|

|||||||||||

Opus 380 (completed June 2, 2018). Up out of the Rabbit Hole this time, a Bunny Bonus report on the Reubens Awards conferred May 26 by the National Cartoonists Society—complete with errors and corrections and the Usual Carping by Yr Faithful Rptr, this time based upon Solid Statistical Evidence. Here’s what’s here, in order—:

NCS Loss of Prestige List of Winners Corrected List Panel Presentations Other Events History of Division Awards (Rubes)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

BUNNY BONUS Report on the Reubens Weekend of the National Cartoonists Society AT THE 72ND ANNUAL REUBENS AWARD WEEKEND, May 25-26 in Philadelphia, NCS conferred its 15

annual awards, including the Reuben itself for “cartoonist of the year,” which

went to Glen Keane, a Disney animator. That means 12 of the winners didn’t think enough of the award to show up in case they would win. The number is actually higher than that. There were two winners in two categories, and of the 5 nominees for the Reuben, 2 didn’t attend. (The Reuben winner three years ago, The New Yorker’s Roz Chast, wasn’t there to pick up her trophy.) NCS bills itself as “the world’s premier organization of professional cartoonists.” If we are to judge from the foregoing attendance records, not very many professional cartoonists think very highly of “the world’s premier organization for professional cartoonists.” All of the nominees for the Reuben have been nominated before—except Keane. In alphabetical order, this is the second nomination for Lynda Barry (Ernie Pook’s Comeek), the 9th for Stephan Pastis (Pears Before Swine), the 4th for Hilary B. Price (Rhymes with Orange), and the 2nd or 3rd for Mark Tatulli (Heart of the City and Lio; he says only “numerous times”). Neither Barry nor Pastis attended. This was Keane’s first nomination. He has spent most (if not all) of his animation career at Disney. In 2013, he was named a Disney Legend. And at the 90th Academy Awards, he and basketball superstar Kobe Bryant won the Best Animated Short Film Oscar for “Dear Basketball.” As

winner of the Cartoonist of the Year award, Keane gets a large, heavy metal

trophy, which is called the Reuben after its creator, Rube Goldberg, who

was also the first president of the Society. Since 1956, the NCS has conferred a secondary level of award for achievement in various cartooning genre—comic book, editorial cartoon, magazine gag cartoon, and advertising illustration. The list has expanded over the years. These awards have been termed “division awards” for most of their history, and recipients get a metal plaque. Over the years, division awards have acquired the nickname Reuben: recipients say they’ve won a Reuben for Best Newspaper Comic Strip, f’instance. But division awards are not Reubens; only the Cartoonist of the Year gets a Reuben, the Goldbergian trophy. Confusion, nonetheless, reigns. Finally, to make the distinction clear, a couple of years ago, the NCS Executive Board determined that the division awards should be called “Silver Reubens,” surrendering to a misnaming tradition already in place but modifying it to distinguish it from the Big Award, the Reuben itself. At the business meeting this year, several members expressed annoyance with the Silver Reuben nomenclature. To give a subsidiary award a precious metal adjective seems to cheapen the Reuben itself, which is condemned to going through history without a metal adjective. The physical trophy is bronze, I think, but a Bronze Reuben sounds even cheaper than the unadorned Reuben. My vote: call the division awards Rubes, the shortened form of Reuben, hence subsidiary. It’s also the name Goldberg signed to his cartoons, so he would continue to be honored in the custom of the Society. But nobody listens to me. This year’s Rube winners are listed herewith. I’ve included the nominees as well as the winner in each category because even being nominated is an honor. The winner’s name is preceded with an *asterisk. Here we go—:

Magazine Feature/Magazine Illustration *Peter Kuper, Tom Richmnd, Johnny Sampson Advertising/Product Illustration Farley Katz, Johnny Sampson, *Dave Whamond Television Animation *Alan Bodner (Disney’s Tangled, The Series), Rustam Hasanov (Dreamworks, Troll Hunters), Sean Jimenez (Disney’s Duck Tales) Feature Animation Beniamin Renner, Patrick Imbert (Big Bad Fox and Other Tales) Nora Twomey (The Breadwinner) *Lee Unkrich, Adrian Molina (Coco) Comic Book Cliff Chiang (Paper Girls), Dean Ormston (Black Hammer Secret Origins), *Sana Takeda (Monstress) Graphic Novel *Emil Ferris (My Favorite Thing Is Monsters), Tillie Walden (Spinning), Campbell Whyte (Home Time) Newspaper Illustration Greg Cravens, Glen LeLievre, *Dave Whamond Book Illustration Ryan T. Higgins (Be Quiet), *Adam Rex (The Legend of Rock Paper Scissors), Ed Steckley (Rube Goldberg’s Simple Normal Humdrum School Day) Magazine Gag Cartoon (all New Yorker cartoonists) Pat Byrnes, Joe Dator, *Will McPhail Online Comics—Short Form *Gemma Correll, Lonnie Millsap (Bacon), Mike Norton (L’il Donnie) Online Comics—Long Form *John Allison (Bad Machinery), Vince Dorse (Untold Tales of Bigfoot), Ru Xu (Saint For Rent) Newspaper Panel Cartoon Dave Blazek (Loose Parts), Harry Bliss (Bliss), *Mark Parisi (Off the Mark) Editorial Cartoon Clay Bennett, *Mike Peters, *Michael Ramirez (tie) Newspaper Comic Strip Terri Libenson (Pajama Diaries), *Mike Peters (Mother Goose and Grimm), Mark Tatulli (Lio) Notice the recurrence of several names, another sign that the awards aren’t valued much: not enough cartoonists in some of the categories submit their work to be juried for the awards. Why not? Not enough prestige, I suspect.

Wait! Hold On. Just a Minute! What about those names I underscored? Well, as it turns out, those are the real winners in those divisions. On Friday night, just as I was putting the finishing touches on this opus, intending to ship it off to Rancid Raves Webmaster JeremyLambros on Saturday morning, I (and all other members of NCS) received a self-proclaimed “mea culpa” from Bill Morrison, NCS Prez. Red-faced, he explained that he’d made a mistake in assembling the list of winners in two categories, taking data from preliminary results instead of final results, which included online votes. And the consequence was that he erred in determining the winners in two categories—Editorial Cartoon and Magazine Gag Cartoon. The underlined names in the foregoing list are the actual winners in those two categories. Morrison apologized abjectly: “I’m deeply sorry for any embarrassment or ill will this may have caused any of our nominees or their friends and family members. I hope everyone will understand that this was a case of human error and was in no way underhanded or malicious.” It was, in short, a mistake—in the same class of mistake as a snafu at the Oscar award ceremony a couple of years ago (as Morrison observed). Morrison’s speedy and no-excuses correction is as admirable as his mistake was human. And it changes somewhat my opening tirade: there were 4 of the 15 winners present, not just 3. That doesn’t much change my reaction to the situation, but here’s a revised tirade: AT THE 72ND ANNUAL REUBENS AWARD WEEKEND, May 25-26 in Philadelphia, NCS conferred its 15 annual awards, including the Reuben itself for “cartoonist of the year,” which went to Glen Keane, a Disney animator. Of the 15 winners, only four— only 4!—were present to receive the accolades of their colleagues. Keane was one. The other three were Mark Parisi and Mike Peters and Pat Byrnes. That means 11 of the winners didn’t think enough of the award to show up in case they would win. The number is actually higher than that. There were two winners in one category, and of the 5 nominees for the Reuben, 2 didn’t attend. The revised winners list doesn’t change much the cause of my complaint. The percentage of the winners who showed up changed from 20% to 26%, from a fifth to a quarter. When three-quarters of the winners don’t think enough of the award to attend the presentation ceremony, that doesn’t speak very highly of the regard in which NCS and its awards are held. My complaint, in other words, remains the same.

APART FROM THE AWARDS BANQUET, the Reubens Weekend consists of panel presentations, some stand-up cocktail parties, and a ritual business meeting. This year, 310 people registered for the meeting in advance: 151 of them were members; the other 159, family, friends, business associates. The panel presentations got underway on Friday afternoon with a session on Exaggerating Caricature with panelists Angie Jordan (digital caricatures), Stephen Silver (animation character designer), Ann Telnaes (editoonist for the Washington Post), and Sam Viviano of Mad. Tom Richmond, also of Mad, moderated. They discussed how they amplify and exaggerate. Caricatures “squeeze and stretch,” reported Nell Minow, upon whose reportage I depend for my account because I’m half-deaf (which half? dunno) and can’t hear more than two or three words in succession. A couple of the caricaturists noted that some subjects object very strongly. Said Minow: “Richmond recalled a page he did with the cast members of HBO’s ‘The Sopranos,’ with star James Gandolfini in the center. The producer liked it so much he asked to have a copy, and Richmond said he would be glad to send it, and would appreciate it if the actors would autograph a copy for him as well. It came back with the signatures of the performers in the drawing, except for Gandolfini, who just scribbled a message to the man whose portrait he did not find flattering: ‘Fuck you.’” Next, Jeff Keane traced the history, both personal and professional, of his father, Bil Keane, who created the panel cartoon Family Circus and his two sons who went into cartooning—Jeff, who continues Family Circus, and Disney Legend Glen. Then John Hambrock talked about creating his new comic strip, The Brilliant Mind of Edison Lee, about a kid with an inventor’s brilliant mind. Minow reports: “In the guise of a charming story about a very bright little boy and his friends, Hambrock balances ‘science, social commentary, and super silly.’ A super-bright girl character named after scientist Rosalind Franklin is included to allow for exploration of some gender issues, too.” On Saturday, we were introduced to the second new comic strip recently launched; NCS has seldom devoted much of its program to new strips, so the attention this year was welcomed. Will Henry started us off with a discussion of his new strip, Wallace the Brave. Henry was initially scheduled for Friday afternoon, but the locomotive pulling his train from Maine broke down and he couldn’t get to Philly in time; he was rescheduled for Saturday. Wallace the Brave, it sez on the back cover of the reprint book, “is a whimsical comic strip that centers on a bold and curious little boy named Wallace, his best friend Spud, and the new girl in town, Amelia.” They all live in “a quaint and funky town, Snug Harbor,” where Wallace’s fisherman father makes his living, and his plant-loving mother tends her garden, fending off Wallace’s bug-loving younger brother, Sterling. Henry (whose real name is William Henry Wilson) showed pictures he drew as a child, “from the scratchy crayon drawings of a pre-schooler to the pictures he drew as an eight-year-old, already showing the eye for detail and draftsmanship that would lead him to become a professional comic strip artist,” Minow reports. The strip, she continues, “is inspired in part by his childhood in an oceanside Rhode Island town. It follows a young boy and his friends as they play, argue, have fun, and learn about the world. Henry says the themes of the strip are ‘family, friendship, ocean, nature, kindness.’ It was also in part inspired by the Where’s Waldo books, which give kids so much to look at. ‘I want kids to explore with their eyes.’” Looking at the strip, I’m reminded of the fanciful scratchy drawing in Richard Thompson’s Cul de Sac and of the vague nuttiness of Alice Otterloop, Thompson’s 4-year-old heroine. But Wallace and his friends, being a little older than Alice, aren’t quite as nutty.

The visuals that fill the panels are full of capricious details. The clouds floating above it all are shaped by whimsical curlicues. Birds are always aloft, just ‘v’s in the distant cloud-flecked sky. Random flowers bloom along Wallace’s landscape, and butterflies flit. There’s a talking bird, and the tails of speech balloons sometimes loop around the head of the speaker. Henry clearly enjoys making fanciful pictures. And we enjoy watching the results. The next panel presentation discussed turning static comics into animated tv features— Jerry Scott (Zits and Baby Blues) and Rick Kirkman (Baby Blues), Lynn Johnston (For Better or For Worse) and Bill Griffith (Zippy). Everyone agreed that it was not easy to adapt from the solo role of a strip cartoonist to the group-centered and bureaucratic world of movies and tv. “There was a lot of frustration in being told that what they considered the essence of the worlds they created was not right for a different kind of storytelling,” said Minow. “Pointedly, Lynn Johnston was told that her stories needed to be edgier (Couldn’t Elizabeth, her matronly mother, get a job as a pole dancer?) while Bill Griffith’s Zippy the Pinhead needed to be less edgy (Does he really need to wear a polka dot muumuu?).” “They wanted to de-weird-ize Zippy,” Griffith said. “The panelists said they learned a lot about from the experience,” Minow continued. “For all the frustrations, having to do schematics of their settings, create story arcs, and work with other writers improved their strips. And they enjoyed the envy of writers who were amazed to hear how much freedom they had (Who gives you notes? Uh, no one.)” But the envy abated when writers asked, “And how much time do you get off?” Cartoon strips run every day, which means that cartoonists write and draw every day. No time off unless you work far enough ahead of deadlines to “earn” days off. I took advantage of a break in the program to ask Griffith about his fixation with drawing buildings. Originally, Zippy and Griffy met in picturesque roadside diners with goofy cartoon characters decorating the roofs or being the doorways, but for the last several years, the diners have been ordinary, everyday undecorated buildings, and they show up several times a week. What’s the fascination? As a kid, he told me, he wandered the neighborhood when visiting in Cape Cod in the summer and drew pictures of the houses. Then he sold them to the occupants. Perhaps as a result, he said he finds drawing buildings relaxing. And so he draws lots of them in the strip. A

panel on Women Pioneers of Cartoon Art loomed next— Sandra Bell-Lundy (Between

Friends), Lynn Johnston (For Better or For Worse), Barbara Dale (Dale Greeting Cards, “alternative” i.e., naughty cards), Jan Eliot (Stone Soup), and Cathy Guisewite (Cathy), moderated by Ann Telnaes (editoonist). Johnston

said she began doing cartoons for the ceilings of OB-GYN offices, to give women

something to look at while they were lying on their backs being examined.

Guisewite talked about “food, love, mother, and career” as “the four basic food

groups of her strip,” and her “two-Betty” influences: Crocker and Friedan. The afternoon finished with several cartooners talking about the infestation of cartoonists in Connecticut, the so-called “golden age of cartooning in Connecticut”— Chance Browne (son of Dik Browne; Hi and Lois and Hagar the Horrible), Cullen Murphy (son of John Cullen Murphy; Big Ben Bolt and Prince Valiant), Brian and Greg Walker (sons of Mort Walker; Beetle Bailey, Hi and Lois, and seven other somewhat shorter lived strips; see Opus 379). They all talked about growing up in a community that was all about “cartoons, church, cocktails, and golf,” where all the parents were witty and all the dads could draw, as Minow put it. Murphy showed some of the photos his father took for reference, using himself and his family as models for his very detailed, thoroughly researched drawings of knights, ladies, jousts, and castles in Prince Valiant. On Sunday morning, Rube Goldberg’s granddaughter, Jennifer George, and Ed Steckley talked about the Goldberg legends and their new children’s book, Rube Goldberg’s Simple Normal Humdrum School Day, published by Abrams, whose editorial director for its ComicArts imprint, Charles Kochman, moderated. George talked about the invention contests inspired by Goldberg’s machines for accomplishing simple tasks in many complicated and very funny steps. “There was a murmur of appreciation,” Minow said, “— when Steckley explained that publisher Kochman had insisted that the Goldberg book’s illustrations all had to be hand-drawn,” an increasing rarity in today’s culture of digital drawing. Then a clutch of Mad men (Sergio Aragones, Tom Richmond, Nick Meglin, Grant Geissman and Sam Viviano) wandered through the anecdotal history of the satire magazine and their own connection with it, led by moderator Mark Evanier, who asked provocative questions—among them, When did you first encounter Mad? For most, the answer was “in a friend’s basement.” And most, Minow reports, said it was “a life-changing moment that shaped their idea of humor as inherently and delightfully subversive. “Viviano, Richmond, and Meglin said that what makes Mad’s movie and television parodies work is that the caricatures are all in service to the story.” “Just getting a good likeness of Jack Nicholson is not enough,” Meglin explained. “We don’t need a damn good artist. We need a damn good storyteller.” Viviano added: “It’s not enough to draw a celebrity. Tell the story and get the gags.” They also talked about Mad’s history of ad parodies. “We were making fun of the advertisers,” said Viviano, “not the products.” He noted that advertisers responded, with a new era of self-aware commercials starting in the 1960's. Bill Morrison, the new West Coast editor of Mad was also on the panel, and he talked about bridging the past and future of Mad. “I think about how I felt as a kid discovering Mad. We want readers to have that same sort of thrill. As an illustrator myself, I want artists who make me jealous and kick my butt all the way down the street.” He listed the essentials for any issue of Mad: Alfred E. Neuman, Spy vs. Spy, tv and movie parodies, “A Mad Look At…” some part of American culture, Sergio’s marginal drawings, and the legendary Mad fold-in created by Al Jaffe, the Guinness world record holder as the longest-working cartoonist at age 97. “Without any of those, it isn’t Mad anymore,” said Morrison. He’s looking for the Mad essentials of the future, reported Minow. And while they are still inundated with submissions from people who write, “My friends all say I should be in Mad!” Morrison finds new talent online, “from the smart, funny people who create web comics and funny tweets.” Since

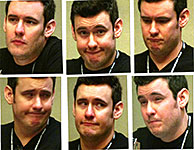

I’m half deaf and can’t hear much of what transpired, I amused myself by trying

to caricature some of the panelists. Most of the results were bad; here are

some of the better ones.

ON SUNDAY

AFTERNOON, many cartoonists attended a “public signing and drawing event” at

the Philadelphia Free Library. This event repeated the autographing party

inaugurated last year: deviating from long custom, NCS opened the Reubens

Weekend to the local populace one afternoon, and cartoonists met their “public”

and sold copies of their books and autographed them. I did, too, both this year

and last; last year, I sold 2-3 books, but this year, only one book and one

caricature. Sunday’s

dinner was devoted to a sandwiches and something called “Pub Quiz,” foisted off

on us by former NCS Prez Steve McGarry and his sons Luke and Joe and

other hangers-on. (Luke and Joe won Silver T-Squares at the tender ages of 18,

becoming the youngest cartooners ever to win the distinction.) Sample questions: Name four women who won the Reuben (Lynn Johnston, Cathy Guisewite, Roz Chast, Ann Telnaes). Then: Name eight people who won the Reuben twice (Milton Canif, Chester Gould, Chic Young, Jeff MacNelly, Bill Watterson, Dik Browne, Pat Oliphant, Gary Larson). Browne is the only one to have won twice, once for each of two strips (Hi and Lois and Hagar).

THE FIRST OF THE WEEKEND’S COCKTAIL PARTIES was on Friday evening, and it was held in honor of Mort Walker, a stalwart member of the Society who died in January. During the evening, the NCS Golden T-Square (given in recognition of spending 50 years as a professional cartoonist) was conferred on Arnold Roth, who has freelanced the entire time, a remarkable achievement.

Only two other Golden T-Squares have been awarded—to Rube Goldberg and to Mort Walker. Shortly after the party began, an announcement revitalized the evening: apparently, the bars were supposed to be “open” (no charge) but because of an administrative error, we’d started off by paying for our drinks by the glass. After the announcement, traffic at the bars increased noticeably, long lines forming immediately.

The second cocktail party inaugurated the Saturday evening’s Reuben Banquet; free drinks. The third, was on Sunday night; cash bar. I observed that glasses of water were going for $5 each at the bar but that the dinner tables were all amply supplied with 16-ounce glasses of water without charge. More about the Banquet in a minute. But first—: The Annual Business Meeting on Saturday morning was marked, as usual, by a long report on the NCS Foundation by its chair, Steve McGarry, leader of the McGarry Clique. (That there is a McGarry Clique is indisputable. That it exists is doubtless due to McGarry’s imagination and energy: he invents more fascinating projects for NCS than anyone else.) I amused myself by watching Jason Chatfield, who, since 2007, has been in charge of an Australian Institution, the Ginger Megs comic strip. Chatfield, as you’ll see, is the man of a thousand faces, and as a member of the Society’s Executive Board, he spent the biz meeting at a long table at the front of the room with the rest of the Board, but Chatfield made faces the whole time—not necessarily in response to anything that was transpiring. Just faces. As though he was amusing himself.

SATURDAY EVENING was devoted to the interminably long Reubens Awards Banquet. There are so many awards that their presentation is divided into two clumps. The first clump features the conferring of a selection of special awards; the second clump consists of the Silver Reuben presentations, ending with the Reuben itself. And I’ve already enumerated those.

The second part of the evening was emcee’d by editoonist Mike Luckovich, who did a good job of restraining his wit. By not telling so many jokes, he kept the evening moving, which is hard to do with so many awards to present. And to further prolong the process, each award is given by another cartoonist, all of whom had to be introduced by Luckovich, all of whom, after getting to the podium, feel compelled to tell jokes and be otherwise amusing. Even after a generous intermission midway through the evening, one’s butt got tired of waiting. But the parade of funny men is doubtless a maneuver devised to mask the fact that a number of winners don’t show up, a trend that has increased over the past few years. Even if we don’t get the dubious pleasure of watching recipients thank their mothers and spouses for something that neither one had done, we can at least have a few chuckles at the presenters. The design of the evening, in other words, is deliberate with ulterior motive—for which we are thankful even if our butt is tired. A comedian named H. Foley emcee’d the first part, during which these awards were presented: Silver T-Square (for service to the profession), to Rick Stromoski and Brendan Burford. Stromoski, a member of the McGarry Clique, is another former Prez of NCS. The presentation to Burford seemed a little self-serving. He’s comics editor at King Features, and giving him an award seemed like currying favor. Besides, it’s his job is to serve the profession. McGarry presented the t-squares after telling funny stories about Stromoski that amused himself so much that on one occasion, he doubled over with laughter. The Ace Award (Amateur Cartoonist Extraordinary) usually goes to a notable or celebrity; this time, it went to CNN’s Jake Tapper, who was, indeed, a cartoonist before he got into the other funny business, journalism. The NCS Medal of Honor was created a few years ago in order to have an award that could be given to those who’ve won the Reuben but continue to live productive lives. (After having achieved the pinnacle, what’s left? The Medal of Honor, of course.) This year, it went to Lynn Johnston. Previous winners are Mort Drucker and Mel Lazarus. The fact that the Society in creating the Medal of Honor acknowledged that it was running out of awards to give is crucial to understanding the organization’s present low rank in the standing of professional organizations. Too many awards makes each one a little less rare. And NCS’s history is a history of a steady expansion of the list of awards.

AS I MENTIONED, the division awards were not on the docket when the National Cartoonists Society began. NCS officially started in 1946 and named its first Cartoonist of the Year the next year—Milton Caniff, creator of Terry and the Pirates (1934-1946) and Steve Canyon which began in January 1947. Since the award presented in 1947 was for achievement in 1946, Caniff was clearly being honored for Terry, not Canyon; but the annals of the Society record him as winning for Canyon (for good reason: why should his honor be connected, officially, to a comic strip he no longer produced?). The award was initiated by Mary DeBeck, widow of cartoonist Billy DeBeck, the popular creator of the comic strip Barney Google and Snuffy Smith. DeBeck died in 1942, and his strip was eventually continued by Fred Lasswell, who kept it going for 55 years. DeBeck’s long-grieving widow wanted to perpetuate the memory of her husband and offered to provide a trophy if NCS were to institute a “cartoonist of the year” award. NCS went along with this plan without giving it much thought. Caniff told me that Mrs. DeBeck picked the winner every year; there was no official selection process. If true—and I have no reason to doubt Caniff, however outlandish his contention seems now—Mrs. DeBeck did a pretty good job of picking. After Caniff, the winners of the Billy DeBeck Memorial Award were Al Capp (Li’l Abner), Chic Young (Blondie), Alex Raymond (Rip Kirby, Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim), Roy Crane (BuzSawyer and Wash Tubbs/Captain Easy), Walt Kelly (Pogo), Hank Ketcham (Dennis the Menace) and Mort Walker (Beetle Bailey)—eight champion cartoonists on anyone’s list of the top ten. They each received a silver cigarette case engraved with the characters DeBeck made famous in his comic strip, Barney Google. In consequence, the trophy was sometimes called the Barney. Mrs.

DeBeck died in a plane crash in 1954, and NCS decided to re-name its Cartoonist

of the Year award in honor of its first president. And the new trophy was pure

Goldberg. In fact, it was cast from a sculpture that Rube himself made. A

whimsical creation by the man who had made his name synonymous with outlandish

inventions, it consisted of a comical pile of male nudes, traditional cartoon

characters, who had attempted, apparently, to form a human pyramid and had

enjoyed some success in the attempt— as much success, that is, as any Golderg invention

ever achieved. Goldberg didn't create the sculpture to serve as the NCS award: when he made it, he thought he was making a lamp. The light bulb screwed into the posterior of the uppermost figure. Happily, when NCS member Bill Crawford saw this objet d'art in Rube's home at just about the time the Society was looking for a trophy for the Reuben, he recognized at once that Goldberg's lamp was destined for greater things. He made a cast for the trophy and substituted a bottle of ink for the light bulb. The first to receive the Reuben in all its glory, trophy and fanfare, was the sports cartoonist Willard Mullin, who was named cartoonist of the year in 1954. Rube received the trophy named for him in 1967, three years before he died. (The eight cartoonists who had won the Billy DeBeck Award for the years 1946-1953 were subsequently presented with Reuben statuettes and are termed Reuben winners in the annals of the Society.) For the first 9 years of its history, the Cartoonist of the Year was the only award the Society gave. By 1955, NCS became acutely aware that it was, inadvertently, overlooking achievement in various arenas of cartooning endeavor. Starting in 1956, it awarded the first division awards for achievement in Comic Books, Magazine Gag Cartooning, Editorial Cartooning, and Advertising Illustration. Since the Cartoonist of the Year was, until Mullin won, a syndicated comic strip cartoonist, no one felt the need to create a division for this category. Until 1957, when Humor Comic Strip as well as Animation and Sports Cartoon were added to the list. And then in 1960, realizing that humor comic strips were not the only comic strips in the newspaper, NCS created the Story Comic Strip division award. Five years later, the Special Features division was created. Looking at a list of the winners, it’s impossible to say what “special features” were. The first winner, Jerry Robinson, won for a newspaper panel of illustrated word play— Flubs and Fluffs. Then Hal Foster won for the next couple of years with Prince Valiant. Wait—isn’t that a comic strip? Many of the subsequent winners in this category won for panel cartoons. Although not all. Al Jaffee won for Mad fold-ins, and Mort Drucker won for his movie parodies in Mad and Don Martin for his Madnesses. NCS waited almost ten years—until 1976—before creating a division award for Magazine and Book Illustration, which, in 1999, was divided into two categories. In 1989, a new category, Newspaper Comic Strip, combined Humor and Story. The nineties were full of invention: in 1991, Greeting Card; in 1994, Newspaper Illustration; in 1995, Animation was divided into two divisions, (Theatrical) Feature and Television. In 2000, a category was added for animated editorial cartoons and the like, New Media. In the next few years, the New Media trend was again confirmed with the creation of divisions for Graphic Novels, and Online Short and Long Form features. Unfortunately, all the expansiveness took a toll. Motivated by the laudable desire to be inclusive, NCS increased the number of its awards, and the more there were, the less each of them meant to cartoonists. And to the general public, much of which undoubtedly didn’t recognize all the special categories anyhow. Newspaper comic strips and comic books were doubtless all the cartoons there are in the popular mind. So NCS has wound up giving awards to practitioners who don’t value them for cartooning endeavors that the consuming public is wholly ignorant of. To compound this inadvertent error, NCS began about 20-30 years ago denying the press access to the Reuben festivities. The press reacted appropriately: it stopped reporting the winners, which only added to the dilemma of invisibility. And then NCS closed the Reubens Weekend to any non-professional visitors: the public was kept out because the fans who came pestered cartoonists for autographs. And that interfered with the cartoonists’ supposed desire for fun and games beyond public scrutiny.

Next year at Huntington Beach, California, the Society is taking a step to remedy the situation. Inspired, perhaps, by the success last year and this of the autographing party held on one afternoon, the Reubens Weekend in 2019 will become a “festival,” an adventure embarked upon probably because Steve McGarry endorsed the idea (and perhaps came up with it). And the press and the public will be invited. Maybe the Society’s long irrelevance will, at last, begin to evaporate. Until then, we have one more souvenir of the weekend.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||||||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |