|

||||||||||||

Opus 250 (Hallowe’en 2009). In the hopper this time, a long essay about serenity and sin in George Herriman’s eternal Monument Valley plus Big Changes at The Comics Journal, another new cartoonist at the Chicago Tribune, Islamic Hoodlums still plotting to kill Danish cartoonists, The New Yorker’s un-serious Cartoon Issue, and reviews of graphic novels Captain America: The Man with No Face and You Have Killed Me, plus Doug Marlette’s classic In Your Face: A Cartoonist at Work. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department: NOUS R US Chicago Tribune expands cartoonist line-up Comics Journal goes online all the time, in print semi-annually Chicago Muslims caught in a plot to assassinate Danish cartoonist Anniversaries and Birthdays: Annie, Asterix, Peanuts, Casper New Yorker’s Cartoon Issue still isn’t serious KRAZY THEME PARK Herriman’s Eternal Monument Valley Is Changing EDITOONERY Visual Metaphors and Imagery in Four Cartoons NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Taboos Violated, Word Play Galore, Comics in Strips, Cameo Appearances, Using the Medium Cornered BOOK MARQUEE Comic Book Classics to be Reprinted at Fantagraphics Nancy, too And Monte Schulz’s novel GRAPHIC NOVELS REVIEWED Captain America: The Man with No Face You Have Killed Me COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Doug Marlette’s In Your Face: A Cartoonist at Work Mister Ron’s Basement

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— ***** WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH My Friend Shel Dorf, Founder of the San Diego Comic-Con, Died, Tuesday, November 3, at about 1:10 p.m., Pacific Time I received the bad news just before sending this issue of R&R off to my webmaster. Shel deserves a thoughtful remembrance and appreciation, not something I’d rush through to make this posting. We’ll have something more here in a day or so. NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits When we dithered, last time in Opus 249, about the advent of zombies and vampires in a couple comic strips earlier in October, we scarcely anticipated the deluge that engulfed the funnies page the week before Hallowe’en. Vampires showed up in Dana Summers’ Bound and Gagged two days running, and zombies invaded Tim Rickard’s Brewster Rocket for much of the week; they were looking, as always, for brains, so when Brewster courageously confronted them, they simply walked (shambled) past him. In The Flying McCoys, the brothers perpetrated a gag about a women driver who was rear-ended because she didn’t see the driver behind her in her rear-view mirror—because he was a vampire. (We had to cogitate about that one a bit.) Zits celebrated “Zombie Week” by listing six reasons that zombies would make cool parents, and Jim Borgman’s rendition of Jeremy’s mother and father as decomposing parents was beautiful in their surpassing ugliness. In Dog Eat Doug, Brian Anderson perpetrated a joke about a vampire bat, and in Pearls Before Swine, Rat, disguised as the hookah-puffing caterpiller in Wonderland, ate all the strip’s other cast members. A zombie joke, surely, the final punchline of which was when the Ratapiller eats Stephan Pastis on Saturday the 31st. Then on Sunday, November 1, the strip revealed that Pastis was actually vacationing in Hawaii all week, and Pearls was being drawn by Rat, who, having disposed of Pig, Zebra, Duck, Cat, and the Crocs—not to mention Pastis—is now, at the end of the Sunday release, planning to devour all of The Family Circus, one of Pastis’ usual victims. Oh, the horror! Jim Davis also celebrated Hallowe’en Week: he took the entire week off by showing Garfield seated in an easy chair in exactly the same position, three panels every day for six days, watching a Dracula movie and making snarky remarks. The October Playboy, by the way, also joined in the ghoulish fun: the cover feature—“Vampire Love: Bloodlust! Why the Undead Are Hot Again”—was entitled “Love Bites” and depicted two barenekidwimmin nuzzling and licking each other hungrily. The popularity of the undead was thereby explained, in both pictures and the accompanying text, as a result of the link between bloodlust and passion, passion always being among the more popular of human endeavors. But that didn’t not end Playboy’s exploration of the phenomenon: “The World of Playboy” included the usual allotment of photographs of the magazine’s editor, Hugh Hefner, the living dead on botox. Meanwhile, in Albany, New York, Max Brooks, self-proclaimed zombie expert, was quizzed by the Times-Union, which, among other questions, asked how he felt about movies that used zombies to provoke laughs or in which vampires tried not to act like vampires. Said Brooks: “I have nothing against zombie comedies. They help spread the word and keep the general morale high. As far as vampires go, well, we know vampires don’t really exist, right?” His explanation for the emergence of the undead as “pretty hot properties in popular culture”: “I think the American people are finally waking up.” THE FUTURE BRIGHTENS The Chicago Tribune, having displayed a nearly hostile attitude towards cartoons for almost a decade, has apparently re-discovered their value: at the end of October, the paper, the largest in the midwest, signed up the last of the nation’s active sports cartoonists to produce a weekly cartoon focused on the antics of the Windy City’s numerous athletic franchises—the Cubs, Bulls, Bears, White Sox, and Blackhawks. The first of Drew Litton’s cartoons, running under the heading The Main Event, appeared Saturday, October 31, in the Trib’s retooled sports section, “Chicago Sports.” Just a month or so ago, the Trib finally replaced its editorial cartoonist, Jeff MacNelly, who died in 2000, hiring Scott Stantis, long-time editoonist at the Birmingham News in Alabama (see Opus 247). Newspaper cartoonists are greatly encouraged by the Trib’s actions: adding cartoons to its content during a time that newspapers generally seem threatened with extinction is seen as a potent endorsement of the ability of cartoons to attract and hold readers. It was a lesson the Trib had to re-learn. The paper had lately demonstrated a cynical indifference to comics with a policy audacious in its duplicity: when it dropped a comic strip from its line-up, the paper told readers who phoned to complain that they were merely “experimenting” and that the strip would soon return. That stilled the complaint. But the Trib never brought back the strip that it had dropped. Cynical, as I said. But by hiring Stantis and signing Litton to a weekly cartoon, the Trib seems to have reformed. Litton, who drew sports cartoons for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver for 25 years, has been freelancing his work since the Rocky died last February. He has maintained a website as a marketing tool, and last summer, he also sent e-mails and sample cartoons around the country to various sports editors, pitching the idea of a locally themed sports cartoon; the Trib expressed interest. Litton is delighted to land the gig: “Chicago’s a rabid sports town,” he told Rob Tornoe in an interview, “—with great teams with really good mascots. Mascots are very important to a sports cartoonist. Da Bears, Cubs, Bulls, Blackhawks. Those are like the greatest mascots of all time. Good manly type mascots.” Litton’s enthusiasm here may seem excessive, but he’s a man who’s found an oasis after a lifetime in the desert: in Denver, except for the Broncos, the teams he drew about offered no visualizable possibilities—Rockies, Rapids, Avalanche. Rocks, water, and snow. Banal. For at least as long as I’ve known Litton’s work—since the mid-1990s, when I

interviewed him—his cartoons have been different from the traditional sports cartoon,

which, as established by the great Willard Mullin, boosted sports by spotlighting

particular athletes:typically, Mullin declared his subject for the day with a large

realistically rendered portrait of an athlete; and then he developed his story—an

observation or comment on the athlete’s most recent accomplishment—in a series of

small figures (sometimes called “goomies”), often caricatures of the principal subject, in

topical vignettes that surrounded the large picture. Sometimes the large drawing

depicted generic athletes of a particular sport, and Mullin’s commentary explored the

state of that sport or some aspect of the news about it. Sometimes his cartoon took

shape as a series of narrative pictures in comic strip form. A sports cartoon, Mullin once

wrote, should “tell a story, get over a point, cover some news, or bring a laugh.” On a

good day, he said, he’d get all four in one cartoon. (For the Whole Story on Litton was immensely popular in Denver where football’s Broncos and baseball’s Rockies enthralled fans. “I really think local sports cartoons connect with readers in an amazing way,” he said to Torne. “I’ve done cartoons in Denver that people will talk to me about years later. One as far back as 1984. I can’t remember what I had for breakfast.” Although his deal with the Trib is as a freelancer doing one cartoon a week under contract, Litton hopes the assignment will develop into a full-time job. “I’ll be ready to do anything they want me to do,” he said with a chuckle: “Like— would you like a bagel with your coffee?” He’s been experimenting with animation for several years and would love to animate his cartoons for the Trib’s website, where, for now, his static cartoon will be posted simultaneously with its publication in the print venue. Litton said he’ll probably post it on his site the next day; drewlitton.com. Litton applaud’s the Trib’s hiring of Stantis: “I think hiring Scott Stantis was terrific and sends a message to other publishers that cartoonists sell papers. I’m hoping I can sell a few for them.” In the meantime, he’s “honored to be given a chance to appear in one of the nation’s greatest newspapers. I still can't believe it,” he concluded: “Please—I beg you, do not wake me up." ***** The Denver Post, the surviving paper in Litton’s hometown, may also testify to the power of comics. When the Rocky expired, the Post took over all of the defunct paper’s comic strips—and ran full-page ads to alert Rocky readers to the migration. Six months later, in the first circulation report since the death of the Rocky, the Post has reported that it has retained 86% of the Rocky’s readers. Publisher Dean Singleton said last winter at the Rocky’s wake that he hoped the Post could hold on to 80% of its former rival’s readers. What role three pages of comic strips played in this impressive achievement is, naturally, open to debate. But it makes me wonder what effect the circulation report will have on the results of a comics readership survey the Post conducted in August but hasn’t, yet, announced the outcome of. SEA-CHANGE AT FANTAGRAPHICS The Comics Journal is changing. Again. It is always changing. It has never stood still for more than a year or so. Every change over the years aimed at meeting new circumstances in the evolving comics market place. A couple years ago, the magazine abandoned saddle-stitch binding in favor of a square-back spine and reduced its trim size to 6x9 inches—book-size—and, as we mentioned here soon thereafter, it put the magazine’s name and issue contents on a 3x4-inch sticker on the cover; the sticker could be peeled off, and you might then think you were holding a paperback book in your hands instead of a square-spine magazine. The object, probably, was to make The Comics Journal viable in bookstore settings: on the shelf, if you peeled off the sticker, it would look pretty much like a paperback book, not a magazine. And now the Journal is taking yet another step in the same direction. As soon as issue No. 300 is out (not long now), the “magazine” will shift to semi-annual publication in print while simultaneously ramping up the TCJ.com website. The print version of the Journal will be variable in design, its shape and format changing to fit its content, which will continue to be interviews, essays, and “objets d’art” (vintage comics and cartoons), but the writing will be longer and meatier and aimed at archival permanence. Like a book, in other words. The digital Journal, on the other hand, will take advantage of the Web’s immediacy: online, the magazine will change daily, constantly up-dating itself with breaking news coverage, new and established bloggers, plus interviews, columns, and criticism in text and videos, slide shows, audio files, and galleries of original-art. When they told me and other regular contributors a few weeks ago of the impending change, I remarked that I thought it ironic in a mildly amusing way that a magazine that has established itself with criticism and commentary on a print medium, comic books, is now investing heavily in a non-print edition on the Web. Okay, everyone’s doing it. But that doesn’t make the maneuver any the less ironic. Ironic but, probably, ultimately, canny. And successful: I’ve been around the Journal through almost all of its changes over the years, and most of them, it seems to me, have worked to the magazine’s advantage. In any case, it’s been challenging and deeply gratifying to work for a periodical that has never been content to sit back on its laurels. Tom Spurgeon, one-time Journal managing editor and now proprietor of ComicsReporter.com, talked about the change with Gary Groth, Fantagraphics co-publisher and longtime Comics Journal editor. Groth told him that the move has been underway for a relatively short time, beginning about three months ago. Later, talking to Kiel Phegley at comicbookresources.com, Groth clarified, saying “there was nothing hurried about our deliberations,” adding: “I had been thinking about how to refine the magazine before then, and we'd often have impromptu conversations in the office about this same question.” “If things go according to their plans,” Spurgeon reported, “the revamped website should launch in late November. Groth says this will not have an effect on the magazine's current news blog Journalista! or its infamous message board: "Dirk [Deppey] will continue the fine Journalista! tradition, and the message board will, alas, remain much the same,” Groth said. Both financial and editorial concerns motivated the change, he explained: "It was always a strain to assemble eight commercially viable issues that were also aesthetically pleasing—balancing that fine line—every year. I feel much more comfortable concentrating our resources on fewer print editions each year and spending some of those resources on our web presence. It's no secret that newspapers and magazines are suffering because so much of what they've traditionally done can be done on the Web, faster and cheaper. We decided therefore to redesign the editorial and physical format of the magazine to take advantage of what print's best at—upscale production values, longer prose, more permanent content—and bring the Journal's mandate for criticism and commentary to the Web with a vengeance.” To Phegley, Groth added: “Reducing the frequency allows us the latitude to focus on quality over quantity, which is what I'd prefer to do. I'm looking forward to putting together each issue as a unified whole, or at least a sum of parts that come together in a pleasing way, and customizing the size, format, and package to accommodate the specific editorial focus of each individual issue.” The future print Journal will continue to showcase vintage comics art in color, as has been its practice since converting to square-spine format. And Groth suggested they may also publish original comics if they can figure a way to do it without duplicating the function of Mome, Fantagraphics’ anthology book of comics. About the digital Journal, Groth said: “I see this is an opportunity to create a true web version of The Comics Journal, to in effect combine the virtues of both the Web and print as I understand them, which is to say, a single ‘place’ where readers can come and expect a consistently intelligent, idiosyncratic, combative, and occasionally clashing conversation about comics and cartooning. Over the past few years I've noticed smarter critical commentary on the Net, but it's scattered all over the place, buried in the usual mountain of frivolous, tepid, dimwitted, unreadable fanboy drivel. There's no single website you can visit and anticipate a range of interesting sensibilities on an equal footing, so one of my goals is to distill the best criticism and journalism we can into a single site.” The previous format revision, the square-back paperback “book” look, was mildly successful in widening the Journal’s reach, Groth told Phegley, and hence, was partly responsible for the current evolution: “With No. 288's format change (almost two years ago), we have been distributed to bookstores, and this added a thousand or so copies to our readership”; and for a magazine with a circulation of 3,000-4,000, that’s a considerable increase. But Groth also saw “some slippage in the comics market at the same time, and I would've had to have been blind not to notice the overall trend in declining newspaper and magazine circulation throughout the country.” The webbed Journal will be much more of a multi-media enterprise said assistant editor Kristy Valenti, who mentioned the magazine’s “rich audio library”—all those taped interviews with scores of comics makers. And Groth, speaking to Phegley, added (perhaps tongue-in-cheek): “You'll probably be hearing my voice more than you'll want to with the debut of Gary's Happy Hour. For one thing, I plan on posting a fifteen-minute audio chat with Gahan Wilson every other week.” How the two incarnations will interact, if they do, lurks in the undiscovered future, Groth told Spurgeon. "I haven't the slightest idea at this point. I suspect that little of the material on the website will be reprinted in the print edition; rather, I'm anticipating that short pieces that appeared on the website may be expanded for the print edition—or the reverse, an excerpt of something we plan for the print edition may be previewed on the website. But there's going to be a learning curve while we figure out the different editorial requirements for both the website and the print edition. My main goal is to maintain the editorial impetus of the magazine on the website, making it an intelligent and sometimes provocative source criticism and commentary.” And, yes, he added: Ken Smith will be blogging. Summarizing for Phegley, Groth said: “If we can assemble the magazine at a more leisurely pace—rather than the breakneck pace that we've worked at for 33 years (that's the royal we; i.e., mostly me and a succession of poor, burnt-out editors)—we'll put out a better magazine. I hesitate to call it a magazine, too: it'll be distributed to the book trade by W.W. Norton and will retail for a minimum of $20.” It’ll be a book. And Fantagraphics, the Journal’s publishing entity, isn’t sitting still any more than the magazine is. It has just announced a string of new book projects; see Book Marquee down the scroll. ***** ISLAMIC HOODLUMS PLAN TO ASSASSINATE DANES. Just when you thought it might be safe to visit Denmark again, FBI agents broke up a plot to kill Danish cartoonists. Or to blow up the Scandinavian neighborhood. Or, perhaps, both. The Chicago Sun-Times reported that FBI agents arrested two Chicago men: David Headley and his friend, Tahawwur Hussain Rana, who shared an extreme hatred for the cartoons that depicted the prophet Muhammed. Headley went to Denmark in 2008 to reconnoiter possible targets, including the offices of the newspaper that published the Danish Dozen that inflamed the Muslim world in 2006, the cultural editor who had commissioned the twelve cartoons, and one of the cartoonists. Headley allegedly told agents he was trained by a terrorist organization called Lashkar-e-Taiba, according to his criminal complaint. Authorities say Headley reported to Ilyas Kashmiri, the operational chief of what the FBI describes as a Pakistani-based terrorist organization with links to al-Qaida, according to the complaint. Headley was headed to Pakistan to report to Kashmiri when the FBI foiled his plans, according to charges. Rana, a native of Pakistan and a Canadian citizen, who arranged Headley’s flight, was charged with providing material support to a foreign terrorism conspiracy. When told of an earlier plot to kill him, Kurt Westergaard, 78, the targeted cartoonist, said: "I am an old man so I am not so afraid anymore. I feel confident and safe in my private life. I'm angry because I have to live with threats, just because I have done my job. PET [Danish police intelligence] has advised me to keep a low profile and don't give statements. I will follow that, but I'm allowed to say that I'm angry." Westergaard had little to say about the current scheme, reported Jan Olsen at the Associated Press (google.com). He has said it took him 45 minutes to make the drawing, a picture of Muhammad wearing a bomb in his turban, considered by many Muslims to be the most offensive of the 12 cartoons. He has rejected calls to apologize to Muslims, saying that poking fun at religious symbols is protected by freedom of speech in Denmark. The drawing was meant to illustrate that Muslim extremists draw "spiritual ammunition from Islam," but not to criticize the religion as a whole, he said in February 2008 just after Danish police uncovered the other alleged plot to kill him. "I realize that when issues of religion are involved, emotions run high, and all religions have their symbols, which possess great importance," Westergaard said at the time. "But when you live in a secularized society, it's clear that religion can't demand some sort of special status. ... I have a problem with the fact that we have people from another culture who don't accept that we use religious elements in a drawing." The worldwide cartoon uproar forced Westergaard underground, living under the protection of PET. "For my wife and I, it's like a kind of dark depression has descended on us," he said. PET moved the couple from place to place—both within Denmark and abroad. Westergaard said the couple brought along cherished items—"mugs, vases, pictures" — to simulate a sense of home. Meanwhile, police continued to empty the trash, collect the mail and turn lights on and off in Westergaard's original home, to give the impression he was still living there. Westergaard reacted to the Chicagoans’ alleged murder plot with characteristic understatement, saying he was "maybe surprised—and a little shocked—to find that a situation like this could arise so suddenly." Asked if he regretted drawing the cartoon, Westergaard gave an unequivocal answer: "No, I don't. I mean, the friction between these two cultures (Muslim and Western) is always there. What will happen in the long run is that our culture—the materialistic, superior culture—will of course win out, and we will have, I think, a modified version of Islam that fits in with our secular society." The cartoon crisis polarized a discussion about the integration of Muslim immigrants in Denmark, Olsen reported. Many Danish Muslims said the cartoons were part of a pattern of degrading comments about Islam by nationalist politicians and in some media. Westergaard's supporters have commended him for defending the freedom of speech. "What I like about him is that he stands firm about his drawing," said Helle Merete Brix, chief editor of a magazine published by Denmark's Free Press Society. "He is a product of the European way of poking fun of authorities, whether they are religious or political." But Mohammad Rafiq, a Danish writer of Pakistani origin, called Westergaard "naive" and said he and the other cartoonists had failed to understand what the Prophet Muhammad means to Muslims. "Denmark has failed to build a bridge between the cultures," he said. ***** Most of the news reports about the Danish Dozen and the ensuing helter-skelter explain the Islamic ire by saying that images of the Prophet (all prophets, actually, including, for Muslims, Abraham and Jesus) are forbidden in Islam because they might foster idolatry. The implication is that Islam has therefore forever proscribed such visual representations. Not so. In the November 4 issue of The New Republic, Oleg Grabar, a professor emeritus at Harvard and the author of Masterpieces of Islamic Art: The Decorated Page, takes considerable pains to demonstrate that throughout the history of the religion, “pictures of the Prophet Muhammad have been produced, and are still produced, by Muslim artists for Muslim patrons.” And many pictures of Muhammad have been made by non-Muslim artists. “There can be no doubt,” Grabar finishes, “that, especially from the thirteenth century onward, the Muslim world accepted the existence of representations of the Prophet.” So to explain the furor over the Danish Dozen by invoking a supposed doctrinal prohibition is disingenuous. Or, more likely, ignorant. Muslim outrage over the Danish cartoons is probably caused by their being cartoons, not by their being images of Muhammad. To represent the Prophet as a cartoon character is clearly perceived as an insult. Cartoons are commonly understood as devices of ridicule; to cartoon Muhammad then is to ridicule him. And that’s what probably upset Muslims, those whose distress over the imagery was genuine rather than, as in the case of the Islamic Hoodlums, trumped up for the purpose of justifying riots in the streets, murder, arson, and wholesale looting. Garbar wrote his New Republic article in reaction to Yale University Press’s decision not to publish any of the Danish Dozen in a scholarly book about them entitled The Cartoons That Shook the World by Jytte Klausen. (We covered the incident in Opus 247.) The Press explained its decision by referring to the 2006 cartoon-sparked conflagration worldwide, saying it didn’t want the publication of the book to cause any more bloodshed and destruction. Grabar writes: “Yale’s decision is certainly a denial of free speech, though of course the argument can be made that a possible danger to people may compel restrictions in the expression of opinions and of facts. I am not persuaded by this argument about this book. And the deletion of the images is also—a far more important criticism in this instance—a gratuitous betrayal of scholarship since many other books (including at least four published by Yale, two of them by me) do show images of the Prophet.” My emphasis. Yale didn’t want to print the pictures for a very simple reason: the university poobahs were afraid. In this, they join the editors of most American news media—to our everlasting shame. **** The Boondocks creator Aaron McGruder, well out of public view lo these many months since abandoning his comic strip for animation, and Oscar-nominated actor Don Cheadle are teaming up for a comedy series for NBC, according to Variety. Both will serve as executive producers, and McGruder will write the script. The sitcom involves mismatched brothers who reunite to open a private security company. ... In Japan, a manga book that describes both Hitler's autobiography and his infamous Nazi manifesto Mein Kampf in the unlikely form of easy-to-read comic pictures and captions has become a best-seller reports Danielle Demetriou at telegraph.co.uk. “The book, which forms part of a series on world classics turned into manga, covers a range of aspects of Hitler's life, from his childhood to the formation of his political party. Its success in Japan has reportedly ignited a debate in Germany about whether the ban on Mein Kampf imposed since 1945 should be overturned.” The publisher’s current series also includes a popular manga version of Karl Marx's seminal anti-capitalist tome Das Kapital. Amid all the excitement of the Town Hall Tumult in August you may have failed to notice that Jeremy Duncan, the ostensible star of Zits, a comic strip written by Jerry Scott and given visual life by Jim Borgman, turned 16 on August 14. "After freezing Jeremy at 15 for over a decade, it just felt like time to cut the kid a break and move on to a different set of challenges and frustrations," Borgman told Michael Cavna of ComicRiffs. The most visible evidence of Jeremy’s maturation is that he’ll get a driver’s license."I think it's going to give us new writing opportunities," Scott told Cavna. "We felt [ age 15] was the maximum frustration age. You think you can run the world and you can't even drive a car. ... There will be more strips that don't involve [Jeremy's] parents ... we're going to get inside his head a little more."

***** Stephen King, among the most adapted novelists to film, is also becoming one of the most adapted writers to comic books, reported Vaneta Rogers at newsarama.com. "He has always loved comics, so I think he's really open-minded about his novels becoming comic books, and that's why you see him being so enthusiastic about it," said Robin Furth, King's collaborator on his recent comics adaptations. "Some of the first things he wrote as a kid were comics. And it's comparable to making a film out of a book. It reaches a whole new audience. It takes a story and puts it into a new medium." ... Furth, who was King's research assistant from 2000 to 2004, is also working with King on a series of monthly comics at Marvel based in the world of his Dark Tower novels. Marvel is also currently adapting King's The Stand to comics. ... Says Furth: “When we first started, we were all coming up with character sketches and talking about how things will move forward. They've gone over, really carefully, how all the characters will be depicted. And they're really good at looking over all the scripts, which is amazing when you think about how busy they both are," she said. "There's such a change when you move from a novel to a graphic novel. You have to translate the action into really visual sequences. And it means condensing the stories into scripts for each issue. But they've been involved from the very beginning." For Furth, the experience of condensing King's novels and working with an artist to interpret the writer's vision has taught her a lot about writing and about the way King structures his work. "I've learned so much," she said. "You have to work so hard condensing and condensing. It makes you really think about the story and what the key elements are. At this point, I go with my instincts. What is it that really grabs me about a section? When I close my eyes, what do I see? And I'll write up scene by scene and panel by panel." Michael Doran at newsarama asked King what were his favorite comics as a kid, and King replied: “Oh, come on—everything! But my favorite, by a country mile, was Plastic Man and his pal Woozy Winks. I dug Plas's dark glasses!” ***** Internationally renowned writer Salman Rushdie is another comics fan. He had what ICv2 calls “a graphic novel moment in his appearance on CBS’s ‘Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson’ recently. When Ferguson asked him if he’d ever thought about writing a book “with just pictures and stuff,” Rushdie said: “Yeah, and actually I got asked recently if I’d like to write a graphic novel. I was kind of keen on it. When I was a kid I was a real comic book nut. I could tell you a lot about superheroes.” ICv2 continued: “Rushdie then launched into a discussion of Aquaman and segued into Kryptonite, muffing the difference between Green and Red Kryptonite after bragging that he knew what they were. But he circled back to the graphic novel concept and wrapped up with, ‘So I’m quite attracted to the idea of a graphic novel. I might have a go.’” ICv2 thinks the episode was probably planned if not outright rehearsed: “It seems unlikely that the question from Ferguson came out of the blue; most topics on a late night show are pre-determined. So it seems more likely that Rushdie is creating a little pre-awareness for an upcoming project. His writing has included science fiction and magical elements, a natural background for writing comics.” ***** After B.C. cartoonist Johnny Hart died a couple years ago, the strip didn’t wander much into the spiritual arenas that Hart often visited. But the Hart family has produced a new book, I Did It His Way, that collects some of Hart's best-known religious cartoons, tries to explain one of his most controversial, and pays tribute to the cartoonist. “The book,” writes Lindsay Perna at Religion News Service, “is packed with Christian crosses, theological debates and Hart's unique wit. ‘He wanted people to know that God had a sense of humor,’ said his daughter, Perri Hart, who produced the book with her father's widow, Bobby. ‘He really always felt that this was what he was called to do,’ she said.” Elsewhere, in Binghamton, New York, B.C. is coming off the page and onto pavement. In early October, the first three-dimensional dinosaur in the image of one of Hart’s creations was unveiled. More are on the way. In the manner of the fiberglass statues of cows and elephants and donkeys that wander the streets of Chicago and Washington, D.C., the Hart monsters will be painted by local artists in their own style. The Hart family helped develop the project. Said Mason Mastrioanni, Hart’s grandson who now draws the strip: "It's fortunate that our area is known for something so unique and hopefully this will be a fun project because it's unique and it's cartoon characters whereas some of the other towns [have] more realistic looking sculpture. I look forward to seeing what the artists do with it.” ***** EXPLOITING THE MEN OF STEAL. Last summer, while we were looking the other way, Warner Bros. and DC Comics won a favorable ruling in the suit filed by the heirs of Superman co-creator Jerome Siegel. While an earlier case determined that the Siegel heirs held some rights to the character, a U.S. District Court in July “found that the license fees the studio paid to corporate sibling DC Comics didn't represent ‘sweetheart’ deals as they weren't below fair market value. That means the heirs will be able seek profits only from DC Comics—which earned $13.6 million from Warner Bros. for the 2006 release of ‘Superman Returns’—rather than from Warner Bros. as well,” reported Dave McNary at Variety. The same judge set a December 1 trial date “for determining the allocation of profits to the heirs, who won a ruling last year that awarded them half the copyright for the Superman material.” Attorney Marc Toberoff, a copyright specialist who represents heirs Joanne Siegel and Laura Siegel Larson, asserted in a written statement that the Siegel heirs and the heirs of co-creator Joe Shuster will own the entire Superman copyright in 2013. Said he: "This trial was only an interim step in the multifaceted accounting case which remains, in that it only concerned the secondary issue of whether DC Comics, or DC Comics and Warner Bros., would have to account to the Siegels," he said. "To put this in further perspective, the entire accounting action pales in comparison to the fact that in 2013, the Siegels, along with the estate of Joe Shuster, will own the entire original copyright to Superman, and neither DC Comics nor Warner Bros. will be able to exploit any new Superman works without a license from the Siegels and Shusters." He added: "The Court pointedly ruled that if Warner Bros. does not start production on another Superman film by 2011, the Siegels will be able to sue to recover their damages. The Siegels look forward to the remainder of the case, which will determine how much defendants owe them for their exploitations of Superman." ANNIVERSARIES AND BIRTHDAYS GALORE Another thing that happened last August that slipped under the door unnoted here

because we were fuming about something else—the comic strip Little Orphan Annie,

which now goes by the name Annie, celebrated its 85th birthday on Wednesday, August

5. We’ll light candles now. On the 5th, though, writer Jay Maeder and artist Ted

Slampyak broke into their normal, globe-trotting storyline to produce a single-panel strip

showing the title character walking down the street, with her ubiquitous dog, Sandy,

trotting alongside. "Please permit us to interrupt our story for an anniversary

observance," reads the accompanying text. "Annie's strip is 85 years old today." And

Annie and Sandy are depicted exactly the way they appeared when Sandy joined the

famed orphan January 5, 1925, as you can plainly see in the panels from that period

that we’ve assembled in this vicinity. Editor & Publisher continued its article (in italics): Original creator Harold Gray intended to call his character Little Orphan Otto but switched the character's gender at the suggestion of syndicate head, the New York Daily News’s Joseph Patterson. The rags-to-riches story of the little girl who was adopted by the rich Oliver Warbucks resonated with Depression America, and the strip spawned two feature films and a national radio show, sponsored by Ovaltine, which was itself immortalized in the 1983 film, "A Christmas Story." Gray continued to draw the strip until his death in 1968, after which the strip declined in popularity, eventually going into reruns in 1974. But the character Annie returned to the limelight after the 1977 premiere of the Broadway musical "Annie," which ran for close to six years, and spawned another feature film. The strip, subsequently renamed Annie, was revived in 1979 by cartoonist Leonard Starr, who drew it until his death in 2000. Since then, artists Andrew Pepoy, Alan Kupperberg, and Slampyak have teamed up with Maeder to produce the comic, which currently runs in only about 50 daily newspapers, nationwide. You can pursue this subject and the Whole Sordid History of the abused and oft-abandoned red-haired orphan in a book of mine, The Art of the Funnies, about which there is more here ***** The 50th anniversary of the small but cunning warrior Asterix and his pudgy stonemason pal Obelix is being celebrated with a new book, The Birthday of Asterix and Obelix, the 34th in a series, time.com says, that was initially “created as a way to keep American comic strips from taking over France.” (Not a bad idea, now that it has surfaced again. How else could France be taken over but by comics?) The new book celebrates the golden jubilee with 56 pages of unpublished drawings by the characters’ co-creator, comic artist Albert Uderzo, who said: "It's a little different from the classic albums," adding, “they’re short stories, in which all the characters refer to the anniversary." The new book, said the Barcelona Reporter, contains many of the friends that Asterix has accumulated over fifty years because everyone is invited to the big party that the villagers have prepared. “The artist recalled the birth of these adventures, when on October 29, 1959, these Gauls appeared in the first issue of the weekly magazine Pilote, a magazine that aimed to address the invasion of U.S. comics.” Asterix the Gaul came out in book form in 1961, bearing the name of Uderzo and his co-creator, Rene Goscinny, and since then millions of readers have benefitted from the 32 books that followed, plus eight animated films. Meanwhile, anticipating Peanuts’ 60th Anniversary in 2010, the Peanuts Foundry is banging out the launch event of the festivities, the first-ever Peanuts 60th Anniversary Photo Look-A-Like Contest (www.peanutsphotocontest.com), which will benefit Boys & Girls Clubs of America (www.bgca.org). Reuters reports that Peanuts fans of all ages were invited to submit photos of themselves or their children looking like one of these Peanuts characters: Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Lucy, Linus, Sally, Schroeder, Franklin, Peppermint Patty, Marcie or Pigpen, or one of Snoopy`s classic alter-egos, Joe Cool or the World War I Flying Ace. Submissions were accepted through November 3. Results TBA. Another anniversary is that of Casper the Friendly Ghost, who turned 60 this year. Dark Horse Comics has reprinted Casper's first comic in a hardcover that drops next month reports Rene A. Guzman at the San Antonio Express-News. "Casper is a true entertainment franchise," says Nicole Blake, senior vice president of marketing and consumer products at Classic Media, which owns and manages the rights to the character. "Decade after decade, Casper is reinvented and reimagined successfully. I would almost say he's one of the original multimedia stars." Classic Media notes Casper has sold more than100 million comic books since his 1949 publishing debut, not to mention starring in hundreds of cartoons as well as a 1995 Steven Spielberg-produced film. The character was originally the basis for a 1939 children's book by writer Seymour Reit and illustrator Joe Oriolo. The book didn't happen, but a 1945 Paramount cartoon aptly called “The Friendly Ghost” did. But the juvenile phantom had no name. Then in 1949, St. John Publishing brought out the comic book entitled Casper the Friendly Ghost, No. 1, and Casper was christened and soon rose to cartoon prominence in the fifties with a series of theatrical animated shorts. ***** VOLUNTEERISM EXPLAINED. The recent week of comic strips about volunteerism that I mentioned last time was, as I should have guessed, instigated by the National Cartoonists Society (NCS). Luann’s Greg Evans was involved and wrote to thank everyone who participated, passing along the heartfelt thanks of Bill Hoogterp (a volunteerism honcho, I guess), who coordinated the effort and, afterwards, said: "Please, please, please pass on our tremendous thanks to the members of NCS. We have gotten so much positive response! Millions of people are talking about volunteering. NCS did the impossible, you made volunteering more cool! People are calling and signing up to make a difference at countless local agencies. All because of you guys. The world is a little better place today because the world’s greatest cartoonists gave of their talent and touched people in a way that only you can. And your gags were great! Just heard from J.J. Abrams also, who sends his regards and thanks as well!" Then Evans appended a bizarre footnote: “I'd just like to add something here. I want to apologize to any of you who got the kind of irate email I got last week. It never occurred to me that this effort would be viewed with a political skew and that it would be perceived as ‘kowtowing to Big Government.’ I just thought we were doing a good thing, not being ‘commies.’ So sorry.” Is there to be no end to the bellyaching being performed from sea to shining sea by the Gripy Old Pachyderm and its many malcontented minions? What next? **** NEXT: Cartoonists’ good deeds are not confined to the funnies page. Recently, Stars & Stripes reported, some of America's best-known cartoonists took off on a USO tour of bases in Germany and the Middle East. According to a USO press release, the group included Jeff Bacon (Broadside and Greenside), editoonist Chip Bok (Ohio’s Akron Beacon Journal), Bruce Higdon (Army Times, Army Magazine, Soldiers Magazine), Jeff Keane (The Family Circus), Rick Kirkman (Baby Blues), Stephan Pastis (Pearls Before Swine), Mike Peters (Mother Goose and Grimm), editoonist Michael Ramirez (Investors Business Daily), caricaturist Tom Richmond (Mad), and Garry Trudeau (Doonesbury). The tour evokes a National Cartoonists Society tradition that dates to World War II before the Society even existed; in fact, it was formed by cartoonists who, while performing before soldiers convalescing in military hospitals, discovered they enjoyed each other’s company and decided to prolong the camaraderie by establishing a club. "I'm so proud of our men and women in uniform," said Keane, NCS President. "They, much like my dad who served in the Army back in the mid-1940s, have worked so hard and sacrificed so much. I am honored to be part of this USO tour and I can't thank our troops enough." Several of the cartoonists with blogs—Richmond and Pastis in particular—reported their adventures during the tour. Because of security concerns (remember: rampaging Islamic hoodlums have an unsatiated appetite for killing cartoonists), the bloggers can’t say where they are. But they can say what they’re doing. Pastis, for instance, wrote: “Spent all day lying in the sun at the edge of the Persian Gulf. Was going to solve all of the Middle East’s problems, but decided to get a tan instead. Tomorrow I go to a new country. I’d like to name it, but I’m not allowed to identify it until I get back home. I’m like James Bond, but without the nice car. Or fancy clothes. Or hot women. Instead, I’m with a bunch of pudgy, middle-age cartoonists.” What a joker that Pastis. For the Whole Story of how the cartooner club came into being, visit Harv’s Hindsight and look for “Rube Goldberg and the NCS.” ***** NEW YORKER STILL ISN’T FUNNY OR SERIOUS ENOUGH. Linda Holmes at NPR is as puzzled by inexplicable New Yorker cartoons as anyone, and she lately noticed that the magazine has posted on its website a feature “that's either refreshingly self-deprecating or completely passive-aggressive, and I can't figure out which.” If you go to "I Don't Get It,” you’ll see five of the magazine’s cartoons that readers have claimed they can’t understand; and each is accompanied by multiple-choice “explanations.” You can choose the one that tickles your funnybone. Said Holmes: “I find myself conflicted. Part of me wants to applaud them for embracing the fact that many people find the cartoons inscrutable, but part of me feels like they're making fun of me. I can't tell if they are helpfully trying to hold my hand as I cross the street of highbrow humor or satirizing the idea of rubes like me requiring hand-holding. Am I the butt of the joke, or are we in it together, just trying to figure out what makes one-panel humor work in this crazy world?” Contrary to the impression conveyed by Holmes’ discovery, the website “test” is not a stand-alone venture: it reprises the content of this year’s Cartoon Issue of the magazine, just out. And the same multiple-choice game ran in last year’s Cartoon Issue. The New Yorker’s annual cartoon admiration rite continues to be a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it is the only hoopla about magazine cartooning in the land of the turtle, and because it hoorahs cartooning, we tend to applaud it, overlooking, on the other hand, its conspicuous shortcomings as a “cartoon issue.” In a magazine that champions cartooning and prides itself on both its cartoon and prose content, you’d think the Cartoon Issue would do more for cartooning than simply print a dozen uninterrupted pages of cartoons more than it usually publishes. You’d think, in short, that the Cartoon Issue should perpetuate the practice that it initiated in 1997 when it carried articles about cartoonists and cartooning as well as more cartoons that usual. But, no—that hasn’t happened. Ever again. The inaugural Cartoon Issue was the best and, subsequently, the only issue that treated its subject in both prose and picture. And it’s happened again this year: there’s an 18-page section of “The Funnies” that offers 6 pages of the usual baffling New Yorker cartoons followed by an equally baffling 4-page comic strip by wallpaper cartoonist Chris Ware, whose tiny tiny pictures of doll-like figurines are not only a strain on the eyes but a pain in the ass and an insult to the medium. Ware also drew this issue’s cover, entitled “Unmasked,” and his comic strip, with the same title, would seem to be some sort of explication of the cover image but isn’t. Not much. It is instead another of his depressing revelations of the human condition among those not well adapted to it. His cover, though, contemplated as a stand-alone objet d’art, is a beaut. Roz Chast again claims two pages with some mug shots of ugly people, another two pages are devoted to a cut-and-paste cartoon game, and on the final two pages, cartoonist Zachary Kanin presents a tedious comic strip about vampires, thereby consecrating the latest pop culture fad. Then there’s the “test” Holmes is so perplexed by. And that’s it. No articles about cartoonists at all. None. You’d think they could drum up something about the most visible cartooning phenomenon of recent years, graphic novels; but no, nothing. And adding insult to injury, each of the two-page spreads of the 6-page “The Funnies” section prints one cartoon across the gutter so the picture is spoiled by having a paper canyon through its middle. You might be persuaded from the content that The New Yorker is trying its best to ignore the cartoons it’s pretending to glorify. And I suspect that’s exactly the case. The first Cartoon Issue was dated December 15, as if it were conceived as a Christmas present for readers. In subsequent years, the Cartoon Issue has retreated, slowly, away from late December into late November. And last year and this, the Cartoon Issue bears an early November date (November 2 this year). This is an insidious ploy: by moving the Cartoon Issue back in the calendar a little each year, you eventually can claim that last year’s Cartoon Issue is actually this year’s and thereby avoid publishing one of the things altogether. That’s how the magazine will eventually escape for at least one year doing a duty that it has evidently found odious. It is to weep. ***** The next issue of McSweeney’s Quarterly, No. 33, due out momentarily, is “an attempt to demonstrate all the great things print journalism can (still) do, with as much first-rate writing and reportage and design (and posters and games and on-location Antarctic travelogues) as we can get in there,” saith the press release. No. 33 will be a “one-time-only, Sunday-edition sized newspaper—the San Francisco Panorama—and it’ll have the news of the day, plus sixteen pages of comics from the likes of Chris Ware and Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman and many others besides. But, apparently, no editorial cartoons. At least none the publisher feels like mentioning at this date. For subscription information (i.e., purchase instruction), consult store.mcsweeney.net. This is the third attempt that I’m aware of to rejuvenate the Sunday funnies by publishing an exemplary model. DC Comics did it with its short-lived Wednesday Comics; and then in Minnesota a couple months ago a consortium of enthusiasts published Big Funny, a coffee-table size paper of original comics that pays heed to the glory days of newspaper comics. Someday, one of these things might catch on if we’re not careful. Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. CLIPS & QUIPS “News is something somebody doesn’t want printed; all else is advertising.” —William Randolph Hearst “Autumn is a second spring when every leaf’s a flower.” —Albert Camus “Misery no longer loves company. Nowadays, it insists on it.”—Russell Baker KRAZY THEME PARK George Herriman is not likely to turn over in his grave. But if he could, given the provocation, he probably would. The parched and sublime precincts of his beloved Monument Valley with its picturesque pinnacles and towering cathedrals of raw red rock have been invaded by a $14 million 95-room ultra modern hotel. Monument Valley is a landscape like no other, a hauntingly desolate desert the pervading flatness of which is punctuated by giant outcroppings of red sandstone carved by wind and rain into silent hulks and spires, other worldly sentinels on a lunar plain, stranded there in the middle of nowhere for eons until John Ford discovered the Valley in 1938 and turned it into an iconic setting for movies like “Stagecoach” and “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon” thereby giving the airy mythology of the Old West a locale habitation and a name. Others had been there before Ford. The Navajos lived on these arid sands for centuries, quietly herding sheep and weaving rugs from the wool. In the late 19th century, the Wetherill brothers established a trading post in the coal-mining town of Kayenta, about 30 miles south of the Valley, and in about 1923, Harry Goulding and his wife Mike (Louise) bought 640 acres of desert for $230, intending to ranch and trade with the Navajos. Later, hearing that a Hollywood director was scouting locations for a Western motion picture starring John Wayne, the Gouldings drove to Los Angeles and convinced Ford that Monument Valley would be the ideal backdrop his movie. Ford’s movies showcased the stunning vistas of the Valley and attracted attention, and before long, some tourists were brave enough to trek across the desert’s rocky roads to see the sandstone splendors in person. Tourism became more lucrative than ranching, and in the 1940s, the Gouldings responded by building a 8-room motel, just a few miles outside the Valley along U.S. highway 163. Later, they expanded it to 80 rooms, plus a restaurant, campground, grocery store, gas station and a number of private homes. In 1958, Monument Valley was designated a Navajo Tribal Park, formalizing its 30,000 acres within the reservation of the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona and southern Utah and assuring its continued existence as a scenic wonder rather than an amusement park, which is doubtless what it would have become. (And may yet.) I drove through the Valley for the third time almost forty years ago, taking my new wife on her first foray through the baked and nearly barren Southwest. The gravel road from Gouldings to the Valley’s visitor center shot through the desert straight as a spear, but it was a bone-rattling washboard all the way and shook the car violently at any speed over about 15 mph, so we drove slowly. The visitor center, a humble adobe building perched on a bluff overlooking the Valley, wasn’t very extensive, but we learned there that if we wanted to photograph any of the Navajos who sit along the road selling jewelry and rugs, we should offer to pay them for the impertinence. Seemed sensible to me. One of the natives, Frank Jackson, age 70 last summer, has made a living posing for tourists for 40 years: astride his horse and wearing a blazing red pearl-buttoned Western shirt and turquoise jewelry, he provides local color for vanloads of camera-pointing tourists. Foolishly perhaps, I thought that making photographers’ models of the Navajos was insulting and so I took no pictures of them, paid no pittance for the privilege. The road through the Valley is dirt, not gravel—or, rather, sand, red sand, parallel tire tracks more than a road. Virtually a one-way beaten path, it begins down a steep incline behind the visitor center and then winds among the yucca, juniper and sage, passing by drifts of sand and lofty redstone obelisks and the other towering rocky sculptural monuments for seventeen miles in a circular route, returning, eventually, to the visitor center on the bluff. No sound shatters the desert hush; an ageless lucid stillness fosters a spiritual sense of appreciation and, even, awe. I’ve been to Monument Valley three times; Herriman, many more. When he first went there, we don’t know, but it may have been at the instigation of fellow cartoonist Jimmy Swinnerton. Like Herriman, Swinnerton was a Hearst cartoonist; like Herriman, he was treasured by William R. Hearst. “Swin” started cartooning for Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner in 1892 and followed Hearst to the New York Morning Journal in 1899. Like most newspaper cartooners of the age, he produced a daily assortment of comic strips and cartoon panels, among them, starting in 1904, a strip about a little kid named Jimmy who couldn’t do anything right, a failing he unfailingly revealed anytime he was sent out of the house on an errand. In 1906, Swin was diagnosed with tuberculosis; Hearst, anxious to save one of his star cartoonists, sent Swinnerton to Colton, California, a haven for tb sufferers, in the hope that Swin would recover in the dry climate. And he did: in one of the profession’s legendary performances, Swin lived another 68 years, most of them in the dehydrated stretches of Southern California and Arizona, making only occasional business trips to San Francisco and New York. In the course of his recuperation, Swinnerton took up painting and traveled around the Southwest capturing its majestic panoramas on canvass. He lived for a time in the Grandview Hotel, then a Hearst property on the rim of the Grand Canyon, and from there, he made numerous sketching trips, camping out wherever in the deserts he foraged for a view. He met John Wetherill and went into Monument Valley with him. Swin often organized painting safaris into Arizona for his cartooning and painting friends. On one such, in August 1922, George Herriman and Rudolph Dirks were in the party. They followed a route familiar to Swinnerton: first to Flagstaff, then to Kayenta and Monument Valley. But Dirks and Herriman had been to Monument Valley long before that 1922

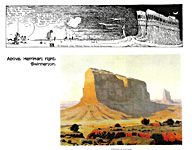

summer. In his book about Herriman and Krazy Kat, cartoonist Patrick McDonnell speculates that Herriman may have been prompted to visit the Valley by a 1913 article

Theodore Roosevelt had written about his trip there. But McDonnell found reference to

Coconino County in Herriman’s strip as early as 1911, when Krazy Kat was still in its

formative first years. (The Kat appeared as part of The Family Upstairs in 1910, getting

stand-alone status in 1913.) But the first appearance in the strip of a recognizable butte

from Monument Valley was on a weekend page in the fall of 1916, the first year of Krazy

Kat “Sunday” strips. (Krazy Kat in Sunday format was initially dated for Saturday

publication, and the strip wasn’t published in color until June 1, 1935.) On September

17, 1916, we see in the distance of the opening panel the “Enchanted Mesa where Joe

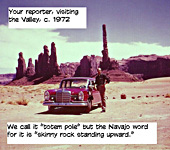

Stork lives,” as rocky a rampart as any in the Navajos’ enchanted Valley. The landscape that served as background for Krazy’s antics had always been whimsical. Much of the time, it was barren, a flat horizon line with, occasionally, a single tree, sprouting in solitary splendor like a giant asparagus or a celery stalk crowned with just a sprig of foliage. But the Enchanted Mesa introduced a new element of background hilarity. The horizon was still distant, and flat, but it was now subjected to regular eruptions of buttes and mesas and other soaring rock piles imported directly from Monument Valley. Herriman and his wife and daughters went to Monument Valley every summer for at least twenty years. They stayed with the Wetherills at “the ranch of serenity” in Kayenta, and Betty Zane Rodgers, the Wetherills’ adopted daughter, remembered their visits for McDonnell: “His stay was to escape from his routine in the city, and he visited, relaxed, and did a little work when he felt like it. ... He rarely talked of his work. ... George was concerned about the Navajo people and listened while my mother, Mama Lu, talked of the Navajo. He often went to the ceremonials with my folks.” Mike Goulding also remembered Herriman’s visits: “We met George Herriman in Kayenta. He always stayed with Mr. John [Wetherill] and was very interested in the Navajo people and wanted them to know some of the things we did out in the world, so he sent in the first movies they had ever seen. Once a week at the old sanitarium we could all gather and see Tom Mix or some kind of movie. Great fun—the Navajos always laughed at the sad scenes!” Images of Navajo culture appear in Krazy Kat as often as the taciturn sandstone pinnacles. Said McDonnell: “He made use of their designs and motifs, which may appear on a piece of pottery, as elaborations on the border of a strip, as the ornamental trim on a house, as the decorations on the mesas and the foliage of the trees, and also as the overall design of a Sunday page.” But it was the ephemeral topography that imparted to Krazy’s world its distinctive aura. Some have called Krazy’s world surrealistic; the poet e.e. cummings said it was “a strictly irrational landscape”; Italian author Umberto Eco spoke of its “improbable lunar landscape.” But they are wrong: Krazy lives in Monument Valley. Herriman imported into the strip fairly accurate representations of the rocky outcroppings of the Navajos’ fabled Valley. In the strip, the landscape changes behind Krazy from panel to panel, imparting to the proceedings a dream-like ambiance. The changes—and the dreamscape—are Monument Valley, as McDonnell observes: “The perpetual metamorphosis of Herriman’s settings can, in part, be attributed to the changing light playing over the huge rock formations. These ‘sculptures,’ though unchanged for millennia, appear to alter in color and shape with each blink of the eye as they pick up every gradation of the rays of the sun, passing across the heavens from dawn to dusk.” Krazy doesn’t seem to notice the changes taking place behind his back. He behaves as if it’s normal. But the landscape, his world, is as quirky as Krazy: it is as much a part of him as he is of it. Together, they are one—one vision of life. The topography of Monument Valley as depicted in the strip emphasizes the universality of Krazy Kat’s vision: we see in it our common bond, the community of a baffled humankind, united in the oddities of custom and language as perplexing as the ever altering landscape where we wait for and rejoice in any sign of love. In this setting, even a thrown brick will do to justify our faith in each other. When Herriman visited the Valley, he didn’t make paintings of the enchanted mesas before him, McDonnell says; he just looked. And I think I know what he saw. He saw in the stark and burnished red sandstone monuments on their unrelievedly flat plain a mystery, a majesty and a miracle, what John Muir often saw in vistas before him: “The grand show is eternal. It is always sunrise somewhere ... Eternal sunrise, eternal sunset, eternal dawn and gloaming, on sea and continents and islands, each in its turn, as the round earth rolls. ... Presently you lose consciousness of your own separate existence; you blend with the landscape, and become part and parcel of nature. ... Here you may learn that the miracle occurs for everybody doing anything worth doing, seeing anything worth seeing. One day is as a thousand years, a thousand years as one day, and while yet in the flesh, you enjoy immortality.” Herriman was somewhat less metaphysical, writing: “That’s the country I love and that’s the way I see it. I can’t understand why no other artists ever use it. ... I don’t think Krazy’s readers care anything about that part of the strip. But it’s very important to me and I like it nearly as well as the characters themselves.” It seems to me that a person must be alone in nature in order to feel a sense of oneness with all life and eternity, in order to lose consciousness of your own separate existence and blend with the landscape. The new hotel in the Valley threatens the otherwise pervading sense of solitude. The hotel, while not an eyesore by any means—it was designed to meld with the natural geology—is an intruder and a harbinger of future change. Goulding’s Lodge was sold last summer, the new owner planning convention facilities, a spa and an upgrade to four-star accommodations. And work was underway to build a new visitor center with an interpretive adjunct and a museum honoring World War II Navajo code talkers—scheduled to open this fall, in October 2009. The new hotel, named, with unintended ominousness, The View, infringes upon the essential solitary serenity of the Valley’s desert mythos. Is it possible to blend with the landscape while viewing it through a ceiling-to-floor glass window from an air-conditioned room? You are an observer in that ritual, not a part of the thing observed. Linda Jackson Rodriquez, one of the 70 or so Navajos who live within the Valley’s boundaries, passes the hotel frequently but has never set foot inside it. “A lot of people come here for the spirituality and tranquility of the place,” she says. “Not because it’s another Sedona.” But another Sedona, a New Age-y resort town north of Phoenix, is exactly what seems, now, inevitable. I’m sure Herriman won’t turn over in his grave. He probably would if he could, but he can’t. In accordance with his wishes, when he died in 1944, he was cremated and his ashes scattered over the sands of Monument Valley.

***** Now here are some of Swinnerton’s paintings of Monument Valley and a couple of Herriman’s renditions in Krazy Kat.

RAGGED AND FUNNY Writing about those who want to keep the church and state separate by prohibiting displays in the public square of religious symbols, the Denver Post’s Mike Littwin said: “I think the argument may well be correct, but that’s not the same as being right.” Said Lucy after jerking the football away from Charlie Brown again on October 4: “I figured you knew that I knew you knew I knew that you knew I knew you knew so I had to jerk it away.” “The genius of Twitter is that it manages to be even stupider than tv. Twitter has become a playground for imbeciles, skeevy marketers, D-list celebrity half-wits and pathetic attention seekers. No wonder we can’t get enough.”—Daniel Lyons, Newsweek columnist EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted

Below that, Nate Beeler gives us an image of Iran’s Mahmoud Ahmadinejad that perfectly conveys the cartoonist’s assessment of the Iranian president’s characterization of his nation’s nuclear program as wholly peaceful, intended to supply energy for the country not explosions for the rest of us. Pinocchio’s tell-tale nose grows when he lies, and in this case, the lie reveals the truth in more ways than one. The size of the nose tells us Ahmadinejad is lying; the missile image tells us what he’s lying about. (Ahmadinejad’s most signficant accomplishment, it seems to me, is having taught us all how to pronounce his name.) Jim Morin’s cartoon I at first thought was a fairly routine not particularly telling use of the resources of editoonery. But on closer examination, it seems to hit harder than I thought at first. Looking for a visual metaphor (like those above) is a good way, I submit, to begin evaluating the effectiveness of an editorial cartoon, but that kind of examination doesn’t go far enough. The only obvious visual metaphor in Morin’s cartoon is the Giddy Old Pachyderm, standing for the Republican Party. But in the rest of the cartoon, imagery functions almost as powerfully as metaphors do. The cartoon dramatizes a routine criticism of Republicans by Democrats: for instance, in lambasting Democrats for increasing the national debt with successive waves of stimulus bills, Republicans seem conveniently to forget that their war in Iraq used up the Clinton-generated surplus in the Treasury and then piled up billions in debt. So who are the more spendthrifty, Democrats or Republicans? (The answer is: politicians generally, without regard to party affiliation.) Morin takes a similar tack. His cartoon presents a playlet in two acts: Act One shows a non-dithering approach to Iraq; Act Two, the dithering approach to Afghanistan. The image of Act One dramatizes the near panic that inspired the invasion of Iraq—the continual chorus of exhortation, the military marching to its chanting cadence. Action, excitement. But we know the consequences of all that—the quagmire of Iraq. In contrast, Act Two is an uncluttered, placid panel with the Grumpy Old Pachyderm complaining about Obama’s inaction. The contrast of Act One and Act Two creates a memorable comment on Darth Cheney’s urging O’Bama to act—“now,” the Old Elephant strenuously implies, “immediately.” Don’t think about it: follow our example: do as we did—summon military might and march off to war, unthinking, uncritical. Morin’s cartoon, while not supplying a single metaphor of ridicule (as does Bagley’s), still exploits the medium’s resources to create memorable imagery that enacts the now-customary criticism of Republicans for being so myopic about their own sins, which they now routinely accuse the Democrats of committing too (without admitting their own kindred culpability). Finally, at the upper left, we have Signe Wilkinson. She doesn’t supply a single, metaphorical image either, but the succession of her images—as we read from left to right—pile up as an indictment of the government’s ludicrous bumbling in caring for its citizens’ health. In a single cartoon with its poster-like imagery, she successfully ridicules the health care predicament while also advocating her preference, which, with the other three pictures as preamble, seems imminently better. Other countries have made national health care with a single-payer work, why can’t we? (We can, of course—and have, with the Veterans Administration. And we have universal health care, too, in Medicare.)

T-SHIRT QUOTES I’m not procrastinating until tomorrow. What I really need are minions. Mathematicians just want their piece of the Pi. The decline of western civilization leaves me strangely unmoved. Patience is a virtue but flipping someone off feels better. Looking for love (but will settle for green jelly beans). I’m not aging: I’m fermenting. When is greed going to be good again? I’m not bossy: you just can’t take direction.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping