|

|||||

|

Opus 235 (December 22, 2008). The news, alas, is not as festive as the season: more editoonists have been fired and one newspaper, teetering on the brink of extinction, is cutting back on its comic strip section, portending an ill wind blowing our way in the future. Our longest feature this time, apart from the wake we hold for newspapers and editoonists, considers a facsimile edition of the legendary Landon Correspondence Course in Cartooning. With one eye on Xmas gifts, we review a goodly number of books and take note of the passing of Forrest J Ackerman and Bettie Page, and we present the second half of the review of Brian Walker’s Comics: The Complete Collection, easily the best buy of the season, plus a scathing review of the Punisher movie, financial news from Tokyopop and comic book stores, and the dangers of editooning in South Africa. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department: CORRECTION for Harv’s Hindsight NOUS R US Financial crisis hits Tokyopop but not, so much, comic book stores; Pulitzers for online news organizations, more casualties among editoonists, Rocky Mountain News and other newspapers on the edge of extinction, comic sections cut back, South African cartoonist fights on, Obama to be caricatured, obits for Forest J Ackerman and Bettie Page, Superman’s birthplace saved XMAS LIST: BOOKS FOR A MERRY YULE :: PART TWO John Romita, Mauldin’s Willie and Joe, Peanuts through 1970, Eats Shoots and Punctuation, Al Jaffee’s Tall, Risko caricatures, Landon Course, Baker’s drawing stupid tome, new Eisner how-to, Peter Poplaski’s Sketchbook, Alexa Kitchen’s, Graphic Shorthand by Jim Ivey, New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest instructional volume The Other History of Comics Book Second half of the review of Brian Walker’s Comics: The Complete Collection And our customary reminder: when you get to the $ubscriber/Associate Section (perusal of which is restricted to paid subscribers), don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— CORRECTION FOR HINDSIGHT: In our most recent posting to Harv’s Hindsight, we mistakenly supposed that Dick Moores had fired Bob Zschiesche because Zschiesche took too long to do the Sunday Gasoline Alley; not so, exactly. Here’s a revision to the two paragraphs in question: King had employed other assistants over the years—Sals Bostwich, probably the first according to Scancarelli; John Chase, Val Heinz, Albert Tolf, and Jack Fox, who went on to assist Ed Dodd on Mark Trail. Perhaps the most picturesque in name and career was Bob Zschiesche (pronounced “zeee-chee”), whom King hired in early 1950 to assist him and, later, Perry. But Zschiesche didn’t last long after Moores took over: Scancarelli, the present mechanic in the Alley, told me that Moores subsequently convinced King to fire Zschiesche because he, Moores, could do what Zschiesche was doing and make more money. But when Perry retired in 1975 and Moores faced the Sunday strip as well as the dailies, he hired Zschiesche again to help on the Sundays. Zschiesche had just retired after 12 years doing editorial cartoons for the Greensboro Daily News in North Carolina and was tinkering with an idea he had for a different kind of editorial cartoon that he thought he might do. Preoccupied with this aspiration, he devoted less and less time to Gasoline Alley: Moores found himself doing more and more of the Sunday strips while Zschiesche dawdled for weeks over one installment. Finally, in 1980, Moores let Zschiesche go and took on all seven days of the strip. He’d hired Scancarelli to assist on dailies the previous summer; Jim’s first daily was published December 27, 1979. Zschiesche’s last Sunday was dated April 6, 1980; Jim’s first, April 13. Zschiesche went off to pursue his new approach to editorial cartooning: he depicted ordinary citizens commenting on their concerns, but every cartoon was set in an actual locale with the people standing in front of picturesque Victorian houses or local landmarks. Calling it Our Folks, Zschiesche syndicated it himself in 1980: traveling around the country as his own salesman, he eventually signed up 38 papers. About self-syndication, Zschiesche said: “I wouldn’t recommend it. It’s a crapshoot—but it’s great fun.” He ended the feature after a short run and retired, again, to the family farm near Prophetstown, Illinois. But he couldn’t stop cartooning. He did a comic strip with anthropomorphic farm animals for the local paper; that was its entire client list, but Bob was happy drawing the strip regardless of its circulation. He also tried his hand at a strip about teenagers, samples of which he showed me at the time; it was like just about any strip about teenagers you might name. Bob was, by then, too shy and self-effacing to try to sell it. He died a short time later. He deployed a crisp fustian drawing style with great eye-appeal; I wish Our Folks had made it big and lasted a long time. NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits Tokyopop Associate Publisher Marco Pavia, explaining recent layoffs to Icv2.com, said: "Publishers and booksellers are describing this as one of the worst retailing environments in memory and I don't know what to add. I think that's an accurate assessment. We're adjusting to this landscape that's shifting every day. We need to be as responsive as we can to these new realities just to endure." Being responsive in a self-preservation sort of mode, Tokyopop laid off another eight employees in early December, making 47 since last summer. Pavia's description of the market conditions in the book trade follows the similar remarks by the CEOs of Barnes & Noble and Hastings. But, Icv2.com added in another December 18 report, the numbers from comic stores are "holding up really well" in the economic crisis, quoting Diamond Comic Distributors Vice President Sales and Marketing Roger Fletcher: "Diamond's sales are tracking close to last year’s levels, but down about 3%. Retailers are trying to be prudent and conservative on inventory," Fletcher explained. "That's led to some sales declines." Fletcher thought January orders might be down because that’s a time that retailers traditionally decide to close their stores, if they’re going to. But store counts dropped only 2.5% from last year, Fletcher said. Editor

& Publisher reminds us that the medium’s

longest running continuously published panel cartoon celebrated its

ninetieth anniversary on December 19, when, in 1918, a sports

cartoonist at the New York Globe filled his space with “Dubious Athletic Achievements.” It

was popular enough to prompt repetition, and when it went beyond

sports oddities, it was re-christened “Believe It Or Not.”

Robert Ripley’s story is regaled in the third of Harv’s

Hindsights long ago and far away in May

2000 (or was it 1999?). In a press release, the Pulitzer Prize cabal announced its decision to let Internet news operations compete for the Prize, but the Board emphasized that all the material entered—whether online or in print—must come from U.S. news organizations that publish at least weekly and are "primarily dedicated to original news reporting and coverage of ongoing stories," and "adhere to the highest journalistic principles.” That, I assume, leaves out bloggers like the HuffingtonPost but it may include online animated editorial cartoons just as it does certain kinds of other video although two kinds of news photography remain restricted to stills. Starting December 8, Patrick McDonnell’s strip, Mutts, featured its canine and feline characters, Earl and Mooch, discussing the Obama family’s hope to adopt a dog from an animal shelter. McDonnell, who has served on the board of directors of the National Humane Society since 2000, is a major advocate for animal adoption and, according to Icv2.com, hopes the week’s storyline will spur even more interest in animal adoptions. The cartoonist has received several awards for his efforts, which include, twice a year, a special “shelter series” in the strip and, most recently, the publication of a hundred of these strips in an Andrews McMeel volume, Shelter Stories: Love Guaranteed. Among the strips are photos of 70 dogs that have found homes through adoption. Among the few things about Hefland that we failed to mention last time in our exhaustive profile of Mr. Playboy’s publishing career and lifestyle is Christie Hefner, the founder’s 56-year-old daughter who, with her father’s encouragement, insinuated herself into the Playboy business in 1975 and, by 1988, was CEO and chairman—all of which might have proved, were we so disposed, that there’s more to Playboy than barenekidwimmin. Cartoons about rapacious hedonists of both sexes, for instance. But the daughter has had enough: she’s retiring from the company in January to devote more time to public service of a somewhat different albeit unspecified sort, saith Bloomberg News. “I’ve long planned to spend part of my life doing things other than corporate life,” Ms. Hefner explained cryptically. Perhaps her departure was inspired by Playboy’s loss of $52 million in the third quarter, brought on, like the kindred calamities we see on all sides these days, by the recession-induced drop in ad revenue at the magazine. Until a replacement for Ms. Hefner can be dragooned into duty, the interim chairman will be a member of the board since 2002, Jerome Kern. Not the long-deceased composer, this Kern, a resident of Castle Pines, Colorado, is a philanthropist who has served previously as a trustee board member for the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and has chaired numerous charity events in Denver. Playboy Enterprises evidently qualifies as a philanthropic endeavor. ***** Merry Christmas. Two more editorial cartoonists received unwelcomed Christmas presents from their employers: after narrowly escaping layoff in April, Eric Deverick departed the Seattle Times on December 12, and Brian Duffy was laid off at Gannett’s Des Moines Register where he’s been since 1983. Deverick, says Allan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com, is going into another line of work altogether—designing clothing for a skateboard company and, moving to Southern California, joining an industrial design company as a business development specialist. He isn’t planning on doing any more editorial cartooning. Duffy’s departure leaves the Des Moines Register with a big hole on its front page. Once home to the legendary Jay Norword “Ding” Darling, the Register is the only daily newspaper in the country that still publishes its editorial cartoon on the front page, where all newspapers once ran their staff cartoonist’s opinion. Duffy didn’t leave quietly. Interviewed by local tv channels, he didn’t mince words describing his feelings about Gannett: “Whatever I gave to Gannett—and I gave everything I had for 25 years and never missed a deadline—whatever I gave wasn’t reciprocated,” he said. “How did I find out? That’s the stunner,” Duffy said. “It hit me like a ton of bricks—there’s no other way to say it.” And then the crowning blow: after he was told he was fired—there was no warning, he said—he was escorted from the building without being able to gather personal items from his office. “We’ll have somebody bring your bag and coat down,” he said he was told. Although syndicated to 400 papers by the Register syndicate, he vowed never to let the newspaper publish any of his cartoons again. And he cancelled his subscription to the paper. A video of one of his tv interviews is available at the E&P website, editorandpublisher.com and here, http://www.politicker.com/video-former-des-moines-register-cartoonist-speaks-out from fellow editoonist Robert Tornoe, Politicker.com’s cartoonist, who, annoyingly, was just laid off there after serving full-time since just last April. These casualties drop the total number of full-time staff editoonists to 88. Down from 101 last May, a spectacularly precipitous decline. One of the charter members of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC), Jim Ivey, who drew editorial cartoons for 40 years from coast to coast, Washington D.C. to San Francisco, tells me the number of editoonists in 1948 when he started was 125. My speculation is that it went up somewhat over the years before beginning its sharp decline in the last decade or so. The

early warning signal has gone up in Minneapolis at the Star

Tribune, which is hoping to whittle its staff

with buyouts and has listed the staff editorial cartoonist position

as “eligible.” Since the paper has only one staff

editorial cartoonist, Steve Sack, he may be counting the months until

his job disappears. ***** More Festivities. Another Christmas gift of the dire sort threatens yet another editorial cartooning slot: on December 4, E.W. Scripps, owner of the Rocky Mountain News, announced that it is putting the 150-year-old tabloid up for sale, and if a buyer doesn’t come forward by mid-January, Scripps may close the paper, by circulation, the chain’s flagship. The News (which is what we called it when I was a kid hereabouts, not today’s slangy locker room locution, “the Rocky,” which it prefers to be called these days) is losing about $15 million a year, and even if some idealistic billionaire with journalistic stars in his eyes would be interested in acquiring the paper as a hobby, financing a buy in this credit-crunched economy would be extremely difficult. When the News folds, Ed Stein’s editorial cartooning job will disappear, too—as will the position of one of the nation’s last two full-time sports cartoonist, Drew Litton. (The other remaining full-time sports cartoonist is Bill Gallo at the New York Daily News.) The situation abounds in ironies. Denver is one of the nation’s last two-newspaper towns thanks in part to the 1970 Newspaper Preservation Act, which created the possibility for joint operating agreements that would, it was hoped, preserve two independent editorial voices in cities where at least two newspapers existed, each threatening the other’s financial well-being. Most JOAs maintain two newspapers as separate news and editorial entities but consolidate business operations under one staff, thereby achieving a savings that presumably is enough to enable both journalistic enterprises to continue. The first irony: of the 27 JOAs approved since the law was enacted, 16 have failed. The Newspaper Preservation Act is not preserving newspapers. In 16 instances, the savings effected by the consolidations was not sufficient to keep both papers alive. Ditto in Denver. The Denver JOA went into effect in January 2001 with the business operation being handled by a third entity, the Denver News Agency, jointly owned by the two newspapers, the News and the Denver Post, which split the profits from the DNA. Due to massive decline in ad revenues, the News’ share of 2008's profits will be $15 million short of covering operating costs. Second irony: the circulation of the News is slightly greater than that of the Post, but because of its smaller page size, the News’s advertising income is less than the Post’s. Third irony: so the News is responsible for there being even less revenue in the Post’s share than the Post might generate on its own. The Rocky Mountain News, which published its first issue April 22, 1859—20 minutes before the first issue of a rival paper (which never published a second issue)—is Colorado’s oldest newspaper and the oldest continually operating business in the state. Fourth irony: a month ago, the News launched an ambitious anniversary celebration, planning to publish every day for the next 150 days, until April 23, 2008, an article about a major newsstory from the past, illustrated by the changing face of the newspaper’s front page. Chances are, the culmination of the celebration planned for April 2008 will not take place. Scripps, which owns 14 other newspapers around the country, is merciless in shoring up its profit margin: it shut down another of its papers, the Albuquerque Tribune last February; the Tribune was in the nation’s oldest JOA with the Albuquerque Journal. The year before, Scripps shuttered the Cincinnati Post, which was in a JOA with Gannett’s Cincinnati Enquirer, an arrangement Gannett announced it would not renew. If Scripps were a journalistic enterprise rather than the manager of “profit centers,” its papers would all survive. But that’s old fashioned journalism. John Morton, a veteran newspaper analyst, is quoted in the Denver Post, estimating that more than 30 daily newspapers are for sale at present. The New York Times at its website on Friday, December 5, reported that the Miami Herald is for sale, but no one knows of any serious offer yet. The largest of the McClatchy chain, the Herald “generates a very slim operating margin ... the most attractive part of any deal could be its prime waterfront real estate. But the Florida real estate market is in deep recession—one of the reasons for the struggles of the paper, which used to benefit from heavy real estate advertising.” On Pearl Harbor Day, the New York Times reported that the Tribune Company, owner of the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times, might be filing for bankruptcy because its cash flow is less than is specified in an agreement with bondholders. The next day, the Tribune filed for bankruptcy protection. Last December, the Tribune Company “went private” (i.e., shed its stockholders) when a real estate billionaire, Samuel Zell, “bought” the company in a move widely heralded as the first in what newspaper watchers hoped would be a wave of private investor purchases across the industry, restoring newspapers to private owners instead of Wall Street investors, which, it was expected, would lead to the reinstatement of journalism as the chief mission of the newspapers. In Zell’s case, it hasn’t happened: he may know about investments (although maybe not so much about purchasing newspapers) but he proved ignorant of journalism. In financial straits similar to the Tribune’s are the companies that own the Inquirer and the Daily News in Philadelphia; ditto the Star Tribune in Minneapolis. Even the New York Times is hard up for cash and is hoping to score a huge loan. In most of these cases, the newspapers are actually making money, but not enough to make adequate payments on their debts. Part of the problem with the Rocky Mountain News is that it has $130 million in debt incurred by installing new printing equipment a year or so ago. Cited in the Denver Post, the corporate ratings agency Fitch “predicted that some newspapers and newspaper groups are likely to default on their debt in 2009—possibly leaving some cities with no daily newspapers.” And

in Detroit, the JOA’d Detroit News and Detroit Free Press (the 20th largest U.S. newspaper by weekday circulation) have taken a giant

stride in that direction. The papers announced that they will drop

home delivery of their print editions except for the three highest

revenue days, Thursday, Friday and Sunday. On the other days of the

week, “newspaper readers” can find the news on the

papers’ websites. “More and more outlets will be moving

this way,” R&R correspondent John McCarthy speculates. “It

will affect our cartoonist friends directly. Quite apart from our concern over the fate of a democratic form of government in a society of people ignorant of what’s going on in their world, we also wonder about the fate of comic strips. A trivial consideration, I realize; but this niche is about cartooning in all its print venues. Hence, our interest in the future of newspaper journalism. An interest suddenly turned to anxiety: the Times-Union in Jacksonville, Florida, announced on December 14 that it intends to drop eight comic strips daily and Sunday. Said Jeff Reece: “Financial realities are forcing us to make some difficult and unpopular decisions. The next step might be the hardest—and least popular— of all the adjustments we have had to make: cutting comic strips. ... The comics page is known as the third rail of the newspaper industry,” Reece continued. “No editor in his right mind will touch the comics unless it is absolutely necessary. We don't want to make our readers unhappy. But economic realities make this necessary.” What are the economics? Figuring that the average comic strip costs a newspaper $15 a week for dailies, ditto for Sundays, a newspaper can cut expenses by $1,560 a year if it drops one syndicated strip from its line-up. And if the Times-Union drops eight strips, that’s $12,48 a year in savings. In actuality, the savings will be greater: probably some of the eight strips will be the more popular ones with fees higher than our average $15/week/Sunday. “Eliminating eight comics brings the kind of savings we needed,” said Reece. “It’s painful but necessary.” The paper will give its readers a chance to vote on a list that’s made up of more than a dozen strips, some of which finished in the bottom half of a recent readership survey and a couple of which, newly added to the line-up, received “an unusual amount of criticism from readers.” Another strip that’s a candidate for dropping is For Better or For Worse, a candidate because, Reece said, “it’s essentially in re-runs.” Reece doesn’t think any of the eight strips will ever return once they’ve been dropped. There you have it: my worst nightmare looming on the southeaster edge of the continent. Before long, other papers will surely follow suit: after firing a superfluous editoonist, trimming the comic strip line-up to the bone is the next best way to save money. One of the Times-Union readers, responding to Reece’s announcement, said it best: “Obviously, no one at the T-U gives a shit about their own comics survey or their own web site. Pathetic. Let the paper die. It’s no wonder.” Extreme, maybe, but not far from my own sentiment. Newspapers

all across the land are facing severe financial losses as the economy

tanks, exacerbating the other rolling calamities that continue to

batter the industry—loss of advertising income, particularly

classified, declining circulation, falling stock value, and the

competition from the Internet. Much of the catastrophe is very nearly

phoney: as we’ve observed here before—and as Paul

Oberjuerge observes in a long piece at oberjuerge.com/?p=552 The financial plight of newspapers generally is not determined by their balance sheets so much as by investors that own stock in the newspaper businesses who want higher profits. Since newspapers cannot generate more income—falling circulation and declining ad revenue preclude that—they do the only thing that remains: they reduce costs, thereby jacking up the difference between income and expense, creating more profit. The most conspicuous expense any paper has after the cost of newsprint is its payroll, and so newspapers have, for several years now, cut costs by firing staff. And editorial cartoonists, who are quickly perceived as superfluous in a field that supplies syndicated editoons at a fraction of the cost of salary and benefits for a staff cartoonist, are among the first to go. This grim circumstance has become suddenly grimmer as the economy dives for the depths. Nationwide, advertising revenue dropped only 7% in 2007, but in the third quarter of this year, the quarter ending in September when big banks and investment houses began to fail, the plunge reached 18%. The most irreplaceable losses have occurred in classified advertising with CraigsList dislodging daily journalism’s most dependable source of income: advertising used to account for about four-fifths of a newspaper’s revenue, and at large city newspapers, classifieds were half of that. At the Rocky Mountain News over the weekend following the shattering announcement of its impending dissolution, hope revived at the report that a Montana media company, owned by Shawn White Wolf, wants to buy the paper—if he can muster enough investors in this sinking economy. I hope he can pull it off: the News’ comic strip lineup is far superior to the Post’s. Meanwhile, the Post is scarcely home free: on December 13, Post publisher Dean Singleton asked the paper’s unions to re-negotiate their labor contracts immediately, seeking to slash $20 million in expenses. Singleton’s request, reported by Jeff Smith at the Rocky Mountain News, “comes a day after Moody’s Investors Services said his MediaNews Group [owner of the Post] faces an increased risk of defaulting on its loans.” ***** Editoonist Scott Bateman, who, we reported, just lost his gig doing daily animation at Salon.com, is back, albeit with a weekly, not a daily, animation. He speculated that this unexpected turn of events was brought about because his cartoons generated traffic at the website, adding that Salon, unlike HuffingtonPost, pays him. He now has more spare time, which he is investing in creating an animated feature film in Flash. He’s not the first to make a feature film in Flash, he says, deferring to the pioneering Nina Paley, who produced “Sita Sings the Blues,” which has won several distinguished awards. She may at last have found her niche: she’s made at least one syndication attempt that failed; maybe two. Her comics for alternative newspapers did fairly well, but she couldn’t achieve success with more mainstream efforts. You can see a tantalizing teaser of Paley’s film at sitasingstheblues.com, a scintillating visual treat. Bateman’s work on his film can be viewed at atomagevampikre.org; his animated cartoons at batemanimation.com. HANKY PANKY IN SOUTH AFRICA SOME MORE Zapiro’s educational campaign in South Africa has spread from newspapers into schools. Zapiro, the pen-name of editorial cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro, has for some time been pointing a loaded pen at the president of the African National Congress, Jacob Zuma, accusing that worthy of venality and stupidity. A year or so ago, Zuma was accused of raping a woman who turned out to be HIV positive. During the trial, Zuma explained, among other things, that he had guarded against contracting HIV by taking a shower after he’d had sex with the woman. Thereafter, Zapiro invariably portrayed Zuma with a shower faucet coming out of his forehead, a visual reminder to readers of Zuma’s cupidity and ignorance. Zuma, who is expected to become the next president of South Africa after elections early next year, was found not guilty of rape by the Johannesburg High Court, and he has brought suit against Zapiro, claiming the cartoonist is defaming his character. But Zuma fumes against Zapiro in vain: the cartoonist persists. And now, reports Bongani Mthembu in Weekend Witness, he’s infiltrated the formal educational system with his incendiary crusade. Parts of an examination paper for Empangeni High School eleventh grade students are based on one of Zapiro’s cartoons, one of those for which Zuma is suing the cartoonist. Entitled “The Jacob Zuma Moral Degeneration Handbook,” the cartoon, referring to Zuma's rape trial, offers rules such as: "A short skirt means she is asking for it”; "No" means "Give it to me big boy!"; "When having casual sex, always apologize for not having a condom"; "After casual unprotected sex permanently remove conscience before then sleeping with your life partner(s).” Under the second section, titled "Leadership,” one of the points is: "Being Deputy President means—babes and backhanders." Zuma is pictured several times, once with his pants down around his ankles and once with him ogling a scantily clad woman. According to a Cape Argus article, students taking the test are given a series of questions based on the cartoon and another newspaper editorial that likens the behaviour of Zuma supporters at his rape trial to that of Neanderthals. Zuma supporters have objected strenuously to the cartoon, saying it “wrongly presents the ANC president as a rapist, [male] chauvinist and lacking moral fibre. This is in spite of the fact that the ANC president was cleared of rape charges by a competent court of law and his undying fight against women abuse and moral decay in the society.” Parents of the students have also complained, and the Education Department has launched an investigation of the teacher who devised the exam. Ironically, Zapiro was at one time a staunch supporter of the ANC. After serving in the South African army, he became politically active and deployed his art to promote Nelson Mandela’s then-banned African National Congress party and other anti-apartheid groups. But these days, not even Mandela escapes Zapiro’s scrutiny. The Associated Press reports that a recent exhibit of the cartoons includes many that show the anti-apartheid icon as strong, enduring and almost saintly, but a few ridicule his foibles and missteps, most notably when Mandela accepted an award from former Indonesian dictator Suharto. The famed national liberator is depicted in another cartoon with his halo askew because of a domestic policy gaffe, calling for fourteen-year-olds to have the vote. But Zapiro is still in awe of Mandela’s achievements. "Mandela embodies the greatest things that came out of the struggle (against apartheid) and since democracy," said Shapiro. "It is this spirit I have tried to tap into,” adding: “It's fantastic to have the opportunity as a cartoonist, as a satirist, to criticize an icon like Mandela and know that he understands that criticism. He has said he is not a saint, and I felt I had to be critical of him. I owed it to myself and to him.” Early in his cartooning struggle against apartheid, Zapiro was arrested and jailed. In prison, he did a drawing of what he thought Mandela looked like. Pictures of the imprisoned Mandela had been banned for decades, and so few people saw him until he was released in 1990. "I

have been influenced and driven by him," Shapiro said. "It

has been a strange and wonderful relationship—mostly praising

him and occasionally sniping at him from the sidelines. Increasingly,

he became the conscience of the nation.” SEASONAL CHEER A Rancid Raves Gallery After all that grimness, a little levity might be in order. Herewith, a Yuletide display consisting of some Santas by Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman, the great 19th century humor magazine cartooner, and, as a final fillip, one page of Elena Steier’s Gothy Gritting, a vivid reminder of her Goth Scouts comic strip creation, which, among other things, you can find at striporama.com.

And

before we stray too far afield from the electoral violence of last

month, here’s The New Yorker cover for November 17, a thing of pristine nocturnal beauty (somewhat

defaced, here, by where the address label once was at the lower

left). And, finally, in remembrance of those Lost Days of Yesteryear during which, at this time of year, we, the adolescent males at any rate, looked forward to the annual deluge of calendars with their calendar girls, here’s a page of Russell Patterson beauties, a rare find. ***** OBAMA CARICATURED When at the HuffingtonPost, Diane Tucker talked to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s editooner Mike Luckovich about Obama, she began by asking him whether it was easy or difficult to draw a caricature of “No Drama Obama.” “At

this point it's hard because for eight years we've had George W.

Bush, a president who doesn't like dissension, who's sort of

arrogant, and who feels God is talking through him,” Luckovich

said. “Obama seems like a completely different personality.

That's good news for the country, When

she wondered about the size of Bush’s ears, Luckovich said: “I

don't draw Bush as a human being any more. He's become a cartoon

character who also has a beak-like nose and circles for feet—just

two simple black circles. I draw Bush smaller and smaller as

his incompetence grows larger and larger. And as long as Obama does

well, he'll maintain his current height in cartoons. But this brings

up another problem. Obama moves in such a “Whether you agree with a president or not,” he continued, “the longer they're out there, the more likely it is you'll have a cynical view of them. I'm worried about Obama, though, because the more I see him, the more I like him. For me, that's scary.” If Obama becomes unpopular, Luckovich said he’d make his ears bigger and more rounded, “like the ears on a Mickey Mouse hat. I'd make his neck really skinny, so he has a lot of shirt collar left over to fill, and I'd furrow his eyebrows to make him look bewildered. Finally, I'd deepen the nasolabial folds on his face, so it looks like he's aging rapidly.” But if Obama “comes up with a great economic stimulus package and everyone gets back to work, I promise to draw him with black hair even though his real hair is turning gray.” PASSIN’ THROUGH The Brazen Beauty and the Monster Connoiseur First, the Monster Man. Forrest J Ackerman, writer-editor who coined the term 'sci-fi’ died of heart failure at 92 on December 4. Forrey, who, said Dennis McLellan at the Los Angeles Times, “influenced a generation of young horror movie fans with his Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, spent a lifetime amassing what has been called the world's largest personal collection of science fiction and fantasy memorabilia.” The photo-laden magazine, printed on cheap newsprint and launched in 1958, was the first movie monster magazine. Targeted chiefly “to late pre-adolescents and young teenagers, Famous Monsters featured synopses of horror films, interviews with actors such as Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi and Vincent Price, and articles on makeup and special effects.” As editor, Ackerman wrote most of the articles, which reflected his persistent penchant for puns with feature departments such as “The Printed Weird" and "Fang Mail." Ackerman referred to himself as Dr. Acula. Ackerman became a celebrity in his own right, once signing 10,000 autographs during a three-day monster movie convention in New York City. For

years, Ackerman housed his enormous cache of some 300,000

items—books, movie stills, posters, paintings, movie props,

masks and assorted memorabilia—in his18-room home in Los Feliz.

Dubbed the Ackermansion, “the jam-packed repository included

everything from a Dracula cape worn by Lugosi to Mr. Spock's pointy

ears; and from Lon Chaney Sr.'s makeup kit to the paper plate flying

saucer used by director Ed Wood in ‘Plan 9 From Outer Space.’

The Dracula/Frankenstein room featured a casket as a ‘coffin

table’ and the cape Lugosi wore in the stage version of

‘Dracula.’ A case displayed one of the horror film

legend's bow ties, which, Ackerman In 1954, the affable Ackerman coined the term that became part of the popular lexicon—a term said to make some science fiction fans cringe. "My wife and I were listening to the radio, and when someone said 'hi-fi' the word 'sci-fi' suddenly hit me," Ackerman explained to The Times in 1982. But the life-long punster wouldn’t stop with that simple anecdote: "If my interest had been soap operas,” he continued, “I guess it would have been 'cry-fi,' or James Bond, 'spy-fi.' " (Cringing fans preferred “sf” for “science fiction.”) Ackerman wrote more than 2,000 articles and short stories for magazines and anthologies, sometimes under his pseudonyms Dr. Acula, Weaver Wright and Claire Voyant. He also wrote what has been reported to have been the first lesbian science-fiction story ever published, "World of Loneliness." And under the pen name Laurajean Ermayne, he wrote lesbian romances in the late 1940s for the lesbian magazine Vice Versa. Famous

Monsters of Filmland ceased publication in

1983. It was revived briefly a decade later, but Ackerman lost

control of it. He made numerous appearances at the San Diego Comic

Con, due mostly to Con Founder Shel Dorf’s affectionate and

insistent invitations. Over the years, Ackerman slowly sold off

pieces of his massive collection, and in 2002, plagued by health

problems and legal fees, he put up “all but about 100 of his

favorite objects for sale,” McLellan reported. “The same

year, he moved out of the Ackermansion and into a bungalow in the

flats of Los Feliz.” He called it the Acker Mini-Mansion, and

“he continued to make what was left of his collection available

for viewing by fans on Saturday mornings.” ***** Brazen Beauty in a Bikini Robert D. McFadden at the New York Times did the best all-around obit on Bettie Page, so I’m using it here, almost verbatim, with sections in italic either supplied by me or poached from other obits (as credited). Here we go: Bettie Page, a legendary pinup girl whose photographs in the nude, in bondage and in naughty-but-nice poses appeared in men's magazines and private stashes across America in the 1950s ... died December 11 in Los Angeles. She was 85. Bettie, whose popularity underwent a cult-like revival in the last 20 years, had been hospitalized for three weeks with pneumonia and was about to be released December 2 when she suffered a heart attack, said her agent, Mark Roesler, of CMG Worldwide. She was transferred in a coma to Kindred Hospital, where she died. In

her trademark raven bangs, spike heels and killer curves, Bettie was

the most famous pinup girl of the post-World War II era, a centerfold

on a million locker doors and garage walls. Rivaling

the popularity of blonde beauties Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield,

dark-tressed Bettie stood out among others of her breed for reasons

other than hair color. What Bettie had that none of the others had

was a radiant, shameless meta-watt smile—that, and, often, a

lascivious albeit laughing wink. Or, if she wasn’t winking, she

seemed just about to. I was always more of a votary of the more

zaftig Diane Webber (aka Marguerite Empey), but Bettie’s sunny

visage proclaimed the essential innocence of her attitude towards

feminine nudity and sexuality. Her guileless grin announced that

sexuality was fun, and if it was fun, it had to be altogether

wholesome, an attitude she seemed beckoning us all to share, and I

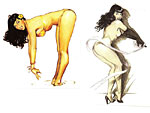

happily joined in the frolic. Here, from artist Jim Silke, one of the

best interpreters of Bettie, is one of his best: she’s not

winking here, but she’s about to. In 1957, at the height of her fame, Bettie disappeared, and for three decades her private life — two failed marriages, a fight against poverty and mental illness, resurrection as a born-again Christian, years of seclusion in Southern California — was a mystery to all but a few close friends. Then in the late 1980s and early '90s, she was rediscovered and a Bettie Page renaissance began, thanks to the late David Stevens, creator of the comic-book and later movie character the Rocketeer, who immortalized her as the Rocketeer's girlfriend. Fashion designers then revived her look. Uma Thurman, in bangs, reincarnated Bettie in Quentin Tarantino's "Pulp Fiction," and Demi Moore, Madonna and others appeared in Page-like photos. There were Bettie Page playing cards, lunch boxes, action figures, T-shirts and beach towels. Her saucy images went up in nightclubs. Bettie Page fan clubs sprang up. Look-alike contests, featuring leather-and-lace and kitten-with-a-whip Betties, were organized. Hundreds of Web sites appeared, including her own, which had 588 million hits in five years, CMG Worldwide said in 2006. Biographies were published, including her authorized version, Bettie Page: The Life of a Pin-Up Legend (General Publishing Group) which appeared in 1996. It was written by Karen Essex and James L. Swanson. A movie, "The Notorious Bettie Page," starring Gretchen Mol as Bettie and directed by Mary Harron for Picturehouse and HBO Films, was released in 2006, adapted from The Real Bettie Page, by Richard Foster. Bettie May Page was born in Jackson, Tenn., the eldest girl of Roy and Edna Page's six children. The father, an auto mechanic, molested all three of his daughters, Bettie said years later, and was jailed for stealing cars and divorced by his wife when Bettie was 10. She and some of her siblings were placed for a time in an orphanage. She attended high school in Nashville, and was almost a straight-A student, graduating second in her class. She graduated from Peabody College, a part of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, but a teaching career was brief. "I couldn't control my students, especially the boys," she said. She tried secretarial work, married Billy Neal in 1943 and moved to San Francisco, where she modeled fur coats for a few years. She divorced Neal in 1947, moved to New York and enrolled in acting classes. She

had a few stage and television appearances, but it was a chance

meeting that changed her life. On the beach at Coney Island in 1950,

she met Jerry Tibbs, a police officer and photographer, who assembled

her first pinup portfolio and introduced her

to amateur camera clubs, whose members made her an underground

sensation, according to Joe Holley and Matt Schudel at the Washington Post. By 1951, the brother-sister photographers Irving and

Paula Klaw, who ran a mail-order business in fetish cheesecake, were

promoting the Bettie Page image with spike heels and whips. Her

pictures were ogled in Wink, Eyeful, Titter,

Beauty Parade and other such cheap cheesecake

magazines, and in leather-fetish 8- and 16-millimeter films. Her

first name was often misspelled “Betty.” Her

most famous photo shoot, according to Holley and Schudel, was taken

by fashion photographer Bunny Yeager, who portrayed Bettie lounging

with leopards and frolicking in the nude on a florida beach. Her big break came when one of Yeager’s photos was used for the Playboy centerfold in

January 1955, where she winked in a Santa Claus cap as she put a bulb

on a Christmas tree. Money and offers rolled in. Then in 1955, she received a summons from a Senate committee headed by Senator Estes Kefauver, a Tennessee Democrat, that was investigating pornography. She was never compelled to testify, but the uproar and other pressures drove her to quit modeling two years later. She moved to Florida. Subsequent marriages to Armond Walterson and Harry Lear ended in divorce, and there were no children. She moved to California in 1978. For years Bettie lived on Social Security benefits. After a nervous breakdown, she was arrested for an attack on a landlady, but was found not guilty by reason of insanity and sent to a California mental institution. She emerged years later as a born-again Christian, immersing herself in Bible studies and serving as an adviser to the Billy Graham Crusade. In recent years, she had lived in Southern California on the proceeds of her revival. Her signed photographs went for hundreds of dollars, reported Holley and Schudel. Occasionally, she gave interviews in her gentle Southern drawl, but largely stayed out of the public eye — and steadfastly refused to be photographed. "I want to be remembered as I was when I was young and in my golden times," she told the Los Angeles Times in 2006. "I want to be remembered as a woman who changed people's perspectives concerning nudity in its natural form." Being photographed in the nude didn’t bother Bettie at first. But “when I turned my life over to the Lord Jesus, I was ashamed of having posed in the nude,” she told Playboy last year, according to Holley and Schudel. “But now, most of the money I’ve got is because I posed in the nude. So I’m not ashamed of it now. But I don’t understand it.” On other occasions, Bettie said of her barenekid self: “God approves of nudity. Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden were as naked as jaybirds.” Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. It’s a comfort in these parlous times to find that the world goes on, despite economic collapses and Presidential Elections, in exactly the absurd and baffling way that it has gone on for several decades now. To remind myself of this eternal verity, I occasionally buy a copy of the Sun Weekly World News or the Globe, each an example of the more deliberate of the investigative tabloids available in racks near the check-out counters of grocery stores throughout the known universe. The Sun caught my eye the first week of December: “Two-headed Bigfoot Shot by Iowa Cop” the headline explained. And there was a photograph of two shaggy, bearded humanoid faces. Inside, we find the story, with more fact-proclaiming photographs, including one showing a recumbent Bigfoot, dead no doubt, at the feet of a pistol-wielding cop in dark glasses. So the story must be true: photographs don’t lie. The corpse’s feet didn’t seem to be particularly large even though, lying on its back with its feet towards us, foreshortening probably exaggerated their size. The creature was covered all over with hair, including where its genitals would be if it had any. The caption tells us that “victim was the second two-headed Bigfoot to be shot by cops in the past four years” near Jesup, Iowa. Jesup is a little town of 2,121 souls just east of Waterloo, Iowa, which I used to drive through a couple times a year on the way to my wife’s parents home, where we often spent Christmas. But I never saw a Bigfoot. And if there were ever any around, I’d have seen one: according to a side-bar in the story, “Scientists have determined that the average male Bigfoot stands 8 feet 2.25 inches tall and weighs 487 pounds; females tend to be 6 inches shorter and 50 pounds lighter.” You can’t miss seeing an 8-foot 500-pound creature even if its lurking surreptitiously. But, as I say, I never even so much as saw one in the distance during my many travels near Waterloo. Across the top of the two-page spread, another photograph shows an Iowa corn field, and in the foreground is the Bigfoot, striding along. It’s somewhat blurred, as if the photographer moved the camera, so the two heads could actually be one that only appears to be two because the camera moved. But the policeman’s testimony cinches the deal. (His name is being withheld pending the results of an investigation into the incident.) He drew his weapon and ordered the Bigfoot to put his hands up, without much luck. “He must have heard me because he whipped around and started howling like he was a creature straight out of Hell,” the officer testified. “My first thought was he was a door-to-door campaigner for Barack Obama—that in itself is enough to get anyone shot in these parts. At the same time, I thought he could be a burglar, taking advantage of all those trick-or-treating kids out there to get into people’s homes.” It was Hallowe’en night, perhaps a hint about the authenticity of this episode. The cop continued: “I didn’t know whether to shoot or ask questions. I decided to let him have it, just in case. After all, I reasoned, what’s the worst that could happen? If I’m wrong, I shot a Democrat. What’s the big deal?” Okay: that’s it. We’ve been had, photographs or not. So I don’t know whether to believe another story in the paper about the celebrations held on Election Night in Obama, Japan. Obama, it means “little beach,” is a seaside resort town, and the townspeople, we are assured, jammed the streets, celebrating and being entertained by “the Obama Girls, a troupe of hula dancers founded in honor of Barack Obama’s Hawaiian birthplace.” I was okay with this until I got to the Obama Girls. Does Michelle know about this? BREAKING THE BANK AT 10622 KIMBERLY AVENUE Here’s Ed Black’s photograph of Hattie and Jefferson Gray’s house on Kimberly Avenue in Glenville, a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. The Grays have lived here for 20 years, but the house achieved historic significance because of an earlier resident who lived there a much shorter time. It was here one hot summer night in 1933 that Jerry Siegel, lying awake in his sweltering bedroom, conceived the notion of a strongman named Superman. The next morning, he ran down the block, around the corner, and up the next street to the house where his artist friend, Joe Shuster, lived, and the two of them concocted the appearance of the Man of Steel. The Grays have tolerated numerous unannounced visits over the years by Superman fans, and they even commemorated the history of the place by painting it the colors of Superman’s uniform: the colors don’t show too brightly here in the photo, but they’re blue and red and sometimes yellow. Last winter, Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter Michael Sangiacomo, contemplating the 70th anniversary of Superman’s first comic book appearance in Action Comics No. 1, July 1938, started asking some rude questions, among them: why hadn’t the city done anything to memorialize the birthplace of the first popular culture superhero? Somewhere either before or after or concurrent with Sangiacomo’s crusade, Brad Meltzer, author of the newly published The Book of Lies that touched on the death of Mitchell Siegel, Jerry's father, got into the act. Researching for the novel, Meltzer went to Cleveland. "I wanted to see the exact spot where young Jerry Siegel sat in his bed on that rainy summer night, where a 17-year-old kid stared at his bedroom ceiling and gave birth to the idea of Superman," Meltzer wrote on his website. (Rainy? I thought it was sweltering.) Meltzer was distressed to see the condition of the place, which was nearly falling down, and started beating a drum in the same band as Sangiacomo. By the spring of 2008, the Siegel and Shuster Society rose out of the ashes of the Summer of Superman Committee, which fell apart when DC Comics dragged its feet about approving the use of Superman’s likeness in anniversary events. (DC is now aboard for future summer celebrations.) And the Glenville Development Corporation got into the act when it learned that the Gray house was somewhat dilapidated and in need of repair. By September, various minions had mustered to launch a 4-week online auction of numerous Superman mementoes to raise $50,000 to fix the house’s leaky roof, replace rotting wooden siding, and repaint the place. By the time the fourth auction concluded at the end of September, $111,047 had been raised. The so-called surplus funds will go for repairs inside the house, with the leftover money making up a fund for future maintenance. The highest price ($14,100) paid was for a drawing by artist Jim Lee that would depict the bidder and Superman; second highest price was paid by the same individual for a walk-on role in the tv show “The Heroes.” Another big price, $7,877, went for artist Travis Charest’s drawing of Superman. An original drawing of Superman by the character’s long-time illuminator, Curt Swan, went for $7,600; Frank Cho’s drawing of Supergirl pulled in $7,500. The Grays, meanwhile, have agreed to give the Siegel and Shuster Society first rights to buy the house when they decide to sell. The GDG and S&S Society plan to install commemorations in front of the Siegel house and at the site of Shuster’s home, once an apartment house but now a single-family dwelling at Armor and Parkwood avenues. The GDG also plans to clean up the Kimberly block, pulling up weeds and planting flowers and touching up the exteriors of some of the other houses. And the Cleveland City Council indicated it would give honorary names to the streets Siegel and Shuster lived on—Siegel Lane for Kimberly and Shuster Lane for Armor, “Lane” appropriated from the surname of the woman reporter who has plagued Clark Kent for so many years. (All of this information is taken from newspaper clippings from the Cleveland Plain Dealer sent to your faithful reporter by correspondent Ed Black, who was on-the-scene somewhat.) BADINAGE AND BAGATELLES The Election is barely over at Humor Times, James Israel’s formidable monthly newspaper of editorial cartoons: The December issue, No. 204, includes a raft of editoons commenting on the Obama win and, in addition, a slew of faux newsstories with these headlines: Obama Begins Planning Transition to Socialism, Communism McCain Disputes Election Results: ‘Electoral College Should be Based on Land Mass’ Bush Warns America: ‘I’ve Still Got 2 Months’ Bush Announces Film about Oliver Stone Palin Hoping to be Named Ambassador to Africa Subscriptions to this worthy enterprise are merely $18.95 for 12 issues and worth every cent. Send your check payable to Humor Times at P.O. Box, 162429, Sacramento, CA 95816. You can save a buck by subscribing via the website, humortimes.com. MOVIE REVIEW Whoever reviewed “Punisher: War Zone” for thestar.com did such a delicious job of slicing it up that I include virtually the whole thing here, vebatim: Wasn't the first time around punishment enough? Apparently not, because the long-delayed sequel to “The Punisher” (2004) is here, minus original lead actor Thomas Jane and high-priced villains like John Travolta. This sequel (or is it a "reboot," since there's no "2" in the title?) looks like it's been done on a budget after shooting delays, script changes, troubles landing a director and internecine squabbling, all faithfully chronicled online over the past four years by comic-book geeks living in their parents' basements. ... and it seems no expense has been spared on a TV ad campaign and website in an effort to boost box office. Relative unknown Ray Stevenson takes on the role of Frank Castle, a.k.a. The Punisher, now living rent-free underground in a subway maintenance room and still wearing the same scowl following his family's brutal murder years earlier (shown in a brief, gauzy flashback, which is the only time a hint of a smile crosses his glowering mug). While watching the news, he learns an Italian mob boss has once again escaped justice. With a bit of time to kill, it seems, Frank decides to add the don and his family to his endless list of people who deserve to be brutally and artfully exterminated. In the process, he manages to create a comic book-style adversary in the form of Jigsaw by dumping his evil ass into a glass recycling contraption, and the inevitable showdown is set in motion. It would be easy to say Stevenson shows all the emotional range of a cigar store aboriginal, or that he makes Charles Bronson look like Richard Simmons. But the fact is, he just doesn't inhabit the role with any conviction. A very hollow man, indeed. Dominic West is actually quite a howl as the former Billy the Beaut Russo, a.k.a. Jigsaw, wearing a badly stitched-together face that includes a section of horse hide. The other villains— Billy's brother, Loony Bin Jim, and Maginty, a meth-fuelled Rasta man with an Irish brogue—are all nicely set up to get their various grisly comeuppances, creating that cathartic rush of blood lust so integral to the enjoyment of these sorts of films. The carnage is super-grisly, with blown-off faces, shattered skulls and gaping wounds accompanied by smashing-pumpkins-and-cracking-bones sound effects and a throbbing, thundering score. The dialogue – like the tag line, "Vengeance has a name" – is particularly lame. To wit: "Sometimes I'd like to get my hands on God," fumes the Punisher. There's also much to offend, including the portrayal of Italian-American gangsters, references to "rag-heads" and the portrayal of black, Chinese and Russian gangs that will doubtlessly result in injured feelings. One becomes so inured to the relentless gore and mayhem that the climax is kind of a letdown. This film will surely get the critical drubbing it deserves. We'd go further: corporal punishment in a public place for the studio executive who okays the next instalment. XMAS LIST: BOOKS FOR A MERRY YULE :: PART TWO Here Are Some I Thought Highly Enough Of To Put in My Library (Even, Sometimes, Without Having Actually Read Them All the Way Through. Yet.) Romita’s Style. The 18th volume in TwoMorrows’ Modern Masters series is devoted to John Romita, Jr. (128 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w; paperback, $14.95), whose distinctive drawing style I’ve admired for some years. I’ve been at a loss about how to describe his way of rendering, so I was happy to see it called “bulky” in the interview herein conducted with him by series editor Eric Nolen-Weathington, accompanied this time by George Khoury. Romita, who has been drawing comic books since he was a teenager, the son of Marvel’s famed John Romita, Sr., insists, under persistent questioning, that his way of drawing simply evolved without his making any conscious decision about it. He denies being influenced by Frank Miller but says he was eager to work with Miller on the Daredevil book they did together, Man Without Fear, Miller writing. He also enjoyed collaborating with John Byrne, who put Romita’s name first in the credits for the Iron Man they did together. “That’s the kind of guy he is,” Romita said of Byrne. “He felt I was doing more work than he was. ... No one had ever acknowledged the artist the way he did because he is an artist first, and he felt that the artist deserved the majority of the credit.” Romita says that his father and Jack Kirby are the most influential in his development. Maybe the bulkiness came through Kirby, he speculated: “Maybe I got bulky as I attempted to be a little bit more powerful with the work” like Kirby. “Yeah, it was Kirby’s influence,” he finally concludes, “and my father’s influence, always telling me to make characters look three-dimensional and have weight to them.” Based on his remarks during the interview, my guess (which must be a guess because I haven’t checked the books in question) is that Romita’s bulky style began to evolve during his stint on Thor, which, Romita says, got him assigned to the Hulk: “I guess they saw me doing the Thor stuff and the big, bulky, kick-ass huge characters, and they felt like the Hulk would be a great follow-up.” In addition to his father and Kirby, Romita admires the work of John Buscema, Joe Kurbert, and the illustrator J.C. Leyendecker. I also admire Romita’s storytelling chops, which I first saw flowering in the Punisher books he did. He played around with page layouts to achieve pacing effects and dramatic emphasis. That sort of thing, he does consciously: “I’m always looking to do something different,” he said. “You’ve got to do whatever is fashionable at the time. If there’s a certain content or style that makes fans happy, I try to at least give a little bit of that flavor ... I don’t make great changes,” he said, but “I try to do something a little bit different. That’s the main thing is to do something different. I make an effort to do something different every time, as opposed to doing the same old fight scenes and the same old talk scenes. And I don’t cheat on backgrounds. ... Maybe I’ll sculpt a little bit more, maybe I’ll add a little bit more shading. If, in a couple of years, suddenly everything goes to film noir, maybe I’ll add more shadows. It depends.” Like all the Modern Masters titles, this one is amply illustrated with the subject’s art: the volume concludes with a 39-page gallery of Romita’s drawings, some in pencil. Other recent titles that I’m looking forward to reading include Volume Fourteen’s Frank Cho, which offers plenty of pictures of the toothsome Cho femmes and some pages in color; and Volume Fifteen’s Mark Schultz, which is also furnished with numerous instances of Schultz’s interpretation of feminine embonpoint and some color pages. All the Modern Masters books follow the same format—long interview with a knowledgeable inquisitor, liberally sprinkled with art, and concluding with a portfolio of the artist’s work. The series is up to Volume 20, Kyle Baker, with Mike Ploog at Volume 19. All are available at the publisher’s website, twomorrows.com. ***** Where’s Willie? The best book about war, Up Front, was written by cartoonist Bill Mauldin as padding for a collection of his cartoons about life in the trenches during World War II in Europe. What few of us realized upon first opening that volume is that Mauldin’s oeuvre of army life cartoons is much larger than the contents of Up Front suggest. The book culls Mauldin’s cartoons about hook-nosed Willie and pudding-faced Joe from Stars and Stripes, the army newspaper, but Mauldin wasn’t on the staff of S&S until February 1944. Mauldin enlisted in September 1940, long before the U.S. joined the hostilities in Europe, and he cartooned for his unit’s newspaper, the 45th Division News, for three years, most of it while the 45th was bivouacking its way around the U.S. Fantagraphics’ two-volume 716-page slipcased Willie & Joe (hardcover, $65) sets the record straight: virtually all of Volume I's 325 8x11-inch pages are devoted to cartoons Mauldin produced before going overseas in July 1943. The eponymous Willie and Joe, as a familiar pair, don’t show up until Volume II’s September 26, 1943 cartoon. Mauldin initially entitled his cartoon The Star Spangled Banter, and it carried that name as long as it appeared in the 45th Division News and in civilian newspapers like the Oklahoma City Times and the Daily Oklahoman, to which Mauldin occasionally contributed freelance; his cartoons acquired the title Up Front when they began appearing in S&S in late 1943. The cartoon had no continuing characters for most of its run. Willie, hook-nose on vivid display, shows up in the very first cartoon, October 25, 1940, and while he returns every so often thereafter, he’s not a constant presence. At first, his name is Joe, and he’s an Indian and talks pidgin and is often the butt of the joke or the comedic springboard. To Mauldin, growing up in New Mexico, and to many of his comrades in arms, “Indian humor was irresistible,” we learn in the Introduction to the Volume I by its editor, Todd DePasinto, the author, not at all incidentally, of a fresh biography of the cartoonist, Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front (372 6x9-inch pages; hardcover, Norton, $27.95). The 45th Division, made up of National Guard units from New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma and Arizona, “had more Native American soldiers than any other division,” plenty of fodder for ethnic comedy. Joe had an Indian last name, Bearfoot, and was inspired, somewhat, by a tentmate of Mauldin’s, a cultured and well-read athletic Choctaw named Rayson Billey; Joe also looked a good deal like Mauldin’s ne’er-do-well father. Joe was being called Willie by the time the 45th was invading Sicily in the summer of 1943. The original Willie, who would eventually take the name Joe, had a tiny moustache when he debuted as “Willie” in the summer of 1941 in a 32-page souvenir booklet, Star Spangled Banter, for which Mauldin drew 16 new cartoons and 16 pages of illustrations in a single 48-hour period. This handsomely designed and presented brace of books is worthy of its subject, one of the nation’s greatest opinion mongers in cartoons. For the whole Mauldin story, visit Harv’s Hindsight for February 2003. ***** An Affair of Schulz. Fantagraphics’ ambitious reprinting of all of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts is, with the most recent volume, up to 1970, twenty years of a 49-year run. The cast and their quirks are well-established by this time, and the comedy seems as fresh as yesterday. The Foreword this time is by Mo Willems; the series is still using Seth’s supremely restrained but distinctive design. Apart from the usual Peanuts shenanigans, there’s a conspicuous scrap of autobiography in this volume. When we get to July 1970, we see the strips David Michaelis singled out in his biography of Schulz as being about the cartoonist’s extra-marital affair with Tracey Claudius. Snoppy takes the part of the infatuated Schulz, and Tracey’s part is played by a girl-beagle at the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm, whom Snoopy keeps trying to reach by phone. “She has the softest paws,” he sighs, an echo of Sparky’s love-drenched comment about Tracey’s hands. What seemed funny when we first encountered this sequence now seems sadly self-indulgent, even maudlin, and pitifully saccharin in the extreme. Knowing all about Schulz’s secret love doesn’t, for me, enhance my appreciation of the comedy in Peanuts. But the rest of his masterpiece is still intact and worth re-visiting. If you haven’t started collecting this series, you ought to think about doing it while you’re still young and have all your teeth. (No, that doesn’t make any contextual sense; but it’s not supposed to.) ***** Eats

and Shoots. I recently purchased, at my own

expense (albeit at a reduced Internet price), my second copy of Lynne

Truss’s paean to proper punctuation, Eats,

Shoots and Leaves, solely because I learned

that the 2008 edition was illustrated, as it says here, by "acclaimed New Yorker cartoonist Pat Byrnes." I

don’t know how one gets to be "acclaimed," but Pat

certainly deserves it, dubious distinction though it may be. The

title of the tome refers to pandas, which eat shoots and leaves. But

if, as in the title of the book, a comma is placed between the first

and second words, the meaning changes entirely. Byrnes decorated the

cover with a picture of a panda, and pandas appear frequently

throughout, usually in full-page color drawings. After perusing the

publication and its plethora of pandas, I recalled my earlier life as

an English teacher, wherein I once did desperate battle with a

professorial type who ***** Up

To Here. From 1957 until 1963, Al

Jaffee, he of Mad’s superlative idiotic assemblage, the “fold-in,” produced a

syndicated cartoon called Tall Tales. Six years, 2,200 cartoons, as he tells us in his Preface to the

reprint volume at hand, inexplicably entitled Tall Tales (128 4x9-inch pages, b/w;

hardcover, $14.95 from Abrams). As you might deduce from the book’s

dimensions, the idea of the cartoon is vertical: after surveying the

newspaper cartoon landscape, Jaffee decided that his chances of

getting syndicated would be improved if he produced a feature that

was different—something that would fit into spaces in the

newspaper that other comic features couldn’t. And so he

conceived of Tall Tales,

seven inches tall instead of seven inches wide like a comic strip,

and one column wide. As a one-column feature, “it could be put

on any page of the newspaper: the classified section, the editorial

page, or anywhere else the editor wished to attract special

attention. Best of all,” Jaffee continues, “in this

[elongated] format I could create many gag situations by employing a

‘double take.’ In a seven-inch vertical space our eyes

can’t take in the entire area at once. As readers, we have a

tendency to look at the strongest focal point first and then the

secondary area. This dynamic allowed me to place the set-up for the

joke in the first-glance area and pull the punchline with the second

glance.” Here are some examples; and in the book, there are 120

more, culled from Jaffee’s six-year inventory of 2,200. Jaffee’s original concept had been to produce a wordless cartoon, which, by reason of the absence of language barriers, could be marketed overseas to the newspapers in other countries. Alas, when the syndicate management suddenly decided that because American readers liked words in their cartoons and urged Jaffee to accommodate this peculiarity, and he did, he lost his foreign markets and the will to continue the feature. It ended, and Jaffee folded-in. ***** High Visibility for Caricaturing. If you’ve been reading Entertainment Weekly lately, you’ll have encountered in every issue on the table of contents page caricatures of notable entertainers by Robert Risko. His work also shows up regularly in Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone, and with some regularity in The New Yorker, New Republic, Time, and Newsweek—to name a few of his outlets. He may, in short, be the most visible caricaturist now working. He uses few lines: his pictures are not colored drawings, as, for instance, those of the great Al Hirschfeld are when in color. A typical Risko caricature is a conglomeration of colored geometric shapes arranged to portray the iconic visage of some notable—the shapes defined somewhat by differing colors rather than solely by outlines. Almost 200 of his “images” are collected in The Risko Book, where they are lavishly displayed on giant 9x12-inch pages, bleeding all four sides (paperback; $35 but much less, only a couple bucks sometimes, from Amazon). The contents are arranged in categories: Television, Style, Music, Thinkers, Film, Scandals, Media, Sports, Theater, and Politics without any text interruption after Graydon Carter’s Introduction and the concluding interview with Risko conducted by Kevin Sessums. Risko came to New York in 1976 via Kent State, where he spent only a year, and a childhood in “rural Pennsylvania” just outside Pittsburgh. En route to the Big Apple, he spent some time in Provincetown where he drew caricatures for $5 each, attracting the attention of cartoonist Bobby London, who told him: “You should move to New York and do this. You could be the next Hirschfeld.” Risko moved to New York and convinced Andy Warhol to publish his caricatures in Interview. During five years or so of this exposure, Risko attracted the attention of the art director who was putting together a prototype for the revival of Vanity Fair, and before long, his work was appearing regularly therein. If we are to judge from Risko’s responses to Sessums’ questions, the caricaturist, who thinks of himself as an “artist,” is, at 52, a modest and relatively malleable contributor to magazine illustration, an editor’s dream: “I wasn’t making a living off my art,” he says. “I was doing photo retouching on the side. So I asked myself: if I can do this with a photo—feel that the work is better if it’s retouched—then why can’t I look at the editorial process as a bit of retouching? Or, another example: if I think that actors and singers and performers are better when they are able to take direction, then why can’t I take it too? Because of the constraints of a magazine deadline, it’s valuable to have an opinion that you trust, whether it’s the editor’s or the art director’s, in order to help you correct things that you’re maybe too close to see.” Writes Carter, the current editor of Vanity Fair: “In a Risko drawing, there are elements of all those greats of caricature who went before him. ... a bit of Pop, portions of Will Cotton and Paolo Garretto [both stalwarts in the old Vanity Fair], a heap of Miguel Covarrubias and a dash of Al Hirschfeld. ... Don’t be fooled by how easy it looks,” Carter continues. “Great artists or illustrators, like great poets, are all about economy. It takes years to develop a technique and decades more to simplify it.” Risko’s

simplifications sometimes miss their mark—more often than you’d

suppose in so prolific and visible an artist. But for every miss,

there are half-a-dozen brilliant hits, a few of which we’ve

arrayed here. Let’s Take a Break for Another of CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOSTS One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. Elizabeth Royte, author of Garbage Land, has written a book about the bottled-water industry. Entitled Bottlemania, it makes the following observations (among others, we may be sure), according to the Quality Paperback Book Club brochure: right now, more than a billion people in the U.S. don’t have access to safe drinking water; in 2007, Americans bought 50 billion single-serve bottles of water; to make plastic water bottles just for the U.S. market requires 17 million barrels of oil a year; groundwater pumping has dried up rivers in Massachusetts, Florida and other states; in 2007, Poland Spring alone burned 928,226 gallons of diesel fuel for operations and transportation. QPBC’s senior editor hopes Bottlemania will, like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, wake us up and serve “as the catalyst for a new movement.” In New York City, he says, “You cannot escape plastic water bottles. They’re underfoot in the subway, clogging up drain grates on the street, and appearing everywhere you turn. It’s no wonder. One plant in Maine pumps out 5 million of the little buggers every single day.” (My emphasis.) The ever-vigilant Time magazine revealed its Top Ten Editorial Cartoons of 2008 at its website. The array included work by Gary Varvel (2 cartoons), Bob Gorrell, Chip Bok, R.J. Matsonk Nate Beeler, Walt Handelsman, Rob Rogers, Heng Kim Song (of Singapore) and Chris Jurek, whom no one could identify. The work on display is, wouldn’t you know?, colossally insipid, prompting an epistle of outrage from the current president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, Ted Rall. I agree with everything he says and excerpt a couple paragraphs forthwith: “Your list of the Top 10 Editorial Cartoons of 2008 is an insult to editorial cartoonists, many of whom are losing their jobs to the economic downturn in the newspaper industry. In 2008 hundreds of brilliant political cartoonists produced thousands of hard-hitting, thought-provoking and hilarious cartoons about everything from the flash in the pan that was Sarah Palin to the rise of Barack Obama, and all you could come up with was this phoned-in crap? ... It's one thing for lousy cartoons to appear in print somewhere. It's downright appalling to anoint them the best work produced by a field in a given year. Heck, even among the artists you selected, they all did much better work than the pieces you picked. How would Time like it if someone published a list of the Top 10 Newsmagazines of 2008—and it was just a list of blogs by 16-year-olds typing in their parents' basements?” From a friend via e-mail: Back in 1990, the Government seized the Mustang Ranch brothel in Nevada for tax evasion and, as required by law, tried to run it. They failed and it closed. Now, we are trusting the economy of our country and $750-plus billion to a pack of nit-wits who couldn't make money running a whore house and selling booze. Now if that don't make you nervous, what does??? A gem or two from Garrison Keillor: We are a modest people with much to be modest about, self-effacing, anxious to efface ourselves and not wait for others to do the job. ... [An ability to express personal preferences] was frowned out of us when we were children. ... What do you want? What would make you happy? I don’t know. Just give me some of what those people over there are having. And Now, Some How-to Tomes THE GRAND MASTER REVEALED Like John Garvin, I’ve heard all my adult life of the “Landon School” and its famed correspondence course in cartooning, in which, it seems, nearly every cartoonist of a certain vintage had matriculated—from Carl Barks to Chic Young, with Milton Caniff, Jack Cole, Edwina Dumm, Floyd Gottfredson, V.T. Hamlin and Bill Holman, Edgar Martin and Bill Mauldin, and Gladys Parker and Allen Saunders scattered in between. With alumni like that, I thought, the Landon Course must be something extraordinary, and I yearned to know what it was like, exactly. Unlike me, Garvin was not content to merely yearn: he wanted to witness the entire Landon Course, and, when not teaching himself to paint funny fantasy animals in the manner of Carl Barks (which he now does with great skill, see johngarvin.com), he kept delving into obscure catalogues of auction-house offerings and scouring the Web until, at last, he found a complete copy of the course as it was issued in 1922. And then he published it in facsimile, The Landon School of Illustrating and Cartooning (246 8.5x11-inch pages in paperback; $21.95 from Garvin’s EnchantedImages.com). The book is not only an excellent antique peek into cartooning history: it’s also an excellent instructional tome, one of the best of its kind even today. Born December 19, 1878, Landon the Legend grew up in Ohio and eventually went to work for the Cleveland Press from 1900 to 1912. In those years, a newspaper staff artist drew everything from borders around halftones to depictions of sensational on-going trials as well as cartoons and caricatures and representations of local natural disasters: like others of his ilk, Charles N. Landon was often a pictorial reporter. His last five years at the paper, he managed the art department. That’s how he learned how to develop talent, Garvin tells us, an insight that gave birth to an idea. Landon and another Cleveland newspaper artist, W.L. Evans (probably on staff at the Cleveland Leader), decided to put this specialized knowledge to work in a more ambitious way and planned to open a correspondence school together. But Evans fell ill on the eve of the project’s commencement, and by the time he recovered, Landon was off and running on his own, having launched his correspondence school in 1909. Evans then opened his own correspondence course, rivaling Landon and several other correspondence schools, including ones run by the likes of Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman and Billy DeBeck and, even, later, Russell Patterson. But of the rivals, the Federal School of Cartooning out of Minneapolis was the most competitive and enduring: Charles Schulz went to work for it when he got out of the Army. Landon eventually became art director of the Newspaper Enterprise Association, one of the largest syndicates supplying comics and feature material to newspapers. He continued operating his correspondence course, which also functioned to screen talent for syndication: if Landon saw a good cartoonist among his students, he would wait until the student graduated, then sign him up with NEA. And if the new recruit was successful, the Landon School’s promotional material claimed the success was a direct result of taking the course. Which, strictly speaking, was almost true—even if the talent was inherent with the student rather than acquired through diligent course work. Landon continued running his correspondence school even after moving to New York as art director of Hearst’s Cosmopolitan. “C.N.,”as

he liked to be called, favored “selected sartorial elegance

like celluloid cuffs and spats,” according to Roy Crane, whose Wash Tubbs Landon

syndicated as soon as he learned Crane was one of his graduates. When

he was a boy, Arlo “Tommy”

Thompson, now a retired graphic designer and

industrial cartoonist living in San Diego, visited Landon in his

Cleveland lair and reported that he was “a portly man with

iron-gray hair, pale complexion, and piercing blue eyes.” He

spoke, Crane said, with a piping voice that whistled through his