|

|||

|

Opus 184:

Opus 184 (May 22, 2006). I’m saving the Really Big News until

the end of this introductory paragraph, kimo sabe, mentioning here at the onset

only that our feature this time is a review of the new comic strip reprint

tome, Candorville: Thank God for Culture

Clash, coupled to a short history of the strip and its creator, Darrin Bell, who first emerged on the

national stage as a real trouble-maker. We also take a look at Art Spiegelman’s examination of the

Danish Dozen in the June Harper’s and

review some comic books. Here’s what’s here in order: NOUS R US— A franchise of Dagwood Sandwich Shops is launched, but John Marshall, who draws the strip that

inspired the shops, remains anonymous; Playboy says good-bye to Eldon Dedini; MORE DANISH AGAIN— Spiegelman in Harper’s, Ted Rall in Global Journalist,

and no cartoons of Muhammad in the NCS Reuben program booklet; BOOK MARQUEE— High Hat online, Bob

Staake’s latest diatribe and a stunning book, which leads to: UGLY ART vs. BAD ART—A history of bad

art from Thurber to Trudeau and how it differs from ugly art; CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST— Da Vinci

debunked; REPRINT— Candorville and Darrin Bell’s controversial editoon in September 2001; FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE— Reviews of issues

of American Virgin, Next Wave, and Truth, Justin and the American Way and Liberality for All; BUSHWHACKING— Stephen Colbert’s assault

on GeeDubya’s sensitivities and a new Dr. Seuss ditty. The Really Big News is that I’ve finished Phase One of revising the

Milton Caniff biography that has been diverting me for the last year. It took

my five years to write the first version, which, at 900-plus pages in

typescript, was too long for most publishers to consider. Phase One involved

reducing the book by almost 40 percent, which phase is now, as of two weeks

ago, complete. Phase Two, a final edit for polishing and catching typos and for

selecting and captioning illustrations, is now underway; it’ll be completed by

the end of June, at which point, you can expect another celebration here. Hoist

one for the ol’ Harv. And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the

“Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print

off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure

while enthroned. Without further adieu—

Hear Ye, Hare Ye

Subscribers Notice: A Pointless

Exercise

We

are updating the way we send the Rabbit Habit alert because spam catchers

filter us out. You should have received an e-mail asking you to confirm your

e-mail address. Responding to this will help us build our new list and provide

better, swifter service. Of course, if you’re reading this, you’ve already done

that. And if you haven’t done that, you aren’t likely to be reading this.

Pointless exercise, like I said. Sigh.

WE

ERRED

Correcting the Malfeasances of the Past

Now

would be the best time to re-visit Opus 183, our most recent, in order to make

some sense of my diatribe about Stephen

Pastis, Darby Conley, Pearls before

Swine, and Get Fuzzy. We used the wrong group of strips to

illustrate the rant, and so it probably didn’t make sense. Probably, I suppose,

no one noticed because so little of this picayune prose actually makes sense.

But for those who were puzzled by the Get

Fuzzy strips that seemed to have nothing to do with the accompanying

tirade, you were right. We’re corrected that: now, the strips that should have

been there, are there. So take another look.

Not content with the sin of

omission, I also committed one. Last time I said that I’d just received the

most recent issue of Inkspot, the

magazine of the Australian Cartoonists’ Association, and I said something cute

about it’s being the “Autumn” issue, implying that their most “recent” issue

was, actually, ahead of the game somewhat. Ho, ho—the joke’s on me. The reason

it’s the “Autumn” issue is that, Down Under, the season is, at present, autumn;

when it’s autumn here, it’ll be spring there.

NOUS R US

All the news that gives us fits.

In

a passel of reviews of the animated film version of H.A. and Margret Rey’s Curious George, which some reviewers

dislike intensely because it tries to up-date the classic, Peter Hartlaub of

the San Francisco Chronicle, writes, with a perfectly straight face: “There

is no nudity in ‘Curious George.’” Presumably, he is reassuring concerned

parents, but I venture to guess, without having seen the movie, that George is

as naked in the movie as he is in the books. He’s a monkey. No clothing. Ergo,

naked.

From

an Editor & Publisher round-up:

Lynn Johnston and her comic strip dog, Farley in her strip, For Better or For Worse, received a

Special Award from the Purina Animal Hall of Fame for “chronicling the bond

between people and their pets.” ... The first in a chain of Dagwood Sandwich Shops will open in

June in Palm Harbor, Florida. An obvious marketing ploy whose time,

surprisingly, has taken a generation to arrive, the shops were conceived by

Dean Young, who, saith E&P,

produces Blondie with Denis LeBrun; but LeBrun retired from

the strip last summer, and since then, the only signature on the strip has been

Young’s, who, apparently, doesn’t deign to recognize the artwork done by John Marshall, who inherited LeBrun’s

chair. In fact, I have it on impeccable authority that Young specified in the

search for LeBrun’s replacement that whoever it was should not expect to get to

sign the strip. So the imposture continues, with Young pretending to be the

sole author of the classic strip he inherited from his father, Blondie’s creator. ... An animated short

by Pulitzer-winning editoonist Ann

Telnaes will be part of the forthcoming “Tomorrowland: CalArts in Moving Pictures”

show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, May 25-August 13. The

Telnaes short will be shown June 18 & 19. ... According to the latest

statistically meaningless straw poll taken at Doonesbury.com, of 15,573

respondents, 79% said GeeDubya is the worst president ever; surprisingly, of

the 319 voters who said they love Georgie, 55% called him the worst president;

and of the 1,499 who said they can take him or leave him, 56% said he was the

worst.

In its June issue, Playboy takes a moment—a half-page in

the “After Hours” section—to “bid farewell to a master cartoonist,”Eldon Dedini, reprinting three of his

cartoons and a short prose remembrance: “The Playboy family has lost a beloved member ... who painted nearly

1,000 cartoons for this magazine. ... ‘Eldon’s world was one of light and

music,’ recalls Michelle Urry, Playboy’s Cartoon Editor. ‘He drew on

both in his work. His art was gentle and good-natured.’ His watercolors—images

of satyrs and nymphs, spoofs of Japanese pillow books and Sunday funnies—are

unmistakable and ubiquitous; Playboy has run a Dedini in almost every issue since 1960. His vision of a bucolic

paradise populated by sexually liberated mythological characters became a part

of the magazine’s identity. Eldon will be deeply missed.” That it took until

the June issue to eulogize Dedini’s achievement is an indication of the lead

time between the preparation and the publication of the magazine: Dedini died

in January. The June issue carries another Dedini cartoon inside, but the perpetual

Dedini has been missing from Playboy for at least two previous issues, April and May. I wonder how extensive their

inventory of unpublished Dedini cartoons is. Here’s hoping we find out—that

they publish them all, eventually.

Fascinating

Footnote. Much of the news

retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and

related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve

deeply into cartooning topics.

MORE DANISH AGAIN

Those

of the public prints with a long lag between events and the publication of

confabulation about them are now coming along like so many sanitation

engineers, picking up the offal strewn along the journalistic main street after

the hysterical parade of the Danish Dozen has long since passed. At least one

of them, Harper’s, in its June issue,

offers the best discussion I’ve seen yet—apart from those we committed here,

that is. It’s sober, reflective, and informative, as you might expect of a

periodical that’s had plenty of time to assemble facts and to ponder them. The

article, by cartooner Art Spiegelman,

covers the Danish Dozen and a host of related issues—freedom of speech and of

the press (“trumpeting its own obsolescence” by leading its readers to the

Internet to see the offending caricatures), the death of opinionated

journalism, the function of graven images, the hypocrisy of publishing photos

of Abu Ghraib but not the Muhammad caricatures, flag-draped coffins, the craven

self-serving cowering of the Bush League, and so on. The piece seems entirely

unrushed, but appearances are deceptive: to get into a June issue, presumably

Spiegelman was writing this exegesis sometime in April, not so long after the

frantic dashing about by the news gathering media in their often failed attempt

to get the facts and to get them right. It was Spiegelman who I quoted in Opus

179 at the end of February: “The notion that the images can just be described

leaves me firmly on the side of showing images. The banal quality of the

cartoons that gave insult is hard to believe until they are seen.” And it was

Amanda Bennett, editor of the Philadelphia

Inquirer, who probably agreed when she published at least one of the Danish

caricatures, citing a famous photograph taken during the Vietnam War: “Would

the words ‘a naked young girl burning with napalm’ have made us understand the

horrors of the Vietnam War as completely as Nick Ut’s iconic photo?” And so Harper’s publishes all twelve of the

pictures, at Spiegelman’s behest, no doubt, and Spiegelman annotates each

picture, explaining who is being caricatured and why. (Muhammad was not the

only person being ridiculed graphically in the series, and not all the bearded

turbaned figures in the cartoons are Muhammad.) The article includes a

reproduction of the page where the caricatures first appeared in the Danish

newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, which

shows how the cartoons were initially presented to the world at large,

clustered around an explanatory article, all under the heading “Muhammad’s

Face.” In other words, the caricatures, when first published, were put in

context by the accompanying prose; they weren’t just sprung on an unsuspecting

public without explanation. No other publication that I know of has done as

much to show us what the fuss has been about, and anyone who wants to maintain

a permanent file of the most disruptive cartoon episode of the last 100 years

is urged, herewith, to get a copy of the magazine.

Spiegelman says that Jyllands-Posten has “a history of

anti-immigrant bias.” Understandable, I suppose, in a small county with a

burgeoning Muslim population that, presumably, seems vaguely threatening to the

natives. This factoid, which I’ve seen alluded to elsewhere in even the

frenetic coverage of February, adds an illuminating lamination to the reason

that the paper offered for conducting its Muhammad experiment—although, as I

said before, the announced rationale seemed reasonable on its face at the time,

regardless of whatever ulterior motives we can muster in the aftermath; see the

aforementioned Opus 179. Writing as a secular Jew, the son of Auschwitz

survivors, Spiegelman brings more than just a cartoonist’s sensibility to the

furor. But as a cartoonist, he is scarcely surprised at the reaction the Danish

Dozen provoked. “Caricature is by definition a charged and loaded image,” he writes.

And when the Jyllands-Posten editor

claimed to be exploring the implications of depicting Muhammad in book

illustration, his first mistake was to invite cartoonists to draw the Prophet.

“Cartoonists!” Spiegelman exclaims: “A breed of troublemakers by profession!”And

when discussing the quisling reaction of the American press, his prose drips

with scorn about the news outlets’ “professing a high-minded nod toward

political correctness that smelled of hypocrisy and fear” that is of-a-piece

with their now well-known reluctance to offend readers or advertisers with

anything approaching an opinionated political cartoon, a rank timidity that has

resulted in making editorial cartoonists “an endangered species, dying off even

quicker than the newspapers that host them.” He continues, a note of satiric

bitterness creeping in: “I hear beleaguered editors and infuriated Muslims

chanting in unison. Both groups, after all, are notoriously wary of images.”

Ahh, Art: I am destroyed with envy over your sharply honed barbs and the deadly

accuracy of your aim.

Of all the responses world-wide to

the Danish cartoons, none, Spiegelman says, were “more flabbergasting than

Iran’s announcement that it would host an international Holocaust cartoon

contest as payback, to ‘test’ the limits of Western tolerance of free speech.”

Whatever the Iranian so-called logic, it struck Spiegelman “as a little

unjust—even somewhat paranoid—to punish Jews for Danish sins.” The most

inspired reaction to the Iranian contest, he says, was that of the artists i Ted

Rall also chimes in on the Danish Disasters with an essay in the March Global Journalist on how he makes a

cartoon and what a cartoon of the political sort is supposed to accomplish.

“The strongest editorial cartoons question authority and conventional wisdom,”

he writes. But it’s a task fraught with risk: “It’s best to cause offense only

in the service of making an important point in order to elicit vibrant

discussion. Sometimes, however, a cartoonist’s faulty execution causes that

goal to be lost, leaving controversy and nothing else.” Which, by one reading,

is what the Danes did. By another reading, however, they accomplished precisely

what the editor was looking for when he commissioned the caricatures:

publishing them revealed how thin the fundamental Islamist skin is, and how

intimidating mobs of irate Muhammad’s followers can be. Rall’s essay is

accompanied by quotations on the issues culled from publications around the

world and by a timeline that traces some of the events that were initiated by

the September 2005 publication of the caricatures. The timeline, alas, leaves

out the crucial December meeting of the leaders of 57 Muslim countries after

which organized protest and street demonstrations began throughout the Muslim

world. Global Journalist looks like a

quarterly, and its cover says it intends to stay on newsstands until June 15,

but if you miss it, you can find Rall’s article at his website, www.tedrall.com : go to the Rallblog, then scroll down to April 10, where you’ll find a link to

the Global Journalist article.

Finally, the most depressing news of

all: The Reuben Journal, the

“program” for the annual Reuben Awards Weekend of the National Cartoonists

Society, May 26-28, declined to print a cartoon that depicted Muhammad. The

cartoon was submitted as one of the ads that are traditionally taken by

cartoonists in the Journal to help

finance its publication. The ad was produced by cartoonist Keith Robinson, whose self-syndicated Making It has been going steadily since 1985. At his website,

Robinson rehearsed the whole ugly tale; herewith—

Just a Cartoon...

"Nothing is mean if it’s funny

enough." —Eddie Haskell

Every

Memorial Day weekend the National Cartoonists Society throws a big whoop-de-do

centered on giving an award—the Reuben (named for Reuben "Rube"

Goldberg)—to the outstanding cartoonist of the year. The printed program—really

a magazine—for this event is called The

Reuben Journal. I, like many cartoonists, take out an ad most years in the Journal. Wednesday, I delivered the

artwork for my page.

Thursday I received a voice mail

from Mell Lazuraus. Mell does the

comic strip Momma. He is also, and

has been for longer than I’ve been an NCS member, the editor of The Reuben Journal. On the voice mail,

he told me how much he enjoyed my work. He was very positive, very

complimentary. At the end of the message, almost as if it were an afterthought,

he said, "Of course, we can’t run this ad. Call me."

"Of course"?

I dialed Mell and made my argument

as to why he could—and should—run my ad. As I rattled off each point, Mell

chuckled, like an indulgent parent listening to his child argue why he should

be allowed to stay up an hour past his bedtime to play Super Mario. Mell waited

until I was done, then said, "So, what have you got for an alternative?"

"Well," I said, "how

‘bout I run something that says, ‘The editor wouldn’t allow me to run the ad I

wanted to. Here’s the URL where you can find it on my web site’?"

"Yeah, I think that’d be okay,”

he said. So here is the ad that will run in the Journal, www.makingit.com/hell_no/ [as well as the

ad that won’t].

What points did I make to Mell as to

why he should run it?

First, newspapers are killing

cartoons. Comic strips have been reduced in size. New strips rarely get a

chance. Local editorial cartoonists are practically extinct. This lack of

support may make people think newspaper cartoons are irrelevant. But the

controversy over the Danish cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad reminds the world

that cartoons can be a powerful method of communication. We shouldn’t ignore

it.

Second, protestors are using the

threat of violence to keep cartoons from being printed. We shouldn’t give in.

Third, there is no historical

tradition that a drawing of Mohammad is in-and-of-itself offensive. While some

Muslims do not make or show images of Mohammad because of the biblical laws

against graven images, there is a long history of portraits of Muhammad in

Islamic art. His image appears in thousands of mosques and on pendants worn by

many Muslim men. There is even a carving of Mohammad on the wall of the United

States Supreme Court Building, along with other historic lawgivers.

Why don’t the media talk more about

this? Perhaps because not talking about it gives them a convenient

rationalization—religious tolerance—for not showing the offending Danish

cartoons. The real reason: fear. This ruse that any drawing of Mohammad is

offensive reminds me of David Letterman’s comment about the apology CBS issued

after Janet Jackson’s "wardrobe malfunction" at the Super Bowl:

"Today, CBS pretended to apologize to the people who are pretending to be

offended." We shouldn’t go along.

And the final point? I think it’s

funny. And if I start second-guessing and softening my cartoons because I’m

afraid someone will get mad —or even violent—then I don’t deserve to ask for

your time to read them.

At their best, cartoons can be

touching, thought provoking, and hilarious all at the same time. That’s what

the Reuben Award celebrates. That’s what I aspire to. Even though I can’t (of

course) run my ad in The Reuben Journal,

I can at least post it on my website. I just may have someone else start my car

for a while.

Footnit

by RCH: NCS is notoriously genteel. As an organization, it

will go to almost any lengths to avoid controversy, particularly controversy

within its ranks. It exists solely to foster good fellowship among cartoonists.

Lazarus’s gentle almost whimsical refusal to run Robinson’s ad is not

surprising. But it is a little disconcerting for a cartoonists’ organization to

decline to get its fingers inky.

BOOK MARQUEE

Checker

Books’ seventh volume of Winsor McCay:

Early Works is out; it was scheduled to appear in August but waited nine

months, the usual period of gestation. ... Alison

Bechdel’s autobio graphic novel, Fun

Home: A Family Tragicomic, is to be released June 8 by Houghton Mifflin.

“The book,” Editor & Publisher says, “recounts the cartoonist’s childhood living with a closeted gay father

who taught English and ran a funeral parlor.” When not producing an autobiography,

Bechdel does a comic strip, Dykes to

Watch Out For.

Wandering lonely as a cloud through

the electronic ether the other day, I chanced upon an online magazine called High Hat, www.thehighhat.com , which turns out to be a repository of intelligent writing about cartooning

and comics. Issue No. 6 is presently up and running; the five previous issues

are also in the vicinity (Nos. 1 and 2, 2003; Nos. 3 and 4, 2004; No. 5, 2005).

No. 6 includes essays on Powers, Ty Templeton, Carol Lay, and Carol Tyler (“wife to Binky Brown

creator Justin Green, working

mother, and maybe the greatest little-known cartoonist in this country, or the

least well-known great cartoonist, or some damn thing”), a long interview with

Rancid Raves fave Keith Knight, and

an appreciation of Abner Dean, a

cartooning star of the 1940s and 1950s who almost no one is aware of anymore.

But we should be: his work, in such tomes as It’s a Long Way to Heaven, “looks like gag cartoons,” as Chris

Lanier says, “—there’s a funny drawing, and then a caption that might provide a

laugh—but on closer examination they reveal themselves to be a different

animal.” Dean’s people in his books are all naked (but without genitalia so

they would not offend even the “values” conscious citizen of our present day),

and the comedy they enact is the human comedy, a bleak vision of life on earth

that Dean represents symbolically in picture after picture, so stark and grim

that we must, for self-preservation, laugh at it.

Bob

Staake’s blog for May 9 is entitled “If Cartoonists Only Knew How To Draw,”

a provocation if ever there wuz. “The cartoonist,” Staake begins, “communicates

to his reader ... through the use of a visual vocabulary—a wiggle here and a

line there and a blotch of ink in between. ... The basic nobility of that cause

innoculates (for the most part) cartooning against the accusations that it is a

vocation filled with practitioners (98% white and male) who couldn’t draw their

way out of a paper bag if their life (or their profession) counted on it.

Imagine turning on the Olympics and seeing 78% of the figure skaters fall on

their asses. Imagine if 70% of all domestic flights crashed on take-off.” Not

only is professional cartooning often marred by ineptitude, Staake continues, but

“it fails to recognize why it isn’t better respected as an industry.”

Cartooning isn’t viewed as a legitimate art form, he says. “Individual

cartoonists deserve respect, but just because they earn it doesn’t mean a

positive residue should trickle down upon anyone who puts nib to paper. ...”

Staake attributes the lack of respect paid the profession to more than mere

incompetence: too many cartooners, he says, “fail to push any aesthetic

envelope or embrace even a modicum of visual experimentation,” a posture, he

continues, “as audacious as it is self-delusional. ... The American comic strip

in particular is mired in pop cultural predictability, most syndicated

cartoonists falling back on a well-established vocabulary of visuals and a less

than venturesome imparting of concepts, ideas, humor and characters.” If

cartooning ever achieves legitimacy as an art form, he says, “it will only

occur when cartoonists en masse make the conscious effort to approach their

work with a commitment to fresh self-expression both visually and conceptually

rather than regurgitating its contextual traditions, relying on establish forms

and a resignation to stagnation over experimentation.”

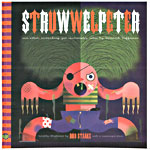

Staake, we hasten to add, practices

what he preaches. You can sample his work at his website, www.bobstaake.com,

or in a book he illustrated that’s just been published by Fantagraphics Books,

Inc.: dubbed “the world’s most nightmarish children’s book,” Struwwelpeter (36 10x10-inch pages;

$14.95) offers ten short poetic tales written in 1844 by German physician

Heinrich Hoffman. Staake has adapted Hoffman faithfully, “all

inappropriateness, Teutonic didacticism and political incorrectness firmly

intact.” In “Slovenly Peter,” we meet a thoroughly unwashed and unkempt kid,

whose “stink exceeds a lethal dose. Don’t believe me? Take a whiff, puke or

poop’s a better sniff!” Cruel Frederick’s abused dog finally turns on his

master, and Pauline, who plays with matches, successfully burns herself up.

That sort of inappropriateness. And Staak

UGLY ART VS. BAD ART

Of

the several blots on the escutcheon of our culture that get my wattles in an

uproar every once in a while, the uppermost one in cartooning is the medium’s

propensity to foster bad art and ugly art. As a visual artform, cartooning

should, perforce, nurture craft and skill at visualization. Instead, it often

tolerates and thereby encourages incompetence and carelessness. Newspaper

cartooning is the only place in our culture that a bad artist can achieve

professional or, at least, commercial status. A bad actor cannot find work; a

bad salesman starves. A bad artist finds employment as a cartoonist doing a

syndicated newspaper comic strip. Or a self-published comic book. Drawing comic

books these days, especially the superhero stripe rolled out by major

publishers, requires a level of proficiency at drawing than bad artists cannot

attain. Not just competence but skill, panache—in style if not in anatomical

accuracy. Self-published comic books, on the other hand, require only

investment capital. And many of them display little else. Fortunately for the artform,

these specimens soon sink in the sea of mediocrity that spawned them: they

surface long enough to satisfy the would-be artist’s ego, then capsize when

they can’t produce enough revenue to satisfy the misguided investor who

financed the project.

Newspaper comics, however, are

different. Garry Trudeau has often

said that in his Doonesbury he made

the newspaper comics safe for bad art. And that is doubtless true. But

cartooning had become a refuge for bad art long before, thanks to James Thurber. Thurber was a writer who

had the good sense to know he couldn’t draw for beans. At the fated moment in

the late 1920s when he was persuaded otherwise, he was sharing office space

with E.B. "Andy" White. The two of them were working for The New Yorker, Harold Ross’s magazine

then in its infancy. Thurber and White were slowly finding their way to a prose

style for the magazine that would distinguish its text in the same way the

cartoonists then working for it distinguished its illustrations. Ross believed

that the best things in the early issues were the cartoons, saying that if he

could somehow elevate the rest of the magazine—chiefly its prose—to the same

level of sophisticated urbanity, he would, at last, have the magazine of his

dreams. In addition to writing "casuals," the short prose paragraphs

for the front section of the magazine, Thurber and White were charged with

polishing the captions of cartoons when the cartoons seemed almost perfect but

not quite. Sometimes the "polishing" turned into complete re-writes.

Over the years, re-captioning cartoons became so customary a practice at The New Yorker that it was widely

acknowledged that the cartoonists themselves were not entirely responsible for

the hilarities their drawings perpetrated. George

Price, for example, apparently only once did a cartoon of which he was the

author of both drawing and caption. (And it was, in fact, not a captioned

cartoon but a funny drawing that celebrated the Yuletide by depicting several

department store Santas riding the subway in costume; it was used on the

cover.) In recent decades, however, the magazine abandoned this whorey

practice: nowadays, with one exception, the cartoons are the concoctions solely

of the cartoonists, who devise both picture and caption. The exception debuted

a few months ago—the cartoon captioning contest on the last page that invites

readers to supply captions for an incongruous tableau supplied by one or

another of the magazine’s contract cartooners. Here, for example, is a drawing

depicting several naked people seated on stage under a banner, “Welcome

Stockholders,” and one of the naked folks, a man, is standing at the podium,

saying—something. Another: a couple of adults walking down the hallway of a

school, children walking on the walls and the ceiling overhead.

At the time Thurber became a

cartoonist, however, he and White were writing most of the captions for the

magazine’s cartoons. Thurber also doodled. A "doodle" is a highly

technical term in the cartooner trade: as the venerable historian and cartoonist Coulton Waugh put it, "a doodle

is a simple basic shape, a form one works out idly while thinking of something

else." As Thurber was thinking of verbal witticisms, he apparently made

crude sketches of his favorite subjects—or, perhaps, of the things he feared

most. Women and dogs. He realized that his drawings were incompetent

excrescences; he habitually crumpled the scraps of paper upon which he’d

doodled and threw them into the wastebasket. We don’t know what prompted White

to retrieve one of these ineptitudes the first time he did it, but he did. And

he then gave it a caption. According to legend, he repeated this exercise

several times over a few days or weeks and, subsequently, showed the captioned

doodles to Ross, offering them as serious candidates for publication as

cartoons. Ross looked at these miserably maladroit scrawls and, cognizant of

Thurber’s penchant for practical joking, thought White was in league with

Thurber, that both of them were pulling his leg. He refused to consider publishing

any of them. Then, to the everlasting detriment of cartooning, Ross saw reviews

of the book White and Thurber did together in 1929, Is Sex Necessary? The reviewers praised Thurber’s drawings, and

Ross, startled no doubt, relented and began publishing Thurber’s

"cartoons." The first appeared in the January 31, 1931 issue of The New Yorker and ushered in the Age

of Incompentent Art, giving bad art a home in American cartooning.

For a long time, Thurber was the

only practitioner of this peculiar performance that purported to raise

oafishness to art—or, at least, to commercial viability. Then Trudeau came

along, trying, with only occasional success, to imitate Jules Feiffer. By the late 1960s when Trudeau’s admiration was

transforming itself into the sincerest form of flattery, Feiffer had made a

career of his acerbic analysis of artsy avant garde pretension in cartoons that

he labored to make look as offhand as The

New Yorker’s prose casuals. The angular style of his earliest efforts for

the Village Voice in the fall of 1956

evoked the UPA style of animated cartooning, which, by the mid-1950s, had

infected much commercial magazine art, illustrations for advertisements as well

as articles. Almost immediately, however, Feiffer evolved his own style, a

loose-limbed sketchy manner that seemed dashed off, the epitome of casualness.

In later years, he was known to draw the individual figures that made up his

cartoon many times, over and over, until he produced several that were, in his

eyes, acceptably loose looking. These he would clip out and paste into the

usual montage of his cartoon. The objective was to preserve the air of

spontaneity that prevailed in the sketches, a goal Feiffer successfully

attained with every one of his published efforts—good art, all of them. Not a

bad drawing in the lot. When Trudeau tried aping Feiffer, he achieved only the

sketchiness but none of the elan that a Feiffer drawing then evinced.

Trudeau’s success, which was

achieved more by the audacity of his wit than the polish of his pictures,

opened the way for others, many of whom could not display an artistic skill

even remotely akin to Trudeau’s. (Trudeau, who majored in graphic design at

Yale, is actually a competent artist—as his strip since his sabbatical in

1983-84 amply demonstrates.)

And so a doodle that escaped the

captivity of a wastebasket in the late 1920s has matured into a host of

varieties of bad or ugly art. Bad art is incompetent; ugly art is competent but

has no eye appeal. It is unattractive because its compositions lack symmetry or

balance or its linear treatment is too tentative or monotonous. Bad art

reflects no confidence in line or composition; ugly art offers no variety in

texture or line. Cathy is bad because

the cartoonist can barely draw. Dilbert and Pearls before Swine, a recent

phenomenon that has captured the so-called imagination of editors everywhere,

are ugly. They are ugly because they are visually uninteresting; they are, in

short, dull. Brevity, a new arrival

on the pages of the News-Gazette, is

another of the same ilk. Agnes, on

the other hand, is neither bad nor ugly. Although it seems to be merely

squiggles on paper, cartooner Tony

Cochran displays a knowledge of anatomy and an ability to depict it; his

characters are recognizably the same personages every time he draws them; he

spots blacks and supplies shading, which gives his squiggles eye appeal. But

too many of the medium’s recent manifestations are either bad or ugly, alas.

At this rate, we’ll eventually reach

the point at which comic strips will be described as a medium in the same way

television is: it’s a medium because it is neither well done nor rare.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis

Miller adv.

According

to Entertainment Weekly, a Christian

anti-porn ministry called XXXchurch has published a New Testament with a cover

proclaiming “Jesus Loves Porn Stars.” The plan is to distribute the books at

erotica conventions starting in June. Says founder and pastor Craig Gross:

“Whether you’re in the porn industry or addicted to it, we, the church, are

here to help.” He’ll learn, of course, that “on your knees” means something

different in porn.

Halliburton, the notorious

government contractor and honeypot for Darth Cheney, has just been awarded a

$385 million grant to build a network of detention centers across the country.

Each of them will be capable, according to report, of detaining up to 5,000

people. What Bush League plans do you suppose this hints at? They say the

contract is merely a contingency maneuver; the centers probably won’t ever be

built. But what contingency prompted the preparedness? The multi-million dollar

grant, meanwhile, will doubtless be spent on a coast-to-coast search for

possible sites among the military installations that have been shut down.

There’s not enough money for much more than that.

Finally, there’s this: in Opus 179,

I quoted Tim Rutten of the Los Angeles

Times, who compared the Danish Dozen to the forthcoming movie, “The Da

Vinci Code,” wondering if the news media, with their newly discovered

sensitivity to the religious convictions of their audience, would be as

circumspect with the movie as they were being with the pictures of Muhammad.

Said Rutten: “The novel’s plot is a vicious little stew of bad history,

fanciful theology and various slanders directed at the Vatican and Opus Dei, an

organization to which thousands of Catholic people around the world belong. In

this vile fantasy, the Catholic hierarchy is corrupt and manipulative and Opus

Dei is a violent, murderous cult. The late Pope John Paul II is accused of

subverting the canonization process by pushing sainthood for Josemaría Escrivá,

Opus’ founder, as a payoff for the organization’s purported ‘rescue’ of the

Vatican bank. The plot’s principal villain is a masochistic albino Opus Dei

‘monk’ for whom murder is just one of many sadistic crimes. (It probably won’t

do any good to point out that, while it’s unclear whether Opus Dei has any

albino members, there definitely are no monks.) ... Neither it nor its members

are corrupt or murderous. It is a moral—though thankfully not legal—libel to

suggest otherwise. Further, it is deeply offensive to allege—even

fictionally—that the Roman Catholic Church would tolerate Opus Dei, or any

organization, if it were any of those things. So how will the American news

media respond to the release of this film? Certainly, there should be reviews

since this is a news event, though it would be a surprise if any of them had

something substantive to say about these issues. But what about publishing

feature stories, interviews or photographs? Isn’t that offensive, since they

promote the film? More to the point, should newspapers and television networks

refuse to accept advertising for this film since plainly that would be

promoting hate speech? Will our editors and executives declare their revulsion

at the very thought of profiting from bigotry?”

Rutten concluded that the media

would barge right on with stories about the movie, effectively promoting box

office receipts and, incidentally, several monstrous canards about the Catholic

Church. And he was almost right. But many of the stories—most of those in the

major weekly newsmagazines—debunked the so-called “history” of Brown’s novel.

They did, in other words, have “something substantive to say about the issues,”

the part I boldfaced in Rutten’s remarks. But otherwise, a plethora of photos

and sidebars, all of which will prod attendance at the movie. If the movie had

been about Muhammad .........

REPRINT

When Darrin Bell’s Candorville began in October 2003, it was apparently about the

multi-ethnic, multi-racial urban milieu. Lemont Brown, the lead character, is

African-American, and his best friend, Sus Homeless persons showed up once a

week in the early months of the strip, snoozing in boxes in the alleyways. Says

one homeless man to another: “The hours are good, but the pay stinks.”

Susan

and Lemont spend many leisure hours on the rooftop of their apartment building,

musing about the world around them. “I think Reverend Wilfred’s gone off the

deep end,” Lemont says. “He told us how Jesus preached peace ... and then said

the U.S. should assassinate Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez.”

Later

in the week, Lemont confronts Reverend Wilfred with this seemingly

contradictory message, but the Reverend explains: “If Jesus were here, he’d

agree with me that we should send ninja assassins with nuclear machetes to

murder Venezuela’s President.” Lemont is aghast: “Jesus would what?” Wilfred:

“Oh, not in so many words, of course, but his meaning would be quite clear.”

Reverend

Wilfred also encourages his flock to vote Republican after he is given $50,000

in tax-payer funds from the Office of Faith-based and Community Initiatives.

Most

of the comedy and satire is entirely verbal, arising in conversational

exchanges among the characters. But Bell also deploys a unique verbal-visual

device: a strip of two panels, one of which explains, often by satiric

contradiction, the other. Here, in the first panel labeled 2001, Lemont, in the

dredlock fashion of the day, is watching tv as the on-camera reporter says: “In

other news, energy company executives are meeting with Dick Cheney to craft

American’s energy policy.” The second panel, dated 2005, shows Lemont with a

crop cut, still watching tv, from which the following issues forth: “In other

news, nobody seems to know why energy prices are so high or why energy

companies are enjoying the highest profits in history.”

In

another two-panel strip, each panel labeled November 2005, Lemont is again

watching his tv, which says: “This just in—President Bush said today it was

absurd for anyone to think America tortures its war prisoners.” In the next

panel, the reporter is saying: “In other news, Vice President Cheney is

lobbying Congress to allow the CIA to torture war prisoners.” Political satire

doesn’t get any more pointed than that.

Lemont

asks a friend: “Dude, what’s it to you whether I say ‘Happy Holidays’ or ‘Merry

Christmas’?” Replies the friend: “Well, my belief system is so fragile that if

I don’t hear ‘Merry Christmas’ everywhere I go this time of year, I’ll stop

believing in God altogether. I’ll become a pervert, I’ll abandon my wife and

kids and take to a life of crime.” Lemont, smirking slightly: “Well, as long a

you have a rational explanation.” The friend: “Fox News is right: you liberals

hate my children.”

Bell’s

style deploys a simple bold line, no feathering or texture, and uncluttered

panels shaded in tones of gray. He also frequently resorts to a close-up of a

character’s nose in a small panel, a labor-saving device that frees him up

enough to draw another strip, Rudy Park,

which is written by the heretofore mysterious “Theron Heir,” lately revealed to be a journalistic personage named

Matt Richtel. Rudy Park had one of

the most unfortunate launches in comic strip history: it burst on the newspaper

world in early September 2001, not a month that anyone was thinking much about

comic strips or comedy. The strip has, subsequently, recovered.

As

might be evident from this, the 31-year-old Bell has a longer history in

cartooning than the short syndicated history of Candorville suggests. He has been drawing the strip in one or

another of its pre-syndication guises for thirteen years. In its first

incarnation in 1992 as a project for Bell’s highschool AP English, it was

called Lemont Brown. “Candorville,

the name of the city where Lemont lives, was rarely mentioned,” Bell said

during one of the Washington Post’s online

interviews. “That changed when I realized Candorville would appear much higher

on any alphabetized list than Lemont.”

While

attending the University of California at Berkeley in 1995, Bell took up

editorial cartooning. He continued Lemont

Brown as a daily strip in the campus paper, the Daily Californian, but it was his political cartooning that first

thrust him into a national spotlight. On Septemb The

next morning, the Daily Californian reported

that more than 100 students clogged the paper’s lobby to protest what they saw

as the “racist” message of the cartoon which portrayed Muslims as rather

simple-minded fanatics. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, xenophobia peaked,

and anyone in the U.S. who “looked Middle Eastern” was at risk, and the

stereotypical images of Bell’s cartoon were seen as fueling the growing

prejudice. The protesters demanded an apology from the paper, but the Daily Cal wouldn’t back down. Quoted in

the San Francisco Chronicle, Editor

Janny Hu said: “We maintain that the editorial cartoon fell within the realm of

fair comment and the First Amendment.” The paper subsequently published letters

on both sides of the issue, but that wasn’t good enough for the more determined

of the protesters, who took the matter to the Student Senate in the form of a

bill that condemned the editorial cartoon and called for the paper to publish a

front-page apology and to subject its staff to “mandatory” (later changed to

“voluntary”) diversity training. Finally, in a maneuver that looked startlingly

like extortion, the bill recommended that the newspaper’s rent be raised for

the offices it occupied in a campus building. The irony was very nearly

overwhelming: Berkeley, remember, was the bastion of the Free Speech Movement

of 1960s.

The

pending legislation drew letters blistering with outrage from several political

cartoonists, including two Pulitzer winners and past presidents of the

Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, David Horsey of the Seattle

Post-Intelligencer, and Steve Benson of the Arizona Republic. Said Benson:

“I was under the impression that only in totalitarian regimes are such blatant

efforts to choke off free expression allowed. Those in the Student Senate who

are trying to gag individual views which they deem unacceptable have completely

misread the cartoon. Bell was focusing his fire at the Islamic fundamentalists

responsible for the terror attacks against the World Trade Center, not at

Muslims in general.” The effort to extort an apology from the paper by bringing

financial pressure to bear was, Benson said, “completely antithetical to the

American tradition of unfettered free speech.” Horsey, referring to his own

experience with protesters, said he was quite familiar with “interest groups

who purposely misread and find unintended meanings in cartoons primarily to

forward their own political agendas. ... A fair reading of [Bell’s cartoon],”

he continued, “would make it clear the intent of the cartoonist was to

criticize terrorism, not Islam or Islamic people in general. ... It is

outrageous that the senators are giving any thought to a measure which would

seek to stifle freedom of speech and freedom of the press. This is an action

worthy of some authoritarian regime, not a student government centered in a

great university which is dedicated to the free exchange of ideas. ...

Threatening sanctions of a free press—even a student-run press—stinks of

McCarthyism.”

The

bill was, to the best of my knowledge, never passed. The final irony of the

episode is that Bell, accused of racism, is somewhat a racial minority himself.

With a white Jewish mother and a Black father, Bell is the very definition of

biracial. He defiantly chooses neither: “I’m both,” he says, “—not half, but

both is the way I look at it. ... Most biracial people know they have feet in

two cultures, and they’re okay with that. It’s the rest of the world that wants

them to choose.” Some of his Candorville strips have provoked a certain amount of flak, he admits, “primarily from White

critics who feel it’s their duty to tell me I’m being offensive to Black

people.” Anyone who thinks he’s white is “half wrong,” Bell says.

While

at UC Berkeley, Bell showed his editorial cartoons to the Los Angeles Times, which published them as freelance submissions.

The paper also ran some Lemont Brown strips.

“I sent them Lemont Brown every day

for a year,” Bell laughed as he talked to Mike Peters at the Dallas Morning News in 2004, “and

finally they agreed to run it once a week ‘and then we’ll see.’”

About

then, Bell met Richtel, a journalist at the Oakland

Tribune who was developing the Rudy

Park comic strip. Bell continued freelancing editorial cartoons for a year

or so after Rudy Park debuted, but

once Candorville started, he gave up

editooning.

Candorville, which now appears in about

300 newspapers, is “semi-autobiographical,” Bell said. “A lot of me is in

Lemont, especially his anxieties. Only difference is my ‘Susan’ is actually my

wife, not a platonic friend. I’m much, much luckier than Lemont.” Bell told

Mike Peters that his wife, Laura, is a big fan of Susan, and Susan even looks a

bit like her. “They have some common personality traits,” he said, “but they

are different enough that if I do something not particularly flattering, Laura

knows it’s not her.”

As

for the rest of the strip’s cast, “it’s a balancing act of fiction and real

life,” Bell said. “I’ve taken all my friends and squeezed them into three

characters. They are amalgamations of what’s going on in my life, not a diary.

I can think of situations and throw them at the characters, and the way they

react is from my life.”

Clyde,

the aspiring rapper and would-be thug, is Lemont’s childhood friend, but,

unlike Lemont, he has never stopped being angry at the world. Said Peters:

“Nothing is ever his fault. Nobody matters but Clyde. Since life’s unfair, the

only way to win is to cheat your way through it.”

Clyde

is a fairly overt stereotype and a negative one at that. To which Bell

responded during his online interview: “Unfortunately, the fact that something

may be a stereotype doesn’t mean there’s no truth in it. There are many, many people like Clyde. I think most of them hang out on my corner in

Oakland. I try my best to get at the heart of why he behaves the way he does

because I don’t think ignoring people who make all the wrong choices will ever

help them make the right ones. I want people who might see a lot of themselves

in Clyde to see him make mistakes, to see why he’s wrong, to laugh at that part

of themselves, and, hopefully, to think twice the next time they have an urge

to act like Clyde. I balance Clyde against Lemont, the protagonist of the strip,

for that purpose. Where Clyde goes wrong, Lemont goes right and puts things

into perspective.”

Bell

tries to avoid being preachy, he told Peters. “Being preachy is easy. But I

won’t deal with any heavy issue unless I can find either a joke in it—that doesn’t

belittle the issue—or find a truth in it that will make people laugh,

especially if they haven’t thought of it before. Making people laugh is

essential.” If he can’t find a comedy in a situation, “I put it on the back

burner until the right angle comes to me,” he said.

“I

want to make people laugh and think at the same time,” Bell said during the

online session. “I think you can’t poke fun at the important ironies of life—or

even the frivolous ones—without being an activist in someone’s eyes. Candorville’s social activism is an

expression of my naive belief that people should never be afraid to ask

questions, even if those questions are unpopular. I don’t pretend to have any

answers, but I do have an awful lot of questions. ... Whether I make people laugh

or I make them angry, or I make them shake their head in disbelief, or I just

make them yawn, I realize how fortunate I am every day that I get to wake up

and create something that other people will read. I get to do that, and I get

to draw funny pictures. I get to do that for a living. It won’t make me rich,

but it makes me happy and fulfilled, and I’m thankful for every day I get to do

it.”

FUNNYBOOK

FAN FARE

The second issue of American Virgin delivers on the promise of the first issue. The

smarmy religious virginity of its protagonist is increasingly assaulted by the

increasing misfortunes of his life: his finance killed in Africa, Adam goes

there to retrieve her body, accompanied by his potty-mouthed sister. En route,

Adam loses his holier-than-thou cool more than once. He comes upon

bare-breasted native women and little boys diddling themselves, offenses to his

evangelical sensibilities. Rude stuff. This series will either end with his

re-instatement as a fanatic or with his complete disillusionment.

Loveless No. 6 is a beautifully

rendered, done-in-one tale of African-American life before and after the

supposed emancipation of the Civil War. Drawn by Danijel Zezelj, the entire

issue takes place around a night-time campfire in the woods, and the surroundings—the

trees like silent judging sentinels—are exquisitely evoked in fading light and

deepening shadow.

The

fourth issue of The Exterminators continues

as one of the medium’s most disgustingly intriguing enterprises. But the

enormous fat lady on the couch, where she’s been sitting, unable to rise, since

1992, is a bit much; and her complaint is that a rat is biting her on the ass

from underneath. ... Alan Moore’s last

issue of Tom Strong, No. 36, is one

of his sf bafflers, moving in realms I cannot recognize. Chris Sprouse’s art, as always, entertains. But the story, which

eases us up to the “end of the world” signaling the end of the comic book and

(?) of Tom Strong? Is he dying? Being transported to another plane of

existence? Well, it’s probably excellent, but not my cup of tea, except for the

last page, where all the Strongs stand on a balcony, waving farewell to all of

us.

Next Wave, now up to No. 4, continues to

be one of the best superhero romps in the funnybooks—mordantly witty with snappy

patter among the characters and a smart-alecky narrator. Warren Ellis clearly has his tongue in his cheek, but the

adventures, despite the light-hearted patois, are threatening enough and his

heroes ingenious enough in extracting themselves. In No. 2, they dispose of the

giant dragon in the purple shorts; in Nos. 3 and 4, a grizzled cop is infected

by a life form that turns him into a giant robot, but the heroic ensemble

manages to eradicate the disease, restoring the cop to life as he knew it,

albeit a little the worse for wear. Ellis produces tracts of action without

much dialogue, and it’s fun to follow it. And Stuart Immonen’s art is crisp and clear, boldly outlined with

fineline trim. I’m reminded of Mike

Mignola but without shadows and so many solid blacks. Beautiful. And

thoroughly expressive of whatever the plot needs. The simplicity of the artwork

is suitably enhanced by Dave McCaig’s colors,

which give nuance as well as substance to simple shapes and outline figures. A

final big plus: the opening page in each issue introduces us to the characters

and their various idiosyncracies and powers. Nicely done, Ellis.

Continuing

the parade of excellence but this time with a genuine, full-bore slapstick

send-up of superheroics, we have Truth,

Justin and the American Way, written by Aaron Williams and Scott

Kurtz and drawn—ah, illuminated, levitated—by Guiseppe Ferrario. In bare

outline, the story is simple enough. We meet Justin Cannel, a nerdy stockroom

boy, who, on the eve of his wedding to the toothsome Bailey, is going to his

bachelor party. His friends have sent him a box with a costume to wear for the

occasion, but, unbeknownst to them or to Justin, an alien spy, fleeing the

authorities with a super-endowed costume in a box under his arm, has switched

packages, leaving the powered longjohns on the front seat of Justin’s car.

Justin gets home and puts the suit on, and it turns out to have a mind of its

own but one commanded by whatever Justin says that the suit interprets as a

directive. So when Justin, after donning the garment, says, “This thing doesn’t

fit!” the suit promptly shrinks in every extremity until it fits him perfectly.

The suit endows him with super strength, too. Wearing it, Justin goes to his

bachelor party, which is being held in a room in a swank downtown hotel. And it

has just been raided by an operative of the FBI, looking for the suit. When

Justin won’t give up the suit fast enough, the guy—or, Baxter McGee, to invoke

what he offers as a name—waves his pistol around, discharges it accidentally

and shoots Justin, whose costume, naturally, makes him impervious to bullets.

Justin, in an uncharacteristic retaliatory fit, punches McGee and sends him

flying across the room. When McGee gets up and shoves his gun under Justin’s

nose, the costume causes Justin to disassemble the piece. McGee then pulls out

a grenade, arms it, and tosses it to Justin. Justin wants to throw it out the

window, but his friends warn him that there are people down below. “What do you

want me to do?” Justin blurts out, “—fly away with it?” The suit interprets

that as a command and promptly activates its flying mechanism, sending Justin

upward, smashing through the ceilings of successive floors of the hotel until

he reaches the rooftop swimming pool. When the grenade goes off, Justin is

dislodged from the floor of the pool and plummets down through the holes he

made going up until he’s back in the room where it all began. Then, seconds

later, the pool drains through the holes Justin made, descending through the

hotel in a cataract. Justin and his friends leave the hotel (and the damage

they’ve inflicted on it), pretending to be dissatisfied with the hotel’s

service; they continue the party at Bailey’s apartment. She comes home and is

understandably distressed to see her place trashed by the adolescent behavior

of Justin’s beer-guzzling buddies. That brings us to the end of No. 2 with only

another 2-3 issues promised in this limited series.

Well, I guess the story isn’t as simple to outline as I thought it was. But the idea is: a nerdy teenager gets to wear a self-actuating super suit that interprets the kid’s every wish as a command, and trouble ensues. Also comedy, most of which is due to the superb rendering by Ferrario, a 36-year-old Italian who, for the last twelve years, has been working in animation. I learned all that by visiting Kurtz’s website, www.pvponline.com , but as I watched the action unfold in the comic book, I was pretty confident that the artist was an animator: it has all the tell-tale earmarks—no linear loose-ends so the linework supplies leak-proof color-holds throughout, for one thing, masterful comedic pacing for another, plus visual hilarities galore, manic exaggerated expressiveness in the actions and reactions of the characters—but more than that, the artwork displays an absolute command of the medium. Narrative breakdowns, panel composition, timing—all executed flawlessly with an eye towards creating humor at every possible turn. Ferrario’s line flexes from bold to fine and back again, a thing of beauty in itself, and he also did the coloring, I believe (no one is credited with it), and his colors add nuance and emphasis, not to mention background detail, on every page. The story, mildly amusing in itself, is turned into a major comedic achievement solely by Ferrario’s interpretation, his refinements and sight gags, including incidental caricatures of notable personages. The joy in reading this book derives entirely from the pictures. Here are a couple pages.

In the first, we see Justin

stopping at the liquor store to pick up a keg of beer for his bachelor party.

Notice from the 1970s tv series “Sanford and Son,” Red Foxx and Demond Wilson

in the foreground of the top panel. The perspective in this panel, by the way,

is that of a security camera. What a hoot! The kegs that Justin lifts at the

bottom are not empty: he thinks they are because the suit has given him,

without telling him, super strength so a full keg feels to him like its empty.

One panel might make the point with the aid, say, of a caption; but two panels

do the job visually with no verbal accompaniment. (Subsequently, the liquor

store clerk tries to lift one of the “empties” and we find out, for sure, it’s

not empty.) On the other page in this vicinity, we see Baxter McGee in the

first panel; he’s contemplating Justin’s super-powered flight upwards through

several floors of the hotel, clutching the grenade. (McGee thinks Justin is a

communist operative.) The panel composition makes sure we see the hole in the

ceiling above McGee so we’re ready for Justin to drop out of it in the next

panel. Then panels 3 and 4 prepare us for the deluge of the descending swimming

pool, which arrives in panel 5. The change in perspective in panel 4 emphasizes

the characters’ dawning realization of impending dampness and thereby heightens

suspense for a moment before the liquid catastrophe is upon them; nice touch,

nicely dramatic—and cinematic. In a final risible fillip, Ferrario next shows

us the waterfall as it completes its descent and spews through and out of the

hotel into the street outside. The action creates the comedy, and it does so in

the continuous manner of an animated cartoon, one thing leading to another in

hilarious succession.

In

recent years, fans have accepted great variation in drawing styles for comic

books, making possible cartoony mannerisms like Ferrario’s as well as the

detailed realism of, say, Howard

Chaykin, the stark expressionism of Phil

Hester and Ande Parks, and the

linear precision of Eduardo Risso.

We are lightyears away from the days when everyone was expected to draw like

Neal Adams. And so we’ve seen plenty of “animation style” renderings in the

last few years, many of which are as cartoony—as Warner Brothers-ish—as

Ferarrio’s. You might be tempted to think Justin is just another in that style. You’d be wrong. Ferarrio works in that

style, but he elevates it to high comedic art. Don’t miss this one.

And Then There’s Liberality For All. We may safely assume, I think, that Mike Mackey and Donny Lin, the writer and artist who perpetrated the so-called

comic book Liberality for All, expect

the more liberally inclined of their readers, like me, to foam at the mouth

when untangling the tripe of their book’s first issue. The concept of Liberality, after all, is to debunk a

history that is imagined to fit what these authors believe the liberal vision

is. We should be irate, then, at what they suppose is a liberal administration

of government. In Mackey’s heavy-handed reconstruction of recent history, Al

Gore won the 2000 election, precipitating a couple generations of liberal

presidencies. Gore’s response to 9/11 was to “negotiate” with the terrorists,

resulting, by 2021, the time of the tale rehearsed here, in Osama bin Laden

becoming the Afghanistan ambassador to the United Nations. We see bin Laden,

plotting with his cohorts and saying, “The American government poses no threat

now. We will negotiate with the infidels until our daggers are the sharpest.”

And, addressing the U.N., he thanks U.S. President Chelsea Clinton and Vice

President Michael Moore—“If it were not for American leaders like them, I would

not be here today,” he says and then continues to “apologize” for the “misunderstanding of September 11th,

2001.” After this orientation, we follow the exploits of Sean Hannity,

part-time radio talk-show host, who now has a mechanical arm and moonlights on

a heroic mission—to protect America from an atomic attack in the form of

briefcase bomb and, eventually, to restore a conservative government. He is

assisted, in this installment, by a mustached bald-headed guy named Liddy, who

regrets the disbanding of the NRA (“so many cold, dead hands,” he murmurs) and

says he hates “all the electronic gun control junk” he finds on his weapon.

“The best gun control,” he says, is achieved “by using two hands.” Throughout

the adventure, Mackey slips political grenades into his tale: the briefcase

bomb is, we learn, “Iraqi-designed,” a sly assertion that rejuvenates the

mythical partnership between bin Laden and Saddam.

Despite

the ham-fisted political message, the book is adroitly constructed in the best

comic book manner. As we turn the pages, we are tugged along by three

storylines: one in pictures, another in captions, and a third in staticky

speech balloons that represent radio broadcasts. The latter are divided into

two “voices”—right and left. In effect, then, as we watch the action unfold

before us, we are treated to three “voice over” strands. Here’s a portion of

one of the radio strands: “I will never forget what the liberal left has done

to our country ... our nation’s once mighty military conscripted into U.N.

troops! God taken off of our money and out of the Pledge of Allegiance, not

that anyone should swear allegiance to what the ‘new’ American flag represents!

And now Iraq, Iran and the Unified Republic of Korea all have nukes!”

In

captions, we have another voice in a melancholy drone: “That which is given and

not earned is seldom appreciated,” implying that the left-leaning generation in

power has done nothing to earn their freedoms (but that the out-of-power

right-wing has, in some unspecified way, earned theirs, the same freedoms).

“Like spoiled children, we [the hapless citizenry under the Clinton-Moore

regime] squandered our fortune of freedom and liberty and were shocked when it

was gone. Now that generation of fools stands on the shoulders of giants and,

with outstretched arms laden with wanton bowls of entitlement, unashamedly

asks, ‘Please, sir, I want some more!’ Those who fought for our rights etched,

then eroded, a path of destiny for this country to flow. The turbulent current

that boldly swept this country through time has been diverted by poor

leadership. Our nation’s course, which was once like a forceful torrent, has

become an insignificant stream, taking the path of least resistance ... the

flow of freedom that welled forth from our nation’s capitol has stagnated into

the dank swamp of its geologically historic roots. Many liberties have been

lost there, pulled down to the dark murky depths.” This funereal dirge is also

a call to arms: by denigrating the present state of affairs, revolution is

encouraged, leading, we must suppose, to the restoration of right-thinking good

guys to governing power.

Hannity

and Liddy survive their first encounter with the law enforcement agencies of

the present regime, but they still must capture the briefcase bomb. Lin’s

artwork is thoroughly competent, distinguished by a rickety but appealingly bold

line without much feathering, and his coloring participates in the propaganda:

the early sequences featuring Hannity are in red while the panels focused on

his opponents are blue. Cute.

While

I appreciate the cunning manipulation of the medium despite the purple prose of

the captioned voice-over, the best part of the book is its revelation of the

alleged “thought processes” of the Right. How do these guys think? And why do

they think that way? In Mackey’s drone, we find the answer. Their opposition to

the Left is, if we are to judge from what we see here, based upon the

conviction that any deviation from the Received Wisdom of the Right leads, as

naturally as water flows downhill, to the deterioration of society and, by

extension, of the quality of human life itself. There’s an inexorability about

this nightmare: give an inch, and the whole fabric of society as we know it

will be torn asunder. The only way to deal with bin Laden is to stomp him into

the ground. That’s it. Anything less than that will inevitably lead to his

assuming power in the U.N. And in the next issue of Liberality, it seems he’ll become President of the U.S. So we must hold the line against any

corruption of the purity of Right thinking. No compromise is possible. (So a

democratic form of government, in which compromise is the essence, is out of

the question.)

I

can understand now, better, the opinion of a right-wing-nut friend of mine who

has no objection to gays’ sexual orientation and practices but will not endorse

the idea of gay marriage because it would lead, inevitably, to old men marrying

young boys and, hence, pedophilia would be legalized and run rampant. Marriage

would be corrupted beyond redemption. When I pointed out that condoning

marriage between a man and a woman did not, ipso facto, devolve into the

marriage of old men and pre-pubescent girls—there are laws prohibiting

under-age marriage without parental consent—it made no difference. Not that it

matters much. Marriage is already hopelessly corrupted. When, centuries ago,

societies slowly gave up the practice of arranging marriages as if they were

real estate—in which women were regarded as the property of the male

population— “love” became the basis for marriage. And if “love” can be the

reason for marrying, the absence of “love” is sufficient reason for divorce;

hence, the divorce rate soared until it almost matches the marriage rate.

Marriage—i.e., family life as we used to know it—has been completely destroyed

by the insinuation into the otherwise perfectly reasonable property “contract”

the notion of “love.” So why worry about the effects of gay marriage upon this

decayed and disgraced institution?

BUSHWHACKING (continued as a permanent perpetuation)

Mortimer B. Zuckerman, editor-in-chief of U.S. News and World Report, a sometimes

right-tilting weekly newsmagazine, concludes the May 22 issue with an editorial

saying: “For Republicans to even try to present themselves to voters [this

fall] as fiscal conservatives after five years of reckless budget-busting, is

not just absurd. It is insulting.” It is, he correctly asserts, “hypocrisy on

stilts.” That’s good: hypcrisy on stilts.

In

his column for May 16, Ted Rall, eternal

gadfly and art-wiz, takes up the “secret” (no more) government eavesdropping

effort, asking: “If losing our privacy can prevent another 9/11, isn’t it worth

it?” His answer: “No. Hell no. First and foremost, domestic spying is not an

anti-terrorism program. It is terrorism.” And he reminds us of how absurd the

idea of electronic eavesdropping is to begin with: surely, if bin Laden and his

operatives were shrewd enough to engineer the airplanes-as-missiles scheme,

they’d be smart enough to know that telephone communication, whether by corner

pay phone or cell, is not a good way to stay in touch with each other. Surely

they know their phones, whatever devices they may use, are being tapped. And

then Rall wonders why we are so peeved over the NSA data-mining and domestic

surveillance efforts. In the 1990s, he reminds us, a NSA factotum “freely

admitted to the French magazine Le Nouvel

Observateur that its Echelon keyword and voice-recognition software system

sought to intercept ‘every communication in the world.’” So why are we shocked, shocked, these days, a decade later, to find out the guy knew what he was talking

about? It’s been going on for years. And we ostensibly knew about it.

In

another recent column, Rall discusses GeeDubya’s messianic vision of himself as

savior of the world. “Despite the man’s wacky religiosity,” Rall writes, “I

have been giving Bush the benefit of a small amount of remaining doubt after

five years of the most disastrous rule this nation has ever suffered. I

believed that he was breathtakingly bigoted, stupid, and ignorant. But I didn’t

think he was out of his mind. Until now.” What happened that changed Rall’s

mind is that George WMD Bush denied Seymour Hersh’s contention in The New Yorker that the Bush League was

contemplating nuking Iran, but in denying it, GeeDubya also said that he

reserves the right to wage preemptive war—and that he hasn’t taken the military

option, including nukes, off the table. “Bushspeak analysis shows that it’s no

denial at all,” Rall says, and he goes on: “Many people have asked me during

the last year whether I thought Bush would attack Iran. I said no, because he’s

out of troops, out of cash and out of political capital. He couldn’t, so he

wouldn’t.” Now Rall isn’t so sure: “You don’t need troops, money or the support

of the American people when God talks to you. And when you’re insane.”

All

the buzz in early May was about Stephen

Colbert’s “blistering tribute” to George W. (“Warlord”) Bush at the White

House Correspondents Dinner. GeeDubya, it sez here in the Editor & Publisher report, “was not amused.” It was a brilliant

bit of satire, though—no question. The eerie thing about it was how silent the

room was as Colbert’s purpose began to emerge, enlarge, and then explode. All

those hard-nosed correspondents evidently were too intimidated by the Bush

League to actually laugh at some pretty funny remarks. For example, Colbert, in

his persona as a witless but dedicated conservative Bushite, criticizes the

press for it’s negative attitude about GeeDubya. About the recent personnel

changes at the White House, Colbert says, “you write, ‘Oh, they’re just rearranging

the deck chairs on the Titanic.’ First of all, that is a terrible metaphor,”

Colbert continues. “This administration is not sinking. This administration is

soaring. If anything, they are rearranging the deck chairs on the Hindenburg!”

(a reference to an aerial disaster equal in tragedy if not body count to the

sinking of the Titanic). The press corps sat there, frozen in terror at what

GeeDubya might say or do. Would he leave the head table, where he was seated,

just 15 feet from Colbert? Would he just sit there and continue sulking? Or

would he send for the Secret Service hit squad to rub out the offending

comedian? No one knew for sure. You can find the complete transcript at http://www.editorandpublisher.com/eandp/news/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1002461887 . (If this URL isn’t all on one line, copy it and paste it into your browser.)

And if you Google for Stephen Colbert, you eventually will find a videotape of

his presentation, which adds the dimension of the silence of the room. Colbert’s

chutzpah in continuing his gutsy routine without much encouragement from the

audience—and certainly nothing but sullen silence from his target—is

astonishing, a ringing, albeit silent, endorsement of his show business

dedication.

With

the so-called Iranian crisis, the Bush League is up to its usual trick, foreign

policy by foot-stamping. GeeDubya stamps his foot and demands that some other

country do as he says. He won’t talk to them until they do as he tells them to.

Unfortunately, if they do exactly what he tells them to, there won’t be

anything to talk about when they start talking.

Finally,

I can’t resist quoting the following in its entirety.

I’m the Decider

by Roddy McCorley

Well, it

took me awhile, but I finally realized what "I’m the decider" reminds

me of. It sounds like something a

character in a Dr Seuss book might say. So with apologies to the late Mr.

Geisel, here is some idle speculation as to what else such a character might

say:

I’m the decider.

I pick and I choose.

I pick among whats.

And choose among whos.

And as I decide

Each particular day,

The things I decide on

All turn out that way.

I decided on Freedom for all of Iraq.

And now that we have it,

I’m not looking back.

I decided on tax cuts

That just help the wealthy.

And Medicare changes

That aren’t really healthy.

And parklands and wetlands—

Who needs all that stuff?

I decided that none

Would be more than enough!

I decided that schools,

All in all, are the best.

The less that they teach

And the more that they test.

I decided those wages

You need to get by,

Are much better spent

On some CEO guy.

I decided your Wade

Which was versing your Roe,

Is terribly awful

And just has to go.

I decided that levees

Are not really needed.

Now when hurricanes come,

They can come unimpeded.

That old Constitution?

Well, I have decided—

As "just goddam paper,"

It should be derided.

I’ve decided gay marriage

Is icky and weird.

Above all other things,

It’s the one to be feared.

And Cheney and Rummy

And Condi all know

That I’m the Decider—

They tell me it’s so.

I’m the Decider

So watch what you say,

Or I may decide

To have you whisked away.

Or I’ll tap your phones.