|

|||

OPUS 227 (July 31, 2008). We take a long expedition this time into the jungles of Satire—how it works and how it sometimes doesn’t work, misfiring and shooting itself in the foot. While The New Yorker’s recent Obama cover is the obvious victim lately, we also review Bob Levin’s recent biography of a particularly outrageous satirist, Hustler’s Dwaine “Chester the Molester” Tinsley, which, unlikely as it may be, is somehow related to the tribulations of Barry Blitt at The New Yorker and a jailed Dutch cartoonist. We also rehearse the history of the founding of the San Diego Comic-Con, celebrate Pickles 500th and 501st, rejoice at the demise of Diesel Sweeties, and marvel at the endless fakery going on in Get Your War On. And we admit to being hoaxed last time on the Bushmiller-Beckett correspondence. Sigh. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US Eight

comic books with more than 500 issues, DC finishes Spirit,

comic book biographies of Obama and McCain due in October, Diesel

Sweeties dies in print, superheroes at the

movies, two more editoonists less, Wertham’s papers off-limits, Blondie repeats PICKLES

HITS 500 AND THEN 501 HAVE COMICS ARRIVED? A

short history of the San Diego Con’s founding PASSIN’ THROUGH Creig

Flessel, 1912-2008 The

Froth Estate: News Magazines Give Up News Editoonery:

Two Novel Cartoons COMICS PAGE WATCH Candorville,

Flying McCoys, Blondie, Beetle Bailey, Funky Winkerbean, Opus, Lio,

Peanuts, Dilbert, Get Fuzzy, Pajama Diaries, Pearls before Swine FAKE COMIC STRIP GOES INTO FAKE ANIMATION Get

Your War On Dutch

Cartoonist Jailed for Indecent Cartoons AMERICAN CARTOONIST JAILED FOR INDECENT CARTOONS A

Review of Bob Levin’s Most Outrageous:

The Trials and Tresspasses of Dwaine Tinsley and Chester the Molester THE QUESTION OF SATIRE The New Yorker’s Obama Cover Tasteless

Cartoons HOAXED The

Fabled Bushmiller-Beckett Correspondence And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

NOUS

R US The

granddaddy of all the mutant funnybooks, Uncanny

X-Men, reached its The DC Comics archival project reprinting all 12 years of Will Eisner’s iconic Spirit weekly comic strip concludes with the 24th volume and the strip for October 5, 1952. Although I’ve faulted many of DC’s archival volumes for garish color restoration, the Spirit reprints avoided the desecration by using cream-colored paper, which reduced the glare of the color, preserving the visual aura of the comics’ initial appearance on off-white newsprint. The project took eight years, and Editor & Publisher hints that a 25th volume is forthcoming, reprinting the daily Spirit strip, and even a 26th volume, featuring Eisner's post-1952 work with the masked detective. Volume 24 includes the eight 1952 “Outer Space Spirit” installments drawn by Wally Wood in his inimitable manner, Eisner’s last-ditch attempt to keep the Spirit going. But Wood had trouble meeting deadlines for both Eisner and EC Comics, where he was just beginning, and Eisner, deeply engaged in devising comics for instructional and related purposes, hadn’t the energy or inclination to keep the feature alive—particularly since the circulation of the Spirit Sunday supplement was falling off: it wasn’t bringing in enough revenue to be worth continuing. Marvel

has produced a tribute to Steve Gerber’s iconoclastic creation in Howard the Duck

Omnibus, which purports to reprint all of the

Fated Fowl’s comic book and other appearances; the whole story

of Howard is rehearsed in Harv’s Hindsight. ... IDW Publishing

will release 28-page comic book biographies of Barack Obama and John

McCain on October 8, but the comic books can be pre-ordered, E&P notes, and they can also be purchased for downloading by mobile phone

users via GoComics.com. ... Rich Stevens’ Diesel Sweeties, a

comic strip that looks as if it has been drawn by a computer in the

primitive throes of digital development when pixel lines still looked

like raisins on a string, ceases its print version in newspapers on

August 10, reports Alan Gardner at dailycartoonist.com. Stevens was

working himself to death by producing both a newspaper and a web

version of the strip. “When the workload started making me

sicker and fatter,” he said, “it was pretty much a

no-brainer which job had to go.” If Diesel

Sweeties had caught on in newspapers and

become an overnight success like, say, Calvin

and Hobbes or Zits,

Stevens might have made the contrary decision. I must admit that I’m

glad the artistic fashion statement represented by Diesel

Sweeties didn’t catch on: it threatened

to turn the art of delineation into a species of needlepoint and, in

the process, reduce me to tears accompanied by torrents of

vituperative contumely. Sorry, but I really didn’t like the

execrable appearance of this effort. You can tell, right? ... In

another ending reported by Gardner, Tribune Media Services has shut

down its Comicspage.com operation; the homepage now directs visitors

to find their favorite comic strips over at Universal Press

Syndicate’s GoComics.com (where, to spill the whole bowl of

beans, you can also sometimes find fragments of Rancid Raves, posing

as a blog). ... And in yet another ending, Gardner notes that “Danish

prosecutors have dropped charges against one of the Muslim men who

were arrested for plotting the assassination of cartoonist Kurt

Westergaard,” one of the perpetrators of the notorious Danish

Dozen. ***** At the movie theaters, “The Dark Knight” blew “Iron Man” out of the water, out of the skies, and off the planet, bringing in a reported $155 million on the first weekend, another $75 or so the next weekend, $230 million total. The Golden Avenger, erstwhile champion grosser for 2008, scored only about $100 million its first week and totaled only $177.8 after two weeks. The stunning success of the Bat-movie may be due to a morbid desire among movie-goers to see Heath Ledger’s over-the-top final performance as the certifiably sick Joker. Meanwhile, at MovieMaker Magazine, Lauren Barbato cobbled up a list of ten of the best, “most popular and/or ground-breaking graphic novel movie adaptations”; in chronological order: “Superman: The Movie” (1978), the first of the modern special-effects enhanced superhero flicks; “Batman” (1989), with Michael Keaton as the Cowled Crusader and a memorable Jack Nicholson playing the Joker and stealing the slow; “X-Men” (2000), whose mutant abilities “made for great special effects possibilities on screen”; “Spider-Man” & “Spider-Man II” (2002 & 2004), setting a “new superhero standard with energetic, big-screen renderings of Peter Parker (Tobey Maguire) in web-slinging flight; “American Splendor” (2003), creatively knit together fiction and reality to illuminate the daily life of everyman Harvey Pekar, the comic book series author, a disgruntled file clerk played by the seemingly down-and-out Paul Giamatti; “Hellboy” (2004), the unlikely story of a demon who, raised by humans, decides to take their part against the forces of the supernatural that menace from every side in Mike Mignola’s comic book original; “V for Vendetta” (2005), a political satire, suspense thriller and love story, adapted from Alan Moore’s graphic novel of the same name; “Sin City” (2005), Frank Miller’s grim black-and-white graphic novel series brought to the big screen with the visuals nearly intact (blazing the way for Miller to do something similar, we all suppose, when he finishes the screen version of Will Eisner’s Spirit for release next winter); “Persepolis” (2007), the animated adaptation of the graphic novel, created by the latter’s author, chain-smoking, black eyeliner-wearing Marjane Satrapi; and “Iron Man” (2008), which seemed to prove, thanks to Robert Downey Jr.’s performance, that superhero movies can be successful works of cinematic art. At the San Diego Comic-Con last month, Zack Snyder presented a sneak preview of his long-awaited film version of Alan Moore’s Watchmen, the only graphic novel to receive the prestigious Hugo Award. Snyder is resolved to reproduce Moore’s work as exactly as the film medium permits, and in devising the trailer he screened in San Diego, he was determined to show pictures, he told Larry Carroll at MTV, in order to end the debate about how close to the graphic novel the movie will be. “I wanted to show pictures right now so people can go, ‘Wow, I recognize that frame.’” Carroll observed that “the centerpiece of the trailer seems to be Doctor Manhattan's transformation,” and Snyder agreed: “Doctor Manhattan is an interesting person to hang the movie on in a lot of ways, because he's the conscience of the movie. His perspective on humanity and mankind is a lot of the conscience of the movie, for me anyway, and how he relates to the other characters is really important. He's also spectacular in his creation, so it seemed fun.” The

Con also saw the introduction of "DC Universe Online,” an

online videogame that lets players invent superheroes that could face

off against Superman or Batman. According to Agence France-Presse at

newsinfo.inquirer.net, “Players will be able to play as any DC

super characters or design a supernaturally powerful character of

their own. They will then get to pursue paths of good or evil”

just like in the funnybooks. ***** Dwaine Powell, the veteran editoonist we mentioned last time whose paper told him on the eve of his departure for the annual convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) that his full-time job was being reduced to something akin to freelance status, has resigned rather than accept the new role, reports the intrepid comicsreporter.com. Powell has been with the paper, the Raleigh News & Observer, for 33 years. Another long-time staffer, Don Wright who editoons for the Palm Beach Post in Florida, has also been ushered out the door: he accepted a buyout, Tom Spurgeon said. Wright, it seemed to me, filled a role on the paper somewhat larger than editorial cartoonist. Several years ago, I interviewed him in his office at the paper. It was evening, and most of the staff had gone for the day. While we were talking, a youth from the pressroom knocked on the door. Some minor crisis about what to put in the paper where, as I recall—a layout question that should be guided by news sense, not a printer’s convenience—and he asked Wright about it because the cartoonist was the only editorial staffer around. Wright answered his question, the kid went back to the presses, and the paper came out on schedule. And this is the kind of staff member the paper has decided it no longer needs—the reliable, experienced knowledgeable sort. Tells us a great deal about the state of journalism in Palm Beach, Florida. Wright, as you can doubtless tell, is nobody’s fool: he’s 74, I understand, and since the first buyout offers extended are usually the most generous, he probably came out on top in the deal. At his website, Michael Barrier reports that Fredric Wertham’s papers, archived in the Library of Congress’s Manuscript Division, are not available for perusal by researchers. Barrier jumped through all the requisite hoops to get access to the trove, but his request was, ultimately, denied by the executor of the Wertham estate. When he asked why, since his credentials seemed to be in order, he received this reply from Leonard C. Bruno of the Library’s staff: “For quite some time now, the Wertham executor has consistently rejected any and all requests for access. These are rejected outright, with no explanation, and apparently without consideration of the requestor's intent, affiliation, explanation, supplication, or anything else. Even requests that have been limited or targeted to only certain containers, rather than for total access, have failed. Unfortunately, you have joined a growing group of scholars unable to gain access.” About which, Barrier remarked: “Very odd—but, as Bruno added, the executor's arbitrary sway will soon end: the Wertham papers will come open May 20, 2010. At which point, I'm sure, a lot of irritated researchers will join me in trying to figure out just what it was that the executor was trying to hide.” At his ComicsCurmudgeon.com, John Fruhlinger reported, according to E&P, that a recent Blondie strip was nearly identical to a 1952 Blondie. The case, E&P speculated, may “make readers wonder how often long-running ‘legacy’ comics repeat themselves.” Today’s Blondie is drawn by John Marshall and written (or coordinated) by Dean Young, the son of the strip’s creator, Chic Young, who was, in 1952, still producing the strip with the aid of Jim Raymond, who was drawing it. In each of the episodes 56 years apart, Mr. Dithers, Dagwood’s irritable boss, is depicted “barging into the Bumstead house and bathroom to see if the bathing Dagwood is home. In the last panel, a towel-clad Dagwood is pictured hanging out of the window to avoid his boss.” Iowa's

State Historical Museum in Des Moines has mounted an exhibit of the

comic strip Alley Oop to mark the 75th anniversary of the caveman comic, which was created

in 1933 by V.T. Hamlin, of

Perry, Iowa. The strip, E&P tells us, is now handled by Jack Bender,

a former Iowan, and his wife, Carole. ... The 9th Japan Expo Awards

in Paris, France last month expected over 100,000 to attend, but only

80,000 showed up, the same as last year’s number. ... In India,

P.J. George lists in The Hindu “the essential graphic novels” should you really want to

grasp the concept: Maus: A Survivor’s

Tale by Art

Spiegelman, Blankets by Craig Thompson, The

Boulevard of Broken Dreams by Kim

Deitch, Batman: The

Dark Night Returns by Frank

Miller, Watchmen by Alan Moore and 300 by Miller. Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s http://www.strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FIVE HUNDRED PICKLES AND COUNTING Brian Crane’s comic strip, Pickles, reached the round-number landmark of 500 client newspapers on July 10 and then added another paper so quickly that his syndicate, Washington Post Writer’s Group, couldn’t get the press release out fast enough to celebrate the milestone in pristine double-zero glory. The strip revolves around Earl and Opal Pickles, who have been married for over 50 years and are sharing their golden years with their 30-something daughter Sylvia, her husband Dan (who seldom, lately, shows up), and their grandson Nelson. The household is enlivened from time to time by a typically dense dog named Roscoe and a cynical cat, Muffin. The press release reports that Crane was pleased, and a little surprised, by the news. "I honestly never thought Pickles would be in this many papers," Crane said. "I try not to think about it, really, or I’m sure I would probably get stage fright. In my mind this comic strip is just something I do every day in the privacy of my home to amuse myself, and then I mysteriously get paid for it." Pickles' growth has been steady for most of its 18 years, according to WPWG, but its subscriber list has spiked recently, perhaps coincident with the increased attention Crane has given the last few years to Earl, who has grown more quirky with age, and Opal, whose patience enables her to endure. Maybe it’s really time for another strip about the golden years. Or maybe newspaper editors, for some inexplicable reason, are finally capable of recognizing good comic strip humor and purely competent art. "One cartoonist e-mailed me with news of a recent Pickles win and called Brian's strip the 'Godzilla' of the comics pages," said Amy Lago, comics editor for WPWG, who added that 500 clients for a Writers Group strip is "more like 800 in 'promotion-speak." WPWG Editorial Director Alan Shearer explained, "We've always been honest with our numbers, because, well, we work at a newspaper. Five-hundred [and one] is the real number of daily and Sunday clients. And it's quite an achievement for one of the most gifted humorists in our business." In contrast, most other feature syndicates report “sales” not subscribing newspapers, and since comic strips are sold separately as daily features or Sunday features, a paper that subscribes to both dailies and the Sunday is counted as two “sales.” Thus, a comic strip reporting a circulation of 1,000 might appear daily in 600 papers and Sunday in 400 of the same papers. Soon after Pickles’ debut in 1990, Crane "retired" as an art director for an advertising agency in Reno, Nevada, to devote his full attention to his strip. In 1995 and 2001, Pickles was nominated for best comic strip of the year by the National Cartoonists Society, winning in 2001. Crane was also nominated for the coveted Cartoonist of the Year Reuben Award in 2006. Crane was born in Twin Falls, Idaho, but grew up in the San Francisco Bay area. He graduated with a degree in art from Brigham Young University in 1973. He lives near Reno with his wife, Diana. He's the proud father of seven and grandfather of seven.

HAVE

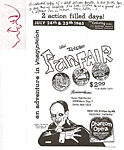

COMICS ARRIVED? For the second week running, the cover of Entertainment Weekly was devoted to comic book superheroes: on July 25, the impending (March 6, 2009) movie of Alan Moore’s Watchmen, and on August 1, the Batman movie. Status-starved funnybook fanboys may regard this as the apogee of their aspirations, a sure sign that comic books have “arrived” and now occupy a significant place in American popular culture. We need no longer hide our comics behind newspapers or physics workbooks whilst furtively reading them on the subway going to work or in the study hall while avoiding work. It’s been a long wait, but it’s been worth it. Sorry, but none of that is an accurate interpretation of what being on the cover of EW means. In the first place, it’s the movies that are on the cover, not the comic books. The articles within scarcely mention the four-color pamphlets that inspired the annual explosion of summer blockbusters featuring one or more of the longjohn legions. Comic books, in other words, are still down there at the bottom of the cultural slag heap. In the second place, it’s money that’s being celebrated on the covers. Nothing in a capitalist state achieves any sort of status without first being proven as capable of generating vast sums of money for those invested in the artifact. Years ago, before most of us were born, I opined hereabouts that once comics migrated to movies and started pulling down big bucks, the humble albeit despised print medium would finally rise in cultural regard as an art form, becoming the equivalent of poetry and painting in oil. I was partly right: the money is there, guaranteeing that comics superheroes are getting serious notice by moguls everywhere, but the humble medium is still, as I said, humble. Maybe next year. The July 25 issue of EW, while depicting Moore’s Watchmen—the pupil-less Doctor Manhattan looming large and blue behind the Comedian, Rorschach, Nite Owl, Silk Spectre, and Ozymandias—is also flagged “Comic-Con Special,” and inside, following the preview of the “Watchmen” flick, a 7-page article glimpses the movies that were to be debuted or previewed at the Con over the July 24-27 weekend. If that’s not “arrival” for the Comic-Con, I dunno what is. Well, yes, I do: real, authentic “arrival” in the cultural swim of the nation would entail more than a mere timeline diagram of the history of the Comic-Con. The timeline occurs on page 27, or, rather, on half of page 27. It is accompanied by a short 300-word story that notes that in 1970, the Con’s first year, the infant gala reportedly drew but 300 comic book fans to an old downtown San Diego hotel, which was creaking into oblivion by then. Now the Con is held at the city’s gigantic Convention Center on the waterfront, and last year, officials say it was attended by 125,000 persons. I was there last year for two days, signing copies of my Caniff biography, but I didn’t have time to do a count. The timeline also observes that movies were in the mix at the Con almost from the beginning: in 1976, “attendees were shown slides from a movie called ‘Star Wars’ a year before the film’s release.” (Astonished, EW repeats in disbelief, “Slides!”) In

fact, movies were integral to the Con experience before that: Shel

Dorf, who had helped launch comic conventions

in his home town, Detroit, in 1965 (building upon the previous year’s

effort by one Robert Brosch) with the first “Detroit Triple Fan

Fair” for comics, fantasy, and movies, transported the notion

to San Diego when he moved out there late in the decade to join his

parents, who had retired there. In the 1965 “Triple Fan Fair”

program booklet, Shel appears as Chairman, saying, in a Statement of

Principles, that “by establishing this convention, we hope to

bring together people” with an interest in preserving rare

material and to foster “the appreciation of Comic Strips,

Films, and Fantasy Literature as genuine Art Forms.”

Furthermore, “we hope to draw a close bond between the creative

artist and his audience.” Here’s a caricature of Shel

(perhaps even a self-caricature in the manner of one of his heroes, Chester Gould) and a

copy of the promotional poster Shel produced in silk-screen. Although this year’s Comic-Con is sometimes billed as the 39th, it is actually the 40th. The first Comic-Con was a one-day affair held March 21, 1970 to test the waters and generate a little capital for the subsequent three-day affair, held that summer, August 1-3, and usually counted as the “first.” For the first Cons, Shel rounded up an impressive list of special guests (Jack Kirby, who attended every Con until he died in 1994, sf maven Forrest J. Ackerman, Mike Royer, and sf authors Ray Bradbury and A.E. Van Vogt.) The initial venture capital was supplied by Richard Alf, who, still a teenager, was one of the first mail-order back-issue dealers. And a raft of savvy “in fandom, conventions, publishing, and retail sales” was provided by Ken Krueger, who had attended the “very first ‘scientifiction’ convention in 1939, officially making him a member of the elite-if-obscure group known as ‘First Fandom.’” I’m quoting here cartoonist Scott Shaw, who was among the group of teenagers who had assembled under Dorf’s wing to put on the first Con and who rehearsed the birth pangs of the Con in the inaugural issue of his Cartoonist-at-Large in July 2005 under the heading “The ‘Secret Origin’ of San Diego’s Comic-Con.” Shaw and some of his sf fan friends had trekked north in 1968 to attend the World Science Fiction Convention held in Berkeley. Bitten by the con-bug, they soon “fell in” with Krueger, who was running a “flyblown bookstore” at Ocean Beach (perhaps named, inexplicably, Andy’s News), where they all met to talk about science fiction and comics. Unbeknownst to Shaw, around the corner, figuratively speaking, was Shel Dorf, a 35-year-old commercial artist and life-long comics collector who was meeting with his own group of comics fans (about which, more in a trice). Shaw was working at a B. Dalton bookstore, where one day he encountered a customer who was looking for a series of Prince Valiant reprints “thinly disguised as children’s books.” This was Bob Sourke, who, when he learned of Shaw’s cartooning bent, invited him to a get-together of comics fans he knew. And this group was the one clustering around Shel. “In 1969, Shel arranged trips for many of us to visit Jack Kirby and his wife Roz at their home in Thousand Oaks, California,” Shaw wrote, and out of the Kirby-fan fellowship emerged “an amalgamated social blob that was San Diego’s core of funnybook fandom,” which, by the fall of 1969, was planning the first one-day con for the following March. They met at the U.S. Grant Hotel, not “the snazziest of venues,” Shaw confessed, but the only hotel in town “willing to risk hosting an event that would garner such low bar-attendance” because the attendees were mostly teenagers. (And most of them were male, Shaw says: “”Other than young Jackie Estrada, now co-publisher [with her husband Batton Lash] of Exhibit A Press and administrator of the prestigious Eisner Awards, the only females attending the 300-attendee event were fans’ mothers.”) Krueger and Dorf signed the hotel contract—“the rest of [the sponsors] were under age,” Shaw explained. In 1971, the Comic-Con felt healthy enough to move to a more respectable locale, the San Diego campus of the University of California at La Jolla, August 6-8. The next year, August 18-20, another move—this time, to El Cortez Hotel, on a hilltop over looking downtown San Diego. In 1973, the Con added a day, meeting August 16-19 in the Sheraton Inn on Harbor Island, where attendance passed 1,000 for the first time. According to a post-con report, most of the attendees, 30%, came from San Diego with an additional 15% from the surrounding county, but almost 10% came from out-of-state. The Con generated a $200 profit, half of which was donated to the Academy of Comic Book Arts. Subsequent Cons returned to El Cortez (where, Shaw observed, “the swimming pool was clouded with fan-dispensed shark repellant”), branching out into the downtown Community Concourse for the exhibit. By the 1990s, the affair had grown to such an extent that only San Diego’s monster Convention Center could hold it. The 1973 Comic-Con program booklet reviews the Con’s history and names many of those responsible for the success of the previous events. Shel is listed as “founder and coordinator”; others whose names appear repeatedly are Krueger, Shaw, William Lund, Richard Butner, Bill Schanes, and Mike Towry. And Barry Alfonso, whose ad about buying comics in a local circular in the fall of 1969 had attracted the attention of San Diego’s newest comics fan, the recently arrived Shel Dorf, who contacted Alfonso, who introduced Shel to Richard Alf. The three started a club, the San Diego Society for Creative Fantasy, which was the “group,” all teenagers except Dorf, that Shaw’s group of fellow teenagers soon amalgamated with and began planning the first Comic-Con, which, by the way, was officially entitled the San Diego Golden State Comic-Con. Tom French eventually joined the regulars to coordinate the “dealer’s room,” which, before too many years, had expanded into a full-blown “exhibition” that demanded floorplans and administration to keep track of space assigned and fees paid. The Con was run entirely by unpaid volunteers for years, but as it grew, the demand for a somewhat more committed staff grew, and by the late 1980s, Fae Desmond was employed full-time as the Con’s first salaried manager. Other paid staffers soon accumulated. None of this—and no names—are mentioned in the EW “history” of the Comic-Con. I met Shel in 1982. We were both attending Milton Caniff’s 75th birthday party in Columbus, Ohio, at Ohio State University. Soon thereafter, we worked together on a comic strip we hoped to get syndicated: it was Shel’s brain child, and he called it Lines; he wrote it, and I drew it. Before we got started, though, Shel thought we should discuss the terms of our partnership, and he wanted Caniff as referee. At the time, Shel had been Caniff’s lettering man on Steve Canyon for several years. He arranged a conference call for the three of us. One of Shel’s questions was about divvying up the plunder, if any. I said, “Fifty-fifty—that way we’ll both think we got the short end of the stick.” Caniff laughed his approval. The strip didn’t sell, so the question was moot. A question about which there is no moot, however, is: Who is most responsible for the existence of the San Diego Comic-Con? Shel would be the first to say that creating and nurturing the Con wasn’t a one-man enterprise: it took work by many people, of whom Shel was only one. But we can arrive at the truest answer to the question by asking it another way: Would the San Diego Comic–Con have come into being without Shel? The answer, I believe, is, No. He brought the idea of a comic convention with him from Detroit, where he’d been instrumental in staging the nation’s first in Motor City. In San Diego, he found a cadre of interested youths who were willing to do the work, and Shel was happy to delegate. But year after year, he was the sparkplug, stimulating interest in the Con among fans and professionals alike, keeping the flame alive, until today—an delirious annual conflagration at the water’s edge. One of Shel’s earliest cohorts, Mike Towry, who was publicity chairman for the first Cons while 15 and 16 years old, wrote Shel in 2002: “It is impressive what the Con has evolved into, but it has only had the chance to do so because it was founded upon your true love of comics, their creators, and their fans, and because you generously shepherded it through its critical early years at material disadvantage to yourself.” Towry goes on to report that his oldest son was a volunteer at the Con that year. Shel officially “retired” as “founder and coordinator” of the Con in 1984, by which time attendance at the Con had reached 4,000. He has many pleasant memories of his years with the Con and all that the association engendered. As Laura Embry wrote in a 2006 article in the San Diego Union Tribune: “The convention helped him get more work as an artist and a writer and enhanced his reputation as a historian of comics. When Warren Beatty turned Dick Tracy into a movie in 1990, Dorf was a consultant.” And if there was a strip that captivated Shel more than Caniff’s Terry and Steve Canyon, it was Gould’s Dick Tracy. “Dorf can remember as a kid waiting on his front porch for the carrier to bring the day’s paper so he could learn what had happened to the square-jawed detective. He loved the stories, and he loved the artwork.” One of Shel’s memories he shared with me, a 1975 letter from Superman’s co-creator, Joe Shuster, who wrote Shel from his home in Forest Hills, Long Island, to express his gratitude at receiving, the previous summer, the Inkpot Award, the Con’s distinguished achievement trophy. Wrote Shuster: “It is great to know that, after all these years, I am still remembered—and that the original Superman art, the drawings that I created, still hold fond memories for all the faithful fans. I know that Jerry Siegel [who also got an Inkpot that summer] feels the same. ... Shel, I believe you are doing a great service to all the comic book artists and writers by granting them full recognition for their labor, talent, and creative work. Due to your devotion and diligent efforts, I am certain that future generations will have a much greater appreciation of the work done by the pioneers of the comic book world—and that the artists and writers who have contributed so much to this field will now receive full credit for their accomplishments.” I’m

not sure that Shel has received full credit for his accomplishment as

“founder and coordinator” of the nation’s largest

comic convention. Entertainment Weekly doesn’t even know who Shel Dorf is. But we all do, and we’re

grateful. As Milton would say, Big Thanks, Shel. ***** But the size and success of the Comic-Con doesn’t mean comics have arrived either, any more than the superhero covers of EW prove that comics are now widely appreciated as an art form. The success of the Con is a tribute to movies money. As EW’s cryptic history of the event notes: “In the last decade, Comic-Con has exploded into the most important pop culture event on Hollywood’s calendar—a frenzied marketing free-for-all where, each July, major studios and networks flaunt their coolest new projects, trying to woo an audience of 125,000 sci-fi, fantasy, and horror fans.” As Shel said, “Hollywood has kind of hijacked the Con.” And comics fans are not what Hollywood is after. The number of comic book booths in the mammoth Convention Center’s exhibit halls is further testimony to the subversion of the Comic-Con to the power of celluloid and money in a capitalist society. Mostly, the booths display video games and motion picture tie-ins and toys derived from the lot. Comics are a small delegation; and old comics, the tattered and yellowed survivors of the Golden Age, are in even smaller supply. The guest list for the dozen years or so has included very few comic strip cartooners. In Shel’s regime, they were there in considerable numbers, their presence conjured up by Shel’s insistent letters. These days, comic book artists and tv and movie stars far outnumber the strippers. A few years ago, the National Cartoonists Society began taking a display booth in the exhibit hall, and NCS members, predominantly comic strip ’tooners, appeared at a panel presentation together, discussing their craft. This year for the first time in a decade or more several newspaper cartoonists were among the Con’s guests: The Knight Life’s Keith Knight, Family Tree’s Signe Wilkinson, Mother Goose and Grimm’s Mike Peters, who also does editorial cartoons for the Dayton Daily News, and fellow editoonist, San Diego Union Tribune’s Steve Breen, who does a comic strip called Grand Avenue. Midway through the Con, a panel discussion on political cartooning featured Wilkinson (who does editorial cartoons for the Philadelphia Daily News), Peters, Breen, and 2008 Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Ramirez (Investor's Business Daily), Bill Schorr (United Feature), and "Mr. Fish" (LA Weekly/Village Voice) was moderated by Daryl Cagle, the cartoonist who also runs the Cagle.msnbc.com cartoon site and the Cagle Cartoons syndicate.

MOTS & QUOTES FROM GEORGE CARLIN Bipartisan usually means that a larger-than-usual deception is being carried out. Once you leave the womb, conservatives don’t care about you until you reach military age. The owners of this country know the truth: it’s called the American Dream because you have to be asleep to believe it. Ever wonder about people who spend $2 apiece on those little bottles of Evian water? Try spelling Evian backward. Environmentalists changed the world “jungle” to “rainforest” because no one would give them money to save a jungle. In this era of “maxi,” mega” and “meta,” you know what we don’t have anymore? “Super-duper.” I miss that. Just when I discovered the meaning of life, they changed it. As you swim the river of life, do the breast stroke. It helps to clear the turds from your path. By and large, language is a tool for concealing the truth. Think of how stupid the average person is, and realize half of them are stupider than that. Elsewhere (from John Nichols in the pages of The Nation): Countering GeeDubya’s claim that his “war on terror” was a battle for freedom, Carlin asked: “Well, if crime fighters fight crime and fire fighters fight fire, what do freedom fighters fight?” ... But Carlin’s usual targets were the religious, governmental and economic elites. “The real owners are the big wealthy business interests that control things and make all the important decisions,” Carlin once said. “Forget the politicians; they’re an irrelevancy. The politicians are put there to give you the idea that you have freedom of choice. You don’t. You have no choice. You have owners. They own you. They own everything. They own all the important land. They own and control the corporations. They’ve long since bought and paid for the Senate, the Congress, the statehouses, the city halls. They’ve got the judges in their back pockets. And they own all the big media companies, so that they control just about all of the news and information you hear. They’ve got you by the balls. They spend billions of dollars every year lobbying—lobbying to get what they want. Well, we know what they want: they want more for themselves and less for everybody else.” The pundits say there is no audience for the old-school populism of a William Jennings Bryan or even a Franklin Roosevelt. Carlin proved them wrong, preaching American radicalism with punchlines every night before crowds that cheered (and laughed) as he struck mighty blows against the empire.

PASSIN’ THROUGH Creig Flessel, 1912-2008 Creig Flessel, a prolific illustrator active as a cartoonist and cover artist at the birth of the American comic book, died July 17, five days after suffering a stroke. He was 96 and lived in Mill Valley, California. Flessel was the most accomplished artist working in comics in the medium’s infancy. Many of the earliest comic book illustrators were has-beens on their way down or wannabes not quite good enough for prime time, but Flessel, at the age of 22, was producing flawless illustrations for Street & Smith’s pulp fiction, and at 23, he was doing stories and covers for Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s new line of comic books, destined, eventually, to be DC Comics. Here’s the obit by Gary Klien at the Marin Independent Journal in California: Flessel lived at The Redwoods, a retirement community, where he moved in 2000 from his native Long Island, N.Y. Last fall, at a ceremony in Mill Valley, Flessel was honored with the Sparky Award, named for the late Peanuts creator Charles "Sparky" Schulz, who lived in Santa Rosa. The award, inaugurated in 1998, is given to accomplished cartoonists in the western United States, and its recipients have included Gary Larson of The Far Side, Will Eisner of The Spirit, Gus Arriola of Gordo, and Sergio Aragones of Mad magazine. "Old cartoonists never die, they just go to California and receive the Sparky Award," Flessel joked at the ceremony. Flessel's work has appeared in classic comic books from the 1930s and beyond; old advertisements for companies such as Royal Crown Cola and Post Raisin Bran; magazines as diverse as Boy's Life and Playboy; and the David Crane comic strip. His work has also been exhibited at the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco. Even in retirement, he contributed artwork to the monthly newsletter at The Redwoods. A

longer and more insightful appreciation appears at Tom Spurgeon’s

comicsreporter.com.

THE

FROTH ESTATE The last hold-outs in the so-called news media have given up the struggle. The three major weekly newsmagazines, Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News and World Report, have at last joined the rest of their journalistical brethren as entertainers rather than informers. Nothing sudden about it: the transformation has been going on for years—with successive revampings of page design and refocusing of emphasis and the like. The last of the innovations before the wholesale conversion to divertissement can still be seen in the opening pages of each magazine which are devoted to short paragraph-long “articles,” amusing newsy squibs and bits accompanied by photos and drawings, all premised on the conviction that American readers, trained by commercials on tv, have the attention span of May flies and can’t be bothered to read anything more lengthy than a page. The laddie magazines are all built on this principle, and the newsmags, seeing the proliferation of the lads on the newsstands, decided, apparently, to go after the same readership by developing a “department” of shreds and patches. The maneuver, I confess, makes for interesting reading, fast and funny. (Despite my pose as an above-it-all Olympian observer of the American scene, I’m no better—and, I hope, no worse—than the rest of us: I, too, look for entertainment amid the news.) But the newsmags seem to have overlooked the basic ingredient of the laddie mags—skimpily clad wimmin of the embonpoint sort on the cover and in various full-page displays within. That’s next, I suppose, but until that Rubicon is crossed, the newsmags have decided to make themselves into more diverting enterprises with cover stories that pose as “news” under the subheading of “history.” The idea is that “history” informs the news of the day, expands upon it, puts it in context, and so forth. Newsmagazines have always done cover stories on trends and fads in our heppy heppy land, but now they’re delving into unabashed history and, even, literature. U.S. News led the way in this endeavor: its covers over the last years have increasingly brought our attention to some aspect of our history. This year’s Fourth of July issue (dated July 7-14 but on the stands several days earlier) featured “The American Revolution: Myths and Realities,” with a cover picture of George Washington. Fascinating stuff but “news”? Newsweek was the last to tumble: it’s “Summer Double Issue” dated July 7-14 proclaimed itself “The (Mostly) Big Thoughts Edition” with a cover portrait of Lincoln and Darwin. The cover story of Time’s July 14 issue is about Mark Twain. All mightily engaging stuff, as I said, but not the news of yesteryear. We apparently no longer want to know the facts of the day’s events; we want, instead, to be entertained with short forays into history. Let the revels begin. And while the festivities transpire, news expires. Mainstream news media have apparently sidelined stories that might, in another era of concerned journalism, have rated frontpage headlines, banners in screaming red ink. Reporters in the trenches are still at work, but what they report is often overlooked or ignored. Sharon Theimer at the Associated Press, for instance, reported lately that “U.S. exports to Iran—including brassieres, bull semen, cosmetics, and possibly even weapons—grew more than tenfold during President Bush’s years in office even as he accused Iran of nuclear ambitions and helping terrorists. ... U.S. trade in a range of goods survives on-again, off-again sanctions originally imposed nearly three decades ago. ... Sanctions are intended in part to frustrate Iran’s efforts to build its military, but the U.S. government’s own figures show at least $148,000 worth of unspecified weapons and other military gear were exported from the U.S. to Iran during Bush’s time in office, [including] $106,635 in military rifles and $8,760 in rifle parts and accessories shipped in 2004.” And

while the political reporting on every hand keeps harping on John

McCain’s citing “the surg” as a sign of the success

of George W. (“Warlord”) Bush’s policy in Iraq—with

McCain’s accompanying ridicule of Barack Obama’s refusal

to recognize the success of “the surg”—no one is

reporting that the reason violence has subsided lately in northern

Iraq has very little to do with military might and everything to do

with the Almighty U.S. Dollar. The insurgents in Iraq’s Anbar

province have stopped disturbing the peace in order to continue to

collect the salaries the U.S. is paying them to stop shooting at us.

As I mentioned earlier, the diabolical success of the GeeDubya Scheme

is going unreported: first destroy the country’s economy in

order to make its citizens dependent upon the invader’s

largess, and then put all the natives on the payroll. Footnit: A week or so after I wrote the first two paragraphs above, Brian Kelly, editor of U.S. News, announced that the magazine is planning to convert to an every-other-week publication schedule by 2009, claiming this will permit more in-depth analysis, the justification he offers in contemplating the cut-back in reporting straight news. “We stopped chewing over last week’s events years ago,” he says, deploying the disparaging verb of mastication as a way of consigning to inferiority the news of daily events, “—in order to give you more timely perspective and analysis,” he concludes, invoking a clutch of status words that purport to give important cultural standing to the magazine’s new scheme, which is, really, not a journalist’s plan at all but an entrepreneurial effort in the last ditch category to rescue the 75-year-old magazine from oblivion and death brought on by the Internet and apathy among the rising generation of citizens who don’t read, or buy, weekly newsmagazines or daily newspapers because they don’t think “news” helps them through their daily round of amusements and preoccupations. They should adopt Henry David Thoreau as a patron saint: asked once why he didn’t read any daily newspaper, the sage of Walden responded with insightful pith: “I read one once and am acquainted with the principle.” U.S. News will presumably continue its web presence, where its audience is “now more than 5 million people a month,” Kelly drones on. To abandon sarcasm for the nonce, Kelly and his magazine are attempting an end run around the Internet. They are forced to accept the hard fact that 24/7 cable tv news and the Internet can cover the news of the day with second-by-second up-dates as necessary much better than a weekly magazine can. They expect their website to continue to do the same, but they’re reluctant to abandon print, which they see not only as “a refuge from the din of the Web and cable tv” but as a way of engaging people in the events of their lives in ways “uniquely valuable.” And I hope they’re right.

EDITOONERY An

old one and a new one. Mike Keefe at the Denver Post has

established an

T-SHIRT INSCRIPTIONS Constipated people don’t give a crap. I’d agree with you, but then we’d both be wrong. I wonder if illiterate people get the full effect of alphabet soup? I know right from wrong—wrong is the fun one! If it weren’t for the gutter, my mind would be homeless. You look like I need another drink. Impotence—nature’s way of saying no hard feelings. I’m trying to see things from your point of view but I can’t stick my head that far up my ass. I have a perfect body: it’s your vision that’s shot. Where’s the Rapture when you need it? At this rate, I have enough saved to retire for a year and a half. Tell me your sob story: I need a good laugh. Honest is the best policy, but insanity is a better defense. With enough practice, living in a moral vacuum feels petty darn good. It’s all geek to me. Sign on fencepost: No trespassing—violators will be shot. Survivors will be shot again.

COMICS

PAGE WATCH In Borgman/Scott’s Zits, Jeremy has a new

girlfriend, who, with round head and large eyes, looks somewhat like

a fugitive from manga or the retro style of rendering. ... And in Candorville, Darrin

Bell’s take on Jesse Jackson’s

green-eyed assault on Obama is exactly right: an anonymous character

with a sack over his head (to preserve his anonymity) talks about the

misfortunes of his “friend,” saying: “My friend’s

leadership has made him the most important black man in America for

over 30 years, and now some punk-@%$ kid with big floppity ears comes

from nowhere and steals my—I mean, his—thunder.” He

gives his name as Smessie Smackson, as if we didn’t know. Bell

also did a four-day sequence in which George Carlin shows up in

Lemont’s dreams, concluding with the strip at the top of the

heap near here. Berk

Breathed’s Opus for July 6 didn’t make it into its syndicate’s flagship

newspaper: the Washington Post opted for a substitute, we learn at dailycartoonist.com, because,

according to columnist Gene Weingarten, “the editors felt it

might be insensitive to certain readers.” The next week in Opus, the hesitant penguin is awakened in the middle of the night by a corpulent CEO, who is there, in Opus’ bedroom, apparently to be “disciplined” by a scantily clad bimbo who enters the room with a star-spangled paddle in her grip, and the CEO starts undressing. I guess the Washington Post published this one: only fat CEOs or bimbos in their scanties would be offended. ... In Scott Adams’ Dilbert, Dogbert the Time Management Expert spouts this gem: “Never put time into an activity that has no potential benefit,” he says, then, looking at the pyramid-haired woman next to him, he continues: “For example, why bother putting on makeup if you’re going to wear that hideous outfit? That’s like knitting a sweater for a dead squirrel.” Love the simile. ... In Darby Conley’s Get Fuzzy, Bucky the cranky cat is “monkey-proofing” the apartment by hanging a bucket of syrup over the door. Rob calls it a booby trap, but Bucky corrects him, saying: “It’s really more directed at the head area,” thereby turning an otherwise innocent slang word into a less innocent one. ... In Terri Libenson’s Pajama Diaries, husband Rob has a vasectomy, just one more instance of Libenson’s continuing forthright foray into marital sex. ... And Stephen Pastis on Sunday, July 27, arranges an entire sequence of exposition in Pearls before Swine in order to reach this terminating speech by Pig, who has just interviewed Mr. Crumb: “Mr. Crumb’s conundrum of the humdrum of being mum and eating plums like a numb bum from some slum or drum and strum or hum with rum if dumb.” Rat, after this disaster, tells S. Pastis: “You’re a nausea-inducing embarrassment.” But Pastis, nonplused, says merely: “Sick Tum? Come, have some gum.” Ouch.

Fake

Comic Strip Progresses to Fake Animation and Hence to Fake Life Get

Your War On (GYWO), the popularity of which

is a stunning manifestation of the collapse of artistic integrity in

favor of sheer smart aleckry (the most trusted coin of the realm

these days), will soon be animated at 23/6.com, “a leading

comedic news site” according to a press release from Soft

Skulls Media (which is as good a name for this kind of media as I

could imagine). Emerging in the wake of 9/11, GYWO is an unabashed impersonation of a comic strip: it is manufactured by David Rees, who pastes

1980s-style clip art into a succession of panels and then gives the

depicted persons things to say. This comic strip imposter “became

a minor phenomenon” because of the comedic disparity between

the pictures and the words. The clip art depicts as blandly as

possible (because clip art, to be useful at all, must be universally Rees, who must take the blame for this perversion of the art form, said: “When 23/6 approached me about animating GYWO, I was skeptical they could do justice to my brilliance. However, they assured me I wasn’t actually that brilliant. Ever since that revelation, I’ve enjoyed breathing life into my beloved clip-art characters. The [proposed] animations will be like Hobbes’ conception of life in the state of nature: ‘nasty, brutish and short.’” Brian Spinks, director of video content for 23/6, thinks the website has achieved a “real coup” in securing Rees’ cooperation. “His sensibility is a perfect fit for us,” Spinks said, committing unwitting self-satire, “combining informed outrage with a true sense of the absurd. And we’ll be turning these videos around quickly, so they’ll have the immediacy of a daily editorial cartoon but with the rich media experience people are used to on tv and online.” I’m not sure how rich an experience the animated GYWO will induce. If the animation is to be faithful to the original, it will doubtless consist entirely of the sort of movement that is achieved by moving a camera back and forth from close-up to mid-range and back, focused all the time on the same static image, exactly what “happens” in the example we’ve posted here—a fairly typical instance. But, no. The animation for 23/6 will be something more enlivened than mere changing camera distance: it will have “the distinctive look of the work of Flat Black Film’s Bob Sabiston, who brought rotoscoping to the Richard Linklater film, ‘Waking Life.’ “Sabiston’s software lets animators trace over live-action footage easily and quickly to create comics that are amazingly life-like.” Rotoscoping is notorious among genuine animators for the stilted motion it produces: rotoscoped movement seems to take place in a dream. Or a nightmare. Or while waist-deep in a pond of thick mud. So, it would seem that the “animated” GYWO will begin by filming real people, then reducing their authentic live-action motion to awkward wooden movement by tracing, or imitating, that movement with hand-rendered lines. Let me see if I’ve got this right. A ringer of a comic strip the pictorial element of which is made up of cut-outs of the most innocuous and undistinguished drawings available without cost will be given stilted movement by faking the animation with a rotoscope thereby producing images that are, despite a herky-jerky motion, “amazingly life-like” but not, actually, of living people at all. A perfect crescendo of clip-art artistry—veritable soap-opera symbolism, fake to fake to fake. But

Rees sounds like an okay guy. I like his sense of humor even if I

detest and disparage the method he has chosen to display it. And his

satirical sensibility apparently springs from genuine human empathy:

the sale of two volumes reprinting GYWO has raised almost $100,000

for land mine removal in western Afghanistan. Nothing fake about

that.

CIVILIZATION’S

LAST OUTPOST Much as I’ve enjoyed Tony Snow in his role as Presidential Press Secretary—and admirable as he proved in extremis and, judging from what others who knew him well have said, in the everyday conduct of his life—I’m not sure he rated the state funeral that a Presidential eulogy created. Although he had been a working journalist at various times, Snow was known chiefly as a conservative commentator, not as a journalist in the same sense as Tim Russert or, say, Walter Cronkit. And as Press Secretary, the role in which he truly shined—after the wholly repressed Scott McCellan, Snow was purely irrepressible as a pushback jousting target, great entertainment—he was a shill for George W. (“Whopper”) Bush and Darth Cheney, a mouthpiece: his job was to lie to the press and make them like it. And he did that very well. He did it with good humor and enviable panache. When he died, Fox News went apoplectic. Hours of eulogy and remembrance—for a mouthpiece!!! If Russert hadn’t gotten so much weepy press two weeks before, would the conservative delegation have felt right about lauding Tony Snow so much? Nice guy, no question, but a state funeral? What is left for the right wing to do when Rush Limbaugh shakes free of this mortal coil?

DUTCH CARTOONIST JAILED FOR INDECENT CARTOONS One morning last May, the Amsterdam constabulary showed up at the door of the apartment of a “skinny cartoonist with a rude sense of humor,” arrested him, and took him off to spend that night in jail. The cartoonist’s crime was that he was suspected of sketching offensive drawings of Muslims and other minorities and posting them on his website, gregoriusnekschot.nl/blog (his only venue: newspapers and magazines shun his work as too extreme; and the website may not be fully functional these days, as the cartoonist awaits his legal fate). Actually, the cartoonist, whose nom de plume is Gregorius Nekschot (Dutch for “shot in the neck”), did draw cartoons that might be deemed offensive by various personages, and he takes considerable pride in his work: “Harmless humor does not exist,” he says, “—I like strong stuff.” What was at issue was not whether he drew such drawings but whether they were, as alleged by an Internet monitoring group, illegal under a Dutch law that forbids discrimination on the basis of race, religion or sexual orientation. The law was enacted, I gather, in the wake of Muslim outrage over the Danish Dozen, twelve cartoons published in the fall of 2005 by a Danish newspaper, one of whose editors, Flemming Rose, initiated their publication in order to test the limits, or extent, of freedom of expression in an emerging European climate of religious intimidation by Islamic extremists who protest, sometimes violently, any criticism of their religion. In Holland, a polemical filmmaker named Theo van Gogh was murdered in November 2004 because he made an anti-Islamic film. Elsewhere in Europe, a stage production and a museum exhibit have been cancelled for fear of inciting the radical elements of growing Muslim populations. In Denmark, the government has been protecting the Danish cartoonists whose caricatures of Muhammad brought destruction and death to the streets of Mideastern cities in the winter of 2006. In Holland, however, the government has apparently reacted to the intimidation by attempting to rein in cartoonists and other creative people. “Denmark protects its cartoonists; we arrest them,” said Geert Wilders, a populist member of the Dutch Parliament famous for denouncing the Quran as an Islamic version of Hitler’s Mein Kampf and, more recently, for releasing on the Internet a film, “Fitna,” which continues his blasphemous crusade against Islam. Under suspicion since 2005, Nekschot, “a fan of ribald gags” that often feature the Quran, crucifixion, sexual organs and goats, may have been arrested in May as part of a government effort to soothe Muslims angry about Wilders’ film. The authorities, however, claim it simply took them three years to figure out the cartoonist’s true identity and whereabouts. Nekschot was released the next day and has yet to be charged; his arrest, authorities now admit, was probably a “mistake.” It was certainly a political and public relations gaffe of certifiable magnitude, arousing public indignation throughout the country, which “sees itself as a bastion of tolerance.” And then, adding decibels to the furor, the Justice Minister, when grilled about the Nekschot case, inadvertently revealed the existence of “a previously secret bureaucratic body, called the Interdepartmental Working Group on Cartoons,” which, officials hastened to explain, had been established after the Danish Dozen crisis of 2006 to “alert Dutch officials to any risks the Netherlands might face” but had no official censoring duties. Maybe not, but it looks strangely like the thin edge of the censor’s wedge to me. The menace of the Nekschot case is reported in detail in the Wall Street Journal in a July 12 posting, “Why Islam Is Unfunny fo a Cartoonist,” by Andrew Higgins, who writes: “How to handle Muslim sensitivities is one of Europe’s most prickly issues. Islam is Europe’s fastest-growing religion, with immigrants from Muslim lands often rejecting a drift toward secularism in what used to be known as Christendom. ... The contrasting Danish and Dutch responses ‘show that there is a serious struggle of ideas going on for the future of Europe,’ says Flemming Rose. ... At stake, he says, is whether democracy protects the right to offend or embraces religious taboos so that ‘citizens have a right not to be offended.’” Everything in the foregoing report is taken from Higgins’, occasionally verbatim.

AMERICAN CARTOONIST JAILED FOR INDECENT CARTOONS Beverly Dwaine Tinsley’s training for a career in cartooning was scarcely auspicious. Born in Richmond, Virginia, to a couple of trailer-trash alcoholics on December 31, 1945, he was three months old when he lost his father: the paterfamilias deserted his family after catching the materfamilias in bed with another man. She subsequently opened a beauty parlor and spent her evenings picking up stray men in bars, taking her children, Dwaine and Donnie, two years Dwaine’s senior, along because she didn’t know what else to do with them. She married another alcoholic when Dwaine (he hated the name Beverly) was nine. He spent much of his youth in the care of his maternal grandparents, where he and his brother were dumped for long stretches when his mother felt her amusements were too much interfered with by the presence of her offspring. He was arrested often as a juvenile and spent time in several reform schools. He dropped out of high school at seventeen and, with a friend, moved to Washington, D.C., where, during a couple of homeless years, he supported himself and a drug habit “with odd jobs, petty thefts, housebreaking, and being paid by men to allow them to orally copulate him.” He was arrested in November 1965, and the following March, he was convicted of burglary and sentenced to six years in the Maryland state penitentiary. He got out in less than four. During his incarceration, he survived 15 months in solitary, read extensively, earned his GED, took a college course in sociology by mail, and decided to become a cartoonist, a career he avidly pursued upon release from prison. He’d doodled most of his life and later recognized that drawing had given him a way to cope with the miseries of his daily existence. Dwaine knew nothing about how to freelance cartoons to magazines, but editors instructed him in the prescribed method: submit rough drawings on 8.5x11-inch sheets and include a stamped, self-addressed return envelope. Working a succession of menial jobs, he survived a long apprenticeship without selling anything, but by 1974, his cartoons were appearing in such magazines as Adam, Chic, Penthouse, Playboy, and San Francisco Ball. By then, he had married, on June 20, 1969, a Richmond secretary named Charlotte Lambert, and they’d produced a daughter, Veronica, who was born in October the next year. Late in 1974, Tinsley sold his first cartoon to Larry Flynt’s nefarious skin magazine, Hustler, which, at the time, had been publishing for only two years out of Columbus, Ohio. Flynt liked Tinsley’s work so much that he was signed on as a “contract” cartoonist: he agreed to give the magazine “first look” at any of his male-interest (sex and alcohol) oriented cartoons, and Hustler, in turn, guaranteed him two full-page color cartoons in every issue, at $350 each. He could still submit to other magazines, except Hustler’s rivals, any cartoons Hustler rejected as well as cartoons on subjects Hustler wasn’t interested in. About 18 months later, Tinsley drove to Columbus from his new domicile in Los Angeles, sleeping in his car en route, to apply for a job. Flynt, impressed by Tinsley’s foolhardy aspiration, hired him as cartoon editor. Tinsley accepted the job and got married again. He’d divorced Charlotte in February 1974, having taken up with Debbie Melhew, a pretty-faced blonde weighing over 250 pounds, before they both moved to Los Angeles, “the center of the adult world.” Tinsley hired his new wife as his assistant and commenced a career that would be as notable as his training had been ignominious. In

the February 1976 issue of Hustler,

Tinsley introduced the world to Chester the Molester, “a

leering, overweight, blond fellow, dressed in saddle shoes and

herringbone slacks, who carried a baseball bat and craved

prepubescent girls.” For his debut, Chester had a hand puppet

on his pecker and was inviting a young girl to “give widdle