|

||||||||||||

|

Opus 185:

Opus 185 (June 5, 2006). The Headline “Event” this time is our

report on the Reuben Weekend of the National Cartoonists Society—namely, who

won the Reuben and all those division awards. And we throw in numerous

fascinating tidbits along the way. Our other major features include an appreciation

of Alex Toth, who died May 27, and a pondering of the advent of the “lesbian

lipstick” Batwoman. Here’s what’s here, in order: NOUS R US —New Garfield movie, top ten film characters include

three (or four?) comics characters, who’s been writing Blondie all these years, prototypes of the X-Men in fantasy

literature, rare “lost” Winsor McCay art

found, comics foster reading skills, Harper’s banned in Canada for its publishing of the Danish

Dozen; COMIC STRIP WATCH —More

cross-over nonsense, new artist on Judge

Parker, two new comic strips: A

Lawyer, A Doctor and A Cop and Pajama

Diaries; submitting to The New

Yorker; THE REUBEN WEEKEND— Who

won? and all that; BOOK MARQUEE— Arf Museum and the reappearance of the

lost Backstage at the Strips masterpiece; REPRINTZ— The Long Road Home, The Big Book of Zonker; FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE— A great

gatefold, “lipstick lesbian” Batwoman; ALEX

TOTH— Stylist supreme, dies at his drawingboard; and a little Bushwhacking,

just to keep in practice. And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate

the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can

print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your

leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

NOUS R US

All the news that gives us fits.

On

June 1, the Dalai Lama, refugee spiritual leader of Tibet, honored Belgian

cartoonist Herge (aka Georges Remi)

for raising awareness of Tibetan culture in one of his classic adventure

tales. Simon Melick, spokesman for the

International Campaign for Tibet, is quoted by World Entertainment News

Network: “For many people around the world, Tintin

in Tibet was their first introduction to Tibet, the beauty of its landscape

and its culture. And that is something that has passed down the generations.”

... The inaugural New York ComiCon, held the last weekend in February 2006 and

so well attended (reputedly, 33,000) that not everyone could get in, will

re-convene next February 23-25 but upstairs at the Javits Center where it will

have twice the space. Show organizer Greg Topalian said there’d be longer daily

hours, too, and he “promises better pre-registration procedures, new technology

and a much expanded and better trained registration staff,” saith Calvin Reid

at PW Comics Week. ... The second Garfield film, “Garfield: A Tale of Two Kitties,” is scheduled to open in theaters on

June 23 with Bill Murray again voicing Jim Davis’comic cat. ... Three of Entertainment Weekly’s top ten most

powerful film characters originated in comics: Wolverine (No. 1), Spider-Man

(No. 3), and Bart Simpson (No. 9); four if you count Shrek (No. 4); June 9

issue.

Sony Pictures has purchased the

North American film rights to Marjane

Satrapi’s graphic novel/autobiography, Persepolis, about growing up in Iran during the Islamic revolution. According to

metimes.com, Satrapi will co-direct the animated film. ... In the program

booklet for the Reuben Weekend of the National Cartoonists Society (see below

for our rambling but terribly informative report), a full-page ad about

Blondie’s 75th anniversary is signed by Dean Young, the ostensible

author of the strip, and John Marshall,

making the first time Young has permitted the name of the man who draws the

strip to surface in anything like a public forum. Young has not, however,

deigned to acknowledge Paul Pumpian,

who has been writing most of the gags for the strip for something like twenty

years. ... The Dutch company that owns Editor

& Publisher has been acquired by a group of private investors operating

under the name Valcon Acquisition BV. With the same purchase, saith E&P, the group bought other

Dutch-owned magazines, including Billboard,

Hollywood Reporter, Adweek, and nearly four dozen others. We don’t know,

yet, whether Valcon Acquisition BV is an Arab company, but nothing surprises us

here at the Intergalactic Rancid Raves Wirlitzer. ... Larry Wright, who retired recently as one of the editorial

cartoonists at the Detroit News,

celebrated his freedom by buying a 2006 Corvette. He told Jenny King at the Detroit News that he’s longed to own a

sporty convertible ever since his father sold his 1951 Ford convertible while

he was in the Army. According to Wright, it was his wife who encouraged the

fulfillment of his life-long dream. “Why don’t you by a new Corvette?” she said.

“That’s the nicest thing you’ve ever said to me,” he replied. Since then, he’s

been seen tooling around the town, giving rides to teenagers.

“X-Men: The Last Stand” set a new

box-office record over the holiday weekend according to Peter Sanderson at PW

Comics Week. In the commentary surrounding the much ballyhooed debut of the

film, it was suddenly discovered, by MSNBC’s film critic John Hartl, that being

a mutant might be a metaphor for being a homosexual: both are social outcasts

despised by so-called “normal” beings. Yeah, well—the mutant group concept can

stand for any ostracized and persecuted segment of society—racial minorities,

f’instance, or, even, teenagers, since adolescents traditionally feel put upon

and persecuted by the parents and teachers. Hartl goes on to point out that the

X-Men, created in 1963, could have roots in other science-fiction works—like

Kurt Vonnegut’s Harrison Bergeron,

which, published in 1961, “deals with a bright boy who stands out too much and

is threatened with brain surgery.” And then there was the 1960 movie “The

Midwich Cuckoos” that treated a group of super-intelligent kids as threats to

mankind. And these, Hartl says, “owe a debt to Olaf Stapledon, the British

writer who specialized in epic tales of martyred geniuses, especially the 1935

novel, Odd John” in which the

“telepathic title character and his fellow ‘wide-awakes’ and ‘supernormals’ are

persecuted, forced to establish an island colony and hunted down by

mercenaries.”

Gregory

McAdory, aka “the Dragon,” is on the road, showing his animated cartoon,

“Dragon’s Ninja Clan,” to throngs of Youth to give hope to “a generation in

need.” McAdory, a former gang chief, was doing ten years in various

penitentiaries around the country, when he started watching the Oprah Winfrey

show, and she turned him around. “I’ve learned,” he told BlackNews.com, “that

there’s more to life than what society deems favorable and acceptable. It was

the challenge of living through my experience that helped shape my mind to

reflect only positive thoughts; to know that I am someone, regardless of my

situation or environment, and which gave me the inspiration and passion to

create my life’s masterpiece.” His animated message features a group of

crime-fighting characters whose mission is to “bear arms with purpose in a

never-ending battle against gangs, drugs and thugs,” using martial arts and

positive hip-hop music to protect the inner-city streets around the world.

McAdory developed the cartoon while incarcerated.

From June 1 to August 31 in the

Reading Room of the Cartoon Research Library at Ohio State University, rare

cartoons by Winsor McCay will be on

display: five original, hand-colored drawings made by McCay for his 1903 series The Tales of the Jungle Imps which he

produced while on the staff of the Cincinnati Enquirer. How these original drawings arrived at CRL involves a

tale worthy of the most fevered expectations fostered among devotees by the

Antiques Roadshow. Until January of this year, none of these drawings were

known to exist according to a CRL news release. Then in January, Lucy Caswell,

curator of the CRL, received a phone call from a stranger who had found some

“old cartoons” among a stack of boxes that had been in her family’s business

establishment for years. Caswell, always skeptical because she receives many

such phone calls from people whose “finds” turn out to have only sentimental

value, agreed to meet her phone caller the next day. When she brought in a

battered cardboard folio and opened it, Caswell knew immediately that a

treasure had been unearthed. Said Caswell: “It’s remarkable that these

originals would turn up in Columbus, Ohio, which is the only city in the

country with an academic library devoted to cartoons. We’re delighted that the

family who found these important works understood that some of them belonged in

an institution where they would be preserved and protected while also being

made accessible to scholars, researchers and students.” CRL acquired only five

of the trove; the finder asked to remain anonymous but presumably will someday

offer the rest of the originals for sale.

Two generations after psychologist

Frederic Wertham insisted that comic books contributed to juvenile delinquency

and rotted the brains of their readers, libraries across the country are

gleefully stocking graphic novels in their young readers sections, according to

Karen Springen in Newsweek (May 22).

Librarians and parents alike see the long form comic book as a bridge that

takes young people from “picture books to chapter books.” Some even maintain

that graphic novels (even comic books) may help kids in future careers,

Springen points out, quoting Hollis Rudiger of the Cooperative Children’s Book

Center at the University of Wisconsin at Madison: “The work force increasingly

relies on the marriage of images and text. Internet information is entirely

image and text.”

In Clay County, Florida, the First

Coast News tv channel aired a story about 29-year-old Christopher McMonigle’s comic book collection, which, valued at

about $30,000, had been stolen from his home. An astute mother saw the

broadcast and remembered that her son had acquired, seemingly overnight, an

astonishing number of comic books. She trotted him down to the sheriff’s

office, whereupon the boy and his six confederates were arrested. Not only had

they stolen most of the comic book collection but some guns and ammunition. In

my day, most mothers who were alarmed about the extent of their offspring’s

comic book collection just threw them all out while their son was off at summer

camp. In Florida, obviously, they do things differently.

The Danish Dozen Flies On. In

Canada, the country’s largest retail bookseller removed all copies of the June

issue of Harper’s from its 260 stores

because of Art Spiegelman’s article

publishing the twelve offensive cartoons and annotating them; see Opus 1984.

The cartoons, claimed Indigo Books and Music, could foment riots with their

attendant property destruction and death. Indigo’s founder and CEO, Heather

Reisman, is getting a reputation: according to James Adams in the Toronto Globe and Mail, she ordered all

copies of Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf removed

from stores in 2001, claiming the book was hate literature. Two years later,

Reisman was one of the founders of the powerful lobby group, the Canadian

Council for Israel and Jewish Advocacy. Meanwhile, in the U.S., two major chain

bookstores, Borders and Waldenbooks, carry the June Harper’s. However, three months ago, both yanked a small U.S.

publication, Free Inquiry, when it

reproduced four of the Danish cartoons. In another of the endlessly amusing

instances of hypocrisy that afflict the well-meaning, that issue of Free Inquiry is presently being sold in

the Indigo stores in Canada. The Montreal

Gazette found Indigo’s banning of Harper’s disturbing: “The [Spiegelman] article is only modestly provocative and well

within the bounds of reasonable discourse. That Canada’s largest bookseller

should deem it beyond the pale sends an unfortunate message. It tells the

thousands of Christians, for example, who are outraged by The Da Vinci Code that if they want that offending novel out of

circulation, they should go and burn down a few embassies. In fact, it would be

hard to name a religious or political group in Montreal that couldn’t find

something to offend them on Indigo’s shelves. Maybe they, too, will absorb the

lesson that violence trumps reason every time.”

In Jordan, editors of the two

newspapers that published the Danish cartoons were each sentenced to two months

in prison for violating a section of the country’s penal code that outlaws

publication of material likely to offend religious feelings or beliefs (in this

case, by publishing a likeness of Muhammad, a blasphemous act to many Muslims).

The hapless editors said they did not intend to offend Muslims; they published

the cartoons to criticize the Danish newspaper that originally printed them.

One of the editors was also doubtless guilty of common sense. He published an

editorial that began: “Muslims of the world, be reasonable. What brings more

prejudice against Islam—these caricatures or pictures of a hostage-taker

slashing the throat of his victim?” [Seattle

Times, cpj.org, and news24.com]

In Iran, the weekend edition of the

reformist daily newspaper Iran has

been suspended indefinitely and its editor and cartoonist arrested. The

official reason for the closure is linked to a cartoon that offended Azeris, a

Turkic ethnic group comprising about 25 percent of Iran’s 70 million people. In

the cartoon, a boy repeats the Persian word for “cockroach” in several ways

while the uncomprehending insect in front of him says “What?” in Azeri. The

cartoon apparently alludes to the difficulty of assimilation in Iran. Soon

after the publication of the cartoon, riots broke out, and in Orumiyeh, where

Azeris make up the majority, the newspaper’s office was set afire. The

cartoonist, incidentally, is Azeri. Newspaper closure is not unusual in Iran.

Between 1999 and 2004, the Khatami government severely restricted freedom of

the press, and a state censorship committee shut down 22 newspapers; another 81

were closed by court order. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has

lodged a formal protest, calling for the release of the editor and the

cartoonist. [cpj.org and asianews.it]

Fascinating

Footnote. Much of the news

retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and

related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve

deeply into cartooning topics.

COMIC STRIP WATCH

The

cross-over craze of in-jokes continues in Ric

Stromoski’s Soup to Nutz, where

Stromoski gets even with Stephen Pastis who put Stromoski in his Pearls before

Swine as a frog who couldn’t get a date. In Soup to Nutz, Pastis appeared last December as a kid with a head so

large that his football team used it to block field goals. At the time,

Stromoski knew that Pastis would skewer him, Stromoski, in Pearls later on so he just beat him to the punchline. Pastis thinks

this sort of in-jokery is something comic strip readers dote on: “The vast

majority love to see it,” he told William Weir at the Hartford Courant, “because the comics page can be kind of static

and predictable.” But, as I explained in Opus 183, my guess is that “the

vast majority” of readers don’t even make sense of Pearls’ in-group hilarities because for comprehension the jokes

require the reader to be familiar with another strip that may, or may not, be

published in the same newspaper. The sort of infantile self-indulgence that

Stromoski and Pastis (and Get Fuzzy’s Darby Conley; see Op. 183) have

become habituated to has very little to do with entertaining readers and a

whole lot to do with locker-room horseplay. Like lighting farts, it seems to

vastly amuse those for whom lighting farts represents the height of humor.

Pastis tells Weir that he plans to “crash” the world of storytelling strips,

beginning with Mary Worth. Old lady

fart jokes?

Finally, after many arduous weeks of

breathless anticipation, we have Judge

Parker being drawn by Harold

LeDoux’s successor, Eduardo Barreto, whose first daily Parker strip

appeared May 29. Barreto lives and works in a small seaside town near the place

where he was born, Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1954. His first published cartoon

feature was an sf strip that was published in 16 South American countries. In

1983, he began working for DC Comics, where he drew nearly every character. He

also did work for Marvel and Dark Horse; and he has done at least a couple

graphic novels, one of which, The Long

Haul by Anthony Johnson, I reviewed at Opus 158. He also illustrated

Ande Parks’ Union Station. His work

is crisp and clean, very A couple notable new strips have

surfaced recently. Starting last September from King Features, we have A Lawyer, A Doctor, and A Cop by Kieran Meehan. At first blush, this

effort would appear to be the Absolute Last Word in Niche Marketing. Or the

First Word, perhaps, inaugurati Also from King, a much more

inventive strip, The Pajama Diaries, by Terri Libenson. The strip purports

to be the diary (which Libenson illustrates) of Jill Kaplan, an introspective

young suburban mother “balancing her career as a freelance graphic artist with

family life and responsibilities”—she has a husband and two young daughters.

Exactly the sort of person that Libenson

THE NEW YORKER EXPERIENCE

My Rejected New Yorker Cartoons

Tim

Kreider at his website, www.thepaincomics.com, writes a good

deal of engaging prose, accompanied, occasionally, by cartoons of his own

devising. On May 3, he began his account of his New Yorker adventure with a wholly unrelated preamble about Stephen

Colbert’s now notorious presentation at the White House Press Corps Dinner.

Because I agree with him so lavishly, I quote him verbatim here, before getting

to his analysis of New Yorker humor,

which is as insightful and succinct as his characterization of Colbert’s

audience; herewith—

Those of you who have not seen or

heard about it should immediately view the video or read the transcript of

Stephen Colbert's address at http://www.crooksandliars.com/2006/04/29.html#a8104 . The speech is very funny in itself, but it's astonishing considering that it

was given in the presence of George W. Bush himself, who sat rigid and

unsmiling a few feet away at the same banquet table. Particularly notable is

the tense silence from the Washington Press Corps, apparently as squeamish

about humor as they are about truth.

It is not easy to draw a New Yorker cartoon. (Indeed, as the

title of this collage implies, I have failed to do so.) David Foster Wallace

once described them as having "an elusive sameness." The usual

subtext seems to be self-congratulation on (disguised as self-deprecation of)

New Yorkers' trendiness, superficiality, and materialism. The typical reader

response to one is a barely perceptible lifting at the corners of the mouth,

and perhaps a murmured, "Mm." They have to be clever; droll, even.

They must never actually be funny. For example, a friend of mine looked at

panel #3 here [depicting an orgy, captioned:] "What happens at the

Pulitzers, stays at the Pulitzers," and suggested that it ought to be

"Caldecotts" instead. This alteration made the cartoon exponentially

funnier—hilarious, even—but also instantly rendered it ineligible for The New Yorker. It's a tough genre. I

have spent five of the last six winters in New York City, and once a year, on

average, I get an idea that is clever enough but not too funny to be a New Yorker cartoon. This winter, in one

of the sporadic and invariably futile bursts of ambition I succumb to when I'm

up here, I finally decided to draw them all and submit them.

Footnit: I disagree only slightly, almost

not at all. I think “Caldecotts” not only makes the cartoon funnier, but it

would have improved its chances for purchase by The New Yorker by reason of its having increased the obscurity of

the allusion. For Kreider’s ensuing report on his visit to the offices of the

August weekly—definitely worth knowing—consult http://www.thepaincomics.com/weekly060503a.html,

and look around while you’re there for other evidences of his wry wit and

insight.

Quips

& Crotchets

“In

spite of the cost of living, it’s still popular.” —Kathleen Norris

“The only fool bigger than the

person who knows it all is the person who argues with him.” —Anonymous

“Only two groups of people fall for

flattery—men and women.” —More Anon

Pearl Williams, bawdy comedienne of

the 1950s and 1960s: “Definition of indecent: if it’s long enough, hard enough,

and in far enough, it’s in decent.”

Quoted in the April-May issue of Bust magazine. Well, where else?

The Reuben Weekend

The 60th Annual Convening of

the National Cartoonists Society for the Purpose of Giving Each Other Awards

“Congratulations,”

I said to Mike Luckovich, shaking

his hand warmly, “—on winning the Chester Gould Reuben.”

“Oh, you heard?” he said. “Well, I’m

not giving it back,” he quipped with a grin.

It was a historic occasion. The NCS

held its 60th convention May 26-28 in Chicago, where Chester Gould had invented Dick Tracy just about 75 years ago (it

debuted October 4, 1931), and Gould had won the Reuben, the NCS trophy for

“cartoonist of the year,” twice, in 1959 and in 1977. Only eight of the 61

Reuben winners have won twice; the other seven: Milton Caniff (1946, the first; 1971), Charles Schulz (1955, 1964), Dik

Browne (1962 for Hi and Lois;

1973 for Hagar), Pat Oliphant (1968, 1972), Jeff

MacNelly (1978 for editorial cartooning, the next year for Shoe), Bill Watterson (1986, 1988), and Gary Larson (1990, 1994). NCS devoted a certain portion of the

weekend’s festivities to celebrating Dick

Tracy’s anniversary, and my remark to Luckovich invoked these matters while

also referencing another happenstance, which shall remain thoroughly cryptic

until sometime next month, when all will be revealed. But Luckovich’s winning

the Reuben this year is historic in quite another sense. Luckovich draws

editorial cartoons for the Atlanta

Journal-Constitution, and for him, the Reuben is the other half of

cartooning’s double-crown: he won the Pulitzer a few weeks ago, his second.

This, then, is now officially the Year of Luckovich; for more about Mike, see Opus

182, where I’ve reprinted a long interview I did with him several years

ago. As far as I have been able to determine, consulting rosters of awards,

this is the first time an editorial cartoonist has won both these competitions

in the same year. The Pulitzer, although announced in the spring of 2006, is

for cartoons produced in 2005; ditto the Reuben.

The Pulitzer comes with a cash award

of $10,000; the NCS Award, with the “It is a horrible looking creation,”

said Mort Walker, creator of Beetle

Bailey and the unofficial dean of American cartoonists who presents the

award to the winner every year at the Reuben banquet. “The minute we recoiled

at the sight of it, we knew we had the design we’d been searching for,” he

continued. “It was hideous and disrespectful and honest enough that no

cartoonist would feel finky handing it to another and saying, ‘Here—take the

stupid thing. You won it by majority vote of the members who think you’re the

outstanding cartoonist of the year. You deserve this.’ It has served us well.

There has been lots of grumbling about its lack of beauty, which makes us very

proud. It fits us. So does grumbling.” I’m quoting Walker’s remarks from Craig Yoe’s antic website, www.arflovers.com, where he also supplies drawings of the statuette by Hank Ketcham, Chester Gould, Alfred Andriola, Johnny Hart, Bud Blake, and Harold Foster.

In these festering times, fraught

with worry and multicultural sensitivity, it is probably politic to mention

that none of these worthies had ever heard of Abu Ghraib, and neither had

Goldberg; if they had, they would surely never have depicted the naked men in a

pile. Up a tree, maybe, but never in a pile.

Only three other political

cartooners have won both awards, and only two of those at almost the same time: Jeff MacNelly won the Pulitzer in

1978 for cartoons done in 1977, and he won the Reuben for 1978, announced in

1979; and Pat Oliphant won the

Pulitzer in 1967 for cartoons done in 1966 and the Reuben for 1968, announced

in 1969. But only Luckovich has reaped the awards for the same year—although it

won’t seem that way when the lists are assembled. He will appear to have won

the Pulitzer for 2006 because that’s when his win was announced; the Reuben

listing, however, will give the year correctly as 2005. Herblock also won both awards, the Pulitzer in 1942, 1954, and 1979 (each for the preceding year); the

Reuben for 1956. Mike Peters won the

Pulitzer in 1981 for 1980, and the Reuben for 1991, but the Reuben was for his

comic strip, Mother Goose and Grimm, not for editorial cartooning.

The Reuben, notwithstanding the

surpassing dignity of its origins and design, is seldom awarded to an editorial

cartoonist. NCS more often honors syndicated cartoonists for newspaper comic

strips and panel cartoons than any other kind of cartoonist. Of 61 Reubens (two

were given in 1968 when the balloting produced a tie), only 7 have gone to

political cartooners. In addition to those I’ve just mentioned, the Reuben also

went to Bill Mauldin (1961) and Jim Borgman (1993). Oliphant, as I

said, won twice. Cartooning venues other than newspapers are similarly

slighted: the “cartoonist of the year” trophy has gone to a non-newspaper

cartooner only 10 times. It went twice to Mad cartoonists (Mort Drucker in

1987 and Sergio Aragones in 1996),

but only once to a magazine cartoonist (Charles

Saxon in 1980), a comic book cartoonist (Will Eisner in 1998), and to an animator (Matt Groening in 2002). It went once to “humorous sculpture” the

year the Society gave its Reuben to the man it is named after, Rube Goldberg (1967); and three times

to “humorous illustration” (Ronald

Searle, 1960; Arnold Roth, 1983; Jack Davis, 2000). One sports

cartoonist, Willard Mullin, got the

trophy (1954). All the rest of the time, the “cartoonist of the year” has been

a syndicated newspaper cartoonist, doing either a strip or a panel—44 of the 61

Reuben winners.

The “Reuben Weekend,” as it is known

among the cognoscenti, usually begins on Friday and concludes Sunday evening.

Some of the time is devoted to presentations and/or panel discussions; some of

the time is spent in mischief-making and cocktail drinking. This year, slightly

more than 200 of the Society’s 570 members attended, many bringing wives and

children, which brought the total attendance to about 400 people.

In addition to presenting the

Reuben, NCS confers “division awards,” recognizing excellence in the various

genre of cartooning. Because being nominated is nearly as distinct an honor as

winning in each division, I’m listing all the nominees here and marking the

winners with an asterisk (*) before their names: Magazine Gag Cartoons—Pat Byrnes, Gary McCoy, *Glenn McCoy; Newspaper Panel Cartoons—Mark Parisi (Off the Mark), Hilary Price (Rhymes with Orange, which is actually

published in strip format but as a single panel), *Jerry Van Amerongen (Ballard Street); Newspaper Comic Strips—Jim Borgman and Jerry Scott (Zits), Michael Fry and T Lewis (Over the Hedge), *Brooke McEldowney (9 Chickweed Lane); Advertising Illustration—*Roy Doty, Jack Pittman, Kevin Pope; Animation Feature—*Nick Park, director

“Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit,” Craig Kellman, character

design “Madagascar,” Carlos Grangel, character design “Corpse Bride”; Book Illustration—David Catrow, Laurie

Keller, *Ralph Steadman; Editorial

Cartoons—*Jim Borgman, Michael Ramirez, John Sherffius (the latter two have

both recently been “displaced” from their newspapers; Ramirez found a new home,

Sherffius is freelancing and syndicating); Greeting

Cards—Dan Collins, *Gary McCoy, Stan Makowski; Magazine Feature Illustration—Steve Brodner, *C.F. Payne, Tom

Richmond; Newspaper Illustration—Greg

Cravens, Nick Galifianakis, *Bob Rich; Television

Animation —Glen Murakami (“Teen Titans”), *David Silverman (“The

Simpsons”), Dave Wasson (“The Buzz on Maggie”); Comic Books— *Paul Chadwick (Concrete,

the Human Dilemma), Erik Larsen (Savage

Dragon), Rick Geary (various titles, usually termed “graphic novels”).

The weekend also honored Ralph Steadman, who received the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award; and Dick Locher, who produces four

editorial cartoons a week for Tribune Media Services while writing and drawing Dick Tracy. Locher received the Silver T-Square in recognition of his life-long

service to cartooning. Other nominees for the Reuben, incidentally, were: Bill Amend (comic strip Foxtrot), Dave Coverly (panel cartoon Speed

Bump), Brian Crane (comic strip Pickles), and Dan Piraro (panel cartoon Bizarro).

On Friday afternoon, presentations were made by Steve Silver, who has been named caricaturist of the year by the National Caricaturist Society and who creates character designs for animation studios (Disney’s “Kim Possible,” for instance, and Kevin Smith’s “Clerks: The Animated Series”); and Elwood Smith, a humorous illustrator whose old-timey looking cartoons appear in books, magazines, newspapers, etc. By way of demonstrating how he warms up and keeps loose for work, Silver showed a spectacular series of sketches, all displaying great energy and invention—some, just faces; others, full figures caught in the middle of some lively activity. He sketches as quickly as he can: “If I can do it quick,” he explained, “then it’s good for animators.” He uses books of old photographs and stills from movies, and he takes a sketchbook with him to the zoo and to coffee shops, where he draws whatever he sees. Typically, he uses colored pencils or markers to indicate over-all shapes, then adds the linear dimension in black ink. When but a mere broth of a lad, he found a sketchbook in his backyard and was thereby inspired to do caricatures. He got his professional start, he said, doing caricatures in a theme park, Sea World in San Diego. He sketches constantly. And he often makes his own sketchbooks: he collects a stack of different kinds of papers—watercolor paper, pebbleboard, etc.—and has them bound into booklet form at the local Kinko’s. The different paper surfaces produce slightly different effects as he draws on them. Most of the sketches Silver showed during his session can be found in his book, The Art of Silver (160 9x11-inch pages in hardcover; $40; available at www.silvertoons.com); some of the sketches appear in this vicinity, ample testimony to the liveliness of Silver’s interpretations.

Smith showed his wares, too,

beginning with some images from George

Herriman and other vintage cartooners whose styles inspired Smith; and he

also showed a few very short animations. A tribute to Will Eisner filled out the afternoon’s schedule—a short film of 10

minutes, excerpted from a longer work in progress by Jon Cooke and his brother,

plus commentary by Jules Feiffer and

yrs trly.

Saturday’s presentations were made

by another humorous illustrator, Everett

Peck, and by Dick Locher and Ralph

Steadman. Locher, celebrating Dick

Tracy’s 75th anniversary, was preceded by Jean Gould O’Connell,

the only child of Tracy’s creator, Chester

Gould, and her children, Gould’s grandchildren. They all spoke lovingly,

admiringly, about Gould as father and grandfather, not as cartoonist. When

Locher took the floor, he began with one of his well-tooled openers: “The brain

begins to function the minute you’re born and doesn’t stop until you stand up

to make a speech.” Despite the Dick Tracy anniversary, Locher talked mostly about his editorial cartooning, probably

because samples of these made a better show than pictures of the cleaver-jawed

flatfoot. Well, funnier at least. The editorial cartoonist, Locher said in

conclusion, is like a blind javelin

thrower: “he may not always hit his target but the audience stays alert.”

Steadman, after running through a

carousel of slides of his artwork, had ten minutes left and asked the assembled

multitudes if they’d like to see more. We all cheered, and so he brought out a

box of slides, which editoonist Rob

Rogers fed individually into the projector. Steadman then got carried away

with anecdotes about his career, the people he’s known and worked with

(including Hunter S. Thompson), and his dire opinions of politicians,

particularly American ones. “Cartooning is a weapon,” he said, “and I want to

use it to attack a rotten world.” He paused, looking sad. “But the world is

worse today than when I started,” he finished. He sometimes pranced around the

stage as he enacted some outlandish event, adding body English to the anecdote.

All very amusing, but by this time, he’d talked longer than we’d bargained for,

and he had to be nudged off stage. He threatened to repeat this prolix

performance that evening when accepting the Caniff Award, but we managed to

inspire him to quit by applauding when he stopped his harangue to take a

breath.

Every evening event—Friday,

Saturday, and Sunday—began with a hour or so of liquid emollient during which

numerous uninhibited conversations take place, usually at decibels above

normal, which doesn’t make them any more intelligible because everyone is

shouting. Talking with Jules Feiffer, I confirmed a theory I had nursed about

Will Eisner. During the afternoon’s tribute, Jules had mentioned the parade of

cartooners he witnessed coming and going in Eisner’s studio when he, Feiffer,

worked there from 1946 through the early 1950s. Notwithstanding the seeming

testimony of the parade, I persisted in thinking that Eisner’s pioneering

genius was not appreciated or properly understood until well after he’d

abandoned The Spirit. As art director

of the Eisner-Iger comics shop 1936-1940, Eisner had laid out stories scripted

by the shop writers, determining panel composition and narrative breakdown—the

essential drama of the tales—before turning the finishing work over to the

bullpen artists. And he also checked their work and approved it at stages all

along the way. Even at this stage in his career, Eisner was passionately

intrigued by the comics form and experimented with it, continually plumbing its

potential. His experiments influenced the way many of his crew thought about

making comic books, and many of those he influenced—Jack Kirby, for instance, Joe

Kubert, Bob Powell and others of the pioneers who came through the

Eisner-Iger shop—went on to shape the medium in their own ways, ways that had

been, in turn, formed by Eisner. At this point, Eisner’s influence, while

considerable, was subtle, even insidious.

But his subsequent work on The Spirit, 1940-1952, which we now see

as so seminal, was not widely appreciated by comic book artists during the

initial run of the feature. During its publication life, The Spirit was not all that visible: it appeared in newspapers and

took the form of a comic book, but it wasn’t a comic book on the newsstands

where other comic book artists might see it. And even when it entered its

reprint phase with Police Comics in

September 1942, well into its third year, The

Spirit was merely a backup feature. (By the same token, because in Sunday

editions of newspapers it took the form of a comic book, The Spirit was not a newspaper comic strip, so strip cartoonists

may well have overlooked it. In fact, many of them disdained comic books.) My

feeling is that it wasn’t until The

Spirit started getting its own reprint titles in the 1960s that it achieved

visibility enough to attract the attention and admiration of any considerable

number of comic book artists. By the time Warren launched its reprint series in

1974, The Spirit—and Eisner—had a

cult following among a new generation of comic book creators, and it was then that

Eisner’s graphic storytelling genius began to be appreciated. His influence on

comic book making, then, had its second major impact—the impact we all

attribute to The Spirit—two

generations of comic book artists later, so to speak, not so much during the

years that Eisner was actually producing the feature. I blurted out to Feiffer

as much of this theory as I could at the top of my lungs, and he seemed to

agree. I think. But, as I said, our conversation took place during a noisy

cocktail hour, so I might have been imagining most of his part in it.

Later, after the Reuben dinner, I

ran into Darrin “Candorville” Bell at another liquid soiree and complimented

him on the bite of his satire, particularly the strips that reveal the

hypocrisy of our so-called government. Bell thanked me for the compliment but

said it was easy to do satire of that sort: all you have to do is quote the

Bush League verbatim, and the hypocrisy leaps out at you.

Sunday afternoon was devoted to

baseball in the form of a Cubs game to which interested parties had purchased

tickets earlier. I didn’t. I’ve never been able to understand sporting events

the culminating activity of which invariably involves people showering

together. Doesn’t seem all that competitive. While cartooners gasped at the

Cubs near win, I and Jeremy Lambros (your friendly Rancid Raves webmaster) and

cartoonist historian Ed Black drove fifty miles to Woodstock, where Gould lived

since the mid-1930s. We celebrated his strip’s 75 years by visiting the Dick Tracy Museum. Occupying only two

or three rooms in the town’s historic court house (wherein the jail serves as a

restaurant downstairs), the Museum is jammed with memorabilia that illustrate

Gould’s life and career. On display are several of the reputed 60 comic strips

he concocted and tried to sell between 1921, when he arrived in Chicago from

his home state, Oklahoma, and the summer of 1931, when Joe Patterson of the

Tribune-News Syndicate finally bought one, namely, Plainclothes Tracy, which Patterson promptly renamed. “They call

cops ‘dicks,’” he explained; “call him Dick Tracy.” For the whole story of

Gould’s ca The weekend concluded with a buffet dinner and the now traditional “roast” of some well-regarded member of the club. This tradition began about five years ago when Family Circus’ Bil Keane, who had been master of ceremonies for decades, retired from the position. Keane was known for the wry insulting wit of his introductions, so when he retired, his confreres took the opportunity to get back at him by staging a “roast,” the first, as it has turned out, of a succession that now grows tiresome. Mell Lazarus has been roasted; ditto Sergio Aragones. This year, it was Cathy Guisewite’s turn. She was the first female target, and her self-proclaimed lack of drawing talent in the strip Cathy made her particularly ripe for ridicule. Bil Keane initiated the festivities with a few of his well-turned comments. “Before I begin,” he began, ignoring the ludicrousness of this remark, then going on to recollect a recently run marathon in his hometown, Phoenix. “I wondered,” he said, “what would make 20,000 people run 26 miles in the hot Arizona sun. Then,” he continued, “I saw behind them, Ralph Steadman, making a speech.” Having tagged Steadman, Keane then turned to the evening’s victim, issuing another of his dry deadpan bromides: “Of all the women ... cartoonists ... currently making a living ... at the profession,” he said, drawing out his pronouncement by prolonging the pauses between words, “Cathy Guisewite ... is ... one.” He then launched into one of his patented double-talk routines, which usually sends the room into gales of well concealed laughter. And it did again. Keane was followed by Barbara Dale, Lynn Johnston, Mike Luckovich, who did a very funny and insightful analysis of the Cathy comedy formula, and Mell Lazarus, who did a particularly unfunny reading from what he represented as Guisewite’s diary that recorded her lusting after various members of the Society. So unfunny was it that Lazarus had to supply his own laugh track, snickering throughout in what was probably intended as some sort of satirical embellishment but which actually made no sense whatsoever. Finally, Guisewite took to the podium herself and let her tormentors have a dose of their own medicine. And she was better than any of them. All of the viciousness of the individual presentations was typically undercut in each presenter’s closing comments, which inevitably extolled the high virtue and supreme humanity of the target. The roast of Bil Keane was wonderfully appropriate; as time expires, the succeeding roasts seem lamer and lamer. And now, a collection of my photographs and caricatures and notes for your delection.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis

Miller adv.

According

to Harper’s, fifteen—that’s

15—Harlequin novels published last year featured love between a Western woman

and an Arab sheik. Have you ever noticed that all bodice-ripper novels involve

a woman having to choose between a respectable, stand-up guy in a suit and a

social outcast with a hairy chest? And herewith, we have revealed the secret

appeal of the genre to women readers: the choice is between social decorum and

lustful self-indulgence, and women, apparently, desire both. They want both

domestic safety and sexual excitement: they want to satisfy their rampaging

sexual appetites without giving up the security of a good home and a dependable

provider. The struggle between these two seemingly conflicting impulses informs

the plots of virtually every bodice-ripper out there. So now you know all about

the feminine mystique.

Turns out that the penny is not the

only extravagance of the U.S. Treasury. It costs 1.23 cents to manufacture

pennies; and it costs 5.73 cents to produce a nickle. No wonder the national

deficit is spiraling out of control. Too bad: we can’t blame the Republican

spending spree for it anymore.

BOOK MARQUEE

The

second of Craig Yoe’s Arf books, Arf Museum, is out (120 giant 9x12-inch pages in paperback;

$19.95), and it is as delightful a romp through the rare and wonderful as the

first volume. Among the seldom-if-ever-seen specimens: a cartoon by Hugh Hefner, one of the few he

published in his own magazine (very early on, naturally); Reamer Keller cuties, which make me wonder why Playboy never published any Keller; Bettie Page and some gorillas;

Picasso’s comics; various Rube Goldberg inventions;

and Art Young cartoons, some from

his celebrated visits to Hell. Many of these are taken from Yoe’s own

collection of comics rarities, holdings that make me feverish with envy. Yoe

also publishes here, for the first and only time (a most wondrous find), ten

full-color paintings of the Yellow Kid by his creator, Richard F. Outcault, who produced them as cover art for the Yellow Kid magazine, a periodical that,

alas, saw only one issue, which, apparently, was enough to prove it could not

succeed even with the wildly popular Yellow Kid as a loss leader. The paintings,

you may remember, were discovered some few years ago in the cartoonery archives

of Syracuse University, where Yoe occasionally serves as an adjunct professor.

Now—only in Arf Museum—we can all see

what only a very few have hitherto beheld. Other manic works of art appear

herein—the hilariously inventive morphing exercises of Punch cartoonist Charles

Bennett in the 1860s, a comic book tale about tattoos by Stan Lee, drawn by Fred Kida, a nearly naked Dan

DeCarlo cutie, a two-page strip by Mort

Walker recording the life-altering experience Roy Lichtenstein had meeting

with the National Cartoonists Society (including Walker’s caricatures of Rube Goldberg, Bob Dunn, Russell Patterson and other NCS headliners—yes, caricatures! and in Walker’s usual style, too), a

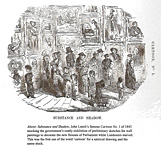

generous smattering of Yoe’s own brand of cartooning lunacy, and the Punch cartoon that gave the word cartoon its modern meaning. It’s a

drawing by John Leech. Entitled

“Cartoon No. 1,” it was the first in a series of “cartoons”—meaning, “preliminary

drawing” for a mural, painting, or fresco—Punch offered for consideration in a national competition to select patriotic

decor for the halls of the newly completed Houses of Parliament in London.

Leech’s picture was published in Punch for July 15, Speaking of monumental tomes on

cartooning, the best book about the life of a syndicated cartoonist is back in

print—namely, Mort Walker’s Backstage at the Strips. Published

initially in 1975, the book was almost immediately lost in the shuffle as its

publisher, Mason/Charter, went bankrupt. The volume, in both hardcover and

paperback, has been scarce ever since. But the paperback version, with a new

cover but otherwise an exact copy of the original, is now available again,

thanks to on demand publishing, through Amazon.com for about $25.

REPRINTZ

The

sequel to the Doonesbury book about

B.D.’s loss of leg will be out in August. The initial volume, The Long Road Home: One Step at a Time (96

6x8-inch pages in paperback, $9.95), appeared last summer with all royalties

from sales going to Fisher House Foundation, which provides temporary housing

near hospitals for the families of soldiers receiving treatment. B.D. lost his

leg in April 2004, and the book publishes all the subsequent strips tracing his

ordeal and rehabilitation until the following Christmas, when B.D. returns home

to his wife, Boopsie, and his daughter, Sam. During these seven months,

cartoonist Garry Trudeau carried on

in his usual fashion in the strip, deflating political balloons hither and yon,

but he returned periodically to a much more serious purpose, showing us “B.D.’s

survival of first-response triage, evacuation to Landstuhl’s surgeon-rich

environment, and visits by numerous morale-boosting celebs, both red and blue

in hue.” The book’s backcover blurb continues, telling us that B.D., former

football hero and coach, is “awed by morphine, take-no-guff nurses, his fellow

amps, and his family.” Trudeau researched this story at Walter Reed Army

Medical Center, where he visited wounded soldiers and amputees, hoping to tell

their story in as honest and unflinching a way as possible but preserving, too,

the warriors’ sense of humor, dark as it often is. “Whether you think we belong

in Iraq or not,” Trudeau has said, “we can’t tune it out; we have to remain

mindful of the terrible losses that individual soldiers are suffering in our name.”

In the Introduction, Senator John McCain says Trudeau tells B.D.’s story well:

“Biting but never cynical, and often wickedly funny, these comic strips will

make you laugh, reflect and—in the end—understand.” The book begins with the

strips recording B.D.’s falling unconscious after being hit; it ends at

Christmas, when Sam gives him a seemingly inappropriate gift—rock climbing

shoes. “So I’m an optimist,” the girl says, “—sue me.” A tidy tome, it runs one

four-panel strip, with extra-large panels, to every page. My only complaint

about the book that rehearses this otherwise humane and caring story is that

none of the strips are dated; historians at some future time will miss this

vital data. But the story, even without

dates, will endure as a testament to human capacities, to Trudeau’s heart and

creative sensibilities, and to the potential of the comic strip to touch us

all, profoundly, meaningfully. The sequel is entitled The War Within: One More Step at a Time. As with its predecessor,

proceeds will go to Fisher House.

And while we’re on subjects

Trudeavian, here’s The Big Book of Zonker (152 9x11-inch pages in paperback with French flaps; $16.95), which

purports to be the entire history of the world’s “greatest living slacker,”

strip by strip. It begins with Zonker Harris’ unlikely appearance in the huddle

of B.D.’s football team on September 21, 1971, just a year after the strip was

syndicated by Universal Press, debuting October 26 in a mere 28 newspapers.

(It’s now in more than 1,400.) But you can’t tell from the book when Zonker

first appeared: as always, no strips are dated. The volume is, however, divided

into sections that are, presumably, chronological, giving Zonker a biography in

much the same way as the 2001 publication of Action Figure gave us the life and times of Uncle Duke. Although

Zonker has always represented “high” aspirations, he has been resolute in

avoiding anything approaching actual work. After being thrust unprepared into

the world with only nine undergraduate years to sustain him, Zonker served as a

“spin doctor” during Duke’s 2000 presidential bid, then became a professional

tanner and, finally, a skilled nanny. And it’s all unforgettably here.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE

Frank Miller’s story in Batman

& Robin: The Boy Wonder continues at a painfully slow pace. In No. 4,

Vicki Vale is undergoing surgery in the hospital after her encounter with bad

guys and bad vibes, and Batman, persisting in his pathological plan to make

Dick Grayson a worthy sidekick by making him as twisted as he, Bruce Wayne, is,

takes the kid into the Batcave. And here is the epic moment: entering the

subterranean environs, we open a six-page “gatefold” that, one turned page in

succession after another, reveals as it unfolds the vastness of the cave and

its contents in a panorama 36 inches wide. Stunning exploitation of the

resources of the medium, Frank.

All the four-color excitement over

last weekend was generated by a story in the New York Times on May 27 about the “return” of Batwoman to the DC

Universe as a “lipstick lesbian.” The Batwoman persona returns, but the crime

fighter is not secretly Kathy Kane, the original Batwoman who was introduced in Detective Comics No. 233 (July 1956),

hung around Batman longingly for a few years, and was eventually killed off by

the League of Assassins in Detective

Comics No. 485 (September 1979). The original Bat-girl was Kathy Kane’s

niece, and the two of them seemed to have some romantic inclinations towards

Batman/Bruce Wayne and Robin/Dick Grayson, but nothing other than a tepid

variety of adolescent flirting transpired: in those distant days, comic book

heroes didn’t have sex lives in which sex was a factor. They were differently

gendered but not sexed up at all. The “new” Batwoman is Kate Kane, who, we’ll

doubtless discover when she debuts in the 11th issue of the weekly

series 52 sometime in July, took over guarding Gotham while Bruce

Wayne was off sulking after the conclusion of the Infinite Crisis mini-series.

DC’s executive editor Dan Didio was

interviewed on Newsarama, where he attempted to explain that having a gay

Batwoman was not merely a publicity stunt but part of an on-going effort to

“reinvigorate the Batman franchise,” which he felt was somewhat stale because

all the characters “were coming from the same place, the same sense of origin.”

Didio wants to infuse in each of the Batman characters such a distinct “sense

of individuality” that readers won’t be able “to pickup a Batman book, a

Nightwing book, and a Robin book and feel like they’re reading the same story.

These are three different people with three different perspectives, with three

different stories taking place.” Each should have his or her own individual

“tonality,” he said. “That’s what we want to do with Batwoman right now: she

should have her own tonality, her own feel so that her character and her story

has something that’s unique to itself, and not just another Batman story with a

woman.”

This all sounds admirable enough,

but I’m not sure that making the new Batwoman a lesbian is the only way to accomplish

the goal. Didio points to other post-Crisis characters, many of whom are ethnic

or racial minorities. “We wanted to have a DC Universe that was more

reflective, not only of our readership, but of society as a whole,” he

explained. Moreover, Batwoman being gay gives her stories “a different point of

view, a different perspective on the DC Universe that other characters might

not have.” Didio’s interviewer rather logically pointed out that one’s sexual

orientation is not, necessarily, a determining factor in how that individual

might fight crime: “Heterosexuality as a character trait has been largely

ignored with Batman, yet it’s not the same when you’re talking about a gay

character.” Didio handily dodged the illogic involved in his plan by suggesting

that a lesbian character’s keeping her sexual preference secret from her family

would have an effect on her personality. Sexuality is not the theme of

Batwoman’s stories, Didio hastened to say, but her different sexual orientation

will provide writers with the opportunity to play her private life against her

heroic life, presumably in some way different than how Robin’s private life

plays against his heroic life. Well, I suppose. But I sometimes wonder if the

superheroing business—that is, writing and drawing superhero comic books—hasn’t

run away with its own ambitions a bit. The ambition, I assume, is to produce

stories about heroic persons who have rounded, individual personalities and

lives—who are not, in other words, the cardboard cutouts that stood in for

people in the old timey funnybooks. Peter Parker’s early nerdishness clearly

gave Spider-Man a dimension that, say, Superman didn’t have; and that was all

to the good. Peter Parker proved something that the conjurers of lipstick

lesbianism for the new Batwoman haven’t, apparently, learned. It’s probably

sacrilegious to mention it, but the ethnic or racial or sexual nature of a

character is are not the only basis upon which individuality can be built. If

you want rounded, individualized personalities for your superheroes, you don’t

have go to obvious stereotypes to get them. You could go to real people, for

instance. Admittedly, relying upon obvious ethnic and racial and sexual origins

is a shorter and faster way to get where you hope you’re going, but it’s not

quite as authentic. Individual identity is rooted in something more complex

than ethnicity, race, or sex, and to choose those as keys to character is to

reveal the poverty of your imagination.

I wasn’t sure what a “lipstick

lesbian” is, so I googled that and came up with a page in belladonna.org that

begins: “If you put ‘Lipstick Lesbian’ into a search engine, you’ll get a whole

bunch of porno sites for men.” Well, no, actually—what I got was this

belladonna.org at the very top of the Google list. But the website’s opening

gambit prompted a wild speculation or two, which I’ll get to anon. A “lipstick

lesbian,” I learned, is a feminine woman who loves other feminine women—as

distinct from, say, a “femme” who is a feminine woman who loves masculine women.

“You’re a lipstick lesbian if —you derive a sense of power from towering over

people when you wear high heels, you think of your makeup as warpaint, you

think that ‘feminine feminist’ is not an oxymoron but a redundancy, you can do

anything a man can do (backwards and in high heels), and you think Adam was a

rough draft.” So how will this play out in the Batsaga?

Didio said “there’s history between

Bruce Wayne and Kate Kane from before she put on the costume.” Belladonna says,

“When we go to gay bars, no one believes that we belong there. Cautious women assume that we’re straight

women looking for kicks, and unfortunately, there are a lot of those out there,

preying on unsuspecting lesbians.” Moreover, she says, “When men find out we’re

lesbians, they want to watch.” Then there was that business about a “lipstick

lesbian” search turning up porno sites for men. So what sort of relationship

did Bruce and Kate have before she donned her skin-tight costume and knee-high

leather boots? Is the secret plan for a gay Batwoman intended to appeal,

subliminally, to male fantasies about witnessing fights between women?

Or is the whole thing just a

publicity stunt? If so, it surely worked. And it didn’t hurt the publicity any

that GeeDubya chose as his topic for his Saturday, June 3, radio broadcast his

intention to try, again, to persuade Congress to adopt a Constitutional

amendment prohibiting marriage between persons of the same sex.

ALEX TOTH, STYLIST SUPREME, DIES AT HIS

DRAWINGBOARD

Alex

Toth, whose command of expressive simplicity in drawing and visual storytelling

inspired generations of cartoonists, died at 7 a.m., May 27. According to his

son Eric, Toth was at his table, drawing or writing, at the time; he was 78

years old. Those who knew he was ill in recent weeks sent in good wishes, about

twenty mail bags of them. John Hitchcock, writing at www.tothfans.com, the Toth fan forum, said, “Those twenty bags of letters and cards was a really

beautiful thing for Alex. Not only was he shocked, but I think he then knew how

much he was loved by his fans and that his work will live forever.”

Born in New York City in 1928, Toth,

an only child, started amusing himself at the age of three by doodling. He

attended the High School of Industrial Arts, and while still in school began

selling two- and three-page filler stories and spot illos to Steve Douglas at

Famous Funnies for Heroic Comics. In

1947, he went to work at the All American division of National Periodicals (now

DC Comics), where he stayed, more-or-less, until the mid-1950s, when he started

doing comic book adaptations of cowboy movies and tv series for

Dell-Western—Roy Rogers, Rex Allen, Zorro, “Sugarfoot,” “77 Sunset Strip,” “Sea

Hunt,” “The FBI Story,” and others.

At National, Toth did the usual

array of superhero stories, but I first became aware of his illustrative elan

in stories about the frontier vigilante do-gooder, Johnny Thunder. I didn’t

know, at the time, that the artist was Toth, but I loved the character’s

costume and his Lincolnesque visage, vintage Toth of the period. By the time he

was doing cowboy comics at Dell-Western, Toth had come under the spell of

Milton Caniff, Frank Robbins, and Noel Sickles, who, Toth was surprised to

learn, had been Caniff’s inspiration. Henceforth, Sickles was Toth’s idol.

In the 1960s, Toth moved to Southern

California and was soon working in animation, doing character design, chiefly,

but occasionally returning to do a comic book story for DC or for Warren’s

black-and-white magazines. By this time, he had virtually perfected the purity

of line that is the legendary Toth.

Toth was not just a master of

black-and-white illustration: he was also the indisputable champion of telling

simplicity in drawing. As his style matured, it simplified. And with every

simplification, his work became more and more refined until it achieved the

absolute distillation of visual storytelling. In short, there is an exquisite

purity in the mature Toth artwork, a purity of spirit and expression that

serenades the soul of the beholder.

Toth understood exactly what he was

about. He knew what makes music in visual art. Writing about Roy Crane and his

simple but telling renditions in the classic Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy, Toth quoted the maestro violinist Isaac Stern: “Make it so simple you can’t

cheat!”

Indeed.

There isn’t a fudged line in Toth’s

best work. And most of his work is the best.

Once Toth said: “For the first half

of my career I was concerned with discovering as many things as possible to put

into my stories—rendering, texture, detail. For the second half of my career, I

have worked as hard as I could to leave out all those things.” At first, he

said, “You’re learning, you’re reaching out for all kinds of things to put into

your work ... to enrich it. ... It’s only after you’ve reached a certain age or

maturity that suddenly you start to look at it in a different way, and you say,

There’s too much going on in there that doesn’t need to be there. Now, how do

you leave out the right thing—that’s the secret of it.”

With this kind of artwork, the

reader-observer “has more fun with it,” Toth believed, “because when you do

come upon a simple piece of work, your eye draws in all the rest of it that

isn’t there. You’re participating, and this is a kick that we all have. I have

it to this day.”

He invoked Crane’s Wash Tubbs again: “Now that man draws so

simply that you can count the lines. It’s all that stuff that he leaves out

that he lets you participate in it. It’s beautiful, it’s absolutely gorgeous

artwork—and it’s a lot of fun. If your work is too rich,” Toth went on, “if

you’re socking in all of this gorgeous technique panel after panel, you bore

the hell out of your reader. You’ve got to let him rest once in a while, back

off and participate by drawing in things that he doesn’t see there in black and

white.”

And if you want more Toth, there’s

more available. Kitchen Sink Press once brought forth a genial scrapbook-memoir

of Tothwork, called (with apt simplicity) Alex

Toth ($12.95). Assembled by Toth’s long-time admirer Manuel Auad (who

subsequently has published several Tothbooks), this 144-page volume collects a

good deal of fugitive and rare Toth—one-pagers for car magazines, model sheets

for Hanna-Barbera, pin-ups (Black Canary, Johnny Thunder, the Fox), partial

storyboards and fragments of comic book stories, sketches and doodles. And

essays.

The book includes only two complete

stories of any length—“Unconquered,” the true story of a Czech patriot, and

“Air Power,” a translation into static visuals of a Walter Cronkite “You Are

There” television segment on the history of aviation. In both, Toth is

illustrating someone else’s script, but we have his interpretations to savor.

In two issues of Adventure Comics in 1972 (nos. 418 and

419), Toth interpreted someone else’s Black Canary story. Close-ups so tight

that only fragments of pictures to tell the tale (and they did), wild angles

that focused attention on the telling details, layouts stretched to serve story

needs. Shadows, simple linework, fast action. Two treasured issues.

To those who have admired Toth’s

work for decades (as I have), it comes as no surprise that he is as eloquent in

words as he is with pictures, and this book gives us a generous sampling of his

prose. He writes with perception and feeling about the idols who inspired him—

cartoonists Noel Sickles, Milton Caniff, Roy Crane, and Frank Robbins, and

illustrators Robert Fawcett and Albert Dorne. And in discussing Sickles, a huge

talent who gave his life to exploring graphic art instead of earning a living,

Toth recognized himself: “Throughout his professional career, Noel was restless

of soul, mind, spirit and talent while on his year-by-year search for new,

fresh targets. ... One pays the price for that preoccupation, that bid of

R&D or R&R away from cash-’n’-carry production woes. One satisfies

oneself with less, monetarily and materially, enjoying another reward beyond

price, that of regenerating excitement and passion in one’s work, in new,

better, expressions of oneself within its framework.”

Ditto Toth.

For admirers of Toth, his 1975

creation of an Errol Flynn-like swashbuckler named Jesse Bravo in a too-short

series for Warren deftly dubbed “Bravo for Adventure” is the ultimate Toth. By

then, Toth’s line was spare and expressive, his solid blacks dramatic and

vital, and his storytelling masterful—particularly in the suicide sequence of

the not-all-bad bad guy in which Toth yokes layout to timing with dramatic

impact. Moreover, the character and the 1930s milieu and the stories seemed to

express what Toth believed adventure tales should be. This, I think, is his

personal creation, done to satisfy his soul rather than to line his pocketbook.

We learn more about Bravo in the KSP

book. In an essay at the end, Toth tells the story of the series’ arduous

creation while his wife was in critical condition in the hospital. Distracted

by his wife’s illness, Toth produced the Bravo series while “totally

disoriented,” he says— drawing and writing straight ahead (as the animators

say), a page at a time. And yet he produced a masterpiece.

Toth’s line is purer in its

black-and-white state than Frank Miller’s in Miller’s now classic Sin City

books. And Toth’s milieu is sweeter. Miller’s world stinks of brutality; Toth’s

smells of heroism.

In the 1990s, Toth looked at the

current crop of comic books and saw “hateful garbage in its intent and

conception. Dehumanized, dehumanizing gore, offal. I see it, hear it, in our

disgustingly nasty, ugly, movies and TV, based on attitudes reeking with bile

and contempt—every character more detestable than the other. All the media are

debased by this!”

We miss Bravo and the silvery

laughter of adventuring for the fun of it.

Regrettably, little of Bravo is in

evidence in the KSP book; the whole of him was once collected by Dragon Lady

Press in 1986 and dedicated, by Toth, to his wife, who, by then, had died.

Why no more Bravo? Toth explains

that, too, in another essay. But that’s for you to find for yourself.

And if you do, you’ll be treated to

a trove of Toth delights elsewhere in the book—visual tricks, dra Footnit: Some of the foregoing first appeared in my Comicopia column in The Comics Journal, No. 185 (March 1996). At www.arflovers.com, Craig Yoe supplies a short but

heartfelt appreciation of Toth; and he also announces the next Tothbook, The Alex Toth Doodle Book, due in

bookstores soon, but not, alas, soon enough—never soon enough.

BUSHWHACKING AND THE CONTINUING THREAT

TO OUR WAY OF LIFE

The

Bush League, in the person of George WMD Bush, has attached “signing

statements” to more than 750 pieces of legislation passed by Congress and

signed into law by GeeDubya hisownself. Other presidents have issued “signing

statements” when signing legislation into law, but, according to U.S. News and World Report (May 29),

Georgie’s “record far outstrips that of any other president.” A “signing

statement,” in effect, states that the Chief Executive may, at his own

discretion, choose not to execute parts of the law he just signed into

being—for one reason or another, national security, say. The philosophical

underpinning of the GeeDubya “signing statement” is the so-called “unitary

executive theory” that holds “that the president is solely in charge of the

executive branch” and that, in the preservation of separation of powers,

“Congress can’t tell him how to carry out his executive functions.” The

“signing statement” philosophy if not the unitary executive theory itself seems

to fly in the face of Article II of the U.S. Constitution, Section 3 of which

plainly states that the President “shall take care that the laws be faithfully

executed.” The Constitution says absolutely nothing about whether the president

gets to choose which laws he executes. The Constitution also says absolutely

nothing about separation of powers: that notion underlies the structure of our

government, but it ain’t an article in the Constitution. So what the “unitary

executive theory” does is create a pseudo-intellectual smoke screen for the

president’s breaking of the law by flauting of the Constitution. No wonder

GeeDubya never vetoes anything Congress sends his way: with a “signing

statement,” he just vetoes by line-item whichever parts of the law he doesn’t

like. Line-item veto, by the way, was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme

Court. Meanwhile, the Bush League is re-constituting the presidency as a

monarchy.

From Editor & Publisher: Attorney General Alberto Gonzales said

Sunday, May 21, that he believes journalists can be prosecuted for publishing

classified information, citing an obligation to national security. So the

reporter responsible for the New York

Times publishing the story about illegal wiretapping by the NSA—that

reporter is likewise doing something illegal? Said Gonzales: “There are some

statutes on the book which, if you read the language carefully, would seem to

indicate that that is a possibility.” When it comes to “reading language

carefully”—and deploying it, too—Gonzales and the other Bush Leaguers are

expert without peer. For example: When Condoleezza Rice says it is not the

policy of the United States to torture its prisoners, she seems to be saying we

don’t torture. But that’s not what she actually is saying. She is saying,

merely, that torture is not a POLICY. True. But she doesn’t

say we’re not doing it. In fact, she rather pointedly (once you know how to

read the language as carefully as she uses it) doesn’t say anything at all

about whether we actually torture detainees. In fact, we do torture them even

though we have a policy that we don’t. This rhetorical posture permits the Bush

League to go right on, blithely torturing helpless prisoners, while all the

time stoutly maintaining—with the conviction that only truth-tellers can

sustain—that we have a policy against torture. We clearly

do have just such a policy. They never mention, of course, that they ignore

that policy at whim, just as George W. (“Whopper”) Bush might ignore some

provision of a law he doesn’t like.

The deterioration of language, the growing disconnect

between words and their meanings, is not confined to the political realm.

Catherine Callaway just came on my tv and said: “Good afternoon, everyone—it’s

good to see you here at CNN Headline News.”

She can see me? From the glowing screen in

that box in the livingroom?

Metaphors be with you.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

||||||||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |