|

|||||||||||||

|

Opus 207 (June 30, 2007). We spend a long time fondly

remembering Roger Armstrong, a

superb watercolorist and a life-long cartoonist. Otherwise, our big news is

about David Kunzle’s two new books on Rudolphe

Topffer, both excellent; we do a review. Ditto of John Cuneo’s nEuROTIC, a

delicious assault on conventionality. And more. Here’s what’s here, by

department:

NOUS R US

Eisner’s

The Plot Declined at European Parliament

NPR

Picks Graphic Novels for Summer Reading

Homer

Simpson Stolen and Returned

Gordon

Lee Trial Starts August 13

COMIC STRIP WATCH

Lisa

Moore’s Fate

Some

Edgy Moments

Mutt

and Jeff Gay? The Answer, Sort Of

New

’Tooner Debuts on B.C.

Two

New Strips: Cul de Sac and Little Dog Lost

Civilization’s

Last Outpost

Hip-hop

Dying?

Don

Imus Some More

EDITOONERY

AAEC

Celebrates Its Fiftieth July 5-7

Editoons

Reflect Worldwide Opinion of U.S.

Onward,

the Spreading Punditry

Cullen

Murphy and The Purchase of Government and the Outsourcing of Same

BOOK MARQUEES

David

Kunzle is Back With Topffer, Two of Them

John

Coneo’s Scandalous Tome

ROGER ARMSTRONG

1917-2007

Son

of the Spreading Pundtry

Oswald

Acted Alone, Now Leave Me Alone

Ethanol

Won’t Help and It Will Hurt

And

our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by

clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just

this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned.

Without further adieu—

NOUS R US

All the News That Gives Us Fits

This

summer is fraught with anniversaries. As we mentioned last time, “Sgt. Pepper’s

Lonely Hearts Club Band” album debuted 40 years ago, the same year that spawned

the “Summer of Love” in San Francisco; more about which, next time or two.

Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic 80 years ago, and 50 years ago,

Jack Kerouac’s rambling novel, On the

Road, came out. Kerouac typed the book on 12-foot-long strips of paper,

which he then taped together to make a continuous scroll. After three weeks of

perpetual typing, he had 120 feet of typescript, which, with several revisions,

was published by Viking Press. Kerouac’s method seemed so absolutely logical,

so linearly wedded to its purpose, that I adopted it for producing term papers

during my so-called college career: using rolls of teletype paper, I typed

quotations from source books until I turned out 12 feet of scroll, then pulled

it out of the typewriter, cut the scroll up into individual quoted passages,

pasted them together in some sort of narrative sequence, and re-typed it all

with connecting prose between quotations. A 12-foot scroll usually yielded a

15-page paper, just the prescribed length. That summer in 1957, a piano-player

friend of mine named Lee Underwood devoured Kerouac’s book at a single sitting,

reading all night long, and the next day, he packed a suitcase and hit the

road. We never saw him again.

In Brussels, the European Parliament

has refused to distribute to its members copies of Will Eisner’s The Plot: The

Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which had been

supplied in quantity by the Transatlantic Institute, a Brussels-based

think-tank attempting to foster ties among the European Union, Israel and the

United States. But the decision was not an anti-Semitic inspiration. As

reported by Yossi Lempkowicz of the European Jewish Press, since the book has

no direct relevance to the Parliament’s legislative agenda, distributing it

seemed to officials to promote sales of the graphic novel, and the body’s

policy prohibits advertising and all such commercial enterprise. An explanatory

letter added that the decision was “independent of the positive opinion each of

us may have regarding the cause defended by the book.” While the European

Parliament may not have anti-Semitism on its agenda, the Middle East does: Arab

schools harbor anti-Semitic curriculum, and the nefarious book at issue, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, “the lie that will not die,” enjoys brisk sales throughout the region. A French

version of the book in novel form was sold in the European Parliament’s

bookshops until late May when the President of the Parliament ordered their

removal. Seems right, albeit somewhat belated. As Emmanuele Ottolenghi,

executive director of the Transatlantic Institute, said, “Why should the Protocols be easily available in the

Parliament but the refutation of the Protocols [Eisner’s book] would not be allowed to reach the members?”

BookExpo America is one of the

“largest industry conventions on the circuit,” we are told at

bookshelf.diamondcomics.com, the website of the nation’s largest distributor of

comics and graphic novels and their ilk. Not surprisingly, considering the

source, BookExpo America 2007 was “a rousing success” with over 2,000 exhibits,

500 authors and 60 conference sessions, at least two of which were devoted to

graphic novel and comics-related topics. One of them, titled “Taking Kids’

comics to the Next Level,” asked what the challenges are “facing graphic novels

in the children’s section of the bookstores?” In the children’s section? This

sort of success doesn’t seem all that rousing to me. “Rousing” would be when

the book trade starts seeing graphic novels as literature for grown-ups.

At the same website, we learn that

National Public Radio (NPR) has listed a number of graphic novels on its Summer

Books 2007 series—namely, David Peterson’s Mouse

Guard Volume 1: Fall 1152, Kieron Gillen and Jamie Mckelvie’s Phonogram: Rue Britannia, Bryan Lee

O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim Volume 1: Scott

Pilgrim’s Precious Little Life, and Cecil Castellucci and Jim Rugg’s The Plain Janes. ... At Woodstock,

Illinois, during this year’s annual five-day festival, Dick Tracy Days (June 20-24), Jean Gould O’Connell, the daughter of

Tracy’s creator, signed copies of her new book, Chester Gould: A Daughter’s Biography of the Creator of Dick Tracy. Said O’Connell, quoted in the Northwest

Herald by Jenn Wiant: “I think the book really tells a great story about a

man who came from a very poor family in Oklahoma and raised himself up by the

bootstraps. He had determination as a young boy to become a cartoonist, even at

the age of seven, and he fulfilled that dream.”

In Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the Homer

Simpson thieves have been apprehended and Homer restored to his place in a

display at a local cinema, where he was promoting the impending Simpsons movie.

Two college students made off with a life-sized fiberglass Homer replica in the

wee hours of June 18, according to Sean Yoong of the Associated Press at

news.yahoo.com, but they reckoned without the vigilant close-circuit security

cameras, which showed the thieves stowing the four-foot Homer in the trunk of

their car and speeding away, the car license plate in full view, and the police

tracked them down. Homer was returned unscathed. “The Simpsons Movie” opens in

Malaysia on June 26, the day before its U.S. release.

Mutts creator Patrick McDonnell spoke

at the first graduation ceremony at James Sturm’s Center for Cartoon Studies.

Among his remarks were these: “When I started my comic strip Mutts, it was just an idea about my own

dog Earl, and a silly cat named Mooch. Seeing the world through the eyes of

animals made me more aware and empathetic to their lives. I began to realize

how tough it is for all animals on this small planet, and how fragile and

sacred all life is. This became a big part of Mutts and led to my becoming a director on the board of the Humane

Society of the United States. Saying that Mutts changed my life is an understatement.”

From Charles Brownstein, Executive

Director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund: “We hope to bring the Gordon Lee

case to a close when Lee [owner of a comic book store in George] goes to court

[August 13] to face down the two remaining misdemeanor charges of ‘Distribution

of Harmful to Minors Materials’ left in the case. Since taking the case last

year, the Fund has knocked out both felony counts of ‘dissemination of

Unsolicited Nudity/Sexual Conduct’ and three of the five misdemeanor counts.

... The charges Lee faces arise from accidentally distributing Alternative Comics No. 2, a Free Comic

Book Day anthology including an excerpt from Nick Bertozzi’s ‘The Salon’ [that

depicted] the first meeting of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. On three pages

of the eight-page section, Picasso is depicted in the nude, a factually

accurate detail for the period during which the story is set. [That is, Picasso

usually went around his studio naked.] There is no sexual content in the story.

The comic was inadvertently distributed to a minor during a 3-hour Hallowe’en

promotion where 2,200 comics were given away [at Lee’s Legends comic book store

in Rome, Georgia]. Lee offered apology but it was refused, and within days, he

was arrested and fighting for his survival.” If you think this case is absurd

in the extreme, remember who elected GeeDubya twice. To contribute to the cause

and/or to join the CBLDF, visit www.cbldf.org

Mandrake, the comic strip magician

who uses powers of illusion and hypnotism to fight crime, may get into the

movie theaters in the future. The strip created by Lee Falk in 1934 has attracted the attention of

magician/illusionist Criss Angel, star of the “Mindfreak” tv show on A&E;

the movie’s director is reported by Editor

& Publisher to be Chuck Russell, who directed “The Mask,” another

comic-related creation. ... The Superman costume worn by Christopher Reeve in the initial Superman movie sold for

$16,750 at a London auction June 20 (news.yahoo.com). ... The latest plastic

action figure on Hasbro’s production schedule is Stan Lee, who will be cast six inches tall in khaki pants, blue

windbreaker, and shades. The

Fascinating

Footnote. Much of the news

retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and

related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve

deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and

lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com.

And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com

COMIC STRIP WATCH

In Brooke McEldowney’s 9 Chickweed Lane, Thorax, the

other-worldly (that is, alien) gentleman farmer, shows up occasionally with his

“Locutionary Field Guide to Earth,” usually defining an ordinary term in ways

we would not, normally, anticipate. For instance: “Patriotism, noun: The

willing act of putting one’s well-being at risk for politicians who are not

similarly disposed.” McEldowney’s superb strip, regrettably not widely

circulated, is one of the strips that will be spotlighted in Alan Gardner’s News Free Comics, a publication

presently on hiatus pending the recruitment by August of at least 2,000

subscribers. Other modestly circulated comic strips on Gardner’s list include Michael Jantze’s The Norm (currently available online by subscription at www.thenorm.com), Jef Mallett’s Frazz, and some other favorites. Visit Gardner’s website, just

cited above.

Culled from Editor & Publisher: Lisa Moore, the character with recurring

breast cancer in Tom Batiuk’s Funky Winkerbean strip, will die this

year according to a report in the Cleveland

Free Press. Also this year, the cast of the strip will grow older by ten

years. Batiuk aged them all in the early 1990s, transforming his high school

teenagers into young adults. ... Scott

Adams posted his Dilbert submission package on his website—the strips that sold the feature into

syndication, plus an assortment of mixed reactions to the strip. “One syndicate

suggested that Adams collaborate with a more accomplished artist.” ... Legacies

continue to expire. The Commercial

Dispatch of Columbus, Mississippi, added seven strips to its comics line-up

by dropping seven others, including four legacy strips: B.C., The Wizard of Id, Blondie, and Dennis the Menace.

In our continuing survey of current

comic strips to discover just how many taboos are being discarded these days,

we see that Wally, one of Dilbert’s co-workers, has been identified as “a

source of methane,” which Dogbert “the Green Consultant” decides to capture “as

a free source of energy that we can use to power a small office building.” In

the final panel, Wally is depicted with a tube attached to his rear end. What a

gas! But fart jokes were verboten in the funnies for eons. ... And here’s Shoe for June 22, in which Roz, the

diner owner, tells the Perfessor that she’s not going to sponsor the bowling

team this year, an announcement met with a mild protest—“C’mon, Roz: it’ll give

you a nice warm feeling to help us out”—to which Roz responds: “The last thing

a gal my age needs is more warm feelings.” Menopause comedy. ... Jeff, I guess,

lives with the Mutt family. I wondered, some weeks ago, what the living

arrangements were for Bud Fisher’s famed Mutt and Jeff. The two are often

depicted in a domestic setting, suggesting that they share an apartment. But

Mutt is married, and sometimes the gags feature his wife or son. Still, the

mystery remained: I said that Mrs. Mutt and Johnny

Hart’s B.C. has completed the

month-long commemorative re-running of the Hart family’s favorite strips and,

on June 11, began the new crop, drawn by Hart’s grandson, Mason Mastroianni. According to Perri, Hart’s youngest daughter:

“Mason is an accomplished artist ... [who] picked up his Cul

de Sac is a new comic strip from Universal Press produced by Richard Thompson, a humorous

illustrator who achieved more than fifteen minutes of fame on the Web in 2002

with a poem composed of actual quotes from GeeDubya. Entitled “Make the Pie

Higher,” this is the poem:

I

think we all agree, the past is over.

This

is still a dangerous world.

It’s

a world of madmen and uncertainty

And

potential mental losses.

Rarely

is the question asked

Is

our children learning?

Will

the highways of the Internet become more few?

How

many hands have I shaked?

They

misunderestimate me.

I

am a pitbull on the pantleg of opportunity.

I

know that the human being and the fish can co-exist.

Families

is where our nation finds hope, where our wings take dream.

Put

food on your family!

Knock

down the tollbooth!

Vulcanize

society!

Make

the pie higher! Make the pie higher!

Cul de Sac, on the other hand, is reality-based, the reality

being the world of a four-year-old named Alice Otterloop, who lives, naturally,

on a cul de sac. There, New last March from Washington Post Writers Group is Little Dog Lost, a talking animal strip by Steve Boreman, who deploys his animals in that fashion honored by satirists ever since Aesop—namely, to comment upon the human condition. The eponymous canine wanders the world and encounters all sorts of personalities on his way—scavengers like the Vulture and Jackson the Crow, Vernon the grumpy tortoise, always complaining; Beavers who are real estate developers, and Carlton the mouse (who the Vulture won’t eat because he’s on a first-name basis with the rodent). Said comics editor Amy Lago: “What I love about Little Dog Lost is its layers. Steve gives you a shoal-draft level of humor that will amuse any reader. The more thoughtful ones will also see its deeper meaning—its commentary on nature, human nature, and humans’ effect on the earth—and pat themselves on the back for getting it. It’s a perfect way to please the readers.” Boreman, who has freelanced as an illustrator and taught design and digital illustration at the Columbus (Ohio) College of Art and Design for twelve years, draws in a loose-limbed but lumpy manner, pleasing to the eye through the variety of his compositions and treatments. Here are some samples.

Read

and Relish

“There are two kinds of people in

the world: those who divide the world into two kinds of people and those who

don’t.” —Robert Benchley

And if you want to read why Esquire’s cover story on Angelina Jolie

is “the worst celebrity profile ever written,” go to http://www.Slate.com/toolbar.aspx?action=print&id+2168707 where you’ll find Ron Rosenbaum’s June 19 essay with the title just quoted.

It’s a hoot.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis

Miller adv.

USA Today reported (June 15-17) that hip-hop “with declining sales and concerns about its quality and

‘gangsta’ image, is in crisis. Even some rappers say it risks becoming

irrelevant.” Sales of rap albums are down 33% from last year, “twice the

decline for the [record] industry overall.” The paper reviews the history of

the genre: “Hip-hop was born out of DJK-hosted block parties in the Bronx,

N.Y., in the early 1970s and evolved with emcees ‘rapping’ over the beats the

DJs played. The genre hit the Top 40 with the Sugar Hill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight in 1979. Rap soon

became, as Public Enemy’s Chuck D described it, ‘the CNN of black culture,’

encompassing everything from party tales to political commentaries, especially

from the view of poor and disaffected urban youths. Rap found an audience not

only in cities but in mostly white suburbs as well. By the 1990s, a

harder-edged version of rap that glorified gang life began to dominate music

and influence youth culture. Its songs and videos typically depict violence and

drug dealers awash in diamonds and platinum jewelry, champagne and scantily

clad women. Rap became a multibillion-dollar-a-year global industry,

influencing fashion, lifestyles and language while selling everything from SUVs

to personal computers.”

When Don Imus attracted attention in April for his racist remarks, the

resulting fall-out rained a little on hip-hop, which made popular the kind of

language that inspired Imus and his cohorts. Commentators on the Imus imbroglio

also sometimes called for a clean-up in hip-hop lingo. Oddly, now that we’re

far enough away from the Imus incident to view it somewhat dispassionately—at

least, perhaps, without heat—it seems likely that he was attempting, in his

clumsy good old boy manner, to praise the Rutgers’ women’s basketball team.

Tennesse beat Rutgers, and Imus marveled at the achievement because the Rutgers

team had a reputation for being very good and very tough. “That’s some rough

girls from Rutgers,” he said, in seeming admiration, “—man, they got tattoos

and—.” “Some hard-core hos,” chimed in Bernard McGuirk, Imus’s on-air buddy and

duty goad. Then Imus piled on McGuirk’s remark: “That’s some nappy-headed hos there. I’m gonna tell

you that now, man, that’s some—woo! And the girls from Tennessee, they all look

cute, you know, so, like—kinda like—I don’t know.” He was still being racist,

but he was also, in some perverse way, saying the Rutgers team was so tough

that it was difficult to imagine any other team could beat them. Well, that’s

the trouble with communication: it creates the illusion that it has been

accomplished.

EDITOONERY

Afflicting the Comfortable and

Comforting the Afflicted

From Editor & Publisher: The Denver Post’s editoonist Mike Keefe received the Freedom of the

Press award from the Anti-Defamation League’s Mountain States Office for his

cartoons about bigotry, separation of church and state and other similar

topics. ... Jim Morin of the Miami Herald is this year’s winner of

the $10,000 Herblock Prize for editorial cartooning. “He just gets better and

better,” said Jeff Danziger, who

collected the Prize last year and was therefore one of this year’s judges.

Morin won the Pulitzer in 1996.

The Association of American

Editorial Cartoonists celebrates its 50th anniversary during its

annual meeting, this year in Washington, D.C., July 4-7. Scheduled speakers

include Flemming Rose (he of the Danish Dozen fame), former White House

correspondent Helen Thomas, political columnist Mark Shields, Dana Priest, one

of the Washington Post reporters who

broke the Walter Reed Hospital story, “Daily Show” writer Kevin Bleyer, and

Democrat presidential candidate Dennis Kucinich, among others. We’ll report

first-hand the ensuing doings here in our next installment.

HOW EDITORIAL CARTOONS REFLECT PUBLIC

OPINION WORLDWIDE

And

How Foreign Cartoonists Look at the U.S.

Political cartoonist Daryl Cagle, who operates a website (www.cagle.msnbc.com) featuring a huge daily dose of political

cartoons, also runs a syndicate that markets many of the cartoons to other

websites and to print media. And he has a blog at his website, too, where he

occasional holds forth. On February 4, 2007, he wrote about how editorial

cartoons are accurate reflections of public opinion at the time they are drawn.

Because his syndicate distributes the work of several cartoonists from other

countries, Cagle regularly sees how the U.S. is perceived in other lands. His

is a unique insight, an uncommonly valuable insight. Here he is:

As a political cartoonist, I’d like

to think my cartoons influence public opinion, but that rarely happens. People

love a cartoon that they already agree with and hate cartoons that they already

disagree with. Editors like to choose editorial cartoons that they know their

readers will like, so cartoons end up being a reflection of public opinion. In

fact, political cartoons offer a great historical tool, giving a true picture

of the opinions and emotions of a society at any given time.

Historians seem to have discovered

political cartoons only recently, and I’ve started seeing a steady stream of

scholarly papers about my profession as college professors and students

suddenly look to my work and the work of my colleagues to support their

political positions. One widely held canard seems to be popular among the academics:

that the world supported the USA after 9/11 and this support was then

squandered by the Bush Administration's adventures in the Middle East.

Academics like to look at the

cartoons drawn immediately after the 9/11 attack, when, around the world, almost

every editorial cartoonist drew the same image of a weeping Statue of Liberty.

I drew one, too. In fact, most cartoonists are ashamed of their weeping

statues; we wish we could have a “do-over” where we wouldn’t draw the first

image to come to mind. Newspaper columnists all wrote much the same column

right after 9/11, but it is easier to notice matching cartoons than matching

columns, so cartoonists get the bad rap for “group-think.” Even so, our

matching cartoons were what the public wanted to see at that time, and I

probably received more mail from readers who loved my weeping Liberty than any

other cartoon I’ve drawn.

International political cartoonists

revile the USA in a uniform drumbeat of daily digs at America. The academics

don't notice that international political cartoons before 9/11 were almost as

negative about America as the cartoons now. After our matching, weeping

statues, the American and international cartoonists diverged. On 9/12 American

cartoonists started drawing patriotic cartoons portraying resolve, strength,

and the virtues of the New York Fire and Police Departments, standing tall as

twin towers. American cartoonists drew scores of images of a strong Uncle Sam,

threatening eagles, and a newly militant Statue of Liberty, demanding revenge.

Just after 9/11, the international

cartoonists depicted the irony of mighty America put in its place. A favorite,

foreign symbol for America is Superman, and we saw scores of images showing

both Superman and Uncle Sam defeated, injured, bleeding, and grieving. The

worldwide cartoonists treated 9/11 in the way that tabloids treat fallen

celebrities: with delight in the spectacle of a beautiful actress whois

overweight, or getting a messy divorce—or better yet, caught in a drunken

scene, screaming racial epithets so that we can see that the rich, powerful,

famous, conceited, fallen star was a hypocrite all along.

Some international cartoonists wrote

to me about the patriotic cartoons; they couldn’t believe American cartoonists

would choose to draw such cartoons by their own free will; we must have been

directed to draw that nonsense by the Bush Administration. Academics have

picked up on the idea of “self-censorship”; that cartoonists somehow didn’t

draw what they wanted to draw because the country wasn’t ready for jokes, or

editors didn’t want to see criticism of the Bush Administration at a time when

we all had to pull together.

In fact, the system worked as it

always had: some cartoonists criticized the government right away, some

cartoonists were joking immediately, most cartoonists held the same opinions as

their readers, editors selected cartoons they agreed with and thought their

readers would agree with. Newspapers ended up printing cartoons that accurately

reflected public opinion, both here and abroad. I have a few words for the

professors and college students:

(1) Editorial cartoons show that the

rest of the world didn’t like America before 9/11; they didn’t like us just

after 9/11; and they still don’t like us.

(2) The government doesn’t control

or intimidate American cartoonists or editors, now or then. Yes, we really

believe what we say in our cartoons. No, cartoonists are not hampered by

self-censorship.

(3) Please don’t ask me to comment

on your paper, thesis or dissertation about editorial cartoons. Just read this

column, then write about something else.

Onward, the Spreading Punditry

The Great Ebb and Flo of Things

Cullen

Murphy has about him a certain mussed and tweedy look, the look of a scholar of

medieval history, which is what he studied to get a master’s degree before

pursuing a career as a journalist. Some of us recognize Murphy as the former

managing editor of The Atlantic Monthly,

which he left last year after 22 years, and many of us recall him as the writer

of Prince Valiant, which duty he

performed for his father, the late John

Cullen Murphy, who succeeded the strip's originator, Harold Foster, when the latter retired in 1971. After departing the environs of The Atlantic Monthly, Cullen Murphy

joined the merry band at Vanity Fair as

an editor-at-large, and he has been pictured in two successive issues of the

magazine, April and May, as a contributor. In

May, Vanity Fair went green—with a

vengeance. Nearly every major article is about the rape of the environment or

the Bush League's connivance with the rapists. As editor-at-large, Murphy

picked many of the topics. In one of the shorter pieces, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

provides brief reviews of the careers of many of GeeDubya's appointees to key

positions in government agencies charged with enforcing environmental laws; all

of these factotums worked, at one time or another in their professional lives,

for the polluting industries that they were now supposed to regulate. More than

100 of these appointees have worked

diligently in the backrooms of government to roll back decades of progress,

promoting and implementing "more than 400 measures that eviscerate 30

years of environmental policy." One such operative, Phillip Cooney, spent

four years "combing scientific documents issued by various federal

agencies in order to remove damaging statements about the oil industry and the

coal industry. He suppressed or altered several major studies on global warming

in order to protect the interests of his former clients." He had been the

chief lobbyist for the American Petrolelum Institute; he left the White House

in 2005 to go to work for Exxon Mobil. These Bushy legions, Kennedy says,

"have entered government service not to serve the public interest but

rather to subvert the very laws they are charged with enforcing." He ends

by quoting Jim Hightower: "Corporations don't have to lobby the government

any more. They are the government." In one of the longer pieces, William

Langewiesche rehearses the history of

Texaco and Chevron in steeping huge tracts of Ecuadorean Amazon landscape in

the toxic waste of their oil extraction operations over more than twenty years.

The hero of the piece is Pablo Fajardo, an Ecuadorean peasant cum lawyer who

leads the legal battle against Chevron. Said Fajardo: "One of the problems

with modern society is that it places more importance on things that have a

price than on things that have a value. Breathing clean air, for instance, or

having clean water in the rivers or having legal rights—these are things that

don't have a price but have a huge value. Oil does have a price, but its value

is much less. And sometimes we make the mistake."

In Vanity Fair’s April issue, Cullen Murphy contributes an out-take

from his forthcoming book, Are We Rome?

The Fall of an Empire and the Fate of America. Like many of the fashionable

doom-sayers, Murphy finds a fateful kinship between ancient Rome on the cusp of

its collapse and the United States, poised, now, on the brink of the 21st Century. I’ve already pontificated on the subject, claiming a greater kinship

between the U.S. and ancient India, which devolved as a civilization when it

became so populous that it couldn’t take care of its citizens. In his book, the

link Murphy finds between the U.S. and Rome is not in moral decay, the usual

symptom, but in privatizing—or “outsourcing,” to use the prevalent

term—government services. This phenomenon was rooted, Murphy claims, in the

evolution of Roman government, the purpose of which, ultimately, was to foster

the wealth and personal advancement of its operatives. I’ve often thought, in

recent years, that the whole function of the U.S. Congress is as a mechanism by

which its members decide how to divide up the tax revenue that is collected

every year. “Governance” is not at all on the agenda; neither is the well being

of the country. Congress, as far as the interests of its members are concerned,

has nothing to do with either. In Rome, government was accomplished by paying

private contractors for public services.

“The effect,” Murphy says, “is to

insert an independent agent, with its own interests to consider and protect,

into the space between public will and public outcome—a dynamic that represents

a potential ‘diverting of governmental force’ far more systemic and insidious

than outright venality.’” This sort of perversion has been moving rapidly into

the American government since the mid-1970s, when “government agencies [began]

farming out various functions to high-priced consultants, secretive think

tanks, and corporate vested interests—accountable to no one!” One of the industries that has enjoyed a

considerable growth surge in this vein is the private security business. In

1960, there were more police officers than private security guards; “today

private guards outnumber the police by a margin of 50 percent,” Murphy says.

“Individuals may owe nominal allegiance to a town or a state, but their true

oath of fealty is to Securitas or Guardsmark.”

Last year in the wake of the aborted

plan to turn over operation of half-a-dozen U.S. ports to DP World, a company

in the United Arab Emirates, we learned, and were shocked to discover, “that

the privatization of terminal operations at American ports had begun three

decades ago, and that 80 percent of them were already operated by foreign

companies, the largest of which is Chinese.”

Our misadventure in Iraq has

revealed just how much of the presumed function of government has been

contracted out to private concerns. Darth Cheney’s Halliburton and its

subsidiaries are doing much of the work for the military that, in the olden

times (10-15 years past), the military did for itself—such as running mess

halls, for instance. These private operatives, plus the construction work force

and the security guards operating in Iraq threaten to outnumber the military:

before GeeDubya’s much advertised and debated “surge,” there were about 140,000

troops in Iraq and 100,000 contract employees. “Contrast this,” said Jim

Hightower in his newsletter Hightower

Lowdown, “to only 9,200 privatized troops sent to the Gulf war by George’s

daddy in 1991. And the 100,000 number doesn’t count subcontractors, which would

add an estimated 20,000-40,000 more private troops” to the mix. Homeland

security is similarly being outsourced to private companies. The danger is that

government loses control over its own services when they are being performed by

private contractors. And Murphy reminds us that “before the Iraq war,

Halliburton itself used subsidiaries to do business with Iran, Iraq, and Libya,

despite official American trade sanctions against all three countries.”

Contracting with private enterprise to perform governmental service simply

takes governing away from government. And we’re well along this path, which,

Murphy maintains, is the way Rome went that led to its collapse.

Incidentally, despite all the hot

air being evacuated about troop withdrawal from Iraq, “withdrawal” is the wrong

word. “Reduction” is the right word. Remember all those massive military bases

that we build out in the Iraqi desert? We’ll be staffing those to the tune of

40,000-50,000 troops for the foreseeable future. And this vital information is,

at last, beginning to surface—in the pages of the Washington Post anyhow.

Farrago of Persiflage and Badinage

“When your work speaks for itself,

don’t interrupt.” —Henry J. Kaiser, Industrialist

“Virtue is insufficient temptation.”

—George Bernard Shaw

“Committee—a group of men who

individually can do nothing but as a group decide that nothing can be done.”

—Fred Allen, 1930s-1940s Comedian

BOOK MARQUEES

Rudy

Topffer Again. And Again.

Serious,

stoop-shouldered dusty scholarship in comics did not, probably, begin with

David Kunzle, but he is doing it with such unflagging diligence as to make the

rest of us muddlers look like the merest dilettantes in comparison.

(Well-intentioned and serious, no doubt, but weekend warriors of the tomes

nonetheless.) Beginning with his monumental two-volume History of the Comic Strip (Vol. 1: The Early Comic Strip, 1450-1826, in

1973; Vol. 2: The Nineteenth Century in 1990), Kunzle has persisted in scholarly scrutiny of static visual media

with the assiduity of a medieval monk, translating Ariel Dorfman and Armand

Mattelart’s How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist

Ideology in the Disney Comic and examining The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979-1992 and political

posters in Decade of Protest with

only intermittent distracting side-trips into Fashion and Fetishism: Corsets, Tight-Lacing and Other Forms of

Body-Sculpture in the West and From

Criminal to Courtier: The Soldier in Netherlandish Art 1550-1670. You’d

think he’d done enough, but, thanks to the perspicacity of the University Press

of Mississippi (one of my publishers, I confess), Kunzle, an art history

professor at UCLA, has now produced a brace of new volumes, creating another

landmark in comics scholarship, a veritable Publishing Event. Both canonize Rudolphe Topffer, the 19th century Swiss school teacher who invented the comic strip in graphic novel

format with the publication in 1827 of the first of eight such endeavors, Les Amours de Mr. Vieux Bois,

subsequently pirated by the French in 1839 and then by the Americans in 1842

under a new title, The Adventures of Mr.

Obadiah Oldbuck, a work that has lately been much touted as “the first

comic book” in America, albeit not an American production but the stolen fruits

of another culture.

It was Topffer (1799-1846), you’ll

recall, who perceived and practiced the blending of word and picture to achieve

a unique meaning, saying, in a definitive way that I’ve echoed in my own

musings on the subject: “The drawings, without their text, would have only a

vague meaning; the text, without the drawings, would have no meaning at all.

The combination makes up a kind of novel, all the more unique in that it is no

more like a novel than it is like anything else.” But, as we learn from

Kunzle’s critical biography, Father of

the Comic Strip: Rudolphe Topffer (220 8.5x11-inch pages in paperback, $25,

or unjacketed hardcover, $55), Topffer did more than sire a new medium. He was

a “Genevan schoolmaster, university professor, writer of short stories, novels,

travel accounts, and theatrical farces; art critic, aesthetic philosopher,

social moralist, polemical journalist, tireless correspondent; caricaturist,

illustrator and author of innumerable sketches of landscape and genre scenes.”

And “above all, the virtual inventor of the modern comic strip,” a

circumstance, Kunzle ruefully admits, nearly unacknowledged in the

English-speaking world due to the overweening assertions by Americans that

their fellow countrymen first concocted the art form in 1895 with the arrival

of Richard Outcault’s Yellow Kid. While Father is amply illustrated with the evidence of Topffer’s feat, the companion

Kunzle volume, Rudolphe Topffer: The

Complete Comic Strips (a magisterial 660 8.5x11-inch pages in hardcover,

$65), supplies the clinching testimony, all eight of the graphic novels, a

facsimile publication in their original dimensions, translated into English by

Kunzle, whose grandparents, he tells us, were all Swiss, which some may say

accounts for Kunzle’s consuming interest in the wayward schoolmaster. But I

say, that’s neither here nor there; the signal event is the arrival of this, the

first, English language publication of “Topffer’s entire comics oeuvre.” The

book “includes previously unpublished fragments of uncompleted stories,

segments of completed stories omitted from earlier editions of Topffer’s work,

and little seen preliminary sketches”—plus, the press release reveals, “a

chronology, a preface, contextual annotations, and explanations of material not

immediately understood today.” And “Kunzle comments on the differences between

Topffer’s original sketches and the final art as well as on the various

plagiaries, translations, and adaptations of Topffer’s work.”

I haven’t yet read either of these

fascinating books, but I have thumbed through both with increasingly eager

anticipation of the day that I’ll be able to sit down with them, and I can say,

without equivocation, that no one buying either, or both, of these volumes will

be disappointed. The critical biography, Father

of the Comic Strip, is, as I said, amply and edifyingly illustrated, and

the text puts Topffer into the cultural and artistic context of his times. And

it is far from dull reading. In his Preface, Kunzle displays a playful as well

as insightful sensibility: “Scholars and academics take nothing so seriously as

the comic. They should fear nothing more than grinding it into scholarly dust.

I hope this book does not love Topffer to death.” About the generally held

opinion that laughter is good for us, Kunzle says, “without getting at all

theoretical about this (theory exists in excess), let us just say that humor resists

the oppression of the daily social and political grind; like music, it relieves

heartache of the mind and body; it is medicine to the soul.”

You

have to admire scholarship that is gently risible as well as resourceful and

meticulous. In assembling this book, Kunzle consulted numerous other Topffer

scholars and dipped deeply into troves of Topffer correspondence and

miscellaneous writings. We gain great insight into Topffer’s thinking as a

result. His creative process, for instance, began with a doodle: he’d doodle a

face and then speculate about the personality behind the visage, evolving story

as well as an individual. Says Kunzle: “We may be glad, as Topffer eventually

confessed himself to be, that his weak eyesight prevented him from becoming a

painter. Instead, he became everything else. His weak eyesight, moreover,

taught him to draw rapidly and evolve the system of doodling that became his

hallmark.” Topffer elaborated on his theory in Essay on Physiognomics, which, Kunzle says, has embedded in it “a

whole modernist aesthetic theory ... cannily picked up by Gombrich in 1960.” In

the book’s final chapter, “The Legacy,” Kunzle discusses Topffer’s influence on

numerous other artists—in France, Gustave Dore, Leonce Petit, and Cham (Charles

Amedee de Noe); and in England, W.M. Thackeray, whose essential cartoonist

sensibility I’ve long intended to examine at greater length than I have so far.

Kunzle goes a good way along the route I hope someday to pursue myself.

The

Complete Comic Strips offers superb reproduction of Topffer’s oeuvre, at

the same size as their initial publication. Topffer’s novels engage in

light-hearted satire of a surprisingly modern tenor, as we can see from

Kunzle’s synopsis of The Loves of M.

Vieux Bois: “The fanatical pursuit of a Beloved Object [a woman], a Rival,

the duel, unjust incarceration and hair-raising escape, abductions, persecution

by superstitious, murderous monks, repeated suicide attempts, highway robbery,

resuscitation from the dead, a ghost, the pastoral interlude, excesses of

emotional self-indulgence, plus the sheer implausibility and bizarre

coincidences of the narrative twists—all this parodies cliches of romantic

fiction and the Gothic novel in particular. The namelessness and morose

supineness of the Beloved Object, comic in itself (how on earth could such a

supine creature inspire such heroic passion?) seems to mock the very concept of

irrational romantic love and the helplessness of heroines.” And throughout,

novel after novel, the pictures often contradict implicitly the ludicrous

pretensions of the text, supplying surpassing examples of the artistry of

cartooning at its best. Even if scholarship makes you roll your eyes, Topffer’s

comics will entertain as surely as anything you can find in the current crop.

From

the Historical to the Hysterical. Like many professional illustrators, humorous and otherwise, John Cuneo fills some of his

unencumbered moments between deadlines by doodling pictures in a

sketchbook—late at night, usually, while his creative engine is idling. Because

Cuneo is a cartoonist, probably, his sketches veer off into the comedic realm.

Maybe all cartoonists and illustrators in their otherwise idle hours produce

scatalogical and pornographic images like Cuneo’s, but we may never know: most of

them do not publish the graphic musings of their sleepless late nights. Cuneo,

aided and abetted by Fantagraphics, has, even though he never intended the

drawings for publication; until now, they were kept in a dark corner of an

obscure drawer in the furniture in his studio. The publication, entitled nEuROTIC in order to suggest the surreal

as well as the sexual nature of the work, is an absolutely outrageous tour de farce, an act, or acts—a

succession of irrepressible indescretions—of unfettered comic imagination, the

id gone hilariously wild. Don MacPherson at eyeoncomics.com says: “To say nEuROTIC is pornographic is completely

off the mark. This book does not titillate. It’s occasionally depraved,

sometimes challenging and often funny. This is a coffee-table book for those

who delight in shocking people, who see offending material as a means to

enlighten rather than frighten.”

But MacPherson is too cerebral for

me. Cuneo’s hysterically inventive images are “educational” in only the most

tortured meaning of the word. “Playful” is a much better description. “Playful”

in the polymorphously perverse sense that Freud doubtless had in mind when he

invented that term. Some viewers of Cuneo’s sketches have supposed,

erroneously, that they offer startling insights into their maker’s twisted

mental processes, and then, seeking to justify their own fascination with the

images, these critics claim Cuneo’s pictures are somehow universal revelations

of the human soul, shedding light on all of our sexual fantasies. Not so. Not

entirely. Cuneo’s pictures, one by one, reveal only how one image can lead to

another when a cartooning sensibility lets itself go and runs rampant. When

Cuneo pictures a man and a woman in such a way that the woman’s breasts become

the man’s eyes, the image may, if you are disposed to intellectualizing our

sexual preoccupations, reveal something about our voyeuristic engagement with

female anatomy above the navel, but the picture is also quite simply what it so

blatantly seems to be—the visual logical extension of one image, breasts, a

pair of them, into another, eyes, also a pair. But not entirely. The picture

also tells us something comical about our preoccupation with boobs.

We must believe Cuneo when,

interviewed by Tom Spurgeon at comicsreporter.com, he says: “These drawings

were never supposed to be published, and I guess that accounts for the slightly

untethered sexual content. They were just done for practice. I was trying to

resolve some drawing issues regarding my dissatisfaction with how I was

incorporating color into my line work. And overdrawing, not trusting my ‘line’

and figuring out the kind of ‘people’ that I wanted to draw—the proportions and

the types. So these started just as little exercises to relax and re-figure out

my ‘style.’ They are sexually oriented because I like that subject, and it

entertained me to draw middle-aged characters performing unseemly acts. I’m

also big on self-loathing, and enjoy coming up with ways to illustrate it. Of

course, now that these things are in a book, I’m desperately trying to convince

people that each image contains some deep universal psycho-sexual insight, but

I doubt anybody is buying it—the book or the insight thing. ... I guess if

there is an overriding ‘theme,’ it involves the intersection of lust,

ambivalence and the attraction/repulsion reflex towards the ways of the

flesh—and the anxiety that ensues. How can that not be a laugh riot?”

Cuneo also said his wife “wants to make it clear that none of the women in the

book are her.” So what we have here Among the earliest appearances of

comics-oriented 2008 calendars from Andrews McMeel is a desk calendar with a Zits strip on every page ($11.99) and a

spiral-bound appointment calendar of Dilbert Sunday strips ($12.99).

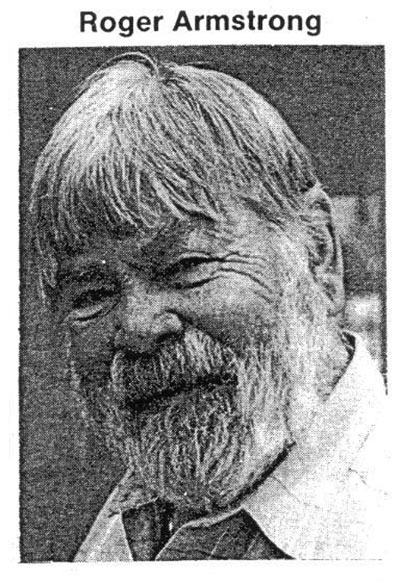

ROGER ARMSTRONG, 1917-2007

Cartooning’s Antic Raconteur Spirit

Roger Armstrong died of cardiac arrest on June 7, 2007, in California where he had lived all his sunny life. According to report, he left this life quietly, peacefully, with his artist wife Alice Powell and family at his side at Mission Hospital in Mission Viejo. At 89, Roger had seen a lot of 20th century cartooning as it transpired before his eyes, and with his passing, the medium has lost one of its better sprites. No—that’s not a typo for “spirit”: Roger was a sprite, a man-sized pixie with a gray beard and a haystack hair-do and dark Mephistophlean eyebrows, an archetypally elfin presence who saw the humor in humanity’s parade and delighted in it. Come to think of it, spirit is as accurate as sprite. I last saw Roger at the National

Cartoonists Society’s Reubens Weekend in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 2005. In his

Greek fisherman’s cap and alarmingly hued suspenders, he and Alice sat across

from me at a table on Sunday evening. Through the busy schedule of the weekend,

we had looked forward to spending some time together at this evening’s “roast”

of Sergio Aragones, where, we hoped, we could share stories and some laughs.

But we hadn’t anticipated the band. Loud and rocky, the orchestral din drowned

out any attempt we made at conversation.

“What are they thinking of?” Roger

exclaimed during one of the brief pauses between crescendoes. “We come to these

affairs in order to see old friends and talk with ’em, and then, during one of

the only agenda-free events of the weekend, the organizers bring in this

dreadful band so loud we can’t hear ourselves think, let alone speak!” His

diabolical eyebrows converged over the bridge of his nose, arching upward at

their outboard extremities. “Dreadful!” he emphasized.

I agreed, my outrage prompted

chiefly by a sense of deprivation at not being able to hear any of Roger’s

stories that night. And Roger loved to talk. He loved to tell stories about his

life in cartooning and some of the legendary but now mostly forgotten people

he’d worked with in the early days, and when he got going, he seemed figuratively

to hug himself with barely suppressed glee in anticipation of savoring, as he

told of it once again, some obscure moment in the lore of the craft, its

business, and its practitioners. Typically, his tales wandered a good bit as he

pursued anecdotal bypaths that invariably tempted him from the main

thoroughfare of his narrative: a description of Clifford McBride’s studio lead Roger to McBride’s concert piano, at

For several years after we made our

initial acquaintance, Roger believed that it was he who had started me writing

about comics and cartoonists. And he was almost right. But by the time I met

him in the spring of 1990, I had been writing about cartooning for almost

fifteen years—first in the fabled Menomonee

Falls Gazette, then in the legendary Rocket’s

Blast Comic Collector, and finally, in The

Comics Journal. Roger got me into Cartoonist

PROfiles, to which I subsequently contributed regularly for sixteen years

or so until it, and its founding publisher, Jud Hurd, expired at virtually the

same time. I met Roger through Shel

Dorf, founder of the San Diego Comic-Con and erstwhile letterer for Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon. Shel told me Roger was selling some of McBride’s

original Napoleon strips, but when I

pursued the matter, Roger said, no—not McBride’s Napoleon, but Armstrong’s Napoleon,

and not originals but high-quality prints. I bought one, was astonished at how

expertly Roger imitated McBride’s breezy penmanship, and asked him about it. We

talked on the phone for a while, and then, later, in a letter, Roger asked if

I’d be interested in doing an interview with him for Jud’s quarterly magazine.

Hurd had been after him, Roger said, to talk about his recent instruction book

about comic strips, published by the storied publisher of how-to books, Walter

Foster. I told Roger I’d be delighted to spend a few hours on the phone with

him, and so conversation ensued, and I then transmorgrified our talk into the

article that, now, follows (mildly up-dated with an occasional fact and a few

verb tense changes and the story about how Roger got into animation). Herewith:

ROGER ARMSTRONG drew cartoons more ways than most. A stylistic

virtuoso, he drew comic books in the styles of Disney, Warner Brothers, and

Hanna Barbera. He drew comic strips as disparate in manner as Clifford McBride’s classic Napoleon, Marge’s Little Lulu, Disney’s Scamp, and Ella Cinders, a soap opera continuity.

With that gamut of experience, Armstrong was the logical choice to author a

book on how to draw comic strips, and that’s exactly the title of the book he’s

done for Walter Foster Publishing. At this point, logic wavers.

Armstrong also worked in animation as inbetweener, animator, and story

director, but at 73 [his age at the time of our interview], he invested more in

the book than his experience in all sorts of cartooning. An accomplished

painter in watercolor and oil, he served as director of an art museum, and he

held an honorary doctorate in fine arts from the Art Institute of Southern

California. Logic reasserts itself: an instructor for over 20 years in all

phases of art from watercolor to figure-drawing to cartooning (mostly at the

Laguna Beach School of Art), Armstrong informed the pages of his Foster book

with the practical experience of teaching as well as cartooning. A graduate of

Chouinard Art Institute, he brought to cartooning the background of an artist

fully trained in the classical mode. But it didn’t begin that way.

It began with Zim and Clifford

McBride.

Armstrong at about eleven years old

was enthralled by the drawings of the great Eugene Zimmerman, whose book on

cartooning he borrowed so often from the library that no one else could check

it out. In recognition of his devotion to Zim, the librarian at last told him not to bother to bring the book back every two

weeks for renewal: “Why don’t you just keep it,” she whispered to him, glancing

furtively around to see that no one overheard her.

Young Roger also took the famed

Landon Course when he was in high school, and just about that time, Napoleon debuted (official starting date

for the daily strip, June 6, 1932, although the dog, unnamed, and his owner,

ditto, first appeared in a McBride miscellaneous weekend page dated April

13/14, 1929). Drawn with an exuberant pen and great verve, McBride’s strip

focused on a roly-poly bachelor and his giant pet dog, Uncle Elby and Napoleon.

Elby is forever dogged (pun intended) by misfortune: if his own bumbling

doesn’t frustrate his plans, the clumsy meddling of his affectionate over-sized

canine does. Elby was patterned visually after McBride’s uncle, Elby Eastman,

who was a lumberman in Platteville, Wisconsin; Napoleon was inspired by the

cartoonist’s dog, a St. Bernard, but in rendering the creature, McBride slimmed

him down until he looked more like an Irish wolfhound. This was before

cartoonists had made an accepted convention of talking animals in strips that

also featured humans, but Napoleon needed no words: McBride made the dog’s face

talk, giving it a range of expression that spoke volumes. “I saw Napoleon when it started in

the Los Angeles Times,” Armstrong

told me, “and I thought it was one of the most wonderful things I’d ever seen.”

And when he found out that McBride lived in Altadena on New York Avenue, he

resolved to meet the cartoonist. He took a bundle of drawings and knocked on

McBride’s front door.

“He was very gracious,” Armstrong

recalled. “And so I went to see him every so often.

I asked if McBride drew rapidly.

“That marvelous sketchy style,” I said, “—you couldn’t get the effect of such

breezy abandon by drawing slowly, I wouldn’t think.”

“Oh, no,” Armstrong said. “Clifford

was so fast. The guy was incredible. A little known fact about Clifford is that

when he pencilled the strip, he did not pencil it loosely. He pencilled it in

exactly the detail that you see the final pen-and-ink work. It was

unbelievable. I mean, he did every single bit — all the shading and everything

with the pencil before he went in to it with a pen. And he grabbed the pen way

out at the end of the holder— far away from the pen point — and he used to ink

that way. The control he had was absolutely unreal. He knew exactly what it was

going to do — where it was going — and he put it down. Not that he inked every

pencil line as it had been drawn; he didn’t. He was very fast. He developed

tremendous speed and freedom of line, and, of course, I did, too, watching him.

And that’s the way I draw today. I grab the pencil way out by the eraser. I ink

that way, too. I paint watercolors the same way. And I tell my students, Don’t

grab it way down at the end where you’ll get ink all over your fingers; grab it

as far back as you can conveniently control it.”

Armstrong sometimes helped McBride

with his jigsaw puzzle. “He was a great one for re-using old strips,” Armstrong

said. “He’d cut his strips into pieces and put them into an envelope, and then

if he needed to put together some stuff in a hurry, he’d shake it all out and

piece the panels together in a new arrangement. So he’d have me cut and paste

sometimes, and he’d let me do the extra drawing in the backgrounds to fit the

pieces together.”

The visits to McBride’s studio

continued through Armstrong’s high school and college years, and he’d sometimes

go with McBride to Bill Ortman’s Gambrinas on Euclid Street. “All the

newspapermen — artists, writers — they used to hang out there. And Clifford had

a special table in the back, and he and Ned Seabrook and all his cronies used

to hang out there, and that’s where I’d go and sit and talk with them. You

know, big stuff to a twenty-year-old. Neat place.”

A few years later, such

acquaintances led to Armstrong’s first comic strip job. After graduating from

Pasadena City College in 1938, he attended Chouniard for two years until

deteriorating family finances prompted him to leave school for a job making

airplanes at Lockheed in order to contribute to the Armstrong coffers. A

cartoonist friend told him that Fred Fox was looking for someone to draw Ella

Cinders during artist Charlie

Plumb’s illness. Fox had inherited the writing chores on the strip when its

co-creator Bill Conselman died only

a few years after the strip started on June 1, 1925. As originally conceived,

the strip gave the old rags-to-riches fairy tale a modern setting, retaining

the evil stepmother and selfish stepdaughters — over whom Ella triumphs by

becoming a movie star despite them.

During a three-month stint on Ella, Armstrong met Chase Craig, who, a

year or so later, summoned him to Western Publishing where he joined Craig to

produce the second issue (and many subsequent ones) of Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies. Starting in 1941, Armstrong first

drew “Porky Pig” over Craig’s scripts, then he wrote and drew “Sniffles and

Mary Jane.” Then when NEA picked up Bugs Bunny as a Sunday comic, Armstrong

inherited the strip after the first six (which were done by Craig) and wrote

and drew it for almost two years before Al

Stoffel and a couple others took it over. Armstrong did Bugs Bunny features

again at various intervals over the years, so he’s been associated with the

Warner Brothers star for almost as long as the wascally wabbit has been around.

He agrees that Bugs is THE American

comic character: he could never have been invented in the British Isles or in

France. “He’s brash, self-assertive, self-confident,” Armstrong said, “— the

prototypical American.”

Armstrong’s job at Western led to

his learning animation, which he did “not by choice,” as he explained to Mike

Barrier in 1975. “I had been able to avoid working in the animation industry,”

Roger said, launching into one of his oral rambles. “I had had an opportunity

to go to work for Disney, years before, in the old Hyperion studio. An animator

by the name of Bob Givens took an interest in me. I had come in contact with a

fellow named Frank Hawman, who had a comic strip called Sweetie Pie. The basic plot of Sweetie

Pie was one that was used many years later by a group called the Beverly

Hillbillies: it had to do with this desert rat and his little friend and their

burro, who strike riches—and with this incredible newfound wealth, they come to

Beverly Hills, they come to Hollywood—and it’s the story of their gaucherie and

the things that happen to them. Bob Givens had done a couple of sample strips

for this fellow Frank Hawman, and Frank hadn’t been terribly contended with

them. Bob didn’t do a very good job. Frank was still looking around, and

through Hank Formhals, [I got in touch with Hawman]. Frank turned out to be a

first-class jerk, but he introduced me to Bob Givens, and Bob offered to get me

into the Disney studio, but the whole concept of doing animation work was

abhorrent to me in that I liked to do all the work myself; and I preferred to

have something I could hold in my hand, like a comic strip, or a comic book—a

finished drawing that was published.

“So here I was, all these years

later,” Roger continued, “—four or five years later—and it was during the War.

One by one, the guys were disappearing into the vast maw of the United States

Army. I remember when Chase Craig went off to Fort Roach [Hal Roach Studios at

Culver City where a large contingent of cartoonists served their country by

making animated training films]. He was one of the Fort Roach commandos. He

didn’t wear a uniform for the first six months. Finally, they sent him down to

the quartermaster’s, and he came back with this funny Navy uniform, with the

bell-bottom trousers. About that time, they made him work in the barracks over

there, so he had to quit living at Miss Bell’s [a rooming house where Roger

also lived]. Anyway, the guys were disappearing, and it was narrowing down more

and more. I had married [my first wife] young, and I had a daughter, and the

draft board was taking younger people, and they weren’t touching me. Eleanor

Packer, Craig’s boss, who by then was running the joint [the Western shop] by

herself— over there in Beverly Hills—at the old Brighton Building—she began to

panic, all her people leaving, one by one, and she said, They’re getting

awfully close, and the first thing you know, you’re going to get drafted, she

told me. I think it was during that period that I did those Benny Burro things.

I can remember Eleanor shipping me off to MGM one day, and I looked at a whole

stack of those things. She said, We’ve got to get you into some kind of

deferred work. She cast about in her mind, and she thought, My old friend

Walter Lantz is doing Navy training films, and maybe if you’re in what is

considered essential war work, we will get you off the hook, and you will be

deferred, and then you will be able to stay and do all this nice comic book

work for us.

“I didn’t particularly relish the

concept of going into the Army myself,” Roger rolled on, “—what with an ex-wife

and a child—so I said, Okay. Evidently, she pulled the wires. She called Walter

Lantz, and he said, Send the guy over. So I went over and talked to Walter.

Walter was a nice little gnome-like man with a shock of white hair—very, very

friendly type guy. At the studio, he had this spook—I can’t remember the guy’s

name—I think his first name was Fred. He ran interference for Walter, and you

always had to get past this guy to see Walter. Anyway, I had an appointment, I

went over, I got past this guy Fred, and I got in to see Lantz. He said, Okay,

come to work next Monday morning. The hours were 8 to 12 and 1 to 5, I think. I

remember we punched in at 8 o’clock. Everybody came in the front entrance. It

didn’t make a damned bit of difference whether you were there on business, whether

you were a high mucky-muck or you were one of the peons—we all came in through

the front door. There was a little swinging gate.

“So Walter hired me, and I went back

and reported to Eleanor that all was well. She said, The catch is, you’re going

to have to continue doing your Sniffles and Mary Jane and your Porky Pig

stories. So I was confronted with the prospect of holding down two jobs in

order to stay out of the Army. That’s how I got into animation. It was a matter

of convenience for Eleanor Packer. And that was probably one of the toughest

years I’ve ever spent in my life. I would leave the studio at 5 o’clock—the

rest of the guys would go off, get drunk, whatever the hell they wanted to do,

but I could go back to my little room at Miss Bell’s and draw comic book

stories. I do not actually recall when I went to work at Lantz. I have a hunch

it was in April 1944. It would be easy to ascertain because all we’d have to do

is find out what month Virgil Partch left Lantz: he left a week before I went

to work there. He just quit and joined the Army. He and Sam Cobean had both

been working there, and they say the place was an absolute riot while those two

guys were working there.”

Not that the place was a model of

decorum when Armstrong was there. He recalled several instances of horseplay

among the animators for Barrier. “They used to take the newspapers,” he said,

“and they’d find pictures of girls in bathing suits. With a carbon pencil and a

kneaded eraser, they would remove the bathing suit and leave the girl

nude—leaving the Benday dots totally undisturbed. Then they’d put them up on

the bulletin board. That bulletin board got fuller and fuller and fuller with

these naked women, who had been clipped out of the newspaper. Xenia Beckwith

[one of only two women in the shop] got upset about it so she began to cut out

pictures of men, and she doctored them and put them on the bulletin board.

Finally, one day Walt came in and stopped in front of the bulletin board and

said, You guys have got to get this damned thing out of here!

“Incidentally,” Roger finished, “it

turned out I never did get a deferment out of it. I was finally drafted when

they began to scrape the bottom of the barrel. That year that I put in at

Lantz, aside from the tremendously fine experience and the people I met, didn’t

achieve the objective for which I’d taken the job in the first place. But I

learned a hell of a lot about animation because they were all eager to explain

and tell me things. I started as an in-betweener, then did breakdowns, and

finally became an assistant animator. But I was still doing the comic book

stuff for Western, too.”

After the War, Armstrong returned to

Western where he did a lot of Disney features for a while— “Little Hiawatha,

the Little Bad Wolf,” he remembered, “I did a whole bunch of Little Bad Wolf,

some of the best drawing I ever did. I had a real affinity for that stuff.” And

he went back to Chouinard Art Institute on the GI Bill.

Finding he couldn’t make ends meet

on the government’s allowance, he continued drawing comic books. “I’d go over

to Chouinard about 5 o’clock in the morning and sit in the backseat of my car

in the parking lot with a drawingboard and draw Bugs Bunny comic books until

school started. Then I’d go to class and then go home at night and do more

comic books. Pencilling only, this time no inking.”

[Some years after our interview, I

picked up some old Looney Tunes comics and was astonished to see the signature “Roger Armstrong” scrawled

distinctively in the last panel of a “Sniffles and Mary Jane” story. I sent

Roger a copy of the page and professed amazement at his being “permitted” to

sign his work at a time when most comic book cartoonists were anonymous. “I

both wrote and drew the feature at that time,” he explained, but “the signature

was an aberration, I’m sure: I do not recall being ‘granted the privilege.’ I

just signed ’em until the studio caught up with me.” He had other ways of

“signing”: in one 1949 Porky Pig tale, he makes “a cameo appearance in a

slightly altered persona as a cartoonist”—in the first panel on the third

tier.] Just as he was about to graduate

from Chouinard, Fred Fox called again. The syndicate wanted Plumb to retire,

and Fox needed someone to draw Ella

Cinders. Fox offered the job to Armstrong with the proviso that he take

Plumb’s assistant, Joe Messerli. Armstrong agreed to the stipulation, although at the time he thought an

assistant would be superfluous.

“I had a bad habit of thinking of myself

as the fastest draw in the West — which I partly was — and inexhaustible,”

Armstrong said. “But Joe turned out to be one of the blessings of my life, my

absolute mainstay. I can’t tell you how wonderful he was. And as I began to

encounter the problems of drawing that thing — Ella in particular—I cannot tell

you how happy I was to have Joe at my side.”

When Ella began her life destined to

be a motion picture actress, she had been modeled after Colleen Moore, a

popular movie star of the day — the hair-do, the eyes. And she was, Armstrong said, undrawable. “Why?” I asked.

“Because there’s nothing to hang on

to.” he explained. “She’s like Mickey Mouse. You see, you look at Goofy, and

Goofy has all kinds of facial structure. But Mickey has no structure. And

there’s no structure to Ella: she’s absolutely flat. You have to really become

accustomed to the space between the eyes, the two little dots, and the mouth —

the way that fits into the whole face. You almost have to measure it off with

calipers. And you miss a fraction of an inch, and you’ve missed it altogether.” Plumb had faced the same

predicament. And he had overcome it with outrageous ingenuity: he had invented

the Ella Cinders Machine.

“The Ella Cinders Machine was a

contraption Charlie Plumb rigged up

with pipes and sash weights and mirrors,” Armstrong said, his voice suddenly

smiling with infectious eagerness. “It was a sort of overhead projector, and

you could put a drawing of Ella into it and project it onto the paper and

reduce the size of the image or make it larger. It was a magnificent invention,

an absolutely ingenious device. And it was the only way I could draw Ella — by

tracing her from the projected image. There were two perfect drawings of Ella —

a profile and a three-quarters view. No full face. So we projected one of those

drawings onto the strips. We used only a profile or a three-quarters view in

every strip that was drawn. In various sizes. I let Joe ink the main characters

because when he came to me, that’s what he’d been doing for Charlie. And I did

the backgrounds and all that stuff — the figures. But I let Joe ink all the

faces.”

“That’s funny.” I said. “Usually a

cartoonist with an assistant does just the reverse. I understand Al Capp, for

instance, let his assistants draw everything but the faces of the main

characters. He never let them draw Abner or Mammy Yokum or Daisy Mae.”

“Well, Joe had more experience with

Ella and Blackie and Patches than I did.” Armstrong laughed.

The Ella Cinders Machine was only

the latest in Plumb’s solutions to the problem of drawing Ella, Armstrong told

me: before that, Plumb had used rubber stamps.

“At one point, he had rubber stamps

made of all the main characters,” Armstrong said, figuratively licking his

lips, relishing the outlandishness of what he was recalling, “—stamps of their

faces in every size and from every angle he thought he would need. And he kept

’em in this huge cabinet, specially built for the stamps. And if you wanted

Ella turned left, one inch high—they were all categorized in the cabinet, and

you’d go and pick out the one you needed and stamp it on an ink pad with

photo-blue ink on it, and you’d carefully stamp the strip with it where you

wanted the face. And then you’d ink it. Very cumbersome way to draw a comic

strip,” Armstrong chuckled.

“Yes, but it’s a classic,” I said.

“You always hear cartoonists muttering about the repetitive work in strips. I

remember a story about one guy, who came into the bar one evening, muttering,

Noses, he said, how I hate to draw noses — I spend my life drawing noses! And

you think about it, and you do: you spend your life drawing noses and the rest

of the faces of the characters you’re stuck with, And Plumb’s rubber stamps —

they’re almost too perfect an evasion of the onerous. Classic.”

At just about the time he started

working on Ella, Armstrong got

another phone call — this one from an old classmate from his undergraduate days

at Pasadena City College. It was Margot McBride, Clifford’s second wife, who

had worked on the student newspaper with Armstrong long before she knew

McBride. She remembered that Armstrong had helped McBride on Napoleon. It was 1950, and McBride had

just died. Margot wanted to continue the strip and engaged Armstrong to do it.

Suddenly, he was doing two comic strips at once. And each one was rendered in a

distinctive but wildly different style.

“How did you do that?” I asked him.

“I can understand being able to draw in different styles. I can do that. But I

have to think about it a lot as I’m doing it, and when I look at the drawing

afterwards, I’m likely to find mistakes — a thumb that’s drawn in the wrong

style, Style A not Style B. And I would imagine that you can train yourself to

avoid such slips if you take up a new style and do it steadily, but you were

doing two styles simultaneously — flipping back and forth. How did you manage

it?”

“No wonder I’m schizophrenic,”

Armstrong quipped. “Seriously, I just changed hats in the middle of the week,

changed my philosophic approach— my attitude about inking, for instance. Ella was done very meticulously, as if

it was carved out with a wire, whereas Napoleon was fast, fast, fast. Was it Shakespeare who talked about sea change? The only

thing I can say is that I changed. Right in the middle of the week. I spent

half the week on one strip; half on the other. A little more on Ella because it was more meticulously

drawn. It wasn’t that big a deal. I’d done stuff in other styles — Porky Pig,

Bugs Bunny. And I was painting at this time, too — landscapes.”

I wondered about the different

ambiance in each strip: “In your book, you say the strip cartoonist must create

a whole world, including the people in it. You have to believe in that world.

And there you were, living in two different worlds. How did you feel in

Napoleon’s world? In Ella’s?”

“Schizophrenic again,” Armstrong

said with a laugh. “To tell the truth, the McBride world, the world of Napoleon, was not a real world in the

sense that it had any depth. Berrydale, which is where Uncle Elby lived, was a

very ephemeral concept. But the world Ella lived in, which had no specific

name, had more content to it. When we got her into an adventure, she moved in a

much more real world. And in Napoleon, we were aware of people in the world there, but they did not constitute in my

mind a real world. Berrydale was a fantasy.”

“Funny you should put it that way,”

I said. “I’ve always felt the same about Napoleon. Every time I see a Napoleon strip, I

feel as if I am looking through a kind of gauze screen and seeing a bright,

hot, humid August afternoon where you can hear the faint buzzing of some kind

of insect in the trees and all other sound seems distant and removed, and

nothing really moves around very fast. A dream world, a languorous summer

afternoon sort of place. Somnolent, relaxing. But not, as you say, altogether

real.”

Messerli and, later, Mort Taylor,

helped Armstrong in the production of Napoleon as well as Ella Cinders. “They

researched for me,” Armstrong said. “When I first took over the strip, I

referred to Clifford’s stuff a lot. And they’d go through all the release