|

||||||

|

Opus 195:

Opus 195 November 14, 2006). We are happy (not to mention

exhausted) to report that the third year of subscription Rancid Raves produced

even more monthly content than the second year, which was better than the first

year. We also review the Library of Congress’ Cartoon America and the graphic novel, Pride of Baghdad. And we present some unique visual tributes to

Jack Davis and Sergio Aragones, sample Doonesbury’s latest invention, The Sandbox, examine plagiarism in editorial cartooning,

preview a new comic strip, and eat crow for predicting the wrong result of the

recent election. Here’s what’s here, in order by department:

Annual

Report

NOUS R US

More

Danish Dozen Doin’s

Harassment

of Cartoonists in Foreign Lands

Lost

Girls Clears Canadian Border

The

Year’s Best Graphic Novels

HONORIFIX

Unique

Visual Tributes to Jack Davis and Sergio Aragones

Playing in Doonesbury’s Sandbox

EDITOONERY

Matt

Wuerker, Paul Conrad

Jim

Borgman’s Day After Dilemma

Plagiarism Again

A

Good Weekly Editoon Roundup

BOOK MARQUEE

New

Books by Editoonists Jeff Danziger and Mike Luckovich

Rants

& Raves Gallery: Neat Pix

A NEWCOMER ON THE COMICS PAGE

New

Strip from King Features

BOOK REVIEW: Cartoon America

Graficity: Pride of Baghdad

Onward,

the Spreading Punditry

How

to Vote Next Time

Coming

Soon: The Big Bug-out

And

our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by

clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just

this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned.

Without further adieu—

Annual

Stock-taking and Bean Counting

Once

again this year, as last year, we stumbled in September and tried, in October,

to make up for it by flooding you with a double-allowance of the usual

persiflage and bagatelles. Our contract, as you doubtless recollect, calls for

approximately bi-weekly visits, and we missed a week in the ninth month with Rants & Raves. In the tenth month,

however, we posted three Rants &

Raves and two Hindsights. So we

hope you think you’ve been adequately compensated for the September deficiency.

We also missed a week in March: I was, my personal self, out of commission for

a couple weeks that month getting my colon removed, all 7.8 miles of it,

everything from Las Vegas, New Mexico, to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

It was diverticular bleeding, not, thankfully, cancer. We don’t need the colon,

I’m told. Another of those superfluous organs, like the second kidney and the

appendix and, in red states—until just last week—the brain. In any case, I was

able to resume my typing tasks in time to pound out two installments in April

and thereafter. If you count Hindsight articles

as one of the two visits a month, we missed none all year: even in the two

months (September and March) with only one Rancid

Raves, there was a Hindsight posting, so there were, as per contract, two postings per month.

The year as a whole was more prolix

than last year. From November 2005 through October 2006, we posted 23

installments of Rants & Raves (same

as last year) and, in the gratuitous bonus division, 13 Hindsight articles (11 last year). That’s a total of 36 visitations

for the year. We promised to post something nearly every other week and if

there are 52 weeks in the year, that’s 26 times; so we’re doing better than we

promised we would. Monthly page averages are similarly outstanding (even if we

say so ourselves): Rants & Raves averaged

51 pages a month; last year, 40. What other magazine on comics gives you 51

pages a month for only $1.32! Hindsights averaged another 8 pages per month, or 59 pages per month, total. To be

compulsively persnickerty, we should probably discount the pages devoted to

frothing-at-the-mouth political commentary since it’s only sometimes, thanks to

the Danes, comics-related. Say 8-9 pages of such superfluity a month, probably

too high; but in a magazine that is sometimes about superheroes, superfluity

ain’t all bad, kimo sabe. So you’re still getting a magazine of comics news and

lore that runs 50 or so pages a month. And it is a magazine, not a blog.

Blogs, as I understand them, are like diaries or journals; a magazine, like Rants & Raves, offers discrete

articles on different subjects. And that’s what we do. We divide the articles

into departments (News [“Nous R Us”], Book Reviews, Comic Strip Watch,

Graficity [Graphic Novels], and Funnybook Fan Fare, all directly engaged in

comics, plus a few trimmings like favorite quotations and reports on the oddest

doings around, Civilization’s Last Outpost), but they’re still articles, not

journal musings.

Despite the flip tone herewith,

we’re not bragging: we’re merely hoping to demonstrate having provided the

value you bargained for when you subscribed. The quantity anyhow; about the

quality, you must be the judge. I keep saying “we” as if there were more than

one of us, and there is. This website is designed (handsomely, I think) and

operated (faithfully, without question) by my partner, Jeremy Lambros, who recently moved to Illinois (my balliwick) from

Los Angeles. Jeremy handles all the technical machinations—subscription

accounts, book purchasing, posting articles and installments and illustrations,

everything but the actual writing of the material and selection of illustrations.

Oh, and I mail the Harvey-authored books from here, Rancid Raves Central,

whenever he tells me we’ve sold something. The used book sales are handled

entirely by me, sales and shipping. Opus One of R&R is dated May 5, 1999; so we’ve been doing this, Jeremy and

I, for seven-and-a-half years, with amazing regularity. Well, I’m amazed

anyhow. In this throw-away culture of ours, very little lasts for

seven-and-a-half years. But we do. Proving that Rancid Raves are forever. And we’re glad you’re still with us. No

one has cancelled, by the way, that I know of; and the number of subscribers

has steadily increased. So you may console yourself that you are part of a

burgeoning enterprise. And herewith, we’re off and running for the 195th time.

NOUS R US

All the news that gives us fits.

The

Muslim world is not finished with the Danes yet. While we were all voting on

this side of the Atlantic, on the other side, in Kuwait City, lawmakers also

voted, 25-12, passing a non-binding resolution to sever diplomatic ties with Denmark. Some of the body wanted similar

action taken against the Vatican for the Pope’s having insulted the Prophet

Muhammad. One member of the National Assembly, speaking, doubtless, for others,

felt that Islamic governments had failed to address the issue forcefully enough

and urged that all Muslim countries join in boycotting Danish products. The

feeling among some was that if stern (financial) measures are not taken,

attacks on the Prophet will continue. “We are not true Muslims as we failed

miserably to defend our religion,” said one, quoted in the Arab Times online. It’s been over a year since the insulting

cartoons first appeared, but there have been other incidents in Denmark. And in

the minds of many, the blasphemy began long before the Danish Dozen surfaced:

the “war on Islam” began in 2001 with September 11 “when Islam was linked to

terrorism” by the American president. ... In the Arabian Sea’s atoll nation of

Maldives, political action took other forms. There, cartoonist Ahmed Abbas fled the local authorities,

seeking asylum at the United Nations offices. The UN, unable to grant political

asylum except when an individual’s life is immediately threatened, refused

refuge. According to the Minivan News report, Abbas’ life was not in danger: he

was simply seeking to avoid serving a six-month prison sentence as a result of

being convicted of “disobedience”—that is, for making comments in August 2005

that could be interpreted as encouraging people to assault the police. In a Minivan Daily article, Abbas suggested

that the way to treat the police “who beat us is to seek them out individually

and for us to act in such a manner that makes them feel that beatings result in

pain.” Abbas denied that he intended to incite physical attacks on police. Supporters

of Abbas claimed he was tried “in absentia,” a violation of the UN

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights “which the [Maldives]

government has recently signed. Their commitment to human rights on paper does

not translate to commitment to human rights in practice,” according to a

spokesman for the opposition political party. The government defended its

action by saying that Abbas was repeatedly summoned to trial but failed to show

up in court. The cartoonist, known for his sarcastic cartoons for Minivan and websites opposing the

government, said he never received a summons. Every side seems to have a valid

point-of-view, but the government’s crime remains unexcused and unexcusable:

exercising its inherently superior powers, it brought faux legal action against

a citizen for speaking out against an abuse of power. Abbas is now in Maafushi

prison; two of his editors at Minivan have been charged with “disobedience,” and journalists from the U.S. and

Britain were arrested and held for several hours and then put on flights out of

the country. The Malvides government was cracking down in anticipation of a

demonstration by the opposition party that took place on Friday, November 9.

In France, meanwhile, another

cartoonist is being harassed by authorities, this time for actual cartooning. Khalid Gueddar, who cartooned for the

Moroccan weekly Demain Magazine until

it was banned “and its editor, Lmrabet, was sentenced to three years in

prison,” left the country and now lives in France with his family, but he

continues to draw satirical cartoons for various newspapers and the website

Bakchich.info, according to a report at rsf.org. His present troubles

apparently stem from his cartoon accompanying an article by Lmrabet

“questioning the will of the Moroccan authorities to stamp out drug

trafficking.” After publication of the cartoon, gendarmes repeatedly visited

Gueddar’s family inquiring into the cartoonist’s activities. These visits, said

Reporters Without Borders, are “grotesque” and constitute “a form of harassment

and intimidation that we firmly condemn.” ... And in England in a trial in the

Old Bailey, a British Muslim denied the charges that he incited murder and used

racist language last February in Central London during a protest against the Danish Dozen. A microphone was thrust

into his hands during the rally of 300 protesters, he claimed, and he began

shouting the slogans on the placards in the crowd around him, some of which

called for beheading those who insulted Islam. “I was repeating what I heard in

other speeches,” said Mizanur Rahman, 23, “and I didn’t think about what I was

saying or the consequences. ... I feel almost ashamed,” he continued, “—I feel

the words didn’t make sense. I didn’t think anyone would take me seriously. I

didn’t intend for anyone to be harmed or attacked, let alone to be killed.” To

no avail: the Guardian reports that

the jury found him “guilty of using threatening, abusive or insulting words, or

behavior with intent to stir racial hatred.” The jury was deadlocked on the

second charge, inciting murder; the crown will seek a retrial.

On the Danish Dozen, Garry Trudeau, asked by the San Francisco Chronicle why U.S. news

media declined, almost universally, to publish the cartoons, said: “I assume

because they believe, correctly, it is unnecessarily inflammatory. It’s legal

to run them, but is it wise? The Danish editor who started all this actually

recruited cartoonists to draw offensive cartoons (some of those he invited

declined). And why did he do it? To demonstrate that in a Western liberal

society he could. Well, we already knew that. Some victory for freedom of

expression. An editor who deliberately sets out to provoke or hurt people

because he’s worried about ‘self-censorship’ is not an editor I’d care to work

for.” Asked if he would include any images of the Prophet Muhammad in Doonesbury, Trudeau said: “No. Nor will

I be using any imagery that mocks Jesus Christ.” Much as I admire Trudeau, I’m

not sure he has the Danish editor’s motive right. As I understand it, the

cartoon project was undertaken in order to test—or to demonstrate—the extent to

which the secular press is intimidated by Muslim attitudes. The effort did more

than that, as it turns out: it also dramatized the cultural gulf that exists

between the Muslim and Western societies. The immediate consequences approached

tragedy, but I suspect both societies are now more sensitive to their

differences and how to negotiate their way around them than they were before,

when each seemed to exist in profound ignorance of the other—and, sadly, proud

of it.

On about October 19, according to

the Christian Science Monitor, 38

Muslim scholars from 20 countries sent the Pope a letter urging mutual

tolerance and respect, and 500 prominent Muslims signed a religious ruling

rejecting violence against civilians. Neither action got much publicity, but

when Ayman al-Zawahiri, al Qaeda’s No. 2, issues a videotaped pronouncement, it

is picked up by every news medium, worldwide.

Lost

Girls, Top Shelf’s three-volume erotic graphic novel by Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie, has been selling faster than the publisher can

print it. The first run of 10,000 sold out upon release; the second 10,000,

released in October, also sold out. And about 17,000 of the third printing’s

20,000 press run are obligated to backorders. Porn sells, but we knew that, eh?

A fourth printing is already anticipated, especially since the book has been

approved for sale in Canada. ICv2

quotes a letter from Shawn Ewart, Senior Program Advisor of the Prohibited

Importations Unit, to Top Shelf attorney Darrel Pearson explaining the findings

in two key areas, depictions of incest and bestiality, and of sex involving

persons under 18. With regard to the depictions of incest and bestiality, Ewart

said, "...these depictions are integral to the development of an

intricate, imaginative and artfully rendered storyline....[T]he portrayal of

sex

is

necessary to a wider artistic and literary purpose." Similarly, with

regard to depictions of sex involving persons under 18, Ewart said,

"...these representations serve a legitimate purpose related to art and to

the very detailed story about the sexual awakening and development of the three

main female characters. Furthermore, it is my opinion that this item does not

pose an undue

risk

of harm to persons under the age of 18 years." No publisher could ask for

better publicity.

Citing increased paper costs, Gladstone has suspended four of its six

Disney titles, retaining only Uncle

Scrooge and Walt Disney’s Comics and

Stories, saith Steve Bennett at ICv2. ... Marvel Entertainment reported a year-over-year sales gain of 14%

for the third quarter even though net income dropped from $23.4 million to

$13.2 million, according to ICv2. Surprisingly, publishing revenues were

greater than licensing income, which was down “in large part because of a

decline in revenues from the Spider-Man property, which has become the major

engine driving Marvel’s licensing sales.” This is encouraging news: everyone

knew that 2006 would be “a tough one for the company” because there were no

movie releases this year and because the company had to take over its own toy

manufacturing. Among Marvel’s next challenges is proving that it can produce

in-house highly successful films based on its own properties, a test that will

commence with the 2008 release of the Iron Man movie.

PW Comics Week lists the year’s best graphic novels: Lost Girls, Fun Home, Scott Pilgrim and the

Infinite Sadness, Making Comics, Ghost of Hoppers, Curses, American Born

Chinese, Can’t Get No, The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation, and Dragon Head Vol. 1. At Amazon.com, the

year’s top ten are (in order from the top): American

Born Chinese, The Last Christmas, Fun Home, Abandon The Old in Tokyo, Billy

Hazelnuts, Lost Girls, War Fix, The 9/11 Report, Revelations, and Ohikkoshi. The criterion, I’d guess, is

sales rather than aesthetic quality. In the latter category, one of the number, American Born Chinese, an allegory on

Chinese-American identity, is up for the National Book Award in a few weeks.

The novelist, Gene Yang, professed

amazement: “It’s crazy,” he told Tim Leong at comicfoundry.com. And he doesn’t

expect to win. “I think it’s already so crazy that they nominated a graphic

novel,” Yang said. “If they actually gave it to a graphic novel—I don’t know—my

brain would melt. Honestly, I really do feel that by getting the nomination, I

won already. It was completely unexpected.”

The December issue of Playboy carries two new Dedini cartoons; I just knew the

magazine had an inventory of unpublished Dedini, and there are probably a few

more in the offing. The new cartoon editor, incidentally, is Jennifer Thiele,

succeeding the late Michelle Urry.

From Editor & Publisher. Ted Rall, hoping to eliminate all

typographical and grammatical errors for the second edition of his newest book, Silk Road to Ruin, is offering prizes

to those who find “new” (previously undetected) typos—“one sketch per typo,” he

said. Anyone who finds 15 such glitches will receive “the original artwork for

one of my recent syndicated cartoons.” In the book, which combines prose and

cartoon reportage, Rall tells of his travels through “the Stans,” oil rich

erstwhile Soviet states in Central Asia where brutal dictators clash with

Islamist guerillas, the elderly starve while oilmen deal, and looters careen

through the countryside looking to sell “disinterred nuclear missiles.” The

region is the “next thing” for American foreign policy, Rall believes, and yet

the government is virtually ignoring it. ... At Universal Press, Mark Tatulli’s May-launched pantomime

strip, Lio, has now signed up 150

subscribing papers, “the strongest comic release since The Boondocks in 1999.” The

Boondocks started with 160 subscribers and reached 200 within six months.

... Dave Kellett’s Sheldon strip has moved from United

Media’s Comic.com website to its own site, SheldonComics.com. Although I’ve

been reading the strip for a year or so at the United Media site, I never knew

that Sheldon is a software billionaire boy; I just thought he was a kid with a pet

duck and a nearly clueless grandfather. ... Two children’s books by syndicated

cartooners were among the “Teachers’ Picks: Best of 2006" in Parent & Child magazine: The Extraordinary Adventures of Ordinary

Basil by Non Sequitur’s Wiley Miller and Just Like Heaven by Mutts creator Patrick McDonnell. ...

George W. (“Whopper”) Bush was the easy winner in the 5th annual “Weasel Awards” competition at

Dilbert.com: GeeDubya got 15,447 votes with Donald Rumsfeld a distant second,

only 5,216 votes. The “Weaseliest Country” was the U.S. (9,121) with North

Korea a near second (9,110). ...

Fascinating

Footnote. Much of the news

retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and

related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve

deeply into cartooning topics.

HONORIFIX

Every

year when it seems autumn is about to flutter away into winter, the Comic Art

Professional Society (CAPS) has a banquet to honor a fellow ink-slinger.

Honorees recently have included Mell

Lazarus and Will Eisner, to name

a couple. CAPS, which hangs its headgear in Los Angeles, was started in 1977 by Sergio Aragones, Mark Evanier, and Don Rico, and last spring as the CAPS

Board began to contemplate the annual fall fandango, they probably thought it

was about time, after almost thirty years, to invent a trophy to give the

honoree. Naturally, they approached Sergio and asked him to design the

statuette. He did. It depicts in three comedic dimensions a small cartoonist

holding a giant pen and standing on one foot on a laptop computer, his other

foot stuck in an ink bottle. The computer recognizes that CAPS membership

includes writers as well as cartooners. The Board was delighted and turned

Sergio’s sketch over to Ruben Procopio, a sculptor who has devised many of Disney’s maquettes. Then the Board began

cudgeling its collective brain for a name for the award.

“All good awards have a name,” CAPS

prexy Chad Frye wrote, “—the Oscar,

the Emmy, the Reuben, the Golden Globe, the Eisner, Miss Congeniality—you name

it.” And so they struggled to do just that, name it. “We tossed around a few

ideas, but the more we thought about it, the more it was obvious. This new CAPS

award should be called ‘The Sergio.’” By one of those giddy happenstances,

everyone who learned about the name was delighted with it. Except Sergio, whose

feelings about it weren’t, at the time, known: he wasn’t told Meanwhile, the Board had decided to honor Mad cartoonist Jack Davis at the annual banquet. So on October 21, Davis was presented with the first Sergio for lifetime achievement. Then, before Sergio himself could react to this unanticipated christening of the product of his devising, he was called up to the podium and presented with the second Sergio. That was Sergio’s second surprise; then came the third surprise—that the little sculpted cartooner looks like its second recipient. The CAPS newsletter (a booklet, actually) was produced for the banquet in two editions, one for each honoree. Inside each are unique drawings contributed by admirers; here, for your delection, is a selection. Notice that

although the date of the dinner is the same on the covers of the booklets, the

times are different.

Persiflage

and Badinage

“In theory, theory and practice are

the same. In practice, they are not.” —Albert Einstein

“If everybody’s thinking the same

thing, then nobody’s thinking.” —George Patton

“Being a celebrity is probably the

closest to being a beautiful woman as you can get.” —Kevin Costner

“The statistics on sanity are that

one out of every four Americans is suffering from some form of mental illness.

Think of your three best friends. If they’re okay, then it’s you.” —Rita Mae

Brown

“Ninety-eight percent of the adults

in this country are decent, hard-working, honest Americans. It’s the other

lousy two percent that get all the publicity. But then, we elected them.” —Lili

Tomlin

NOW PLAYING IN THE SANDBOX

A New Department at Doonesbury.com

Michael

Yon in The Weekly Standard asked

recently: “How are our troops doing in Iraq?” His answer: “Who knows?” Part of

the problem, Yon believes, is that the news media are not covering the story adequately.

There are only nine reporters—“only two of them working for domestic U.S.

media”—embedded with the troops, “compared to 770 during the initial invasion.”

More significant, however, are the obstacles in the way of journalists seeking

to report events outside the protected Green Zone in Baghdad. Obviously, the

Pentagon doesn’t trust the press, especially in a war about which most news is

bad. But, said The Week, “refusing to

let reporters cover the actual fighting does a disservice to the troops.” Added

Yon: “The government has no right to withhold information or to deny access to

our combat forces just because that information might anger, frighten, or

disturb us.”

Garry

Trudeau’s latest venture won’t solve this problem, exactly, but it will

come closer than straight journalism has so far come. On October 8, Trudeau

launched The Sandbox, a military

blog, on his www.Doonesbury.com website. The announcement was

made in the Sunday installment of Doonesbury by the character Ray Hightower, a soldier: “Hey, folks,” Hightower begins;

“you may have heard how dangerous it’s become for the press to cover operations

OIF (Operation Iraqi Freedom) and OEF (Operation Enduring Freedom). Result: the

public feels increasingly disconnected from the troops in the field. Solution:

let the troops report on themselves.” And that’s what The Sandbox is for. It’s a “command-wide milblog from the Global

War on Terror, where anyone stationed in Iraq or Afghanistan could operate in

‘a clean, lightly edited debriefing environment where ALL content, no matter

how robust, is secured by the First Amendment. So if you support the troops—but

haven’t a clue what they’re actually up to—you owe it to yourself to log onto The Sandbox,’” Hightower finishes.

The focus is not on policy or

partisanship; the website has a comment section, Blowback, for that. Instead,

soldiers tell stories about some of the events of their daily lives, “the

unclassified details of deployment—the everyday, the extraordinary, the

wonderful, the messed-up, the absurd.” At first, Trudeau and his staff combed

the universe of milblogs and picked pieces to run in The Sandbox. “But now,” he

told Pam Platt at the Louisville Courier-Journal, “most of what we’re posting is original. ... Initially, we were mostly

worried about whether we’d get enough contributions to sustain the quality, but

those concerns proved unfounded. ... We can really handle only three or four

pieces a day. Obviously, we’re looking for variety—in authorship, tone and

subject matter—but we’re open to anything people want to submit. Other than

requesting a military address (we list the milblog URLs), we’re not in a

position to verify authenticity. But there’s little braggadocio in these

dispatches. They’re mostly thoughtful, heartfelt reactions.”

The

Sandbox, although read by soldiers in the field, is intended chiefly for

the homefront, Trudeau said. But it can’t be seen as a “bellwether for gauging

troop morale.” Said the cartoonist: “It’s much too anecdotal and random. The

writers represent only a handful of the 140,000 troops serving.” And the

bloggers are self-selected, which means they are the sort of people “who enjoy

writing,” Trudeau said, “and response to their work matters to them, so they

take some care.” The site is “very well edited by David Stanford,” Trudeau

added, “a former senior editor at Viking-Penguin, who has impeccable taste and

an invisible hand.”

Writing about Doonesbury generally—with particular reference, doubtless, to BD’s

loss of a leg in combat and his rehabilitation over the ensuing months—David

Hinckley at the New York Daily News observed

that “Trudeau has managed something many war supporters maintain is not

possible: taking the side of the troops who are fighting the war while

consistently lampooning those who got them into it.” And The Sandbox is another instance of Trudeau’s contention that

“whether you think we belong in Iraq or not, we can’t tune it out; we have to

remain mindful of the terrible losses that individual soldiers are suffering in

our name.”

The entries in The Sandbox are moving vignettes of soldiers’ lives, their thoughts

and feelings, and sometimes of the thoughts and feelings of their spouses left

at home. Here are excerpts from a couple. (For a better sample, go to http://gocomics.typepad.com/the_sandbox/ .) The first brims with poetic brio.

Isn't

it amazing the way time can play tricks on you? Have you ever sat in a

classroom, or a meeting, and felt that the clock was taunting you? Or been in a

situation where time sped past because you were enjoying the activity so much?

Rare is the man or woman who seems satisfied with the passage of time, as if

since we created our sundials and calendars we can control it.

How would it be if we didn’t have

clocks? How was it?

"I'll

meet you at Starbucks at high noon."

"When

the shadow is longer than the stick, I'll depart."

"I'm

being deployed to Iraq for twelve moons."

Time

can be seen as both a curse and a blessing, then. When you want something to

last forever, your mind perceives it as going by faster; a song you love, the

life of someone you care for or depend on, a good book, childhood, a cruise to

the Caribbean. And when you want something to end, oh man the time simply

drags; your morning commute in traffic, the mother of all meetings, a

deployment to Iraq, the time spent waiting for results of a medical test.

The

mechanisms inside the clock aren’t wrong. They’re pretty much constant. The

cycles of sun, moon, tide, and season are not false. They rule our lives.

Out

here in the desert, Time is King; the minutes are his minions, and the months

his sabers by which you are knighted. The King controls all that you do, when

you come and go, and how long until you see your children. Every mission and

order is based on a strict time schedule. We are deployed for a year,

"boots on the ground,” so 365 becomes a mystical combination of integers,

a mantra, a prayer.

We

are nothing more than Australopithecus in a uniform, or a burka, or an

expensive tailored suit. From the geographical perspective, humankind's time on

this earth is less than the blink of an eye. Plate tectonics dismiss us.

Volcanoes are too wise to notice our antics.

We

study anthropology even as we live within it. We fly and drive and move around

this planet, on these continents; we live and we fight. We are caricatures of

ourselves, cartoon nations embroiled in our global struggles. The mountains

fold their arms and they watch. We used to fight for food or a mate. Now we

fight for freedom or money.

When

you find yourself as a soldier in Iraq, holding some of the finest tools in

your hands, the modern equivalents to stone and flint, to a rock swung from a

stick to snare the hunted, you can’t help it, you count the days. It's a

reflexive reaction. Hit my knee with a rubber mallet.

You

track the hours, the seconds, and the months. X amount of Sundays left. X

amount of weeks. I will eat in this chow hall X many more times. This many

times I will lie in this bed and stare at the cracks in this ceiling. Like the

wallpaper in the home you grew up in, you don’t even notice it anymore. You

just cast your thoughts upon its patterns and let your mind roam free.

And

just because you're in the desert and the sights and sounds are so surreal, and

you’ve forgotten what America smells like at 9:00 in the morning as you walk

past your neighbor's garden or the bakery on the corner, you act as if the

possibility and difficulty of life is a finite thing, while your true path lays

spread before you like a virtual chess board. Pawn or King? Bishop or Rook?

Should I move forward slowly, or attack my fate with a flank?

"To live is so startling it leaves little time

for anything else." —Emily Dickinson

RCH: And then we hear from a wife in

Seattle:

Things I've done that I might not have

if my husband were here:

1) Set up the TV, VCR, amp, and cable

2) Programmed a universal remote

3) Put my clothes in both sides of the

dresser instead of squishing them into just half

4) Assembled a table

5) Slept alone for 39 days and counting

6) Watched Gilmore Girls every Tuesday without argument (for once!)

7) Ate cereal for breakfast and dinner

8) Used the power-drill...twice

Being alone provides some unique

opportunities and helps you discover new interests. I liked the buzz of the

power drill, the burn in my arm from the weight up over my head. I like having

ultimate, un-interrupted, guilt-free control of the remote. I like having time

to plant a garden, to use the shovel. I decidedly don't like spending nights

sitting alone on the couch, but that has pushed me into new activities, more

involvement, and there is nothing wrong with more distractions.

RCH: Yes, blessed be the distractions.

EDITOONERY

Matt

Wuerker has found employment. At last. Sort of. Wuerker has earned his living

for the last 25 years as a freelancer, but starting November 21, he’ll be the

staff cartoonist for The Capitol Leader, a

new newspaper in Washington, D.C. “I’ve been self-employed for so long I just

pray I remember to pull my pants on when I go to work,” he said in the report

posted at editorialcartoonists.com, the website of the Association of American

Editorial Cartoonists. The Capitol Leader will be published three times a week while Congress is in session, competing

with Roll Call and The Hill. Wuerker heard about the new

paper a couple months ago and submitted samples. “My editor sees the intrinsic

value of having original [editorial] cartoons from an in-house

cartoonist—imagine that!” said Wuerker. He’ll also do caricatures and other art

for the paper, and he’ll keep doing some freelance work.

One of editoonery’s Grand Old

Masters, Paul Conrad, who was forced

into retirement in 1993 by his host paper, the Los Angeles Times, but keeps on turning out cartoons for

syndication several times a week—“As long as I’ve still got interest, I don’t

see any sense in quitting”—is the subject of a PBS hour-long special in the

“Independent Lens” series. Conrad, who’s a peevish opinionated 82 these days,

is as “combative” as ever, says Lynn Elber, the AP’s tv writer. And he clearly

relishes uttering a bon mot that will

shock, which he does with a fiendish grin several times during the hour.

Conrad’s ire is directed sometimes at his own profession. He has little regard

for the current trend among some editoonists for comic strips rather than single

panel cartoons. Said he: “It’s dialogue, long conversations, from one panel to

another. Some have a political point but when you get finished reading them,

you knew that at the beginning. So what am I doing reading ’em?” And he has no

use whatsoever for political commentary on the comics page. “Who the hell’s

gonna go to the comics page to find out what’s going on with any given

political subject?” he snorts. The program shows a great number of Conrad’s

cartoons, too many, alas, without readable captions—and the artform, remember,

is a blend of pictures and words—and the images are too fleeting, but there are

enough of them to convey the undeniable truth that Conrad is a master of the

visual metaphor. I remember one of his first stunningly effective ones: during

the worldwide unhappiness over South Africa’s apartheid, he drew the continent

as the head of a black man, thrown back, mouth open in a silent scream. I

suppose Conrad did metaphorical images before that, but that one was so

powerful, that he latched more firmly than before onto the image as the vehicle

for his opinion. Words were incorporated into the image, but the image alone

was the sledge hammer driving the point of the words home.

One of the on-the-air consultants is Chris Lamb, author of Drawn to Extremes, a recent, and very

good, historical review of editorial cartooning in this country. At one point,

he asserts that only about 3 percent of the nation’s daily newspapers have

full-time editoonists on staff; that translates to about 45 papers, but I think

there are almost twice as many full-time political cartoonists at work. The

profession is among the endangered species, no question, and in days of yore,

editoonists were much more numerous. But 3 percent is a tragic low ebb, and I

don’t think we’re there yet.

What

To Do After the Election. On Monday,

November 6, the day before Election Day, Jim

Borgman, who’s celebrating his thirty-year anniversary as the staff

political cartoonist at the Cincinnati

Enquirer, pondered aloud at “Borg’s Blog” the dilemma of the editorial

cartoonist on the day after Election Day. “It’s nearly impossible to say

something worthwhile in the Wednesday morning newspaper on the day after an

election,” he wrote. The cartoon must go into production early the preceding evening,

usually before election returns are complete, so the cartoon can’t be about who

won and who lost unless the outcome was a foregone conclusion; and if that’s

the case, what’s so important as to deserve cartoon commentary? The

predictability gives that cartoon “a hollow feel,” Borgman said. And if the

races were close, what editoonist would hazard a guess, however educated, about

the outcome? The solution for many editorial cartoonists is to turn away from

the election and comment on some other issue, Borgman said. But “this tends to

make one look clueless, commenting on, say, global warming or the Bengals’

season when everyone else wakes up wanting to talk about election results.” Too

often, he continues, the day-after cartoon comments “on the need to clean up

the yard signs.” There is no good solution: “You can’t write (or draw)

journalism before it happens,” Borman concludes.

The political cartooner’s

predicament, however, suggests a pleasant pastime for the day after—surveying

the editoon landscape to see how the inky-fingered fraternity sorted through

the lack-luster options available to them. Borgman, for instance, focused on

state races, which, in Ohio, will doubtless reverberate in the next national

election: if the Grand Old Party is no longer in control of the state

apparatus, then perhaps the voting in 2008 won’t be tampered with. Happily, the

Republicans lost widely, so Borgman appropriated an Iraq invasion image,

depicting the GOP elephant as a statue being toppled from its pedestal in front

of the state house. Safe enough. Borgman’s comment is a workmanlike achievement

but nothing startling and doesn’t intimate anything for 2008 or fixing

elections. I haven’t scanned the entire national output for the day, but I

found four that seemed above the cut of ordinary clever, and in one case, even

a little edgy. Plagiarism Again. At the New York Post, editoonist Sean Delonas was caught in what some

think is an act of plagiarism. His “America’s Referendum” cartoon reminded the

Gawker at gawker.com of a Jim Borgman cartoon from 1990. Here are both. The test of the cartoonist’s skill

is in how effectively he uses an image, not in whether the image is entirely

original with his cartoon. Borgman’s use of the dominoes in his 1990 cartoon

was far more potent than Delonas’ use of the same device. In 1990, most of us

still remembered the “domino theory” that inspired our disastrous Vietnam

adventure: the theory was that if one country “fell” to communism, then the

next country would soon fall, and so on. Like dominoes in a row, one country

would topple the next and so on until the whole world was communist. Borgman

used the self-same domino theory, symbolized by the dominoes, against the

communist regime in the Soviet Union, which heightened the drama in Gorbachev’s

fall from power and the ultimate collapse of the Soviet communist monolith.

Applying the domino theory to the Bush League in the recent election doesn’t

work as powerfully. Incidentally, one of the editoon fraternity, commenting on

Delonas’ alleged swipe of Borgman, noted that he had a much older example of

the same image being used in a Mike

Peters cartoon done during the Nixon era, long before 1990.

A few weeks ago, the student

cartoonist at Harvard’s campus newspaper, The

Crimson, was accused of stealing the image of North Korea’s Kim Jong II

with his oddly erect hair-do transformed into the mushroom cloud of an atomic

bomb explosion. Daryl Cagle was one

of several editoonists whose work was cited as being the inspiration. Cagle

said he drew his “mushroom-do Kim” three years ago. Cagle, at his blog (http://Cagle.MSNBC.com), noted that

political cartoonists frequently come up with the same image at about the same

time. In the cultural backwater that we have occupied for several decades,

literary and Biblical allusions no longer work: too many of the body politic

are no longer familiar enough with Shakespeare or the Bible for images invoked

from either to have impact. Editoonists are forced to rely on popular culture

for their images—television programs and advertising campaigns, mostly. Under

the circumstances, it’s not too surprising when we see the same imagery being

used by several cartoonists addressing the same issue. At his editorial cartoon

website, Cagle has coined a word for such occurrences whenever five or more

such duplications surface: he calls them “Yahtzees,” using a term from a game

by that name. Cagle goes on: “Editors are as much to blame for this phenomenon

because they all want the same thing from cartoonists: Jay Leno style funny

jokes about the news that convey no opinion at all. ... When editors all want

the same thing from a cartoonist, and cartoonists are all drawing on the same

topics at the same time [and fishing in the same shallow pool for imagery, as I

said], it is no wonder that we come up with the simple, easy,

first-gag-that-comes-to-mind.” In the case he was discussing, the “mushroom-do

Kim.” Delonas isn’t dealing with a popular culture image that is as current as

it once was (when Borgman used dominoes), but it can scarcely be called an act

of plagiarism. Not in cartooning. Not yet. And perhaps never.

The current spate of accusations

about plagiarism in editooning undoubtedly stem from the detection of other,

more blatant, thefts that have been committed in the prose columns of some of

the nation’s top newspapers. Alarmingly, fiction as well as robbery has been

perpetrated in newsstories. As a result, journalistic antenna are up; every

editor is on guard, sniffing for plagiarism and fabrication anywhere in his

newsprint. Suddenly, those in a profession that advocates “swipe files” as a

tool of the trade are being held to a standard their training and traditions

never contemplated. Confusion reigns. Most plagiarism is not illegal, by the

way: it’s typically thought to be highly unethical but usually not against the

law—unless someone is making great wads of lucre from someone else’s idea or

infringing upon copyrighted material, in which case, it’s copyright law that’s

being broken, not plagiarism law, which, to the best of my knowledge, doesn’t

exist. Regardless, cartoonists who want to achieve a measure of professional

standing should probably not use images in precisely the same way that others

in the fraternity have used before them. Strive for originality. That’s what

the great ones did, and do. That’s why Paul

Conrad is a great political cartoonist. He also sometimes misfires

completely, using an image that is either ambiguous or too removed from popular

comprehension. That’s the risk he takes for originality.

Editoon

Roundups

Many of the editooning brotherhood complain about the quality of the political cartoons published in weekly roundups. Said Daryl Cagle, voicing a commonly held opinion: “Newsweek magazine is an ugly culprit, reprinting opinionless gag cartoons, week after week. ... Time does it, too, and with all the hundreds of cartoons to choose from every week, they often print the very same cartoons in their cartoon roundup that Newsweek does.” The problem begins at home, though, with the newspaper editors who prefer jokes in the editorial cartoons they publish: jokes won’t anger subscribers who might, in a fit of pique, cancel their subscriptions. Even if editors didn’t demand more chuckles than knuckles, they’dget a certain number of the former. Cartoonists are, after all, cartoonists, and they like to vary their pitches, sometimes producing a gag cartoon instead of a thought-provoking one. (Gag cartoons, in this linguistic progression, must, perforce, gag the readers if thought-provoking ones provoke thoughts.) It’s refreshing, in this tepid climate, to discover a weekly newsmagazine that publishes opinionated cartoons. The Week publishes a page of them every week, sometimes two pages. The cartoons are not necessarily sterling examples of the art of visual metaphor. And not every cartoon is a hard-hitting one, but most are; and none seem to go just for a laugh. Here’s the page from October 27.

BOOK MARQUEE

Short Notes about New Books, Just

Arriving or Just About To

Jeff Danziger has a new collection of his political cartoons out, Blood, Debt & Fears: Cartoons of the

First Half of the Last Half of the Bush Administration (320 7x10-inch

pages, black-and-white; paperback, $14.95). Jules Feiffer’s back-cover assessment is beautifully pungent and

wholly accurate: “Jeff Danziger’s muscular line cracks like a whip, flailing

into shreds the hypocrisies that make up the body politics. Drawing like a

dream, he renders these smart, witty (often hilarious) comic nightmares. His

rage is our solace.” I love that: “His rage is our solace.” Indeed. Danziger

can’t caricature worth a toot, but his draftsmanship otherwise is superb,

easily the equal of the other drawing masters, Pat Oliphant and Jim

Borgman. The stunning cartoons arrayed chronologically (and dated) in this

volume are accompanied by Danziger’s prose comments; intended, probably, to put

each cartoon into the context and climate that inspired it, his remarks have a

bite of their own, too.

Another editoonist who never pulls

his punches, two-time Pulitzer and one-time Reuben Award winner Mike Luckovich at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, has a new

collection, too: Four More Wars (248

6x8-inch pages, b/w; paperback, $16.95). This compilation is arranged by

topic—Bush, Cheney, Iraq, 9/11, Campaign 2004, etc.—and Luckovich supplies a

short introduction to each section. “Bush is a walking disaster,” he writes to

kick off that section. “In virtually every aspect, America is in worse shape

because of his actions, from his handling of Iraq, to the tax cuts, to ignoring

global warming, Katrina, the war on science, illegal wire-tapping, torture,

Harriet Miers—the list is endless.” But, he continues, “two groups have

overwhelmingly benefitted by having Bush in office: rich people and

cartoonists.” The book includes some intriguing extras: Luckovich’s reports on

his trip on Air Force One with Bill Clinton (and the cartoon, a

self-caricature, that Clinton drew at Luckovich’s request), his visit to

Rumsfeld’s kingdom in the Pentagon where he participated in a macho one-armed

push-ups contest with one of the brass, and the White House Press Corps Dinner

that he and fellow editoonist Mike

Peters attended, prankishly affixing phone cords in their ears in imitation

of Secret Service operatives. Henry Kissinger assumed they were security

personnel and asked them to escort him; they did. Later, they stationed

themselves at the metal detector through which all guests had to pass, “telling

people they had to take their shoes off and stuff like that. Nobody did,

believe it or not.”

As coincidence would have it—coming

hard on the heels of our long disquisition last time on Charles Addams—the master of the macabre is on a calendar for 2007,

an “engagement calendar” measuring 8x14 inches and offered at a bargain price,

$4.98, by Daedalus Books at www.salebooks.com. At the same

destination, you can find Patrick

McDonnell’s 2007 Mutts wall

calendar, 12x24 inches, for another mere $4.98.

“If

‘The Flintstones’ has taught us anything, it’s that pelicans can be used to mix

cement.” —Dunno Who

Rancid

Raves Gallery

A new feature of our online extravaganza this time, a gallery of art without much reason for being here except as examples of the craft of cartooning. At comic conventions last summer, you could buy any number of “sketchbooks” created by any number of cartooners. Among them, increasingly, are sketchbooks by animators moonlighting in the static realm. One of them, Chris Sanders, lately of “Lilo and Stitch,”populated his booklet with charming Lilo-like sexpots almost too cute to be sexy. And one of his drawings, as I told him when I bought the booklet, offered the most ingenious use of a bikini I’ve ever seen—as a sort of hammock. The visual imagination that resulted in this highly inventive cheesecake is very nearly sublime.

COMIC STRIP WATCH

On

November 8, one of the cubicle-dwellers in Dilbert died in his cubical. On November 9, Carol, a co-worker, tells the

pointy-haired boss, “We’ve got a dead guy in cubicle D-32.” This may be the

first time death has been referred to in a comic strip in such blunt terms.

Eighty years ago, no syndicated cartoonist could mention even sickness. Now, we

have death. And death as a joke. And this, I strongly suspect, is a step

forward in civilization. In the direction of candor, anyhow. ... In Sherman’s

Lagoon, neither of the critters running for office, Fillmore the turtle

and Hawthorne the hermit crab, won election. They were defeated, they are told,

by a write-in candidate—namely, “None of the Above.” “Humiliating,” says

Fillmore. “Beaten by a nun,” says Hawthorne. A pun of awesome implications. And

religion in a comic strip, too. Will the outrages ever cease?

Meanwhile, in Gasoline Alley, as

foretold here a few weeks ago, ol’ Walt Wallet, 106 years young, has traveled

by Toonerville Trolley to the Old Comics Home, where, on November 10, we see

among the crowd greeting him Li’l Abner, Terry (of Pirates fame), Little King,

King Aroo, Andy Gump, Penny, Joe Palooka, Smokey Stover, Offisa Pupp, and

others, which, alas, appear too small online for me to detect by actual

identity. As usual, cartooner Jim

Scancarelli has performed miraculously in presenting these vintage

characters, only slightly streamlined for modern consumption. Bravo. ... In Brooke McEldowney’s 9 Chickweed Lane, we are now back on the

farm with Edda’s mother, the former college professor Juliette Burber, who is having

repeated encounters with the mysterious Thorax, a reputed alien wearing a

bucolic bib-overall disguise. Here’s the dialogue from November 8: Juliette

says to Thorax, “Your trouble is, you’re insane. You won’t come to grips with

reality.” To which Thorax says, “With what part of reality have you come to

grips, Dr. Burber?” Silence transpires for two panels as Juliette ponders the

matter; then, in the fourth panel, she says: “Okay—I take back the word

‘insane.’” Thorax responds: “I’d rather you didn’t. I’m not done with it yet.”

The most refreshing comedic nonsense in comics, no contest.

A NEWCOMER ON THE COMICS PAGE

Our

culture seems to foster enough would-be cartoonists to populate a good-sized

suburb. Every year, feature syndicates receive thousands of submissions of

ideas for comic strips and panel cartoons. King Features, I read somewhere,

receives between 5,000 and 7,000 a year. But King launches only one or two, so

when a new strip comes out, it deserves a serious look. King’s latest, which started

November 12, is The Brilliant Mind of

Edison Lee, which dwells on the mental gyrations of a ten-year-old boy

genius interacting with his father, mother, an in-house grandfather, and his

“naive laboratory assistant,” a lab rat named Joules. The strip’s creator, John Hambrock, has been laboring in the

vineyards of commercial art since graduating from college in about 1985, for

the last decade or so, heading his own agency, In-House Communications, which

specializes in industrial advertising, packaging and print design. The first

thing we noticed about Edison Lee is

that it is drawn in a thoroughly traditional cartoon manner. In other words, it

hasn’t the fashionable “contemporary look,” a phrase usually deployed to avoid

saying something is badly drawn by someone who can’t draw. Hambrock can draw.

His style is not startling in any way, but it is wholly competent, displaying

both a confident line and a sure composition sense. Edison’s visage and

diminutive dimension suggest what Hambrock later confesses—that he was smitten

with Ernie the Elf while working on the Keebler account at one of his previous

employments. The second thing we noticed is that the strip is determinedly

political: almost every strip gives the precocious Edison an opportunity to

make a barbed remark about the state of American politics, all with a marked

inclination to the left. Said Hambrock: “His young age and innocence allow me

to present social and political commentary in a completely innocuous way. The

strip addresses issues and topics that straddle the political spectrum, but it

does so through the voice of a very likable child, which makes what he is

saying a little less offensive and more digestible to readers. I created this

strip purposefully with a little something for everyone,” he continued.

“Readers may not always agree with Edison’s particular viewpoints on issues,

but I’m hoping that he will at least get them to think for a minute and laugh.”

In one strip, Edison’s father is

complaining about how long it will be before he’s eligible to be shop

foreman—“two whole years,” he says, “—any idea how long that is?” His wife

responds: “Well, if you’re a giant sequoia, it’s a few minutes. To a hamster,

it’s more like a lifetime.” And then Edison pipes up: “For a Democrat looking

ahead to 2008, it’s an eternity.” In another strip, Edison asks his father if

he’s ever cheated on his taxes. “Absolutely not,” says Dad. “People who do

cheat wind up getting caught at some point. There aren’t many ways to hide

income from the government these days.” And Edison says: “Dress it up as Osama

bin Laden, and I guarantee they’ll never trace it.” While it’s nice to realize that a

syndicate thinks there remains a place on the funnies pages of American

newspapers for another liberal point-of-view, Edison Lee’s commentary is fairly tame and so calculated that the

punchlines are very nearly predictable. The political zingers are almost

gratuitous. They are also, as we might expect in the sales kit samples I’ve

been quoting, somewhat generic, as if taken directly from a liberal “talking

point” list. The reliance upon conventional political cliches can be explained

by the nature of the syndication enterprise. The kit, after all, is intended to

demonstrate to prospective client newspapers what the strip is about. Given the

duration of the initial sales period—several weeks, even months—the commentary

must have a fairly long life, and that means Hambrock can’t comment on the news

of the day. Perhaps, once the strip gets going, Edison’s observations will

become more inventive and edgy by reason of their more immediate reflection of

current events. The sales kit has surely laid the foundation for such an

eventuality, and we applaud both King and Hambrock for braving what, until

quite recently, was the prevailing right-wing climate by lobbing some

left-leaning utterances into the public prints, however generic the content

must necessarily be during the launch period. We’ll keep an eye out.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis

Miller adv.

Cinemactress

(a quaint old Time mag coinage)

Scarlett Johansson told Allure that

people who suppose she is sexually available are mistaken. But, she goes on, “I

do believe that human beings are not instinctually monogamous. On some basic

level, we are animals, and by instinct we kind of breed accordingly.” Must be

something about the movies: in the U.K., Sienna Miller believes the same thing.

She kicked Jude Law out of the house last year after she found out he was

indulging himself with his children’s nanny, but she’s lately had second

thoughts. “Monogamy is a weird thing to me,” she said in Rolling Stone, “—it’s overrated because, let’s face it, we’re all

fucking animals.” And it used to be, some eons ago, actresses were socially

unacceptable because misguided respectable people thought they were little

better than prostitutes.

The U.S. Postal Service is

modernizing according to The Week. They’re removing tens of thousands of those street-corner mailboxes because, it

is supposed, most people pay bills online and communicate by e-mail. For the

same reason, USPS will be phasing out its 23,000 postage-stamp vending

machines. The first to go will be those in low-traffic areas, just as the first

of the mailboxes to disappear were those that were “underused.”

In the Bush League’s faith-based

initiative, 98.3 percent of the $1.7 billion in federal funds awarded to

religious organizations went to Christian groups, saith the Boston Globe. Jewish organizations got 1

percent; Muslim, 0.34 percent; interfaith, 0.16 percent. Incidentally, I read

in the New York Times some weeks ago

that day care centers run by religious groups don’t have to comply with the

regulations other day care operations do because religions are exempt from

certain kinds of governmental interference, part of the separation of church

and state tradition. Privately funded day care centers, though, must comply

with the rules and also fill out small mountains of paperwork. We live in interesting

times.

In Boston and fourteen other U.S.

cities, according to Jane Lampman at the Christian

Science Monitor, Muslim Americans included in the annual month of Ramadan a

“Humanitarian Day for the Homeless” and set up charitable centers to distribute

food, clothing, hygiene kits, and, for children, toys. Charitable giving is one

of the “five pillars of Islam,” and this year’s Humanitarian Day expected to

serve 18,000 homeless and needy Americans of all faiths.

Tics & Tropes

“Men never do evil so completely and

cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction.” —Blaise Pascal

“Be good and you will be lonesome.”

—Mark Twain

“Good judgment comes from

experience, and experience—well, that comes from poor judgment.” —A.A. Milne

“There are plenty of good five-cent

cigars in the country. The trouble is, they cost a quarter. What this country

really needs is a good five-cent nickel.” —Franklin P. Adams

The Froth Estate

The Alleged News Institution

According

to the New York Post, CBS’s Evening News,

starring Katie Couric, is back where it started, in third place, with 7.4

million viewers. Charles Gibson got ABC to second place with 7.9 million

viewers, but Brian Williams outshone both his competitors, and NBC racked up

8.5 million viewers.

BOOK REVIEW

Cartoon America

The

Library of Congress, according to James H. Billington, the Librarian of

Congress, “is home to one of the world’s great collections of original cartoon

art.” Because Congress itself is just across the street to inspire cartoonists,

I’m not surprised: with all those legislative shenanigans transpiring so close

by, the cartoons should be great. By reason of its unfettered non-sequiturial

grandeur, that statement is so completely beside the point as to be simple

nonsense. But the Library of Congress (LOC) is neither simple nor nonsensical.

It was founded in 1800 as a reference resource for Congress. At the time, it

was believed that lawmakers ought to know something about the matters they

create laws for; that quaint belief has been discarded in recent times.

Nowadays, all that is required of a Congressman is that he channel to his

district back home as much of the nation’s tax revenue as he or she can. The

LOC started collecting and preserving cartoons and caricatures almost at once.

And Congressmen, too, have ever since then been eager to accumulate their own

private collections of cartoons, giving special preference to those that

ridicule them. Thomas Jefferson aided and abetted the original LOC scheme by

leaving all his books to the Library of Congress, and the LOC has grown and

improved its scope ever since with gifts from other public spirited souls. One

of the most recent acquisitions is the Art Wood Collection, “the most

comprehensive private collection of original, historical American cartoon art

known to exist,” Billington assures us. Again, I’m not surprised—at the extent

of Wood’s collection. He was (and still happily is, at last report) one of the

great collectors of the world.

Art

Wood began collecting original cartoon art at the age of twelve or

thirteen, and he’s probably in his eighties now, so he’s been collecting a long

time. He started by visiting the Washington

Star’s editorial cartoonist, Cliff

Berryman, who gave him one of his son Jim’s cartoons and one of his own.

When Wood found out that syndicates routinely destroyed comic strip art once it

had been reproduced and distributed, he persuaded the pertinent factotums to

let him paw through the heaps of original art for the best samples for his

collection. And when Wood became an editorial cartoonist himself, he approached

his colleagues; he even approached me one time, and I sent him one of my

unpublished gag cartoons (of which I had several thousand). So now I’m in the

Library of Congress. Wood had original work from all the great names in

cartooning—Bud Fisher, George McManus,

Hal Foster, Milton Caniff, Chester Gould, Alex Raymond, Al Capp, to name a

few of the “moderns.” He also had originals by 19th century American

’tooners—Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman, F.R.

Opper, Thomas Nast, A.B. Frost, and other giants. One of Wood’s hobbies

once he became an editoonist was getting Presidents to autograph one of his

cartoons about them. With thin-skinned Presidents, this proved problematic:

they didn’t want to sign a cartoon that was critical of them—Lyndon Johnson,

for instance, who referred to Wood with some colorful Texas range-riding argot.

But Wood stage-managed a publicity event with other cartoonists in which the

final moment was devoted to Johnson autographing each of the cartoonist’s

caricatures of him. Naturally, a Wood caricature was among the array, and

naturally Johnson signed it, not wanting to create an incident in front of tv

cameras. Wood rehearses many of his collecting adventures in his 1987 book, Great Cartoonists and Their Art, which

reproduces in pristine condition many of the originals in his collection. Wood,

by this time nearly obsessive about acquiring original cartoon art, shamelessly

retails stories detailing the ruses he sometimes resorted to in order to obtain

originals.

In 1995, Wood opened a museum in

Washington, D.C. to display his collection, the National Gallery of Caricature

and Cartoon Art. Passionate and knowledgeable about the history of cartooning

as well as the craft, he took me to lunch one day at the Press Club and we

enjoyed a few hours of deeply pleasurable conversation. Then he gave me a tour

of the museum around the corner at 1317 F Street. It was due to open in a few

weeks, but at the moment, its walls were bare, being painted in the general

refurbishment of the place. It was a tidy gallery and a Like most Abrams productions, the

book is a delight for the eye. Its giant pages are capable of reproducing rare

art at discernible dimensions. Here’s Homer

Davenport’s famous caricature of his boss, William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Keppler’s picture of himself and

editors in conference at Puck,

beautiful reproductions of some of Ollie

Harrington’s delicately shaded Dark

Laughter cartoons from the 1960s, to mention too few. The book is divided into sections by

cartoonist—Lyonel Feininger, Rose

O’Neill and Nell Brinkley, Winsor McCay, John Held Jr., Frank King, Chic Young, and Charles Schulz and Mort Walker, and so on. Each section

is introduced by a different writer, often an authority on the subject: Art Spiegelman for Feininger, Trina Robbins for O’Neill and Brinkley, Brian Walker on The Gumps and Barney Google and Wash Tubbs; Patrick McDonnell on Herriman; Brumsic

Brandon Jr. on Harrington; and I did Schulz and Walker. Lynn

Johnston writes about “The Joy of Writing” For Better or For Worse; editioonist Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher, about “Caricature as Weapon”; David Levine, “Caricature and

Communication”; Bill Griffith, “Underground Comix.” The reach of the book is no less than a history of

cartooning in America, and under the editorship of Harry Katz, erstwhile graphic

arts curator in LOC’s Prints and Photographs Division where the collection is

housed, it comes comfortingly close. His long introductory essay scans the

cartooning landscape, and Katz goes further back into the dim recesses of

European origins than I’d expected—Honore

Daumier is included in both prose and picture, and John Tenniel, and Jose

Guadalupe Posada Aguilar. From France to England to Mexico—I wouldn’t have

thought to include so many cartoonists from other countries in a history of

American cartooning. As a whole, the essay and the illustrations throughout the

book lean in the direction of “museum art,” self-contained single-picture

artworks that can hang on a wall and be admired for their artistic technique.

Katz’s essay is long on 19th century antecedents of cartooning and

short on some aspects of modern cartooning—the adventure comic strip, for

instance, and the soap opera strip, receive much less attention than I would

have imagined they would. Terry and the

Pirates is represented in the art, ditto Prince Valiant; but both are reproduced at quarter-page size, too

small for the details of the artwork to be admired. Saul Steinberg’s self-portrait, on the other hand, gets an entire

page to itself, a rather too generous allotment of space for his relatively

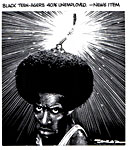

simple albeit intriguing penwork. One last word—and picture: Paul Conrad’s 1977 cartoon about

teenage unemployment among African-Americans. Elegant art, eloquent statement. Books like this I contemplate with

mixed emotions. They are, alas, the best that afficionados of original cartoon

art can expect these days. Too much original art is now in the files of library

special collections which, unfortunately, are not often enough opened up for

display. And so much original art is, in effect, locked away from public view

forever. Sporadically, libraries produce books like these, and for that, we

must be enormously grateful because we would not otherwise see these rarities.

Yes, libraries and museums preserve the art that might otherwise evaporate into

the ether or be confined to private collections. But in libraries and museums,

preservation necessarily, alas, takes precedence over the actual purpose of the

art, which is to be seen. No one is to blame for this annoying state of

affairs. Without libraries and museums taking an interest in original cartoon

art, we’d probably lose most of it over the decades. Everyone is simply doing

their duty. But we need more wall space for displaying the art. And more books

like Cartoon America.

GRAFICITY

Another Graphic Novel

Brian K. Vaughan’s new graphic novel, Pride of Baghdad (136 7x10-inch pages in color; Vertigo, $19.99),

bears a purposefully ambiguous title that multiplies the book’s meaning, making

it an allegory about tragic loss and vaulting aspirations gone awry. On the

narrative rather than allegorical level, the book rehearses the adventures of a

pride of lions, four of them, that escapes Baghdad’s zoo when it is bombed

during the U.S. invasion in 2003. Even before the bombs begin to fall, one of

the pride, the lioness Noor, has been agitating other animals in the zoo to

turn on their keepers and break out of their cages. But before anything comes

of that plan, the bombs free all the animals. Rendered in the best Disneyesque

anthropomorphic naturalist manner by Niko

Henrichon, the lions roam the deserted streets of bomb-torn Baghdad,

looking for food. They run from an invading phalanx of tanks and meet a

good-sized sea turtle, whose function in the story is to explain the “war” and

the evil of oil, which, spilling into sea, poisoned numerous of his kind. The

lions come upon a dead human and Zill, the male lion, is about to make a meal

of the corpse over the objections of the others, who remember humans as their

“protectors,” when a small herd of horses gallops by. Food on the hoof, because

it is guaranteed fresh, is more attractive, and the lions set off after the

horses, following them into a deserted palace, where they encounter another

lion, chained to the wall, de-clawed and de-fanged, an obvious allusion to the

tortured populace under Saddam. “Those who hold us captive are always tyrants,”

says Noor.

Just then, a gigantic bear shows up.

His unexplained presence in the palace and his pose as the chained lion’s

keeper (or torturer) imply that he is a simulacrum for the country’s erstwhile

dictator. When the bear declares the lions his smorgasbord, Zill attacks him,

and a bloody fight ensues. But the bear is killed by the horses, stampeded over

him by another of the lions. The pride leaves the palace and beholds a

magnificent sunset that tints the city as well as the sky a royal albeit bloody

red. Just as darkness falls, a group of American soldiers arrives, and,

thinking the lions might attack them, they kill all four of the beasts.

“I didn’t want to put them down,”

explains one soldier, “but—.”

“I know,” says a companion, “you

didn’t have a choice.”

“These things aren’t wild out here,

are they?” asks the first soldier.

“No, not wild,” says the second,

“they’re free.”

And they are also dead. The next

page shows us a flight of aircraft dropping bombs, and after that, a two-page

spread of a darkened cityscape with fires burning in the distance. A caption

reads: “In April of 2003, four lions escaped the Baghdad Zoo during the bombing

of Iraq. The starving animals were eventually shot and killed by U.S.

soldiers.”

On the last page, Vaughan gives the

book’s title its other meaning with a single, full-page picture. We see a

monumental statue of a lion standing with its paw on the chest of a man, who is

fighting off the big stone cat. Earlier, the meaning of this tableau was

explained by the turtle: “Legend says that as long as that statue’s still

standing, this land’ll never fall to outsiders.” That’s the pride of Baghdad.

The book has the kind of thematic

complexity that can keep literary critics pawing through the rubble for hours.

If the lions represent the Iraqi people, yearning to be free, and if their

escape from the zoo represents the initial success of the American invasion,

then the slaughter of the lions by U.S. troops probably stands for the ultimate

failure of the invasion: the newly freed population is “killed” by the

well-meaning invaders, who, under the threat of the insurgency, “didn’t have a

choice” but to defend themselves. But if those they killed were not “wild” but

“free,” where does the parable leave us? With blood on our hands, it seems, our

best intentions frustrated by our inability to see that the lions were simply

contemplating the sunset, not planning to attack—unless, as it happens, they

are provoked. With the emblematic last page, however, the tragedy turns

defiant, giving the Iraqis the kind of victory that will endure even as it

inspires further resistance to the invaders.

The pictures throughout serve

dramatic as well as narrative purposes. Henrichon’s lions, delineated with a

sketchy and therefore “furry” outline, conjure up “The Lion King,” including,

even, an innocently ignorant cub, forever asking questions. “What’s a horizon?”

he asks when Zill describes a remembered moment of past freedom (a description that

gives the sunset scene at the end a gloss beyond simple visual beauty): “At the

end of every day,” Zill says, “I watched as the horizon devoured the sun in

slow, steady bites, spilling its blood across the azure sky.”

The book is beautifully drawn, Henrichon’s

illustrative elan on display with every page, every scene rendered in exact

detail, no fudging, no shortcuts. Double-page spreads invariably serve

to heighten drama. On the first page of the book, a raven warns Zill that “the

sky is falling.” Zill scoffs, but then, upon turning the page, we encounter a

vast expanse of sky from his point-of-view, and we, and he, see warplanes roaring

overhead. “Ah,” says Zill, comprehending. As the lions leave the wrecked zoo,

we turn the page and witness a two-page scene of mass confusion with animals

rushing by in panic as bombs continue to fall in the distance. Then,

underscoring Zill’s remark that the newly freed lions have “other things to

worry about,” we see on the very next page a giraffe decapitated by a wayward

shell, his head exploding right before us. As the lions set foot outside the

walls of the zoo for the first time, we turn the page into another two-page

spread that puts the lions in the midst of a vast plain under a man-made arch

formed by sculpted crossed swords.

Color serves the drama, too. In the

zoo and in the surrounding forest where lions first walk free, the colors are

earth tones, naturalistic. In the midst of the bombing and in the smouldering

streets of Baghdad, the colors are yellow and orange, tending to red,

suggesting the heat of the desert sun, and when the animals enter the deserted

palace, the palette turns cool—dull greens and muted blues, noticeably dropping

the temperature inside those walls.

In theme and in execution,

skillfully deploying the visual resources of the medium, Pride of Baghdad is a vivid demonstration of the literary

seriousness to which graphic novels can lay claim.

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY

Okay:

so I was wrong about the outcome of the recently concluded election. What do

you expect? I’m a typist, not a prognosticator. When I predicted that the GOP

would remain in control of Congress, both houses, I was trying to decompress my

own expectations, to dial back my hopes so I wouldn’t be too disappointed.

Again. I was hoping for a Democrat victory, and all the pollsters were

predicting one; so to guard against experiencing another Great Disappointment,

I pooh-poohed the possibility. But now—now the Democrats are seemingly the

ruling party in Congress. Can we expect miracles—the end of the Iraqi nightmare

and dependency on foreign oil? Not likely. Can we expect wholesale roll-backs

of odious Republican legislation? Not likely. Remember: Democrats are

politicians, too—“career pols,” in fact (see below). They are as dependent upon

big money contributions to their re-election campaigns as Republicans are. Yes,

here in the warm glow of a long awaited victory for some group other than the

Bush League, I have high hopes. But I secretly suspect we’ll just be distracted

by a new razzle-dazzle and not much helped over-all. We’ll see. The noises

coming out of the Democrats in these first few days are heartening, but we’ll

see.

Those of us who remain, still,