|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Apart from celebrating the yuletide, we also celebrate Nell Brinkley in the longest of this posting’s pieces, and we continue our public service of supplying titles for your Christmas Bookwish List, even though it’s probably too late for this year. All the titles reviewed are listed below, where we indicate what’s here this time, by department, in order: Burping and Farting: The Church vs. State Holidaze A Couple Nude Woods NOUS R US Editor & Publisher May Be Dying Free Comic Book Day, May 1 Tintin Flaps Your Eustace Contest at The New Yorker Phoney Australian Cartooners Frazetta Arrested for Burgling His Father’s Museum EDITOONERY 2010 Kalendar Fame Not Shame More Death in Afghanistan THE FROTH ESTATE Crowd Sourcing? BOOK MARQUEE Comic-Con: 40 Years of Artists, Writers, Fans and Friends Notes: A Study Guide to the Best in Undead Literary Classics The Playboy Cartoons (a new low-priced edition) Graphic Classics Masterpiece Comics Grown-Ups Are Dumb Rip Kirby: Complete Comic Strips, 1946-1948 World War II in Cartoons LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS The Amazing, Remarkable Monsieur Leotard Eddie Campbell on the Graphic Novel Genre Vatican Hustle Shortcomings Logicomix Rapunzel’s Revenge FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Diary of a Stinky Dead Kid BOOK REVIEWS The Last of the Funnies Nell Brinkley and the New Woman in the Early 20th Century The Brinkley Girls: The Best of Nell Brinkley’s Cartoons From 1913-1940 PASSIN’ THROUGH Remembering Ken Krueger and Irving Tripp And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— BURPING AND FARTING THROUGH THE SNOW. Tis the season, once again—as it is every year at this time—for the hanging of the greens from every downtown lamp-post, for too thin men to dress in red and wear false whiskers in order to better ring silver tinklebells near iron kettles, and for the anyule confrontation of church by state and vice versa. What would Christmas be without a visitation from the Cratchits and the Scrooges? And here in the holy city of Denver, the disputation can take place on a Grand Scale. Downtown, the city and county building, an imposing but gracefully spired and colonnaded edifice located at one end of a long park-like sward of green and flower gardens with the state capital building at the sward’s other end, is, as usual during this season, ablaze with lights and hung with evergreens that provide a festive setting for Kris Kringle and his cattle-drawn sled, a regiment of toy soldiers, and a nativity scene in which life-size plaster figurines bow before a plaster baby in the manger while a recording of Christmas carols is played over a loud speaker—a massive assault on the state by the church, you’d think, but you’d be wrong. Denver’s Christmas extravaganza has survived every legal challenge mounted against it for 90 years—that’s right, the festooning of city hall has happened every December since 1920. And those who mutter that it’s illegal are wrong: both the U.S. and Colorado Supreme Courts have ruled that nativity scenes on government property are permissible if the decorations also include figures such as Santa Claus, reindeer and toy soldiers. Denver Post columnist Susan Greene professes to be baffled by that ruling: “It’s like telling your kids it’s okay to burp really loudly at the dinner table as long as they fart too.” A Hanukkah menorah was added to the display a few years ago, “presumably,” Greene says, “to appease Jews who were cranky about the creche.” Greene is a Jew, but she doesn’t object that the menorah has, inexplicably, disappeared lately: “I am comfortable with its apparent removal on the theory that less religion is usually more at city hall.” Legally speaking, the dispute is moot: Christmas is a national holiday by federal fiat. But there are other considerations than the legal in a multi-cultural milieu. Paul Rudnick at The New Yorker (December 21 & 28) offers “some tips to help the sensitive Christians make everyone feel at ease and have a Happy Interfaith Holiday Season.” Among his hints are these: (1) When non-Christians are present, don’t call Jesus “Our Savior,” “Our Lord,” or “Mister Perfect.” Refer to him more casually, as “the Son of God or maybe not,” “the Jew that got away,” or “the bachelor.” When chatting with Jews, try to avoid the subject of the death of Jesus. If a Jew asks, “So how did Jesus die?” simply say, “Natural causes.” (2) Try to take a delighted interest in the Jewish holidays by asking questions like “Do you ever create a tiny Victorian village under your menorah?” “Does your family sing ‘Silent Night’ in Hebrew?” (3) Never refer to Hanukkah as “their Christmas,” “Merry Wannabe,” or “the Goldberg variation.” Very few, if any, of Rudnick’s hints would appear to help Muslims have a Joyeaux Interfaith Holiday, but maybe it’s too soon. Up the road at Fort Collins, Sheriff Jim Alderden, the man who tricked the Balloon Boy’s parents into admitting the kid’s flight was a stunt and a fraud, conducts what he calls the “Apparently Annual Politically Incorrect Christmas Tree Trimming Party” as a protest against those who protest public displays of the accouterments of what most of us regard as a Christian festivity. The party includes prayers, Christmas carols, horse-and-buggy rides, and a visit from St. Nick. “It’s a real Norman Rockwell type of event,” Alderden said. It’s privately funded and takes place on land beyond the city limits. This year, the Leaders of Freethought and the Colorado Coalition of Reason had a sign on the premises: “During this winter-solstice season, illuminate your mind with reason. Let friends and family warm your heart. And celebrate that we all take part.” The satirical Alderden had no objection to the sign (or, we surmise, to the sentiment). Said he: “I told them I got a big empty spot out there just for atheists.” Whatever our persuasion, we admire his sense of humor: among the things we need most these days a good laugh is near the top of the list. But maybe all the fuss is for naught, regardless of denomination or faith or the lack thereof. Christmas is no longer, and hasn’t been for decades, a religious event. Christmas as we now know it was invented almost single-handedly by Charles Dickens. Before Dickens started writing about Scrooge’s miraculous transformation (which was effected by secular ghosts, not by any religion) and dancing at Fezziwig’s the annual office party and the gustatory delights of roast goose and plum pudding at the Cratchits, few of our present Yuletide practices existed. Christmas as it is presently celebrated for most of December (and, lately, November) is therefore a literary convention, not a sectarian one. Personally, I plan to play it safe henceforth. I’m going to be wholeheartedly evenhanded about it. I intend to vacillate, year by year. This year, I wish everyone Merrie Christmas; next year, Happy Holidays. For the time being, then, here’s hoping your holidays include a few good laughs and other merriments, satirical or not, a dash of Dickens (the goose and the plum pudding at least) and no zombies. ***** And now, here’s that scandalous imagery you’ve ’tooned in to inspect—a couple of Lawson Woods, pictures of cavorting nearly naked chimps and apes of the sort that, in the days of our long lost youth, decorated the covers of magazines like the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s. Gran’pop chimp and his ever-scampering and usually mischievous juvenile relatives were regularly featured on calendars, too, especially prevalent at this time of year, and these images are taken from a couple I found in a flea market not long ago. Young and old, I’ve always been charmed by them. Despite wide exposure in this country, Lawson Wood (1878-1957) was a Brit and, to the best of my knowledge, never left his native land. Son and grandson of artists, Wood embarked upon his freelance illustration career in 1902, specializing in humorous tableaux. By 1906, his work was well-known and widely appreciated, especially a series of “prehistoric” paintings that featured stone age humans and caricatures of dinosaurs. It wasn’t until after “the Great War” (World War I) that his simian characters began to appear more and more frequently. For more monks by Wood, just Google his name, and they’ll come up like crocuses in the spring. Oh—one more thing: Wood’s monkeys were more often unclothed in the early years; after American prudery took hold, either Wood or someone acting for him put trousers on Gran’pop and the rest of the gang.

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits FUBAR (Fouled Up Beyond All Recognition): Last time, I asserted, wildly and incorrectly as it turns out, that Sarathan Livingston Palin’s book had fallen off the New York Times bestseller list. Not true. I was, alas, taking my cue from the NYTimes list of November 20, compiled before Going Rogue had been on sale long enough to rank. By the next week, ending November 27, Sarah the Palin’s book was right up there on top of the list. Sigh. And again the following week. Double sigh. And even two sighs are not enough. Stan Millage of Sioux City, Iowa, got in line at 4:30 a.m. for a Sarathan Livingston Palin book signed by the author. He explained: “She’s a down-to-earth person who will fight against the government. I can see her out there fishing with the guys. Plus, she’s hot.” Finally, an honest assessment of Sarah the Palin’s extraordinary appeal. Who’da thought? That photo of her in shorts on the cover of Newsweek worked its sensual spell on a nation of males in the advanced stages of arrested development. Sigh sigh sigh. Cough. Wheeze. Gasp. Convulsion. ***** ANOTHER DEATH IN THE FAMILY? Editor & Publisher, the bible for the newspaper industry for more than 125 years, may be following many of those newspapers into oblivion, another victim of the crunching economy. Nielsen Business Media, which owns E&P, announced in early December that it was selling eight of its “brands” and ceasing operations for E&P and Kirkus Reviews at the end of the month. It was just a year or so ago that E&P discontinued its weekly print publication, fleeing into the digital ether for up-to-the-minute reportage and going to print only once a month. Its staff had been whittled to the barest nub: I make it 3-4 editors, all reporting and writing. Cartooning’s most knowledgeable reporter, David Astor, was laid off about a year ago, leaving syndicated cartoonists without an assigned reporter. But then— in an online report December 14, E&P editor Greg Mitchell said “due

to overwhelming reader and advertiser demand, Editor & Publisher will publish its next

print issue, the January 2010 edition, as planned.” It may not be the end after all. The E&P report concluded: “A number of outside companies and individuals have

expressed interest in possibly keeping E&P going, so stay tuned for updates. Thanks

again for the thousands of messages of support and media/Web coverage.” ***** From Publishers Weekly, December 15: Some of the Titles for Free Comic Book Day, May 1, 2010 ROUNDING UP BITS AND SCRAPS According to a press release from Simba Information, which describes itself as “a leading authority for market intelligence in the media and publishing industry,” one in 10 adult book buyers read comics and 70% of those adults who have read comics in the previous 12 months also bought at least one book. Simba’s monthly Book Publishing Report says: “Nearly overlooked for decades, the burgeoning market for graphic novels and comic books has led retailers to pause and address the industry in new light. ... ‘Graphic novels are unlike any other segment of publishing, but are often mislabeled as just another category within children's book, so they miss the chance to really shine,’ said Warren Pawlowski, analyst for Simba Information's Trade Books Groups. ... Graphic novels have almost become their own industry at a time when growth in traditional publishing has become practically non-existent. ... ‘Graphic novels appeal to the largest audience possible and have untold potential because of it,’ said Pawlowski. ‘The niche that graphic novels have been forced into has exploded, and what could never be found elsewhere is being seen [in major media] in droves.’” Reuters reports that actor Warren Beatty can go ahead with a California lawsuit

against a unit of bankrupt Tribune Company over rights to comic strip detective Dick

Tracy, ruled a federal judge in November. The decision, however, does not resolve the

larger issue of whether Beatty can make another movie or tv show with Tracy. The

bankruptcy judge ruled that the California case could proceed but at the same time did

not dismiss an action by the Tribune that has asked a bankruptcy court in Delaware to

declare Dick Tracy the company’s property." Arguably, granting the stay motion to

permit this dispute to move forward in the 2008 California action may very well leave

nothing to do in the adversary proceeding," the judge wrote in his decision. A source

close to the dispute said the two sides will be discussing ways to resolve the matter by

moving forward in California. As the Steven Spielberg Tintin movie nears its debut, slated for 2011, we see more frequently evidence of legal disturbances on the Herge horizon. Lately, for instance, Bob Garcia, a British detective novelist, jazz musician and Tintin aficionado received in November a court order to pay £35,000 or face the prospect of bailiffs seizing his house and belongings. “His crime,” reported Henry Samuel of the Telegraph, “was to have written five essays on Tintin sparked by his boyhood love for the squif-haired reporter and his dog Snowy—a passion he wanted to impart to his own children.” Other Tintin fans have been pressured to cease and desist writing about Herge’s famed boy reporter. They are all the targets of attacks by a British lawyer named Nick Rodwell, who holds “the exclusive rights to the oeuvre of the Belgian Hergé (born Georges Rémi) and the Tintin since he married the cartoonist’s widow, Fanny, 16 years ago. In the Garcia case, the court ruled that he had violated the author's moral and proprietary rights,” but the disputation goes on apace. Tintin fans are lining up on Garcia’s side, accusing Rodwell of a ruthless drive to kill off their harmless and not-for-profit passion in his bid to keep exclusive control of the Tintin brand. Garcia says his supporters had written to Spielberg asking him to intervene. Said Garcia: “Rodwell’s problem is he's walking in the footsteps of a genius and is only ever referred to as the 'husband of Hergé's widow'. It must be very frustrating and may explain his violence towards those that really love Hergé's work.” More, no doubt, will transpire. The New Yorker once again will welcome submissions in its Eustace Tilley contest—reinterpretations of the iconic first issue cover drawing of a dandy by Rea Irvin; winners will be featured at newyorker.com (where you can witness a host of previous brilliantly inventive submissions and winners; surely the magazine will publish a book collection of them soon). For contest rules and to enter, visit newyorker.com and scroll down the opening page to “Your Eustace.” Deadline, January 18. ... Contests for editorial cartoonists abound—nine of them: National Newspaper Awards (Canada), National Headliner Awards, Thomas Nast Award, Scripps Howard Foundation National Journalism Award, Fischetti Competition, Herblock Prize, Pulitzer Prize, Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, Sigma Delta Chi Award, plus three competitions for students: March of Excellence Award, Charles M. Schulz Award, and the John Locher Memorial Award. Deadlines for submission are mostly in January and February. What with the dwindling number of editoonists, we should expect all those still at work to win at least one of these at least once every three years. ... On Publishers Weekly’s list of the ten best-selling comics for December (dated December 15) half are manga; the other five (and their rank) are Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Dog Days (1), Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Last Straw (2), The Book of Genesis Illustrated (3), Logicomix (7) and Green Lantern: Agent Orange (10). ***** UNDER-HANDED DOWN UNDER? Editoonist David Horsey of the Hearst papers noticed last month another of those ethereal frauds. He had repeatedly been sent via the Internet a batch of editorial cartoons introduced with this claim: Australian Cartoons ... Not Seen in America The point is reiterated after displaying the cartoons: “These cartoons are not of USA Origin!! The charge, coming, without question, from the Righteous, is that the U.S. news media is too liberal to ever publish such gross attacks on its liturgy. But in this case, the charge rests on wholly erroneous grounds. Said Horsey: “As I looked through these ‘Australian’ cartoons that were so bold and skilled in their lampooning of the American left, I thought to myself, ‘Gee, this drawing style looks kind of familiar, and, golly, I think I've seen those signatures before.’ There was S. Kelley (that would be Steve Kelley, my friend who is the editorial cartoonist for the New Orleans Times-Picayune), Ramirez (that would be Michael Ramirez, another buddy of mine who lives in Los Angeles and is one of the most-widely syndicated conservative cartoonists in the United States), Glenn McCoy (yes, another American cartoonist who, the last time I saw him, definitely did not have an Aussie accent) and Chuck Asay (a Colorado cartoonist with whom I watched the 4th of July fireworks burst over the Lincoln Memorial a few years ago). The other cartoonists were American as well.” Horsey wrote the person who had sent him the cartoons, explaining how mistaken the representation was, and his correspondent shot back: "Typical leftist reply, personal attack instead of dealing with the facts and truth." To which Horsey muttered: “I guess he's not into ‘fact-based reality,’ to borrow a derisive phrase from the Bush administration. It may seem strange,” Horsey went on, “that someone would make a claim—Australian cartoons that would never run in the American media!—and at the same time provide the evidence—the cartoonists' names and newspaper affiliations—that disproved the claim. But, when making a mass dump on the Internet that can't be traced, I guess there's no need to be all that careful, especially when the people who agree with you will forward the message without knowing or caring that it's a fabrication.” On the roster of American editorial cartoonists, liberals outnumber conservatives

by a substantial margin, no question; but conservative editoonists exist and are healthy,

and as Horsey notes, they are being published, willy nilly, all across the land. The U.S.

news media may be biased to the left, but it hasn’t shut the door on right wing opinion. ***** FAMED FANTASY ART MUSEUM BURGLED. Late at night on December 9, the son of Frank Frazetta was arrested as he and an accomplice were loading some 90 of the celebrated illustrator’s paintings, valued at $20 million, into an SUV outside the Frazetta Art Museum, which they had broken into with a backhoe. The Associated Press reported that state police charged Alfonso Frank Frazetta, 52, with theft, burglary and trespass and threw him in jail; bail was sent at $500,000, but the next day, a judge reduced the amount to $50,000. Young Frazetta’s wife, Lori, said at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SG0q-pHgbg

that her husband was acting at his father’s request to secure the paintings by storing them in another location, presumably to protect them from the predations of other members of the Frazetta family, who, since the death of the artist’s wife Ellie some months ago, are feuding over who gets what. The senior Frazetta was in Florida at the time, and early accounts reports said he denied that his son had his permission to take possession of the paintings. The Pocono Record later reported that young Frazetta's attorney said that a notarized letter from Frazetta pere gave the son permission to take the artwork. A notary public, Adeline Bianco, testified that she handled the letter. Lori Frazetta said at a press conference that her husband and his mother ran the family business—the Museum and the marketing of Frazetta’s art—until Ellie’s death, when the family fight over the paintings began. She said her husband notified state troopers of his intentions to inventory the paintings, pursuant to civil litigation among family members. She also said Frank “Jr.” was planning to take the paintings to a secure location when he was arrested. The family feud pits two daughters and one son of famed artist against his other son, Alfonso, the break-in expert. One of the questions I’m left with after pondering the reports of the incident is: Why did young Frazetta need a backhoe to get into the Museum? If he was running the place with his mother, didn’t he have keys? Probably his quarrelsome siblings have changed the locks in the middle of the wrangle. The other question isn’t a question so much as it is acknowledging that Frazetta, the famous one, could be mistaken about whether he’d given his son permission to “secure” the paintings. Maybe he gave “permission” by answering a question—“Dad, do you think I should secure these paintings somewhere else?”—with a casual “Yes” without thinking what the implications might be. I first became aware of Frank Frazetta long before he was a famed fantasy illustrator. When I read his Dan Brand stories in White Indian No. 11 in 1953, I admired his drawings. (White Indian, which isn’t mentioned in Krause’s Standard Catalog, ran only a few issues and consisted, I’m guessing, of Dan Brand stories culled from other ME western titles and then compiled and reprinted under the White Indian title.) Then comic books all but disappeared, and I didn’t encounter Frazetta’s work again until the early 1960s, by which time, he was already the famed illustrator, no longer a mere cartoonist. I only saw him in the flesh once. It was during the San Diego Comic-Con some years ago, and I was browsing in Jim Vadeboncoeur’s adjunct booth in the Bud Plant allocation, when Jim sidled up to me and wagged his head in the direction of a popeyed fellow standing nearby, clutching a camera. “That’s Frank Frazetta,” Jim said, “but don’t let on. He doesn’t want to be recognized or cause a fuss.” So I didn’t let on, but I watched Frazetta as he photographed the seductive tush of one of Plant’s operatives, who was wearing a tight white knit dress. When, after Frazetta left, chuckling over his picture-taking and his prey, the young woman was told she was the object of the famed Frazetta’s ogling, she was squirmed with delight. Whether she later modeled for him, I can’t say. MORE MISCELLANEOUS According to Brooks Barnes, Disney's "The Princess and the Frog," while earning a healthy hoorah of critical acclaim and finishing first in the box office sweepstakes on its opening weekend, came in at “the low end of industry expectations with $25 million in ticket sales at North American theaters.” Judging from the previews I’ve seen, this “high-profile effort to revive hand-drawn animation” is a remarkably successful effort: it has visual energy and the comedic liveliness of exaggerated action that we once saw in every Disney animated film but haven’t seen much of for at least a generation. Barnes adds that the sales on “Princess” improved on Disney's last effort in the hand-drawn genre: 2004's "Home on the Range" opened to just $13.9 million. Barnes goes on: “Disney has been criticized for years for its lack of African-American royalty. Some black commentators attacked Disney's handling of the movie's characters and story early in the production process, but the finished movie has largely quieted critics worried about racial insensitivity.” Lurking hereabouts, the phantoms of Walt Disney’s frustrations when “Song of the South,” which he carefully vetted with African Americans and even engaged a “liberal” scripter to insure it would be politically correct, nonetheless outraged segments of the black community. Steampunk, that’s the word for it, the “it” being the current pop culture preoccupation with what might be called “Victorian tech,” a world Time reported (on December 14, too late for me to know all this when Opus 252 was posted) in which computer technology used brass and steel and leather and mahogany instead of sillicon and plastic—clockwork instead of electronics. The Abrams book I reviewed last time, Boilerplate: History’s Mechanical Marvel, by Paul Guinan and his wife Anina Bennett about a Victorian robot, is in the steampunk tradition. It’s a spoof of sorts, as I said; but it also revels in steampunk. Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. TICS & TROPES “Do not be too moral. You cheat yourself out of much life so. Be not simply good: be good for something.”—Henry David Thoreau (who used his middle name regularly long before it was the fashion) W. Bruce Cameron, humor columnist, writing about bicycling as a health regimen: “ Serious cyclists think cycling is about pain. To me, a bicycle is a serene mode of transportation —you pedal a few blocks to the bakery, go in for a doughnut, and when you come out, your bike is stolen.” Cameron continues on the question of weight: “There is no good way to lose weight. There are only good ways to gain weight.” EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted If, like me, you’d like to know more about “today” than its number in the sequence of

days this month—more, that is, than “today is the 25th of December”—then you’ll like The Economist wall calendar (or Kalendar) for 2010, the “first ever” calendar the

magazine has ever attached its name and reputation to. Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher,

formerly the staff editorial cartoonist at the Baltimore Sun (for 15 years beginning in

1988) and longtime editoonist at The Economist (the magazine’s first, since 1978),

identified a score of obscure anniversaries in every month (in January, the leaning

tower of Pisa closed on the 7th in 1990 due to excess leaning; the roller coaster was

patented by La Marcus Thompson on the 20th in 1885; first lifeboat designed for sea

rescue was tested on the 30th in 1790) and then cartooned these phenomena in a

panoramic page of colorful caricatures and lively “goomies” (see Willard Mullin in Harv’s Hindsight) that looms over the days of the month. ***** The Big Event of the month was not, as you might suppose were you from another

planet, the so-called debate on health care reform or troops marching off to the killing

fields some more or the confabulation about global warming in Copenhagen, but Tiger

Woods’ inability to keep his fly zipped. He provided editoonists with a field day of

opportunities. Dana Summers at the Orlando Sentinel did one of the best, in our view,

and we’ve posted it hereabouts. It cobbles up all the essential imagery in memorable

visual pun; can’t ask an editorial cartoon to do more than that. On the same subject, a Denver Post columnist, Ed Quillen, observing that Tiger is losing endorsement revenue, goes on to report that Tiger’s agent might be looking for replacement sponsors among brands of condoms. Oh—and not to let the subject wander off unheralded—New York City is sponsoring a contest for the design of the wrapper for the city’s next official condom. The winner will be selected by online voting at nyc.gov/condoms. The intention is to encourage safe sex, but “official condoms”—sounds a trifle like government intrusion into the boudoir to me. What if the winning design incorporates a microscopic chip so someone somewhere will see—well, what do you see from the blunt end of a condom? Could be this is another of those things we don’t need to worry about. ***** Our Editorial Cartoon Exhibit this time (above) includes a couple telling comments on the enhanced military action in Afghanistan. No one thinks this is the right thing to do; it may be, as Baracko Bama says, only the best of numerous bad alternatives. Jimmy Margulies conjures up a haunting image of our exit strategy in action in Vietnam, a clear allusion to a forthcoming quagmire; and Tony Auth’s escalator, while aiming for an Exit, seems to be forever going up, never down, another irony. But it was the editorial in the Santa Cruz Comic News that hit me hardest. Written by co-publisher John Govsky, here’s the whole thing (in italics): A Democratic president, stuck in a war going badly on the other side of the world, ponders what to do. He wants to expand social programs and help Americans in need, but he knows spending the treasury on an overseas war will make this harder. After listening to his trusty advisors, he makes a fateful decision, one that will eventually doom his presidency. It’s July 18, 1965, and Lyndon Johnson addresses the country: “I have asked the commanding general, General Westmoreland, what more he needs to meet this mounting aggression. He has told me and we will meed his needs. I have today ordered to Vietnam the air mobile division and certain other forces which will raise our fighting strength from 75,000 to 125,000 men almost immediately. Additional forces will be needed later. And they will be sent as requested.” Today, President Obama, in an eerily similar quandary, reacts in the same way, ordering another 30,000 troops to join the almost 70,000 now in Afghanistan. Have we learned nothing? What was Bush’s war has just become Obama’s war. I hope it will not follow the path of Johnson’s war. RCH again: I still say the way out is to buy our way out. Do as we did in Iraq: hire

warlords to establish and preserve order (and to refrain from shooting at us). Or to do

as Bill Mauldin suggested in the title of a 1985 book of his cartoons: Let’s Declare

Ourselves Winners—and Get the Hell Out! As you can tell from the picture of the dust

jacket near here, Mauldin put those words in the mouth of a Russian dogface who was

holed up in (yes) hostile Afghanistan. That’s exactly what the Russians did—they got

the hell out—and it’s what we’ll eventually do, too, regardless of what actually transpires

in the Afghanistan hinterlands. O’Bama’s plan has been widely denounced by the Grumbling Old Pachyderm because it announces a departure date. The GOP reasoning, however, is based upon military strategy: don’t tell the enemy what you’re thinking. But O’Bama is applying political strategy here: warn your opponent by telling him what’ll happen in the expectation that he’ll plan accordingly. The politicians being addressed are Hamid Karzai and his cohorts, not the insurgents or the Taliban. Those lawless hoodlums won’t change their behavior. Some of our esteemed leadership worries that these outlaws will simply “lay back” until after July 2011, the announced departure date, and then, when we’ve been lulled into leaving, they’ll resume nastiness. But laying back and awaiting our departure doesn’t serve the interests of the Taliban and its adherents. One of the Taliban objectives is to regain control of the country by terrorizing the citizenry into accepting them again; that won’t be achieved if they lay back for months. The other objective is to prove they can stand up to the military might of the U.S. and its allies—and survive. That objective won’t be served by laying back either. So why warn Karzai and his crew? My guess is that the idea is to induce them to get their houses in order—establish whatever safeguards and alliances they need to survive after the Western powers leave. We’re not talkin’ “democracy” here; not even corruption-free administration. Just self-preservation. If Karzai and his crew can manage to survive our departure, we may not have left Afghanistan a democracy, but there’ll be a government of some sort, something to hold the so-called country together. And that’s probably the best we can do. *****... Last time, in our frenzied assessment of the state of newspapering in the U.S., we assembled a few more illustrative exhibits but failed to post them. Here they are.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution From Ellen Goodman, syndicated columnist: “Let it not be said that right-wing bloggers are encumbered by a sense of humor. Or a fact-checker.” The widely circulated allegation that Barack Obama’s book Dreams from My Father was written not by Obama but by William Ayers “was about as true as the drive-a-stake-in-the rumor that Obama had been born in Kenya. New Yorker magazine ranked that fantasy as somewhere between ‘a belief in Santa Claus and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.’ ... ‘Truthiness’ has exploded alongside a new media that is decidedly not mainstream, that flows into as many rivulets as they are cable channels, points on the radio dial and unvetted bloggers. It’s now possible to find a group somewhere in Googleland that will agree with anything. Any outlier can find a tribe and a ‘fact’—Global warming is a hoax! Evolution is a fraud!—that reinforces his belief. There is a sense that we don’t need science or editing or fact-checking as long as we have crowd-sourcing. We don’t have to build opinions on facts; we can build facts on opinions.” CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. I loved you in the morning, Our kisses deep and warm, Your hair upon the pillow Like a sleepy golden storm. Lyrics from “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” by Leonard Cohen; quoted by Newsweek reporter Maziar Bahari as one of the things that kept him going during his captivity in Iran, but good for us all, any time under any circumstances. ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY The Thing of It Is ... I’m still trying to figure out what “debate” means in the U.S. Senate. The debate doesn’t advance legislation at all. A bill reaches the floor for a vote only after the alleged “leaders” have determined that they have the votes to get it passed. Votes are drummed up in cloakrooms and alleys where Senators and Other Interested Parties horse-trade for votes: you vote for my bill, and I’ll vote for yours—regardless of whether either of us thinks the other’s bill is worthwhile or not. So the “debate” on the floor of the Senate is an exercise in showboating, a monstrous time-waster, and a delaying tactic designed to impede the legislative process not to inform it. Adherents of the Grumpy Olde Pachyderm keep saying the delaying tactic is just fine: we wouldn’t want to rush into anything, they say. Funny thing is: the last time we rushed into medical care, Congress passed the GOP Bush League prescription drug bill, which proved improvident in the extreme. “Debate” pretty clearly means “delay.” That, and publicity for the “debater,” who hopes the voters back home will be persuaded to vote for him/her next time because of the earnest convictions he/she is confessing to in the well of the Senate. ***** The Grouchy Olde Pachyderm, known in these trying times as “the Party of No,” is no longer participating in government. The art of politics is compromise saith the Olde Saw; and these guys don’t compromise. They sulk. And they do naught else that I can discern. We should stop their paychecks: if they aren’t participating in government, they’re not earning their salaries. Don’t pay ’em. How can these guys show up with a straight face on tv and pretend they are conscientious law-makers when (a) they haven’t introduced any legislation as an alternative to the Dems’ health care reform and (b) all they do is make up frightening stories about the disasters that will befall us all if even a shred of Obama’s plans are enacted. Frighten and distract, frighten and distract. Cut off their pay until they grow up. BOOK MARQUEE XMAS LIST: BOOKS FOR A MERRY YULE :: PART TWO Here Are Some I Thought Highly Enough Of To Put in My Liberry (Even, Sometimes, Without Having Actually Read Them All the Way Through. Yet.) You probably won’t peruse the reviews below in time to get them on your spouse’s list of Things You Want To Find in Your Stocking on Christmas Morn—we’re perpetually too late with Part Two of this Anyule Bookwish List for that—but now, after scrolling through the reviews, you’ll know how to invest the money your mother-in-law gave you in lieu of an actual Xmas Gift. But before you make your final choice, you might want to consult the list of books offered in my Monster Book Sale, a posting only a month old so far, which means almost everything listed is still available—new, old, rare, and extraneous titles galore; click on Books at the left. Now, without any more folderol, here are some more book reviews, short and long. ***** Occurring last summer, The 40th anniversary of the first San Diego Comic-Con prompted the publication of a history of the Con, entitled, not at all coincidentally, Comic-Con: 40 Years of Artists, Writers, Fans and Friends (208 10x10-inch pages, color, slick paper; hardback, Chronicle Books, $40). Written by Gary Sassaman, who operates publications for the Con these days, and Jackie Estrada, who was around for the very first and is still very active in the operation, the text is remarkable, perhaps, in avoiding disputation about who started it all. The origins are described pretty much as Scott Shaw! and I, relying a lot on Scott in the obit for founder Shel Dorf (Opus 251), have rehearsed it. Elsewhere in this opus, we allude to the considerable role Ken Krueger played in the first few Cons; he’s mentioned in the anniversary tome but not much, not as much as the obits and tributes lately have suggested he should have been. Apart from mentioning various people who were involved in staging the first Cons, the text avoids naming too many names for the ensuing years: the apparent object is to convey the impression that the Con come into being as a happy convergence of the dreams and delusions of sundry “fans and friends”; the authors aren’t credited until the last pages of the book, where they are listed with numerous others of the Con’s factotums. A nice restraint, and laden, I submit, with exactly the meaning I’ve just attached to it. The text in the book is fairly limited as well as constrained. The volume is mostly pictures—drawings, program cover art, and photographs of the famous and soon-to-be-famous who populated the Con over the years. It also includes lists of the special guests, Con by Con, and of the winners of various awards. A tidy compilation and a valuable historical record for anyone who didn’t get the souvenir program last summer. The book racks in book stores these days are stuffed with tomes about zombies and vampires and the other undead. You can buy an Army “manual” about how to combat zombies, f’instance; and another about how to recognize one. The book that caught my eye was Zombie Notes: A Study Guide to the Best in Undead Literary Classics (200 6x9-inch pages, a few pictures—generic spot illos—but mostly text; paperback, Lyons Press, $14.95) by Laurie Rozakis, a professor with over 100 books to her credit, some of which, judging from the titles, are like this one—a send-up of their subjects. Within these pages, we find revealed the presence of zombies in “Hamlet,” “Romeo and Juliet,”and other classics. Their otherwise mysterious actions and symbolisms are explained. The Renaissance, otherwise a stew of revived literary and artistic endeavors, was also awash in zombie attacks. So numerous were they that the period was known as the “Black Death” (a term that is usually applied to a period somewhat earlier than the Renaissance—but we’re having fun here, kimo sabe, not taking a quiz). Romeo was a zombie; Juliet was not. But balconies in those days were, we are assured, useful for throwing zombies off of to their deaths. And so the “balcony scene” between Romeo and Juliet acquires a new and fraught significance. Visiting Borders the other day, I saw a copy of The Playboy Cartoons fo r$19.99, a replica of the 2004 Playboy 50 Years Cartoons edition that appears to be exactly the same except for a more ornate cover and endpapers; a bargain not to miss. Eureka Productions in Wisconsin has produced over a dozen Graphic Classics (140-plus 7x10-inch page paperbacks, b/w; $10 each from the website, graphicclassics.com, an unusually informative site—detailing, for each title, the contents and artists), each volume entitled with the name of the author whose stories are featured within: A. Conan Doyle, H.G. Wells, H.P Lovecraft, Mark Twain, Jack London, Ambrose Bierce and more, interpreted by a long list of cartoonists, including a few of my favorites—Rick Geary, f’instance, and Hunt Emerson and Roger Landridge and Milton Knight, about whom I have wondered what became of. (He is apparently animating in California.) I have the Edgar Allan Poe volume before me—a collection of his tales illustrated by Geary, Knight, Langridge, Matt Howarth, Pedro Lopez, Lance Tooks and other luminaries. Stunning black-and-white work for the most part by people we don’t see enough of often enough. ***** In Masterpiece Comics (64 9x12-inch pages, color; hardcover, Drawn and Quarterly,

$19.95), R. Sikoryak demonstrates, once again, his uncanny ability to ape the drawing

style of any cartoonist you might care to name. Chic Young, Jim Davis, Al Feldstein,

Bob Kane, Winsor McCay, Ken Ernst, Charles Schulz. Sikoryak is not quite a

reincarnated Will Elder, but he’s close. In this collection of short pieces, we find

Blondie and Dagwood in the Garden of Eden, Garfield playing Mephistopheles,

Bronte’s Wuthering Heights enacted as if it were an E.C. horror comic—The Crypt of

Bronte (Sikoryak may think he’s imitating Jack Davis, but over several pages, it looks

more like Feldstein’s stiff renderings to me), Batman as “Raskol” in Crime and

Punishment, Little Nemo as Dorian Gray, Mary Worth as Lady MacWorth, and Charlie

Brown as Kafka’s Gregor Samsa. But it’s more than simple parody: As Glen Weldon

observed at npr.org, the comic comments on the classic and vice versa. Nemo’s portrait

degenerates in the attic and the little kid, looking like an angel, goes about committing

crimes against humanity: like Dorian, Nemo is too good to be true; like Nemo, Dorian is

living in a dream world. Ziggy is a perfect Candide, the extreme naivety of each indicted

by the other. Batman, the avenger, is as guilty of criminality as those he attacks. (And,

as an added fillip, when Robin shows up, it’s clear the character is female, wearing a

skirt and lipstick—just as Fredric Wertham fantasized.) When Blond Eve eats of the

forbidden fruit, she and her hubby are condemned to a life in American suburbia, the

modern version of the non-Paradisiacal. Oddly, Blond Eve in the Garden is nude but

nipple-less, displaying a strange delicacy in a strip where naked Dagwood’s pecker is

on full display. The longer pieces—the Bronte EC parody, Little Lulu in a send-up of The Scarlet Letter, and, even, Batman as a Dostoyevsky ***** Grown-Ups Are Dumb (No Offense) (100 6x8-inch pages, b/w with second color; paperback, $8.99) is Alexa Kitchen’s second book. Her first, a how-to volume entitled Drawing Comics Is Easy! (Except When It’s Hard!), appeared about five years ago, published by her father, Denis Kitchen. It was surprisingly successful (her debut at the MoCCA book fair in New York City was described in Publishers Weekly [7/12/04] as ‘the talk of the show’), earning Alexa nominations in both the Harvey and Eisner competitions, and a contract with Disney’s Hyperion Books, publisher of the second tome, which, in cartoons and comic strips, explores (it sez here) “childhood fantasies and traumas, finding the funny in everything from cleaning one’s bedroom to eating ice cream to torturing boys.” The work collected herein was drawn and doodled when Alexa was between 9 and 11 years old; she was 12 last summer when the book was published. The quality of the artwork is at least comparable to what we see in Pearls before Swine and Cathybert and their ilk—not to mention the mature William Steig, who earned art gallery encomiums with his primitive stylings. Some of Alexa’s drawings are remarkably sophisticated, laminated with shading and texturing; others deploy a much simpler outline style with no shading. But the astonishing thing about the collection is how expertly Alexa exploits the resources of the medium: she has clearly mastered comedic pacing, and she understands the vital role of pictures in a visual/verbal medium. She is, in short, a cartoonist—just as the book’s cover says. Her father assures me (he swore to it, actually) that he has absolutely no part in the production of these cartoons: Alexa resists any such participation, calling it interference. And on the reverse of the book’s title page, she thanks him “for not butting in with dumb changes.” She hasn’t decided on cartooning as a career, she told Gary Chun at the Honolulu Star-Bulletin: “Right now, it’s mostly a hobby for me,” she said, “but I might still do this when I grow up.” Her mother, Stacey, whom Chun interviewed, said it took about a year-and-a-half to accumulate the book’s content. “She constantly draws, writes and doodles. When we thought there was enough good, interesting stuff, we set it aside, which made for a large pile of material for the editor to go through.” She continued: “As she’s maturing, Alexa is exponentially getting better as an artist. She now has an interesting perspective of the world, and she has a lot to share. I try to walk a fine line between supporting what she does and not wanting her to be overexposed to the public. She’s still a rather shy and introverted person, and while she’s willing to talk about her book, Alexa doesn’t need her ego to be stroked. She’s not in this for the accolades but for the purity of expressing herself through the medium.” Despite being proclaimed “the world’s youngest professional cartoonist” by the cover of the book, the question persists: will she eventually make a career of cartooning? Stacey Kitchen supports her daughter’s evasiveness, telling Chun that when she asks Alexa about it, “Alexa usually replies, ‘Mom, I don’t have to decide now!’ —and I want her to feel exactly that because I want her to enjoy just being a kid now.” A kid with a website, alexakitchen.com, where we learn that she fills about 100 pages of foolscap a week with doodles and drawings. On one of the site’s pages, Stacey provides a mother’s perspective on a daughter’s artistic maturation: “Roughly at around the time Alexa turned five, Denis and I noticed a change in her work. While the art was still completely unrefined and absolutely still childish, it did surprise us in that it showed signs of some older sophistication. Her roads would get smaller as they wound around in the distance. Books and other square objects were no longer drawn flat. Instead, they were all cubed and had dimension. Rooms had intricate spatial layouts. Objects in the foreground were bigger than the objects drawn behind them. Fingers and hands actually bent around the objects they were holding. Here character's faces, especially the eyes, revealed and expressed true emotion. Alexa was creating images on art principles that she had not yet been taught. She just instinctively knew how to do it. And she did so in one well thought-out draft—in pen—with no preliminary pencil guides. Denis and I think she's pretty special, but (like all other parents) only because she's ours. Her ‘art’ is just her way of dealing with the reality of her life—just like other children. She draws what she sees and how she feels about it. ... Like most children, drawing is cathartic for her. She just happens to be especially good at it.” Elsewhere on the site, we encounter this speculation: “Genes may be a factor in Alexa's talent and early professional development. Her mother Stacey was a child performer in the country music field, having both recorded original tunes and performed on stage since the age of 6, and her father Denis began his career as a cartoonist before morphing into a publisher.” **** IDW’s Library of American Comics continues to grow apace: the newest arrival is Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby, The First Modern Detective: Complete Comic Strips 1946-1948 (314 10x11-inch pages, landscape, b/w with some color; hardcover, $49.99). Tom Roberts, Raymond’s biographer (see Harv’s Hindsight for May 2009 for a review of both his book and Raymond’s career), supplies some appreciative introductory words about Raymond’s skill as an illustrator, and comics historian Brian Walker provides biographical details in his Introduction. Raymond’s Rip Kirby strip has never, to my knowledge, been reprinted with anything like the quality control its drawings warrant. Pacific Comics Club published a series of thin but large-page Rip Kirby booklets in the 1980s but was forced to use proofs from somewhere overseas, requiring that the speech balloons be relettered in English; that was done clumsily, blemishing the appearance of the strips. And the reproduction of the artwork, although of high caliber, failed to capture Raymond’s distinctive fine-line rendering. IDW has come closer, much closer: this is probably the best we’ll ever see Rip Kirby reproduced. Still, as series editor and designer Dean Mullaney notes, the quality of the King Features syndicate proofs varies, and the variance shows. Fortunately, it doesn’t show all the time everywhere: many strips are as pristine in this book as they were when Raymond turned them in. The book itself is an exquisite production—decorative flashes of color in the introductory pages, stunning jacket design, panoramic endpapers, and even a stitched-in bookmark ribbon (this last, an IDW signature). Luckily for us all, the strip’s opening week—one of the best in comics history—as well as much of the first adventure are reproduced with gratifying accuracy. But about halfway through the first sequence, we begin to get occasionally muddy, blotchy reproduction. Happily, the stories, which, thanks to Roberts, we now know were concocted by Raymond and his editors at King, are mature and suspenseful enough to hold our interest until the quality of the art resumes. Raymond began experimenting with rendering techniques before the end of the strip’s first year. In November 1946, he was using a brush to draw, not a pen, which had imparted to the first months of the strip its distinctive crisp aura. He was back with a pen by the fall of 1948, but within the next six months (which will be published in Volume 2 of the series), Raymond was deploying a brush again, giving his art a liquid line very much in the mode of Leonard Starr in On Stage. Eventually, Raymond would abandon the brush for all but shadows and wrinkles in clothing, and by the fall of 1950, he was drawing almost the way he drew at the beginning. In practice, he drew with a pen—outlining faces, figures, background details; then he embellished with a brush, slathering in fat black strokes for wrinkles, shadows on accouterments, and so forth. That, however, won’t be apparent until you pick up Volume 2, which will carry the continuity into 1951. In Volume 2, we’ll watch Rip get discombobulated when his paramour, toothsome model Honey Dorian, is pursued by a handsome young chap with marriage on his mind. By the end of this adventure, we know, but Rip doesn’t, just how Honey stands in respect to him and his casual attentions. The tale unravels at the guy’s plantation in the South, a place called Blackwater. Could be in South Carolina; sinister stuff. ***** To drop the other shoe, the first of which, a review of Mark Bryant’s World War I in Cartoons, we flung across the room in Opus 244, here’s his World War II in Cartoons (160 9x12-inch pages, b/w and color; Gallery Books, no price I can see but probably available for pittance on the Web; see AddAll). As with the previously reviewed tome, this is mostly British and European cartoons and posters. Bill Mauldin’s Willie and Joe are on the cover and appear five more times within; and Dave Breger’s G.I. Joe displayed in three cartoons, but George Baker’s Sad Sack is nowhere in evidence; ditto, Dick Wingert’s Hubert. The British strip-tease, Jane, shows up, but none of the legions of American newspaper strips, from Terry and the Pirates to Tillie the Toiler, whose characters went into uniform for the duration. The cover of one issue of Speed Comics (displaying a pugilistic Sentinel) makes it into the tome, but none of the other U.S. comic books, whose characters struggled against the Axis more strenuously than political cartoonist David Low’s Colonel Blimp. Low is extensively represented herein, but his famously infarmous Colonel Blimp, the pompous personification of paradox and plain self-contradiction (who insisted, for example, that even if the cavalry were mechanized, the troops must wear spurs in their tanks), shows up only a couple times, not enough to adequately suggest the impact the creation hand on English readers. Arthur Szyk, a Polish artist who moved to the U.S. in 1940, is also in ample evidence, but his work scarcely represents the quantity of U.S. magazine covers devoted to the war effort. Too bad. The book is organized by year, and the text briefly relates the major events of the war as they transpired. But be wary: Bryant thinks 138,000 British troops surrendered at Singapore, but that’s probably high; other sources put the number between 80,000 and 100,000. Despite the book’s shortcomings, if you want samples of European cartoonists’ WWII efforts on your shelves, you should add this tome to your collection. SENIOR HEALTH CARE SOLUTION This came floating in on the Internet last week: So you're a senior citizen and the government says no health care for you, what do you do? Our plan gives anyone 65 years or older a gun and 4 bullets. You are allowed to shoot 2 senators and 2 representatives— Republicans or Democrats, it doesn’t make a difference. Of course, this means you will be sent to prison, where you will get 3 meals a day, a roof over your head, and all the health care you need. New teeth? No problem. Need glasses? Great. New hip, knees, kidney, lungs, heart? All covered.. And who will be paying for all of this? The same government that just told you that you are too old for health care. Plus, because you are a prisoner, you don't have to pay any income taxes anymore. Is this a Great Country, or what?! LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status Eddie Campbell returns in The Amazing, Remarkable Monsieur Leotard (128 6x9-inch pages, color; paperback with flaps, First Second, $16.95) giving whimsical pictorial life to a story by his co-author Dan Best. Monsieur Jules Leotard, “the original young man on the flying trapeze” distinguished for his deeds (including, on the first page, emptying “his fortitudinous bowels”) and his “imposing resplendent mustachios,” dies on page 12 of this graphic novel, which nonetheless forges ahead by focusing on the doings of Monsieur Leotard’s nephew, the “useless Etienne,” to whom Jules has bequeathed a false moustache that has been pressed between the pages of a book that is entirely blank inside, the book itself, and “the blessing of a dying man,” i.e., Jules, whose blessing, apparently, is “may nothing occur”—in the life, we assume, of Etienne. Etienne joins the troupe of which Jules was a member—a happy band that includes a dancing bear that talks, a tatooed woman, an India rubber man, and a strong man, among others—and they wander around Europe in the months preceding the sinking in April 1912 of the Titanic, which occurs on page 106-7 (a spectacular watercolor two-page spread), enjoying, as it sez on the title page, “typographical acrobatics and illustrational feats in an ideal production of entirely new tricks, statuesque acts, and performances.” That supplies a nearly adequate preview of the sort of conceit, narrative and pictorial, that animates the volume, which includes, in addition to the sinking of the Titanic, a trial in which one of the troupe is charged with stealing the Mona Lisa. Campbelll’s style herein is a continuation of the watercolored line-art manner he displayed in an earlier exposition, The Fate of the Artist (96 6x9-inch pages, color; paperback with flaps, First Second, $15.95), an autobiographical “investigation” into the author’s disappearance. Both books are more rewarding to the reader who finds his pleasures with such tomes in the manner of their presentation rather than in their substance, the storytelling techniques of cartooning rather than the story itself. In Leotard, the narrative transpires in fits and starts—or “episodes,” as the book self-consciously calls them—between various visual impersonations of such things as circus posters and pages of newspaper articles. The march of sequential panels seems a somewhat dotty albeit deliberate improvisation: the panels occupy only about two-thirds of the pages, the rest of the space is devoted to decorative marginal visual caprices that are sometimes informative (in the manner of, say, footnotes) and sometimes functional (when the characters depicted seem to be commenting on the action of the panels above, or below, them). The volume as a whole is exactly the sort of amusing quirky performance you’d expect a cartoonist to turn in when he lets his visualizing imagination ruminate on the personalities and incidents at hand. In one sequence, Campbell presents seven successive full-page pictures of Etienne asleep in bed as viewed from the ceiling; Etienne tosses and turns, becoming increasingly entangled in the bedclothes, while in the margins, Jules and Etienne appear in tiny miniature, discussing the novel so far, its potentialities as well as the possibility of abandoning it and moving on to another perhaps more worthwhile novel. “This book is only half done,” says one of the tiny figures (perhaps Campbell himself; he’s too tiny to be sure, but he’s wearing glasses and stands near a drawing board from which a trapeze with Jules in it is swinging), to which the other says: “This is one of those characters that writes his own story. You can’t force it.” (Probably that be-spectacled figure is Campbell.) I take particular (if perverse) delight in the first double-truck in the book, a depiction of Leotard flying between trapezes as the crowd looks breathlssly on, drawn in the stiffest style of Richard Doyle, the Victorian cartoonist who drew the perennial cover of Punch magazine; Doyle could make much more subtle drawings than Campbell is imitating here, and Eddie once lambasted me for not knowing how much better Doyle could draw and assuming his stiff style displayed the entire range of his artistic abilities; it didn’t. And doesn’t. So I think Campbell is laughing at me with this picture; that, however, is the delusion of the egomaniac that I usually am. The book ends as delightfully as it has transpired. The circus is in Cleveland, and Etienne, now an old man but capable of creating the illusion of youth, dons blue tights and a red cape for his performance, and in the audience, a kid named Joe is drawing a picture of the man on the flying trapeze. “Wow!” says the kid sitting next to the young artist, “—that gives me an idea!” The last page in the novel is painted to look like a slightly crumpled piece of paper; on it are the words: “Nothing occurs on this page.” For anyone who loves cartooning (and if you don’t, what are you doing at this website?), Monsieur Leotard is a treat, brimming with visual occurrences on every other page. ***** THE IDEA OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL. Eddie Campbell, famous, lately, for illustrating Alan Moore’s monumental From Hell, acquired his initial celebrity for the Bacchus series of comic books and, subsequently, for four issues of the autobiographical Alec series. I’ve never been a particular fan of Bacchus because I have never warmed up to a character with eyes all over his face, but the Alec series is somewhat more satisfying, and all four books have been re-issued in a single volume, Alec: The Years Have Pants, by Top Shelf. Alex Dueben, a guest contributor to comicbookresources.com, interviewed Campbell in October, asking, among other things, whether, since so much of his recent work has been autobiographical, Campbell keeps a journal (what in the Olden Times was called a “diary”). Campbell said, “Not exactly, but the answer is probably yes, more-or-less.” Dueben then asked if Campbell thought his Alec books were the first autobiographical comics. Said Campbell: “A couple of people had drawn themselves into their work in a scattershot manner. Crumb, Speigelman. Pekar was doing it, but I didn't see his work till later. But I don't think anybody had attempted a long-form work in autobiographical mode, or at least I hadn't encountered it.” The new omnibus reprinting of the Alec stories, which includes one new story, was, for Campbell, “the next logical evolutionary step. When we first started making comics on a colossal scale, we had to do it piecemeal, releasing the work in periodical parts [because] there wasn't the financial machinery in place yet to pay an artist to disappear for several years to do the work, like you have in the mainstream book trade. That was the second step. Now we have a third step, where several books by an author are gathered into a huge compendium. We've seen it with Eisner and the Hernandez brothers, and the big ‘Absolute Sandman.’ Also, at least one of my [Alec] books had been out of print for some time, so a new presentation of the work was due. I was surprised how much of it there is. I had to do a lot of tightening up and trimming to get it down to 640 pages.” Campbell said he included a new story in the compilation because “it has always

been my way to use the rounding up of older work as the justification to make new

work. Economically, it's a useful way of doing things. If I could raise a couple of

thousand bucks as an advance for something like ‘Doing the Islands with Bacchus,’

then I'd see that as payment for drawing ten or so new pages. In this way I have always

stayed in work and continuously added to my inventory. As another example, the Alec

book, How to Be an Artist, was first serialized in fourteen issues of the anthology DeeVee. When I gathered the parts together to publish them myself, I took the

opportunity to expand the work by twenty-five new pages. And here we are again, with

all of the Alec books rounded up in one volume, it was logical to add a whole new book

to bring things up to date. The new book is thirty-five pages, and, with other additions,

there are about forty-five pages altogether of new material.” “It doesn't really matter,” Campbell said. “You now have a big book in which the author decides to throw away his pseudonym three quarters of the way through. I'm sure you can psychoanalyze it and come up with reasons, or attribute it to an audacious postmodern gambit, but the characters all change their names. It's a bit like Spiegelman admitting he's not really a mouse at the beginning of Maus II. It can't really destroy the illusion of reality since that was never just an illusion in the first place. You can no more fabricate a truth by devious literary tricks than you can deny it by unmasking your scam. The truth is independent of all that. You know it when you hear its ring.” Sometime in 2010, Campbell has a new book coming from Top Shelf, The Playwright, which, he told Dueben, is “about the sex life of a celibate middle-aged man.” But while he’s doing new work, Campbell said it’s getting harder for him to “start up something big. I really don't know if I would have the resolve to do something again on the scale of those other works. It's the kind of thing you can manage in your forties. I don't think we'll be getting another Maus from Spiegelman, either. There's a time in your life when you're up for something like that. Impossible to replicate the frame of mind later. I think I'll probably add another ‘book’ or two to the Alec opus, and there'll be a bigger version of that further down the line.” Said Dueben: “You've been writing on your blog about the nature and meaning of the ‘graphic novel’ and Monsieur Leotard felt as if that was where a lot of what you'd been working out was fully expressed in terms of ignoring the language of comics, and instead utilizing illustration tools and typography to create a new kind of graphic novel, more of an ‘illustrated book’ than is typically seen.” Campbell agreed: “Well, that was the original idea of ‘graphic novel’ before all the dullards of the comic book world decided it just meant a format. It was about the ambition of trying to do something grand and memorable with the simple elements of the comic strip. Like any language, it can be prosaic and utilitarian, or you can craft its phrases into lines of haunting beauty.” Back near the Dawn of Time, I, too, thought “graphic novel” meant something more than “a long comic book between cardboard covers.” A graphic novel ought to exploit the visual and verbal resources of the comics medium in new and more elaborate ways, I thought. Alas, both I and Campbell have been proved mistaken in our expectations by (as he says) the “dullards” who want to make money with comics not aesthetic history. ***** You’ve never seen—and you’ll probably never see again—anything quite like Greg Houston’s Vatican Hustle (132 6x9-inch pages, b/w; NBM, paperback, $11.95), an outrageous, over-the-top send-up of blaxploitation movies of the early 1970s. In a raw explosive succession of pages that violate most of the conventions of narrative rendering—close-ups too close and too often to carry the narrative visually, captions grossly lettered, facial and other anatomy exaggerated and distorted beyond easy recognition, speech balloons drifting away from their moorings in panels in which their speakers speak, raggedy lettering clawing its way across the pages—Ralph Steadman doing Basil Wolverton, you could say (and the NBM publicity does)—Houston tells the story of Boss Karate Black Guy Jones, a hulking private eye who is hired to find the crime boss’s missing daughter, a quest that “tailspins from the ridiculous to increasingly abject absurdity,” including an encounter among bickering hobos in the park. Black Guy Jones rescues the daughter and then, on an errand to the Pottery Barn to find an ecru carpet to replace the one in his digs that the crime boss’s minion messed up, encounters an old flame with whom he exchanges double entendre amid mutual gawfawing.

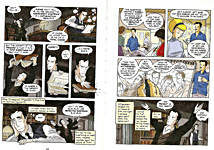

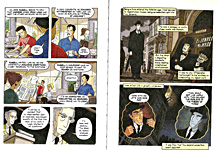

The crowning absurdity is that it all makes sense—in its own bizarre and twisted way. In short, a visual and verbal delight. The 43-year-old Houston, by the way, won a Best Actor Tony in 1972 for his role in “Musical for Pippin,” occasionally teaches illustration at Maryland Institute College of Art, indulges passions for hobo fighting and ritualistic sacrifices, and “enjoys blaxploitation films, women with lengthy prison sentences, and fire” (and that autobiographical footnote will hint at the linguistic and conceptual excitements you’ll find in this volume). ***** In Adrian Tomine’s 2007 Shortcomings, now in paperback (with flaps, 112 6x9-inch pages, b/w; Drawn & Quarterly, $14.95), he continues to indulge his fascination with love and alienation, this time rooted in interracial dating. His Asian American protagonist, Ben Tanaka, is living with an Asian American girl, Miko Hayashi, who suspects, correctly, that Ben harbors a desire to be shacking up with white girls. When she leaves him in California to take a job, temporarily, in New York, he indulges his heretofore thwarted desire, but when that doesn’t work out, he takes a trip to New York to see Miko, who, he discovers, has a new boyfriend, a white guy. They quarrel one last time, and he returns to California without Miko, their relationship, which had been on shaky ground for a long time, destroyed. Tomine takes more than 100 pages to tell this tale because, as usual, he explores every nuance of the characters’ feelings and motivations, putting them all on display either in their actions or in their arguments or conversations. Tomine’s pictures are as fastidiously rendered and as exactingly paced as the examination of the psychology of his characters is meticulous: the portraits are of-a-piece, each a finicky echo of the other. This sort of microscopic storytelling is engaging, absorbing, for both Tomine and his readers, but I’d like to read something else by him that doesn’t feature badly flawed personalities, like Ben’s. Or, if a flawed personality, one that learns from his experiences, and I’m not sure Ben does here. It’s tempting to suppose that this story has autobiographical roots in the life of its creator, a fourth generation Japanese American; or that he was inspired to do the story by the success of Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese, which came out the year before Shortcomings was first published in hardcover. But such speculation is idle in the extreme; I mention it only to discourage it. ***** AN UNANTICIPATED TRIUMPH. Being on a list of the ten best-selling comics doesn’t invariably proclaim the quality of the product—usually, alas, it doesn’t. So when I saw Logicomix ranking fifth on the Publishers Weekly list in early December, I was not just surprised: I was astounded. And my astonishment doubled when, a week or so later, I saw the book in Time’s list of the Best Books of 2009, non-fiction division. Subtitled “An Epic Search for Truth,” this graphic novel (348 9x6-inch pages, color; paperback with flaps, Bloomsbury, $22.95) takes up a highly unlikely subject for treatment in a form best suited to depicting action rather than thought—logic and philosophy. Logicomix rehearses the early life of philosopher Bertrand Russell as he tries to ascertain the logical foundations of mathematics. We see Russell in confrontation and conversation with other great mathematicians of the first decades of the 20th century—Georg Cantor, Kurt Godel, David Hilbert, the mad Gottlob Ferge, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and others, including, mostly, Alfred Whitehead, with whom Russell co-authored the influential but controversial Principia Mathematica while contemplating (and perhaps consummating) an affair with Whitehead’s wife. Except for the last item, this seems a recipe for boredom in a visual narrative like comics, but the authors of this extraordinary volume not only make the subject interesting but do it by adroitly exploiting the capacities of the medium. The biographical part of the book is framed by a 1939 lecture Russell gives in which he recounts his life and philosophical quest—a device that, like the book’s subject itself, is fraught with potential tedium. But the academic drone of Russell’s pontifications is broken up by flashbacks depicting key aspects of his life, including silent sequences that enhance the drama of certain events, symbolic passages of explication or of psychological insight, and, most surprising, sight gags—plus Russell’s own occasional low-key sense of humor. The book is written by Christos Papdimitriou, a professor of computer science and author of the Turing: A Novel about Computation, and Apostolos Doxiadis, a pioneer in the study of the interaction of mathematics and narrative whose international bestseller Uncle Petros and Goldbach’s Conjecture “was the first novel to make fascinating fiction out of mathematics” (as the back flap blurb tells us). Rendering the story into pictures are the husband-and-wife team of Alecos Papadatos, an animator and newspaper cartoonist in Athens, and Annie di Donna, who, since 1991, has been running an animation studio with her husband. The book is shaped by three narrative strands that weave in and out of each other: (1) Russell’s lecturing (which is autobiographical as well as theoretical), (2) Russell’s life story as he relates it in his lecture (a story that can be broken into two elements: his pursuit of the logical foundations of mathematics and his personal life, marriage, love affairs, intellectual struggles with colleagues, etc.), and (3) discussions among the book’s authors about aspects of Russell’s life and quest. For an instance of this last—the authors interrupt Russell’s recitation of his life story (and Papadatos and di Donna’s illustration thereof) when Russell says he’s failed to achieve his objective with the Principia Mathematica: Papadimitriou objects to saying that Russell failed; but di Donna reminds them all that they are using Russell’s words. Doxiadis finds a way out of the dilemma by inserting into the narrative an episode that, in effect, redeems Russell from himself. This is complicated stuff, but the authors pull it off with panache. In the four pages that I’ve posted in this vicinity, we go from Russell’s lecture (which, at the moment, is autobiographical, focusing on his relationship with his pupil, Wittgenstein, always rendered in sepia tones) to the studio (in full color) where the authors are working and discussing this aspect of Russell’s life, back to the Russell lecture/autobiography, then again to the authors’ full-color studio, then, again in sepia, Russell resumes his lecture, which includes allusion to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to explicate Russell’s ponderings.