|

|

|

Opus 155: Opus 155 (February 13, 2005). The rabbit feat this time celebrates

Black History Month with a short reprise of the career of one of the

great African-American cartoonists, E. Sims Campbell. That's towards

the end. The intervening topics and their order are as follows: Nous R Us -more comic book character movies, Disney's Uncle Remus

may make a come-back, The Simpsons book, Stan Lee and the "60 Minutes

Wednesday" gaff, and the Spirit movie; Funnybook Fan Fare -Shanna,

Concrete: The Human Dilemma, Gun Fu, The Wicked West, Wyatt Earp: Dodge

City, and Angeltown; Comic Strip Watch -Zippy's secret, Cathy's wedding, Ted Rall and Pat

Tillman again, Garry Trudeau and Honey (is she Peanuts' Marcia reincarnated?),

and Prickly City dropped at

the Chicago Trib; Civilization's Last Outpost -why models

walk that way and termite flatulence; and, after Black History Month,

a little punditry. Finally, our usual Friendly Reminder: Remember, when

you get to the Members' Section, the useful "Bathroom Button"

(also called the "print friendly version") of this installment

that can be pushed for a copy that can be read later, at your leisure

while enthroned. Without further adieu-

NOUS R US Comic

book heroes aren't doing as well at the motion picture box office as

it seemed they would in the first flush of financial excitement over

the X-men and Spider-Man movies. According to Andrew Smith at Captain Comics, "Electra" never got higher than fifth in

the top ten box office hits and dropped off the list altogether after

three weeks; and he goes on to note that "Catwoman" was a

financial as well as a critical flop, ditto "Daredevil" and

"The Punisher," and "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen"

"barely covered its all-star salaries." Moreover, "comic-book-like

movies such as 'Matrix Revolutions' and 'Van Helsing' imploded on impact."

John Lippman at the Wall Street Journal wonders if superheroines

will ever match superheroes in box office appeal. And Robert Weinberg,

a former Marvel writer, opines that "guys like girls dressed up

in sexy outfits, but when it comes to action, they still prefer the

men doing it." And Monohla Dargis in The

New York Times thinks there's something "disturbing, even disrupting,

about a woman who walks (or flies) alone." Nuts. "Alias"

on tv still reigns supreme; "Kill Bill" movies are doing all

right. Ditto the first Lara Croft movie. Discounting female action characters

because they're female is sexist tripe. I don't think Hollywood is finished

milking these cash cows yet, and here's Vincent P. Bzdek at the Washington Post to second the motion: No fewer than 18 big-budget movies

scheduled for release this year were inspired by comic books or superheroes,

including, this spring and summer, "Batman Begins," "Fantastic

Four," "Constantine," "Sin City," "Ultraviolet"

and "Sky High." The boom was already well underway last year.

Eight superhero movies made it to multiplexes in 2004, led by two of

the year's five biggest box-office draws, "Spider-Man 2" and

"The Incredibles." Together, "Spider-Man" (2002)

and "Spider-Man 2" have made more than $1.6 billion in the

United States, making them the sixth and eighth most popular movies

ever here. And the hero worship doesn't seem likely to stop any time

soon. "Superman Returns," under the direction of Bryan Singer

("X-Men," "X2"), is scheduled for release in 2006,

the first new Superman movie in 20 years. DC Comics hopes to release

films of "Wonder Woman," "The Flash" and "Shazam"

in the next couple of years. Its rival, Marvel Comics, has ambitious

plans to bring more of its wards to the big screen, too, including "Captain

America," "The Phantom," "Ghost Rider," and

sequels-or additional sequels-to "Hulk," "X-Men"

and "Spider-Man." Disney's famed (and infamous) "Song

of the South" may get released on DVD sometime in the near future.

The movie has been kept locked up for decades because of the "happy

darkie" portrayal of Uncle Remus, whose tales of Br'er Rabbit in

animated sequences spice up the otherwise live-action flick. I obtained

a bootleg copy of the film some years ago, but I'd love to have a copy

that isn't blurry: the animation sections are nifty. The rumor about

the possibility of the DVD, by the way, is promulgated at Mark Evanier's

www.povonline.com, one of

the Web's happiest and most informative sites; we recommend it unreservedly.

... "The Simpsons," as every fan of the show knows, is the

10th longest-running tv series ever. Chris Turner, one of

the fan-addicts in question, has authored an exhaustive tome about the

show, Planet Simpson: How a Cartoon Masterpiece Defined a Generation, which,

Louis Jacobson tells us in the Washington

City Paper, reveals that Turner believes the show "has embodied,

even driven, nearly every major cultural trend in the past decade and

a half," making it "by far the most important cultural institution

of its time"; it is, Turner allows, impossible to imagine contemporary

pop culture without it. ... Cracked,

the longest-lived of the Mad imitations,

is still alive, apparently; it was recently purchased by the Teshkeel

Media Group, a Kuwait company that develops original material for children

throughout the world, "with a focus on the Arab and Islamic markets."

... Graphic novels got a three page fold-out spread in Time for February 7; the spotlight falls on Paul Hornschemeier, Marjane

Satrapi, David B., Rieko Saibara, and Joann Sfar, with an aside to Art

Spiegelman. ... "The Incredibles" collected top honors at

the 32nd Annie Awards, winning best animated feature, best

directing, and best voice acting. ...

Qkids, a new magazine of short stories, articles and comics (sounds

a bit like Pilote or Spirou) is published from Sweden but edited

in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and sold throughout the Arab world. Its aim,

according to editor Fahd F. Al-Hajji, is "to wean Muslim children

away from satellite tv and expose them to Islamic views." Muslim

children, he noted, generally lack a reading habit: they are always

glued to tv, which is unhealthy. ... In Greece, the Austrian author

of The Life of Jesus, a comic book that portrays Jesus as a hippy, was

tried in an Athens court and found guilty of blasphemy; he was given

a suspended sentence of 18 months, but various writers' groups are protesting

because they fear this case will discourage other artists and publishers

working on similar books-"a serious blow to freedom of expression

in the country," they said. When a U.S. District Court ruled in

favor of Stan Lee and said

Marvel had to pay him 10 percent of the profits from Marvel Enterprises

film and tv productions, "60 Minutes Wednesday" pounced on

the event, regurgitated a Bob Simon interview of some months ago, and

added fresh material to it. Lee, obviously reluctant to go into much

detail, said he was "hurt" by the company's refusal to pay

him what his contract called for and brought his suit with reluctance.

Simon's questions and comments, clearly intended to heighten the drama

of this incident, kept referring to the characters Lee created and how

he was, in effect, being robbed by Marvel, who was going to the bank

with earnings gained from the sweat of his creative brow. Immediately

after the program aired, objections burst forth about the injustice

of Lee's taking all the credit for creating the characters that populate

the Marvel Universe. "It's amazing that he walks away with all

the credit and all the money for some of the creation of these characters,"

said Robert Katz, nephew of Jack

Kirby, who probably contributed at least as much to the ambiance

of the Marvel Universe as Lee. "The artists who did the lion's

share of the creation have walked away with absolutely nothing,"

he added. Lee, it looked like, was once again taking more than his legitimate

share of the credit-and this time, he was going to go to the bank, too.

All this holy ire springs from some vague suppositions, though; and

maybe Lee isn't the self-serving monster he seems. First, I've seen

recent interviews with him (by Larry King, for one) in which Lee studiously

avoids taking sole credit for Spider-Man and the like: he interrupted

King and expressly disavowed any solo creation, saying he was "co-creator"

with a succession of artists. So before jumping all over Lee for his

performance on "60 Minutes Wednesday," we might take a breath

and assume that the show's editors may have cut out any such disavowals

because they would tend to dilute the intensity of the injustice they

were promoting for the sake of the aforementioned scandalous high drama.

Secondly, without having actually seen the contract at issue, my assumption

is that it is based upon Lee's long service to the company as editor

and publisher, not, per se, for creating the characters. Kirby and Steve

Ditko and the others did not work as long or in as many capacities for

Marvel as Lee did; they are, in any just distribution of material gain,

entitled to much less. Finally, Lee's contract calls for a share in

the profits from the various

enterprises involving Marvel characters. The most conspicuous of these

are the movies, but, as almost all of us know, movies never make any

profit; their accounting systems see to that. In fact, Marvel has already

said that it has not realized any profit from the Spider-Man movies

or the rest. So when Simon asked Lee what he'd do with the tens of millions

he stands to receive and Lee said, jokingly, that he could always use

a new pair of sneakers, he was being more realistic than Simon or "60

Minutes Wednesday." In The New Yorker of January 17, Margaret Talbot writes about manga at

some length. I'm not a fan of a lot of the manga now littering the bookstore

shelves. There's something just too precious about the artwork, too

cute, too delicate and affected and, for much of the stuff now selling

in this country after the introduction of Lone

Wolf and Cub years ago, much much too saccharin. Lone

Wolf was okay; and some of the other manga mannerisms I like. But

the wispy lined, big-eyed concoctions-no, thanks. Talbot tells us that

"tens of thousands of Hello Kitty products-from pink vinyl coin

purses to packets of 'sweet squid chunks' bearing her wide-eyed likeness-is

a billion-dollar business." And, she goes on, "One reason

the Japanese are so good at this kind of thing is that many adults in

Japan are curiously attuned to cuteness. Even in a cosmopolitan city

like Tokyo, kawaii -or 'cute'

culture-is everywhere: road signs are adorned with adorable raccoons

and bunnies; stuffed animals sit on salarymen's desks' Hello Kitty charms

are offered for sale at Shinto shrines." I'm not opposed to "cute,"

mind you; in fact, some kinds of "cute" I like. But not, apparently,

the "cute" of the Far East. What's more, there's something

creepy about the manga books featuring big-breasted women with little

girl faces. Maybe Lolita was big in Japan. That Mike Uslan Spirit movie I alluded to last time-yes, he's apparently

working at it. In an interview last September with Chris Mason on superherotype.com,

Uslan admitting that he's talking to lots of people about the film and

that there's a "production team" that includes Deborah Del

Prete and Gigi Pritzker, Ben Melniker, Steve Maier, Linda McDonough

and F.J. DeSanto. By then, Uslan had also discussed the project with

Eisner. "To be true to Eisner," he said, "the film must

be highly stylized and crafted. ... The first time I saw 'Blood Simple,'

for example, I knew that the Coen Brothers could execute a great Spirit

film." ... "Will Eisner: The Spirit of An Artistic Pioneer"

is a documentary being directed by Andrew D. Cooke, brother of the co-producer

Jon B. Cooke, who is working

up an issue of his Comic Book

Artist devoted to Eisner, as is

Roy Thomas at Alter Ego,

No. 48, which was already in the works when Eisner died; the issue will

focus on Eisner's years at Quality Comics, with tributes from scores

of people. The Comics Journal is also coming out

with an Eisner issue, and Wizard's

March issue contains an Eisner profile. Strange how so much of this

was in the works before Eisner died, a measure of his emergence as a

graphic novelist, I reckon.

Funnybook Fan Fare Frank

Cho's long-awaited Shanna for

Marvel has arrived, and it's a beaut. Touted as a pin-up lover's delight,

the actual product is much much more. Cho is a master of the medium,

and his storytelling here is fine-tuned for pace and suspense and emotional

impact. The opening sequence is highly cinematic, imagery progressing

from utter darkness to laboratory lumination in suspenseful stages.

(And the piece of pipe that opens the door shows up again six pages

later when Doc breaks the glass cage that keeps Shanna alive but in

suspended animation.) As for Shanna's epidermis, it's almost everything

we've been led to believe it would be. Yes, she's nekkid, but because

the Marvel moguls moved the book from Adult to PG-13, Cho had to re-visit

his artwork and cover up the nasty bits. It's a shame, kimo sabe. And

it's also something of a joke: Cho has "arranged" hunks of

the glass cage's two-inch-thick glass to cover Shanna's derierre, and

in his most spectacular nude shot, bubbles are artfully placed to provide

bikini coverage. Tiring of this coy pictorial maneuvering, he at last

simply wraps the zaftig jungle queen in an old horse blanket. The very

artificiality of the masking devices up to then serve to flip the bird

to Marvel's cringing editors. But the best joke of the first issue-Doc's

signal that he's okay under Shanna's unconscious nekkid body-survives.

In the second issue of Concrete: The Human Dilemma, the human

dilemma- propagation and population explosion as a consequence of sexual

love-moves more obviously into the spotlight. Larry, whose proposal

of marriage Astra has accepted, nearly comes unglued when she starts

talking about having a family right away. At the other end of the book,

Maureen offers the solution to the "dilemma": she loves Concrete

and he loves her, but he's without sexual apparatus and therefore incapable

of the loving recreation she has in mind, so she strips and caresses

herself while letting him watch. Potentially, it's a bad taste locker-room

joke of grossly raucous proportions-or an utter embarrassment-but Paul

Chadwick manages the entire sequence with great delicacy, humor,

and emotion. Surprised the next morning by a visit from Walter Sageman,

the population control guru, Maureen leaps up and runs into the bathroom.

In the book's last panel, she's wearing the shower curtain, a delicious

visual gag that finishes the issue off with a sly smile. Gun

Fu has been a visual firecracker from the first issue of the 4-issue

series, and the last issue maintains the pace. Joey Mason (pencils) and Howard

Shum (inks) manage the most severe manga style around, producing

highly abstracted visions of human anatomy and physiognomy, but they

also do some nifty storytelling, including mood sequences of considerable

effectiveness. The end of "The Lost City" series is bloody-and

sad, affecting. The 4-issue ride has been a joyful scamper. No. 4 concludes

with Shum interviewing photographer Glen Luchford followed by Shum's

own photographs of some Victoria's Secret models, accompanied by manga

pin-ups by Shum and Mason. Now this manga style I like. Bold lines and

square fingers distinguish it from the simpering style that turns me

off (in case you're keeping score). More of that style of manga-influenced

art undertakes a much more serious subject in The Wicked West, an 82-page graphic novel

about vampires and gunslingers in the old West and in the 1930s. Neil Vokes gives visual life to the tale

by Todd Livingston and Robert Tinnell, drenching most sequences

in deep black shadow against which his filagree line is attractively

contrasted. Vokes' lines aren't bold, but they're not wispy either,

and liberal use of solid black gives the enterprise a more sinewy appearance.

So I like it. Vokes is good with mood but not so good with action. In

the opening sequence, he jams too much activity into one panel as he

depicts his protagonist kicking a table, drawing his guns, and shooting

at the bad guys. All this action in a single panel robs the incident

of visual drama. But it winds up with a great tagline: after the gunslinger

kills his would-be assassins, he looks into the wallet of one of them

and concludes that it isn't his lucky day after all-"They didn't

pay you in advance," he says. I'm not a big fan of vampire tales,

but this one adopts a storytelling device that elevates the narrative

above mere spookiness. In 1932 a grandfather and his grandson go to

a movie about an old time sheriff, a schoolmarm and a vampire. The movie's

story is rendered in pencil, splashed with gray tones and light blue;

the other story is inked and colored. The book's narrative flashes back

and forth from the 1932 movie to the old West in 1870, where the gunfighter

of the opening sequence becomes the school teacher in the town and must

kill a few of the local vampires, led by one of his students, a girl

who tries to seduce him. The two narratives run parallel, ending separately

with their protagonists driving stakes through the hearts of the undead.

The interplay between the two stories makes for both contrast and emphasis,

one narrative culminating in a moment that sets the emotional stage

for the resumption of the other narrative on the next page. And on the

last page, we find out who the grandfather is, an identity that binds

the two tales together as a fable of the rites of passage from youth

to manhood. In Wyatt Earp: Dodge City No. 1, we get some nice black-and-white (with

gray tone accents) illustration in shadowy chiaroscuro from Enrique Villagran. His crisp, bold lines

handle the action and staging with aplomb, and he can draw horses with

panache, a vital but often neglected talent with artists attempting

to draw the American West in the 19th Century. He gets the

right ambiance with his pictures of characters and of interior scenes

although some of his exterior sequences take place in front of buildings

that look entirely too brand spanking new for the sun-baked old West,

but he is a superb artist and shows, page after page, that he can draw

anything with convincing confidence. The story has the famed shootist

Wyatt Earp coming into Dodge City to assume the marshal's job (nice

treatment of a rainy opening sequence); Doc Holliday also shows up.

Writer Chuck Dixon's characterization

of Holliday is about right: the man was all gambler and psychopath.

Earp, however, is given a lawman's nobility that the actual gunslinger

never had. The actual Earp also made a living as a gambler: he acquired

a badge in whatever town he was in purely as a way to facilitate profits

at the gaming table. He has emerged in Western lore as a heroic figure,

but most of that heroism is the result of Earp's own diligent burnishing

of his autobiography. But who comes to comics for authentic history

and biography? Dixon and Villagran give us an engrossing tale, expertly

rendered; and that's what we came here for. I went back for another look when Angeltown No. 4 (of 5 issues) arrived. Shawn Martinbrough's storytelling and

visual technique are still the most impressive thing about the series:

crisp and as almost as heavily shadowed as Eduardo Risso's work in 100

Bullets, the pictures move the story forward with emphasis and eye appeal.

But Gary Phillips' story is as tangled a web

as any of Raymond Chandler's, and plunging into the fourth issue without

seeing the second and the third is a thoroughly disorienting experience.

And I doubt that had I visited the second and third issues I'd be any

the wiser. The tangle is simply too thick. This is a story whose individual

chapters could profit enormously from plot summaries at the beginning

of each installment. But it's still fun to look at. Comic Strip Watch In

the last week or so, Bill Griffith's

Zippy has come close to revealing the secret

of the strip's peculiar sense of humor-the seemingly meaningless juxtaposition

that animates the strip occurs when Zippy, who "lives" in

the audio-visual world of tv commercials, attempts to apply the principles

of that life to the life he encounters in the real world. I was hoping

to quote something here by way of demonstration, but I discovered that,

suddenly-overnight-the Houston

Chronicle's online comics page won't print out strips anymore, and

without the actual strip in front of me, I can't quote it. You can find

it, though, by going to the King Features website (www.kingfeatures.com)

and look for strips that ran the week of, say, January 31. Cathy's wedding was achieved in the

same kind of outlandish spirit that has prevailed in the strip all along,

a signal accomplishment, I thought. Cathy and Irving said their vows

on Saturday, February 5, but the ceremony began on Monday, January 31,

with typical Cathy comedy: the bridesmaids debate the

order in which they'll go down the aisle, and at first, they all want

to go last; then, when it is explained that the order is dictated by

the "sacred wedding tradition" of "best friend"

going first, "best rear" going last, none of them wants to

go last. Cartooner Cathy Guisewite also raised $18,000 for

the pet sanctuary where she volunteers by getting Cathy and Irving's

well-wishers to make donations through an online "registry"

for Electra and Vivian, the couple's pampered pet dogs. Ted

Rall's at it again. Apparently not in the news with scandal and

sensation enough lately, he's dug up Pat Tillman again. In the original

outrage of last April, Rall offended vast regions of the land by suggesting

that the football player turned Army ranger was not exactly the selfless

American patriot he was made out to be: according to Rall, Tillman satisfied

his aggressive nature as much as his patriotic impulse by giving up

the gridiron brawl for the desert fire fights in Iraq and Afghanistan.

So he was scarcely a hero; he was, actually, a dupe of the Bush League's

propaganda. Since then, we discovered that Tillman was killed by friendly

fire, the result of battlefield stupidity as much as individual derring-do.

On February 3, Rall stages an interview in his strip with the ghost

of the NFL soldier. "Still dead, eh?" it begins. "Uh-huh,"

says Tillman, "and they still make me wear this uniform-'stop loss'

has gone too far." In the last panel, Rall tells Tillman that "the

media has already forgotten you," to which Tillman bristles, saying,

"No way, man. Republicans control all three major religions."

Tillman, in other words, is wholly unrepentant. Rall's cartoon here

conducts a more effective rhetoric than his first attempt on the Tillman

subject; but no outrage, no publicity, no appearances on right-wing

tv talk shows. Just Rall, saying, "I told you so." At theWashington Post's online "Chatological Humor" by Gene

Weingarten, Garry Trudeau was

asked (on or about February 2) if the character Honey, the reprobate

Duke's, er, retainer, might be based on Marcie in Peanuts.

Said Trudeau: "Honey was based on a translator I met when I

was traveling with the press corps during President Ford's trip to China.

It was clear to us that she and her colleagues were improvising in order

to put the best face on everything, so that was my departure point.

There was a kind of deadpan, opaque quality I was going for, which is

why I hid her eyes behind glasses. I was trying to come up with an earnest

foil for the impulsive, volatile Duke, who had just been appointed ambassador

to China. That being said, there is a definite similarity in tone and

appearance to Marcie, and readers have remarked on it over the years.

As an avid Peanuts reader, I'm sure her influence was buried in my brain somewhere,

but had I been intentionally channeling the character, I like to think

I would have done a much better job of disguising it!" The Chicago Tribune dropped Scott Stantis' conservative-leaning strip

Prickly City on February 7, saying the

strip attributed to Senator Ted Kenney something he did not say. The

dialogue in the strip between the little girl Carmen and her coyote

friend starts with Carmen saying, "Did you hear what Ted Kennedy

said during the Condoleeezza Rice confirmation? 'They lied and people

died.'" To this, Winslow the coyote pup says, "Wow! Ted Kennedy

said that? Was he driving?" Winslow's allusion is to the Chappaquiddick

incident in 1969 in which a girl working on Kennedy's campaign died

when the car Kennedy was driving ran off a bridge into the water; Kennedy

escaped but the girl drowned, and Kennedy's explanation was slow in

coming and tortured when it came. The intended irony is that Kennedy

is a fine one to talk about lying and causing death. Geoff Brown, the

Trib's feature editor, said

they killed the strip because it attributed to Kennedy something he

didn't actually say. "This episode," he said, "is strictly

about the words put in Kennedy's mouth. Had the strip arrived at its

punch line without asserting that Kennedy made such a statement at the

Rice hearing, then we would have run it and laughed along with everyone

else." For his part, Stantis, in effect, agreed. In the strip he

sent to his syndicate, Universal Press, the words attributed to Kennedy

did not appear within quotation marks; UP's editors added the quotes,

thereby converting the remark to a direct quotation. Stantis knew those

weren't Kennedy's exact words; he was paraphrasing the gist of the Senator's

remarks and didn't put them in quotation marks. Prickly City, it sez here, appears in about 100 newspapers; none of

the others, as far as Stantis knows, dropped the February 7 release.

Civilization's Last Outpost Termites,

we understand, are difficult to detect until they've done their damage.

A California pest control magnet has found a way to discover them. Turns

out termites are extraordinarily flatulent. "They eat a huge amount

of roughage," said the exterminator, Terry Clark. In fact, according

to the New York Times, termites produce so much

methane gas that a 1982 report in Science

magazine estimated that 30 percent of the methane in Earth's atmosphere

comes from the insects. So Clark devised a way to discover termite flatulence

as an early-warning system, indicating they might be about to pounce

on someone's house. Ah, the march of science-what a gas. On Slate.com, staff writers tried to

find out why models walk the way they walk-you know, that vigorous stride,

swinging hips and shoulders in undulating rhythm like Jennifer Garner

in "Alias." Some models have to take lessons in walking. "It

depends on where they're from," according to Andrew Weir, a New

York casting director. "If they're from Brazil or South America,

the walk is innate. The other girls have to watch the Brazilians for

a season or two until they catch up." The walk I've just described

is the "Versace walk." Another locomotion, Weir explained,

is just "street walk"-no swish. Most shows deploy models walking

"street" with a little extra, a nearly natural stride with

no hands on hips or posing. "But the walk," says Slate, "is

still slightly exaggerated: some extra swagger makes skirts swish dramatically

and gives tailored looks a bit of extra power." Yup, that's what

I say whenever Sydney Bristow comes striding into the camera on "Alias." A Famous Unknown Cartoonist for Black

History Month All

around the tiny room in the rear flat on Edgecombe Avenue in Harlem

were stacks and stacks of drawing paper with pictures on them, tottering

stalagmites of wispy pencil sketches, muscular charcoal renderings,

and delicately hued watercolors. The linear quality in the drawings

had a nervous, searching aspect: outlines were made with several strokes

of the pencil as the artist sought exactly the right placement, then

the final delineation was made with single firm, dark stroke. Texture

and modeling were added with grease crayon or charcoal or simply repeated

strokes of a snub-nosed pencil, dashing diagonal lines back and forth

across the surface of the picture to produce gray tones from dark to

light. In the watercolor pictures, the lines were simpler, bolder-single

strokes outlining figures and features-with color added in broad daubs

and easy splashes. In the midst of the room's litter, a twenty-five-year-old

man of an even dark cinnamon complexion sat at a drawingboard propped

against the edge of a dresser. His visitor, a white man perhaps only

four or five years older than the artist, stared at the stacks of drawings,

his eyes bulging slightly as disbelief surrendered to comprehension.

He saw gag lines written below many of the pictures, and he knew, then-beyond

any hesitancy or doubt-that he had discovered a treasure trove of cartoons,

a bonanza of bonhomie as yet untapped by the publishing world. "I wanted to yell Eureka,"

the man said later, "-because I saw at a glance that my troubles

were over." What Arnold Gingrich called his "troubles"

early that fall of 1933 any other magazine editor would have dubbed

a blessing: his publisher in Chicago had just phoned him in New York

to tell him that the number of color pages in the maiden issue of their

new magazine had been increased from twenty-four to thirty-six. This

unanticipated bonus was troublesome only because Gingrich had been hustling

to fill twenty-four pages with color illustrations; with the allotment

suddenly increased by a third, his quest had turned into a desperate

scramble. They had always planned on devoting

plenty of pages in the magazine to full-page cartoons, and now, with

the windfall color pages, cartoons in color seemed the easiest solution

to Gingrich's problem. All he needed was twelve good cartoons in color.

He had journeyed to New York to secure for the magazine the work of

the cartoonist whose renditions of the curvaceous gender would be perfect,

he knew, for a men's magazine such as Esquire

planned to be. Russell Patterson was, Gingrich said, his "beau

ideal of the kind of cartoonist" they wanted: the "Patterson

Girl," a regular fixture on the covers of Sunday supplements and

humor magazines, was as well known as the Ziegfeld Girl. But Gingrich

was on a budget, and when he met Patterson in his studio and offered

him a hundred dollars each for Patterson Girl cartoons, Patterson had

laughed. Just laughed. "I don't think any well-known

illustrator would be interested in doing work for your magazine at that

rate," Patterson said. "But I know a young fellow who might

serve your purpose-if you don't draw the color line." Gingrich said he had no use for the

color line-certainly not at present, desperate as he was. "Besides,"

he added, "-what the hell, magazines weren't wired for sound, so

drawings would not carry any trace of any kind of accent." So Patterson told him about "a

fantastically talented colored kid," a graduate of the Art Institute

of Chicago, who produced reams of wonderful drawings that he was unable

to sell because, as a black man, he couldn't get past the receptionist

to show his wares to any editor in New York. He gave Gingrich an address where the

artist was living with his aunt, and Gingrich went to Harlem. "I

had to step over squads of kids on the outside stairway to get to the

room where he worked," Gingrich said. And that's how he met Elmer

Campbell, who would become rich and famous as "E. Sims Campbell,"

Esquire cartoonist par excellence. Gingrich, his ears ringing and his

breathing more and more constricted, pawed excitedly through Campbell's

stacks of cartoons. "I saw that they were all beautifully executed,"

he said, "whether as roughs or as finishes. My impulse was simply

to poke a finger in toward the point midway down of each pile and say,

'How much down to here?'" He took armloads of the cartoons away

with him, leaving his check for a hundred dollars as a "down payment"

against future publication, which, Gingrich assured the young cartoonist,

would be extensive. For the next 38 years, beginning with three cartoons

in the very first issue dated Autumn 1933, Campbell's cartoons and illustrations

appeared in Esquire with such

regularity that Gingrich believed he was in every issue. (And he almost

was.) Campbell collected pay for his own drawings and for supplying

gags that other cartoonists illustrated. Said Gingrich: "It was Campbell's

roughs and our using them to inspire other cartoonists that had the

most immediate bearing on the magazine's success. Without a doubt, it

was the full-page cartoons in color, an ingredient that we hadn't even

thought of in the first place, that catapulted the magazine's circulation

from the start." Campbell's impact did not end with

cartoons. He also contributed the image of the magazine's familiar mascot,

the pop-eyed moustachio'd old roue called Esky. Arnold had been trying

to come up with a satisfactory image for the purpose for weeks without

luck. He noticed several sketches of an impish little man among the

drawings stacked in Campbell's room and, with the artist's permission,

added the pictures to the stack of cartoons he carted off. A short time

later, sculptor Sam Berman in New York transformed the Campbell character

into a three-dimensional ceramic figurine, which was henceforth photographed

for cover appearances with every issue of the magazine. Born in 1908 in St. Louis, Campbell

had displayed artistic talent at an early age and resolved on a career

in commercial art despite occasional admonitions from his elders that

any "Negro" with such ambitions would be wasting his time

pursuing them. He learned the fundamentals of art from his mother, a

painter, and the value of education from his father, a high school principal.

While a teenager, he left St. Louis for Chicago, eventually enrolling

in the University of Chicago as well as the Art Institute. Later, in

New York, he attended the Art Students League. He had freelanced in

both cities but didn't sell much until Arnold discovered him for Esquire.

Shortly after his debut in the magazine, Campbell was getting commissions

from around the world. But it was in Esquire

that he achieved the apotheosis of his art. George Douglas, writing about Esquire in his history, The Smart Magazines, said: "The Esquire connection meant the most to him,

no doubt, because in essence he, as much as anyone else, established

the magazine's visual style. His work was highly finished and polished,

of course, and he could render a wide variety of curvaceous females-chorus

girls, innocents, vamps, supercharged office secretaries-in moods ranging

from the voluptuous to the risible. His touch, in any case, fit Esquire to perfection. It was slick, jaunty, tongue-in-cheek, stylishly

erotic, playfully adult. So apt was the material that it was used eventually

in all manner of drawings, not only cartoons-fashion drawings, covers,

illustrations for stories and articles, fillers of all sorts." Living up to his burgeoning income,

Campbell moved into the Dunbar Apartments on Seventh Avenue, the most

glamorous apartment building that African-Americans had in New York.

And there, the cartoonist met Cab Calloway, jazz musician, band leader,

and the instigator of Minnie the Moocher, whose scat "hi-de-hi-de-hi-de-ho"

enlivened the evenings at the Cotton Club whenever Duke Ellington had

gigs out-of-town. The jazz man and the cartoonist became fast friends

and frequent habitues of Harlem nights. Calloway loved Harlem. "Harlem

in the 1930s was the hottest place in the country," he wrote in

his autobiography, Minnie the

Moocher and Me. "All the music and dancing you could want.

And all the high-life people were there. It was the place for a Negro to be. ... No

matter how poor, you could walk down Seventh Avenue or across 125th

Street on a Sunday afternoon after church and check out the women in

their fine clothes and the young dudes all decked out in their spats

and gloves and tweeds and Homburgs. People knew how to dress, the streets

were clean and tree-lined, and there were so few cars that they were

no problem. Trolleys ran down Lenox Avenue to Central Park. People would

go for picnics on a Sunday afternoon, and the young couples would head

for the private places between the rocks to spoon and make eyes at each

other. I'm not being romantic. Harlem was like that-a warm, clean, lovely

place where thousands of black folks, poor and rich, lived together

and enjoyed the life." Harlem was also the destination for

much of New York's night club population, white as well as black. And

Calloway and Campbell joined in. "By the time I met him,"

Calloway said, "Campbell was a well-established cartoonist. He

was also, like me, a hard worker, a hard drinker, and a high liver.

I used to think that I worked hard. Cotton Club shows six or seven nights

a week, matinees at the theaters a couple of afternoons, theater gigs

sometimes in between the Cotton Club shows, and benefits on the weekends.

But Campbell outdid me. He drew a carton a day, not little line drawings,

but full watercolor cartoons. And he played as hard as he worked. He

loved to drink. When we got to know each other, we would go out at night

to the Harlem after-hours joints like the Rhythm Club and just drink

and talk and laugh and raise hell until the sun came up. Somebody would

get us home and pour us into bed, and we'd be back at it again the next

night. "One of my favorite cartoons by

Sims," Calloway continued, "shows a boys' choir in a big church.

All the choirboys are white except for one big-eyed Negro. The choir

master is getting ready for the Sunday service, and he's looking at

this Negro kid with a reprimand in his eyes. The caption reads: 'And

none of that hi-de-ho stuff.' Elmer did that cartoon in 1934, and it

was published in Esquire in October of that year. He and I were tight friends by then.

Jesus, I loved that man. He was one of the straightest, most natural

men I'd ever met. Unaffected, you know, just honest and open; loud and

noisy when he got drunk, and ornery as hell when anybody disturbed him

while he was working. ... Over the years, we stayed close to each other.

Many a night, he and I would hang out together screwing around, drinking

bad gin straight in after-hours joints. I would complain to him about

my wife, and he would complain to me about his. We were personal with

each other, and we could holler at each other about our problems while

we laughed at them. ... We joked and laughed and shared things, man

to man. There are few men I've had that kind of friendship with." In 1936, Campbell moved to fashionable

Westchester County where he built a flagstone mansion on a large piece

of land, about which Gingrich exclaimed: "It was many years before

it was anything but earthshaking to have a home of that kind [in that

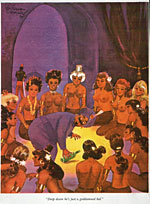

neighborhood] occupied by a Negro." While Campbell drew cartoons about

life among the fun-loving classes and wrote articles about the nightlife

in Harlem, he was celebrated for drawing pretty girls, and he gained

renown for the harem cartoons he rendered in lovingly luminous flesh

tones. The girls in Campbell's cartoons looked white, but according

to the cartoonist, "If they came to life, they'd be colored. Colored

girls have better breasts and more sun and warmth," he is reported

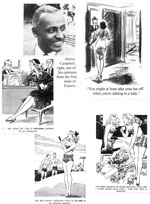

to have said; "I like a fine backside, and they have it!" In 1942, Campbell's leggy ladies began

appearing in pen-and-ink black and white in a daily newspaper cartoon

called Cuties from King Features Syndicate. The color bar began to be lifted somewhat

in the 1950s, but Campbell had, perhaps, had enough, and by then, he

was able to do something about it. In 1957, he left his baronial mansion

in White Plains and moved to Switzerland, where he lived until 1971,

mailing his work to stateside clients. In the early 1960s or thereabouts

as Esquire underwent format changes, Campbell's

harem girl cartoons appeared in Playboy

as well as their birthplace. He returned to the U.S. in the fall of

1971 and soon thereafter learned that he had cancer. He died in January

1972. Calloway was heartbroken. "I have lost many relatives and

friends in my years," Calloway wrote, "but other than the

death of my mother, none has struck me as Elmer Campbell's did. It was

because the man was so full of life that his death hit me so hard."

At the funeral home, Calloway was overcome. "I was angry that he'd

left me," he said. "The feeling came upon me so suddenly that

I had no control of myself. This goddamn man who I had known for so

long and spent so many drunken and sober, joyful and serious hours with

had left me." He began beating his fists on the coffin and hollering.

His wife and friends pulled him away. Said Calloway: "I've known

and worked with people like Duke Ellington, Pearl Bailey, Lena Horne,

Dizzy Gillespie, Jonah Jones, and Bill Robinson-to name just a few-but

if you want to know the name of a guy I loved, remember E. Simms Campbell.

My friend." Campbell was, as far as I'm able to

determine, the first African-American cartoonist to make it big in the

world outside the black community. Although his race was a secret for

much of his career, his mark on the history of American cartooning is

indelible. ************** Footnotes: Gingrich believed that Campbell had a cartoon or illustration

in every issue of the magazine until the cartoonist died. He had discovered

this phenomenon when assembling a collection of cartoons for Esquire's 25th anniversary.

For the entire quarter century, Gingrich wrote, "the common denominator

was that not one issue had ever gone to press without a cartoon by Campbell."

Thereafter, "it became a point of pride with the editors and the

makeup people to see to it that nothing should be allowed to let him

spoil that perfect record; and although there were times when it was

necessary to dig up a rough sketch out of the files and run it in its

really unfinished state, for failure to receive a fully rendered drawing

on time to make a given issue's press date, none had, until some months

after his death, ever actually gone to press without a Campbell cartoon."

However fondly and passionately Gingrich believed this, I, alas, have

at least three issues of Esquire (January and September 1946, January

1947) without Campbell cartoons. But the myth is, notwithstanding, a

measure of the esteem in which Campbell is held. Cuties

has been collected in at least four paperbacks: Cuties In Arms (1942), More

Cuties in Arms (1943)-both with the World War II military market

in mind; and Cuties (1945)

and Chorus of Cuties (1952), from which the

pen-and-ink cartoons near here are poached. Campbell also illustrated

a children's book, Popo and Fifina

(1932) by Langston Hughes and Arna Bontemps, and a collection of

Haitian poetry, We Who Die & Other Poems, by Binga

Dismond. Gingrich tells his story in Nothing

but People, an autobiography. For more about African-American cartoonists,

visit Tim Jackson's site, www.clstoons.com,

the single most comprehensive source of information on the subject. Under the Spreading Punditry Remember

the election of 1967 in South Vietnam? U.S. officials were "heartened,"

the New York Times said, "at

the size of turnout in [the] presidential election despite a Vietcong

terrorist campaign to disrupt the voting." According to reports,

83 percent of the 5.85 million registered voters cast their ballots.

"The size of the popular vote and the inability of the Vietcong

to destroy the election machinery were the two salient facts in a preliminary

assessment of the national election." We hope this is no harbinger

of things to come in Iraq, where we are encountering so many other similarities

to Vietnam. The recent election in Iraq was a genuine triumph of the

spirit of citizenry, and I can easily imagine that civic pride will

become the engine by which the insurgents are defeated. So let's hope. The Bush League budget for the coming

fiscal year boosts spending in warfare categories and cuts in many domestic

programs, including Environmental Protection Agency funds (6 percent,

the biggest hunk from the clean-air fund) and a program to help people

pay their heating bills (8 percent). But "financing for the apprehension

of Army deserters would double." I guess they expect a lot of activity

in that area. GeeDubya reportedly doesn't understand

why people 55 and older are objecting so strenuously to his Social Security

proposals: after all, they won't be affected at all, he says. His obtuseness

highlights the difference between George W. ("Wooden-hearted")

Bush and most of humanity. People over 55, particularly those over 65

or so who are already drawing Social Security benefits, know, for an

absolute fact, the tremendous value of the existing Social Security

system. And they want to make sure their children and grandchildren

will enjoy the same sort of relatively carefree twilight years. GeeDubya,

apparently, could care less about people not of his generation and therefore

doesn't understand anyone who does. Sad. To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |