|

||||||||||||||||||

Opus 339 (April 19, 2015). This time, we solve the mysteries in the cartoon origin of the Teddy Bear (replete with previously unknown facts!). Plus: cartoonists’ fate in other oppressive countries, nominees for the Silver Reubens from the National Cartoonists Society, Trudeau criticizes Charlie Hebdo for abusing satire, Frank Cho’s Manara cover spoof, Eric Larsen vs. “the vocal minority”; and reviews of funnybooks (Lady Killer, Howard the Duck and others). And more, always more—including reviews of 16 books and 7 obituaries (all listed immediately below). Here’s what’s here, in order by department—:

NOUS R US Trudeau: Charlie Hebdo Went Too Far* Political Cartooning in Today’s World The State of Magazine Cartoons Rare New Editoonist Gig

CARTOONISTS IN OTHER LANDS Turkish Cartoonists Fined for Obscene Gesture French Jewish Cartoonist Arrested for Anti-Semitism Malaysian Zunar Faces 9 Counts of Sedition Ecuadorian Cartoonist Censored Swedish Conceptual Artist Vilks Honored

IN THIS COUNTRY: Censoring Palomar Fails—For Now

NOMINEES FOR NCS SILVER REUBEN

ODDS & ADDENDA New Wimpy Kid Book Pentagon Dropping Cartoon Leaflets in Syria Matt Wagner on Will Eisner’s Spirit Alan Moore’s Jerusalem at Publisher Tintin Pulled Then Reinstated in Canadian Bookstore Chain Bill Watterson Interview Doug TenNapel Nominated for Emmy

THE ABUSE OF SATIRE *Trudeau’s Full Text Verdict on Charlie Hebdo Reactions

COMICS JOURNALISM IS DIFFERENT. OR NOT.

They Shoot Black People, Don’t They? Keith Knight on the Road

COVER CONTROVERSY Batgirl No.41 Frank Cho’s Manara Spoof Dennis the Menace and Archie

APPEASING THE “VOCAL MINORITY” Erik Larsen Is Against It NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Zits and Pickles Peeing

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Really Short Reviews Of—: Jack Davis: Drawing American Pop Culture, A Career Retrospective The Cisco Kid, Vol. 1, 1951-1953 Wally Wood: Classic Tales of Torrid Romance Wally Wood: Strange Worlds of Science Fiction Cannon The Art of Ramona Fradon Berlin: Books One and Two

BOOK MARQUEE Slightly Longer Reviews Of—: Heroes of Comics: Portraits of the Legends of Comic Books Cats, Dogs, Men, Women, Ninnies, Clowns: The Lost Art of William Steig Sherlock Holmes in a Study in Scarlet (Gris Grimly) Lincoln for Beginners Perfect Nonsense: The Chaotic Comics and Goofy Games of George Carlson

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Percy Crosby’s Skippy, Jack Farr, Theodore Roosevelt Caricatures

BOOK REVIEWS Reviews At Length Of—: Bully! The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt (with Cartoons and the Origin of the Teddy Bear) Foolbert Funnies: Histories and Other Fictions (Frank Stack)

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS (Graphic Novels) Law of the Desert Born The Sculptor

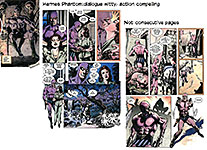

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Discussions Of—: Lady Killer King Comics: Prince Valiant, The Phantom, Mandrake, Jungle Jim, Flash Gordon Howard the Duck Zombie Tramp

PASSIN’ THROUGH Jim Whiting Irwin Hasen Fred Fredericks Jim Berry Yoshihiro Tatsumi Roger Slifer Stan Freberg

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

TRUDEAU: CHARLIE HEBDO WENT TOO FAR Doonesbury’s Garry Trudeau was at Long Island University on April 10 to receive the George Polk Career Award, an award conferred annually to honor those whose careers represent special achievement in journalism. The awards place a premium on investigative and enterprising reporting that gains attention and achieves results. They were established in 1949 to commemorate George Polk, a CBS correspondent murdered in 1948 while covering the Greek civil war. As we reported last time, Trudeau is the 33rd person to garner the honor, but the first cartoonist to do so. Four other cartoonists— Jules Feiffer (1961), David Levine (1965), Jeff MacNelly (1977), and Edward Sorel (1980)—have also been cited for their work in specific years, but no cartoonist until Trudeau has received the Career Award. During his remarks made in accepting the award, Trudeau reviewed his career producing one of the most frequently banned comic strips in the medium’s history—banned for saying things that too many people regarded as offensive. In that connection, he talked about Charlie Hebdo, the satirical weekly in Paris, the offices of which were attacked by Muslim terrorists on January 7. What he said about Charlie has created no little stir in cartooning circles. We have posted the entire speech below (albeit on the other side of the $ubscribers Wall); but here, we quote those of his remarks that have alarmed many (all in italics): Traditionally, satire has comforted the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable. Satire punches up, against authority of all kinds, the little guy against the powerful. Great French satirists like Molière and Daumier always punched up, holding up the self-satisfied and hypocritical to ridicule. Ridiculing the non-privileged is almost never funny—it’s just mean. By punching downward, by attacking a powerless, disenfranchised minority with crude, vulgar drawings closer to graffiti than cartoons, Charlie wandered into the realm of hate speech, which in France is only illegal if it directly incites violence. Well, voila—the 7 million copies that were published following the killings did exactly that, triggering violent protests across the Muslim world, including one in Niger, in which ten people died. Meanwhile, the French government kept busy rounding up and arresting over 100 Muslims who had foolishly used their freedom of speech to express their support of the attacks. Guided by DailyCartoonist.com’s Alan Gardner, we found the full text of Trudeau’s speech at theatlantic.com, and, as I said, we’ve posted all of it further down the scroll.

POLITICAL CARTOONING IN TODAY’S WORLD In a press release, the Library of Congress announced that Pulitzer-winning cartoonists Signe Wilkinson and Ann Telnaes will share their perspectives on the art of political cartooning and show examples of their own cartoons, starting at noon, Thursday, April 30. The event is free and open to the public. No tickets are needed. Under the heading “That’s Not Funny!,” Wilkinson and Telnaes will address several topics that currently affect a political cartoonist’s approach to his or her work. Each cartoonist will describe her initial reaction to the murders of cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris, and her responses in cartoon and other formats. They will also share their perceptions about collective responses to the events from the cartooning community. The broader, related issue of exercising freedom of expression in the art of cartooning also will be discussed by the cartoonists. Both will show, and comment on, their own cartoons that have triggered controversy and aroused strong negative and/or positive responses. Wilkinson is the editorial cartoonist for the Philadelphia Daily News and Telnaes creates animated editorial cartoons and a blog of print cartoons, animated gifs and sketches for the Washington Post. The only women so far to have won the Pulitzer Prize for their political cartoons, each also has won many other prestigious awards in the field. They are among a small number of women who pursue political cartooning as their main professional focus. Both will comment on their own experiences as women in a cartoon specialty heavily dominated by men.

THE STATE OF MAGAZINE CARTOONS Magazine cartoons have all but disappeared except in the nation’s two best venues for single-panel “gag” cartoons: they’re holding their own. I was mildly alarmed a few weeks ago when The New Yorker for March 23 arrived with only 10 cartoons, a disastrous drop from its usual 12-17 per issue. But the next issue, with 19 cartoons, brought the average back into its usual range. Playboy, the other major cartoon outlet, is still printing about 15 cartoons each issue despite the steady decline in the total number of pages. The last two issues (March and April 2015) offered 5 full-page color cartoons (plus the “pin-up” cartoon by Olivia) and 8-9 smaller cartoons and a couple of strips (including Bobby London’s Dirty Duck). Although the number of cartoons in each issue has slowly declined over the last decade or so, the ratio of cartoons to total page count (which has also declined) remains fairly steady. In the March and April issues, taken all together, Playboy averages 1 cartoon for every 8-9 pages; 1 full-page color cartoon for every 25-28 pages. In the best of all cartooning worlds, the number of pages per cartoon would be fewer. Instead of encountering a cartoon every 8-9 pages, you’d like to come across one ever 3-4 pages, say. But the March-April ratios are about the same as it’s been lately. Parade, the newspaper Sunday supplement magazine, has apparently given up on cartoons. Several months ago, it published a little booklet with a half-dozen or so cartoons in it. That exercise seemingly exhausted the magazine’s inventory of unpublished cartoons: none have showed up since.

RARE NEW EDITOONIST GIG At Cagle.com, Daryl Cagle announced that former Memphis Commercial-Appeal and the Detroit Free-Press editorial cartoonist Bill Day has taken a full-time position with the Florida web site FloridaPolitics.com. Said Cagle: “New jobs for editorial cartoonists are rare these days, and full time jobs with Web site firms are even more rare, so this is great to see! Kudos to Peter Schorsch of FloridaPolitics.com for being a brave trendsetter who sees the need and value of having a staff cartoonist and local cartoons. Bill will be drawing about Florida issues, at least five cartoons a week, in addition to illustrations for the site.” With Day’s new job, the number of full-time staff editorial cartoonists jumps from 50 to 51.

NEWSPAPER PRINT COMIC STRIPS AREN’T DEAD A Nashville entrepreneur is toying with the idea of launching a weekly 6-page comic newspaper delivered via mail. From the press release: Seeking to preserve a uniquely American art form, Nashville based media entrepreneur Logan Sekulow announced the launch of Laugh-O-Gram, a weekly, family friendly comic strip only newspaper delivered by mail. Acknowledging the importance of grassroots support, Sekulow chose Kickstarter to launch the paper. Each issue of Laugh-O-Gram will feature six full-color pages of classic and original comics. Sekulow hopes to bring the funnies to a new generation, while retaining what made them appealing to the pre-2000s generation. The paper, printed on newsprint, will be delivered directly to the mailboxes of subscribers. With traditional newspaper subscriptions in decline, Sekulow saw a need to save the “funny pages.” Classic titles include Peanuts, Garfield, Family Circus, Beatle Bailey, Amazing Spiderman, Popeye, Dennis the Menace, Zits, Ziggy, Baby Blues, Hi and Lois, The Phantom, Dilbert, FoxTrot, Nancy and more. Along with the classics, Laugh-O-Gram hopes to foster a new generation of comics through original content supplied by accomplished and aspiring cartoonists. So far, this roster includes: The Kid In Me by Noah – Celebrating the kid in each one of us. Some of us imagined being a doctor; others, an attorney. Px – The life of a punk rock misfit with a love for music. Based on the original character the Pokinatcha Punk, the icon of the band MxPx. Middle C by Jon Schneck—The unintentionally hilarious life of a brilliant middle child. ArtMan – Art History Teacher by day, Superhero… kind of. Retails – The story of a nervous turtle named Jitter making his way in the hectic world of retail and relationships. Zaob – Guerrilla warfare takes place on a grand scale between two mischievous siblings and their homeschool parents.

CARTOONISTS IN OTHER LANDS—: Where The Powers That Be Don’t Like To Be Laughed At ■ In Turkey, from Cartoonists Rights Network International: Cartoonists Bahadir Baruter and Ozer Aydogan, from the Turkish satirical magazine Penguen, appeared in court charged with “insulting” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The indictment relates to a cartoon placed on the front cover of the magazine last August, depicting the President meeting two officials outside his newly completed presidential palace. The cartoonists explained in court that the cartoon was making a comment on the victimization of journalists, the President replying to the greeting within the cartoon with “What a bland celebration. We could have at least sacrificed a journalist” —an allusion to a Muslim practice of ritual sacrifice. But the insult was conveyed by another allusion, according to hurriyetdaillynews.com. One of the welcoming officials is buttoning his jacket, his fingers making a “ball-shape,” a gesture customarily used to imply that the person being addressed is homosexual.

“If you look at the whole picture,” he explained, “you see that the joke has got nothing to do with the gesture.” Aydogan, whose idea Baruter illustrated with the cartoon, stated that the cartoon was simply a comment on the lack of press freedom in Turkey. Initially, the two cartoonists were sentenced to 11 months and 20 days in jail, but the sentence was subsequently commuted to a fine of 7,000 Turkish liras (about $2,700). Penguen said it would appeal the verdict, adding: “We will continue to draw our cartoons as we feel like. We hope this case will be the last example of the efforts to dismay the freedom of thought.”

■ Turkish President Erdogan is particularly edgy about cartoon criticism, according to Aljazeera.com. He has lashed out at Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical magazine, for its "provocative" publications about Islam, saying the weekly paper incites hatred and racism. "This magazine [is] notorious for its provocative publications about Muslims, about Christians, about everyone," Erdogan told a meeting of businessmen in Ankara recently. “This is not called freedom. This equates to wreaking terror by intervening in the freedom space of others. We should be aware of this. There is no limitless freedom," he said. "They may be atheists. If they are, they will respect what is sacred to me," said Erdogan. "If they do not, it means it is a provocation, which is punishable by laws. What they do is incite hatred, racism," he added. In solidarity with Charlie Hebdo, Turkish daily Cumhuriyet published a four-page pull-out including some Charlie Hebdo cartoons (translated into Turkish) which prompted prosecutors to open an investigation into two commentators writing for Cumhuriyet. Erdogan has sued “dozens of people” for purportedly insulting him. Speaking to Al Jazeera from Istanbul, Emma Sinclair, the senior Turkey researcher with U.S.-based Human Rights Watch, said that there was a pattern with the recent prosecutions on alleged insults towards politicians: "A lot of prosecutors seem to act on their own initiatives in opening cases. There have even been some activists, not only prosecuted but put into prison for insulting Erdogan." She added that Erdogan was not the only Turkish politician pursuing lawsuits on alleged insults of his critics. Erdogan sued Penguen in 2005 when he was prime minister for depicting him as several different animals. A court threw out the case in 2006. Most recently, 37 students and teachers appeared in court in the northern city of Trabzon on charges of insulting the president at a protest in February. A 16-year-old is also being tried in a similar case. In a case opened by Erdogan’s lawyers in February, former Miss Turkey, Merve Buyuksarac, faces up to 4-and-a-half years in prison over social media comments allegedly insulting to Erdogan.

■ In France, from Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com: A French Jewish cartoonist was arrested on charges of Anti-Semitism for a cartoon he drew in 2011. Anadolu Agency reported: “The environment after the Charlie Hebdo attacks is just like post-September 11. You are either Charlie, or a terrorist,” cartoonist Zeon said in an interview with the Agency. After the 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S., then-President George Bush had famously drawn the red line as “either you are with us or you are with the terrorists” at the start of his so-called war on terror. The Jewish cartoonist was arrested in early March and sent to court in Paris for his alleged “anti-Zionist” drawings, in particular for a cartoon he made in 2011 that depicted a Palestinian child being stabbed by an Israeli-flag shaped knife. His arrest followed a complaint that was reportedly filed by the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism. Zeon alleged that his arrest was ignored by the mainstream French media since talking about his case would contrast his situation to the January 7 attacks on the French satirical magazine known for printing controversial material, including derogatory cartoons of Prophet Muhammad in 2006 and 2012. Firstly, said Gardner, free speech should prevail in a case like this. Secondly, if free speech isn’t the norm, what about statute of limitations on things people say. 2011? What if in the last four years, he’s changed his mind on an issue?

■ In Malaysia, from the malaymailonline.com: Political cartoonist Zulkiflee SM Anwar Ulhaque, aka Zunar, has been charged with 9 counts of sedition, all of which, he says, are part of the government’s effort to silence him from criticizing the Barisan Nasional regime. If he is found guilty on all charges, he would be jailed for a maximum of 43 years. “At the very last minute,” Zunar said, quoted in theadministrator.com, “they changed the original one charge to nine charges, resulting in RM45,000 bail (later reduced to RM22,500) by the court). This was clearly to punish me even before trial. “The charges are evidently politically motivated, and a new level of intimidation and harassment against me,” Zunar added, “—part of a grand modus operandi to stop me from drawing critical cartoons.” Throughout his career as a cartoonist, Zunar’s human rights have been under attack by the Malaysian police and authorities who say his cartoons are "detrimental to public order." According to the administrator.com, Zunar has been detained twice under Malaysia’s archaic Sedition Act. Five of his cartoon books have been banned. His office in Kuala Lumpur has been raided a few times. It is not just Zunar who is being targeted; the printers, vendors, and bookstores around the country that carry his cartoon works, have been harassed. Their premises have been raided and they have also been warned not to print or carry any of his titles. Zunar is undeterred. “The use of the Sedition Act came as no surprise for me as in a corrupt regime, the truth is seditious,” he said, quoted by themalaysianinsider.com. He vows to continue. “I will not be silenced. I will keep exposing the corruptions and wrong-doings of the BN government. I will keep drawing until the last drop of my ink.” Meanwhile, he is suing the the police for damaging the original art of a cartoon that was seized in September 2010, along with 66 copies of his book, Cartoon-O-Phobia.

■ In Ecuador, from Comic Book Legal Defense Fund: Ecuadorian cartoonist Xavier Bonilla (aka Bonil) is a frequent target of governmental censors in a country that has become more repressive since Rafael Correa became president in 2007. In the guise of “democratizing” the press, he issued a series of new communications laws that have the effect of restricting freedom of the press. Said Caitlin McCabe at CBLDF: “Cartoonist Bonil, who pulls no punches when criticizing the government in his cartoons, was recently charged with ‘socioeconomic discrimination’ and fined $500,000 by the Ecuadorian government in an attempt to stifle free speech. This is not the first time that Bonil and his work have come under attack, nor will it probably be the last.” “There

have always been tensions between the government and the press,” Bonil

commented during his interview with Freedom House. “This is the first time in

the country that there is a specific governmental policy directed to control

the media. The ‘democratization’ did not mean to expand the number of people

talking, but to limit the media to whomever the government wanted to hear.” Bonil fears that the situation is only getting worse: “I see the situation deteriorating. In 2014, it became more evident that the government is intent on punishing and oppressing critical voices from media and civil society, as well as private citizens who are on Twitter or social media. This illustrates the growing intolerance against dissident or critical voices. There has also been an increase in the fines against media companies. “Paradoxically,” he adds, “the role of a cartoonist is to be a dissident, to not have a role. This allows me to see what is happening from outside the system. It allows me to be a critical voice, to be a discordant voice in the choir, the choir being the unanimous voice of the regime.” Bonil’s troubles have lately stemmed from beyond his country’s borders. El Universo, the newspaper that often prints his work, received a letter of warning from supports of the Cutthroat CalipHATE: “Once again, the cartoonist for El Universo, ridicules the Islamic State with his drawings, and names Allah. ... The next time I see a cartoon similar to what I have mentioned in your journal, I will call my friends in Syria to alert them about what is happening in Ecuador, so they can come and kill the wretch who is doing this. ... [They will] make an attack against the newspaper El Universo such as the one that happened in France with the magazine Charlie Hebdo. ... This is the last time, Bonil, or you will regret it.” The letter was a response to a cartoon entitled “Fundamentalism and Barbarism,” McCabe explained, “which was published on March 1. It depicts ISIS group members performing destructive acts with the caption, ‘Let’s put an end to cultural expressions of the infidels!’ The second panel shows a man in a turban, ostensibly a member of ISIS, sitting at his computer cursing, ‘By Allah! The Internet is slow ... I cannot submit our video to Twitter and Facebook.’” Bonil commented that the threat comes from a “climate of hostility and harassment against citizens and journalists,” noting two other recent cases of governmental acts against cartoonists for their “anti-governmental” work. Bonil says he will continue to draw despite threats and actions against him. Said McCabe: “The state of freedom of speech and expression is in a precarious position in Ecuador.”

SWEDISH CARTOONIST HONORED Swedish conceptual artist Lars Vilks, who has been dealing with death threats from Muslims in Europe ever since drawing a dog with Muhammed’s head in 2007, received the Sappho Award from the Free Press Society of Denmark. The prize is for courage in the advocacy of free speech and is named after the Greek poet who serves as the Society’s icon. Said Vilks upon receiving the award: “I am an artist and my artwork is probably difficult to understand. Many have tried to understand what that dog is about. But I don’t even understand it myself. Some believe that it is a form of blasphemy, but I say that it is what art is all about. I show my things to the world and then the world must interpret it.” Vilks has been living under police protection in Sweden, and his appearance to accept the award is the first time he has appeared in public since he attended a seminar on February 14 in Copenhagen that was attacked by a gunman sympathetic to Muslim objections to drawing Muhammad (see Opus 338). The presentation took place at a heavily secured event in the Danish parliament.

CENSOR FAILS — FOR NOW From a Comic Book Legal Defense Fund press releases: In response to that New Mexico parent’s complaint that the highly-regarded graphic novel Palomar by Gilbert Hernandez was “child porn” (see Opus 338), a district review committee has voted to keep the book in a high school library. CBLDF joined partners in the Kids Right to Read Project (KRRP) in sending a letter on March 9 to the Rio Rancho Public Schools to rebut this inaccurate and lurid storyline. KRRP pointed out that the book was not pornographic at all. The letter also argued that one parent’s objections cannot be allowed to determine the rights of other students to enjoy Palomar or any other literary work. And the letter urged the school district to adhere to its own guidelines, which state that reviews to challenged materials be treated “objectively, unemotionally, and as a routine matter.” The Rio Rancho review committee agreed. By a 5-3 vote, the committee voted on March 16 to retain the book. But the instigating parent, Catreena Lopez, was neither chastized nor silenced: she plans to appeal to the school board. This story broke in February with a heavily biased news report from Albuquerque-area tv station KOAT, which unquestioningly labeled the critically-acclaimed comic “sexual, graphic, and not suitable for children.” Lopez, the mother of a Rio Rancho High School freshman, said she wanted the book off school library shelves because it contained “child pornography pictures and child abuse pictures.” The KOAT report showed the library copy stuffed with sticky-note flags that Lopez had used to mark all the pages she found objectionable, but the reporter provocatively told viewers that “we can’t show you any of the images because they’re too sexual and very graphic.” In the latest news report from competing station KRQE, the book received slightly more balanced treatment: some images from interior pages were shown, albeit with pixelization, and a reporter interviewed CBLDF Executive Director Charles Brownstein to provide a counterpoint to Lopez. KRQE also referenced the letter that CBLDF and other members of the Kids’ Right to Read Project sent to the Rio Rancho school district in defense of the book, calling it an “exploration of culture, identity, sexuality and memory” rather than a compendium of child porn. Lopez seems undeterred, however, hyperbolically telling KRQE that “to me, this book is kind of like having a Hustler magazine in the schools.” While CBLDF strongly disagrees with that sentiment, “we are gratified that Rio Rancho district officials are following their challenge policy and requiring Lopez to lay out her case before the public. Rest assured we will keep fighting to make sure Palomar stays in the school library collection!” Makes us wonder how she knows about Hustler. The school board is expected to consider the appeal in a public meeting sometime in the coming weeks. RCH: Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

NOMINEES FOR NCS AWARDS NAMED The National Cartoonists Society has completed the nomination process for its annual Division Awards—cartooning endeavors in various modes, as indicated below—now dubbed “Silver Reubens.” The process this year involved members all voting for nominees via an online ballot box rather than distributing the nominating function to “jurying” by various of its chapters around the country. And, judging from the results unveiled below, this new process has produced a list of nominees that is more representative of cartooning in its assorted modes than before. In the Editorial Cartooning category, for instance, we have both liberal and conservative editoonists represented. And Comic Books and Graphic Novels reflect, for the first time in these categories, an actual knowledge about those enterprises and what’s going on in them. Alas, not all is golden: magazine Gag Cartooning seems restricted to New Yorker cartoonists. Nominees for the Granddaddy Award, the Reuben (no metallic adjective), we announced last time, in Opus 338: Roz Chast, whose graphic memoir about her parents’ last years, Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant, has resulted in a deluge of honors and recognitions (Kirkus Prize, National Book Critics Circle rcognition); Hilary Price (Rhymes With Orange comic strip) and Stephan Pastis (Pearls Before Swine comic strip). This is Pastis’ seventh nomination and Price’s second; for Chast, it’s the first. With two women cartoonists up, we might encounter a historic moment when this year’s Reuben is finally conferred. Only two women (Lynn Johnston, For Better or For Worse, and Cathy Guisewite, Cathy) have collected a Reuben statuette in the Society’s nearly 70-year history. The winners of the Reuben and the Silver Reubens will all be announced during the annual NCS Reuben Awards dinner on May 23rd. This year’s Reuben Awards will be held in Washington D.C. Herewith, a listing and a robust Rancid Raves Congrat to the nominees.

Editorial Cartoons Clay Bennett Michael Ramirez Jen Sorensen

Newspaper Illustration Anton Emdin Glen LeLievre Ed Murawinski

Feature Animation Paul Felix (production designer: “Big Hero 6”) Tomm Moore (Director: “Song of the Sea”) Isao Takahata (Director: “The Tale of Princess Kaguya”)

TV Animation Mark Ackland (Storyboards- “The Void” : “Wander Over Yonder) Patrick McHale (Creator “Over the Garden Wall”) Kyle Menke (storyboards- “Star Wars” parody episode “Phineas and Ferb”)

Newspaper Panels Dave Blazek (Loose Parts) Mark Parisi (Off the Mark) Hilary Price (Rhymes with Orange)

Gag Cartoons Liza Donnelly Benjamin Schwartz Edward Steed

Advertising/Product Illustration Kevin Kallaugher Ed Steckley Dave Whammond

Greeting Cards Gary McCoy Glenn McCoy Maria Scrivan

Comic Books Jason Latour (Southern Bastards) Babs Tarr (Batgirl) J.H. Williams III (The Sandman Overture)

Graphic Novel Jules Feiffer (Kill My Mother) Mike Maihak (Cleopatra in Space) Jillian Tamaki (This One Summer)

Magazine Illustration Ray Alma Anton Emdin Tom Richmond

Online – Long Form Vince Dorse (The Untold Tales of Bigfoot) Mike Norton (Battlepug) Minna Sundberg (Stand Still, Stay Silent)

Online – Short Form Danielle Corsetto (Girls with Slingshots) Jonathan Lemon (Rabbits Against Magic) Rich Powell (Wide Open)

Book Illustration Marla Frazee “The Farmer and the Clown” Yasmeen Ismail “Time for Bed, Fred” Shaun Tan “Rules of Summer”

Newspaper Comic Strips Brian Bassett (Red and Rover) Stephan Pastis (Pearls Before Swine) Glenn McCoy (The Duplex)

ODDS & ADDENDA ■ Abrams Books for Young Readers has announced the publication of the 10th volume in Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid series, which will be released on November 3, 2015. The title has not yet been divulged. ■ Paul D. Shinkman at USNews.com reported: The Pentagon dropped 60,000 propaganda cartoon leaflets over the key Syrian city of Raqqa on March 16. The gruesome cartoon depicts two extremist fighters at a “recruiting office” leading young people toward a blood-splattered meat grinder bearing the scrawled word “Daish” – an alternative name for the Cutthroat CalipHATE (Islamic State group) in the derogatory form U.S. allies in the Middle East prefer. ■ W.W. Norton’s Liveright and Co. imprint has acquired the rights to Jerusalem, the massive, long-awaited prose novel by acclaimed comics writer Alan Moore, author of such bestselling graphic novel classics as From Hell and Watchmen. Calvin Reid quoted a spokesperson for Liveright who said it’s “likely” the book will be published in fall 2016, but acknowledged that the date “is not firm.” Given Moore’s reputation for verbosity and layers of complexity, my guess is that the manuscript will require massive editing—which takes time. More than 20 years in the making, Reid said, Jerusalem is centered around Moore’s hometown of Northhampton, England, and tackles a dizzying array of subjects, including the nature of time and death. It also features a wild collection of historical figures, from Oliver Cromwell to James Joyce’s daughter to Buffalo Bill. Typical of the author of the Extraordinary Gentlemen graphic novels, in other words. ■ A Winnipeg Chapters bookstore was asked to pull the comic Tintin in America from its shelves, citing "the impact of racist images and perpetuating harmful narratives." At first, Chapters pulled the book, but, reported Kim Wheeler at CBC News, it is now back on the shelves after the bookstore chain determined it does not violate its policy. The cover image depicts stereotypical images of indigenous people in buckskin, and a chief brandishing an axe over his head while Tintin is tied to a post in the background. The manager said that the company doesn't feel there is anything wrong with the imagery or the content of the book. ■ From Dan Gearino at the Columbus Dispatch: For decades, a 1989 interview with Bill Watterson stood as the best, and close to the only, opportunity for readers to hear directly from the cartoonist about his life and art—until the publication last month of Exploring Calvin and Hobbes. The book — which follows the exhibit of the same title last year at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University — includes an in-depth interview with Watterson by Jenny Robb, curator of the Billy Ireland, as well as scans of Watterson’s original artwork. ■ Noted animator, game designer, and graphic novelist Doug TenNapel joined the faculty at Houston Baptist University’s Cinema & New Media Arts program in 2013 as filmmaker-in-residence. For nearly twenty years, TenNapel has been a creative force in popular media, beginning with his video game concept Earthworm Jim, which spawned an animated TV series and toy line in the early 1990s. At HBU, TenNapel created a reboot of the classic kids series VeggieTales for Netflix and DreamWorks Animation. The new series, “VeggieTales in the House,” premiered on Netflix this past winter and has just been nominated for an Emmy, HBU announced in a press release.

THE ABUSE OF SATIRE by GARRY TRUDEAU Originally entitled “Dangerous Lines: Cartoonists and Other Subversives,” Trudeau spotlighted comics and satire in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo massacre. Here is the entire text as we found it at theatlantic.com:

My career—I guess I can officially call it that now—was not my idea. When my editor, Jim Andrews, recruited me out during my junior year in college and gave me the job I still hold, it wasn’t clear to me what he was up to. Inexplicably, he didn’t seem concerned that I was short on the technical skills normally associated with creating a comic strip—it was my perspective he was interested in, my generational identity. He saw the sloppy draftsmanship as a kind of cartoon vérité, dispatches from the front, raw and subversive. Why were they so subversive? Well, mostly because I didn't know any better. My years in college had given me the completely false impression that there were no constraints, that it was safe for an artist to comment on volatile cultural and political issues in public. In college, there's no down side. In the real world, there is, but in the euphoria of being recognized for anything, you don't notice it at first. Indeed, one of the nicer things about youthful cluelessness is that it's so frequently confused with courage. In fact, it’s just flawed risk assessment. I have a friend who was the Army’s top psychiatrist, and she once told me that they had a technical term in the Army for the prefrontal cortex, where judgment and social control are located. She said, “We call them sergeants.” In the print world, we call them editors. And I had one, and he was gifted, but the early going was rocky. The strip was forever being banned. And more often than not, word would come back that it was not the editor but the stuffy, out of touch owner/publisher who was hostile to the feature. For a while, I thought we had an insurmountable generational problem, but one night after losing three papers, my boss, John McMeel, took me out for a steak and explained his strategy. The 34-year-old syndicate head looked at his 22-year-old discovery over the rim of his martini glass, smiled, and said, “Don’t worry. Sooner or later, these guys die.” Well, damned if he wasn’t right. A year later, the beloved patriarch of those three papers passed on, leaving them to his intemperate son, whose first official act, naturally, was to restore Doonesbury. And in the years that followed, a happy pattern emerged: All across the country, publishers who had vowed that Doonesbury would appear in their papers over their dead bodies were getting their wish. So McMeel was clearly on to something—a brilliant actuarial marketing strategy, but it didn’t completely solve the problem. I’ve been shuttled in and out of papers my whole career, most recently when I wrote about Texas’s mandatory transvaginal probes, apparently not a comics page staple. I lost 70 papers for the week, so obviously my judgment about red lines hasn’t gotten any more astute. I, and most of my colleagues, have spent a lot of time discussing red lines since the tragedy in Paris. As you know, the Muhammad cartoon controversy began eight years ago in Denmark, as a protest against “self-censorship,” one editor’s call to arms against what she felt was a suffocating political correctness. The idea behind the original drawings was not to entertain or to enlighten or to challenge authority—her charge to the cartoonists was specifically to provoke, and in that they were exceedingly successful. Not only was one cartoonist gunned down, but riots erupted around the world, resulting in the deaths of scores. No one could say toward what positive social end, yet free speech absolutists were unchastened. Using judgment and common sense in expressing oneself were denounced as antithetical to freedom of speech. And now we are adrift in an even wider sea of pain. Ironically, Charlie Hebdo, which always maintained it was attacking Islamic fanatics, not the general population, has succeeded in provoking many Muslims throughout France to make common cause with its most violent outliers. This is a bitter harvest. Traditionally, satire has comforted the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable. Satire punches up, against authority of all kinds, the little guy against the powerful. Great French satirists like Molière and Daumier always punched up, holding up the self-satisfied and hypocritical to ridicule. Ridiculing the non-privileged is almost never funny—it’s just mean. By punching downward, by attacking a powerless, disenfranchised minority with crude, vulgar drawings closer to graffiti than cartoons, Charlie wandered into the realm of hate speech, which in France is only illegal if it directly incites violence. Well, voila—the 7 million copies that were published following the killings did exactly that, triggering violent protests across the Muslim world, including one in Niger, in which ten people died. Meanwhile, the French government kept busy rounding up and arresting over 100 Muslims who had foolishly used their freedom of speech to express their support of the attacks. The White House took a lot of hits for not sending a high-level representative to the pro-Charlie solidarity march, but that oversight is now starting to look smart. The French tradition of free expression is too full of contradictions to fully embrace. Even Charlie Hebdo once fired a writer for not retracting an anti-Semitic column. Apparently he crossed some red line that was in place for one minority but not another. What free speech absolutists have failed to acknowledge is that because one has the right to offend a group does not mean that one must. Or that that group gives up the right to be outraged. They’re allowed to feel pain. Freedom should always be discussed within the context of responsibility. At some point free expression absolutism becomes childish and unserious. It becomes its own kind of fanaticism. I’m aware that I make these observations from a special position, one of safety. In America, no one goes into cartooning for the adrenaline. As Jon Stewart said in the aftermath of the killings, comedy in a free society shouldn’t take courage. Writing satire is a privilege I’ve never taken lightly. And I’m still trying to get it right. Doonesbury remains a work in progress, an imperfect chronicle of human imperfection. It is work, though, that only exists because of the remarkable license that commentators enjoy in this country. That license has been stretched beyond recognition in the digital age. It’s not easy figuring out where the red line is for satire anymore. But it’s always worth asking this question: Is anyone, anyone at all, laughing? If not, maybe you crossed it.

Reactions At breitbart.com, a conservative website, John Nolte was quick to accuse Trudeau of “victim blaming.” Said Nolte: “What Trudeau fails or chooses not to understand is that rebellion is not hate speech. Charlie Hebdo was not gratuitously mocking Muhammed or Jesus Christ or the Pope. For the cause of free speech, Charlie Hebdo was pushing back against what it rightly saw as creeping fascism, especially Islamic fascism, in the most blatant and in-your-face way possible. “As a devout Catholic, I take no pleasure in seeing my faith debased. Context matters, though, and while I may have winced at times, I understood and appreciated Charlie Hebdo’s intentions. That’s what makes Trudeau’s comments so sinister. To accuse Charlie Hebdo of Hate Speech is to attack their intentions. It is obvious this far-left outlet was furthering the righteous cause of free speech. ... “It is also obvious that Charlie Hebdo was fighting for this cause in a way Trudeau never would: bravely, and in the face of legitimate threats. There’s a saying that if you scratch a liberal, underneath you will reveal a fascist. With Trudeau, you will also find a coward, a hack decades past his prime, surviving on the affirmative action of the same left-wing mainstream media editorial pages he would never challenge or provoke, for fear it might ding his vast fortune.” Denis Kitchen, founder of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, was interviewed on the eve of the East Coast Comicon, April 11-12. Kitchen had not heard about Trudeau’s speech at the time of the interview (I assume), but he made remarks about Charlie Hebdo that seem to dovetail with Trudeau’s, After observing that “the world has changed since you founded the CBLDF,” interviewer Mark Voger asked: “Where is the line between fighting for freedom of speech on one hand, and avoiding incidents such as the rioting following the Danish cartoons that portrayed Mohammed, or the killings at the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris?” Said Kitchen: “Here's the thing: If you're going to be a satirist, you must be honest. Internal integrity is central to being a satirist. But it's a fine line between what is brave and what is stupid. If you draw anything that depicts Muhammed, you are crossing a major line there. You can't even do a benevolent cartoon of Muhammed if you're a Muslim; you can't even draw the image. That puts you in dangerous territory. The Danish cartoons crossed that line; Charlie Hebdo crossed that line. You're poking a stick in that eye, and we've seen the consequences.” Alan Gardner, in posting excerpts from the speech, added his own reaction; herewith—: “The issue (free speech and when it’s employed) is not as clear cut to me. I certainly get his point and I think it’s well articulated and reasoned. I disagree that Charlie Hebdo was ‘punching downward.’ The cartoons featured in the magazine were not making fun of the common Muslim practitioner – punching downward as defined by Garry. The cartoons made fun of the founder of the religion – a religion which subjugates its adherents into a world view that is oppressive toward women, other religions and cultures and condones violence as an acceptable way of dealing with others. That IS punching upward.” I agree. Charlie Hebdo was punching upward. But it wasn’t Muhammad that was being punched. It was oppressive authority. Muhammad served merely as a symbol of one kind of abuse of power. And Charlie attacked others of the same ilk—the Catholic church among them. Adherents of Islam and Catholicism were understandably offended. But perhaps their zealous devotion to their religion blinded them to its essentially oppressive nature. One of the ways we attack oppression and abusive power is to laugh at it—to laugh it out of existence. And I believe that’s what Charlie was doing. In the case of Charlie’s satirical assaults, those who were laughing were not, admittedly, devotees of the religions being attacked; those who were laughing were those who could see that those passionate devotees were being bamboozled and persuaded to act in ways that diminish or limit human potential. The problem that Trudeau addresses here is that when satirizing an institution, like a religion (or a form of government), the satirist unavoidably seems to be attacking the institution, not just those who abuse the power that the institution confers upon them—the real targets of the satire, in other words. I admire Trudeau for being sensitive to this aspect of satire. It is a problem that perhaps only a career satirist like Trudeau is much aware of. But good satire always risks crossing the line into hate speech. To be too wary of the danger of this pitfall is to curb the satiric impulse altogether. And I doubt that Trudeau would endorse that outcome.

HOW COMICS JOURNALISM IS DIFFERENT. OR NOT Josh Neufeld is a New York Times best selling author praised for his character driven narratives reporting on the aftermath of hurricane Katrina, the revolution in Bahrain, or racial profiling on the Canadian US-Border. What sets him apart, says Caroline Bins at verhalendejournalistiek.nl, is that he reports factually in graphic novel form. Bins interviewed Neufeld in March; his responses appear herewith—: Despite the celebrated work of nonfiction cartoonists like Joe Sacco, Art Spiegelman, Marjane Satrapi, Scott McCloud, and Alison Bechdel, many people still confuse the medium of comics with the content of comics. They assume that all comics are fiction, fantasy, or humor for children. So the most common misconception about comics journalism is that it’s not real journalism. But in my work I follow the traditional rules of journalism regarding sourcing, quotes, chronology, and so on. It’s real. It happened. All the quotes people are saying are actual quotes that they said. The comics form is a hurdle for some people It’s true that in the course of telling nonfiction stories — especially when you’re doing long-form, and crafting extended “scenes” — the cartoonist is required to “make up” certain details of things (people’s outfits, details of buildings or rooms, miscellaneous passers-by, etc.) that he or she didn’t personally witness or have visual records of. But I believe most readers understand and accept these conventions. What they get in return are powerful, visceral stories that drop the reader right into the action. I believe this gives readers an understanding of people and events that can be deeper and more intimate than other forms of journalism. Different forms of journalism require different “participation” on the part of their consumers, and they often speak in different voices: formal or informal, fact-focused or emotion-focused. To me, what’s really exciting about comics journalism is the form’s ability to bring more visceral emotion and intimacy into a story while still being truthful. As the institutions of traditional journalism appear to be fraying — crumbling, even — the growing acceptance of newer vehicles like comics journalism, participatory journalism, multimedia journalism are all giving notice to the traditional forms that they may need to reinvent themselves a little for the changing media landscape.

THEY SHOOT BLACK PEOPLE, DON’T THEY? That’s the title of the slide show Keith Knight has been showing around the country. The title is another in Knight’s long list of ironic endeavors. He once posted signs around his neighborhood in San Francisco that read: Rent a Black (and listed his phone number). It was his satiric response to a growing cultural trend that made it fashionable to have African Americans in attendance when giving a party. Knight creates three syndicated comics features: The Knight Life, a 7-day-a-week comic strip; The K Chronicles, a occasional multi-panel cartoon; and (th)INK, a single-panel “political cartoon.” Knight was recently named a 2015 NAACP History Maker for his cartoons about police brutality, and Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs talked to him about his long history of drawing insightful cartoons about police brutality in America since the ’90s, when it was a video of the Rodney King beating that put LAPD officers in the stark national spotlight. “And through the years,” Cavna said, “from Missouri to New York to Ohio to South Carolina, the names of victims and officers changed, but not the brutality.” Said Knight: “It’s weird to see things that I’ve drawn as comics years before come true. Like, a strip I did in 2008, where the targets police were shooting at were young black men. It’s no doubt frustrating, but the public response has changed recently because of social media. All these incidents of police brutality can no longer be hidden or swept under the rug. We are now seeing it as it happens, and how often it happens. At this point, one has to truly double-down on their complete denial of how huge this problem is, or they have to acknowledge it, and work towards change.” Knight did a ride-along in a police car recently. Cavna asked him whether it was eye-opening in ways that surprised him—or did it essentially affirm his own sense of the world. “It mostly affirmed my sense of the world,” Knight said, “ — cruising around the worst parts of town and monitoring poor people. One of the cops seemed extremely distrustful of me being present while they did their ‘jobs.’ … And we drove waaayyy too fast down small, residential streets. Looking back, I think police officers should always have volunteer citizen baby-sitters riding around with them. I think they’d behave a lot better.” He added: “I will say that I’ve heard from a retired cop that, with marijuana finally being legalized all across the country, they regret putting away — and basically destroying — the lives of so many young black men for simple pot possession.” About his History Maker award, Knight said: “I was shockingly surprised, humbled and honored. It means a ton, considering the amazingly brave people on the protest front who were recognized along with me. I’m just a dude with a pen. What makes this honor special is that it reaches beyond the comics industry. Not to diminish my previous awards, but telling my parents I got recognized by the NAACP has a whole other thing to it. Makes me wish that some of my recently passed elders were around to hear about it.” Noting

that Knight is the father in a growing family, Cavna asked him when he would “Ahhh,” said Knight. “That’s the big question amongst parents of color. ... I think it’s a long, drawn-out conversation that you return to time and time again. Much like my comics!” Cavna ended with this note: If you want Knight’s slide show to come to your town, you may email him at: keef@kchronicles.com And here are some of the pictures he’ll show you.

COVER CONTROVERSY!!

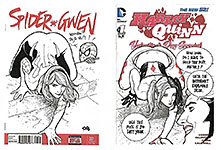

AND THEN FRANK CHO, master limner of the feminine form, drew a parody image of the notorious Milo Manara Spider-Woman cover (see Opus 329) for his blog on the new character, Spider-Gwen. Jude Terror at theouthousers.com noted immediately that The Mary Sue's Sam Maggs took issue with the cover. Acknowledging that Cho “has always drawn some cheesecake stuff,” Maggs says this particular rendering, evoking another cover that caused so much discomfort among lots of comic book readers, shows a clear disregard for the perfectly valid outrage over Manara's original Spider-Woman variant; an incident that, we should note, made our list of the ‘Worst Moments in Female Fandom in 2014.’ “Aside from being an obvious poke at ‘those angry feminists’ who ‘overreact’ to things, the cover is also an unfortunate but elucidating look at what some men think about women who are trying to carve out a space for themselves in the frequently misogynist world of comics – where they feel objectified and overly-sexualized on a regular basis. What makes this sketch even more inappropriate is that the Spider-Gwen book is clearly aimed at a teen audience, meant to entice new, younger female readers to Marvel comics. Plus, Gwen herself is a teenager.” In response, Cho doubled down and posted the following on his blog—: “Wow. What a crazy couple of days it has been. My parody cover sketch of Spider-Gwen aping the infamous Manara Spider-Woman pose sent some of the hypersensitive people in a tizzy. “To be honest, I was amused and surprised by the uproar since it was, in my opinion, over nothing. It's essentially a small group of angry and humorless people ranting against my drawing of a pretty woman. It's utter nonsense. This world would be a better and a happier place if some people just grow a sense of humor and relax. “Now,

I'm getting bombarded by various bloggers asking for an interview addressing The “origional” Cho-Manara “cover” appears on the left in the accompanying visual aid; Cho’s witty response, on the right.

AND THEN we

have a couple of antiques—a Dennis the Menace cover and a Betty and

Veronica cover. A friend and fellow funnybook lover showed me these. And it

seemed to both of us preposterous that these two specimens found their way into

print. As

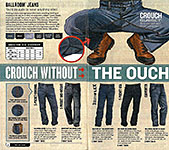

for the Dennis cover—well, maybe “Boner” is a Finally, by way of ending this segment on yet another laughable expression in print—although not in comics—here’s a spread from a catalog advertising “ballroom jeans.” I suppose you don’t have to read the fine print to get the gag. But it helps.

APPEASING THE “VOCAL MINORITY” In early March, Erik Larsen, one of the founders of Image Comics and the long-term artist-writer of Savage Dragon (a favorite of mine, I should say, by way of admitting a bias), tweeted that he was “tired of the Big Two placating a vocal minority at the expense of the rest of the paying audience by making more practical women outfits.” His remarks prompted some incensed responses in the Twitterverse, many by women comics creators who, presumably, took offense at what they thought was Larsen’s advocacy of skimpy costumes for women. Chris Bechtloff at reaxxion.com gave Larsen a chance to clarify, and I’m pulling out of that the following (all Larsen unless italicized)—: First, by “vocal minority” I don’t mean any group other than the collective group of all people talking. Anybody with a voice who talks online or sends emails, anybody who gives feedback of any kind, and that includes me. The largest segment of our audience is silent. They say nothing at all. They likely talk amongst friends and family like anybody else, but they’re not inclined to go online and share their opinions with the masses. There’s a tendency to treat any feedback as though it represents a measurable portion of the audience. If a book gets one letter for every thousand readers, editorial sometimes assumes that each letter talks for the other 999 people, but that’s nonsense. If one guy says he’d totally buy a signed and numbered hardcover 3-D Man collection, it may very well be that just that one reader is interested in such a book. There’s no reason to think the other 999 unspoken readers would fall in line and purchase such an unlikely collection. It’s no way to run a company. That single voice really doesn’t speak for the others. That one reader speaks for that one reader. Others may agree. Others may not but they aren’t making their opinions known. There’s also a tendency [on social media] to bellyache. Readers don’t necessarily run out and sing the praises of anything: they’re more likely to bitch and moan, especially on the Internet with a screen-name that isn’t their actual name. The call for realism seems to be the fallout from the movies. In the movies, it’s nearly impossible to create costumes that fit as well and look as good as those in the comics. That’s an advantage artists have when putting lines on paper: they can have clothes be perfectly form-fitting and we can see every muscle and sinew, even through cloth. This means that an artist can draw a far prettier picture than could possibly appear on film. The disadvantage is, of course, that if lines are added to costumes [to delineate the “practical” modifications], then an artist needs to draw those lines again and again, whereas in the movies that’s not a big deal. Since movies are incapable of making superhero outfits that fit and look as good as the ones in the comic books, they have to make alterations in order to make up for that. Theirs is a compromise. Our mistake is following their lead as though it is a lead instead of a compromise. [RCH here: I agree with Larsen. The movie costumes of comic book superheroes are sorry substitutes for the funnybook versions—but they are practical from a costuming and appearance perspective. The problem, as Larsen points out, is that now the comic book characters are expected to look—to be costumed—like their on-screen incarnations. Not a good choice. Back to Larsen:] This started out as comics emulating movies, but it’s expanded. And for a large part the argument is that it “makes costumes more realistic.” When Batman is on screen he wears armor, so Batman in the comics has to wear armor now, and then Superman has to and Wonder Woman and it just gets silly. The audience expects this and justifies it, arguing that, “of course Batman would wear armor!” But the reality is this: armor is ridiculous, not realistic! One of the reasons superheroes wore tights in the first place is because acrobats wore tights, and why did acrobats wear tights? So they could move! Modern actors have admitted that they can hardly move in the Batman suits. In some cases the actors couldn’t even turn their heads: they had to move their entire bodies in order to look from side to side. One famously admitted that anybody could beat the crap out of him in that suit! ...

READERS HAVE OFTEN BEEN PRICKLY when it comes to bodies, especially those of women. What doesn’t seem to be understood is that there’s a big difference between costume design and character design. Wonder Woman’s costume is perfectly fine. It’s strong, it’s iconic, it harkens back to ancient Greece with athletes in appropriate sporting attire. It’s a costume that functions. But it’s also one which can be abused. Women characters can be drawn sexy or strong, girlish or mature, thin or voluptuous and everything in between. If DC doesn’t want Wonder Woman to pose seductively and prance around like a sex object, they should make that point clear. Frank Miller drew Elektra as a powerful, taut ball of muscle. Wonder Woman can be that: she doesn’t need to be a tart. But that’s the way she’s drawn, not costume design. I’ve attached two images that I’ve joined together showing Wonder Woman drawn by artists Mark Beachum and Bruce Timm. Both draw the same Wonder Woman costume, but one looks weak, vulnerable and slutty as all hell and one looks proud, confident and powerful. So is it the costume to blame or the approach to drawing the character? I say the problem is the approach. DC and Marvel seem to act as though the problem is the costume design. ... The danger is, of course, that the online community feels that they are empowered. We already saw a Milo Manara Spider-Woman cover censored due (I would think) to online pressure and since that time Spider-Woman’s costume was altered as well. Where will this lead? Well, if history is any indication it can lead to something like the Comics Code Authority in the ’50s where a group of outraged individuals policed everything we read. I’m not convinced that’s such a great idea. ... The slippery slope is a return to the Comics Code. That, or some other kind of censoring body who knows better than the rest of us. Movies have gone in a direction where everything is pre-screened to an audience who weighs in on them and decides what’s good or bad and changes are made accordingly. The danger of taking cues from the audience is pablum like Star Wars Episode I where fans weighed in on what they wanted, George Lucas gave them what he thought they wanted and then they hated what he gave them. The audience is not wiser than the creative people. If they were better writers and artists than those in the field, they would be employed in the field. They’re mouthy amateurs and their suggestions should largely be treated like the witless ramblings of an insane person. ... The danger is in thinking that the vocal few represent the entirety of your audience. They don’t. And so what we’re getting is situations like Jim Lee giving Wonder Woman pants in the Justice League because readers demanded it, then getting rid of them because other readers demanded it, all before the pants version saw print! These publishers are running around like chickens with their heads cut off, trying to please everybody and not knowing who to listen to, and I can’t help but feel that a lot of the people yelling and screaming aren’t buying the comics, pants or no pants. ... The bottom line is that you can’t please everybody and everybody’s voice is not being heard. So your best bet is to do the best work you can, try to expand the market and try new things and do more of the things that work and less of the things that don’t work. As for his own books, Larsen is pragmatism incarnate: I’m in charge here. Readers can buy what I’m selling or not. Ideally that’s what it should be. A candy bar company makes a candy bar and you can buy it or not. Those are your two choices. The internet assumes there are two other options: that candy bars can be pulled off the shelves and returned to their manufacturers unsold or that those buying candy bars can stipulate the ingredients. You want to make a different comic book? Make one of your own. You can buy the one I produce or you can not buy it, but you can’t dictate what goes on inside those pages. One guy makes that call.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Quotes and Mots “You may not be able to change the world, but at least you can embarrass the guilty.”—Jessica Mitford “When evaluating my effectiveness, don’t compare me to the Almighty. Compare me to the alternative.”—Joe Biden “Story and art are the humanizing elements of us.”—Emma Thompson

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy Postponed until next time. Sob.

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE Here’s an Irish prayer that Gregory Peck recited once for Lauren Bacall: Dear Lord, I want to thank you, Lord, for being with me so far this day. I haven’t been impatient, lost my temper, been grumpy judgmental, or envious of anyone. But I will be getting out of bed in a minute and I think I will Really need your help then. Amen

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

FOR ALL US

POTTY-MOUTH WATCHERS, the year 2015 is turning out to be a real pisser. Jeremy

got us off to a “good” start in Zits. Jerry Scott and Jim

Borgman produced a three-day sequence that began when their starring

teenager arrives in class to take a test only to discover that he needs to

answer a call of nature. As I’ve mentioned on other occasions, I think the word “pee” is the word of choice for urination among women; for men, “piss” is the word of choice. But that is beside the point of our current sermon. Here, we wish only to recognize, as we have numerous times in the past, that “times they are a-changin’”: used to be, newspaper comic strips couldn’t even THINK the word “pee” (and I suspect “piss” is still verboten). And now we have Jeremy saying it out loud. Well, actually, he is thinking it. But “thinking” and “speaking,” although differentiated by the way a speech balloon is drawn (with or without “thought” bubbles), the effect is the same: visual “speech,” the same as if he’d spoken his thought aloud. That was in January. In March (at the bottom of this visual aid), we got another dose of peeing, this time with a picture of Jeremy at the urinal. Never would that have been depicted in the distant days of yore in newspaper funnies. And

during the very same week, just a few strips down the funnies page in my

newspaper, we have a four-day sequence in Brian Crane’s Pickles in which gramma Opal Which brings me to that classic admonition always foisted off on newlywed men: be sure to close the lid in consideration of your wife’s alimentary needs. And so equality between the sexes evaporates at a single swell foop. Why aren’t new wives ever cautioned to leave the lid up in consideration of their husbands?

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. THIS STARTED, I assume, as an offshoot or parody of the nefarious “Where’s Waldo” posters and wall scrawls. Instead, we have—:

Where’s the Dildo By Jenny Block at Huffington Post Um, so this is happening. A Tumblr has been created in which a dildo is poised in every photo and viewers are invited to do their best to find it. "An installation art project about the place of rubber in our lives," the heading reads on the collection titled "Subtle Dildo." I like this. And I will tell you why. It puts the dildo in its rightful place. Front and center. Well, sort of. I mean, it's hiding. But it's asking to be found and—like a car wreck— it's impossible to look away. Dildos are our friends. Certainly a friend to the lesbian. But no reason it shouldn't be a friend to gay men and straight men and women and every other self-respecting adult. This cute little project makes these oft whispered about toys a little less daunting. It's hard not to laugh and imagine the little guy holding its breath thinking, "She's never going to find me! Ah! Look at her looking over there when I'm over here." Just makes me giggle. I also like this project because it treats the penis—or an object often intended to stand in for a penis— as it should be treated, respectfully but not without humor. With Mark Driscoll being "your penis in on loan from God," a little levity about the mighty member seems in order. Once we start seeing our parts as instruments of pleasure instead of "those parts of which we shall not speak," we can really start enjoying them and using them properly. Sure, the human body is beautiful. But let's not kid ourselves, our naughty bits are some crazy looking parts. It's time we got comfortable with them and stopped treating the whole sex thing with so much fear. It's sex for goodness sake. I also like this project because it has an arty aspect a la Duchamp that the Art History buff in me is just delighting in. Art is about creating a reaction. It's about making a statement. It's about challenging the viewer to really look at it and question what she may or may not be seeing. Subtle Dildo certainly does all of those things. That's the other reason I like this project. The name. Subtle Dildo. Ain't nothing subtle about a rubber cock. No siree, Bob. And as any lesbian—or anyone else who uses one for that matter—will tell you, you know when that little devil is in the room. Believe me, you know. So the idea that there is any subtlety to a dildo is a kind of charming and I kind of like it. I also like this project because it clearly does not take itself seriously. As it shouldn't. As men with them shouldn't. As women without them shouldn't. As anyone shouldn't. What I like the most about this project is that it's a subtle reminder—far more subtle than any dildo I ever met—that we are all far more than the sum of our parts and what we do with those parts and whom we do those things with and how we identify regardless of what parts we were born with. Subtle Dildo, the personification to my mind of the penis, is a gloriously disembodied reminder that who you love and how you love them, who you f**k and how you f**k them makes no difference. Never. Ever. Ever. Now, where is that dildo...

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews THE RANCID RAVES Book Grotto is littered, literally, with books we acquired with the intention of reviewing them. Alas, they’ve piled up over the years, and it has become increasingly apparent that we’ll never give them the kind of intensive examination they deserve. So rather than let the accretion be entirely in vain, we’ve started this new department wherein we’ll briefly describe books by way of urging them upon you. And the first of these, in order and in importance, is surely—:

Jack Davis: Drawing American Pop Culture, A Career Retrospective By Jack Davis; Introduction by William Stout; Biography by Gary Groth 207 10x13-inch pages, color; 2012 Fantagraphics hardcover, $49.99 THIS SCRAPBOOK

of Davis art is organized in chapters whose themes are laid out by Stout—Early

Years, Comic Book Years, Advertising Years, Record Jacket Covers, Magazine

Illustration—with a few insightful notes about style and methods of work. At

the end is Groth’s 12-page biography followed by 5 pages of paragraph-long

“tributes” by such Davis admirers as Sergio Aragones, Peter Bagge, Drew

Friedman, Bill Griffith, Al Jaffee (“The best part about Jack is that he is

a throwback to a kinder, gentler time. He is a quintessential Southern

gentleman.”), Joe Kubert and others. In between are pages of gorgeous

Jack Davis art, much of it in color. The Early Years (high school, college,

Navy) are mercifully represented by only a few pages of work. The comic book

period is almost all from Mad, horror and war scarcely evident. Some of

his unsuccessful comic strip attempts are here (Beauregard, the only one

to achieve publication—four months merely—is criminally shortchanged by

printing 12 strips postage-stamp size on one page), but when we get to Record

Covers and Movie Posters, the book blossoms in color. The final section

reproduces Time and TV Guide covers (alas, many small, nine to a

page but with caricatures and related illustrations, including some preliminary

sketches, at full-page dimension). The book’s only conspicuous flaw: no source information is given on any of the pages. To learn that pages 48-49 reproduce panels from a 1960 comic strip based on the “Howdy Doody” tv show, you need to consult two pages of End Notes. This is not an impossible task: you can browse the book with a finger at the End Notes section and easily flip back and forth. But some pages are not annotated at all. Otherwise, the book is a treasure trove of Jack Davis’ most mature work.

The Cisco Kid: Vol. 1, 1951-1953 By Jose Luis Salinas; Introductions by Sergio Aragones and Dennis K. Wilcutt 230 8.5x11-inch landscape pages, b/w; 2011 Classsic Comics Press paperback, $24.95 PUBLISHER

CHARLES PELTO, who has brought us high quality reprints of such illustrative

masterworks as Mary Perkins On Stage and The Heart of Juliet Jones, herewith recycles one of the greatest artworks in newspaper comic strip

history. Based upon a name in a O.Henry short story (published in this volume’s

introductory material, in which the Cisco Kid is a murdering outlaw, scarcely

the light-hearted Robin Hood of the Old West who appears in the strip), the

strip, a rollicking and oft nicely harrowing albeit melodramatic narrative, was

written by Rod Reed and gloriously drawn by Salinas. Unhappily, Salinas’

copiously feathered and

Wally Wood: Classic Tales of Torrid Romance By Wally Wood; Introduction by J. David Spurlock 200 8.5x11-inch pages, color; 2014 Vanguard paperback, $24.95 “TORRID” WHEN

COUPLED TO “WALLY WOOD” creates an expectation for lascivious pictures of

Wood’s amply curved women, an expectation this book promptly disappoints. The

“romance” stories reprinted herein start with September 1949 and end with April

1953 (all copiously dated and sourced), during what must, in retrospect, be

regarded as Wood’s less inciting apprenticeship. Reproduction from comic book

pages is excellent, but the typical Wood femme doesn’t appear until the last

three-four stories, and even then, his hand is more evident in faces, not

figures.

Wally Wood: Strange Worlds of Science Fiction By Wally Wood; Introduction by J. David Spurlock 216 8.5x11-inch pages, color; 2012 Vanguard paperback, $24.95 THIS VOLUME

EMBRACES Wood work from 1950 through 1958, with most from 1951 (15 of the 23

stories). Herein, the artwork is typical of Wood’s mature style—feathering and

shading—and the women are Wood women.

Cannon By Wallace Wood; Introduction by Howard Chaykin 288 7x11-inch landscape pages, b/w plus a few color pages; 2014 Fantagraphics hardcover, $35 THE OVERSEAS WEEKLY was a tabloid published 1970-73 for distribution to U.S. military stationed abroad, and for it, Wood produced Cannon, which appeared as a full-page comic strip about an operative, John Cannon, who had been brainwashed and re-programmed to be a perfect, emotionless assassin. Most of Cannon’s assignments, however, involve rescuing barenekidwimmin, who appear in profusion with every installment of the continuing story—most regularly, the sinister and voluptuous Asian, Madame Toy.

Although penciled by someone else, Wood’s inks, as Chaykin says, made the artwork “his property, his line and impact being so strong,” and as a result, we have here the mature Wood at the top of his game. The Cannon strips are printed two to a page in stunning clarity. Cannon also appeared twice (1969 and 1976, before and after his Overseas incarnation) in comic book form from the same publisher, Heroes, Inc.; and this volume concludes with both adventures, the first, in color, but the pages are severely reduced and appear here two to a page, the women, although luscious, always clothed. Also in this volume, reproduction of a letter from Wood to the publisher, outlining plans for a future project, a comic book of “sex, violence and horror—none of it would pass the Comics Code”—for a wide audience, “science fiction fans, comic book fans, servicemen, grownups and just horny kids.” I’m hopeful that Fantagraphics has plans for publishing a companion volume of Sally Forth, Wood’s comedic naked lady strip for Overseas Weekly. This is the second “complete” reprinting of Wood’s Cannon: Fantagraphics did it (almost) in 2001 at a larger, tabloid size (10.5x13 inches). The earlier version is missing the first strip, but it includes an appreciative 4-page introduction by Jeff Gelb, who places Cannon in the just-concluding super-spy context of the times—James Bond, the Avengers, et al—but neglects to cite many dates; so as history, it falls somewhat shy. The volume is missing the Heroes, Inc. material, and the reproduction, while excellent, is just a tiny shade less pristine than the new production.

The Art of Ramona Fradon By Ramona Fradon; Introduction by Walt Simonson; Interview with Howard Chaykin 152 9x12-inch pages, color; 2013 Dynamite hardcover, $29.99 FRADON ENTERED the comic book industry in the early 1950s, left to raise her daughter in the 1960s, and returned in the 1970s and left again in the 1980s to draw the syndicated newspaper comic strip, Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr, which she continued until 1995. Fradon, who was married for 35 years to New Yorker cartoonist Dana Fradon (until divorcing him in 1982), was one of the few women working significantly in comics. This volume presents samples of all her work from Aquaman and Metamorpho to House of Secrets and Freedom Fighters to Super Friends and Plastic Man (I always told her she did the best Plastic Man since Jack Cole, and she always agreed) for DC and Fantastic Four (one issue) for Marvel to Brenda. Threading throughout the artwork on display is Chaykin’s knowledgeable and perceptive interview with Fradon, covering every aspect of her career from an artist’s perspective. The book concludes with a bibliography of her work (helpful, but, I suspect, not complete: I don’t see listed the Shining Knight story, which she says is her first for DC).

Berlin, City of Stones: Book One By Jason Lutes 212 7.5x10-inch pages, b/w; 2001/2011 Drawn & Quarterly paperback, $22.95 Berlin, City of Smoke: Book Two By Jason Lutes 212 7.5x10[ilnch pages, b/w; 2008/2011 Drawn & Quarterly paperback, $22.95 THESE TWO GRAPHIC NOVELS were originally published in comic book format, then re-issued in book form. The action takes place in post-WWI Germany between September 1928 and August 1930, when the liberal democracy of the Weimar Republic lapsed. At the end of the “golden years” of the 1920s, Germany was beset by political unrest, extremists on both the left and the right, the emergence of the communists and the Nazis; economically, the country was suffering from massive inflation. In this setting, Lutes tells the stories of several individuals from different parts of the Weimar social order, chiefly that of a young woman, Marthe Muller, who comes to Berlin for the first time, and Kurt Severing, a political writer. Marthe becomes Kurt’s mistress for a time, then leaves him for a Lesbian relationship. As the institutions of democracy slip away, Kurt becomes disillusioned about the efficacy of political writing to affect the course of events. Book Two ends with his burning his papers and watching them go up in smoke. The other characters Lutes deploys are victimized by the social and political turmoil of the period. In the first volume, one of them, a mother, dies during a riot in which the chief weapons are stones hurled by the opposing sides. Throughout

the books, the tone is bleak and unforgiving. The characters all seem

helplessly caught by the circumstances of their lives. As a reflection of the

history of the times, Lutes’ narrative is probably as authentic as possible. At

the time of this work’s first