|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 393 (June 7, 2019). And now—fanfare, bugles,

drums and dervishes— the Grand Finale of our celebration of having completed

20 years of We began our celebration almost a month ago with the posting of another video starring our favorite reporter, Yrs Trly, and we continued with a special Hindsight featuring the history of Cartoons Magazine, accompanied, as usual, by a profusion of illustrative material. All of which—in addition to our routine posting of R&R (which, in May, took two installments to top off). And now, as I said, the Grand Finale of the revelry, this posting of Opus 393, which includes the usual casserole of news (among which, the annual Reubens award weekend of the National Cartoonists Society) and reviews (of editoons and more) plus special 20-year anniversary features, to wit—:

BUT MOST IMPORTANT, we have a Once In A Lifetime pictorial tour of the Rancid Raves Homestead and Sweat Shop, the Study and the Studio where All the Damage is Done.

Before we leap two-footed into the fray, we’ll pause a moment to survey landscape so you can pick and choose what to read and what to slide by. To make it easier for you to wade through all this plethora and pick just what you want to read, we’ve listed everything that’s here, in order, by department, as follows (articles with asterisks * are the long ones)—:

NOUS R US Two More Editoonists Laid Off NCS Award Winners *NCS Seaside: A Festival Al Roker’s Secret Life As a Cartoonist Last Beetle Alcaraz Consults

Odds & Addenda Illustrators Mag Is 25

*SIXTY YEARS AGO And How My Dream Has Come True An Anniversary Celebration Special

FAMOUS TOUR OF RANCID RAVES Photographic Expedition through the RR Galaxy Another Anniversary Celebration Special

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Re-running A Brilliant Analysis by Bob Hall Yet Another Anniversary Special

TRUMPERIES The Outlandish Antics of Our Prez

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

*SILVERSTEIN AMONG THE GIVERS AND TAKERS In Honor of Rancid Raves’ 20th Year Anniversary Re-running Our Obit for the Most Eccentric and Talented Cartoonist of His Day

BOOK REVIEW Another Re-run in Honor of Rancid Raves’ 20th Year Anniversary—: Reviewing A Boy Named Shel

IRKS & CROTCHETS The Bible Won’t Object to Same Sex Marriage

A-GAGGING WE SHALL GO New Sites for Gag Cartoons And Seeing Some Odd but Good Ones COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Jefferson Machamer Revisited

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

TWO MORE EDITOONISTS BITE THE DUST Eraser Crumbs Hereafter Nate Beeler, editoonist for the Columbus

Dispatch for the past seven years, and Rick McKee, a 30-year veteran

at the Augusta Chronicle (21 as staff editorial cartoonist), were let go

on May 23 as part of a sweeping nation-wide cost-cutting measure by GateHouse

Media. GateHouse, one of the largest newspaper publishers in the U.S., owns 156

daily newspapers, mostly in smaller towns, and 328 weeklies, and it reportedly

cut staff by 99 editors, reporters, photographers, and other newsroom

employees, as reported by Andrew Pantazi, a journalist who is maintaining a

spreadsheet keeping track of layoffs. More layoffs are expected. A likely cause for the cuts: GateHouse’s parent company, New Media Investment, reported a loss of $9.4 million in the first quarter despite its revenues being up 13 percent. Mike Reed, CEO of New Media, tried to downplay the news, calling the layoffs “immaterial.” “We’re doing a small restructuring,” he said, “—at least that’s what I would call it. ... We have 11,000 employees. This involves a couple hundred.” He claimed most of the reported layoffs would be asked to change roles in the company and that the actual number of layoffs only affect “more like 10 people.” But nearly 100 people were online claiming they’d been cut. Earlier this year, GateHouse committed at least 60 other layoffs across the country. With its cuts this month, GateHouse joins another chain owner, Gannett, in reducing staff. Among local newspapers, GateHouse has built a reputation for quickly acquiring local properties, gutting staff, and then combining regional newsrooms to reduce costs. Ditto, as I understand it, Gannett. And these owners are not the only ones. When newspapers sold out to share holders, they opened themselves up to being treated as profit-producing factories, not news organs, and when profits sag, expenses are quickly cut. And staff salaires represent a large portion of the cost of running a newspaper. With the disappearance of Beeler and McKee, the number of full-time staff editorial cartoonists in this country drops to 43, a drop of 57% since 2008 when there were 101. McKee, a popular syndicated editoonist with Cagle Cartoons, said his stint of three decades, 21 drawing editoons, was his “dream job, and I have been extremely fortunate to have been able to do it for as long as I have.” His last day will be July 19. “So you will still see cartoons from me for a while,” he said. “After that, who knows what the future holds?” Apart from the personal and financial pain these two layoffs cause, for the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, cutting Beeler will affect the AAEC convention next fall when it meets in Columbus, where Beeler and the Columbus Dispatch were hosts for the event. Before joining the Dispatch, Beeler worked for another 7 years for the Washington Examiner. Incidently, by a vote of 33 million to 11 million, New Media shareholders rejected a compensation plan for the GateHouse CEO, thereby confirming greed as the basic motivating force in capitalism. But we knew that, eh?

BARGAIN GORDO BOOK Bud Plant, in his summer Incredible Catalog of Comics, Art & Illustration, offers a “warehouse find” of my Accidental Ambassador Gordo, the life and art of Gus Arriola. “Warehouse find” means they found a box of the books that had been mislaid for a couple years. The ones they found are accompanied by a bookplate signed by me and Gus (signed before his death), which doubtless justifies the price—$75. You can buy the same book here—without the bookplate and Gus’s signature but with my signature—for less than half that, merely $30, including p&h.

NCS AWARDS At its 73rd annual meeting May 17-19, the National Cartoonists Society distinguished itself by giving the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award to Disney Legend Floyd Norman, a man whose life and work lend class to the Society. An hour later, NCS disgraced itself by giving the Reuben trophy to the man it named Cartoonist of the Year, Stephen Pastis, a man who cannot draw. Cartoonist of the year and he can’t draw! Pastis’s daily strip, Pearls Before Swine, proclaims with its name its creator’s disdain for his readers and then heaps contempt upon scorn by resorting to stick figures to tell his jokes. Pastis is the Susan Lucci of NCS: he has been nominated for the Reuben every year since 2009 (or nearly every year—enough for the Lucci Award). But he can’t—or doesn’t—draw. And yet NCS chooses to honor him by calling him Cartoonist of the Year. The final slap in the face of professional cartoonists. Pearls is funny, yes. And it’s in a lot of newspapers. But Pastis can’t draw. Surely the Cartoonist of the Year should be able to draw. In making such an award, NCS demonstrates to all and sundry that its awards aren’t worth much. They’re trivial and inconsequential. And we see this verdict again in all the other awards NCS confers, the “divisional” awards, the Rubes (as I call them), conferred upon cartoonists who labor in the other vineyards of cartooning—panel cartoons, comic strips, book illustration, advertising, and on and on. Fifteen Rubes were awarded during the Reuben Banquet. But only six of the fifteen winners thought the awards are consequential enough to come to the dinner. Only six out of fifteen were present to accept their Rubes. Not even half; just 40%. Last year, it was even worse; seen Opus 380. Four of the remaining nine sent film clips of them accepting their awards; two more were accepted by friends. Three of the winners weren’t present in any way. If this roundup doesn’t signify the profession’s disregard for NCS and its awards, I dunno what would. The Rubes of NCS. Here are the Rube winners—and the nominees since I believe that if the award is worth making, it’s worth listing those who were nominated as well as those who won. The six who were present are in bold face and are marked with an ornate asterisk, ❉ ; the winners who disdained to appear are marked with a black square, ■ ; those who weren’t there but accepted via film or a friendly stand-in get a diamond ◆. Editorial Cartoons —Clay Bennett, Michael Ramirez, ❉Rob Rogers; nice—Rogers, who lost his job last year in a conflict of interest with his publisher after 25 years (see Opus 381), got the formal recognition that presumably rubs his former employer’s nose in it Magazine/Newspaper Illustration — ◆Tom Bunk, Amy Kurzweil, Jim Woodring Feature Animation —Shiyoon Kim (character design) Peter Ramsay (director), ■ Justin K. Thompson (production design); all three for “Spider-Man into the Spider-Verse” Television Animation —“Castlevania” (Netflix), “Hilda” (Netflix), ■ “Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle” (Amazon Prime) Newspaper Panel Cartoons —❉Dave Blazek, Loose Parts; Mark Parisi, Off the Mark; Jerry Van Amerongen, Ballard Street; again, a nice nomination—Amerongen just retired, and had he received this, it’d be his second so he’d be going out in style; but he didn’t get it. Magazine Gag Cartoons —❉Joe Dator, Pia Guserra, Amy Hwang; all three, mostly in The New Yorker (where else? Well, there are some small trade journals, and some obscure cartoonists are still drawing and selling to such outlets—too obscure, alas, to attract the attention of NCS). Advertising/Product Illustration — ◆James Lyle, Luke McGarry, Johnny Sampson; Comic Books —Daniel Acuna, Black Panther; John Allison, Giant Days; ■Greg Smallwood,Vampironia; as usual, NCS overlooks most newssstand funnybooks, apparently in the mistaken belief that only off-beat efforts are worthy of an award—phooey; DC’s Man and Superman should have won. Others that demonstrated superior stories and storytelling were Batman White Knight, Kill Or Be Killed, and Cemetery Beach. To name a few. A few that apparently NCS members are too sophisticated to read, even. Sigh. Graphic Novels —Rick Geary, Chester & Grace: The Adirondack Murder;❉Peter Kuper, Kafkaesque; Brenna Thummler, Sheets; great—Geary and Kuper getting recognition at last Online Comics, Long Form —Vince Dorse, Untold Tales of Bigfoot; Tom Parkinson-Morgan, Kill Six Billion Demons; ◆Ota Yuko and Ananth Hirsh, Barbarous; Online Comics, Short Form —◆Dorothy Gambrell, Cat and Girl; Lonnie Millssap, Bacon; Zack Weinersmith, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal Greeting Cards— Scott Nickel, ❉Maria Scrivan, Dan Walsh Variety Entertainment— James Allen, Mark Trail; John Graziano, Ripley’s Believe It or Not; Bucky Jones; ◆Dave Klug; I have no idea what this category is supposed to include; comic strips are apparently fair game; also design of some sort? Who knows? Whatever’s left over after all the other Rubes? Newspaper Comic Strips—John Hambrock, The Brilliant Mind of Edison Lee; ❉Will Henry, Wallace the Brave; Mike Peters, Mother Goose and Grimm; the winning strip started syndication just a little over a year ago, and it already qualifies as a “best of the year” award? Well, I suppose. Best “new strip” maybe? Book Illustration —Genevieve Godbout, Mary Poppins; Ed Kaban, Even Superheroes Make Mistakes;◆Rafael Lopez, The Day You Begin; Online Animation —One of the new “divisionals,” this category didn’t receive enough qualifying submissions so there are no nominees; management vows to try again next year with better description of the division To see samples of the nominees’ work, visit reubens.org, the NCS website.

NCS SEASIDE As an old seagoing man, I was glad to see the ocean again. The experts in such matters would have us believe that exotic locations improve attendance at conventions held in such places. By that logic, this year’s Reubens Weekend at a California resort ought to have been attended by heaps more than usual. But it wasn’t. Total attendance was about what last year’s convening was—306 this year; 310 last year in Philadelphia, reputedly the dullest destination in the known universe. (It was the immortal W.C. Fields who said, “I once spent a year in Philadelphia. I think it was a Sunday.”) Of the total this year, 202 were members (last year, only 151); the rest (104 this year, 159 last year) were family members, friends or business associates (syndicate officials, f’instance). Held

at Huntington Beach, California, one of the world’s surfing capitals, this

year’s Reubens was wildly different than its predecessors. It was part of an

elaborate festival dubbed the NCSfest, a showy street fair celebrating

cartooning. That alone ought to have improved attendance; but it didn’t. The

usual NCS program—presentations by cartoonists, business meeting,

breakfasts—took place in the Huntington Beach Hyatt, a luxury class hotel; the

rest of the program transpired a couple miles away at downtown Huntington

Beach. The hotel offerings, dubbed Premium Events, were closed to all except

registered NCS members and anyone who bought a $50 weekend pass (or a daily

pass, $15/20). The HB events, most of the program, were open to everyone. At the hotel, NCS’s usual program of presentations was greatly expanded from the customary 4-6 a day to 12 on both Friday and Saturday. But the presentations overlapped so you could actually attend only about 4 or 5. Still, the programming was decidedly richer than in the past. Downtown,

Main Street, which culminates in the Pier stretching out into the Pacific, was

lined Saturday and Sunday with exhibit booths displaying various cartooning

wares on tables in roofed canvas huts. Fantagraphics had a booth, as did Cathy

Guisewite, Lalo Alcaraz, Peter Kuper, Joe Staton, Mad’s Tom Richmond,

Kevin Fagan, Cartoon Art Museum, Stuart Ng Books, and a couple dozen more. On Sunday afternoon, I had a booth that I shared with Tom Tanquary, the documentary filmmaker who enlisted me to help with a documentary on the history and influence of newspaper comic strips. My part in the creation of this film was to sit down with about 18 cartoonists in turn, plus a couple of historians, and engage each of them in conversation about cartooning and comic strips. In other words, I got to do what I most enjoy—talking about cartooning. Then Tom went through an estimated 2,100 minutes of film and culled out what suited his vision for a 90-minute documentary. A huge selection task. By NCS time, Tom had finished putting together the hour-and-a-half show. He put it on disks and distributed them to NCS registrants in the Reubens goodie bag. There remain a few rough spots and some of the images he wants to refine, but the disk represents his vision. Cruising the street fair, I chanced upon a booth selling original comic strips. What caught my eye was a huge Sunday Texas Slim strip. The strip had an off-again on-again history: a short run in the 1920s (August 30, 1925 - February 12, 1928), a 1930s revival for a year (October 4, 1931 - September 11, 1932) and a final spasm that lasted for 18 years (April 7, 1940 - 1958). It was produced by Ferd Johnson, who took the time to do it away from assisting Frank Willard on Moon Mullins, which strip Johnson eventually inherited when Willard died in 1958. Talking

with the person in the booth, I learned that the original art had belonged to

the late Dorothy McGreal, who had founded a magazine about cartooning in

1966. First published in June of that year, it preceded by two-and-a-half years Jud Hurd’s venerable Cartoonist PROfiles, which debuted in March

1969 and was for many years the only periodical devoted to cartooning. But for

a year, from June 1966 until its summer 1967 issue, McGreal’s Confronted by a short stack of McGreal’s journal on the table, I remembered hearing about it years ago. I may even own a copy or two, squirreled away in the Rancid Raves Grotto in the bottom of some box. The person staffing the booth was, I believe I remember him saying, McGreal’s grandson, who had inherited all the originals that she’d used in the journal. And he had all five copies of the journal on his table. When I asked, he replied that, yes, indeed—he had other sets that were for sale. I promptly bought a set. The covers of four appear near here; we’ll visit a little of the content at some latter time.

IN ADDITION TO

THE STREET FAIR MARKETPLACE, the downtown part of the Fest featured

presentations in the Big Tent, five-a-day Saturday and Sunday, plus “master

classes” and readings at the city library, several exhibits at the Art Center,

a special exhibit celebrating Popeye’s 90th anniversary, and a

40-foot long comic strip at the Pier. And storefronts all over had displays of

cartoons. A festival indeed. The impetus for staging the Fest was Steve McGarry’s. McGarry, a past prez of NCS and currently prez of the NCS Foundation, is the Society’s engine. He has been pushing NCS in this direction and that for over 20 years. In effect, NCS is McGarry’s organization. Or so it seems if you’re listening to him: “I became president of NCS in 2001 for four years , and I wanted to expand on the educational and charitable side of the organization. We created the NCS Foundation ... to do more outreach, more educational projects, more charitable works. I stepped away from the NCS for awhile, and then five years ago, I stepped back into NCS office and took over the Foundation.” The

Foundation was formed when an old member of NCS died and left to the Society an

apartment in New York City. Selling the property created a multi-million dollar

fund—ergo, the Foundation. To hear McGarry talk about it, the Foundation is

his. But that’s just verbal shorthand. In any case, without McGarry, NCS would have done absolutely nothing to advance the causes of cartoonists in the world. It would have continued on forever as an old boys’ drinking and marching society. Without the vacuum at the head of NCS, there’d be no opening for McGarry to step into and urge expansion and serious purpose on the otherwise moribund organization. His ambition of noble intent coupled to the void in the Society’s upper echelons created an opportunity for McGarry, and NCS is lucky to have both opening and McGarry. A Brit, McGarry lives and works in California but makes frequent trips to England, and there, he encountered the Lakes International Comic Art Festival. Soon he was talking with its founder and director, Julie Tait. Before long, he’d convinced her to organize a similar festival with NCS. From what McGarry says, most of the work of setting up the Fest was done by Tait and another European: “By bringing in Julie Tait and Mathieu Diez,” McGarry told Alex Dueben at The Comics Journal online, “we have these people with incredible know-how and connections. If we had done it cold, there’s no way I know how to deal with the police and the fire and the city and the permits and insurance. Organizing the marketplace is a full-time job in itself. The logistics are staggering. That was why I couldn’t figure out how to do it until I made these connections. “The other side of the coin is that they’re excited to be working with the NCS. We’ve now got this cross pollination so for Year Two we already know that we have people coming in from Finland, Japan, China, and we’ve already got concrete assurances from people who want to be a part of this. It’s a mix of wish list and practicality.” So—yes, there’ll be another NCS Fest next year. Where? Probably Huntington Beach. (McGarry lives in nearby Costa Mesa.) And why not? The event was a huge success. Maybe the crowds downtown weren’t as massive as hoped, but there were people enough. For the first year, a triumph, I’d say. (After all, I sold all of the books I’d brought to sell at our booth in the marketplace.)

THE PROGRAM AT THE HOTEL included Floyd Norman talking about “an animated life” (his), Sergio Aragones on Mad trips, former New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff (talking about his newest version of the Cartoon Bank, Cartoons Collection; see A-Gagging below for explanation), the art of George Herriman, Popeye’s Cartoon Club; editoonists Ann Telnaes, Kevin “KAL” Kalaugher and Michael Ramirez; “legacy strips” with Brian Walker (Beetle Bailey, Hi and Lois), Jeff Keane (Family Circus), Jason Chatfield (an Aussie just elected prez of NCS; does the Australian landmark strip, Ginger Meggs), and Jonathan Lemon (who just inherited a revived Alley Oop); Underground cartoonists (all women), Love and Rockets with Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, Jump Start with Robb Armstrong, artist Sean Phillips and writer Ed Brubaker on their criminal comic books, Cathy Guisewite on how to flunk retirement, and Robert Lemieux and Brian Walker on their hope to make a film about cartoonists and comic strips. (Don’t look now, but that film has already been made.) And more, much more.

THE BIGGEST PART of any convention is the interaction with the people. After Bob Mankoff’s session, I approached him to ask about his hopes and plans for Esquire, hopes and plans that he’d announced when taking the cartoon editor job there but which seem to me to have fallen increasingly short of his predictions at the time. Unhappily, Mankoff interpreted my question as hostile, and he protested that there had been cartoons in Esquire. Yes, I agreed—but not in the quantity I’d been expecting. He finally told me that magazines are all losing money in this country, implying with another sentence fragment or two, that Esquire just didn’t want to pay for cartoons in any quantity. I ran into him again a couple more times, each time seeking clarification. He finally admitted to the foregoing, in a manner of speaking, and we embraced to have our photograph taken at the Reubens Banquet. (No, his hair didn’t get in my way.) Earlier that day, I’d been walking down a hallway and I was pleasantly surprised to run into Kirstie Shepherd and Cesare Asaro, creators of the most elaborate and entertaining hoaxes and other playful evidences of comic art. For their first production in this line, they manufactured nostalgia in the form of two volumes that ostensibly reprint the popular comic strip Frank and His Friend, by Clarence “Otis” Dooley, who died in 1984. Like Dennis the Menace, Frank and His Friend appeared as a panel cartoon on weekdays; comic strip format on Sundays. But there is a difference: Frank and His Friend never existed as a syndicated cartoon. It’s all made up, its history, its creator—all of it, pure fiction. One of the books is of the dimension and production values of IDW reprints; the other, Time for Frank and His Friend, takes the form of a paperback reprint of the kind we no longer see in the stores, a little 4x7-inch tome (with the hoax price, $1.25, proclaimed in the upper right-hand corner of the cover; but its actual cost is about $15). Both books, magnificent fakes—perfect in every detail.

The larger of the two, Finding Frank and His Friend ($40), publishes for the “first time” penciled versions of printed strips that, it is claimed in the Foreword by Melvin Goodge (who also annotates the contents), were found in a box by Dooley’s son Lance while “remodeling the family’s home in Sandusky, Ohio to expand the jigsaw puzzle room to accommodate 5000-piece projects.” If

that scrap of syntax doesn’t tip you off to the hoax being perpetrated, the

“About the Author” note on the preceding page ought to: “Melvin Goodge is a

tenured professor at the Huntley Smoot University of Comic Sciences and serves

on the selection committee of the university’s prestigious Inker-in-Residence

program.” Melvin Goodge is actually Shepherd. Both books are available on Amazon, or at the website of the “publisher,” Curio & Co.,curioandco.com, where they also sell the comic book adventures of Spaceman Jax and pins and prints and posters and postcards and other faux memorabilia. The best fakes around. And funny, too. Delicious. I usually see Kirstie and Cesare at the Sandy Eggo Con, so it was a shock—a hugely pleasant shock—to see them at NCS. Cesare finally relented and joined the Society.

As you can tell (I hope), I had a great time. More choices of program sessions to choose from. Mostly pertinent topics. Cartoons all over the place. Signs and posters big and small plastered the name of the organization everywhere. Take another look at the photo of the shuttle bus. That kind of visual exposure was all around.

AL ROKER’S SECRET LIFE As a Cartoonist That’s right: the world famous weatherman at NBC-TV’s “The Today Show” was once among the inky-finger crowd. The Syracuse New Times reported on April 17 that during the early 1970s when Roker was attending school at SUNY Oswego and working part time as a weather forecaster on WTVH-Channel 5, he also, for a very very short time, put pen to paper as a New Times cartoonist, creating a comic strip called Salt and Pepper (white and black) which debuted in the October 3, 1976, issue. “I want the strip to reflect Syracuse,” noted Roker.. “You know, a good time.” With that, Roker married Doonesbury-style drollness to the Salt City scene, as his central characters Gregory Salt (a visual alter ego for the artist) and his Caucasian roommate McFarland W. Pepper lobbed then-timely shots at area politicians, multimillion-dollar edifices (such as the brand-new Civic Center), the deteriorating downtown picture (a background image in one panel depicts the Flah’s department store with a closed sign on its doors) and

even local television programs (a spoof of rival weatherguy Bud Hedinger, who hosted Channel 3’s Bowling for Dollars). Beyond the sometimes spicy seasoning of Salt and Pepper, however, Roker’s New Times’ stint was short and sweet. Roker drew just 10 strips before pulling the plug on his characters, as he pulled up his Syracuse stakes at year’s end to head for major-market status at a tv station in Washington, D.C. We’ve posted all 10 of the strips near here. And we give the New Times the last word: this retro sampling of strips from joker Roker’s New Times career provides a glimpse of the observational humor that would eventually propel this wisenheimer weatherman to early-morning stardom.

THE LAST BEETLES From the Stamford Advocate Mort Walker’s

last drawings of his famed creation Beetle Bailey were made inside Stamford

Hospital as a thank you to staff, days before the prolific cartoonist died in

his Stamford home in early 2018. Those drawings were presented to Walker’s

family recently at a brief ceremony at the hospital, which unveiled a framed

replica of one of the pictures that will adorn the wall outside the

rehabilitation center where Walker spent some of his final days. Other drawings, reported Ignacio Laguarde, depict Sargeant Snorkel, his dog, Otto, and another image of Bailey. One image depicts a screaming Snorkel with exclamation points and other marks beside his head. The cartoonist injured himself in a fall in mid-December of 2017, right after finishing a week of Beetle Bailey strips. He needed partial hip replacement surgery because of the fall, according to his son Greg Walker. While at the hospital, Mort got the flu, Greg said, and had to be transferred to the intensive care unit. He spent the final three nights of his life in his Stamford home. Michelle Pomar was Walker’s primary occupational therapist during his stay at the rehabilitation center. She remembered Walker fondly. “He obviously wanted to just draw, so that was a good way to get him up and moving and standing,” she said. Another framed picture that will go up outside the rehab center includes a photo of Mort drawing while in the hospital, above a cartoon by studio assistant Bill Janocha of Walker arriving at the Pearly Gates, a tribute he created after Walker’s death. Margie Walker Hauer, one of Mort’s daughters, was at the presentation. She said her father never retired. “Right up until he arrived here he was doing his work,” she said. Hauer said Mort’s greatest vice was chocolate cake, and the legendary cartoonist passed away on the same date as the unofficial holiday National Chocolate Cake Day, January 27.

ALCARAZ CONSULTS Lalo Alcaraz produces La Cucaracha, a nationally syndicated comic strip about a anthropomorphic cockroach (“la cucaracha”) and his milieu of human hangers-on. But Alcaraz is known around creative Los Angeles for his cultural consulting work on “Coco,” a popular, Academy Award-winning 2017 Pixar film about a 12-year-old who travels to the land of the dead on Dia de los Muertas, or Day of the Dead, a Mexican holiday. The offer for the 2½-year stint on “Coco” came as a surprise to Alcaraz, since years earlier he had created “Muerto Mouse” to criticize Disney when the company tried to trademark Dia de los Muertos. Alcaraz, alongside his team at Pixar, made integral changes to the film. Mama Elena, the abuelita (grandmother) in the movie, originally threatens family members with a spoon she carried. Alcaraz advised changing the spoon to her chancla, or flip-flop — to make the movie more authentic to Mexican culture. “I grew up in San Diego not seeing brown people on tv,” said Alcaraz, who is now the cultural consultant on “Los Casagrandes,” a new animated Nickelodeon show. “It’s not enough to see our faces. Our story has to be right.”

ODDS & ADDENDA Coincidentally, another distinguished publication is celebrating its anniversary just about now: it’s the Silver Anniversary (25th year) for Illustrators magazine. And to celebrate, the editors have rounded up a bunch of illustrators known for their pin-up caliber art: Milo Manara (38 pages of lissome lasses), Greg Hildebrandt (22 pages), Art Frahm (15 pages), and Margaret Brundage (13 pages). Being something of a connoisseur of such things, I’ve picked some representative pictures to post here by way of reviewing the book, but, alas, that’ll have to wait until next time: I’m rushing to get this up to our website before going off to the Denver Pop Cult Con, which begins in a day or so, and I dare not take the time to scan and assemble the line-up this time. So, until next we meet. ...

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Further Ado: It’s Personal SIXTY YEARS AGO An Anniversary Recollection IN MAY 1959, I WAS CONTEMPLATING THE END of my incarceration at the U. of Colorado in Boulder. It had been an engaging four years. And throughout, I had become increasingly involved in journalistic enterprises. My

first encounter with journalism had been drawing cartoons for the campus humor

magazine, The Flatiron (named after a geological formation in the

foothills next to campus). The magazine was published three times that season, the fall of 1955. The first was sold during registration, and that was when I learned about it. I did cartoons for the next two issues—the Homecoming and Thanksgiving issues— both of which were densely populated with my cartoons. The Thanksgiving issue resulted in the magazine being banned forever. Too much emphasis on sex and alcohol, the authorities said. Recounting this adventure in later years, I usually said that while the authorities were general in their condemnation of The Flatiron —i.e., as I said, “too much sex and alcohol”—most of the magazine’s pages carried one of my cartoons. Clearly, it was my cartoons that precipitated the ban. Well, no. Of the Thanksgiving issue’s 28 pages plus cover, only the cover and 7 pages carried one of my cartoons. Not too much. Just 25%. The previous issue—my debut issue—devoted almost 40% of its content to my cartoons: of its 32 pages plus cover, 14 pages and the cover displayed one of my cartoons. Clearly, if my cartoons were the cause of the magazine’s demise, my inaugural issue would have been the culprit. Well, no again. By the second issue I contributed to, I had been sufficiently shocked and awed by collegiate sexual escapades (my youth was severely sheltered) that I was doing more cartoons on that subject than on any other. So while there were fewer of my cartoons in the second issue I contributed to, more of the cartoons were about sex. And the evidence is posted nearby: the first two illos are the cover and one of the interior cartoons for my debut issue; the next two illos are the cover and an interior cartoon from the second issue.

Yes, too much sex and alcohol. Or maybe just too much sex. On one of the days after the ban had been announced, I was in the Flatiron office, surveying the damage, and I met Al Shepard, who was business manager of the now defunct magazine. Erstwhile business manager. We struck up a conversation, and he invited me to dinner at his apartment where I met his wife, Merta. The evening developed into the first of many long-distance nocturnal confabulations, some lasting well into the wee hours. Mostly about religion. I, former acolyte at the church of my youth, became an avowed atheist; Al, whose part in the discussions had nudged me in that direction, became, a few decades later, an Episcopal priest. I think we are both happy with the way things turned out.

WE ALSO TALKED about campus magazines. Al believed that we could revive the campus magazine at CU if we made it a “general interest” magazine, not a humor magazine. That would reduce the quantity of cartoons (and my shock-and-awe sense of humor would have less exposure). Sure enough, a year later, the Board of Publications approved Al’s proposal for a general interest magazine that Al christened Pan. I was managing editor, and I did a few cartoons. No sex. No alcohol. Pan, alas, lasted only two issues in the spring of 1957. Sales were so poor that we had to give up after the second issue. But I wasn’t finished yet. Al graduated that spring, but the following fall, I fomented another magazine publishing scheme. If sales wouldn’t support a campus magazine, then subsidies might. I persuaded the campus newspaper, the Colorado Daily, to publish a monthly “magazine supplement,” which would be distributed free to the vast student body. I was editor, and my friend (and a fraternity brother of Al Shepard’s) Chris Glenn was managing editor. (As “Christopher Glenn,” he would go on to a long career with CBS radio in New York; he died in 2006 at the age of 68.) Hue

& Cry lasted two issues. Dunno why it collapsed. The Colorado Daily certainly

didn’t run out of money. But producing a slick-stock magazine for the campus

multitudes was expensive, and the paper’s managers probably decided it wasn’t

worth the cost. After the collapse of Hue & Cry, I went on to other enterprises, joining the staff of the summer Colorado Daily for two years, launching in the second of those summers a humor and gossip column called Hare Today, and eventually becoming editor the third summer, the summer after I’d graduated. And I was layout editor of the yearbook, the Coloradan, when I was a senior. I set myself the unenviable task of doing individual, unique page layouts for all 496 pages of the book, every page a different design, or a different variation of a design.

BUT I HADN’T FORGOTTEN the halcyon days of writing and drawing for a magazine. All those hours doing Pan and Hue & Cry had pumped magazine journalism into my blood stream. As I contemplated graduating in the spring of 1959, I dreamed of someday become editor of a humor magazine for grown-ups. I even formulated a prospectus for the magazine, describing in some detail what I imagined the magazine might be like. Somehow, that never worked out. Mostly, I forgot my ambition. I got engaged elsewhere. I went into the Navy for three years, drawing cartoons all the way, and after that, taught English in high school for five years (no cartoons).

I enjoyed all eight years even though I was doing things I’d never planned on doing. But all of it was a challenge. Then when I secured a master’s degree, I rewarded myself with a trip to England sponsored by the National Council of Teachers of English. I met and was befriended by an NCTE executive, Bernie O’Donnell. He subsequently hired me as his assistant. After two years, his operation, a government-funded computer research data storage and retrieval enterprise, folded, and I became the Council’s convention manager, a position I held for the next 27 years, happy all the time. I enjoyed the challenge. All the while, I’d nearly forgotten about cartooning as a career choice. I was having too good a time doing other things. In 1978, I revived the idea and freelanced gag cartoons to magazines for four years in my spare time. A few samples are posted nigh.

My adventures in this area are rehearsed in an out-of-print book of mine, Not Just Another Pretty Face: The Confessions and Confections of a Girlie Cartoonist, which may, at some distant future time, be reissued by a mysterious publisher. Until then, you can find me blathering about myself shamelessly in two Hindsight pieces: “How the Happy Harv Freelanced Cartoons” (February 2012) and “It’s Not My Fault” (October 2012). I had a decent sales record, but I wasn’t excited about cartooning on spec. I eventually retired from that effort in about 1982. It wasn’t until a couple years ago as I contemplated finishing 18 years of Rancid Raves that I remembered the fond ambition of my youth to edit (publish?) and write and draw for a humor magazine of my own. Rants & Raves is not a humorous enterprise exactly (although I like to think it has its moments, albeit some unwitting ones), but it is a magazine, an online magazine with regular editorial departments and a schedule of publication and a focus on cartooning. It is, in fact—or very well might be—akin to the magazine I hoped to produced when contemplating my future 60 years ago. And now, thanks to my webmaster Jeremy Lambros, I’m doing it, and coming as close to satisfying at last the ambition of my unfettered youth as I’m likely to come these days. After all, I’m almost 82.... As

for retirement (from a regular job with a paycheck), it’s pretty clear that I

have failed at it. I work on my magazine every day, 2-3 hours a day. Get So I didn’t retire after all. Instead, I’m doing what I’d hoped in my so-called formative years that I’d do in the ensuing ones. Fascinating, eh? And who could ask for more? And what’s next, you might ask. Easy: a 25th year anniversary. We’re going for a quarter century mark, kimo sabe. See you then. (And everywhere along the way.) By the way, Rancid Raves webmaster Lambros does a cartoon called Domestic Abuse about common everyday household items—foods, kitchen utensils, books, parcel post, etc.—that talk to each other about their fates. It appears in the GoComics.com line-up. Don’t miss it if you can. Nearby is a sample.

FAMOUS TOUR OF RANCID RAVES It’ll be famous after this. Herewith, without further adieu, we commence the Tour de Farce by parading before you photographs that I’ve lovingly taken of the places I work—and the trinkets I’ve shelved to make my surroundings suitable.

HAVING BEHELD THE PLAYTHINGS of the Rancid Raves Study, we now proceed down the stairs to the R&R Grotto, where the Studio is located. Once there, we do a repeat performance but this time with different toys on display.

FURTHER ADO I have a pretty girl, And who could ask for more? She’s deaf and dumb and oversexed And owns a liquor store. —Anonymous Antique Male Brag Verse

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics

ONE WAY OF CELEBRATING our 20th year is to re-visit some of the milestone conjurings of the Distant Past. As it happens, we have Just the Thing in a review of Bob Hall’s Batman: I, Joker, which was posted here in Opus 2, May 1999. Herewith, that review—: All Hail, Hall. Bob Hall, you may recall, is Armed and Dangerous. Armed and Dangerous, you may recall, was a series of comic books that came out a couple years ago in striking black and white. Written and drawn by Hall, the books told tales about underworld types like those Hall had known (or had heard about) in the scruffier neighborhoods of New York City, where he served time as a youth. Hall was producing fiction in this series but some of the incidents were based upon actual events (or neighborhood gossip about actual events). The stories were superbly rendered in a stunning chiaroscuro manner. And Hall demonstrated a spectacular mastery of the techniques of comic book storytelling, too— pacing the action and conjuring up atmospherics expertly on every page. Well, he's back at it— this time with one of comics' icons. Batman: I, Joker ($4.95) is an Elseworlds Batman story told by the Cowled Crusader's arch enemy. But the plot is laid far in the future by which time Batman is a god-king called "The Bruce." And in that concept, Hall has constructed a mythos upon which the entire fabric of superhero comicbooks can be erected. The Bruce is maintained in power by the faith of the populace, and the faith of the people is sustained by regularly enacted feats of violence against a re-appearing cast of villains— the Penguin, Two-face, the Riddler, Ra's al Ghul, and the Joker. Once every year, volunteers are invited to capture or kill one of this bunch— and, if successful, to challenge the Bruce to personal combat to the death. If victorious, the successful citizen will become the new god-king. In addition to incorporating elements of the Fisher King myth, Hall has devised (as I trust you can tell from the foregoing) a clever parable that parallels the relationship between the comic book hero, Batman, and his faithful readers, you and me, before whom (like the Bruce), Batman re-enacts periodically the ritual conquest of a litany of arch villains. Having set up the resonances of this situation, Hall then proceeds to explore its implications. And I'll not say more about that in deference to your undoubted desire to find out what happens on your own. Hall's artwork and storytelling abilities are well displayed in this book. He renders anatomy in chips and chunks like raw meat, making dramatic use of solid blacks and deep shadows, and he paces the tale with breakdowns that create the story's atmospherics in flashes of consciousness. Nifty stuff, deftly done. Look for your copy in the back-issue bins at the summer cons.

Quotes & Mots WHITHER DEMOCRACY? One guy is making decisions that shake the world’s economies. The Trumpet. How did that happen? Setting tariffs is the duty of Congress, not the executive branch. It sez so right there in the Constitution, Article 1, Section 8 [1]: “The Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties. ...” “Duties” are “tariffs.” So what happened? Congress gave away its right. It gave it away because its members are cowardly: they don’t want to make unpopular policies that might upset re-election plans; so some years ago, they foisted off on the Prez the responsibility for setting tariffs. And then we have the impending war with Iran. The result of a decision by one guy. The Trumpet. Where’s democracy gone?

TRUMPERIES The Outlandish Antics of Our Prez and Those Who Ridicule Them The Trumpet made the cover of The Week again, as he often does, but this time, the artist, William McFail, employed a familiar image, that of Grant Wood’s American Gothic, which has elicited admiration, disgust, reverence, and ridicule in hundreds of thousands of parodies in every medium ever since it first arrived in 1930.

On the cover of The Week, Wood’s resolute farmer wears a MAGA cap and everything has a price tag, which shows that the cost to the farmer has increased. That’s the message. Oddly, another artist (whose name, alas, I failed to record) echoed the same image on the cover of The New Republic, which arrived in my mailbox the same day as The Week. Just coincidence, and those in the image are different—AOC and Bernie. Below them, Marshall Ramsey starts us off with the Trumpet claiming he doesn’t do cover-ups. And yet his hair-do betrays him: itself one of the most outlandish of comb-over cover-ups, when the wind blows, it can flip back—revealing that which is being covered up. In small type on pate, it says “paying off porn stars.” Chris Britt closes out this visual aid by having fun with a comic strip that deploys a recent pronunciation problem that the Prez lately suffered: he couldn’t make it past “orange” to “origin.” And from there, Britt takes him all the way to bananas. Our

next exhibit gets a little more serious. Next around the clock, Bramhall continues by revealing Trump’s understanding of the Constitution’s mandate separating the powers of government. He separates by destroying the essential whole, a visual reference to Trump’s various attempts to get around Congress, to ignore the powers of the legislative branch, taking those powers unto himself. The revered Founders are doubtless turning over in their graves. The Trumpet continues in the same destructive mode in Mike Luckovich’s hands. The central image is of Trump choking the life out of Lady Liberty. The groveling obsequiousness of the Republicon Party gives the picture a second barb. Then Tom Toles invokes the fable about George Washington’s compulsion for honesty. He could not tell a lie, but the Trumpet confesses, in the same manner and setting as the Washington original, that he cannot tell the truth. The perfect balance of this verbal hijinks is given a second tweak of meaning when we see that the hatchet-wielding Trump has chopped down not the traditional cherry tree but a statue representing the Founder’s intent with the Constitution. Trump is doing away with all those annoying considerations. With that, we end the Trumperies for now and proceed directly to—:

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THE TRUMPET

STARS in the first few editoons, beginning with John Cole, whose imagery

deals with two government expenditures: the Prez’s cost to Americans is

contrasted to the cost incurred by Mueller’s investigation. Next, we shift to the war mongering of recent days as John Bolton gets the Trumpet ready to engage with Iran. David Horsey’s Bolton understands the Prez: for the Trumpet, it’s all a show, donning military garb and accouterments. Nothing about the cost in human life that may result. Tom Toles depicts the warlike posturing as a high wire act, with Bolton attempting to carry a huge bomb (the threat of war) across the wire. Below, Uncle Sam is negotiating with Iran and asks the question that always tips us off: something, indeed, could go wrong. Bolton could lose his balance and fall, bomb and all, onto Iran. Pat Bagley’s comic strip generally addresses the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm’s tendency to think it speaks for all sorts of otherwise under-represented points of view—those of the unborn, the gun nuts, soldiers who’ve died in combat, even God. After calling the role of the potential witnesses, Bagley notes that none of them could be reached for comment, thus undermining the GOP claim. In

the next visual aid, Kevin Siers begins with two panels, the second of

which cautions against the behavior urged by the first. Pat Bagley goes after the questionable financial behavior of the National Rambo Association’s executive director, Wayne LaPierre. He’s paid over a million/year, but he also charges expensive wardrobe purchases and exotic vacations in the Bahamas to NRA. As Bagley shows us, while LaPierre is alerting NRA members to threats to their gun rights, he’s picking their pockets to finance his extravagant life style. Bill Bramhall is a little more specific, showing the goods LaPierre is buying (all expensive labels) that he is dedicated to keeping in his cold dead hands, the latter phrase invoking Charlton Heston’s famous claim about his possessing guns that he’d cling to until death did they part. Clay Jones at the lower left takes up another subject, the Trumpet’s treatment of the children of immigrants. The caged kid’s comment points out the hypocrisy of the Right: they’ll keep certain children in cages, but at the same time, they’ll insist that unborn children are sacred, their lives sacrosanct and must be protected. Selective humanity. Immigration

is still the topic in our next display. The trade war is the next topic, and Pat Bagley has the Trumpet uttering his usual mantra while being fried by the Chinese dragon’s flaming breath. At the lower left, John Darkow presents the plight of U.S. farmers who are being hurt by Trump’s tariffs on China. Trump’s position in the picture and the farmer’s comment blend to make Trump’s mantra just so much manure—er, bullshit? We

continue in much the same vein in our next array. At the lower right, Mike Luckovich takes up the topic of abortion, his diagram asking the question neither side of the debate could handily answer. Clay Jones’ visual metaphor for the treatment of women by anti-abortion forces in Alabama, Georgia and Missouri is stark with just a touch of unthinking humor—finger wiggling. The

abortion debate continues in our next visual aid. At the lower right, David Horsey gets us into the 2020 Election. In his visual metaphor, the 20 Democrats seeking their party’s nomination for prez are like flavors of ice cream at the local Baskin Robbins store. He next attends to the likely confusion among voters who contemplate too many candidates, and too many of them with unpronounceable and therefore unmemorable names. Michael

Egan draws a cartoon-like poster image in our next display. Chris Britt takes a poke at evangelical support for the Trumpet: in the person of Franklin Graham, they ignore all of his immoral behaviors (as indicated by the badges on his chest) because they are thankful that he isn’t gay. Impeachment is the next topic. In Chan Lowe’s ingenious metaphor, the Democrat jackass cannot see a call to impeach Trump because he’s looking through glasses that force him to see everything in the context of the 2020 election. Meanwhile, Rob Rogers dramatizes the Democrat impeachment dilemma: either way—impeach or not—is poison. In

our last visual aid, we have a miscellany of topics. Next around the clock, Bud Plante deftly illustrates the Democrat dilemma in contemplating some candidate’s run for the White House in a year that the economy is so good. And Steve Sack finishes our sojourn among last month’s editoons with an image that shows the effects of Trump’s tariffs: they act as a boot affixed to the wheel of a shopping cart, thereby preventing U.S. consumers from doing any shopping. And that will affect the economy. Despite what Trump proclaims, the financial burden of his tariffs will be borne by American consumers.

PERSIFLAGE & FURBELOWS Quoting Steven Wright—: I woke up one morning, and all my stuff had been stolen and replaced by exact duplicates. The hardness of the butter is proportional to the softness of the bread. To steal ideas from one person is plagiarism; to steal from many is research.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

HAVING STARTED

TO READ DRABBLE even though it hurts my eyes, the top strip in our next

display has Norman Drabble in it. A rare appearance. In the next two strips, the whole family goes to visit Uncle Mike at his alpaca ranch. Tell me how many people are in the car in the second and successive panels. I think three, but it’s hard to tell. Fagan’s strange drawing style needs space for definition, and the inside of a car isn’t enough space. Particularly with two alpacas invading. Uncle Mike, though, looks the most human of any of the Drabble cast. It’s his dark glasses, of course: they locate his eye exactly where most eyes go, not where Drabble eyes usually go, which, as the last panel in the third strip shows, is both eyes on one side of the nose. Sometimes. Sometimes not. In the adjoining Free Range panel, Bill Whitehead delivers a much-needed anatomy lesson to Fagan (and all the rest of us). But in my local paper, The Denver Post, the panel is reduced too small, and it’s nearly impossible to discern the picture. And in this case, that’s too bad because the picture shows that none of the people have eyes or mouths—hence, the joke. The paper is saving space but destroying Whitehead’s comedy. And speaking of comedy, in Luann, Greg Evans’ joke depends upon our knowing what “with benefits” means. It means “with sex.” Anyone still believe that newspaper comic strips are produced expressly for consumption by children and only children? Finally, here’s another of Jim Davis’ Garfield that disproves the allegation that the strip is always static, always motionless. Here, motion is the joke: Odie turns his head so fast that his always-hanging-out tongue whips around Jon’s neck and face. But the impression of static art endures. Probably because all the characters are severely “on model,” every aspect of each character drawn the same in every appearance, time after time. The joke is all motion, like animated cartoons. I wonder if Brett Koth, a long-time friend and co-conspirator of Davis’, is still conspiring to create gags with him. Koth worked in animation for years before joining the Garfield crew. Now he’s also doing his own comic strip, Diamond Lil, about a cranking old woman. See it at GoComics.com.

Strange

and Wonderful Department. If you have really REALLY good eyesight (or, like me, have access to a

magnifying glass), you might make out what’s printed on the newspaper Blondie’s

reading. It says “sudoku.” Next we have another execrable incarnation of Kevin Fagan’s Drabble, the strip the name of which describes the drawing style. In the second panel, are both of the guy’s eyes on this side of his nose? If so, what happens to the western one in the next panel? And the next? I don’t know what “goo goo g’joob” means in Chad Carpenter’s Tundra, so I e-mailed the number given. No response. Did it again. Still nothing. Clearly, as Carpenter has so helpfully indicated, “operators are standing by” sound asleep and not being at all responsive. And just when I thought I’d be destined to go through what remains of my life not knowing what “goo goo g’joob” means, Andrew Farago came to my rescue. I posted the errant Tundra strip on my Facebook page, hoping someone Out There would know what “goo goo g’joob” means. And Andrew knew: it’s a reference to a Beatles song, “I Am the Walrus,” of 50 years ago. Who knew? And then we have a Peanuts Sunday in which Charles Schulz contrasts aspirations for a material life to aspirations for a satisfyingly life of meaningful relationships. When we need philosophy, we turn to Peanuts, and are never disappointed.

SOMETIMES

CARTOONISTS do things in their cartoons that can't be done anywhere else, in

any other medium. Hereabouts are some examples.

HERE ARE A

COUPLE MORE in the same vein. Brooke McEldowney in his 9 Chickweed Lane strip often features the siamese cat we see in the next example, peeking over the edge of the strip’s panels. The cat’s appearances usually involve some similar playful violence to the form. The next two are not of the same sort but each of them is playing with some aspect of the visual-verbal medium.

TICS & TROPES From Harper’s Index—: Number of people executed for sorcery in Saudi Arabia since 2011: 4 Age of an Afghan “war hero” assassinated by the Taliban earlier this year: 11 Percentage of U.S. women who do not identify as feminists: 33 Who identify as “strong’ feminists: 17 Number of states in which “cartoon” is the most popular search term for Internet pornography.

In Honor of Our Finishing Our 20th Year of Posting Rants & Raves SILVERSTEIN AMONG THE GIVERS AND THE TAKERS Re-running Our Obit for the Most Eccentric and Talented Cartoonist of His Day (and Ours) AS A CALLOW YOUTH, I WANTED TO BE SHEL SILVERSTEIN. I’m older now, and Shel Silverstein has died. I no longer want to be Shel Silverstein, but whether that’s because I’ve become wiser with age or because being dead doesn’t sound like a viable option is a question that might be debated more appropriately by others. I know, however, that I have nowhere near the talent to have been Shel Silverstein, and if self-knowledge isn’t wisdom, I don’t know what is. But when I was in college as the fabled fifties drew to a close, Shel Silverstein was what most freelance cartoonists would have killed to be. He was on assignment for Playboy magazine, traipsing all around the world to submit regular cartoon reports on such romantic capitals as London, Moscow, Tokyo, Paris, Moscow, and the like. Shel was the putative star of this reportage. His cartoons purported to record his actual adventures in these exotic spas— his (typically America) misunderstanding of local custom, his acceptance of stereotypes for the natives, his perpetual failure to score with the indigenous female population. In Tokyo, Shel is with a geisha and says, “American girls don’t understand me ...” (Geishas are not prostitutes, so Shel must troll with the hoariest of male lines.) In Moscow, Shel sits with his arm around a woman and says, “So you see, Olga, with world tension as high as it is— with humanity threatened with total destruction through an atomic war— with Russian-American diplomatic relations strained almost to the breaking point— it’s up to people like you and me to cooperate.” In Paris, Shel shows himself handcuffed to a gendarme who is phoning for a paddy wagon. Shel says, “You let Gene Kelly dance in the street, you let Fred Astaire dance in the street, you let Audrey Hepburn dance in the street, you let ...” In a bar in Spain, Shel depicts himself having a drink with a bull, and Shel is saying, “Okay, but now let’s look at it from the bullfighter’s point of view ... ” A certain number of cartoons with each report transpire in a typical setting for the place — in front of Buckingham Palace in London, at the base of those onion-turreted buildings in Moscow, along a street of chalets in Switzerland. The ornate architecture is delineated with a thin and sometimes wavering line, but the pictures are marvelously detailed, creating a filigree of authenticity.

In these pictures, Shel portrayed himself as the burly bearded vagabond bohemian that he undoubtedly was. And I longed to be exactly that. I longed to set off around the world with a shaggy beard and a rucksack bound for far-flung parts with naught but pen and sketchpad to sustain me. Hanging out with all the glamorous sex-starved women of foreign climes was appealing, too. (If you believe Playboy, all women are sex-starved. Or they were then. Or maybe it was merely my imagination, an imagination, admittedly, just this side of raging adolescence.) When,

eventually, I did travel to some of those destinations it was with the U.S.

Navy not with a beard. (Alas, I was never able to cultivate a thick beard

like Shel’s. Mine was more in the vicinity of wispy. In less than a decade,

however, I was able to match him in the baldness dimension. And that was about

the only way I could match Shel Silverstein. Then and now.) Protean is a word reserved for talents like Shel’s. When ABC World News announced his death on May 10, 1999 they said he was a children’s book author whose poems were much beloved by children (and their parents). The NewsHour on PBS said about the same but managed a furtive aside about his suspected cartooning career, the implication being it was long in abeyance. The entertainment press called him a singer, composer, and songwriter. He was all those things. Troubadour, lyricist, playwright, screenwriter, illustrator, journalist, children’s author, poet, director. And cartoonist. Actually— to plumb for the cause of these effects— he was a cartoonist first, both chronologically and creatively. All the rest flowed from this sensibility.

BORN IN CHICAGO September 25, 1930, Silverstein was drafted in September 1953 just as he turned twenty-one. According to his own report, he’d been “thrown out” of the University of Illinois, but he’d been nurtured thereafter at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. The Army sent him off in the direction of Korea, where a “police action” had degenerated into the stalemate of a permanent cease-fire. After a year or so, he was assigned to the staff of the Pacific Stars and Stripes, for which he drew cartoons about military so-called life. He was an exemplary soldier cartoonist, according to Bill Mauldin, another exemplary soldier cartoonist. “The thing about real military humor,” Mauldin wrote (in Grab Your Socks, a 1956 collection of Shel’s Army cartoons), “is that when a soldier says something funny he is mainly trying to ventilate his innards. ... He’s being sardonic. If he tried to say it straight, he’d simply bust down and cry. The ordinary gag man says, ‘See the funny soldier’ and doesn’t get the message. Shel Silverstein has got the message and passes it on.” Shel’s career as a G.I. cartoonist is, as they say, legend. “How Silverstein talked himself into and out of trouble with military censors, often hiding out for weeks at a time in the Korean hills, and how he turned up two years later in Chicago in civilian clothes— the full story may perhaps never be known.” What is known is that he began freelancing cartoons to various magazines, one of which was Playboy. Hugh Hefner, a fugitive from cartooning ranks himself (when he was in college), was looking for cartoonists who would give his new magazine a distinctive look and feel. He had enlisted Jack Cole by this time, and Cole’s full-page full-color watercolor cartoons were a beacon lighting the way. In Silverstein’s cartoons, Hef saw another kind of uniqueness. (He also knew that Shel’s work hadn’t appeared in many other places, and Hefner wanted Playboy cartoonists to be found mostly— if not only— in Playboy.) In August 1956, Shel’s work began appearing in Playboy, and for the next 42 years, his cartoons and articles were published there at irregular intervals. His globe-trotting series (“Silverstein in Scandinavia,” “Silverstein in Africa,” etc.) began in May 1957 and appeared once or thrice a year until the early 1970s. By that time, he was well-established as an author of children’s books and as songwriter. By the end of the next decade, he was secure enough in his various guises to shun publicity of all kinds (the most recent interview with him was published in 1975). He enjoyed a reclusive life-style in his houseboat in Sausalito, an apartment in Greenwich Village, and homes in Martha’s Vineyard and in Key West. “I am free to leave,” he said, “to go wherever I want, do whatever I want. I believe everyone should live like that. Don’t be dependent on anyone else. I want to go everywhere, look at and listen to everything. You can go crazy with some of the wonderful stuff there is in life.” In the sixties, as an established bon vivant, Shel was frequently photographed at the Playboy Mansion, his shiny dome surrounded by Bunny bosoms. But he probably spent more time at Chicago’s Gate of Horn and New York’s Bitterend. He sang folksongs and his own bawdy ditties, and he composed songs for others. The most celebrated of these is doubtless “A Boy Named Sue,” which Johnny Cash’s 1969 recording made into a hit world-wide. Silverstein also wrote songs sung by Irish Rovers, Brothers Four, Lynn Anderson, Loretta Lee, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bobby Bare, and Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show--songs like “The Unicorn,” “Payday,” “One’s on the Way,” and “I’m Checkin’ Out,” written for the film “Postcards from the Edge” and nominated for an Oscar in the 1990 competition. His collaborations with Dr. Hook resulted in a series of successful singles and albums for the band. In the 1970s, Shel decided to explore playwrighting. “I’ve been fooling with the thoughts about these plays long enough,” he told Jean Mercier at Publisher’s Weekly; “the time has come to see if I can bring them off.” And he did just that. The first of his plays, “The Lady and the Tiger,” premiered in 1981 at the Ensemble Studio Theater in New York. Over the next dozen years, Silverstein wrote nearly two dozen plays, mostly one-acters, and in 1988, a screenplay, Things Change, in collaboration with David Mamet. But it is as “poet laureate for children” that Silverstein is most likely to be remembered. He was, he said, “dragged, kicking and screaming” into writing children’s books by his friend and fellow cartoonist Tomi Ungerer (see Opus 389 for obit).

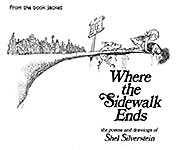

ALTHOUGH HIS FIRST BOOK is often cited as Lafcadio the Lion Who Shot Back in 1963 (a book that remained Silverstein’s favorite), Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book: A Primer for Tender Young Minds preceded it in 1961 and may have been the credential that recommended him to Harper. The ABZ incorporates material that originally appeared in Playboy and is decidedly adult in content, but children read it and enjoyed its playful perversity, and that bent humor surfaces again in Shel’s poetry books. In 1964, Harper brought out his fable, The Giving Tree, about an altruistic tree that sacrifices its shade, fruit, branches, and even its trunk to make a little boy (then a man) happy. The book inspired much comment from pulpits and ecologists, all favorable; but feminists criticized the story because the tree was feminine and, therefore, the boy was sexist. Silverstein’s

first collection of poetry for children, Where the Sidewalk Ends, came

out in 1974, followed in 1981 by A Light in the Attic. His poetry for kids is a deliberate departure from the usual honeyed sweetness of children’s verses. Called “sophisticated, sometimes macabre, and always enchanting,” Shel’s poems often take a wholly unexpected and frequently gross turn by the last line. Consider “Gardener,” for instance: We gave you a chance / To water the plants / We didn’t mean that way— / Now zip up your pants. Or “The Land of Happy”:

Have you been to The Land of Happy, Where everyone’s happy all day. Where they joke and they sing Of the happiest things, And everything’s jolly and gay? There’s no one unhappy in Happy, There’s laughter and smiles galore. I have been to The Land of Happy-- What a bore!

The humor in the first example derives, ultimately, from a childlike acceptance of ordinary scatological facts of life. In the second poem, the comedy resides in the breakdown of the cheery rhythm at the last line, which coincides handily with an apparent about-face in attitude. These are poems with punchlines. They deploy standard comedic maneuvers that have proved as durable for standup comedians as for poets. But I think Silverstein’s wit in such instances reveals his apprenticeship in cartooning.

SINCE BOTH HIS POEMS AND HIS CARTOONS are humorous, the relationship may appear too obvious to dwell on. What’s funny is funny. But there’s more than just comedy that connects the two. Single-panel gag cartoons involve a particular cartooning sensibility. As I’ve said often enough to be tedious, in all good cartoons, words and pictures blend to create the comedy. The pictures don’t make as much sense without the words; and the captions usually aren’t funny without the picture. Together, words and pictures achieve a humorous meaning that neither is capable of alone without the other. In the usual gag cartoon situation, the picture is at first blush a puzzle. The puzzle is “solved,” its significance is “explained,” by the caption. This significance dawns upon the reader suddenly in reading the caption. In a well-constructed cartoon, the dawn comes as a surprise. The exact meaning of the picture as explained by the caption is unanticipated. While we may not expect precisely that meaning, when it is offered, it is completely understandable, even sensible. Our laughter comes as a manifestation of the pleasure of discovering a “meaning” that so perfectly suits the picture. Or a picture that perfectly fulfills the verbiage. Silverstein’s cartoons for Stars and Stripes were excellent examples of the puzzle sensibility of a cartoonist at work.

So were his cartoons for Playboy. The cartoons in his gargantuan coffee-table book, Different Dances (1979) are more elaborate instances of the same sort of thing: these are not single-panel cartoons but sequential pictures in pantomime. Still, each sequence is introduced by a word or phrase (“Keeping Time,” “She Enters My Life,” “The Escape”) that gives the pictures their meaning, their significance. And in this case, the significance arises from a view of human nature that is insightful as well as comical. His poetry often does precisely the same sort of thing. The concluding lines in both the poems I’ve quoted, for instance, are unexpected, surely; and their meaning gives other nuances to the lines that precede them. And our laughter results when we discover this new meaning or significance and are surprised by it. Silverstein illustrated his books of poetry profusely. Some of the illustrations are decorations. But some serve to “explain” the meaning of the poem they decorate. In “Something Missing,” we need the picture to realize that the thing the narrator forgot when dressing was his pants. In “Fancy Dive,” the picture shows alarm in the face of the diver, alerting us to the problem that causes his elaborate gyrations: the pool into which he is diving is empty. In “Snake Problem,” the last line is “written” by the contortions of the snake, who spells out “I love you” in cursive script. And in “Surprise!” the elephant shape of the shipping crate tells us what the poem does not— that is, exactly what it is that Grandpa has sent to his grandchildren. Even when his pictures don’t reveal meaning expressly, their presence adds a dimension to his work in much the same way as Dr. Seus’s pictures added to his, and Edward Lear’s likewise (to invoke the names of Shel’s only obvious antecedents in the illustrated children’s poetry racket).

EVEN AS A POET, then, Shel Silverstein was a cartoonist. And as a cartoonist, he was perforce one of the most accomplished and therefore distinguished of the inky-fingered coterie because he expanded the capacities of this sensibility to embrace other art forms. And so it rankled, just a little, that this unique talent, this cartoonist, was so often glossed over in obituaries about the children’s poet. He was so thoroughly both. As cartoonist/poet, Silverstein engaged an antic imagination that was astonishingly fecund. A friend, Otto Penzler, bookseller and publisher of several collections of detective stories, wrote the following: “When he is asked to write the lyrics of a song, he needs no more than fifteen minutes. When I asked him to write a story for this book [of mystery stories], he said, ‘Well, I’ve never written a crime story in my life. Wait— I have an idea.’ He never paused for breath between those two sentences. The fable that follows is that idea. In his various homes, he has drawers full of songs and stories and fables and drawings and plays and poems that he’s never gotten around to sending to his agent or his publishers.” A possibly apocryphal story about Shel goes like this: Dr. Hook and his band were rehearsing on the West Coast and they got a phone call from Shel on the East Coast. “Got a pencil?” he asked. “Just a minute— yes.” “Okay, write this down.” And he dictated lyrics for a new song. This prompted the good Dr. to ask: “Shel— why are you phoning me?” “I couldn’t find a pencil,” he said. Silverstein was passionate about the need to create and to communicate. On his houseboat he kept a piano, a guitar, a saxophone, a trombone and a camera, and he “noodles around” with them all “just to see if I can come up with anything.” He continued: “I have an ego, I have ideas, I want to be articulate, to communicate, but in my own way. People who say they create only for themselves and don’t care if they’re published . . . I hate to hear talk like that. If it’s good, it’s too good not to share. That’s the way I feel about my work.” That a man with such a great heart should die of a heart attack seems somehow anti-poetic. Or maybe it’s poetic license yet— of the Greek tragedy sort, his heart being hubris. His body was found in the bedroom of his Key West home on the morning of May 10 by two cleaning women who had arrived to do the housework. He had apparently been writing in bed. More poetry— that this prolific cartoonist would be working on yet another project when he died. Silverstein was somewhat puzzled by the phenomenal sales of The Giving Tree. “Maybe it’s because the book presents just one idea,” he said once. The controversy of the supposed symbolism of the book was another thing that didn’t concern him. He resisted reading moral significance into the story. “It’s just about a relationship that exists between two people,” he once said; “one gives and the other takes.” Shel Silverstein was a giver.

And so am I. For a price. The foregoing essay, I have converted to a monograph that is accompanied by Silverstein’s rare, seldom seen and never, elsewhere, reprinted 23-page “cartoon history” of Playboy, published in the magazine in the first three issues of 1964 to commemorate the 10th anniversary (32 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w). It’s available at $10, including p&h; just write me at the end of the scroll.

PERSIFLAGE & BADINAGE “Silence is the language of God. All else is a poor translation.”—Jalal ad-Din Rumr