beyond the wall of guards—one had to leave the hall altogether and come back in at another entrance. Crowd management on that part of the second floor where many meeting rooms are was achieved by designating alternate aisles “entrance” and “exit” aisles. All the meeting rooms have two banks of doorways, each opening onto a different aisle—one on the “entrance” aisle, the other on the “exit” aisle. Traffic was handily controlled by directing everyone seeking entrance to a meeting room down the “entrance” aisle; people leaving meeting rooms left by going out the doorways emptying into the “exit” aisle. In operation, each of the aisles was a “one way” aisle: one way in, one way out. It worked fine as long as everyone behaved like a mob. I inadvertently stumbled into a glitch in the system when I decided to take a short cut. A back aisle runs behind the meeting rooms, and when I exited one meeting into an “exit” aisle, I thought I’d use the back aisle to get to the “entrance” aisle on the other side of the meeting rooms and hence to the next session I wanted to attend. Alas, when I got to the “entrance” aisle, I was walking down it the wrong way on the one-way thoroughfare: I was walking from the “back,” which was against the flow of traffic coming into the “entrance” aisle from the other end. Security gorillas immediately protested: “Exit the other way,” several shouted at me. “I’m not exiting,” I yelled back, “—I’m entering.” This baffled them momentarily—long enough for me to get where I was going without being tackled and beaten to my knees. Douglas Wolk has posted a thoughtful and wholly practical cluster of recommendations outlining six things the Comic-Con could do to reduce stressors and irritants that make the show less enjoyable: http://techland.com/2010/07/30/emanata-when-I-am-king-of-comic-con/ It’s worth a long look, and I hope Comic-Con minions take it in and give it a home.

ARCHIE COMICS, not a usual presence of any notable dimension at the Con, occupied a modest 2-3 booths and appeared more than once on the program, promoting its new image with its turn-around edgy funnybook stories: Archie marrying both Veronica and Betty, a new scholar at Riverdale High School—a gay (gasp!) guy— and (fan fare) a new line of superhero comics. And Sam Hill is going to make a comeback! Writer Michael Uslan, academic gone Hollywood, was on hand, enthusing about the “sleeping giant awakening,” and Archie’s co-CEO, Jon Goldwater, grandson of one of the company’s founders, was there to tout these ventures. Long

black hair slicked straight back from a high forehead, Goldwater, with his

ready grin and a steady rattle of hyperbolic patter about how the company was

expanding into other media on other platforms, could, it seemed to me, give

Stan Lee a run for his glitteratti title as the midway’s glibbest and flashiest

promoter, so I went to the session at which Goldwater and Lee appeared to flog

Archie’s new superhero titles created by Lee. Which of these champion hustlers

would prove the most sensational? Stan the Man quickly secured his hold on his title. At the head table were seated Goldwater and several Archie minions behind identifying name cards, but next to the speaker’s lectern, the chair was vacant behind the placard that read “Stan Lee.” At the microphone, one of the minions announced that Stan had been delayed—and then, after a momentary groan of disappointment, with the projection screen in front beginning a crawl of images of the new superheroes as a fan fare, Stan burst into the room! Wearing a gleaming white leisure suit, he strode in from a side door—the crowd went crazy, standing and applauding and cheering as Stan mounted the stage and walked across its width to take his chair. He began, without further ado, talking, apologizing for being late (which tardiness was, by now, obviously a ploy to gain attention—as if any of those in the room were paying attention to anything else). In his patented barker spiel flaunting alliteration, Stan, with the visual aid of the projection screen, introduced his new band of superheroes, the Super Seven—Laser Lord, Micro, Strong Arm, Roller Man, Kid Kynergy. Two more, but I’d lost interest. The drawing styles on display were the usual super-slick renditions—expert but lacking any individual style. Factory assembly-line art. These were “reality heroes,” Stan kept saying—“reality comic books.” I was out the door. Stan was losing his voice, speaking in a croak—but he easily dominated the room. Goldwater grinned and stared out at us, and I left, having satisfied my curiosity about which of them would emerge the champion pitchman. But Archie’s superheroes were not the only Stan Lee creations to debut at the Con. Over at Boom Studios, another trio of Stan Supers were announced: the Traveler (who travels time), Soldier Zero, and Starborn. When asked about what Stan brought to these series, Boom’s chief creative officer, Mark Waid, told Henry Hanks at CNN: "What comics have become is like WWE wrestling matches, with good guys and bad guys, but the humanity gets lost." But Lee’s characters have humanity: they always have to make a sacrifice to be a hero. "With [Lee], you get to embrace the best parts of humanity, instead of getting caught in a cynical world.” To which Lee added: “Too often, writers think, 'I think that [readers] will like this.'" But writers should “write from the heart,” not the marketing department’s head. “If you do something you will like,” he said, “chances are the readers will like it also." An admirable attitude, nicely phrased. For David Pepose at Newsarama, Waid described the Traveler as “the kind of character Stan and I both enjoy writing the most—a smart, clever man whose dry sense of humor hides some pretty dark emotions and tragic secrets. Unlike with Starborn and Soldier Zero, where we're opening with the origins of the characters, the Traveler begins with our hero already in action. Watching his backstory slowly unfold is the whole engine of the first four issues.” The “Stan Lee quality” of the Traveler, Waid went on, is that he is “a man of science is redeeming himself for overstepping his bounds to tragic end." Stan's stories are full of the glories of science, Pepose elaborated, but also the consequences. “The Traveler follows in that vein.” Asked to describe their working relationship, Waid said: “Lots of energy. Sometimes him having to remind me to keep it simple. Sometimes me reminding him that he's hit certain ideas before. But I like the mutual chemistry. Man, that guy is going places. I can't wait to hear the point at which the readers can see what we're really doing with this first story. It seems simple and it seems straightforward at first blush—but time-travel is at the heart of this tale, and not everything is as it appears!” Tantalizing. But do we really need more comic book superheroes? Do we not already have a surfeit of them? And without denigrating Stan’s accomplishments in revitalizing superhero comics in the 1960s, I’m not sure his style of four-color superheroicism is any longer attuned to today’s readers. Stan can still create comic books, I’m sure; but they’re comic books of fifty years ago albeit brought back to life, and they reek of museum must: they’re collectors’ items now, not newsstand blockbusters. Still, it was a treat to watch “the Man” in action—white suit, visual fan fare, bubbling alliteration, a blatantly obvious publicity stunt wherever he is. Stan Lee, ladies and gents.

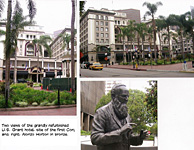

THE TOWN OF SAN DIEGO TOOK A WHILE TO GET GOING. The harbor was first sighted in 1542 by a Spanish explorer, but nothing much happened until 1769 when famed Father Juniper Serra established the first mission in California at what is now Old Town, a few miles north of the bay. Then in 1867, Alonzo E. Horton, aged 54, came to San Diego and, miffed at the inconvenient distance to the nearest habitation, started a town next to the harbor. What is known these days as the Gaslamp Quarter—a vibrant hive of restaurants and nightclubs (but mostly restaurants) in the neighborhood nearest the waterfront Convention Center—was thronged with saloons, gambling halls and bordellos in the 19th century. Called the Stingaree, it was where Wyatt Earp and his wife Josie came somewhere between 1885 and 1887 to invest in real estate and saloons. (The shootout in Tombstone had taken place in the fall of 1881, in case you’re wondering). San Diego in the Earp days—a booming neighborhood.

By the 1950s, decay had set in, infesting the vicinity with porn shops, burlesque theaters, and massage parlors—a well-known and widely disparaged haven for sailors on shore leave from the nearby naval base. But in 1976, the city began reviving the area, preserving the old buildings and creating what is now a national historic district, alive and well. Among his numerous civic achievements, Alonzo Horton built a hotel, the Horton House, which stood where the U.S. Grant stands today. And it was in the U.S. Grant that the first Comic- Con was held in March 21, 1970: a mere one-day affair, it was staged in the hope of generating enough capital to fund a longer convention later. Those hopes were happily realized, and the second Comic-Con, officially dubbed the San Diego Golden State Comic-Con, was held August 1-3, 1970, 41 years ago. (For more about the founding of the Con and its founder, Shel Dorf, who died last fall, see Opus 251.) The U.S. Grant in those early years was not “the snazziest of venues,” as one of the early con committee members, Scott Shaw, says. And it didn’t become very snazzy until quite recently. In one of my earlier lives—the one as a convention manager—I visited the Grant in the late 1980s on a site inspection, and I remember the elevator ride up to the sales office on the top floor of the hotel. There were only about five of us in the elevator, but even with that modest weight, the thing couldn’t ascend the last couple floors; the hotel sales person got off and walked up the stairs so the elevator could take the rest of us, the visitors and potential buyers of convention facilities, up to the offices. Today, the U.S. Grant is the city’s Grande Olde Lady, expansively refurbished and expensively priced ($299/night for this year’s Con). And looming over the city like a whited sepulcher is the remnant of another storied Con site, crowned by its name in red cutout letters, El Cortez, once a hotel now permanent housing for the elderly. With its forty-first convening this year, the Con itself is on the cusp of becoming elderly, but it shows no signs of advancing decrepitude although its growth, by leaps and bounds in recent years thanks to the Hollywood invasion, has been stalled for three or four years by the capacity of the meeting site, the San Diego Convention Center (SDCC). For safety sake, the city’s fire marshal has dictated a cap of 125,000 attendees for the facility. And with only 500,000 square feet of exhibit space, the SDCC has also stymied the Con’s expansion in exhibit booth sales. I heard very little discussion about the future site of the Con, but it lurked, albeit silently, over the week. Two other cities, Anaheim and Los Angeles, are bidding for the Con, forcing San Diego into a more competitive posture. The Comic-Con, which is the city’s largest convention, represents a vast economic resource in these shaky times. In California, the San Diego Business Journal reported (July 26), 478 hotels were in default or foreclosure at the end of June; in San Diego county, 40 hotels are in default, and seven have been foreclosed (including one of the Con hosts, W Hotel, which was nonetheless still operating and charged $305 a night as part of the Con’s housing package). The Comic-Con represents a substantial life-line to the community. A study commissioned by the SDCC and recently completed estimates that the Con has an immediate economic impact on the city of $163,000. That includes hotel room rent and the accompanying tax revenues for the city, plus spending on souvenirs, transportation within the city, and meals at restaurants. But the direct of effect of an infusion into the city of $163,000 in “new money” (money not in the local economy before) is only part of the Con’s economic payoff. In the convention industry, the value of any such revenue multiplies four times: every one of those dollars is spent again and again, bolstering the local economy with each expenditure. Workers hired for the duration of the convention, for instance, earn money that they spend in local grocery stores and gas stations, money they wouldn’t otherwise have. This kind of spending goes on for weeks after a convention has left town. The ultimate result of the direct spending by Comic-Con attendees has an over-all economic clout of $625,000. Jim Durbin, president of the San Diego Hotel-Motel Association, says the Comic-Con has an impact upon the city’s hospitality industry that rivals a Super Bowl. Understandably, San Diego is eager to keep the cash-cow Con in the city, and it is doing what it can in three problem areas: transportation, availability and cost of hotel rooms, and exhibit space. The city’s bid for the Con for the years 2013 through 2015 includes an outright budget supplement of $100,000 to help defray the cost of shuttling attendees between hotels and the SDCC. The city will also double the number of hotel rooms from 7,000 to 14,000, and hotels have offered to “cap” room rates at $300/night. (The cap is meaningless unless it’s hitched to inflation. Only 6 of the 38 hotels on this year’s list charge as much as $300/night, so only 6 would be “frozen” at the cap’s rate. The rest of the hotels could, unless inhibited by an inflation factor, jump their rates immediately to $300/night and still be within the letter of the new agreement. But if the cap includes an inflation factor—no hotel can raise its 2010 rate by more than, say, 5 percent a year—then the rates are effectively capped.) The SDCC is also actively looking for financing to expand exhibit and meeting space. And not just for the Comic-Con: other large conventions (the Biotechnology Industry Organization, for instance, the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America, the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society and several medical meetings) have complained in recent years about the limit that the SDCC imposes upon their growth. According to the San Diego Business Journal (July 26), “the Convention Center can no longer accommodate key growth industries and shows in its 500,000 square feet of exhibit space.” Said Carol Wallace, the SDCC corporate president and CEO: “We needed to expand 10 years ago. Every year, we turn away an average of a year’s worth of business. Those are room nights [nights occupied at hotels] that could come to San Diego—and room revenues and room taxes that could go to the city.” Clearly, the city has every good reason to expand the SDCC quite apart from catering to comics geeks. And the mayor has been stumping for the expansion since 2007. The SDCC opened in 1989 with 250,000 square feet of exhibit space; the expansion, dubbed “Phase Two,” doubled the space when it was completed in 2001. “Phase Three,” now in the planning stages, will increase the space by a third, to 750,000 square feet—plus more meeting rooms and a big ballroom. Financing Phase Three may not be as much of a problem as it seems: Phase Two cost $216 million, which was bankrolled by the Port of San Diego ($90 million; the Port had paid for all of the original 1989 building) and by increasing hotel room tax by a penny. A pittance, but it adds up quickly. With a 30-month construction window, Phase Three’s completion date is anticipated for 2015, which would be the last year of the city’s proposed new contract with the Comic-Con (2013-15). That may be too late to prevent the Con from moving: it effectively prolongs the attendance limit for another 4 years, another 4 years of lost revenue. As of this writing (August 2), the Comic-Con management has made no decision about the Con’s future location. Although they expected to make an announcement before this year’s Con, discussion snarled, resulting in numerous modifications to the bids by the competing cities, and in the last analysis, the Con management elected to put aside further deliberation in order to concentrate on staging the 2010 Con. David Glanzer, Comic-Con’s director of marketing and public relations, thought they’d resume discussion after the 2010 Con and perhaps announce a decision in a week or so. By the time you read this, the announcement may have been made. My guess is that the Comic-Con will stay in San Diego. Quite apart from sentimental historical reasons that favor San Diego, neither of the other two cities under consideration can offer the kind of amenities one can find in the area immediately surrounding the SDCC, chiefly the Gaslamp Quarter with its numerous restaurants and nightclubs. “You’re not going to get that neighborhood feel in those other cities,” Durbin said. And I agree. There is no “neighborhood” in the vicinity of Los Angeles’ giant convention center; and the “neighborhood” in Anaheim is spread all around Disneyland. And I doubt that Anaheim will do much to match San Diego’s hotel room rates. The summer months in Anaheim are the year’s biggest attendance months for Disneyland with families arriving in vast quantity: why should hotels lower rates to attract the Comic-Con at a time when they are already running as full as they can and at the highest rates of the year? In my view, the only advantages Los Angeles and Anaheim offer over San Diego are the size of the convention facility and its proximity to the film industry, which, presumably, would result in more movies and more movie stars attending the Con. But as one wag put it: “Why shouldn’t the movie people schlep their stuff down to San Diego? Comics guys do.”

IF SAN DIEGO’S INTEREST IN THE CON is enough to secure its return in the years after 2012, the welcome mat spread through the city is an ample indiction of that interest. Throughout the downtown area and the tourist attractive Gaslamp Quarter the Con’s presence was heralded with banners hanging from streetlamps and posters in the windows of stores and restaurants—“Welcome to San Diego” they all trumpeted. And Hollywood got well into the same act. The sides of shuttle buses were covered with huge ads for Showtime tv series—“Weeds,” “Dexter,” “Nurse Jackie,” and “Californication”: “Our heroes have more fun” the sides of the buses proclaimed. And Showtime also hyped its heroes at a “anti-hero” panel on the Con program. Most spectacular of all, however, were the sides of three skyscraping hotels: all three had been converted to immense billboards by laminating onto their titanic exterior walls advertisements about new movies and tv series. A “Dateline” producer with whom I was walking one evening said the cost of erecting such vast promotions had to run into the “hundreds of thousands.”

That, however, indicates the status of the Con with Hollywood, not with the city of San Diego. But both are fanatic in their interest, in token of which, consider the plastic card room keys in all participating hotels: the keys issued for the week bore pictures publicizing movies and tv shows. Oh—and at the end of every day, a noisy small airplane flew over the Con site, towing a banner welcoming the Con. I left the city after four days believing that I had been bombarded with every advertising and promotional gimmick so far known to man and advertising agencies.

***** One session late Saturday afternoon was devoted to the Con’s founder, Shel Dorf. At the head table were many of the men, now quite a bit older, who had joined Shel in the early days and learned something about themselves and the way they might want to earn a living. Shel’s brother Michael was there and, after introducing the panel, he took a seat in the audience where he could hear and see better. Michael hopes to continue somewhat more formally the casual work Shel performed all those years, counseling and encouraging young people and pointing them in directions they might enjoy. Michael’s established the Shel Dorf Artist Fund, and on four nights after the Con’s daily schedule ended, an AfterCon commenced in a nearby gallery, where you could bid on artwork hanging on the wall, the proceeds all going into the Fund. And that’s how the Con went for me this year. See you there next year. *****

Lady Gaga. What—?!

*****

Here’s the Associated Press’s look at Charles Schulz' Peanuts legacy, by the numbers: Number of years Charles Schulz drew Peanuts: Nearly 50. Number of comic strips: 17,897. Number of newspapers Peanuts debuted in on Oct. 2, 1950: Seven. Price paid by United Feature Syndicate for Schulz' first month of strips: $90. Year Hallmark printed its first Peanuts greeting card: 1960. Number of Hallmark Peanuts cards sold: More than 2 billion. Peanuts first cover of Time magazine: 1965. Number

of readers by the strip's 25th anniversary: 90 million in 1,480 U.S. and 175

foreign papers. Number of languages the strip is printed in: 21 Year the Schulz family got a black-and-white dog that inspired Snoopy: 1934 (his name was Spike).

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted The

last month was, like most months lately, fraught with juicy opportunity for

editorial cartoonists. Much of the potential for comedy arises with the fumes

from the stewing of the Garroting Old Pachyderm, the extreme right wing

elements of which cannot, seemingly, avoid knocking over absurdities with every

elbow. The case of Shirley Sherrod’s firing, being a gross stupidity, was

perfect for editoonists, and they happily jumped in, as we see in our first

visual aid. In

our next slide, we have three more powerful images and a fourth so comedic that

I can’t resist it. Lester’s second cartoon I no more agree with than his first, but the comedy is delightful. I’m not sure, however, just how to interpret (“read”) Lester’s imagery. As is the case frequently when I encounter conservative editoons, the point of view is so often so far on the extreme right edge of reality that it’s fallen off altogether. First, Lester is saying the NAACP has accused the Teabaggers of being racist (which some of them are), which accusation is justified because the Teabaggers have merely called a person of color a colored person? So merely by saying something that is indisputably true one gets labeled a racist? And then having manufactured a sense of injury, the NAACP runs to the news media to weep and moan about how abused it feels? Well, I suppose. If the target here is the news media, I think Lester has a point. In

our last example, we depart somewhat from the usual assemblage of exemplars to

include Time’s recent cover depicting a beautiful 18-year-old Afghan

girl whose father, at the order of the Taliban, cut her nose off because she

fled an abusive husband and in-laws. The last cartoon on the page, one of Mike Twohy’s efforts for The New Yorker, reminds us that even the innocent gag cartoonist often produces a cartoon with a political edge.

A LITTLE LIGHT IN THE OTHERWISE GATHERING GLOAMING As many newspapers shed their staff editorial cartoonists in fits of fiscal retrenchment, one paper, at least, is considering a return to the rousing days of yesteryear. Rob Tornoe at Editor & Publisher reports that the 49,000-circulation Spartanburg Herald-Journal in South Carolina has offered a contract to Robert Ariail to do five cartoons a week in a relationship that could lead to a staff cartooning job. "They

already subscribe to my cartoons via United Feature and like my other South

Carolina clients, they get all my South Carolina cartoons as a bonus,"

Ariail said. "So this shows how much they value having a staff cartoonist,

particularly in this newspaper climate of dwindling cartoonist positions." Nevertheless,

Ariail feels lucky to get close to a full-time staff position again in the

financially pressed industry. "Editorial cartooning must be the hardest

job to be looking for in this economy," he said. "I think the Herald-Journal is showing a lot of faith in the future of newspapers and of editorial

cartooning."

Cartoonist Works in Oil to Convey His Anger about the BP Oil Spill "I kept staring at pictures of the spill," editoonist Steve Breen said about his inspiration, which struck in late May, as his anger and disgust toward BP and the Department of Interior increased. "Then, as a creative person who works with dark liquid all the time—in ink—something organically grew out of that. I play with dark liquid all the time, so I decided to use oil as my ink." Cartoons about the Gulf disaster inked with its very oil seemed somehow more potent than cartoons drawn with ordinary ink. The idea seemed so gimmicky that Breen, a two-time Pulitzer winner, didn’t tell his bosses at the San Diego Union-Tribune what he was up to: he bought his own plane ticket and took off for the Gulf. `"There were so many variables," Breen told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs (who supplied the phrase with the two-edged meaning for our headline). "I didn't know if I could even find a beach with the alleged tarballs before cleanup workers got there. Then I didn't know if I could transport the tarballs. Then, if I could get them back, I didn't even know if I could mix them so I could paint with them, or if the oil would show up all." After flying into New Orleans, Cavna writes, Breen drove several hours to Pensacola Beach. On July 3, he struck black gold. Just days earlier, Hurricane Alex had helped wash ashore more tarballs than entire schools of mixed-media artists could ever hope to gather. Then he had to navigate his way through airport security with this liquid contraband. He ziplocked two tupperware containers and packet them into his carry-on; for insurance, he sent one more container by U.S. Postal Service. Once home, the next step was to figure out how to use the oil. The

sun had dried out the oil, Breen said, “so it was a concentrated goo.” He

decided to mix in some gasoline. Cavna explained: Breen says the approach was

akin to painting with watercolor, which he's used to illustrate children's

books. Mixing fresh tarball with varying degrees of Unleaded, the artist was

able to create tints of rust and sepia, of cocoa and ocher. Strathmore vellum

board held the somewhat-sandy medium nicely, with minimal bleed. Working at his

studio at home rather than in the newsroom, Breen “painted” five cartoons in

which the oil makes his point; here are four of them. "I wanted to use minimal wording so the visuals would have maximum impact," Breen says. "I needed to find powerful images." Once artistically satisfied, he presented the cartoons to his Union-Tribune editors. “Here's what I did over my Fourth of July vacation,” he says he told Editor Jeff Light and opinion page Editor Bill Osborne. "They were immediately enthusiastic and supportive, which was gratifying. They said they would get me a full color page to run all of them." The five cartoons ran in Sunday's Union-Tribune, July 25. And within a couple days, a museum in Mobile, Ala., expressed interest in exhibiting the artworks, says Breen, noting that he might create more such cartoons: "I've still got plenty of tarball—maybe now that he's leaving, I could do a caricature of Tony Hayward all in tarball." As of the date of Cavna’s story (July 27), Breen hadn’t approached his editors for reimbursement for his trip to the Gulf. “For now,” Cavna reports, “he's just pleased with the creative results.” Said Breen: “As editorial cartoonists, the bigger the story, the more [we] want to do a cartoon about that topic. The greater the injustice, the greater the stupidity or greed or irresponsibility, those things really inspire us." So once he's done working with oils, where, Cavna asked, might he next find such liquid inspiration? "For an encore, I might do health-care cartoons using my own blood," says Breen, before waiting a beat. "That will be my last act."

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution If Shirley Sherrod’s was not a case of lynching by internet, it was terrifyingly close. We all know the story: a conservative blogger named Andrew Breitbart, who had enjoyed stunning success in putting ACORN out of business last year, performed yet another sleight with videotape, this time excerpting a portion of a Sherrod speech to show she was a racist in the exercise of her duties as a employee of the Department of Agriculture. Back in 1986, Sherrod, an African American, told how she had hesitated to come to the help of a white farmer. That was the substance of the clip. As Frank Rich explained in the New York Times, the excerpt fit right into the conservative agenda: “To portray whites as the victims of racist blacks has been a weapon of the right from the moment desegregation started to empower previously subjugated minorities in the 1960s. But its deployment has accelerated with the ascent of a black president.” Of course, the excerpt was so misleading as to be an outright lie. It didn’t mention, for instance, that Sherrod’s father had been killed by white men in 1965 and that an all-white grand jury refused to return an indictment. Despite this personal history, Sherrod learned during the case of the needy white farmer that “need” knows no race: poverty was the issue, not race. And she helped the farmer. The whole of her speech was a tale of self-discovery and redemption: it was a story about overcoming prejudice. But that didn’t fit into the conservative agenda, so it was handily ignored. But the real terror in the Sherrod case lies not in the inherent injustice done her when she was summarily fired without a hearing but in the complete and abject failure of American journalism to do what it is supposed to do: learn and report the facts. But few of the so-called news media took much notice of this colossal failure in its immediate aftermath: instead, gasbags everywhere launched into lengthy disquisitions about the disappearance of “post-racial” America, the heppy heppy land into which the election of Barack Obama had brought us. Really? How naive. What thinking person actually supposed that the election of Obama meant an end to racism in America? No one really believed that. But the punditry pretended that everyone had bought into this fairytale and that we were all terribly disappointed, now, by the revelation, through the Sherrod instance, that racism was not, after all, dead and gone. The pundits and know-it-alls were but performing their usual service of filling broadcast time with gaseous effusions—in this case, hot air that distracted from the real hideousness of the Sherrod case. Among the few who took notice of the most important facts was Jon Meacham at Newsweek, who said: “It was yet another object lesson in the perils of life in a hyperpartisan and hyperactive media climate, an ethos that encourages hyperbole and haste.” Yes, the Sherrod case told us that racism was not yet dead and that white prejudice has gone underground and become insidious and therefore even more dangerous than ever. And, yes, it will probably take a lot longer for us to overcome our racism than we would like to believe. But we would be vastly assisted in this endeavor by a news media that attended to its basic, most fundamental, function: to ascertain the facts and report them. The Sherrod case was a exemplary instance of how not to do journalism. Almost no one—certainly not Fox News, which seized upon the story as soon as Breitbart presented it—checked the facts. No one, apparently, vetted the video before airing it. Robert Thompson, a Syracuse University expert on tv, compared the government officials who turned against Sherrod in a panic and demanded her resignation to “the kind of people who believe everything they see on the Internet. The story here is the utter lack of due diligence by these officials. They really walked right into it.” Donna Brazile, a Democratic stategist and an African American, blamed “this rapid news cycle, the White House, the administration, the NAACP, the conservative noise machine, the liberal noise machine. We’ve got to learn to calm the waters.” Meacham added: “Technology is not totally to blame, but it is now a necessary and sufficient condition for the triumph of the extreme and the trivial.” At bottom, however, it was a nearly complete abdication of journalistic integrity. As Rich said: “This wasn’t a failure of due diligence: there was no diligence.” Sherrod has said she intends to sue Breitbart, and perhaps that is a good start at stemming the flow of half-truth and no-truth-at-all that infects the news media, particularly the 24/7 news cycle of cable tv, which sets the pace for all other news media. Breitbart’s procedure in the Sherrod situation makes us wonder just how accurate and truthful he was in helping to perpetrate the episode of the video of ACORN officials assisting a pimp in finding a suitable place to set up shop. Did Breitbart overlook and suppress inconvenient facts there, too? My guess is he did, and his success taught him that he could do it again with impunity. And, to the everlasting shame of the so-called journalists in the land, he almost got away with it Unhappily, the Sherrod case is not the only time lately that we’ve been offered sensation rather than fact.

THE GULF OF MEXICO, it turns out, has not be completely destroyed by BP oil. Now that the leaky well has been, more-or-less, plugged, the voices of soberer experts on the matter have at last surfaced. For well over three months, the self-proclaimed news media have assaulted us—daily on network news programs—with the most dire interpretations of the environmental impact of the oil spill. And while there has undoubtedly been great damage done, it is not, apparently, quite as devastating or as permanent as we’ve been led to believe. “The impacts have been much, much less than everyone feared,” said a geochemist quoted in Time (August 9). Others concurred. “Louisiana State University coastal scientist Eugene Turner, a perennial critic of the oil industry, believes the spill will destroy fewer marshes than the airboats deployed to clean it up will. Coastal scientist Paul Kemp, a former LSU professor who is now a National Audubon Society vice-president, compares the additional impact of the spill on the vanishing marshes to ‘a sunburn on a cancer patient.’ Marine scientist Ivor van Heerden, another former LSU prof, who’s working for a spill-response contractor, says, ‘There’s just no data to suggest this is an environmental disaster.’” Yes, we’ve seen lots of dead birds, but of the nearly 3,000 collected so far, fewer than half of them are visibly oiled; the infamous Exxon Valdez spill may have killed as many as 435,000. Other recent cases of oil spills have not all be disasters, reported The Week magazine (July 23). The Exxon Valdez dumped an estimated 11 million gallons of heavy crude into Alaska’s Prince William Sound in 1989. In 1979, when a rig over the Ixtoc 1 well in Mexico’s Bay of Campeche exploded and sank, 140 million gallons of oil poured into the Gulf over the next 10 months. But when Saddam Hussein’s troops retreating from Kuwait sabotaged oil wells, tankers and storage facilities in 1991, 460 million gallons spilled into the Persian Gulf. By comparison, the BP spill is estimated at 260 million gallons by early August, still less that the Kuwaiti dump. And yet, all is not lost. At the sites of both Ixtoc 1 and the Persian Gulf, fish and wildlife populations returned to pre-spill levels within a couple of years after declining as much as 80 percent. “You look around and it’s like the spill never happened,” said marine biologist Wes Tunnell. The environment is amazingly resilient. Prince William Sound has recovered far less probably because it’s cold up there, and environments generally adjust slower in colder areas. But my point remains: in pursuit of a sensational story, the news media are willing to ignore facts that are likely to diminish the sensation. As Michael Grunwald put it in Time: “Anti-oil politicians, anti-Obama politicians and underfunded green groups all have incentives to accentuate the negative. So do the media because disasters are good for business: those oil-soaked pelicans you saw on tv (and on the cover of Time) were a lot more compelling than the healthy ones I saw on a protective boom in Bay Jimmy.” Sensational stories increase viewership/readership; increased viewership/readership improves circulation and advertising revenue. So sensational stories trump journalism every time.

IN THE SAME VEIN, we’ve been hearing lately a lot of drum banging about how evil the monstrous deficit is and how we should throw the Democrats out because they’ve added so much to the debt. This is the party line of the Grabby Old Pachyderm; this is how the GOP hopes to regain control of the House and the Senate. But in reporting this GOP pitch day after day, the so-called liberal news media has neglected to point out (1) how little concern the Republicans showed for a mounting deficit when funding GeeDubya’s wars (exactly the political posture that has brought us to this pass in the first place) and (2) the oft-touted wisdom of one of the GOP’s most revered leaders—Dick Cheney, who famously said, Ronald Reagan proved that deficits don’t matter. The news media may not be lying outright like Breitbart, but by neglecting to mention exculpatory facts, they lie by default.

ADRIFT AS WE ARE IN THIS SLOUGH OF MALFEASANCE, it is highly gratifying to have at least one major news organization performing, and performing well, the essential function of journalism in a democracy. After two years of investigation, Dana Priest and William Arkin of the Washington Post launched a three-part report on July 19 about a sprawling “top secret America” in which hundreds—thousands!—of spy operations churned out more reports than can be processed and security has been given over entirely to private contractors over which the government has little authority. “The top secret world the government created in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist with it or exactly how many agencies do the same work,” the reporters began their report. In The New Yorker, the wry and perceptive Hendrik Hertzberg called “top secret America” a “bureaucratic behemoth substantially privatized but awash in public money”—“an alternative geography of the United States, hidden from public view [because it is secret] and wholly lacking in thorough oversight [for the same reason—not to mention the very vastness of the enterprise that renders making sense of it impossible].” One of the most alarming aspects of the situation Priest and Arkin describe is the extent to which all of it is being run by private contractors, profit-making businesses. “The concern this raises is ‘whether the federal workforce includes too many people obligated to shareholders rather than the public interest—and whether the government is still in control of its most sensitive activities.’” I think pretty obviously the government has long ago lost even the most tenuous grip on what is being done in our name. And when I think of the rampaging bull that was Blackwater in Iraq, I shudder to think what other outrages to common humanity and decency have been committed that we are blames for but know not of. The Washington Post report is sterling journalism, journalism at its best—the kind of journalism newspapers used to be wealthy enough to mount and execute. Alas, it’s the kind of journalism that few newspapers can any longer afford to practice. And we are much the poorer for it. No one in a position to know has yet denied any substantial part of the report. No one is talking about it on cable-tv news. On tv news, all the talk is about hundreds of thousands of low-level “intelligence” (“low level” means, essentially, not intelligence) reports that have been leaked and posted on the Internet. Because some of the reports may contains names of Afghans who’ve helped us or reveal tactical methods of the armed forces in Afghanistan, this “news” is much juicier meat for the pundits to get their teeth into. And so they gnaw away, masticating information into entertainment while no one talks about how to reclaim our government from private contractors.