|

||||

Opus 306 (March 8, 2013). At long last, what many cogent readers have long maintained, Fredric Wertham sabotaged the comic book industry with fraudulent science. Ding Dong—the Witch Is Dead! In other news, Herblock Prize goes to Dan Perkins (aka Tom Tomorrow) and another editoonist is fired to save money. Plus a few other scraps of news and a couple announcements. It’s been a month since our last posting, we admit. But at the end of January, we posted a novella-length Hindsight on the Al Capp-Ham Fisher feud, ample reading matter for the ensuing month, we hoped, while we finished up our latest book, which is announced herein, at the end. But now we’re back, and here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Kurtzman Exhibit Herblock Prize to Dan Perkins (aka Tom Tomorrow) Oscar Dimmed by Family Guy Another Editoonist Casualty Will Eisner Week

Ding Dong—The Witch Is Dead WERTHAM PROVED A FRAUD

Newspaper Comics Page Vigil

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE The End of Black Kiss 2 Cover Sex

GRAPHIC NOVEL Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Kurtzman On Display “The Art of Harvey Kurtzman” will be on display at the Museum of American Illustration at the Society of Illustrators clubhouse in midtown Manhattan, opening on March 6 and continuing through May 11, 2013. The diverse exhibition will showcase over 120 works in the museum’s two-floor gallery. As the creator of Mad, Harvey Kurtzman may be the most influential American cartoonist since Walt Disney: Disney’s vision of America as a small town brimming with good neighbors and obedient children was sharply contradicted by Kurtzman’s satiric portrait of an urban society swarming with grasping politicians and greedy promoters and sexist bosses. Both visions persist but not simultaneously. The nation’s youth outgrow Disney as soon as they are old enough to begin reading Mad, which infects them with a certain cynicism about the icons of American culture as well as the functioning of its institutions. Most of the underground cartoonists of the late 1960s were inspired by Mad. More about the exhibition from the website of the National Cartoonists Society: Co-curators Monte Beauchamp (founder, editor, and designer of the comic art/illustration anthologies Blab! and Blab World), and publisher/cartoonist Denis Kitchen (co-author of “The Art of Harvey Kurtzman” and representative of the estate) have assembled the most comprehensive assemblage of Kurtzman art to date, culled from select private and family collections. Highlights include: Kurtzman life drawings from 1941; rarely-seen late 1940s strips done for the New York Herald-Tribune as well as for Marvel’s Stan Lee; key covers, strips and full stories Kurtzman created for Mad, Frontline Combat, Two-Fisted Tales, Humbug and Help!, sometimes in collaboration with fellow comics geniuses Will Elder and Jack Davis. In addition, “Kurtzmania,” numerous rare artifacts and ancillary publications seldom seen by the public, will be on display. The Society of Illustrators, founded in 1901, is the oldest nonprofit organization solely dedicated to the art and appreciation of illustration in America. Prominent Society members have been Maxfield Parrish, N.C. Wyeth and Norman Rockwell, among others. The Museum of American Illustration was established by the Society in 1981 and is located in the Society’s vintage 1875 carriage house building in mid-town Manhattan.

HERBLOCK PRIZE GOES TO ANOTHER “ALTIE” At DailyCartoonist, Alan Gardner announced that, for the second year in a row, an “altie” has won the Herblock Prize for editorial cartooning. The 2013 winner announced is Dan Perkins (AKA Tom Tomorrow) creator of This Modern World, which appears in approximately 80 newspapers, mostly alternate weeklies. Perkins is also editor of the comics section he created in April 2011 on Daily Kos. This year’s judges included last year’s winner Matt Bors, Jenny Rob of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University and Steve Brodner, caricaturist and satirical illustrator for Esquire, The Progressive, The New Yorker and others. The Prize, a sterling silver Tiffany trophy, is accompanied by an after-tax cash award of $15,000. Jack Ohman, the newly hired editorial cartoonist for the Sacramento Bee, was named this year’s finalist, no doubt thrilling his new employer and justifying the wisdom they displayed in hiring him. He will receive a $5,000 after-tax cash prize. Gardner quotes at length from the Herb Block Foundation press release: The judges felt there were many strong portfolios in this year’s contest, including several animated-only entries and other alternative multi-panel submissions. Bors said Tom Tomorrow’s portfolio included “hands down, some of the smartest political cartoons of the year.” Subjects included “consistently hilarious takedowns of women-bashers, gun culture and the president’s abuse of executive power.” “Tom Tomorrow is both fearless and funny, two qualities that make him a first-rate editorial cartoonist,” Robb said. “He has developed a unique graphic style that perfectly suits his wry and clever assaults on politicians, political parties, and bad policies while also making his work instantly recognizable.” Brodner said, “Dan Perkins’ output for the year was consistently strong, intelligent and witty. The work discussed the most important issues in a way extremely compelling and illuminating. The sequential political cartoon is a vivid and powerful form in his hands.” The judges also had energetic praise for Ohman’s work. Said Robb: “In addition to producing strong traditional editorial cartoons, Jack Ohman has developed a unique and effective multi-panel strip that is part journalism, part memoir and part satire. He courageously used the format and his platform at The Oregonian [his previous gig, where he was for almost 30 years] to effect change in his local community and to focus attention on issues of both local and national importance.” Brodner added that Ohman’s work is “politically brave, formalistically daring and artistically free, while retaining great design and draftsmanship.” It’s gratifying to read assessments of a cartoonists’ prize-winning work that are not simply trumped-up adjectival excesses, as so often issue from the Pulitzer judges (who usually include at least one cartoonist but are otherwise wordsmiths, blatantly ignorant of the satirical function of imagery in cartoons not to mention the visual appeal of a confident line in line art; and their ignorance shows in their verbal analyses). Incidentally, Perkins’ graphic style, about which Robb raved, is achieved through a unique maneuver. He starts with photographs of political figures or characters from 1950s advertisements. He makes high-contrast photocopies of these visages and then he traces, or outlines, the faces with a pen. That’s how he “draws.” I’m not sure that he still does it this way, but, judging from the appearance of the strip—that curiously bland, lifeless parade of faces—he probably does. Here’s a couple recent episodes of This Modern World.

OSCAR DIMMED I’ve never been a Family Guy fan. The jokes, if that’s what they are, are so far over my head that they aren’t funny. So I shouldn’t have been surprised that Seth MacFarlane emerged at the Academy Awards as the champion lackluster host of all time. He did it on purpose, of course—being unfunny and bombing is Family Guy comedy. Still, I think it was a mistake to spend the opening minutes setting up for his failure by taking tips from Captain Kirk; I knew right then that he wouldn’t be very good because if he was, the joke of the show would fail. Songs were the highpoint of the evening—Barbra Streisand’s tribute to Marvin Hamlisch and Dame Shirley Bassey singing “Goldfinger” one more time for all the Bond fans. But MacFarlane’s outrageous “We Saw Your Boobs” never quite got beyond being simply outrageous; and then I spent the rest of the evening waiting for a sequel, “Show Us Your Tits.” Or something similarly snappy. What, by the way, happened to Jan Eliot’s advisory in her strip, Stone Soup, “You Can’t Say Boobs on Sunday,” a prohibition every syndicated cartoonist has drummed in his/her head from the start. (And the title of a collection of the strip.) The dictum exists because kids read the comics on Sundays. Maybe they also watch Oscar. Shocking, just shocking. Or completely puerile and pre-pubescent, typical of the Family Guy.

ANOTHER EDITOONIST CASUALTY Veteran editoonist Jimmy Margulies was fired in mid-February at Hackensack New Jersey’s The Record. Again, as in the cases of so many of his colleagues lately, the newspaper was simply eliminating a cost, cutting an expense in financially troubled times. With Margulies’ departure, only 52 editoonists hold full-time staff positions in American newspapers; there were 101 in May 2008, just five years ago. Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com talked with Margulies shortly after his rude separation from the paper he’d worked at for 22 years. Margulies said his firing came as a surprise: “I was given no advance notice that I was going to lose my job,” he said. “When I arrived at work on Thursday, the editorial page editor, my supervisor, told me we had to go to Human Resources to meet with the editor-in-chief. So I realized that this was going to be the way they tell you your job is eliminated, even before they actually said the words. I was laid off. But earlier in February, the company did offer buyouts to those over 60 with 15 or more years of service, so I was one of those. I was not interested in leaving at that point. The buyout offer was due to some unfavorable revenue projections, and they also mentioned that other measures, including layoffs might occur. I was given the same severance that was offered to those taking buyouts, plus I will get unemployment since I did not leave voluntarily.” At the time of Gardner’s “exit interview” with Margulies, the editoonist was just beginning to plan for his future cartooning career. He will do a cartoon on a local topic for the paper’s Sunday issue. And if there are special New Jersey issues, he’ll be asked to do cartoons about them from time to time. Margulies will also continue doing editoons for syndication by King Features, and he will continue self-syndicating cartoons on New Jersey issues to newspapers around the state as soon as he can set up the technology to continue both from his home. The things Margulies remembers about his career at The Record include having won some national awards (National Headliner Award, Fischetti Editorial Cartoon Competition, Berryman Award, and 4 Clarion Awards from the Association for Women in Communications). He also remembers fondly when a former acting governor, Donald DiFrancesco, held up one of his cartoons as partially to blame for his decision to withdrawn from the governor’s race in 2001. And Margulies added: “I will miss the idea of my work appearing in a regular spot six days a week in the same publication.” Here are a couple of his cartoons.

WILL EISNER WEEK At publishersweekly.com, Calvin Reid reports that Will Eisner Week, March 1-10, features a series of events to be held in more than a dozen cities around the country to honor the work and career of the great comics innovator Will Eisner (1917-2005), the comics medium and the graphic novel format. Organized by the Will and Ann Eisner Family Foundation, Will Eisner Week 2013 also marks the 35th anniversary of the publication of A Contract With God, Eisner’s acclaimed and pioneering 1978 collection of comics short stories. Events will be held in Savanah, Ga., Arkadelphia, Ar, Portland, Or., Minneapolis, Minn., New York, San Francisco, Seattle and other towns. Events include everything from screening “Portrait of a Sequential Artist,” a documentary on Eisner, to readings from his graphic novels and panel discussions to lectures on his works. For more information and a schedule all the events slated for Will Eisner Week check out the Will Eisner website.

MOTS & QUOTES “The best way to be boring is to leave nothing out.”—Voltaire “It is better to live rich than to die rich.”—Samuel Johnson “There is no such thing as bad weather, only inappropriate clothing.”—Explorer Sr Ranulph Fiennes

Ding Dong—The Witch Is Dead WERTHAM PROVED A FRAUD I Always Suspected He Was FREDERIC WERTHAM, BETE NOIR OF FUNNYBOOK HISTORY, was back in the news last month. But he’s never been far out of sight for fans of the medium that he so strenuously castigated in his 1954 screed, Seduction of the Innocent, that scarbrous tome that contended that comic books were primers for criminal behavior, that youngsters who read them usually turned into juvenile delinquents—or, worse, adult crooks and/or sexual perverts. So sensationally successful was his book at destroying the pernicious comic book that Wertham has hovered over the comics industry ever since like a Joe Btfsplk cloud of doom. When I finally read the book in 1986, preparing to review it for The Comics Journal (the review appeared in No.106, March 1986 and again in Harv’s Hindsights, March 2007), the first thing I found out was that although I’d never read it, the book was not going unread. The libraries of the University of Illinois carried over a dozen copies of it—and they were all checked out. The one I finally laid my hands on had been checked out five times a year since 1980. Wertham was dead, but his book was getting around plenty. But this time—last month—the Wertham news wasn’t so good for the good doctor. Maren Williams at Comic Book Legal Defense Fund summarized the Current Wertham Event on February 13: “Although it is already fairly obvious to most modern-day readers that Wertham’s conclusions were laughable and completely groundless, new research proves that even the ‘supporting evidence’ in the book was largely fabricated. Carol Tilley, a University of Illinois professor of Library Science, compared Wertham’s notes to the final published version of Seduction and found that ‘the doctor revised children’s ages, distorted their quotes, omitted other causal factors and in general played fast and loose with the data he gathered on comics.’” Wertham died in 1981. His archives, at the Library of Congress, weren’t made widely available to researchers until the spring of 2010. Within a few months, Tilley, who teaches media literacy, youth services librarianship and a readers’ advisory course on comics at the University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science, was digging through the dozens of boxes of “Seduction” files in search of connections he may have made with teachers and librarians and found instead that Wertham falsified his alleged research and misrepresented so-called facts in his notorious tome. In flagrant violation of custom in scientific literature, Wertham’s book lacks citations and a bibliography so his so-called “data” can scarcely be verified. But Tilley managed verification of a sort: she verified the absence of scientific method in Wertham’s procedures. “Lots of people have suspected for years that Wertham fudged his so-called clinical evidence in arguing against comics, but there’s been no proof,” Tilley said, reported by Dusty Rhodes at news.illinois.edu. “My research is the first definitive indication that he misrepresented and altered children’s own words about comics.” She found, Williams said, “that misrepresentations were repeated so often in Seduction that there can be no doubt that they were deliberate: ‘[Wertham] ... would take things from different days, from different parts of a transcript, reorganize them, omit words, make small changes that, in effect, change the kids’ arguments or change their viewpoints. He did this in so many instances that it’s hard to overlook.’” Perhaps Wertham was following accepted “scientific methods” of his day, but that seems highly unlikely. Tilley’s 30-page report on her findings, “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped Condemn Comics,” can be found in the November-December 2012 issue of the journal Information & Culture. Reporting on Tilley’s research in the New York Times, Dave Itzkoff writes that Wertham “may have exaggerated the number of youths he worked with at the low-cost mental-health clinic he established in Harlem, who might have totaled in the hundreds instead of the ‘many thousands’ he claimed. Tilley said he misstated their ages, combined quotations taken from many children to appear as if they came from one speaker and attributed remarks said by a single speaker to larger groups. “Other examples show how Wertham omitted extenuating circumstances in the lives of his patients, who often came from families marred by violence and substance abuse, or invented details outright.” Itzkoff refers to the book’s infamous passage about how Batman and Robin comics “represent ‘a wish dream of two homosexuals living together,’” with Wertham quoting in support of his theory “a young gay man who says that he put himself ‘in the position of Robin’ and ‘did want to have relations with Batman.’ “But in Wertham’s original notes,” Itzkoff goes on, “Tilley writes, these quotations actually come from two young men, ages 16 and 17, who were in a sexual relationship with each other, and who told Wertham they were more likely to fantasize about heroes like Tarzan or the Sub-Mariner, rather than Batman and Robin.” Rhodes notes that “Tilley’s article also cites the case of Dorothy, a 13-year-old whose chronic truancy Wertham ascribed to her admiration for the comic book heroine Sheena and ‘crime comics,’ omitting any mention of other factors listed in her case notes, such as her low intelligence, her reading disability, her gang membership, her sexual activity and her status as a runaway. Wertham also didn’t reveal that he never personally met or observed Dorothy; she was the patient of his associate, Dr. Hilde Mosse. “‘He does take some things verbatim from the transcript,’ Tilley said, ‘but then he also would take things from different days, from different parts of a transcript, reorganize them, omit words, make small changes that, in effect, change the kids’ arguments or change their viewpoints. He did this in so many instances that it’s hard to overlook.’” These problems were completely overlooked in the months of Seduction’s fame in 1954. Apparently readers in those dear distant days were a lot less sophisticated in their grasp of scientific method than the average reader is today. The New York Times called Seduction “a most commendable use of the professional mind in the service of the public.” Gratifying as it is—fiendishly so—to learn how Wertham manipulated his facts to arrive at his incendiary conclusions, most present-day readers realize Wertham’s book was somehow not right. Itzkoff contacted Michael Chabon, whose Pulitzer-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay rehearsed the lives and careers of two fictional comic book creators in the thirties and forties, and Chabon said: “You read the book, it just smells wrong. It’s clear he got completely carried away with his obsession, in an almost Ahab-like way.” For Paul Levitz, a former president and publisher of DC Comics, who represented the company on the board of the industry’s self-censoring Comics Magazine Association of America, the revelation that Wertham “cheated on his homework” was “nice to see as a postscript,” he said, “but it’s so long after all the harm has been done. The people he hurt most are almost all in their graves.”

WHAT I SAID 27 YEARS AGO. (Geez I’ve been at this a long time; 27 years! Offta!). A few years ago (fewer than 27), I heard that Seduction of the Innocent, long out of print, had been reprinted by at least two publishers, Amereon (dated 1996); the other, from Main Road Books, is copyrighted 2004. My copy is one of the latter (limited, it says, to 220 copies), and it features a lengthy introduction by James E. Reibman, who teaches literature and media studies at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. Although a specialist in law and literature with publication on the legal writings of Samuel Johnson and his circle, Reibman is Wertham’s biographer and is co-editor of the Fredric Wertham Reader (which may, by now, be published although my search turned up nothing). Reibman is understandably distressed that Wertham’s reputation has apparently been determined entirely by comics aficionados who have turned the psychiatrist into a compunctionless censor and detest him for it. Eager to rescue Wertham, Reibman spends his introduction rehearsing the doctor’s his life, beginning with his birth March 20, 1895, in Nuremberg, Germany, and ending with his death November 18, 1981, in the United States. Wertham came to the U.S. in 1922 and worked for seven years at the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he met Florence Hesketh, an artist and Charlton Fellow in Medicine, who became Wertham’s wife and intellectual partner. As an indication of Wertham’s social and mental gifts, Reibman notes that while Wertham lived in Baltimore, he frequently gathered with H.L. Mencken and his musical cohorts for the meetings of the fabled Saturday Night Club, a weekly soiree of good food and drink, rousing music, and stimulating conversation. I have a hard time imagining Wertham in Mencken’s circle, but that’s what it sez here. Wertham authored at least ten books, most of them on social and/or psychiatric issues, and he emerged as a distinguished psychiatric witness in legal matters, more good guy than bad. His testimony in a Delaware case about the impairment suffered by African American children due to school segregation became part of the legal argument in the famed Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine, laying the groundwork for desegregation of schools (and of the rest of America). And Wertham was appointed psychiatric consultant to Senator Estes Kefauver’s Subcomittee for the Study of Organized Crime, out of which, eventually, came the subcommittee investigating the deleterious impact of comic books. Wertham was not, in other words, a kook or a crackpot. I’ve never supposed he was. He

was notable enough in 1949 to be on the cover of the Saturday Review of

Literature, a respectable and usually liberal weekly; I’ve posted the

picture near here. I have always thought that Seduction of the Innocent was a Book of the Month Club selection, but apparently it wasn’t. It was scheduled to be the Club’s “alternative selection” one month, but at the last minute that plan was cancelled for reasons Reibman doesn’t specify; we may suppose were the most sinister from his subsequent assertion that the book’s publisher had torn out of the volume pages 399 and 400 because they listed the publishers of the comic books Wertham castigated. (These pages have been restored to the edition I have; and probably to the other one, too. In any event, you should look for them in order to reassure yourself that you have a complete and valid reproduction of the original volume.) The reprinted volume at hand also includes the horrifying illustrations Wertham had plucked from assorted sordid comic books. Tilley’s report on her Wertham research is particularly gratifying to me because it supports in scientific terms what I suspected when I read it in 1986. If Wertham wasn’t a phoney, he certainly behaved like one when writing the book that purported to be based upon “science.” Ironically, he frequently pooh-poohs the work of others whose conclusions he disagrees with by calling their efforts “unscientific.” What delicious comeuppance.

What Follows Next Are Excerpts from My 27-Year-Old 1986 Review. The book itself (as I said then and still believe) is a simmering stew of accusations and innuendo, a grab-bag of examples, case histories, anecdotes, facts, near-facts, and (I suspect) some fictions. Wertham employs some classic rhetorical devices, steeped in fallacious logic, including guilt by association (if there are deviants among the customers at a comics shop, comics must perforce be perverted) and representing simple sequence as cause-and-effect. One paragraph includes this insidious rhetoric: “Our researches have proved that there is a significant correlation between crime comics reading and the more serious forms of juvenile delinquency. Many children read only a few comics, read them for only a short time, read the better type (to the extent that there is a better type) and do not become imbued with the whole crime comics atmosphere. Those children, on the other hand, who commit the more serious types of delinquency nowadays, read a lot of comic books, go in for the worst type of crime comics, read them for a long time, and live in thought in the crime comics world.” In this paragraph of seemingly conclusive indictment, the opening reference to “our researches” and to “significant correlation” creates a scientific aura into which Wertham then insinuates his damning juxtaposition of facts. He first admits disarmingly that some children who read comics do not become criminals. Then he couples his damning facts: (1) serious juvenile criminals (2) are constant comic book readers. The implication is that the second fact created the first. Maybe that’s true. But maybe, as in a previous example, young criminals prefer to read about crime. (And, being poorly educated, maybe they don’t enjoy reading prose text but prefer the picture storytelling of comic books.) In another place, he talks about various actions, calling them “comic book plots,” but asserting the similarity is not the same as proving that the crimes were cauzed by comic books. He asserts a similarity, insinuating a causal relationship.

***** A lengthy chapter in which he attempts to prove that comic books are bad for learning to read is the least convincing in Wertham’s book. The long passages defining and discussing a variety of reading disorders (sprinkled with an assortment of paeans to the importance of reading for a good and successful life) camouflage the fact that he is unable to demonstrate a causal relationship between habitual comic book “perusal” and inability to read. He asserts that “not a single good psychological study based on scientific data can show that comic books may help children to read.” But he can’t find one that shows bad readers are created by comic books either.

***** For a scientist, Wertham expects us to assume an awful lot. He gives us no statistics, no raw (or refined) numbers. Perhaps Wertham didn’t keep score. (If not, what of his pretension to scientific method?) And so we are left to ponder a most pertinent question: What percentage of the children’s productions were “destructive”? If only one of every ten plays were “destructive,” how malevolent is the influence of comics? Not very—given the quantity of comic books kids read. On the other hand, if seven of every ten were “destructive,” comic books could clearly be charged with shaping children’s minds to their detriment. But Wertham gives us no numbers. He either can’t (because he has no score card) or he doesn’t (because numbers would weaken his case?). If he can’t, his science is surely questionable; if he doesn’t, his integrity is suspect. In the absence of any kind of statistical evidence, rhetoric alone makes the case against comics as the sole source of destructive ideas in children. Although most of Wertham’s evidence was assembled through his clinical contact with children, he reports in some detail the results of one study that involved a significant number of non-clinical children. Ironically, the results tend to undermine Wertham’s contention that comics corrupt youth. Astonishingly, Wertham doesn’t seem aware of it. The study in question took place with 355 children enrolled in a parochial school “where ethical teaching played a large part and all the children had undergone this uniform influence.” The children all came from better-than-average homes economically. School authorities assumed that these children read only the better comics, but Wertham found that they read the “bad” ones, too. (And he makes much of this fact: “school authorities had misjudged the comic book situation, and under their very eyes, many of these children were being seduced by the industry.”) Wertham says the kids’ comments were revealing. Here they are. About Superman, a boy said, “It teaches ‘crime does not pay’—but it teaches crime.” Other comments: Superman is bad because they make him sort or a God. Superman is bad because if the children believe Superman they will believe almost anything. I think they (crime comics) are bad, but good to read. Some are dirty, some give you bad thoughts. Some comic books lead us into sin. The children’s remarks included such phrases as “impure dress,” “indecency,” “they are not modest,” and the like. “Many children,” Wertham writes, “have received a false concept of love, thinking of it as something dirty. They lump together love, murder, and robbery.” From all of this, Wertham concludes that these children get from comic books “just the opposite of what they learn at school or at home.” But a person anxious about the corrupting influence of comics should derive some comfort from most of the children’s remarks. Most of them reveal that the ethical teaching of the school “took.” Most of the children recognized the so-called “bad” comics as something bad. If so, they are scarcely being “seduced” as Wertham claims. They are, in fact, doing precisely what their teachers and parents presumably hoped they would do under the circumstances: they are rejecting the immoral blandishments they encounter. Amazingly, Wertham fails to see this aspect of this study. Or ignores it. After all, if children properly grounded in moral concerns reject the corrupting influence of comic books, much of his case threatens to fall apart. Certainly there is less for the average parent to be alarmed about. And Wertham has written this entire tome in order to raise the alarm. This study is the only one that Wertham reports on at length that does not involve patients in a psychiatric clinic or children brought to him for consultation. Given the parochial and economic background of these children, they are probably not “average.” But psychologically, they are closer to being “normal” than patients in Wertham’s clinic. One way to establish proof is to look to the scientific method. And Wertham indeed glances in that direction. But the proofs of science should be verifiable through repetition. The proof emerges when a given phenomenon can be explained every time it occurs. The power of the proof stems from its ability to predict outcomes. Wertham was unable to construct this kind of proof. He was unable to prove that the reading of crime comics always produced criminal or aberrant behavior in young readers. He was unable even to identify with clinical precision the psychological make-up of youngsters who might be the most vulnerable to the temptations flaunted before them in crime comics. Wertham is not much bothered by this sort of failure. “It proves nothing,” he says, that only a few of the many children who read comics become delinquent. “Innumerable poor people never commit a crime, and yet poverty is one of the causes of crime. Many children are exposed to the polio virus; few come down with the disease. Is that supposed to prove that polio virus is innocuous?” But this is the rhetoric of the conjurer not the proof of the scientist. For another kind of proof, we look to courts of law with their rules of evidence. One objective in a trial is to establish through evidence that a defendant is “guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.” It’s the prosecutor’s objective, and Wertham plays that role here. Would a jury bring in a verdict that comics were guilty as charged? Did Wertham prove that guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt”? Historically, judging from the results Wertham wrought, the jury found for the people, against the defendant. Wertham won. But what about a jury of his readers today? I, for one, have reasonable doubts. And those doubts will remain as long as so much of Wertham’s evidence admits of more than one interpretation. In too many of his examples of comic book readers gone wrong, the errant youths could have been led into the error of their ways by something other than comics. While Wertham presents some telling evidence (kids who hanged themselves enacting comic book stories, for instance), the argumentative force is overpowered by the sometimes not so faint odor that clings to the mud-slinger. Wertham so frequently attempts to indict by evidence of association rather than of causation that he raises doubts about his motives and his methods. If we doubt either, we must question too the authority of his evidence as a whole. Considered as scientific document, Seduction of the Innocent is more insinuation than proof; as a trial brief, more innuendo than evidence. But if the book is considered as literary criticism, it gains modest stature.

***** And for the effect of that, go to Harv’s Hindsight for March 2006, “Why Can’t Bad Comics Have Bad Effects?” As a literary critic, Wertham has some validity; as a scientist, none whatsoever—as has finally been demonstrated by Carol Tilley. And

before I scamper off for another AWOL week, here in the corner of your eye is a

cartoon, a four-panel comic strip “history” of Wertham’s crusade, that I drew

about the time I wrote the original review of Seduction of the Innocent. If the part of the evil comic book industry is played by a femme fatale in a trench coat (and nothing else), anyone brought up on Mad comics, as I was, can predict how Wertham will react. So he ignores the comic book industry in order to peruse, feverishly—obsessively—the comic books themselves? That doesn’t make much sense. Maybe it means that he is so absorbed in his crusade that he ignores real life? Or maybe our femme fatale is not the comic book industry at all. She’s just a naked woman in a trenchcoat who has lots of comic books under the coat—a classic image of the pornographer in the alley, selling dirty pictures to innocent passersby. But what attracts and holds Wertham’s attention is not so human as a naked woman, but comic books, four-color fantasies. So the cartoon is about Wertham’s obsession. Other than that, I can’t say for sure, so frail is my grasp of the cartoon itself. It ridicules Wertham, that’s for sure; but how, exactly—other than by showing him to be obsessive—I’m not sure. Maybe showing him to be obsessive is enough. I like a lot of the things about this comic, er, strip: the gal’s beret, f’instance, seems nicely done; ditto the stress-marks in the fabric of the back of the trenchcoat when she opens it, and her innocent expression and the torque of her torso in the last panel. And who could resist placing a comic book entitled “Wow” where I placed it? Insidious, I know. The caricature of Wertham, made by referring to only one or two photos, isn’t bad either.

BADINAGE AND BAGATELLES To Edward Sorel, tracing is cheating. “If you don’t trace, it’s art,” he said to Budd Mishkin at brooklyn.ny1.com. “For me,” he continued, “working direct—spontaneous direct drawing— is fine art, and tracing is commercial art. That’s the difference.” Sorel credits art director George Lois for reviving his career by offering him the cover of Esquire for Gay Talese’s famed 1966 article “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.” Said Sorel: “What saved my life was the only thing I could do was draw. What saved my life was my incompetence at everything else. So I kept drawing and drawing until finally, I got good at it.”

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

IN THE FIRST OF OUR EXHIBITS, Robb Armstrong is celebrating Black History Month as the month draws to a close. Below that is the only time I can remember that Dilbert shows he has a mouth; he did it in the animated tv series, but not in the strip. Not that I recall. Finally, Jerry Dumas, the mind and hand behind Sam and Silo (and one of the gag-writing team for Beetle Bailey and, if memory serves, Hi and Lois), shows up in Beetle. I can almost hear the team contemplating this gag: what name could they use? No matter how hard they trumped up some ridiculous name, there's probably someone, somewhere, with that name—someone who would promptly write his newspaper and King Features to object to his name be subjected to ridicule and debasement. So rather than risk it, the group picked on one of their number—someone they were sure wouldn't object. Who's next? Brian? Bill? Neal?

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics WHAT I’M READIN’ THESE DAYS As we can see

from the picture on the cover of the sixth issue of Howard Chaykin’s Black

Kiss 2, Chaykin has finally reached the end his 6-issue exploration of

extreme sex. She may (or may not: I can’t tell one woman from another because Chaykin draws them all the same way) be the hermaphrodite who is depicted earlier screwing a man from the rear and saying, in one of the more picturesque utterances of this issue, “Fuck you, you worthless piece of shit. Your ass is mine and your asshole’s not an exit anymore.” On the next page, having finished her penetrating assault, she holds her dick in her hand as she looms over the guy and says to his wife, who has joined them in a three-way: “You should be grateful you get to suck my cock dry and lick your pissant excuse for a husband’s shit off my dick, too.” I’m not sure I needed Chaykin to elucidate all of the implications of anal sex to me. But then, I haven’t been able to find any other redeeming element in this lurid self-indulgence he’s offering as a graphic (in both senses) novel.

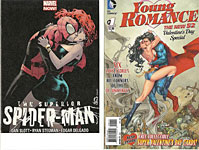

COVER SEX I know: it’s

been going on for years. Sex sells. Everyone knows that, so it’s not surprising

to see that the funnybook industry is finally catching on. Here, for example,

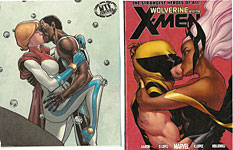

are some covers that were featured in the current issue of Previews. The next cover faces a similar perspective problem, although one not quite so dire. Nicely solved, too. Finally, here’s that classic pre-coital pose that excites all the males amongst us. No perspective problem; just sex. From sex appeal we go to sex in action—well, romance, then.

First come visions of curvaceous loveliness; then, lust—and, finally, groping and gripping. In a month not too far distant, the racks at your local comic book store will be festooned with a rash of cover art depicting superheroes in the throes of romantic grappling. Here we have Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, Superman, Power Girl, Wolverine, and Storm—all pantingly in each other’s clutches. The last two mark something of a cultural advance. Whites passionately embracing blacks and vice versa. As a society, we’ve come a long way indeed when we show different races in love in so obvious a manner—and on the covers of periodicals not entirely directed at adults. In

our last exhibit, we have something else altogether. A different kind of lust. At the right, an out-take from my latest tome, not yet published. This is an illustration by cartoonist Kin Hubbard for a weekly column of fictional country gossip he produced when not doing his daily feature, Abe Martin. (You can see Abe at Opus 162; we’ll be posting an update from the book soon in Harv’s Hindsight.) There’ll be more of the same old timey comedy in the book; don’t miss it. I’ll remind you when it’s available; probably by Christmas. Meanwhile,

here’s the book’s cover design and title that I submitted to University Press

of Mississippi.

READ AND RELISH At the Golden Globes awards ceremony, Jodie Foster came out as a lesbian in a rambling oblique speech. As reported in The Week, accepting the lifetime achievement award, Foster thanked her longtime partner, Cydney Bernard, while revealing they had broken up. Foster had come out to family and friends “back in the Stone Age,” she said, but had insisted on keeping her love life private: “If you have had to fight for a life that felt real and honest and normal against all odds,” she said, “then maybe then you, too, might value privacy above all else.” Bravo.

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status

Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot By Jacques Tardi; his graphic novel adaptation of Jean-Patrick Manchette’s The Prone Gunman 100 7x10.5-inch pages; b/w throughout; 2012 Fantagraphics hardcover, $18.99 IN THIS BLEAK STORY of a professional assassin, Tardi follows Manchette’s Martin Terrier as he makes what he plans to be his last kill, after which, he intends to return to the village of his youth and take up with the girl he left behind him. Turns out he can’t retire just yet; his bosses give him one more assignment. Also turns out his girl is a self-centered snot who wants nothing to do with him. From there, the whole thing starts coming apart for Terrier. The ending is bitterly poetic. Tardi’s art is fascinating to watch—meticulous detail, fat fingers, powerful use of blacks. Relatively simple rendering for a realistic manner, almost cartoony but not quite. And his storytelling is just as meticulous. Terrier is portrayed as a cold, emotionless killer who plans with great care and executes without compunction. This is a “procedural” narrative: Tardi’s manner is to focus carefully on the step-by-step operation of his protagonist. As I read along, I could not avoid the impression that Tardi is a painstakingly faithful adapter of Manchette’s crime novel: there are long passages where this book is more prose than pictures. But Tardi varies perspective and distance enough to restore the visual character of his medium. And there are also passages, somewhat shorter than most, in which he moves the story forward by pictorial means alone. Altogether, a satisfying read with an entirely unexpected ending.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |