|

||||||||||||

Opus 260 (April 23, 2010). The first Pultizer for editorial cartooning by animation alone goes to a pioneer in the genre, Mark Fiore. We also share an exhaustive examination of the implications of iPad for comics, nominations for Reubens division awards, editooning the Pope, the virtues (and not) of the “Kick-Ass” movie, the first annual Fips Award for bias, corruption and outright opinionation in political cartooning, and we define and extol teabaggers and celebrate Pickles’ twentieth, concluding with mini-reviews of: The Knight Life reprint, Jerry Robinson biog, his revised Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art, Schulz’ s Life with Charlie Brown, a gorgeous Jaime Hernandez volume from Abrams, plus full-blown reviews of the Why I Killed Peter graphic novel, and funnybooks Incorruptible, God Complex, Supergod, Shuddertown, New Ultimates, Girl Comics and Green Hornet; and obits for Dick Giordano and Herny Scapelli. Without further adieu, here’s what’s here, in order, by department: Apologetic Correction NOUS R US Animation Editoonist Wins Pulitzer Comics at the Movies (Kick-Ass mostly) Editoonist Staff of 30 Years Laid Off Tracy in Bronze iPad and the Future of Comics NCS Nominees for Reubens Division Awards EDITOONERY The Pope and the Press The First Annual Fips Award Teabaggers Defined THE FROTH ESTATE The Future is Mobile HAPPY BIRTHDAY Pickles Is Twenty BOOK MARQUEE The Knight Life Jerry Robinson Bio Revised and Up-dated Illustrated History of Comics (Robinson’) Charles Schulz Life with Charlie Brown Jaime Hernandez from Abrams GRAPHIC NOVILZ Why I Killed Peter FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Incorruptible God Complex Supergod Shuddertown New Ultimates Girl Comics Green Hornet PASSIN’ THROUGH Dick Giordano Henry Scarpelli And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— APOLOGETIC CORRECTION. In Opus 259 during my review of IDW’s Bringing Up Father: From Sea to Shining Sea, I questioned Bruce Canwell’s prefatory assertion about a legal contest following creator George McManus’ death in 1954. What, I asked, would McManus’ long-time assistant Zeke Zekley have sued for? I was thinking about Zeke not inheriting the strip, which everyone expected he would. Indeed, that was the context in which Canwell made his assertion. In contesting McManus’ will, however, Zeke claimed his old boss left him more money. That, not stewardship of the strip, was what Zeke went to court over. IDW’s Dean Mullaney sent me newspaper clippings covering the legal maneuverings that ensued, and I’m happy to have documentary evidence that demolishes my doubt. Herewith, apologies to Bruce and to Dean: I should’ve known better. NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits PULITZER GOES TO ANIMATION For the first time, the Pulitzer committee on editorial cartooning, not usually the most forward-looking deliberative body on the planet, awarded the prize to a cartoonist whose work is all animated, not a traditionally static image in sight. Numerous cartooning kibitzers believed this day was coming, but few thought it would arrive so soon. Mark Fiore self-syndicates his animations to the websites of NPR, Mother Jones and Slate as well as SFGate.com, where, saith the Pulitzers, “his wit, extensive research and ability to distill complex issues set a high standard for an emerging form of commentary.” It was a most appropriate accolade: Fiore is not only the first animating editoonist to win, he was among the first—if not, in fact, The First—editoonist to go into animating his cartoons as a full-time enterprise, making the cartoons and marketing them, too, via the Web. His cartoons are not just moving pictures: they are full-bore productions with music as well as dialogue and, sometimes, songs. And he manages to preserve from his static cartoons a limber line that waxes and wanes and even bunches up at corners occasionally, creating a nifty visual hook. He is a genuine pioneer, whose example has inspired an entire profession. (And Fiore has the additional albeit dubious distinction of having roomed with me twice at the annual AAEC Convention. Congratulations Mark!) In 2007, the Pulitzer went to Newsdays’s Walt Handelsman who was the first winner whose work included animations as well as motionless editoons, and the Pulitzers revised their criteria to embrace the new medium, but, until this year, an editorial cartoonist’s portfolio had to enclose submissions of traditional, static cartoons even if it also contained animated cartoons. Fiore is the first to win for cartoons that are solely animations; and his portfolio comprised no immobile cartoons.. In addition to pride and satisfaction at having his ground-breaking work recognized by the profession’s most prestigious award, Fiore, who lives on the fringes of San Francisco and habitually dresses like a beachcomber, must feel just a little avenged. In 2001, after just nine months at a job he’d aspired to all his life—staff editorial cartoonist on a daily newspaper—Fiore lost his position at the San Jose Mercury. "I was pretty miserable down there," he told ComicRiffs’ Michael Cavna."It was a bad time to be there. Either I left them or they left me—I still don't know what happened." What happened was mostly the financial pinch of a down-turning economy: the dot-com bubble had just burst, and the Mercury News, owned by Knight Ridder, had been directed to cut staff. The paper’s publisher resigned in protest, saying cuts of the specified dimension would sabotage the paper’s ability to report the news. After he left, the cuts were made. Suddenly unemployed, Fiore made “a fateful decision”: he decided to try animation. He freelanced for games and other experimental ventures, and over the next two years, working with a traditionally trained animator, Fiore learned animation and began selling his work to the burgeoning animation market on the Web. “I'd done a little animation, some character design,” he told Cavna. “I knew how to break things down for animation. But my early animations were rudimentary.” His tutor taught him a lot. Fiore still uses Flash, he said, adding, with a grin, that “the stuff that I’m doing is glorified flip-book.” Yeah, well—maybe: flip-book with orchestral production values and pungent songs. Witty lyrics and other fiendish touches. When he animated Dick Cheney one

time, Fiore incorporated a nuanced signal. “Dick Cheney was always a great gift," he

said. "He was my graduation speaker [at Colorado College in 1991], and he was really

fun to caricature. So I did a subtle thing in the animation. If you watch his eyes, they

blink more like a reptile's—membrane covers the eyes before they shut." Fiore identifies his politics as left-of-center but says: "I'm more than happy to go after the left. I just did a cartoon that got a lot of hate mail and people unsubscribed from my newsletter. I was going after Mexican druglords but people thought I was anti-marijuana. I was trying to walk the line between 'Say no to drugs' and 'Grow your own!' " Fiore doesn’t see animation as the only future for political cartooning. "I think it's A future," Fiore says. "I hope it's not THE future. I hope there are still traditionally drawn print cartoons by staff cartoonists. ... Judging by what's happened, though, that won't be necessarily the only way." Some of the inky-fingered brethren believe Pulitzer should create a new category

for animated cartoons to distinguish them from print cartoons because each of the

forms requires different skills. But Fiore disagrees, seeing editorial cartooning as

essentially an attitudinal endeavor, not a set of job skills. "It's going to get sillier and

sillier if you divide it up," he said. "A political cartoon can take many forms. ... Should we

segregate multi-panel and single-panel cartoons? And color from black-and-white? And

lithography from traditional letterpress? We might as well lump them all together." (More

on this disputation in Opus 221.) Writing to his colleagues in the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, Fiore said: “This award is really a testament to the strength and support the AAEC and our merry band of cartoonists affords a solo cartoonist like me. I can definitely say that without all of you I would have stopped cartooning early in my career. Together we're so much stronger. The friendship, support (and even competition) that is all a part of our organization is vital to keeping the art form alive and growing. I've always thought of us as co-workers who happen to live in different towns, but it's really more like we're a big family. (Okay, with an uncle or two who really, really likes beer.)” Nicely done, Mark. Talking to Justin Berton at SFGate, Fiore wondered: “What do you do when you win a Pulitzer? Do you work hard or do a big blowout and take the week off?” He said he’d probably spend the $10,000 Prize money remodeling the bathroom

of the Fairfax home he and his wife, Chelsea Donovan, bought in December. Fiore had

lived in San Francisco for the preceding 15 years. **** FOOTNIT In one of those delicious strokes of irony, in the wake of Pulitzer’s announcement about Fiore’s win, it emerged shortly, thanks to a Nieman Journalism Lab blog, that last December Apple wouldn’t let the cartoonist’s iPhone app into the App Store because it “contains content that ridicules public figures.” As soon as that story surfaced, Steve Jobs said: “This was a mistake that’s being fixed.” And, sure enough, Apple has asked Fiore to resubmit his app, and it’s been accepted. Said Fiore: “I feel kind of guilty: I’m getting preferential treatment because I got the Pulitzer.” Still, opined DailyCartoonist’s Alan Gardner, “If I’m reading between the lines correctly, Apple wants the app in the store because of the bad press about it blocking a Pulitzer-winning cartoonist, but it may hold its ground on the content—in essence, censoring Mark’s work.” Fiore summed up: “I think the key passage in the Apple developer agreement that made things impossible was something like ‘ridicules public figures,’ which is, um, like, kinda what we all make our living doing. Methinks that may change thanks to the confluence of media over this crazy week. (Pulitzer 6 minutes of fame turned into an additional 6 iPhone app minutes.) Apple has been in contact with me and coincidentally encouraged me to resubmit the app, then call them directly. (My developer/programmer said that is unheard of, like having God's direct line.) I hope this changes their stupid policy, you shouldn't have to fall into a media campaign or win an award to get satire onto an app.” ***** At his DailyCartoonist blog, Alan Gardner reported that “Mark Fiore wasn’t the only cartoonist that took home a Pulitzer Prize this week. Matt Richtel, who pens the Rudy Park comic strip under the name Theron Heir, took home a Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles on distracted driving in the New York Times.” So much for frivolity. ***** In a sort of backhanded testimony to the potent status of editorial cartoons, the Denver Post, my local paper, has logged only six Pulitzers in its career (the sixth, this year), and two of the six were won by editorial cartoonists: Paul Conrad in 1964 (just as he was leaving for the Los Angeles Times) and Pat Oliphant in 1967 for work in 1966, the year after he arrived at the Post from his native Australia. MORE AWARDS Editoonist Steve Breen of the San Diego Union-Tribune won the 2010 John Fischetti

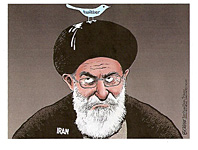

Editorial Cartoon Competition, an annual contest created by Columbia College Chicago

in 1980 in honor of John Fischetti, a Pulitzer-winning cartoonist for Chicago papers.

Among other achievements, Fischetti was the first U.S. editoonist to begin drawing his

cartoons in the horizontal European manner. Breen’s entry for the Fischetti Award

captures the citizen backlash against Iran’s government trying to squash Internet

communications documenting public uprisings last year. The cartoon features an image

of the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei with the Twitter bird mascot perched atop his head,

pooping on his turban. A CARTOONING WEEKEND AT THE MOVIES “Kick-Ass,” the movie based on the comic book series by Mark Millar and John Romita, Jr., opened April 16, and it virtually tied with another cartoon feature, the animated “How to Train Your Dragon,” in box office revenue—both roughly $20 million. For “Kick-Ass,” that’s $5-10 million shy of the amount predicted by wise-guy box office analysts. Millar joined the analysts in the weeks before the movie’s release: “This is a movie about comic fans, made by comic fans.” Just what we need: another niche flick for a neurotic niche. The so-called hero of the funnybook and the motion picture is a teenager who, enamored of superheroes, dresses up like his idols, tries to fight crime, and gets his tuckus trounced. The comic book, according to Entertainment Weekly (April 9), outsold Spider-Man during its 8-issue run, 2008-2010. A preview at last summer’s Sandy Eggo Comic-Con earned a standing ovation and has generated “the kind of buzz that any mega-budget film would envy.” In addition to “a uniquely self-aware blend of comic action and realistic gore,” the movie brims with foul language of the kind that the thirteen-year-old actress who utters it would get “grounded forever” if she used it in real life, she says. Playing her father in the movie is Nicolas Cage, a man so wrapped up in four-color fantasy that he named his son Kal-El, Superman’s birth name. Director Matthew Vaughn says the burgeoning popularity of “Kick-Ass” derives from an increasingly jaded audience: “Superhero movies are getting too generic,” he says. “Where’s the one that kids can really relate to? For me, that’s ‘Kick-Ass.’” Early tracking reports, saith EW, “show the movie playing as well with women as with men—a rarity in the male-driven world of comic book pics.” But perhaps not all that surprising since the movie ridicules the superhero fixation among the males. And there are more movies of this breed just down the road, “a coming wave of snarky, self-aware comic-nerd movies about real-dude superheroes”—“Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” (August) and “The Green Hornet” (December). As the “Kick-Ass” movie headed toward its April 16th debut, it appeared that in spite of its edgy “hard R” content, it was getting mostly positive reviews with a 74% positive rating on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes. But don’t count among the film’s admirers the dean of American movie reviewers, Roger Ebert, the critic who championed the work of Russ Meyer and countless other B movie maestros who shocked mainstream critics with their savage satires. Although Ebert did enjoy the film’s early scenes, praised the work of Aaron Johnson and Chloe Moretz, and even acknowledged that the film was indeed a satire, he labeled the movie as “morally reprehensible.” Ebert’s attack on the film, which may have some element of truth to it but is ultimately unfair to the filmmakers, is summed up in this passage: “I know, I know. This is a satire. But a satire of what? The movie's rated R, which means in this case that it's doubly attractive to anyone under 17. I'm not too worried about 16-year-olds here. I'm thinking of 6-year-olds.” At the Denver Post, movie critic Lisa Kennedy was, like Ebert, not amused: “Just because ‘Kick-Ass’ has a winning 11-year-old girl as one of its most unforgettable characters doesn’t mean Vaughn’s crazed ride of a flick is for kids. It so isn’t. It’s potty-mouthed and dementedly violent in the way that films based on comics so often are. R-rated, the movie is best for adults whose inner teen still aches to right wrongs but doesn’t have the skill set to wreak havoc on the bad guys.” Sounds like she’s been reading Ebert. At Time magazine, however, Richard Corliss was thrilled to his cultural/philosophical/critical core: “[The film] could have ended in a big, ugly blood puddle. Instead it soars, jet-propelled, on its central idea of matching a superhero’s exploits with the grinding reality of urban teen life and on the aerodynamic smoothness of the film’s style. To apotheosize the cliches of the genre while subverting them is a neat trick, but the ‘Kick-Ass’ cadre pulls it off. This is a violent R-rated drama that comments cogently on the impulses—noble, venal or twisted—that lead people to help or hurt others. ‘Kick-Ass’ kicks beaucoup d’ass, in some of the dandiest, most punishing stunt work this side of Hong Kong, but it forces the grown-ups in the audience to acknowledge that the action is as troubling as it is gorgeous. ... The result is a work that spills out of itself to raise issues about all superhero characters, all action pictures. Millar isn’t boasting when he writes in the making-of book that ‘Kick-Ass’ could ‘redefine superhero movies in the same way “Pulp Fiction”redefined crime movies.” Just what we need—another redefinition that redefines the newly defined. Oh, where will it all end? ***** From Jeffrey Long at the Telegram & Gazette Reviewer (quoted in italics): Innovative movie animation can catapult into fantasy ("Avatar"), sting with social criticism ("Waltz with Bashir"), or, as with "Sita Sings the Blues," delightfully enliven an ancient folktale from halfway around the world. This quirky, vibrant film has won awards at more than two dozen film festivals and has spawned a mushrooming cult following, both online and at cinemas. Nina Paley, whose creative talents outnumber Vishnu's arms, drew, wrote, and produced nearly every aspect of this feature-length cartoon, which is an imaginative retelling of the epic Hindu love story known as the Ramayana. With its tagline "The Greatest Break-Up Story Ever Told," this free-wheeling adaptation focuses upon the fortunes and misfortunes of the goddess Sita, whose patience and virtue face severe tests in the face of the wrongful treatment accorded her by her husband, Lord Rama. Paley tweaks the traditional structure of the "Ramayana" narrative with entertaining cross-cultural devices. She has morphed the story into a bluesy musical that incorporates several soulful jazz tunes sung by the noted 1920s performer Annette Hanshaw. Poignant and lilting jazz strains thus punctuate the story. Paley has been a fixture in the alternative press for years and tried, earlier in this decade, to get syndicated with a comic strip about a lusting and loving young couple, The Hots, written by Stephen Hersh; but, alas, to no avail. It ran only about a year in the public prints although it continues to lurk in the alternative venues. So it’s a delight to see her achieve a measure of success and acclaim with “Sita Sings the Blues.” You can watch the film at sitasingstheblues.com—for free; although a donation would be nice. ***** Captain America, the most iconic of the Marvel Universe’s superheroes, has yet to make it to the big screen, but plans are afoot to get him up there for a summer 2011 release, reported Nicole Sperling in Entertainment Weekly (March 26). In the planned adventure, Cap will be in World War II London battling his arch nemesis of that period, the Red Skull. The search for the right actor to play the part was complicated by part two of the plan—an all-star Avengers movie for the next summer, 2012, in which the same actor will impersonate Captain America while Robert Downey Jr. does Iron Man, Samuel L. Jackson does Nick Fury, and Chris Hemsworth does Thor. A long list of contenders for Cap’s role once included Ryan Phillippe, Chris Evans, Mike Vogel, Channing Tatum and, the only non-American, Romanian-born Sebastian Stan—all, except Phillippe (who is 35), “hunky twenty-somethings.” Not everyone was happy with this line-up. Alex Ross, who painted Captain America in the upscale funnybook version, said he’s aggravated to hear the names: “We’ve been saying for years, if you don’t sign Jon Hamm to play this part, you’re crazy. Captain America is supposed to be patriarch of the Marvel Universe. To get a guy in his early to mid-20s is only thinking about where the character began, not what he ultimately needs to become.” A young Apollo might be fine for WWII-era antics, but as the leader of the Avengers, Cap needs gravitas—and a few more years. At last report, Chris Evans got the nod. Probably won’t make Ross happy. ROUNDING UP THE STRAYS The Straits Times reported April 2 that a Japanese author and son of a Yakuza gangster sued police in the Fukuoka prefecture for asking stores to take underworld comics and magazines off their shelves. “Crime writer Manabu Miyazaki argued that police were suppressing free speech by asking stores not to sell manga comic books and magazines that describe the Japanese crime syndicates.” The police intended to enforce an ordinance aimed at curtailing the influence of the yakuza, whose organizations are not banned under Japanese law and whose exploits are often the subject of manga comics and fan magazines. The police list of the verboten included a comic book based on a Miyazaki novel about the life of a yakuza man, said the author, who demanded 5.5 million yen ($82,393) in damages from the regional government. Angelina Jolie’s tattooed back is the subject of the cover of the April 23 issue of Entertainment Weekly, and Ashley Dupre’s front, chiefly her photo-shopped boobs, is the focus of the May issue of Playboy, maintaining, still, its diminished page count (this issue, a mere 130 pages). The photo spread of the call girl who brought down the governor of New York and has, subsequently—and in direct consequence of her sensationally revealed liaison with Eliot Spitzer—become the New York Post’s columnist advising on love and sex, shows a surprisingly pretty, fit and pleasingly voluptuous young woman. Why would a young woman as toothsome as this go into the whoring industry? An article by Christopher Napolitano discloses all, beginning with this bon mot: “In person her skin shines like a toffee treat waiting to be unwrapped and savored.” Oh, yeah. We saw this one coming. As the folks at ComicConnect predicted, the copy of Action Comics No. 1 they offered at auction at the end of March broke the record set in

February by Metropolis Collectibles’s selling another copy of the same comic for $1

million: ComicConnect’s copy, graded higher than Metropolis’s copy, sold for $1.5

million. According to Jake Coyle at Associated Press, only about 100 copies of Action

Comics No. 1 are believed to exist, and only a handful in good condition. The issue just

sold had been preserved through happy oversight: it had been tucked inside an old

movie magazine for years before being discovered. Denver is a hotbed of medical marijuana machinations. The state legislature is struggling to find a way to regulate an industry that it set loose in earlier spasm of law-making, mj devotees are storming the state’s borders, and in Nederland, a notable hippie refuge a few miles into the mountains west of Boulder (the nation’s “happiest town”), they’re contemplating holding a maryjane festival. Meanwhile, Denverites Trey Parker and Matt Stone, creators of tv’s “South Park,” devoted the March 31st episode of the show to the issue. The show’s Facebook page tells us that “Randy is first in line to get his medical marijuana, but is turned away when a doctor finds nothing wrong with him. That begins his quest to find a medical excuse to smoke marijuana.” Meanwhile, Parker and Stone have written a musical comedy, “The Book of Mormon,” which is slated to open on Broadway in New York next March. Songs about multiple wives, no doubt, will abound. TRACY’S JAW IN BRONZE As If We Didn’t Know All These Years At 1 p.m. on April 11, a nine-foot, one-ton bronze likeness of Chester Gould’s iconic Dick Tracy was unveiled on the Riverwalk at the Naperville, Illinois. The idea for the sculpture was conceived by Naperville Century Walk Corporation president W. Brand Bobosky and cartoonist Dick Locher, who drew the strip for more than 30 years and is its current writer. Locher, a 40-year resident of Naperville, served as Gould’s assistant for several years, and when he sculpted a Tracy maquette and showed it to Bobosky, the latter thought it would make a beautiful life-size statue, joining the more than 30 public art pieces the Naperville organization has installed in the last 15 years. Locher’s concept was then turned over to Wisconsin sculptor Don Reed who transformed the maquette into the larger-than-life sculpture. Reed was intrigued with the challenge of capturing the structure of Tracy’s angular face, the flow of his hallmark trench coat and the sense of energy and motion Locher conveys of the detective in the strip. Reed, quoted in a press release from Tribune Media Services, the syndicate that distributes Dick Tracy, said that “thinking of the character as fully round, while creating strong lines and paying close attention to detail were essential to accurately depicting Tracy’s likeness.” Tracy in three dimensions, complete with the swirling yellow trench coat, is eye-catching for more than its larger-than-life dimensions, wrote Hillary Gavan in the Beloit Daily News, Reed’s hometown newspaper. “In line with Tracy's vintage comic strip origins, the bronze likeness of the 20th century crimestopper is rendered in full color through the use of a chemical technique called ‘patining’ that dates to Renaissance times.” She goes on, quoting Reed: "To me, Dick Tracy was the ultimate crimestopper who stood up for the public—someone who had a strong sense of values and who projected safety and security," Reed said. "My goal has been to bring that personality to life and convey a positive impression to viewers." A sculptor for more than 30 years, Reed is also a third-generation foundryman who combines state-of-the-art technology with Old World techniques. The accompanying photographs were taken in Reed’s studio before the sculpture was moved to Naperville.

Super-size Convention Centers Wage Comic Book-like Combat for Comic-Con Anaheim and San Diego have moved the contending for Comic-Con International into the digital ether: each city has a Facebook page touting its attributes as the future home of the 126,000-attendee pop culture event come 2013, the year after the Con’s current contract with the San Diego Convention Center expires. Anaheim’s page, says Lori Weisberg at the San Diego Union-Tribune, is entitled: “Bring Comic-Con International to Anaheim”; San Diego’s says "Keep Comic-Con in San Diego” and reportedly has four times the number of fans Anaheim has. Los Angeles, a recent entrant in the competition, is pondering whether to launch a page of its own. "Facebook gets the word out to a broad group of Comic-Con members, and if there's a groundswell of why-not-try-Anaheim, that will influence the decision-makers," said Charles Ahlers, president of the Anaheim/Orange County Visitor & Convention Bureau. "This is a grass-roots communications plan, and the fans ultimately will direct them where they want to be." The Con fills the San Diego Convention Center, and attendance has been capped at 126,000; in order to grow larger, the Con needs the roomier venues offered by either Anaheim or Los Angeles, both of which are also closer to the Hollywood industry that has lately swarmed into the 4-day event. All three cities have submitted formal proposals seeking to host Comic-Con for 2013 and beyond. Said Weisberg, citing an interview with Comic-Con spokesman David Glanzer: “There's hardly an argument Comic-Con organizers haven't heard when it comes to whether the event should stay or go. Ultimately, weightier issues like convention space and hotel costs, not Facebook missives, will win the day, Glanzer said, adding that he does not have a firm timetable for when a decision will be made. ‘We are in a unique situation that I don't ever remember us being in: people vying for our attention,’ he said. ‘It's like having several suitors asking you to the prom, but we have to make the best choice that we feel is most appropriate regardless of peer pressure.’” Warping in from the experience of one of my former lives as a convention manager (for almost 30 years), I hope Glanzer is canny enough to turn the competition to the Con’s advantage. It’s very like an auction: where there is more than one bidder for a convention, the convention’s management (the auctioneer) can play one against the other—in this case, forcing the cities to make more and more concessions in order to secure the business. Rental of the meeting and exhibit facilities should be slashed, for example—reasonably easy to arrange since the convention centers are single-entity municipal businesses. But hotel room rates should also drop precipitously. San Diego hoteliers have reportedly agreed that no hotel room will cost more than $300 a night. What—$300 a night?! That’s outrageous. If the hotels in San Diego really want the business, they should guarantee a much lower room rate. And to protect against future inflation, hotel room rates should be guaranteed in terms of a discount (say, 40-50% off “most available rate” or some similar easily ascertained benchmark) rather than a dollar amount. ***** Dave Astor, who, until Editor & Publisher suffered drastic staff shrinkage a year ago, reported syndicate news about comics and editorial cartooning for the historic trade magazine, continued his writing career with a topical humor column for his hometown paper in New Jersey, the weekly Montclair Times. And now, just about a year later, Astor has been recognized by the New Jersey Press Association, which awarded Astor’s column both first and second place for its category in the NJPA’s annual contest. “Yes,” Astor said when I asked him, “the two awards were for two different columns. No prize money, unfortunately. I'm paid for the column, but very modestly. The feature can be seen here at http://www.northjersey.com/news/opinions/montclairvoyant/ It's on the Web site for the Montclair Times' parent company.” ***** Humor Times, a monthly tabloid that publishes mostly insightful and deliciously acerbic editorial cartoons but also a couple of humor/political columns (Will Durst, Jim Hightower), celebrated its 19th anniversary with its April issue—“with more pages and extra color.” Subscriptions, well worth the price, are $18.95 for twelve issues: P.O. Box 162429, Sacramento, CA 95816. Comics Revue, Rick Norwood’s durable monthly magazine that reprints classic comic strips, now up to No. 288, underwent a spectacular format change a few months ago: no longer saddle-stitched, it is now square-spined, and Sunday strips are in color. The usual line-up is: Tarzan (Bob Lubbers and Dick van Buren) plus Russ Manning’s, Flash Gordon (Harry Harrison and Dan Barry) and Mac Raboy’s, Buz Sawyer, Phantom (Lee Falk and Wilson McCoy and, later, Ray Moore’s art), Secret Agent Corrigan, Rick O’Shay, Alley Oop, Mandrake the Magician (Falk and Phil Davis), Little Orphan Annie, Gasoline Alley (Dick Moores), Steve Canyon, Krazy Kat (dailies from the 1930s), Modesty Blaise, Casey Ruggles, and Sir Bagby. Each issue is a “double-issue” these days, and Norwood runs a complete story for a couple of the serial strips in every issue. Subscriptions are a mere $59/year from Manuscript Press, P.O. Box 336, Mountain Home, TN 37684. In DC and Industrywide: WILL iPAD SAVE COMICS AND KILL PRINT? By Michael Rhode [April 6, 2010] For print media, the potential impact of the iPad has loomed for months—even if its implications are unclear. That’s still true three days after its much-heralded landing. On Saturday, Apple reportedly sold 700,000 units of the new device. For comic books, the iPad promises a new revenue stream and a challenge to print sellers. For strips, the impact may be more ambiguous. I checked in with some local creators and retailers to get their opinions. Local editorial cartoonists see both sides. The Washington Post’s Ann Telnaes doesn’t have an iPhone and isn’t planning to do anything special for the iPad, even though she creates regular animated cartoons for the Post’s Web site. The same goes for Politico’s Matt Wuerker, who says he’s optimistic about taking advantage of the device. “We’re not doing anything yet,” he writes, “but Politico’s allowed me to do a couple of Flash games, like ‘Operation,’ and ‘Sarah Palin: Guardian of the Northern Frontier,’ that might work really well on it. I did a cartoon, ‘Map of the Blogosphere,’ three years ago that might deserve an update and an iPad application.” He says much of the work he does—a more interactive take on political satire—is well-suited to mobile devices. “If you invested the time and energy in a more sophisticated satirical interactive game, who knows, you might even be able to sell it through iTunes,” Wuerker writes. “I also think short sweet animations like the kind Ann Telnaes is doing for the Post ought to work especially well in this world.” There’s only one problem: Apple devices block Flash animations, a medium in which cartoonists-cum-animators like Telnaes and Wuerker often work. Comic books might seem to be a more natural fit for the iPad. Recently Marvel Comics issued a press release trumpeting the availability of 500 comic books—which is fewer issues than a complete run of Amazing Spider-Man. The comics available for the iPad are priced at $1.99 each, which is $1 less than most comics sell for in stores. Joel Pollack, the founder of the local Big Planet Comics chain, isn’t worried about the digital competition. “The death of comics has been predicted since the birth of comics,” he writes. “But one of the great strengths of the medium is its uncanny ability to co-opt other media. From radio drama to movie serials to television to big-screen to computers and the internet, comics have been able to piggyback and provide content without significantly altering the medium. I’m hopeful that digital comics will introduce new generations to our wonderful medium, and at the end of the day, create a new legion of readers/enthusiasts who want the printed items in their libraries.” Big Planet Comics co-owner Greg Bennett isn’t convinced that the digital experiment won’t backfire in comic-book publishers’ faces. “I figure that it won’t be too long ’til someone hacks the DRM, and it’ll be free digital Marvel comics for all—just like what happened the last time Marvel tried putting stuff online …” It’s a challenge that print comics already face. There are already thriving communities for comic-book piracy—in a given week, they scan and disseminate almost every book that hits shelves (they also preserve out-of-print orphaned works from defunct companies). Given that fact, Marvel’s initial price point of $2 seems wildly unrealistic for a comic you’ll read once, compared to iTunes’ current charge of $1 for a song you’ll listen to over and over. The comics industry doesn’t seem to be learning from the same mistakes the music industry has made. Bennett pointed out an editorial by Cory Doctorow. He is adamantly opposed to digital comic books, writing on Boing Boing: “I was a comic-book kid, and I’m a comic-book grownup, and the thing that made comics for me was sharing them. If there was ever a medium that relied on kids swapping their purchases around to build an audience, it was comics. ... So what does Marvel do to ‘enhance’ its comics? They take away the right to give, sell or loan your comics. What an improvement. Way to take the joyous, marvelous sharing and bonding experience of comic reading and turn it into a passive, lonely undertaking that isolates, rather than unites.” Boing Boing’s Xeni Jardin, meanwhile, is more positive about the Marvel application. Falls Church-based John Gallagher, who self-publishes his own comic books, is very optimistic about the iPad—especially since it eliminates the distribution costs that otherwise he has to pick up. The zero issue of his book Buzzboy is already available in the iTunes/iPad store; the first full issue will be there soon. “Many people say that the simple style of Buzzboy works better on screen, which I really appreciate,” he writes. He’ll also release his new comic, Zoey & Ketchup, through the Web and for the iPad before it sees print: “In fact, I’m working with several all-ages creators to help convert their kid-friendly comics to the iPad, as I think this will be more conducive to reaching young comics readers than a comic shop, just by its availability,” he writes. He continues: “I think the affect will be exponential, as not just the iPad, but the format of digital sequential storytelling takes hold. Personally, I would rather hold a musty, newsprint comic in my tired old hands, but for anyone 25 and younger, there is no issue. In fact, the comics readers I know say this makes it more likely for them to read comics, as they could never find a comics shop that suited them. My comics reach all-ages, which somehow makes them less popular for comics shops—and no fault to shop owners, many go out of their way to promote my books. But the immediacy of the iPad will hopefully open readers to the magic of comics all over again—and lead them to printed versions as well. I honestly believe the next wave of great cartoonists will show up online, on the iPad, or iPhone—comics syndicates should look to embrace print versions of PvP, Penny Arcade, and others, as the Web presence will only help.” For Gallagher, the future has already arrived. He’ll be reviewing comics for the iPad at a new Website, iPadtopten.com, which was scheduled to launch the weekend of April 10. Another local comics writer is less optimistic. Shannon Gallant, who draws G.I. Joe Comics for IDW, is worried that the art will suffer in digital media. “A lot of comics are already available online for the iPhone, but odd-shaped panels don’t work well in the rectangular format of an iPhone,” he writes. “To address this, some companies have requested that artists not overlap panels or break borders to help the reformatting of images to the iPhone.” And he’s worried about the pay for work-for-hire creators. “The iPad allows more freedom from a design standpoint, but the industry still faces the age-old question of how to make online products profitable,” writes Gallant. “I believe the digital sale of pre-existing books should be considered a reprint (and some companies pay reprint fees), but there are still a lot of work-for-hire jobs where royalties aren’t paid. With hard-copy runs you have to commit to a certain number so the math is set, but with digital copies perhaps it will have to be by the issue. Sadly, that might result in people getting a lot of checks for silly amounts, say 25 cents or so. It’s all growing pains.” My take? The iPhone probably lends itself better to the reading of a simple 3-panel daily comic strip than the iPad will. The iPad may work better for comic books and graphic novels. Assuming the iPad is a success, a significant number of comic books will probably be available on it, as will animations. But I don’t see the iPad as either a savior or a destroyer of print culture—it’ll be just another medium. —Michael Rhode

***** The CAPS (Comic Art Professional Society) Newsletter anticipated the discussion about comic books and iPad in its March issue, to which Jeff Zugale (“an admitted Apple fanboy”) contributed an article assessing the impact of the new device. Here are snippets from the piece, direct poaching is in italics: The main difference from the iPhone/iPod touch, of course, is that iPad’s size is about 8x10 inches—exactly the size of a modern printed comic book page. But physical compatibility is but a tiny aspect of funnybook future in iPad. Most of the future lies in the marketplace. Zugale turns to the Direct Market, the most viable of outlets for comic books, and finds it seriously wanting. Looking at the Top 300 titles on a monthly basis, he finds that while the No. 1 comic book sells about 100,000 copies, sales drop off pretty drastically, slipping to below 10,000 a little over halfway down the ranking. If a publisher expects make a functional businesslike profit, he must be in the top 150 on the top 300 list. How many books that aren’t Marvel or DC are in the top 150? For December 2009, it was 15—10% of the total. And the comic book at last place “averages about 3,500 copies sold.” Calculating from the cover price $2.99-3.99, Zugale says the comic book at 300th place returns a gross $4,185-5,586 to the publisher. Print/ship costs for that short a run on a color comic often exceed $1 per copy, leaving you with a paltry few hundred dollars per book (I figure around $1,200 on the average) to pay for everything else—all direct business overhead, marketing (including a Diamond Previews ad, which ain’t cheap) and paying your creators. In short, the Direct Market is not much of a market for comic book publishers. Into that abyss, however, comes iPad. iPad will bring to market a lightweight (1.5 lbs.), portable e-reader capable of displaying comic book pages at an appropriate size and in full color. ... iPad is the right size and shape for comics. Full -color comics are likely to look pretty nice on this thing. ... While I’m told line art comics look excellent on them, the Kindle, Reader and nook cannot match this because they do not feature color. Zugale then turns to the Big Question about the digital empire: how does one make money? The Internet has failed in this respect, but Zugale thinks iPad will offer a solution because Apple plans to offer books through a new iBookstore and will probably charge just as it does for an App from the App Store, an already-proven way to market digital content and feel assured you’ll get paid for it. ... If you can get people to download your comics at $2.99 each, you’d make $2,093 per 1000 units downloaded instead of just $1,196, the present rate of return via Diamond. On the downside, working through Apple’s stores has not always been smooth for small companies ... and, recently, in a controversial unilateral move, Apple has deleted all Apps containing “adult” material. ... There’s reason to be concerned about that aspect of their total control of the conduit. But advantages may overpower disadvantages. There are only about 2,000 or fewer comic book shops in the U.S. and Canada, a tiny market. iPad is bigger. Even if the iPad is not as successful as Apple’s other devices, it will still stimulate competition and imitation. Then Zugale predicts: How about by 2012 there will be 20 million e-readers capable of nicely displaying color comics pages out there. If you can somehow find and sell to even a tenth of a percent of that market—just 20,000 people—you’ve got a real chance to sell your comics as a functional, profitable business. If you are currently a print publisher, you cannot afford to ignore this kind of market potential. ***** Another enterprising observer of the passing digitalis, Chicago Sun-Times columnist Andy Ihnatko, anticipating, perhaps, the advent of iPad, interviewed honchos at both Marvel and DC Comics to see if the Big Two were poised to plunge into the electronic surf. DC Comics, he reported on March 29, currently has no digital publishing initiative to speak of. Marvel, on the other hand, launched its Marvel Digital Comics Unlimited subscription service two years ago. “It offers all-you-can-eat access to an ever-expanding library of comics (7,500, as of this week) for little as five bucks a month” ... but “it's more geared towards deep back issues rather than new releases, and you can only access these comics through the service's Flash-based website. You can't download them onto a mobile device for Internet-free reading.” Despite these differences, neither publisher is ready to jump into digital

publishing just yet. Both are waiting until “the ground firms up a lot more.” Said John

Rood, DC’s executive vice-president of sales, marketing, and business development: “I

would say that we haven't seen an opportunity as being missed yet. We're not going to

rush into any new platform or new partnership, especially if it's going to result in a sub-optimal product or a sub-optimal enjoyment, or a sub-optimal business plan." Neither company contemplates the disappearance of the printed comic book. "I think one advantage we have going for us is that people do put a premium on actually holding a comic book," says Jim Lee, co-publisher at DC. "I've done my own anecdotal market research and I ask comic book fans ‘How many of you guys are Torrenting this stuff?’ And there's always definitely some. And that definitely goes with supplementing their weekly buy, for budgetary reasons. But if you ask them ‘How would you prefer reading it?’ they always prefer to read it on paper. And I think that's very different from the difference between buying a CD and then downloading an MP3." Writes Ihnatko: “Both companies expressed a commitment to print publishing and described digital distribution as just another way of getting their stories and characters in front of an audience.” He quotes Marvel’s Brevoort: “How important digital delivery of our content is will only get greater as we see greater penetration of devices like the iPad and any other handheld reader that's got a big enough screen to display what we need effectively and still be portable enough to carry around. As those become more ubiquitous, that's going to be a delivery model that we're going to be more and more interested in and get into more and more heavily." Both companies, Ihnatko added, “stressed the importance of building a digital model that would ultimately bring more customers in to comic book shops.” Comic book shops are like mini-comicons, said Marvel's Ira Rubenstein, executive vice president of global digital media. "Going to the shop on Wednesday [when new comics arrive every week] is where they gather with the other fans and it's a real experience. I don't think you can replace that experience virtually." Their goal, Ihnatko said, is to use digital to expand the market for printed comics, and not simply replace it. Smaller publishers, however, “are working aggressively to create digital editions of their books. Many publish directly to consumers, via custom readers available through various phone platforms' app stores. But when you browse the virtual shelves of the many digital comics services that have become active in the past year (such as iVerse, Panelfly, Comixology, Graphic.ly, and Longbox Digital), indy selections overwhelm. ... Panelfly and iVerse, particularly, deliver user experiences that are close to the ideal. And Marvel, to its great credit, has been diligently working deals to make its titles available to many of these services.” But iPad will doubtless make the big difference. “The iPad—more accurately, this and the host of other slate computers like it that will be released this year — can do more to advance the market for digital comics than the workings of any comics company or creator. Apple is delivering something that those companies and creators have been seething for: an affordable consumer device designed for storing and playing content. One features a big color screen that can do justice to intricate comic book art and is built around an intuitive, tactile interface.” Stay ’tooned. ***** In a press release, IDW Publishing announced that the Apple iPad featured four IDW

comics applications at its launch. “Taking full advantage of the iPad's full-screen, full-color capabilities, each IDW store front will offer the next level of reading experience to

fans. The free IDW iPad comic shop apps each include a selection of comics with the

initial download, and offer more comics as in-app purchases. Fans can choose apps for

their favorite brands, like Star Trek, G.I. Joe and Transformers, or download the IDW

Comics app for access to all the company's iPad releases.” ***** From ICv2: Marvel is making Mark Millar and John Romita Jr.’s Kick-Ass comic book series available in a single issue format across a variety of digital platforms including the iPad, iPhone, and iPadTouch via Comixology, Iverse, and Panefly applications, while owners of Sony PSP players can down load issues directly to their device. RCH: And in all the four-color excitement about iPad, where are the newspaper

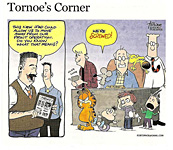

funnies? Rob Tornoe, editoonist at Politicker.com, has scored a gig in print at the

monthly Editor & Publisher, and here’s his second piercing comment on the state of

journalism and the digital future. NCS ICES THE CAKE The nominees have now been selected for the National Cartoonists Society’s 64th Annual Reuben Awards; winners will be announced Memorial Day Weekend at the Reuben Awards Dinner in Jersey City. The “Reuben Awards”—plural—takes its name from the trophy awarded to the Cartoonist of the Year (the “Reuben”) and then applies the expression to all the “division” or “category” awards—Best Comic Strip, Best Editorial Cartoonist, Best Graphic Novel, etc. Here’s this year’s list of nominees for the Reuben and for the division awards (listed by division): THE REUBEN AWARD Cartoonist of the Year Stephen Pastis, Pearls Before Swine Dan Piraro, Bizarro Richard Thompson, Cul de Sac Television Animation Kevin Deters - “Walt Disney Prep and Landing” Mike Gray - “The Infinite Goliath” Seth McFarlane - “Family Guy” Feature Animation Ronnie del Carmen - Storyboard Artist - “Up” Tomm Moore - Director - “The Secret of Kells” Barry Reynolds - Character Designer - “The Secret of Kells” Newspaper Illustration Bob Rich Tom Richmond Robert Sanchuk Gag Cartoons Glenn McCoy V.G. Myers Dave Whamond Greeting Cards Glenn McCoy Kieran Meehan Debbie Tomassi Newspaper Comic Strips John Hambrock, The Brilliant Mind of Edison Lee Wiley Miller, Non Sequitur Jerry Scott & Jim Borgman, Zits Newspaper Panel Cartoons Dave Blazek, Loose Parts Tony Carillo, F Minus Hilary Price, Rhymes with Orange Magazine Feature/magazine Illustration Ray Alma Anton Emdin Tom Richmond Book Illustration Lou Brooks - “Twimericks” Tom Richmond - “Bo Confidential” Dave Whamond - “My Think-A-Ma-Jink” Editorial Cartoons Nick Anderson Rob Rogers John Sherffius Advertising Illustration Steve Brodner Randall Enos Mort Gerberg Comic Books Terry Moore, Echo Paul Pope, Strange Adventures J.H. Williams, Detective Comics Graphic Novels David Mazzucchelli, Asterios Polyp Seth, George Sprott David Small, Stitches It’s heartening to note that “graphic novels” have finally found their way into a category by themselves (this year’s innovation) instead of being mixed in with “comic books”: the two really are separate art forms. It’s disheartening, however, to notice that some names crop up every year in the appropriate category. Is there no one else practicing cartooning in that category? Why are there never any Playboy cartoonists nominated in the gag cartoonist division? Isn’t Playboy one of the last great venues of magazine gag cartooning? Well, I guess McCoy is a Playboy cartooner, so all is not lost. But so is Frank Thorne. And Alden Erickson and Doug Sneyd and Kiraz. Alas, we missed Buck Brown. This listing will be about the most public recognition the people on it will receive. NCS has a policy of keeping such matters more-or-less secret. (That’s a joke, son: there’s no such policy—just an unhappy consequence of trying to make the Reubens Dinner a private affair to which no one, not even local newspaper reporters, are ever invited.) Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment and some of what follows is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. QUOTES & MOTS “I used to love Tiger Woods because he was a champion. But after that sex scandal, the man is a god.”—Tom (Aziz Ansari) on “Parks and Recreation,” quoted in Entertainment Weekly “Martinis so cold and big they have icebergs and undertows.” —Bill Husted, Denver Post, describing the fare at the Palm in Denver. After Tiger tied for fourth at Augusta, Fort Worth’s Dan Jenkins said: “Tiger might have saved guys big money today. If he'd won, 5 million golfers would have gone into sex rehab.”

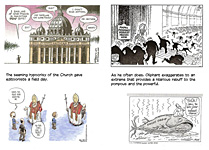

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted A recent fortnight has been more than kind to editorial cartoonists: not only did we have

Tiger Woods frolicking around Augusta with abject apologies, but we had the Pope

accused of covering up the sexual peccadilloes of Catholic priests. Both instances reek

with hypocrisy: they are virtually emblematic of just the sort of pomposity cartoonists

delight in deflating with a well-aimed pen-prick. Cartoons about both were numerous,

probably because doing cartoons about either is so easy: the gap between appearance

and actuality, between pose and practice, is so vast, so blatantly obvious, that the

realities are cartoons without cartoonists. One has merely to draw pictures of the

principals doing what they did and, presto—a cartoon appears. Who could resist the

opportunity to do an easy day’s work without having to concoct metaphors for the

commentary? And both cases have to do with S-E-X, a titillation no one in journalism

today can afford to overlook. The Pope is particularly vulnerable: he represents an aspiration so lofty that the display of any human frailty reveals the impracticality if not the impossibility of the ideal thereby devaluing it. But the grinding annoyance here is the apparent monstrous double-standard: the sins of the priests are shunted aside while everyone else committing the same sin gets arrested and becomes a registered sex offender. We’ve gone down this road with the Church often in recent years because of the common element in so many contentious matters. As Hendrik Hertzberg writes in The New Yorker (April 19): “Like nearly every one of the controversies that preoccupy and bedevil the Church—abortion, stem-cell research, contraception, celibacy, marriage and divorce and affectional orientation—it’s about sex.” And the Church’s behavior has been particularly reprehensible. As an Irish government commission (quoted by Hertzberg) put it last year: the Church’s “preoccupations in dealing with cases of child sexual abuse, at least until the mid-1990s, were the maintenance of secrecy, the avoidance of scandal, the protection of the reputation of the Church, and the preservation of its assets. All other considerations, including the welfare of children and justice for victims, were subordinated to these priorities.” The Church’s reaction to this kind of tirade has been typical—“an unsatisfactory mixture of contrition and irritation,” notes Hertzberg. The Pope himself, Benedict aka Joseph Ratzinger, whose origins in the country that perpetrated the Hollocaust and whose persona is one of Teutonic rigidity in defending the faith, didn’t help much: he was slow to react, and when he did, writing a scathing letter to the Irish Church, he seemed too eager to blame the Irish bishops and to thereby evade any responsibility at the Vatican. It is scarcely surprising, then, that the Pope becomes the metaphor for the Church in many of the cartoons on the issue. It’s morbidly enthralling to notice in the adjacent array that the cartoons by tooners in other countries (all of whom are less hung up on the sexuality of human [sic] sapiens than we are) are more explicit than those by Americans.

Lately, Vatican officialdom has taken to criticizing the press for what it claims is

excessive zeal in conducting “a well-oiled campaign against Pope Benedict.” Even the

Pope murmured darkly of “the petty gossip of dominant opinion.” And the Vatican has

its supporters in the ranks of the faithful, as Tom Toles discovered after he did the

cartoon posted here. From Kathleen B. Asdorian, Silver Spring: “The Post has dropped to a new low in its campaign of anti-Catholic bias that permeates not only its news staff but now its editorial staff. If your intent was to alienate readers, you have succeeded. This cartoon was offensive to the thousands of dedicated and holy priests who serve our church, and it ignored the fact that the Catholic Church in the United States, unlike other denominations and organizations, has directly addressed the issue of child abuse. The church has condemned the abuse done by a minority of priests, as we should condemn any case of child abuse. “The cartoon was equally offensive to members of the Catholic Church, such as

myself, who applaud the leaders of our church who have undertaken the effort to make

reparation for any harm done and to put measures in place to avoid abuse in the future.

In Washington, the archdiocese has had child protection policies since 1986 (almost 25

years). Pope Benedict XVI has done more than any other pope to address the issue.

He talked about it repeatedly during his 2008 U.S. visit and met with victims while he

was in Washington. He published a document in 2001 that requires allegations to be

reported to the Vatican and not kept in the local diocese, he wrote a pastoral letter to

the church in Ireland and he has offered to meet with victims there. It is a sad day when

what was once a major journalistic publication has become so misdirected as to

consider this ‘cartoon’ evenly mildly humorous and, worse yet, worthy of publication.” From M.J. Dodd, Edgewater: “The cynic Tom Toles again has gone over the top with his obscene March 29 cartoon. It may be true that Christ said the words, ‘Little children come to me,’ and it may be true that some priests are child predators, but most assuredly, there is no relationship. This cartoon might be expected in some low-life college newspaper. It demeans and degrades the Post.” From Mary Ann Kan, Waldorf: “The March 29 editorial cartoon by Tom Toles was grossly offensive. He quoted Scripture about little children and then proceeded to demonize an entire category of Catholic leaders, portraying all priests as evil men able to cavalierly forgive themselves. We all suffer when children are abused—by anyone. It is a terrible evil. I recommend another Scripture for us to consider. When the scribes and Pharisees brought the woman caught in adultery to Jesus, he did not ignore her sin. But neither did he ignore the sins of her accusers. ‘Let the man among you who has no sin be the first to cast a stone at her’ (John 8:7). We are all sinners, even Catholic priests. Even letter writers, like me. Even cartoonists.” From Steven J. Brown, Arlington: “As the Post often suggests, religious bigotry

is flourishing in America. It is proved in the March 29 Tom Toles cartoon. Substitute a

rabbi, an imam, a black preacher or most any other cleric in a similar light and there

would be marching and protesting. The implied condemnation of all the priests of the

Roman Catholic Church for the crimes of a few and the poor judgments of others is not

fitting for a paper of the Post's influence.” Celibacy is erroneously cited in some quarters as the cause of pedophilia. No psychologist would agree. But clerical celibacy seems to signal, at the least, a hang-up about sex, which is no more at the root of celibacy’s doctrinal origins than homosexuality, another erroneous supposition. For the first thousand or so years of the Church’s existence, Catholic priests married and had families like anyone else. It wasn’t until the Church had grown monolithic in power and was consequently laced with corruption that celibacy was adopted, ostensibly in purified spiritual dedication but actually as another link in the chain that tethered the institution to worldly preoccupations. By the time Bruno of Toul became Pope Leo IX in 1049 after walking barefoot to Rome as an act of personal devotion, the impulse for reform was fairly prominent in Vatican circles. One abuse in particular called for change. The practice of simony, the buying and selling of clerical posts, when coupled to clerical matrimony, threatened to turn the Church into a social institution reflecting exclusively the interests of the rich and the powerful. The rich could afford to buy clerical posts; and married priests and bishops were likely, in the usual fashion of the day, to pass their high offices (which comprised vast estates and incomes) on to their children. By way of making a start at reformation, Leo deposed several French prelates guilty of simony and ordered bishops to put aside their wives. Simony eventually re-emerged in other forms (selling indulgences, for example), but celibacy, because it had less to do with profitable ecclesiastical practices, was comparatively easy to establish and enforce. Leo’s efforts were not markedly successful, but soon after Gregory VII came along in 1073 and enlisted the monastic ideal of celibacy in his reformation, the Church formally adopted clerical celibacy (in 1139, according to my sources), and with the formality made enforcement practical. The monastic ideal helped secure the establishment of celibacy for priests—and to some extent, perpetuates it today—but initially the impulse had been fostered by a desire, commendable enough, to prevent the take-over of the Church by the rich and powerful, that is, by the profane rather than the sacred, worldly rather than spiritual power. Saintliness was not the objective: preserving power was. ***** What with all the tumult and shouting in religious matters—not to mention the religious fervor that infects so much of our political discourse these days—religion becomes a matter of secular concern and, as such, attracts comment in this corner. Just to put all the dominoes on the table, then, here’s my personal approach to religion (so you can discount everything I say on such matters by reason of what I believe). Someone once said that religion is essentially a tribal matter. It has more to do with “tribe” (and belonging thereto) than with morality. I think that might be true. The necessity, the imperative, for moral behavior undergirds all religious movements, regardless of the doctrines of different faiths, different tribes. The Pope, like many in the business of propagating religion, believes that faith is the basis of morality. In a manner of speaking, it is. But morality is broader based than simple religious faith would have it. Morality is a social science: it originates in the human condition. Because the human sapiens (sic) live in groups, the human condition is essentially social. Thus "good" is whatever enables both individual and the community; "bad" is whatever interferes with that enabling. Individuals seek the “good” by attempting to fulfil their potentials to achieve whatever they are capable of achieving, to enjoy whatever they believe they are likely to enjoy—and, in the process, to avoid the “bad.” The goal is two-fold: realize the “good” while avoiding the “bad.” Religious faith has historically simplified the social science of morality by codifying it. In early times, the simplification made it possible for vast numbers of basically uneducated and illiterate peoples to behave in a moral manner. As human knowledge accumulated through the ages, however, faith was repeatedly questioned. With every advance of science, the existence of God was brought into question. Joseph Campbell's metaphor is useful. In his series of books under the banner "The Masks of God," he suggests that God endures: every advance of scientific knowledge strips away one of the masks of God, and for a while, we believe the new mask that we see is the actual face of God. The next advance of knowledge, however, persuades us otherwise. But for Campbell, the essential truth is that regardless of how many masks are stripped away, God remains, even if behind yet another mask. Scientists are confounded by this mystery because for them only verifiable, measurable phenomena are real. Metaphors are too vague. In the confrontation between science and religion, a single complex of questions seems posed before us: what is life, and why do we live? Life, it seems to me—at least as far as humanity is concerned—is consciousness. We may live in part in order to perpetuate the species, but our other assignment (so to speak) is to experience the “good,” to be conscious of it. As far as science and religion are concerned, thinking people make an effort to reconcile science and religion, to bring them together in a consciously perceived whole. In this endeavor, fundamentalism, whether Christian or Muslim, is, as some irrepressible wag said, a hardening of the categories. And it may be wholly beside the point. The point, I’d say, is to live the “good” life. I’m not convinced that God fits into this. Or whether, even, He is necessary to it. Maybe the much advertised love of God is instead just the love of good.

***** Clay Bennett, editorial cartoonist at the Chattanooga Times Free Press—who has won

just about every award in season for editooning—has just received the first annual

Phillipp “Fips” Rupprecht Prize for Collectivist Hate Cartoon Excellence. The so-called

“prize” is the invention of a blogger named (we think) Mike Vanderboegh, a gunslinger

who operates a teabagger* site, sipseystreetirregulars.blogspot.com. In selecting a

name for his “award,” Vanderboegh has displayed admirable ingenuity: Phillipp

Rupprecht, pen-name “Fips,” was a German cartoonist notorious during the Nazi era for

his anti-Semitic cartoons fomenting hatred for Jews. Bennett won the dubious Sipsey

Street distinction for the cartoon that appears here at the upper left of our visual aid. In giving a prize to Bennett, Vanderboegh betrays his penchant and that of his minions for indulging in extreme behavior: just as they interpret any action by a governmental body as “taking their country away” from them, so do they see any attack on any idea they favor as an act of hatred. Civil discourse with such personages is not just impossible, it borders on dangerous: most of this ilk are avid gun fanciers and tend these days, as an presumably symbolic act, to wear sidearms when they go to political rallies, saying they are merely exercising their Second Amendment rights. Symbolic maybe; intimidating, definitely. Few among us would openly disagree on a political issue with an armed individual bristling with hostility who tends to shout rather than reason. A loud and threatening citizen undermines the very principles upon which democracies are founded, principles he claims to want to uphold.

* See immediately below.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST: PART THE FIRST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. I’ve taken a vicious delight in calling members of the Tea Party “Teabaggers,” but I didn’t know, until recently, the sexual connotations of the term “teabagger.” Now, however, I know. I learned by googling, which led me, inexorably, to Wikipedia. I now quote (in italics) the entire entry on the subject as a demonstration of just how painfully exhaustive Wikipedia can be on a popular topic: Teabagging is a slang term for the act of a man placing his scrotum in the mouth of a sexual partner. The practice resembles dipping a tea bag into a cup of tea when it is done in a repeated in-and-out motion. As a form of non-penetrative sex, it can be done for its own enjoyment or as foreplay before other activities, such as oral sex. The practice has also been mimicked in online video games, as a practical joke, and in hazing incidents. The scrotum only touches the face or head in some of these instances, though sometimes more activity is involved. Teabagging has become more prominent in the media, and the term is used to ridicule those in the Tea Party movement Along with the penis and perineum, the scrotum is sensitive. This makes varying degrees of stimulation an integral part of oral sex for many men. Teabagging is an activity used within the context of BDSM and male dominance, with a dominant man teabagging his submissive partner as a variation of face-sitting or to inflict erotic humiliation. Although it may be unappealing to some, teabagging does not need to be physically harmful or uncomfortable for the individual performing the oral stimulation. Its gain in prominence has been attributed to its depiction in the film “Pecker,” which was released in 1998. It has since become popular enough with couples to be discussed during an episode of “Sex and the City.” Sex experts have praised various techniques that the performer can use during fellatio to increase their partner's pleasure. These include gently sucking and tugging on the scrotum, use of lips to ensure minimal contact with their teeth, and different body positions. Callers on the “Howard Stern Show” once debated whether or not licking and fondling is considered teabagging. Teabagging has also been recommended as a form of foreplay or safer sex. According to Dan Savage, the person's who's scrotum is being stimulated is known as 'the teabagger' and 'the teabaggee' is the one giving the stimulation. "To teabag someone, you need a scrotum with which to teabag them: the teabagger dips sack; a teabaggee receives dipped sack." RCH again: As the man said, once, this may well be more about penguins than you want to know. And now that I am highly informed, I still think “Teabagger” is exactly the right term for denoting a member of the Tea Party: all those Teabaggers who are rampaging around the body politic are displaying a nearly ungovernable eagerness for some excitement; they find political stimulation dipping in and out of parades and riots. But these “Apostles of Anger in their echo chamber of fallacies” (coinage by Charles M. Blow in the New York Times) aren’t, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, nuts. A recent New York Times/CBS News poll found that Teabaggers are “wealthier and more well-educated than the general public, they tend to be Republican, white, male and married, and their strong opposition to the Obama administration is more rooted in political ideology than anxiety about their personal economic situation. ... Despite their allusions to Revolutionary War-era tax protesters, most describe the amount they paid in taxes this year as ‘fair.’ Most send their children to public schools, do not think Sarah Palin is qualified to be president, and, despite their push for smaller government, think Social Security and Medicare are worth the cost.” Teabaggers might be more like the general public than we’d supposed, but they still fail the duck test. If they go around armed like crazy people, if they tend to shout irrational slogans like crazy people, and if they dress oddly like crazy people, they’re probably ducks—er, crazy people. And some of them are “tenthers.” Tenthers construe the Tenth Amendment of the Constitution to mean individual states can reject, or nullify (declare void), any Congressional legislation the state disagrees with. This right, Tenthers say, arises in the language that stipulates “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.” In the American Prospect last August, Ian Millhiser wrote: “Under the Tenther constitution, Barack Obama’s health-care reform is forbidden, as is Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. The federal minimum wage is a crime against state sovereignty; the federal ban on workplace discrimination and whites-only lunch counters is an unlawful encroachment on local businesses.” Nullification as a challenge to the supremacy of the U.S. Constitution has been around since at least 1798, but it has been discredited time after time. In 1832 when South Carolina passed an ordinance nullifying a tariff that might have interfered with the institution of slavery, Andrew Jackson, prez at the time, proclaimed nullification “pernicious nonsense.” Sean Wilentz at the New Republic continues: “The nation, Jackson said, was not created by sovereign state governments—then as now, a basic misunderstanding propagated by pro-nullifiers. Ratified in order ‘to form a more perfect union’ [my emphasis], the Constitution was a new framework for a nation that already existed under the Articles of Confederation.” So the Constitution intended to make an existing nation a more perfect union than it had been up until the adoption of the Constitution; until then, the country was a less than perfect union. “‘The Constitution of the United States,’ Jackson declared, created ‘a government, not a league.’ Although state governments had certain powers reserved to them, these did not include voiding laws duly enacted by the people’s representatives in Congress and by the President [also elected by the people]. ... Nullification and [its cohort] interposition are pseudo-constitutional notions taken up in the face of national defeat in democratic politics. Unable to prevail as a minority and frustrated to the point of despair, its militant advocates abandon the usual tools of democratic politics and redress, take refuge in a psychodrama of ‘liberty’ versus ‘tyranny,’ and declare that, on whatever issue they choose, they are not part of the United States or subject to its laws—that, whenever they say so, the Constitution in fact forms a league, and not a government.” In the same issue of the magazine (April 29), TRB’s Jonathan Chait puts his finger on the fundamental cause of all the tumult and shouting: “Large swaths of the Republican Party simply refuse to accept the legitimacy of losing political outcomes.” If they lose, they lose because of some underhanded and therefore illegitimate maneuvering by their opponents. They decline to accept the basic premise of an electoral process—that in every such contest, someone must lose because not everyone can be a winner. Too bad. Meanwhile, the Teabaggers go forth, foaming at the mouth, walking like

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution The next big thing in content distribution is mobile, according to Steve Buttry, director of community engagement for the Washington metro-area digital-only news project backed by Allbritton Communications. Faced with this dawning new age, newspapers that are chasing after the Web are “fighting the last war,” he says, quoted in Editor & Publisher (March 2010). “A news organization that wants to be successful in the future is going to be focusing hard in the coming years in thinking mobile first.” Gartner Research predicts that mobile phones will overtake computers as the most common Web access device worldwide by 2013. Clyde Bentley, a professor in the Missouri School of Journalism, says: “If Gartner’s prediction is accurate, newspapers really have just 18 to 24 months to position themselves as the leading news content provider for mobile platforms. This is a killer deadline: within 35 months, the whole newspaper industry needs to move its emphasis from the static Web to the mobile Web.” On the cusp of a new paradigm, newspapers have a chance to do something to take charge of it instead of being victimized by it. They must not make the mistake of giving away content again. The New York Times and Associated Press already have applications that have been downloaded by millions: the adoption of the iPhone app for the Times virtually doubles the paper’s Sunday circulation. The Times plans early this year to roll out a metered pay model, and “once the online pay strategy is in place, the company will charge for its mobile site and applications.” CNN is already charging for its app. The Wall Street Journal introduced its app for free in September 2008 then slapped a price on it a year later. And advertisers appear willing to go along: WSJ has doubled its ad revenue from mobile since last year. And AP reports “the sheer number of advertising insertions orders has ballooned since November and every week since.” All of which is vastly encouraging as well as intimidating: move now or get left behind. My bet, and that of others quoted in the E&P article, is that newspapers have learned their lesson and won’t let history repeat itself. Now—where are comics in this new mix?

***** When Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp bought the Wall Street Journal in 2007, journalists everywhere wrung their hands in agony, predicting that the highly respected WSJ would be turned into one of Murdoch’s Page Three Girl tabloids. But that hasn’t happened, according to Editor & Publisher (April 2010). Not only is the paper still a distinguished journalistic enterprise, it’s thriving. It’s circulation has increased to more than 2 million subscribers, making it the largest daily in the U.S.; and advertising revenue is up 23% from a comparable period a year ago. WSJ is hiring, too—adding about three dozen journalists at a time when the rest of the industry has shed 27% of its newsroom positions. And its website is equally robust. The Journal charges readers for all content, regardless of point of access; and its website revenue is about $200 million in subscriptions, representing 15-20% of total revenue, and traffic is up 25% to about 22 million users. But no comics. No editorial cartoons either.

BADINAGE AND BAGATELLES Rob Fusari, the abandoned beau of Lady Gaga, reveals in the complaint he filed in a lawsuit against his former inamorata that she, like many more ordinary folks, was conceived accidentally: he once sent her a cellphone text using the moniker “Radio Ga Ga,” and his phone’s spellcheck changed “Radio” to “Lady.” The erstwhile Stefani Joanne Germanotta loved the mistake, changed her name accordingly, and started dressing funny. Voila!