|

|

|

Opus 156: Opus 156 (February 28, 2005). We conclude Black History Month

with a review of Black Images

in Comics from Fantagraphics. Between here and there, the intervening

topics, in order, are: Covering Up -a fond consideration of The New Yorker's anniversary cover and

what it means; NOUS R Us -Garry

Trudeau on a gurney, the return of Marvel's Black Panther, Bugs' makeover,

manga's creepiness, Monty's

20th and Wee Pals'

40th anniversary (fittingly, in Black History Month);

Book Marquee -Keith Knight's latest; Down the Elevator Shaft -our perverse appreciation of Hunter S. Thompson;

Bigotry in Editoons -a wholly

wrong-headed allegation; and the aforementioned Black Images in Comics. This time, in a violent departure from our

usual soulless promotional maneuver, we run the essay on The New Yorker in its entirety, instead of breaking it off in mid-sentence

somewhere in a shameless attempt to get non-subscribers to subscribe.

So all you free-loaders get the full treatment for a change. But the

highly informative illustrations for the essay are on view only in the Member Section. We

haven't, really, reformed at all. Finally, our usual Friendly Reminder:

Remember, when you get to the Members' Section, the useful "Bathroom

Button" (also called the "print friendly version") of

this installment that can be pushed for a copy that can be read later,

at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu- Covering Up For

some among us, this season, the end of February, is laminated with a

glossy nostalgic veneer over the fate of magazine cartooning in America.

Magazine cartooning was re-constituted in the 1920s by the success of

Harold Ross's magazine, The New Yorker, the first issue of which

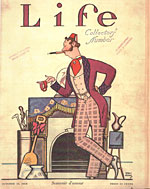

is dated February 21, 1925. The cover of that auspicious inaugural was

a perplexing drawing by Rea Irvin

that depicted a Beau Brummell-like dandy in top hat and high stock,

a supercilious boulevardier inspecting a butterfly through his monocle.

Writing of the magazine's founder's intention to establish a sophisticated

urbane journal, Brendan Gill in Here

at the New Yorker expresses astonishment at this "unexpected

and inappropriate" picture of "a preposterous figure out of

a dead and alien past.... One is baffled to see how an early-nineteenth

century English fop, scrutinizing through a monocle, with a curiosity

so mild that it amounts to disdain, a passing butterfly, could hope

to represent the jazzy, new-rich, gangster-ridden, speakeasy-filled

New York of the twenties, which Ross claimed to be ready to give an

accurate rendering of." The choice of the first issue's cover

was scarcely thought-through carefully. Ross was stuck for a subject.

The printer's deadline was fast approaching, and, after months of preparation,

still neither Ross nor any of his cohorts could think of anything appropriate

for the first cover. Finally-desperate-Ross begged Irvin to come up

with something. Irvin obligingly made an adaptation of the drawing he'd

done for the magazine's leading department, the gossipy "Of All

Things" (later entitled "Talk of the Town"). The insouciant

nineteenth century playboy, his monocle, and the butterfly. According

to Ross's wife at the time, Jane Grant, Ross thought the Irvin cover

was "the only successful feature" of the first issue. Ross

once said he hoped the prose of the magazine would eventually have the

quality (a sort of bemused sophistication, perhaps?) that he saw in

Irvin's picture. Ross was so pleased with it that he ran it again every

year on the anniversary issue of the magazine, published the last week

in February. The character in the picture was eventually christened

Eustace Tilley, but the name was borrowed from another dandy the magazine

had invented several months later for promotional purposes. The reappearance, every year at about

this time, of Eustace Tilley on the cover of The New Yorker is a reminder of the primacy Ross assigned to cartoon

illustration in his magazine, a primacy that would, eventually, have

the effect of revitalizing the single-panel cartoon by establishing

the single-speaker caption as the most effective strategy for single-panel

cartooning. (Click here

for Harv's Hindsight on the subject, too long and tedious to repeat

here.) The fondness for Eustace Tilley that I and a few other lost souls

feel was not, apparently, shared by the editors of the magazine who

followed after Ross. Lee Lorenz,

who was art editor (Ross's euphemism for "cartoon editor")

for a couple decades in the last century, told me that every year they

tried to think of something suitable for the anniversary issue cover-something

other than Irvin's drawing; but no one could come up with anything,

and so, at the last minute, they inevitably resurrected Eustace Tilley

for another encore. Then in 1993, temporarily under the editorial thrall

of Tina Brown, the magazine managed an alternative to Irvin's drawing-a

cubist deconstruction of the icon by Art

Spiegelman. The next year was even more violent a shock to traditionalist

sensibilities-a rendering of a contemporary version of the nineteenth

century fop, a twentieth century slacker, by Robert

Crumb. In the resonance between these two "New Yorkers"

and the traditional anniversary cover, we could see a wonderfully satiric

incarnation of the handbasket we'd all gone to hell in over the most

recent decades, but I still missed Eustace Tilley. Purely out of nostalia.

Eustace returned in a number of somewhat different guises over the next

few Brown years, but after she left for greener journalistic pastures,

the new editor, David Remnick, brought Irvin's Eustace Tilley back.

He's on the cover of the current anniversary issue, a double-issue dated

February 14 & 21, but with a wry vengeance. Chris Ware has produced an absolutely

delicious homage to Irvin's original in a twenty-five panel comic strip.

The strip traces the flight of the effervescent butterfly as it flits

into view at the upper right, is spotted by Eustace Tilley, who, interrupted

at reading his newspaper, inspects the insect through his monocle (Irvin's

pose, smack-dab in the middle of the cover), determines that the monocle

is smudged, cleans it with a handkerchief while the butterfly flutters

by, pausing for a moment to perch on Eustace's top hat then flies off

just as Eustace raises his monocle to his eye once again for a cleaner

look at the specimen-which, by now, is flying away beyond Eustace's

ken. Delicious, as I said. He would, however, be startled-even

outraged-by the back cover of his magazine. A full-color advertisement

for Chanel perfume, it is a photograph from the waist up of an extremely

attractive woman who isn't wearing any clothes. Except for a hat and

a long string of pearls, she is entirely naked. From the waist up anyhow.

She has demurely crossed her arms across her chest and the perspective

is from the side and her somewhat disdainful expression is scarcely

a come-on, but the nudity alone would have sent shivers of alarm up

Ross's famously Puritan spine. And the titillation doesn't end on the

back cover. Thumbing my way into the magazine, I passed half-a-dozen

advertising pages portraying beautiful women in ways that are deliberately

appealing to my prurient interest-the opening four-page spread offering

at least two photos inviting the observer to look up a woman's dress,

then, four pages on, another photograph of a man and a woman, both of

what I assume is a punk persuasion, standing close together, her with

her leg between his and close enough to his hand to suggest that in

the next instant he's going to stroke her knee, which, judging from

her smile, she would welcome in a New York minute; a score of pages

further on, we come upon two photos of a particularly seductive woman,

one of which, as before, invites us to peer up her dress. At last, as a welcome relief from all

this steaminess, we come upon several essays about New Yorker covers by the magazine's art director, Francoise Mouly. As an art critic, she

has a deft hand: grouping several covers by subject (art exhibits, romance,

out-of-town venues, reading books), she sets up a thematic context and

then touches ever so briefly on each of the artist's treatments on the

succession of covers. Mercifully, she refrains from exhaustive, detailed

pedantic discussions of the metaphysical implications of the pictures

before us. She sees what we see and no more, but she sees it just a

little before we do, and, helpfully, draws out attention to what might

otherwise, without her assistance, escape our attention. Nicely done.

Mouly has performed similar essays before, usually in little booklets

that accompany special issues of the magazine; and in 2000, she edited

Covering the New Yorker: Cutting-edge

Covers from a Literary Institution, a collection of cover images

thematically grouped with minimal textual explanation. Prior to that,

we had a monumental compendium, The

Complete Book of New Yorker Covers, 1925-1989; no text or explanation

whatsoever save John Updike's

introduction. The occasion for the Mouly essays in the current issue

is doubtless as preamble to a touring exhibition of New

Yorker covers that, in May and June, will visit Los Angeles, Seattle,

and Washington, D.C. Presumably, other cities will join the roster as

time unravels; see www.newyorker.com for updates

(if any). Towards the end of this year's anniversary

issue, we come upon an essay entitled "Mystery Man: The Many Faces

of Eustace Tilley" by Louis Menand in which he explains that the

name originated in a series of promotional pieces written by Corey Ford

in the fall of 1925 ("commissioned so that there would be something

to run on pages that advertisers were not buying," Menand helpfully

notes). Menand also wonders what, exactly, Irvin's picture was intended

to "say": "Is the man with the monocle being offered

as an image of the New Yorker reader, a cultivated observer of life's

small beauties, or is he being ridiculed as a foppish anachronism? Is

it a picture of bemused sophistication or of starchy superciliousness.

Did the readers identify with the cover, or did they laugh at it?"

He never finds an answer that he's quite satisfied with, and the five

variations on Eustace Tilley that accompany his essay, while highly

inventive, provide no illumination either. Menand says Irvin was inspired

by an 1834 drawing of a Count D'Orsay, "man of Fashion in Early

Victorian Period," that he found reproduced in the costume section

of the Encyclopedia Britannica; but if that explains the source, it

doesn't explain the attitude. Irvin had done at least one other cover

drawing of a similar character: the previous fall, for the October 16

issue of Life magazine, he had drawn a picture of a equally supercilious Victorian

gent, gazing with more artistic detachment than passionate recollection,

at a "souvenir d'amour" that he holds in his hand, a lady's

garter. Two other magazines landed in my mailbox

the same day as the anniversary issue of The New Yorker. My favorite news magazine, The Week, always has a full-color painting on the cover, usually depicting

in caricature one of the news-makers of the week's events. The painters

are an uneven lot when it comes to caricature, but I admire them for

having their hearts in the right place. This week's cover, by Darren

Gygi, is a particularly apt commentary: it shows GeeDubya pulling on

a rope attached to a statue of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the statue

is toppling-a comment on the Bush League's hope to scrap the New Deal

welfare state by eviscerating Social Security. One cannot, from the

picture itself, determine the magazine's attitude about this proposed

action; it simply illustrates, in caricatural form, one of the apparent

outcomes proposed by the plan. One could extrapolate, of course: just

as the toppling of the statue of Saddam did not, immediately, precipitate

happy domesticity for Iraq, the toppling of FDR's Social Security may

not, immediately, precipitate a happy financial future for America's

retired millions. But whether the magazine appeals to my political views

or not, it definitely appeals to my bias for cartooning as a means of

communication, and by consistently using a cartoon as its main cover

illustration, it elevates the medium. In the same mailbox was the March issue

of Playboy, which I take,

these days, chiefly to clip out the cartoons by Dedini

and Raymonde and Yeagle. (Yes, believe it or not; keep

in mind that I'm well into my dotage.) On this month's cover is Paris

Hilton, whose sole claim to fame seems to be that she videotaped herself

and turned a sexual encounter into a spectator sport. Playboy

denominates her the Sex Star of the Year, and the cover has her

flinging ceiling-ward her net-stocking-clad legs with an air of utter

abandon that The New Yorker's voyeuristic peeks may

aspire to but achieve greater sensuality by avoiding. Okay, that's about

where we came in this time, so we may as well go out with it. NOUS R US Doonesbury went into re-runs for at least the week of February

21 because Garry Trudeau,

who produces the strip only about 10 days in advance of publication

date, broke his collarbone in a skiing mishap while in Aspen, Colorado,

whence he had journeyed to accept the Freedom of Speech Award at the

U.S. Comedy Arts Festival. Despite his disability, Trudeau attended

the award ceremony, arriving on stage strapped to a hospital gurney

carried by two medics and wearing his arm in a sling. And Trudeau played

it for laughs: "I was taken out by a ski instructor," he told

Aaron McGruder (The Boondocks) who was there to present

the award. The ski instructor apparently tried to slow Trudeau's downhill

progress when the cartoonist seemed headed for a stand of pine trees.

McGruder wondered if it had been a plot to deny Trudeau the award. Never

rising from the gurney, Trudeau talked with McGruder for an hour-and-a-half

about his 35-year run as a national gadfly. The next day, he was ambulatory

once again and wiggling the fingers of his right hand (the drawing implement)

to solicitious fans. "I feel a lot better," he said-"that

looks pretty good." But he predicted it would be a couple weeks

before he'd be back at the drawingboard. ... Forthcoming (eventually):

a volume reprinting all the B.D. strips chronicling his loss of a leg

in Iraq and his subsequent rehabilitation. Produced at the request of

WRAMC, the real-world facility that attends to amputees like B.D.,

The Long Road Home: One Step at a Time is due this spring. Marvel's Black Panther, aka the African

king T'Challa, returns this month in a new series of comic books written

by movie-maker Reginald Hudlin

and drawn by John Romita,

Jr. He first appeared in 1966, arguably the first Black superhero

in comics, and his name was originally Coal Tiger but was changed before

publication, according to Andrew Smith in his comics column, Captain Comics, "for long-forgotten

reasons." A little later, when, in actual life, a political party

named the Black Panthers emerged, T'Challa's nom de guerre was changed

again, briefly, to Black Leopard. In creating this watershed character,

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby cannily avoided the usual jungle stereotypes (spears, grass

skirts, and pidgin) and made his majesty rich, intelligent, cultured,

and high-tech as well as Black. Still soaking up the accusations about

SpongeBob SquarePants, a

letter-writer in my hometown paper wrote a provocative footnote to the

allegation by "right-wing moralists" that the animated cartoon

character was "a diabolical attempt to subliminally infuse the

gay agenda on young impressionable minds." He continues: "I

wonder if these paragons of virtue have ever wondered what a man with

long hair, wearing a robe and sandals, who hung out with several other

men all the time could be suggested to represent?" ... I don't

think anyone took note of a similarly scandal-laden comics event except

editoonist Mike Luckovich of the Atlanta

Constitution, who drew a cartoon about Cathy's recent marriage in

which a curmudgeonly character says, "Like that'll convince us

she's not a lesbian." ... And in Ex

Machina from WildStorm/DC, Mayor Mitchell Hundred, erstwhile crime-fighter

cum politician, has recently come out,

so to speak, in support of gay marriage just as New York City Mayor

Michael Bloomberg did the same in real life; about the coincidental

storyline, which was developed last year shortly before gay couples

started tying knots in San Francisco, writer Brian

K. Vaughan says, "I just lucked out or I was eerily prescient."

[Thanques, John.] Hagar

the Horrible ranked first in the recent readership poll at the Fort

Worth Star-Telegram. In the survey, drawing 3,399

responses, the other top five, in order, were: The Family Circus, B.C., Bizarro, and Peanuts. The big gainer, moving from low in the rankings to 7th

place, was Baldo, the strip

about a Latino teenager and his family by Hector

Cantu with art by Carlos

Castellanos; the big losers were Blondie,

dropping from 15th to 30th, and Beetle Bailey, 5th to 33rd. ... Art Spiegelman's In the Shadow of No Towers has been chosen as the official 2005 freshman

orientation book at Lafayette College; the goal of the orientation program

is to expose students to things that make them uncomfortable and help

them work through that anxiety in an intellectual way-which, given the

horror the book recounts and the political view it espouses, certainly

seems possible with this tome. ... On February 22, Patrick

McDonnell's Mutts contributed

to awareness about Spay Day USA, a program aimed at reducing pet overpopulation

organized by the Doris Day Animal Foundation. ... In Pakistan, the aviation

artistry of Aljazeera.net's resident cartoonist, Shujaat Ali, was recognized

in the issuing of a stamp bearing his art in commemorating the 100th

anniversary of powered flight. Shujaat has been honored before, several

times, a matter, doubtless, of great satisfaction since he was, as a

youth, denied entrance at one of the top art schools in Pakistan "for

reasons I deem elitist," he says. ... Bugs

Bunny is being so-called "up-dated" for a new cartoon

series in the fall, "Loonatics," which, to avoid hysterical

objection from traditionalists like me, is set in 2772 and stars the

"descendants" of the regular old Bugs. I haven't seen this,

but someone told me the new character designs for the wascally wabbit

and his cohorts are manga-inspired. So what else is new in the most

copy-cat industry of them all? In Bill Griffith's Zippy on

February 23, Zip and his wife assume manga identities briefly, prompting

this dialogue: "Uh-oh, we've entered the infinitely creepy and

psycho-sexually disturbing world of manga! ... How did big-eyed Keane paintings and th' Japanese tendency

to mix cuteness with porn come to this? ... This weirdness is so, so

deeply repulsive that I-. ... Cheer up! It could be worse-we could be

animated." Deeply repulsive; I like that. Jay Hosler, a biologist as well as

an artist, has produced a comic book biography of Charles Darwin, provoked

by the Christian fundamentalist comics from Jack Chick which have promoted

"creationism" theories in opposition to Darwin's theory of

evolution. Hosler says one way to counter the anti-evolutionist movement

is to use comics to tell great stories. "I think Darwin's life

is a great story," said Hosler; "so why not tell it as a great

story?" One of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund's latest cases resumes the battle against

Puritan forces who find nudity obscene. Gordon Lee of the Legends comic

book shop in Rome, Georgia, was arrested for inadvertently distributing

Alternative Comics No. 2 to a minor on

during a Hallowe'en promotion where 2,200 comic books were given away.

The age and identity of the minor are not known; the complaint was filed

with the police a few days after the event. The comic book, a left-over

from Free Comic Book Day last year, featured an excerpt from Nick Bertozzi's

"The Salon" which depicts the first meeting of Georges Braque

and Pablo Picasso, the latter, as a matter of historic fact, in the

nude. No sex. Just nudity. Well, you know where that will lead.

Anniversaries: Universal Press Syndicate

reached the age of 35 this month; co-founder John McMeel is still working as chairman and president of the syndicate's

parent firm, Andrews McMeel Universal. ... Jim Meddick's comic strip Monty

(formerly known as Robotman)

celebrated its 20th on February 18; the strip's title change

several years ago reflects the greater popularity among readers of a

supporting character, Monty Montahue, a brainy albeit bumbling bachelor

who lives at home with a hairless cat and a super-logical extraterrestrial

around which other wacky regulars frolic. In the anniversary strip,

Monty and Mr. Pi (the extraterrestrial) savor the strip's funniest gag,

which, they allege, comes right after the 5,788th strip.

Book Marquee For

the latest pointed commentary on the state of the American experiment

from the perspective of a Black cartooner, pick up a copy of K Chronicles 4: The Passion of the Keef, Keith Knight's recently published collection of acerbic observations,

at www.kchronicles.com

(128 6x7.5-inch pages in paperback, $12.95 or a little more from the

website, but from there, it comes with Keef's own autograph on it!).

This one is equipped with a Foreword by Aaron

McGruder, who claims he hates Knight-"but it's a good hate,"

he continues. "It's the 'Damn I wish I had thought of that joke

but I'm not as crazy as that nigga so oh well' kinda hate." And

an Introduction by God. The latter keys off the book's title, which,

in its own dubious way, keys off Mel Gibson's movie of last spring:

the cover illo has the Keef bound hand and foot to a crucifix made of

a pencil crossed over a pen, tools of the craft. Keef's cartoonery is

a blessed incarnation of the kind of verbal-visual wizardry we fell

in love with when we saw it first at the hands of Harvey Kurtzman. Keef's style, both visual and verbal, is his own,

but the pictures, in their outrageous elastic simplicity, remind me

of Kurtzman's famed Hey, Look!

The comedy, however, is much more personal. The strip, after all, is

somewhat autobiographical-or, as the back-cover blurb alleges, "semi-autobiographical."

You need to see the pictures to fully appreciate Keith Knight, but his

manic sense of humor is evident in the afore-mentioned back-cover blurb,

from which I now quote at length: Knight's "comic strip tackles

the trials and tribulations of an African-American hipster living under

the Bush junta. A potent and poignant blend of high-brow satire and

low-brow humor. ... Weaned on a steady diet of Star Wars, hip-hop, racism,

and Warner Bros. Cartoons, author Keith Knight drew comics instead of

paying attention in grade school After graduating from college with

a useless degree in graphic design, Knight drove out to San Francisco

in the early '90s and soon developed his trademark poorly rendered,

barely thought-out, last-minute cartooning style that has amused dozens

for over a decade." Keef is also an award-wining rapper and a highly

creative social activist. Last year, his five-member band, the Marginal

Prophets, won a California Music Award in the outstanding rap album

category for its Bohemian Rap

CD. My favorite of Keef's activist campaigns is his "Black

People for Rent" plan. He and his roommate at the time made a practice

of crashing dot-com launch parties to partake of the free food and drink,

and Keef was subsequently smitten with the idea that fashionable persons

might want to have a token Black person around to give their party a

multicultural flavor. "So I put together these posters," he

explains, "-'Black People for Rent. Willing to stand around to

add diversity to parties for a fee. Conversation extra.'" He got

hundreds of phone calls, he says. "The strangest calls I got were

from Black people asking for the job," he recalled. "Now that

was an idea that wouldn't have worked as a comic. You couldn't have

written that out. It had to be 'done.'" Keef's like that. His life

is an act, an act of comedic defiance, a snickering challenge to the

sober status quo, a gesture at self-preservation. And his comic strip

is his life. In this collection, we meet his wife, who becomes an occasional

presence in the strip even though she yells at him, "What the hell

did I tell you about putting me in your cartoons?!" In promotional

materials accompanying my review copy, I read: "Keith secretly

got married at San Francisco City Hall for $99, long before S.F. mayor

Gavin Newsom married over 4,000 gay couples in the same venue, making

it trendy and un-hip." Keef did a strip about telling his mother

that he was married. She was so shocked she fell over backward, so Keef,

hoping to make amends, says, "Ha!! Just kidding, Mom-I'm gay."

Then adds, in tiny print, "Ha, not really. I married Kerstin."

That's Kerstin Konietzka-Knight, which, in a later strip, he acknowledges

as the initials KKK; his initials, however, are taken from Keith Knight-Konietzka.

Because there are so few Black cartoonists, Knight is frequently mistaken,

when he attends events for cartoonists, for Aaron McGruder. Knight doesn't

mind much, but he's offered $10 to anyone who'll walk up to McGruder

and shake his hand and say, "Hey, Mr. Knight." That's just

a taste of Keef's stuff. For a real feast, get the book, "in which

he blends political insight, whacked-out surrealism, neurotic humor,

and personal honesty." I admire his sense of humor, his graphic

style, his candor, and his antipathy to the Bush League-all on generous

display in his cartoons. Civilization's Last Outpost A

friend sent me this scrap of intelligence; dunno if it's Truth or not,

but it's nice to think it is (and sometimes that's the best way to arrive

at the Truth): "With all the sadness and trauma going on in the

world at the moment, it is worth reflecting on the death of a very important

person that almost went unnoticed last week. Larry LaPrise, the man

who wrote the song 'The Hokey Pokey,' died peacefully in his sleep at

age 93. The most traumatic part for this family was getting him into

the coffin. They put his left leg in, and then the trouble started.

..." Turns out, contrary to the oft-uttered

assumption of GeeDubya and his ilk, that this country is not founded

on Christian principles at all. The Founding Fathers were mostly Deists,

not Christians: they believed in a Supreme Being but not in the divinity

of Christ. Brooke Allen in the February 21 issue of The Nation goes on in this vein at some length, and he also quotes

from the Treaty of Tripoli (1797), signed by the President of the U.S.

at the time (John Adams) and unanimously ratified by the Senate: "As

the Government of the United States ... is not in any sense founded

on the Christian religion ... no pretext arising from religious opinions

shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the

two countries" (i.e., the U.S. and Tripoli). Starbucks has 6,409 stores nationally;

2,585 more internationally. Grounds for a caffeinated kingdom. Down the Elevator Shaft What

I know about Hunter S. Thompson

is derived largely from his appearance as Uncle Duke in Garry Trudeau's Doonesbury

-that and other caricatural portraits, usually in prose rather than

pictures, that have cropped up from time to time in the public prints.

But I know enough about his raging unconventionality to imagine that

he would have been fiendishly delighted to know that Sandra

Dee died on the same weekend he took his own life. The coupling

in death of this unlikely couple seems exactly the sort of incongruously

grotesque occurrence that Thompson would revel in: she, a perky well-scrubbed

squeaky decent example of American girlhood, who died of some sort of

kidney ailment, and he, a scabrous relic of a drug- and alcohol-wracked

crusade of self- aggrandizement, who, in a final abuse of his body,

took his own life in his "heavily fortified compound" near

Aspen, Colorado, splattering his brains out with a handgun. She was,

presumably, a reluctant participant in her death; he, the prime mover

of his. His death, in a manner of speaking, was a perverse version of

hers, just as his life was an affront to whatever she and the Gidget

she once played seemed to stand for. Cartoonist Ralph Steadman, whose illustrations in Thompson's watershed book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas established

him as a gonzo artist, recalled the gonzo journalist saying to him:

"I would feel real trapped in this life if I didn't know I could

commit suicide at any time." Said

Steadman: "I knew he meant it. It wasn't a case of if, but when.

He didn't reckon he would make it beyond 30 anyway, so he lived it all

in the fast lane. There was no first, second, third and top gear in

the car-just overdrive." Warren Ellis speculated that Thompson's

lifelong enthusiasm for substance abuse doubtless destroyed most of

the man's body. "At age 67, you don't grow back the bits you killed,"

Ellis wrote in his online column. "There's a fair chance he was

looking at years of dependency, chronic illness, and listening to his

own body die by inches. Anyone would find that frightening." Particularly

anyone accustomed to barreling along in overdrive. No wonder he shot

himself. "But how you leave the stage is at least as important

as how you enter," Ellis concluded. "And he left it alone

in a kitchen with a .45, dying in-and wouldn't it be nice if it were

the last time these words were typed together?-dying in fear, and loathing." Thompson's famed "gonzo journalism"-that

hyperbolic, vitriolic, self-centered bombast in prose-was, like a good

many innovative developments, an inadvertent conjuring. According to

Peter Guttridge in the London Independent,

Thompson was up against a deadline for an article he was supposed

to produce for Scanlan's magazine

about the Kentucky Derby. Thompson was stoned and "my mind wouldn't

work," so he started tearing pages out of his notebook, numbering

them, and sending them to the typesetter. "I was sure it was the

last article I was ever going to do for anybody," Thompson wrote

later. Amazingly, the article was hailed as "a breakthrough in

journalism." Thompson likened the experience of the ensuing excitement

to "falling down an elevator shaft and landing in a pool of mermaids."

Making himself the center of his work as a drug- and booze-crazed wild

man, Thompson set about creating his next masterwork-his own public

persona. "I was a notorious best-selling author of weird and brutal

books and also a widely feared newspaper columnist ... drunk, crazy

and heavily armed at all times," he said of himself. As Steadman

put it, "He was a real live American. A pioneer, frontiersman,

last of the cowboys, even a conservative redneck with a huge and raging

mind, taking the easy way out and mythologising himself at the same

time." No wonder Thompson became, and still is, a icon for so many

aspiring young newsmen and writers: he converted "journalist"

into the heroic action figure they all hope their writing will make

them into-a world-beating, society-reforming crusader for truth, justice

and a superior breed of grass-a galloping extravagant hope when you

consider that "writing" is a solitary, reclusive vocation

with finger dexterity the most visible "action." Most of the

obits will be written by the once-youthful worshipers at the altar of

Thompson's grandiose example, and even though their own experiences,

by now, have doubtless persuaded them of the futility of their young

hope, their admiration has not dimmed. They still see his self-indulgence

as the supreme act of civic duty. Many of the obits are likely to end

with this quotation from Thompson's landmark Fear

and Loathing in Las Vegas: "I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol,

violence, or insanity to anyone, but they've always worked for me."

But I like this, from Kingdom of Fear: "I have learned a

few tricks along the way, a few random skills and simple avoidance techniques-but

mainly, it has been luck, I think, and a keen attention to karma, along

with my natural girlish charm." Ah, Uncle Duke: you knew you were

fooling us all every bit of the way, and I salute you for mocking yourself

and revealing your secret in the same sly sentence. Those Nasty Bigoted Editoonists In

the February 21 issue of The Nation,

Richard Goldstein, a pop culture critic, turns to the recent excitement

over the alleged gaiety of SpongeBob SquarePants and other cartoon characters

and then shifts his attention to political cartooning. After considering

Pat Oliphant's ostensibly offensive caricature

of Condoleezza Rice as a big-lipped parrot perched on GeeDubya's shoulder,

Goldstein remarks that "there's a long history of bigotry in editorial

cartoons." If we go back far enough into the 19th century,

we do find some pretty vicious racial and ethnic stereotypes in editorial

cartoons. Most of them disappeared fifty years ago, though, but Goldstein

implies that they continue apace even today. Oliphant's decision to

portray Rice as a parrot is doubtless unfortunate: while it captures

what the cartoonist sees as the relationship between GeeDubya and his

Secretary of State, it also forces Oliphant to give Rice a beak, parrot-like,

which, anatomically, makes her lips prominent. His caricature of Colin

Powell, however, was scarcely racist. Goldstein goes on to recollect

other images in political cartoons-Bill Clinton "as a lubricious

bozo with a bulbous phallic nose," Bush "fitted with a tiny

schnoz and giant ears, giving him a distinctly infantile aura,"

Herblock's portrayal of Richard Nixon "as an unshaven demento."

Elaborating, Goldstein continues: "These sketches stick in the

mind not just because of their content but because of their formal qualities.

They capture something that seems essential, something we have always

felt and perhaps feared in ourselves." So far, so good: a memorable

visual metaphor does lurk in the memory and influence future decisions.

But Goldstein rattles on for another paragraph or two, festooning his

analysis with the kinds of intellectual pretentiousness that clouds

rather than reveals meaning: "... because cartoons are the stuff

of childhood, they invite us to enter a regressive, dreamy state. Movies

do something similar through lighting, framing and the subliminal flicker

of film itself. Cartoons work a bit like movies even when they are standing

still." But cartoons are not, exclusively, "the stuff of childhood."

Where does he get that? If he's a student of popular culture, surely

he is aware that adults read cartoons and that cartoons, particularly

editorial cartoons, are not "the stuff of childhood." Alas,

Goldstein turns out to be a visual illiterate when it comes to cartoons.

At one point, recollecting telling cartoon images, he remembers that

"during the 1996 [presidential] campaign, Bob Dole was often drawn

with a withered arm or shown as a patient on an operating table. This

idea was unspeakable in polite society, but," Goldstein opines,

"it probably played a part in Dole's defeat." This may be

the most extravagantly wrong-headed notion of the decade. First, the

depiction of Dole as a patient on an operating table (assuming this

picture ever actually appeared) probably had little to do with the man's

arm: it had more to do with his age. And Dole's age was often the subject

of editoon ridicule. But not his arm. I can't recall a single editorial

cartoon in which Dole's arm was the focus. In fact, I don't think any

full-time editoonist ever portrayed Dole with a withered arm. Most of

them recognize bad taste when they see it, and they know that "making

fun" of a man's war wound is probably tasteless in the extreme.

I know quite a few editorial cartoonists, and none of them can recall

ever seeing such a cartoon as Goldstein remembers seeing "often."

(One 'tooner told me he made reference to Dole's arm in a cartoon in

which his caricature of Dole says he can beat Clinton with one arm tied

behind his back; but that, it seems, is not so much making fun of Dole's

disability as it is Clinton's lack of experience. But I don't know whether

to believe this guy or not; he's such a kidder.) Given that Goldstein

thinks cartoons are exclusively the realm of childhood fantasy and that

giving GeeDubya a tiny nose and large ears makes him appear "infantile"

rather than chimp-like-in short, given his misapprehension of cartoons

as childish amusement and his demonstrated inability to "read"

cartoons with any degree of comprehension, I pretty strenuously question

whether he can accurately decipher any Dole cartoon. Moreover, I doubt

that there has ever been a cartoon about Dole's withered arm. He was

sometimes depicted holding a pen in the hand of that arm, but that was

a characteristic image of Dole; and the arm itself was never, in my

memory, shown as a shriveled appendage as Goldstein says he remembers.

Cartooning Black Images To

a greater extent than we might like to admit, the history of cartooning

in America is also a history of thoughtless and cruel racial and ethnic

imagery. Parsimonious big-nosed Jews, drunken monkey-looking Irishmen,

and lazy big-lipped Blacks were regular figures of fun in the comics

of the 19th century and well into the middle of the 20th.

And I use the expression "figures of fun" deliberately: cartoonists

drew these characters in order to make fun of them, and the comedy occurred

because they were "different." Readers laughed at the difference.

In the primitive stages of our culture, anyone who looked or sounded

"different" was deemed "funny," amusing-and therefore,

a figure of fun. The great Eugene "Zim"

Zimmerman, whose cartoons appeared in Judge

and other humor magazines c. 1880-1910, recognized explicitly this

function of his cartoons. Zim is celebrated for persistently exaggerating

human anatomy, caricaturing it, for comic effect. In my view, Zim created

modern cartooning: until his caricatural mannerisms infected the work

of others, magazine cartoons were "illustrations" (of verbal

jokes) rendered in a more-or-less realistic manner by comic "artists"

(not "cartoonists"). It was Zim's propensity to exaggerate

that made his drawings cartoons rather than illustrations. T.S. Sullivant

came along a little later and did pretty much the same sort of thing-although

his early work, like Zim's, was essentially illustrative. In full flight,

however, Zim produced a blithe and highly amusing bigfoot

caricature of humanity. And he, like most of his contemporaries,

drew racial and ethnic minorities as figures of fun, exaggerating what

he and his readers regarded as the physical characteristics of the minorities.

Writing an autobiographical fragment in the 1930s, Zim revealed that

he knew exactly what he was doing: "Forty or fifty years ago the

comic papers [as humor magazines were called] took considerably more

liberty in caricaturing the various races than they do today. Jews,

Negroes, and Irish came in for more than their share of lambasting because

their facial characteristics were particularly vulnerable to caricature."

That's how Zim explained his racist pictures to himself: their faces

were funny enough in nature to be even funnier if caricatured. This

is a cartoonist talking, not a racist. It's a man looking for comedy.

And he's looking in places where the show business of his age also looked:

in vaudeville and minstrel shows, Blacks and Jews and Irishmen were

often figures of fun. I do not claim that Zim was not a racist: by our

standards, he clearly was-he and most whites of his time. But his impulse

was towards comedy not contumely. He aimed to provoke laughter among

his readers not prejudice. He probably did both but the latter unintentionally.

In writing about this aspect of his life, Zim remarks that "only

the most stupid publishers" would publish in the 1930s the kinds

of racist cartoons everyone was publishing at the turn of the century.

In a book published in 2003, Black

Images in the Comics: A Visual History by Fredrik Stromberg, Fantagraphics

Books has done precisely that-printed picture after picture of racist

portraits of Blacks. But not for stupidly comedic purposes: Stromberg has selected images of Blacks from early

in the 19th century ("when Black characters first began

appearing in comics") through the 20th century in order

to confront the racism they embody, not to amuse readers of this volume.

"I believe that it is only by admitting to, examining, and exposing

the racism of yesterday," Stromberg writes, "that we can expose

and oppose the racism of today." Stromberg arranges his images chronologically

in order to demonstrate trends and changes in the ways Blacks have been

treated in comics. His images come entirely from comics (that is, "juxtaposed

pictures in deliberate sequence") rather than the single-panel

cartoon, a rich source of material, because he is interested in the

implications of narrative context for the portrayal of Blacks. But,

oddly, every one of his images is a single panel, torn, so to speak,

from the narrative context of a sequence of pictures so we have none

of the narrative context before us. His knowledge of the narrative context

informs his commentary, to be sure; but the images themselves are isolated

from their original context for purely aesthetic reasons, Stromberg

explains-"to make sure that each panel could be reproduced at a

satisfying size but also because I, from the very beginning, had a vision

of a book just like the one you are now holding in your hand."

The book is a tidy package, perfectly square-264 6x6-inch pages-devoting

two pages to each example. The picture is on the left-hand page, Stromberg's

commentary on the facing right-hand page. Apart from gratifying Stromberg's

aesthetic sense, this arrangement imparts to the book a carefully restrained

rhetoric. Citing only one panel from each of the works he discusses,

Stromberg manages to survey his subject without catering to racist readers

eager to rejoice over stereotypical imagery. His commentary is likewise

dispassionate. It is clear Stromberg finds racism repugnant, but he

keeps his voice lowered, invoking neither panic nor passion, and achieves

as dignified and unemotional a treatment of this scabrous subject as

we have any right to have, given our appalling racial history. "We,"

in this case, is not just the United States but "the Western world,"

Europe as well as America: Stromberg culls his examples from British,

French, German, even Swedish and Swiss publications (plus the South

African strip Madam & Eve), so his survey goes considerably

beyond American usages. Still, the emphasis is on the stereotypical

Black as found in the American tradition. And it is here that Stromberg's

efforts falter. He's a Swede, to begin with, and despite

his extensive research, he cannot be as knowledgeable of the American

milieu and its cultural heritage as someone who has been raised therein.

Without that background, he misses nuances in the flotsam and jetsam

of the American culture. In a discussion of Western comics, for instance,

he focuses on a Western produced in Italy, not in the U.S., and after

telling us that in his example the conflict involves a Black man who

insists on entering a whites-only saloon, Stromberg surmises that the

inspiration of the 1978 story was Rosa Parks' refusal to sit in the

back of a bus in 1955. Maybe. More likely, however, the story was inspired

by the sit-ins staged throughout the American South to integrate lunch

counters and other such establishments-precisely, in other words, what

the Black in the Italian story seems bent on doing. Stromberg further

speculates that Blacks may be missing from Western comics (not to mention

Western movies, pulp magazines, and novels) because "the genre

represents a romanticized reality in which racial conflict is exclusively

the domain of Native Americans and white settlers." In a manner

of speaking-that is, loosely-perhaps so; but I think Stromberg is just

being polite when he poses a preference for romance over reality as

a cause for leaving Blacks out of the Old West. More likely, Blacks

were excluded from Westerns for the same reasons they were excluded

from all of American history except in their roles as happy, carefree

slaves in the ante-bellum South. The effort by the white population

was a mostly conscious endeavor to deny to Blacks any significant role

in American history and culture as a backhanded way of affirming the

racial inferiority of Blacks (thereby "excusing" white animosity

towards Blacks). As a historical phenomenon, the Western's racism was

somewhat sublimated: racism in the Western was framed in terms of a

struggle between civilization (ranchers, cowboys) and savagery (Native

Americans). In that equation, the central dramatic conflict of Westerns

(even those that dealt, instead, with the conflict between good gunslingers

and bad) would have been diffused by the introduction of a competing

conflict having its origins in the "peculiar institution"

of slavery in the South. The average potboiler can encompass only one

conflict at a time. Moreover, at the time the Western was being conjured

up out of the dime novel fantasies of the late 19th century,

most of the white population of the country probably didn't realize

that former slaves ever ventured "out West." Our awareness

of this suppressed fact of our history, like our recognition of the

genocide inherent in our treatment of the Native American population,

is a relatively recent awakening. Stomberg's short essay on the Western

ignores the crude beginnings of the genre and seems to assume that the

Western was concocted in the full illumination of our present recognitions

and realizations instead of seeing the contemporary manifestation as

an outgrowth of a much more primitive cultural tradition that, in an

on-going developmental progress, has reached the present stage. Stromberg's

myopia on the subject of the Western does no drastic violence to his

survey of racism in comics, and he does call attention to the omission

of Blacks from the American mythology of the Western, but what I've

supposed is his excessive politeness does, in effect, excuse the racism

underlying the Western by avoiding mention of its less humane causes. But it isn't decorum or cultural unfamiliarity

that explains Stromberg's inclusion of Pat Sullivan's Felix the Cat in this collection. It is, rather, simple

misapprehension. Felix, Stromberg strenuously suggests, is a stand-in

for Blacks. His arrival at this conclusion is very nearly a satirical

indictment of the sort of tunnel vision peculiar to a certain kind of

compulsive scholarly inquiry. Because Felix is black, he is the "strip's

principal Black image" and must perforce be a "proxy"

for an African-American presence in the strip. "As it became too

problematic to present traditional 19th century Black stereotypes

in the 20th century, it can be argued that aspects of the

stereotypes were transferred to funny animals such as Krazy Kat, Felix,

and later Mickey Mouse"-just because all these critters are black.

Yes, that can be argued; but the argument is fanciful in the extreme.

It is astounding to find in an otherwise serious tome this preposterous

formulation. Stromberg bases his conclusion partly on the blackness

of the characters he names and partly upon the dubious connection between

Felix and a pickaninny comic strip predecessor created by William Marriner, a "Sambo"

character named Sammy Johnsin. Since both characters have diminutive

bodies with comparatively large black heads and since Pat Sullivan once

assisted Marriner on the Johnsin strip, it follows, according to Stromberg,

that Felix was a subsequent reincarnation of the Sammy Johnsin character,

transformed by the emerging social conscience of the nation, into an

animal. "It might be too bold," Stomberg admits, "to

say that Felix is just a deracialized, feline Sambo Johnson [sic], but

Felix's narrow escapes often do tend to rely on Sambo's brand of dumb

luck." Yes, it might be too bold; but he does it anyhow. Several

errors cluster around Stromberg's theorizing. First, the similarity

of appearance between the two characters is scarcely a decisive determinant.

Neither is the fact that Sullivan assisted Marriner; after all, it was

Sullivan's assistant, Otto Messmer,

who actually created the Felix

the Cat comic strips, and any "narrow escapes" Felix has

should be attributed to Messmer, not Sullivan. Finally, the similarity

of the Sambo and Felix characters is more an outcome of the peculiarities

of early animation than of racial identity. The Felix comic strip was

a spin-off from the character's earlier success as an animated cartoon

character; and Felix was a black cat because it is easier to animate

solid black forms than outlined forms. The fact that Sambo and Felix

had round heads proportionally too large for their tiny bodies is the

coincidence of cuteness. Sambo was tiny because tiny was cute. Felix

was tiny for somewhat the same reason (and also because cats are smaller

than people, and there were people in his cartoons). But when Felix

began, he had a cat-shaped head, somewhat angular. This was too difficult

to animate, so it was morphed into a round shape by an animator named

Bill Nolan. That also made the character cuter. "Nolan made the

cat round all over," said a contemporary witness to the re-design.

"The rounded shape made Felix seem more cuddly and sympathetic,

and circles were faster to draw, retrace, ink and blacken" (from

Felix: The Twisted Tale of the

World's Most Famous Cat by John Canemaker). Still, if Felix's behavior

perpetuated a stereotypical Black behavior, there might be some grounds

for Stromberg's conclusion. Alas, it doesn't. Felix is not very often

extricated from dilemmas by "dumb luck." In fact, the thing

that distinguishes Felix from most other comics characters is the canny

inventiveness to which he is prompted by the predicaments in which he

finds himself. In short, there seems to be absolutely nothing in the

history of Felix the Cat to support Stromberg's assertions about him

(or about Krazy and Mickey) except the commonality of color. Not enough. In his conclusion, Stromberg opines

that realistic and sympathetic Blacks, as opposed to stereotypical caricatural

Blacks, have emerged in comics because comics have graduated from juvenile

to adult literature. Without comics intended for adult readership, he

implies, there would be no realistic Black portraits in comics. Aiming

for adult readers, creators could "develop both stories and characters

with more nuances." This occurrence is "linked," he says,

to the "1960s movement for a more equal world." About that

time, too, it was "especially in the U.S., 'hip' to raise questions

of race in comics." I agree that nuanced portraits of racial and

ethnic minorities are made more possible in comics intended for adult

consumption, but that connection is not a cause-and-effect relationship.

Racial matters have surfaced in all forms of popular culture because

of the gradual maturation, so to speak, of the society itself, its willingness

to acknowledge the sins of its past and to undertake to correct them

and abandon them. The landmark case of Brown vs. Topeka that ostensibly

ended separate but equal educational facilities, ushering in much of

the impulse to civil rights that has characterized the last 50 or so

years of our history, could not have taken place in the 1930s. Maybe

not even in the 1940s. Before we could have Brown vs. Topeka, other

aspects of our culture needed to change. Perhaps we needed World War

II with its Black combat units, however few they were, to pave the way

for a campaign for equal rights. American Blacks in combat served equally

to whites, got shot equally, shed blood equally, and died equally. Why

shouldn't they get to live equally in the country they were fighting

for? Perhaps we needed to pass through that crucible before we could

confront the other fires of segregation and discrimination. In any event,

I doubt we could say, with assurance, that adult comics are responsible

for Blacks being treated realistically in comics. Adult comics doubtless

made that treatment more likely in comics, but social advances other

than an expanded market niche are more responsible for the attitudes

espoused. Stromberg's survey covers a great deal

of ground. U.S. readers will not discover much they recognize in Stromberg's

roster of European comics, which, because of the colonial history of

European countries, tend to portray Blacks in "native" roles

rather than roles in contemporary continental society. His citations

of American comics include Richard

Outcault's Poor Li'l Mose

and the Yellow Kid, Winsor

McCay's African Imp in Little

Nemo, the tropical island population in The

Katzenjammer Kids, maids and other servant types in the early versions

of such strips as Moon Mullins,

Hairbreadth Harry, and Gasoline Alley as well as such relatively

recent creations as Wee Pals,

The Black Panther, Franklin in Peanuts,

Lt. Flap in Beetle Bailey, Quincy,

Curtis, Friday Foster, Luke Cage, and

Static and the Milestone project. Some American creations seem curiously

omitted-the strips Herb and Jamaal

and Jump Start, for instance.

And Ollie Harrington's great panel cartoon

character, Bootsie, is missing. (On purpose: as we've seen, Stromberg left out all panel cartoon representations

of racial images.) So is Hank

Ketcham's abortive attempt to introduce a "cute" Black

kid into Dennis the Menace, a development it might

have been illuminating to contemplate in such a survey as this. But

these are quibbles, and Stromberg quite rightly announces that he is

not attempting a comprehensive catalog of how Blacks are portrayed in

comics. He intends a "personal reflection," he says, and the

chronological organization prompts a conclusion. But neither content

nor conclusion is intended to be all-encompassing. All along the way, Stromberg's discussion

is steeped in measured reasonableness. While that contributes to the

rhetorical restraint that distinguishes the work, it also has occasionally

the effect of diluting the verdict. He acknowledges that Robert Crumb's caricature of Angelfood McSpade is a racist stereotype,

but he effectively excuses it by speculating that Crumb "uses these

charged images to provoke a reaction from the reader and force them

to make up their own minds about their attitudes toward racism."

Probably true. But the use of the imagery perpetuates racist stereotyping

regardless of Crumb's purposes. In his discussion of the Black images

in the Japanese manga of the revered Osamu

Tezuka, Stromberg reports that after Tezuka's death, an anti-racist

effort in Japan protested his stereotypical Africans, which the cartoonist

had intended "as a gag." The publisher "decided not to

alter Tezuka's comics in the reprints but added a disclaimer saying

that while some images were drawn in a less-enlightened era, Tezuka

himself had been adamantly opposed to racism in any form." Stromberg deals with Will Eisner's Ebony in much the same fashion.

He quotes Eisner's oft-repeated explanation that the Ebony character

was a comedic product of the traditions of humor afoot in the late 1930s

and 1940s. "I realized that Ebony was a stereotype because I drew

him in caricature," Eisner said, "but how else could I have

treated a black boy in that era, at that time?" That is quite true

and, as far as it goes, inarguable. (There is a better way to treat

a black boy, but not if you want to begin with a caricature.) Stromberg

then goes on to accept Eisner's argument that when he returned to the

Spirit after World War II, he gave Ebony a "more pronounced and

equal role" in the feature. Eisner also introduced other Black

characters who were more dignified than the comical kid. But Ebony himself

did not change as much as Eisner claims. If Ebony changed, it was a

development subtle to the point of vague. Eisner unquestionably thought

there'd been a change, but he was probably blinded by his affection

for the character: because he liked Ebony, he valued him more than,

probably, the average reader did, and because he valued Ebony, Ebony

seemed more important than, objectively considered, he was. I like Ebony,

and I think he served in no insignificant way to develop an aspect of

the Spirit's personality that would never have surfaced without him-a

sort of fatherly compassion. The Native American kid, Little Beaver,

serves somewhat the same function in the Fred Harman's Western comic strip, Red Ryder (which is discussed at greater length here

in our Hindsight Department). In the early Spirit stories, Ebony is

usually comic relief, pure and simple; he appears in the stories at

the beginning and/or at the end to provoke a laugh. By the end of the

1940s, Ebony has become integrated into the storyline itself; his role

serves the plot as well as the comedic muse. In the post-WWII Spirit

stories, Ebony is still a humorous character, but the humor isn't as

broadly stereotypical as in the pre-WWII stories; the emphasis is more

upon the relationship between the Spirit and Ebony. This relationship

had started to emerge even before the war. Again, it was doubtless inevitable:

as Eisner delved deeper and deeper into his characters, his regard for

them grew, and the only way for him to display his regard for Ebony

was to keep him onstage, which resulted, in the normal course of devising

narratives, in developing a relationship between the Spirit and Ebony.

In Eisner's remembrance of this circumstance-which in his memory occurred

after the war-Ebony seems more important, more dignified. That's a legitimate

analysis of the material from the creator's point-of-view even if the

material itself doesn't proclaim the same verdict very loudly. I don't mean to suggest that Eisner,

in his many declarations of Ebony's improved post-WWII status, deliberately

misled us or misrepresented what happened. In fact, I'm sure there was

no attempt whatsoever to misrepresent. His perception as a creator of

the character is merely different than ours as readers. I accepted Eisner's

claim, as most of us did, because we respect his achievement and like

the man. But his perception, extracted mainly from memory, is as flawed

as anyone's is likely to be when memory is called as the chief witness.

Eisner was not at all hesitant about admitting to this all-too-human

flaw. Some years ago, I talked with him about Jack

Cole's invention of Midnight, an obvious rip-off of the Spirit conjured

up at the behest of Eisner's publishing partner, "Busy" Arnold.

Eisner remembered something that no facts could be discovered to support.

Eisner was entirely philosophical about the waywardness of memory: "I

learned about memory," he once told me, "when I was doing

Heart of the Storm [his autobiographical graphic novel about anti-Semitic

bigotry]. Your life is a seamless thing, and you try to remember it

by recollecting incidents along the way. And sometimes, those incidents

don't quite fit in." His memory of Ebony doesn't quite fit in:

Ebony began changing before the war, and the change was not as marked

as Eisner remembers it being. But that doesn't mean it didn't happen. Our alarm about the grotesquely racist

images of Blacks in comics of the past is understandable but not, always

and everywhere, entirely rational. It seems to suggest that we would

be better people if we were to shut the door firmly and forever on this

aspect of our past. Commendable

as a sympathetic gesture towards establishing a common multiracial multiethnic

humanity, the cultural blind spot that might result would probably not

advance the cause much. "If you know history, you'll never be doomed

to repeat it," says William

Foster, an African-American comics historian and professor at Naugatuck

Valley Community Technical College in Waterbury, Connecticut. Foster,

whose book Looking for a Face Like Mine is due out

this summer, has created a traveling exhibit on the subject, "The

Changing Image of Blacks in Comics." Interviewed recently in Scoop, the online magazine from Diamond, Foster said: "Everyone

[has] talked about Ebony with Will Eisner and how controversial it was.

But why would I be mad about that? It was the forties. Besides, we can't

be in a place where we're always the heroes. And I've seen some people

who are not Black [provide] amazing images of Black people that I'm

very proud of. ... I once watched a documentary called 'Black History:

Lost, Stolen, or Strayed.' Bill Cosby narrated it. And there's a quote

in that film: 'Getting mad at historical images that portray Blacks

is like throwing a rock at a mirror because you don't like what you

see.' Sure, [a lot of historical images] are not flattering by the standards

of 2005, but they were [what they were]. ... Sometimes, we have to have

that discussion. Where we've been is one thing. Where we are is another.

And where we're going is something else altogether." In Black Images, Stromberg's self-imposed limitation-tailoring his text

to fit the two-page format of each entry in the book-prevents him from

extending his discussion to the lengths I have wrought here. And that's

a fault but not a racist sin. Despite the shortcomings I've been dwelling

on, the book as a whole is a valuable if interim achievement. We have

no other survey of this kind. Brief and cursory though it is, it points

in the right directions. Stromberg demonstrates the formation of the

stereotypical Black image in the earliest comics he cites, shows how

persistent that imagery has been over decades but maintains that it

has changed in recent years, and concludes that while we may pride ourselves

"on having come a long way in fighting racism, cartoonists still

seem to have a problem when treating ethnic minorities. It is inherent

in comics to simplify in order to communicate, and in that process it

is easy to resort to stereotypes." Concluding with a modest bibliography,

his survey is not comprehensive and his analyses are not exhaustive,

but he's right as far as he is able to go within the limits he's imposed

upon the book. The book's Foreword by Charles Johnson is very nearly alone worth

the price of the book. Johnson, a professor of English at the University

of Washington in Seattle, is a novelist (his Middle Passage won the National Book Award in 1990), literary critic,

screenwriter, philosopher, and one-time cartoonist. He launched his

cartooning career while still a student in college at Southern Illinois

University, where he produced two comic strips for the campus paper

while also doing political cartoons for the city's paper, The

Southern Illinoisian. Two books of single-panel cartoons are the

first publications on his vita: Black

Humor (1970) and Half-Past

Nation Time (1972). Both reflect the assertive Black pride that

had recently dawned upon the national horizon as well as scornful ridicule

of die-hard racists. Johnson is uniquely equipped to ponder

the subject and Stromberg's treatment of it, and in just thirteen short

pages, he shames us for our racist past, destroys flabby rationales

that excuse stereotyping, and describes a "day of enlightenment"

that he fervently hopes is coming. He writes: "While the cartoonist

and comics scholar in me coolly and objectively appreciated the impressive

archeology of images assembled in [this book], as a black American reader

my visceral reaction to this barrage of racist drawings from the 1840s

through the 1940s was revulsion and a profound sadness." These

stereotypical images exist, he goes on, because cartoonists have been

too lazy to invent alternatives to them. It does no good to reason,

with D.H. Lawrence, that because "I am not a nigger, I can't know

a nigger"-can't therefore understand him or accurately depict him.

Precisely that-knowing and understanding "the other," the

personality outside our own-"is the very point of art, comic or otherwise,"

Johnson all but shouts in a clarion affirmation of art that is simultaneously

a passionate rejection of racism masquerading as hapless humanity. Johnson

rejects the notion that an artist is "merely a creature of his

time," the embodiment as well as the victim of the prevailing prejudices

of his day from which none of us can successfully escape. He recalls

lessons from "the Jewish cartoonist/writer Lawrence Lariar"

that were devoted "to the importance of avoiding stereotypes when

drawing nonwhite characters and individuating them as fully as possible."

As a result, he can't see Crumb's Angelfood McSpade as "avant-garde

or provocative in any positive way." His point, he says, is that

these images of Blacks are evidence of "the failure of the imagination

(and often of empathy, too) and tell us nothing about black people but

everything about what white audiences

approved and felt comfortable with in pop culture until the 1950s when

relentless agitation by the NAACP and Civil Rights workers finally made

them unacceptable, hugely embarrassing for citizens of a democratic

republic, and relegated them to the trash heap of human evolution."

None of these stereotypical images were devised, he reminds us, with

the idea that Black people might see them and find them entertaining;

the audience was always envisioned as being white. (Any cartoonist deploying

a stereotype might well consider how persons his stereotype depicts

might react to the portrait.) Johnson's argument is neatly logical

and rhetorically persuasive, but I'm afraid part of it, the claim that

the artist can transcend his time-his milieu, his culture-reflects more

noble aspiration than practical understanding of the human condition.

Escaping one's cultural milieu is easier said than done. We are all,

artists and citizens alike, prisoners of the cultures we have been born

into. Even in this enlightened time in which presumably scores of reasonable

people share Johnson's view and his aspiration, we cannot see much evidence

that artistic endeavors can transcend their times as Johnson calls upon

art to do. There is some evidence; not much. It is clearly not impossible;

it is just awfully difficult. And so it is not alarming to realize that

it is seldom achieved. Still, Johnson's assessment is a trumpet call

to artists everywhere to attempt more than they've attempted in the

past. Writing about the most recent, more

realistic, portraits of Blacks in comics, Johnson acknowledges that

"this is progress in the portrayal of blacks since the 1940s-comics

that, as transitional works, point to greater artistic possibilities.

But I feel that even these more realistically written and drawn comics

are still reactive, self-consciously fighting against 'cartoon coon'

images from the period of Jim Crow segregation. ... Like Stromberg,

I sense that something important-the next Great Leap Forward-is still

missing in this popular medium. And what might that be? Well, try this:

I wait for the day ... when my countrymen will accept and broadly support

stories about black characters that are complex, original (not sepia

clones of white characters like Friday Foster or Powerman), risk-taking,

free of stereotypes, and not about race or victimization. Stories

in which a character who just happens to be black is the emblematic,

archetypal figure in which we- all of us-invest our dreams, imaginings

and sense of adventure about the vast possibilities for what humans

can be and do-just as we have done, or been culturally indoctrinated

to do, with white characters ranging from Blondie to Charlie Brown,

from Superman to Dilbert, from Popeye to Beetle Bailey." It is possible, actually. Despite the

difficulty-regardless of the dearth of evidence of success at such artistic

endeavors-it is possible. The movie "The Bodyguard," for example,

presents us with a relationship between an African-American singer,

played by Whitney Houston, and her white bodyguard,

Kevin Costner, in which race

is never mentioned. They become lovers, and the story is about that

relationship; but their racial difference is never mentioned. Nowhere

in the movie is race an issue. The human condition is being examined

and tested, but not as a racial matter. So it's possible. Rare though. I don't agree that simple intellectual

and imaginative lethargy is largely responsible for the perpetuation

of stereotypical racist images in comics. (And neither does Johnson.

In pouncing upon laziness as an excuse for not junking stereotypes,

he is reacting to a standard argument; he's not assessing causes in

any globally analytical way.) Fear and hatred are at work, too-hatred

born of fear-as they have operated throughout the grim and sad and terrible

eras of white America's enslavement to the institution of slavery and

its accompanying ugly bigotry. Zim's rationale is also clearly at work-Bug-eyed

Blacks with liver-lips seemed to be funny to white audiences, and a

cartoonist aims to provoke laughter. The Sambo figure as the American

Jester has a long and distinguished career as one of the few indigenous

icons of American culture. But that is a topic for another day. For

today, Stromberg's book garnished with Johnson's no nonsense Foreword-perhaps

only as enhanced with Johnson's essay- is a worthy addition to

the shelf of scholarship on comics. For other information for that shelf,

visit Tim Jackson's Pioneering

Cartoonists of Color at www.clstoons.com

and Oma Bilal's Museum of

Black Superheroes at www.blacksuperheroes.com.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |