|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 365 (May 6, 2017). We planned to get this installment posted a week ago. And it was, at that time, a short and sweet opus. But Fate conspired against us. Just as we were wrapping up the tidy package, fresh news broke, and we, ever conscientious and dutiful, scrambled to record it. This always happens to us: late-breaking news suddenly surfaces, and our best laid plans gang aft agley, as Robbie Burns would say. The Trumpet kept doing new idiotic things, so we altered and added to what we’d already written. Then Bob Mankoff announced, just the day after leaving The New Yorker, that he was becoming humor and cartoon editor at Esquire. Added that. Then a day after that addition, more information about his move arose. Added that. Then we found what Playboy had to say about Jack Ziegler. Added that. Then more information about cartooning in distant countries with repressive regimes popped up. Added that. Syrian cartoonists are still at it. Added that. Every time something new happened, we had to add a little moron. To wit— Hare raising news of the month about the Marvel artist who snuck politics into a comic book; Bob Mankoff, former cartoon editor at The New Yorker, going to Esquire the day after he moves out of his office; new cartoon format at The New Yorker?; the Denver Independent Comics and Art Expo; several reports on repression of cartoonists abroad and (even) here, women cartoonists cracking the ceiling, classic look revived at Archie, how Staton and Curtis got the Dick Tracy gig, plus reviews of a new analytic book about Batman, an expanded biography of Will Eisner, and graphic novels Eisner’s A Contract with God (revisited) and Blacksad. And notes about comic books Snotgirl, Tank Girl, I Hate Fairyland, All Star Section Eight, Grass Kings, and American Gods. Not to mention our continuing examination of the evils of Trumpery. We’ll post the complete list in a trice.

MEANWHILE, WE’VE SUCCESSFULLY NEGOTIATED another Easter, dying eggs and indulging a species of cannibalism by eating chocolate bunnies. We look forward every year to the arrival of this holiday, hoping that this year, we’ll see the Easter Bunny suitably attired in red short pants, white three-finger gloves, and giant yellow shoes. Our hope, of course, is in vain: the long-eared leporidae re-appears faithfully in fur and only fur from head to paws. Our church is surrendering to a weird brand of political religious correctness: they’ve started calling Easter by another name—Resurrection Sunday—because, I assume, Easter is a word with a pagan (or at least non-Christian) history that the Passionate Faithful wish to shed. Naturally,

I deem this effort as not only misguided but misbegotten. “Easter,” the word as

well as the holiday, has a history, and to consign the word to Limbo is to deny

history—which, in this case, seems to me like denying the religion And now, to enable you to pick just those articles you want to spend time on and skip the ones in this massive installment of Rancid Raves that are of little interest to you, here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Morin Gets Pulitzer Mankoff Lands at Esquire DINK Does Well Marvel Artist Does Politics in X-Men Marvel Diversity Turns Readers Off? Turkish Cartoonist Faces Jail Sentence Zunar Wins One Another Seditious Malaysia Cartoonist Syrian Cartoonists Continue the Fight

Censorship in U.S. Alive and Well Trumpest at the Border Stops Cartoonist New Cartoon Format at The New Yorker Humor Times Is 26 Classic Look Lives On at Archie Comics Sales Chartoon at Time

Odds & Addenda Lucky Luke is 70 Looney Tunes at DC Free Comic Book Day, May 6

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews and Comments on—: Snotgirl Tank Girl I Hate Fairyland All Star Section Eight Grass Kings American Gods

WOMEN CARTOONISTS ASSAULT CEILING More and More

EDITOONERY Trumpery All Over The Evils Thereof Sampling the Best Editorial Cartoons of the Month

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Comic Strip Antics

THE SPIRIT JOINS TRACY TO FIGHT CRIME The Crossover and— How Staton and Curtis Got the Tracy Gig

BOOK MARQUEE Mad about Trump

BOOK REVIEWS Long Reviews Of—: Caped Crusader: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture Will Eisner: A Spirited Life, Deluxe Edition

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Reviews of Graphic Novels—: A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories: Centennial Edition Blacksad: A Silent Hell

PASSIN’ THROUGH Jack Ziegler

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

MORIN GETS THE OTHER HALF OF HIS SET OF BOOKENDS Two decades after Jim Morin won his first Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning, the Miami Herald veteran now has a matching bookend reports Michael Cavna at the Washington Post’s Comic Riffs. And he goes on—: Morin, who joined the Herald in 1978, was named the winner of the 2017 editorial cartooning Pulitzer on Monday, April 10, for a portfolio that “delivered sharp perspectives through flawless artistry, biting prose and crisp wit,” according to a five-person jury. Morin called the honor “very satisfying” — especially because, he told Cavna, “I’m always dissatisfied with what I do, and keep trying to change and explore to improve the drawings.” His

winning cartoons ranged from the 2016 presidential campaign to restroom

politics to the Flint, Mich., water crisis. Samples herewith. Morin, a Syracuse alum who was born in Washington, was a Pulitzer finalist in 1977 — the year before he joined the Herald — and again in 1990. He first won the Prize in 1996. “It’s amazing to be honored toward the end of your career,” he said. Morin’s trophy shelf includes the 2007 Herblock Prize, the 2000 Fischetti Award and the 1999 Thomas Nast Society Award. The 2017 finalists were past Pulitzer winner Steve Sack of the Star Tribune (Minneapolis) — who last month won the Overseas Press Club’s Thomas Nast Award — and past Herblock Prize recipient Jen Sorensen, who is a freelancer. The Pulitzer jury included two cartoonists — 2014 Pulitzer winner Kevin Siers of the Charlotte Observer and 2015 Pulitzer winner Adam Zyglis of the Buffalo News — in addition to three other journalists.

MANKOFF LANDS AT ESQUIRE Late-Breaking News, Kimo Sabe! One day after his last day at The New Yorker, Bob Mankoff accepted a job at Esquire—as cartoon editor, the position he filled at The New Yorker for almost 20 years. “Cartoon and humor editor,” as the position is styled, is a new one at the Hearst-owned men’s glossy. According to Hearst, reported Alexandra Steigrad at wwd.com, Mankoff will be responsible for “reviving the decades-long tradition of cartoons in Esquire,” which published more than 13,000 cartoons dating back to the 1930s. (For more about the founding of Esquire, visit Harv’s Hindsight about E. Simms Campbell in May 2013.) For years, Esquire’s full-page color cartoons rivaled The New Yorker’s expansive treatment of the medium and were the envy of cartoonists nation-wide even if they did not aspire to be published in the men’s magazine. “Mankott will edit humor stories, pitch ideas, draft cartoons and recruit a new generation of humorists to Esquire and Esquire.com,” said Steigrad. “He will also find ways for the magazine to make its original cartoons available for prints and licensing,” which is what he did when he created the Cartoon Bank that, later, The New Yorker bought from him (a condition of the sale being that Mankoff be named cartoon editor—see March 2017 Hindsight on Mankoff; dunno what he finagled at Esquire). “Bob is one of the funniest, most creative people I know,” said Esquire editor-in-chief Jay Fielden. “What he’s going to do is invent an entirely new look and sensibility in cartooning by upping the aesthetics and embracing a wide set of fresh voices. ‘La La Land’ proved an old form can become a new sensation. That’s the ambition here.” Mankoff, as we might expect, is eager to begin and, as a student of magazine cartooning, appreciative of the role Esquire played in the development of the single-panel magazine cartoon. “Esquire was home to some incredible cartoonists and humorists over the years, and it’s a real thrill to be able to reintroduce and reinterpret that legacy for a new audience,” Mankoff said. But he won’t be doing it by using the “open door” policy he followed at The New Yorker. “That selection process,” Mankoff told Michael Cavna at the Washington Post’s Comic Riffs, “is delusional.” The policy permitted cartoonists—even unknowns—to submit cartoons face-to-face with Mankoff, an encounter that often ended in swift rejection. Each line drawing effectively got only an instant audition, so even promising gags that didn’t quite “sing” right then and there were quickly rejected. Mankoff now believes there’s a better way to nurture good cartooning that just leaving the office door open to all comers. “It’s important to use these editorial muscles that I’ve developed over all these years,” said he. “I want to try something new,” Mankoff said. “I’ve had this idea for a long time, but in the New Yorker context, it didn’t make sense.” Probably because at The New Yorker, he was working with a significant number of long-time contributors, all experienced enough to turn up their noses at the scheme he’s now contemplating. He imagines his new approach could “reinvigorate the ecosystem of magazine cartoons.” His new idea: what if he were to work closely with a handful of different cartoonists every issue, in a process that he says would “feel less hierarchical” and “more productive”? His goal is to spotlight each humorist’s voice by helping them to develop their material. Mankoff wouldn’t work just with artists, but also performers. “I want stand-up comedians to work with cartoonists, too, to [explore] what a stand-up sensibility could be in a magazine.” That collaborative approach, he notes, is more like what The New Yorker was still doing a half-century ago, when illustrators and gag writers might be paired on a cartoon. And given today’s technology, you can collaborate in “a virtual writers’ room” — one in which a stand-up like Pete Holmes, he says, might work with cartoonists like Alex Gregory and Matthew Diffee, who grew in prominence within the pages of the New Yorker. “Combining different skill sets could be very powerful in … heightening the quality of humor,” Mankoff says. “That’s my ambition through collaboration, and that’s [new Esquire Editor in Chief] Jay Fielden’s ambition, too. I’ve known him since 1997. We go back a long way, and we have a great working relationship.” “I look forward to working with new talent, too. It will be a commission process, essentially, like working together on an article,” Mankoff says. “We will all have skin in the game, writers can be emboldened — and my door is open.” While Mankoff’s plan seems novel, it actually isn’t all that new. As he observes himself, his idea harkens back to the way The New Yorker worked on its cartoons for the first 25-30 years. It was an approach “that began to lose favor in 1952, when William Shawn [became editor and] began encouraging the magazine’s artists to develop their own voice rather than to rely on gagwriters,” observed Michael Maslin at his Inkspill blog. “While using gagwriters is still an approach employed by a very small number of New Yorker cartoonists,” Maslin continued, “it has been largely out of favor at the magazine since the early 1970s. Roz Chast, in a brochure for an exhibit of New Yorker cartoons, wrote that she felt the use of gagwriters was ‘like cheating.’” Not only were many of the cartoons drawn to captions supplied by others (E.B. White and James Thurber famously wrote and re-wrote lots of captions), but the weekly “art meeting” at which cartoons were selected for the next issue was a collaborative enterprise “wherein a number of editors and Rea Irvin, the magazine’s first ‘art supervisor’ joined in on helping sharpening the work,” said Maslin. “When Shawn was appointed editor, he abandoned that collaborative effort.” Maslin said it will be “fascinating” to see how Mankoff’s “retro-collaborative approach plays out in the pages of Esquire.”

Maybe Mankoff secretly believes that his plan will help insinuate cartoons into magazines that don’t, at present, use them. A real revolution, in other words. Nearby, we post Mankoff’s cartoon about his voyage to Esquire in which he wants us to notice his deployment of the cliche desert-island setting, “a visual signal,” Cavna said, “that he hopes to move away from [such classic cliche] cartoon tropes.”

DINK DOES WELL Just got back from attending and exhibiting at the 2nd annual DINK. D-I-N-K, as nearly as I can figure it, stands for "Denver INdependent ComiKs & Art Expo"— or some such designation. Took place this year in a larger venue than last. I don’t have any actual attendance numbers, but good-sized crowds both days, Saturday and Sunday, April 8-9. Could be an impression, though, brought on by the narrow aisles: the narrower the aisles, the more they seem to be full of people even if the number of people isn’t that great. No matter: I had a good time and sold a goodly quantity. DINK is a happy comics craft show: lots of graphic novels of all sizes and quality (many surprisingly very well done by unknown creators) and a noticeable infiltration of tables at which jewelry and other craftiness were displayed and sold. No movie stars. No Hollywood promo for the latest superhero flick. No games. And no cosplay to speak of. Well, one cosplay: it was billed as the 27th International Dog Cosplay Championship. That, of course, was entirely made-up: this was the first of these canine costume competitions, a not-too-subtle satiric comment on the whole cosplay excess of recent years. A vivid display, we might say (wincing all the while), of what happens when wearing a costume goes to the dogs. The tabletop exhibit was distributed on two floors, the second and third; panel presentations took place on the first floor. I was on an aisle that cornered at a 3-table lashup for the Bros Hernandez, one of whom, Mario, came by and bought a copy of my Accidental Ambassador Gordo, Gus Arriola's memorable strip about a Mexican bean farmer turned tour guide. Next to them, Denis Kitchen held forth and later, with Mario Hernandez, led a cannabis tour. Other notables included Amy Reeder, Tony Millionaire, Andrew McLean, and Sucklord selling toys next to the ForeverScape art installation. The latter is a continuous drawing that Vance Feldman began in 2009. “Since then,” according to the placard posted near the display, “the ForeverScape has grown to over [the equivalent of] 1,200 pages.” But the pages are laminated (for want of a better word) together in one long strip, which was displayed on an ingenious “playback” device, designed and engineered by Feldman: the strip rolls off one roller on the right, slips across the display area on top of a “table,” then rolls around and under the table onto another roller at the other side. For seven years, Feldman has worked on it every day at the rate of about half-a-page a day. It’s “seven years and still growing, longer than the Titanic but still afloat.” Says Feldman: “It goes on until I do.” You can see the artwork at ForeverScape.com, but for a glimpse of what was on display at DINK, see the accompanying photos.

As you can see in the array of pictures, I inaugurated a new product—namely, a Starbright coffee mug. These go for $22, including postage; and you get a copy of a 4-page Zero Hero comic strip, which explains who Starbright is. To order one, go back to the gateway page and scroll down to the bottom, where you’ll find, under my self-caricature, “send email to R.C. Harvey”; click on that and when I get your message, I’ll respond with ordering information. This offer may show up again from time to time; but maybe not. Don’t miss out. My grandson and his mother (my daughter) came down on Sunday, and he went bananas over graphic novels, stoking up a full bag of them. In other words, a good time was had by all—without movie actors or people dressing up in costumes. And without superheroes. As BleedingCool put it: “This is truly a convention for people who love underground and independent art, comics and ’zines.” And tattoos. Everyone there loves tattoos. They all had at least one tattoo. I spent most of my time between visiting with customers trying to find among the passersby someone without a tattoo. Not much luck.

MARVEL ARTIST SNEAKS POLITICS INTO HIS PICTURES And Gets Fired For It April was an exhausting month for comics gossip and scandal, chief among the disturbances— Marvel’s termination of its contract with Indonesian artist Ardian Syaf because he slipped religious and political allusions into X-Men Gold No.1. “Nos.2 and 3 with his art are already at the printer and will be shipped with his art,” reports Milton Giepp at ICv2. Art for Nos. 4, 5, and 6 will be provided by RB Silva, and for Nos.7-9 by Ken Lashley. The most notorious case of a cartoonist slipping hidden messages into his artwork is that of Al Capp, who hid erotic images in his comic strip, Li’l Abner. (For the details, see Harv’s Hindsight for January 2013.) While there have been other instances of similar pranking in comic books (we’ll tell you where, down the scroll), nothing compares to the scandal Syaf incited. Bleeding Cool started the X-Men Gold brouhaha by reporting that Syaf had included in art for the first issue of X-Men Gold references to Quranic passages freighted with political significance in his home country of Indonesia The references themselves are doubtless so obscure that editors and audiences in the U.S. failed to notice them, said R. Orion Martin at hyperallergic.com. “For instance, in a scene where the X-Men are playing baseball (perhaps the most wholesome category of standby X-Men scenes), the character Colossus is wearing a T-shirt that reads ‘QS 5:51.’” Later

in the comic, Kitty Pryde’s head partially obscures a sign on a Jewelry store

so that “Jew” is more visible than the rest of the word. Pryde is Jewish. On a

neighboring store, the numbers “212” appear. QS 5:51 refers to Surah 5, verse 51, a controversial passage in the Quran that has assumed a special weight in the contemporary political scene in Indonesia. According to Rich Johnston at bleedingcool.com, the verse translates into English: “O you who have believed, do not take the Jews and the Christians as allies. They are, in fact, allies of one another. And whoever is an ally to them among you—then indeed, he is one of them. Indeed, Allah guides not the wrongdoing people.” The passages are taken by some as prohibiting the ruling of Muslims by Christians or Jews. A common interpretation of the verse, says Johnston, is that “Muslims should not appoint the Jews and Christians as their leader,” the meaning that most assumed was intended by the governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (often called Ahok), who said last September during his reelection campaign that his opponents were improperly using verse 51 of the Quran to claim that Muslims should not vote for him because he is a Christian, the first of that persuasion to be governor. Indonesia has the has the largest Muslim population in the world and was, at the time, engaged in social/political upheavals that became more heated after Ahok’s remarks. The comment provoked a tremendous public outcry, reports Martin, and “on December 2, more than 200,000 Indonesian protesters called for Ahok to be tried for blasphemy under Indonesia’s laws against insulting religion. The widespread protests were seen not only as a criticism of Ahok, but as a sign of Islamist groups’ growing strength in the country. Al Jazeera’s Step Vaessen described the protests as ‘a threat to the secular state here in the long run.’” Syaf had attended at least one of the protests, which he memorialized in the comic book by lettering that number 212 (2 December) on a store front in the background. It is assumed that this maneuver indicates his support for the hardline movement to criminalize Ahok. Upon Bleeding Cool’s revelation over the weekend of April 8-9, Marvel issued a statement, saying that none of the writers, editors or “anyone else at Marvel” knew the meaning behind the allusions hidden in plain sight.” The allusions “are in direct opposition of the inclusiveness of Marvel Comics and what the X-Men have stood for since their creation. This artwork will be removed from subsequent printings, digital versions, and trade paperbacks and disciplinary action is being taken.” Almost immediately thereafter—virtually simultaneously— Syaf was fired. SYAF, WHO IS DESCRIBED by Gail Simone, who worked with him occasionally (mostly through an interpreter), as “pleasant to work with ... humble and nice ... super shy and polite,” sought to explain himself, but the more he explained, the deeper he dug the hole he was in. He denied he was anti-Semitic or anti-Christian, saying in one Facebook posting, that “I don’t hate Jew or Christian. I worked with them in 10 years ... a lot of good friends, too.” (He is not fluent in English.) Syaf claimed his allusions did not advocate religious intolerance, posting that the Surah number “is the number of JUSTICE. It is number of LOVE.” He said the verse QS 5:51 is “very special to me. I want to put it in my work.” On another occasion, he posted what some interpret as an anti-Semitic remark: “But Marvel is owned by Disney. When Jews are offended, there is no mercy. My career is over. It’s the consequence [of] what I did, and I take it. Please no more mockery, debate, no more hate. I hope all in peace.” But Syah seems to have contradicted himself. Interviewed by the Jakarta Post, Syaf said being friends with Jews and Christians is acceptable, “but choosing a non-[Muslim] as a leader is forbidden. That’s what the verse says. What can I do as a Muslim? ... If I worked at DC, I could put [the message] in a Superman comic book.” Moreover, he had posted (and later removed) a photo on Facebook showing him posing with the leader of the hardline Islamic Defenders Front FPI, an Islamist organization in Indonesia, known for hate crimes and religious-related violence and one of the groups behind the 212 marches. “Syah says that after the controversy blew up,” Johnston reports, “he received an invitation to meet, which he accepted.” And this isn’t the first time Syah has used backgrounds in his drawings to support his beliefs, Danuta Kean said at theguardian.com. “A 2012 issue of Batgirl contained a reference to Indonesian president Joko Widodo in support of his campaign at the time to become governor of Jakarta.” Nor is Syah the first to sneak extraneous messages into comic books, Johnston reported. “Ethan Van Sciver did a whole issue of New X-Men hiding the word ‘Sex’ in the bacground. Al Milgrom lettered a mocking message into a comic when Marvel EIC Bob Harras was fired. And there was the time a production artist drew a penis on Bucky in a classic Captain Americ archive reprint.”

BUT THAT WAS ALL JUST FOOLING AROUND. This time, the consequences could be far-reaching, especially considering the international circulation of Marvel comics generally, and X-Men titles in particular. Martin lays it out (in italics)—: The story of Syaf’s inclusions didn’t erupt into controversy because fans were excited about the references to contemporary Indonesian politics, but rather because of the way it played into the contentious contemporary discourse [in the U.S.] on Islam. The headline-grabbing news of a foreign Muslim artist inserting anti-Semitic, anti-Christian political messages into X-Men comics resonates because certain elements in the current administration view contemporary politics as a clash of civilizations. The fact that the X-Men have a history of being used to comment (somewhat problematically) on diversity and oppression only increases the cultural reach of the story. This is the second time in recent months that Marvel has been pitched into a controversy around issues of political correctness. Explaining an ongoing slump in sales, Marvel vice president David Gabriel made some clumsy statements about the weak showing being due to the company’s new roster of more diverse characters. “What we heard was that people didn’t want any more diversity,” the damning quote read. “They didn’t want female characters out there. That’s what we heard, whether we believe that or not.” See next story, below.—RCH The sentiment is, on the face of it, ridiculous, as Marvel’s diverse titles are among its bestselling comics — Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Black Panther was the top-selling comic of 2016. As Alex Abad-Santos explained, the context for Gabriel’s statement is the entirely backward system of comics distribution, whereby retailers order comics without seeing them and are unable to return them if they go unsold. This system privileges known commodities while sidelining emerging artists and untested content. Gabriel was echoing the voices of retailers and some communities of longtime fans who were less than enthusiastic about Marvel’s increased focus on non-traditional (read: not white male) characters. Both recent scandals point to the emergence of Marvel as a global cultural juggernaut and the accompanying growing pains of its rise. Long gone is the era in the mid-1990s when a bubble in the comics market nearly bankrupt the company. While Marvel Comics still operates as a comic-selling business, its true value to the Walt Disney Company, which acquired it in 2009 for $4.24 billion, is the Marvel Cinematic Universe, a well-oiled machine that now produces three to four blockbusters per year. In its more Machiavellian moments, the company makes clear that it sees the comics more as content incubators for movies and video games than valuable products themselves. This was the case when the company canceled the Fantastic Four series, in part because it does not own the rights to those movies. Superhero comics are now global products in both their production and consumption. Marvel draws on an international pool of artists, and in that sense, the scandal around Syaf’s messages echoes the “iPhone Girl” scandal surrounding a Chinese Foxconn worker who took selfies with an iPhone that were later sold in the US. Like Apple products, mainstream comics are less and less associated with the individual artists and writers who work on them (can you imagine the designers of an Apple computer stamping their signatures into the inside of the case?) and more with the corporate branding and franchise-extension directed by the companies that own them. After all the chatter around Syaf’s drawings has died down, one of the few lasting effects of the controversy will most likely be that it will be harder for Muslim artists and writers to work for conflict-averse cultural behemoths like Marvel. As G. Willow Wilson, the creator of Marvel’s popular Muslim character Kamala Khan, writes: “Ardian Syaf can keep his garbage philosophy. He has committed career suicide; he will rapidly become irrelevant. But his nonsense will continue to affect the scant handful of Muslims who have managed to carve out careers in comics.”

MARVEL VP GOOFS SAYING DIVERSITY TURNS READERS OFF Marvel’s vice president of sales has blamed declining comic-book sales on the studio’s efforts to increase diversity and female characters, reports Sian Cain at theguardian.com. Speaking at the Marvel retailer summit about the studio’s falling comic sales since October, David Gabriel told ICv2 that retailers had told him that fans were sticking to old favourites. “What we heard was that people didn’t want any more diversity,” he said. “They didn’t want female characters out there. That’s what we heard, whether we believe that or not.” Over recent years, Cain continued, “Marvel has made efforts to include more diverse and more female characters, introducing new iterations of fan favourites including a female Thor; Riri Williams, a black teenager who took over the Iron Man storyline as Ironheart; Miles Morales, a biracial Spider-Man and Kamala Khan, a Muslim teenage girl who is the current Ms Marvel.” To his indictment, Gabriel added: “I don’t know that that’s really true, but that’s what we saw in sales … Any character that was diverse, any character that was new, our female characters, anything that was not a core Marvel character, people were turning their noses up.” Said Cain: “Gabriel later issued a clarifying statement, saying that some retailers felt that some core Marvel heroes were being abandoned, but that there was a readership for characters like Ms Marvel and Miles Morales who ‘ARE excited about these new heroes,’ adding: And let me be clear, our new heroes are not going anywhere! We are proud and excited to keep introducing unique characters that reflect new voices and new experiences into the Marvel universe and pair them with our iconic heroes. “‘We have also been hearing from stores that welcome and champion our new characters and titles and want more! … So we’re getting both sides of the story and the only upcoming change we’re making is to ensure we don’t lose focus [on] our core heroes.’” Online, Cain said, “readers scorned Gabriel’s remarks [as sufficient explanation for sales slump], pointing to Marvel’s tendency over the last few years to focus on restarting and rebooting storylines, creating a complicated web of interwoven universes, as well as an overwhelming output that fans struggled to keep up with.” G. Willow Wilson, writer of the Kamala Khan Ms Marvel series, responded to Gabriel’s comments, saying that “diversity as a form of performative guilt doesn’t work” and criticizing Marvel’s tendency to introduce the new iterations of fan favorites by “killing off or humiliating the original character … Who wants a legacy if the legacy is shitty?” She continued: “A huge reason Ms Marvel has struck the chord it has is because it deals with the role of traditionalist faith in the context of social justice, and there was— apparently— an untapped audience of people from a wide variety of faith backgrounds who were eager for a story like this. Nobody could have predicted or planned for that. That’s being in the right place at the right time with the right story burning a hole in your pocket.” One retailer told ICv2 that increased diversity had brought a new clientele to his store. “One thing about the new books that go through my store, they don’t sell the numbers that I would like,” he said. “They do bring in a different demographic, and I’m happy to see that money in my store.”

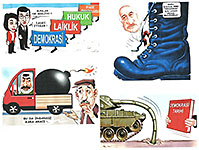

TURKISH CARTOONIST MIGHT BE JAILED FOR 29 YEARS Five months after Turkish political cartoonist Musa Kart was arrested along with several of his colleagues from Cumhuriyet newspaper on suspicion of supporting Kurdish militants and the Gulenist movement, they finally were formally indicted last month, according to a press release from Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI). If convicted, Kart could face up to 29 years in prison. The charges specifically against Kart are “helping an armed terrorist organization while not being a member” and “abusing trust.” Organizations that advocate for press freedom, including the International Press Institute and the Committee to Protect Journalists, say that the charges are baseless and simply provide cover for President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to silence accurate coverage of his regime. In total, Turkey is currently holding 141 journalists behind bars, most of them arrested in the months since the failed coup last summer; 19 Cumhuriyet staffers possibly face jail terms of up to 43 years. Turkey's oldest national daily newspaper, the staunchly secular Cumhuriyet daily has been a thorn in Erdogan's side in recent months as the president sought (successfully in the April 16 referendum) to expand his powers. The paper’s former editor-in-chief Can Dundar was last year handed a five-year-and-10-month jail term and has now fled Turkey for Germany over a front-page story accusing the government of sending weapons to Syria. A

brief glance at Kart’s cartoons reveals the truth about his political stance:

like almost all cartoonists, his chief concern is scrutiny of those in power,

whoever they may be. The cartoon at the upper left in our visual aid was published after last summer’s attempted coup. It puts Erdogan’s words after the collapse of the attempt into the mouth of his exiled opponent and the alleged mastermind behind the coup, Fethullah Gulen. “What are these waiting fore?” says the man; “Restoration of honor,” says the woman. Kart’s ironic maneuver strenuously suggests that the two men, Erdogan and Gulen, are kindred political souls. “Critics of the Gulen Movement,” said CRNI at its website, “consider it a cult of personality and similar observations can be made about the Erdogan regime.” Next around the clock, Kart depicts Gulen as an infiltrator of the Turkish miliary, who says: “Date 12 September 1980—we have found suitable ground to climb up.” In the next two cartoons, Kart derides those who would overturn democracy or suppress freedom by force, be they terrorists, insurgents or military forces. The tank encounters a book, the title of which is History of Democracy. The speaker in the other says: “And this is the unmanned land vehicle.” The CRNI website observes that Erdogan has attempted to silence Kart twice before—first when Erdogan was prime minister and then as president. “After successfully defending his right to freedom of expression in court against a thin-skinned head of government, Kart received our Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award. It is clear that under the emergency powers deployed since last July, the president has taken the opportunity for revenge on a cartoonist he has long despised.” Following news of the indictment last month, CRNI Executive Director Robert Russell issued a statement that read in part (in italics)—: We absolutely condemn this embarrassing effort on the part of the Turkish government to further disappoint its own people. This indictment should be quashed and put on a shelf to gather dust. It is not worthy of the people of Turkey. Every freedom loving country in the world should watch events in Turkey with care and see how an apparent slide into tyranny has continued step-by-step over time with apparent ease and impunity. This can happen in any country when freedom of speech, especially investigative and critical journalism, is throttled and the court system’s independence is eliminated. Turkey’s judicial system has not yet announced any trial dates for Kart and his colleagues, who have already been held without bail since November. We will be watching closely and provide updates as news develops! Since the arrest of many of its staff, Cumhuriyet has continued to publish the sections of the jailed columnists but with a blank space as they are not allowed to write in prison. According to the P24 press freedom website, most of the 141 journalists behind bars in Turkey were detained during the state of emergency imposed after the failed coup last July. Critics have accused the government of using the state of emergency to crack down on all forms of opposition. Turkish authorities insist that those held are jailed for crimes other than their journalism.

ZUNAR WINS ONE In Malaysian cartoonist Zunar’s on-going struggle with his country’s government—they accuse him of sedition because his cartoons criticize policies and personalilties—he reports he’s won one. When the police raided his studio in 2010, they confiscated the original art for a cartoon and a supply of Zunar’s book, Cartoon-O-Phobia. Zunar sued to get his property back, and, after legalistic foot-dragging that has lasted since (seven years!), both the books and the artwork were returned—but the latter was “badly damaged.” Zunar sued again for damages, and, again after predictable delay, the court ordered the government to pay about $4,000 as compensation for destroying the cartoon. The cartoonist said the action was “a lesson to the police and the Malaysian government that using criminal law arbitrarily to confiscate and destroy cartoon works is unacceptable and was done in bad faith. It is also a clear proof that my book’s title, Cartoon-O-Phobia, is a right word to describe the character of the Malaysian government.” Zunar expects to have to sue again to regain over 40 of his cartoons currently in the possession of the police since November 2016—and some 1,300 books which, like the artwork, were confiscated on one of the several raids conducted at his studio. They were taken because the police thought they were “detrimental to parliamentary democracy”—seditious, in other words.

More Trouble in Malaysia. Zunar isn’t the only Malaysian cartoonist accused of sedition for doing cartoons that ridicule authorities. Fahmi Reza, a graphic designer and activist, drew prime minister Najib Razak as a clown, effectively asserting that the country is subject to a “cartoon government” because Najib allegedly diverted $700 million from a government investment fund into his own personal bank account. Fahmi felt that the prime minister’s corruption made his homeland into a laughing stock for the whole world. If convicted, Fahmi cold face up to four years in prison, but his case is not likely to be resolved soon: like Zunar, Fahmi has been waiting for a long time. For all the details, visit cbldf.org.

SYRIAN CARTOONISTS CONTINUE THE FIGHT By Maren Williams at cbldf.org Six years after Syria’s uprising began, the future of the country is far from certain. But one surprising result of the turbulence is already apparent: an abrupt flowering of cartoons, comic magazines, and animated shorts spreading mostly through rebel-held areas and refugee camps. The website Syria Untold recently featured a selection of the sequential art and artists making inroads in the war-torn nation, where they must defy repression both from the government and from the Cutthroat CalipHATE. The cartooning renaissance was partly due to the difficulty for activists to use any sort of camera or video recording device without being monitored, prompting them to adopt other forms of visual storytelling and commentary. Many Syrian cartoonists have been forced to flee the country, but still manage to share their work there through social media. The best-known refugee cartoonist is Ali Ferzat, who now lives in Kuwait after he was severely beaten and had both hands broken by Bashar al-Assad’s secret police in 2011. He was one of the most prominent caricaturists in Syria long before that, even briefly publishing the satirical magazine al-Domari in 2000 before it was shut down by the government. Ferzat now disseminates his cartoons via his Facebook page.

CENSORSHIP ALIVE AND WELL This One Summer — an award-winning young adult graphic novel — is the No.1 most challenged book of 2016, according to the American Library Association, reported Ellie Diaz, oif.ala.org. “This coming-of-age tale follows 12-year-old Rose, a girl on the cusp of adolescence, and her family’s summer vacation in a small beach town,” said Diaz. “With her friend Windy by her side, the pair attempt to relive their childhood summers but are confronted with boys, parents fighting and the strains that accompany growing up.” The graphic novel, Diaz continued, by Mariko Tamaki with art by Jillian Tamaki, was challenged for “LGBT characters,” “drug use,” “profanity,” “mature themes” and being “sexually explicit.” This One Summer has also won many awards. “When it was listed as a Caldecott Honor Book in 2015 — an award that’s usually given to books aimed at younger audiences — librarians and educators rushed to purchase the book for their shelves. Some buyers were shocked to find that the graphic novel was intended for audiences age 12 and older, according to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. “Both Mariko and Jillian have been vocal about these censorship attempts, including on Twitter and on the radio,” said Diaz, going on to quote their statement that touches on the power of ideas and the reality of growing up; in italics—: This One Summer is a book about two girls’ summer at a cottage in Northern Ontario. When we wrote this book our goal was to create a story that explored the experience of summer and of adults, from a young person’s perspective. This book was not created for elementary readers, but for young readers. The publisher lists it for ages 12 to 18. There has been some controversy as to its inclusion on the Caldecott Honor list, so maybe it bears repeating that the ALA defines children as up to and including age 14. We agree the book is not for young children, nor was it intended for that audience. We worry about what it means to define certain content, such as LGBTQ content, as being of inappropriate for young readers, which implicitly defines readers who do relate to this content, who share these experiences, as not normal, when really they are part of the diversity of young people’s lives. A book doesn’t stop existing by taking it off the shelf. Nor do the ideas contained within. Pulling a book from a library shelf makes it inaccessible to kids who depend on the library for books. It’s an infringement on the freedom to read, to explore, to experience things outside of your world, to see yourself and your story in the pages of the books you read. The main character of This One Summer, Rose, is often afraid, confused, exposed to things outside of her comfort zone, things she doesn’t completely understand. We believe that is part of growing up. Life is often upsetting. But upsetting things in books are not actually happening in real life, but at a safe distance. You can read about an experience outside of your own, and gain the opportunity to better understand someone who it happens to in reality. You get to experience some of those emotions, without a personal price. Connecting to an experience outside of your own, or inside your own, is the core of social-emotional education, of developing empathy, which is very much needed in our current climate.

TRUMPEST AT THE BORDER Gisele Lagace, a Canadian comic book artist for Archie, Dynamite, IDW, and others in the U.S., plus her own webcomics, Menage A 3, was stopped at the border as she attempted to drive down to Chicago to attend C2E2 earlier last month, reported Rich Johnston at bleedingcool.com. The problem, according to immigration officers who denied her entry, is that she had unfinished commissioned sketches with her in the car. Working on them while in the U.S. would be considered working in this country, and apparently she’d need a visa, a special permit of some sort, to do that. Officers were not content with turning her away. Lagace reported on her adventure on Facebook (in italics)—: Welp, no C2E2 for me. ... Was asked if I was the only one doing this as I looked surprised to be refused entry. I said no, many artists from around the world attend these to promote themselves. I don't think they cared. My car was searched and is a mess. And to top it off, I was body searched and finger printed, too. (They do that when you get refused entry apparently.) It was an awful experience. Things then went worse when they searched me throughout and found 2 white pills in my wallet. There was no identification on them and I wasn't sure what they were. Once I calmed down after being touched all over, I remembered they were generic acetaminophen from the Dollar Store that I carry around in case Marc gets a headache as it sometimes happen. I forgot they were even in there. Anyway, I wasn't turned around for the 2 acetaminophen, as they found those after I was refused entry for the comics in my car and the unfinished sketches but they kept us longer there until they were convinced they weren't narcotics. I never took drugs in my life! And to think we drove close to 2 days to get there. For nothing. (No, I didn't get anything from that body search. Maybe Zii would think it's a good deal.) Anyway... Driving back home. Now that I've been refused entry in the U.S. for this, it's on file. Don't expect to see me at a U.S. con until I can figure out a way to get in and being absolutely certain this won't happen.

Fitnoot. Between 2008 and 2013, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund defended several customs cases in which border officials cracked down on manga. Some of the cases involved officials scrutinizing personal electronic devices. For advice about how to protect yourself against such extreme but entirely legal operations, visit cbldf.org and click on “Resources” to be transported to a section on “Customs.”

NEW CARTOON FORM AT THE NEW YORKER? With a new cartoon editor, Emma Allen, about to take over at The New Yorker, I was stunned to see cartoons in the strip form of comic book pages in the issue for April 3. Is this the new thing? Will Allen abandon the historic and iconic single-panel captioned cartoon in favor of comic strippery like the ones on display near here? Or is this violent deviation from the New Yorker norm just outgoing cartoon editor Bob Mankoff’s last iconoclastic splash?

Superbly rendered by R. Kikuo Johnson, who teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design, these inaugural four pages may foreshadow The New Yorker’s future. Who can say? The New Yorker has pioneered before in cartooning. And may again. I hope these fresh manifestations of the visual comedic arts merely join the other cartoons rather than displace the comic form that the magazine is largely responsible for honing into visual-verbal excellence. It would be a shame to destroy that historic legacy. A shame? Nay, a desecration of the haiku of cartooning. For another aspect to the advent of Emma Allen, see Women Cartoonists Assault down the scroll.

HUMOR TIMES FOREVER Humor Times, a monthly tabloid newspaper consisting entirely of editorial cartoons, is celebrating its 26th anniversary. I’ve been a faithful subscriber for about half the publication’s life, and I look forward like an addict to getting my monthly roundup of editoons. Here’s the message from editor James Israel—: We’re proud of our role in speaking truth to power in an entertaining way through the years. Right now, we’re experiencing a big of a resurgence, what with the Orange Menace in office. People seem to be in dire need of their political satire these days, and we’re doing our patriotic duty in providing it! Sure, we’re always leaned left as a publication. But we’ve always strived to balance it out with a lot of barbs aimed at Democrats as well as Republicans. However, this is an extraordinary time, with an extreme assault on American values we hold dear being perpetuated by a narcissistic, spiteful, minority-elected president, backed by a hard right Republican congress bent on destroying every positive accomplishment of the last 30 years. ... Combine this with the fact that the Democrats in Congress are utterly powerless and seem content to just hope Trump will flame out, and the political humor landscape is pretty lopsided. So, naturally, most of the editorial cartoonists are concentrating their efforts on the cartoonish president, and that’s what you’ll find in Humor Times. Subscription is $24.95/year, 12 issues; $2 less if you order online at humortimes.com. To order by mail, send your name and address and check payable to the Humor Times to: Humor Times, P.O. Box 162429, Sacramento, CA 95816. Phone orders: 916-758-8255

CLASSIC LOOK STILL LIVES AT ARCHIE With all the buzz over the last year or so about Archie characters’ new “modern” (i.e., somewhat more realistic) appearances (in Archie, Afterlife with Archie, Jughead, Betty and Veronica), it’s surprising that cartoonist Dan Parent is returning to a new monthly Archie series Your Pal Archie, which he’ll draw in the “classic” cartoony Archie style established by Dan DeCarlo, who followed in the manner of Archie originator Bob Montana. The new series, which will debut in print and online July 26, will be written and inked by Ty Templeton and edited by Victor Gorelick, who is now in his 60th year with Archie Comics, reported Dan Betancourt at the Washington Post’s Comic Riffs. The 52-year-old Parent has been drawing for the company for three decades, and in that time his version of Archie has become the artistic standard, but since the massive visual reboots, it is no longer seen in mainstream titles. Still, Betancourt says, “Parent considers himself fortunate to have been able to draw in the same style at one publisher for so long.” Said Parent: “When the reboot style was introduced, it was a big deal and garnered a lot of new fans. Fiona Staples [who introduced the new Archie] has a huge following, deservedly so. But I always had faith in the classic style, and knew it would coexist with the new style. And it has.” Even so, “Parent will be slightly altering his classic artistic approach to Archie, Betty, Veronica and the rest of the Riverdale gang. He turned to the new Archie-inspired CW hit television show ‘Riverdale’ for inspiration.” “The influence from [“Riverdale”] is more of a fashion makeover for me,” Parent said. “I’ve changed

the hairstyles a bit, and the clothes. And the faces are a little more detailed,

but the line work is still the simple classic lines I’ve always used,” Parent

said. “I hate over-rendering and too many lines, so I won’t go there. Less is

more.” Archie will also be hitting the weights a bit, said Betancourt, and have a slightly more buff frame, like his television counterpart, actor K.J. Apa. “Yes, that’s part of the fashion makeover,” Parent said. “But, along with the good looks, he has to be a little goofy too. It’s about striking a balance.” As for his artistic take on his Archie being considered the “classic” style, Parent has no complaints. “I never thought I’d do anything in my life for 30 years,” he said. “But I grew up loving these characters. And I still love them as much as I did when I was 10 years old.”

STATE OF THE ART OF COMICS SALES Comics sales figures are stagnant, but the mood among retailers remains upbeat, saith Heidi MacDonald at publishersweekly.com. That was the paradoxical takeaway from the Diamond Retailer Summit, a gathering of comics retailers held during the Chicago Comics Entertainment Expo (C2E2), which took place April 19-23 at McCormack Place in Chicago. MacDonald reports that initial numbers at C2E2 logged attendance at 80,000 fans, up from 72,000 in 2016, according to Mike Armstrong, event and sales director at show organizer ReedPOP. At the Diamond Retail Summit breakfast presentation for comics specialty retailers, results for the first quarter of 2017 were mixed, MacDonald said, “with comics periodicals up 0.7% in dollars but graphic novels down 10.7% from 2016. When toys are factored in, Diamond’s sales are down 3.5% for the year. Customer count— the number of new stores being opened— was flat.” The drop in graphic novel sales wasn’t explained, she said, “but may be at least partly due to [comparison with] the strong 2016. “Both Marvel and DC announced new programs. DC revealed Dark Matter, a line that will introduce new characters into the DC universe, executed by top level talent. Meanwhile, Marvel is looking to shore up its flagging sales with Legacy, a storyline that will bring back an emphasis on the brand's most iconic characters. “Dark Matter, announced at a high energy presentation by DC co-publishers Dan DiDio and Jim Lee, will see six periodicals roll out. The forthcoming titles include The Silencer by Dan Abnett and artist John Romita Jr., and Immortal Men, by James Tynion IV with art by Jim Lee. “At a press event Romita, whose father, John Romita Sr., was an iconic Marvel artist, pushed back against comments in the media about the importance of comics writers over artists. ‘People have the impression that writers are the gods of this process. They are not,’ Romita said. “Marvel’s rebranding is even more of an uphill climb,” MacDonald said. “After a multi-year stretch where their major characters were replaced by new ethnically and gender diverse versions— a black Miles Morales as Spider-Man and a female Thor, for instance— the Legacy initiative will return the regular white male versions of these heroes to their titles. It does so, however, after they team up with their replacements in a series of one shot periodicals called ‘Generations.’”

CHARTOON AT TIME For the last year or so, more-or-less, Time magazine has been publishing a feature it calls “Chartoon” by John Atkinson. Happily marrying “chart” and “cartoon,” Atkinson made the portmanteau word and its accompanying graphic serve both informative and entertaining purposes. I celebrated this development some months back as just another indication of the emerging societal dominance of comics and cartooning. We’re a visual species, I asserted, and cartooning is therefore at last assuming its rightful place in the hierarchy of human experience. Well, sure. But over the last few outings, Atkinson has produced less “chart” and more “toon.” In the accompanying visual aid on the left, I’ve paired a recent manifestation at the bottom with a couple charts at the top.

You can readily discern the difference. There is no “chart” in this “Chartoon.” There is only a cartoon about how far one of us antique geeks had to walk to school everyday. Atkinson’s effort—and Time’s use of it—still proclaims the emergence of cartooning taking an elevated place in an increasingly visual society but, now, without the excuse that “charting” some aspect of that society had provided. It’s just a naked cartoon, kimo sabe—and Hoorah for that. Next to that exhibit is Scott Bateman’s “Trump’s First 100 Days, Visualized,” which, as you can plainly see, is another chart. This one, however, is no chart at all but merely an uproarious send-up of charts and Trump. Read and rejoice.

ODDS & ADDENDA Lucky Luke, the "fastest gun in the West" —a wry and witty cartoon figure who outshoots his shadow, plays chess with his trusty horse, and wins against the bad guys every time— is turning 70. Blue jeans, yellow shirt, black vest, a red bandana and a white cowboy hat, that's been Lucky Luke's attire for the past 70 years. The Belgian comic series about the lanky cowboy who famously "shoots faster than his shadow" is one of the best-known in Europe and has been translated into many languages. It's also been adapted into animated films and TV series as well as live action movies.— Dagmar Breitenbach, dw.com ◆ Great fun on the horizon. DC is teaming some of its spandex cast with such Looney Tunes as Bugs Bunny (with the Legion of Superheroes), Elmer Fudd (with Batman), Yosemite Sam (with Jonah Hex), Road Runner (with Lobo), and the Tasmanian Devil (with Wonder Woman). These and others of this hilarious ilk will be in comic shops in June, it sez here. ◆ May 6 is Free Comic Book Day. First Saturday in May, every year lately. Some stores let you grab and walk off with whatever you can; others limit you to a specified number of titles—four or five, say. Worth a visit anyhow.

CORRECTION

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Magnets for your fridge—: If you obey all the rules, you miss all the fun.—Katharine Hepburn The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it. Why do people say “grow some balls”? Balls are weak and sensitive. If you wanna be tough, grow a vagina. Those things can take a pounding.—Betty White Education is what you get when you read the fine print. Experience is what you get if you don’t.—Pete Seeger

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

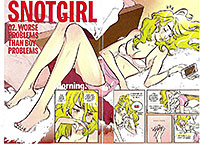

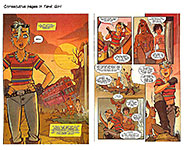

AS YOU KNOW, it’s the drawings in a comic book that attract—and, ultimately, hold—me. I was intrigued by the title Snotgirl and bought the first and second issues on that basis alone. I immediately loved the drawings by Leslie Hung, but Bryan Lee O”Malley’s story, alas, left me cold. Mostly, it revolves around the snotgirl’s assorted (not sordid) adolescent angsts, and that’s not enough to keep me coming back despite the unequivocal excellence of the drawing, the undulating line and clutter-free compositions (on display nearby). And Tank Girl falls into the same category. I’ve been buying the occasional Tank Girl issue for years, through a score of artists and writers. The wild drawing always sucks me in. But I lose interest the minute I start on the story. The current reincarnation written by Alan Martin and drawn by Bret Parson is a little less eccentric in the art department but still extremely attractive—crisp linework without feathering or other encumbrances. And this time, I steeled myself to finish reading the story in the first issue. A nicely complicated caper in which the Tank Girl’s favorite tank has been stolen and, eventually, sold to a museum, whose owner, Magnolia Jones, falls in love with the tank and dresses up like Tank Girl and then breaks the tank out of the museum and on to the road, where, inevitably, she meets the genuine Tank Girl. A contest of some sort looms, and the issue ends. The book satisfies all the usual criteria for a first issue—several completed episodes, clear delineation of the personalities of the characters, and a suspenseful ending. I should like this book. And I do. Just not enough to go for a second issue. It all moves in a manically amusing manner, but today, as I read it and then type this, the story is not enough. And Parson’s stunning artwork isn’t enough to bring me back all by itself.

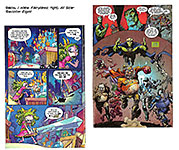

I picked up I Hate Fairyland while on the same kick: its artwork pulled me in. I bought No.1 and, just last month, No.9. Skottie Young’s draws with verve and panache—lively line and hilarious visual characterizations— but his story is too manic for my taste. It’s my loss, I realize; but I’m stuck with it. All

Star Section Eight is another of the same ilk: extravagantly rendered by John

McCrer—his distinctive bold feathering a joy to behold (which I do, with

joy, which ought to demonstrate that my affections for linework are not

restricted to the unfeathered, uncluttered sort). But Garth Ennis’s story is, deliberately, silly. Too silly for my taste. I read No.3, and I’ll

buy No.4, which promises “broads,” but I doubt I’ll go any further in this

title. All of which demonstrates that story counts for something. Even with a devotee like moi, whose passion is the visuals—linework and visual storytelling—the pictures aren’t quite enough by themselves. I need an engrossing story, too. “Section Eight,” by the way (although perhaps not at all incidentally), is a section of the pertinent military manual under which you may be discharged because you are psychologically unfit for regimented life. A person who is dubbed a “Section Eight” is, perforce, a nut case (or something very like one).

HERE’S ANOTHER

ONE THE ARTWORK of which grabbed me— Grass Kings by Matt Kindt and

drawn by Tyler Jenkins. Watercolor is an unforgiving medium, and it’s

not easy to control to begin with. The look of the pages appealed, so I bought

it. But the story went nowhere. A kid gets picked up by the village cop, and

they spend the issue driving around the town and talking. At the end, one of

the characters finds a girl named Rose, and another character, new to the

narrative—the sheriff of the neighboring town, I think—wonders “did you find

her?” Not much to go on here: the real problem, from a storytelling

perspective, is that watercolor art, beautiful though it is (and Jenkins’ is),

isn’t precise enough: we can’t tell, often, from page to page, who the

characters are. A baseball cap and a scraggly beard are almost enough to

identify a couple of them. But then the light changes.... Neil Gaimen, that cute boy with the bountiful mop of unruly curls, dressed all in funereal black, is getting to television. The tv adaptation of his novel American Gods is dubbed by Entertainment Weekly’s Marc Snetiker as “the most important show on television” because it addresses the question of what it means to be an American. I have the novel; haven’t read it. But I bought the first two issues of the comic book adaptation, drawn by P. Craig Russell mostly, with a second continuity by Scott Hampton. In the first issue, we meet the convict Shadow on the cusp of being released from prison and looking forward to joining his loving wife again. Just as he’s about to be turned loose, he learns that his wife has been killed in an auto accident. En route home in the second issue, Shadow is offered a job by his seatmate on the plane, who calls himself Mr. Wednesday. Eventually, Shadow takes the job. The first issue concludes with a four-page sequence by Hampton, who begins with a man and a woman fucking and concludes with some mysterious heaven-hovering beings. No explanation. Gaimen is a good storyteller. He can get us to turn pages. But stories in and of themselves are merely sequences—first this happens, then that happens, then something else happens. Page-turners. It takes stories with plots to reach another level. In a plotted story, something happens because something else has happened. Thus, plot gives sequences of events a larger meaning. And even though I’m not a regular fan of Gaimen, I’ve never seen anything of his that I’ve read in which he reaches that other level. For a page-turner, all you need is enough mysteriousness to make you want to see what’s next, to make you turn the pages. And Gaimen can do that. Lots of mysteriousness and faux spirituality. I’ll wait a while to see if he can give this page turner any larger meaning. But I don’t hold out much hope. I tuned in to the first tv installment of “American Gods.” Alas, I wasn’t impressed. Too much darkness and rumbling. I gave up after ten minutes. But I’ll try again. Maybe tonight.

WOMEN CARTOONISTS ASSAULT THE MALE BASTION By Hazel Cills at mtv.com There’s a new Cartoon Tuesday at The New Yorker: the traditionally white, male world of magazine cartooning is being challenged to recognize women’s work. Last month, it was announced that Bob Mankoff, the magazine’s cartoon editor for nearly 20 years, would be stepping down and that Emma Allen, an editor for the magazine’s Daily Shouts section, would be taking his place. “The magazine is a notoriously difficult place for a cartoonist to break into, and the fact that Mankoff’s replacement will be a woman isn’t just a small editorial change,” noted Cills, a staff writer at MTV News and a co-host of the podcast “Lady Problems.” She goes on to report on the implications at The New Yorker and elsewhere—: “Submitting to The New Yorker under Bob entailed pushing through a huge crowd of men to submit your work to a man,” tweeted Hallie Bateman, a cartoonist whose work has appeared on The New Yorker’s website, The Awl, Jezebel, and more. “Bob told me my cartoons weren't funny — but also that he was mandated to publish more women so I should come back,” she continued. The experience that set off her tweets, Bateman tells me over the phone, happened during the New Yorker process known as “Cartoon Tuesdays,” when several cartoonists bring a batch of 10 cartoons to submit to Mankoff in person. “It was just a ton of men, maybe one or two women in this huge crowd of white guys,” she says. “It’s really exciting, but it also doesn’t feel very good.” After Mankoff rejected her cartoons, Bateman went back to publishing online before trying again with the magazine, at which point he told her she can’t be a “dilettante.” “He seemed very offended that I thought I could just saunter into The New Yorker [again],” Bateman says. “There was the weird vibe of knowing that he needed and wanted more women. And basically, when he told me, ‘Only do this if it's what you want to do, not just because you want to get into The New Yorker.’ I looked at my cartoons and I didn't like them that much and was, like, I don't think this is what I want to do.” Mankoff wrote in an email that it is hard for all cartoonists to get into the magazine partly due to limited space, and that he has told many people “to get to be a New Yorker regular, be regular,” so as to pitch better work. "We’ve taken other steps to broaden our pool of artists, including reaching out to art and design schools,” he wrote, noting that there is still more work to do when it comes to publishing female cartoonists. "Call it a mandate if you want. That’s fine by us. It’s a good mandate — one that better reflects the world in which we live.” Emma Allen doesn’t start the job until May 1, and so she declined to comment, though she did say the following in an email: “[Hiring women] is certainly a subject that’s important to me. I’ve served as Daily Shouts editor since 2014 (and will continue doing so in addition to cartoon editing). In that role, I’ve worked to recruit scores of women humor writers — not hard, as there are so many talented women working in comedy — and just generally a more diverse mix of voices, a number of which have gone on to appear in the magazine as well.” That The New Yorker’s cartoon section needs to publish more women isn’t surprising considering how publications and newspapers are pushing to look beyond the white, male bylines that have dominated newsrooms and magazines for years now. [Summarizing the next of Cills’ paragraphs, which I’ve omitted here: magazines are actively seeking to be more diverse, and numerous institutions like the Columbia Journalism Review, Nieman Journalism Lab, and VIDA are keeping track of diversity and gender disparities when it comes to writing in mainstream publications, but there are few counting how many cartoons and illustrations by women make their way into print.—RCH]

FEMALE ILLUSTRATORS MAKE LESS MONEY than their male counterparts on average and still have a long way to go when it comes to winning awards. ... So while publications are seeking to diversify the bylines of writers and artists, when it comes to the artwork and cartoons published alongside them, the conversation is just getting started. After artist Julia Rothman discovered that 55 issues of a prominent, unnamed magazine included only four covers illustrated by women in a year, she and artist Wendy MacNaughton decided to create Women Who Draw, a website that indexes female-identified illustrators and cartoonists. ... Women Who Draw is similar to artist Mari Naomi’s Cartoonists of Color Database, which has divisions for cartoonists of color, female cartoonists of color, and LGBTQ cartoonists of color. Naomi, a Japanese-American cartoonist and author whose work has appeared in BuzzFeed, xoJane, and Bitch, originally started the database as a personal list she kept for herself and kept adding to. “Once I had, like, 100 or 150 I thought, Man, someone should really put a list together and put it on the internet,” Naomi tells me. “Then my stomach fell and I realized that if I didn't do it, probably nobody would.” The truth is that female cartoonists have always existed, so much so that panels about “women in comics” at festivals are seen as passé. The National Woman’s Party had several cartoonists making work for the suffrage movement, like Nina Allender and Ida Sedgwick Proper. ... In the ’70s, Shary Flenniken was a member of the San Francisco cartoonist group the Air Pirates, and would go on to edit the National Lampoon. She recalls getting work and making contacts by hanging out in bars and palling around with guys. “There are a lot of friendly men who are kind of afraid of women cartoonists,” she says. “I think they sense that we are able to draw that picture of them saying something stupid and really take them down a notch.” Flenniken ended up quitting the Lampoon because she couldn’t deal with “office politics.” She describes championing the work of a rising illustrator named Mimi Pond, whose comics were cut out of an issue at the last minute. “I think that was kind of the last straw for me,” she says. “I always stick up for women and I had to defend her because it made me really mad that they cut her out. I felt like it was a big issue!” ...

THAT ONE-NOTE VIEWPOINT can sometimes lead to disastrous and sexist results. In 2015, for example, Edel Rodriguez’s controversial Newsweek cover illustrated a story on sexism in tech with a simplistic drawing of a woman’s skirt being lifted by a computer arrow. Rodriguez and the story's author defended the cover because they felt it accurately captured Silicon Valley’s sexist culture, but it was derided by many female illustrators and women in tech, and called “despicable” on the “Today” show. Rodriguez’s views on the cover have not changed, and as for whether women’s stories should be illustrated by women specifically, he believes it’s a “very close-minded concept.” “The story was about sexual harassment in Silicon Valley and that is what I illustrated,” Rodriguez wrote in an email, citing illustrations he has done on subjects that he has no experience with, like Africa or living with disabilities. “I think it’s a dangerous road to take for illustrators to state that we are best qualified to illustrate only stories that deal with our own experiences.” The “sameness” of cartooning doesn’t just occur on a hiring and commissioning level, but in the illustrations themselves. In 2015 a study conducted by the journal Proceedings of the Natural Institute of Science found that over 70 percent of characters depicted in New Yorker cartoons are white men, with women disproportionately depicted as moms, wives, and assistants. And many female artists find themselves playing down aspects of their work that are too feminine, too queer, or too diverse to meet a traditional look of mainstream comics and illustration. “If there are white people in the comic, that’s the go-to,” Naomi says. “But as a person of color, I feel like we have kind of been too discouraged when it comes to including diversity. Even just a one-panel joke, if it’s a gag joke that’s happening to anyone but a white male. If it’s a woman, or if they’re black, there always needs to be a ‘reason’ for that. The question i: Why is that person that way?” ... [It’s the classic dilemma faced by every cartoonist, all of whom deal in stereotypes. The stereotype of a doctor is a guy in a white coat with stethoscope around his neck. If you draw a woman wearing a white coat with a stethoscope around her neck, readers perceive her as the nurse. Naomi’s talking about something slightly different. If you draw a panel cartoon with three people in it and one of them is a person of color, the average reader will be looking at the caption to find out why you’ve put a person of color in the cartoon. Are you saying something about race? To get around this, you have to put four people in the cartoon and make two of them people of color. And even then, you might not succeed.—RCH] Sara Lautman, a queer cartoonist whose work has been published in The Pitchfork Review, The New Yorker, Playboy, and more, describes how she can see firsthand what gets accepted at a place like The New Yorker versus a place like The Hairpin. “I think I went in with 90 percent of the stuff that was kind of queer or weird or just explicitly feminist, but I never sold anything that I'd consider that category,” she says. “[Mankoff] has to look at so much stuff, just like all editors, and you have this built-in filter that catches the stuff you want and lets go of the stuff that you don't want or that doesn't concern you.” ... The problem is that while work by female artists is frequent on women’s blogs and online spaces, there are problems that come with work being relegated to the web, especially when it is still considered less prestigious or secondary to print. “You get paid a lot more when your stuff is in print versus online,” Rothman says. “You could have a lot of women being hired online but not for the printed version, and then they make half as much as the men.” ... “Cartoons have to be universal,” Bateman tells me toward the end of our interview. She tells me about the work of Sempé, a French cartoonist she loves whose work features a lot of tiny men. But some of it, she says, is alienating because “the man’s perspective is in the spotlight,” such as in a scene of a bustling café in which the only woman is in the corner with a serving tray. “That feels shitty to read. It feels shitty to be closed out of this beautiful world that’s trying to be represented,” she says. “Whatever the artist is trying to communicate, it isn't getting through to everyone because it isn't getting through to me. It's obscured by the fact that he's showing one type of face. I think diversity of faces, of bodies, of gender is so important to welcome everyone in. Our goal is communication, and we want to communicate to everyone.”

QUOTES & MOTS One-liners for your amusement—: If we quit voting, will they all go away? To all you virgins: thanks for nothing. Practice safe sex: go screw yourself. A procrastinator’s work is never done.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy By reason of

his instinctive showmanship prodded by a deeply felt need for public adulation

of the most extreme sort, Donalt Rump continues to be the headline personality

of the month—although his grip on visibility was briefly threatened by Bill

O’Reilly’s sexual adventuring and subsequent dismissal at Fox, something I

thought I’d never live to see. I’m thankful, however, to be spared for the rest

of my life seeing O’Reilly’s fatuous visage, smug smile, and pompous demeanor.

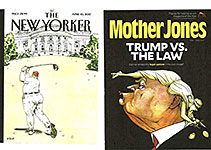

In celebration, I produced the caricature in the accompanying visual aid. And while I was at it, I took another jab at the Trumpet. It will, I trust, remind you of another Prez of bygone times whose attempt at proclaiming his innocence was similarly contradicted at every turn. The Trumpet’s image kept turning up on the covers of magazines, too, a sure sing of his growing popularity as a target.