|

|||

|

Opus 178:

Opus 178 (February 13, 2006). Hoppy Valentine’s Day, kimo

sabe. We’re a little shy on newsy tid-bits this time: because of the furor over

those 12 cartoons of Muhammad in Denmark, we’re devoting the largest portion of

this installment to the Danish Dozen. They were published last September, but

the outrage in the Arab street didn’t reach riotous proportions until about two-three

weeks ago. If the objection to the cartoons is so sincere, why did it take so

long to erupt in such fury? We trace the evolution of the protest, provide

links to the offensive images, and quote a score or more of opinions about the

cartoons and the role of the press in a democracy. Our second longest segment

reviews Ron Goulart’s re-issued The Adventurous Decade and tries to

identify the “first” adventure comic strip, an attempt that involves Allan Holtz’s surprising research.

Here’s what’s here, in order: NOUS R US —New

Disney CEO connected to comic book history, Doug Marlette finds an editoonery berth in Tulsa, Tintin in trouble

again, and an object lesson in why it’s not a good idea to mug a cartoonist; THE DANISH DOZEN —Why they are

offensive to Muslims and why it doesn’t matter what they look like, a link to

the images, the crusade for freedom of expression in democracies vs. virtue in

Muslim countries, what cartoonists are saying about it, including a sterling

essay by Pulitzer winner Signe Wilkinson; the Tom Toles Flap and why nobody

has heard about it; Word of the Year; Oswald Goes Home; COMIC STRIP WATCH— Dilbert gets naughty

and Garfield goes nutso; the humble woodchuck and the State of the Union; BOOK MARQUEE— another publisher starts

a line of graphic novels, a new Jaime

Hernandez tome, the best scholarly source on comics, New Yorker cartoons and the tradition of excellence; MICHAEL BERRY and why he never made it

into Playboy; Are Americans Conservative? THE

ADVENTURE COMIC STRIP; Funnybook Fan Fare —Nextwave, Revelations; GRAPHIC NOVEL— Earthboy Jacobus; and a little recreational Bushwhacking. And our

usual reminder: when you get to the Member/Subscriber Section, don’t forget to

activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so

you can print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at

your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

NOUS R US

The

Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, Vermont— Jim Sturm’s comics college—reached the

conclusion of its first semester recently, and the results look good: “It’s a

pass/no credit system,” said Sturm, “just like Harvard Medical School.” Maybe,

but I wouldn’t engage any of his graduates to remove my tonsils or any other

body part. Tuition is $14,000, “and that doesn’t include colored pencils.” ...

Bob Andelman, the author of Will

Eisner’s official biography, A

Spirited Life, says Eisner has a connection to Disney: the new CEO and

President of the Mouse House is Bob Iger, great-grandson of Jerry Iger, Eisner’s partner in the

comic art shop the two set up in the 1930s.

Doug

Marlette, who has been cartooning for the Tallahasee (Fla.) Democrat from his home in North Carolina, will be moving to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to take the

editorial cartooning chair at the Tulsa

World, which fired its previous editoonist for apparent plagiarism. (See Opus

175.) Pulitzer-winner Marlette, who also produces the syndicated comic

strip Kudzu, is a visiting professor at the University of Oklahoma in Tulsa and

likes the idea of joining the staff of a newspaper that is family-owned, not a

link in a corporate chain like the Democrat, a Knight Ridder paper. Marlette’s second novel, Magic Time, is scheduled for release in September by Farrar, Straus

& Giroux, which also published his first, The Bridge, in 2001. The Democrat, meanwhile, has been flooded with applications from editoonists eager to assume

Marlette’s mantle, but the paper hasn’t decided yet whether to replace him.

Chances are, it won’t. Almost no newspapers with circulations comparable to the

Democrat’s modest numbers have editorial cartoonists on staff. Rumor has it

that Marlette was hired there because one of the editors was an old friend.

Editoonist Tim Menees was laid off at the Pittsburg

Post-Gazette in early February. It was another in the industry’s tsunami of

cost-cutting moves: the family-owned Block Communications chain is facing

negotiation with its union this year and doesn’t believe it can survive with a

union work force unless it reduces expenses. The paper also laid off its

Washington Bureau chief, Michael McGough, who, like Menees, is non-union. When

I met Menees over ten years ago, there were two daily newspapers being operated

out of the building where he worked. Both had editorial cartoonists, Rob Rogers being the other one. Then

the two papers merged. Surprisingly, the new entity kept both cartooners on

board, and Rogers survives this purge. Menees, who deployed a unique style and

concentrated on local issues, will be sorely missed. He has been at the paper

for about 30 years, but Allan Block said simply: “We don’t need two

cartoonists.” “Looks like a strength to me,” said editooner Clay Bennett, “—a great one-two punch.

I guess it looks different through the eyes of an accountant.” Bennett, who is

president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, said he when he

was starting his career, he worked with Menees at the Post-Gazette. “Tim took me under his wing and taught me a lot about

cartooning. He’s been a great colleague and friend. I take this very

personally.” Menees resisted getting syndicated because he thought local issues

were more important; and if more of his brethren shared his conviction, there’s

a change the profession wouldn’t be en route to extinction these days.

Tintin is courting danger again, this time, from People for Ethical Treatment of

Animals (PETA), who have raised objection to Tintin in the Congo, just released in English for the first time,

because the book “glorifies the hunting and mindless ill-treatment of animals.”

The book is also not particularly kind to Africans, who, the translators note,

“are depicted according to the bourgeois, paternalistic stereotypes of the

period” of the book’s composition, a fault the author, Herge, admitted to

sometime after the volume’s initial publication.

Here’s a good reason not to mug a

cartoonist. Daryl Cagle reports on

his blog that 82-year-old Aussie cartooner Bill

“Weg” Green ran out to his carport when he heard someone swearing up a

storm out there. Turned out it was a thief, who pushed Green away and made his

getaway on the cartoonist’s grandson’s bicycle, even though it had two flat

tires at the time. When the police arrived, Green drew a caricature of the

robber from memory and gave it to the coppers, who immediately recognized the

fugitive as a man they’d just arrested for another crime and were holding in a

van.

THE DANISH DOZEN

Satanic

Drawings

We

may not, as I’ve said on occasion, print all the cartooning news here, but you

may be assured that we publish the best of it. Our story on the flap over the

Danish cartoons of Muhammad ran in our Christmas Issue (right here),

which appeared in the digital ether just before December 24. By then, the

Muslim protest inspired by depicting the Prophet had been spreading, but

slowly, since the publication of the cartoons on September 30. Since Christmas,

other newspapers in Europe reprinted the cartoons, apparently to prove that the

freedom of the press would not be intimidated by Muslim sensibilities. Then,

suddenly—seemingly overnight—the Islamic world was roiling with mobs in the

street, shaking fists at the sky, burning cars and flags, breaking windows,

assaulting embassies, and terrifying bystanders. Once there were action-packed

street scenes to film, the ever alert American media took notice, on or about

February 2, and for the next two weeks, we had a daily dose of Arab rioting to

witness vicariously. What happened? What transformed the relatively tame

protest of three months duration into an attack on civilization in ten

countries, leaving, to-date, ten or more dead in its wake?

I’m tempted to say, rubbing my hands

in smug satisfaction, that’s vivid testimony to the power of cartoons. Tempting

as it is to congratulate the medium, the cartoons were not the authentic cause

of all this turmoil. They were just the match, struck too near the tinder of a

Muslim world rife with resentment and riddled with marauding bands of

incendiary political hooligans, looking for opportunities to advance their

agendas.

While Westerners may not, given

their heritage, ever fully grasp the reasons for the Islamic rage, we may

approach an understanding by remembering two things about the Muslim world.

First, the popular Western notion of Islam as unsophisticated and

anti-intellectual is not only wrong-headed but historically inaccurate. As

Charles Kimball points out in his book, When

Religion Becomes Evil, “when Europe was languishing in the Dark Ages,

Islamic civilization was thriving from Spain to India. For several centuries

Muslims led the world in areas such as mathematics, chemistry, medicine,

philosophy, navigation, architecture, horticulture, and astronomy.” Then, as

Kimball puts it, “something went wrong. From the sixteenth through the

twentieth centuries most of the lands with a Muslim majority fell under the

control of outside powers,” and the vitality of the Islamic civilization faded

away. Today, throughout the Muslim world, the followers of Muhammad are baffled

by this fall from influence and hope for its return.

The second cause of the resentment

rooted in the fundamentally different emphasis in the value systems of the two

cultural traditions. In the West, “freedom” is the most powerful orienting

principle. Anything that fosters freedom is valued; everything that threatens it

is condemned. In the Muslim world, “virtue” is the parallel value. To the

Muslim, the freedoms of the West seem licentiousness, and they therefore

threaten the virtue of his world and must be condemned and rejected in the most

strenuous way.

Complicating this polarization is

the steady influx into European countries of immigrants from the Middle East

and Asia, creating in every country a large minority population determined to

remain outside the cultural mainstream of those countries. Islam is now Europe’s

fastest growing religion and is now the second largest religion in most

European countries. Molly Moore of the Washington Post Foreign Service notes

that “many of Western Europe’s estimated 15 million Muslims feel alienated by

cultural barriers and job discrimination and stigmatized by anti-immigration

movements and anti-terrorism laws that they believe unfairly target members of

their faith.” All of that constitutes a tinder box waiting to ignite, and into

that inflammatory vicinity came the largest daily newspaper in Denmark, the

conservative Jyllands-Posten, whose

culture editor had a point he thought needed making.

The Issues Being Aired

Flemming

Rose explained: “In mid-September, a Danish author went on the record as saying

he had problems finding illustrators for a book about the life of the Prophet

Muhammad. The [eventual] illustrator insisted on anonymity,” Rose continued,

giving the reasons for the illustrator’s trepidation: “Translators of a book by

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali Dutch politician who has been critical of Islam,

also insisted on anonymity. Then the Tate Britain in London removed an

installation called ‘God Is Great,’ which shows the Talmud, the Koran and the

Bible embedded in a piece of glass.” He might also have mentioned the 1989 death

threat against writer Salman Rushdie for his portrayal of Muhammad in his

novel, The Satanic Verses. His

Japanese and Italian translators were stabbed, the former, fatally; and his

Norwegian publisher shot. And then there was the murder a year or so ago of the

Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh, killed by an Islamic fundamentalist for harshly

criticizing fundamentalism.

“To me,” Rose went on, “all those

spoke to the problems of self-censorship and freedom of speech, and that’s why

I wrote to 40 Danish cartoonists asking them to depict Muhammad as they see

him. Some of the cartoons turned out to be caricatures because this is just in

the Danish tradition. We make fun of the Queen, we make fun of politicians, we

make fun of more or less everything. Of course, we didn’t expect this kind of

[violent world-wide] reaction, but I am sorry if some Muslims feel insulted.

This was not directed at Muslims. I wanted to put this issue of self-censorship

on the agenda and have a debate about it.”

Self-censorship is as inhibiting to

free speech as official censorship, and Rose wanted “to examine whether people

would succumb to self-censorship as we have seen in other cases when it comes

to Muslim issues.” The debate Rose hoped to start would, pretty clearly,

involve protesting the climate of intimidation surrounding Islamic concerns. At

first blush, it would appear that the device Rose chose to inaugurate the

debate proved so incendiary that discussion was impossible.

In picturing Islam’s revered

Prophet, the 12 cartoonists who responded to Rose’s call did exactly what they

should do if their object was to inflame the Muslim population. The traditions

of Islam prohibit artistic representations of any of the prophets—whether

Muhammad, Jesus, Moses, or Abraham. In some of the strictest branches of Islam,

not even the human form can be depicted. Such images, particularly of the

prophets, could lead to idolatry, which is specifically prohibited in the

Qu’ran. Islamic tradition on the matter, however, is not as iron-clad as those

who protested the cartoons would have us believe. Muhammad has appeared through

the centuries in hundreds of paintings, drawings and other imagery both in the

West and in Islamic countries without a word of complaint in the Muslim world;

some of these, from Persian miniatures to the present, can be seen here: http://www.zombietime.com/mohammed_image_archive/ Images of Muhammad and other sacred persons

similar to Orthodox Christian icons are commonplace in Shi’ite communities,

particularly in Iran, according to a blogger named Soj, who goes on to say

“there are also Muslim works of art depicting Muhammad in Central Asia, and

neither these nor those in Iran are considered inflammatory.” Nor are they

censored. Perhaps the current outrage arises, as much as anything, from the

fact that the Danish Dozen are cartoons, cartoons traditionally being comical

and instruments of ridicule. Anything “cartooned” is therefore belittled,

diminished. In the case of the Prophet, a highly blasphemous act. But, says

Soj, unflattering pictures of the Prophet have appeared in the West for years,

beginning with Christian churches and illustrations for Dante’s Inferno and

culminating with derogatory images in tv’s “South Park.” And yet, “there’s been

no rioting, storming of embassies or CNN coverage.”

Nor was there this time. Not at

first, anyway. At first, apparently the only objections to the cartoons came

from the Danish Muslim community shortly after the publication of the 12

cartoons on September 30. Some of them played off the violence lately committed

in the name of Islam. One shows Muhammad wearing a turban shaped like a bomb

with its fuse smoldering. In another, Muhammad stands on a cloud in Heaven,

saying to the newly arriving, freshly deceased suicide bombers, “Stop! Stop! We

have run out of virgins!” (Now, that’s funny.) Another shows a bearded,

turbaned peasant in the desert, leading a donkey. (Not funny, and not

particularly well drawn, either.) In one, the cartoonist depicts himself at a

drawingboard, furtively drawing Muhammad. Another image is merely a visual

symbol, using the Islamic crescent and star to form Muhammad’s face around. All

twelve can be seen here, http://face-of-muhammed.blogspot.com/ or www.brusselsjournal.com/node/698

How the Outrage Spread

In

the Western tradition of political cartooning, nothing in any of the images is

particularly alarming, but to Muslims, the images are not only blasphemous, but

highly insulting to the most holy of Islam’s sacred personages. Moreover, they

reinforce a dangerous confusion in the West between Islam and the Islamist

terrorism that nearly all Muslims abhor. Still, it wasn’t until October 20 that

an official objection surfaced. The ambassadors in Denmark from eleven Muslim

nations signed a letter of protest sent on that date to the Danish prime

minister, but he said he could do nothing: in a country that promotes freedom

of the press, he pointed out, “I have no tool whatsoever to take actions

against the media—and I don’t want that kind of tool.”

The newspaper initially refused to

apologize, citing its long-standing policies: “We must quietly point out here

that the drawings illustrated an article on the self-censorship which rules

large parts of the Western world. Our right to say, write, photograph and draw

what we want to within the framework of the law exists and must endure—

unconditionally!” Editor Carsten Juste added: “We live in a democracy. That’s

why we can use all the journalistic methods we want to. Satire is accepted in

this country, and you can make caricatures. Religion shouldn’t set any barriers

on that sort of expression. This doesn’t mean that we wish to insult any

Muslims.” But, he concluded, “if we apologize, we go against the freedom of

speech that generations before us have struggled to win.” At about the same

time as the ambassadorial protest, an Islamic group called Holy Brigades in

Northern Europe threatened terrorist retaliation.

The prime minister, while resolutely

defending the independence of the Danish press, explained to the Muslim

ambassadors that they were not without recourse. “Danish legislation prohibits

acts or expressions of a blasphemous or discriminatory nature,” he wrote. “The

offended party may bring such acts or expressions to court, and it is for the

courts to decide in individual cases.” The embassies evidently applied to the

courts on November 1. A spokesman for the group said: “We have based our action

on the article that the drawings were published alongside, and the intention of

the article. We believe that it was the newspaper’s intention to mock and

ridicule.” The article warned Danish Muslims to br prepared for insult,

mockery, and ridicule. Apparently nothing came of this legal supplication. And

by then, the Danish cartoonists were in hiding, having received death threats,

and the Danish prime minister had introduced a bill to stiffen penalties for

those convicted of threatening and harassing people who, in the exercise of

their legal rights, make statements about such topics as religion. “That’s

unacceptable,” he said; “we want to protect freedom of speech in Denmark.”

By mid-November, the contagion was

spreading to Muslim nations. Protest was beginning to gather momentum. Other

motives started adhering to the protest, and even more sinister developments

were afoot. According to a blog by Dennis Rennie, European correspondent for

Britain’s Daily Telegraph, a

“delegation” of Danish Muslims made several trips to the Middle East in

December to circulate a 43-page green-covered “dossier” on “Danish racism and

Islamophobia.” They met with scholars, Arab League officials, and senior

clerics in Cairo and Beirut. The dossier contained the original 12 scabrous

cartoons and at least three more, these, profoundly offensive. Muhammad is

depicted in one with a pig’s snout; in another, as a pedophile demon. A third

cartoon showed a dog raping a praying Muslim. These cartoons were included in

the dossier because they had been sent to Muslims who had complained publicly

about the original 12 in Jyllands-Posten.

Rennie interviewed one of the “delegation,” its purported leader, Ahmed Akkari,

a devout man of 31, who denied that the inclusion of these extra cartoons was

intended to exacerbate Muslim ire against the Danish newspaper: he maintained

that this salacious trio was always expressly identified as not being among the

cartoons the paper published. And in the dossier, they were supposedly

separated from the original dozen by pages of letters and other contents. They

were included as examples of racist images that were circulated in Denmark,

thereby supplying “insight in how hateful the atmosphere in Denmark is towards

Muslims.” Akkari’s hope was that the religious leaders to whom he showed the

dossier would combine to bring international pressure to bear on the Danish

government to apologize for the blasphemy committed in one of the nation’s

newspapers.

The provocations advertised in the

dossier received a little “official” help, too, from Muslim governments. In

Egypt where the government had cracked down on the Muslim Brotherhood in the

weeks leading up to the national elections, the Mubarak regime apparently

decided it could divert attention from its own abuses of power by posing as

defenders of Islam abroad. Egypt’s foreign minister branded the Danish cartoons

as a scandal and launched a multi-national effort to prevent recurrence of such

insults to Islam. In Iraq, a Shi’ite newspaper demanded an apology from Jyllands-Posten. In Pakistan,

fundamentalists reportedly offered a reward of 500,000 rupees ($8,333) to

anyone who killed the cartoonists. It was beginning to get out of hand.

Islamist Radicals Take Up the Cause

In

Mecca at about the same time Akkari’s green-covered dossier was making its

rounds, the leaders of the world’s 57 Muslim countries gathered for their

regularly scheduled summit meeting. By this time, the Danish Dozen were widely

enough known that a closing communique expressed “concern at rising hatred

against Islam and Muslims and condemned the recent incident of desecration of

the image of the Holy Prophet Muhammad in the media of certain countries” as

well as “using the freedom of expression as a pretext to defame religion.” The

summit, according to Hassan M. Fattah writing in the New York Times, was “a turning point.” Anger at the images became

more public, and in Middle East countries, government controlled press coverage

“virtually approved demonstrations that ended with Danish embassies in flames.”

What was initially a popular “visceral reaction” provided the avenue to another

objective: it gave autocratic Muslim governments a popular movement to

sympathize with and to join in, hoping to “outflank an growing challenge from

Islamic opposition movements” by appearing to be the defender of the Faith.

In the first weeks of January, 2.5

million Muslims made the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, the Hajj. Doubtless, they

all heard there about the Danish cartoons, and they took their smoldering

outrage home with them. By mid-January, Muslim anger had turned to fury and

erupted, widespread and vicious. Protesters in the Arab streets were calling

for beheadings. According to blogger Soj, the Hajj was responsible for Saudi

Arabia getting into the act, further inflaming Muslim anger. Soj points to the

incompetence of the Saudi government in managing the crowds in Mecca. On

January 12, he says, 350 pilgrims were trampled to death in a “stampede.” Such

tragedies have happened before, Soj said: in 2004, 251 were killed in the same

area of the city. “These were not unavoidable accidents; they were the results

of poor planning by the Saudi government.” In 2004, the Saudis had vowed that

they’d correct whatever deficiencies existed so it wouldn’t happen again; they

apparently didn’t. And to divert attention from their negligence, the Saudi

government began running up to 4 articles a day in the state-controlled

newspapers condemning the Danish cartoons and calling for a formal apology from

Denmark. “When that was not forthcoming,” Soj said, “they began calling for

world-wide protests.” And that is just about the time that protests increased

in fervor throughout the Muslim world, attracting the attention, at last, of

the American tv news media, ever on the alert for exciting footage.

On January 26, according to Fattah,

Saudi Arabia made a “key move”: it recalled its ambassador to Denmark. And

Libya followed suit. “Saudi clerics began sounding the call for a boycott, and

within a day, most Danish products were pulled off supermarket shelves.” Fattah

quotes a Cairo political scientist, who said: “The Saudis did this because they

have to score against Islamic fundamentalists.” The fundamental Islamists were

gaining in power because of Muslim anger over the occupation of Iraq and “the

sense that Muslims were under siege.” Out of dissatisfaction with the status

quo, Muslims who participated in elections were voting for Islamists. In order

to outflank them, the established governments adopted an Islamic posture on the

Danish Dozen.

Chip Beck, an American political

cartoonist, former Marine and CIA operative, has spent many weeks in Iraq at

various intervals since the U.S.-led invasion and has some familiarity with the

Islamic world. Said he on one of the List Serves I subscribe to: “The rage is

not surprising, but I have to smile at the hypocrisy of the ‘audience.’ A couple of years ago, before I went to

Iraq, I was following cartoons that appeared in the Arab and Muslim press,

Internet, etc. On any given month, perhaps a thousand cartoons appeared around

the world that showed not only Americans, Europeans, and Israelis in harsh—even

nasty, maniacal—light, but made direct attacks on Jews and Christians. I don't recall seeing specific attacks on

Jesus (or Issa as he is called in Arabic), but certainly the religious symbols

of Christianity and Judaism were employed and offended. In strict Islamic

terms, it is a sin to depict any human, not just the Prophet Muhammad (praise

be his name) ... so there's a lot of professional cartoonists out there in the

Islamic world sinning up a daily storm. The only reason the God of the Jews and

the God of the Christians is not attacked the same way the Jews and the

Christians are, is because that God is the same one of Islam. Yet the

mean-spiritedness of the anti-Jewish, anti-Christian attacks would be

considered blasphemous as well, at least in some scholarly quarters, because

they attack ‘people of the Book’ and the ‘sons of Abraham (Ibrahim).’ [The

“people of the book” were afforded special protection by Muhammad.] My feeling

is that the outrage is driven behind the scenes by a political machine, not a

religious one. Religion in the

terrorist camp is just a tool, the same way the Soviets used the proletariat to

hide their true agenda.”

Since Muslims are apparently not

protesting the anti-Semitic cartoons in Arab newspapers in the Middle East, we

must conclude that the Bush League has been hugely successful in exporting to

that region the essence of American politics, hypocrisy. But there’s plenty of

hypocrisy to go around. In April 2003, Jyllands-Posten reportedly refused to publish cartoons about the resurrection of Christ on the

grounds that they could be offensive to readers and were not funny. In this

country, Abdul Malik Mujahid, chairman of the Council of Islamic Organizations

of Greater Chicago, spotlighted the essential double-standard by wondering

whether an anti-Semitic cartoon or one showing the Pope in a compromising

sexual position would have been tolerated in Europe the way the cartoons of the

Prophet were by those who published them.

Protest Gets Organized

Whether

or not the Saudis or the Egyptians hitch-hiked on outrage in the Arab streets

for their own purposes, it’s clear that the protests quickly moved beyond

spontaneous demonstrations of popular opinion. Radical Islamists pretty quickly

seized upon Muslim displeasure over the Danish Dozen for their own

purposes—namely, to foster hatred for the West and modernity. In Beirut on

Sunday, February 5, reported Rory McCarthy of the Guardian, “heavily-laden coaches and mini-vans” drove down to the

seaside Corniche and disembarked their passengers, “young, often bearded men

who wore headbands and carried identical flags with calligraphic inscriptions

in Arabic such as, ‘There is no god but God and Muhammad is his Prophet’ and ‘O

Nation of Muhammad, Wake Up!’ There were soon as many as 20,000 of them filling

the streets.” The crowd grew restive, then fierce, and before the day was over,

they marched on the Danish embassy and set it ablaze. “Then,” McCarthy

continued, “in the afternoon, as suddenly as it had all begun, it ended. The

leaders of the mob turned to the angry young men beside them and told them it

was time to leave. Obediently, the crowd thinned out and began walking back to

the buses.” And so the culture war, fueled by political extremists and

religious fanatics, turned again into a real war.

Elsewhere in the Muslim world,

beginning in Indonesia, other Danish embassies were attacked, and Danish

products were boycotted. When the European Union offices in Gaza were targeted,

men handed out pamphlets warning Denmark, Norway, and France that they had 48

hours to apologize. Said one Muslim protester in London: “We don’t know why

these silly people use these cartoons unless they were showing how much they

hate us. We have to defend our Prophet otherwise Allah will punish us. We will

not accept this ridicule.” In Copenhagen, Egypt’s ambassador said, “The

government of Denmark has to do something to appease the Muslim world.”

According to Condoleezza Rice, Syria and Iran were the chief culprits in

fomenting unrest. And they might be, although the Bush League’s agenda—to

inspire enough American outrage about these two countries to justify making war

on them—makes any assertion from the White House environs suspicious. But it’s

hard to deny the likelihood that some of those 20,000 protesters in Beirut came

from Syria. And Iran scarcely has clean hands: the Iranian daily newspaper Hamshahri decided turn-about was fair

play and launched a competition to find the best cartoon about the Holocaust,

saying the objective was to test the limits of free speech. In democratic

Copenhagen, Flemming Rose offered to publish any cartoons submitted in the

contest.

Islamic critics charged that the cartoons were a deliberate

provocation and an insult to their

religion designed to incite hatred and polarize people of different faiths.

Defenders of the newspapers and artists said the cartoons simply intended to

highlight Islam’s intolerance. While the protests reflect the Arab suspicion

and distrust of the West, the behavior of Islamic extremists seem to bear out

the accuracy of the charge of intolerance. The West may have lost its sense of

the sacred, but Muslims lost their sense of humor.

So did Jeff Jacoby at the Boston Globe: “The current uproar

illustrates yet again the fascist intolerance that is at the heart of radical

Islam. ... Most of the pictures [cartoons] are tame to the point of dullness,

especially compared to the biting editorial cartoons that routinely appear in

the U.S. and European newspapers. ... That anything so mild could trigger a

reaction so crazed—riots, death threats, kidnaping, flag-burnings—speaks

volumes about the chasm that separates the values of the civilized world from

those in too much of the Islamic world. Freedom of the press, the marketplace

of ideas, the right to skewer sacred cows—militant Islam knows none of this.

And if the jihadists get their way, it will be swept aside everywhere by the

censorship and intolerance of sharia.”

At the end of January in Denmark,

the prime minister, while maintaining that the government could not apologize

on behalf of the newspaper, said that he, personally, “never would have

depicted Muhammad, Jesus or other religious character in a way that could

offend other people.” Jyllands-Posten also issued an apology while defending its right to publish: “The initiative

was taken as part of an ongoing public debate on freedom of expression, a

freedom much cherished in Denmark. In our opinion, the 12 drawings were sober.

They were not intended to be offensive, nor were they at variance with Danish

law, but they have indisputably offended many Muslims for which we apologize.”

The paper categorically rejected the charge that its intention had been to

launch a campaign against Muslims in Denmark and the rest of the world. Muslim

groups meet later in the day and declared that the apology was too “ambiguous,”

demanding a clearer apology. The same group, however, appreciated hearing the

prime minister’s sentiments.

Meanwhile, at the Cartoonist Rights

Network, Executive Director Robert Russell was most concerned about the fate of

the twelve Danish cartoonists. “It is not our position to make a judgment on

the merits of any particular cartoon,” he wrote. “We are concerned about the

safety and well being of the cartoonists who may have caused offense and may be

the victims of revenge, censorship, violence or threat of violence. ... The

global response to the twelve Danish cartoons is unprecedented in the history

of cartooning or, for that matter, the history of freedom of the press. Nowhere

nor at any time as the impact and power of editorial cartoons been so

unequivocally demonstrated, now not only in ink but in blood. Cartoonists

Rights Network is horrified that this issue has turned so violent.” He vowed to

keep abreast of developments. As far as I know, the cartoonists are still where

they were two months ago—in hiding.

Freedom of the Press Asserts Itself

Meanwhile,

throughout Europe, newspapers began reprinting the Danish Dozen in support of

the general principle of freedom of the press. As of February 9, newspapers in

sixteen countries had joined in a demonstration of solidarity. In Germany, the

daily Die Welt published one of the

drawings on its front page and said the “right to blasphemy” is one of the

freedoms of democracy. In Paris, the legendary daily France Soir covered its issue printing the Danish cartoons with a

cartoon of its own, depicting Muhammad beside Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist

holy figures. The Christian God says, “Don’t complain, Muhammad, we’re all

being caricatured here.” The managing editor was fired immediately by the

paper’s owner, an Egyptian-born Catholic. Le

Monde, the influential French daily, ran an editorial asserting that French

law permitted religions to be “freely analyzed, criticized and even subjected

to ridicule.”

Fairly soon, most papers that

reprinted the cartoons enjoyed another benefit: increased sales. The

circulation of France Soir, in

financial straits and up for sale, increased by 40 percent on the day it

published the cartoons. The Associated Press’s Jamey Keaten quoted the ironic

remarks of the vice president of the French Council of the Muslim Faith, who

said: “Here’s some advice to those newspapers today facing ruin, bankruptcy or

collapse: all you need to do is insult Muslims and Islam, and sales will get

hot as blazes.”

In England, the Daily Telegraph, which elected not to reprint the cartoons, was

nonetheless firm in asserting its right to do so: “The right to offend within

the law remains crucial to our free speech. Muslims who choose to live in the

West must accept that we, too, have a right to our values, and to live

according to them. Muslims must accept the predominant mores of their adopted

culture: and most do. One of these is the lack of censorship and the ready

availability of material that some people find deeply offensive. Those Muslims

who cannot tolerate the openness and robustness of intellectual debate in the

West have perhaps chosen to live in the wrong culture.”

The Guardian agreed. “If free speech is to be meaningful, the right to

it cannot shirk from embracing views that a majority—or a minority—finds

distasteful. ... But that is not the end of the matter. There are limits and

boundaries—of taste, law, convention, principle or judgment. ... The right to

publish does not imply any obligation to do so. ... Every newspaper in the

country regularly carries stories about child pornography, yet none has yet

reproduced examples of such pornography as part of their coverage. Few people

would argue that it is essential to an understanding of the issues that they

should do so.” The Guardian did not

question the right of the Danish paper to publish the cartoons, but “it is

another thing to put that right to the test, especially when to do so

inevitably causes offence to many Muslims and, even more so, when there is

currently such a powerful need to craft a more inclusive public culture which

can embrace them and their faith. That is why the defiant republication of the

cartoons in ... Europe ... is more questionable than it may appear at first

sight.” The restraint of the British press may be the wiser course, “at least

for now. There has to be a very good reason for giving gratuitous offense of

this kind.”

In the U.S., at first only the New York Sun reprinted the cartoons. The

reticence reflected a reluctance to exploit the sensationalism inherent in the

situation, but as the controversy abroad swelled and spread , the imperative to

reprint grew. The Inquirer in

Philadelphia finally decided to publish the most inflammatory image. Editor

Amanda Bennett said good journalism required them to publish: as the

controversy persisted, people needed to know what the fuss was all about. She

compared it to decisions in the past to publish photographs of the bodies of

burned Americans hung from a bridge in Iraq and to the 1989 photograph of an

artwork by Andres Serrano showing a crucifix submerged in a jar of urine. “You

run it because there’s a news reason to run it,” Bennett said. The day after

the cartoon’s publication, a dozen Muslim protesters peacefully picketed the

newspaper offices.

In Texas, the Austin American-Statesman ran one of the images. And so did the Daily Press in Victorville, California,

and the Tribune-Eagle in Cheyenne,

Wyoming, where the Muslim population is minuscule. Among tv networks, ABC and

Fox each showed one cartoon; NBC and CBS declined.

Opinions Galore

On

February 3, the U.S. State Department got officially into the act, spokesman

Kurtis Cooper saying: “These cartoons are indeed offensive to the belief of

Muslims. We all fully recognize and respect freedom of the press and

expression, but it must be coupled with press responsibility. Inciting

religious or ethnic hatreds in this manner is not acceptable.” A State

Department spokesman also said that cartoons about Muhammad are as

objectionable as the anti-Jewish cartoons that often appear in Arab newspapers.

Comic book legend Joe Kubert, founder and president of

the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art in New Jersey, took exception

to the statement. “Surely he should recognize that the Danish cartoons appeared

in independent newspapers which the Danish government cannot control. The

anti-Semitic caricatures in the Arab press are typically published in

newspapers over which their governments exercise complete control—and which

they could bring to a halt at any time, if they so chose.” And here is the

source of the Muslim exasperation that the Danish government doesn’t chastize Jyllands-Posten: in Muslim countries,

the press is a creature of the government; in Denmark, it isn’t. Muslims,

understandably, don’t believe that, or can’t understand it.

For its February 13 issue, Time mustered diverse opinions. A

Harvard law professor accused the U.S. news media of “giving in to intellectual

and religious terrorism. ... It is in the public’s interest to see these

cartoons that are causing so much outrage. When you see them, you see the

extent of the over-reaction. They are not nearly as bad as cartoons that

routinely run in the Muslim media against Jews, Christians, the U.S. and

Israel.” He and many free press advocates miss the central issue: it isn’t the

content of the pictures that is outrageous to Muslims; it’s the very existence

of a depiction of the Prophet.

An Indonesian said: “Why do you have

to insult somebody to assert freedom of the press?” The editor of a Moroccan

weekly said: “The cartoons are adding insult to injury. Not only are you

invading and robbing our lands; you are insulting our faith.” An unnamed Muslim

blog is quoted: “Yes, Arabs and Muslims are uptight when you touch their

religious or national symbols, but Europe had made of political correctness and

the cult of the Holocaust and Jew-worshiping its alternative religion, and they

get even more uptight when you touch that. Europeans might not respect their

flags, and they might laugh with Jesus and Mary, but if you touch their true

religious symbols, they will bombard you with indignation and persecute you in

the best European inquisition tradition.”

Tom Heneghan, religion editor at

Reuters, wrote: “The row over caricatures of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad resembles

a dialogue of the deaf, with many European spokesmen defending the right to

free speech and many Muslims insisting Islam must be treated with respect,”

adding, later, that “the word ‘respect’ repeatedly pops up in Muslim comments,

revealing how much the cartoons linking Muhammad and terrorism hurt the

feelings of people who feel humiliated by the West. ... Respect was the main

issue for Muslims outraged by the images they consider blasphemous. ‘It’s all

about creating a culture of respect, of wanting to live together under the roof

of a plural citizenry,’ said Mohamed Mestiri, head of a Parisian Islamic

philosophical institute. ... the cartoons [are] the latest in a history of

Western affronts to Muslims, who, only in recent years, have mustered enough

political clout to fight back.”

In Newsweek for February 13, Fareed Zakaria, whose opinion columns I

find unusually thoughtful and wise for a general circulation periodical, was

writing about the future for democracy in the Middle East, but he paused to use

the Danish Dozen to make a rhetorical point: “The cartoons were offensive and

needlessly provocative. Had the paper published racist caricatures of other

peoples or religions, it would also have been roundly condemned and perhaps

boycotted. But the cartoonists and editors would not have feared for their

lives [as they presently do]. It is the violence of the response in some parts

of the Muslim world that suggests rejection of the ideas of tolerance and

freedom of expression that are at the heart of modern Western societies.”

According to Craig S. Smith and Ian

Fisher in the New York Times, “Most

European commentators concede that the cartoons were in poor taste but argue

that conservative Muslims must learn to accept Western standards of free speech

and the pluralism that those standards protect.” In fact, I didn’t see much in

this vein—or hear it, either, once the uproar reached the broadcast medium.

Most discussions seemed to center on what Westerners should do to accommodate

Muslim sensitivities. But it seems to me that this is a two-way street. And I

found agreement in U.S. News and World

Report for February 13, which quotes Tariq Ramadan, a Swiss-born Muslim and

philosopher teaching at Oxford, who said both sides need to learn some hard

truths about living together in the world. Free-speech advocates must recognize

that Muslims view the depiction of their Prophet as blasphemy. They also have

to realize that Muslims come out of cultures unaccustomed to the ridiculing of

their religion. “On the other side,” he continued, “Muslims should know that

for the last three centuries in Europe ... there has been an acceptance of the

cynical and ironic treatment of religious issues and people.” High-minded sentiments,

said reporter Jay Tolson. “But Tamadan admits that polarized climate makes it

unlikely that either side will soon be making concessions.” Alas, true, I

suspect.

Cartoonists Speak Out

One

editoonist on the AAEC List Serve said: “It seems to me that the Danish cartoon

issue is the same thing to freedom of the press that shouting ‘fire’ in a

crowded theater is to freedom of speech. Just as there must be a good reason to

shout ‘fire,’ there should have been a better reason—not to mention better cartoons—to

print the cartoons in question.” Garry

Trudeau, no stranger to controversy, said he would never use images of

Muhammad. “Nor will I be using any imagery that mocks Jesus Christ ... I may

not agree with [an editor’s] reasons for dropping any particular [Doonesbury] strip, in fact, I usually

don’t, but I will defend their right and responsibility to delete material that

they feel is inappropriate for their readership. It’s not censorship,” he

declared; “it’s editing. Just because a society has almost unlimited freedom of

expression doesn’t mean we should ever stop thinking about its consequences in

the real world.”

In a press release, Joe Kubert marveled that “an art form

sometimes mistakenly assumed to be less than serious [could have] triggered [such]

a deadly serious reaction.” He then went on to acknowledge “a truth about

political cartoons ... that they are one of the most powerful forms of

communication” and cited several cases in American history where cartoons have

shaped events, resulting, in several states, in “angry politicians ...

introducing legislation attempting to restrict what cartoonists could draw.”

Such laws, he noted, were eventually repealed. He expressed alarm, however,

that in the wake of the riotous objection in the Muslim world some voices have

been raised to propose restrictions on cartoonists and editors with respect to

religious matters. “Censorship would be a mistake,” Kubert said. “It would give

any religious group veto power over the cartoons—or writings, or speeches—of its

opponents.” Artists sometimes produce offensive works, “but that does not

justify rioting or censorship,” he said. “In a civilized society, people

respond to offensive art by refraining from entering the museum in question or

buying that particular paper. ... Western leaders need to say clearly that

while Muslims may find the cartoons offensive, the violent response to the

cartoons is absolutely unacceptable. Establishing the ground rules for how to

conduct a civilized debate, not searching for ways to appease the angry mobs,

should be our goal. Surely we must strive to live in a world governed by reason

and civility, rather than one in which cartoonists or their editors must fear

for their lives.”

At the Cartoonist Rights Network,

Executive Director Robert Russell was most concerned about the fate of the

twelve Danish cartoonists. “It is not our position to make a judgment on the

merits of any particular cartoon,” he wrote. “We are concerned about the safety

and well being of the cartoonists who may have caused offense and may be the

victims of revenge, censorship, violence or threat of violence. ... The global

response to the twelve Danish cartoons is unprecedented in the history of

cartooning or, for that matter, the history of freedom of the press. Nowhere

nor at any time as the impact and power of editorial cartoons been so

unequivocally demonstrated, now not only in ink but in blood. Cartoonists

Rights Network is horrified that this issue has turned so violent.” He vowed to

keep abreast of developments.

In Australia, a couple cartoonists

spoke up, both advocating publication of the cartoons in the name of free

speech, but one, Bill Leak, said he

objected to the Danish Dozen chiefly on artistic grounds: “I think they’re

deeply unfunny and very badly drawn.”

In Europe, many German political

cartoonists have condemned the cartoons depicting Muhammad as a terrorist. One

publication called them defamatory and not worth defending. French cartoonists

were similarly disposed. Said Rene

Petillon, who cartoons for the weekly satirical newspaper Le Canard Enchaine: “Such a cartoon

directly associates one religion with terrorism, and this is unacceptable.” At

the same time, he acknowledged that “freedom of expression is non-negotiable.”

Petillon has just published a comic book depicting Muslim fundamentalists in

France as small-minded machos who terrorize their women. Entitled The Headscarf Affair, the book refers to

France’s 2004 ban on Muslim headscarves in public schools and stars a hapless

detective who is hired to find a wayward Muslim teenager who has converted to

militant Islam. “My aim was to criticize the Islamists,” said the cartoonist,

“especially their attitude towards women. The main idea is to make people

laugh. In a modest way,” he said, “I’m calling for more understanding and

dialogue.” The book has been well-received so far, he said, becoming a

bestseller in a very few weeks and earning the praise of a well-known Muslim

feminist and of the head of the French Muslim Council, who said its portrayal of

arcane theological disputes in Islam is both accurate and amusing. Petillon,

who has a penchant for ridiculing the powerful and the pious, has lampooned his

own strict Catholic upbringing in an earlier comic book and made Corsican

nationalists laugh at themselves in another. “What’s troubling about the Danish

affair,” he said, “is that it helps the fundamentalists rally people to their

cause.”

Patrick

Chappatte, a cartoonist quoted in the Swiss newspaper Le Temps, said: “The reaction in Muslim countries shocks me because

it confirms the weight that radical Islam has acquired. A real totalitarianism

is at work in the world and wants to impose its views not only on Arab Muslims

but on the West. The same way that they veil women, Islamic radicals want to veil

cartoons in the press.”

The Association of American

Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) issued a

statement that emphatically supported freedom of expression and, while

expressing sympathy for the Islamic sensibilities, condemned without reservation

violent protest and called for both sides in the current situation “to raise

the level of the debate and not just the level of invective. All would be

well-served to realize that they can stand up for their beliefs without

trampling on others to do so.” The complete text is at http://editorialcartoonists.com/index.cfm

Gadfly ’tooner Ted Rall, my favorite trouble-maker, foamed at the keyboard for

absolute no-holds-barred, nothing-held-back freedom of the press at http://www.tedrall.com/ Click on “Columns” and then look for “The Nanny Press and the

Cartoon Controversy,” dated 2/7/06.

Editooner Doug Marlette, who has some experience with Muslim outrage over his

cartoons (see Opus 127), rejects the idea that Westerners ought to make special

concessions to sensitive Muslims: “The genius of Western democracy is that

there should be no ‘special’ rights of privileges for any group of class of

people. All are created equal and are treated equally under the law. Law is

insensitive that way. And so is intellectual inquiry. And so is good satire.”

To

which columnist Kathleen Parker said: “None of us likes it when our icons are

busted, or our revered symbols ridiculed. But we tolerate offense in the spirit

of larger freedoms under rules that have sustained us for centuries. What we

have learned over time is that free expression is society’s relief valve,

without which aggression and hostility go underground. What eventually bubbles

back up to the surface is the sort of spirit that drives today’s jihadists.

Better to air and view our disagreements by the light of day—in the public

forum—rather than wait for them to find expression by darker means. As Marlette

puts it: ‘Our ability to engage in vigorous debate and to tolerate robust

intellectual discourse and all the attendant controversies is a measure of the

health of society.’” And, I might add, of the maturity of that society—that is,

of its ability to handle diversity without going all to pieces.

A goodly number of the American

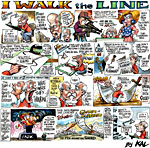

editoonery brotherhood did their commenting in the usual form, pictures. KAL did a full-bore 2/3 page comic

strip in color for the Washington Post and seems to me to have captured the dilemma for cartoonists as well as for the

rest of us.

One Picture, A Thousand Outcries

By

Signe Wilkinson, February 7, 2006

As

someone who has been picketed and protested for her blasphemous, insensitive,

anti-Islamic cartoons, I have nothing but sympathy for my Danish colleagues who

have incurred the wrath of the godly by publishing a portfolio of cartoons

making fun of one of the world's great—but apparently humor-impaired—religions.

However, I also have compassion for the members of humor-impaired religions.

After all, I am a Quaker.

It's been my experience that most

groups are humor-impaired when outsiders make fun of them. On MSNBC.com,

readers were asked to vote on whether they thought the Muslim protests were

justified. The vote was running 82 percent against the Muslim reaction when I

checked Thursday night.

But let's just change the image.

What if it were a cartoon showing someone burning the American flag? What if it

were a depiction of Jesus with a smoking shotgun as a comment on Christians

shooting abortion doctors? What if it were the Star of David used as a hoop

that a politician must jump through to get elected?

I'm guessing the approval rating

would plummet. Actually, I don't need to guess because at various times in my career

I've penned (and my newspaper has published) cartoons along those lines. Lack

of humor ensued after each one. A number of my cartoons have caused boycotts,

lost advertising for my newspaper, and elicited streams of phone calls and/or

picketing in front of our building.

My editors have had to explain the

nature of cartooning to the offended representatives of various faiths,

ethnicities, and political groups. And I am not alone. Nearly all cartoonists

worth their salt have enraged some portion of their readership, often when

religious symbolism was part of the cartoon. While at least one colleague

received death threats, most of the ensuing protests are loud, sometimes

intimidating, but generally peaceful. I don't go out of my way to poke fun at

the religiously faithful. I have no grounds to criticize other religions, when

my own is such a quirky (though perfect) little cult. Unfortunately,

cartoonists are easily bothered. I am particularly bothered when some group

wants to impose its way of life on me—and most particularly when its adherents

want my tax dollars to help them do the imposing. Religious groups are often

among those asking for tax dollars, or particular laws to advance their

interest or legalize their morality.

As the editor of the French newspaper France Soir noted after publishing

the Danish cartoons, if we were to abide by all the rules of all the world's

religions, we wouldn't be allowed to do much of anything.

I'll risk being called anti-Muslim

to do my job

This said, readers should know that

cartoonists working for mainstream American newspapers—and there are more than

80 around the country—generally try to avoid negatively caricaturing any group

just to make fun of them. American history is filled with examples of published

images that would not run in newspapers today, our most egregious sin being the

racist portrayals (without comment) of black Americans in cartoons,

advertising, and illustrations. As the civil-rights movement revealed the

injustice behind those racist images, those cartoons went from being humorous

to hideous.

Blacks weren't alone in trying to

influence how they were portrayed in popular culture. Long before 9/11,

Arab-Americans asked for cartoonists to be more sophisticated in their

depiction of Middle Easterners. Early in my career, I received a heads-up from

an Arab-American group pointing out that all Arabs aren't head-scarf-wearing

sheikhs.

At several of The Association of

American Editorial Cartoonists conferences, representatives from Jewish,

Latino, Arab, and other ethnic groups pled for relief from what they saw as

derogatory stereotypes that we cartoonists routinely used as shorthand.

Our images have changed over the

years, though many of us still draw sheikhs with scarves because they feature

prominently in the news. If you wear dresses and scarves, cartoonists are going

to draw you with dresses and scarves. But I think if you did a study—and I

haven't—you'd find that more cartoons about the Middle East now feature Arabs

who more resemble an American teenager at a mall.

Of course, sheikhs get to choose

what they wear. Many women in Islamic societies don't. My encounters with

Muslims have mostly come over cartoons protesting the treatment of Muslim

women. After one such cartoon, a local woman called me to defend the headscarf.

I said I had no problem with anyone freely wearing a headscarf or any other

religious outfit. I then asked her, "But you wouldn't force other women to

wear a headscarf, would you?"

After a pause she replied,

"Well, if it was for her own good."

So there you have the reason I go to

the drawing board every day. I am drawing to help prevent a world where someone

else decides what I must wear for my own good. And, I'm willing to risk being

called anti-Muslim to do it.

I'm guessing the Danish cartoonists

were trying to do the same thing. The cartoons were criticizing violence and

suicide bombing in the name of Islam. The cartoonists have the right to

publish. And, in a free society, Muslims have a right to protest and publish

their own cartoons in response. This is not a right granted to cartoonists or

protesters in some Muslim countries.

I hope Muslims will come to know

that they aren't the first, and won't be the last, to be offended by a

political cartoon. I know cartoonists will take into consideration the reaction

to this caricature when drawing their next ones on Muslim issues. If the

reaction of the "Arab street" continues to be violence whenever they

don't like something they see in someone else's newspaper, then I predict more

such cartoons are on the way. My suggestion is that instead of threatening to

draw blood, Muslims should pick up their pens and draw return cartoons instead.

Wilkinson

is one of America's few contemporary women editorial cartoonists. She was the

first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1992. She

regularly contributes to Organic Gardening magazine, the Institute for Research on Higher Education, and

Oxygen.com, and is the author of One Nation, Under Surveillance.

As For Me, Your Hoppy Obedient Servant

I

support the freedom of the press to publish cartoons, regardless of their

import. The press is either free or it isn’t; there aren’t degrees of freedom.

The question with respect to the Danish Dozen, however, is: What was the

comment that they were making? Was it worth making? The question any editor

must ask about a cartoon or prose opinion comment is: Will it provoke thought

or mindless outrage based upon a misunderstanding? That, it seems to me, is a

legitimate question. If the outcry overshadows the comment, then the cartoon

has destroyed itself. Every editorial cartoonist wants to be provocative. But

if the provocation diverts attention from the issue being examined, what’s been

gained? So the next question about the Danish Dozen is: What was the issue that

the cartoonists addressed? And do the cartoons make insightful comment on the

issue?

I

feel that if a cartoon provokes more hostility than thought, it's crossed the

line and defeats its purpose. Few people can think clearly in the white heat of

outrage. Cartoonists must have the right to cross the line, no question, and in

the case of the Danish Dozen, they clearly did, so was the purpose of

publishing the cartoons therefore frustrated? For some of the cartoonists, the

purpose was to suggest that terrorists found their actions condoned, even

encouraged, in Islam. These cartoons misfired: no one is talking about the

Islamic roots of terrorist strategies. So at first, I thought the basic

objective of the drill had been frustrated, that the message of the cartoons

was obliterated by the fuss they incited.

And

then, studying the matter further as I wrote this piece, I decided it hadn’t.

The cartoons that connected terrorism to Muhammad failed, but not all of the

cartoons aimed at that target. The reason the Jyllands-Posten commissioned and published the cartoons was to

protest a dangerous timidity in the news media that was being promoted through

intimidation by Muslim extremists. Rose, remember, said he “wanted to put this

issue of self-censorship on the agenda and have a debate about it.” Believing

that self-censorship is as inhibiting to free speech as official censorship,

Rose wanted “to examine whether people would succumb to self-censorship as we

have seen in other cases when it comes fo Muslim issues.” The debate Rose hoped

to start would, pretty clearly, involve protesting the climate of intimidation

surrounding Islamic concerns. At first blush, it would seem that the device

Rose chose to inaugurate the debate proved so incendiary that discussion was

impossible. In short, it would appear that the hostility inspired by the

cartoons thwarted their purpose. But lately, as the smoke begins to clear over

the wreckage of Danish embassies in the Muslim world, it seems that the debate Rose

wanted to have is actually occurring on all sides. Feathers were ruffled,

feelings hurt, sensitivities ignored, property destroyed, and a dozen lives

lost, but the conflagration of opinion all around us would seem an unabashed

endorsement of the balls-on, all-out, wheels-up, publish-and-be-damned-to-you

free speech and unfettered press posture that Ted Rall so vividly champions.

And,

yes—I am rubbing my hands in joyless glee over this demonstration of the power

of pictures. At the New York Times,

Michael Kimmelman did the same, figuratively speaking. “Have any modern works

of art provoked as much chaos and violence as the Danish caricatures? ... But

there are precedents going all the way back to the Bible for virulent reactions

to proscribed and despised images. Beginning with the ancient Egyptians, who

lopped off the noses of statues of dead pharaohs, through the toppling of

statues of Lenin and Saddam Hussein, violence has often been directed against

offending objects, though rarely against the artists who made them. Educated

secular Westerners reared on modernism, with its inclination toward

abstraction, its gamesmanship and its knee-jerk baiting of traditional

authority, can miss the real force behind certain visual images, particularly

religious ones ... —a deep abiding fact about visual art, its totemic power:

the power of representation. This power transcends logic or aesthetics. Like

words, it can cause genuine pain. Ancient Greeks used to chain statues to

prevent them from fleeing. Buddhists in Ceylon once believed that a painting

could be brought to life once its eyes were painted. In the Netherlands in the

1560s, pictures were smashed in nearly every town and village simply for being

graven images. ... To many people, pictures will always, mysteriously, embody

the things they depict. Among the issues to be hashed out in this affair,

there’s a lesson to be gleaned about art: even a dumb cartoon may not be so

dumb if it calls out to someone.”

But

art is not our only concern in this affair. Robert Spencer, writing for

humaneventsonline.com December 14, noted the much larger implications of the

disturbance in Denmark: “[Freedom of speech] is imperiled internationally more

today than it has been in recent memory. As it grows into an international cause

celebre, the cartoon controversy indicates the gulf between the Islamic world

and the post-Christian West in matters of freedom of speech and expression. And

it may yet turn out that as the West continues to pay homage to its idols of

tolerance, multiculturalism, and pluralism, it will give up those hard-won

freedoms voluntarily.”

Similarly,

Joshua Micah Marshall at his blog, TalkingPointsMemo.com, looks stoically,

albeit glumly, I think, to an unwelcome future: “There’s something peculiarly

21st century about this conflict—both in the way that it’s rooted in

the world of media and also in the way that it shows these two societies or

cultures ... can’t interface. The gap is too large. The language too different.

One’s coming in at 30 degree angle; the other, at 90. ... Is it just me, or

does it seem that more and more often there are public controversies in which

‘blasphemy’ is considered some sort of legitimate cause of action—as if

‘blasphemy’ can actually have any civic meaning in a society like ours. ... An

open society, a secular society, can’t exist if mob violence is the cost of

giving offense,” he continued. “In any case, there is a hint of the absurd in

this story, the way continents of people get swept up in reaction to some

simple pictures. But this episode seems like a model for what I imagine we’ll

be living with for the rest of our lives.”

Meanwhile,

as of this writing on Saturday, February 11, riots continue, reason is a voice

crying in the wilderness, and Ahmed Akkari sits sadly in Copenhagen,

contemplating the chaos he believes his green-covered dossier caused. According

to Doug Saunders at the Toronto Globe and

Mail: “Friends, strangers and close family members blame him for exactly

the thing he says he was trying to prevent: the caricaturing of Muslims as

violent fanatics. The riots, he acknowledged, have placed his fellow European

Muslims in far worse position than before. ‘Yeah, it has been more violent than

I expected,’ he said. ‘I had no interest in any violence. ... It is bad for our

case because it’s turning the picture completely from what this should be about

to something else—and this is a dangerous change now.’ He never intended this

to be more than an internal Danish conflict, a technical matter—how to get the

government to acknowledge that something had gone wrong. ... The overseas trip

was planned only after the domestic campaign ran aground. ... He is horrified

to find that the Danish people—and he proudly considers himself a Dane—have

been demonized.”

OUT OF

SIGHT, OUT OF MIND

Just on the cusp of the furor over the Danish Dozen

appeared a cartoon by the Washington

Post’s Pulitzer-winning Tom Toles,

one of the nation’s most outspoken editoonists who now occupies the berth

hallowed by another of the best of the opinion mongers, Herblock. Toles’ cartoon on Sunday, January 29, was a reaction to a

remark by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who, a few days before, had

responded to a reporter’s question about whether the U.S. military was

over-extended in Iraq and elsewhere, but chiefly in Iraq. Rumsfeld denied the

allegation, saying that the Army was not stretched too thin: it was, he said,

“battle-hardened.” Here’s Toles’ cartoon, which you probably ought to take a

quick look at before going on with this diatribe. Reaction

from various points of the political compass was almost immediate. A few—and

only a few, as it turned out—were upset that the cartoon seemed a breach of

good taste, employing a quadruple amputee to make a political point. Political

cartoonist V. Cullum Rogers, long-time factotum of the AAEC, addressed this issue with devastating logic,

his usual weapon: “I go along with Oscar Wilde, who famously said, ‘A gentleman

is someone who is never unintentionally rude.’ Deliberate tastelessness

(blasphemy, fart jokes, profanity, personal insult—whatever) is like every

other arrow in our quiver. It should be employed when it’s appropriate to the

topic involved, when it’ll get the message across better than anything else,

and when it won’t defeat the cartoon’s purpose by creating a stink that drowns

out what the cartoonist was trying to say. Tastefulness is the ability to tell

which particular acts of tastelessness meet those criteria and which don’t. So

I’d say it’s pretty important, if only in a negative sense: without it, how can

you tell how effectively you’re deploying its opposite?”

Most

reactions to the cartoon were supportive. Some were appalled that senior

Pentagon officials would use their rank and status to express an opinion that

was essentially political. Because the letter would, regardless of its intent,

exert pressure on the paper, it was seen by some as an attempt at government

censorship, just another in the long tedious succession of Bush League attempts

at silencing opposition. Others were alarmed that this August group of military

leaders was so demonstrably incapable of seeing what most readers saw right

away in Toles’ cartoon. Clay Bennett, president of AAEC and editorial cartoonist at the Christian Science Monitor, observed wryly that “it appears the

Joint Chiefs interpret cartoons as accurately as they do pre-war intelligence.”

In a letter to the editor, Ronald M. Garrett of Morrisville, North Carolina,

wrote: “Whoever wrote the letter for the Join Chiefs knew that the cartoon

wasn’t about wounded soldiers. It was about rear-echelon political hacks who

dismiss the results of their foolish decisions, who never seem to learn from

their mistakes and who don’t seem to care that when they write a check, the

infantry signs it in blood.” Fred Hiatt, editorial page editor at the Post, defended Toles, saying: “I respect

the views of the Chiefs and of others who echoed their criticism, and I

understand their reaction. But I don’t agree with their reading of the cartoon.

(Nor, by the way, did many other readers, who wrote to support Toles or take

issue with the Chiefs.) I think it’s an indictment of Rumsfeld, who is

portrayed as callous and inaccurate in his depiction of the Army and its

soldiers. Whether that’s fair to the Defense Secretary is a separate question.

I don’t believe that Toles meant the cartoon to demean the soldiers themselves,

and I don’t think it did.”

Bennett,

quoted above, went on to say that the Joint Chiefs “should be as concerned with

the soldiers in the field as they are with a cartoon in the Washington Post. Maybe they should

provide the body armor soldiers need to help avoid the sort of injury shown in

the cartoon.” Toles, who declined to comment very extensively on the issue,

granted a short interview with “NBC Nightly News” and said substantially the same

thing as Bennett.

But

then, just as the issue was beginning to gather momentum, it disappeared.

Vanished. The media had another issue—the Danish Dozen. And with burning flags

and waving fists in the air on every Arab street, tv news had better pictures

than Toles and his cartoon. Toles was probably just as glad that press

attention was diverted: he pretty clearly prefers working at a drawingboard to

express his opinions, not at a microphone. His concerns, however, are shared by

less publicity-shy reporters, namely the redoubtable Seymour Hersh in The New Yorker, who noted recently that

“there are grave concerns within the military about the capability of the U.S.

Army to sustain two or three more years of combat in Iraq. Michael O’Hanlon, a

specialist on military issues at the Brookings Institute, noted ... that ‘if

the President decides to stay the present course in Iraq, some troops would be

compelled to serve fourth and fifth tours of combat by 2007 and 2008, which

could have serious consequences for morale and competency levels.’” But we’ll

probably never get to this discussion. As Hersh said, “The Administration has

‘so terrified the generals that they know they won’t go public,’” quoting a

former defense official. Not even Toles’ cartoon, it seems, helped. Before the

subject was completely overshadowed by Muslim rage, another of the editooning

brotherhood made a crucial observation, saying he was appalled “that the Joint

Chiefs effectively changed the subject. The media flap is now about the cartoon

and not about the wounded Iraq vets”—or troop levels. Well, maybe. That’s as

far as it went, surely. But had the controversy continued—had it not been blown

out of the water by the Islamic furies—it’s probable that some of the response

would have gotten around to the issue that inspired the cartoon, whether the

military could sustain prolonged combat in Irag. Toles’ cartoon missed its mark

not because of bad strategy or tastelessness; it was sheer bad timing that

caused the misfire.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a

kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv

The Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia has

developed a spray that can be applied to animal poop that effectively removes

the stink. Now that’s an advance in civilization. ... And, speaking of freedom

of the press, the New Times of San

Luis Obispo ran an article about how easy it is to make meth if one merely

dials up the right terms on the Internet. The paper listed the ingredients and

gave the recipe, having obtained, as it said, both on the ’Net. The outcry was

considerable among the paper’s readers, but the editor stuck to his guns,

maintaining that the chief reason for publishing the article was to demonstrate

how accessible the drug was in the Digital Age. Everyone’s home computer is the

corrupting culprit. The editor, it seems to me, used the same tactic that

Flemming Rose did: the idea was to publish something so inflammatory that

readers would be provoked into confronting a danger they were busily

overlooking. It can still be debated whether teaching people how to make meth

is any more dangerous a way to accomplish a journalistic goal than to enrage

the religious sensibilities of millions, worldwide. The trick, in this day of

multimedia overload, is to attract their attention.

The

“word of the year” for 2005 is “truthiness,” which means, the American Dialect

Society tells us, “the quality of preferring concepts or facts one wishes to be

true rather than concepts or facts known to be true.” The word has been

popularized lately on Comedy Central tv by Stephen Colbert, who has declared,

in the spirit of genuine truthiness, “I don’t trust books. They’re all fact, no