|

|||

Opus 240 (April 8, 2009). Headlining this time, we have a long essay on the inner workings of Alan Moore’s Watchmen, both graphic novel and movie, a funeral dirge for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the latest daily newspaper to succumb to corporate greed— and how its edtioonist David Horsey avoided being buried alive—an update on the tally of editorial cartoonists being fired, and reviews of Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Joe Shuster, Fantagraphics’ Humbug reprint, and funnybooks Soul Kiss, some Batbooks, The Great Unknown, Frank Frazetta’s Moon Maid, Bang! Tango, and Patsy Walker Hellcat, plus the usual survey of newspaper funnies and other evidence of the passing scene, including a stunning photograph of Chuck Rozanski ripping his clothes off in a pumpkin patch. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS

R US: Various economic fallouts, no comics at a comic-con, New

York Times makes

a mistake, Dave Astor’s HuffPost column sampled, Ziggy’s

depression, help for S. Clay Wilson please, Simpsons postage stamp,

Australia’s cartoonist of the year, 3-D animations galore,

Oliphant and the Anti-Defamation League Post-Intelligencer

Closes; Horsey Goes On—How Is That Possible? DEMOLITION DERBY CONTINUES: FIVE NEW EDITOONIST CASUAlTIES Alties

Faring No Better Jungle

Girl and Frank Cho Dick

Tracy Escapes Another Death Trap WATCHMEN

AND THE MOVIE NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL:Sherman’s Lagoon, The Knight Life, Mort Park’s death in Rudy Park, death and disease in Funky Winkerbean, some drawing skills, Family Circus repeating itself, new artists on Adam @ Home and Grand Avenue, and more BOOK

MARQUEE: Shuster’s book of kink, Fantagraphics’ Humbug reprint FUNNYBOOK

FAN FARE: Reviews of Soul

Kiss,

assorted Batbooks, The

Great Unknown, Frank Frazetta’s Moon Maid, Bang! Tango, and Patsy Walker Hellcat And

our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom

Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version”

so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading

later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then,

here we go—

NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits MAD magazine, which, for some inexplicable reason, doubtless Kurtzman-induced, always names itself in capital letters, has been reduced from monthly publication to quarterly. Another sign of the pervasiveness of the Great Recession. Henceforth, we assume MAD will be simply Mad. In passing along this intelligence, Jonathan Bresman, erstwhile senior editor at MAD, announced that March 27 was his last day in that position. The last monthly issue will be the benchmark No. 500, which will appear in April. The Madhouse may be slowly crumbling into the economic miasma, but its editor, John Ficarra, is scarcely wallowing in a slough of despond. Explaining the tectonic shift to George Gene Gustines at the New York Times, Ficarra was nearly jocular in tone (or is that jugular?): “The feedback we’ve gotten from readers is that only every third issue of MAD is funny. So we decided to just publish those.” Typical Madness, in other words. A grace note for the transition. Nicely done. Maggie Thompson, honcho at the Comics Buyer’s Guide (CBG), received from following communique from the financially beleagueredSteve Geppi: "In the past few days, there have been a number of rumors circulating about Gemstone Publishing. As has been the case with many businesses across a wide array of industries, there has been a reduction in staff at Gemstone, and this included the departure of many valued employees. This, however, is not the end of Gemstone Publishing. Our flagship title, The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, remains a vital tool for comic book collectors throughout North America and around the world and it continues to be a highly profitable item for the retailers who carry it. I look forward to making announcements regarding new developments for the Guide’s 40th anniversary next year. At this time, no final decision has been made regarding The EC Archives or our comic books featuring Disney’s standard characters, but it seems certain that both lines will continue in some form. We all anticipate resolving the issues facing us and moving forward, and I will be happy to announce the specifics once things have been finalized." I’m not sure this answers all the questions that recent reports about Geppi’s fiscal plight have raised, but it does seem, in a backhanded sort of way, to confirm reports about Russ Cochran and various Gemstone employees being freshly unemployed. Icv.2 reports that Viz Media, North America’s leading manga publisher, has announced a restructuring plan that includes layoffs. A statement from Viz Media CEO Hidemi Fukuhara: “Viz Media is in the process of refining its focus and is restructuring to adjust to changing industry and financial market realities. Viz feels confident that with these changes, the company will be more streamlined to face the current economic climate.” Then there’s this from Ada Price at Publishers Weekly in mid-February: Despite the economic downturn and increasingly selective buying by consumers, many independent comics retailers around the country are cautiously optimistic after weathering a tough retail period at the end of the year. In an informal phone survey of comics shop retailers across the country (and one general bookstore), some said they had been forced to layoff staff or cutback staff hours in order to survive. Others said they were proceeding with caution, mirroring their customers by being more careful about what they stock. Despite the tough times, the economy seems to affect different parts of the country in different ways, and while some stores report drops in sales since the fall of last year, others claim they remain generally unaffected by the bad economy. More

recently, in May’s CBG,Chuck

Rozanski,

owner of the largest online comic book retail operation extant, Mile

High Comics,

reported that his “overall retail sales” increased 20%

over the last 90 days, but that, he admits, may be because other

comic book retail operations in Denver have failed, sending buyers to

him, and because comic book publishers have raised prices. His online

back-issue sales increased only 3 percent in January, but that’s

because he didn’t invest in inventory; having no great heap of

back issues to sell, he’s pleased he scored even 3 percent

increase. He admits to sending mixed messages with all this reportage

and goes on to warn that an “economic apocalypse” may yet

arrive. On the other hand, he inventively recalls that “the

modern comics industry was born during the Great Depression and

Japanese manga sales were ***** Enough of economic grief. Here’s some good albeit ironic news: Editor & Publisher notes that United Media Syndicate profits jumped 36% in the fourth quarter last year, the same quarter that Scripps, United Media’s parent, offered the Rocky Mountain News for sale, closing it in February 2009 because it couldn’t afford to continue losing money in the newspaper division. United Media’s revenue for the last 2008 quarter increased 20% to $30.9 million, compared with $25.7 million in the year-ago period, Scripps said.“Scripps attributed the United Media profit increase to the decision by the ABC television network to air 13 ‘Peanuts’ specials in the quarter. United Media syndicates Peanuts, Dilbert, Marmaduke and about 150 other comics and features.” You’d think—wouldn’t you?—that an advantage to being part of a huge communications enterprise is that the profitable elements in the operation would support the unprofitable parts, seeing them through such hard times as ours. Not at Scripps. Scripps, which owns 16 newspapers around the country and 10 tv stations, told its legions of employees that they can expect pay cuts soon and a suspension of retirement benefits, reported David Milstead of the Rocky Mountain News, the only Scripps property to escape the cuts (because it died soon after Milstead’s article was published; see Opus 239). Senior managers and corporate executives already took pay cuts of 5-15 percent in January. That’s a switch: in these belt-tightening times, the higher the rank, the less probable a belt. And one more happy economic note: according to the Denver Post’s account, Action Comics No. 1 recently sold for $317,200 in an online auction. The previous owner, who bought it when he was 9 in 1950, paid 35 cents for it. Only 100 copies of this old funnybook are said to exist. ***** Hard Times in the Comics. The spate, lately, of layoffs at newspapers inspired events in at least two comic strips. In the venerable Brenda Starr, the fiesty and glamorous redhead reporter was “furloughed,” said Alan Gardner at his DailyCartoonist.com, quoting Mary Schmich, a columnist at the Chicago Tribune who writes the strip, who told Editor & Publisher: “The budget cuts inside Starr’s fictional newsroom reflect the bottom line at real-life newspapers, which are slashing staffs and freezing salaries in the face of steep declines in advertising and circulation.” She added: "As far-fetched as some of the plots in Brenda are, I do like to keep it topical." She notes Starr's life "is a fantasy with nuggets of reality tossed in. But even fantasies need some grounding in reality, and right now, economic crisis is the reality that colors everything else at pretty much every newspaper." In Doonesbury,Garry Trudeau, likewise inspired by the current blight in newsrooms, arranged for Rick Redfern, his newspaper reporter character, to lose his job at the Washington Post, where he’d worked for 33 years. No one said much when the strip retailed Redfern’s fate in 2008, but when the sequence was recycled this year at the end of February, the Washington Post censored the strip, dropping it on a Wednesday; then, embarrassed by its own gaffe and realizing, as Tim Reid said at timesonline.com, “that it risked looking thin-skinned, the newspaper ran the final three segments and issued an apology. It blamed the initial decision on ‘an internal miscommunication of a sort Rick Redfern would no doubt appreciate.’” Probably, some supersensitive Post editor thought it best not to call attention to the industry’s current predicament, which is manifesting itself in the closing of newspapers, massive chain-wide layoffs, and other manifestations of dire financial ailments. It’s exactly the sort of climate that Dilbert’sScott Adams thrives on, Gardner reported: “In a Q&A with Scott, he is asked why it is easier to write the strip in a bad economy to which, Scott replies: ‘Humor is the flip side of tragedy. So the worse things are, the easier it is to find humor. And I think there is naturally more absurdity. There was a time during the dot-com era that I literally couldn’t get anyone to complain about their jobs. But now, if something is wrong with your life, it’s always someone else’s fault. It’s either the bankers, the politicians or your own managers being greedy and sucking up all the money for their bonus. So you always have someone to blame. And that gives the comic teeth.’” ***** Laurel Maury at npr.org said he walked something like 200 feet into February’s New York Comic-Con without seeing a single comic book. He saw “booths for video games, regular books, Dungeons and Dragons, sure. Toys, everywhere. But this year,” he continued, “the four-year-old NY Comic-Con seemed to be about everything but comic books.” Instead, he saw premiers of tv shows, t-shirts, corsets, vinyl dolls, messenger bags “even doorbells.” Said Maury: “It is increasingly clear that big ‘cons,’ as comic book conventions are called, are no longer the comic book geek's natural habitat—they're places to see and be seen, where Hollywood and the gaming industry try to get products into the hands of early adopters.” The New York Times, which famously doesn't have a comics section, had a booth. "We're here because a lot of people are here," the man behind the table told Maury. Maury

tried to analyze the situation: “Part of the problem is that

kids don't read comics anymore. It takes about 15 minutes to read a

comic book. At $2.95 to $3.95 a pop, that's a pricey quarter-hour for

a 10-year-old who can get his mom to spring for a video game that

will keep him occupied for two months. These days,” he went on,

“kids who read comics tend to buy graphic novel collections,

and the kids reading manga lean toward manga journals like Shojo

Beat. So selling comic books is now about video-game tie-ins, toys and

movies,” Maury concluded: “It's as if, just at the moment

the comic book is gaining appreciation as a real art form, it's

losing its vitality.” ***** It

isn’t often that we get to correct that glorious font of

journalistic accuracy, the New

York Times, so we take an understandable if perverse pleasure in the occasion.

The nation’s newspaper of record announced on Sunday, February

15, that “for the first time in its history, the Louvre is

having a comic strip exhibition. The showing, ‘Small Design:

The Louvre Invites Comics,’ features the words of five

authors,” which are then named—Nicholas de Crecy,

Marc-Antoine Mathieu, Eric Liberge, Hirohiko Araki, and Bernar

Yslaire, all of whom “have used or are using the Louvre as part

of their stories.” But this wasn’t the first time comic

strips have hung on the walls of the world’s mustiest art

museum. The first time may have been in 1967 when the National

Cartoonists Society was invited to assemble materials for a display

tracing the history of the art of the comic strip, and the French

mounted the show in six rooms of the Decorative Arts Gallery of the

museum and issued a 256-page illustrated catalogue. The show’s

main emphasis was on the American comic strip, but examples of

Egyptian and Chinese narrative art were included as well as American

pop artists. Milton

Caniff was

delighted. “It’s great to be hanging up there with Da

Vinci,” he told a reporter in London where he stopped en route

to the Paris exhibition. Later, he described the exhibit: “they

blew up individual panels. Giant size—three by four feet.

Really something.” The exhibit ran from April 7 to June 12 and

featured panel discussions and seminars, screenings of animated

films, and even a fashion show. After closing at the Louvre, the show

moved on to Brussels, Amsterdam, Lausanne, and Rome. All of this

impressive information has been ripped from the pages of an equally

impressive tome, Meanwhile:

A Biography of Milton Caniff, Creator of Terry and the Pirates and

Steve Canyon (my magnum opus, you might say, which is still offered for sale in

this vicinity—just click on the cover displayed at the left on

the opening page of this installment of Rancid Raves; merely $35,

including p&h). ***** Peanuts News. Susanne Cervenka at Florida Today reports that the family of Peanuts creator Charles Schulz donated a 5-foot-tall Snoopy statue to NASA, honoring the space program's 50th anniversary. For 40 years, Snoopy has been the mascot for NASA's Space Flight Awareness Program, an award that recognizes employees' contributions to the space flight success. Less than 1 percent of NASA employees are honored with the "Silver Snoopy," a pin that is flown in space and is awarded by an astronaut. Craig Schulz, the youngest son of the late cartoonist, said his father called the partnership with NASA one of the two most important things in his career. The other was his service in World War II. The 600-pound polyurethane statue depicts Schulz's well-known beagle standing on the moon, donning a spacesuit and holding a helmet. Snoopy is making the rounds of museums and galleries in an exhibit entitled “Snoopy WWI Flying Ace.” Despite occasional claims in promotions, no original art is on the wall: all the strips are “digitally reproduced from original art.” Copies, in other words. Snoopy first took to the skies in his sopwith camel on October 10, 1965 (it sez here on the wall plaque) and subsequently appeared in 400 strips over 34 years, the last published on November 28, 1999. Although some readers saw an allusion to Vietnam in the Flying Ace strips, Schulz didn’t. At first. Later, though, when he saw the possible connection, he stopped sending Snoopy into the blue for a while. “We were suddenly realizing that this was such a monstrous war,” Schulz said once, “—it didn’t seem funny. So I stopped doing it.” Snoopy took flight again some years later, but not into combat. “I didn’t do him fighting the Red Baron,” Schulz said. “Mostly, it was sitting in a French café flirting with the waitress.” The

latest Peanuts reprint from Fantagraphics takes the strip through 1972 (325

6.5x8-inch pages, b/w; hardcover, $28.99), the 11th volume, now at the brink of the half-way point in the publication

project. This volume’s Foreword is a short interview with

Kristin Chenoweth, the “pint-sized” actress who won a

Tony playing Charlie Brown’s sister Sally in the 1998-99

revival of the musical “You’re a Good Man, Charlie

Brown.” She never met Schulz, but he sent her flowers when she

won the Tony “and told me I was born to play Sally.” The

only other comics character she aspires to play is Betty Boop. In

this volume, Snoopy maintains his membership in the Beagle Book Club

and betrays an admiration for Helen Sweetstory’s series of

books about the six Bunny-Wunnies, and he assumes various “Joe”

identities—Joe Cool, Joe Eskimo, Joe Family, Joe French, Joe

Rock, the “world famous swimmer” who, immediately upon

contact with the water, sinks. Like a rock. ***** Dave Astor, who, you’ll doubtless recall, was laid off at Editor & Publisher after a professional lifetime of writing and editing for journalism’s trade magazine, went home and started polishing an idea for a syndicated humor column like the one he’d been doing for the local paper for some years. He hasn’t found a syndicate deal yet, but his column now appears at HuffingtonPost.com; search under “Dave Astor.” Here’s an excerpt from a recent one (in italics): So when an underpaid cashier looks up from my credit card and asks if I'm one of those Astors, I can honestly say no. I'm not a loathsome, materialistic hedge-fund bozo who tells his mistress "we'll always have Paris" as the bozo's financial victims say of him that "we'll always have parasite." I drive a five-year-old compact car, trim my weed-filled lawn with a manual push mower, and watch a small TV that has an antenna. (Yes, I'll switch my set from analog to dialog when I poke the corner of a $40 plastic converter coupon into my remote's stuck mute button.) Maybe I should have taken my wife's last name when we married. She has a very nice last name (Cummins) that doesn't sound elitist -- though she and many of her family members are accomplished people. Actually, I did try to take her seven-letter last name, but it had dwindled to two letters after a bank bundled it with other last names and invested them in tricycles retrofitted with jet engines. (Corporations endanger our children's future in so many ways....) The bank got a $15-billion bailout last Christmas, but spent the federal money on three $5-billion fruitcakes. I do go by "Dave" rather than "David" to slightly soften the aristocratic sound of my last name. But that's like being locked in a bank vault and trying to escape with a chisel made of cotton. Remember the Titanicscene in which "Unsinkable" Molly Brown shouted "Hey, Astor!" to that John Jacob fellow? When I heard that back in 1997, I sank embarrassedly into my movie-theater seat. Twelve years later, I cringe even more at the recollection of actress Kathy Bates calling out such a highfalutin name. That's because the rotten economy has left me with less money to compensate for having a Gilded Age second name as the second Gilded Age ends. End of excerpt. Dave, who covered syndicated comics and cartoonists with compassion and insight, did some cartooning on his own not so long ago; here’s a sample: ***** Paul Clark at the Cincinnati Enquirer tells the tale of Ziggy cartoonist Tom Wilson II’s nearly incapacitating depression better than I can; here’s Clark (verbatim, almost; in italic): Tom Wilson understands better than anyone that Ziggy’s phenomenal appeal lies in an indomitable optimism and unshakable daily resilience. For Wilson himself, it hasn't always been so. Wilson, 51, fought severe depression after a series of debilitating sorrows in his personal life. A car accident crushed his leg during a business trip in the early '90s. Illnesses including lung cancer struck his father, Tom Sr., who created Ziggy 40 years ago and from whom Wilson inherited the cartoon franchise in 1987. Most horrifying of all: Wilson's wife, Susan, his soulmate since they met as young art students at Miami University, died of breast cancer in 2000 at age 44. "I was a mess," Wilson recalls. "I was married 23 years. Susan was the love of my life. I had two young boys. I couldn't commit suicide. I couldn't go the denial route." In what seemed a cruel irony at the time, Wilson struggled against demonic despair even as he labored to bring forth daily smiles with the epigrammatic Ziggy, the cheeriest character in the comics world. Then a wonder emerged. Wilson found himself increasingly identifying with Ziggy. The daily work of renewing Ziggy's optimism helped Wilson do so for himself. Wilson tells his inspirational story in a newly released autobiography, Zig-zagging, A Memoir: Loving Madly, Losing Badly—How Ziggy Saved My Life. Much of the book derives from journals Wilson kept along the way, a practice he found therapeutic. Some were recorded on audiotape during his regular travels up Interstate 71 between his home in Loveland and his business in Cleveland, a cartoon-character licensing and branding company called Character Matters. "The book is raw and unedited," Wilson says. "All of the passion is there from journaling, putting things down raw. I'm not acting like I'm an expert, like I'm smart, like I have a Ph.D. At times I thought 'If it's unedited, people are going to say you're nuts.' But I wasn't myself then, it was depression." Wilson said his father is "doing well," now in his early 70s and living in Montgomery. Wilson's son Miles is a marketing student at the University of Cincinnati; younger son Sam is a student at Cincinnati Country Day School. Ziggy, of course, continues to prosper, appearing daily in more than 600 newspapers and still a fixture on coffee mugs, calendars and refrigerator magnets. "I'll keep on

drawing Ziggy as long as I can and as long people want to see him,"

Wilson says. "What I came to realize with Ziggy was that I

became the character in the panel in a way. It got me in touch with

my inner child and I realized my inner child's name is Ziggy." ***** Give to the Checkered Demon. As frequenters of this intersection on the Information Superhighway know, S. Clay Wilson, creator of some of the most unsavory comics characters ever to be beloved by fans, has been in the hospital for months lately, trying to recover from having fallen on his head while staggering home drunk one night last November. His medical bills are too much for him to pay single-handedly even with his medical insurance, and some of his friends, led by cartoonist David Chelsea, have determined to raise funds to help dig Wilson and his family out of the resultant penury. Says Chelsea: “S. Clay Wilson is a major figure in American comics, a founder of the underground comix movement. Wilson is known for aggressively violent and sexually explicit panoramas of lowlife, often depicting the wild escapades of pirates and bikers. He was an early contributor to Zap Comix, and Wilson's artistic audacity has been cited by R. Crumb as a liberating source of inspiration for Crumb's own work, and I can say as much for myself. I’d like to give a little back to the bad boy of comics, so I am turning my next 24-hour comic into a benefit for Wilson. For those of you who may not have heard of it, the premise of the 24-Hour Comic Challenge is that an artist attempts to complete 24 pages of comics within 24 hours. I am soliciting pledges from friends and comics fans for each page I complete, the money to go towards Wilson’s medical expenses. Contributions are at levels named for S. Clay Wilson characters: Checkered Demon- $25 a page and over; Star-eyed Stella- $10 - $24.99 a page; Ruby the Dyke- $5- $9.99 a page; Captain Pissgums - Under $5 a page.” Contributions

are not tax deductible, Chelsea says, but contributors will receive

an autographed copy of his completed story. The 24 Hour Comic Event

will taken place at Cosmic Monkey in Portland, Oregon, on Saturday,

April 11th from 10 am to 10 am the next day, which is Easter Sunday.

Information about it can be found at cosmicmonkeycomics.com. Other

artists joining Chelsea in soliciting pledges for their own 24 Hour

Comics are: Joshua

Kemble, Kevin Cross, Neal Skorpen, Mike Getsiv, Tony Morgan, Josh

Fitz and Steven

Abrams. Anyone interested in pledging can reply by e-mail: davidchelsea@comcast.net or write to: David Chelsea, 2814 NE 16th Avenue, Portland OR 97212.

Chelsea concludes: “I will contact all sponsors after the event

to let them know how many pages I completed and to send them their

copies.” Checks can be written to the S. Clay Wilson Special

Needs Trust and sent to PO Box 14854 San Francisco CA 94114. More

about all this can be found at sclaywilsontrust.com, the webpage

developed by the cartoonist’s long-time partner, Lorraine

Chamberlain, who says making the webpage was “a daunting task,

as well as subject, it being my first time,” adding: “He’s

doing well, and I hope to bring him home from the hospital soon”

(written March 29). ***** The New Yorker’s cartoon editor, Robert Mankoff, believes that 98 percent of the magazine's readers look at the cartoons first—“and the other 2 percent lie,” writes Joseph P. Kahn at the Boston Globe. Mankoff also runs the magazine's Cartoon Bank, wrote The Naked Cartoonist: A New Way to Enhance Your Creativity, and created the magazine's caption contest, a feature that draws thousands of submissions each week. Kahn asked Mankoff if he personally wades through the caption contest entries. Not exactly, said Mankoff: “A computer program sorts them out, then my assistant gives me 50 or 60, broken into categories. For example, we ran a cartoon of a car that had crashed into a room where two people are in bed. Categories might include Bad Sex and Kid Coming Home. I'll pick three entries and send them to [editor] David Remnick for approval. I try to pick from different ones, like, ‘I thought our sex life was a train wreck, not a car accident.’ And, ‘Well, at least he made curfew.’ But it's very subjective.” New Yorker cartoons are highly topical, Mankoff said, reflective of the times, which precipitated this exchange between him and Kahn: Kahn: What about poking fun at, say, economic Armageddon? Mankoff: Well, we have a cartoon anthology coming out, On the Money, that looks at issues like the stock market and personal finance since 1925, year by year. Kahn: If anyone has any money left, it should sell like hotcakes. Mankoff: Yes, although the hotcakes industry is going down the tubes, too. The United States now outsources all its hotcakes. Footnit: New Yorker editor David Remnick scoffed at rumors that the magazine is considering cutting back on its publication schedule due to financial trauma. In recent years, The New Yorker’s bottom line has been considerably enhanced by sales from the Cartoon Bank, which, when Mankoff, who invented it, first offered to sell to the magazine, it declined. Later, it thought better of that decision and reversed it. ***** On April 6, Scott Hilburn's daily panel cartoon, The Argyle Sweater, celebrated its first anniversary with Universal Press Syndicate (UPS). The cartoon first appeared in December 2006 at the UPS-sponsored website for unpublished cartoonists, Comics Sherpa, and then at GoComics, another UPS-inspired website (where fragments of Rancid Raves also appear some weeks after debuting here). Often compared to Gary Larson’s Far Side, Argyle Sweater is now published by more than 200 newspapers across the United States saith a news release from the syndicate. A situational cartoon involving dogs, cats, cops, bees, wolves, game shows, bears, telephones, sports, zebras, nursery-rhyme icons and cavemen not to mention the occasional evil scientist, The Argyle Sweater: A Cartoon Collection, Hilburn's first compilation, was released last month by Andrews McMeel Publishing, another of the many UPS entities. Editoonist Brian Duffy, who, after 25 years at the Des Moines Register, was unceremoniously dumped by the paper in December 2008, might lose more than his job: the Register has refused to let him have the original art for his cartoons. The paper wants to donate them to the University of Iowa, which, according to a report at kcci.com, plans to preserve more than 100 years of editorial cartoons in the state of Iowa. The irony isn’t lost on Duffy: "The editor felt that I wasn't important enough, or my work wasn't important enough, to keep me at the newspaper, yet she wants to keep my legacy alive by donating all of my work to the University of Iowa.” Duffy, while maintaining that a cartoonist’s work has historically been regarded as the cartoonist’s property, cites a legal-sounding precedent in his case: a book of his cartoons published by the newspaper carries the notice “copyright Brian Duffy and the Des Moines Register, not just the Des Moines Register," said Duffy. "I have no problem donating a large body of work to the University of Iowa. In fact, I'd love to do that." But he wants to do it on his terms not on behalf of the newspaper that shooed him out the door. A new postage stamp to be unveiled April 9 features Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa and Maggie from “The Simpsons.” Designed by Simpsons creator, Matt Groening, the new stamp helps celebrate “the longest running primetime comedy’s 20th anniversary year this year” reports Georg Szalai at hollywoodreporter.com. ... One of the broadcast medium’s most venerable soap operas, “Guiding Light,” which began as a 15-minute serial on NBC Radio on January 25, 1937, moving to CBS tv in 1952, will end September 18, saith the Associated Press. ... When “ER” ended April 2, 1,250 trauma-patients had been treated in the fictitious County General in Chicago. The tv production used 180 gallons of fake blood, reported the Minneapolis Star Tribune. ... Dave Itzkoff at nytimes.com reports that Robert Crumb has completed his graphic novel adaptation of the first book in the Bible. Called Robert Crumb’s Book of Genesis, it was four years in the making. Scheduled for release October 19, the volume is “very visual,” said Crumb in The Guardian: “It's lurid. Full of all kinds of crazy, weird things that will really surprise people." Alan

Moore’s books, Watchmen chief

among them, dominated the New York Times Graphic Books Best Seller

List on March 14—Watchmen in first place, The

Killing Joke in third among hardcover books; in paperbacks, Watchmen in first again, V

for Vendetta in fourth. Fantagraphics came in a close second: its fabulous reprint

of Harvey

Kurtzman’s satirical magazine, Humbug, ranked sixth in hardcover, and the 11th volume of the Fantagraphics Peanuts reprint series, 1971-72, stood at tenth. ***** Under the heading “At Home with the Joker,” the AARP Magazine for March-April ran a full-page article about Jerry Robinson, explaining how he invented the Joker and Batman’s juvenile sidekick, Robin, and going on to report that Robinson, at 87, is “going strong as an artist, writer, curator of exhibitions, and head of a syndicate, Cartoonists & Writers Syndicate/CartoonArts International, distributing more than 350 cartoonists.” Robinson has two books coming soon from Dark Horse: a revision of his 1974 history, The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art, and a compilation of the sf comic strip, Jett Scott (starting September 28, 1953; ending in 1955), that Robinson drew over Sheldon Stark’s scripts. Said Robinson: “To live, I have to create. I have to be involved.” He’s also writing a graphic novel for DC Comics about “an older Clown Price of Crime, who ‘has changed, as any person would,’ says Robinson, laughing, ‘and not necessarily for the better.’ ... when people read about heroes who conquer adversity—crime and evil and, from time to time, the Joker—it gives them some hope for the future,” he concluded. The article is illustrated with mug shots of the Joker (as inspired by Conrad Veidt in “The Man Who Laughs,” Cesar Romero in the 1960s camp tv series, Jack Nicholson in the first Batman movie, and Heath Ledger in the latest) and a photograph of Robinson sharing a coffee break with the grinning gargoyle, which picture we reproduce forthwith. Of the Top Twenty Heroes listed in Entertainment Weekly’s April 3 issue, 3 were comic book characters: Superman (in third place), Spider-Man (10th) and Batman (18th). Those were editors’ picks. Readers listed Superman and Batman (nos. 1 and 2) in the Top Ten. The same issue also mustered the Top Twenty Villains, and of those, again, three were comics characters: the Joker (4th), Mr. Burns of “The Simpsons” (6th) and Snow White’s Queen (15th); readers, on the other hand, listed the Joker first, then Lex Luthor in 8th position in the Top Ten. At last report (thanques, John), Sean Delonas is still drawing editorial cartoons at the New York Post so we may conclude that the Sharpton Faction has not, yet, forced Rupert Murdoch to fire his vitriolic penman. ... The latest Previews catalog offers a “Chocolate Booty Babe Vinyl Figure,” an African American femme, the booty of whom is ample in every department. ... The artistic styling of Mike Kunkel’s Captain Marvel ensemble reminds me of Hoppy the Marvel Bunny, another Fawcett creation of the 1940s. ... Marvel comic books have gorgeous covers. ... Following Fantagraphics’ reprinting of all of Harvey Kurtzman’s Humbug magazine, the premiere Kurtzman satire, here comes Dark Horse with a reprinting of the “complete” Trump magazine, Kurtzman’s aborted effort for Playboy that preceded Humbug: a gorgeous magazine production (compared to the shoe-string operation at Humbug), it ran only two issues, so “complete” is much shorter than Humbug’s 11 issues. ... My son, the great radio legend Paul Harvey, died February 28 at the age of 90. His voice resonated on the airwaves since 1951, a monumental achievement. His son quoted his father in his eulogy: “A great tree has fallen. An empty place has opened against the sky.” It was what Paul Harvey said at the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945. ... At newsarama.com, Michael Doan reports that Rob Liefeld's Image Comics series Youngblood has been optioned for a movie by Brett Ratner and the Indian production company Reliance Big Entertainment with a 1012 release date in mind. Ratner will direct. Down

Under, David

Rowe, whose

forte is topical comedy—caricatures and political cartoons—won

the Stanley, the Australian “cartoonist of the year”

trophy from the Australian Cartoonists Association, during the

group’s annual get-together last November. The USA’s Jim

Borgman,

retired editoonist and still the rendering half of Zits,

which he produces with Jerry

Scott, was a “Monsters vs. Aliens,” the harbringer of the forthcoming flood of 3-D animations this spring, ranked first in box office receipts, $58.2 million, on its opening weekend, compared to “Watchmen’s” mediocre opening at $55 million. According to the Associated Press, “the 2,080 3-D screens accounted for just 28 percent of the roughly 7,300 screens on which the movie played, but they made up 56 percent of its total box-office haul,” quoting DreamWorks Animation. DreamWorks honcho, Jeffrey Katzenberg, believes the future is in 3-D—in fact, the salvation of animated films if not motion pictures in general. And he’s putting his money where his belief resides: all of DreamWorks future animated films will be shot in 3-D—even Steven Spielberg is joining the club, shooting a 3-D version of his Tintin movie—and the race is on to provide movie theaters with 3-D capabilities at a cost of $25,000/screen. Katzenberg, quoted in Entertainment Weekly (March 27), said: “In order to bring people back to the movie theaters, we’ve got to do something exceptional—we have to raise the bar,” extolling the strategy behind the 3-D surge. According

to the “People in the News” department of the online

feature InfoPlease, “In May 1922, Rudolph

Dirks,

creator of the comic strip The

Captain and the Kids (once, before World War I made anything Germanic verboten, called The

Katzenjammer Kids) was replaced as cartoonist for the strip by a young understudy, Bernard

Dibble,

after United Feature Syndicate acquired the syndicate contracts of

the New

York World.” You can also find Comics Timeline in the vicinity; it lays out the

history of comics, year by year. This chronological history contains

at least one possible error, however: The

Katzenjammer Kids may not, at first, have been about two mischievous boys; it may have

been about three mischievous boys. You can see an acceptable but not

very clear reproduction of the very first Katzies strip, December 12, 1897, at

geocities.com/~jimlowe/katzies/1897.html, and it’s obvious that

the kids number three, not two. “Only two remain from the

second episode forward,” curator Jim

Lowe says,

but he adds that he isn’t sold on the trio notion: “To

me, however, it is just as likely that the third ‘kid’ is

a playmate” not the third Katzie. Take a look and decide for

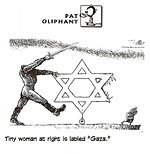

yourself. ***** Here’s

the Pat

Oliphant March 25 cartoon that the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) calls

"hideously anti-Semitic" because of its use of Nazi-like

imagery and evocation of the Jewish Star of David. We don’t want to support anti-Semitism here at Rancid Raves, but this cartoon, an obvious comment on Israel’s invasion of Gaza (represented by the tiny female figure at the lower right), is in the usual Oliphant no-holds-barred mode. An equal-opportunity offender, the cartoonist has also castigated the Catholic church by depicting priests as ravening pedophiles. Naturally, the Catholic church was offended, but that does not mean Oliphant should stop drawing cartoons that are sufficiently offensive to inspire discussion and, even—perhaps—thought. The Gaza-invasion cartoon is clearly in the same league as the pedophile cartoon. Whether Israel was justified in its assault on Gaza is not the issue in the cartoon, which, like all editoons, can memorably depict only one side of a controversy at a time. The purpose is not to explain or to weigh pros and cons: the purpose is to provoke viewers into pondering an issue. That Foxman objects to the cartoon is not surprising: he has been known to imply strenuously that any criticism of Israel is essentially anti-Semitic. That may be true some of the time, but to invoke the spectre of anti-Semitism any time Israeli policies are criticized is to shut down all thoughtful consideration of the issues. Not a good idea. Often when the ADL launches one of its tirades, various elements of the populace start muttering about that supposedly sinister force, “the Israel lobby,” or “the Jewish lobby.” This issue came up again recently when President Obama’s poorly vetted choice to head the National Intelligence Council, Charles Freeman, withdrew from consideration, saying that he had been destroyed by the Israel lobby because he believes the chief obstacle to peace in the Middle East is “Israeli violence against Palestinians,” as reported in The Week for March 27. The magazine goes on to paraphrase and quote Andrew Sullivan’s piece at TheAtlantic.com: The charge by Freeman and his defenders of a “conspiracy” involving supporters of Israel is simply absurd as is any implication that the pro-Israel lobby is somehow “more nefarious than, say, the Cuba lobby, or many other lobbies.” At the same time, the notion that anyone who expresses sympathy for Palestinians or who wants a more evenhanded Mideast policy is anti-Semitic or “hostile to Israel” strikes me as equally wrongheaded. “The two paranoid generalizations, of course, feed on each other. That cycle needs to be broken. There is too much at stake for this debate to be about us.” Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment (and some of the material in the ensuing paragraphs) is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

THE P-I TAKES THE PLUNGE: PRINT VERSION CRASHES But Its Pulitzer-winning Editoonist Survives Hearst’s Seattle Post-Intelligencer, one of the nation’s oldest continuously published newspapers, issued its last print edition on March 17 and and began focusing its new, low-budget resources on a website version, taking only about 20 of the paper’s 175 staffers with it. David Horsey, the P-I’s two-time Pulitzer-winning editorial cartoonist is not one of the lucky twenty. His is a different kind of luck: Horsey is employed by Hearst, not the P-I, and his cartoons will continue to appear online as a service to the 15 other newspapers in the chain. Seattle is the second major American city this year to lose one of its two daily newspapers: Denver lost the Scripps-owned Rocky Mountain News last month just 55 days sort of the paper’s 150th birthday (see Opus 239). While the News may have considered continuing as a digital paper, it ultimately gave up any such notion. But not its staff: about 30 crazed Rocky staffers have announced their intention to continue the feisty journalism of the Rocky online if they can get 50,000 of the paper’s passionately loyal readers to pay a subscription fee, making a commitment by April 23 (the Rocky’s 150th anniversary date). The next major daily newspaper to go under is likely to be another Hearst paper, the San Francisco Chronicle, which Hearst has vowed to shutter if its costs can’t be drastically reduced. If the Chronicle goes, San Francisco will become the first American metropolitan area to be without a daily newspaper. The San Francisco Examiner on which young W.R. Hearst cut his journalistic teeth in the late 1890s still exists, but it is no longer a Hearst property; Hearst’s descendants sold it in order to avoid anti-trust regulations when they acquired the Chronicle, but the storied Examiner is now a free tabloid published just five days a week, a shabby remnant of itself, scarcely the sort of paper a big city deserves. Mike Simonton, a senior director at Fitch Ratings which analyzes the industry, told Richard Perez-Pena at the New York Times that “in 2009 and 2010, all the two-newspaper markets [in the U.S.] will become one-newspaper markets, and you will start to see one-newspaper markets become no-newspaper markets.” The next two-paper city to become a one-paper town is likely to be Tucson where the Gannett-owned Citizen is expected to fold momentarily. On March 9, Douglas A. McIntyre at Time.com reported that 24/7 Wall Street had created a list of ten additional major dailies, including the San Francisco Chronicle, that are likely to shut down within months due to soaring costs and evaporating revenues. Six are the weaker of two newspapers in town. The Philadelphia News, the smaller of the two papers owned by Philadelphia News LLC, will likely leave the market to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the other paper owned by PN. The Minneapolis Start Tribune, which has filed for Chapter 11, may become a digital publication “as supporting a daily circulation of more than 300,000 is too much of a burden” (an interesting observation; see below); the St. Paul Pioneer Press will survive. Gannett’s Free Press in Detroit will probably survive; the Detroit News will die off, despite the recent financial adjustments made by both papers to discontinue home delivery four days a week. In Chicago, the Sun-Times, founded in the early 1940s by millionaire playboy Marshall Field II to provide a truth-telling alternative to the Chicago Tribune, is likely on its last legs. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram will succumb soon, leaving the market to the Dallas Morning News (or becoming the Fort Worth edition of the News). And the Cleveland Plain Dealer will leave its market without a major daily by the end of the year. In addition, the Boston Globe, owned by the financially strapped New York Times, will probably go digital by the end of the year, and the New York Daily News, America’s first successful tabloid newspaper, will probably exhaust its billionaire owner’s ability to support its loses, leaving the city to the Times, the Post, Newsday and, perhaps, if Advance Publications doesn’t fold the paper, Newark’s Star-Ledger. Finally, the Miami Herald, suffering a tremendous loss of revenue due to the decline in real estate advertising, will probably retreat to the electronic ether with two editions, one for English-language and in Spanish, leaving the city without a print newspaper. At the risk of displaying my prevailing cynicism, I can’t help but notice the number of these doomed newspapers that are links in various chains. It would seem (no surprise) that corporations that own chains of newspapers are not much interested in journalism: their over-riding concern is with the publications as “profit centers,” and when a paper ceases to produce a profit, the corporation is fairly prompt these days in shutting it down. Or so it seems. Despite all the bad news, Editor & Publisher, the industry’s trade journal (which has also suffered in the current economic climate, cutting back staff and going from weekly print publication to monthly, supplemented by “breaking news” reportage online), doesn’t think print journalism is finished. The editorial in the current issue (March) sees the financial woes of newspapers as essentially “self-inflicted wounds” rather than fundamental problems with the medium. “Bankruptcy filings ... are being seen as signs of the Apocalypse, but the newspaper industry needs to get a grip. One factor unites all these mendicants—crushing debt, taken on for ventures that now appear as ill-considered as doubling-down on subprime mortgage securitization.” In Denver, for instance, the Denver News Agency, which handled the business side of the Denver Post and Rocky Mountain News operations, invested millions in modernizing a printing plant. That may have made a kind of sense: better production seemed likely to provide a way of competing with the Web. But it left the company with a debt that the revenues from operations could not handily make payments on. Ditto in numerous other newspaper venues where newspapers made the present hostage to the future. Disappearing newspapers often means disappearing editorial cartoonists. The staff positions of 7 editoonists are threatened by the looming collapse of the papers listed above: Signe Wilkinson, a Pulitzer-winner at the Philadelphia News; Steve Sack in Minneapolis; Mike Thompson in Detroit; Jack Higgins at the Sun-Times in Chicago; Jeff Darcy in Cleveland; Dan Wasserman at the Boston Globe; Jim Morin in Miami. The collapse of newspapers in big cities also bodes ill for syndicated comics: the greater circulations of metropolitan dailies translate into higher fees for syndicated material, and with the collapse of a major daily newspaper carrying comic strips (and all these do except the New York Times), the incomes of syndicated cartoonists carried in those newspapers drops. Not disastrously—like the loss of employment—but significantly. End of the P-I The end of the print edition of the Post-Intelligencer does not, according to publisher Roger Olglesby, signal “the end of the bloodline” which began August 15, 1863, when an itinerant printer, James R. Watson, published the first issue of his weekly Seattle Gazette on a hand-cranked wooden press he brought with him from Olympia. Seattle at the time was a frontier town of only a few hundred souls, mostly lumberjacks who made a living chopping down tress on the hillsides overlooking Elliot Bay and then sliding the logs down the slope to the water’s edge, creating the street known there and elsewhere as “skid row.” Watson sold his paper to Samuel Maxwell, who renamed it the Weekly Intelligencer because, according to legend, his limited stock of type didn’t include enough of the letter Z (or some such mythology). The paper went daily in 1876 and five years later bought the Seattle Post, becoming the P-I. Online the P-I will continue as what they’re calling a “community platform” that will feature breaking news (mostly local but also taken off national wire services), columns by prominent Seattle residents, community databases, photo galleries, 150 citizen bloggers (who have already debuted over the past months on the P-I’s website), and links to other journalistic outlets. “Our strategy moving forward is to experiment a lot and fail fast,” said executive producer Michelle Nicolosi. “That’s how we’ve been operating the website for years, and it’s been a very effective formula for growth.” But with all those “citizen bloggers,” how professionally will the news be conveyed? “We don’t have reporters, editors or producers,” Nicolosi said, “—everyone will do and be everything ... write, edit, take photos and shoot video, produce multimedia and curate the home page.” She says they’ll focus “on what readers are telling us they want ... We know what we do best, and we are going to build on the things that we know our readers love and look to find new ways to inform and entertain them.” The online enterprise will also have Dave Horsey, Nicolosi made a point of saying, “—our two-time Pulitzer winning cartoonist who will continue to create his brilliant cartoons and blog for us at DavidHorsey.com,” that being Horsey’s Hearst URL. Horsey

Rides On “I'm in an unusual situation, unlike Ed Stein, whose job ended [when Denver's Rocky Mountain News closed],” Horsey told Mike Cavna at the latter’s Washington Post blog, ComicRiffs. “For the last few years, I've been employed directly by Hearst Newspapers instead of the Seattle P-I. It looks like I will be providing my work to all of the Hearst newspapers, though I'll be based here at the [P-I] Web site. Hearst has 15 daily newspapers [at present, counting the San Francisco Chronicle]. My work will primarily go to Web sites and will be available for print versions. ... One fortunate thing for me is that Hearst had this idea to create channels within the Web site, and that pulled me out of the editorial page and created DavidHorsey.com. And I've been doing a lot more writing as well as cartoons. That created me as a separate entity that can be plugged into any Web site. I'm not sure logistically how that will happen now—I think I'll be linked to [the Hearst newspapers in] Houston, Albany, Laredo, San Francisco. I think Hearst finally decided that it's time to [push] online newspapers. ... I've been quite fortunate and the timing has been right. Part of it goes back to my first job as a reporter— now it's the other way around. [Writing columns] has helped me expand online. They're looking at me as a ‘multimedia commentator’ rather than as ‘just’ a cartoonist.” Horsey has been at the Post-Intelligencer almost since he graduated from the University of Washington in Seattle. “I feel like I've been very lucky,” Horsey said. “I didn't plan to be a cartoonist, and ... neither the [Seattle] Times [the other paper in town] nor the P-I had had an editorial cartoonist for decades. I graduated in journalism and went to work for a new suburban daily [Bellevue Journal-American] ... where I was doing a weekly column and illustrating it with cartoons. I ended up getting that syndicated around the state. Then through great chance—or the greater purpose of the universe—the man who was my professional adviser for my student newspaper ... became managing editor [of the P-I] and he didn't know anybody else in cartooning. Looking back, I realize how incredibly lucky I was. The Times had Brian Basset, and Mike Luckovich was at the University [of Washington] just a couple of years after I was [and couldn't get hired in the area]. It wasn't till later I realized that it all worked out pretty well for me. “The other plus,” he continued, “was because I ended up being at the right paper. All my editors have been supportive. The Seattle Times has gone through three cartoonists [Basset, Chris Britt and Eric Devericks] in the time I've been here. I always figured that I was one new editor away from unemployment. Clay Bennett is a great example [of a talented cartoonist who was ousted]. KAL [Kevin Kallaugher] in Baltimore [at the Sun] is another prime example of that. I had that sense that things can go askew at any time. I've been attuned to the politics of the paper, and Hearst in general. I decided I needed to get to know the president of Hearst Newspapers. It helps. Two Pulitzers also helps. I recommend that to anyone.” When Cavna supposed that concentrating on local politics and community issues works as a strategy to stay on staff, Horsey disagreed. “Look at Lee Judge [who was laid off in 2008 by the Kansas City Star]. He was the ultimate local cartoonist and he's out of a job. I'm skeptical of the ‘go local’ approach to cartooning to preserve your job. The biggest response I got [last year] was to Obama and McCain cartoons. ... [Local cartoons] are worth doing, but not because it'll save a job. Ultimately, if they want to fire you, they will. It's the economic reality.” He feels Hearst handled the P-I situation as well as could be expected: “I don't know how you can handle laying off people and closing a paper well. By definition, it's a cruel thing. ... But they've been very straight. They've handled it in a very businesslike way. It's an understandable step. Invariably, it messes up a lot of people's lives.” Later, he added at an online List: “Calling what¹s happening to newspapers a ‘downsizing’ is like calling amputation a diet plan.” And the fate of his cartooning brethren is similarly disturbing: “The non-stop bad news about our cartooning colleagues is like being slapped in the back of the head by a baseball bat every time I open an e-mail.” Five blows from the bat landed in March: Bill Garner, Robert Ariail, Bill Day, Gary Brookins, and Tom Myer; see below, where the demolition of the profession continues, unabated. Saying

Farewell to the P-I The

print P-I is ending, but the world still turns—the “world,”

in this case, being the 18.5-ton, 30-foot neon globe atop the P-I

building on Elliott Avenue overlooking the bay. An icon for the paper

and a landmark for the city, the globe, straight out of the Daily

Planet in Superman comics, was designed by a Washington University

art student in 1948, the result of a contest the P-I conducted, asking readers to suggest a symbol for the paper. The

globe revolves, repeatedly displaying the motto emblazoned around its

equator in red letters five feet high—“It’s in the

P-I”—floating against the glowing green continents and

blue oceans, capped by a majestic eagle, its wings raised as if about

to take flight. A color photograph of the icon filled the front page

of the paper’s last print edition with the caption: “You’ve

meant the world to us.” Inside, in Horsey’s fanciful

cartoon for last P-I in print, the eagle has left its perch. Editorial cartoonist Steve Greenberg, who spent fourteen years at the P-I, doesn’t have high hopes for the paper’s digital fate. “I have seen the future of newspapers,” he said, “and it is to be understaffed, with diminishing salaries, financially iffy, and hoping that a hoard of ‘citizen journalists’ can make up for the lack of truly professional ones. Hard (and expensive) investigative reporting will yield to the endless chatter of opinionated blogging, and elected public officials will merely be annoyed instead of truly being held to the fire. Ultimately, the public will be the loser. And the Seattle public might not even have the Seattle Times, which is bleeding money, scarcely hanging on itself and might not even survive despite being handed a monopoly in town.” The P-I was Greenberg’s second newspaper. He came to Seattle from the Los Angeles Daily News in August 1985 to sit in for Horsey, who was going to England on sabbatical for a year. Writing in his blog at blog.cagle.com, Greenberg recalled his time at the P-I: “The Seattle Times was richer, more elite, centrist-to-conservative, and smugly superior, selling far better in the well-to-do suburbs. The P-I was looser, more liberal, more blue collar, less-esteemed but generally a match for the Times in quality, and had the feel of being the more historic ‘voice of the Northwest.’ It was also a great place to be an editorial cartoonist, but vastly more so if your name was ‘David Horsey.’ Long before he won the first of his two Pulitzers, he was a local-boy-made-good, held in more esteem by the local population than virtually any other editorial cartoonist working, with perhaps the exception of Mike Luckovich (or, in an earlier generation, Hugh Haynie). He’d made his reputation at the University of Washington Daily, where his strong draftsmanship and frequent inclusion of sexy babes in his drawings won him a following that never left him. At the P-I, he was treated as one of their top few superstars, and was wooed by rival newspapers trying to lure him away. “I arrived blissfully unaware of his local stature,” Greenberg continued. “I had a pretty good year, and started to make my own name in town—until he returned to reclaim his spotlight. I remained as a combination staff artist and secondary cartoonist—mostly to learn the more-employable graphics skills, and because of relationships—and did many of the best cartoons of my career, but from a point of remarkable relative obscurity from that point on.” When I met Steve, interviewing him in 1998 for the fabled Cartoonist PROfiles, he and Horsey worked at opposite ends of the same room, the “art department.” Horsey, whom I also interviewed then, had not yet won his first Pulitzer; he seemed the younger of the two, a cheerful strawberry blonde with matching beard, his eyes always a-twinkle, the smile on his face often broadening to a wide grin. He seemed carefree and eager then—and every time I’ve seen him since. Steve, with thick dark curly hair and beard and sleepy eyes that seemed guarded and thoughtful, appeared the more serious cartoonist, somber and pensive. I didn’t know, then, that Horsey was the paper’s fair-haired boy, but I remember his work station was next to a window, and Steve worked in a corner away from the daylight. I sensed no particular rivalry between the two while I was there, and it doubtless existed in some fashion. Greenberg, writing about his time at the P-I, conveys some inkling of it but without a single blot of animosity: “It was difficult working in the shadow of a coworker clearly favored by the management (and there were many components to that),” Greenberg said. “But at the same time, it was exciting working for a pretty good, scrappy, feisty metro newspaper, and I was given excellent editorial freedom in my cartooning—perhaps an advantage of being somewhat invisible to the editors hurriedly green-lighting my sketches as they pressed me not to take up any more of their precious time. I made a decent salary (thank you, Newspaper Guild), won several awards, and got to live in a beautiful, colorful, literate city, even if it rained half the days of the year and was overcast most of the rest. My situation was fairly secure (thank you again, Newspaper Guild) although I’m sure they would’ve preferred not having a second cartoonist, and I hung on for years for lack of another staff cartooning job to jump to, until I finally left for my native California in early 2000. “But the awkwardness of my personal status there doesn’t diminish my appreciation for the P-I,” Steve continued, “and it’s nothing but tragic to see it closing its doors. It did some very good investigative reporting. It had a lot of local color. It had a full stable of arts reviewers and some sharp political commentators. It kept the Seattle Times from choking on its constant air of superiority. And it supported some damn good editorial cartooning.” At his blog, Greenberg deploys a self-deprecating sense of humor in reviewing his checkered past—“checkered” meaning, not black and white, but jumping from one thing to another, in this case, a succession of newspapers. “I’m beginning to take this seriously,” he wrote, “I’ve been on six daily newspapers and on every one of them disaster has befallen or would soon fall upon their cartoonists and artists.” He runs through the series, beginning with the Daily News in Los Angeles, then the P-I, then the San Francisco Examiner (where he was the last cartoonist to draw editoons), San Francisco Chronicle (where the editorial cartoonist position deteriorated into news art), Marin Independent Journal (where he was the news artist with benefits to do an editorial cartoon; after he left for his native Southern California, the so-called “art department” evaporated), and the Ventura County Star (where he took the place of a three-person art department and also did editorial cartoons only to have the job eliminated last year in a cost-reduction purge). “I’m kind of feeling like the Joe Btfsplk character in Al Capp’s old Lil Abner strip,” Greenberg concluded, “—the guy who walked around with a perpetual dark raincloud over his head, bringing misfortune wherever he went. I’m not saying I’m bad luck. But perhaps if you have a grudge against some company in the greater Los Angeles area [where Steve now lives] and wish it ill—well, see if you can get me a job there.”

THE DEMOLITION DERBY CONTINUES. Five more full-time staff editorial cartoonists lost their positions in the past month. Bill Garner at the Washington Times in D.C., Robert Ariail at The State in Columbia, South Carolina, Bill Day at the Commercial Appeal in Memphis, and Gary Brookins at the Richmond Times-Dispatch, and, just a few hours ago, Alan Gardner at the DailyCartoonist.com reported that Tom Meyer has taken a buy-out from the doomed San Francisco Chronicle, probably a good move on his part, assuming Hearst can make the payment despite shuttering two papers (if, as everyone predicts, the Chronicle will soon join the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in the newspaper graveyard). Editor & Publisher subsequently reported that in a column published April 6, editorial page editor John Diaz wrote: "Tom's departure will deprive me of one of my favorite moments of the day: When he would bring in three or four rough sketches of editorial cartoons. I'll also miss his insights—and, often, levity—at our weekly planning meetings. Tom is every bit as quick-witted in the office as his cartoons are on the page. However, I am happy to report that Tom does have plans to freelance or syndicate his work—and, once he does, we will be among his customers." Meyer had been with the paper since 1981, about 28 years. Garner, who has been the staff editorial cartoonist at the Washington Times for 20 years, lost his job there in mid-February. Garner had little indication that his job was on the line. The management brought in "professional headhunters" to analyze the paper’s situation, Garner told fellow editoonist Rob Tornoe: they took note of existing systems and personnel, and figured out what they could do to improve the paper for the future. Back in August, for instance, the decision was made to outsource the Times printing to the Baltimore Sun, saving the millions of dollars it would have taken to maintain their outdated presses. The whole time the headhunters were lurking about, Garner said, “ I was being told, ‘Hey Bill, keep up the great work Bill, good stuff Bill,’" Garner said. “Then they told me that my job was being eliminated, and that I had a week before I got my walking papers." Garner says the paper’s model now is the Wall Street Journal which doesn’t use editorial cartoons on their opinion pages. Garner hopes to find new outlets for his cartoons, and he sent samples to Creators Syndicate. Meanwhile, he’s devoting time to painting and just taking one step at a time. Said he: “I understand completely, and there are no bad feeling about the situation because it's a business, that's the way it goes. You've just got to roll with the punches." Still, we can detect a little resentment in his remarks about the way the paper treated him: "They were talking hot air up my ass for months when they knew all along they were going to be shoving me through the door.” Ariail quit, effective Thursday, March 19, after turning down a part-time version of his job that he was offered in the midst of cost-cutting measures taken by the paper’s owner, the McClatchy Company, which cut wages 2.5 - 10 percent and, reported The State’s Chuck Crumbo, laid off 38 staff (including Ariail’s boss, editorial page editor Brad Warthen). Ariail has been at the paper for 24 years, and at 53, he hopes to find another job drawing editorial cartoons. He’s syndicated by United Media, but as Bill Day remarked, “Syndication pays a pittance.” Day, who is 61, was devastated by his firing. Interviewed by Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs within hours of getting the bad news, Day said: “They dumped me with not even a farewell cartoon. I had to turn in my ID card. ... My last day is the 27th, but my real last day is now (March 19). ... It was a terrible shock. I don't know what I'm going to do. I've got a family to support and my 401(k) is shot and I might lose my house. I'm a total wreck right now. I'm at a total loss of even what to think. ... I've been in political cartooning my whole life. ... I don't know what I'm gonna do. The only thing that keeps running through my mind is how terrible this is, at this juncture in history. America just elected a black man as president and already the forces of reaction are trying to destroy [his administration]. I'm not going to be on board to fight the bigots—these forces of reaction that are trying to destroy him.” A liberal-minded guy in “the Deep South,” Day said: “You wouldn't believe the stuff that I get through the transom—the bigotry. I'm a lightning rod. ... These people are just wicked when it comes to politics—you're talking about the ultimate Rush Limbaugh people. I won't be on staff to fight it.” And fighting is what he’s been allowed to do; Day had only praise for his editor, Otis Sanford: “He's given me total freedom. It's the only time in my career I've had this much [freedom]. He has not censored me, and he's taken the heat. He's an African American editor and he knows what I'm about in the South and he's let me do what I had to do in the South. I can't tell you how great that is.” Like many editorial cartoonists, Day is baffled by the tsunami of firings of his brethren. “I don't understand why, when you're going to a visual medium [online], why you want to get rid of cartoonists. It's made for cartoonists. ... We're like the Jimminy Cricket of the newspaper. We're the conscience." Brookins is reportedly among the 59 employees terminated at the Times-Dispatch on April 2; in addition to his editooning gig at the paper, he produces the panel cartoon, Pluggers, and draws the comic strip Shoe, both jobs he inherited when Jeff MacNelly died in 2000. Steve Greenberg, writing in his blog at blog.cagle.com, expressed a common criticism of newspaper management. Commenting on the firing of Bill Garner at the Washington Times, Greenberg said: “Cutting the best visual people as a strategy to survive in an increasingly visual age is already idiotic, but this situation [at the Washington Times] has a couple additional twists. First, the entire editorial page staff of a dozen people was forced to reapply for their own jobs. This loathsome practice has been used in places such as the Oakland Tribune and the Long Beach Press Telegram as a tool to bust unions, throw out seniority, and humiliate workers by rehiring them, often at drastically reduced salaries. But the real pretzel logic here is in the words of the Times’ associate publisher and general manager Richard Amberg, who stated the Times wanted to use less syndicated material and more of its own content: “We want fresh content, timely content, lively content,” he said. “Things (syndicates) offer appear on the Web before they are syndicated. “So what does he do?” Greenberg asks sarcastically: “He cuts the cartoonist—some of that fresh content he says he values—meaning they’ll no doubt run syndicated cartoons instead —some of that not-fresh, not-unique content he seems to dislike—in direct contradiction of his supposed goals. Unbelievable. And to lose such an important voice [Garner’s], one that’s been there since 1983, in a paper that’s trying to offer the alternative view to the Washington Post, is sad … and stupid. Publishers across the country have whacked about 20 staff editorial cartoonist positions in the past year. These all provided fresh, unique content to their newspapers, and were pretty much all replaced by the not-unique content of syndicated cartoons. The less unique content a paper has to offer, the less grip they have on existing readers, who may migrate to reading news online—costing subscriptions, which cuts newspaper revenues, which accelerates the downward spiral. And on it goes.” Ted Rall, the current president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) and a syndicated columnist as well as a editorial cartoonist and caustic gadfly, lately devoted an entire column to the idiocy of the current practice of firing editorial cartoonists; excerpts: “We Americans live in a golden age of editorial cartooning. Never has the profession been as ideologically, stylistically or demographically diverse. Never has the art been as daring or ambitious. Never have cartoons been as popular or, thanks to the Internet, as widely read. Yet American editorial cartooning is in danger of disappearing entirely—murdered by editors and publishers at the major magazines and newspapers. An editorial cartoon is like nothing else in a newspaper. Editorial cartoonists don't need any special degrees. Unlike reporters and editorial writers, they don't even have to pretend to be ‘fair.’ Moderation in what Jules Feiffer called "the art of ill will" is the ultimate vice: boring. A great political cartoon can do things no news article or editorial can. It can expose hypocrisies and ideological contradictions with the stroke of a pen and the flash of an eye. It can connect seemingly unrelated events to point out a theretofore unnoticed trend. At its best, an editorial cartoon can prompt readers to rethink society's basic assumptions. ... Editors of the big daily papers and the newsweekly magazines know what makes a good cartoon: they post them on their walls and in their cubicles. What they run in their publications, on the other hand, is what we cartoonists constantly refer to as the worst of the worst: dull clichés, hackneyed metaphors, idiotic gags about the news reminiscent of Jay Leno's middle of the road comedy style. They're safe. They don't anger readers. But they don't matter.” Editors who opt for safety rather than disruption are signing death warrants, Rall insists. “Newspapers are under financial stress,” he acknowledges. “But they won't survive by selling a diet of bland and boring to consumers who have more information options than ever before. Refusing to embrace what was cool and relevant in the '70s set the stage for the death of music radio in the '80s and '90s—supplanted by news talk and satellite. Whether it's cartoons or music reviews or political analysis, playing it safe is suicide.” (Read the whole screed at uexpress.com/tedrall/?uc_full_date=20090304 ; or go to rall.com and look around.) At the ComicsReporter, Tom Spurgeon takes exception to Rall’s effort. “I'll repeat what I said after the last one of these jeremiads: it isn't good enough. The decline of staffed editorial cartooning positions is beyond the point where a bunch of strong assertions cleverly made and presented with passion will convince newspapers that what they're doing isn't necessary. I don't see anything here that would convince me as a newspaper editor that I wouldn't be better off simply picking up a syndicated Ted Rall cartoon or taking my staff cartoonist investment and hiring a video blogger. Once again, I challenge Ted Rall and the AAEC to come up with five models of newspaper-cartoonist relationships that work for those newspapers, specific examples and detailed reasons why they work, and how newspapers can develop that within their own publications. Having not one but two skilled cartoonists sure didn't save the Rocky Mountain News. Fair or not, that's the tenor of the conversation right now.” Spurgeon has a point, a good one. Unhappily, pronouncements like Rall’s produced as institutional statements are reluctant to single out individuals for the kind of praise inherent in proclaiming “newspaper-cartoonist relationships that work.” I’m not in deep enough to speak with broad authority, but I can think of a few such instances. The classic irrefutable instance was Herblock at the Washington Post—and today, his successor, Tom Toles. Both were/are powerful voices that lent stature to their newspaper. And Ann Telnaes with her animations on the Washington Post’s website is another instance of a cartoonist making a difference for a newspaper. At least, the Post thinks so: after trying her brand of cartooning online for a few months, they increased the number of animations to three a week, and Telnaes is now making a living wage. Spurgeon is right about Rall’s screed: the cry of anguish, however carefully couched in reasonable albeit forceful argument, will not, itself, save editorial cartooning. But Spurgeon’s expecting editorial cartoonists (like Ed Stein and Drew Litton at the Rocky Mountain News) to save their papers—to rescue them from the bad financial decisions made by management—is going too far. Spurgeon has lofted a faux weather balloon with this expectation. The departures of Garner, Ariail, Day, Brookins and Meyer—plus the almost simultaneous death on February 13 of “Corky” Trinidad at the Honolulu Star-Bulletin (see “We’re All Brothers” below), who has not yet been replaced—the total number of full-time staff editoonists at the nation’s newspapers has been reduced to 78; it was 101 last May. The victims in two earlier firings this year, Lee Judge and Dwane Powell, have worked out freelance arrangements with their previous employers, the Kansas City Star and the Raleigh News and Observer, accepting remuneration that is considerably less than the salaries they once earned—circumstances similar, I’d guess, to that which was offered to Ariail. Judge, incidentally, was just named as this year’s winner of the John Fischetti award for excellence in editorial cartooning. The winning cartoon shows a soldier’s helmet perched on a rifle with the caption “Price of Gas.” Said Judge: “The timing is wonderful. My job has recently become part-time and to win a prestigious, national award like this gives encouragement not only to me, but to the people who fought to keep my cartoons in the paper. Editorial cartooning is struggling to survive, not because it lacks popularity, but because it’s often not deemed absolutely crucial. I strongly disagree. If we’re in a battle for readers, why get rid of the one person on a staff best equipped to compete with television and internet?” Well,