|

||||||||

|

Opus 166: Opus 166 (July 30, 2005). Featured this time are reviews of Paul Hornschemeier's Mother, Come Home, his

anthology of college material, Sequential,

and the 20th anniversary commemoration of Mother Goose and Grimm, plus a nearly unprecedented deviation in one

of the world's most popular comic strips, Blondie, and a long fond report on our reporter's recent visit to

England. In order, here's what's here (by department): NOUS R US -Trudeau's turd, the Spirit's new lease on life, the last

Cartoonist PROfiles, the fate

of Michigan J. Frog at WB, Jessica Alba loves the FF (I think), Superman

in Metropolis, Illinois, and Marvel at Niagara Falls; Ye Olde Merrie -earth-shattering events in the UK, lurid sex in the

famed tabloid press, British newspaper comics, the civilian body count

in Iraq, and a few stray thoughts about antiques;

Rowland B. Wilson's obit, Gene

Hazelton's cameo, review of Modern

Arf and a book of insightful essays on cartooning; 3 cartooners

who are "screwing up Bernard Goldberg's America," the evil

pointlessness of anonymous sources, Mike

Peters and Grimm, and Hornschemeier's

Mother. And once again, I see that I've

become carried away with my own prolixity, which makes our "Bathroom

Button" all the more essential: when you get to the Members' Section,

click on our useful "Bathroom Button" (also called the "print

friendly version") of this installment so you can print off a copy

of just this installment of Rancid Raves for reading later, at your

leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu-

NOUS R US Doonesbury for July 26 and 27 was pulled by 10-12 newspaper editors

because the strips employed a Presidential Nickname for Karl Rove. In

one of Garry Trudeau's talking

White House sequences, the unpictured personages (presumably GeeDubya

and an aide) are discussing the "Rove revelations" about leaking

Valerie Plame's CIA assignment, and the Presidential speech balloon

says, "Karl's sure been earnin' his nickname lately." Other

speaker: "Boy Genius? I'm not so sure, sir." The Presidential

balloon then calls out: "Hey, Turd Blossom! Get in here!"

A couple papers altered the language to eliminate the fecal reference,

and that raised Trudeau's ire. Said he: "Editors obviously have

a responsibility to determine what's appropriate for inclusion in their

papers. [We] accept that from time to time individual editors may object

to particular strips and decide to drop them. What's not acceptable

to us, however, is for editors to alter the content of a strip and represent

it as what I sent them. In most cases, changing the dialogue compromises

its meaning or rhythm or humor. Sometimes, the strip no longer even

makes sense. Who benefits from that? We'd prefer that an offending strip

be dropped altogether." The incident is heavily laden with satirical

irony of a nearly celestial sort. What the offended editors did was

to censor the President of the United States. "Turd Blossom"

is, after all, GeeDubya's official nickname for Rove. So for the first

time in a long time, the word of George W. ("Whopper") Bush

is not acceptable to newspaper editors. Delicious. At the Sandy Eggo Comicon (July 14-17),

DC Comics revealed two future projects that will employ Will Eisner's legendary Spirit character:

the first, in December, is a single-issue comic book in which the Spirit

meets Batman, written by Jeph

Loeb and drawn by Darwyn

Cooke; second, starting next year, is a new monthly title starring

the Spirit, written and drawn by Cooke. Both projects, according to

Newsarama.com, were in the works while Eisner was still alive. The idea

for the Spirit-Batman team-up, says Eisner biographer Bob Andelman,

reaches far back to the time Denny O'Neil discussed this "dream"

team with Eisner when Kitchen Sink Press was Eisner's publisher. O'Neil

saw both characters as typically serving as vehicles for stories about

the common man (or perhaps the abused human psyche), and he therefore

longed to see them paired in some grand and gritty reality adventure.

"It was one of those projects that everybody thinks is a good idea,

but there was no compelling reason to do it," O'Neil remembered.

Eisner breathed new life into the idea last winter before he died. Cooke,

who was starting to work out a creator-owned title of his own, was surprised

to be offered the assignment-but thrilled and excited by the prospect.

Said he: "I've been a Spirit fan since age fourteen, and I can

honestly say that he was the only licensed character in the industry

that could have got me to change course." In the monthly title,

Cooke plans to bring the Spirit into contemporary times rather than

dwell in the post-war world of Eisner's last work on the feature. The

up-dating will permit him to extent the realm that Eisner so delighted

in exploring- the urban milieu and the stories of the people who occupy

it. Cooke said he has two goals. The first is to preserve and, if possible,

enrich the essence of the Spirit tradition, tales of ordinary people

and their oft doomed aspirations. "Placing Denny Colt in the modern

world is an updating of sorts," Cooke said, "and there will

be a number of new femmes, criminals and loveable losers to go with

the incredible cast Will created. However, I don't see any need for

'tweaking' the concept. Will's genius has created a strip where I can

explore the human condition from virtually any conceivable angle. I

couldn't ask for more. The second goal," he continued, "is

to produce a work that reaffirms the Spirit as the strip for graphic

innovation that enhances storytelling." And Cooke, judging from

the variety and punch of his work in his issue of Solo, is just the man for the job. Denis Kitchen, acting for the Eisner estate,

will shepherd the project. "Denis, Will's longtime friend and associate,

will be with us every step of the way," said Cooke, "and so

far, we seem to be in concert regarding the direction we're heading

in." The last issue of Cartoonist PROfiles, the profession's longest

continuously published periodical, will come off the press in a week

or so. The June 2005 issue, No. 146, will end the quarterly's 36-year

run. Jud Hurd, the founder, publisher, editor and, for most of those

three-and-a-half decades, the chief (if not the only) writer, suffered

a stroke in early May. In his nineties, he'd been approaching every

issue for the last few years as if it might be his final issue. Enterprising

writers kept sending him articles, and he kept the magazine going to

print them. But the June issue, he was pretty sure, he told me, would

wind it up. He'd compiled much of the content before the stroke. His

wife Claudia, his partner and business manager, finished assembling

the material and shipped it off to the printer in Alabama, where it

has been printed for decades. At 156 pages, the June issue is the largest

PROfiles ever published. Another record.

Going out with a memorably big bang. For more about Jud and his magazine,

see Opus 131. Warner Bros cartoon network is abandoning

the mascot that has accompanied it since its launch ten years ago: Michigan

J. Frog, the miraculous singing amphibian, is being retired because,

it seems, he appeals to too young a demographic. Warner Bros is aiming

for the 12-34 bracket, and the Frog was hot mostly with teenagers, reinforcing

the idea that WB was "that teen network" while the network

hopes to grow a young adult audience. "The frog is dead and buried,"

said WB Chairman Garth Ancier, according to Lisa de Moraes at the Washington Post. "The frog was on life support for a long time,"

Ancier continued, "and then we got permission from a federal court

to disconnect the feeding tube." Ancier, said Moraes, has "always

had it in for Mr. Frog, according to well-placed sources who wished

to remain anonymous because it's a short hop from killing a frog to

knocking off a snitch." Free Comic Book Day in 2006 will be

May 6. ... According to John

Jackson Miller at the Comics

Buyer's Guide, "sales of comic books and trade paperbacks to

comics shops increased 9% in the first half of 2005 to $168.4 million."

My guess is that the graphic novel aspect of the calculation is the

biggest component in the increase, and Miller confirms this, saying

that "an ever increasing amount of business is being generated

by the thousands of backlist trade paperbacks." ... The most recent

CBG, cover-dated October,

is another of increasingly rare issues-one without a movie-based cover.

... One of my favorite Batman illustrators, Jim

Aparo, died in mid-July at the young age of 72; Mark Evanier does a nice obit at www.newsfromme.com

... Attentive subscriber Steve

Thompson tells me that I misspelled Pete

Seger's name last time, influenced, doubtless, by my lifelong admiration

for Popeye's creator, who spelled his name Segar. I'm deeply humiliated

and, forthwith, have acted to correct the error; thanks, Steve. Sorry,

Pete-but, again, happy birthday. ... The second volume of

Mike Allred's graphic novelization of the Book of Mormon, The Golden Plates, was released May 25 and is reported to be selling

well. Reporter Heidi Hatch said: "The comic is all new art, but

the characters are speaking straight from the Book of Mormon."

Some buyers, she reports, are not members of the church of the Latter

Day Saints: they're just fans of the cartoonist. Laborers in the literary vineyards

are increasingly cultivating comics. Jonathan

Lethem, whose novel Motherless

Brooklyn won the National Book Critics Circle Award, will be writing

a ten-issue comic book series about the enigmatic 1970s Marvel superhero,

Omega the Unknown. And Pulitzer-winner Michael

Chabon is doing the comic book version of the Escapist, the fictional

superhero in his otherwise normally populated novel, The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Comments icv2: "Interestingly

enough the history and iconic mythology of comic book superheroes provided

key themes for the novels by both Chabon and Lethem, so their involvement

in the actual writing of comics should come as no surprise to the readers

of their fictional prose efforts." And this development, icv2 continues,

"speaks volumes about the comic book's newly acquired respectability."

Joss

Whedon, who brought tv's Buffy the Vampire Slayer to life for seven

seasons, is determined to revive DC's Wonder Woman, a character who,

against all indications to the contrary, has failed to light fires of

affection in fandom. Whedon's agreed to try a movie adaptation of the

character in the spangled hot pants. "I said 'yes,'" he explained,

"because in the process of trying to say no, I thought about her

character and fell in love with her." Jessica

Alba says about her experience portraying Invisible Woman in the

Fantastic Four movie: "Men run the business, and when you see Elektra

or Catwoman, it's clear they don't understand it's more than a hot girl

kicking [butt]. 'Fantastic Four' is about relationships, family, life.

Her abilities and the effects are separate. ... She's the strongest

of the four. She can manipulate everyone else's powers. She doesn't

need to walk around in a bikini to impress." FF director Tom Story

admits the temptation to put Alba's embonpoint into curve-hugging tights

at every opportunity was strong, but he also realized the difference

between male and female action heroes: it's motivation. "Males

go out and start shooting people," he said. "People understand

that. But with women, it's not that easy. You've got to put a real package

around them to explain why they are an action hero." USA Today's Susan Wloszczyna, discussing

cinematic action heroines, writes: "Back in the waning days of

women's lib, a shining symbol of feminine fortitude emerged. Sigourney

Weaver's capable and captivating Ripley in 1979's "Alien"

as well as its first sequel was on par, if not superior, to any man.

She remains the gold standard." But "a close second is Linda

Hamilton, "whose sculpted biceps far out-bulged her breasts [as

Sarah Connor] in 1991's 'Terminator 2.'" After seeing several unfavorable

reviews of the FF movie, I opted out of seeing it. (Besides, I was out

of the country at the time and wouldn't be able to review it on anything

like a timely basis.) But friends of mine who've seen the flick say

it's better than the Batman-enthralled reviewers said it is. In Metropolis, Illinois, a 15-foot bronze statue of Superman stands in

Superman Square at the center of town. But there's no organic connection

between this Ohio River town of 65,000 and America's most famous superhero.

Superman's co-creator Jerry Siegel named his comic book big city Metropolis

but probably never heard of the Illinois hamlet. The place is "more

Mayberry than Metropolis" according to Editor

& Publisher (June 27), but the locals have capitalized on the

Superman association ever since the Illinois Legislature decreed it

Superman's home town in a flurry of funnybook patriotism in the 1970s.

The local newspaper was called the

Metropolis News until 1972 when it was christened the Metropolis

Planet to echo the name of the newspaper Clark Kent works on. An

annual Superman celebration draws thousands to the town, and 50-year-old

Jim Hambrick glories in it all: he arrived from Hollywood 13 years ago,

and now operates a combination museum and souvenir store, boasting "the

largest Superman collection on the planet." And there's that storied

phone booth downtown, too. But it's just for show: there's no phone

inside. Not to be outdone, probably, by its

DC Comics rival, Marvel Comics has its own

Marvel Adventures City as part of the Canadian Niagara Group's Falls

Avenue Complex. Marvel City is a funhouse of the company's comic book

characters: Spider-Man Ultimate Ride, X-Men Bumper Cars, and the Incredible

Hulk Encounter vie with coin-operated machines and colorful cut-outs

of the usual spandex band. According to Joseph Szadkowski at the Washington

Times (June 25), the effort "comes off more as a co-op arcade

on steroids than a mini-theme park." The best of the rides, he

says, is the Spider-Man adventure, which "melds 3-D technology,

multimedia and target shooting." The Hulk Encounter, on the other

hand, is "a complete waste of money and space," a haunted

maze filled with loud sounds. The most amazing thing about the complex,

however, is that there aren't any real comic books for sale-just "a

smattering of graphic novels" in a glass case. Too bad. The House

of Ideas came up short here, apparently. James Doohan, who played the chief

engineer of the starship Enterprise

whose job it was, in the "Star Trek" tv series and subsequent

movies, to respond to Captain Kirk's command, "Beam

me up, Scotty," died on July 20 at the age of 85. I've been

invoking the Star Trek command in our bi-weekly Rabbit Habit Alert,

and you'd think, now, out of respect, I'd retire the expression. Nope:

out of respect, I plan to keep using it as a continuing reminder of

the glory days of yesteryear when nights were filled with revelry and

life was but a song.

SOJOURNING IN YE OLDE MERRIE There

are no bugs in England. Or maybe they're just better trained bugs. Or

smarter than their American c Yan. We were scheduled to leave on July 9 on a night flight

from O'Hare to Newark and thence to England. And on July 7, bombers

attacked London. Not to worry, I told my wife: we're flying into Birmingham,

not London. Safe. Well, not quite. On the flight from Newark to Birmingham,

we learned that Birmingham's central core, the nightclub and restaurant

area, was being evacuated, even as we winged our way eastward, because

of a bomb threat: 20,000-30,000 people were moved out of the city center,

driven from their dining tables in mid-meal and from pubs in mid-drink.

Turns out, it was a false alarm. And at the airport when we arrived

a few hours later, nothing was happening. No evidence of security or

constabulary. It was the tamest (not to say boring) arrival of all time.

No one even spoke. It was like walking through a mausoleum. A single

long line of passengers filed patiently, silently, through the customs

process. No security-related nonsense whatsoever. (Nor did we have any

of these shenanigans when we departed two weeks later. Didn't have to

take our shoes off; none of that silliness. Just walk through an x-ray;

send carry-ons likewise. Easy.) But when we arrived at Newark on the

return, we re-entered nightmare alley. With only an hour between flights,

we had to pick up our luggage, go through customs, and get to another

terminal for the connecting flight to Chicago. We made it, but the luggage

didn't. And we had to take our shoes off and go through security check

again, too. This charade is fully supported by a government intent on

keeping us forever diverted from noticing its abuses in every other

department of civic affairs. We are expected, it seems, to derive reassurance

about our safety from such pointless exercises as the confiscation of

fingernail clippers; or, alternatively, to be so frightened at the realization

that we are still in danger that we'll re-elect George W. ("Warlord")

Bush again because only he can protect us.

Phooey. Fact is, we are not

safer now, thanks to GeeDubya. Robert Pape, who's just published a book

about suicide bombing called Dying

to Win, made what I think is the most telling observation in this

arena during a radio interview several weeks ago. Said he: "Al

Qaida is stronger now by the only measure that counts-their ability

to kill us." Tyan. We were in England during some pretty eventful days,

all of which were happening right there, on the sceptered isle-or quite

nearby across the English Channel. And the English national tabloids

were full of it the whole time. For the first week, they abounded in

daily reports on police pursuit of the identity of the London bombers.

They did it pretty fast, seems to me: they'd nailed the names of the

four by Tuesday morning, less than a week later. Meanwhile, the G-8

conference in Scotland transpired, forgiving debts in Third World nations

but not able to convince George W. ("White Heat") Bush that

the planet is heating up. Then the 6th Harry Potter book came out, Jack

Nicklaus made a birdie at St. Andrew's on his last competitive golf

hole (and shed a tear and hugged his son), Tiger Woods won his second

British Open, Ted Heath died, Lance Armstrong made steady progress in

the Tour de France (eventually winning his seventh consecutive, two

more than his nearest competitor), Camilla unveiled her coat of arms

as Duchess of Cornwall, and the sports pages started raving on about

the approach of the cricket test matches between England's best and

Australia's, a rivalry that dates back to the mid-1880s. Tethera. J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince went

on sale at 12:01 a.m. British Standard Time, and bookstores worldwide

stayed open through the wee hours to push those books into the hot little

hands of today's Youth. Once again demonstrating that, computer game

sales to the contrary notwithstanding, reading has not gone out of style

altogether among the Young, the book sold 10 million copies in the first

24 hours. At W.H. Smith's 390 stores in England, the book was selling

at the rate of 13 every second, breaking the previous record of 8/second

set by-the fifth Rowling opus, Harry

Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Work began immediately to translate

the book into the 62 languages it will soon be published in. The

Phoenix reached No. 1 on the bestseller lists in both France and

Germany, the only English-language book ever to achieve that pinnacle.

Methera. Camilla's coat of arms fittingly

features a royal lion (from her husband's heraldry) and a boar (from

her father's) but, strangely, no horsey regalia: coats of arms traditionally

incorporate symbols of the principal's preoccupations, but Camilla's

equestrian interests aren't trotted out here. Camilla and her spouse

are not very popular among the masses, it seems. Three years ago on

our visit to the United Kingdom, we'd purchased one of those ornate

cups commemorating the 50th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth's

ascension to the British throne. This year, we tried to find a similar

piece of china that commemorates the wedding of Charles and Camilla.

Hard to find. Shopkeepers universally said that they hadn't stocked

many (or, even, any) of the crockery because Charles and Camilla are

so unpopular retailers feared getting stuck with an inventory of cups

they couldn't sell. Pimp. In the world of cricket, the

test matches between England and Australia are called "the Ashes."

The winner, ostensibly, gets the Ashes. But not really. It all started

in 1882 when England lost to Australia, and a distraught journalist,

Reginald Brooks (son of Shirley Brooks, whose death in 1874 ended a

four-year editorship of Punch, the culmination of a lifelong career

at the magazine), wrote in the Times:

"In Affectionate Remembrance of English Cricket, which died

at the Oval on 29th August 1882. Deeply lamented by a large

circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances. RIP. NP. The body will

be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia." Subsequently, the

Aussies perpetuated the spoof and presented the English team with a

tiny urn that supposedly holds the Ashes of the recently deceased. The

urn is permanently on display in the cricket museum at Lord's, one of

the great English cricket pitches (another being the aforementioned

Oval); so the so-called contest for the Ashes is, as they

say, "a notion rather than a fact." But the competition is

nonetheless keen-particularly in England, which has not won as often

as Australia. Of the 306 "tests," Australia has won 125; England,

95-86, a draw. England hasn't won the Ashes since 1987. Sethera. As you can see, there was plenty of exciting news to follow in the heroically lurid English press. Not all British newspapers are screaming mongers of scandal and sensation. The Guardian of Manchester, for example, seems an exemplar of responsible journalism. But even the London Times, once a staid bulwark of the establishment, now appears in tabloid format with tinges of tabloid sensibility (a consequence, one supposes, of being owned by Rupert Murdock, the king of tabloid journalism); but it's still more text than picture and therefore still more respectable than the usual run of tabloid newspaper, whose front pages are, typically, circus posters of bellowing headlines and shocking pictures. I picked up and sampled most of the tabloids that are distributed nationally- Daily Mail, Sun, Daily Record, Daily Express, Daily Mirror. The most outrageous of these is clearly the Daily Sport, which out-sensationalizes the others by moving the famed Page Three Girl to the front page (albeit with her chest covered, mostly, rather than bare, the customary Page Three Girl pose). Sport's front page always features nearly barenekidwimmin, rotating poses systematically through chest, crotch, and butt shots.

The

newspaper's name is somewhat misleading-unless you think sex is a sport.

Only about four pages at the back are devoted to athletic competitions;

the rest of the paper seems a tireless advertisement for pornographic

movies. I read The Independent

every day, and it seems the least sensational of the traditional

tabloids: it's text and pictures are in a roughly even balance, and

the front page always has text as well as photographs. Lethera. To supplement sensation and

gossip, the papers often include enterprising feature material on obscure

topics. One day, for instance, the Independent

listed "the top ten films that British schoolchildren should

see by the age of 14," headlining it "The X-rated Films Every

Child Should See." The list included "E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial,"

"Toy Story," "The Wizard of Oz," and "Night

of the Hunter"-all of which seem to me strangely dubbed "x-rated."

Meanwhile, on the same day, the Daily

Mail listed "Fifty Films Your Child Should See by the Age of

14"-including Errol Flynn in "The Adventures of Robin Hood"

(1938), "Back to the Future" (1985), "King Kong"

(1933), "The Kid" (1921), "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs"

(1937), "To Kill A Mockingbird" (1962) as well as the films

listed in the Independent. The lists are actually one

list compiled by the British Film Institute; the Independent chose to print only the top ten of the fifty. And here's

a piece about designer Roberto Cavalli's contract to re-interpret the

costume of the Playboy bunny. Another article provides thumbnail plot

summaries of all 37 Shakespeare plays by way of announcing the Royal

Shakespeare Company's intention of staging all of the Bard's plays in

a special festival. And here's a mother's account of her breast enlargement

surgery, which she undertook in order to "accompany" her daughter

through the same ordeal: "When we first took the bandages off a

few days later, we both burst out laughing because we were so swollen

and looked very funny. I was very happy once the swelling had gone down

and I saw my lovely breasts for the first time. I felt brilliant and

threw away all my padded bras." And, finally-in the same titillating

spirit-an article about the latest artwork of Brooklyn's Spencer Tunick,

a photographer who, on special assignment in Britain, recruited 1,700

people to pose naked at Gateshead in Newcastle for a work entitled "Naked

City." The article, accompanied by a double-page spread photograph

of a sea of nudity (everyone is lying down, side by side), noted that

Tunick had done similar exposes at the Saatchi Gallery and on the escalator

at Selfridges on Oxford Street in 2003 and in Barcelona, Melbourne,

and Montreal in previous years. The best of these pieces was in the

Daily Express, which sent

its own reporter, Sophie Tweedale, to join "the living landscape"

by "stripping off" (as they say). She begins by saying she's

no prude, but "put me on a topless beach in Spain, and I'm the

one sitting there clutching my bikini top." Her embarrassment on

this assignment, she confesses, was "fast overtaken by sheer cold."

Her verdict: "There was certainly something strangely bonding about

the whole experience of mass nudity." Hovera. None of the national tabloids

I looked into-and I sampled them all-had more than a few comic strips.

Most had a single page, which, at tabloid dimension, offered only 5

or 6 strips. Most of them were in color, but the reproduction was so

poor that they all appeared to have been pulled off a computer with

not very many working pixels. And strips from U.S. syndicates showed

up, too- Dilbert, Doonesbury, Hagar, Garfield, Peanuts, and the new panel from

the McCoy brothers, The Flying

McCoys. The Daily Record and

the Sun had 3-tier strips rendered almost photographically

in air

Political cartoonists are the masters of the medium in UK, judging from

the evidence. S Dovera. Otherwise-I must not be getting

out much because it seems to me that young women in England wear less

in public than young women in America. I could be wrong about that:

as I say, I don't get out much. My wife agrees with me; of course, she

doesn't get out much either. In any case, we saw lots of lithesome jiggling

young ladies whose tube tops were cut both low (at the top) and high

(at the bottom), which, in combination with those low-riding hip-hugger

pants, revealed a good deal of epidermis south of the belly button.

Meanwhile, the cleavage vicinity between the navel and the clavicle

was in constant motion, it seemed-altogether, a wholly refreshing bird-watching

experience. We also saw lots of tattoos, bra straps, scruffy-looking

males with hair carefully mussed (moused?) to look as if they'd slept

wrong in it, and T-shirts. Even at the best four-star hotels, T-shirts

were the universal attire. British decorum has long departed. But we

didn't see as many people walking around with cell phones at their ears

as we do on the average U.S. street. Dick.

ODDS & ADDENDA. In Saga magazine, in a review of Douglas Addams'

Hitchhiker books, I ran across this assertion of the enduring value

of affability: keep your head, watch your manners, and try to be pleasant,

it might yet all turn out for the best. The writer also espoused the

English conviction that a nice cup of tea will put it all right. Yan-A-Dick. At a sweet (candy) shop

in Keswick were several tiers of shelves lined with jars of candy, each

jar bearing a commercially issued label to identify the kind of candy

therein-jelly beans, tootsie rolls, gum drops, etc. But one jar had

a hand-wrought label that read: "Those pink and yellow round things

with black centers that you get in All Sorts Liquorice." Tyan-A-Dick. Here's something your

ATM card issuer probably doesn't tell you: don't enter your PIN more

than twice. If the first try doesn't work and the machine asks for a

second attempt, go ahead; but if that fails to produce the desired result,

retrieve your card and go away. If you punch in the PIN a third time,

the machine will "retain" your card. But you won't get it

back: the bank will cut it up into little pieces. Tethera-A-Dick. Browsing the china

shops, I was delighted to see that Norman

Thelwell's fat ponies and their juvenile riders have finally been

translated into three dimensions. I've thought they were ideal candidates

for converting to figurines. But the translations I saw, while encouraging,

were not faithful enough to the original. The ponies weren't quite as

plump as Thelwell drew them; and the kids, not quite as cute. But there

are cups upon which his drawings have been copies exactly, and those

are better than the figurines. Quentin

Blake is another matter: his renderings of the characters in Roald

Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory have been ingeniously duplicated

in figurine form, nearly perfect incarnations. Excellent. Alas, I saw

them on our last day in the country and didn't have time to stop and

decide which one to buy. (And they're too expensive to buy more than

one, kimo sabe.) Methera-A-Dick. This just-invoked term,

and the others with which I've cryptically ear-marked every preceding

paragraph in this recitation, are the English shepherd's antique tally

for counting sheep. Herein, we've gone, in order, from One to Fourteen.

Fifteen is "bumfit" and twenty is "giggot." More

than that, I dunno. But I suppose (because I so fondly wish it) that

British shepherds still employ this method when inventorying their flocks.

One more. On July 20, the front page of the Independent

was mostly numbers, beginning with a figure three inches high- 24,865,

the number of civilian dead in Iraq, a number no official agency in

either the U.S. or England seems to be keeping track of. I'd seen the

number slowly accumulating at www.iraqbodycount.com

over the months, so I wasn't surprised at its magnitude. Between March 2003 and March 2005, civilian

Iraqis were being killed at the rate of 34 every day; the total, so

far, is roughly ten percent of the country's population. Nearly ten

percent of the total were under the age of 18; 10% of the adult dead

were female. The statistics have been assembled from news media reports

and from official figures supplied by the Iraqi Ministry of Health and

Mortuaries. Anti-occupation forces have killed about 2,300; military

forces, about 9,000. One of the report's compilers said: "The ever-mounting

Iraqi death toll is the forgotten cost of the decision to go to war

in Iraq. It remains a matter of the gravest concern that, nearly two

years and a half years on, neither the U.S. nor the U.K. governments

have begun to systematically measure the impact of their actions in

terms of human lives destroyed." Another added: "Iraq is descending

into anarchy and the U.S. presence is not helping. It has shown its

incapacity to create a peaceful state. Never again will intervening

states so greatly underestimate what is involved in invading and rebuilding

a country." However well-intentioned the Bush League power play,

it has gone far awry, effectively perverting everything Americans think

their country stands for. This may well be the saddest chapter in our

history.

ROWLAND B. WILSON, AGAIN Time noticed that Wilson is no longer among us and spent at least three sentences

on his life and career. I didn't do much better, I'm afraid (Opus

165), but now I know more, thanks to the Independent in England, which devoted a third of a page on July 14

to Wilson's obit. Maybe he rated something akin to that quantity in

some U.S. publication that I missed while playing hokey in England,

but on the chance he didn't, here's most of what Philip Hoare wrote

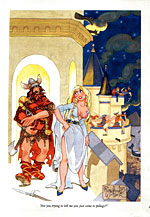

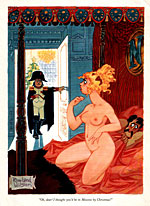

in the Independent (amplified, a little, by my [bracketed] remarks): Rowland B. Wilson's work will be immediately

and evocatively familiar to any young boy who has sneaked a peek in

his father's copy of Playboy.

Wilson, who drew cartoons for the magazine from 1967 until his death

two weeks ago [on June 28 in Encinitas, California], was the master

of subtle humour. "He was the tasteful guy at Playboy-

he didn't do the really rude ones," recalls his daughter Megan.

Wendy is sitting on Captain Hook's knee in a dark cave. Peter Pan runs

in, arms flailing, in an effort to save her, and she says, "Aw,

grow up!" Rowland Bragg Wilson was born in Dallas, Texas, on August

3, 1930, and would remain a Texan in tastes and opinions. As a child

of the Great Depression, he spent his Saturdays at the cinema, and would

come home, drawing Disney characters at the kitchen table. Having gained

a degree in fine arts at the University of Texas in Austin, he went

on to Columbia, New York, supporting himself in the meantime by sending

cartoons to such publications as the Saturday Evening Post and Collier's. His budding career was put on

hold when, in 1954, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, serving in Germany

and using his artistic talents to create classified charts. He complained

bitterly, "The army stole two years out of my career." Having been demobbed (demobilized in

Americanese), in 1957, Wilson joined a Madison Avenue advertising agency,

Young and Rubicam. He spent seven years there as an art director, creating

drawings for advertisements. In 1958, he became a regular contributor

to Esquire-Wilson was at that time sharing

an apartment on Third Avenue with the magazine's art direction, Robert

Benton- and throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, his work was

published in The New Yorker. In 1962 a collection of

his cartoons [mostly in black-and-white] was published under the title

The Whites of Their Eyes. "Ideas are

easy to come by," he wrote in the blurb. "It is the drawing

that takes a long time." In 1964, Wilson left New York for Weston,

Connecticut, and became a freelance advertising artist, but continued

to draw cartoons. He drew a comic strip, Noon

[it debuted March 6, 1967], which was widely syndicated [I'd say

not so widely: I don't think it lasted more than a year, if that.-RCH],

and began a long relationship with Playboy.

Wilson's work was highly regarded, both by his editors, and his readers:

his use of colour was superb, his draughtsmanship unmatched, and his

knowledge of historical detail immense. Megan Wilson also observes that

"movies informed his cartoons. His dramatic use of perspective

was influenced by the great cinematographers of his youth." [Wilson's

deployment of extravagantly different perspectives was most evident

in a series of advertisements he did for a life insurance company in

which he depicted, from a wildly divergent angle, some personage being

threatened by something he has not yet perceived-a giant wrecking ball,

say, swinging towards the window to which his back is turned-who says,

"My insurance company? New England Life, of course. Why do you

ask?"] From advertising, he moved into animation.

From 1973 to 1975, he worked in London for Richard Williams's animation

studio, where his love of cinema blossomed as his cartoons came alive.

He drew animated cartoons for Tic-Tac with a 1940s film noir look. Another television commercial for Williams, "The

Trans-Siberian Express," won first prize at the International Animation

Festival in New York. Wilson returned to Manhattan and drew an educational

animation tv series, "Schoolhouse Rock," which was a landmark

learning tool for children of that generation, in the late 1970s. He

won an Emmy award for the series. In the early eighties, Wilson moved

to California, where he worked for Disney. He did pre-production design

for "The Little Mermaid" (1989), "The Hunchback of Notre

Dame" (1996), "Hercules" (1997), "Tarzan" (1999),

"Atlantis" (2001) and "Treasure Planet" (2002).

Wilson had many proteges, including the young Tim Burton, whom he dissuaded

from his ambition to become a

Playboy cartoonist. (Burton would go on to create "The Nightmare

before Christmas" and "Edward Scissorhands.") Wilson painted epic watercolours, in

which he would imagine what medieval Paris would look like when the

Hunchback was there. Or he would recreate a Victorian picnic in the

jungle. It all tied into the historical knowledge for which his Playboy

and New Yorker cartoons

were famous. His job at Disney was to create the look of the film-not

the characters, necessarily, but the backgrounds. His artistic talent

was inherited by his four daughters, all of whom are artists: Amanda,

a New York-based graphic designer; Reed, a fine artist and illustrator

in London; Kendra, magazine designer for The

Observer; and Megan, Associate Art Director fo Random House in New

York. Wilson's first wife, the interior designer Elaine Libman [whom

he married in 1952] divorced him in 1977. His second wife, Suzanne Lemieux

[married in 1980], is also an artist. On the day of his death, a sketch

for a new Playboy cartoon still lay on his drawing board. RCH again: Those young men who sneaked peeks into their fathers' Playboys and found Wilson there are indubitably the better for having experienced the pristine purity of the cartoonist's line and searing clarity of his compositions, not to mention the insightful glimpses into history that he invariably afforded. It's not surprising, either, that Wilson thought drawing was more work than conjuring up ideas: his ideas always involved period costumes and locales out of the distant past, which he not only had to research for authenticity but depict with a persuasive flair for accuracy. Tasteful his drawings and his humor always were, but he was not above limning barenekidwimmin with enthusiasm, and we're all the better for that, too.

I

hate to keep bringing this up (well, I don't mind, actually, but I don't

want to appear obsessed by the subject), but when I mentioned this last

time, I wrote: "Here's Pam

Anderson in the current issue of the laddie mag, FHM

(the one with her and her chest on the cover). During the interview,

she describes her outrage at seeing a photograph of herself in another

magazine in which her nipples, which were visibly protruding against

the confining fabric of the bodice of her shirt in the photograph until

it was printed, had been airbrushed out! Protrusions erased! Breasts

hideously de-nippled. Pam, who has made a career of her boobs and nipples,

was understandably miffed at this slur on her fame: 'My nipples can

cut glass,' she exalted in an apparent assault on the offending airbrusher.

Maybe, but I'm not sure that nipples that can cut glass are at all erotic.

I mean, think of what they'd do if you ...." While I was alarmed, then, about the

alleged superpowers of Pam's nipples, I found out while traipsing around

Ye Olde Merrie what she actually meant when she likened her nipples

to diamonds. The British edition of FHM

is somewhat more liberated than the American version (breasts are

unveiled in the British edition), and she is quoted at some length on

the subject only vaguely alluded to in the edition I saw over this way.

Said the mammorable Pam: "I can cut glass with my nipples. I remember

getting bugged about them in high school. They'd get harder and harder

as people talked about them. I was like, 'Stop talking about my nipples:

they'll just get worse.' My nipples show through anything, even when

my T-shirt isn't wet. They're always on call-a shot of espresso or tequila

goes straight to them." Okay, now I'm really worried: her super-powered

nipples get their powers from -caffeine? Or-what?-dead worms?

COMIC STRIP WATCH On

July 10, a historic event commenced in Blondie.

That date marks the launch of a two-month continuity in the strip, which

hasn't run anything approaching a continuing story since Dagwood went

on a hunger strike in 1933. This summer's storyline culminates on Sunday,

September 4, just on the cusp of the 75th anniversary of

the strip's debut in 1930. Blondie's traditional starting date has

been given as September 8 for decades; recently, Jeffrey Lindenblatt, who delves deeply into such matters, disputed

the tradition: he consulted all three Hearst papers in New York and

found that Chic Young's celebrated strip appeared

in nary a one of them on September 8; but the first Blondie appeared in one of them, the American, a week later on September 15. Blondie is syndicated by King Features, which is the Hearst syndicate,

so the strip's absence in Hearst's New York papers on its alleged starting

date is of more than casual concern to historians. It's possible, I

suppose, that Blondie began

elsewhere on the King circuit on September 8 and debuted in New York

the next week just because the New York papers didn't have room for

it on the 8th, but we won't be able to settle the matter

until someone somewhere finds Blondie in a 1930 newspaper on September

8. Until that fortuitous moment, we'll barge witlessly ahead, still

citing September 8 as the official beginning date. The strip began as a "flapper"

strip about a dizzy young blonde named, with unrelenting perspicacity,

Blondie. This was Chic Young's fourth pretty girl strip: in October

of 1921, he'd done The Affairs

of Jane at N.E.A. for six months until it faded, and then he'd come

to New York and done Beautiful

Babs for Bell Syndicate for four months before joining the King

Features art department in 1923 and creating Dumb

Dora. Dora proved popular enough to endure longer than its forerunners,

and when the 1929 stock market crash wiped out his savings, Young, thinking

he had leverage, lobbied for more money. But Joseph V. Connolly, King's

energetic and imaginative general manager, was not inclined in that

direction. Young threatened to quit; Connolly still resisted. So Young

packed himself and his wife off to the French Riviera to make his point.

When Connolly wired, pleading him to return, Young consented-but only

for a bigger piece of the action and his own comic strip. Connolly agreed,

provided Young could come up with an acceptable creation. Returning

to New York, Young spent the summer devising a new strip. It was yet

another pretty girl feature, and this one would reign as one of the

world's most widely circulated strips for longer than just about anybody. Blondie had numerous beaux in the early

years, but the one that kept coming back was the one who introduced

her to his tycoon father on the very first day-Dagwood Bumstead. "I

always feel so boo-boop-a-doop when I meet my boy friends' papas,"

Blondie giggles, "but I usually like them better than the sons.

Can't I call you 'Pop,' Mr. Bumstead? Tee hee!" When Dagwood decides

to marry Blondie, his snooty parents object, so Dagwood goes on a hunger

strike that lasts 28 days, starting January 3, 1933. His parents finally

consent to the marriage, but Dagwood's father disinherits his son, a

callous strategy perhaps, but one that opened the way for Blondie and

Dagwood to become The American Newlyweds, then The American Young Mother

and Father, and, ultimately, The American Family, a niche the strip

has enjoyed for most of its 75-year history as the pace-setter for the

domestic comedy genre of comic strip. Most of the drawing after the

1930s was done by other cartoonists under Young's supervision. First,

Jim Raymond (brother of Alex, the Flash Gordon/Rip Kirby conjurer); then

Mike Gersher followed by Stan Drake. Currently, it's Dennis LeBrun and Jeff Parker. This summer's storyline commemorating

the anniversary ostensibly aims at the couple's wedding anniversary,

but that ceremony occurred on February 17, 1933, not in September. In

seeming defiance of this fact, Dagwood and Blondie and their offspring,

Alexander and Cookie, will spend the next month continuing to plan an

anniversary party, a gala event. During the next weeks, other comic

strip characters will allude to the forthcoming festivities in their

own strips- Garfield, Zits, Mutts, Beetle Bailey, Hagar, For Better or For Worse,

Mother Goose and Grimm, B.C., Wizard of Id, The Family Circus, Marvin,

Dick Tracy, Gasoline alley, Curtis, and Bizarro.

And Dean Young, the creator's

son and current steward of Blondie,

will include these characters in his strip. GeeDubya and Laura are also

slated to appear. Then on September 4, they'll all come to the party.

But will it be a wedding anniversary? Blondie's been pretty coy about

it: on July 10, when the storyline began, she says to Dagwood: "I

can't believe you still haven't figured out which anniversary we have

coming up!" Dagwood is stumped, but Blondie finally tells him,

"It was when we began our lives together!" Blondie's right,

of course. But I suspect she's alluding not on their February 17 wedding

day but that fabled first day of the strip, when Dagwood introduces

her to his father-whether September 8 or September 15. That's when their

"lives together" began, after all. Dagwood, however, thinks

she's talking about their wedding anniversary. So I suspect the punchline

of the story will land on Dagwood on September 4 when he finds out it's

not their wedding anniversary that he's been planning a party for all

summer.

From Terry Van Kirk, editor of Slice

of Wry, the newsletter of the Southern California Cartoonists Society

(July 21, 2005)--- "Flintstones" Gene Hazelton

to Appear in Sunday Dennis the

Menace. Look for recently deceased Flintstones cartoonist Gene Hazelton in the lead panel of Dennis the Menace on Sunday, September

18. He'll be the elderly gent on his cell phone with the initials "GH"

on his jacket. "It's an in-house salute to a great cartoonist who

never received near the credit he deserved" said Gene's biographer

and long time friend John Province. "When John suggested the idea,

I was HONORED!" said Ron

Ferdinand, who draws the Sunday Dennis.

"Gene has been such a tremendous inspiration to me over the years,

it was the LEAST I could do!"

Ron

had corresponded and traded sketches with the Flintstones cartoonist

over the years and he immediately warmed to the idea as a tribute using

the medium Gene loved. Hailed as one of the finest character designers

in the business, Hazelton, an alumnus of the Disney, MGM and Hanna-Barbera

studios, passed away on April 3. He drew the syndicated Flintstones

and Yogi Bear from 1962

until 1984. After retirement Gene was selected to design and draw a

series of popular limited edition serigraphs subsequently signed by

Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera for the collector market.

"Gene admired Ron's work on Dennis

very much and when I saw one of his drawings of Dennis displayed

on Gene's refrigerator, I knew Ron had made the grade," Province

said. "It was Gene's way of saying 'Great job!'"

Ferdinand has drawn the Dennis the Menace Sunday page since 1981

after being selected and mentored by creator Hank Ketcham. RCH again: Ferdinand's coloring of the

strip, which, he tells me, he performs "the old-fashioned way,"

producing a color guide with prismacolor markers, is stunning. He highlights

flesh tones by leaving patches of white, for example, and the Ketcham-inspired

silhouettes are often a solid color rather than stolid black, and night

scenes are monochromes of blue. The daily Dennis,

which appears as a single-panel

cartoon, is produced by Marcus

Hamilton, who just won the "division award" for newspaper

panel cartooning from the National Cartoonist Society. Appearing in

over 1000 newspapers internationally, Dennis the Menace has

inspired a syndicated TV program, several motion pictures, comic books,

an animated series and remains one of the most popular comic strip franchises

in cartoon history.

Quips

& Quotes I

don't do drugs anymore because I find I get the same effect just by

standing up really fast. Every time I walk into a singles bar,

I can hear Mom's wise words: "Don't pick that up: you don't know

where it's been." Snowmen

fall from Heaven unassembled.

ACTUAL BOOKS Modern Arf (120 giant-size 9x12-inch pages in paperback, $19.95)

is an antic dissertation on the scandalous courtship of art and cartooning

with numerous instructive examples of the propagation that ensued, including

short biographies of both celebrated (Jack

Kirby, Milt Gross, Salvador Dali) and relatively unknown (Hy Mayer, Jimmy Hatlo, Antonio Rubino) geniuses who perpetrated the

ribald romance. Collected and edited by my friend, the master of manic

manias, Craig Yoe, the book traces, in the looney

manner of zany cartoonists everywhere, the relationship between upper-case

Art and lower-case cartoonery by displaying instances of Art in cartooning

and vice versa. In the former category is a section on Patrick McDonnell, who begins his Sunday

Mutts strips with a splash

panel evoking various works of art, both fine and popular; the McDonnell

section of this book, however, offers, instead, samples of his even

more fanciful illustration work and some previously unpublished college

strips. "The comics I drew in college," says McDonnell, "were

minimalist and improvisational. I thought they were Zen." In the

vice versa department is a section of storyboards that Dali made for

a movie, "Surrealist Mysteries of New York," that was, alas,

never made; the storyboards, however, make good comics. Some of Yoe's

examples merely depict characters encountering modern art in comics- Fred Schwab's Lady Luck, for instance, from the "Spirit Section"

dated August 18, 1946. And here's Jack Kirby's story from Amazing

Tales No. 1 (1958), "The Fourth Dimension Is a Many Splattered

Thing," in which the King gets as abstract as any of the moderns

on museum walls (printed from original art in Yoe's personal collection).

Most of the pages of this volume are devoted to displaying extremely

rare comic artifacts: Hy Mayer's series of "worm's eye"

views of various activities (that is, people seen from below; "the

original up-skirt artist," Yoe calls Mayer, but nothing untoward

is on view herein); an array of old postcards depicting Alfred E. Newman before he became Mad's maniac mascot; Italian cartoonist Antonio Rubino's stunning visual inventions in comics form; and Jimmy Hatlo's highly satirical Sunday

feature, The Hatlo Inferno,

a vision of hell in which Hatlo tortures people with whatever it was

that they did in life that annoyed people (roasting over a spite, for

instance, is a group of waiter-baiters "who always complain that

their meat isn't cooked just so"). The book also includes 7 pages

of Yoe graphic goofiness, a somewhat Seussian interpretation of a 1940

critique of comic books that appeared in the Chicago Daily News, which claimed comics

were "a national disgrace ... The effect of these pulp paper nightmares

is that of a violent stimulant. ... their hypodermic injection of sex

and murder make the child impatient with better, though quieter, stories."

To which Yoe responds: "I couldn't agree more," and then goes

on to illustrate his agreement with seven pages of floating eyeballs

and other body parts, gamboling animals of no known species, and dancing

vegetation of various sorts, all liberally injected with pictures of

statuesque nudes of the curvaceous gender. In short, cartooning artistry

of the highest order. The page layouts reflect a similarly waggish sensibility

albeit tastefully, elegantly, deployed. (In the same carefree spirit,

the Table of Contents does not appear until page 31, and although the

pages numbers of the volume's various sections are given hereon, none

of the book's pages actually carry numbers, so you can't find anything

you might be looking for by using the Table of Contents. Another of

Yoe's pranks, no doubt.) Each of the ten sections is introduced with

a short text piece, usually regaling us with fragments of history and/or

biography that has been too long lost in the mists of time. I was delighted

to see a rehearsal of Hatlo's career, for example; his skill at flinging

satirical barbs is too seldom appreciated and applauded in histories

of the medium, perhaps because he drew in a manner that has become "old

fashioned," and we all stampede to be cool and up-to-date these

days. The pages before the Table of Contents are devoted to a series

of cartoons and strips about artists and their models, followed by biographical

vignettes for each of the cartoonists represented. Here again, Yoe performs

a valuable service for scholars and fans alike, stumbling, as far as

I can tell, only once: Rudolph Dirks didn't lose the title of his strip,

The Katzenjammer Kids, during

a 1897 visit to Europe. I suspect Yoe suffered a momentary diversion

of attention while writing this entry and inadvertently substituted

the year of the strip's debut for the year of the celebrated legal action

that prevented Dirks from using the title of his first-born on a subsequent

reprise he concocted for a rival paper. These things happen; they happen

to me all the time. The history of the world has been rewritten in sundry

places due to some lapse or another that I committed while writing about

cartoonists. (By the way, Dirks' trip took place in 1913; the legal

action, the next year.) As for the rest of Yoe's scholarship, try as

I might, I found no other lapses or sins of ignorance. The book is a

treat from front to back, a feast of the kind of rare and wonderful

cartooning we almost never see anywhere anymore. From

Michael Dooley: I'd like to let the others know about a new book

I co-edited [with Steven Heller]: The

Education of a Comics Artist: Visual Narrative in Cartoons, Graphic

Novels, and Beyond. Briefly, it's an anthology of essays and interviews

on teaching, and learning about, the various genres of comics art. It's

now available at book stores and online sellers such as Amazon.

Here's the contributor lineup: Jessica Abel, Ho Che Anderson,

Tony Auth, Bart Beaty, Monte Beauchamp, Colin Berry, Nicholas Blechman,

Peter Blegvad, Steve Brodner, Paul Buhle, Kim Deitch, Will Eisner, Robert

Fiore, Rick Geary, Bill Griffith, R.C. Harvey, David Heatley, Todd Hignite,

Nicole Hollander, Dan James, Chip Kidd, Paul Krassner, Tim Kreider,

Rich Kreiner, Joe Kubert, Peter Kuper, Heidi MacDonald, David Mack,

Stan Mack, Matt Madden, Bob Mankoff, Barbara McClintock, Scott McCloud,

Dave McKean, Rick Meyerowitz, Dan Nadel, Mark Newgarden, Dennis O'Neil,

Gary Panter, Joel Priddy, Bill Randall, David Rees, Eric Reynolds, Leonard

Rifas, Trina Robbins, Roger Sabin, David Sandlin, Ben Sargent, Marjane

Satrapi, Arlen Schumer, Bill Sienkiewicz, Elwood Smith, Art Spiegelman,

Tom Spurgeon, Mark Alan Stamaty, Ted Stearn, Jim Steranko, Barron Storey,

James Sturm, Ward Sutton, Gunnar Swanson, Teal Triggs, Robert Williams,

Chris Ware, and Craig Yoe. RCH: Dooley is being a bit too cryptic.

And the book's title is a trifle misleading: all writing about specific

subjects, any and all subjects, is "educational," and this

book is "educational" in that broadest of senses as well as

in some much more specific senses. In other words, it's much much more

than a "how to" book: it's more of a historical adjunct. It's

great virtue-and it is a considerable one-is in the array of contributors

(all print cartooning fields are represented) and the brevity of their

contributions. Many of the essays are only a couple pages long: you

can pick the book up and read an entire article on the way to the front

door. I've got a piece in it, and I've been paid a modest honorarium

for it. (It's about gag cartooning in the olden days-just to give you

an idea of the scope of this tome.) But I won't be paid anything based

upon book sales. Some of the pieces are interviews rather than essays.

Many brim with autobiographical insights about career paths and the

like. There is a wealth of anecdotal information. Paul

Krassner, founder of the thoroughly irreverent Realist in 1958,

regales us with stories about the cartoons he published that were so

offensive they couldn't be published anywhere else. He did a piece for

Mad, based upon the premise"What

if comic strip characters answered those little ads in the back of the

magazines?" In the service of this scheme, Wally

Wood depicts Orphan Annie getting Maybelline to give her eyes pupils

and Dick Tracy being sent for a nose job. "Alley Oop got rid of

his superfluous hair, only to reveal that he had no ears." But

William Gaines wouldn't let Krassner's

take on Olive Oyl go in: Krassner wanted the flat-chested Olive to send

for falsies. As Krassner ends the story:

Gaines explained, "My mother would object to that."

"Yeah," I complained, "but she's not a typical

subscriber."

"No," he replied, "but she's a typical mother." In the interview with Jim Steranko, I learn that Joe Kavalier

in Michael Chabon's novel

Kavalier and Clay is

based upon Steranko, who, I'd forgotten, is an accomplished escape artist.

I should have tumbled to the Steranko-Kavalier relationship long ago;

drat. "Chabon," says Steranko, "ended up with a Pulitzer

Prize. And I have a stack of comics." The book is crammed with

fascinating tidbits like this-a genuine education; 288 6x9-inch pages

in paperback, some illustration; $19.95. From Rob Weiner: I just wanted to "plug" the book Gospel According to Superheroes. It is a book of collected essays looking at

positive aspects of Superhero comics. It is not a hard-core Christian

book. I have an essay looking at Captain America Young Allies, Invaders

and the JSA during WW 2. I'd

be curious to see any reviews and to know the opinions of people on

the list after viewing it. Stan Lee wrote the preface. And-No, I did not get paid for the article

nor do I receive any money. I just want people to read it.

Forthcoming. Did I mention that Fantagraphics is bringing out Hank Ketcham's Complete Dennis the Menace?

Following the pattern established by the Peanuts

project, this effort will consist of several volumes, the first 642-page

installment due in September. It will include a Foreword by Patrick

"Mutts" McDonnell and an Introduction by Brian "Hi and

Lois" Walker. Fantagraphics is also publishing a new paperback

edition of Ketcham's autobiography, The

Merchant of Dennis. ... Peter Maresca at Sunday Press Books is bringing

out a giant Little Nemo book in celebration of the 100th

anniversary of Winsor McCay's famed feature this year.

I've seen a mock-up of this tome, Little

Nemo in Slumberland Splendid Sundays, and it is stupendous. At 17x23-inch

page size, it comes close to the actual size of Nemo when it was first published. Watch ordering information at www.sundaypressbook.com

... And while I'm at it, remember my own celebration of Nemo's century,

The Genius of Winsor McCay, a much more modest effort than Maresca's

monumental work of art but, withal, worth the highly reasonable price

of admission; more here. We're experiencing

a little difficulty with the credit-card paying mechanism, alas; so

if it hasn't been fixed by the time you try it and if you don't want

to use PayPal, try printing off the order form and sending the thing

directly to me with your check for $11.

CIVILIZATION'S LAST OUTPOST: Part I 100 People Who Are Screwing Up America

(and Al Franken Is #37) is

another fulminating effusion from the rank conservative pen of Bernard

Goldberg, whose early book, Bias,

is about how the mass media in this country is more liberal than

conservative. The tome at hand is the next installment in the campaign.

The Number One Person Screwing Up America is Michael Moore-just to give

you an inkling of what Goldberg is up to. Three cartoonists made the

list: Aaron McGruder is No.

88, Jeff Danziger is No.

35, and Ted Rall is No. 15.

McGruder screws America by being unrelentingly iconoclastic, leaving

no one's sacred cow unscathed. Danziger, the only outright political

tooner of the three, made the list because he once drew Condoleezza

Rice as a plantation-style mammy (Butterfly McQueen in "Gone With

the Wind" was his inspiration). And Rall is there chiefly for ridiculing

the blind patriotism of Pat Tillman (or maybe it was Tillman's unthinking

bellicosity). The lowest ranking person on the list is almost Paris

Hilton, but Goldberg names her parents instead at No. 100. "Paris

Hilton," he writes, "has an excuse. She's a moron. But her

parents can't be let off so easily." While I agree that Paris Hilton

is by far the most outrageous instance of mindless sexuality achieving

celebrity status (her face, frozen forever in a botox grimace of uncomprehending

and therefore meaningless complaisance; her body, apart from its all-over

tan, wholly unexceptional), I don't think her vacuous existence threatens

the welfare of the nation. The news and entertainment media's complicity

in promoting this empty icon is another matter: that, indeed, threatens

the state of the nation. But I divaricate: This Colyum offers unflagging

congratulations to McGruder, Danziger, and Rall for making the list.

Keep it up, gang. By the time George Santayana reached his eighties in the 1940s, the world-famous

philosopher was living on charity in a convent in Europe, thin but well,

albeit plagued by a failing memory. Every day, he walked to a nearby

park where he sat on a bench and read eight pages of a book that he'd

torn out and brought with him; when he finished reading the eight pages,

he threw them away. There's a lesson in there somewhere, for those of

us who can't let go of any printed matter that comes into our hands.

The once ubiquitous jockstrap is fading

from the cultural landscape. Daniel Akst at Slate got curious about

the "athletic supporter" or yore and inquired into it. Yup:

it's true. A spokesman for Bike Athletic, the inventor and manufacturer

of this once-essential piece of sporting equipage, confirmed Akst's

suspicions: "Kids today are not wearing jockstraps." In my

misspent youth, all male participants in competitive sports were urged-nay,

commanded- to wear jockstraps. We were encouraged to think that this

strap of elastic with a pouch for the genitalia would somehow prevent

our balls from being irreparably damaged in the careless rough-and-tumble

of athletic endeavor. It was, we thought, a kind of armor. That was

never the case, however. Jockstraps offer no such protection. And when

Akst asked William O. Roberts, a past president of the American College

of Sports Medicine, Roberts said: "The best I can tell you is that

jockstraps kind of keep the genitalia from flopping around." They

also provide a "holder" for a plastic "cup" that

would, indeed, offer some measure of protection. Akst can't understand

why more athletes don't wear cups: "Kids these days have helmets

for practically everything-I wouldn't be surprised to see my sons wearing

them for violin practice. But surprisingly few wear cups for sports.

... They consider cups annoying ... which explains why many eschew them

even in situations that would seem to call for Kevlar." Not to

be deprived of generations of revenue, Bike is now manufacturing a garment

called "compression shorts," which function as a somewhat

more binding version of jockey shorts. They "provide support and

'steady, uniform pressure' to hold the groin, hamstring, abdomen, and

quadriceps muscles in place during 'the twisting, stretching and pivoting

action of a game or strenuous exercise.' They're also supposed to 'fight

fatigue by helping prevent vascular pooling.'" Vascular pooling?

Holy moly: another phantom disorder that can topple civilization as

we know it.

THE NEWSIES AND THEIR ANONYMOUS SOURCES For

some years, I've been suspicious of the "anonymous source"

device of modern journalism. As a trained journalist, I'm highly apprehensive

about this maneuver. There's far too much of it, too many so-called

"newsstories" in which the source of the information wishes

to remain anonymous. This practice leaves wide open the possibility

that the reporter is simply fabricating his story. Even if he isn't

making it all up, it looks as if he could be. The recent resolution

of the Miller-Cooper case in which a New York Times reporter and a Time magazine reporter were not permitted

to invoke the "confidentiality" of their relationship with

a source to avoid testifying before a Grand Jury seems to me a move

in the right direction. The most that a journalist should be able to

promise a source is that his name won't be used in the story the journalist

is going to publish-not that the source's identity will be forever "our

secret." In other words, no guarantee of "confidentiality"

in perpetuity. The confidentiality that is presumed to exist between

a doctor and a patient or a lawyer and a client does not apply to a

reporter and his source. Not the same thing at all. The professional

relationships doctors and lawyers have with their patients or clients

are "personal" relationships -that is, the matter at issue

is personal with the patient or client; it involves their well being

as private individuals. The health or legal status of the newsman's

source is not what occasions their exchange: the business at hand is

not the personal, private well being of the source. The journalistic use of confidentiality

in recent times has doubtless been abused almost as often as its been

engaged. My guess is that many sources who demand that a reporter keep

their names secret are in no great danger if their names were divulged.

It's just easier for them to blab if their jobs aren't on the line.

But if what they have to say is as important and vital to the well-being

of the nation as they claim, then they would probably say what they

have to say without the promise of confidentiality. Not because they're

patriots. No-because they're blabber-mouths. They love knowing something

that no one else knows, and they love being able to prove their possession

of secret knowledge by divulging it. Sam Gejdenson, once a Democrat

congressman from Connecticut, confirmed my guess. Quoted by Jeffrey

Goldberg in The New Yorker (July

4), Gejdenson said: "The No. 1 game in Washington is making people

talking to you feel like you're an insider, that you've got information

no one else has." Every time a journalist cites an anonymous source,

he's playing into the hands of these would-be political mafiosos. Once

again, the press is duped into being a tool of the politicians. And

it's unnecessary: eventually-given enough provocation -these know-it-alls

would tell what they know without the promise of confidentiality in

perpetuity. Just to prove they have the power of knowledge. They'd say:

"Just don't mention my name in the story, okay? For now."

And a reporter can do that without undermining the legal foundations

of the Republic. All the blather by journalists about "mutual trust"

and the fate of the nation hanging, Watergate-like, in the balance is

simply so much hooey. As Goldberg hinted, the press is all worked up

over the Miller-Cooper episode because its outcome threatens to shut

off leaks, the chief source of news for the Washington press corps.

Their livelihoods are at risk, not the nation's welfare. Meanwhile, Time and Newsweek have become

hyper-circumspect about citing anonymous sources. They still cite them,

but now they explain why the source is anonymous. Here, for instance,

is a source "who requested anonymity because the FBI asked participants

not to comment publicly." Here's one who wanted anonymity "because

of the confidential material involved." Yet another, in a wholly

speculative (and therefore non-factual) story about whether GeeDubya

is "mulling" an autobiography, "declined to be named

about a subject that the White House has not discussed in public."

If it hasn't been discussed and is only being "mulled," why

do a story on it at all? Isn't this "story" little more than

pure gossip of the most trivial sort? In a terror-ridden world, who

cares whether ol' Texas Two-step is thinking of getting his life story

ghost-written? Later in the same story, the reporter quotes a publisher

"who didn't want to be named for fear of being excluded from the

selling process." Sure. And then in a Karl Rove article there are

"two lawyers who asked not to be identified because they are representing

witnesses sympathetic to the White House." In fourteen column inches

of one story, Newsweek devoted almost an inch-7% of the

story- to explaining why sources wanted their names kept out of it.

It's a colossal waste of type and space, and an affront to the so-called

intelligence of the magazine's readers. The magazine could simply carry

a disclaimer in its front matter, saying: "All anonymous sources

cited in this issue wanted anonymity either because they were afraid

they'd be fired for violating a confidence or being disloyal or for

breaking a law." That, it seems to me, would be sufficient "explanation"

for the whole enchilada. Besides, how anonymous are the "two lawyers

representing witnesses sympathetic to the White House" now? There

are presumably lots of witnesses in that category with lots of lawyers.

But the magazine's citation narrows the field considerably-and makes

every lawyer in the designated category suspect. I think Newsweek,

at least, is getting wise to the pointlessness of this dumb show.

In a recent article on Tim Russert's testimony to the special prosecutor

about the Karl Rove fiasco, the magazine side-stepped the issue by employing

such hoary journalistic devices as "reportedly" and "has

been said." If we are ready to accept the laborious explanation

for the anonymity of a source, then surely our trust in the magazine

is sufficient for us to accept shorthand for that explanation: "...

statements by White House aides-reportedly including Libby- ..." Would it increase the validation

of the truth of the article if we were told that the person or people

who told the reporter that one of the aides in question was Vice President

Cheney's chief of staff "requested anonymity because if it were

known they'd blabbed, they might lose their job"? Probably not.

We either trust journalists or we don't.

Right now, as a nation of readers, we tend not to trust them very much-probably

because they rely too heavily upon anonymous sources and publish a lot

of gossip as if it were ascertainable fact. Or as if it mattered. Probably

because journalists seem more interested in getting sensational headlines

than in reporting the complexities of solutions to public problems.

Once the news media start devoting some energy to serious reporting

on serious matters, journalism will start to rise again on the horizon

of public admiration. And once that happens, reporters can say "reportedly"

with impunity, and we'll believe them. A couple of footnits. First, as David

Broder took some pains to remind us, the Miller incarceration is not

without an irony of epic proportions. Judith Miller is the reporter

"who, in a series of influential articles before the [Iraq invasion],

vividly portrayed the threat that Hussein's weapons supposedly posed.

Only afterward was it learned that many of her 'scoops' came from Ahmed

Chalabi," the Iraqi exile whose motives were inspired by his desire

to ascend to Saddam's throne himself. Concluded Broder: "Her use

of an unnamed source in that case was a distinct disservice to the country;

had we known his name and motivation, much less credibility would have

been attached to her reports." As for Rove and his alleged innocence

of political motive in leaking the CIA status of political foe Joseph

Wilson's wife, I think the press has permitted itself to be distracted,

once again, by minutiae-in this case, the legal letter of the law. The

law in question is vague, and therefore whether Rove violated its letter

or not is even vaguer. Frank Rich, a New

York Times writer renowned for his animosity to the Bush League,

is probably right about Rove. "Of course," Rich says, Rove

deliberately trashed Wilson by making him seem the tool of a high-placed

wife. "We know this not only because of Matt Cooper's e-mail but

also because of Mr. Rove's own history. Trashing is in his nature, and

bad things happen, usually through under-the-radar whispers, to decent

people (and their wives) who get in his way. In the 2000 South Carolina

primary, John McCain's wife, Cindy, was rumored to be a drug addict

(and Senator McCain was rumored to be mentally unstable). In the 1994

Texas governor's race, [incumbent] Ann Richards [against whom GeeDubya

was running] found herself rumored to be a lesbian. The implication

that Mr. Wilson was a John Kerry-ish girlie man beholden to his wife

for his meal ticket is of a thematic piece with previous mud splattered

on Rove political adversaries. The difference this time is that Mr.

Rove got caught." Gadfly 'tooner Ted Rall also has it right: "We don't

need a law to tell us that unmasking a CIA agent, particularly during

wartime [the Bush League's favorite justification for every action,

remember], is treasonous. Every patriotic American-liberal, conservative,

or otherwise-knows that." So does GeeDubya, which is why he changed

his tune and is now saying he will fire the leaker at the White House

only if the leaker broke the law. A fine, equivocating distinction.

GRIM AND GOOSEY I