|

|||||||||||||

Opus 238 (February 14, 2009). We take a long plunge into Kirk Anderson’s miraculously satirical graphic novel, Banana Republic, and review a new biography of Playboy cartoonist Shel Silverstein. Other than that, it’s the usual ganglia of idiocy—news, comic book reviews, cartooning lore and a smattering of history. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order: NOUS R US: financial fate of comics biz, animated cartoons and the Oscar, Bloom County compendium due, U.N. threatens cartoonists, new George Herriman website THE FROTH ESTATE: more nastiness NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL: Mort Park returns to life, examples of verbal-visual blending and jokes possible only in comic strips, Randy Glasbergen EDITOONERY: Pat Oliphant expounds, Daryl Cagle on racism with Obama, racist cartoon? BOOK MARQUEE: Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury, Pat Bagley’s new book about Utah, Basil Wolverton’s Bible, Shel Silverstein biography, and the Best Satirical Graphic Novel of them all—Kirk Anderson’s Banana Republic CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST: How Chief Justice John Roberts re-wrote the Constitution FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE: El Diablo, Femme Noir, Smoke and Guns (a graphic novel) ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY: How to vanquish Afghanistan And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— POSSIBLE CORRECTION: I’m not sure about this, but Mike Rhode is, and that’s good enough for me. When I said last time that the Adam Hughes nude in the February issue of Playboy was, probably, the only naked AH!-girl in general circulation, Mike wrote to say he remembered some Hughes nudes in Penthouse Comix. If so, then Penthouse Comix holds the record. NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits Barbie, the sexy plastic doll based upon a German cartoon character, will soon be fifty. ... Actor Hugh Jackman, interviewed a couple months ago in Playboy, said this about his experience at the San Diego Comic-Con: “It’s as close as a film actor will ever come to feeling like a rock star. You walk out on that stage before 7,000 amped people, and the energy’s overwhelming. ... I owe my career to that [Comic-Con] crowd.” ... “Kung Fu Panda” won big at the 36th annual Annie Awards staged on January 30 by the International Animated Film Society at the U. of California - Los Angeles, roundly outclassing “Wall-E,” which, according to the Los Angeles Times, knowledgeable persons everywhere expect to win an Oscar. An upset, yes, but we are, after all, in the season of unexpected victories. ... Forrest J. Ackerman’s treasures are scheduled to be auctioned off at the end of April, saith the Associated Press. Among the memorabilia: a first edition of Dracula signed by author Bram Stoker and actors Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, Vincent Price, and others; a first-edition of Frankenstein, signed by the author, Mary Shelley; the ring Lugosi wore as Dracula in the 1931 movie and the Dracula cape. We’re still guessing: has the “new economy” (i.e., the crashing one) affected the comics biz? Or not? The New York Comicon over the first weekend in February registered more than 77,000, over 10,000 more than last year’s crowd. And in ICv2 reports about 2008, graphic novel sales increased from $375 million in 2007 to $395 million in 2008. Manga, on the other hand, took a dip—from $210 million in 2007 to $175 million in 2008. Comic books also went down a little—from $330 million in 2007 to $320 million in 2008. Bending over backwards to look at the bright side, the ICv2 folks decided to combine the “domestic” market, graphic novels and comic books, to proclaim a slight increase from $705 million in 2007 to $715 million in 2008. But that gain was produced by bending over backward. During the New York Comic Con, Dark Horse announced a new series that will be published under the rubric Noir, a pitch-black anthology of crime stories from top creators such as Brian Azzarello (100 Bullets), Ed Brubaker (Criminal), David Lapham (Stray Bullets), Rick Geary (A Treasury of Victorian Murder), Chris Offut (HBO’s True Blood), Paul Grist (Kane), Jeff Lemire (Essex County Trilogy), Alex de Campi (Smoke), M.K. Perker (Cairo), and the Fillbach Brothers (Maxwell Strangewell). Diana Schutz is editing the new anthology, which is slated for release next fall. The contributing artists are no less distinguished than the writers: Sean Phillips (Criminal), Eduardo Barreto (Cobb), Gabriel Ba (Umbrella Academy), Fabio Moon (Sugarshock), and Dean Motter (Mister X). Rod Decker at KUTV reported last November in the wake of the election results on Proposition 8 in California that attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints continue, notably by the creators of South Park, which, they say, will appear on Broadway early this year as a satirical musical called “Mormon Musical.” Jan Shipps, a leading scholar of Mormonism, said the Church image rode high after the successful 2002 Olympic Games but faltered with Mitt Romney’s bid for the presidential nomination of the Republican Party. She predicts the fallout from Proposition 8 may harm the LDS missionary effort, and retard the Church's growth. Batwoman, DC Comics’ highest profile lesbian character, will assume the leadership roll in Detective Comics with the April issue, No. 854, in a story arc written by Greg Rucka (Queen and Country, Whiteout, Action Comics) and illustrated by J. H. Williams III (Promethea, Desolation Jones). The new story line featuring Batwoman, who was introduced in the eleventh issue of DC’s 52, is timed to coincide with Batman’s “death-induced” absence from his flagship Detective Comics series. According to the source for this story, which, alas, I’ve misplaced, much discussion at DC has been devoted to whether to do a solo mini-series with the character, who is controversial solely because of her sexual orientation. DC has apparently decided to proceed cautiously and gauge reaction to the character’s appearance in Detective Comics. Nichole Hollander’s strip, Silvia, after three decades in syndication, still appears six days a week in 17 newspapers via Tribune Media Services. Silvia, Hollander reflected during an interview in the Chicago Tribune lately, is a combination of her mother and two of her mother’s best friends, and women who lived on the Windy City's West Side who gave Sylvia what Hollander calls "a rough-edged, Chicago sense of humor." When she first approached a syndicate with the idea for Silvia, she was told it was "deep but narrow," a comment she assumed meant "appealing to women." To which she remarks: “C'mon— women buy newspapers." ***** ACADEMIC QUIRKS. Four of the top box office earners in 2008 were animated films, we are reminded by Robert Butler at the Kansas City Star: WALL-E," "Kung Fu Panda," "Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa" and "Dr. Seuss' Horton Hears a Who!" Their combined earnings, $778 million. And the Oscar nominated “Waltz with Bashir,” about war, guilt and memory as filtered through the experiences of former Israeli soldiers, is violent and deeply disturbing. "Serious" cartoons, mutters Butler— feels like a trend. "It's a lot more than a trend," said Joe Beck, author of The Animated Movie Guide and Outlaw Animation. "It's absolutely here. And it's growing." Said Leonard Maltin, a noted film historian: "The idea that animation can be serious isn't new. You could go back to Walt Disney's ‘Fantasia,' which is hardly a children's film. Or ‘Animal Farm' in the '50s, which was about as serious a film as you could get. But as good as they were, both movies were commercialdisappointments." The last big push toward animation for adults was in the '70s with the sci-fi themed "Heavy Metal" and the movies of Ralph Bakshi," Maltin said, adding: "Bakshi asked why we couldn't do ‘War and Peace' in animation. In his `Fritz the Cat,' there's a death scene. With blood. Bakshi thought anything was possible. But audiences weren't ready yet. At least the mass audience wasn't. And while Bakshi's initial success got other people thinking that they could make animated films for adults, it was followed by 10 years of failure." Beck meanwhile continues to be frustrated by the "ghettoization" of animated films by the Academy Awards, which began honoring animated features only in 2001 and which has nominated an animated film for Best Picture only once: "Beauty and the Beast" in 1991. ***** Come October, we’ll see the first of five volumes from IDW collecting the entire run of Berkeley Breathed's Pulitzer Prize-winning comic strip Bloom County. Edited by Scott Dunbier and designed by Eisner Award-winner Dean Mullaney, the five hardcover volumes will be part of IDW's Library of American Comics Imprint, which, so far, has included Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, and Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie. Despite the success of earlier compilations of his strip, Breathed had resisted the idea of printing new editions for years. "The fact that so much of the content is so badly dated just kept me from getting excited about it," he explained. But IDW persuaded him by saying it would publish “context pages” throughout the books to bring new readers up to speed on the political humor that may not have withstood the test of time. Breathed will also produce a new foreword for the series. "I'm sure I'll have something to say," the perpetually outspoken Breathed remarked. "I always seem to, alas.” We may expect a few bleak witticisms from him on the state of the art these days. But that will be nothing new. Back when he was writing Bloom County, Breathed kept repeating that the comics page was perhaps the single best venue in a newspaper to put forth political commentary because most readers avoid opinion columns like the plague. But today, Breathed fears that the medium itself may be obsolete. "Nobody under the age of 60 reads any part of the newspaper anymore," Breathed said, intoning his usual funereal assessment. "Editorial pages are rather musty, empty crypts now. The New York Times op ed page is still fun. And they never had comics. I sense a connection.” In his opinion, the comic strip audience has all but dried up and blown away, but then, he hasn’t had much luck in the last two incarnations of Bloom County, Outland and Opus, both Sunday-only strips, and his failure with them may be coloring his opinion of the entire medium. My contention has always been that his kind of satirical comment fares better if it appears daily; his weekly strips simply couldn’t gather the momentum that would produce the adulating readership he once enjoyed. And without that readership, Breathed concluded that the whole medium must be dead instead of concluding that his stew of humor was not cut out for weekly ingestion. ***** Nat Hentoff, who is something of a frothing-at-the-mouth alarmist on matters involving the First Amendment—but who can seldom, if ever, be faulted for it—is upset by a “nonbinding” United Nations resolution passed on December 18, 2008 that urges nations to provide “adequate protections” in their laws or constitutions against “acts of hatred, discrimination, intimidation and coercion resulting from defamation of religions and incitement to religious hatred in general.” Introduced by Uganda “on behalf of the 57-member Organization of the Islamic Conference,” the measure passed 83-to-53 with 42 abstentions; among the nay-sayers, the U.S., a majority of European nations, Japan, and India. Here’s the kicker: “Those voting in favor say they do not want to limit free speech but do intend to stop such expressions as the 2005 Danish cartoons disrespecting the prophet Muhammad that ignited violent protests by Muslims around the world.” Yup: we’re not through that swamp yet, kimo sabe. Among the problems, if “defamation of religion” were to become a crime under international law (as a result of the impetus provided by this U.N. resolution), “nations would be able to seek extradition and trial abroad of persons who make statements critical or offensive to one or all faiths anywhere in the world.” And so, for instance, the Danish cartoonist, Kurt Westergaard, who drew the infamous Muhammad in a turban-bomb cartoon, could be arrested in Denmark and sent off to Jordan, where he and eleven of his confederates are charged with “threatening the national peace.” Hentoff, in his column in the Village Voice, ran one of the Danish Dozen, Westergaard’s cartoon, although, as he takes pains to note, almost no American newspaper published any of the cartoons (except the Rocky Mountain News, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and the New York Sun). “I was damned if I’d be intimidated for doing my job as a reporter,” says Hentoff, although he admits “for a couple of weeks I was more vigilant than usual walking the streets,” but, he concludes, “I’m still here.” And he’s rightly exercised about what might befall “defamers of religion” and, in the process, freedom of speech if the U.N. “nonbinding” resolution somehow gets binding. We live in gutless times, alas, and as the Bush League demonstrated again and again—always with the meek compliance of Congress—despite our girth we lack the stomach for upholding our Constitutional rights. The Danish Dozen is the emblem of our failure of will. ***** During an interview by a couple of young wide-eyed Newsarama stringers during the late New York Comicon, Michael Uslan, Batmaniac and champion of comic book superheroes everywhere, reminisced about attending his very first comicon, which, he said, was 45 years ago in New York, “the first comic book convention ever held anywhere,” he intoned, grinning in smug satisfaction. He means, of course, the con arranged in the summer of 1964 by Bernie Bubnis, who also coined the term “comicon.” But it wasn’t the very first comicon: the first was convened a few months before, in April 1964, in Detroit by Robert Brosch. Uslan may be permitted his hyperbola, I suppose, if we assume that the New York affair was all about comic books and nothing else: the Detroit con, on the other hand, included science fiction and movies in addition to comic books. The number of people carrying library cards these days is increasing in tandem with unemployment, according to a report in the Rocky Mountain News. “Public libraries nationwide are seeing a surge in demand for services,” reports Julie Hutchinson: according to the American Library Association, 5 percent more people in 2007 than in 2006 carried a library card. Parents check books out of the library for their children instead of buying them; and reference desks are fielding more and more questions about books on resumes and networking. One of the ubiquitous images of the last year is the “Hope” poster designed by Shepard Fairey of a red-white-and-blue Barack Obama looking upward, as if to the future, the features of the future president etched in heavy chiaroscuro and highlighted with a splash of red along one side and dashes of blue and white. Fairey, a street artist in Los Angeles, acknowledges that his image is based upon an Associated Press photo taken by Mannie Garcia; AP says it owns the copyright on the photo and wants credit and compensation, given the considerable financial success of the image, which was reproduced on hundreds of thousands of posters and stickers. At last report, Fairey has appealed to a judge to find that his use of the AP photo is not in violation of copyright law. Fairey’s attorney, Anthony Falzone, executive director of the Fair Use Project at Stanford U. and a lecturer at the Stanford Law School, believes Fair Use permits Fairey to do what he did—which was to convert the graduated colors of a photograph to a line-art image. The outcome of this contest could alter the Fair Use concept forever. While the case pends courtward, Fairey was arrested February 6 for “tagging” property with graffitti; the street artist was on his way to the Institute of Contemporary Art for the kick-off event inaugurating his first solo exhibition, called “Supply and Demand.” A

new website was launched last month by the incredible Craig

Yoe, Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. READ AND RELISH Correspondent Jim Ivey has been reading and pondering an array of statistics about us all: 90% of coupons are not used 70% of “home dust” is dead skin 88% of us put the right shoe on first (50% put the left sock on first) 33% flush while on the toilet Odds of being struck by lightning: 1 in 600,000 Odds are 1-125 that one will die in a traffic accident Average U.S. adult sleeps approximately 3,000 hours in a lifetime 2/3 are right-handed; also 1/4 are left-handed—so are the balance ambi-dextrous? 30% of the “educated” read in the bathroom Average U.S. marriage lasts 7 years 30% female teenagers dye their hair 20% men and 6% women sleep naked 90% flowers have bad odors Lawyers, Jim adds, are listed under “Most Hated” below snakes but above dentists. “Figures can lie,” Jim concludes, “and liars can figure.” THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution The print version of the Missourian newspaper is reducing its frequency from seven days a week to five, part of an effort, says Tom Warhover at columbiamissourian.com, to “cut expenses for a anewspaper that’s been in deep deficits for a long time.” So far, however, the paper is not eliminating its comics page, but the editors are considering whether, for instance, to drop Family Circus, at $17/week, that could save thousands over a year. NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Has Mort Park, who died two years ago in Rudy Park, come back to life? He showed up in the strip the week of January 26—a phantom? an ectoplasmic extrusion?—and on February 9, the nefarious authors of the character’s erstwhile death, writer “Theron Heir” (not his real name) and artist Darrin Bell (real name; sorry) published a text exposition in three panels, explaining, apparently, that Mort was “very much alive.” Comic book characters can be depended upon to return from the grave regularly; now, it seems, so can comic strip characters. Can’t keep a good character down. And

now, today’s lesson in cartoonery appreciation: words and

pictures, words and pictures. In the best examples of the

cartoonist’s art, the verbal content blends with the visual to

create a new meaning, that neither words nor pictures can achieve

alone without the other. By way of object lesson, here are three

cartoons from a recent issue of Parade, the

Sunday newspaper supplement. (Peruser

Alert: probably all the picayune prose

that follows will make much better sense if you print out the visual

aids in order to have them before your very eyeballs as you ponder

the text.) In

the next visual aid, the comedy in the first two strips cannot easily

exist in any medium other than comic strips. The

next two pages of strips and cartoons again give us comedy that

cannot be achieved in any other medium as readily. Glasbergen, who told slapstik.com that he works alone “unless you count the two Siamese cats in my studio who like to perch on my desk and help me out,” began selling cartoons in 1972 while he was still in high school. He’s a big fan of stand-up comedy. “I think Steven Wright is brilliant and Mitch Hedberg always cracked me up. As a teenager I used to love staying up late to see Don Rickles and Rodney Dangerfield on Johnny Carson’s ‘Tonight Show.’ I don’t think I could tolerate the lifestyle, but stand-up comedy has always been my secret fantasy career.” But he enjoys freelancing cartoons—magazine cartoons, greeting cards, calendars, book illustrations, and so on—“I love the freelance lifestyle, the freedom, the variety of work, the dress code, typing with the cats, etc.” He thinks it would be “cool” to have some of his cartoons animated. “I was a huge fan of the old Max Fleisher ‘Popeye’ cartoons when I was a little kid,” he said. “They’re still fun to look at. I have a bunch of them on my iPhone to watch when I’m stuck waiting for an appointment with the doctor or dentist. My studio is cluttered with a lot of Popeye toys and memorabilia.” What has he learned in 36 years of freelancing? “I learned that my coffee cup needs to be refilled again and that cats can’t type worth a damn.” EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted David Brill, a video journalist at sbs.com, talked with editorial cartoonist Pat Oliphant in the closing hours of the Bush League as Oliphant was drawing a cartoon “recording the wretched legacy that Bush has left behind. Of course, I have mixed emotions about it,” said the displaced Australian. “It's a dichotomous thing because he's given me a great 8-year ride with a match-up of just the perfect villains. And cartoonists, as you know, depend on villains. And so I'm losing probably the best cast that I've ever had and one thing I just have to remember is that politicians will never eventually let you down. They're going to come through with something. ... One of my favorite targets is Cheney. He went out hunting with a friend of his one day and inadvertently shot his friend. And I always thought wouldn't it be nice if he took Bush hunting.” Oliphant said he left Australia in the mid-1960s because “it was a very repressive time in Australia. And everything else seemed to be going on elsewhere, in this country especially. Civil rights was going on, Vietnam was going on, the protests, everything was becoming polarized and in Australia you could do cartoons about the weather.” For years, Oliphant gave away his original cartoons, but his wife, Susan, stopped him. They met 20 years ago while she was running a gallery in up-market Georgetown and the cartoonist was looking for somewhere to display his work. Now she’s aiming to build up a substantial collection f his work. “Daumier's been my hero since I can remember,” Oliphant said. “Went to jail a few times for insulting the King and the government. And the drawings are so good, the drawings are so beautiful. That's always been a model for me. ... Being a cartoonist is a great privilege really,” he continued. “I say things that people want to say. I'm fortunate enough to have a forum in which to say it. And express the feelings of many people.” He was putting on rubber gloves preparatory to working in charcoal. He muttered a little about his usual targets, politicians all. The rubber gloves made him think. “Cartooning and proctology have an awful lot in common,” he said. ***** Daryl Cagle, who, blogging away at one of his websites, msnbc.com, threatens to become a regular guest columnist here, wrote about Obama, again, recently: Obama seems like an easy guy to draw; he's skinny, has a big chin, expressive eyebrows and lips. As it turns out, no matter how a cartoonist draws Obama, somebody gets mad. ... I worked for 20 years as a cartoon illustrator, doing drawings for books, magazines and advertising. I was often given clear guidelines on how I was supposed to draw African Americans—with "small noses" and "thin lips." I was instructed to make any crowds of cartoon characters racially diverse, but only diverse in color, not in facial features. Thick lips and wide noses on African-American faces would be returned to me for correction, with a polite reminder of the corporate policies on depictions of minority facial features. Cartoonist Gary McCoy has been lambasted by readers, and by Salon.com, for drawing racially insensitive, big lips on Obama. Some cartoonists have drawn attention for giving Obama blue lips. Canadian cartoonist Patrick Corrigan of the Toronto Star had an Obama cartoon killed by his editor because of "racist" blue lips. Thomas "Tab" Boldt of the Calgary Sun and Cam Cardow of the Ottawa Citizen have also been rendering Obama with blue lips. Corrigan tells me that everyone in Canada, in the winter, has blue lips. Readers of my blog explained to me that blue lips are racist and pointed out an old racist expression "blue gums," which was a new one for me. Corrigan tells me he'll be switching to purple lips, Cam will be giving up on the blue lips and Tab was laid off. That may mean the end of blue lips for Obama. ... I'm considering going all the way, making Obama completely blue (if that's not racist). There seems to be an expectation that political cartoonists are mostly liberals who love Obama and will find it hard to make fun of him in cartoons. Some cartoonists have complained in the press that Obama is dull and there is little to criticize about him — we have a term of art for cartoonists like that: we call them "bad cartoonists." It is the job of an editorial cartoonist to dislike everybody. Political cartoonists have nothing to gain by being in favor of anything. Cartoons that support anything are lousy cartoons. There is plenty for everyone not to like about Obama— and with the porky stimulus package and tax-evading cabinet appointments, there's more every day! The cartoon version of Obama will continue to evolve quickly. If we ever actually see Obama smoking a cigarette, he will always be smoking in cartoons. He may turn different colors, and he'll grow or shrink with his performance. Obama's ears will keep growing no matter what he does. As Obama's honeymoon passes and the caricatures become more severe, I expect the complaints about racism in the cartoons will also grow more severe. But I don't care. I'm making Obama blue today. ***** Here’s

a cartoon that landed on one of the editorial cartoonists lists with

a couple questions: Is it funny? And: Is it racist? Speaking of inspirational names, I suppose you’ve run across a list of new “Obama” terms with definitions. Here are a few: Obamaphoria—the post-election rapture that swept over his supports; Obamatopia—the political paradise predicted by his staunchest followers; Obamatrons—the policy wonks who will occupy the West Wing; Obamanator—Hollywood-inspired nikckname; Bamelot—description of his presidency, from a New York Post headline that referred to JFK’s “Camelot.” And so it goes. Are these racist terms? ***** And now, a cheerful note to end on. Editor & Publisher reports that the News Leader in Staunton, Va., did a feature recently to celebrate its editorial cartoonist, Jim McCloskey, who is celebrating 20 years of cartooning at the newspaper. And he’s still there. "I've never apologized for a cartoon," he said. "A cartoonist is supposed to make you think. I don't claim to be the only opinion or the right opinion. That's why I sign my name on them." Nice to know an editoonist somewhere is still working on the staff of a daily newspaper. CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. The story is fraught with surreal elements. Nadya Suleman, the 33-year-old woman who had eight children by cesarean section on January 26, is single, unemployed, and lives in her mother’s house with her six other children, ages 2-7. Some people in the fertility business are wondering if maybe someone should have stopped this woman when she came in wanting just one more child, a seventh. Suleman has a degree in psychology and hopes to continue work towards a masters. Her mother says she’s good with children. BOOK MARQUEE Short & Quick Reviews of New Books A new book and probably the first booklength critical study of Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury arrived last fall from the University Press of Mississippi, one of my publishers (and one of the better ones, at that). Kerry D. Soper’s Garry Trudeau: Doonesbury and the Aesthetics of Satire (186 6x9-inch pages, some illustration, all b/w; $22 in paperback, $50 in unjacketed hardback) is divided into chapters that discuss the history of the strip, analyze Trudeau’s satirical methods in the context of the medium, and examine the aesthetics of the strip. Soper’s is an ambitious project, and his having attempted it—and Mississippi’s having published it—is, of itself, testimony to the social status and influence of the comic strip. I haven’t read this yet, but I’m looking forward to it. The Salt Lake Tribune’s Pat Bagley, one of my favorite bomb-throwing editorial cartoonists, has a new book out: Bagley’s Utah Suvival Guide. It’s probably not much about politics except, maybe, the Mormon sort. Bagley claims the book has “more facts and near-facts per pound than anything currently available” about the state. Look for it on the Web, kimo sabe, all I have is a news release from kcpw.org. ***** POWERHOUSE PUBLICATION. For all of us, cognoscenti and commoner alike, the words “Basil” and “Wolverton” are likely to summon up congeries of hilariously grotesque images, first among them, probably, “Lena the Hyena,” a stunningly ugly female visage with which Wolverton won a contest in Al Capp’s Li’l Abner in 1946. For almost none of the aforementioned crowd, however, is Basil Wolverton a Christian minister who spent twenty years illustrating the Bible. Yet both of these Basil Wolvertons are the self-same individual, who is now put before us in The Wolverton Bible: The Old Testament and Book of Revelation through the Pen of Basil Wolverton (312 7x10-inch pages, b/w in hardcover; Fantagraphics, $24.99), with an introduction by Wolverton’s son Monte, who draws political cartoons syndicated by Cagle Cartoons and edits Plain Truth magazine, a publication of the Worldwide Church of God, the evangelical sect founded in 1934 as the Radio Church of God by Herbert W. Armstrong. For some of us, not all of the Wolverton oeuvre can be described as “goofy pictures” decorated with unrelenting visual puns (Powerhouse Pepper, his most enduring creation, lasting from 1942 until 1952; the cowboy Bingbang Buster, Mystic Moot and His Magic Snoot, etc.): his earliest comic book creation was Spacehawk, hero of a space opera that Wolverton played straight for 30 episodes, 1940-42. Still, given the evidence, few of us would expect to find him drawing Bible stories. Wolverton made his first sales to the embryonic comic book industry in 1932 at the age of 23; a few years later, he met Armstrong via the radio preacher’s broadcast, “The World of Tomorrow,” which was often playing as the cartoonist worked at his drawing board. In 1941, Wolverton was baptized by Armstrong, and in 1943, he was ordained an elder in the WCG. A decade later, about the time Powerhouse Pepper stopped appearing in funnybooks, Wolverton, at Armstrong’s behest, began producing illustrations for the Book of Revelation. Soon thereafter, he started illustrating the Old Testament, a project he finished twenty years later in 1972. “From the beginning,” writes Monte Wolverton, “both Wolverton and Armstrong sought to create a story that followed the Biblical account more accurately than children’s Bible story books on the market in the 1950s. ... Wolverton did not want his story to seem religious, sanctimonious or churchy. He wanted it to come across as a straightforward account, with edgy, challenging illustrations. He hoped his product would be read by secular types as well as religious. The Biblical account of Noah’s flood, for instance, was popularly portrayed with cute animals, a big boat and a kindly old man. The Biblical narrative, by contrast, is a disaster story of cataclysmic proportions, in which millions of people and animals violently die. Wolverton’s challenge was to portray the Biblical accounts accurately without traumatizing children too much.” With the Fantagraphics book before us, it’s clear Wolverton succeeded. His pictures, distinguished by his usual copious hachuring and cross-hatching, are illustrative, not comedic, entirely straight and, sometimes, a little terrifying. The illustrations, accompanied by Wolverton’s plain undemonstrative captions, were first published serially in Plain Truth; subsequently, they were bound in six volumes and re-issued. The volume at hand, a project initiated and sponsored by WCG, is the first time all of Wolverton’s Biblical work has been published in a single tome. At the end of the book, several pages present raucous pictures in Wolverton’s typically manic visual mode, all done, again at Armstrong’s request, for WCG college publications and, I gather, never before reprinted. These gyrating images are alone worth the price of the book, but if you spring for the whole thing, you also get some of the most stunning black-and-white images of Biblical stories ever produced. Wolverton suffered a stroke in 1974, effectively ending his drawing career, but he probably would not have done the New Testament in any case: Armstrong believed that picturing Jesus was a violation of the Second Commandment. Wolverton died in 1978. Armstrong’s death in 1986 was followed by “profound doctrinal and cultural reforms” within WCG, reports Monte Wolverton. His father would have welcomed these reforms, says his son, which may be beside the point: the Wolverton Bible presents the traditional Bible stories without much doctrinal bias that I’m able to detect. Here are a few sample pages: one from the Flood story (with a towering ark in the background), one from the Revelation series, and, finally, a page of the usual Wolverton idiocy culled from the college drawings.

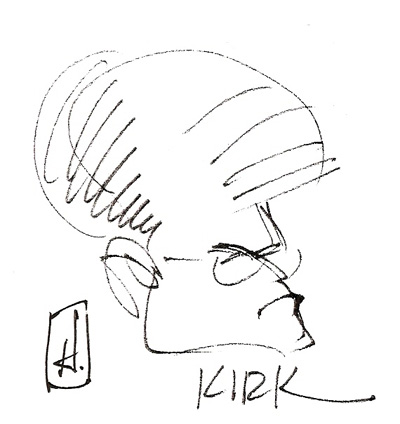

***** A Feast of Shel Silverstein Lore. I missed this book when it first came out, in November 2007, and it doesn’t deserve missing: A Boy Named Shel: The Life and Times of Shel Silverstein (250 6x9-inch pages, hardcover; Thomas Dunne Books, $24.95) is a slim but surprisingly good book about one of the cartooning profession’s most eccentric but indisputable geniuses, who branched out into children’s books, poetry, songs, and plays. Its author, Lisa Rogak, has written more than 40 other books on a stupifying array of unrelated subjects—The Everything One-Pot Cookbook, Time Off From Work, Death Warmed Over, The Man Behind the Da Vinci Code: An Unauthorized Biography of Dan Brown, Haunted Heart: The Life and Times of Stephen King, and Barack Obama in His Own Words—a resume the whizzing variegation of which alone qualifies her to write about another creative scatterbrain, Silverstein. Her book is mostly about the scatterbrain of Silverstein’s creative genius, his so-called working methods, and his unconventional lifestyle. To say Silverstein’s creativity was of the scatterbrain sort is not to disparage the man or his achievement. That’s the way he worked. He went from drawing a cartoon to writing a song to illustrating one of his children’s books to writing a poem or a play or another verse in a children’s book. Then back again. He would leave one project in the middle of executing it if he had an idea that would be more appropriately expressed in one of the other modes of his metier. Eventually, he’d come back to the abandoned piece, but before that, he might stop en route at any of a half-dozen other attractions, including a nearby tavern. Sometimes he even left town and went to another of his abodes—a houseboat in Sausalito, a house in Key West, an apartment in Greenwich Village—before returning to the task he’d left behind. His residences were like his mind—cluttered with bits and pieces, all awaiting his unifying hand. Except that he seldom tidied up the residences. They were heaps of works in progress. His attire was no better. Silverstein tended to wear a favorite article of clothing until it wore out; and he wore it continuously, straight through from store-bought to tatter, without, apparently, laundering it. “Shel always wore the same thing: a tunic that was usually hanging out of his pants. He had the air of someone who is so caught up in what he was doing that he didn’t have time or attention to care about how he looked,” writes Rogak, quoting a Silverstein friend. Silverstein was probably as fragrant as his houses and his wardrobe. Rogak doesn’t say, but I can’t imagine him bathing all that often since he was, almost all the time, in the grip of one creative impulse or another, none permitting him to tolerate the distraction of a few minutes off for a shower. But even if he washed himself three times a day, if he pulled on those clothes he’d been wearing without washing for weeks or months, the impression could not have been magnetic socially. And yet he had his women by twos and threes, by one count (Rogak’s?), over a thousand, matching, doubtless, the tally toted up by his one-time mentor, Hugh Hefner. Silverstein granted remarkably few interviews during his life, but Rogak has diligently searched out a great many of them and conducted a good number of her own—with one-time underground cartoonist and subsequent Playboy art director Skip Williamson, for instance. Williamson met Silverstein while the latter was struggling to produce Different Dances. The struggle, apparently, got easier with another cartoonist in the room, so the two hung out together, their time fragmented into drawing periods, philosophical discussion periods, and periods of song-writing and singing. Rogak quotes Williamson: “Shel believed that if you did a drawing and whited it out and redrew it to change something, it was cheating. But then he’d do a drawing and cut pieces of it apart and rearrange them, and that was okay.” Said one of Silverstein’s editors at Harper: “It was fascinating to watch him draw because he would start by putting his pen in the middle of the page and start drawing, but the picture would emerge from the center and spiral outward.” Another said: “His technique of drawing was very odd. Shel would start out with a couple of lines right in the middle of the page and the drawing would kind of pop out of it.” Rogak’s prose is defaced with illustration very little: a thin slice of slick-paper pages with a few photographs and only one of Silverstein’s cartoons—this one, from his Pacific Stars and Stripes career, pre-Playboy. Presumably, Playboy wouldn’t give her permission to use any of Silverstein’s work from the magazine. Maybe the magazine’s moguls thought anyone who has written 40 books on such a dizzying variety of subjects was too capricious to do justice to their resident vicissitudinary genius; who knows? While this deprives the book of what would have given it much greater appeal in the marketplace, it does not much diminish Rogak’s achievement. She does not ignore the role of cartooning in Silverstein’s career—as did most of the obituaries written when he died, focusing instead on his children’s books and songs—but she does not much analyze its function in his mercurial convolutions either. It is perhaps enough that she quotes Silverstein on his cartooning: “I am a better cartoonist than anything else,” he told Studs Terkel. “I write pretty good, but I pride myself on cartooning. And I can cartoon for a while, but when I have had enough cartooning, I can lay back and do nothing. But if you can do something else, maybe you can write songs for a while. And then you get sick of writing songs.” Silverstein owed his initial success to Playboy, which was the first to publish his cartoons when he escaped the Army in the fall of 1955. Soon he became one of Hefner’s in-house buddies at the Chicago Playboy Mansion, which opened about 1959, but when Hef moved to the Mansion West in 1974, Rogak reports, “Shel felt that Hef and sold out and had let down all those who were with him from the early days.” Silverstein contributed nothing to Playboy from December 1973 to January 1978. Says Rogak: “He was mad at Hef for closing the Chicago Mansion [where Shel lived for stretches during its heyday, and his, as a cartoonist], for ceding control of the magazine to the executive suite, for taking the company public—something that Hef would later regret as well.” The book brims with such tidbits as these. Getting his children’s book publisher Harper to print Different Dances—a giant-sized book of cartoons about love and sex that Silverstein pitched as “The Adventures of a Boy and His Penis”—was a pure power play. Silverstein knew Harper valued his work, given the millions of dollars his kid lit brought in, but “he wanted to find out exactly how badly they wanted to keep him on board.” So he told them that if they didn’t publish Different Dances—“exactly as it is, there can’t be any changes,” which meant including several frankly pornographic pictures—he’d take his next children’s book, A Light in the Attic, to another publisher. Harper published Dances. And while it shoved the book into the world with little fanfare, on the back flap of the dust jacket it listed all Silverstein’s other books: The Giving Tree, Lafcadio the Lion Who Shot Back, Where the Sidewalk Ends, and The Missing Piece. Given the contents of Dances, the listing, blatant acknowledgment of Silverstein’s “other” authorship, the non-porno kind, was an act of courage, back-handed though it may have been. Summing up, Rogak wrotes: “While Playboy put him on the map, the children’s books enshrined his talent forever. If he hadn’t done the children’s books, he would have been just another hustling cartoonist. His books have been translated in twenty different languages and have sold well over twenty million copies.” A central registry where songwriters can copyright their songs lists just over 800 songs by Silverstein, and, Rogak adds, “he may have completed hundreds more over his lifetime.” Typically, Silverstein didn’t write down any of his songs: only their performance secured their existence. He also wrote “well over 100 one-act plays,” a couple dozen of which are listed in the book’s appendix. A Boy Named Shel is, at the moment, Rogak’s favorite book. For a long time, she liked Death Warmed Over most, but she now favors the Silverstein tome. “It was by far the hardest book I’ve ever written because Shel wanted to squeeze as much as possible out of every second of every day, and he flung himself into the world with so much abandon that it was like writing and researching five books instead of one,” she says at her website, lisarogak.com, where she appears in a bathtub. “But at the same time, Shel was such a character, making no excuses for his behavior and creativity, that it was sheer pleasure to talk to the people who knew him and listen to their stories, because their own memories of him were still so vivid. I regret that I never met him.” We are the beneficiaries, in a manner of speaking, of her regret. We can meet the Silverstein that Rogak’s regret drove her to uncover in her book: she has enriched considerably the store of Silverstein lore, the sort of mythology that is beneficial for any creative personality to soak up in large quantities as armor against a world that is forever demanding conformity and compliance. Young and unformed minds, however, should avoid the book: it will counsel only “do it your way” over and over again, and that will make earning a living in a capitalistic society somewhat difficult. For an essay about how being a cartoonist prepared Silverstein to be a children’s book author and songwriter and playwright, you may resort to Harv’s Hindsight for April 2001. This essay, by the way, I converted to a monograph that is accompanied by Silverstein’s rare, seldom seen and never, elsewhere, reprinted 23-page “cartoon history” of Playboy, published in the magazine in the first three issues of 1964 to commemorate the 10th anniversary (32 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w). It’s available at $7, including p&h; just write me at the end of the scroll. Oh, one more thing in testimony to Rogak’s being the ideal biographer for Shel Silverstein: she drives a hearse. She says it makes it easier to haul around various musical instruments she plays. ***** BANANA REPUBLIC—HERE? US? A new collection of Kirk’s blood, sweat, tears, bile and stomach fluids—Molotov Comix Press It is in the fervent hope of finding such a work as Banana Republic that I devote so many of my waking hours to the steadfast and diligent perusal of the latest products of cartooning artistry. I was familiar with and doted on the drawings of editorial cartoonist Kirk Anderson—his bold and tapering line, a line supple as liquid sheen, not to mention the crispness of his stylistic mannerisms, the inherent drama of their composition and the superlative comedic timing of the breakdowns—but I was not prepared for the brilliance of his satire. As I turned the pages in this book, I watched as he laminated outrageous comedy onto merciless commentary, the uncompromising sort of satire that you seldom find these days except in the us-and-them world of labor cartooning wherein owners and managers are forever the bad guys and workers forever the good. (Not surprisingly, Anderson dedicates this book to the two living champions of this nearly forgotten genre, Mike Konopacki and Gary Huck, who, Anderson says, “taught me about cartooning, politics, history, and the fine art of living by one’s principles.”) Observing Anderson’s wit, his graphic genius, his satirical savagery, I laughed the silvery laughter of pure, unadulterated pleasure at beholding the symphonic beauty of his work, its visual distinction yoked to an intellectual assault on the issues of the day, a ramble engaging both eye and mind—cartooning at its most sublime. Banana

Republic (208 8x11-inch pages, b/w;

paperback, merely $15.95 plus $4.75 p&h from Molotov Comix Press,

Feign Office Building, 2nd Floor, 2064 James Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55105; or molotovcomix.com)

reprints the quarter-page newspaper comic strip Anderson did for the Minneapolis Star Tribune from October 13, 2005 to November 17, 2007. For over two years, inn

nearly 100 comic strips, Anderson unflinchingly lambasted the Bush

League and its demonstrably unAmerican policies. Here’s a

preview. As a device for satire, Anderson’s contrivance is an unabashed stealth bomber. He explains: “We Americans can’t seem to agree whether torture and imprisonment without charge are necessarily bad, if performed by well-intentioned red-blooded Americans. But if the torture and imprisonment without charge take place in a small, backwater banana republic, we have no problem agreeing that such practices are appalling, obviously unAmerican and proof of the regime’s illegitimacy. Setting the comic strip in a fictional backwater banana republic allows us to consider issues more objectively, without getting sidetracked by their American apple pie context.” To give his fictional country a cohesive satiric focus, Anderson invented the dictator, Generalissimo Wally, explaining: “Many a political discussion has been polarized by uttering the single word ‘Bush.’ Building the strip around the fictional character of Generalissimo Wally allows us to focus on the political issues, rather than getting mired in the political personalities. Generalissimo Wally may often represent the U.S. president, but on any given week, he may just as likely represent power more generally, or a corporate CEO, or the U.S. government, or Minnesota’s governor. Regardless of whether we think American torture is right or wrong, when it’s Genralissimo Wally melon-balling some poor bastard’s eyes, we know it’s appalling, unAmerican, and proof of his illegitimacy.” As the “story” unfolds over months, Anderson brings in some subordinate characters, object lessons, who become the real heroes of Banana Republic: Diego Meza, who is imprisoned and tortured for no reason either he or we are aware of, and his wife, Rita, who tries to get her husband freed, and her brother, the unfortunate Cesar Diaz, who, introduced as a jab at Walter Reed Medical Center’s inadequacies, becomes a symbol of a far more sinister byproduct of war. The military, Anderson observes, is adept at turning civilians into killing machines but not so good at turning killing machines back into civilians. Ceasar is the hilariously bitter embodiment of this shameful failure: he lost both arms in combat, and the new prosthetic limbs that the government provides are weapons, a machine gun and a bazooka. Every strip keys off the day’s news, nuances of which we may have forgotten, but Anderson’s book design helps us remember: on the page facing every strip is a box with a few sentences rehearsing the news that prompted the strip. The text in the boxes often brims with Anderson’s ire, when, for instance, he says of American foreign policy: “We will protect our vital interests—no matter whose country we find them in.” Anderson’s sarcasm drips: “America’s access to other people’s oil is euphemistically referred to as being ‘in our vital interests.’ To fight over other people’s oil is unseemly; to fight over our own vital interests is our obvious right and responsibility. When other countries fight for their ‘vital interests,’ it’s called an ‘invasion,’ or an act of ‘provocation’ or ‘terrorism,’ or simply ‘meddling’ in another country. In the name of democracy, we choose, or at least approve, the leaders of Iraq and other sovereign countries, and as the experts in democracy, it’s our responsibility to decide when to throw out their democratically elected leaders.” Hence: “Who was responsible for [fictional country name]’s chaos? In a democracy, their leaders woulda been thrown out. So to give ’em a taste of democracy, we threw their leaders out for them. And now the question is: why is it so important for us to stay? To bring stability.” In a similar vein is Anderson on General Petraeus’ report to Congress in the fall of 2007: “Petraeus’ claims are incontrovertibly confirmed by rock-solid intelligence, which is unfortunately classified and cannot be divulged.” Liberally sprinkled throughout the strips is evidence that Anderson is adroit at capturing the logic of Bush League lingo. Says a Generalissimo Wally spokesman: “You’ll soon be hearing fewer complaints about ... crime now that we’ve identified and arrested those responsible for doing the complaining.” About inadvertent civilian deaths in war zones: “Every death’s a tragedy, but these were all people who were going to die someday anyway.” Similarly: “We’re not lowering our standards: we’re relaxing them.” Another inescapably logical assertion: “I will not rest until I find out who ratted on me. It’s time people took responsibility for their actions.” The honored admonition, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” becomes “If you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours”—the conversion, alas, seems exact. Lampooning the Bush League’s penchant for injecting pro-life restrictions into every facet of government policy, when a U.S. representative shows up to pay a widow a “condolence payment” for the loss of her husband (the U.S. policy in Iraq), she has to sign a form that she won’t use the money for abortions. Momentarily concerned about whether the Amnesian puppet parliament’s rationale for its “unwarranted privacy nullification program” is legal, legislators are assured that their concerns are “unnecessary”: “The Generalissimo’s inherent executive powers as ‘dictator’ already cover illegal acts.” One strip touches, briefly, on a local university’s undermining the principles of free speech when it disinvited a speaker, who, in the opinion of the Ruling Class, might offend someone: with respect to “independent thinking,” the officials explained, the speaker was found not to be a team player. In that speaker’s place, the university invited a skinny blonde named, with typical Anderson fiendishness, “Ann Coldturd.” Wonderful. (And here, Anderson produces a caricature of his victim that is dead-on.) Anderson is perfectly attuned to the Bush League’s penchant for remaking the world in its own image through sheer lexical gymnastics. Thus, in the Banana Republic, the Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, is recast as the “Environmental Privatization Agency.” Science and thinking are passe in the Banana Republic. A friend explains to Rita Meza: “Chairman Wally is phasing out the old, impure way of thinking—you know, the so-called ‘intellectual’ approach—and replacing it with party-approved, faith-based thinking! Here—have one of the chairman’s little red books.” Rita takes the book and says, sarcastically: “One of his little-read books? What is it, the Geneva Conventions?” (A nicely revealing pun.) No, she’s told, the book collects Wally’s “faith-based quotations.” Science is to be avoided, says Rita’s friend, launching to a wonderfully convoluted piece of Bush Age rationale: “Look, this all saves taxpayer money. As information becomes more scarce, its value increases. Instead of giving it away for free, we can—” Rita offers a mild demurer: “But if public information isn’t available, it’s—” “Oh, it’s still available,” explains her friend, “—it’s just not accessible.” Wonderful some more. Although Anderson is perfectly capable of doing exquisite caricatures of public figures, he avoids such likenesses herein, using the same justification he deployed when inventing Generalissimo Wally, who doesn’t look anything like GeeDubya. His caricature of Rumsfeld looks nothing like Rumsfeld, either; but he has corks in his ears so he’ll hear no dissenting opinions: “He was born with corks in his ears, and yet, he never let his inability to hear others stand in the way of his own convictions.” When Anderson’s “Rumsfeld” speaks, we can hear actual Rumsfeldian rhythms in his utterance as well as in its logic: “This happens in all wars. Armchair idiots start second-guessing the visionary men of destiny once the corpses pile up. It’s just a phase.” The perfect pitch of Anderson’s language is beautifully orchestrated with his pictures, which use comedy to hone the satire to a sharp, cutting edge. Anderson never lets his anger—his rising gorge at the gross indecencies of the Bush League—blind him to possibilities for humor, as I point out in the samples I’ve mustered in this vicinity; you might want to print out these pages so you’ll have the images in hand as you wrestle with my comments.

The humor is often as much visual as verbal. Early on, as our fragment here demonstrates, Anderson begins using the expression “melon-balling” as the euphemism for a rude abuse, which, as shown in the pictures in the strip’s panels, clearly involves gouging out a person’s eyeballs with a spoon. Then, in an outrageous elaboration on the device, he shows poor Diego’s eyeball dangling from its socket, a continuing reminder of what “melon-balling” is. Sometimes, Anderson cannot resist leaping into slapstick: when Generalissimo Wally enters the torture chamber and sees one of his minions using a cigarette to enhance his interrogation technique, Wally is enraged because the room is supposedly a “smoke free” environment. Wally displays Bush League logic in determining whether “disembowelment lite” is torture or not. Slapstick again emerges, this time with satiric force, when Diego, contemplating the loss of his hand to a carpenter’s hand saw, screams: “Yes! No! Seven! Anything! Friday!” Seven? Friday? A hilarious revelation of the received truism that a man being tortured will say anything. The assault on reason represented in this sequence is stunning in its echoes of justifications for torture. Purely visual comedy often sharpens the satire by reason of its contrast to the grimness being depicted. Dangling by his arms and pestered with the idiotic preoccupations of his torturer, Diego “lightens the mood for his fellow detainees” by trying to swing his eyeball back into its socket—an outright imitation of a child’s game, which might even be called “ball in the socket.” In another scene in the torture chamber, Anderson resorts to a simple albeit graphically effective visual pun—showing a victim vomiting blood, about which Wally says, “He even speaks in bloodbaths.” The first panel in this fragment alludes to the election to Congress a few years ago of a Muslim, which alarmed a few of the Righteous Wing who wondered how anyone not sworn in on the Bible could be a decent public servant. Anderson’s depiction of the Blackwater debacle is high visual comedy—gangsters, cowboys, pirates, racing through town, shooting in every direction as they go. Shamefully, this picture is as much accurate as it is comedic. Little touches matter. In the opening panel of a page about Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, the U.S. attorneys allegedly “fired” for political nonconformity appear in the background as corpses, knifed and axed, littering the steps of the Justice Department. But the crime-scene yellow tape, “Do Not Cross Justice Department,” is the crucial comedic and satiric embellishment. The prosthetic armament of Cesar Diaz is a spectacular visual device that Anderson is able to exploit to great satiric advantage in several strips. But on this page, the last panel is the one that kills me: Anderson asserts that Cesar’s dilapidated jeep is being held together by those little yellow-ribbon magnets that we see fastened on vehicles everywhere. As if. The Pentagon’s self-righteousness in the face of its failure to adequately armor our troops has nowhere been more vehemently ridiculed. And on the next page, Anderson deploys again the outrageous image of Cesar trying to make his new “arms” and “hands” function in any way non-combative. Cesar fails, spectacularly, as seven tiny wordless panels reveal. And then Anderson’s satiric indictment cascades, going from the need to sign a “PTSD Disclaimer” to “you’re not a gutless, quivering pantywaist” to being flipped off (or not) to, with a staggering abdication of responsibility that is not, alas, unlike the actual VA’s bureaucratic fumbling, labeling Cesar’s affliction “a birth defect” which is not, ipso facto, covered by the VA’s policies. The last strips in which Rita finally secures the release of her tortured husband deploy breathtakingly inspired visuals. After years of relentless torture, the hapless Diego has been reduced to a liquid, as if his skeletal structure has been completely crushed, mulched. This symbol Anderson exploits for two pages as Rita tries to arouse public indignation—Diego drips from her arms as she carries his limp remains around—all to no avail. Unable to talk, Diego answers his wife’s question about what “they” have done to him with speech balloons the show images of melon-balling, brain removal, and simple beatings. Ugly stuff. But in Anderson’s hands, the ugliness is given an image so grim, so metaphorically accurate, that ugliness is transcended and becomes excruciatingly satirical. Diego, like any Tex Avery character, regains his human shape eventually, but inside, where his mind used to be, is nothing but vagaries. Last seen, he was wearing a tuxedo with a bomb belt as a cummerbund. Anderson’s book—his comic strip—makes for vastly entertaining reading. Unabashedly irreverent on every note it strikes, it withholds nothing. There are no sacred cows; no wickedness committed in the name of making the world a better place is ignored, no justification accepted. The very existence of the book—the publication in a family newspaper of the strips that comprise the volume—is a hallelujah chorus of exultation, a triumphant celebration of freedom of expression. And it is a full-throated testament to the courage of Star Tribune’s editors, Eric Ringham and Susan Albright, for giving Anderson “near-complete creative freedom.” Without the paper’s unwavering support, the creative juices that flow through this project would never have been released, we would never been illuminated by the light of the brilliance of Anderson’s satire, and the cartoonist’s considerable talent, on generous display in this volume, would have languished, untapped, unrevealed. The book is relentless as well as unflinching. It is also a supreme example of how the arts of cartooning can be assembled for telling satire, satire that is humorous as well as insightful, hilarious as well as inciteful. Further Anderson Adventures in the Past. After two years, the Banana Republic feature in the Star Tribune was discontinued by “bean counters,” Anderson tells us—that is, for financial reasons. For Anderson, it was a familiar story. Until April 2003, Anderson’s stunning stylings graced the pages of the St. Paul Pioneer Press where the cartoonist perched part-time for the preceding eight years. Then he was laid off as the tide of editoonist firings for financial reasons began its rise. The Pioneer Press, a link in the Knight-Ridder chain, was then reportedly the least profitable of the corporation’s 27 papers, and, as usual, payroll reduction was the mechanism adopted to enhance the bottom line. Reportedly, the paper was close to a 20 percent profit margin (most businesses in the U.S. would be delirious with a 15 percent profit and are usually more than happy with 10 percent), but Knight-Ridder boss Tony Ridder wanted to increase that to 25 percent. Just a couple years previously, Jay Harris, the publisher of another Knight-Ridder paper, the San Jose Mercury News, resigned over the issue of profit margins, saying the paper could not perform its mission creditably if it cut staff as much as seemed necessary to generate the profit the corporation mandated. While this announcement roiled the waters a little among professional journalists, it had, apparently, no effect upon Knight-Ridder policies. Anderson’s fate was part of a trend, but Anderson himself, roosterish under the cockscomb of his bushy crew cut, is uniquely himself. On his last day, an hour before the coffee-and-cake “Farewell Kirk” wake at the office, Anderson sent an e-mail to his cohorts. I quoted it all, with Anderson’s permission, in a column I did for The Comics Journal in May-June 2004. Here it is: “So long, everybody. Thanks for helping make it a great eight years. Today is my last day. I just want to say I feel privileged & honored to have worked at this newspaper with y’all. It’s been a great job, getting paid to piss on people’s legs three times a week. I was honored to appear in the same pages as Ruben Rosario, Nick Coleman, Kirk Lyttle, David Hanners, etc. etc. etc. We have a lot of great talent, and I was privileged to be part of a great paper. I must say a special thanks to my editors, Ron Clark and Steve Dornfeld. You allowed me the freedom to have my own voice, to say what I believed in. What a wunnerful rare opportunity, to be trusted with such a precious commodity. Thank you to the rest of my opinion page colleagues (even the ones whose opinions were always wrong), for all your help, support & companionship. I’m an introverted little wallflower curled up under a drawing table in dark corner of the seventh floor, and I wish I’d gotten to know many of you better. Because all the folks I’ve had the pleasure to work & chat with have been a lot of fun. “Getting canned sucks. But I understand that difficult business decisions must be made in difficult times, and I’m glad I’m not the one who has to make those difficult decisions. But if I was ... I’d probably cut the private service that comes in to water and dust and turn the plants in the publisher’s office before I’d cut a local cartoonist. In other words, I’d cut something only the privileged few who enter the publisher’s office see before I’d cut something 190,000 readers see. Is the position of local cartoonist really valued less than office plants? “I could’ve watered ’em, and I don’t even have a PhD in horticulture. “I hope seeing my rolling bloody head bobble down the stairs doesn’t frighten anyone; I hope it just makes you cheesed off about the mess it leaves behind. I hope job cuts don’t make anyone feel resigned to their fate and lucky merely to have a job; they should make us all fight harder for what we’ve got, and fight harder to build on it. Strong journalism doesn’t come from frightened workers. Strong journalism comes from empowered employees who believe in themselves, in their mission, and who know that their company supports and cares about them and their mission too. “I know a few folks are nervous about guild activism. I know it’s easy for me to talk, I’ve already lost my job. But I think about this the same way I thought about posting this e-mail: I don’t want to live in a world where someone’s money keeps me from talking openly. I won’t live as if my silence can be bought. My principles do not have a price. I will say what I believe. Our profession believes in the freedom of speech more than any other; our industry prides itself on protecting the right to free speech. Let us follow in that honorable tradition and speak freely, speak often, speak loudly, speak, shout, sing, laugh, knowing it’s not just what our gut calls us to do, it’s what our business’ highest principles of protecting free speech call us to do. Do it for Tony! “Our business demands openness of others, smells their dirty laundry and expects quotes on it. Were we not hypocrites, we would honorably hold ourselves to the same standard. Instead, when the media ask our publisher for facts about my departure, he responds with ‘No comment.’ When the media ask Tony Ridder about a quote of mine regarding his stewardship, he responds by trying to get the article killed. I believe our company can do better. I believe our company can better reflect our public principles. I believe our company doesn’t need to lower employee value to increase shareholder value. PEOPLE NOT PLANTS! PEOPLE NOT PLANTS!” And at the bottom, Anderson typed: IT’S BETTER TO DIE ON YOUR FEET THAN TO LIVE ON YOUR KNEES! “Oddly enough,” Anderson wrote later, “my publisher was not as enamored with my closing thoughts as the rest of the staff. So he killed the next morning’s cartoon [Anderson’s farewell gesture]. He also killed a little editor’s note on the opinion page explaining the departure of the paper’s cartoonist. So there has been, apparently will be, no mention in the paper of its editorial cartoonist leaving. Kind of hard for readers to protest a layoff if they don’t know one just happened. There apparently was a blurb on Minnesota Public Radio last Saturday, but that’s all I’m aware of. I think I’ve just burned a bridge, but the fire makes me feel warm all over.” The Press, perhaps chagrined by the fuss Anderson’s departure soon stirred up on the Internet and elsewhere, finally, a week later, published the cartoon—“small,” Anderson said, “with the letters to the editor, packaged with two brief letters and a brief editor’s note explaining I was canned for budget reasons.” Meanwhile, about 250 Press staffers signed a petition, urging Anderson’s reinstatement, and the Minnesota Newspaper Guild-Typographical Union filed a grievance over Anderson’s layoff, saying the cartoonist had seniority in the paper’s art department. The Press, however, felt Anderson was in a “category of one” and thereby dodged the seniority issue. The matter moved to arbitration with more than Anderson’s fate at stake. The Union maintained that the application of the “category of one” rationale to other staff positions could destroy any semblance of seniority practices: the paper’s only economics reporter would have seniority if classified in the general pool of reporters but no seniority if classified as an “economics reporter.” As far as I know, the arbitration hearing produced no discernable effect. Anderson, in any case, had no expectation that he’d ever return to work at the Pioneer Press. While

Anderson produced cartoons on national issues for his syndicate,

Artizans, he took particular delight in commenting in the Press on local issues. One of his cartoons in the

spring of 1999 provoked considerable excitement and protest. Only one

in four of the University of Minnesota’s basketball players was

graduating with a degree, and when reports of academic fraud appeared

(a university employee revealed that she’d produced over 400

pieces of coursework for 20 players over a five-year period),

Anderson drew a cartoon that showed black basketball players during a

game while a white man in the stands comments to the man next to him,

“Of course, we don’t let them learn to read or write.”