|

|

|

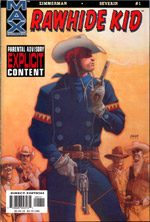

Opus 108:

Fact is, if you weren't a fairly knowledgeable person-of-the-world

sort, you wouldn't recognize the Kid's being gay. Only a reasonably

aware reader will detect in the Kid's mannerisms all of the customary

cliches associated with a faggoty life style—fancy clothing

(leather), a preference for pastel colors, a limp-wristed lingo ("Oh,

stop," are the Kid's first words, "It's a few bruises and two

bullets. You'll live.") And if you do recognize all the signs,

then the "Explicit" tag on the cover becomes insulting. What's "explicit"

(nasty) about the gay life? The label effectively perpetuates the

prejudices gays already encounter.

Moreover, if you recognize all the signs, it seems to me that

you'll also recognize the homophobic stereotype. It's cute and amusing,

but if the diversion here were racial—that is, if the object

were to reveal that the Rawhide Kid is a racial minority not a queer—this

treatment would be racist.

Stereotypes are the coin-of-the-realm in comics, admittedly.

It would be difficult to convey meaning without their use in a visual

medium. But here, the imagery is comedic, and it unhorses other, more

serious, impulses that the story lets loose.

The story itself, so far, is another instance of clumsy maneuvering.

At first, the plot is deftly painted in one of the Western's traditional

patterns: we meet Sheriff Morgan and his twelve-year-old son Toby

and his playmates, cavorting in the dusty streets of a desert town,

and then the baddies arrive, roistering noisily into the saloon, and

Morgan dutifully goes in after them to collect their guns, which,

according to a local ordinance, they must turn in to the sheriff until

they leave town. The leader of the baddies, Cisco Pike, objects to

the local ordinance and when Morgan tries to enforce it, Pike shoots

him in the arm and in the leg, and when Morgan's deputy tries to help,

Pike shoots him and kills him. Morgan's son witnesses all this excitement,

and when he runs up to help his father, whom Pike has thrown out into

the street, the Rawhide Kid shows up and prevents the baddies from

prolonging the agonies of the lawman.

Up to this point, the story unfurls with deliberate restraint:

much of both atmosphere and action are achieved by artist John Severin,

whose skill at the accouterments of the Western have never been surpassed.

Ron Zimmerman holds the verbiage in check and lets the pictures do

the narration. But then we find ourselves in Morgan's house, where

he, realizing that his son is in shock at having seen his father pistol-whipped

and shot, suggests that they, father and son, have a little talk to

clear the air. And the kid blurts out, all in one over-inflated speech

balloon:

"Well, see, I wuz just thinkin' 'bout the shame and humiliation

I wuz feelin' while I watched you let your deputy git his brains blowed

out, then seein' you git beat like an old rug in front'a all my friends

and havin' ta realize that my paw is nuthin' but a yellowbellied coward

and how I gotta run away from home now so's nobody will know I'm yore

son—that's all."

Suddenly, it all makes sense. We're in Mad magazine.

Despite the measured pace of the visuals, this isn't a serious Western

at all. By articulating all this emotion into one highly unlikely

(for a twelve-year old in the 19th century American West) heaped-up

speech balloon, invoking every disillusioned son cliche in the universe,

Zimmerman shifts gears, turning his tragedy into a farce. Now the

Rawhide Kid's evening ablutions next to his campfire—doing sit-ups

in nothing but his speedos—are entirely understandable and every

stereotypical image thus far deployed becomes part of the joke. Zimmerman

is making fun of the mythology of the West. He's ridiculing the ideals

of masculinity and resourceful individuality that the Western has

traditionally represented.

Or is he? Dunno: those opening pages of nearly silent menace,

proceeding, step by inexorable step, towards the disastrous shoot-out,

seem too straight (oops) for high camp comedy or cultural satire.

If Zimmerman is supposed to be satirical, he's blown his assignment.

Maybe this expedition into the Old West is intended as a serious

treatise on masculinity and its relation to courage. The thematic

elements are all lined up: first, a sheriff whose courage and, therefore,

masculinity is questioned by his son (who, with an almost willful

blindness, fails to see that his father, far from being a coward,

acted with great bravery); then, a legendary gunfighter whose courage

and skill have long ago established his masculinity beyond reproach

or question; then—what next? If we follow the implications of

the ingredients, the sheriff's son will learn that masculinity is

defined by something other than the ability to beat a bad guy in a

gun fight. He'll learn that the Kid is gay, and that will destroy

"masculinity" as a measure of courage. And since masculinity is associated

with gunplay, gunplay by itself will be similarly discredited. And

courage will be defined by some other, better, means, with masculinity

itself irrelevant in the equation.

Or maybe the objective is to demonstrate that homosexuality

isn't necessarily effeminate.

Either way, what can we make of the claim that the Kid's homosexuality

is only implicit and not integral to the story? Clearly, it will have

to be explicit before it can become integral, and if Zimmerman is

aiming to redefine masculinity and courage with this tale, gaiety

will have to be both explicit and integral. Ditto if he's attempting

to erase effeminacy as an aspect of homosexuality.

Meanwhile, the Kid's nom de guerre, "the fastest gun in the

West," will, thanks to the symbolism of the cover with his gun dangling

between his legs, take on a new and somewhat derogatory meaning. Ain't

we got fun.

Like I said, a mess, a hodge-podge of contradictory meanings.

So far. NOUS

R US: COPYRIGHT EXTENSION. Mickey Mouse's beaming image appeared in the pages of various of the

nation's press in mid-January, accompanying the news that the Supreme

Court upheld, 7 to 2, the right of Congress to extend the copyright

protection afforded by the U.S. Constitution. Rather joyfully, I thought,

the announcement of this landmark decision suggested that somehow

Mickey was safe, and so we should all rest easier in our beds.

At issue was the 1998 law known as the "Mickey Mouse Extension

Act" because it came into being as a result of aggressive lobbying

by Disney, whose earliest representations of its pip-squeaky mascot

were set to slip into the public domain in 2003. To prevent that from

happening, Congress, persuaded by an ungovernable fondness for animated

rodents (not to mention Hollywood campaign contributions), extended

copyright protection an additional 20 years for cultural works, thereby

protecting movies, plays, books and music for a total of 70 years

after the author's death or for 95 years from publication for works

created by or for corporations. It was not the first time that Congress

had acted to protect Disney's mouse, but this time, Congress was challenged

in court by a collection of interested parties who maintained that

the Constitutional provision for copyright was intended to protect

a creator's right for only a limited time and that by extending this

protection every time it verged on expiring, Congress was, in effect,

granting copyright protection forever, a perversion of the original

intent of the Constitution.

In the majority opinion that sustained Congress, Justice Ruth

Bader Ginsburg cast aspersions on the "wisdom of Congress's action,"

but allowed as how ruling on the wisdom of congressmen is "not within

our province." Well, it is within my province, which, being that of

a tireless typist and hack writer, includes, naturally, all of the

known and unknown universe.

Judging from the number of extensions Congress has granted

over the last decades, we are perilously close to having copyrighted

material protected in perpetuity. This is clearly contrary to the

original intent of the Constitution, which states, in Section 8 of

Article I, that Congress "shall have the power ... to promote the

progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times

to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings

and discoveries."

The apparent logic embraces several notions: (1) that science

will not advance nor the arts flourish unless inventors and artists

can reap the financial rewards of their creativity; (2) that society

is enriched by the advance of science and the flourishing of the arts;

and (3) that, therefore, inventors and artists are guaranteed possession

of their ideas in a manner that will assure them of financial reward.

Neither the Disney corporation nor the Internet nor descendants

of the original inventors and artists are mentioned. I'm scarcely

a legal scholar, but it seems to me, in my innocence, that the chief

beneficiaries of this Constitutional intention are the society at

large and the creative individuals whose innovations are presumed

to nurture that society. As James Surowiecki said in The New Yorker

last winter, the Constitutional provision for copyright focuses upon

"compensation not control."

In other words, the essential purpose of copyright is to encourage

creativity by assuring that creators will be rewarded. Creativity

is, in human psychology, its own reward: creative personalities create

because their inner selves drive them to. Still, it's nice to have

bread on the table and various other creature comforts as a result

of one's creative endeavor—hence, the value of copyright.

Between the lines, however, another value lurks. The language

suggests that even after the expiration of copyright protection, society

at large will continue to benefit by enjoying the unfettered circulation

of such works as have, for a "limited time," been protected. Publishers,

for instance, who no longer have to pay permission fees to copyright

holders, could publish works in the public domain at prices that are

much more affordable to the general populace, thereby fostering learning

and pleasure and the like. The very use of the term "public domain"

implies a societal value beyond the private benefits that accrue to

copyright holders. Extending the protection of copyright deprives

the public of much of the benefit it might derive from creative endeavors.

Instead of promoting creativity as intended, saith the Washington

Post Weekly, the current law "has turned whole categories of American

national culture into heritable assets owned by people who had nothing

to do with their creation." And it inhibits free expression by restricting

the dissemination of cultural artifacts.

The framers of the Constitution clearly had no idea that corporate

ownership would ever be a factor, and yet corporate ownership is what

now drives the copyright bus. It is the corporate owners of copyrights

that profit by that ownership, not individual creators. Not any more.

Walt Disney is dead. Ditto George Gershwin, whose "Rhapsody in Blue"

teetered, momentarily, on the brink of the public domain until the

copyright extension was wedged into law.

Under the copyright law that prevailed in 1946, before the

first of Congress's 11 tamperings (over 40 years) took effect, Tarzan,

created in 1912, would have entered the public domain in 1968; Mickey

Mouse, in 1984; Blondie, in 1986; Dick Tracy, in 1987; Superman, in

1994. By the time the copyrights expired in these cases, the creators

had died. Their right to financial reward for their ingenuity and

inspiration, it seems to me, died with them.

If the characters they created earned enough during the creators'

lifetimes to compensate them appropriately, then the creators could

make adequate provision for their heirs to benefit, somewhat, from

their work. Not, probably, enough to guarantee a life of ease and

idleness, but enough, doubtless, to gratify a son or daughter or distant

cousin who had nothing to do with the original acts of creation.

My attitude here will doubtless infuriate creators who would

like their offspring, for generations into the future, to enjoy the

benefits of their progenitor's genius. And, of course, that would

be nice. But, in the last analysis, perhaps the best we can do—maybe

the best we should do—for our children is to bequeath

them the will and skill enough to make their own way in the world

and be self-sufficient. What more could any reasonable person want?

By 1984, when Mickey's copyright would have expired under one

of the previous dispensations, Disney, as I said, was dead. And, more

to the point, so was Ub Irwerks, who may have had more to do with

inventing the Mouse than the owner of the plantation. But the empire

built upon the Mouse is an entity in itself and doubtless offers financial

security enough to Uncle Walt's offspring, both biological and corporate.

And I have a hard time imagining the entire edifice crumbling to dust

just because Mickey's copyright expires.

Had the old law been restored, we would have reaped at least

one benefit: if copyrights are permitted to expire, eventually, young

campers can huddle around their campfires and sing Irving Berlin songs

without fear of ASCAP's invading the premises to claim licensing fees.

At the same time, the entertainment cartel could expect compensation

for Internet use of material still copyrighted, especially (and perhaps

only) if the use of that material generates financial gain for the

user. Even the oldest version of the copyright law is adequate for

this purpose.

As for Mickey the Mouse, the only image that would have drifted

off into public domain right away is the one in the earliest Disney

films, such as 1928's "Steamboat Willie" (which, ironically, is based

upon a Buster Keaton feature, "Steamboat Bill, Jr."—a creative

maneuver that the present copyright law would prohibit). The so-called

"modern" Mouse familiar today is a later creation and would remain

protected for several more years. Moreover, Mickey Mouse is not only

a character but a corporate trademark, and those never expire as long

as they are in use. More

about Copyright.

Too many of us assume that our work isn't copyrighted if it's not

registered with the Library of Congress. According to Amy Cook, writing

in Writer's Digest (November 2002), while registration provides

"certain benefits," registration is not necessary to establish copyright.

"Under current law," she writes, "a copyright exists as soon as an

original work of authorship is fixed in a tangible medium of expression.

You own the copyright to your work as soon as you write it down or

save it on your computer." Or draw it on a piece of paper.

Moreover, she continues, "as of March 1, 1989, it is no longer

necessary to put a copyright notice on your work." Such notice, however,

is helpful because it identifies you as the copyright owner—and

establishes the year of creation. The notice consists of three elements:

copyright symbol (or the word copyright or copr.), your

name, and the year. Fugitive

Peanuts.

As we reported here in December, the Schulz trust brought suit against

Mort Walker's International Museum of Cartoon Art (IMCA), demanding

return of Peanuts strips that were "loaned" not "given" to

the Museum. The IMCA has since unearthed letters specifically designating

about 50 strips as "gifts"; the others, about 16, will be returned.

Still

Starring.

My spies (well, one trained observer) reports that Dale Messick,

creator of the comic strip Brenda Starr and the Grand Dame

of Lady Cartoonists, is now living at home with her daughter, Star

Rohrman, near Santa Rosa, which was the cartoonist's hometown for

many years. Messick had been living in an assisted living facility.

She is frail and, alas, doesn't draw anymore; her eyesight and hearing

aren't what they used to be. After retiring from the syndicated rat

race, Messick, for a time, drew a humorous panel cartoon about a little

old lady, Granny Glamour, for local publication. When I visited

her, meeting her for the first and only time in 1998, she was still

living in her own apartment and would take a small pad of scratch

paper to the mall and make sketches of passersby as she sat there.

She had a wonderfully sardonic sense of humor, particularly about

little old ladies and fading glamour. Her granddaughter, Laura, was

recently accepted into the prestigious Actors Studio in New York and

has been in two plays produced off-Broadway already. Must make her

glamourous granny proud. FUNNYBOOK

FANFARE.

This time, instead of committing outright reviews, I thought I'd alert

you to my biases and prejudices about comics (as if they weren't apparent

already) by just telling you what titles I'm reading and the ones

I'm about to read and why. I've been reading 100 Bullets since

it began, and the title—the stories by Brian Azzarello

and, most particularly, the artwork by Eduardo Risso—still

grips me. I've started reading Y: The Last Man and 21 Down,

too: the concepts intrigue me, and the execution in both, so far,

is superb. I prefer Pia Guerra and Jose Marzan, Jr.,

in the latter title: their work is a little less fussy than whoever

is drawing 21 Down. (The credits are simply too cute: Jimmy

Palmiotti and Justin Gray are credited for "expressions"

or "language" and Jesus Saiz and Palmiotti for "metaphors"

and "permeation"—respectively—or "imagery" and "shade."

So who's drawing it? Penciling? Inking?) I've read several issues

of Fables, too; again, the concept (fairytale folk loose in

the general population but still dealing with their nursery rhyme

hang-ups) is engaging (although the last story arc, "Animal Farm,"

wasn't as gripping as the first story). I'm also picking up successive

numbers of Marville (but, having missed No. 2, I'm waiting

until I get it before reading the rest on hand) and Truth.

The latter is already inspiring racist ire because of the caricatural

style Kyle Baker has adopted for visualizing Robert Morales'

story. I knew that would happen. (You read it here, Opus 104,

kimo sabe.) Notice that I said the ire is racist, not Baker's drawings.

I picked up Batman: Gotham Adventures No. 58 because

Ty Templeton inked it. He's the one who launched the "animated

style" years ago, and I wanted to see if he still had the chops. Well,

sure. But it was his layouts and breakdowns that distinguished the

first several numbers of Batman Adventures, and while guest

penciller here, James Fry, does a little dancing here and there,

the layouts aren't the organic ballet that Templeton's were back then

(sigh). I'm following Three Days in Europe, written by Anthony

Johnston and drawn by Mike Hawthorne, for the sake of the

artwork as much as anything; I'm not into the story much yet, but

the pictures—crisp, simple linework with deftly spotted black

solids—are engaging.

I'm looking forward to reading the rest of the Deadline

mini-series. I'd seen only the first issue of this title and now have

the trade paperback. And I'm dipping a toe into Gotham Central,

too, just to see how that notorious city fares without a superhero

on call. I'm also looking forward to reading Pistolwhip: The Yellow

Menace from Top Shelf and The Yellow Jar from NBM. The

latter in particular because Patrick Atangan's careful drawings

evoke Japanese prints with great affection.

Finally, to shift to a more detailed review mode, we have "Volume

1" of Slapped Together Comics, an anthology of work by

sundry hands, the cover of which includes such pronouncements as:

"Laugh till it Hurts! (Or else...!)" and "Various Artists Doing Questionable

Material." This is an event from Crazy Moma Productions, cartoonist

Elena Steier being the nutcake. She draws the opening tale

by John Reynolds. Entitled "The Gratuitous Violence Patrol,"

it is not about a concerned citizens' group opposed to violence. It

is, rather, about two cops who respond to a call to rescue a little

old lady's cat in a tree and wind up blowing away half the neighborhood

in a spray of lead accompanied by a spray of the innards of any innocent

bystanders they happen to catch with one fusillade or another. The

cat is completely destroyed, naturally, and our heroic pair hand what

they assume is its remains ("or maybe a scorched tree branch—it's

hard to tell") to the little old lady, who then explodes. Blood and

gore galore, but all in good, clean fun. The book brims with this

sort of unfettered outrageousness, including the perfectly tasteless

"Dickie Pinkus Son-of-a-Bitch" by Jay Scruggs, a delight. (Scruggs

is presently the inker on Bud Grace's Piranha Club comic strip,

among other so-called "achievements"). All of the contributors have

other, presumably more productive and financially rewarding lives.

Among them are Ron Goulart, John Klossner, Martha Keavney, Tim Akin,

Bill Jankowski, Frank Mariani, Ted Steier (somehow related to the

Mama), Wes Alexander, Eric Feurstein, John Droney, John Kovaleski,

and Harley Sparx. I particularly relished Elena's "Flim Flam Paper

Dolls," which consists of scraps of descriptive prose accompanying

real cut-out clothing for the stars of Flim Flam Studios; Jankowski

and Mark Gallivan's crisply rendered "Tactical Investigations Team";

Ron Goulart's "The Funnies," probably the most far-reaching put-down

of comics on paper; and others of the Mama's imagination—"The

Revenge of Brunhilda" and "High School Reunion," to name two. But,

frankly, there's not a bad apple in this barrel of fun, which these

creators roll out with inventive enthusiasm, aiming, probably, to

see how they can exploit the medium to tell jokes in bad taste. With

128 6.5x10" black-and-white pages in square-bound paperback,

it's merely $19.95 from Crazy Mama Productions, P.O. Box 270-979,

West Hartford, CT 06127-0979; or, online, at http://striporama.com. THOUGHTS

ON HEROIC HEARTS. My

friend Joe Thompson, formerly, in the 1960s when all this was just

getting going, a technical intelligence officer at White Sands proving

ground in New Mexico, said, in reaction to the Columbia disaster:

So, what do I recommend? I recommend we accept that there were

always known to be some fairly high risks at certain strategic elements

of working with experimental aircraft (or space ships, if you will).

And I praise the history of past explorers—even those who founded

the New World, or rounded the Horn, or who traveled the route of Captain

Cook. My regret is that our society, convinced of the great value

of human life, has been sold on the idea that there will be NO accidents.

I too value human life, and I too feel the horror of the disaster

of the loss of these outstanding men and women. But I also value their

spirit and their efforts and their accomplishment. And, given the

chance, I would jump in a second to go on the next shuttle flight

if it could serve any purpose—even as an example to others.

That is the magnitude of the accomplishment of these people—be

they the first man in space, Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, or American‑supported

astronauts, or those lost before and those dozen, likely hundreds,

maybe thousands, yet to be lost in the future. So, for me, it is a

time to praise the spirit of the human being, time to praise the many

who have gone before—Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus (after

whom this space shuttle was presumably named), Lewis and Clark, and

certainly Ernest Shackleton. It is time to praise the seven who have

just perished in their wake,

and it is time to be mindful of the many yet to seek and explore,

and some yet to die. It is a time to find out what happened, to seek

to avoid it in the future, to commit to the next generation of technology,

and, above all, it is a time to look to the skies and say, "That is

my Star! I will go chase Her!!!"

All of which, reminds me of lines from Tennyson's Ulysses: Come,

my friends, 'Tis

not too late to seek a newer world. ...

for my purpose holds To

sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of

all the western stars until I die. ...Though

much is taken, much abides; and though We

are not now that strength which in old days Moved

earth and heaven, that which we are, we are— One

equal temper of heroic hearts ... strong in will To

strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

—not to mention the great Goethe, for whom striving was

all. To be human is to strive. To fail to strive—to give up

striving—is to give up being human.

We mourn the deaths of the seven Columbia astronauts not because

they died; hundreds of people die every day without our even knowing

about them. Nor is our mourning in honor of the uniforms they wore;

dozens of servicemen and women die in peacetime every year, virtually

unnoticed by the population at large. So why is our mourning so seemingly

excessive in this case? Because, I think, the extravagance of our

mourning for these seven souls matches the extravagance of their undertaking.

Were they not attempting something large, our grief and sense of loss

would not be so great. "Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp,

or what's a heaven for?" Next time, our grasp will be surer, but,

being human, we will ever reach for something more, above, and beyond....

To stay 'tooned, click here

and get yourself transported to the Main Page, where the content of

this website is mapped out and my very own books are offered for sale

(and previewed with but one more click of your clicker). BOOK

SALE.

Some First (and other) editions by Bill Mauldin or Al Hirschfeld.

Up

Front, Bill Mauldin's classic book about

men at the front in wartime, liberally illustrated with Willie and

Joe cartoons from WWII's Stars and Stripes, the serviceman's

newspaper. This is a first edition, 1945, not the Book-of-the-Month

Club edition. When I bought it, it lacked a dust jacket, so I've supplied

one—a color photocopy of the dust jacket on my own first. Only

$12, kimo sabe. Back

Home,

Bill Mauldin's account of his post-war adventures as an angry young

cartoonist and ex-soldier trying to adjust to civilian life (when,

in his case, he'd never had a civilian life as a adult before). Liberally

illustrated with his syndicated cartoons of the period. I have two

copies, both are first editions (1947) but only one has the original

dust jacket; the other has a dust jacket I made by color-copying the

other book's dust jacket. The book with the original dust jacket is

$12; the one with the photocopy jacket is $10. The

Brass Ring,

Bill Mauldin's autobiographical account of his adolescence in the

Southwest, his budding cartooning career in Chicago and in Phoenix,

his entry into the Army by way of the National Guard in September

1940, and his subsequent career as a soldier cartoonist who earned

the Pulitzer Prize with his Willie and Joe cartoons by the time he

was 23 years old, at the time, the youngest recipient of the Pulitzer.

This is not a first edition; it's the second printing, but it comes

with an intact dust jacket and a special insert—on nifty paper,

a copy of his 1945 Pultizer-winning cartoon. Merely $10. Listen

to the Mocking Bird by

S.J. Perelman, profusely illustrated by his long-time friend, Al Hirschfeld,

a 1949 first but no dust jacket. At first blush an autobiography (because

Hirschfeld's caricature of Perelman appears throughout), it isn't:

it is a collection of humorous pieces that originally appeared in

The New Yorker. But the reason for owning the book is Hirschfeld's

exquisite drawings, not Perelman's prose (which is perfectly acceptable,

don't misunderstand; but I originally bought this book for the drawings).

Unusual among Hirschfeld's oeuvre, the drawings are not caricatures

(except for Perelman's) but imaginary characters of the artist's own

concoction. Every drawing is embellished with a second color overlay.

Just $10. Shipping. As usual, add $3 postage (Media Mail)

and packaging for one book, plus $2 each for every additional book.

For payment instructions (and to verify availability), e-mail me using

the handy e-mail button at the end of the next opus (the previous

posting)—just scroll all the way to the very end. To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |