|

||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 357 (September 19, 2016). If you want to catch a rabbit, you hide behind a tree in the wild and make noises like a carrot. Or read this installment of Rancid Raves, where we sample the crop of the month’seditorial cartoons during the Season of Trumpery, review graphic novels The White Donkey (U.S. marines in Afghanistan) and Templar (during the Crusades), plus the new collection of Charles Rodrigues’ cartoons, Gag on This, and Alan Moore’s gigantic Joycean prose novel, Jerusalem, and we look at these comic book first issues: Kill or Be Killed, Lucas Stand, Lady Killer 2, Kingsway West, Control, The Violent, The Fix, Black Monday Murders, and Lake of Fire. And more, much more (including telling excerpts from a Bill Watterson speech in 1991 and porn covers on newsstand comics—well, bookstore stands). This posting, you’ll see, is huge. We just can’t shut up. But that’s what it’s all about, eh? Talking about comics. That’s what we do here. But every time we get ready to post, the Trumpet blasts a new outrage and editoonists leap to their drawingboards, and we have even more to say. So we admit: there’s more here than can be read at a single sitting. We recommend using the contents listed below as a shopping list: scan the items listed and pick those that interest you; then scroll rapidly down to the ones you’ve picked, skipping over boring stuff. Politics and editooning spirals nearly out-of-control this time because of the political conventions and the Prez Election shenanigans; but if you’re not into politics, skip all that and go on to what you like. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Comics Sales Good New Comics Magazine Facebook Censor Flubs Badly Iranian Cartoonist Wins Courage Award Cartooning An Endangered Species? Moore’s Joycean Novel Just Published Hef’s Playboy Disappoints Again Snarking The New Yorker Odds & Addenda—: March Up for Award Salinger Studio for Student Cartoonists Prez “Cancelled” To Avoid Political Fallout? Who Started the Birther Scam?

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of 1st Issues of—: Kill or Be Killed Lucas Stand Lady Killer 2 Kingsway West Control The Violent The Fix Black Monday Murders

Excerpts from Bill Watterson Speech in 1990

THE FROTH ESTATE News Media Give Trump More Time

EDITOONERY Sampling the Last Month’s Crop of Editorial Cartoons (A Lot of Trumpery)

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Sandy Eggo Artists Alley in 1991: I Wuz There RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pretty Girl Art Edges Into Porn

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL News and Taboos in the Funnies

BOOK MARQUEE Short Review of—: Gag On This: The Scrofulous Cartoons of Charles Rodrigues

A-GAGGING WE SHALL GO The New Yorker’s Post-9/11 Cartoon

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Reviews of Graphic Novels—: The White Donkey: Terminal Lance Templar Lake of Fire (1st issue, comic book, related to Templar)

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY A Sterling Big of Reasoning by Leonard Pitts, Jr.

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

COMICS SALES LOOK GOOD SO FAR THIS YEAR Heidi MacDonald at publishersweekly.com reports that after a year of slipping sales and smaller lines, the comics industry was in a more upbeat mood at the 2016 Diamond Retailer Summit, held August 31-September2 in Baltimore by Diamond Comic Distributors, the main distributor for periodical comics and traditional comics publishers. ... While sales have yet to fully recover from a shaky start this year— overall sales are down 2.2%— graphic novels are up 2.4%. Additionally, Diamond’s customer count is up 3.6%. Periodical comics are down 2.6%, and merchandise down 1.6%. However, at a breakfast presentation, Diamond reps announced that sales had picked up over the summer, and by year's end they expect sales to stabilize. The growth in graphic novels was remarked on by nearly every publisher. Mainstream authors Chuck Palahniuk and Margaret Atwood have had success at Dark Horse, said editor in chief Dave Marshall, at a state-of-the-industry panel. “More and more of our readers are preferring the collected [book] format.” ... Much of this summer’s surge in sales is due to DC’s Rebirth event, a moderate revamp of its superhero comics line, which launched in April and has shipped over 12 million returnable units since then. The sales velocity of Rebirth has been even bigger than 2011’s New 52 (an earlier DC superhero revamp), with Rebirth showing a 76% rise in sales compared to New 52’s 47% rise. DC hopes to continue the upswing with a Justice League vs Suicide Squad event—DC’s iconic superhero team battles DC’s bad-guys turned good-guys team—early in 2017, announced by co-publishers Dan DiDio and Jim Lee. At Marvel, retail channels outside the direct market (local comic book stores) have had an impact, including Scholastic Book Fairs, where lighthearted Marvel characters such as Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur and The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl are sold. Marvel senior v-p of marketing and sales David Gabriel said Marvel is having its best year since he started at the company 14 years ago. The new Black Panther series by Ta-Nehisi Coates has also expanded the diversity of Marvel’s line, as well. Other publishers saw a similarly rosy horizon.

A NEW COMICS MAGAZINE Image has a new

scheme afoot. For three months, Image has produced a magazine, Image+, which

offers interviews with funnybook writers and artists and generous samplings of

the pages they have written and drawn. While it is an obvious promotional

effort (only Image comics creators are interviewed and their work sampled), it

is also engaging in its own right and nicely informative as even promotional

publications can be. Initially distributed free to subscribers It’s not clear whether, as a Previews subscriber, I’ll continue to get a copy free with my catalog, but I have hope. One of the magazine’s treats is the clever inside front cover comic strip, Comic Lovers, by Brandon Graham, who gently spoofs comics artistry and criticism as he exemplifies both; a sample appears at the corner of your eye.

FACEBOOK CENSOR FLUBS BADLY From Maren Williams’ report at CBLDF—: In the face of international condemnation and ridicule, Facebook reversed course recently after initially blocking one of the most famous war photographs of all time because it includes a nude minor. Taken by photographer Nick Ut, the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo titled “The Terror of War” shows nine-year-old Kim Phuc, along with other South Vietnamese children and soldiers, fleeing a friendly-fire napalm attack in 1972. Phuc sustained severe burns across her back, and the searing image helped to turn U.S. sentiment against the war, contributing to the ceasefire six months later. The 44-year-old photo came to Facebook’s attention last week when Norwegian writer Tom Egeland included it in a post about “seven photographs that changed the history of warfare.” Egeland’s account was subsequently suspended, prompting the newspaper Aftenposten to cover the story and use the same photo as a preview image on Facebook. The newspaper in turn received a moderation notice asking that it “either remove or pixelize” the photo, but the post was deleted by Facebook before Aftenposten staff could take action. Later, Facebook, face red, restored the iconic photo and its various encumbrances.

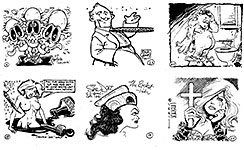

IRANIAN CARTOONIST WINS COURAGE AWARD News Release from CRNI Joel Pett, President of the Board of Directors of Cartoonists Rights Network International, announced the recipient of the Award for Courage in Editorial Cartooning for 2016. Every year, CRNI searches the world of political cartooning for those who have demonstrated exceptional courage and resilience in the face of life-threatening risk and danger. Political cartoonists are often the first journalists to be attacked for their irreverent and satirical commentary against tyrants and terrorists alike. Because their cartoons are so immediately comprehensible, they often have more power and influence over public opinion than other media, particularly in countries where literacy is not widespread. In such countries, cartoonists’ pictorial reportage tells the tale. And if the country is run by a dictatorship, that entity doesn’t like the cartoons or the cartoonist. This year’s recipient, whose pen name is Eaten Fish, is an Iranian national, currently interned in the Manus Island detention camp in Papua New Guinea. This notorious detention center is funded and overseen by the government of Australia. Various human rights groups have spoken out against the Manus Island camp, with the UN recognizing that indefinite detention and the practices employed in the camp constitute “cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment” and break the UN Convention Against Torture to which Australia is a signatory. Eaten Fish has been able to keep up a stream of cartoons documenting the unspeakable abuses and excesses of the guards and administrators of the camp. For this he has been the subject of beatings, deprivation of food, and even worse degrading treatment by the guards. Australia has made publication of negative information about the camp punishable by two years in prison. The importance of the work of human rights defenders, artists, cartoonists and writers, such as Eaten Fish, within the prison camp cannot be overstated. Nor can the fact that they are at further risk of violence each time they create, speak, draw or write. Eaten Fish is one of those who’s work as a cartoonist brings to light the horrors that are happening around him. CRNI believes that his body of work will be recognized as some of the most important in documenting and communicating the human rights abuses and excruciating agony of daily life in this notorious and illegal prison camp. His work pushes through the veil of secrecy and silence and layers of fences in a way that only a talented artist speaking from the inside can. We hope that this award will help shine a brighter light on the excesses of this camp. His work is addressed to the critical eyes of the world while exposing the xenophobic and racist policies of the Australian government in their dealings with immigrant refugees. The award will be presented in absentia and accepted by Janet Galbriath, an Australian poet and human rights worker, and founder of Writing Through Fences. Galbraith has made it her business to uncover the excesses of the Australian government’s policies in the Manus Island camp, The award will be presented at the final dinner of the annual convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists in Durham, North Carolina on September 24, 2016.

CARTOONING AN ENDANGERED SPECIES? Editorial cartooning has been in trouble for years. In May 2008, 101 editoonists worked full-time on the staffs of American daily newspapers. That number is now 50. The erosion of this profession has been attributed to the plight of the newspaper itself. Newspapers aren’t making as much money for their stockholders as they once did—and the possibility of expanding paid circulation in the age of the free Internet is remote, foreclosing the option of increasing revenue. The remaining balance sheet choice is to reduce expenses, which means, mostly, cutting staff, and editoonists are the supposed luxury and therefore go first. But some attribute the slow death of editooning to other causes. Timidity. Ted Rall calls it “corporate slacktivism,” an aversion to rocking the boat with satire. Editoonist Clay Jones, quoted (like Rall) by Jaime Lopez at news.co.cr, agrees: “I do feel that newspapers are afraid. To be honest, most editors don’t know a good cartoon when they see it. They love obituary cartoons. They love the most obvious. The laziest cartoonists draw the same old cliches of sinking ships, candidates as Pinocchios, people going over the edge and so on. And those cartoons get a lot of reprints. Check out USA Today every Friday. Most newspapers reprint cartoons and don’t have a staff cartoonist.” Freelance cartoonist Dean Haspiel, not an editoonist but still looking to sell cartoons for publication, gave the keynote at the Harvey Awards ceremony at the Baltimore Comicon. Speaking about the once vibrant New York City scene for freelancers, he remembered basement “night clubs” and second floor venues where people went for entertainment. No more. “Who goes anywhere anymore when everyone is glued to their smart phone and tablet?” And for the freelance cartoonist looking for publication outlets, “it’s hard to compete for an audience that can’t extricate themselves from the Internet for a couple hours to experience something live and direct with carbon dioxide. Our surveillance society has created attention-deficit-disorder zombies. The ‘scene’ got taken hostage by the screen.”

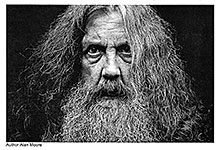

COMICS GURU ALAN MOORE PRODUCES JOYCEAN NOVEL Nobirdy Avair Soar Anywing to Eagle It With the publication last month of his extravagantly long and complex prose novel, Jerusalem, Alan Moore announced that he is planning to retire from the other medium in which he has worked for so long, the one that brought him fame—comic books. But not, it seems, right away. The creator of such medium-altering works as Watchmen, V for Vendetta, From Hell, The Killiong Joke and The League of Extraordinary Gentleman said, at a press conference about Jerusalem, “I have about 250 pages of comics left in me,” and he may produce them in Cinema Purgatorio and Providence from Avatar, and the final book of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. That, however, would fall short of his life-long goal, “to do a large work on a large scale.” He plans to keep working, but to focus on films and literary novels, still aiming at that large opus. Jerusalem, a nearly 1,300-page work of words with no pictures, presumably is a milestone on his road to that goal. It took Moore ten years to complete. Andrew Ervin, an author and critic writing in the Washington Post, says Jerusalem “is epic in scope and phantasmagoric to its briny core. It takes place over 1,000 years in the English town of Northampton [Moore’s hometown], also known here as the Boroughs. It’s a hardscrabble realm teeming with painters and prostitutes, would-be poets and biblical demons. The angels play snooker with the eternal souls of the residents on the line.” Moore would agree; he says the book celebrates the city’s “long tradition as a haven for religious firebrands, insurrectionists and the plain old mad.” David Franich at ew.com waxes large in his approval of the book: “Here it is, the big-swingiest of literary big swings: A Very Long Book About Very Nearly Everything. In Alan Moore’s Jerusalem, witness the span of a human life, the lifespan of humanity, and the four-dimensional space-time architecture of life after life. And, in Jerusalem, witness all that cosmic scope, filtered through the dust-mite microcosm of a single neighborhood in a single city.” “Jerusalem,” Ervin continues, “ revels in the idea of eternalism, the theory that past, present and future exist all at once. Everything that has ever happened in Northampton is still happening. Everything that eventually will happen there is already happening now. Amid that chronological and ontological maelstrom, Moore’s characters must reckon with the occasional slippage between their town and a shadowy parallel realm known as Mansoul. From Mansoul, the deceased can watch all of the goings-on in the town.” The book is obviously, self-consciously, Joycean (perhaps as homage and, in some places, as parody). “Yes, yes, very much,” burbles Franich. “Many of Jerusalem’s chapters follow the life-in-a-day structure of [James Joyce’s famous] Ulysses, with characters thoughtfully perambulating around a few square blocks in Northampton. Then you get to the part when Joyce’s daughter Lucia has a sexual encounter with pop idol Dusty Springfield— said encounter witnessed by actor Patrick McGoohan and the balloon-monster from McGoohan’s TV show “The Prisoner.” ... Did I mention that whole chapter is written in the style of Joyce’s infamously post-coherent masterpiece Finnegans goddamn Wake??? Sample line, pulled from the middle of a random sentence: “... Lucia askplains dashy’s expictured beckett d’main how’s o’ the massylum in spacetime for tea an’ dusks her newd frond four dimections to delaytr roaches of the ninespleen severties… Hence the subtitle of this article, ripped from Finnegans Wake. “The novel doesn’t have a through-line plot arc any more than do Hieronymus Bosch’s hell-scapes,” said Ervin. “But we learn a great deal about the Vernal and Warren families,” the chief characters (other than the town itself) of the book. Another Joycean kinship. “Moore’s own prose is always lively and rarely orthodox,” said Ervin. “He can evoke mirth and dread in equal measure. His similes want to leap from their pages. A lackluster intimate encounter ends ‘like an old tea towel that had been wrung out time after time until the pattern on it disappeared.’ “The prose sparkles at every turn, but that’s not to say it’s without flaws. Some entire chapters, particularly in the middle Mansoul section, struck me as wholly soporific. Moore also demonstrates an affinity for overwriting. I was hard-pressed to find many nouns that did not arrive man-splained with an unnecessary adjective. Here’s a typical sentence: ‘The big square bathroom with its plaster-rounded corners is a blunted cube of grey steam rising from the eight-foot chasm of the filling tub, an ostentatious lifeboat made from the tide-lined fibreglass.’ “That maximalist, kitchen-sink approach accounts for many of its pleasures,” Ervin conclude: “There are unexpected twists and frequent hairpin changes in mood. What makes it truly shine, however, is its insistence that our workaday world might not be quite as mundane as we think. Lurking in the corners of the ceiling, we might just find a portal to a different realm. The imagination Moore displays here and the countless joys and surprises he evokes make Jerusalem a massive literary achievement for our time — and maybe for all times simultaneously.” Well, that may be a bit much. A bit too Joycean perhaps.

MOORE HIMSELF,

in an interview with the New York Times, sees the book as filling “a

need for an alternative way of looking at life and death. I have a lot of very

dear rationalist, atheist friends who accept that having a higher belief system

is good for you — you probably live longer if you have one. You’re probably

happier. So I wanted to come up with a secular theory of the afterlife. As far

as I can see, and as far as Einstein could see, what I describe in the book

looks like a fairly safe option in terms of its actual possibility.” The interview ranged across a wide spectrum of subjects, including the present state of the world and democracies in it. Given Moore’s frequent forays into fictional dystopias, his interviewer asked if he felt like we’re further down the path to dystopia now than when he wrote, f’instance, V for Vendetta in the 1980s. “I wouldn’t say that,” Moore responded. “The world inexorably gets more and more complex. Against that complexity you’re going to get things like fascism and extreme religious fundamentalism. You’re going to get that. In an increasingly complex world all of those people feel that they’re losing ground. Extreme nationalism: this is a reaction to the fact that the very concept of a nation is being eroded.” This development accounts for Brexit in England and Trumpism in the U.S. “Wildly misguided protests,” Moore said. “This is what democracy looks like now.” At 62, Moore is on the very short list of people responsible for why mainstream audiences—and corporations—treat superheroes as very serious stuff, mused his interviewer. So what does he think of comics these days? Comics these days—that is superhero comics—aren’t aimed at 12-year-old children anymore. “The average comics reader these days is probably in their 30s, their 40s, their 50s,” Moore said. And that’s “slightly unhealthy.” He continued: “People have been saying since the mid-'80s that ‘comics have grown up.’ I don’t think that’s factually true. I think what happened was that there have been a couple of comics that seemed to be reaching for a more mature readership, and that has coincided with the emotional age of the mass audience coming the other way.” And he agreed with his interrogator’s saying: “So the success of superheroes movies, for example, has less to do with the characters proving that they can be narratively interesting or embodying popular ideas about the culture and more to do with audiences getting increasingly immature?” More went on in a slightly different direction: “The fact that I spent so long in comics was a surprise. Economics was a big part of that, and also things just have a momentum of their own. But my true background is in experimental art, and I was interested in almost everything. I wanted to do some songwriting and I wanted to do some performance, and I have done all those things. I feel genuinely excited about where I’m at now. That’s not how I feel about comics.” But Moore left the door open to some future comics work on a limited basis after finishing the 250 pages he has left:. “After that, although I may do the odd little comics piece at some point in the future, I am pretty much done with comics,” he said.

THE LATEST DISAPPOINTMENT FROM HEF The latest

non-nude Playboy is out, and it again has a full-page unabashed cartoon

by Nick Gurewitch, his second As for the nefarious “no nudes” policy—not so. The wimmin are naked, but we see no full frontal nudity. A lot of coyly draped nudity, though—with lots of naked butts, Playboy’s new obsession. But no nipples. No pudenda. No, no, no no.

SNARKING THE NEW YORKER The September

12 issue of The New Yorker has another of those covers drawn with a

compass by Ivan Brunetti. I

did a cover employing something of the same contrivance back in 1957 for a

homecoming football game program when I was in college. I’m not saying my cover is superior to Brunetti’s. He has more people in his scene than I have in mine. But there was a kindred attempt to give all those people something individual to do. This issue of The New Yorker also advertises The New Yorker Festival, 3 days of seminars and speeches around the City by notable personages on current affairs and comedy, October 7-9, Friday through Sunday. The event is not free, but the magazine, fatuously impressed, no doubt, by its own presumed cultural and social grandeur, does not deign to tell us in the 4 pages of advertising what the tickets cost. Smug self-importance galore. Real New Yorker readers are not to be bothered by such mundane matters. To discover this vital $crap of information, you must hie thee to the Web, where, at newyorker.com/festival, you learn what attendance will cost you—$45 on Friday, $50 on Saturday, and $55 on Sunday. But you have to have a computer with Internet access to learn this. And as everyone knows—everyone at The New Yorker—only people well-to-do enough to own a computer are readers of The New Yorker.

ODDS & ADDENDA Representative John Lewis is among the 10 authors on the “longlist” for the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, the National Book Foundation announced. Lewis’s recognized work is his civil-rights memoir March: Book Three, the final installment in his graphic-novel trilogy that has his 1965 Selma March as its dramatic centerpiece. The powerful March trilogy — co-authored by Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell — continues to attract a raft of honors, from the RFK Book Award to the Eisner Award in July. ■ The former New Hampshire home of the famously reclusive author J.D. Salinger was bought recently by Harry Bliss, a New Yorker cartoonist and former board member at the Centre for Cartoon Studies. The house is adjoined by a studio apartment (reached through a tunnel from the main property that enabled Salinger to go back and forth without being seen) which Bliss thought might be a good space to have young artists come and use whilst studying at the Centre, presumably. “The idea of nurturing a graphic novelist – I’m so into it,” Bliss said, “—this idea that you could go somewhere and be away from everything and have that intimacy with your work.” ■ The satirical comic book Prez, about the first woman teenage president of the U.S. was supposed to return in October with six more issues that would complete the 12-issue series. But those issues have been cancelled, ICv2 reports. Instead, a 12-page Prez Election Special will arrive in some form in November. No official reason was offered for the change, and perhaps poor sales had some influence, but Steve Bennett (Confessions of a Comic Book Guy) speculates that “given the nearly hysterical political mood of the country as we move ever closer to this year’s presidential election, you can’t discount the possibility that Time Warner just didn’t want to seem to take any sort of political stance (especially with so many people busy online comparing one of the current candidates to former President Lex Luthor).” No official announcement about where, exactly, the Election Special will be published. Apparently at DC Comics, George S. Kaufman’s famous saying “Satire closes on Saturday night” is as accurate ever.

WHO STARTED THE BIRTHER SCAM? I know: this is supposed to be about news in comics and cartooning. But the Trumpet is such a big success as a cartoon figure that I thought this disquisition belonged here. Donat Rump held a news conference on Friday, September 16, at which he conceded that Prez Obama had been born in the U.S. after all. Then, as is his custom, he looked around for someone else to blame for his bad judgement in starting the whole birther business, saying: “Hillary Clinton and her campaign of 2008 started the birther controversy. I finished it. I finished it, you know what I mean?” It was a patently false claim for which he had absolutely no evidence. But it’s not the first time the Trumpet has accused Hillary of being first to raise questions about Obama’s birthplace, an assertion that has been repeatedly disproved by fact-checkers who have found no evidence that Clinton or her campaign questioned Obama’s birth certificate or his citizenship. Despite this “fact,” Trumpkins stoutly maintain (one did to me on Friday night over a beer) that fact-checkers proved just the reverse, that Clinton started it. So I looked it up. Here’s the story from ABC News: The Trumpet’s campaign has circulated a link to a memo written by Clinton’s 2008 chief strategist, Mark Penn, suggesting they promote then Senator Obama’s “lack of American roots,” as well as the transcript of an interview Clinton’s 2008 campaign manager Patty Solis Doyle, where she tells Wolf Blitzer a staffer forwarded an email promoting the birther conspiracy in 2007, but that staffer was immediately fired. Penn did write a memo in 2007 saying that Obama’s foreign experience growing up could present a weakness for him, and Clinton should emphasize her middle-class Midwestern upbringing. "His roots to American values and culture are at best limited," the memo says. "I cannot imagine America electing a president during a time of war who is not at his center fundamentally American in his thinking and values." But it does not say that Obama was foreign-born. No evidence has been uncovered to link the idea of birtherism to the Clinton campaign. In 2015, Clinton told Don Lemon the claims that she and her campaign started the Obama birther attacks were "ludicrous and untrue." But there have been several reports linking the first major instance of floating the theory to Clinton's supporters. In 2008, the fact-checking website Factcheck.org said the idea of “birtherism” could originally be traced to Clinton’s diehard supporters, as it became clear she was going to lose the nomination. This was supported by reporting from other outlets, including the Telegraph, and Politico. But Clinton’s supporters aren’t the same thing as Clinton’s campaign. “There is no record that Clinton herself or anyone within her campaign ever advanced the charge that Obama was not born in the United States,” Politifact, another fact checking website, wrote last September following Trump’s tweet that Clinton started the birther movement and was "all in" on the movement. So there.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO There will be prayer in public schools as long as there are math tests.—Anonymous

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

ED BRUBAKER and Sean Phillips are back with a new crime/horror series, Kill or Be Killed. In the opening sequence, Dylan, the 28-year-old grad student “hero” of the series, is wearing a black hoodie and a red face mask and he kills five people. He shoots four with a shotgun, then beats the fifth to death with the weapon. These are “bad people” he tells us in the running first person narrative captions: they deserve to die. The remainder of the book is devoted to his telling us how “it all started.” We see him being bullied while with his girlfriend, but, no, he says, it really started when he tried to kill himself by jumping off a building. And that happened because of his relationship with his “best friend,” Kira, who was dating his roommate, Mason. She started kissing Dylan whenever Mason was out of the room, and Dylan realized he loved her. And then he heard her in the next bedroom with Mason saying she felt sorry for him. So he jumped off the building. Fortunately, he got caught in laundry lines between buildings: they broke his fall, and he landed in a snow drift, not badly damaged. But he was now seriously disoriented. He resolves to tell Kira he loves her “in the morning,” but during the night, he’s visited by a “demon”—a fuzzy-looking, horned black blob with glowing eyes and gritted teeth—who tells Dylan that he owes him “a life for a life” as payment for his “second chance” at life. He tells Dylan that he must kill “bad” people, one a month. Dylan thinks the demon is some sort of bad dream or hallucination, so he rejects the demon’s command, and the demon breaks his arm. Kira takes Dylan to the hospital to get his arm attended to, but instead of telling her then of his secret love, he remains silent. And that’s the end of the book’s completed episode. We learn that Dylan is a quiet guy with good impulses but is otherwise disturbed. Dylan gets the flu or some other fever-inducing ailment and is haunted by visions of his delusional demon. After a couple days, he decides to go to the emergency room to get treated. On the way, he’s assaulted by two ruffians who beat him and leave him lying in the snow. That’s when Dylan decides he’ll d the Demon’s bidding: he’ll “find someone who deserves to die and kill them. How hard could that be?” So now we know how Dylan became a hooded masked killer. Next, we’ll learn how he finds bad people to kill. At Image+, in previewing the title in No.2, the editors gave away the story when they said: “Kill or Be Killed is the story of ayoung man who is forced to kill bad people, and how he struggles to keep his secret as it slowly ruins his life and the lives of his friends and loved ones.” In the same issue, Brubaker says the series is “our take on the vigilante killer genre, which I hope means it’s not what people usually expect when they think of that. ... The basic idea is like a stone thrown into a pond—what happens to this guy when he starts putting on a mask and killing people? And from that, there are just so many ripples to explore and story alleys to go down.” He says he “missed the open-ended, always upping the stakes kind of storytelling. ... A kind of ‘Oh shit, what happens next?’ type of story, and I missed that vibe. But I wanted to find a way to do it that was different, that was not a story about a hero, but kind of twisted examination of the entire idea of what it means to be a vigilante instead.” Phillips’ rendering of the story is, as usual, superb. He is always good, but I think he’s getting even better. And Brubaker lets Phillips’ pictures tell a fair share of the story. In the confrontation sequence with the demon, Phllips alternates full-figure shots for orientation with close-ups of Dylan that emphasize his emotional reaction. Much of the story is heavily shadowed: it takes place at night. Phillips does some great night scenes in the streets of New York as the snow is falling—spectacular. But the pictures are always subordinate to the story—providing atmosphere, of course, but never failing to supply necessary narrative detail.

In the Image+ interview, Phillips said: “I never look forward to drawing any of it. Every new script just seems to be a lot of impossible things to draw. Once I get started though, it seems just difficult. I never know anything further ahead than the script I’ve got, so I’ve got nothing to look forward to drawing. I’m as excited with Kill or Be Killed as I am with everythning else I do with Ed and Bettie. We do our best work together, and it’s enough that we get to carry on doing that.” And colorist Elizabeth Breitweiser has leavened the visual narrative with nuanced shades and hues of color to model faces and other subtle aspects of the story. She’s deliberately avoiding the “glitz and glamour” of Fade Out, the team’s most recent project. She’s trying “moodier palettes and a gritty textured rendering style.” Said she: “I plan to do a lot of fun things with color psychology. ... My approach changes depending on what kind of tone Ed and Sean are setting, and I try to follow their lead as best I can. ... These two make me feel very much appreciated and like an integral part of the team.” Excellent stuff, all around. Even if I don’t care much for spooks and other worldly critters.

IN LUCAS STAND No.1, we have another story about a man who kills himself and is given a fiendish second chance. The title character is a big man with a bad temper. He spent twelve years as a Marine in “the sandbox” (Afghanistan), which ended when the Taliban “pumped six AK rounds into his spine.” They said he wouldn’t walk again, but he did—albeit in great pain. And he took drugs and poured alcohol down his throat to alleviate the pain. We meet him on the day he slugs his supervisor and loses his security gig. Driving home in a drunken rage, he inadvertently forces another car off the shelf road they’re on, and a family of four dies. Once home, he takes a pistol and shoots himself in the mouth. But he doesn’t die. Seemingly. He’s visited by a tough-talking Marine drill instructor named Gadrel who offers Lucas a deal: he can make things “right” by accepting an assignment on an unspecified “mission.” Assaulted by his demon landlord, Lucas accepts—and is immediately transported to another time and place, Nazi occupied France, where he finds himself in the Resistance. But he’s captured by the Gestapo, and he encounters some fiend-like corporalities. In prison, Gardel shows up again. And when Lucas demands a briefing on what is going on, Gardel turns himself into the devil or a good imitation thereof. And that’s where the issue ends. Three

or four completed episodes show that co-writers Kurt Sutter and Caitlin

Kittredge know what they’re doing. And Lucas is continually portrayed as a

bad-tempered bully. We pity his situation—a pain-filled life as a Jesus Hervas’ rendering of the tale is expert. His style is muscular but not heavy-handed: lines are flexible without being bold. And the pictures assume much of the storytelling role. In short, an expertly done comic book. I probably won’t get subsequent issues, but that’s because I’m not a fan of fiendish tales. On the other hand, the storytelling might pull me back.

JOELLE JONES is back with the promised sequel, Lady Killer 2. In the first issue, our heroine, professional assassin Josie, kills three people without explanation. All are “bad” people—two rude spinsterish hags, and a sexual predator of a car salesman. In some way, they all “deserve” to die in that easy quid pro quo world of funnybook morality. After killing her prey, Josie cuts them up into small pieces to dispose of them. If we hadn’t read the previous series of Josie’s adventures, we wouldn’t know that she’s likely “on assignment” in these killings. Otherwise, they would seem to be nearly motiveless murders—except for the bad manners all the victims exhibit, making them deserving of their executions. All

the killing is accomplished in the bloodiest ways possible—with a claw hammer

and a knife— and Josie spends a lot of this issue covered with spurts of blood.

And the gruesome dismembering of her victims is likewise gory. The two killing sequences—both complete episodes—are narrated by Josie, who prattles on about the requirements of her “job.” Her dispassionate, matter-of-fact business-like tone diffuses the goriness a little. But it is chiefly visual rhetoric that persuades us she’s probably a good person despite all the blood and gore: her prim demeanor and pretty face and figure are convincing—no woman who looks like this could be so bloody a killer. But she is, of course, and that circumstance creates the narrative tension that propels the tale forward. Two other complete episodes provide grace notes. In one, a six-page sequence, we meet Josie’s husband and child at a backyard dinner they’re throwing to entertain her husband’s boss (another example of male predation, he flirts with Josie). The device of the first-person narrator disappears here, so the picture that emerges is ostensibly the true picture always (ostensibly) provided by an omniscient narrator. Josie displays the perfect poise of a hostess, despite the suggestive drooling of her husband’s boss (and the nasty temper of her mother-in-law). In the other episode, a brief two-pager in a parking lot, Josie finds a note on her car’s windshield: “Sorry we missed you. We will call again.” To those of us who’ve met Josie in her previous performance the note suggests that she is acting on assignment. Writer as well as artist, Jones proves, again, an adept master of the medium. Her pictorial presentation of Josie as a polite pretty woman is flawlessly convincing; likewise, the scenes of murder and dismemberment, incongruous with Josie’s prim appearance. Jones blends words and pictures deftly throughout. In the killing and body disposal scenes, her first person narrative diffuses the blood and gore of her actions in pictures, verbal and visual combining dispassionately, almost clinically. And often, pictures do the storytelling: the wordless parking lot sequence ends with a road sign that tells us we’re in Cocoa Beach, Florida; and the last page in the book provides the cliffhanger: as Josie begins dismembering the car salesman, another car drives up in the night, panels shift focus from Josie at work to the scene the driver of the car sees, headlights illuminating Josie at her chore. And a man gets out and approaches her. What next? “Trust your instincts” Josie tells herself.

IN KINGSWAY WEST, we encounter a different Old West. What we think of as California is divided into a couple of sections, north and south. The northern section is ruled by the Queen of Golden City, who commands Chinese legions; Mexicans roam the southern part and “the Wild.” Some rebellious Chinese are Freelanders, and they resist the Queen’s rule. A state of war exists between the Chinese and the Mexicans over control of “red gold,” a substance with mysterious powers. Freelanders resist choosing sides. Kingsway West is one of the Freelanders, and he is a wanted man because he helped the Freelanders in their resistance. In the opening sequence of the book, a band of the Queen’s men try to arrest Kingsway but he kills them all, getting wounded in the process. He is found by a young Mexican woman named Sonia, who nurses him back to health. The narrative jumps five years into the future, when Kingsway and Sonia are married. He’s out hunting and a Chinese woman accompanied by a small dragon (we’ll call her the Dragon Lady because, as yet, she has no name) comes upon him. She’s looking for him, she says, but doesn’t know what he looks like. She wants to recruit him to fight the Queen. As she leaves, Kingsway thinks about killing her to prevent her from finding who he is, but he stops when he notices smoke, rising from where he and Sonia have their home. He goes looking for her. Meanwhile, the Dragon Lady is captured by a bunch of the Queen’s soldiers, who beat her when they realize she’s a Freelander—and she has some red gold. They threaten to cut off her hands if she doesn’t tell them where the red gold is, but just then, Kingsway comes upon them and stops them momentarily. When they are about to cut off one of the Dragon Lady’s hands, Kingsway pulls his gun and kills them all, rescuing the woman. He then turns his pistol on her and demands that she use the tracking device she has to find his wife who went missing when their house was burned down. Then we meet Dr. Uhrmacher from New York, the man whose theories about red gold have sparked the war. He intends to conquer the Chinese and the Mexicans, and he sends a winged woman flying off to find some targets. Kingsway and the Dragon Lady? And there the issue ends.

Mirko Colak’s pictures are a joy to look at. He’s deft at both distances and close-ups, and he varies camera distance to set the scenes and to emphasize emotional intensity and adjusts page layouts to accommodate his camera. In short, his storytelling is flawless. The joy, however, arises from contemplating the assurance of his line, its waning and waxing, embellished by just the right amount of feathering and shadowing. I’ll be back.

CONTROL seems to be an old-fashioned cops and killers romp. It opens as a bad guy is hanging another guy, hoping to get information from him. Fairly gruesome imagery—the guy with a noose around his neck while standing on a rickety stool. Then a couple cops coming knocking on the door, and the scene shifts to a poolroom where two cops, Mitch and Kate, partners, are playing pool. Their conversation, which explores Kate’s reticence, is interrupted by a call that takes them to the opening scene, where they discover the guy hanging, albeit still alive, and two shot cops on the floor. Kate grabs the hanging guy by the legs to lift him slightly, and Mitch leaves in pursuit of the bad hangman. When he finds him, the bad guy shoots and kills him; meanwhile, Kate gives mouth-to-mouth to the erstwhile hanging man until the medics arrive. Back at the station, Kate is admonished by her captain, who evidently expected her to follow Mitch, providing the backup that might have saved his life, instead of staying behind to rescue the hanging guy and, subsequently, the still breathing cop. Their conversation is adversarial and represents a completed episode, a fairly typical encounter between a smart cop and a bureaucratic supervisor who is an asshole, which shows Kate to be smart as well as capable. She’s assigned a new partner, Doherty, from another precinct. They inspect the crime scene together in another of the issue’s completed episodes. Their relationship as well as their relative expertise is demonstrated adequately. They find a cell phone which gives them an address—a hotel and room number. They go there and bust in, finding a U.S. Senator, naked, in mid-rear entry with one of two dominatrixes in the costumes of their roles. The other woman holds a whip. The Senator says: “This, uh —this isn’t what it looks like.” Writers Andy Diggle and Angela Cruickshank keep the story moving, switching from one locale quickly to another, one episode to a succeeding one, and Andrea Mutti’s visualizations are deft deployments of the medium’s usual resources—narrative breakdown and panel composition (camera angles and distances) with minimum reliance upon varying page layout. Her linework, however, relies upon a line much too thin and unvarying for my taste; but she compensates with liberal use of heavy shadowing. She habitually fills blank spaces with splashes of dry brush, a little annoying. In short, a suspenseful story, well executed. I’ll be back if only to learn what the Senator thinks he’s doing that isn’t what it looks like.

THE VIOLENT is thoroughly vile. I’m so repulsed by the first issue that I won’t be back. Co-creators Adam Gorham (who draws it) and Ed Brisson (who writes it) present a dysfunctional family, mother and father former drug addicts, who have a toddler daughter. The father, Mason, is just recently returned from a hitch in the hoosegow, and although he seems to be trying to get ahead, he’s also possibly casing houses for burglary while working as a mover. Becky, his wife, works nights cleaning offices. They’re barely existing. Mason can’t stay away from old friends and habits, and he even leaves their daughter, Kaitlyn, alone and unattended while meeting an old friend who, drunk, phones him, pleading that he’s in distress and needs help. When Mason returns to the car where he left Kaitlyn, the car is empty. No Kaitlyn. Meanwhile, Becky runs into a former dealer, who gives her a “sample” for old times’ sake. When her paycheck comes up short, suggesting that the rent won’t be paid—again—this month, she tilts in the direction of a relapse. In short, the whole enterprise is depressing in the nth degree. And when Kaitlyn turns up missing in an unsavory neighborhood, that’s it for me. I’m outta here.

AND NOW, THE OTHER SHOE. I said last time that I’d return for a look at The Fix, and here it is. The book is up to its fourth issue as I write this, and it’s four issues of propriety-daunting shenanigans so cynical and self-serving that the series is hilarious—in a wholly unconventional way, of course. The first issue begins with two ski-mask wearing guys robbing the folks in an old folks home. How low can you sink as robbers? But their actual target in the home is a retired criminal who has a cash stash the robbers want. As they uncover the hiding place, the old guy wakes up and reveals the shotgun he keeps under his bedclothes. He lets fly, and they run off with as much of the cash as they can grab and carry. It turns out that the two robbers, a black (or Mexican?) named Mac Brundo and a white guy named Roy (whose last name I haven’t found yet and whose narrative captions tell the story), have a day job: they’re cops. Roy eventually gives us the benefit of a review of his early life during which he played cops and robbers like all kids, and he decides that if you want a life of crime, it’s best to be a cop. Says Roy, in another of a continuing display of cynicism: “I mean, who gets to break the rules more than the guy who makes them? [If you’re a cop] nobody tells you want to do. Hell, you tell them what to do. You get to beat up whoever you want. You can even shoot them sometimes.” And you get away with it. Roy and Mac are robbing money to pay off their debt to another guy, Josh, a stone-cold killer and loan shark, who, by the end of the issue, has proposed that the two smuggle some stuff through LAX in order to pay him back. Their pursuit of this objective—which includes getting a dog that might be a drug-sniffing dog—takes the next two or three issues. So far. Another of this lawbreaking team is Donovan, a fast-talking con-man, womanizing self-proclaimed movie producer, who meets Roy and Mac when he’s been arrested for dismembering a store by driving a car into it, screwing a manikin, drinking bathsalts, and falling into a drunken sleep clutching a baby doll. They let Donovan off with a warning because he’s convinced them to join him in one of his movie scams—namely, submitting a script or treatment for which studios pay money up front, whether they use the material or not. The two cops will supply the material by writing up the things they’ve actually done. The movie, then, will be “inspired by true events,” a sure-fire winner among movie moguls. But that’s just the beginning. Over the next couple issues, Roy gets an off-duty well-paying security gig by framing a fellow officer who has that assignment. This officer is a model law enforcer and a wonderful husband and father—flawless, in fact. But Roy manufactures a connection between this incomparable stalwart and a crime. The guy is arrested and taken off to prison, his livelihood and reputation ruined. Roy has destroyed the guy in order to get that good-paying gig. And the gig almost gets him killed. But the person he is to guard is a doped up tattooed teenage female delinquent who causes havoc wherever she wanders. Robbers who break into her apartment kill her accidentally, and Roy, who was hired to prevent such an outcome, barely escapes in a hail of bullets with his life, saying (with typical accuracy), “What the fuck was that?” You must read this artful claptrap to believe it. Sheryl, the IA officer assigned to Roy and Mac, seems to be a partner in their criminalities but recognizes the colossal stupidity of the duo’s actions. Although Roy supplies the running captions that ostensibly explain what he and Mac are doing, the pictures often contradict the soaring rhetoric of Roy’s words.

In short, a wonderful send-up, written by Nick Spencer and drawn by Steve Lieber, who was interviewed recently in Image+. The Fix his interviewer describes as “a comedy of errors, if ‘disastrous decision-making from top-to-bottom’ counts as an error.” How do Lieber and Spencer find the comedy in this walking talking tragedy? “It’s kind of how I’ve always approached life,” Lieber says. “And I’ve been quoting Douglas Wolk a lot on this: there’s a lot of fun in watching characters act like themselves. Just about everyone in this comic is an asshole. But they’re all very different assholes. A lot of the comedy comes from knowing these characters, and finding the thing for them to do that’s unexpected but exactly right.” Lieber has called his art treatment in the series “willfully and decisively bland” because, he explains, he foregoes fancy stuff: “I’ve read a lot of comics where the job of the art is to provide spectacle. I’m talking about the visual equivalent of empty calories. The art needs to be super-impressive to compensate for the complete lack of anything substantial in the characters or story.” But when you have good, living and breathing characters, you don’t need flashy rendering—“stuff that draws the reader’s attention away fro what’s happening in the story, and it can absolutely kill a joke.” But he and Spencer have a good story and good characters. So what Leiber does, he does to serve the story. “We’re doing comedy and crime,” he goes on, “and both of those genres are at their best when they focus on close observations of people and situations. We’re here to express character through action, not virtuosity through technique.” Couldn’t have said it better myself. The Fix. Worth checking out.

AND THEN, we have The Black Monday Murders. An unsual book, both in format and in theme. Thumbing through the book, we pass pages of comic book art (heavily shadowed, almost black) interspersed with pages of typewritten text of lists and archane-looking symbols. The story begins in the offices of an investment bank on October 24, 1929—Black Thursday in American financial history—when Charles Ackermann, one of the ring of rulers of a secret monetary cabal, dies after spontaneously bleeding profusely through the nose. This episode is followed by some pages of typewritten text that list characters and their roles in the mysterious club plus explications of things we don’t know the significance of yet. Such things as “Death March,” defined as “throwing bodies at the problem.” The legend of stock market players throwing themselves out of windows because the “crash” ruined them is exposed as a myth (or is this merely part of the book’s fiction?). But some of the conversation among characters seems to be about “throwing bodies out of windows.” (Death marching them?) The rest of the book takes place in 2016. During a lecture at what appears to be a business school class, we learn that the Caina and Kankrin investment banks merged at the fall of the Berlin Wall, not so much a political event as a financial one, creating a global market—and Caina-Kankrin seems to control that market. And much else. Then we plunge into the murder mystery. A black detective, Theodore (Theo) Dumas; reputed to have some special powers of knowing and understanding things, knows the dead body is that of the managing partner of the world’s largest investment bank, Caina-Kankrin. It’s Daniel Rothschild, erstwhile occupant of the Ascendent Chair, the spear, “the voice of Mammon on the Caina board,” the big boss who gives the orders. His corpse is suspended from ceiling, naked, as if, before dying, he were engaged in some perverse sexual play (his sister refers to his “trafficking in cock”), and his arms have been arranged to point to eight o’clock, which Dumas sees immediately. And he also knows that something will happen that night at eight o’clock, so he will return to see what it is. Then we meet Rothschild’s sassy sister, Grigoria, who is “called” to assume the now vacant Asscendent Chair. And when Dumas comes back at eight, he is confronted by a glowing presence, surrounded by some of those cryptic symbols—the first manifestation of one of the book’s central ingredients, magic. And there the book ends. We have more bafflement in this first issue than is usual. But completed episodes show writer Jonathan Hickman and artist Tomm Coker have command of the medium, and at least some of the puzzle is explained, albeit cryptically, during the lecture, one of the completed episodes. But much remains to be revealed. Coker’s work is deeply shadowed; we never make out all the features of Dumas’ face: as a black man, he’s already dark, and the shadowing increases that aspect of the treatment of his physiognomy. The storytelling—which may be what Hickman, in an interview in Image+, calls “design”—is accomplished by both writer and artist. “I’m doing all the design,” Hickman says, “but Tomm is so strong in that area that I’m bouncing stuff off him.” And: “Tomm’s got that scratchy noir thing going on, which is perfect for this story.” And nearby, we’ve posted sample pages to illustrate both Coker’s manner and the book’s unique approach to storytelling, combining pages of pictorial narrative and typewritten text.

For Hickman, the book “is basically a story about two people: the detective trying to solve the murder and the case’s only surviving family member [Grigoria], who is neck-deep in the intersecting worlds of finance and magic. ... In regards to the overall story, there’s the whole bit about the detective falling into a secret world he knew nothing about, but the rabbit hole in The Black Monday Murders is really just the gravy. The meat of the thing is in the magic system that supports the story. How do you get in? Can you ever get out? What’s the cost?” It’s a book, he says, “about money as an actual force of nature.” The Image+ editors say the book “is classic occultism where the various schools of magic are actually clandestine banking cartels who control all of society: a secret world where vampire Russian oligarchs, Black popes, enchanted American aristocrats, and hitmen from the International Monetary Fund work together to keep all of us in our proper place.” That gives the whole thing away better than anything in the first issue or anything Hickman says. That describes the book but we must await further issues to see how Hickman works it out. He talks about how he gets ideas and develops them. “For me, conceptually, almost every new idea I have for a book happens tangentially. I’ll be reading something or watching television ... and something will hit me and I’ll get this wave of an idea. I’ll stop and write it down, and if it’s a good one, it’ll stay with me for a couple days or weeks. If it sticks and I can’t stop thinking about it, then I’ll actually take a day to really think about only that. And then, if it’s gold, usually in one sitting, I’ll get the inciting action and, more importantly, the ending. Then I do the actual research. Which, for this one, was extensive.” Hickman has said that this book is “an actual manifestation of how I think a comic book should be done.” He explains: “I’ve had pretty strong opinions on what could be done since my very first book, The Nightly News. I think there’s a sweet spot of delivering information and, more importantly, telling a stroy, that we don’t see enough of. ... Each issue of The Black Monday Murders is 20 to 30 pages of comic narrative and 20 to 30 pages of ‘other stuff’ that also serves as a narrative, but in a less linear way.” Undoubtedly, The Black Monday Murders is a book carried on “in a less linear way.” And it’ll be fascinating to see how Hickman carries it on through future issues.

Quotes & Mots SOME THOUGHTS ON THE REAL WORLD By One Who Glimpsed It and Fled Kenyon College Commencement Address May 20, 1990 By Bill Watterson, a Kenyon Alum Excepts—: As my comic strip became popular, the pressure to capitalize on that popularity increased to the point where I was spending almost as much time screaming at executives as drawing. Cartoon merchandising is a $12 billion dollar a year industry and the syndicate understandably wanted a piece of that pie. But the more I thought about what they wanted to do with my creation, the more inconsistent it seemed with the reasons I draw cartoons. Selling out is usually more a matter of buying in. Sell out, and you're really buying into someone else's system of values, rules and rewards. The so-called "opportunity" I faced would have meant giving up my individual voice for that of a money-grubbing corporation. It would have meant my purpose in writing was to sell things, not say things. My pride in craft would be sacrificed to the efficiency of mass production and the work of assistants. Authorship would become committee decision. Creativity would become work for pay. Art would turn into commerce. In short, money was supposed to supply all the meaning I'd need. What the syndicate wanted to do, in other words, was turn my comic strip into everything calculated, empty and robotic that I hated about my old job. They would turn my characters into television hucksters and T-shirt sloganeers and deprive me of characters that actually expressed my own thoughts. On those terms, I found the offer easy to refuse. Unfortunately, the syndicate also found my refusal easy to refuse, and we've been fighting for over three years now. Such is American business, I guess, where the desire for obscene profit mutes any discussion of conscience. ... Creating a life that reflects your values and satisfies your soul is a rare achievement. In a culture that relentlessly promotes avarice and excess as the good life, a person happy doing his own work is usually considered an eccentric, if not a subversive. Ambition is only understood if it's to rise to the top of some imaginary ladder of success. Someone who takes an undemanding job because it affords him the time to pursue other interests and activities is considered a flake. A person who abandons a career in order to stay home and raise children is considered not to be living up to his potential-as if a job title and salary are the sole measure of human worth. You'll be told in a hundred ways, some subtle and some not, to keep climbing, and never be satisfied with where you are, who you are, and what you're doing. There are a million ways to sell yourself out, and I guarantee you'll hear about them. To invent your own life's meaning is not easy, but it's still allowed, and I think you'll be happier for the trouble.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution

Sensation controls journalism in this country. We’ve always known it, but it has become even more apparent during the present political season. Sensation sells newspapers and attracts viewers, and since journalism is a profit-generating profession (not a fact-finding and reporting one), sensation is its raison d’etre. Donalt Rump gets more airtime on tv and column inches in newspapers than Hillary Clinton. And its better coverage, too—mostly uncritical or at least neutral. The Trumpet makes news every time he burbs out some new affront to common sense and political wisdom. Everything he says is calculated to be outrageous enough to attract press attention. And nothing he says is much questioned or fact-checked in the same coverage. So he commits some new atrocity every day in order to stay in the headlines—which he knows he can do but only by being sensational. Hillary, on the other hand, attracts the attention of the press only with the unending announcements of some new e-mail sin or Clinton Foundation malfeasance. All the Hillary coverage helps to nurture and to create the feeling among potential voters that she’s a borderline criminal, breaking laws helter-skelter on every hand. She’s quoted but, apparently—as with the Trumpet—never fact-checked. If she were fact-checked, it would doubtless reveal that she’s correct when quoted. If the Trumpet were fact-checked, it would reveal how great a blustering fraud he is. So sensation creates Trump; sensation destroys Hillary.

PERSIFLAGE & FURBELOWS How serious are we about Donalt Rump’s presidential ambitions? Do we really want a Prez with Trump’s fuzzy hair-ball coiffure? Really? Jimmy Fallon gave the Trumpet’s “do” a test on the “Tonight Show” Thursday, September 15, mussing it up pretty thoroughly on camera—at Trump’s invitation. Surprise—it’s not a comb-over. No bald spot appeared. At least not on the front half of the skull. The hair, though, is very long and silky. But if there’s no bald spot, what’s Donalt doing with the hair-do? What’s its purpose?

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy IN PRESIDENTIAL

POLITICS, it was the Trumpet’s month again. Every outrageous blast reported

enthusiastically by a avaricious press. And editorial cartoonists delighting in

the spectacle of Trump’s hair and mouth. Everyone else is having so much fun

with Trump that I had to join in the festivities—with the accompanying

extravaganza. But

the month was not all about the race for the White House. Elsewhere in the

world, other events were taking place—among them, the continued bombing of

Aleppo in Syria. And the most powerful image of the month was the photograph of

the 5-year-old Omran Daqneesh, his mop of hair, his bloodied face, his blank

look, sitting on an orange seat in a rescue van in Aleppo. We should be weeping, grief-sticken. We should be weeping with shame. Surely humanity has something better to offer children than strife so monstrous as to destroy feeling. But instead, we are roaring jubilantly over the latest Trumpery.

IN OUR FIRST

VISUAL AID, R.J. Matson gets things going at the upper left with a

picture of lawmakers returning to their so-called “work” at the nation’s

capital—specifically, hiding from Trump, ignoring him because they are afraid

to be either for him or against him. Next around the clock, Walt Handelsman employs one of the graphic earmarks of the medium to illustrate Trump’s lack of specifics in policy statements. And immediately below, Tom Toles uses speech balloons for a somewhat different effect, exemplifying Trump’s inability to decide what he actually “thinks” or believes about the many issues swirling through the campaign. Finally, at the lower left, Mike Luckovich’s visual metaphor assesses the effectiveness of the many Hillary scandals that the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm has launched. They’ve all fallen to pieces upon examination just like those women’s purses sold by street vendors. But Hillary finally waltzed into the maw of the Trump campaign with an ill-advised (probably not advised at all) comment at a fundraiser a week or so ago: “You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump’s supportrers into what I call the ‘basket of deplorables.’ Right? The racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic—you name it.” Perfect for the Trumpkins. They lept up as man, shieking and deploring Hillary’s obvious “contempt for everyday Americans”—namely, those Trump supporters. Well, it was a mistake, no doubt. A colossal mistake. It gave Trump and the Trumpkins fodder for hours and hours of railings and rallings against Hillary. But it wasn’t, actually, much more than a strategic error. First, Hillary began by acknowledging that the statement was a “grossly generalized” one. In effect, she admitted at the onset that it was an exaggeration. For rhetorical effect, probably: she was, after all, speaking at a fundraiser of kindred souls. Second, she wasn’t wrong. As Greg Sargent said at the Washington Post, “Her underlying characterization of the general nature of many of Trump’s campaign appeals—and her related observation that they really are successfully playing on the baser instincts of an untold number of Trump’s supporters—are 100 percent accurate. ... Yes, Trump’s campaign [as we’ve known for months] is functioning as a vehicle for mainstreaming fringe sentiments. ... “The underlying argument here—that Trump is running a bigoted campaign that tries to prey on legitimate grievances and bigotry alike by scapegoating minority groups—is inarguable, and the reality it identifies is far worse than Clinton’s broad-brush over-reach was. If anything, ‘deplorable’ is too mild a word for it.” And the Los Angeles Times’ David Horsey, who is, among other things, an editorial cartoonist, added his essay on the topic, which we repeat here—:

The Deplorables and the Polls Clinton quickly apologized for using the word “half,” saying she meant to criticize a much smaller cadre of right-wing fanatics who are riding the Trump bandwagon. Still, she was not entirely off the mark. It is clear from evidence gleaned from poll after poll that at least half of Republicans hold some curious ideas. More than 50%, for instance, are convinced that Obama is a Muslim born somewhere outside the United States. The Vox website has gathered together several national public opinion polls that compared the views of Clinton and Trump voters. They are instructive. ... Polls show that Trump voters are much more likely than Clinton voters to have negative views of Mexican immigrants — and not just the illegal ones. They also are much more likely to think African Americans are less smart and more lazy, rude, violent and criminally inclined than white people. While 58% of white Americans say they harbor some level of resentment against blacks, a whopping 81% of Trump voters expressed such resentment. The Vox analysis importantly notes that this does not mean most Trump voters are overtly racist or horrible people. More precisely, these poll results are an indication that a big share — half or more? — of the folks voting for Trump are fearful and angry about social and cultural changes that they believe are shifting the country away from what it has been. “This is why a Trump surrogate warned that if Clinton wins the election, there will be ‘taco trucks on every corner,’” the Vox analysis said. “The worry isn’t that delicious food will be everywhere, but that the cultural makeup of America will dramatically change. …” Those in the Trump camp, of course, would argue this is not fearfulness but wisdom. So, that is what this election has come down to: a furious contest between two very different visions of America’s future. Whichever way the election goes, it will be a victory of one vision over another, but there is no guarantee that it will be a choice that confirms the inherent wisdom of the American people.

RETURNING to

our Editoonery Department, Joel Pett gives us (almost) the last word on

“deplorables,” showing, in his cartoon at the upper left, that Hillary could

have gone on lwith a longer list. Still, the “deplorables” remark was a blunder of “yuge” proportions. And it would have festered on for weeks, undermining Hillary’s credibility on all sides, except— Except that, before much more benefit could be wrung from the misstep, Hillary withdrew from a 9/11 celebration and wobbled as she approached the van she boarded. Her departure, a little early I gather, is perfectly understandable: she’d been standing in the heat for 90 minutes and she’s 68 years old. But then it came out that she also has walking pneumonia—and, horrors, had been keeping it a secret for The American People since Friday, when she’d been diagnosed with it. Given, as Tom Stiglich remembers for us, that Hillary’s health has been a preoccupation of an appalling number of Trumpkins for weeks (months, maybe), disclosing that she is actually ailing from something would have been, nearly, suicidal. I suppose. Suddenly, the health issue supplanted the deplorables issue—probably with an ultimately beneficial effect on the Hillary campaign. Questions about health will be easier to deal with than the fall-out from the deplorables remark and what that reveals about Hillary’s attitude toward vast quantities of voters—Trump’s, anyhow. Gary Varvel provides a highly comical portrait of the Trump campaign trying to control the Trumpet to prevent him from responding by saying something as self-destructive as Hillary’s “deplorables.” By its comedy alone, it is a memorable image. Winding up this episode, David Fitzsimmons summarizes the “health concerns of 2016.” The only authentic one is Hillary’s; the rest are barbs of satire flung at various corners of the campaign. And, as always with Fitz, nicely—brilliantly—drawn. Ailing

candidates and deplorables, however, were late in arriving in the race for

Prez. Immigration, however, has always been with us and is still the Trumpet’s

central issue, but even on this, as with virtually every other position he

enunciates, it’s difficult to understand what the candidate’s actual position

might be—as Stuart Carlson so vividly demonstrates with pictures of

Trump the whirligig. In a series of speaking images (i.e, a comic strip), Matt Bors characterizes the anti-immigration xenophobes and pokes a big hole in Trump’s immigration policy. He needs the format to set up for the punchline. Suddenly, the anti-PC Trump is revealed as PC to the core in his chief issue. Next to Bors is Wiley Miller’s take on the “wall.” “Genesis” indeed. The invocation of the Biblical Flood puts Trump’s immigrants in the same class as all those sinners God wiped out when he saved only Noah and his immediate family. And all those animals. Editoonists

continue to have fun with the Trumpet’s unusual hair style—which, as Walt

Handelsman shows us at the upper left of our next visual aid—has assumed a

politically awkward configuration. In 2008, Robinson reports, a federal lawsuit alleged that the Trump SoHo luxury hotel development in Manhattan was partially financed by a “shadowy Iceland-based corporate identity,” backed by Russian financiers “in favor with Putin.” Trump was not charged with any wrong-doing, but the suit “raises an obvious question: to what extent are Trump and the Trump Organization dependent upon Russian investment?” To this, we add (as Robinson does) a remark by Trump’s son Junior, who said, in 2008, “we see a lot of money pouring in from Russia” to the Trump Organization. So—I ask again—to what extent would a Trump White House foreign policy toward Russia be influenced by his company’s finances? Or, as Robinson says, “Trump’s chest-thumping ‘America First’ attitude toward the rest of the world seems to make an exception for Russia, and we need to know why. Trump supporters [Trumpkins] will say I’m speculating without the relevant facts. I say provide them: release the tax returns, now.” Next around the clock, Mike Luckovich uses the vast number of U.S. Olympic medals to make the Trumpet’s assertion worthy of scoffing laughter. And below that, Nick Anderson uses Jabba the Hut as a visual metaphor for Fox’s Roger Ailes, making the fat would-be lothario grossly sleezy in his predations. And this obesity, Anderson notes, is the creature Trump has chosen as a new addition to his campaign counselors. Ailes the Hut will advise Trump on how to capture the women’s vote. As if Trump needs any advice in this area. As if Ailes could give it. At the lower left, Ted Rall runs through a series of “changes” Trump might effect in his presentation that would affect American voters, proving, by the transparently pandering process, that American voters are stupid enough to fall for anything. Alas, for a large percentage of voters, that may well be true—hence the effectiveness of that old trick of the demagogue, tell ’em what they want to hear. So he says one thing one day to one audience; on the next day, to another audience, he tells them something else, often something contradictory of what he said the day before. We’ve seen this guy before. And we’re seeing him now. We’ve witnessed this axiom in action lately as the Trumpet made special appearances before African American audiences and Hispanic American audiences, seemingly to appeal directly to each of these groups that he’d treated badly in other venues. But he was not, really, doing outreach to groups he’d slighted previously. This was “performance empathy,” said Jamelle Bouie at Slate.com. By appearing before such groups, “Trump is merely trying to convince college-educated, right-leaning whites that he’s not a racist so it’s safe to vote for him.” Greg Sargent at the Washington Post agreed: Trump desperately needs the votes of well-educated, suburban whites who have been turned off by his blatant denigration of Hispanics and Blacks.

IN OUR NEXT