|

|||||||

|

Opus 152:

Opus 152 ( NOUS R The Katzenjammer Kids had an anniversary on December 12: it reached the ripe

old age of 107, the oldest comic strip still in circulation. Created

by Rudolph Dirks in 1897, the Sunday-only

strip is continued today by Hy

Eisman, who also produces the Sunday Popeye,

another long-running strip that is celebrating its 75th year

these days, most notably, last week on December 17 when Fox-tv aired

the CGI animated cartoon in which the one-eyed sailor goes searching

for his father, Poopdeck Pappy. ... Stan

Lynde, creator of Rick O'Shay and, later, Latigo and the panel of homespun western

humor, Grass Roots-not to

mention five western novels-designed the uniform patch recently adopted

by Montana's federal marshals; the patch depicts a lone rider setting

out at dawn to hunt down the bad guys. ... Garry

Trudeau, creator of Doonesbury,

made the 90th slot on USAToday.com columnist Whitney Matheson's

list of the top 100 pop culture figures of 2004. Matheson cited the

episode in which B.D. lost his leg while fighting in In October, U.S. Customs seized copies of Top Shelf Productions'

Stripburger Nos. 4-5 and 37,

charging that the stories "Moj Stub" by Bojan Redzic and "Richie Bush" by Peter Kuper constituted "clearly piratical copies" of registered

and recorded copyrights. "Moj Stub" ("My Pole")

is an 8-page ecological parable in which some Peanuts characters appear briefly; "Richie Bush" is a 4-page

parody of Richie Rich that also satirizes the Bush League by superimposing

the personalities of the Cabinet on the comic book characters. The Comic

Book Legal Defense Fund has retained counsel to challenge the seizure.

Said Chris Staros, president

of both CBLDF and Top Shelf: "The comics in question are clearly

within the acceptable bounds of parody, and there is absolutely no likelihood

that consumers would confuse these works with the subject that they

are parodying." CBLDF Executive Director Charles

Brownstein agrees, adding: "The charge that these are piratical

copies of existing copyrights is not only wrong-headed but the seizure

amounts to an unlawful prior restraint of protected speech." If you've ever wondered why Tintin, the perpetual boy journalist invented by Belgian cartoonist

Herge, has never, in 23 published

adventures since his inception in 1929, grown up, you are not alone.

A light-hearted article in the holiday edition of the Canadian Medical Association Journal explains it all in reporting

theoretical research by Antoine Cyr, age 6, his brother Louis-Olivier,

age 7, and their father, Claude Cyr, an associate professor of pediatric

medicine at the Stephan Pastis,

who has made himself an obnoxious character in his own strip Pearls before Swine, arrived, on Tuesday,

December 14, in Mark Tatulli's

strip, Heart of the City,

as the new music teacher. I'm not sure all this inter-strip chumminess

between cartooners is an advance in the art of comic strippery, but

let's see just how obnoxious Tatullli will make him. ... After a long

absence such as befits the senior partner in the strip's title, Steve

Roper made a surprise return to the strip, and he's spent most of

the month of December so far talking about his retirement plans with

Mike Nomad; as I mentioned a couple weeks ago, they'll both be retired

on December 29. ... In Darrin Bell's Candorville, the power went off in Lamont's apartment for several

days, which Bell spent plunging the strip's panels into solid black,

the only artwork being speech balloons and lettering; the next week

in Rudy Park, which Bell also draws, the power

went off, and Rudy and his friends in the cyber café were plunged into

solid black, the only artwork being speech balloons, lettering, and

eyeballs. That's two consecutive weeks' vacation for Politics Infest Strips.

Not news, by any means, except at Get Fuzzy, whose creator, Darby

Conley, once professed dislike for comic strips taking sides on

political or social issues. On December 12, Rob Wilco, Bucky Katt's

hapless owner, tells the feline, who is writing his autobiography, "Just

because you keep saying something doesn't make it true." The ever

irritable cat replies: "Yeah, but it makes stupid people think

it's true, stupid," adding, after a moment, "By the way, Mike Baldwin,

who, since 1996, has been producing a panel cartoon called Cornered, says "no tree has to die in vain" for the first

compilation of his cartoon, Cornered:

Don't Try Anything. Collecting more than 300 of his cartoons and

including a washingtonpost.com Q&A with The current issue of The

Comics Journal, No. 264, reprints 32 consecutive Little Joe comic strips, the Sunday-only creation of, it seems, Harold Gray, he of Little Orphan Annie fame. Initially written and drawn by Ed Leffingwell,

a background assistant to Gray, the strip started Cathy Guisewite,

creator of the perpetual Cathy,

whose eponymous heroine has been obsessing about her forthcoming

wedding (scheduled for February 5, 2005) for over ten months now, realizes

that her altar-bound couple, like many somewhat "older" people

verging toward nuptials, probably have everything they need in order

to set up (or continue) housekeeping. So Guisewite has registered Cathy

and Irving at http://www.thebigday.com/cathy

where visitors can choose from a number of items destined to benefit

a not-for-profit rescue organization for dogs and cats-such items as

"Happily Ever After Flea and Tick Baths," "Here Comes

the Dinner Bowl Meals," and "In Sickness and In Health Veterinary

Checkups." At the end of the three-month campaign (December 1 -

February 28), the money for the gifts will be presented to the Pet Orphans

of Southern California. Guisewite, who volunteers (with her daughter)

at Pet Orphans, got the ball rolling with a $1,000 donation. All those

who donate will receive a Thank You from the happy couple, including

an autographed copy of their wedding photo. We are often concerned about the absence of freedom of the

press in other, allegedly more backward, countries. But the tendancy

lurks here, too. In But I don't mean to suggest that the so-called free press

in this country is without fault. In fact, I agree with Wiley Miller who expressed his exasperation with If you're curious about conservative attitudes and can't

get enough by reading Mallard

Fillmore or the much less prickly Prickly

City, check into www.rightoons.com,

a website dubbed "Right Toons" (with a punning road-sign logo

depicting a right turn arrow), where Colin

Hayes publishes a satirical political strip called The

Leftersons (clever name) plus editorial cartoons by Bob Lang and Paul Nowak,

an outgrowth of the conviction that there aren't, apparently, enough

conservative comic strips and political cartoonists. In an informal

survey in 2002, Editor & Publisher

found that syndicates claim 19 "liberal" political cartoonists

among their combined rosters of syndicated editoonists while only 6

were "conservative." Recently on the e-mail list sponsored

by the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, participants listed

by name 46 editorial cartoonists who were, by their own admission, "conservative."

Not all of that number are full-time editoonists, though; my estimate

is that only about 25 of them are. But if there are only about 90-100

full-time editoonists in the country, that means fully a quarter of

them are of the conservative persuasion. The percentage, in other words,

is about the same as E&P's

informal survey. Incidentally, just to anticipate the coming windstorm, in

The Boondocks during the week

immediately ahead, McGruder takes on Santa, introduced on Saturday,

December 18, as "a fat, old, self-hating Black man named Uncle

Ruckus,l" who, spying the little girl's Afro, says, "Girl,

your hair is nappier than a wolf's butt in a windstorm! I know somebody

who's gettin' some relaxer in her stocking!" Several newspapers

have already said they'll skip the current releases and re-run last

year's. Every so often-oftener than we'd like to think about it-we

encounter yet another news report detailing the pedagogical aspirations

of a school teacher or school system that has adopted comic books as

a sure-fire way of engaging "reluctant readers" in the academic

enterprise. Here's another one about a pilot program in "some parts

of And here is the cover illustration from the most recent

issue of The Cartoonist, bi-monthly

newsletter of the National Cartoonists Society: celebrating the 50th

anniversary of Hi and Lois,

a water-colored pencil drawing by Chance

Browne, who pencils the strip. This specimen vividly shows how his

pencil work looks before it is inked by Frank

Johnson. Under the Spreading Punditry Social Security, the blather

of the Bush League notwithstanding, doesn't need radical reformation.

According to most experts who are not politicians, the Social Security

funds are adequate until roughly 2040, and only a little tinkering (a

fraction of a percentage point of adjustment here or there in either

collection or disbursement) could get us well beyond the time that the

Boomer Generation is supposed to overwhelm the system. Or, let's say,

just remove the ceiling that establishes an upper limit on the amount

of earnings per year that are taxed by Social Security. The Bush League

wants to privatize the system, according to Paul Krugman in the

New York Times, as a purely ideological matter. This impulse, he

continues, is aided and abetted by financial corporations that would

dearly love to have more money to invest and otherwise play with. I

think it's the other way around, but the point is: the Social Security

system is not in need of drastic overhaul. Krugman has also surveyed

other countries that have privatized their social security systems to

see how it's working. It isn't. Privatization, he says, "dissipates

a large fraction of workers' contributions into management fees for

investment companies" and leaves many retirees in poverty. Management

fees can be reduced if the government does the investing; but if that's

the plan, then we're being lied to when GeeDubya says we'll get to manage

our own investments. In some countries where social security systems

have been privatized, the costs have gone up: when the private investments

don't pay off, the government must step in and fund the retirement of

persons who would otherwise be plunged into dire poverty. The Los Angeles Times

reports that the Army National Guard has fallen 30 percent short

of its recruiting goal in recent months. ... Nearly 900 children in

the Politicians are expert at dodging the issue and diverting

the argument. Discussing Rumsfeld's gaff and the failure of the Bush

League to adequately armor soldiers sent to Iraq, one esteemed member

of Congress, appearing on Capital Gang, deftly changed the subject:

"Surely," he said (or words to this effect), "you aren't

saying that President Bush and Donald Rumsfeld deliberately sent our

troops over there so unprotected as to court death and disaster?"

No, surely: none of us suggest that. But that changed the subject. Instead

of focusing on the ineptitude of the Bush Leaguers as war planners,

the topic was, suddenly, whether or not leading members of the administration

were, in effect, war criminals. No, of course they aren't war criminals:

they're simply inept and stubborn about it, but shifting the ground

of the discussion took our attention off the real subject-the incompetence

of the administration-and directed it to a phoney subject-the demonic

culpability of the Bush Leaguers. And since no one believes the latter,

the assault on the Bush League was skillfully shut down with everyone

seemingly agreeing that, no, no one in the Bush League was culpable

(even though the culpability being denied herewith was not the culpability

they were initially being accused of). The recent Rumsfeld flap in the press over armoring the

troops in Once a Month is Not Enough Just as I predicted, the Comics Buyer's Guide has gone Last Kiss Sells Comics One Panel at a Time John Lustig, who's a friend

of ours, has been producing a two-panel comic strip at the Comics Buyer's Guide for several years now. Called Last Kiss, it employs artwork from vintage

Charlton Comics, the rights for which Lustig acquired before launching

the series. For the conventional and, even, hackneyed scenes of budding

and/or frustrated romance depicted in By now, we all know the key to success. Graphic novels!

Trade paperbacks! Thick collections of cool comics disguised as respectable

books for the Barnes & Noble crowd! Right? So why is Last Kiss creator

John Lustig doing the exact opposite? "Instead of selling my work in massive books, I'm marketing

them one panel Lustig's "one panel at a time" sales come in the

form of a colorful line of Last

Kiss note cards and magnets. Featuring revised panels from Lustig's

outrageous CBG comic strip and Last Kiss comic books, they began reaching stores late this summer.

"We could have started out slow with a couple of dozen

images," said Lustig. "But I've been test marketing the images

for years-mostly selling them as hand-cut magnets at conventions, both

to comic fans and the general public. And they've always done extremely

well. People apparently like my sense of humor. So my wife and I decided

to gamble and we jumped into mass production with a full line of 48

magnets and 48 note cards." Lustig has regional sales reps for the "Frankly, our primary focus is selling to book, gift

and greeting card shops. It's a much bigger market than just the comics

community," said Lustig. "However, I'm inordinately tickled

by every sale we make to comic shops! I'm still a comics geek at heart!

And I know the comics community far better than my reps. So my wife

(Shelagh) and I are dealing directly with comics retailers rather than have

our reps do it. In the near future, we¹re going to put together boxed

sets of the cards and possibly the magnets. At that point, we'll approach

Diamond and others for distribution." And what about a book collection? "My agents are talking

to several mainstream publishers right now and things look very good,"

said Lustig. "Oddly enough, I think my note cards and magnets are

helping sell the publishers on Last

Kiss. The way I've developed the line is showing them that Last Kiss really does have mass appeal." Footnote from the Happy Harv: In this age of rampant creators'

rights, Lustig is more scrupulous about the artwork he's using than

he needs to be. Legally, his purchase of the rights to the Charlton

material gives him the right to use the artwork without paying anyone,

but "on several occasions," Lustig says, "I've paid modest

honorariums to creators-when I've made a substantial use of their work

and I know how to reach them." He has made no payments, though,

for the strips in CBG: "I'm just using a panel or two

of art and trying to keep track of all these bits and pieces would be

difficult. It would also be financially infeasible: CBG pays very little. (I'm not complaining so much as recognizing

a fact.)" Sometimes, Lustig commissions new artwork for the comic

book, and when he does, he pays the artists a fee. For the cards and

magnets, on the other hand, he's again using only individual panels

and no new artwork; what with the financial risk he's taking and the

minuscule portions of art, he's not, with an exception or two, compensating

the artists. A Final Note from Nicole Jantze about the Norm.com Michael Jantze's dutiful and devoted wife writes to tell us

of the state of Norm's drive for a new lease on life online: ] The final three weeks of my

drive to raise money for The Norm.com are here. It's My goal is 4,000 donations. We're not there yet, but we

are more than half I'm not asking for your donation if The Norm isn't your favorite comic strip. This isn't a charity. Don't

donate for any reason other than that you or a family member or friend

LOVE Michael's work (great gift idea, hint, hint). What do you get if

you join? A year-long membership to The Norm.com and new The Norm strips. Plus whatever else Michael is cooking up (yes, he's

thinking about "beta-testing" another strip on the site) all

for $25 a year. Of course, there's more benefits if you donate at a

higher level. Go to http://www.thenorm.com/subscribe/

for more details. We accept payments through Amazon Honor System, PayPal

payments as well as VISA, MasterCard and Amex through The Norm Store

(a secure Yahoo! Store). Thanks for your time. Have a great holiday

season and 2005. See you at The Norm.com! -Nicole Jantze Yes, there's still time to sign up. Go

there and do it. Funnybook Fan Fare Trigger No. 1 from Vertigo introduces us to a post-modern Orwellian

world run by a giant corporation called Ethicorp, whose profit-motive

and slogan, "We get the bad out,"qualifies it as a futuristic

glimpse of the world the Bush League is building for us while we are

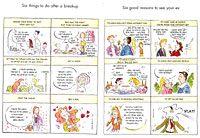

distracted by the war in Ahhhh, Maitena! Every once in a while, something

comes along that is so bright and shining that it lights up your life.

In matters cartooning, I get lit up when I chance upon some new variation

on the ways words and pictures can be deployed in tandem to achieve

a comedy that transcends the words by themselves or pictures alone.

And when that new blend of the verbal and the visual embodies a novel

point of view or a fresh voice, the light vaults to incandescence, and

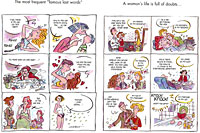

I am warmed as well as illuminated. The first page I looked at in Maitena's

Women on the Edge 1 brought

on a moment like the Millennium Falcon's first leap into warp speed

when the snap of light on the screen instantly catapulted sight into

feeling. The book (80 6x9-inch pages in paperback; Riverhead Books,

$12) reprints over 70 of the weekly comic strips by Maitena Burundarena,

a forty-ish Argentinean woman, who, since 1993, has been articulating

with wit and compassion the hopes and fears and frustrations of women

throughout Latin America. "Women are not all the same, but the

same things happen to us," says Maitena, who uses only her first

name professionally. "I talk about solitude, separation, falling

in love, anguish, failure, success, children-universal themes that everyone

experiences." Although she speaks most directly to women, Maitena's work has a much more universal appeal than her

Latin American success would suggest; the two book compilations so far

published (Women on the Edge 2

being the second; a third is on the way) have sold over a million

copies world-wide. Her drawings are simply but expertly rendered (no

fumbling inadequacies at anatomy, for example) and delicately colored

in pastels. Each page in the books prints one strip, typically 4 or

6 panels long, each panel a visual-verbal vignette that represents a

different aspect of the topic announced in the heading for that strip.

Under "Life Is Not Fair," for instance, the drawings depict

a good wife, terrific mom, born homemaker, respected working professional

in charge of her own life, who, in the last panel, assumes an anguished

expression and asks: "So why do I have to have cellulite?"

The pictorial progression, as in "Women Are So Beautiful ... !

which I've reprinted in this vicinity, is often ironic: here, the pictures

offer ironic contrast to the individual panel captions, concluding with

the resounding irony in the depiction of "being a woman is so easy."

Maitena's books and strips have recently attracted an international

following (which is certain to include the U.S. now that the books are

available here in English), but she is not eager to become the creative

engine that aggressive pursuit of newly opening opportunities would

entail. "They've offered me film scripts to write and animated

films to draw, but I'm not going to change my life for that," she

says. "Who says the better you're doing, the more you have to work?"

Right: I said she was a fresh breeze blowing. She had her husband, Daniel

Kon, formerly manager of Latin American rock groups, divide their time

between Argentina and Uruguay, where they have a seaside cottage. "Relations

[there]," says Maitena, "are based on one's personality and

not on fame. There's a bit of fleeing from the world in living there,"

she admits, "but it's because we're found a life that appeals to

us. It's a fishing village. I have my own garden. I can cook for myself.

I make ceviche and sashimi. I walk on the beach for an hour every day

and play with my daughter"-Antonia, who is four. Current Crop of Comic Strip Reprints: Part 3 of 3 Another of the commemorative

tomes before us is 27 Years of

Jeff MacNelly's Shoe: World Ends at Ten, Details at Eleven (210

8.5x11-inch paperback pages, black-and-white with color Sundays; $16.95),

edited by Chris Cassatt, MacNelly's long-time assistant on the strip,

and Susie MacNelly, the creator's widow. Why a 27-year anniversary?

Got me. But it's nice to have, whatever its motive. The editors have

adopted the popular scrapbook approach in assembling and presenting

the contents: in addition to short sequences from the stri MacNelly died of lymphoma in June 2000, a three-time winner

of the Pulitzer, and his brethren in the editorial cartooning fraternity

marked his passing with anecdotes that illuminated his personality rather

than his professional achievement. Not that they didn't admire him professionally.

At an editorial cartoonists convention years ago, MacNelly doodled on

a napkin while a particularly boring speaker droned on; when the speaker

finished, MacNelly got up to leave, and a horde of his colleagues rushed

up to grab the napkin he'd left behind. MacNelly was thoroughly unpretentious,

"happier," columnist Dave

Barry said, "drinking a beer with his plumber than having dinner

at the White House." Jim

Morin of the Miami Herald

wrote: "This man of such awesome talent never bragged, never

surrounded himself with a circle of sycophants, never acted as if he

were 'above' his audience or his fellow cartoonists." As an editorial

cartoonist, MacNelly was generally seen as conservative, but he was

more a spectator, more bemused by the passing show than outraged. He

was a clear-eyed observer of the human condition-particularly the condition

displayed by politicians. Some of us think of politicians as craven

power brokers with self-interest as their chief motivation. But to MacNelly-judging

from his cartoons-these political leaders are merely bigger buffoons

than most of us and therefore a greater inspiration to laughter. His

cartoons suggested that our proper response to these four-star bumblers

should be the chastisement that laughter inflicts rather than the ouster

than the ballot box can effect. After all, you can't defrock a naked

emperor, and MacNelly showed them naked often enough to make us familiar

with the anatomy of politics. But the comic strip was another story. MacNelly needed more

to do: an editorial cartoon every day scarcely drained him of hilarious

ideas that needed to be disseminated as widely as possible. A daily

comic strip would give him a spotlight that he could shine on every

human foible, not just the political horseplay. Besides, he'd always

wanted to do a comic strip. Why couldn't he do a daily strip as well

a daily editoon? "I was daring myself, really," he said. In

the conception stages, the strip was about humans, but MacNelly found

them "boring"; so he turned to animals, finally settling on

birds. He liked the idea of doing goofy drawings of them flying around

(and in the early years, they flew more than they have recently). "A

bird smoking a cigar is an interesting sort of bird," he said.

"You really want to listen to him. And it's zany on its face to

have a bunch of birds walking around with clothes on." Moreover,

birds, not being human, provided the perspective of an outsider on the

human condition, a perspective MacNelly felt comfortable with. From

Shoe's perch at the Treetop Tattler-Tribune (the newspaper

he started a month or so after the strip's debut on September 12, 1977),

MacNelly could ridicule human foolishness with complete abandon, and

he did, steering into all those inlets of human endeavor that his editorial

cartoon with its political emphasis had to ignore. For his cast, MacNelly

mined his own life. The title character, P. Martin Shoemaker, or "Shoe,"

was Jim Shumaker, MacNelly's first editor, a legendary personage in

North Carolina journalism. Shu edited the Chapel

Hill Weekly, came to work in tennis shoes, and chewed his way through

cigars all day long. The Perfesser's nephew, Skylar, was MacNelly at

the age of twelve. Like Skylar, MacNelly was, by his own admission,

"a terrible athlete. I couldn't do anything that a large person

is supposed to be able to do." The Perfesser was not, at first,

MacNelly in adulthood. But before long, MacNelly found himself turning

into the Perfessor. "It's terrifying," the cartoonist said.

The entire ensemble pecks its way through the book: Loon,

the air mail expert; Roz at whose dingy diner the crew often collects;

Madame Zuzu, the fortune teller; Senator Batson D. Belfry (wondrous

name), Irving Seagull, Wiz the computer mechanic, even the Perfesser's

aged DeSoto and, at the other extreme,

Muffy Hollandaise, a preppy girl summer intern (who, we learn

in the section "Where Are They Now?" is running an escort

service in Washington, D.C.)-and Bumpkins, the butler the Perfesser

(Cosmo Fishhawk) inherited from an eccentric uncle. A fifteen-page section

rehearses many of Skylar's experiences at summer camp, a popular annual

event in Shoe wherein we all

realize what Skylar never does: that his summer camp is a Marine Corps

training redoubt with picturesque names like Parris Island and Cherry

Point. Since MacNelly's death, the strip has been continued by Cassatt,

who roughs out the panels, Gary

Brookins, who reworks the roughs and inks the final versions, and

Susie MacNelly, who passes final judgement on the gags supplied by Bill

Linden and Doug Gamble. And there are enough pages of their work to

demonstrate that Shoe is in good hands. Hysterical Feetnit: The book says the first Shoe was published on September 13, 1977,

but everything else I've seen says September 12. And the 12th

was a Monday in 1977's September, a better jumping off place than a

Tuesday. I have no convenient way to reconcile these contradictory facts,

so I'll just leave them with you. MacNelly, incidentally, is often credited

as the first political cartoonist to simultaneously produce a syndicated

daily comic strip. Not quite so. Tim

Menees at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette was the first

of the present generation: he started a strip about a would-be writer

and journalist, Wordsmith,

in 1976. But Wordsmith didn't last long. In the previous

generation of editoonists, we have Cecil Jensen at the Chicago

Daily News: he launched one of my favorite strips on October 28,

1946- Elmo, whose eponymous protagonist was a

sort of urban Li'l Abner except that Elmo was stupider than Abner. I

admire this kind of stupidity in a comic character.

And Elmo made it all seem so easy, too-smiling his bland, ear-to-ear

grin the whole time. I loved

it. Elmo spent most of his early career working in the office of a breakfast cereal manufacturer, Popnut Skrummies. Elmo actually owned the company. The previous owner, oppressed by the responsibilities of being a millionaire and owner, gave Elmo all his stock in the company. So Elmo went to work there, but he was too stupid to know that the owner of the company should be giving the orders. Instead, he took orders from the Commodore, an unscrupulous robber baron who was running the company at the time. The Commodore, seeking to get Elmo occupied with something to keep him out of his, the Commodore's, hair, hires a ecdyiast to work as Elmo's secretary. This is Sultry. And she is. Among the many things Jensen could draw was attractive wimmin.

Elmo's girlfriend from back

home, Emmaline, gets wind of all this and comes to the big city to keep

an eye on things. About this time, a cute moppet named Little Debbie

shows up and becomes the face on the cereal box, selling billions of

bushels of Popnut Skrummies. You can't keep a good sales girl down.

Before long, Elmo disappeared, and Little

Debbie was the name of the strip; it continued that way until it

ceased in 1961. Jensen's strip had a good long run, as you can see;

but it never achieved the stellar status that MacNelly's Shoe

did. MacNelly may not have been the first political cartoonist to

produce a daily comic strip concurrently with his editoons, but his

strip achieved a much larger circulation than any of its lesser known

predecessors in the genre and has lasted longer. The latest collection of Garry Trudeau's Doonesbury,

Talk to the Hand (152 9x10-inch paperback pages, French flaps; black-and-white

with color Sundays; $16.95), begins approximately August/September 2003

and ends approximately August/September 2004. You'd think with a strip

as closely attuned to current events as Doonesbury that the editors of the reprint volumes would take care

to peg the comic strip happenings to the real events they satirize,

or, at least, to provide some clue as to the initial publication dates.

You'd think. This volume starts with the carnival California campaign

of Arnold Schwarzenegger and ends with B.D. in rehab after he's lost

a leg in Iraq. Between these two benchmarks fall Duke's looting of Iraq,

Trudeau's offer of $10,000 to anyone who can prove that George W. ("aWol")

Bush fulfilled his Guard duty in Alabama (no winners, remember?), the

battlefield sequence during which B.D. lost his leg, the Sunday listing

of all the names of U.S. military personnel killed in Iraq through April

23, 2004 (for update, visit www.lunaville.org), and White

House discussions of Dick Cheney's colorful "fuck off" instruction

to Senator Leahy on the Senate floor-to mention only those events that

thrust Doonesbury into the news columns of the

nation's press time after time all year. A full year of political waggery

withal, and worth keeping Trudeau's record of it handy. "Rugrats," you may have heard, is the name of

a popular Nickelodeon animated cartoon about toddlers that started in

about 1991 and ran for 65 episodes. That was the plan. But the series

proved so popular that production resumed in 1997, and a comic strip

version was launched the next year, running for five years until 2003.

I paid no attention whatsoever to this phenomenon, thinking that I was

somehow beyond kiddie humor. But here I'm proven wrong with It's

a Jungle Gym Out There: A Rugrats Collection (128 8.5x9-inch paperback

pages, b/w; $10.95). Lee Nordling, who edited the strip all

five years, credits almost two dozen creative personnel-writers, pencilers,

inkers-who contributed to the enterprise over the years. Most strips

carry at least three bylines, and maybe it was the factory-like creative

process that turned me off without actually witnessing any of the product.

My bad. The gimmick for the tv series was that the adventures therein

were related more-or-less from a baby's point-of-view. Some of the strips

here do the same. But many of the gags have a satirical edge that's

entirely adult. Kids in swings observe that the sun was "over there

this morning" and "now it's way over there. Same thing yesterday."

In the last panel: "Wonder what'll happen tomorrie." On another

occasion, the little girl Angelica wanders through a Sunday strip, witnessing

all the male cast members in succession, burping, smearing food on themselves,

drawing on the wall, and the like; after a contemplative panel, she

says, "Sigh. I'll never find a husband." Tom the Dancing Bug

is another comic strip endeavor that I don't reach much. Launched

into the alternative journalistic environment in about 1990, Ruben Bolling self-syndicated the feature until 1997, when he signed

with Universal Press Syndicate. Tom's

forte is weighty irony, and while Bolling is deft at dissecting

the foibles and hypocrisies of the times, I can take only so much of

it at one sitting. But that, surely, is my shortcoming and not Bolling's.

In Thrilling Tom the Dancing Bug Stories (224 8.5x11-inch paperback

pages, b/w; $14.95), the cartoonist deploys all the genre in his arsenal-comic

strips, editorial-type cartoons, parodies, superhero comic books, even

diagrams-to flay his targets, the wayward fads and misguided causes

that plague us all. Here's a page, for instance, that begins with the

headline: Just As You're Morally Opposed to the Execution of Mentally

Retarded Criminals, You're Also Morally Opposed to the Slaughter of

Mentally Retarded Animals. That's Why You Only Eat SMART MEAT." Bolling's targets line up on both sides of the

political spectrum, but I suspect his conservative victims are not much

moved by his attentions: conservatives never understand irony. Steve Moore produces

a panel cartoon for newspaper sports sections called In the Bleachers in which he looks at sports in much the same way

that Gary Larson looked at

life in general (insects and cows in particular). In a tidy size (5x5-inch

paperback), 272 of Moore's manic gems about golf are available as Dibs on His Clubs ($9.95). As an indication of the content, the title

is what one of three golfers says as he watches the fourth of their

foursome being levitated into a flying saucer. A new collection of the

greeting card favorite that became the perennial polyanna of the funnies,

Ziggy, is out under the title Character Matters (128 8x8-inch paperback

pages, b/w; $10.95). Civilization's Last Outpost The anyule incitement is upon

us. In various hamlets from sea to shining sea, we are once again treated

to the spectacle of Concerned Citizens bringing legal action against

their civic authorities to eliminate all shreds of reference to the

Christian holiday from public areas, citing the dubious ground that

the State should do nothing in support of any religion. My guess is

that if all such public displays concentrated on Santa Claus, evergreen

trees, and endless strings of colorful lights, most such legal actions

would have no legs to stand on, and we'd all get suitable public festivities.

Then I suppose Christians would object to their religious event being

subsumed under rank commercialism and pagan ritual. Syndicated columnist

John Leo tackled this subject recently, and after ticking off a series

of wonderfully narrow-minded instances of objections to the season,

wound up in Florida, where, he says, "an elementary school concert

included songs about Hanukkah and Kwanzaa but offered not a single note

of Christmas music." To Leo, this suggested that the Forces of

Evil (that is, what he calls "the anti-Christmas" movement)

were picking on Christianity. Nope; sorry. Last I heard, neither Hanukkah

nor Kwanzaa are, strictly speaking, religious events; Christmas, on

the other hand, is. Elsewhere, in the same spirit, they've invented a new word

for it. Frank Costanza introduced "a Festivus for the rest of us"

in 1997 on "Seinfeld," but, not content with this, the ultimate

secularization of the seasonal celebration, the more fervent among us

have concocted a new portmanteau word that includes just about everything

one might love about the holidays in a wish for a Happy Chrismahanukwanzakah.

Meanwhile, at www.Chrismukkah.com,

Ron Gompertz who is Jewish, and his wife Michelle, daughter of a Protestant

minister, combine their holidays under Chrismukkah, "a sort of

great umbrella name for describing the chaos and whimsy and excitement

that goes on during the month of December." Chrismukkah began December

7, Pearl Harbor Day, and persists for an 18-day observance that coincides

neatly with the most desperate weeks of the traditional Yuletide shopping

season. Chrismahanukwanzakah fell on December 13, which, this year,

came on a Monday. We like the idea of celebrating chaos and whimsy and

excitement, and we admit that Happy Chrismahanukwanzakah has a nice

rhythmic sound to it, but now we don't know whether to decorate the

tree or to light nine candles or seven. Paralyzed with indecision, we'll

probably just tip an eggnog or two. With egg on our face, then, we hope

you'll continue as unabated as ever and enjoy in all directions as you

do. That's what we intend to do here at R&R online.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |

Larry

Rohter at the New York Times allowed

last winter as how "the popularity of her biting, satiric appraisal

of the sexes and their relations increasingly cuts across gender lines

as Latin American men, too, have begun to parse her comic strips for

clues to the female psyche." Rohter quotes Quino, another Argentine

cartoonist: "Spontaneous and direct, Maitena doesn't aspire to

be a mirror reflecting reality; on the contrary, she grabs hold of reality,

mirror and all, and throws it at our heads." Maitena's admirers,

Rohter notes, "regard her as a cultural phenomenon that simply

could not have existed fifteen years ago because she represents a "generational

transition" that has occurred throughout the region since then.

"Hers is a unique voice in Latin American society, looking at women's

issues with a sense of humor, humanity and frankness, and touching on

topics that are not usually talked about," said Mereles Gras, whose

magazine publishes Maitena's work in

Larry

Rohter at the New York Times allowed

last winter as how "the popularity of her biting, satiric appraisal

of the sexes and their relations increasingly cuts across gender lines

as Latin American men, too, have begun to parse her comic strips for

clues to the female psyche." Rohter quotes Quino, another Argentine

cartoonist: "Spontaneous and direct, Maitena doesn't aspire to

be a mirror reflecting reality; on the contrary, she grabs hold of reality,

mirror and all, and throws it at our heads." Maitena's admirers,

Rohter notes, "regard her as a cultural phenomenon that simply

could not have existed fifteen years ago because she represents a "generational

transition" that has occurred throughout the region since then.

"Hers is a unique voice in Latin American society, looking at women's

issues with a sense of humor, humanity and frankness, and touching on

topics that are not usually talked about," said Mereles Gras, whose

magazine publishes Maitena's work in