|

|||||||

Opus 205 (May 16, 2007). We meet the new monarch at King

Features and see what Betty and Veronica look like as Archie aims for the manga

crowd, and we list the political cartooners and the awards, including the

Pulitzer, they won during the last two weeks, and, finally, we discuss, one

more time, editorial cartoons that arouse the ire of the religious, and we look

at a smattering of comic strips that seem destined to do the same. Here’s

what’s here, in order, by Department:

NOUS R US

Candorville’s

Back

Spider-Man

3

Wealth

of Material for Editoonists in the Early Campaign

Dick

Tracy News

Pibgorn

at GoComics

Opus

No More?

New Monarch at King: Brendan Burford Takes the Editor’s Chair

Simpsons in Playboy

PEN MIGHTIER: The Sound of a Single

Voice Is Noisy Enough

But

Is That Good?

Cartoon

Gets Killed in Killed Cartoons Book

And

Other Prejudices about Political Cartoons

EDITOONERY: The Awards Season

Should

Pulitzers Go to Animated Editoons?

Cancer

Vixen Again

COMIC STRIP WATCH

Strips

Getting Edgy Some More

Doonesbury

Calls for GeeDubya’s Impeachment

Funky

Winkerbean and Lisa Moore’s Cancer

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE

Captain

America and Serious, Grown-up Marvel

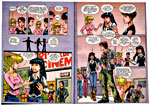

Betty

and Veronica Get New Looks

DC

Comics Goes Backward

BOOK MARQUEE

B.C.

Retrospective Tome

Ditto

Blondie

Other

Heroes Includes the Oft Excluded

Art

Out of Time Reviewed, Copiously

The Alternative List to Time’s 100 Most

Influential

And

our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by

clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just

this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned.

Without further adieu—

NOUS R US

All the News That Gives Us Fits

The

good news is that Darrin Bell’s superlative

strip of political and social satire, Candorville,

is back daily in the Los Angeles Times,

starting Monday, May 14; because of the greater lead time for producing color

comics, the strip won’t return to the Sunday funnies until early June, saith

Sherry Stern, Deputy Features Editor. This happy development is doubtless

brought on, at least in part, by the outcry from Candorville fans when the paper dropped the strip several weeks

ago. The power of protest is asserted once again. The power of protest is not,

however, an unalloyed blessing; see “Pen Mightier Than Sword (Also Funnier)”

below.

I was in western Nebraska when

“Spider-Man 3" opened so I missed the excitement at the local comic book

shops on the next day, Free Comic Book Day (FCBDay). The Lincoln Journal Star announced the movie’s opening with an

illustrated banner atop Page One—a picture of a swinging web-slinger captioned

“a popcorn movie masterpiece.” In smaller type, it added other fascinating

bits: Spider-Man’s name is hyphenated because Stan Lee wanted to further

differentiate the character from Superman; Peter Parker’s middle name is

Benjamin; and “Spider-Man 3" cost $250 million. But inside, the reviewer

implied the movie’s budget was $500 million. The New York Times is no more certain: “The movie may have cost more to

make than any film in Hollywood history. Sony put the budget at $260 million,

with additional marketing costs of about $120 million, but some published

reports have placed the budget at above $300 million.” And maybe, whatever the

cost, it was worth it: “Spider-Man 3" broke all box office records for its

opening day and the weekend that followed, “domestically and internationally,”

said Sharon Waxman at the NY Times: $148 million for the opening three days, $59 million of it on Friday, both

figures higher than the previous record-holder, “Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead

Man’s Chest.” And it took in an estimated $227 million in 105 foreign markets,

“outstripping the previous record-holder, ‘Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of

the Sith.’” Most of the reviews are enthusiastic. Some quibble about the

multiplicity of plots—three separate good-guy-vs.-bad-guy rivalries and too

many “high-energy showdown set pieces.” “They eventually start to come off as

indistinguishable and adverse to story flow,” said Sally Kline at the Washington Examiner. But

director/co-writer Sam Raimi earns kudos for “taking CGI special effects to a

new level and for infusing a higher degree of character complexity to the

comic-book superhero genre.” Sony is already talking about another Spider-Man

sequel even though this third flick was supposed to be the last in the line.

One caution: “Spider-Man 3"’s big box office is partly the result of not

facing much competition in the way of another action flick on the opening

weekend.

As for FCBDay, the bloom is

apparently off the rose. Most accounts report enthusiastic raves by shop owners

and operators, but the shops in my hometown are only lukewarm fans of the

freebie foray. The give-away comics bring in a few scads of visitors who

wouldn’t otherwise cross the threshhold of a comic book store—so the increased

population in the shops creates an aura of excitement—but it seems these

mini-hordes are not magically transformed into regular paying customers. Since

shops must buy the comic books they are giving away, FCBDay is a financial

investment for shops: it must pay off somehow. One shop makes its money by

discounting racks of books, which are bought by some of the guests who came in

looking for freebies. Another shop—on campus, which means it has a regular

clientele of comic book buyers—doesn’t participate in FCBDay by getting any of

the free books; instead, it discounts heaps of books from its backstock. In

other words, FCBDay can be made to pay off for comic book shops, but perhaps

not in quite the way the founders of the event hoped.

With the retirement of Tony Blair,

Britain’s famously savage political cartoonists display mixed emotions. Independent cartooner Dave Brown’s feelings are typical: “I

detest the man and what he’s done, but he was great to draw. You put all that

bile, hatred and angst into drawing.” As the “war” in Iraq wore on, according

to Peter Graff at Reuters, the caricatures of Blair became more and more venomous:

originally likened to Bambi, he eventually appeared as a vulture, perched on

coffins, surrounded by hellfire and covered in blood. Increasingly, he looked

decidedly evil or deranged. Blair’s presumed successor, Gordon Brown, offers

less opportunity for good caricature. “He’s a bit duller,” said Charles Griffin, onetime staff

cartoonist at the Daily Mail and Mirror.

But Conservative leader, David Cameron, heir of Margaret Thatcher and John

Major, presents a more promising visage. “He’s got a good face to do,” said

Griffin. “It’s quite sort of rubbery. Shiny forehead. Starey eyes. Maybe he’ll

be prime minister instead of Brown one day, and that’ll save me.”

On this side of the Atlantic, we are

fully submerged in the miasma of the 2008 Presidential Campaign. Already. Some

of us, caught starkly unaware, wonder why it should take two years out of a

political leader’s life to run for President. During that period, none of the

candidates will have time or energy to perform any useful public service, a

shirking of responsibility that demonstrates their unfitness for the White

House or any other political office. And voters will quickly reach a state of

ennui so paralyzing that they’re unlikely to go to the polls when the occasion

arrives. In short, a 2-year Presidential Campaign seems a bootless enterprise

for all concerned. Except for tv pundits and Sunday gasbags, who need something

to talk about, endlessly. Obviously, the 2-year contest has been arranged

exclusively for their entertainment and convenience and no one else’s. Except

maybe political cartoonists, who contemplate various delights.

Signe

Wilkinson of the Philadelphia Daily

News, while depressed by the endless “war” in Iraq, nonetheless looks

forward to Hillary Clinton’s campaign, reports Dave Astor at Editor & Publisher, and Glenn McCoy of the Belleville (Ill.) News-Democrat is rubbing his hands in glee at the thought of what he can do

with Barack Obama. McCoy, one of relatively few conservative editorial

cartoonists nation-wide, is also delighted that the Democrats control Congress.

“When the party you’re opposed to is in power,” he said, “it makes a

cartoonist’s job a little easier.” Mike

Thompson at the Detroit Free Press voiced

the opposing view: “Since the majority of political cartoonists are left-leaning,”

he said, “a Democrat-controlled Congress will prove a challenge.” Said last

year’s Pulitzer-winner, Mike Luckovich at

the Atlanta Journal-Constitution: “Divided government means more conflict, which is better for cartoonists,” but,

he added, “most cartoonists, even if they’re sympathetic to a party or

candidate, are going to hit them if they do something stupid or hypocritical.”

Several of the cartoonists Astor talked to said good-looking candidates—like

Obama, John Edwards, Mitt Romney—are hard to caricature. People like Donald

Rumsfeld, on the other hand, are easy. “I find it hard to miss Rumsfeld on any

level,” joked Thompson, “but he was so wrong on so many things that he made

great cartoon fodder.” Clay Bennett at the Christian Science Monitor quipped that Rumsfeld, notorious for asking rhetorical questions, is “the only

guy I know who could hold a press conference without anyone else in the room!”

Although editoonists are initially excited by the prospect of fresh targets

that is offered by a Presidential Campaign littered with so many candidates,

once the “race” gets down to two or three possibilities, the challenge mounts.

With fewer candidates, the number of opportunities deserving a cartoon is

reduced, and sound-bite news coverage of the campaign reduces even further the

topics worthy of ridicule. Every cartoonist is soon faced with the same

dilemma: how to do a cartoon that is different from the cartoons done by his

colleagues when they are all looking at the same limited range of possibilities

and provocations. Instead of rejoicing at the advent of another Presidential

Campaign, many editoonists groan in exasperation.

The Tintin film project seems, at

last, underway. With an announcement that preceded by only a few weeks the 100th anniversary of the birth (May 22) of the character’s creator, George Remi, Nick

Rodwell, the second husband of Herge’s widow,

said Steven Spielberg and DreamWorks will begin pre-production soon. According

to Anne Feuilere at expatica.com, it has not yet been decided whether the film

will be a live-action feature, a traditional animated film or CGI—or a mixture

of all three. Four of the Tintin adventures are being considered: The Blue Lotus, Tintin in Tibet, The Seven

Crystal Balls and Red Rackham’s

Treasure. Until a few weeks ago, I’d never read any of the two-dozen Tintin

books; I was saving them, I suppose, for my old age. Or an appropriate

occasion, whichever came first. I’m happy to report that both have arrived, and

I’m wading through the oeuvre. Sometime later in this anniversary year, I’m

likely to regale you with my reaction to all of it, or as much of it as I can

manage to read in the number of sittings permitted me. Consider yourself

warned.

Lynn

Johnston will receive the Order of Manitoba, the Canadian province’s

highest honor, in July. The distinction, established in 1999, “recognizes

excellence or achievement in any field of endeavor that benefits the social,

cultural or economic well-being of Manitoba and its residents,” according to

CBC News. In her strip, For Better or For

Worse, Johnston told a story about Elizabeth Patterson’s teaching

adventures in an aboriginal community in northern Manitoba. ... In Woodstock,

Illinois, the Chester Gould Dick Tracy

Museum is poised to launch The Sunday Project in conjunction with the famed

strip’s 75th anniversary year. The Project will reproduce Dick Tracy Sunday strips from May

through December of 1932. Scanned in high resolution and reproduced

tabloid-size on 11x17-inch medium-weight paper, the Sunday pages are available

for purchase by subscription. Several “Specialty” pages—of celebrated events in

the cleaver-jawed sleuth’s life—are also offered. (For details, visit www.chestergould.org and/or http://www.chestergould.org/navigation/news/TheSundayProjOrderForm.pdf )

Continuing the festivities, the 75th Anniversary Retrospective Art

Exhibition, “The Art of Dick Tracy—75 Years of Crooks, Dames and Fedoras,”

offers a decade by decade history of the strip, exploring the growth and

development of its title character, the changing nature of crime in America,

and the aesthetic changes that took place during the strip’s first 75 years.

The exhibit will open during the annual Dick Tracy Days weekend in Woodstock,

Friday, June 22. By the way, the second volume of the Complete Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, Dailies and Sundays: 1933-1935 is

out, and it is as handsome a production as the first. Reproduction of these

vintage strips is pristine, the best I’ve seen anywhere. The volume, printing

two strips on each generous 7x10-inch page, bound sideways, includes, in

addition to strips from May 1933 through January 1935, the second half of an

interview conducted with Gould by Max

Allan Collins, consulting editor for the series and Gould’s successor in

writing the strip; Collins also supplies introductory essay, beginning, “By May

of 1933, Chester Gould was feeling his oats, writing and drawing his innovative

detective strip....”

Among the phenomena in Iraq brought

on by the American invasion is a plethora of newspapers: in the warm sunlight

of freedom of the press, newspapers sprouted up all over the place. Ditto

political cartoonists. But their number is diminishing, according to Hammoudi Athab, head of the Iraqi

Cartoonists Association. The group presently has about 50 members, according to

Athab, quoted in USA Today; “but

dozens of cartoonists have fled Iraqi’s violence.” Cartoons are high art in

Iraq—as they are in many other countries where illiteracy is widespread and

cartoons therefore serve as the chief means of spreading news and opinion. In

Iraq, a newspaper’s cartoon is often the first thing a reader turns to. Iraqi

cartoonists tackle a much wider range of subjects than their American

counterparts, who tend to focus on politics almost to exclusion of all else. In

Iraq, corruption, kidnappings, government inaction, and the U.S. military are

frequent topics. One thing none of them tackle—the Prophet Mohammad. Iraqi

cartoonists draw more cartoons than Americans. Typically, an editoonist in the

U.S. does little more than a cartoon a day. Omar Abdel-Ilah, who cartoons for the Baghdad-based Al-Ta’akhi, says he draws about 20

cartoons a week. “But that increases if there is a lot of news in one week,” he

added. Each day, he scans the previous day’s edition and then grabs his pencil

and a pad of paper. It takes him less than 15 minutes to start a drawing, he

said. His editors, thinking of their own safety and his, sometimes recommend

that he be a little less caustic about local satraps. As in many other

countries, Iraqi cartoonists are often the targets of political revenge. One of

the most popular Iraqi cartoonists died of a heart attack in November 2005 just

after getting a death threat. Another survived an assassination attempt last

year but is physically unable to work.

Brooke

McEldowney’s online color comic strip, Pibgorn, is leaving its United Media website to take up at GoComics, the distribution

portal for uclick, the digital entertainment provider division of Andrews

McMeel Universal. A new installment of Pibgorn appears Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, but, starting at GoComics on May 14,

the last month’s strips run at United Media will be re-run in order to lead up

to the conclusion of a storyline that was interrupted by the site shift and

left unfinished. Pibgorn was born in

2001 as one of United Media’s long tradition of Christmas season strips.

McEldowney clearly fell in love with his blithely mischievous fairy character

and decided to continue her adventures as she spreads enchantment in a less

than enchanted world. Said he: “Ever since Pibgorn’s inception, it has been a growing, evolving and at times highly experimental

entity all its own. Now, moving on, I feel as a parent does when enrolling his

child in a new school—all new teachers, new rules, new atmosphere, new

playgrounds. I just hope the other kids don’t pinch.” Online, Pibgorn has been “a sensation,” said

GoComics CEO Chris Pizey. It enjoys about 10,000 subscribers, McEldowney told

me. Incidentally—just to keep you aware of my possibly dubious motives in

mentioning the site—GoComics carries a nearly brilliant blog about comics and

cartooning: it consists entirely of R&R out-takes—just snippets and

abridgements though, fragments dribbled out a little five times a week. Here at www.RCHarvey.com is the only place you can find the Complete and

All-encompassing Rancid Raves, posted whole and uninterrupted. Rejoice.

Opus No More? Berkeley Breathed, who can’t seem to make up his

mind which of several professions to adhere to, was caught muttering about the

impending “death” of Opus when interviewed by Mike Shea and the Texas Monthly recently. The topic of the

interview was ostensibly Breathed’s latest children’s book, Mars Needs Moms, but when he was asked

what projects were on the horizon, Breathed said: “Three—a novel; two of my

books in development at Disney; and Opus’s death, which approaches.” By “Opus,”

Shea pressed, did the cartoonist mean the comic strip or the character? “I mean

the death of Opus literally,” said Breathed, “as told in the comic, which means

the suspension of the feature (no dates set as of yet).” Shea: “Are you serious

about killing off Opus in the strip?” Breathed: “Yes, but my wife would leave

me, she reports. I have to factor this in.” Shea: “Do your publisher and newspapers

know this?” Breathed: “They know that all good things come to an end. I’d like

to see Opus go out with George Bush, both headed into the sunset.” Breathed is

being cute, of course: one could assume, from the whole context of this

exchange, that he is alluding to the imminent demise of print newspapers, not

just his strip or character, both of which would cease with the expiration of

hardcopy journalism. But it’s hard to say for sure. See what you think at http://www.texasmonthly.com/2007-04-01/bookreviews.php.

The verdict is still out about the

alleged death of newspapers. But it doesn’t surprise me that Breathed is going

to abandon his flightless fowl once again, as he’s done twice before. As soon

as he acquired ownership of his first nationally syndicated strip, Bloom County, where Opus originated,

Breathed discontinued the strip, offering in its place a Sunday only feature

called Outland, which was to have

starred a waif named Ronald Ann but into whose orbit Opus soon spun. Then, after

a couple years, Breathed gave up on Outland, too. Presumably, he discontinued Bloom

County in order to escape the garroting grip of deadlines for a daily

strip. He thought his life would be easier with just a Sunday strip. While his

life was probably easier, it was not as festooned with fame as it had been

under the 7-day regimen. Nor was it as lucrative. With both ego and purse

hurting, Breathed turned to other ways of exploiting his storytelling

talent—namely, children’s books, of which there may be as many as six since

1991. But he clearly missed the platform that a nationally distributed comic

strip provided for commenting on social and political issues, so in December

2003, he revived Opus in the current incarnation, a Sunday strip bearing the

penguin’s name. Breathed elbowed his way into the Sunday funnies by insisting

that editors publish the strip at half-page size, promising spectacular art to

justify the excessive allotment of space. To advance his crusade with editors,

Breathed dumped on all older strips, particularly those no longer being

produced by their originators, saying they were undoubtedly inferior due to

their age and editors should kick them out of the paper to make room for newer

enterprises, Opus in particular.

Opus never fulfilled Breathed’s promise: it was not spectacular art. And I suspect

that its circulation was not as robust as Breathed hoped for. Once again, as he

discovered with Outland, a strip

without notoriety and circulation isn’t enough to sustain his continuing interest;

so now, he’s contemplating giving it all up. Again. I am, admittedly, being

cynical and probably unfair to Breathed: no one should expect a cartoonist to

expend time and talent on an enterprise that isn’t rewarding emotionally as

well as financially. But I can think of no other explanations for his on-again

off-again behavior. Breathed is, after all, a child of the 20th century’s last half, during which we’ve seen several stunningly talented

syndicated cartoonists elect not to spend their entire lives at the drawing

board, chained to deadlines. Bill

Watterson. Gary Larson. Frank Cho. Aaron McGruder. Michael Jantze. And now,

again, Breathed. These defections may be symptomatic of the times. Lifelong

indentured servitude seems a thing of the past. And maybe that’s just fine. In

the realm of funnybooks, we’re getting a superior product on a mini-series

basis—and probably because of the mini-series as a genre. Hellboy shows up every

now and then, whenever Mike Mignola gets a good inspiration, we may suppose, instead of plodding on, issue after

clockwork issue, in order to obey the dictates of a publication schedule rather

than the impulse of creative inspiration. Ditto Mad Man, Michael Allred’s idiosyncratic concoction. What sloughs of inferior

effort could Superman have avoided had he been featured in mini-series instead

of regular, monthly titles? Then again, had the mini-series been viable back in

the 1930s and 1940s, perhaps Superman would not have lasted as long as he has

because he would not have been a presence long enough or steadily enough to

nurture a following. Who can say? Not me. Not right now.

Right now, it’s enough to pause a

bit to celebrate the evolution of cartooning venues that stimulate creativity

rather than stultify it through sheer clock-punching regularity. But before you

dash off, read Shea’s interview: Breathed is a delightful if cynical wit.

Insightful, too. Commenting on his new children’s book, Breathed says that it

is his “first fully digital paintings. It’s a revelatory artistic experience,

making a computer create artwork, but a deeply distressing one as well, as at

the end of the day, you’re not holding a painting. It is only light. I haven’t

quite come to terms with this.” Neither have many colorists. As I mentioned

before, some comic book pages are colored much too dark, probably because the

colorist is looking at his/her work on a computer, and the light, coming from

“behind” the drawings, illuminates the colors, making them seem brighter; but

when printed in ink on paper, the colors, once so bright and gleaming, are

dark, too dark, sometimes, obscuring the artwork they are intended to

embellish.

New Monarch at King. Jay Kennedy’s assistant, Brendan Burford, was named comics editor of King Features Syndicate

at the end of April. The appointment was announced by T.R. “Rocky” Shepard III,

president of the company, who said: “The recent death of our editor-in-chief,

Jay Kennedy, was a terrible blow to everyone, both at King Features and

throughout the industry. However, as he did in all things, Jay had planned for

the inevitability of succession one day when he hired Brendan Burford. Brendan

has worked side-by-side with Jay for the last seven years and brings to his new

position a broad knowledge of the comics and the cartoonists we represent as

well as a deep love for the art form. I am confident that he will lead King

Features to even greater success as he continues the search for new cartooning

talent that Jay Kennedy so ably mastered during his 20-year tenure.”

Expressing his gratitude for

Kennedy’s tutelage—“my mentor [to whom] I owe many of my professional

successes”—Burford said he was honored and “thrilled to be able to carry on the

tradition of excellence” sustained by Kennedy and was “looking forward to the

growth we’ll continue to enjoy over the years.”

In an interview with Tom Spurgeon at

ComicsReporter.com, Burford said he has lived and breathed comics all of his

life—ever since he could read, “since I could pick up a pencil.” He is a

cartoonist himself, albeit not syndicated (his wife, though, Rina Piccolo, is syndicated through

King with her strip, Tina’s Groove).

A graduate of the School of Visual Arts in New York, Burford served a year as

an editorial assistant at DC Comics before joining King in January 2000, first as

an editorial assistant, then assistant editor and, finally, associate editor.

Producing an irregularly published anthology of cartoon reportage, Syncopated, he is a small press editor

and publisher. With these credentials, Burford brings an unusual background to

bear on syndicated comics. Others of his predecessors have been

cartoonists—both the legendary Sylvan Byck and Bill Yates, Kennedy’s immediate

predecessor, were cartoonists; but none of them were as young as Burford. He’ll

be 29 soon. But youth at King is hardly a disadvantage: the syndicate’s

founder, Moses Koenigsberg (whose name, Anglicized, gave the enterprise its

name) was only 35 when he laid the groundwork for the syndicate in 1913.

In his interview with Burford,

Spurgeon asks questions that are both penetrating and informed (Spurgeon

co-produced a King-syndicated strip, Wildwood, for several years); I recommend you visit www.ComicsReporter.com to partake of the whole enchilada, but I’ll excerpt some of it here.

From the start, Burford said, his

boss, Jay Kennedy, was grooming him to be his successor, giving the younger man

experiences that would equip him to assume the editor’s chair. The two worked

closely together on many projects; separately on others. Kennedy was King’s

editor-in-chief, which meant he supervised syndicated columnists as well as

cartoonists. Burford, as comics editor, will concentrate only on comics,

leaving the columns to another of Kennedy’s assistants, Glenn Mott, who, like

Burford, worked under Kennedy’s supervision. Mott and Burford are now editorial

equals on the organization chart.

In selecting new comic strips,

syndicate officials often look for a demographic “hook” to hang the new work

on. One of King’s new launches in the last few years, for example, is Retail, a humorous look at the world of

retail workers. “We wanted to appeal to this part of the demographic,” Burford

explained. “It makes perfect sense. It’s [aimed at an audience] not represented

[on the funnies page]. Something like 33 percent of the U.S. workforce has

worked in retail at some point in their life.” But canny syndicate editors know

that looking too intently for a demographic can blind them to works of genius

that don’t seem to fit anywhere—Calvin

and Hobbes, for instance. Surgeon wanted to know how Burford balanced the

two.

Burford pointed to the recent

re-alignment of strips on the nation’s comics pages when Bill Amend stopped doing the daily FoxTrot. There was, Spurgeon observed, no clear demographic

successor. Burford agreed. “It had a uniqueness,” he said. So editors who went

looking for a “logical demographic replacement” couldn’t find anything.

Instead, they picked up whatever strip was on their Wish List—Zits, or Mutts, or Pearls Before

Swine. “Whatever was first on their list, they put in. Tina’s Groove picked up a lot of slots,” he continued, “—and Tina’s Groove and FoxTrot are two very different strips in terms of demographic.” He

concluded: “What it taught me and I

imagine the other syndicates as well was that this whole ‘This is the logical

replacement for the strip because it meets that old strip’s demographic need’

—that’s all bullshit.” He talked briefly about a new strip that he will take to

his May sales meeting: “It’s a very simple premise. It’s not necessarily hook-laden.

It’s a unique cartoonist with a unique voice.” And that’s how they’ll sell it.

“My default setting,” Burford said,

“is to go after the voice. I always defer to someone I think is a talented

person, and I try to let their talent and their impulses shine through more

than some kind of contrivance, some kind of concoction.” He added that he and

Kennedy often went looking for something that would fit in the syndicate’s

marketing effort rather than waiting for a work of genius to come flying in over

the transom. Sometimes they looked for something to fit a demographic hole;

sometimes they looked for a way to engage a particular cartoonist on a project

that cartoonist would find amenable. But they always kept an eye on the

transom.

Remembering his experience at DC,

Burford laughed about the preference in comic book circles for the designation

“illustrator” as opposed to “cartoonist.” Said he: “I don’t care if you’re Frank Frazetta or Charles Schulz or anyone in between, you’re a cartoonist. A few

people are illustrators,” he conceded, “but most are cartoonists.”

Towards the end of the interview,

Spurgeon observed that Burford is now “the face of King Features to a lot of

people.” Burford demurred: “The face of King Features is the comics,” he said.

Nude Simpsons. Various so-called news outlets have let it slip that

Bart Simpson will appear nude, full frontal, in the impending Simpsons movie.

It happens, Newsweek alleged, in a

nude skateboarding scene. Creator Matt

Groening denied that Bart will lose his virginity in the film. In an

interview published in the June issue of Playboy, Groening said: “You will see nudity, but it’s not who you want to see

naked.” Bart? No: Groening didn’t say, exactly. Other cullings from the Playboy interview:

Despite the numerous demands of the

tv series and the movie and merchandising, “About once a week, on Thursday,”

Groening said, “I suddenly remember I have a weekly comic strip to write.” Life in Hell is “the one thing I still

do completely on my own,” he said. “I’ll take full blame for everything,

misspellings and all.” He started doing the strip while he was working at a

photocopy shop, and if we are to judge from the appearance of the strip in

recent years, he usually resorts to those devices to produce the strip. I

haven’t seen a Life in Hell strip for

years that wasn’t the same drawing, repeated ad infinitum.

Groening named Homer Simpson after

his father, but his dad was “nothing like the character.” And then, later,

Groening continued, “I named my son Homer in part trying to prove to my dad

that I had the best intentions. I wasn’t just trying to get back at him for

some perceived slight.”

Bart Simpson was inspired by Hank Ketcham’s Dennis the Menace, the tv incarnation. “I remember the premiere

episode of ‘Dennis the Menace’ in 1959, the animated opening sequence of this

Tasmanian devil-like cyclone spinning out.” Out of the cyclone came—the

“menace,” a kid! “I was so excited,” Groening went on. But then came

disappointment: “It turned out to be this fairly namby-pamby pseudo-bad boy who

had a slingshot but didn’t ever seem to use it. Bart Simpson is basically what

Dennis should have been.”

Awash in Simpsons licensed products,

Groening said: “I had a rule that none of my Life in Hell characters would ever endorse anything—except Akbar

and Jeff, who would endorse anything.” This gives you an idea of the sort of

comedy that infects Groening’s response to every question; the cartoonist is an

unrepentant and unrelenting wise-ass.

Now divorced, Groening is dating

again. “Dating’s no fun,” he opined. “Unfortunately, it’s part of the process

of getting to know someone. I once said, ‘Love is like a snowmobile racing

across the tundra and then suddenly it flips over, pinning you underneath. At

night, the ice weasels come.’ A lot of people have that on their MySpace page.”

Also in this issue of Playboy is an essay by Daphne Merkin.

Entitled “Penises I have Known,” it does for this much abused appendage what

Christopher Hitchens did for the blow job in Vanity Fair some months ago.

Still with Playboy, last month’s issue—wouldn’t you know—was replete with a

portfolio of photographs of, yes, Anna

Nicole Smith. “Hers is a sad story,” commented writer Kevin Cook, author of Tommy’s Honor, “but as Hef said, it

would have pleased her that people will still admire her pictures.” Yes, sadly,

I suppose so. But there’s no way this display can be seen as anything but one

last exploitation of the woman’s bosom and derriere.

Fascinating

Footnote. Much of the news

retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics.

It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into

cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are

Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com,

and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike

Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com

Read and Relish Department

Slabbing

comic books, the practice of sealing them forever between hunks of transparent

plastic, is a perfect satirical caricature of the collector’s mania, which is

to own, not to enjoy. —RCH

“Common sense and a sense of humor

are the same thing, moving at different speeds. A sense of humor is just common

sense, dancing.” —William James.

PEN MIGHTIER THAN SWORD (ALSO FUNNIER)

In

the March issue of Slice of Wry, the

monthly newsletter of the Southern California Cartoonists Society, the

President, Karyl Miller, tells of

her adventures as a tv mogul. “Back in the late 80s,” she writes, “I wrote and

was supervising producer on a sitcom called ‘My Sister Sam,’ which starred Pam

Dawber and Rebecca Schaeffer as sisters. We weren’t the biggest hit, but CBS

liked us enough to renew us. We were half-way into our second year when

suddenly the network fell out of love with us. How could we tell? Well, a

network rejects you just like a lover rejects you. He doesn’t return your

calls, doesn’t beam at the sight of you, and never mentions the future (because

there isn’t going to be one). So ... wha hoppen? Our show made a big boo-boo.

We broadcast an episode where the Dawber character has casual sex with no

regard to its impact on her teenage sister. Nobody wanted to see this

story—especially not at 8 p.m when impressionable children were watching. At

least, that’s what the angry viewer letters said. And soon, we were history.

“So guess how many negative viewer

letters it took to cancel this show. 20? 18? Nope. Out of millions of viewers

it took only five little ol’ viewers letters to get us the boot. Why? Because

most people don’t write a letter so the ones who do write are given extra

special consideration. Most people are lazy when it comes to sitting down,

forming a thought and committing it to paper. And that’s still true today. The

Nielson rating company estimates each angry viewer costs the show roughly one

rating point or 900,000 viewers. So to CBS, those five angry people meant four

million, five hundred thousand fewer viewers, which meant less advertising

income, which meant we were toast.

“Point: It’s actually possible in

this increasingly indifferent society to have an impact on things you care

about if you make your opinion heard. All you have to do is write a letter! And

if you spellcheck it and don’t swear—all the better! And if you sign your

letter and add your town and phone number, you’re going to be batting 1,000 in

the credibility department.”

Miller’s ultimate point was that

comics fans who are upset with newspaper editors’ decisions about their paper’s

comic strip line-up—which strips to drop; which strips to add—can affect the

decisions by simply writing in. “If they stick us with some stupid strip we’ll

have only ourselves to blame. And anyway, today when newspapers are getting skinnier

and skinnier, isn’t it important the editors know that many, many readers still

love the funnies and care about the funnies? So everybody—out of the kitchen and into the

streets!”

As wonderful as Miller’s insight

into decision-making in the media is, it is a chilling vision: it reveals just

how few voices are affecting decisions that are far-reaching. In my

neighborhood recently, the University of Illinois banned its mascot, Chief

Illiniwek. The Chief had been a presence on the campus since 1926, most

conspicuously during half-time ceremonies at football and basketball games when

a student, dressed up in buckskins and feathers, did a faux Native American

dance to the applause of Illini fans. I’m not a particular fan of the Chief,

and I think the dance he does is silly. No wonder, I decided, that Native

Americans on campus took offense at it and, for a dozen or more years, lobbied

and protested to get the Chief and his goofy jig banned forever. They finally

succeeded: they got the NCAA in on the act, and NCAA issued a proclamation that

the U. of I. would no longer be permitted to host post-season athletic contests

until it got rid of the Chief. That predicated a loss of revenue, always vital.

So the University banned the Chief. The process was a good deal more convoluted

than that, but the gist given here will serve as background to the editorial

that John Foreman, publisher of the News-Gazette, the civilian paper

hereabouts, wrote.

Although not any great fan of the

Chief, Foreman was “saddened,” he said, “over the way the decision to ban the

Chief was reached—saddened because so many people who care deeply about it, in

the end, simply had no say in the matter.” Acknowledging that some people were

offended by the vision of Native American culture that the Chief represented,

Foreman opted for greater tolerance. “I’m offended by some of what I see on

television, for example, and by a lot of rap music. But I don’t think the fact

that I find it offensive—even that many find it offensive—really justifies trying

to make it go away when others approve of it. I can change the channel. ‘Live

and let live,’ they used to say. You don’t hear that expression much anymore.

More and more, people think they need to decide what’s best for everyone.” He

estimated that maybe 10 or 15 percent of the university population thought the

Chief offensive. They could have avoided seeing the dance; they could have

turned away or taken the opportunity to visit the restroom. But they didn’t.

And “they didn’t want anyone else to see it either. They didn’t want to live

and let live. ... In the end, a handful of people got rid of Chief Illiniwek.

... The Chief’s demise is directly attributable to a few social activists on

the NCAA committees and a small core of UI leaders” who were embarrassed by the

continuing Chief controversy. “Despite the views of many American Indian

activists, even the majority of American Indians never crystallized behind the

notion that there was something wrong with the Indian symbolism for sports

teams. The only attempt ever made to scientifically gauge their opinion on the

matter resulted in resounding approval for the use of such imagery. The best

argument that could ever be mustered against Chief Illiniwek was that ‘some

people’ were offended by it. ... That doesn’t seem like a very good way to

decide anything—let alone something that mattered to so many people. ... Yet

more and more decisions happen just like that. If one person is offended by the

presence of a Christmas tree in the dormitory cafeteria, we get rid of it. If

two or three people are offended by the selections performed at a school

holiday program, we change them. For the most part, the rest of us go along

with that. Most of us don’t want to offend others—even if it’s just a few

others, even if we really wish they’d just live and let live.” In the case of

the Chief, the few who were offended finally found a way to get rid of the

offensive figure: they found someone who could essentially just decree an end

to Chief Illiniwek without taking a vote or anything like it. “It doesn’t seem

fair,” Foreman concludes. “It doesn’t seem right. It’s sad, really. And if it’s

the way decisions are going to be made about other issues people care about, it

becomes terribly important in the whole scheme of things—and that has nothing

to do, really, with Chief Illiniwek.”

Puts me in mind of the way it was

decided to invade Iraq.

A few protest letters may re-instate

a favorite comic strip; and for that, all of us here at Rancid Raves are happy.

But our happiness is short-lived when we realize that, by the same token, a few

well-situated voices can decide to send thousands of Americans off to die in

distant deserts. Particularly, as Bill

Moyers recently demonstrated on a PBS special, “Buying the War,” when

dissenting voices fall silent. “Four years ago this spring, the Bush

administration took leave of reality and plunged our country into a war so

poorly planned it soon turned into a disaster. The story of how high officials

misled the country has been told. But they couldn’t have done it on their own;

they needed a compliant press, to pass on their propaganda as news and cheer

them on. ... As the war rages into its fifth year, we look back at those months

leading up to the invasion, when our press largely surrendered its independence

and skepticism to join with our government in marching to war.” It was a

horrifying 90 minutes of television—made all the more heart-breaking at the

revelation that various news media, the Knight Ridder people chief among them,

knew the Bush League claims were fraudulent but couldn’t get any of the big,

harbinger papers like the New York Times or

the Washington Post to publish their

stories.

So how are we deciding things these

days?

Onward, the Spreading Punditry

Okay,

the war on terror is over. We won. Last month, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, famed

9/11 mastermind who’s been in U.S. custody for years, confessed to beheading

journalist Daniel Pearl and to playing a central role in every single action of

the Terrorist Hordes. And we’ve got him. So it’s over, right?

Despite this obvious fact, GeeDubya

has launched a surge to finish off Iraq. That’s Plan A. Plan B, we learn, is to

insist that Plan A work.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis

Miller adv.

Arthur

Frommer is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the publication of

the first of his empire of travel books, Europe

on 5 Dollars a Day. Wandering the Left Bank in 1957 Paris, young Frommer

chanced upon a family-run hotel, the Claude Bernard. “He found budget bliss in

a room overlooking the rooftops of Paris for $2 (about $14.50 in today’s

dollars, adjusted for inflation),” wrote Kitty Bean Yancey in USA Today. That chance encounter

prompted Frommer to get into the travel guide game. Today at the Claude

Bernard, rooms start at $130.

MORE

SPIKING OF CARTOONS

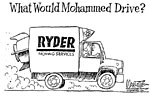

Scarcely had we posted our review last time (Opus

204) of David Wallis’ Killed Cartoons volume than the ’Net was buzzing with a fresh variety of scandal: it seems that

Wallis’ publisher, Norton, was so queasy about one of the cartoons he’d picked

for the book that it wouldn’t publish it. Yup: they killed a Doug Marlette cartoon slated for the Killed Cartoons tome. And here is the

offending cartoon, which first appeared in late 2002. The

cartoon in question debuted on the Tallahasee

Democrat website in the last week of December. Marlette sent it in from his

home in Hillsborough, North Carolina, electronically, and it was posted to the

website automatically. It prompted complaint from Muslim groups almost at once,

and it was quickly yanked. Muslims found the cartoon offensive because the name

“Mohammed” invokes the religion’s prophet founder and therefore seems to imply

that Islam is a bomb-throwing religion, thereby nurturing post-9/11 bigotry

about all Arabs as well as Islam. Marlette and his newspaper were flooded with

e-mails (approaching 6,000 within a week or so of the cartoon’s appearance).

Parker got wind of the excitement and wrote about it. Both she and Marlette in

a written statement that was distributed nationally pointed out that the

cartoon plays off the “What Would Jesus Drive” campaign against gas-guzzling

SUVs. Ibrahim Hooper, spokesman for the Council on American-Islamic Relations

in Washington, D.C., noted the connection: “Jesus represents Christianity, and

Mohammed represents Islam,” he said. “It’s a direct parallel.” Marlette

protested, saying that the cartoon was not an assault on Islam or its founder

but on “the distortion of Muslims’ religion by murderous fanatics and zealots.”

Parker concurred, saying that “anyone half awake understands” that the cartoon

attacks “fundamentalist Islamists [who] have hijacked [Muslims’] religion to

justify murdering Americans.”

And

that’s true: in the “What Would Jesus Drive?” campaign, the message is against

SUVs; the parallel in Marlette’s cartoon, then, is its message against Ryder

trucks (an allusion to the Oklahoma City atrocity) being used to haul bombs to

unspecified destinations. But the nuances of the parallel are not immediately

apparent, I’m afraid, and as a result, it’s easy to misinterpret as Hooper and thousands

of others did.

Marlette

was not the only political cartoonist at the time to raise the ire of readers

with imagery that verges on ethnic stereotyping. At the Palm Beach Post, Ombudsman C.B. Hanif devoted an entire column to

the inflammatory nature of cartons that touch on religion. He starts with a cartoon by Walt Handelsman of Newsday that showed several people admiring a proposed design for

New York's World Trade Center. A bearded figure, probably representing Osama

bin Laden, says that the proposed building—very tall, like the World Trade

Center—was "perfect," apparently for destruction. Said Hanif: “The

drawing too closely resembled many fellow law-abiding Muslims. Though that

struck me as the worst kind of stereotyping, it won't be the last time a

cartoon bothers someone due to the message he or she perceives.”

He

goes on to discuss a recent series in Wiley

Miller’s Sunday Non Sequitur in

which Wiley’s angelic doughboy is sent into the Middle Ages where he is bullied

and punished by the officials of a local religion. A letter-writer, Anthony

Orrico, was outraged by what he saw as an anti-Catholic sentiment, saying,

among other things: “You have abused the First Amendment privilege of free

speech. Who will you persecute next? Protestants? Jews? Muslims?"

Wiley

responded: “Actually, Mr. Orrico defends the material himself when he said: 'I

acknowledge that some past and present Catholic prelates have abused their

power, as have some of those of other religions when they possessed similar

power.’ Well, that's all the story line is about--the abuse and corruption of

power. And that is why I use the generic term, 'the church,’ throughout the

story, as the shoe of corruption is sadly one that fits all faiths at any given

time in history. This story is not intended as a shot at the Catholic Church,

and to say this material is 'vehement anti-Catholic' is quite a stretch to say

the least.

"Let's

put it this way,” Wiley continued, “if this was intended to be anti-Catholic

material, it would have never seen publication. First of all, I am Catholic.

Secondly, my syndicate would never allow material to be distributed that

defamed any faith. And last, no newspaper would run it. I understand the

sensitivity Mr. Orrico has regarding anything that even remotely smacks of

criticism toward the Catholic Church, as the church has taken quite a beating

in the press over the past year. But that beating is not only well-deserved, it

is self-inflicted. ... Catholics should be directing their rage at the source

of those problems ... the hierarchy. Censorship is not the answer to the

problems of the Catholic Church. Indeed, that is the very reason the problems

got to be so big. If people see their faith reflected in this material, then

they shouldn't blame the mirror."

Marlette

also used the criticism of his cartoon to make a larger point: “What I have

learned [from a 30-year career as a cartoonist] is that ... no one is less

tolerant than those demanding tolerance. ... Despite differences of culture and

creed, they all seem to share the egocentric notion that there is only one way

of looking at things, their way, and others have no right to see things

differently. ... Here is my answer to them: In this country, we do not

apologize for our opinions. Free speech is the linchpin of our republic. ...

Granted, there is nothing ‘fair’ about cartoons. You cannot say ‘on the other

hand’ in them. They are harder to defend with logic. But this is why we have a

First Amendment—so that we don’t feel the necessity to apologize for our ideas.”

All

of which is true. But it is also true that cartoons that tread into religious

or ethnic territory are almost certain to raise the hackles of those who see

their territory threatened. Cartoonists have almost never been safe on this

score, whether on the editorial pages of the nation’s newspapers or in the

comics section, and, increasingly, controversy often starts in the latter. At

the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco, a special 2003 exhibition explored

“Hate Mail: Comic Strip Controversies.” Displaying strips from Aaron McGruder’s The Boondocks, Garry

Trudean’s Doonesbury, Berk Breathed’s Bloom County and Outland, Lynn Johnston’s For Better or For Worse, Scott

Adams’ Dilbert, and Wiley’s Non Sequitur, the show, it seemed to me at the time—and now—strenuously

attests to the courage of newspaper editors and syndicate officials and to the

maturation of the American newspaper reading public, which has grown more

tolerant of expressions of opinion in its entertainments. Newspaper comics were

criticized at birth—the Yellow Kid, the Katzenjammers—for being vulgar and,

hence, a bad influence on the young. None of the contemporary strips in the

Museum’s show would have been published in newspapers a century ago—perhaps not

even a quarter-of-a-century ago. Today, most of the strips on display are not

only tolerated but enthusiastically supported by large segments of the

newspaper readership. Cartoons that edge up to ethnic issues will inevitably

draw fire, but we’re still more tolerant today than we once were.

Still,

we have timorous editors and publishers—like Norton, which managed, with its

very timidity, to perpetrate a colossal irony that proves the point of Willis’

book. Delicious. Exquisite. Marlette, writing in Cagle’s Best Political Cartoons of the Year, 2007 Edition to comment on the

Danish fiasco by reference to his “What Would Muhammad Drive?” cartoon,

extended his argument: “I was used to negative reactions from religious

interest groups, but not the kind of sustained violent intensity of the Islamic

threats. The nihilism and culture of death of a religion that sanctions suicide

bombers and issues fatwas on people who draw funn7pictures is certainly of a

different order and fanatical magnitude than the protests of our home-grown

religious true believers. As a child of the segregated South, I am quite

familiar with the damage done to the ‘good religious people’ of my region when

the Ku Klux Klan acted in our name. The Council on American-Islamic Relations

(CAIR) that led the assault on me describes itself as a civil rights advocacy

group. Among those whose ‘civil rights’ they advocated were the convicted

bombers of the World Trade Center in 1993. They cannot be taken seriously. For

many of those who protested my cartoon, recent emigres, many highly educated,

it was obvious that there was not that healthy tradition of free inquiry, humor

and irreverence in their background that we have in the West. There was no

Jefferson, Madison, Adams in their intellectual tradition. Those who have

attacked my work, whether on the right, the left, Republican or Democrat,

conservative or liberal, Protestant, Catholic, Jewish or Muslim, all seem to

experience comic or satirical irreverence as hostility and hate. When all it

is, really, is irreverence. Ink on paper is only a thought, an idea. Such

people fear ideas. Those who mistake themselves for the God they claim to

worship tend to mistake irreverence for blasphemy.”

The

issue, as you surely have observed, is not confined to Muslim extremists. Tony Auth at the Philadelphia Inquirer reacted to the recent Supreme Court decision

upholding the federal partial-birth abortion ban by depicting the five Catholic

justices wearing bishop miters.

PENIS

MIGHTIER THAN SWORD

A typo any of us typists would be happy to have

committed, but I’m repeating it here as deliberately as it was doubtless

constructed in the first instance as a lead-in to:

The

pen may be mitier than the sword, but it takes only the tiny pen point of a

diligent editoonist to pop the bubble of pomposity. To attack oppression, on

the other hand, persistence is needed. —RCH

CIVILIZATION’S

LAST OUTPOST

One of a

kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv.

The case of Seung-Hui Cho and the 32 murders he

committed at Virginia Tech presents vividly the hopelessness of the gun dilemma

in the U.S. None of the various impediments designed to prevent the sale of

firearms to unbalanced persons prevented Cho from buying a gun. All failed

because of some administrative factor, a failing at once tragic but all too

human. Moreover, Cho’s teachers and others in university officialdom couldn’t

notify his parents of any of his evident maladjustments because state and

federal laws require that colleges treat students as independent adults not as

anyone’s children. And anti-discrimination statutes prohibit putting students

on involuntary medical leave even if they manifest serious mental illness.

Students have sued colleges for discriminating against them “because of suicide

attempts and psychotic episodes.” Said Rich Lowry in National Review Online:

“Instead of requiring sad, sick people to get treatment, we let them wander

freely in the name of civil rights.” I’m not suggesting that we repeal all such

laws; I’m saying, only, that their good intentions enable disturbed people like

Cho more latitude than might be good for them. Or us. That, however, is a risk

we must run if we wish to be free in a humane society.

The

statistics against which these feeble protections are erected are nearly

overwhelming. According to The Week magazine,

“about 1,000 crimes involving firearms are committed every day, and some 29,000

Americans are killed by firearms every year. Of those victims, about 11,000 are

murdered, 17,000 use a gun to commit suicide, and nearly 1,000 die in

accidents. By comparison, the annual toll of gun deaths in Britain is about

100.” Just 100! “And in Canada, 168. Every day in the U.S., eight

children alone die from a gun wound. ... we lose the equivalent of the massacre

at Virginia Tech every four days.”

Meanwhile,

the National Rifle Association has run athwart the American Jewish Congress

with its America’s First Freedom magazine,

the current issue of which has a cover drawing that depicts New York’s Jewish

mayor Michael Bloomberg as an evil-looking octopus stretching its anti-gun

tentacles all across America, a country that loves its first freedom. David Twersky

of the AJC said the magazine’s editors should have known that the octopus has a

history as an anti-Semitic symbol. NRA’s spokesman Ashley Varner pleads

complete ignorance. But Twersky is scarcely placated. “For them not to know

this is really, really stupid,” he told Sara Kugler of the Associated Press.

Gee, I didn’t know that either, so I must be really, really stupid. But the

Anti-Defamation League, while allowing that some might take offense at the

drawing, didn’t think the cartoon is inherently anti-Semitic. What’s more, when

octopus is deployed in an anti-Semitic effort, it is usually accompanied by

some very specific symbol that underscores its intention. The NRA drawing has

no such symbol.

Read and

Relish

You know the speed of light. What’s the speed of

dark?

Death is hereditary.

Anything worth taking seriously is worth making fun

of.

All true wisdom is found on t-shirts.

An Acquired Taste: Be Among Them

Onward, the

Spreading Punditry

What if the Bush League had been right about Iraq?

What if the neoconservatives had been purely prescient about the outcome of

this Mideast adventure? Our invading horde would have been greeted with showers

of flowers as it tramped through the streets of Baghdad; experienced

bureaucrats would come out of hiding to assume government positions; and civic

life would, overnight, be re-arranged and efficiently run. In one swell foop,

we would have established convincingly the prowess of the American military

machine and the potency of the foreign policy it served. Iraq would be the

object lesson: Iran and North Korea, already designated targets by GeeDubya as

members of the Evil Axis, would then have quaked in their boots and given up

nuclear ambitions in fear of being invaded just as the first member of the evil

trio was. And the world would be a better place today. And when, exactly, did

any dream of this dimension ever achieve actuality? Dreamers serve a purpose in

human affairs, but they probably ought not to be policy-makers and

commanders-in-chief of vast military machinery.

EDITOONERY:

THE AWARDS SEASON

Pulitzer Prize for Political Cartooning

The Pulitzer for last year’s editorial cartoons,

announced April 17, is both a second and a first. This is the second time Walt Handelsman of Newsday has won the $10,000 prize (he also won in 1997), and it’s

the first time the prestigious award has honored work that included animation.

About a year ago, Handelsman started creating animated political cartoons for

the paper’s website in addition to drawing the usual static version for the

editorial page of the print edition. His portfolio of submissions to the

competition included 10 still cartoons and 10 animations. Said Newsday’s editor, John Mancini: “It’s

terrific that the Pulitzers recognized not only Walt’s keen powers of

observation, biting sense of humor and political insight, but also how’s he’s

leading the way to show what editorial cartooning can be in the electronic

age.” The other two finalists for the Pulitzer—Nick Anderson of the Houston

Chronicle and Mike Thompson of

the Detroit Free Press—both do

animation as well as traditional print. Should political cartoon animation be a

separate Pulitzer category? “I don’t know,” Handelsman told Dave Astor of Editor & Publisher—“it’s so new.”

Handelsman

taught himself animation techniques by working at home evenings after putting

in a full day at the office, relying on his family’s understanding. He thanked

his wife, reported Newsday’s Keiko

Morris, joking that waking her in the wee hours “to see what I did to Dick

Cheney” was a common scenario. He also thanked his sons James, 15, for “his

brutally honest criticisms,” and Billy, 12, “for sound effects.” “I told them

that sacrifice is a life lesson,” the cartoonist said. “It’s important to

realize that if you work hard, occasionally great things can happen.”

Handelsman

has a history of working harder than necessary. After two years at the

University of Cincinnati, he returned in 1979 to his hometown, Baltimore, where

he worked in commercial art, doing layouts and production work at Quality

Composition, a local agency; there, he met and married the boss’s daughter. But

he wanted to get into political cartooning, so he did cartoons for a weekly for

three years without compensation, after which he landed at Patuxent Publications,

a chain of 7 weeklies. He spent the next three years there, winning 11 awards

from the Maryland-Delaware-D.C. Press Association and self-syndicating his

cartoons around the country to daily newspapers. It paid off: in May 1985, he

was hired full-time at the Scranton

Times, a daily gig. Four years later, he left for the Times-Picayune in New Orleans, and from there, he went to Newsday in 2001.

As

the political cartooning profession shrinks, many political cartoonists have

started animating their commentary at newspaper websites, expecting—or

hoping—that a presence on the Web will extend their professional lives.

Editoonist Daryl Cagle in his blog

at www.cagle.msnbc.com is pretty sure they’re “wandering

blindly.” Acknowledge the seemingly bleak future for newspapers as a print

medium, Cagle questions the adaptation tactic many newspapers have

adopted—turning to the Internet. “It makes perfect sense to chase the shifting

audience,” Cagle writes, “but the move to the Internet doesn’t make much

business sense.” There’s no money there, he says. And he should know: Cagle

operates the Web’s biggest venue of political cartoons, but it is successful

because it “is associated with MSNBC.com, which gets its traffic from MSN.com,

which gets most of its traffic from the famous MSN.com home page, the default

home page for PC buyers using the Internet Explorer browser, who don’t bother

to change their home page. ... The trick to finding a big audience on the Web

is to bring your site to the audience [as MSN.com has done], not to expect the

audience to find your site.” For many newspaper editors, he continues,

“Internet strategy is a fantasy from the movie ‘Field of Dreams’: ‘If you build

it, they will come.’” But they don’t. And websites don’t, as a rule, pay for

content: they pick it up, gratis, from other media. They steal it. (Or poach

it. Pick your verb.) And so animating political cartoons on the Web doesn’t

seem promising as a way for editoonists to stave off extinction. “The problem

for cartoonists is much the same as the problem for other content creators;

there is no market for animated political cartoons when websites don’t want to

pay for content.” Despite the popularity of his site, Cagle says he still makes

his living selling cartoons “that are printed in ink on paper to traditional

clients who actually pay. ... Even the successful JibJab guys use their

political cartoons for publicity and make their living doing animations for

commercial clients. The editorial cartoonists seem to be charging ahead in

their aimless endeavors, typically creating animated political cartoons on the

side, for newspaper employers who pay them nothing extra for the extra hours,

creating content that no one wants to buy in syndication.”

Animating

political cartoons may be the distant future for editoonists, but in the

meantime, Scott Stantis, editoonist

at the Birmingham News (Ala.),

doesn’t think the Pulitzer for political cartoons should go to the animated

variety. He admires Handelsman’s work and thinks of himself as a friend, but he

doesn’t think an animated political cartoon is the same thing as a static

political cartoon. “Let’s put it this way,” Stantis wrote in his newspaper,

“giving the Pulitzer Prize for an animated cartoon is like awarding it for best

novel to ‘Doctor Zhivago’ starring Omar Sharif. It’s just not the same thing.”

He went on: “What’s next? ‘The Family Guy’ gets a Pulitzer? ‘The Simpsons’?

‘American Dad’? The JibJab guys? They’re animated, have political content, and

are posted online. According to the new rules, they’re all eligible. So don’t

be surprised some day if you see Scooby-Doo accepting the highest honor in

journalism.” The biographical note that accompanied this screed concluded: “By

writing this column, Stantis understands he is obliterating whatever minuscule

chance he ever had at winning a Pulitzer Prize.” I think Stantis has a point,

but not exactly the one he tries to make by keying off the Pulitzer committee’

appreciation of the “zaniness” of Handelsman’s animated cartoons. Stantis wrote:

“What makes an editorial cartoon great, what makes it the thing readers turn to

first on the editorial page, is the unique ability of a well-conceived and

well-executed cartoon to cut through the spin. To slash through the deliberate

fog that politicians create and get to the hard and often uncomfortable nub of

an issue. They may take a comic turn but in their black hearts they are not

‘zany.’ They’re savage. ‘Zany’ is not what an editorial cartoonist aspires to

yet many in the publishing business increasingly expect it.” Here, Stantis is

ranting against the Jay Leno comedy to which editoonists often sink; his

objection is to recognition of “zaniness” as a legitimate tactic for a

political cartoonist. But the distinction he draws between, say, “Family Guy”

and an editorial cartoon in print form is a more valid reason to object to the

Pulitzer committee’s singling out Handelsman’s animation for a Prize. Static

editoons work most powerfully when their messages are carried by visual

metaphors, images that sear the brain and linger there. And animated editorial

cartoons have not yet reached the metaphorical stage—hence, they are, as

Stantis strenuously implies, a different artform, and they require a different

category for recognition by the Pulitzer people.

Other Awards. The Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for political cartooning went to Clay Bennett of the Christian Science Monitor. Signe Wilkinson at the Philadelphia Daily News won the Thomas

Nast Award for international cartooning from the Overseas Press Club. And the Denver Post’s Mike Keefe earned the top honors in the annual John Fischetti

Editorial Cartoon Competition established by the Journalism Department of the

Columbia College in Chicago. Chip Bok of the Akron Beacon Journal won the

editorial cartoonist of the year “opinion award” from The Week magazine, a weekly publication that routinely, diligently,

scours dozens of news periodicals every week to digest their gist in its pages.

It also publishes a selection of political cartoons every week, sometimes two

pages of them. Jack Higgins of the Chicago Sun-Times was honored by the

Chicago Bar Association on May 3 for a series of cartoons he did on political

corruption. Mike Lester at the Rome News-Tribune (Georgia) received the

Sigma Delta Chi Award for Excellence in Editorial Cartooning. Lester said

getting this recognition from the Professional Journalists Society was the high

point in his career, “outside of most improved conduct in the sixth grade.”

Later, he confided in Daryl Cagle,

whose syndicate distributes Lester’s cartoons: “I’m flattered and have a

feeling of validation to have won, but my suspicion is that the awards

committee probably just misspelled ‘Luckovich’” (a reference to the editoonist

at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution who

won both the NCS Reuben and the Pulitzer last year, and the Headliner Award,

last year and this). At State University of New York in Brockport, student

editooner Kory Merritt won this

year’s John Locher Memorial Award for college editorial cartooning. The award

memorializes the son of cartoonist Dick

Locher, who produces political cartoons and Dick Tracy for the Tribune Media Services. Ann Telnaes won the first prize in the 15th Dutch

Cartoon Festival 2007, the theme of which was “Man and Religion in Cartoons.”

Telnaes, whose female perspective often yields piercing insight into current

events, sometimes depicts religion as the oppressor of women’s rights,

particularly the Catholic Church and its attitude towards abortion and its

opposition to women in thepriesthood. Her winning cartoon showed a woman

surrounded by four men of various religions, symbolically boxing her in,

imprisoning her, by drawing restrictive red lines around her. Telnaes’ most

recent book is Dick, a collection of

cartoons about Cheney, the President of the Vice of Power, each one a caustic

vision of arrogance gone sinister.

MORE PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS

Once corporations assume control, you have “corporate

culture”—which is no culture at all in the traditional sense. Culture becomes

“product.” —RCH

“A

fellow who is always declaring he’s no fool usually has his

suspicions.”—Playwright Wilson Mizner

“If

it’s not one thing, it’s another.” —Robin Williams

ACOCELLA

REVISITED

Cartooning Affirms Life in the Face of Death Threat

We reviewed

this book in Opus 197, but briefly. Here’s the same review again, this time,

with remarks by its author, and a quick look sideways at her previous graphic

novel.

The back cover of the little pink book with the

purple dust jacket asks a question: “What happens when a shoe-crazy,

lipstick-obsessed, wine-swilling, pasta-slurping, fashion-fanatic,

single-forever, about-to-get-married big-city girl cartoonist (me, Marisa

Acocella) with a fabulous life finds ... A LUMP IN HER BREAST?”

One

of the things that happened in this case is a colorful graphic memoir entitled Cancer Vixen (212 8x8-inch pages,

hardback; $22). Another thing that happened in this case is exuberant

cartooning the way exuberant cartooning should be.

Suffused

with wit both visual and verbal, the book is a roller coaster read of emotional

highs and lows, joy and anger illuminated on every page by Acocella’s simplest

line art. (She has other styles.) She uses visual symbols like an editorial

cartoonist—also diagrams and charts—to take us, step by step, day by day,

through the ordeal of initial suspicion about the lump, then examination,

diagnosis, and treatment by lumpectomy and chemotherapy. The book is

informative in copious detail, explaining every aspect of her disease and its

treatment—with cartooned visual aids. Acocella satisfies her curiosity, and

ours, about breast

cancer, but in addition to being curious, she’s a

cartoonist and thinks like one—in visual-verbal terms—as is evident on every

page.

“I

think visually,” she said, “so it was easier for me to put it down in images

rather than in just pure words.”

She

deploys narrative breakdown and page layout as deftly as she wields her pen,

adroitly blending word and picture for comedic purposes as well as educational

ones. “Finding Humor in a Tumor” was the headline over a review in the New York Post, and that’s as accurate a

headline as we could ask for.

Doing

the book was therapeutic, Acocella said when interviewed by Don Aucoin at the Boston Globe. “By focusing on the work,

it took the focus off cancer—even though I was writing about it. Instead of

focusing on a lumpectomy, I would focus on a deadline or writing. I always

found that for me, a little bit of denial is not a bad thing.”

She

was inspired by Art Spiegelman’s Maus and other graphic novels. She had produced a graphic novel of her own in 1994.

Entitled Just Who the Hell Is She,

Anyway? it was based upon a comic strip, She, that Acocella did for Mirabella magazine. “It got good

reviews,” Acocella said, “but went pretty much unnoticed because the

concept of graphic novels was relatively new then.”

Acocella’s

cartoons appear regularly in The New

Yorker and in Glamour magazine,

and for a time, she did a bi-weekly comic strip in The New York Times, the first—and, to date, the only—comic strip

ever in the Gray Lady of American newspapers. That arrangement dissolved a year

or so ago.

Doing

a book about her cancer was exactly the sort of cartooning Acocella has always

done. “I had always worked pretty much as a hybrid journalist cartoonist, and

everything has always been autobiographical for me, so it was a natural fit.

The best cartoons are things that are really truthful. I have always documented

everything.”

According

to reporter Allison Xantha Miller, Acocella “goes shopping to figure out what

her characters will wear, which once resulted in her being thrown out of a

Gucci store for taking pictures of the clothes.”

Cancer Vixen brims with personal drama

as well as hilarity. We get generous glimpses of her professional life as a

freelance cartoonist and of her love life. She is on the cusp of marrying for

the first time at the age of 43 to celebrity restaurateur Silvano Marchetto.

Will her fiancé desert her now that she’s “damaged goods”?

The

book is a love story as much as a gleeful expose of a terrifying subject. “I

didn’t realize what I had,” Acocella told Julian Kesner at the New York Daily News. “I didn’t know how

much he loved me. He could have had any girl with the best legs or the best

breasts, but he married someone who had breast cancer. That’s pretty special.”

Her

byline on the book acknowledges how special: Marisa Acocella Marchetto, “right

now, cancer-free,” she says, “—thankfully.”

Cancer Vixen is great, accomplished, effective cartooning. And it is also a comedic but life-affirming love story.

Onward, the

Spreading Punditry

Perhaps a word of two of explanation is needed about

the political vacillation of This Colyum. In my wilder moments of egomaniacal

self-adulation, I imagine hordes of readers of This Space wondering why I

haven’t gone after GeeDubya much lately. The answer is quite simple: he doesn’t

need me to point out that he is a fraud and a liar when every time he opens his

mouth lately, he proves it himself. Naturally, I feel like the third wheel on a

prom date. So I have maintained a discreet silence. His only demonstrated

competence lately is as cheerleader, the role he first assumed while in college

and has ever since fulfilled admirably. At a recent rally

(we don’t, here at Rancid Raves, call them

“addresses” or “speeches”), he ranted on about Iraq until he reached the

cheerleading crescendo: “We will win the war in Iraq!” he exclaimed, raising