|

|||||||

|

Opus 210 (September 2, 2007). Just

Good News this time, kimo sabe—which is to say, in that pearly axiom of old, No

News At All. We’re still unpacking boxes at our New Abode at the foot of the

Rockies. But we do have a few tidbits worth chewing on this time, to wit—in

order, by department:

GRAPHIC NOVEL

REVIEWS

The Black Diamond Detective Agency

The Professor’s Daughter

Another Review

The Artist Within—Photographs Galore

Me and Sparky

BOOK MARQUEE

Bill Mauldin’s Willie and Joe Again

Rancid Raves Gallery

Preston Blair’s Strutting Red Riding Hood

Some Manga I Like?

BEGINNINGS

AND ENDINGS

An Excerpt from the Milton Caniff Biography

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate

the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can

print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your

leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

GRAFIX NOVELZ

Two Reviews

Gaby Mitchell’s script which Eddie Campbell has

crafted into a graphic novel entitled The

Black Diamond Detective Agency (138 6x9-inch pages in color; First Second,

$16.95) would have made a good movie: the story offers at least two explosions

and a couple of gunfights and several bloodlettings, plenty of the kind of

visual excitement currently in vogue among movie producers and viewers. And

given the capacity of the comics medium for conveying excitement in visual

terms, Mitchell’s story should have translated handily into graphic novel

format. Campbell’s pictures are suitably exciting: his command of color alone

enlivens the pages, and he enhances the narrative with breakdowns and page

layouts that focus on key events, supplying both dramatic impact and emphasis.

Unhappily, Campbell’s distinctive drawing style is translated here into a kind

of splashy slapdash approximation of the lively sketchiness of his customary

penmanship. While it yields handsome artwork, this mannerism makes following

the story difficult: Campbell’s treatment of faces, for instance—never notable

for clarity—often reduces faces to mere daubs of color in a medium that

requires precise linear definition in support of the story. Many of the

characters are unrecognizable from panel to panel, let alone page to page. This

unfortunate byproduct of Campbell’s otherwise pleasing graphic technique is

compounded by a story so brimming with male characters that not even the vast

array of facial hair fashions of the late nineteenth can render distinctive,

and seen at a distance, essential to various scene-setting passages, all

moustaches look pretty much alike. And to make matters worse, if possible, one

of the two main characters in this tale assumes a variety of guises and names.

Finally, the story itself is extraordinarily complex, and Mitchell’s script is

fashionably terse: we sometimes go for pages, following willingly enough,

before the characters, speaking in a realistically cryptic manner, let drop a

fact that conveys enough information to illuminate several of the pages that

have gone before. I realize that elliptically spare dialogue, aimed at

conveying a sense of reality as we all know and live it, is all the rage these

days, and comics generally are better for it. The medium relies more and more

for its meaning upon what characters are portrayed saying and doing than on the

tedious drone of expository captions, the mode of yesteryear. Stories are more

life-like, more realistic---and therefore more dramatic. More like movies. But

without expository captions in comics, the pictures must carry a greater share

of the narrative load, and to do that, they must be models of clarity. Faces,

the font of individual identity, must have clearly defined features in order to

be readily discerned. Campbell’s visuals, for all their considerable panache,

are not models of clarity; they are models, rather, of technique.

Mitchell’s

story, while engaging enough, is probably beyond rescuing whatever techniques

Campbell might bring to telling it. We come in as Jackie Hardin’s wife, Julia,

is telling him he must move on: “It’s been two years,” she says, “and she’s not

coming back.” Fourteen pages later, we realize that the missing female is

probably Jackie and Julia’s daughter, Corrine, who died at the age of three. We

don’t know what she died of or why; it’s a mystery which has nothing to do with

the rest of the story. Hardin’s depression, however, probably drives his wife

to leave him, and he spends a portion of the ensuing narrative trying to find

her. But en route, he becomes involved in a manhunt aimed at finding the

persons who blew up a train. Initially, Hardin, who was present for the

explosion and is depicted helping the survivors, is suspected, by the Black

Diamond Detective Agency, of being the bomber. He escapes and grows a beard, a

conspicuously blond one (by which we, but not the detectives, can identify

him), and then, hoping to clear his name by finding the real culprits, he joins

the Agency, none of whom, as I say, are apparently discerning enough to see

that behind his beard, “Collins,” as he now calls himself, is actually Hardin.

In fact, by way of applying for the job, “Collins” nearly confesses to being

Jackie Harte, once the shooter for the Reno brothers gang. Before they can find

the Reno brothers, however, the Agency receives word that the Emerson gang is

coming to town, and they all flock down to the depot and, after shooting up the

gang and getting shot plenty themselves, they apprehend the survivors, one of

whom is unaccountably pale. Somehow, this leads to the speculation that the

Reno brothers are holed up in a coal mine where they never get any sun and are,

hence, all uncommonly pale. Some of this makes a little more sense in the

novel, but not much more. The Agency operatives raid the mine and kill everyone

or take them prisoner.

The

Reno brothers, it seems, blew up the train in the opening incident of the story

in order to obtain quires of special paper that can be used for counterfeiting.

And they, in turn, are in the employ of an international cartel anxious to

delay the United States’ emergence as a world power by sabotaging its economy

with vast quantities of bad money. The Emerson gang comes to town to exchange

the swag from their latest bank robbery for a packet of bad money in the same

amount, which bills will be returned to the bank and circulated generally until

they are discovered to be phoney, thereby sinking the American economic ship. A

fantasy worthy of the present-day Bush League, but enough to hold the events of

this story together, albeit just barely—and only for the most indulgent reader.

Just before all of this is disclosed in the best Edwardian drawingroom

expository manner, the head bad guy, who, all along, we’d supposed was a good

guy, releases Hardin’s missing wife—who he is holding captive for some vague

reason—and the two are reunited to the loud clanging of deus ex machina. Then the bad guy explains everything, except the

mute detective Carl, and leaves, stage left, only to be shot by a sniper, a man

named Phillips, who, we had been led to believe, was a member of the Agency. Or

the Secret Service. One or the other, but certainly not in the international

cartel, which, of course, is what he may be, protecting their interests by

killing the blabbermouth. Or not. He’s probably Secret Service. In any event he

is wholly unscathed at the end of the book, but we don’t care much, because

Hardin and his wife have been reunited.

The

story includes one gratuitous sex scene between one of the lower orders named

Weasel and a nearly naked prostitute. Hardin calls upon them, hoping Weasel can

tell him where Reno is. But this goes nowhere. Except that we get to see a

picture of the rotund bum of a big fat prostitute nearly naked with a

bullethole in her head and her naked bosom splattered with blood. Equally

pointless is a letter ostensibly from Julia to Frank, who, we find out, is

Frank Reno. But it’s not altogether clear why Julia would be writing him,

although something passing for explanation is committed in due course. The book

is littered with vagaries of this sort. Carl the mute is a detective in the

Agency who stopped speaking ten years before when his brother was killed. A

mark of good fiction is that when a seeming irrelevant fact is introduced, that

fact is, eventually, deployed in the service of the story and in the unraveling

of the plot, proving to be not irrelevant at all but the key to the denouement.

Thinking we are in the hands of a competent storyteller, we expect to learn

more about the cause of Carl’s silence and how that—or his brother’s death—fits

into the whole scheme. Was his brother killed by Frank Reno? Jackie Harte?

Weasel? The fat prostitute? But we never find out. Other details are similarly

purposeless or just flat baffling. And sometimes Hardin’s beard isn’t blond but

black, depending on how far he is from Campbell’s camera.

Some

visual passages are masterfully executed. A few of the locales are In The Professor’s Daughter (80 6x9-inch

pages in full color; First Second, $16.95), we have something entirely

different. It is a love story, pure and simple Well, maybe not so simple: the

professor’s daughter, Lillian Bowell, is in love with Prince Imhotep IV,

would-be Pharaoh of Egypt, who, by the time of this Victorian era tale, has

been dead for 3,000 years. But he’s extraordinarily well preserved: he’s a

mummy in the collection of Lillian’s father, a noted Egyptologist. Meanwhile,

the IV takes after the ship in a rowboat, furnished by an obliging antiquarian

named Bartholomew Rodgers. The absurdity of chasing after a sea-going vessel in

a rowboat is an exquisite touch, another signal that reality has no business

intruding itself upon a love story. No matter: when it starts to rain, they row

back to port. Imhotep III brings Lillian back, but when Imhotep IV confesses

his love for her, she leaves and turns herself in to the police. A trial

ensues, and while that is transpiring, the III storms Buckingham Palace and

kidnaps Queen Victoria on the supposition that she can pardon Lillian. The III

has inadvertently killed Lillian’s father and is carrying him around,

apparently to no purpose. But when Victoria proves uncooperative, the III dumps

her in the Thames (Bartholome Rodgers comes to her rescue) and goes to the

Tower of London, where Lillian is imprisoned. He gains her cell, where the IV

is visiting. Dumping Professor Bowell’s body on the floor, the III engineers an

ingenious escape for the lovers: he commands his son to remove his wrappings

and put them on the deceased Professor and then don the Professor’s clothing. The

trio of miscreants then depart the premises, leaving the corpse of the

Professor to take the, er, rap. Imhotep IV marries Lillian and they have three

children and, on the book’s last page, they visit the museum where they view

the mummy—who, we know, is not Imhotep IV but Professor Bowell. And it all

seems, as it usually does—and always must, in love stories—perfectly okay. The

message in such tales is, after all, that love conquers everything in its

stampede to happily ever-aftering.

Emmanuel Guibert renders this adventure in a wholly straightforward manner, no fancy camera-work or obscuring chiaroscuro. His simple outlines, however, are drawn in colors that match the colors they are outlining. And the bold linear treatments are enhanced with delicate coloring: varying hues impart to every picture subtle nuances that produce a visual depth and the necessary illusion of actual people cavorting through real locales. Pages are laid out in uniform three-tier grids, varied rarely and always for mood or to convey essential visual detail. Backgrounds and settings are drawn with meticulous detail, a trait I’ve always admired among European cartoonists who seem effortlessly to meld big-foot figures with little-foot realism in locales and props. (“Little foot” as an antonym for “big foot”—the latter often invoked to describe cartoony mannerisms in contrast to illustrative realism—is the invention of cartoonist Chuck Fiala, a practicing master of big footery as well as visual tom foolery.) Here are four scenes, four separate pages, from the tale.

I’m

being blatantly unfair in comparing Guibert’s artwork in The Professor’s Daughter to the detriment of Campbell’s in Black Diamond: the latter tale is an exercise in gritty realism; the

former, a light-hearted scamper. Guibert’s style, although deliciously enhanced

and thereby complicated with subtle coloring, is still a simple style, and its

simplicity produces stark clarity, a narrative essential that I find lacking in

the more complex illustrative manner of Campbell in Black Diamond. But Guibert’s manner of drawing, which so perfectly

suits a fantasy about the love between a mummy and a proper Victorian heroine,

would be somewhat out-of-place depicting Jackie Harden’s adventure, which,

despite the love story that begins and ends it—and survives it, emerging, at

last, as the raison d’etre for the

novel—is an uncompromising tale of cops and robbers, seriously told. It demands

an illustrative style of the sort that Campbell is capable of producing. Here,

however—momentarily seduced, no doubt, by color illustration into the vagaries

in ruffles and furbelows that often accompany the application of color—Campbell

falls short of his usual precision and clarity. Europeans have shown repeatedly

that a cardoon manner can successfully depict a serious life-and-death story;

but that technique cannot achieve the grim grittiness that Campbell aims for in Black Diamond.

The Professor’s Daughter, appearing initially

in France in 1997, was the first collaboration between Sfar and Guibert, and in

their subsequent partnering, Sfar is often the visual artist, as in The Sardine in Outer Space series. They

have each performed solo, too: Guibert in Alan’s

War (forthcoming from First Second); Sfar in The Rabbi’s Cat from Pantheon and in Klezmer and Vampire Lovers—all,

except Cat, available from First

Second, as is Campbell’s The Fate of the

Artist.

A Propos of Nothing Much

“There is nothing which has yet been contrived by man

by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern or inn.” —Duston

Barswig, quotting Samuel Johnson

SEEING THE

ARTIST WITHIN FROM WITHOUT

A Book of

Pictures Worth Pondering

Photographs of cartoonists at their drawing boards,

the traditional albeit worn-out pose for this breed of pencil-pusher, may be

the average lensman’s idea of visual monotony, but Greg Preston is no one’s

average and proves it by producing nearly 100 photos of cartoonists, in their

studios near their drawing boards if not actually seated at them, and no two

are alike. And yet, there is little artifice on display: they all seem quite

natural even if quite obviously posed for the camera. The entire menagerie is

showcased in a very elegant coffeetable book from Preston via Dark Horse, The Artist Within: Portraits of Cartoonists,

Comic Book Artists, Animators, and Others (208 12x12-inch pages in

hardcover; $39.95). Years ago, if memory serves, Preston ambled up to my table

in Artists Alley at the Sandy Eggo Con, showed me a couple of his photographs

of celebrated cartooners, and asked me what I thought about his plan to devote

an entire book to such pictures. I’d like to say that I told him I thought it

would be great, but it’s probable that in those years, I masked my enthusiasms

under a false face of sanfroid and said only, “Sounds interesting,” or

something equally noncommittal. If asked now, having seen the manifestation of

his vision, I’d bubble over with excited appreciation and

glorification—“Tremendous!” I’d exclaim. And so I do, herewith: tremendous!

The

gigantic pages of the book give ample display to Preston’s skill: each

cartoonist is pictured in a full-page size photo, bleeding on all four sides,

on the right-hand page of a two page spread; the left-hand page presents a

single sample of the cartoonist’s work and a short biography, floating in an

ocean of white space that contrasts nicely with the graduated grays and blacks

of the facing photo. A sumptuous visual feast, no quibble about it.

Exactly

102 cartooners of one kind or another are pictured, plus a couple of

hangers-on—Scott Shaw’s young son

Kirby and Kevin Eastman’s wife Julie

Strain. The order of their presentation is almost random, beginning with the

King of Comics, Jack Kirby, and

ending with the Emperor of Theatrical Caricaturists, Al Hirschfeld, who didn’t like to be called a “cartoonist” (he

preferred “characterist”) but who nonetheless accepted a Lifetime Achievement

Award from the National Cartoonists Society in 1995. The other half of the legendary

Simon and Kirby team, Joe Simon, is

also pictured, about halfway through the volume. Here’s Arthur Adams in his stockingfeet and Tony Millionaire in his bare feet. And here’s a picture of Frank Miller, watching the drawing he’s

doodling on his drawing board and therefore not glowering malevolently into the

camera; Michael Kaluta, crouched at

his drawing board and looking more like a leprechaun than an artist; Alex Toth, almost disappearing into the

shadows as befits a reclusive genius; and Morrie

Turner, the only African-American in sight. Only ten women herein, one of

whom, Olivia De Berardinis, though

scarcely a cartoonist, is noted for “good girl art,” which, by being a

distinctly comic book genre, secures her a place in these pages. She had this

to say about her work, famed for its female embonpoint: “My art, popularly

referred to as pin-up, is a form of burlesque, only in paint. Now I get to

perform my art in the pages of Playboy monthly, with Hef writing the punch lines; I throw him curves, he hits them out

of the park.” Here’s Al Williamson, looking

marvelously fit and brash; I can almost hear him utter some ludicrously crude

profanity, as was his wont, masking his essential modesty and insecurity. He

was always amazed at the ardor of his fans’ admiration at cons. J. Scott Campbell stands far back in

the photo; Joe Kubert is right in

your face. Both Marc Silvestri and Jim Lee are pictured in studios with

other artists laboring anonymously in the backgrounds.

What’s

in the backgrounds and foregrounds is almost as interesting as the faces of the

’tooners. A floppy clown hat is tucked in the corner of the foreground of the

photo of Gahan Wilson. A rolodex is

conspicuous at Art Spiegelman’s elbow. Sergio Aragones is crouching over

several figurines depicting characters from Groo, and on the shelf behind him,

a flock of Donald Ducks. A tiny “action figure” of the Spirit stands at the top

of Will Eisner’s drawing board. Broomhilda’s Russell Myers stands at his drawing board, and on the bookcase in

front of him is a sign taken, doubtless, from a bank: “Payments Made After 4:30

p.m. Receipted Next Day.” The studios themselves vary a good bit. Stan Sakai is working in a spare

bedroom, it looks like—although he assures me it isn’t; and Berk Breathed seems to hang out in a

tunnel of some sort. Patrick McDonnell sits with a dog in his lap in the middle of a meticulously tidy studio with

windows all around that look out into a leafy forest; Mark Schultz also works in a studio with window surround. Victor Moscoso works in a tiny,

cluttered space, in vivid contrast to the airy albeit cluttered openness of Jules Feiffer’s studio on the next page

(with a plaque bearing the signature of Milton

Caniff conspicuously in the background). The studio of the Bros Hernandez, Gilbert and Jamie, seems much too orderly, but a tell-tale scrap in one corner of the picture

betrays them: they’ve tidied up the place for the photographer. Most are

smiling; only Dave Berg and Rick Detorie (of the comic strip One Big Happy) mug for the camera.

Some

are decidedly not in a studio. Robert

Crumb is in a booth at some greasy spoonery, and Moebius is at the beach. Ed “Big Daddy” Roth is crouched by a hot

rod chassis; Howard Chaykin is in

his library; Bill Stout, in a museum

with dinosaurs; Barry Windsor-Smith, on a staircase. But here’s Gus Arriola in the second-floor studio I know pretty well; ditto, Eldon Dedini (my photo of him at his drawingboard is taken from

almost the same angle) (well, that’s scarcely improbable: it’s a pretty small

room without many angles).

Informative—even

insightful—as the photos may be, the book as a whole is a font of images that

will inspire reverie, not analysis. And reverie is a good place for the

imagination to visit.

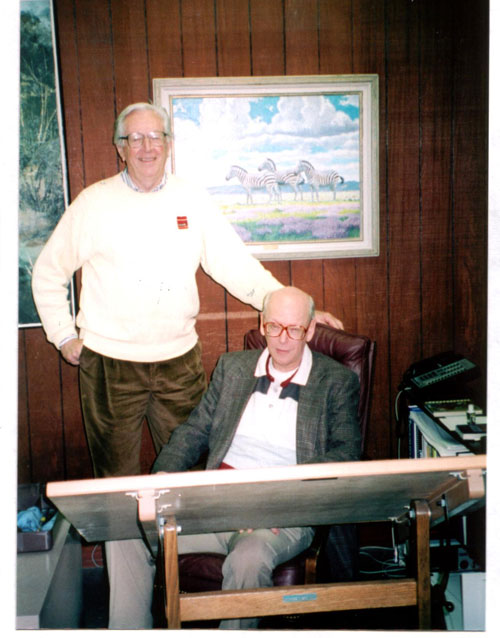

Speaking of photographs, here’s a souvenir of my only

encounter with the famed Sparky.

“It’ll be funnier this way,” Charles Schulz said. We

were in his studio in Santa Rosa, and our mutual friend, collector Mark Cohen,

was about to take a photograph of us. Schulz and I were discussing the pose we

should assume.

Mark

had arranged for me to meet the creator of Peanuts during my visit in the winter of 1998. We had lunch with Schulz that day in the

coffee shop of the cartoonist’s renowned skating rink, and after lunch, Schulz

took us to his studio. When it came time to leave, I asked if he’d mind posing

with me in a photograph. And so we moved over to his drawing board for the

photo.

“Sit

here,” Schulz said, gesturing toward the chair at the drawing board.

“No,”

I said, “you should be seated at the drawing board, and I should be standing

behind you—the classic albeit trite pose of cartoonist and fan.”

“No,”

he smiled, “you sit here and I’ll stand behind you. It’ll be funnier this way.”

You

can’t argue with a man who has been making people laugh for nearly fifty years.

You have to assume that he knows what’s funny. I sat. He stood. Mark took the

photo we’ve just seen.

It

was funnier Sparky’s way. I look thoroughly ill-at-ease and therefore funny.

Later,

remembering the worn place in the center of that drawing board, I realized this

was the drawing board Schulz had been using ever since he bought it with his

first paycheck from the Art Instruction correspondence school in Minneapolis,

where he went to work after his military service in World War II. I wish I’d

remembered this at the time: if I’d realized I was seated at a shrine, not just

a drawing board, I’d have been even more ill-at-ease and therefore even

funnier.

READ AND RELISH

Political

Action, Not Now

“The closest these kids come today to civil

disobedience is making dinner reservations and not showing up.” —Bill Maher

“When

a fellow says it hain’t the money but the principle o’ the thing, it’s th’

money.—Abe Martin

BOOK MARQUEE

Bill Mauldin's WWII Cartoons to Be Collected in

Two-Volume Set

(Lifted,

bodily, from Editor & Publisher online,

July 24, so it’ll be Olde Newsy by the time you read this, but I obey my

Mauldin-loving compulsions anyhow.)

More than 600 of Bill

Mauldin's World War II cartoons—many never reprinted before—will be

collected in a two-volume set that Fantagraphics Books is publishing this

February (2008). Willie & Joe: The

WWII Years totals 650 hardcover pages. It's edited by Todd DePastino, whose

biography of the cartoonist— Bill

Mauldin: A Life Up Front—is also slated to be published that same February

by W.W. Norton. Mauldin (1921-2003) used his Willie and Joe characters to

comment on World War II through the eyes of average soldiers. The WWII veteran

won a 1945 Pulitzer Prize for those United Feature Syndicate cartoons, and won

another Pulitzer in 1959 while with the St.

Louis Post-Dispatch. Mauldin, who also worked for the Chicago Sun-Times, was syndicated by King Features for much of his

career. Fantagraphics plans to publish several other volumes of the cartoons

Mauldin did until his 1991 retirement. By the way, although not at all

incidentally, I converted my obit on Mauldin to a monograph, repleat with

numerous illustrations from his oeuvre,

a stunning production even if I do say so myself. (And if not me, who?) If

you’d like a copy, drop me a note via Email (at the end of the scroll) and I’ll

tell you where to send five bucks ($5) for your very own copy.

RANCID RAVES

GALLERY

In our perpetual campaign to enliven the comics world

with marvels that have, somehow, escaped fame or notoriety, here are a couple

fugitive fragments for your delection. First, a portion of the storyboarding Preston Blair did of the exotic dancer

in that Tex Avery animated cartoon

in which the Wolf goes ga-ga over a Red Hot Riding Hood; lifted from Walter

Foster’s “how to” booklet on animation.

BEGINNINGS

AND ENDINGS

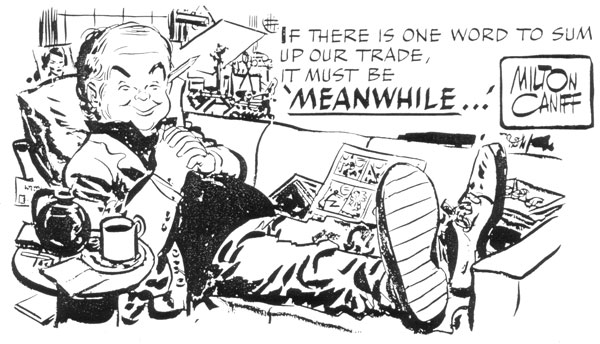

Milton Caniff

did Terry

and the Pirates for the Tribune-News

Syndicate for twelve years, ending in 1946. In 1947, he launched Steve

Canyon, which he would produce for over

forty years. In this excerpt from my Caniff biography, we see what brought the

Caniff Terry years to an end and

inaugurated the Canyon years.

The summer of 1944, the Tribune-News Syndicate

renewed Caniff’s contract for another two years. The terms remained the same as

always: he’d be advanced $50 a week against royalties for the daily strips and

another $50 for the Sunday page. His royalties would be commensurate with the

strip’s circulation, and he’d earn twenty percent of all revenues from

licensing and merchandising the characters. By this time, the cartoonist’s

annual income from all these sources was over $80,000. The strip was appearing

in about 250 papers, but its wartime theme and its military audience catapulted

it into visibility beyond its usual precincts. After conducting a national

readership poll in the fall, Esquire magazine announced that Terry and the

Pirates was the fifth most popular comic strip in the country. As a

prestige-earning commodity alone, the strip was worth a small fortune to the

Syndicate. Still, contractually speaking, Caniff was working for a paltry $100

a week—the same amount he’d been paid as a starting rate ten years before when

he’d been signed up as a virtually unknown and unproven talent. It rankled. It

rankled that he had accomplished so much and was being accorded so little.

Although

he gave the matter little thought at the time he signed his renewal contract, later

that fall, he was made suddenly conscious of the beggarly inequity of his

almost perfunctory arrangement with the Tribune-News when he was unexpectedly

offered a much more generous alternative. It was an offer that made an

appropriate allowance for his talent and professional stature and for the

popularity and value of his work. It was an offer that would change his career

and his life.

“One

day I got a call from a man I had never heard of,” Caniff said. “And he asked

me could I come and see him at such-and-such a time in such-and-such a suite at

the Waldorf. And I thought, If he can afford a suite at the Waldorf, I’d better

find out what he wants.”

The

suite at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel was a hospitality suite being operated by

the Chicago Sun, and the man Caniff

had never heard of was Smith Davis, a dealer in newspaper properties. Davis

wasted no time in getting to the point.

“I

represent Marshall Field,” he said. “As you know, Mr. Field has been fighting

to get his paper established in Chicago. He needs top-notch features in order

to compete with the Chicago Tribune,

which has Dick Tracy and Little Orphan Annie and, of course, Terry. He would like to talk to you

about doing a strip for him. He knows all the technical problems—that you

couldn’t do Terry and so on—so it

would be a brand new strip. Are you interested?”

“I’d

sure like to talk more about it,” Caniff replied.

“Get

your hat,” Davis said. “Let’s go see Mr. Field.”

Caniff

hadn’t heard of Davis, but he’d heard plenty about Marshall Field. Everyone in

the newspaper business had. Field had just broken the membership monopoly of

the Associated Press in order to get the service for his new paper in Chicago.

He was the millionaire publisher of one liberal newspaper and the sole

financial underwriter of another. In September 1940, Field acquired a

substantial interest in the foundering quixotic newspaper experiment of the

crusading journalist, Ralph Ingersoll. Dedicated to the unfettered pursuit of

the truth, PM accepted no advertising

in order to avoid being beholden to any outside influences. And Ingersoll’s

sense of mission had given Field an idea of his own. In 1941, he launched the Chicago Sun in order to give Chicagoans

the facts they needed to counter the pernicious effects of Colonel Robert

McCormick’s right-wing prejudices that twisted the news in his Chicago Tribune.

Caniff

knew a good deal about Field, but he’d never met him. He had, however, written

him a letter quite recently. In early October 1944, Field had addressed the

Capital Press Club, an organization started by African-American members of the

Washington press corps who weren’t welcome at the National Press Club. Field

talked about racial discrimination and segregation in the armed forces, in

defense work, and in the news media. After reviewing the significant roles

blacks were playing on the world’s battlefield, Field went on to talk about

what the press should be doing to improve race relations.

“Many

white Americans have no idea even of the number of Negroes in the armed forces,

let alone what their role has been,” he said. “The bulk of newsstories in the

daily press about Negroes is not connected with the War. Even now, Negro crime

stories are more frequent than Negro soldier stories. There are exceptions to

this newspaper treatment. I wonder how many of you noticed the episode in Terry and the Pirates in which Terry was

flying from China to India [Sunday, February 13, 1944]. On the way, he passed

by the point at which Negro combat engineers are building the Ledo Road and

fighting off Japanese patrols. Milton Caniff’s drawing showed the Negro

engineers. There was no comment, and no tag-line, but it was plain that these

were Negro troops. This is the sort of thing that is needed.”

Caniff

heard about what Field had said, and he wrote him one of those notes of

appreciation that he was in the habit of dispatching to anyone who mentioned

him or Terry favorably. When Field

read the note, he doubtless sensed a kindred spirit, and he decided to try to

woo the famous cartoonist away from the Tribune-News.

To

compete successfully for the city’s readers, the Chicago Sun had to have popular features as well as the latest

news. When filling his comics page, Field was thwarted by the usual exclusivity

clause in syndicate contracts with papers already in the city. Moreover, the

two syndicates with the most popular comics were closely allied with his

paper’s two chief competitors: the Tribune-News Syndicate would clearly never

sell him any feature the Chicago Tribune was

using or might want to use; King Features would never sell him anything

Hearst’s Chicago American might want.

To

court comic strip features, Field set up a rival operation, the Chicago Sun

Syndicate, operating under Field Enterprises. Putting veteran newspaperman

Harry Baker at the helm of the Syndicate, Field started looking for talent. He

picked up Crocket Johnson’s creation for PM: the winsome and sophisticated Barnaby, which was charming the nation’s

intelligentsia with its bright preschooler and his fairy godfather, an Irish

pixie and failed confidence man named O’Malley. With a brilliant beginning,

Field was stuck for a second act. He decided to raid other syndicates, hoping

to seduce experienced talent into his fold. And he was about to get lucky.

Smith

Davis hailed a cab as soon as he and Caniff walked out of the Waldorf-Astoria

into the wintry blast blowing across town on 49th Street. As they climbed into

the back seat, Davis told the driver to take them to a Park Avenue address

twenty blocks uptown. Fifteen minutes later, they got out at 740 Park Avenue

and went right up to Field’s apartment. Davis introduced Caniff to Field and to

his business manager, Charles Cushing.

Marshall

Field was 51 years old; the cartoonist, 37. Field was about the same height as

Caniff, and both men combed their hair straight back, but Field’s was silver,

and Caniff’s jet black. The men immediately relaxed, seemingly suited to one

another. Caniff’s easy familiarity and gentle banter complimented Field’s quiet

but unpretentious and wholly egalitarian reserve. They were both gentlemen in

the best and classic sense of the term, men of conscience and comity.

“I

understand you might be interested in doing a strip for Field Enterprises,” the

publisher began in his quiet British accents.

“Yes,

sir,” Caniff said. Then came the question he was looking for.

“What

would you want?” Field asked.

Milton

Caniff had been waiting for this moment for years. He wanted what every

creative artist always wants—absolute control of his creative product. They’d

all talked about it endlessly at Ganzi’s and at Child’s and in buses and

station wagons and airplanes on their way to entertaining the wounded all up

and down the eastern seaboard. Now maybe he would get it. He took only an

instant to put his terms into words.

“I

want two things,” he said. “First, full ownership of the property; second, full

editorial control.” He stopped and held his breath. But not for long.

“Veddy

good,” said Field almost at once. “You shall have both.” Then he smiled,

showing that he knew exactly the kind of breach he’d just made in the citadel

of syndicate tradition. “I’m out to emancipate you,” he continued, extending

his hand. “I imagine you’re a well-paid slave.”

They

shook hands on it. And then Field sent for his butler, and they ordered drinks.

“That

was the end of the conference,” Caniff said, recalling the event. “He had said

yes—just like that! Didn’t even argue a point. That was it—full ownership,

complete control.”

His

dream was about to come true.

Caniff

had never felt that the Tribune-News Syndicate had cramped his style in any

significant way. He knew the rules by which an entertainer was expected to be

guided in a family newspaper, and he was comfortable with those rules and had

no desire to break any of the serious ones. So a contract guaranteeing him

editorial control guarded against unspecified eventuality rather than reforming

any existing tyranny. But full ownership of the feature was another matter.

Full

ownership would bring a real and momentous change in his state in life. He

would no longer would be simply a galley slave, profiting only so long as he

continued to pull at the oars daily. He would no longer be working for someone

else. He’d be working for himself. Whatever came of his efforts would be his.

He would control the destinies of his characters both within the strip and

outside of it. No more movie deals unless he had final approval of the

treatment and interpretation of his creation. As owner of the feature, he would

be entitled to the creator’s share of whatever the strip and its characters

earned on the licensing circuit. Finally, he would have an estate, something

that would provide for his wife Bunny in the case of a fatal bump on the shin.

The new strip would be that estate, and when he died, whoever continued the

strip would be working for Bunny because she would inherit ownership of it.

They

hadn’t discussed money at all in Field’s Park Avenue flat, but the financier’s

emancipation proclamation assured that Caniff would be more generously

compensated than at the Tribune-News. That proved to be the case when he worked

out the financial details with Cushing a few days later. Again, there was no

haggling.

But

when Caniff left Field after their first meeting, the cartoonist had more than

money on his mind. He was reeling mentally. It had happened so fast. Had he

really agreed to do a new strip? To give up Terry? To abandon his life’s work? The questions tumbled around inside his head,

but he had no doubts about his decision. “I knew I was going to do this thing,”

Caniff told me, “and I desperately wanted to do it.”

“Many

people have asked me if this was not a difficult decision to make,” Caniff

wrote several years after meeting Field. “Of course it was, but for different

reasons than you might suppose. My thinking went something like this: it would

be a wrench to abandon the characters I had built up in Terry, but my contract specified that they all belonged to the

Tribune-News Syndicate—lock, stock, and barrel—so I was not really giving them

up. ... What made the decision really tough was that in 1944, my contract with

the Tribune-News had two years to run! I would be a lame duck for all that

time. I have always been grateful to Mollie Slott and others at the

Tribune-News who could have made life rough for me for two whole years but who

were big enough people to treat the situation for what it was: a business deal

in which I improved my personal position and created an estate for my family.”

Not

everyone at the Tribune-News would prove to be as big as Mollie Slott, who,

though not the nominal head of the Syndicate, ran its day-to-day operations. At

the moment, no one had any inkling that Caniff was about to jump ship. And he

had no intention of telling them any time soon. In the first place, his deal

with Field was his business, not theirs; secondly, Caniff was a little

apprehensive of what Captain Joe Patterson, head of the Syndicate, might do

once he found out one of his star players was leaving the fold. Caniff’s

Tribune-News contract was sound, but in a paternalistic relationship like

Patterson had with his cartoonists, a cartoonist’s lot could be made

uncomfortable without violating a single provision of a contract. There was

also a matter of pride.

“I

deliberately didn’t use the Field thing as a bargaining stick of any sort,”

Caniff said. “I didn’t ask them if I stayed would they give me the copyright on Terry. ’Cuz I knew they wouldn’t. If

I’d have been in their shoes, I wouldn’t have done it either.”

During

the next week, Caniff met with Cushing several times. On November 9 they signed

a letter of agreement. Caniff’s compensation was established in an

astonishingly casual exchange with Cushing. Caniff’s description: “They said,

Well, $100,000 a year is a good round number—shall we talk about that as a

start? And I thought, That’s nice,” he chuckled. “I said, Fine—just go from

there. They put it on the basis of $2,000 a week, which was more than $100,000

a year. And we didn’t have any further discussion.”

Caniff

would lose very little sleep over leaving Terry.

Caniff

was eager to get on with the project. Almost without his willing it, his

imagination began to race—considering possibilities, conjuring up new heroes

and heroines, playing out alternative scenarios. It would be an adventure

strip, but this time, the hero would be an adult, someone who could smoke and

drink and dally with the ladies. This time, Caniff wouldn’t be painted into a

storytelling corner with a restrictive subtitle like “and the pirates.” His new

hero would be free to do anything anywhere. He’d be a globe-trotting

trouble-shooter and—. Caniff reined himself in. He still had two years to go on Terry. He had a contractual

obligation and a world-wide audience to satisfy. Terry was in the War for the sake of the troops’ morale. He couldn’t

disappoint them.

An

even more compelling logic persuaded Caniff to put the new strip aside: he

wanted to protect his ownership. Technically, the Tribune-News people could lay

legitimate claim to anything he produced while under contract with them.

“Everything

belonged to the Tribune-News,” Caniff said. “Even stuff in the waste-basket. If

I touched pen to paper, it belonged to them.”

Legalistic

hair-splitting perhaps. Perhaps the Tribune-News wouldn’t care what he produced

in his “spare time,” but maybe the Syndicate would not entertain the notion of

any of his contract time being “spare” or in any way his own. After all, he was

a kind of indentured servant, and the Syndicate was entitled to everything he

did. Maybe they wouldn’t be that spiteful.

Perhaps.

Maybe. Not enough to build a secure future on. Since he was willing to give up Terry and all the characters he had

created and nurtured so lovingly for so long—to give them all up simply to

secure ownership of his own feature—Caniff dared not risk losing that ownership

by gambling on “perhaps” and “maybe.” He resolved to refrain from doing any

visible work on the new project until after his Terry contract expired. He could think about the new strip, but he

wouldn’t produce any tangible evidence until his Tribune-News contract ended on

October 15, 1946.

It

would be a long two years. But Caniff anticipated no difficulties as long as he

kept quiet for as long as he could. Then

1944 ended and the New Year dawned. And the dawn came up like thunder, shaking

Caniff and his friends and shattering conviviality in some quarters forever.

Walter

Winchell lobbed his bombshell casually from the second paragraph of his “In New

York” column in the New York Daily Mirror on Monday, New Year’s Day: “The creator of the famed comic strip Terry and the Pirates, with two more

years to go [on his present contract], signed with Marshall Field last week—to

switch at expiration of his contract. The reason allegedly is over his Midwest

publisher’s attempt to inject political stuff into the strip. ...” Someone at

King Features had obviously leaked this garbled version of the situation to

Hearst’s star columnist.

The

story broke on a holiday in an afternoon paper Caniff didn’t subscribe to, so

he didn’t find out about Winchell’s scoop until the next day. By Tuesday

morning, friends and reporters had lost their inhibitions about disturbing the

cartoonist’s holiday. His phone began ringing early in the morning. Reporters

from Time, Newsweek, Editor &

Publisher, and Tide (another trade

publication) called to verify the facts. Was he quitting the Tribune-News

Syndicate because McCormick and Patterson had pressured him to slant Terry?

Caniff

was incensed. The generally liberal attitudes reflected in the strip had

doubtless irritated both the Colonel and the Captain at times, but neither one

had ever said anything about his advocating their political beliefs in Terry. Caniff denied Winchell’s charge

and set the reporters straight. Politics had nothing to do with his forthcoming

departure, he said; he was leaving the Tribune-News because Field was giving

him ownership and a hefty income. As soon as he finished with the first

reporter, he fired off an indignant telegram to Winchell, vehemently protesting

the columnist’s allegation and asking him to print a retraction. Winchell

complied, leading off his January 7 column with the correction.

Then

came the phone calls from friends. Some of the calls, like Mollie Slott’s, were

tough to take. “She called and asked me if it was true,” Milton remembered. He

paused before continuing. “I told her it was.” She was upset. But she knew he

was getting a better deal with Field. She wished him well.

Later,

Mollie’s sons—both in the service, both fans of Caniff since Dickie Dare —found out, and she wrote

Milton about their reactions. “In a recent letter, Lee said: ‘I don’t have to

tell you, Mom, how sorry I was to hear that Milton Caniff’s going to leave Terry.’ Bill heard about it while he was

home on furlough and felt the same. Both reflected my own feelings.”

Captain

Patterson, on the other hand, had nothing whatever to say to Caniff—then or

ever. “I don’t think Patterson ever forgave me for leaving,” Caniff told me.

“McCormick did. I had a nice letter from him, saying good luck—wishing me well.

Never heard from Patterson. You’d think it would be the other way around. I was

Patterson’s boy, after all: he was the one who hired me, not McCormick. I don’t

know, actually, that Patterson felt any rancor about it. But he never spoke to

me again.”

Caniff’s

departure from his Syndicate was big news in newspaper circles. As stories in Time and Newsweek and Editor

&Publisher spread the word, confirming the gist of Winchell’s

announcement, eddies of reaction lapped at the cartoonist’s doorstep.

For

most of his inky-fingered fraternity, Caniff was suddenly a hero. In striking

his deal with Field, Caniff had also struck a blow for creative freedom and

cartoonists’ rights. “Milton became a symbol to all the cartoonists,” Toni

Mendez said to me, “because he was able to walk away from Terry and successfully set himself up. He was a symbol because it

took a lot for him to do what he did and live out the rest of his contract.”

Why

Roy Crane, who had done exactly the same thing only a little over a year

before, did not become the profession’s guidon is an accident of history.

Crane, although scarcely over the hill, was no longer at the peak of his

popularity; Caniff was. Crane had only Wash

Tubbs. Caniff had Terry and Male Call, and both had mustered

enormous and fanatically loyal followings in overheated wartime. Hence, Caniff

had clout, and what he did made a bigger impression on the establishment than

anything Crane might do.

National

coverage of Caniff’s departure effectively advertised his future availability,

and within a couple weeks of Winchell’s proclamation, Harry Baker at the Sun

Syndicate had received dozens of requests for options on Caniff’s new strip

without anyone’s knowing what kind of a strip it would be. “I’ve never

witnessed such tremendous interest in the work of an artist,” Baker said. Two

years later, Steve Canyon debuted in

234 newspapers; 162 of which had bought the strip before Caniff’s Terry contract was up—in other words,

they had bought his new strip without knowing anything about it except that

Milton Caniff was going to do it.

In

the days right after the Winchell bombshell, at least one editor seized upon

the change in Caniff’s prospects to speculate that the cartoonist would be

slackening off now that he was a lame duck. That gave the cartoonist all the

more reason to avoid working on the new strip. He dedicated himself anew to Terry.

“It

was a kind of challenge,” Caniff said. “Everybody was expecting me to let down.

For that reason alone, I was anxious to do it better than I had ever done before.”

Years later, the minstrel man wrote about some

of the songs he might have sung in Terry.

“I sometimes think back on the plans

I had noodled around with and wonder how they would have played in print,”

Caniff wrote. “For instance, I had roughed up a whopping confrontation between

Big Stoop and the Dragon Lady. I had always kept them apart: he was the only

person she really feared because he had been her slave when she was a girl, and

she had ordered his tongue cut out. That could have been a heavy one. I also

planned to have Pat Ryan marry Burma. That would have been a ‘Taming of the

Shrew’ at jet speed! I never thought that Terry would take the vows. But

keeping a hero single these days is a problem. If he is not shown sleeping

around, readers begin to ask if he’s queer. There was never a stateside story

in my Terry. I was going to make a

big thing of all these China Hands returning to the U.S., showing how the

picaresque hero from the Far Places does not always fare so well in the

conventional surroundings back home.”

By the time he’d reached the end of

his tenure on Terry, Caniff had had

months to prepare himself for the time that he would leave the strip. He had

reconciled himself to giving up his creation to another by reminding himself

repeatedly of how much better his situation would be with Field. But when the

moment of parting came at last, when the irrevocable finality of it rang

through his mind like a peal of bells, when there was nothing more he could do

on the strip and when he needed to let go of it, he felt profoundly like a

parent who was being separated from his offspring. It was a feeling that never

quite went away.

“I felt like I was losing my

children,” Milton said. “It was as if they were being taken away from me by

court order—taken away and shipped off to some distant and dangerous place

where I could do nothing to help them anymore.”

If Caniff felt helpless, his fans

felt, in some measure, abandoned. Some were irrate. Many wrote to say how sorry

they were that he was leaving Terry. They

also expressed eager anticipation about his new strip. Mollie Slott, responding

to one of Caniff’s fans, summed up the contradictory feelings: “I myself feel

as you do about the drawing in Terry and about the artist who draws it. We are sorry to lose him, but it is good to

know that he will continue to give pleasure to millions of readers through

whatever else he does for newspapers.”

Was Caniff sorry to be leaving

Terry? Of course. Did he regret his decision to leave? Perhaps. A little. He never

said anything about it to me in so many words, but once when we were talking

about his departure from the strip, he approached the subject obliquely.

“I didn’t want to use any outside

offer as a lever or as a threat, like blackmail to get more of something,” he

reflected. “I felt they should have voluntarily given me more money. So when

the Field thing came along, they would have had the lever on me if they had

done it voluntarily. But they didn’t. So I felt no attack of conscience at all.

I’d paid off my debt. I’d paid my dues and plenty at that point. The

Tribune-News people were very chintzy about that kind of thing, I always

felt—by comparison with King. For instance, Joe Connolly at King would have

looked over the income sheet, and he would have sensed the moment to give you a

bonus or something. Then he’d have you hooked. It’s a curious kind of blindspot

at the Tribune-News. They had it so made that they just didn’t think about it.

Nobody was ever gonna leave the Tribune.”

He did. But if they hadn’t been so

cheap, what might have happened?

If Caniff had any regrets, he didn’t

have time to indulge them. He had only about two weeks before his first

deadline on the new strip. A Sunday page was falling due. And he had to invent

a hero, a raison d’etre, a supporting

cast, a milieu. An entire world. And only a fortnight for creating it. Caniff

picked up a pencil and smiled: he had been there before.

Footnit: For more about the book,

click here, which destination, in turn, leads you to anorder blank. Getting

your copy from me is the only way you can get my And before taking our leave this time, here’s Caniff’s own version of his life story, done in the 1950's for either Collier’s or Saturday Evening Post as part of a series of full-page comic strips in which several cartoonists (Ham Fisher, V.T. Hamlin, and others) related their autobiographies in comic strip form. I have a color version of this (all of them were in color), but can’t, in the throes of packing up for my move to Colorado, find it; sorry.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |