|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Opus 394 (July 17, 2019). We’ve packed a lot into this posting in order to showcase what we do here for visitors during Open Access Month when even non-$ubscribers can wander the environs. (And after you have, we hope you’ll $ubscribe.) In our News Department this time, it’s a Dire Edition, full of Woe and Tumult and Ominous Portents for the Future. Our news department weeps— Mad dies, and long-time Mad caricaturist Tom Richmond tells us how it happened, NY Times gives up editoons (and editoonists scream—rightfully—even though the Times hasn’t had editoons since 1958),we reprint a Politico essay “End Times of the Political Cartoon,” Esquire editors got fired or quit, DC axes Vertigo, and The Nib loses funding. But all is not gloom and hair-tearing and breast beating. We have a joyful pictorial report on the Denver Pop Cult Con, ditto FCBD, news of early NY Times editoonist (yes, as recently as 1958), and reviews of Enemy of the People: A Cartoonists Journey (Rob Rogers’), C.C. Beck’s Captain Marvel in Shazam, and of some recent comic books Deadly Class, Sham Comics, Thumbs, and an up-date on the prolongation of Doomsday Clock (Nos.7-10). That’s a lot. And maybe you don’t want to read it all—at once or ever. To assist you in finding what you want and skipping what you don’t want, we’ve prepared this listing of what’s here, in order, to wit (the longest ones are asterisked*)—:

Anniversaries Galore

NOUS R US Mad Dies with a Whimper *Remembering How It Happened By Tom Richmond The Nib Unfunded IDW Publishing Sales Down

A Break in the Monotony

*CARTOONLESS TIMES GIVES UP CARTOONS Teapot Tempest: Early Times Editoonist Editorial Cartooning during the 1948 Presidential Race Front Page Editoons; 3 Editoonists at the Star

CANDADIAN CARTOONIST GETS THE AXE

Esquire Magazine Editors Fired or Quit

Good News At Last: New Online Editoon Newsletter The Meuller Report Graphic Novel DC Axes Vertigo

The World of Comic Art at Hindsight Another Anniversary: Pin-ups

ODDS & ADDENDA Dwayne Johnson’s BlackAdam Frank Thorne Is 89 More Photos at the NCS Fest

DENVER POP CULT COM *A Pictorial Report

Exhibiting at FCBD

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of—: Sham Comics Deadly Class Thumbs Doomsday Clock, Nos.7-10

Trumperies EDITOONERY D-Day Toons Picking Up Where We Left Off—: *CARTOONLESS TIMES GIVES UP CARTOONS And the Editooning World Goes Bonkers

About Those 2,000 Editoonist in 1900

*END TIMES OF THE POLITICAL CARTOON By Jack Shafer at Politico

*NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Reviewing the Bump and Grind of Daily Strippin

BOOK MARQUEE Short Review of—: Enemy of the People: A Cartoonist’s Journey

BOOK REVIEWS Longer Book Review of—: *Shazam: The World’s Mightiest Mortal, Vol.1

A-GAGGING WE SHALL GO Magazine Cartoons in The American Bystander

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Political Nonsense and Sense

PASSIN’ THROUGH Everett Raymond Kinstler, 1926-2019

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics.

And our customary reminder: when you get to the $ubscriber/Associate Section (perusal of which is restricted to paid subscribers), don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

ANNIVERSARIES GALORE

You can read about Popeye in Harv’s Hindsight March 21, 2004, and Ripley in Opus 332. We’ll give Popeye another party next time in Opus 395, and we’ll also celebrate Stonewall with a review of Comrades from Sticky Graphic Novels.

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

MADDENING NO MORE; JUST CRAZY INSTEAD It’s true. The

rumor’s confirmed: Mad magazine, after setting the pace for satire in

America for 67 years, will no longer publish new material. The magazine, which

was converted from a four-color comic book to black-and-white magazine format

in DATE, will be entirely reprint after the release of No.10 (the West Coast

numbering) in September. End-of-year specials will continue to carry new material, reported Milton Griepp at icv2.com, and DC will also continue to publish Mad books and special collections. But in regular issues, nothing new except the cover. “Age hits everybody: it hits magazines, it hits the movies, it hits technology,” legendary Mad cartoonist Sergio Aragonés told the Washington Post. And so the end of Mad is “a logical development. “What made it great,” he went on, “— was the writers and the artists. It was an incredible group — and the team was special because of the trust between editors and the talent.” The work of Aragonés, 82, has appeared in nearly every issue since 1962. And so it ends. But not without a hail and farewell from some of the legions of cartoonists and humorists who have been influenced by it. Peter Kuper: “Artists like myself who have been so influenced by it are going to continue to do something that is essentially the result of Harvey Kurtzman’s influence and Mad’s influence over the years. You’ll see Mad around no matter what, as long as we live in this mad, mad world.” Art Spiegelman: “Mad was, ‘The entire adult world is lying to you, and we are part of the adult world. Good luck to you.’ I think that shaped my entire generation.” Tom the Dancing Bug (Ruben Bolling): “ One of the great Institutions, not only in comics history, but in the history of American humor.” Jason Chatfield: “Mad shaped who I became as a cartoonist, as a comedian and as a deranged man-child of a human today. ... Being published in Mad was a massive life-long dream, and I’m grateful to have been part of it before the door slowly swung shut.” Tom

Richmond: “Its smart satire and irreverent and self-deprecating humor

spawned entire generations of humorists who brought those CNN’s Jake Tapper, who drew a comic strip for Roll Call in the ’90s and early ’00s: “There are generations of Mad readers who learned subversiveness, dark humor, hatred of idiocy and bullies, and the quality of not taking ourselves too seriously from that esteemed magazine. This is a big loss for cartooning, for humor, and for the young American ethos.”

No Authorities to Ridicule Anymore. At the Washington Post, David Von Dreble remembers the Mad of his youth when the magazine reached its peak circulation, 2.8 million in 1973. “Every feature mined the same ironic vein,” he recalls, “—the world’s a joke, a sham, a tale told by an idiot.” He remembered the most outrageous of Mad’s covers: an upraised middle finger. “The blowback was sufficiently intense that publisher William Gaines never went there again. But it wasn’t the readers who objected; it was our moms, dads, ministers, librarians. Our oppressors.” And

newsstand operators, many of whom refused to display the magazine. Gaines

issued a letter of apology. To Von Dreble, the passing of Mad signals an ominous change in our culture. “To be subversive requires a dominant culture to subvert. Mad was the smart-aleck spawn of the age of mass media, when everyone watched the same networks, flocked to the same movies and saluted the same flag. Without established authorities, it had no reason for being. Like the kid in the back of the classroom tossing spitballs and making fart sounds, a journal of subversive humor is funny only if there’s someone up front attempting to maintain order. “We now live in a time when everyone’s a spitballer,” he continued, “—from the president of the United States on down. America elected the world’s oldest seventh-grader in 2016.” He went on: “Today, whether we’re doing history or current events, commerce or religion, we’re awash in iconoclasm but nearly bereft of icons. Everyone’s a court jester now, eager to expose the foibles of kings and queens. But the joke’s on us, because we no longer have authority figures to keep in check. We’re needling balloons that have already gone limp. “Some say Mad lost its edge to its offspring, from Bart Simpson to Stephen Colbert. Yet I wonder how long its influence could have continued after the extinction of the adult establishment. Not just a magazine, but a world, has ended.” All of us grew part-way up on Disney, which offered a wholesome happy vision of the world that we were delighted to accept. Then we grew up a little more and discovered Mad, which offered a different—and more truthful—view of life in America, an essentially grasping, greedy, self-promotional life. Hereafter, there will be no corrective for Disney.

Meanwhile, as if in response, Marvel is offering a one-shot revival of its Crazy for release in September. Crazy, Griepp notes, was a satirical humor magazine published by Marvel from 1973 to 1983, some of the peak years of competitor Mad. The new one-shot will be written by Gerry Dugan, Frank Tieri, Jon Adams, and others; with art by Don Simpson, Scott Koblish, Jon Adams, and more. The cover is by John McCrea, with a variant by David Nakayama and another variant to be announced. The decision to publish the one-shot was "thanks to a momentary lapse in sanity on the part of a few over-worked editors and a gang of writers and artists ready to take advantage of it," according to the solicitation.

REMEMBERING HOW IT HAPPENED By Tom Richmond, July 4 YESTERDAY CONTRIBUTORS TO MAD MAGAZINE officially got the news that, after 67 years of continuous publication that began with Harvey Kurtzman‘s brilliant comic book and eventually evolved into the magazine that forever changed the world of satire and humor, Mad will stop publishing new content after issue No.10. The magazine will continue with all reprint material under new cover art but will be sold only via the direct market and current subscriptions. Newsstand distribution will cease and obligations to current subscribers will be fulfilled with these reprint issues. It’s my understanding that new or extended subscriptions will no longer be available, and once current subscriptions expire that also will be at an end. DC will continue to publish books and special collections under the Mad brand. Of course we all knew this was coming. Last week DC laid off one art director and three of the four remaining editors. Not too many magazines can keep publishing without any staff. I could go on and on about the end of an era and a true American original, about how Mad had an incalculable influence on satire, comedy in general, and the humor of the entire planet, how its pages regularly featured some of the greatest cartoonists who ever lived like Kurtzman, Jack Davis, Mort Drucker, Wally Wood, Will Elder, Al Jaffee, Sergio Aragones, Don Martin, Paul Coker … too many to list, really. I could go on and on but all that is meaningless with respect to today. None of that history can be taken away, and none of it is a reason for the next issue to come out. In the end in this day and age, the only reason anything is allowed to exist comes down to money. If something is profitable, it continues. If it is not, it ends. Mad is ending for the same reason anything ends… it’s all about the Benjamins.

THE SIGNS HAVE BEEN ON THE WALL for a long time now. They really started with Bill Gaines‘ passing in 1992. Gaines sold the magazine to the Kinney Corporation in the early 1960s, but as part of the deal he was given total autonomy to publish the magazine as he saw fit. In other words, the corporate overlords had to keep their hands off. Eventually Kinney absorbed DC Comics and then came Warner Bros, but that original Gaines deal was still valid even with Mad being now a part of the Time-Warner behemoth. Once Bill died however, the slow but unstoppable taking over by the suits began. In the mid-90s the Madison Avenue offices were closed, and the staff moved into the DC Comics headquarters— the first overt sign of cost cutting. Editors Nick Meglin and John Ficarra were still allowed to keep Mad “mad,” but the continued slide of circulation started the pressure mounting to increase revenues. There was a time in the 90s when some DC brass were mulling over rebranding Mad as some kind of teenage-orientated pop culture hip-hop publication. But cooler heads prevailed, and they settled for a visual “revamp” which included the italicized logo. Sales continued to decline. In 2001 Mad switched to a color format with issue No.403, and started taking advertising, all of course in an effort to increase sales and revenues. In 2004, longtime editor and unsung hero of Mad’s “voice” Nick Meglin “retired”, cutting DC’s staff costs further. I’d say I’m glad Nick did not live to see this day, but nothing could ever happen in this universe to make me happy Nick has passed. It was in early 2009 that the writing was really on the wall. As of issue No.500, Mad went from monthly publication to quarterly. Clearly DC was now looking at Mad’s bottom line with an executioner’s eye. That only lasted for about a year when Mad increased to bi-monthly in 2010. However, one thing that many people do not know is that Mad’s page rate for contributors was cut nearly in half at that same time. I’m sure certain longtime contributors kept their old rate, but the rest of us saw a drastic drop in pay for the same amount of work. In 2013, DC packed up its New York offices and moved the whole operation to Burbank to the Warner Bros complex (so you see it wasn’t just Mad that WB was looking to cut expenses with). In typical Mad fashion none of the Mad staff, all life-long New Yorkers, were willing to move. So, DC was faced with either cancelling the title, moving it anyway with no one to run it, or keep Mad in New York City. To their credit they did the latter, and for four years Mad kept on publishing in slowly shrinking new office space. In 2017 DC finally pulled the trigger on a move out to Burbank for Mad. The new West Coast Mad made it 10 issues.

DESPITE ALL THE SIGNS, I actually had a lot of optimism that the new Mad had a chance. First, their choice of hiring Bill Morrison as Executive Editor/VP was inspired. Bill was a guy who knew humor, who had a deep affinity and knowledge of what made Mad “mad,” was very smart, savvy, and plugged in to the greater world of comedy, and was a terrific artist in his own right. He put together a young and hip staff of editors and really took Mad into the 21st century, especially with social media. Then they fired him in January of this year. We all knew it was over then. Just a matter of time for the rest of it to catch up. What’s sad is that Mad was actually having a mini-creative renaissance under Bill. Their cover for issue No.4 won a Rondo Hatton award for horror genre art. The feature “The Ghasilygun Tinies” in that same issue, written by Matt Cohen and drawn by Marc Palm, received a major amount of national attention and is nominated for an Eisner Award. The magazine itself is nominated for an Eisner for best Humor Publication this year. Several high profile comedians contributed articles for the magazine. But critical success is meaningless. The bottom line is all that matters. Ironically circulation has increased but obviously not to the point that the numbers worked. Then they fired Bill. Did I already say that? It bears repeating. SOME PEOPLE ARE SPECULATING that maybe DC will sell Mad to another company that would keep it going. That is not going to happen. One of the few bad things about working for Mad is that over its entire existence, with just a very few exceptions, every piece of writing and art published in the magazine was done as “work for hire”— meaning E.C. Comics (and thus DC/Warner) owns the copyrights to that work. That’s 67 years of content by some of the greatest comics artists ever, and some of the most influential pieces of published humor ever printed. That’s an extremely valuable catalog for reprints, collections, etc. that costs the owners of that content nothing. No way DC sells that. At best they could possibly license out the Mad brand for another publisher to publish some version of the magazine, but if a printed version was financially viable none of this would be happening. Despite what some people will say, Mad was not suffering from poor content. Not everything the Burbank crew threw at the wall stuck, but Mad still had a lot of sharp content and was virtually the last place for such visual comic humor to be seen in a single publication. Mad was still Mad, especially when it was still in NYC, but apparently not enough people were buying it to offset the increasing costs of publishing/distributing. Thus, it’s ending. DC has almost 70 years of cost-free content to milk, why would they need to spend money on producing new stuff? It’s been a real privilege for me to have been a small part of what was hands-down THE greatest comics/cartoon publication in history. I was lucky to have gotten started with Mad back in 2000, when Nick and John were still in charge and Mad was arguably still the Gaines era Mad. I saw my work published alongside some of my cartooning heroes like Mort, Al, Sergio, Paul, Angelo Torres, Sam Viviano, and many others, and I got to work with writers like Dick DeBartolo, Arnie Kogen, Desmond Devlin and other incredibly funny and talented people. More than that, I was able to call these people both colleagues and friends. So. What’s next for me? I did the art for two parodies in issue No.9, plus I did the cover (kind of a special circumstance, which is a long story I’ll share when the issue comes out). I’ve got at least one feature to draw for issue No.10, possibly two. Then it’s on to new adventures in the world of cartooning and comics. On the bright side, no matter what I work on next I can virtually guarantee the ratio of time and effort spent vs. the amount of actual pay for the job will be better balanced. Mad was much more a labor of love than it was for the paycheck. I will say— it’s hard to be one of the ones that has to turn out the lights. Thanks for the many years of laughs, Mad. RIP.

RCH Fitnoot. How can you rest in peace if you’re lyin’ there laughin’? Kurtzman would have a great time ridiculing the idea of killing a magazine that wasn’t making money. How typically capitalistic—just the sort of thing he scoffed at and prompted laughter about.

THE NIB UNFUNDED The online cartoon commentary site The Nib will lose its funding at the end of July. After three-and-a-half years, First Look Media is backing away and cutting loose founding editor Matt Bors and his team but will hand over the publication/site to Bors, who plans to continue The Nib. Said Bors: “I founded this publication almost six years ago to highlight political and non-fiction comics in a media environment that doesn’t support them. I refuse to walk away from this project or let it die after the successes of our last year. There are too many of you who have expressed support and written to say how important it is to you. “This will be a major setback but I will be devoting all my time to continuing this publication with contributions from all the editors and cartoonists who have made this publication what it is.” The fourth issue of The Nib’s print magazine is at the printers and is scheduled to be shipped this month. “The fifth issue, the Animals issue,” said Bors, “is in the works, and I will be printing it independently.” Addressing The Nib’s readers and subscribers, Bors said: “Your support over this last year has allowed us to publish hundreds of comics and create four magazines that we are really proud of. Now your direct support is more crucial than ever; our only funds going forward will be those our members have pledged each month to support us.” He vows to keep going. And remember: he kept it going for almost three years without First Look Media.

IDW PUBLISHING SALES DOWN, LOSSES WORSEN IN FISCAL Q2 IDW Publishing suffered a decline in sales and an increase in losses vs. the year-ago period in its fiscal Q2 ended April 30, according to the company’s announcement, filings, and conference call, reported Milton Griepp at icv2.com. Sales were down 15% for the quarter to $3.74 million. Reasons cited included declines in direct market and game sales, partially offset by a decline in book market returns and increases in specialty and digital sales. Operating losses from the Publishing division were $1.63 million, an earnings decline from a $1.39 million loss in the year-ago period. The company is promising better results going forward, with what it says is a stronger release schedule for the second half of its fiscal year (May-October). IDW Media Holdings CFO Ezra Rosensaft spoke of operational changes at IDW Publishing. “The IDW Publishing team is making operational changes to focus more tightly on market opportunities and higher margin offerings, including controlled franchises suited for development by IDW Entertainment,” Rosensaft said.

A Break in the Monotony MAGA Stolen Off the Web I bet you thought MAGA stood for Make America Great Again. Well, according to info on the Internet, the word "maga" in Nigerian popular slang means something entirely different. In that language it means "a fool, an idiot. Someone easily duped. Used to describe a stupid person who has fallen prey to a con artist. A sucker." Ring any bells? And people— by wearing the hats— are advertising their inability to see that they are the victims of fraud. —Linda

And now, for a little comic RELIEF, go to http://gamescene.com/The_Urinal_Game.html It’s an entertainment mostly for men, sorry ladies (although if you want to see how it works, it’ll tell you encyclopedias of things about the males in your life). But the entertainment (as I said) reveals a lot about the male psyche. More, perhaps, than we care to admit. But if you can play the game, you’re admitting it. And you’ll be mentally healthier in consequence.

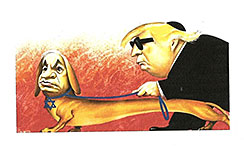

What’s Wrong With This Picture? CARTOONLESS TIMES GIVES UP CARTOONS And the Editooning World Goes Bonkers THE NEW YORK TIMES, which doesn’t print editorial cartoons, announced on June 10 that it wouldn’t be printing editorial cartoons, and editorial cartoonists, pitchforks and torches in hand, took to the streets in protest. Does that make sense? Well, yes. Although the Times is notorious for not printing political cartoons, it does print political cartoons in its international edition. Until July 1. After that, no more. The Times used to publish editoons in its weekly news review section but gave that up several years ago. And that left the international edition as the Times’ sole venue for editorial cartoons. The

trouble started on April 25 when the Times blundered into a hail-storm

of social media protest over a cartoon in the international edition that

depicted a blind President Donald Trump, wearing sunglasses and a yarmulke,

being led by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who’s a guide dog with

a Star of David around his neck. The watch-dogs of the world saw anti-Semitic “tropes” in the imagery: 1. Putting a yarmulke on the U.S. President in negative way. 2. Putting the face of the Prime Minister of the Jewish state on a dog. 3. Using a Star of David on the collar. 4. Implying the U.S. is ‘blindly’ led by Jews and/or Israel. We analyze the fallacies inherent in this kind of thinking—while acknowledging the validity of the criticism—in Opus 392A. For our present purposes, we’ll return to the scandal at hand after noting that the Times issued an apology for the April 25 cartoon, admitted that the cartoon was “anti-Semitic,” and announced that it would discipline the (unnamed) editor who chose to publish the cartoon (saying he lacked “adequate oversight”), and the paper would enhance its bias training. The Times also indicated that it will no longer use the syndication service that supplied the cartoon. Then came the announcement of June 10, landing like a turd in the political cartooning punch bowl. The consequences of all this—mostly in irrate and exasperated reaction among editoonists—we’ll delve into at some length. But not right now. We’ll take it up in detail further down the scroll, right after our Editoonery Department. For the present, we’ll plunge instead into----:

WAIT—WHAT? A Tempest, Perhaps, in a Teapot? Amid all the sturm und drang over the New York Times’ dropping its editorial cartoon are two factoids sometimes overlooked in the excitement. First, the loss at the Times is in the international edition of the paper not the domestic edition, the one we all read (or used to). Not worth making a fuss over? In these times with staff editoonist jobs falling away, left and right, any diminution of the role of the editorial cartoon is worth getting worked up about. The second factoid: the domestic edition of the Times hasn’t had a regular editorial cartoon since 1958 when Edwin Marcus retired after 50 years on the job. These days, it is generally supposed that the Times has neverhad a staff editoonist. That may be because most of those making the claim weren’t even born in time to see Marcus’ farewell cartoon. Or they were too young to know what an editorial page looked like let alone an editorial cartoon. For those who think the Times has never had an editorial cartoon, we must pause at Marcus. He became the paper’s editoonist in 1908, succeeding Hy Mayer, who was the first Times editoonist. So in the history of the Times, it had at least two editorial cartoonists. Marcus had a talent for getting likenesses, they said, and before World War I, his cartoon appeared full pageon the first page of the paper’s drama section. Full page! Probably, however, not what we’d call an editorial cartoon these days. More like Al Hirschfeld maybe. “I got to know all the stars of the theatre,” he told John Chase, who was putting together a book about American editorial cartoonists, Today’s Cartoon (1962). “Will Rogers and Flo Siegfeld were my closest friends,” Marcus continues. “I did the Bull Durham ad drawings for all Will’s quips, and spend hours with Ziegfeld laying out his display pages. After twenty-five years, the dramatic page drawings began to interfere with the cartoon, and the office let me drop it.” Photographs took the place of Marcus’ pictures. For

almost all of the fifty years of his career, Chase reports, Marcus worked at

home. “Weekly, he made two trips down to the Times—Thursday mornings

with about a dozen roughs to show his editor, and Fridays to turn in his

finished cartoon.” So the Times’ longest tenured editoonist drew only one cartoon a week. Still, he was on staff and he did editorial cartoons. So the Times did, indeed, have an editorial cartoonist at one time, and a long time it was. When asked why he had never been replaced following his retirement, Marcus told Chase, “the editor said something about my being ‘an institution.’” Yes. After fifty years, an institution. And now, after sixty-one years since Marcus left, it’s time to re-institute the institution. The teapot is boiling dry.

Editorial Cartooning, a book published in 1949, values the journalistic function of editooning. It was written by Dick Spencer III (1921 - 1989), a graduate of the University of Iowa with a degree in Journalism. Following World War II, he was a staff member at Look magazine and later was an instructor of magazine production and editorial cartooning. For most of his life, he was publisher of Western Horseman magazine. Spencer’s book about editorial cartooning is not so much a history of the species as it is a how-to book (How A Cartoonist Works, Aids to the Trade, Pen Points for Poniards), but the last chapter dwells for a few pages on the extraordinary and unexpected outcome of the 1948 Presidential Election—which Harry Truman, the incumbent, won over Thomas Dewey, who everyone expected to win. The editors of the (Washington D.C.) Star realized that this election would go down in history as one of our greatest political surprises, and they sought to memorialize the occasion by publishing a book of the editoons of their staff cartoonists, The Campaign of ’48 in Star Cartoons. “The introductory text explained the significance and purpose of the book,” writes Spencer, “and is worthy of reprinting here.” And so he reprints it; and we do, too (in italics)—:

A cartoonist is many things to many men. To some he is a clown, tickling the world with the point of his pen. To others, he is a wit, drafting cogent comment on the course of events, coming through on deadline with the day’s perfectly incisive remark. To still others, he is a sort of intellectual gadfly, stinging sinners to repentance with a barb of ridicule. But if he is true to himself, he also is a reporter in the finest sense of the word, telling the story day by day with maximum economy,clarity and truth. The Star presents here the story of this election year,as told in the daily work of its three cartoonists (Clifford Berryman, his son Jim, and Gib Crockett). ... These pages will remind you of things you want to remember about the ten months leading up to Election Day, 1948, and its astounding climax. The cartoons reproduced in this book first appeared on Page One of the Star. Not all the campaign cartoons used in the Star are here, of course ... But the story is all here, together with the humor, wit, and sting. So is a lot of the truth.

Did you notice? The Star had THREE EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS. Three! In 1948. And many newspapers of the day had more than one. And did you catch that other glimpse of yesteryear—“appeared on Page One of the Star”? The Star wasn’t alone. That’s how highly newspaper editors once thought of their editorial cartoons. They ran them on the front page. But no more. Sadly, no more. Defeated, gutted, undervalued. Its absence, hazardous to democracy.

Nearby,

I’ve posted a few of the cartoons from the Star book. It’s a revealing knot-hole look into the visual

history of editorial cartooning. The first thing

CANADIAN CARTOONIST GETS THE AXE U.S. editoonists aren’t the only members of the ink-slinging coterie loosing their jobs. Canadian Michael de Adder has been let go from Brunswick News Inc. newspapers just days after his cartoon depicting Donald Trump playing golf next to the bodies of two migrants went viral. The

original image of the Salvadoran father and daughter made headlines in June,

bringing to light once again the issues around migrants risking their lives to

enter the U.S. At the end of June, Emma Davie reported at cbcnews, de Adder tweeted that he was let go from BNI papers. "It was terrible," de Adder told the CBC News on July 1. "I gave them 17 years." De Adder is a freelancer and apparently submitted cartoons to BNI on that basis. And he doesn’t know, exactly, why his arrangement with BNI was terminated. No one told him. DeAdder thinks it was because his cartoon was critical of Trump. “It’s the most logical explanation,” he said. He’d been told that BNI wouldn’t publish cartoons about Trump. On Twitter, de Adder said that every Trump cartoon he submitted for the past year was axed. Although he didn’t draw Trump cartoons for BNI, as a freelancer, he drew some for his website. He did three Trump cartoons in the previous two weeks; all went viral. BNI denies the claim that the golfer Trump cartoon was the reason for terminating its freelance contract with de Adder. "This is a false narrative which has emerged carelessly and recklessly on social media. In fact, BNI was not even offered this cartoon," said the company in a tweeted statement on Sunday. The company had been negotiating to bring back a “reader favorite,” Greg Perry, and had reached a decision and therefore ended its arrangement with de Adder. The situation raised some red flags for Wes Tyrell, president of the Association of Canadian Cartoonists. "This is a smelly circumstance," Tyrell said. "Trump cartoons have been the bread and butter for just about every publication out there since 2016, 2015. Why are they not running them?" He said it's especially concerning to see editorial influence creeping up on cartoonists. "To me, that's a form of censorship. And it's unacceptable." But de Adder said he doesn't believe it was entirely censorship. "They wanted to manipulate the content," he said. According to his website, de Adder freelances for the Chronicle Herald of Halifax, the Toronto Star and Ottawa Hill Times. In an emailed statement from the Ottawa Hill Times, editor Kate Malloy said the paper will continue to work with de Adder "for many years to come." "He's one of the most talented editorial cartoonists in the country. He pushes the envelope, but that's what a great editorial cartoonist does," Malloy said. "We're lucky to have such a talent." Tyrell said who BNI chose as their new cartoonist is telling. "No disrespect to this other cartoonist at all, but this is an inoffensive, non-provocative, run-of-the-mill individual, cartoon-wise. Mike de Adder is an entirely different level," Tyrell said. "He's undeniably the voice of New Brunswick." But de Adder said he doesn't regret sharing the Trump cartoon. "I regret that I won't have cartoons in newspapers in my hometown that friends and family can see." “The hardest part in all of this,” he said, “— I have a mother with dimentia in New Brunswick who has a hard time remembering her family at times.But she knows her son draws cartoons. Part of her daily routine is to open the @TimesTranscript and see her son's cartoon. A cartoon that won't be there anymore.”

ESQUIRE MAGAZINE FACES TURMOIL AMID MASTHEAD EXODUS That’s the headline over Keith J. Kelly’s story in nypost.com on June 6. Kelly goes on: “There is chaos at Esquire, as the entire top of the masthead has either resigned or been let go following the resignation of Editor-in-Chief Jay Fielden last week.” Maybe one of the reasons cartoon editor Bob Mankoff was vague about Esquire when I talked to him at the National Cartoonists Society’s convention in May was that he saw the chaos coming. In any event, he was one of the casualties. Kelly continues—: Bruce Handy, features editor, who one source said was the choice of Hearst Chief Content Officer Kate Lewis to be interim editor after Fielden’s resignation on May 30, instead turned it down and resigned when Fielden told staffers he planned to leave. Michael Hainey, the No. 2 as executive director of editorial, was in Cannes the day Fielden resigned. Earlier this year, he had turned down the Gawker reboot job that eventually went to Dan Peres. As soon as Hainey returned from France, he resigned. Helene Rubinstein, the number three who carries the title editorial director, is also said to be exiting. The newest rumor on a potential replacement for the top job is Michael Sebastian, who is running Esquire.com. He could not be reached for comment. More staff cuts on June 5 only further fueled the rumor that Esquire, which in 2019 cut back to eight issues from monthly, will reduce its print issues further, possibly to six times or quarterly next year, in favor of a more digital and video-oriented strategy for the future. ... A least six full-time staffers and many of the regular freelance writers were told their days were over this week. Among that tier of departures: Raul Aguila, design director; Emily Poenisch, entertainment features director; Matthew Marden, style director; Ryan Lizza, chief political correspondent; Bob Mankoff, cartoon and humor editor; Ash Carter, senior editor; and contract writer Maximillian Potter; as well as writers at large Alex French and Stephen Rodrick. Esquire was rocked late last year when Hearst Magazines President Troy Young and Lewis decided to kill a story on years of alleged sexually predatory behavior by prominent Hollywood director Bryan Singer, who directed “X-Men” and “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Singer denied the claims. Killing the story created a lot of anger directed at Young and Lewis. “The mood had been getting more and more dismal even before the Bryan Singer thing exploded,” said a source. While corporate sees digital as the future, the source said that many editorial veterans were angry that they were kept apart from the digital.

NEW ONLINE NEWSLETTER Of Political Cartoons BUT THE NEWS IN THE PUBLICATION WORLD isn’t all bad. A hardy band of liberal and conservative cartoonists have joined together to launch Counterpoint, a free weekly email newsletter with original content from some of the best cartoonists working today. The creators behind the project — including Kal Kallaugher, Rob Rogers, and Nick Anderson — quietly began rolling Counterpoint out a few weeks ago. They got a boost in June in the wake of the New York Times blunder when CNN's Jake Tapper tweeted he had signed up for the free pub. Here is their press release—: We are pleased to announce the publication of Counterpoint, a revolutionary new approach to the publication and distribution of editorial cartoons. Our motto: Seeking Truth Through Diverse Perspectives Editorial

cartoons have played an important role in American history, and have been an

integral part of newspaper opinion pages. But, as evidenced by several recent

firings, newspapers are killing editorial cartoons. If the fate of editorial

cartoons is tied to newspapers, they are doomed. For the past few months, Counterpoint, an email newsletter, has been quietly testing this new approach to distributing editorial cartoons. We are more than just a roundup of recycled editorial cartoons from syndication; Counterpoint pays for original content. When we publish our newsletter, these are a collection of cartoons that haven’t been seen anywhere else. We're the world's first cartoon-led news media company, pioneered by the most talented and thought-provoking political cartoonists. We bring you strong opinions from the Left and the Right. One thing we never do is play it safe. At Counterpoint, we feel it is neither possible nor desirable to be completely objective in discussing the news. To be human, is to have a point of view. Some news sources are more biased than others, but the problem is no one admits it. By showing multiple viewpoints on the news, with a deliberate attempt toward ideological balance, we hope to create more meaningful discourse. Our goal with this newsletter is to seek truth through diverse perspectives. Subscribe to Counterpoint at news.yourcounterpoint.com

RCH again: Counterpoint is the profession’s response to the drying up of editorial cartooning at the platform that nourished it for decades—the daily newspapers. If newspapers are going to stop publishing cartoons and all become the New York Times, then editoonists must fend for themselves, and Counterpoint is the first shout-out of the coming revolution. DON’T MISS OUT: Subscribe to Counterpoint at news.yourcounterpoint.com It’s a free subscription, by the way. The accompanying illustrative material, four cartoons from a recent posting of Counterpoint, include three of a liberal persuasion but only one, the 4-panel census survey, a likely conservative perspective. Not a bad breakdown: most editoonists in this country are liberal; only a few are conservative. But the conservatives get better exposure at Jewish World Review, blj@jewishworldreview.com, which runs a daily round-up of mostly right-leaning or moderate cartoons. Naturally, being an old gaffer, I favor the liberals, and I think the three on display here are wonderfully brilliant. We’ll be bringing more from this site in future, and maybe we’ll see something brilliant from the right. Who knows?

THE MUELLER REPORT GRAPHIC NOVEL HuffPost reports that IDW Publishing will produce a graphic novel version of the Mueller Report next April. Justin Eisinger, who’s editing the book, believes comic illustrations are the key to drawing more eyeballs to the report’s findings. “This really is the easiest way to get people to actually read it,” he told HuffPost.

Wheeler promises a combination of factual information (there will be footnotes referencing the report throughout the book) and a lot of real-life hilarity. “The part of the report where Trump learns about the investigation and freaks out, saying ‘I’m fucked!’ It makes me laugh every time,” Wheeler told HuffPost.

DC AXES VERTIGO DC Comics has announced that, starting in January 2020, it will close the DC Vertigo, DC Zoom and DC Ink imprints in favor of a new publishing strategy to release all published content under the DC brand. At the same time, reports Graeme McMillan at Hollywood Reporter, a new age-specific labeling system will be introduced for DC content, identifying content aimed at pre-teen readers, general audiences and material aimed at readers 17 and older. The three labels will be named DC Kids, focusing on readers aged 8-12; DC, for readers 13 and older; and DC Black Label, for content appropriate for readers 17 and above. The latter label repurposes the name created last year for DC’s out-of-continuity boutique line, and will include material already announced for that line. Material already announced with a 2020 or later date for DC Zoom and DC Ink will be assigned to the new appropriate labels, with ongoing series currently under the DC Vertigo imprint being assigned the DC Black Label rating. “We’re returning to a singular presentation of the DC brand that was present throughout most of our history until 1993, when we launched Vertigo to provide an outlet for edgier material,” DC publisher Dan DiDio said in a statement about the change. “That kind of material is now mainstream across all genres, so we thought it was the right time to bring greater clarity to the DC brand and reinforce our commitment to storytelling for all of our fans in every age group. This new system will replace the age ratings we currently use on our material.”

James Whitbrook at io9.gismodo.com wasn’t happy with the DC decision to kill of the imprint created in 1993 by Karen Berger, who carefully nurtured it since (in italics)—: Highlighting stories that could tell adult-focused tales featuring explicit content, Vertigo quickly established itself as an interesting imprint where creators—names like Neil Gaiman, Brian K. Vaughan, Warren Ellis, Grant Morrison, and many more, who all crucially would retain ownership rights over their Vertigo titles, something recent incarnations of the imprint moved away from—could experiment without many of the limitations they would’ve faced working within the confines of the main DC Comics line. Across the ‘90s and into the early 2000s, Vertigo became home to comics icons like Fables, Transmetropolitan, Sandman, Preacher, Y: The Last Man, and many more, several of which have gone on to find further success in adaptations, including iZombie, Lucifer, and Constantine, all the way up to the upcoming adaptation of crime thriller The Kitchen, itself under the DC Vertigo brand. Vertigo’s end is a sad moment for DC and for the comics industry at large. Its contributions to the field and its cultivation of creator-driven stories have left an indelible mark on comics. Although there are now spaces to tell the kinds of stories Vertigo was launched for, not just at DC, but at a swathe of publishers big and small—including at Karen Berger’s own current imprint, Berger Books, at Dark Horse—Vertigo’s early championing of weird, gritty, subversive storytelling helped push the world of comics into bold new places.

KEEPING PROMISES We caught a glimpse last time of Dororthy McGreal’s pioneering magazine The World of Comic Art: The Historical Journal of Comic Art and Caricature, and we promised a more detailed examination of its contents “next time.” “Next time” turned out to be in the most recent Harv’s Hindsight (June 23), a more appropriate place, we ultimately realized, because looking at her magazine was more like watching history than recording current events. And Harv’s Hindsight is our history department. So that’s where we’ve fulfilled that promise (as you doubtless noticed: being an attentive $ubscriber, you’ve already read it, right?). And we’ll have more about McGreal and her landmark publication next time, in Opus 395. Watch for it.

ANOTHER ANNIVERSARY Coincidentally, another distinguished publication is celebrating its anniversary just about now: it’s the Silver Anniversary (25th year) for Illustrators magazine. And to celebrate, the editors have rounded up a bunch of illustrators known for their pin-up caliber art: Milo Manara (38 pages of lissome lasses), Greg Hildebrandt (22 pages), Art Frahm (15 pages), and Margaret Brundage (13 pages). Being something of a connoisseur of such things, I’ve picked some representative pictures to post here by way of reviewing the book. Since you, if you are a feckless male of any distinction, doubtless can recognize in an instant the work of any of the afore-named, I’ll let you do the ID-ing; have at it.

ODDS & ADDENDA The planned Black Adam movie starring Dwayne Johnson was announced a few years ago, but has since languished in the development stage. Following the success of “Shazam!,” reports Scoop, New Line Cinema and Warner Bros. are moving forward with the project. Johnson was initially going to appear as Black Adam in “Shazam!,” but plans changed to instead give Black Adam his own stand-alone movie. Funny: doesn’t anyone remember that Black Adam was a villain in Fawcett’s Captain Marvel comicbooks? Red Sonja artist Frank Throne celebrated his 89th birthday on June 16, 2019. ... Feetnoot. Here are some of photos we inadvertently left out of Opus 393's report on the National Cartoonists Society’s Fest at Huntington Beach, California—just to prove everyone had fun there.

And while we’re at it, posting pictures I like, here’s my decoration of the cover of Detective No.1000, the blank version of which a friend asked me to deface.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. We’d be lost here at Rancid Raves without Rhode’s excellent hard work. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Leonardo da Vinci, the Italian genius who may have invented the Renaissance, created two of the most famous paintings in the history of art—“Mona Lisa” and “The Last Supper”—but did very few more. We may say, generously, that he “touched” around 17 paintings (many of the others attributed to him were actually done by his assistants). Less generously but more certainly, he completed about a dozen. With absolute certainty, he did six, including the two most famous.

DENVER POP CULT CON A New Name but the Fascinating Folderol WE EXHIBITED at the 8th Denver Comic Con May 31 - June 2. And so did about 120,000 other people. The convention is pretty much the same game under its new name, the Denver Popular Culture Con, as it has been for the previous seven years. Except, maybe, more authors and crafters than before. Comic books are still a presence, but funnybooks have never been more than a side-show in the big tent. The name change was prompted by the San Diego Comic-Con’s successful law suit against the Salt Lake City Comic Con: Salt Lake City had to pay San Diego thousands in damages and can no longer use the term “Comic Con” in its name. I doubt that San Diego would come after Denver for using Comic Con in its name—just as I doubt that the dozens of comic cons across the country need to fear legal action. The term long ago came into common parlance. The Salt Lake City people, however, made what appeared to be deliberate attempts to confuse fans into thinking that the Salt Lake City iteration was somehow linked to San Diego—and thereby to enhance Utah’s attendance. And that’s what the suit was about. (As I recall without having any solid documentary evidence to support my recollection.) The name change in Denver had been in the hopper for some time. The con is sponsored by a non-profit educational operation, Pop Culture Classroom—which changed its name in 2014 from Comic Book Classroom, shifting the attention from funnybooks to popular culture. The change in the convention’s official name is a parallel change. Pop Culture Classroom runs workshops in schools throughout the Denver metropolitan area. And next fall, it will launch another pop cult con in Reno. The pop cult weekend in Denver consisted of 600 hours of formal programming (workshops, panel presentations) and a million square feet of exhibit space in the Denver Convention Center, which embraced a lot of open space for fans to line-up in for autographs by comics and entertainment celebrities. The program booklet ran to 74 pages, listing guests and describing panel presentations. Unhappily, the descriptions weren’t keyed to time and place, so enthusiastic potential attendees had to scour schedules for panel titles to find the ones they’d decided to attend. Phooey: bad implementation. Our table was in what the Con calls “Artist Valley,” nodding at the locale next to Colorado’s mountains (and valleys). “Merchandise Mesa” makes a similar gesture for the section of the exhibit hall devoted to booths rather than tabletops. Cosplaying (no nudity or near nudity) was in evidence all three days but particularly on Saturday, the best day for numbers. The aisles were full of the milling throng all day. But they weren’t as crammed as the San Diego Comic-Con’s aisles—even though Denver claims a similar attendance, 115,000. The two cons undoubtedly have two different ways of counting. In terms of soulless business transactions, my books and goods sold well, record-breaking sales. And now, some photos of the weekend: the story of any convention is better told in pictures than in words, and we therefore surrender to the inevitable.

EXHIBITING AT FREE COMIC BOOK DAY I don’t always attend FCBD, but this year, I went to my favorite comics shop as an exhibitor, holding forth at a table next to Denver’s hardest working cartoonist, Stan Yan, whose current best-selling endeavor is making zombie caricatures: he caricatures whoever buys in and adds to the caricature the usual zombie accountrements—rotting flesh, falling-out eyeballs, crooked teeth. It was a fun day, watching people pass by en route to glomming up free funnybooks from the long display tables near us. Here are some photos.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

JUDGING FROM THE FIRST ISSUE, Sham Comics consists entirely of stories from the 1940s and 1950s in which the original artwork has been reprinted but the speech balloons have been drastically rewritten to reflect an overweening preoccupation with female anatomy, sex, and violence, none of which would get by the censoring machinery of yore. It’s adolescent humor raised to the nth degree. The

characters include Bozo the Robot (drawn originally by George Brenner),

the Red Roid and Pooter (“pooter” derived from “fart,” and Pooter, Published by Source Point Press, the book also reprints Golden Age ads, and makes up some of its own. F’instance, using the celebrated Phanton Lady by Matt Baker on the cover of “Lingerie Lass,” it’s “Victoria’s got a Secret” that is selling future issues of the superheroine comic: “A secret identity—that is, by day, she’s a glamorous negligee model, but by night, she fights crime, in her undies! She’s Lingerie Lass!” You have to see it to believe it, so we finish with a few instructive illustrations.

I

HAVEN’T BEEN KEEPING UP with Deadly Class, and it got up to No.37 (March

2019) before I looked in. Attracted by the drawing, I bought a copy.

THUMBS, Part One of

Five (June 2019), is another title the drawing of which seems much better than

the story although it’s hard to tell from the first issue even though it goes

about twice as long as a regular book (price, $4.99 if that’s any clue). Sean

Lewis’ story, if you want to call it that, is mostly the The young woman, Nia, and her boyfriend, Thumbs—a couple of lower-income kids—have been raised, more or less, by an A.I. babysitter, which is secretly training the kids to be a private army. I got that off the back cover. The insides aren’t so straight-forward. Completed episodes don’t work: attractive as the art is, it’s stylized to the extent that characters aren’t clearly delineated, so it’s difficult to link episodes to characters, which is one of the functions of episodes—to reveal personalities of the principals. Since I don’t get to know the characters very well, the book doesn’t grab me. Whatever cliff-hanger there is, isn’t enough to bring me back.

DOOMSDAY CLOCK keeps ticking right along, making no more sense in Nos.7 - 10 than it has in Nos.1 - 6. The only strand of continuity threaded through the books is still here, and there. Veidt, known by the supermonicker as Ozymandias, in No.7 is trying to find Dr. Manhattan (the big, naked blue guy from Alan Moore’s classic, which DC denies by not including any mention of Watchmen in this series) because he thinks only Manhattan can save the earth (which Veidt almost destroyed). Along the way, we encounter various of the DC Universe’s superheroes and superheroines who seem to have no function but to be the villains that governments are hunting to eliminate (because it is suspected that the superfolks are plotting some sort of take-over?). That’s it. In No.7, Dr. Manhattan shows up but declines to help Veidt. Batman also returns to the story, fights the Marionette to a draw. Also present are the Joker and the Comedian, who’s tied up by the Joker. The Marionette is pregnant. Again. So what happened to her first born? Dunno. Rorschach kills the Joker and then takes his mask off (signaling his retirement?), and Veidt announces that he doesn’t have cancer after all. If you think this is a fragmented recap thus far, try reading the books. No.8 begins in the offices of the Daily Planet with Lois Lane and Clark Kent, who are sent to Moscow to report on happenings there. In Moscow, a character named Firestorm, who is actually a meld to two persons—a smart professor and a less gifted teenager—sets up enough fire that he turns several dozen people into glass. Putin in Russia declares war on the U.S., and Superman shows up to try to talk him out of it. Russian heroes attack Superman and Firestorm, and Superman comes to Firestorm’s aid because he knows Firestorm, properly inspired, can return the glass people to real life. Because he has taken a side as far as the Russians are concerned, he forfeits his usual neutrality. He is now the enemy. The glass people are destroyed before Firestorm can act. In No.9, Manhattan takes up the narrative, and most of the issue is devoted to his murmerings and fantastical sf encounters with members of the Justice League. Manhattan always comes out on top—even when it looks as if he’s been disintegrated. Superman and Batman are both injured with Firestorm detonates. Then Lex Luther arrives to “help” Lois as she ministers to and grieves over Superman. The confusion does not let up a bit in No.10. In fact, it gets even worse because writer Geof Johns introduces Time changes, back and forth, past, present, and future. We didn’t know much about what was going on before, and now we know even less. Probably if I realized that two DC universes are involved, I’d know better what’s happening; but I don’t, so confusion reigns. This issue is mostly about a movie star named Carver Coleman, whom Manhattan seems to have befriended and helped to stardom. Or is it to death?

The issue is entirely off-narrative. You can read the whole issue and never find out who Veidt is or what his plans are. (We left him dangling at theend of No.8.) Gary Frank’s art is still splendid—inspired even. I just hope Johns’ story, however it turns out, is worth all Frank’s brilliant labor. Although now, with only two issues to go, it will take a resolution of superhuman convolution to resolve all the issues and tie up the unraveled ends. Put me down as a doubter.

QUOTES & MOTS From Curmudgeon—: “Age is a very high price to pay for maturity.”—Tom Stoppard “You know you’re old when your walker has a an air bag—and they’ve discontinued your blood type.”—Phillis Diller “True terror is to wake up one morning and discover that your high school class is running the country.”—Kurt Vonnegut “When I turned two, I was really anxious because I’d doubled my age in a year. I thought, ‘If this keeps up, by the time I’m six, I’ll be ninety.”—Steven Wright

TRUMPERIES More Ego Antics from the Blowhard in Chief “Since his inauguration,” writes Dana Milbank in the Washington Post, “Trump has compiled a ‘woeful record’ of cruelty, incompetence, fraudulence, greed, racism, criminality, vulgarity, and buffoonery. Trump is hoping his supporters don’t notice this record amid all the shouting.” Trump is unlike any other politician we have experienced. He is, in fact, not a politician at all. He’s a folk hero. Like Paul Bunyon or Pecos Bill, he obeys his own laws and instincts and ignores ours—as any good folk hero does. It does no good to criticize him for his outlandishness, his absurdities, his rudeness and crudeness, his constant lying (which he does as the rest of us breathe) or any of his other so-called faults. These are the stuff of folk heroism, and as a folk hero, he embodies them. The Trumpet glories in his appearances on the cover of Time magazine, a respectable, professional news medium. So he was undoubtedly ecstatic when Time put him on its July Fourth cover just in time to help him become July Fourth, the nation’s foremost holiday. And it was a Presidential Portrait anyone, even Bronco Bama, would envy: it was an actual photograph, taken in the Oval Office, with the Trumpet sitting on his desk looking serious and foreboding, the president pout firmly in place. We’ve posted that image nearby—along with some less flattering but also true image of the Trumpet on magazine covers. Enjoy.

And—as a Blowhard Bonus, we’ve added a portrait culled from the pages of The American Bystander (from which we have even more samples towards the end of this exposition).

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy APART FROM AN ASIDE ON D-DAY CELEBRATIONS, we’ll postpone our usual foray into political cartooning for a couple of weeks. We’ve simply piled up too much Vital Information in this opus; a full-blown Editoonery would be more than too much. Instead of editoons this time, we have the voracious report on the New York Times’ gaffe in giving up cartoons it never published anyhow. That tale we’ll tell right after showing how editoonists treated the anniversary of D-Day.

THE 75TH ANNIVERSARY of the Allied invasion of Hitler’s Europe on June 6 produced its share of blubbering speeches characterizing the deaths of thousands as “sacrifices” made by “heroes.” We’ve fallen of late into calling anyone who dies in the service of his country or community a “hero.” Mostly, this is nonsense. And it’s particularly gratuitous nonsense with respect to D-Day and those who died on the beaches of Normandy. There were universally no heroes. Not a hoagie among them. A hero is someone who does something apart, something the rest of his peers did not do. Those who died on the beaches that legendary day did so by the thousands. Most of the Americans who invaded on D-Day were draftees. True, some had volunteered for military service following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor two-and-a-half years earlier. But most were draftees. They were conscripted by their government, which gave them little choice: serve in the army or serve time in jail. Or some such equally abhorrent choice. And they were drafted by the millions. No heroics. No single soldier stand-outs. All were alike; few were volunteers. What’s heroic about being one in millions? Nothing. Do they deserve our respect? Yes, undoubtedly, absolutely. For what? For following orders. They followed orders even though they knew they might die. They weren’t guessing: they knew. They didn’t run away. They might’ve felt like running away, but they didn’t. They didn’t want to let their compatriots down— their fellow soldiers in their unit, their buddies. They were all together in this. They acted in mutual defense and aggression. There was a selflessness about it. But nothing heroic. We don’t have a good word for what they did. But we remember and fiercely, proudly, respect them because they did what they were supposed to do. No shirkers.

CELEBRATING D-DAY generally involves a sparse list of possibilities: you show the troops in landing craft, looking ahead to the beach before them; you have a helmet of some deceased warrior atop his rifle, jammed into the sand bayonet first; tombstones; veteran survivors on crutches. The ones we’ve selected for remembering the 75th anniversary are those that vary from the customary a little. Dave Granlund shows the troops charging out of their landing craft, but in the distance we see the crosses that will mark the graves of many of them. Below that a signature I can’t read varies the helmet on the beach dramatically: in its shadow, some shore bird has laid her eggs, a hopeful sign of the future. Below that, Michael Streeter gives the helmet on the upright rifle a headline that can be read two ways, both truthfully, and a little poignantly. At the upper right, Streeter is back again, with a little girl whose flower remembers that only a few of the survivors are still alive at the 75th festivities. And then, there’s Snoopy. Some might consider having a cartoon dog in such solemn situation is a kind of sacrilege. But Charles “Sparky” Schulz, Snoopy’s creator, was a veteran of World War II in Europe, and in the decade before he died, he started celebrating D-Day with Snoopy. And he had fans galore. One of them complained in 1996 that he couldn’t find a single reference to D-Day on June 6 that year—with one exception. It was Snoopy, bravely dog-paddling toward Normandy Beach. The vet in question and “others undoubtedly felt affronted by the oversight,” wrote Blake Scott Ball at the Washington Post. “For those who had served and their loved ones, who felt like the sacrifices of that day and month had been forgotten over time, Schulz’s strip was salve on the wound.” Schulz knew about that. “We have a tendency to forget very quickly the sacrifices that others have made for us,” he told a reporter. He wanted to do his part to combat that tendency and to connect Americans with his call to remembrance and national unity.

Taking Up Where We Left Off Several Hundred Words Ago CARTOONLESS TIMES GIVES UP CARTOONS And the Editooning World Goes Bonkers Editoonist Patrick Chappette was the first to react to the Times announcement that it was giving up on editorial cartoons: on June 10 at his blog, he traced his career as a crusade to get the Times to publish editorial cartoons: “In 1995, at twenty-something, I moved to New York with a crazy dream: I would convince the New York Times to have political cartoons. An art director told me: “We never had political cartoons and we will never have any. “But I was stubborn. For years, I did illustrations for Times’ Opinion and Book Review, then I persuaded the Paris-based International Herald Tribune (a NYT-Washington Post joint venture) to hire an in-house editorial cartoonist. By 2013, when the NYT had fully incorporated the IHT, there I was— featured on the NYT website, on its social media and in its international print editions. In 2018, we started translating my cartoons on the NYT Chinese and Spanish websites. The Times domestic edition remained the last frontier. “[With the door shut in my face,] I had come back through the window. And had proven that art director wrong: the New York Times did have in-house political cartoons. For a while in history, they dared.” Then came the anti-Semitic cartoon of April 25. Chappette continues: “In April 2019, a Netanyahu caricature from syndication reprinted in the international editions triggered widespread outrage, a Times apology and the termination of syndicated cartoons. Last week, my employers told me they'll be ending in-house political cartoons as well by July. ... “I’m afraid this is not just about cartoons, but about journalism and opinion in general. We are in a world where moralistic mobs gather on social media and rise like a storm, falling upon newsrooms in an overwhelming blow. This requires immediate counter-measures by publishers, leaving no room for ponderation or meaningful discussions. Twitter is a place for furor, not debate. The most outraged voices tend to define the conversation, and the angry crowd follows in. “Over the last years, I have consistently warned about the dangers of those sudden (and often organized) backlashes that carry everything in their path. If cartoons are a prime target it’s because of their nature and exposure: they are an encapsulated opinion, a visual shortcut with an unmatched capacity to touch the mind. That’s their strength, and their vulnerability. They might also be an [indication] of something deeper. More than often, the real target, behind the offending cartoon, is the media that published it. “Along with The Economist (featuring the excellent KAL), the New York Times was one of the last venues for international political cartooning. For a U.S. newspaper aiming to have a meaningful impact worldwide, it made sense. Cartoons can jump over borders. Who will show the emperor Erdogan that he has no clothes, when Turkish cartoonists can’t do it ? (One of them, our friend Musa Kart, is now in jail [see Opus 392A].) Cartoonists from Venezuela, Nicaragua and Russia were forced into exile. Over the last years, some of the very best cartoonists in the U.S., like Nick Anderson and Rob Rogers, lost their positions because their publishers found their work too critical of Trump. Maybe we should start worrying. And pushing back. Political cartoons were born with democracy. And they are challenged when freedom is. “Curiously, I remain positive. This is the era of images. In a world of short attention span, their power has never been so big. Out there is a whole world of possibilities, not only in editorial cartooning, still or animated, but also in new fields like on-stage illustrated presentations and long-form comics reportage— of which I have been a proponent for the last 25 years. ... It’s also a time where the media need to renew themselves and reach out to new audiences. And stop being afraid of the angry mob. In the insane world we live in, the art of the visual commentary is needed more than ever. And so is humor.”

“I THINK THE MESSAGE that’s being sent is that they’re spineless and really can’t take the heat,” Matt Wuerker told The Daily Beast. “This whole episode started out with the anti-Semitic cartoon that slipped through their editorial side and created that shit storm. I find the whole thing kind of tragic and a little bit pathetic.” Speaking to the larger landscape, Wuerker, the Pulitzer-winning cartoonist for Politico, said: “The collapsing space for political cartoons and satirical commentary because editors don’t have the spine to stand up to social-media outrage campaigns is bad for free speech, and bad because political debate benefits from a little humor now and again." Taking a similar view on the bigger issue is Daryl Cagle, head of the syndicate Cagle Cartoons, which distributes Chappatte’s work to about 800 subscribing clients. “By

choosing not to print editorial cartoons in the future, the Times can be

sure that their editors will never again make a poor cartoon choice,” Cagle

said. “Editors at the Times have also made poor choices of words in the

past. I would suggest that the Times should also choose not to print

words in the future — just to be on the safe side.” John Adcock, who cartoons in the United Kingdom for the Independent, may be a long way away, but he sees clearly: “The paper has said the offending cartoon was published due to a weak editorial process. The fear is that the threat of greater online outrage in the future encouraged them to think the only solution was to remove the process altogether. Taking the path of least resistance and giving in to those voices means damaging this unique form of journalism and therefore damaging free speech, a pillar of our democracy. “Political cartooning,” he continued, “has always been a difficult and precarious way to make a living and most cartoonists will be aware of the ups and downs of pursuing this unusual career. But when a cartoonist’s position is cut due to editorial timidity or simply a lack of understanding of the power and importance of this art form, then it’s a sad day for anyone who gives a damn about holding the powerful to account.” “Exactly,” Chappette agreed. “And this sends a signal discarding a whole genre that is so rooted in the history and tradition of democracy. And imagine how this must be felt by cartoonists who directly suffered the consequences of exercising the right of satire, like Musa Kart, colleague from Turkey who's now in jail, or Rayma Suprani from Venezuela, or Pedro Molina from Nicaragua— cartoonists who were forced into exile— and many others. “But I'm still very positive about the genre,” Chappette went on. “In this world of short attention span, the power of images has never been so big. And it's also a time when the media need to renew themselves.” He concluded: “But we must stop being afraid of offended people because the whole controversy that was triggered a month ago by that cartoon, I think it should have encouraged a discussion, explaining why this cartoon was wrong, how it's run, what is cartooning, and there was no space for that. I think the New York Times had to deal with a huge storm triggered by social media. We need to be able to withstand this and to go back to putting things into perspective.”

WRITING FOR the Board of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, AAEC president Kevin Siers said: This time the "failing New York Times" really is failing, big time. Editorial cartoonists across America and the world have consistently, uniformly and vigorously defended the ideal of a free press from the attacks of tyrants, dictators and twittering demagogues. But now cartoonists are united in their outrage as it has become apparent this week that the New York Times has indeed sadly failed. Monday, the Times announced it would no longer publish in-house editorial cartoons in its editions, ending their regular publication of the work of internationally acclaimed cartoonist Patrick Chappatte. This decision comes weeks after the Times was burned by their own editorial negligence in running a syndicated cartoon that was widely condemned as being anti-Semitic. Doubling down on this clumsiness in response to the resultant furor, the Times announced that they would no longer run syndicated editorial cartoons. Their decision now to not run in-house cartoons as well only adds to that ham-handedness, blaming the medium of cartoons for what resulted from their own lack of editorial oversight. In a statement defending their action, the Times said they “plan to continue investing in forms of Opinion journalism, including visual journalism, that express nuance, complexity and strong voice …” From this description, it seems the type of “visual journalism” the Times envisions has more to do with storytelling than with expressing strong opinions. The best editorial cartoons are not celebrated for their nuance. It is their clarity and pointedness, the sharpness of their satire, that make them such powerful vehicles for expressing opinion. There is no “on the other hand” in an editorial cartoon. This power, understandably, makes editors nervous, but to completely discontinue their use is letting anxiety slide into cowardice. With their decision to end using editorial cartoons, the Gray Lady, as the Times has been called, has become even more gray and dingy. And the environment for free expression and the free exchange of ideas has become even more bleak.

OTHER ORGANIZATIONS CHIMED IN. From the National Cartoonists Society’s president Jason Chatfield, we have this: “On behalf of the membership of the National Cartoonists Society, the NCS board express our great dismay at the decision to cease running daily editorial cartoons in all international editions of the New York Times as of July 1 as they have also done for the domestic edition.” Pointing to the long history of editorial cartooning as “an invaluable form of pointed critique,” Chatfield continued. “The cartoonists that contribute to your publication are not mere hobbyists, but deeply committed life-long devotees to the art of political commentary. It is not a job that is taken lightly, nor done with ease. It is a passion that not only feeds the national and international conversation, but just as importantly, feeds their families. ... “We find ourselves in a critical time in history when political insight is needed more than ever, yet we see more and more cartoonists vanishing from the pages of our publications. If we are to dull the voices of our most valued critics, satirists, and artists, we stand to lose much more than the ability to debate and converse: we lose our ability to grow as a society. We rob future generations of their opportunity to learn from our mistakes.” Chatfield concluded by imploring the Times to reconsider and to reinstate editorial cartoons “to both the domestic and international editions of the New York Times in print and online.” Chief executive officer of PEN America (Poets, Essayists and Novelists) Suzanne Nossel released a statement, hoping the Times would reconsider and adding—: “Free speech and open discourse demands an understanding that mistakes and offenses will occur, and a determination that these not be answered by shutting down expression to avert future lapses. ... If outlets like the New York Times retreat from this uniquely potent form of political commentary, it may hasten the death of a form that has contributed immensely to our political conversation over time. The possibility of offense must not be reason to shut down valued channels of speech. As a leader in media, the New York Times can get this right and help us to see how cartoons can continue to provide insight and inspiration amid our shared global commitment to eradicating bigotry. “PEN America has been a staunch defender of cartoonists, including after the murders of 12 staff of the Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris in 2015, and sought to foster dialogue about how to keep open space for satire while acknowledging and addressing the serious harms bigotry can inflict. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect open expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible.”

THE

WEEK magazine

publishes a weekly round-up of editorial cartoons and its cover of every issue

is always a full-color, painted editorial cartoon. The incident at the Times is only the latest reason to feel concern about the state of political cartoons in this country. Once a deeply-ingrained part of American journalism, there were some 2,000 working editorial cartoonists at the start of the 20th century. In a 2012 special report by the Herb Block Foundation (named for the legendary cartoonist who coined the term "McCarthyism"), fewer than 40 staff cartoonists were found to be employed by U.S. newspapers, a number that is no doubt smaller today. [These numbers, often summoned up as knee-jerk reaction to whatever threatens the profession of editorial cartooning, are most probably exaggerated; we’ll explain at the end of the New York Times disquisition.] Editorial cartoons' courting of controversy is often a positive and democratizing force, one that rightfully makes people in power squirm by casting motives into sharp relief. It can also come at great risk to the artists: most famously, 12 people were killed in 2015 when terrorists opened fire on the newsroom of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, ostensibly over the paper's cartoonish depiction of Muhammad. This can come with a negative side too, as it's not totally uncommon for hateful images to make it into print in the guise of political cartoons: The unnecessary anti-Semitic depiction of Netanyahu is one of a few recent examples, including a "racist" depiction of Serena Williams that was recently published in Australia, and a New York Times editorial animation of Trump and Putin was widely criticized as homophobic by critics. Still, such mistakes, while deeply regrettable, should not cloud the important work that many other cartoonists do. A truly great editorial cartoon, rather, should be the knife-twist of accountability. While reported articles keep the powers that be in check, and opinion and editorial sections help readers make sense of that reporting, editorial cartoons are the jolt that shocks you into caring. Many people find them so vital to the journalistic process that there are calls to put them on the front page [where editorial cartoons once reigned in almost every paper]. To

lose them, then, is to lose one of the most powerful wakeup calls we have

available to us as readers. Where would we be without Robert Minor's succinct

anti-war illustration of a headless man, declared by an army medical examiner

to "at last" be "a perfect soldier?" It

really should be the golden age of political cartoons, too. Not just because of