|

|||||||||

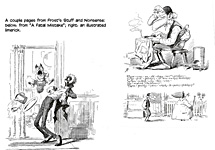

Opus 245 (July 19, 2009). Sucking up most of our picayune prose this time are a scary review of how Michael Jackson’s death was treated in editorial cartoons and a long disquisition on the grand ironies of Disney’s “Song of the South” and the racial controversy still raging about it. But we have space left for Joel Chandler Harris and short reviews of A.B. Frost’s Stuff and Nonsense, George Sprott, Bringing Up Father reprint, scholarly books about Alan Moore and Osamu Tezuka, Art of Harvey Kurtzman, Nexus reprint and graphic novels Lawless and Bad Night, Rick Geary’s Famous Players, J. Edgar Hoover, and the Adventures of Blanche; Power Up, American Jesus, Asterios Polyp, and we finish with Sarah Palin’s finish. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department. NOUS R US: Stan Lee honored at Sandy Eggo, number of strips constant, Arnold Roth in Hall of Fame, Andrews McMeel Universal gears up for the hand-held age, Tim Jackson wins award, Brian Duffy’s survival formula, Robert Short dies, Playboy still shrinking EDITOONERY: AAEC’s annual meeting a little more populous, Roy Peterson gets Golden Spike, Courage Award to Latin American cartooner DEATH WATCH: Michael Jackson and Farrah Fawcett remembered in editoons, newspapers continue shooting themselves in the feet DISNEYFIED ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DISNEY: Mary Poppins, “Song of the South” controversy, Joel Chandler Harris and A.B. Frost NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL: Candorville does Michael Jackson, bad art in the funnies, good art in the funnies, other purely topical art BOOK MARQUEE: Reviewed are George Sprott, Bringing Up Father reprint, scholarly tomes on Alan Moore and Osamu Tezuka, Art of Harvey Kurtzman, Nexus reprint GRAFIX: graphic novels Lawless and Bad Night, Rick Geary’s Famous Players, J. Edgar Hoover, and the Adventures of Blanche; Power Up, American Jesus, Asterios Polyp Bill Hume dies Sarah Palin lumped And our customary reminder: when you get to the $ubscriber/Associate Section (perusal of which is restricted to paid subscribers), don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits Marvel’s rejuvenation of the once-dead Captain America made Entertainment Weekly’s “MustList: The Top Ten Things We Love This Week” for July 17: “Yes, resurrecting beloved characters is a tricky thing , but Marvel knows the art of the relaunch.” Yipe! We’re surrounded by zombies! ... The previous week, the new DVD collection of animated Peanuts specials from the 1960s made the list. ... In the same July 17 issue of EW, we learn that NBC’s “Heroes” will re-appear as a panel at the San Diego Comic-Con, July 23-26, but in a nearby hotel meeting room, not in the Con’s main venue, the city’s gigantic convention center (which I’ll be missing again this year). ... The Hollywood Reporter has announced its intention to honor Stan Lee with its Comic Book Icon Award. The honor, which recognizes Lee's five-decade role in the emergence of comic books as the driving force behind studio blockbusters, will be conferred in conjunction with the Reporter’s Comic-Con special issue and cocktail reception on July 23 in San Diego. "Stan Lee is the master of the genre and that genre has now become the mainstream," Reporter editor Elizabeth Guider said. "We're excited to honor that kind of creative influence." ... According to Rachel Lee Harris, Ryan Reynolds, currently appearing opposite Sandra Bullock in “The Proposal,” will get the power ring to play Hal Jordan, aka Green Lantern, in the forthcoming Warner Bros flick that starts production in January. Reynolds has other comic-book movie credits: besides "Blade: Trinity," the 2004 finale of Marvel's vampire series, he played Deadpool in this year's "X-Men Origins: Wolverine." Editor & Publisher’s Directory of Syndicate Services, the 84th, is out, a much reduced version of the annual publication. Previously, the Directory was a square-spine catalog of 150 or so pages, many of them extravagant fold-in/fold-out multi-page advertisements for individual syndicates, which listed and pictured their columnists and cartoon features on slick stock heavier than the directory pages. It was a cumbersome thing to thumb through, but you emerged with a good idea of each major syndicate’s offerings. This year’s incarnation lacks all syndicate advertising. Not a one has a section boasting its products. And the Directory is now a saddle-stitched magazine of 62 pages, about half its size in yesteryear. In one section of those pages, we find a list of syndicated comic strips—204 of them; in another section, 149 panel cartoons. Despite the gloom and doom infecting newspaper staffs these days. those numbers haven’t changed much. Every year, a few new strips and panel cartoons are syndicated; presumably, a few die off. Births and deaths apparently have achieved an eternal balance. Last year, there were 208 strips; in 2007, 206. There were 143 panel cartoons in last year’s roster; in 2007, 150. A press release from the Society of Illustrators announced that Arnold Roth, famed freelance illustrator and cartoonist, is one of five new inductees elected to the Society’s Hall of Fame. For 50 years, Roth’s work has appeared regularly in nearly every major American magazine from TV Guide and Time to Sports Illustrated and The New Yorker. Contemporary illustrator Paul Davis and posthumous honorees Mario Cooper, Laurence Fellows and Herbert Morton Stoops were also inducted at a black-tie dinner at the Society’s headquarters on Manhattan’s Upper East Side on June 25. Throughout his career, Roth has created memorably antic cartoons, advertisements, album covers and book jackets. He wrote and illustrated six books from 1966 to 1998, including Pick A Peck of Puzzles, A Comick Book of Sports, A Comick Book of Pets and Poor Arnold's Almanac, the complete syndicated series of a newspaper comic strip he produced 1959-61 and again 1989-90. He also illustrated books by George Plimpton and William F. Buckley Jr. and created dust jackets for the John Updike books Bech at Bay, Bech is Back and Bech: A Book. In the late 1950s, Roth’s cartoons began appearing in Playboy, which published 10 multi-page installments of his “An Illustrated History of Sex” series in the late 1970s. He was a regular contributor of cartoon features to Punch from the late 1960s until the end of the 1980s, and had multi-page features in almost every one of the first 25 issues of National Lampoon (1970-1972), until his last satirized the editors of the magazine. Roth also did a stint as an editorial cartoonist and won the Reuben Award at the National Cartoonists Society, of which he was president 1983-85. He’s been recognized previously by the Society of Illustrators with numerous Silver and Gold Stars. Roth’s solo exhibition “Free Lance, A Fifty Year Retrospective” traveled to Philadelphia, Columbus, San Francisco, New York City, London and Basel, Switzerland, 2001–2004, appearing in print in a Fantagraphics book with the same title (and an introduction by Yrs Trly). In a press release, Andrews McMeel Universal announced that it will combine two of its subsidiary operations: Universal Press Syndicate, the largest independent syndicate in the United States, and Uclick, the leading digital entertainment provider of humor, comics, editorial cartoons, daily games and text features for the desktop, Web, and mobile phones, the new duo to be known henceforth as Universal Uclick. Andrews McMeel Universal is now composed of two distinct but collaborative organizations: Universal Uclick and Andrews McMeel Publishing (AMP). Through Universal Uclick and AMP, the news release continued, Andrews McMeel Universal is positioned to offer unique access to multi-channel distribution for authors and artists, and to take advantage of rapidly developing opportunities in syndication and licensing, both in print and in the digital realm. Uclick is the leading distributor of comics and game content on mobile phones, most recently creating more than 130 apps for iPhone and iPod Touch. The apps cover a broad range of entertainment content, including comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels, webcomics, crossword puzzles, word games, and well-known books. Uclick’s GoComics.com offers the largest collection of comics anywhere on the Web, aggregating more than 200 traditional comic strip and cartoon features from multiple syndicates and self-syndicated artists, including webcomic features, all in a single active online community. Fragments of past Rancid Raves issues appear regularly at GoComics, disguised as a blog. The first issue of DC Comics' 12-week anthology series "Wednesday Comics" hit comic bookstores on July 8 in a move meant to recall the days when superheroes patrolled the pages of the Sunday newspaper. "Wednesday Comics,” said E&P, will publish for 12 weeks in a broadsheet format and will include 15 different stories. "It's either old-fashioned or it's cutting edge, or it's a little bit of both," Dan DiDio, executive editor of DC Comics, told New York's Daily News. Some of the highlights of "Wednesday Comics" include a new Superman story drawn by painter Lee Bermejo; a "Batman" strip written by Brian Azarello and drawn by his longtime associate, Eduardo Risso; an update of the 70s character "Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth" by "Watchmen" co-creator Dave Gibbons; and the return to superhero comics of "Coraline" author Neil Gaiman, who will collaborate with artist Mike Allred on "Metamorpho." For the second year in a row, reported Editor & Publisher, Chicago Defender editorial cartoonist Tim Jackson received the Wilbert L. Holloway Award for Best Editorial Cartoon from the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), also known as the Black Press of America. A Dayton, Ohio, native, Jackson began drawing cartoons dealing with social issues when he was still in high school. A 1985 graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, he joined the staff of the Defender in 1999 as a layout artist and began drawing cartoons on local issues for the paper the following year. In addition to his work at the Defender, Jackson draws weekly cartoons for a number of newspapers and magazines, including the Madison (Wis.) Times; Capital Outlook in Tallahassee, Fla.; the Cincinnati Herald and Dayton Defender in Ohio; Northern Kentucky Herald; and the magazine Urban Life Northwest, based in Seattle. From 2006 to 2008, Jackson's cartoons appeared in the Sunday Chicago Tribune's Perspectives section. Jackson is currently working on a book of African-American newspaper cartoonists of the early 1900s, due for publication sometime next year. You can get an idea of the content by visiting his website, which covers the subject as thoroughly as any other; google “Pioneering Cartoonists of Color.” Brian Duffy, who lost his job after 25 years as the award-winning front page editoonist for the Des Moines Register, is now self-syndicating cartoons about Iowa issues to Iowa newspapers. "There is one aspect of cartooning that I have missed,” he explained to the Ogden (Iowa) Reporter, “and that is regularly drawing cartoons that deal with this great state. I have visited many if not most of the towns in Iowa—including Ogden—as a cartoonist and the host of the Register's Annual Great Bike Ride Across Iowa, better known as RAGBRAI. Years ago,” he continued, “when the Register was truly a statewide newspaper, my cartoons and those of my predecessors, Frank Miller and Ding Darling, could be seen in print river-to-river. My goal is to give newspapers and their readers throughout the state a unique feature that they won't find anywhere else." Duffy’s national-themed cartoons will still be syndicated in over 400 newspapers nationwide through King Features Syndicate, and he draws cartoons for the Des Moines weekly newspaper, Cityview. Moreover, his work has expanded to television, with his cartoons incorporating sound and motion on 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. news programs twice a week. Lee Judge, who lost his editooning job at the Kansas City Star last winter and then was reinstated as a part-time employee of the newspaper, won the John Fischetti Award given by Columbia College in Chicago for “excellence in editorial cartooning.” It was his second win of the Award, his first was the inaugural Fischetti given in 1982, but this time, the triumph is particularly sweet. Said Judge, quoted at the AAEC website: “The timing is wonderful. My job has recently become part-time and to win a prestigious, national award like this gives encouragement not only to me but to the people who fought to keep my cartoons in the paper. Editorial cartooning is struggling to survive, not because it lacks popularity, but because it’s often not deemed absolutely crucial. I strongly disagree. If we’re in a battle for readers, why get rid of the one person on a staff best equipped to compete with tv and the Internet?” Dwane Powell, like Judge, has worked out a deal with his erstwhile newspaper, the News and Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina, under which arrangement he continues to produce political cartoons and draws a paycheck. Sounds to me like the paper simply changed its mind; good for them. For all practical purposes, Judge and Powell are now back as full-time staff editoonists, so our running tally of cartooners in that category is 80 again, up two from the all-time low of 78 a couple months ago. Effective July 12, United Feature Syndicate began distributing Scott Stantis’ Prickly City, which had been syndicated by Universal Press. A mildly but nonetheless acute political commentary strip launched in 2004, Prickly City now appears in more than 100 newspapers. The strip focuses on the friendship of a left-leaning coyote pup named Winslow and a young right-thinking girl named Carmen. Stantis, who moonlights as the editorial cartoonist for the Birmingham News, is an unabashed conservative, but while Prickly City offers a conservative perspective on political and social events, Stantis shows he can needle Republicans, too, lately mocking South Carolina’s randy governor, Mark Sanford: when Carmen returns from a covert trip to Argentina smelling of “wet dog,” Winslow believes she was “seeing another coyote.” Despite their frequently opposing views, Carmen and Winslow are friends to the end—Stantis’ comment on the symbionic nature of politics by political party. Robert L. Short, 76, died July 6 in his hometown, Little Rock, Arkansas. Robert was a prolific writer and philosopher, who began an alternate career in 1965 when his book, The Gospel According to Peanuts, became the year's best seller in nonfiction. Translated into 11 languages, reported the Bloomington (Illinois) Pantagraph, “it has become one of the most popular religious books of modern times.” Subsequently, Robert wrote seven other highly successful books of ‘popular theology,’ several based upon comic strips or cartoons, including Peanuts sequels, The Parables of Peanuts (1968) and Short Meditations on the Bible and Peanuts (1990), and The Gospel According to Dogs (2003) and The Parables According to Dr. Seuss (2008). As a paying subscriber to Playboy, I should be incensed enough by the current issue of the magazine to write a seething protest letter to the founder, ol’ Hef hisself. The current issue is a stunning fraud, a blatant attempt to pose as a bonus issue for subscribers while actually cutting costs and content. Dated “July/August,” its cover proclaims this issue a “super-sizzling summer double issue!” “Double issue” implies with little wiggle room that this issue is twice the size of the usual issue. Not so. Logging only 166 pages, the July-August issue is only 37% larger than the February 2009 issue. But Playboy will save production and mailing costs for an entire issue with this “double issue” ploy. The cartoon content of this issue is better than usual, however, due largely to another kind of deviousness. The number of full-page and smaller cartoons, plus strips, is about the same as in February—which, mathematically, means fewer cartoons in this issue—but the “sizzling summer” issue includes a two-page spread of eight B. Kliban cartoons, which raises the total without explaining why Kliban deserves this memorial right now. This issue also includes a 20-page excerpt from the graphic novel adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 by Tim Hamilton, due out in August from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Hamilton, assuming he drew these pages, does an excellent job of deploying the resources of the medium to tell Bradbury’s story—enjoyable and aesthetically satisfying but still shilling for a forthcoming publication and therefore doubtless not very expensive content for Playboy. The 20 pages, while seeming an extravagant indulgence, are reproduced 4 to a page, so the excerpt takes only 5 pages of the magazine. This issue contains two other oddities, morbid reminders of life and death being out of sync with a publication schedule: a profile of Billy Mays, the bearded tv pitchman who died a few weeks ago; and, in a pictorial section commemorating the 1970s, a reproduction of the famed Farrah Fawcett poster. Mays commercials, by the way, will continue to appear “for the indefinite future,” according to the Associated Press, “and at least one of his commercials is being introduced posthumously.” Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted An irony that can scarcely be overlooked in a profession that trades in irony befell the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) July 1-4 at its annual convention in Seattle: the number of full-time staff editoonists has dropped by 20% over the last year, but attendance at the convention stayed about the same as last year—109 this year, 107 last year. According to reports now filtering in to the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer, of that number only 57 were cartoonists; the rest, spouses and other hangers-on from syndicates and related enterprises. But last year the number of cartoonists was only 44, so one could say that this year, attendance was better than last year. Of this year’s 57, only 29 work full-time as cartoonists, and of that number, only 18 are full-time on a newspaper staff. Among the full-time cartoonists not on a newspaper staff (by way of explication), Daryl Cagle, who cartoons but also runs a website and a syndicate; Mark Fiore, who freelances animated editoons; Wiley Miller, who produces a comic strip, Non Sequitur. Over-all membership in the association has wavered rather dramatically: in 2007, it stood at 392; in 2008, 473; and this year, it’s 350. The decline, however, may be due to purging the rolls of ostensible members who haven’t paid their dues for years. Last year the number of “regular” members—as opposed to associate, student, and retired—stood at 328; this year, it’s 253. The association, meanwhile, has begun to dig itself out of the financial hole it pulled in on itself with its somewhat extravagant 50th anniversary celebration in Washington, D.C. two years ago: AAEC has money in the bank again. At its business meeting, AAEC confronted several wild-eyed ideas that have been floating around in recent years—among them, becoming a guild (union) or merging with another association (most often mentioned, the National Cartoonists Society; the possibility of a joint meeting, however, is still alive)—and deflated them. Sessions on the program wove through a tapestry of topics—the future of editoonery in online journalism, whether altie cartooning is the next thing, what about syndication, animated editooning, and graphic novels. At the concluding banquet, Roy Peterson, Canada’s famed political cartoonist and national institution—recently fired, after 47 years, by his newspaper, the Vancouver Sun—received the Golden Spike Award, presented annually to a cartoonist who drew the most memorable cartoon killed by an editor. Peterson deserved this year’s accolade for the cartoon he drew announcing his departure; his editor invited him to produce a “farewell” cartoon but then declined to publish it. Peterson drew himself in caricature, carrying a sign reading “The End is Nigh” as he steps in the direction of an open manhole in front of him; he’s carrying a newspaper with headlines that read: “Cartoonist terminated....” The Vancouver Sun, in announcing Peterson’s departure from the paper, didn’t say the cartoonist was fired; nor did it say he was retiring. It said, merely, that he was leaving. Peterson’s farewell cartoon violated the newspaper’s unspoken posture with respect to his departure: the Sun clearly hoped Peterson could be slipped off into the night without anyone noticing. Upon accepting the Golden Spike, Peterson said he was honored. “Or maybe not, considering ...” ***** Mario Robles, who works for the Oaxaca, Mexico, newspaper Noticias Voz e Imagen, won this year's Award for Courage in Editorial Cartooning from Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI), a free speech and human rights organization dedicated exclusively to the needs of political cartoonists. Editor & Publisher noted that Robles is the first Latin American cartoonist to win the award, which was announced by CRNI President Joel Pett of the Lexington (Ky.) Herald-Leader during last week's annual AAEC convention. The award was accompanied by this citation: "Robles was assaulted on last April 19 for a cartoon that made fun of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) over a crackdown on public demonstrations. According to the human rights organization Article 19, local agents of the PRI party approached Robles and started kicking him, leaving him with visible wounds. They said he should stop drawing such critical cartoons or they would kill him and his family." Robles, a veteran cartoonist with 30 years experience, has won the top journalism award in Oaxaca six times. Pett noted that Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries for journalists. According to a 2008 report from the Committee to Protect Journalists, at least 24 journalists have been killed, eight in direct retaliation for their work. Seven others have disappeared since 2005. E&P also reported that a Honduran cartoonist was released early in July after being arrested and detained for 24 hours by that country's military authorities. Allan McDonald and his 17-month-old daughter were taken by the Honduran Armed Forces, who then ransacked the cartoonist’s house and destroyed McDonald's drawing materials and cartoons. “McDonald,” E&P continued, “has published several cartoons in the newspaper Diaro el Heraldo de Honduras and on the Web site Rebellion.org in support of ousted Honduran President Manuel Zelaya,” who was overthrown last June 28 by the country's military after he insisted on a referendum that would allow him to seek a second term of office. McDonald was detained with 15 other people, including two female journalists from Spain and Chile. DEATH WATCH A Crotch Too Many The week of June 22 began with nothing more earth-shattering than the 72nd anniversary of my birth, but excitement quickly mounted for editorial cartoonists, who eagerly turned away from the mess in Iran, congressional quarreling over health care legislation, U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq’s cities, and O’bama’s pending summitry in Russia for the more relaxing and crowd-pleasing task of drawing obit cartoons for Ed McMahon, Farrah Fawcett, Gale Storm (1950s tv star of “My Little Margie”), pitchman Billy Mays, and, the ultimate dead man with face to match, Michael Jackson. MJ’s surprise departure a few hours after Farrah left us on June 25 quickly eclipsed all the others. On cable tv, a 24/7 loop began that Thursday and didn’t stop for nearly two weeks, until after memorial services on July 6 (or was it on the 7th?—awash in maudlin sentimentality, I forget). According to report, at the AAEC convention in Seattle, Michael was on tv in every bar and lobby, prompting editoonists to quip, whenever they entered a room, “Michael Jackson’s still dead, I see.” An almost perfect summation of how the 24/7 obsession of cable tv’s so-called news media had shut out reporting any news whatsoever. Not even Sarah Palin’s resignation, sensational though the news media tried to make it appear, drove Michael from the airways for more than a minute or so every news cycle. American editorial cartoonists were nearly universal in commemorating MJ’s departure with pictures of him dancing his iconic dances. Almost all, in other words, were respectful. Of those I saw, consulting Daryl Cagle’s political cartoon site, cagle.MSNBC.com, only a couple remembered that Michael had a dark side that included credible accusations of pedophilia and a self-loathing that inspired him to spend his money on cosmetic surgery to change his appearance from beautiful African American (think of him in the 1980s) to a ghastly caucasian caricature. He was, said Linda Stasi in the New York Post, “a twisted sicko ... a disgustingly depraved man.” Mike Luckovich was one of few—maybe only two—U.S. cartoonists who remembered Michael’s unsavory private history as well as his soaring performances on stage. Brian Fairrington was the other. Both appear first in the accompanying array of editoon obits.

Otherwise, American editoonists pandered to the popularity of the King of Pop. Overseas, however—as we can see in the samples assembled nearby—cartoonists in other countries were not so reticent in acknowledging the mixed message of MJ’s unhappy private life and his misbegotten public persona. Stephen King in Entertainment Weekly’s special MJ issue (July 10) provided the most poignant portrait of the pop star, naif, confused manchild in the voracious empire of entertainment. Recalling their collaboration on “Ghosts,” King wrote: “He phoned my wife, wanting the phone number for wherever I was that day. She gave it to him. Michael called back five minutes later, on the verge of tears. He hadn’t had a pencil, he said, so he’d tried to write the number on the carpet with his finger, and he now couldn’t read it. My wife gave him the number again. Michael thanked her profusely, but never called me.” At the MJ memorial, the Rev. Al Sharpton demonstrated that his gift for hyperbola is no longer legendary: he made it manifest by claiming that Michael Jackson was responsible for Barack Obama being elected President. MJ’s popularity in the 1980s was so pervasive, so universal, Sharpton alleged, that it fostered a couple generations of fans “who grew up from being comfortable” with an African American icon and who, then—now in their forties—were “comfortable to vote for a person of color to be the president of the United States of America.” The excess of the mourning over Michael was such that no one questioned the absurd extravagance of the claim. Besides, in leaping to a racist-serving conclusion, Sharpton forgets that MJ tried to turn himself white, to escape being an African American. Probably, as Argus Hamilton observed, many of Michael’s fans didn’t even know he was African American. For

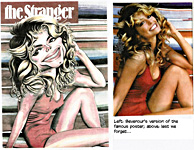

my money, the best editorial cartoon commentary on the grief-besotted

week was the Jay Bevenour’s cover for The Stranger, a free altie weekly in Seattle, sent to me by a dedicated Rancid

Raves operative. ***** If a generation of Michael Jackson fans put Barack Obama in the White House, what did a generation of fans’ ogling Farrah Fawcett’s cheery teeth and protruding nipples accomplish? ***** Damnation from the Ages. Here we’ve excerpted a few paragraphs from an article written in 2007 by Tony Dokoupil for the Columbia Journalism Review. It’s surprisingly appropriate, still. Herewith: Newspapers Are Killing Cartoonists—Another Brilliant Business Move It’s been fifty years since The Saturday Review declared American editorial cartooning a moribund art. In the three-page autopsy, the magazine’s staff coroner of all things cultural, Jerome Beatty, argued that the cartoonist’s lifeblood had been quieted by taboo-conscious editors who bent “over backwards” to avoid offending readers, publishers, and advertisers. Eager to display a pulse, cartoonists responded by setting up the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC), and throughout the following decades punctuated a professional renaissance with strong and consequential drawings. ... But what troubles today’s publishers and editors is less a matter of subtlety than cost. Faced with declining advertising revenues and evaporating print audiences, newspapers increasingly opt to buy cartoons through syndication, which offers access to hundreds of cartoons for as little as $35 a week, compared to more than $35,000 a year for a staffer. Faced with such an opportunity for savings, many penny-pinching outlets forget loyalties and lose their honor fast. ... A full accounting of what is lost with the dwindling number of staff cartoonists is difficult to measure. Cartoons excite readers in ways that editorial essays can’t. Their simple strokes allow complex ideas to bypass the mind and kaboom through the nervous system, offering instantaneous understanding, and depending on one’s personal politics, an unalloyed dose of pleasure or pain. That’s one big reason why the vast majority of U.S. papers still float funny panels between banks of gray prose: they poll well with readers. However, that may change. Over the last few years, an unlikely alliance of academics and AAEC members has emerged, publicizing the downsides of the industry’s diminishing support of cartoonists. They say that newspapers are committing the editorial equivalent of weight-loss through limb removal, a metaphor that dominated “Blank Ink Monday” on December 12, 2005, when dozens of cartoonists expressed through images “the wholesale weakening of the daily newspaper” due to layoffs. ... Hitting the high points, this unofficial union of ponytails and tweed jackets maintains that syndication tends to discourage controversial work and reward vanilla gags. The game is one of pleasing the greatest number of readers rather than distinguishing oneself through editorial fireworks, and the result is “a cartoon graveyard” on most editorial pages, according to Pat Oliphant. ... At a time when the “fake” news of “The Daily Show” and the false certainty of “answer” shows like “Lou Dobbs Tonight” are ascendant, it’s surprising that newspapers aren’t expanding their investment in smart cartoons. After all, editorial cartoons offer a print equivalent of easy-to-absorb punditry and satire, and in this multimedia world, are ideally suited for the Web. What’s more, in an age of political theatrics and shape-shifting stagecraft, cartoonists can take us past surfaces and behind masks to reveal truths that photographers can’t capture. ... No wonder the columnist H.L. Mencken said, “Give me a good cartoonist and I can throw out half the editorial staff.” ***** Best Foots Forward. Meanwhile, on June 22 at the Daily Universe, campus newspaper at Brigham Young University, the editors stepped up admirably to state the role of both editorial cartoonists at the paper and the function of the editors; herewith portions (in italics): The first thing most people look at when they open to the issues and ideas page is probably the cartoons. Faithfully in the top right corner, the editorial cartoons often serve to amuse, enlighten or infuriate our readers in a few short seconds. Unlike letters or opinion columns which take more effort to absorb, cartoons are a simple way to see a particular point of view. Recently, a reader wrote a letter concerning our choice of cartoonists, calling some of the more conservative cartoons mean-spirited and one-sided. The reader pointed out what he perceived was an imbalance of conservative to liberal cartoons. ... We want to make it clear that individual cartoons published in The Daily Universe represent the opinion of one person, one “side” or one group of people. They do not represent the opinions of The Daily Universe, BYU or the LDS Church. At the newspaper, we strive to remain objective onlookers, even on the issues and ideas page where opinions are far from balanced. Our goal is to create an atmosphere for discussion and debate, and we often receive letters from people who disagree with cartoons, columns or other readers. ... In an effort to be more balanced, we are dropping the cartoonist Clay Jones [who calls himself “an unreliable conservative”] and replacing him with liberal cartoonist Steve Sack. We will continue to publish cartoons from conservative cartoonist Bob Gorrell. The editorial board made this decision after reviewing cartoons from a number of liberal cartoonists. We hope our readers understand we do not intend to represent any single side on any issue. Cartoons, columns and letters to the editor are not haphazardly put in the paper to fill space, but they are selected based on how much they will benefit and add to an open discussion for the BYU community. If there is any cartoon, column, letter to the editor or idea found in The Daily Universe that our readers find the need to call into question, we invite them unreservedly to write in, voice their opinions and act as a check on our objectivity. THE WHOLE PLEASANTIFICATED DISNEY The Third Edition (2008) of Disney A to Z: The Official Encyclopedia arrived the other day (770 7x10-inch pages, with a generous smattering throughout of tiny b/w pictures plus a 16-page color section, the latter, mostly photographs of Disney theme parks; $40). Apparently the life work of Dave Smith, director of the Disney Archives, the book ostensibly covers every aspect of the Disney enterprise from, well, A to Z, but, like Disney’s films, it has been completely Disneyfied: it leaves out anything vaguely unpleasant with the bland result that it also omits a lot that would have been simply informative. “Mary Poppins” gets one small (2 ½ x 1 ½ inch) illustration— cartooned versions of some of the characters—and two columns of type, which mostly list the actors in the movie. P.L. Travers, who wrote the original children’s books upon which Disney based his film version starring Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke, rates a whole sentence that tells us she kept writing Mary Poppins adventures long after the “lavish premiere” on August 27, 1964, but nothing is said about either her stubborn refusal to grant Disney permission to make the film or Disney’s persistence in obtaining it. And it’s stretching matters somewhat to claim that Travers continued writing Poppins books after the movie appeared: Travers wrote only five Poppins books, beginning with the first in 1934, and four of them had been published before the Disney movie; only one, the fifth, Mary Poppins in the Kitchen, appeared after the movie, admittedly “long after,” that is, in 1975. Caitlin Flanagan wrote a long piece about Travers and Disney and their uneasy, not to say hostile, relationship in The New Yorker, December 19, 2005, which is accessible through Google or Wikipedia. In it, Flanagan divulges the tantalizing information that the Poppins books were all illustrated by the daughter of famed Pooh illustrator, the Punch cartoonist Ernest Shepard. But Travers was as merciless in dictating to Mary Shepard about how to draw as she was in advising Disney about how to make movies: “The first thing that has to go,” she told the man who virtually invented the animation industry worldwide, “is the animation sequence.” This advice she offered at the party held after the 1964 premiere. Disney looked at sixty-five-year-old spinster whom he had courted for a dozen years or more and said: “Pamela, that ship has sailed.” And “then he strode past her, toward a throng of well-wishers, and left her alone, an aging woman in a satin gown and evening gloves, who had traveled more than five thousand miles to attend a party where she was not wanted.” The sentence alleging that Travers continued to write Poppins books after the movie came out is intended, doubtless, to mask the hostilities between the author and the movie-maker, suggesting that Travers went blithely on, no hard feelings, writing book after book, despite the “rumored” bad feeling the Disney film aroused. Under “Mickey Mouse,” we see that the world-famed rodent made his film debut in “Steamboat Willie” on November 18, 1928, but Smith neglects to mention the most historic fact about this debut: it was the first sound animated film, and the sound, probably more than Mickey’s behavior (he wasn’t very cute therein), made the film, and the character, a huge success. But you wouldn’t know it from this entry, which concludes with a list, by year, of all 120 Mickey short cartoons. Not surprisingly, no mention of the long-drawn-out law suit over Winnie the Pooh under “Winnie the Pooh.” Surprisingly, Dave Smith gets a photograph of himself with the theme park Mickey Mouse and a list of his half-dozen books about Disney, beginning with The Ultimate Disney Trivia Book of 1992; and we find out he’s been director of the Disney Archives since 1970. Disney’s first partner and, ultimately, the studio’s most notable innovator, Ub Iwerks, gets a decent write-up. He and Disney met in Kansas City in 1920 and set up their own animation studio, Iwerks-Disney. “Originally, they had thought to call it Disney-Iwerks, but that sounded too much like a place that manufactured eyeglasses”—a nice flash of wit amid the otherwise pedestrian plodding prose of a Serious Reference Work. The period of Iwerks’ defection from Disney, 1930-1940, is covered by saying it was ten years long; we don’t know what Irwerks did during that decade (he started his own studio) or that he created an animated character of his own called Flip the Frog. “Song of the South,” the studio’s “first major plunge into live-action filmmaking” in 1946, is described but no mention is made of the racial controversy that subsequently enveloped the film, eventually all but suppressing it. The movie combined live-action with animation—the former depicting the African American storyteller Uncle Remus; the latter, the antics and adventures of Remus’ “critters,” Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox et al. The redoubtable James Baskett received an honorary Oscar for his portrayal of Uncle Remus, but in the ensuing Civil Rights movement, Baskett’s plantation storyteller was quickly dubbed a condescending stereotypical racist caricature. The gruesome details are rehearsed by Jim Korkis in his exhaustively researched article in Hogan’s Alley, No. 16, the 2009 edition of the annual magazine. Walter White, executive secretary of the country’s foremost racial equity advocacy organization, issued a statement: “The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People recognizes in ‘Song of the South’ remarkable artistic merit in the music and in the combination of living actors and [animation]. It regrets, however, that in an effort to offend neither audiences in the north or south, the production helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery. Making use of the beautiful Uncle Remus folklore, ‘Song of the South’ unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts.” Although the movie is set in the post-Civil War reconstruction South, Disney didn’t emphasize the time period, leaving an impression with a casually viewing audience that the action took place during the years of plantation slavery. But perhaps that didn’t matter so much. An NAACP staffer who viewed the film found it “so artistically beautiful that it is difficult to be provoked over the cliches,” but she pointed out that the movie contained “all the cliches in the book”—happy black field hands singing spirituals together, for instance. Various ethnic groups picketed the movie when it opened in major cities. Time magazine’s critic wrote: “Artistically, ‘Song of the South’ could have used a much heavier helping of cartooning. Technically, the blending of two movie mediums is pure Disney wizardry. Ideologically, the picture is certain to land its maker in hot water.” Not everyone, however, jumped on the band wagon of accusation. In the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s leading black newspapers, we find Herman Hill saying: “The truly sympathetic handling of the entire production from a racial standpoint is calculated ... to prove of estimable good in the furthering of interracial relations.” And he then goes on to discuss the negative reviews by Ebony and other critics, finding their comments to be “unadulterated hogwash symptomatic of the unfortunate racial neurosis that seems to be gripping so many of our humorless brethren these days.” Times, it seems, haven’t changed us much, alas. Ironies abound. Korkis reminds us that in 1946 when the movie debuted, the entertainment media were entirely devoid of portraits of “normal” African Americans—no Huxtable family—but were, rather, awash in images of comical “lazy, slow-witted, easily scared” eyeball-rolling, foot shuffling blacks of the perpetual servant class. The country was profoundly racist: lynchings occurred regularly, and segregation prevailed in the South, where there were theaters for whites and theaters for blacks; ditto lunch counters, waiting rooms at train stations, and drinking fountains. President Truman wouldn’t issue an executive order aimed at ending segregation in the military until 1948. In this environment, Korkis says, Disney’s movie was startlingly innovative not only technically, “blending live action and animation, but also for its depiction of black and white children playing together as equals and its story in which the black characters are wise and caring while the white characters are often cruel, insensitive or dysfunctional.” Disney was well aware of the temper of the times, and he set out deliberately to produce a movie that would affirm the humanity of African Americans. To write the screenplay, he unfortunately picked a Southern writer, Dalton Reymond, because he was regarded in Hollywood as an authority on the Deep South. Reymond admired the Uncle Remus canon because “they are stories of a gentle old negro and a little boy; of how an old man, through his stories and his human understanding, brings happiness to a little boy, whose life is troubled.” Reymond’s head may have been in the right place, but his heart was full of Southern stereotypes with which he laced the strip. When Disney became aware of Reymond’s tendency, he hired a countervailing collaborator, Maurice Rapf—a Jew and a radical—telling the new guy that he was to remove potentially objectionable material. When Rapf demurred, Disney reassured him, saying he’d hired him precisely because he was opposed to making the movie. “You’re against Uncle Tom-ism,” Disney told him, “and you’re a radical. That’s exactly the kind of point of view I want brought into this film. I want you to prevent it from being anti-black.” The final irony is that the Uncle Remus stories are about slave resistance. Br’er Rabbit is a folk hero to the slave population of the Old South: he “symbolized the smaller, less powerful black man,” the other critters represent the oppressive whites, “and the stories were all about how to outwit the masters.” Despite all Disney’s best intentions, his movie offended many black Americans. Astonishingly, given the brouhaha about “Song of the South,” it was re-issued four times—1956, 1972, 1980, and 1986. But Dave Smith makes no mention of any of this. He hews to the Studio line, favoring innocuous entertainment and harmless information. Relentlessly bland as it is, Disney A to Z still probably the only reference on the Disney endeavors with aspirations to being comprehensive, even if it does leave out unpleasantnesses and a lot of otherwise thought-provoking fact. ***** Treasure Hunt. Some years ago, I started trying off and on to find a videotape of “Song of the South” without much luck. A Japanese language version was around, I found out, but it didn’t sound too appealing. Then on one of my periodic visits to Denver (where I now live but I was then just visiting my daughter in law school), my wife and I went to dinner at the Buckhorn Exchange, an old restaurant down by the train tracks to which nineteenth century railroad workers would repair on payday: if they cashed their checks there, they’d get in exchange (hence the name) a token good for a drink. Buffalo Bill frequented the place even though he didn’t work on the railroad. And trophies reminiscent of his past as a slayer of buffalo adorn the walls—stuffed heads of as many animals as you’d care to name. All of which is beside the point, which I’ll now get to. After dinner that evening, we went upstairs where a folksinger was holding forth to a small crowd. (The room would hold only a small crowd.) After singing a few numbers, he wondered if anyone could name the movie his next song came from, and he sang "Zip-a-dee-do-dah." I, naturally, named the movie. “Song of the South.” During the break between sets, I went up to him and told him I’d been looking in vain for a videotape of the movie. Without further prompting, he said: "I know where you can get one." And he took out a pencil and wrote a phone number on a piece of paper. Giving it to me, he said, "Just call this number." When I got back to Illinois, I phoned the number. It was someplace in the south—one of the Carolinas, I think. When a man answered the phone, I told him I’d heard he had vidoetapes of "Song of the South" to sell. "I sure do," he said. "Lemme tell you how I got them. I went to a flea market one time, and just inside the entrance, a young man had set up a card table upon which he’d piled several videotapes of ‘Song of the South.’ How many of these do you have, I asked him. And when he told me, I bought them all." "Wow," I said. "Do you have any left?" "Sure do," he said, "—give me your name and address and I’ll send one to you with a bill." "Don’t you want me to pay by credit card or send you a check before you send it off?" I said. "Nope," he said; "my experience is that anyone who wants a copy of ‘Song of the South’ can be trusted to pay when I send the invoice." And that’s how I got my videotape of "Song of the South." I confess, though, that I’ve never watched the whole thing: I fast forward through the live action to get to the animation. Every time. So I miss being indoctrinated by the racist portrayal of Uncle Remus. If current attitudes about race preclude Uncle Remus from ever again appearing on the screen, why not just take him out: by piecing together just the animated sequences, we could get a nifty short animated film about Br’er Rabbit and his voracious pals, the cunning Br’er Fox and the colossally stupid Br’er Bear. It’s some of the best animation Disney ever did. And judging from the occasional prolonged glimpses I had of Baskett at work, Uncle Remus is well done, too. These days, you can get the movie on DVD through several websites; just google the title. ***** Harris and Frost. The ironies surrounding Disney’s movie about Uncle Remus and his Br’er Rabbit ensemble are not the only ironies clustering around Joel Chandler Harris’s work, which was, Jim Korkis says, “second in popularity only to Mark Twain.” Harris, a man whose shyness was very nearly disabling, started working as a columnist and editorial writer at the Atlanta Constitution in the fall of 1876. Shortly after arriving, he was given the assignment of continuing the newspaper’s occasional column about “an antebellum darky” who drops in to the newspaper office from time to time, making comical comments on the passing scene. Although Harris named the character Uncle Remus, this was not the Uncle Remus who told animal tales; that Uncle Remus didn’t appear until three years later on July 20, 1879. He quickly became so popular that his stories were reprinted in other papers across the South. In November 1880, a collection of the stories was published with the title Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings. Robert Hemenway, introducing a 1982 edition of the volume, says Harris’s book “found instant praise” for its supposedly accurate “pictures of genuine Negro life in the South” during the painful Reconstruction period. Harris would be repeatedly commended for the authenticity of the dialect he gave Uncle Remus, which Harris always professed was not his invention any more than the animal stories themselves: as a teenager in the mid-1860s learning the printer’s trade by working on the only newspaper ever published on a plantation, a place called Turnwold, he’d heard the stories told by an assortment of black storytellers. Later, in his Uncle Remus tales, Harris sought to reproduce exactly what he’d heard in both content and manner, and modern scholarship has largely confirmed the accuracy of his effort. “Although Uncle Remus has a place in the gallery of racist stereotypes that includes Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben—and Harris held a full complement of the racist views of his age [coupled to a generally humane and compassionate attitude]—there is a danger of throwing out the tar baby with the bandana,” Hemenway writes. Harris produced seven more collections of Uncle Remus stories during his lifetime—and two more were published posthumously—and as he spun his tales, Harris believed he was helping to heal the wounds left by the Civil War, and Hemenway agrees: “Uncle Remus became a historical instrument promoting closer bonds of sectional harmony, representing an image of black people around which Northern and Southern whites could unite. Harris borrowed Uncle Tom’s faithfulness but did away with his harsh masters, took the minstrel’s grin but added a loving demeanor, affixed to them his hazy, romantic memories of life at Turnwold, and created a figure who could contribute to the counry’s reunification. Uncle Remus reassured Southern whites about their darkest fears: free black people would love, not demand retribution. ... Uncle Remus, immensely popular, witnessed that black people would turn the other cheek, would continue to love, despite all the broken promises of American history. Invented as Federal troops withdrew from the South, Uncle Remus was the perfect figure to allay Northern uneasiness about their abandonment of the Negro. Uncle Remus promised the North that Southerners could see the Negro’s virtues and could even celebrate them, which was proof that rehabilitation had occurred and that force was no longer necessary to ensure that black people would be treated with justice by their former masters.” Uncle Remus, a romantic and wholly unrealistic portrait of a life among blacks and whites in the ante-bellum South, represented a kind of hope for Southerners, Hemenway says. In his gentle and loving demeanor, Uncle Remus, “an ‘old time Negro,’ reminds Southerners of what was ‘good’ about slavery [that mythical and benign fellowship that prevailed between master and slave in the popular albeit misguided conception of a happy, singing plantation South], becoming a wish-fulfillment fantasy for a populace forced to deal each day with black people considerably less docile than the plantation darky. Remus’s dialect especially supports this fantasy”: his language “is colorful but ignorant,” suggesting “that black people are picturesque but intellectually limited,” scarcely a threat to the white social order. And the dialect helped to sustain Br’er Rabbit’s role as a revolutionary folk hero for whites as well as blacks: “Black Br’er Rabbit could only be assimilated into the culture of a post-slavery America through the mouth of a quasi-Negro [who, by displaying in his speech a harmless ignorance, reassured] white readers [who] desperately needed to defuse the stories’ revolutionary hostility.” Br’er Rabbit “embodies a revolutionary consciousness which says that one need not accept the world as it is, that any individual, working with the mother wit at hand, can change things. This revolutionary quality makes Br’er Rabbit a universal figure. Br’er Rabbit expresses archetypes of human emotion because one identifies with his liberating sense of anarchy—an imperative of liberation embedded deep in African American history. ... One arrives at the universality of the Br’er Rabbit tales by examining the ways in which we are all oppressed, the limits placed upon us, the need we all have for a psychic drainage system.”. The ultimate irony is that Uncle Remus and his creator are both denigrated these days for perpetuating a portrait of a gentle African American with a loving slave mentality, the very attributes that made Uncle Remus and his tales instrumental in helping a sundered nation reunite. In 1895, Uncle Remus’ publisher, Appleton, brought out a new edition of Songs and Sayings embellished with illustrations by A.B Frost, who, by 1895, was well-known as an illustrator with a comedic bent, just the sort of artist to illuminate Uncle Remus’s humorous tales. He and Harris would eventually become close friends, and Harris welcomed Frost to the Remus milieu with admiration and gratitude, writing in his dedicatory preface, addressed specifically to Frost: “It will be no mystery at all if this new edition were to be more popular than the old one. Do you know why? Because you have taken it under your hand and made it yours. Because you have breathed the breath of life into these amiable brethren of wood and field. Because, by a stroke here and a touch there, you have conveyed into their quaint antics the illumination of your own inimitable humor, which is as true to our sun and soil as it is to the spirit and essence of the matter set forth. The book was mine, but now you have made it yours, both sap and pith. Take it, therefore, my dear Frost, and believe me [to be], faithfully yours, Joel Chandler Harris.” By this time, Frost had established himself as an innovator in rendering “time-stop drawings” in sequence—comic strips. As Thierry Smolderen writes in introducing a Fantagraphics reprint of several of Frost’s works: “Almost twenty years before the birth of the comic strip in the U.S. daily newspaper, Arthur Burdett Frost was using the term ‘comics’ for the short stories he published in various magazines of the day.” In 1884, Frost had published Stuff and Nonsense, an anthology of his pen-and-ink renderings that included the legendary “Fatal Mistake,” a pictorial record of what transpires with a cat that mistakenly eats poison, made hilarious by “a dynamic trajectory of starts, crescendos, pauses, and clashes,” Smolderen says. Fantagraphics’ 2003 tome (203 10x13-inch pages, b/w; hardcover, $24.95; jointly published in France by Editions de l’An 2, which added subtext in French throughout) reprints Stuff and Nonsense, combining it with two other classic Frost comic sequential art productions, The Bull Calf and Other Tales (originally published in 1892) and Carlo (1913), a long narrative about a mischievous and misunderstood dog of Napoleonic proportions. The page size of the original Stuff and Nonsense, 7x10 inches, is smaller than this re-issue, but Frost’s pictures in it appeared one to a page; in the reprint, they’re two to a page, the drawings themselves slightly enlarged. Blowing up the pictures makes Frost’s more fragile lines infinitesimally fatter, but this slight imperfection is not terribly noticeable. And you cannot find any of these Frost masterpieces anywhere in comparable quality (the production values here are exquisite) for a comparable price.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Darrin Bell devoted five of his Candorville strips (July 6-10) to Michael Jackson’s death, but he scarcely deified the Princeling of Pop. The series proved Bell more daring and candid than most of the nation’s editorial cartoonists, who almost all opted to follow the country’s sympathetic flow like so many dead fish. Bell’s sequence was also sympathetic with MJ’s unenviable fate as a small boy thrust onto a national stage at an age too abbreviated to know what was happening to him. The poignant conclusion on July 10 is one of the most memorable moments in comic strip history. What we saw in the paper, however, was not quite what Bell originally devised for the sequence. The second strip as published was the “corrected” version. In our array, we’ve presented the whole series, including the censored strip (that’s the larger than life one).

At his website, candorville.com, Bell discusses his predicament and his solutions: “My editor sent me an email a few days before [the July 7] strip was going to press saying ‘I can’t let you do this.’ It had all the urgency of an intervention. My editor was refusing to let me OD. She was pouring my vodka down the drain. Apparently jokes about pedophilia, even mild ones like this, aren’t allowed on the comics page. But thank God for the Web!” At his website, Bell posted the censored version, which we’ve inserted into the sequence here. Said Bell: “I had to come up with something that would fit the existing art and I had about ten minutes in which to do that. It still works. In fact, all I did was replace the offending last two panels with an earlier draft of the strip, so this is still something I wanted to say. I like it more than I did when I grabbed it from my notes in a mad rush to meet the deadline. You might even prefer it. The edited version removes all jocular (funny word to use, considering… oh never mind) references to Michael Jackson’s questionable relationship with small boys. In fact, they even removed ‘your possible depravity’ from panel three in a second round of censoring. ... Some believe that’s for the best because he was never convicted and because he’s dead and should be left alone. But the uncensored version of the strip doesn’t assert that he was guilty. What it does is acknowledge that people have questions about him that are impossible to answer because of his own actions. He went through a child molestation trial and settled out of court for $20 million. Whether he was innocent or not, inviting young boys to sleep with him after having gone through that was a stupid and naive decision. I bought his story. But I have to admit that as much as I admire him and his music, he handed people who don’t believe him plenty of reason to doubt his veracity. And I’ve never believed that we should only speak well of the dead. That’s dishonest.” Some MJ fans—and Candorville fans—asked Bell if he could make available a poster of the sequence, and on his website, he’s offering just that, an 11x17-inch poster with all five strips. If enough people order one, he’ll order a print run; otherwise, he’ll refund the money. ***** BAD

ART. Comics, whether in strips in newspapers

on in pages in comic books, are a visual artform, so from time to

time here at Rancid Raves, we’ll take a few moments to critique

the drawings we see in strips. We’ll begin with Doonesbury,

with which Garry Trudeau, as he has often and famously said, made comics safe for bad art. That

statement is no longer true: since returning from his heralded

sabbatical some years ago, Trudeau has been drawing better than he

did when he first landed in the funnies, imitating Jules

Feiffer’s casual, sketchy manner. He

once explained the change by saying that his previous manner of

drawing was, ultimately, boring him; the more elaborate the

drawings—poses, angles, silhouettes—the more interested

he stayed. My criticism of the art in Doonesbury these days is restricted entirely to Trudeau’s way of depicting

Michael Doonesbury, the guy doing most of the talking in the

accompany strip; to wit, what the hell are those round things just

under his eyes on either side of his nose? One

of the champions of bad art these days is Jeff

Corriveau in Deflocked,

his strip about a small boy and a small herd of anthropomorphic

animals on a farm. Another

of the bad art champs is Stephan Pastis in Pearls before Swine. Chip Dunham in Overboard commits another of bad art’s signatures: running one solid black shape into a solid black background. A variation on this sin is to run two solid black shapes, one superimposed upon the other so the whole thing is a solid blotch of black. Dunham’s habitual predicament, however, is in rendering the mice in the strip: they are drawn so small and with such a thick line that they appear as squashed spiders. Dunham adds to the mishmash of the strip’s appearance by adding shading in a variety of methods, diagonals one way, then diagonals another way. Visual cacophony ***** GOOD ART. In sharp contrast, we conjure up next some examples of good or careful drawing in comic strips.