|

|||

Opus 267 (September 13, 2010). Our special feature this time is a long and appreciative obituary for Paul Conrad, a colossus among editorial cartoonists for most of the last 50 years. We also regale you with Ted Rall’s reports from his recent investigative trek to Afghanistan (yes: he came back alive) and reveal the secret meaning of Pearls Before Swine and post some of the month’s best editoons. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US Lady Gaga Sues Bluewater Westergaard Gets Free Press Award Tamara Drewe Coming Two Batmen Cat in the Hat on TV

BACK TO AFGHANISTAN Ted Rall Reports and Fumes

OF PIGS AND SWINE The Sordid Truth about Stephan Pastis’ Strip

EDITOONERY Cartoons on the Iraqi Exit, Beck Buffoonery, and Dr. Laura

THE FROTH ESTATE Pistol-packin’ Pastor in the Sunshine State And How the Ever Vigilante Press Fosters An International Crisis

BOOK MARQUEE Carmine Infantino Bio from TwoMorrows

PASSIN’ THROUGH Paul Conrad, 1924-2010

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits The strange gets stranger: Lady Gaga doesn’t want to be a comic book, which is a little surprising because her entire campaign to become a celebrity looks suspiciously like a comic book. But ICv2.com reports that an attorney representing her and Justin Bieber has filed a cease-and-desist letter with Bluewater Productions, the publisher that has added a Gaga funnybook to its Female Forces series, a lineup that actress Betty White is about to join. The 88-year-old tart-tongued actress, currently enjoying a resurgence in her 70-year-long career, will be in good company with Princess Diana, Margaret Thatcher, Oprah Winfrey and Ellen DeGeneres in the Bluewater series. So far, she hasn’t lodged any objection. Bluewater CEO Darren Davis pooh-poohs the Gaga gag order: “We’re 100% within our First Amendment rights,” he told Newsarama. “We knew our rights on this before we jumped into the biography world. These are 100% biographies on their lives.” The attorney for Gaga, Kenneth Feinswog, has some experience in the biographical comic arena: in the early 1990s, he sued Revolutionary Comics over its biographical comics but lost (although Revolutionary had to stop using the New Kids on the Block logo on that comic). But biographical comics, whether authorized or not, are clearly constitutionally protected free speech. Bluewater said the first two printings of Lady Gaga have sold out, and a third printing is planned. A sequel is also in the works. Other stars who also have their own comics include David Beckham and Robert Pattinson Davis said turning White’s long career into a 32-page book wasn't easy. “The biggest challenge that the creative team behind this book faced was figuring out how to include as much of this career as possible in one comic.” White’s other accolades this year include great reviews for her performance in Sandra Bullock's rom-com “The Proposal,” her seventh Emmy (for guest actress in a comedy series, “Saturday Night Live”), the Screen Actor's Guild Lifetime Achievement Award, big laughs for her Super Bowl Snickers commercial, and, later this year, BAFTA LA will present her with the Charlie Chaplin Britannia Award for Excellence in Comedy. She's currently starring in new tv sitcom “Hot in Cleveland.” Female Force: Betty White will be released in November, authorized or not. But my guess is that it won’t be nearly as funny as White is on stage and on screen.

***** From Reuters, we have a report that at a conference on freedom of the press in Berlin on Wednesday, September 8, Kurt Westergaard, the 75-year old Danish cartoonist whose drawing of Mohammad wearing a turban bomb inflamed the Muslim world, received an award during a ceremony at which German Chancellor Angela Merkel risked angering Muslims by speaking. Continuing with a report from Agence France-Presse: "Maybe they will try to kill me and maybe they will have success, but they cannot kill the cartoon," Westergaard told reporters. He also said a clash between Islam—he called it a "reactionary religion"—and Western culture was inevitable and that his cartoon, one of 12 first published in a Danish newspaper in 2005, was merely a "catalyst." Borys Kit and James Hibberd at Hollywood Reporter announce that The Sandman, Neil Gaiman’s comic book series (“considered a seminal work in the medium”) is in the early stages of being developed into a tv series by Warner Bros., which “is in the midst of acquiring television rights from sister company DC Entertainment and in talks with several writer-producers about adapting the 1990s comic.” ... Will Eisner’s graphic novel, A Contract with God—actually a collection of four short stories about life in New York tenements—is being adapted to a live-action feature—actually, four films, each directed by a different director; all under the auspices of the Eisner estate. The

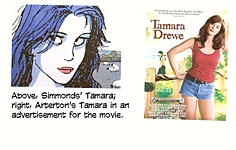

movie “Tamara Drewe” opened at a West End theater in London in early September,

destined, eventually, to reach these shores in October. The movie adapts Tamara

Drewe, the second graphic novel by Posy Simmonds, a British

newspaper cartoonist and writer and illustrator of children's books. Her first

was Gemma Bovery, which was inaugurated serially in The Guardian in 2000; Tamara Drewe also debuted in the paper in installments,

2005-2006. The eponymous Tamara, a journalist, returns to her home in a bucolic

countryside and upsets the order of things, particularly among a colony of

writers seeking their various muses in rural seclusion, by indulging rather

enthusiastically in casual rather than committed sex. The appeal of the graphic

novel, however, lies in Simmonds’ exquisite drawings and her tantalizing

deployment of the visual-verbal aspect of the medium: she varies the traditional

sequential pictorial speech-ballooned narrative with illustrated typeset text

for interior monologues. Beautifully done. About the movie, culturemap.com’s

Brandi Lalanne laments that it will not go over big in this country because the

heroine’s only superpower is her sexual appetite—no armor, no cape, no leaping

over tall buildings with a single bound. After watching the trailer, I

disagree: the actress, Gemma Arterton, playing Tamara in short short cut-offs,

will easily compensate for the lack of costumed machismo. Ron Rogers—who, Rob Tornoe reports at Editor & Publisher, is believed to be the only African American working full-time as an editorial cartoonist at a daily newspaper—has lost his job at the South Bend Tribune. Rogers drew his last cartoon for the Tribune on Friday, September 3. Rogers joined the paper in 2005 after three years of freelancing for them. He told Tornoe: “I really can’t say anything bad about this. The Tribune has done well by me over the years. I was told in late July so I had time to get things together.” By my count (an admittedly hit-or-miss calculation at this point), the total number of full-time staff editoonists in the country is now 79. Albert Ching at Newsarma writes that when Jon Goldwater took over as co-chief executive officer at Archie Comics in June 2009, his goal was to modernize the company's comic book line. That, over the last year, has become deliriously obvious. Ching quotes Goldwater: “One of the things that we immediately identified is that we had to make Archie culturally relevant. I sat down with all the writers, and all the creators, and all the artists, and said, `Look guys—you're completely unshackled. Go do what you want to do. Make it as fun as it can be.'" And the strategy has worked, saith Ching: “This forward-thinking approach has led to widespread mainstream media attention ... and sales statistics have shown steady increases in Archie's market share at comic book retailers since Goldwater took over.” Some things actually do work out happily.

***** Vaneta Rogers at Newarama interviewed DC editor Mike Marts about the advent in November of two Batmen. Bruce Wayne is being resurrected from his presumed death in Batman Inc. by Grant Morrison and Yanick Paquette, and the playboy millionaire will also star in Batman: The Dark Knight by writer/artist David Finch. Meanwhile, in three other titles (Batman, Detective Comics, and Batman & Robin), Dick Grayson, who assumed Batman’s mantle at the supposed death of the original Caped Crusader, will be Batman. Marts admitted that “like most of the big things we've been doing with the Batman group over the last few years,” the idea of two Batmen was conjured up by Grant Morrison. “Most of the big ideas are coming from Grant Morrison's direction.” Will there be two different Batmen “in public”? Can people within the DCU tell there are two different Batmen? Marts turned coy: “That's not quite revealed yet. That's something that will become apparent in the first few issues of our Batman Inc. in November.”

***** The Cat in the Hat, the wrecking-ball feline created by Theodor Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss), debuted on public tv September 5. "The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About That!” kicked off a the fall season for juvenile viewers, reported Rick Bentley at the Fresno Bee, adding: “Geisel wrote The Cat in the Hat in 1957 because he believed American children lagged behind the world in literacy. Taking the characters from page to screen eliminates Geisel's original literary intentions but the author was thinking about other ways to use the Cat in the years before his death.” So this perversion of Dr. Seuss’s purpose is therefore okay? Robert Lloyd, tv critic for the Los Angeles Times, notes that “the show, being made under the watchful eye of Mrs. Dr. Seuss, Audrey Geisel, is in the spiky spirit of her late husband's original—which it only sort of is.” Lloyd continues: "The Cat in the Hat, after all, is the story of a home invasion, during which a fish is terrorized, a rake is bent, and twin Things wreak havoc ‘with hops and big thumps / And all kinds of bad tricks.’ The Cat does clean up his substantial mess, finally, but neither we nor the child-narrator nor his sister have any way of knowing this in advance. It is a tense time meanwhile. (It is also a book that illustrates lying to mom.) There is silliness here [in the tv adaptation] but no danger, and little children Sally and Nick ask their mothers' permission before flying off with the Cat (and Thing 1 and Thing 2 and the ever-fretful Fish) in his super-convertible Thinga-ma-jigger. It is always a little sad when a wild thing is tamed, but that is not a thought liable to distract this show's intended audience—and the Cat was about incidental education anyway.” On the same day, reports Hero Complex contributor Noelene Clark at latimes.blog, Mad debuted on the Cartoon Network. "Spy vs. Spy" and other Mad magazine classics will join a host of new animated sketches—such as "CSiCarly," "2012 Dalmatians" and "Batman Family Feud"—in "MAD," a new 15-minute animated series based on the irreverent humor magazine.

***** Scott Kurtz is releasing the latest print collection of his popular online comic PvP but not through his erstwhile publisher Image Comics according to an official announcement from comicbookresources.com: “After 8 years with Image, PvP is returning to its self-publishing roots, printing all future collections under the Toonhound Studios banner and selling them online via PvP's store at pvpstuff.com. "Over the last three years our business has shifted," says Kurtz. "Sales through brick-and-mortar stores are declining and online sales are increasing. Readers who discovered PvP in comic shops have shifted from monthly readers to online readers, and their buying habits have changed. The monthly floppy is selling less and the trade paperbacks are selling more." All existing compilations of PvP are still available from Image Comics through Diamond Distribution, including the PvP Awesomeology hardcover, a 600-page retrospective celebrating the strip's recent ten-year anniversary. The PvP monthly comic book, which Image also published, has been cancelled and ended with No. 45. Said Kurtz: "Image has been an amazing publisher. Jim Valentino believed in Webcomics before anyone else in the industry. Erik Larsen and Eric Stephenson were instrumental in helping PvP shine. I still believe that Image is the best game in town for independent creators. I'm proud to continue offering my existing trades through them.”

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

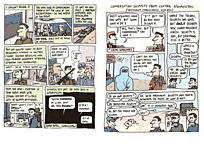

BACK TO AFGHANISTAN We’ve brought this to your attention before, so now we’re just dropping some more footwear. Ted Rall, cartooner and professional gadfly, is back from Afghanistan. He’s journeyed through that neck of the woods several times over the years—most notably, in the fall of 2001 immediately after the catastrophe of 9/11, producing an account of his adventures in book form (part comic strip; part narrative text) entitled To Afghanistan and Back (the first book-length report about the U.S. invasion of that country)—and this summer, he went back there again, but his objective this time was a little different, as he explains in the current issue of The Notebook, the newsletter of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (of which he was recently president). Rall says he is drawn to “the Stans” “like a moth to a flame.” In 2001, he goes on, “I experienced Afghanistan as a ‘war tourist.’ ... This time, I’m out to get the point-of-view of the Afghan people: how their lives have changed since then, and of course how they see the U.S. occupation. I have long loved Central Asia. The people and the history are amazing ... I am also compelled to try to correct so much reporting about Afghanistan that I think is plain wrong.” His plan was to travel to the north and west of the country, including some areas into which official America does not venture. “The biggest challenge is physical,” he said as he set out. “The food is awful, the beds are infested with parasites, the heat is brutal and you get banged around a lot on terrible roads. Of course, there’s tension. Robbers, corrupt cops, thieves, IEDs—all figure into the equation. You’re constantly scared and bored at the same time.” Rall was accompanied by two other cartoonists: Matt Bors, with whom Rall is collaborating on his next autobiographical book (Bors, once found only in the pages of alternative papers, is syndicated by United Feature Syndicate); and Steve Cloud, another altie (his Boy On A Stick and Slither is still on the Web), who met Rall when the latter was acquisitions editor for United Media. As “Team Afghanistan” trekked through sand and heat, death and corruption (both corporeal and political), Rall regularly posted cartoon reportage on their adventures. You can try looking for the daily installments at rall.com/rallblog/2010/08/07/afghan-blog The early reports concern preparations for the trip and some maps, showing where they hoped to journey. Then come some orientation strips, among which, reports of Rall’s attempts to find the “fixer” he employed last time he was there (the guy who translates and negotiates their way through bureaucratic outlaw obstacles and cultural suspicion). Finally, by about the 15th installment, we start seeing the trio at their fate. Much to his astonishment, Rall found hundreds of miles of paved roads, none of which existed when he was in the country in 2001. “This might have made a favorable impression on Afghans prior to 2003, but now it appears to be too late. Everyone knows the Taliban will soon be back in charge. Women are still in burqas, same as it ever was. Business is booming, but poverty remains widespread. And American troops are still acting like assholes—buzzing through town at high speeds, terrorizing the Afghans they’re supposedly there to help.” But Americans aren’t the only assholes, as Rall explained in his syndicated columns posted from Afghanistan. Time magazine, he wrote, said the Taliban would “sweep back into power after a U.S. withdrawal,” brutalizing Afghans and “stuffing them back under burqas. But the Taliban never left. Neither did the repression.” Today’s Taliban, however, are not the scrupulously honest, ascetics of Mullah Omar. Today’s Taliban are “biker gangs from hell. They’re still radical Islamists. But they’re also gangsters, brazen thieves who have adopted the thuggish behavior of the warlord class during the so-called ‘mujahedeen nights’ of the early 1990s. ... [They] set up checkpoints and ambush points to catch motorists. They’re yanked out of their cars, robbed at gunpoint, and sent on their way—if the victims are lucky. Many have been shot to death. “Everyone expects the Taliban to control most, if not all, of Afghanistan by next year,” Rall continued. But the question is: which Taliban? “I foresee a clash, perhaps even a civil war, between the ‘real Taliban’ of yore (sales pitch: we’re tough but honest) and these self-branded Talib-cum-robbers (motto: shut up and pay up).”

RALL WANTED TO SEE if the rumored oil pipeline across Afghanistan—to protect which he has long maintained was the ultimate cause of the U.S. invasion—was being constructed, which it is, according to serious gossip. But when they got where the pipeline was supposed to be, there was no evidence of any construction. In one of Rall’s last reports, the “Tres Amigos” were suffering from military escort, into which they fell, more-or-less accidentally. It was this sort of “officialdom” that Rall sought to avoid at all cost because it draws attention to those being escorted and would, in this case, sabotage their efforts to find real Afghans and hear what they have to say. Here are a couple excerpts from Rall’s running account.

On September 2, Rall posted in his syndicated column the following somewhat morbid thoughts inspired by the danger of their enterprise, stalked by Death all the way (all in italic): Yes, I'll probably be fine. But if I die, I would like to ask my colleagues in the media—those assigned to write my obituary, should I be deemed to rate one—to spare me hypocritical bullshit praise. I'm not talking about the hundreds of publications and broadcast outlets who have been kind to me over the years. I am amazed and humbled that anyone likes my stuff; I am still humbled when I see my name in print. I'm talking about the outlets that have always snubbed me. Which is their right. Go ahead, snub like the wind! But don't pretend you're sad when I croak. ... Times editors, please don't sing my praises in the obituaries. Don't talk about how I was once the youngest syndicated cartoonist in the country, how I won a bunch of awards, how I helped revolutionize an art form, how my work was controversial and widely discussed, how cool it was that I went to Afghanistan and Central Asia. If you really thought I was great, you would have run my stuff. You didn't. You thought I sucked. Or you didn't have the guts to deal with angry readers. Either way: shut the @#$% up. ... This also goes for USA Today, which wallows in cartoon crapitude day after day. You never ran one of my cartoons. I've done more than 4,000 of them. Not one ever appeared in USA Today. Not one in 20 years. If you mention my death, please include an explanation of why I'm worth mentioning but not worth publishing. If your explanation somehow involves peanut butter that would be cool. ... Special you-ignored-me-my-entire-career-so-don't-suck-up-after-I-die shoutouts also go to the Washington Post, which canceled me in response to a write-in campaign by right-wing extremists, and the San Francisco Chronicle, NPR, and every newspaper in my home state of Ohio. When I shed my mortal coil and shuffle off to the great open bar full of funny cartoonists and loose women in the sky, whenever that happens, I beg you to do me one last favor: say that I suck. Or, better yet, don't mention me at all. That’s our Rall: grace under pressure. But, withal, a daring young man; I contributed to his travel fund, and I’m eager to see his final report, which, I assume, will brim as much with undigested bile as the foregoing. I’m

also eager to see his very next tome, The Anti-American Manifesto.

Rall’s most radical book yet, it is reputed to argue that the economic and

political collapse of the United States provides an opportunity for justice-

and equality-minded people to launch a revolution to overthrow the oppressive

capitalist system. Heavy-duty satire.

THE ORIGINAL PLAN was to leave Afghanistan via Iran on about September 6, but instead, Rall and Company returned, intact, on September 9 or so, whereupon, Rall asked those who are tuned in on the AAEC List: “Did we miss anything while out of the country?” An outspoken member of the List (they all are loquacious in the extreme so this description doesn’t give anything away) ran though a litany of recent crises: “Castro rethought communism, Obama wants same tax cuts McCain ran on, Hamas supporter wants to build a GZero mosque, he's raised $16K so far but America panics, The Donald wants to buy it, Ameriphobes want to know why we're Islamophobes, Fla. preacher wants to burn a wagon load of korans, the already hair trigger Religion of Perpetual Outrage now has reason to be outraged, just when you thought this couldn't get any weirder, the Black Panthers show up and the Obamas have taken 36 vacations. Maybe you ran into them?” Another added: “We were taken over by the Tea-liban while you were gone.” To which, Rall reposited: “Wow. Wasn't anyone in charge while we were gone?” Which, in turn, elicited this: “Just some nutjob preacher down in Florida.” As you can see, this sort of exchange among inspired inkslingers can go on forever.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. As reported in Faux News, Sarah the Palin defended her use of the unorthodox “refudiate,” saying the word can be found in any reputable fictionary. She also “lashed out at critics of her English, calling them ‘incohecent.’”

OF PIGS AND SWINE I finally figured it out—who the swine are. I’ve been

saying, all along, that Stephan Pastis deliberately insults his readers

by naming his comic strip Pearls Before Swine. We, the readers, I

assumed, are the swine in front of which Pastis casts his pearly comedy. Well,

imagine my surprise when I figured out an alternative interpretation—with the

aid of this strip, deeply coded to reveal Pastis’ Secret. A

week or so before encountering our first visual aid, I ran up against the next

one. But

that hasn’t stopped the infestation of the comics pages with stick figures,

drawn, no doubt, by those who aspire to the fame and fortune Pastis is

presently enjoying; herewith—. Even

somewhat more somber literary types are into stick figures, namely Jeffrey

Metzner, whose book, Stick: Great Moments in Art, History, Film and More,

includes page after page of action-packed synopses of literary works,

historical events and the like, to wit, clockwise from the upper left: The

Hound of the Baskervilles, Peter Pan, The Three Musketeers, and Gulliver’s Travels. Arthur Conan Doyle, J.M. Barrie, Alex Dumas, and John

Swift are doubtless rejoicing at being illustrated by someone other than N.C.

Wyeth. Meanwhile, Pastis contends with anyone who feigns interest that he is a wholly unschooled cartoonist. He is glad that he has no art or drawing training: this void in his resume has been a professional benefit, he says. "I think the fact that I don't know anything makes me do it my way," he said. "It's the punk rock theory of cartooning: teach three chords and see what happens." What happened, Pam Lundborg reports at her blog.syracuse.com, was Pastis created one of the most popular comics in the country. Pearls Before Swine, which is named after a Bible verse that discusses wasting wisdom on someone who won't listen (see? I knew I had that part right), is syndicated in about 650 newspapers, according to Pastis. Pearls is often compared to the edgy television cartoons "Family Guy" and "South Park." But Pastis dismisses the comparison. These tv cartoons, he told Lundborg, are allowed to be edgy. Newspaper cartoons, he said, are still 50 years away from that level of spunk. "Saying 'poop' gives you trouble. 'Hell' gives you trouble," he said. "Saying 'sucks' is an event. Newspapers complain. People say I'm edgy, but I'm only edgy by newspaper standards." Pastis said he wishes he had more freedom to use saltier language is his comic. "It's like asking someone to play the piano but not play the black keys," he said. "You have to get really creative. You have to sneak it in somehow." Pastis told Lumborg that he works only about three days a week on cartoons and is more than eight months ahead of schedule. Asked why he doesn't take six months off and travel, he said it's the fear of having to go back to his old job someday that keeps him close to the drawing board. But his old job wasn’t traveling. He was a lawyer and he hated it. “For nine years, the 42-year-old UCLA School of Law grad represented insurance companies in litigation. In his spare time, he doodled simply drawn animals and submitted his ideas to syndicates. His cartoons were rejected four times, he said, until United Feature Syndicate picked it up in December 2001. Eight months later, he said, he quit practicing law. Four months after that, the comic was syndicated in more than 150 newspapers.”

QUIPS & QUOTES “The future will be better tomorrow.” —Dan Quayle “The average pencil is seven inches long, with just a half-inch eraser—in case you thought optimism was dead.” —Robert Brault “If you are going to walk on thin ice, you might as well dance.”—Anonymous “Being an optimist after you’ve got everything you want doesn’t count.”—Kin Hubbard

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted So far this

month, editorial cartooners have handled current events with their usual

scoffing and scabrous scrawlings—and thank goodness for that: someone has to

tell the truth these days. Most caught the embarrassment of our departure from

Iraq—its essential hypocrisy. Here are four that capture the moment more deftly

than some. Starting at the upper left and going clockwise, we have Frederick Deligne of Nice-Matin in Nice, France (via Cagle Cartoons), whose image resurrects GeeDubya’s monstrous faux pas of a slogan to accuse us (correctly) of a similar misrepresentation of the facts on the ground. Next, Rick Matson reminds us that our foray into nation-building has resulted in a miserable failure. Lisa Benson performs a similar feat: her visual metaphor, evoking the iconic marine flag-raising on Iwo Jima, suggests with some poignancy that the U.S.’s role in Iraq has been determined more by how much time we want to spend on the task than by how much we want to accomplish. A truth hard to take. But Steve Greenberg at the lower left deploys the best visual metaphor for a complicated emotional situation: our departure from Iraq reflects more wishful thinking, and hope, than actual achievement. Our

next visual aid deals in some lesser events of the recent past. Finally, Pat Bagley at the lower left gives us the Beck Buffoon in all his hypocritical splendor with a multi-faceted image. Beck, who is a Mormon—a religion often accused of being a cult, not a religion—is depicted accusing Obama of not being a Christian, an accusation Mormons frequently must endure. Beck, in other words, is in a glass house, from which he should not, were he a prudent person, being hurling stones (or bricks). Bagley also adds a footnote by employing George Herriman’s classic Ignatz, who, like Beck, is throwing a brick, this time, at Mitt Romney, charging him with being a cultist, not a Christian. Bagley’s principal audience for this cartoon are readers of his newspaper, the Salt Lake Tribune, many of whom are, like Bagley, Mormon. For them, the message is more potent than it is perhaps for the rest of the country: since his Mormon readers have been smeared by the same false accusations being hurled at Obama, Bagley is reminding them of both the inaccuracy of those assertions and of Beck’s basic hypocrisy. (Bagley, by the way, although raised Mormon, sometimes describes himself as a “retired Mormon.”) Our

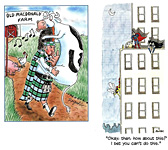

next pictures have very little political content. I include them because I

have, as yet, no department for single-panel gag cartoons, and these are too

good—too perverse—to let slip into oblivion, where far too many gag cartoons

wind up.

SPEAKING OF DR. LAURA As We Were a Nonce Ago Planet Proctor, compiled by Phil Proctor, recalled lately, amid the storm of protest about Dr. Laura’s extensive use of the N-word, that she had committed another offense against civilized behavior when she, an observant Orthodox Jew, “asserted that ‘homosexuality’ is an abomination, according to Leviticus 18.22, and cannot be condoned under any circumstances.” That, saith Proctor, brought forth a correspondence from a supposed Dr. Laura fan, James M. Kauffman, a professor emeritus (it sez here) at Virginia University, who asks her guidance on a number of troubling matters in connection with following God’s laws; I quote two of them here: I would like to sell my daughter into slavery, as sanctioned in Exodus 21:7. In this day and age, what do you think would be a fair price for her? I have a neighbor who insists on working on the Sabbath. Exodus 35:2 clearly states he should be put to death. Am I morally obligated to kill him myself or should I ask the police to do it? RCH again: I know: this has been around before. But it’s too delicious not to taste of one more time.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution In all the outrage and excoriation about the pastoral wack-job in Gainesville, Florida, whose plan to burn a pile of Qurans, Islam’s holy book, tipped the world into crisis mode, none of the journalistic gasbags discerned the most alarming aspect of the incident. The dangerous situation was created, foot in mouth, by some crazy reporter who thought the “story” as he found it on the Internet was worth reporting, giving the Rev. Terry Jones and his fruitcake notions so much publicity that it precipitated an international crisis. Worth reporting? C’mon: a small-time religionist with a congregation of less than 50 persons? How important can anything he says or does be? In the grand scheme of things, I mean. If this episode originated at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan, it might have warranted the kind of coverage this hick pistol-packin’ pastor got, but not this teensy operation in the swamps of Florida. Apart from revealing an alarming lapse of journalistic judgement by all involved (not just the criminally ignorant reporter who started it), the incident also demonstrates the power of the modern press, which, in its panic to fill air-time (or to compete with visual media) and attract viewers-readers, will do anything—anything—to achieve its objective. Which, as I’m saying, is to fill time and space and attract viewers-readers, not, as was once the case with journalism, to report the news. And while journalists everywhere pondered the potential impact of a conflagration of Qurans on the Muslim world (and our own), other gasbags, all supporters of the Grand Obstructionist Pachyderm, are permitted to spew innuendo, half-truth and distortion into the electronic ether without let or hindrance. No reporter, apparently, has the journalistic gumption to stop one of these bloviators with a simple question about their accusations and assertions. No one interrupts to say: Prove it. What’s your evidence? What actual fact are you espousing? John

“Marble-mouth” Boehner escaped the embrace of his tanning bed long enough last

month to continue his smear campaign against O’Bama, proclaiming: “Stimulus

spending sprees, permanent bailouts, federal mandates and government takeovers

have failed this nation and have failed our veterans,” he said in a speech in

his hometown Cleveland. Prove it. Where are the statistics that support this flagrant assertion? Failed our veterans? How? Boehner has also claimed repeatedly, with numerous others of the GOP, that failing to extend tax cuts for the wealthy will “kill jobs.” Not all gasbags are equally flatulent. Froma Harrop, syndicated by Creators, took on the GOP mythology last week: “Let’s cut the baloney about jobs and rich people’s taxes. If corporate profits automatically turned into jobs for the little folk, the unemployment rate would be plummeting. ... Big business balance sheets are sloshing in cash. Corporate America’s decision to stick with its current workforce [instead of hiring more people] is not for lack of dough.” Contrary to the Republican myth, “Companies don’t create jobs because they have extra money jingling in their pockets,” she goes on. “They take on new workers when they want to expand, and right now the demand’s not there to warrant that growth. ... And so how should we respond to Republican claims that restoring Clinton-era income tax rates for the wealthiest 2 percent would destroy jobs? We shouldn’t. They are irrelevant.” She goes on to remind us of the “hysterical warnings” Republicans made in the early 1990s when Bill Clinton proposed raising taxes for the richest 1 percent: “It will kill jobs, kill business, blah blah blah.” Instead, America gained a net 21 million jobs during Clinton’s two terms, compared to only 3 million during GeeDubya’s two terms. The Denver Post’s Mike Littwin, a columnist doing the job of a good reporter, notes that Baracko Bama, with an approval rating of about 45-47 percent, is one of the most popular politicians in the country. More popular than Congressmen, who barely register on the charts. O’Bama has a higher rating than Ronald Reagan had at the same time in his term as Prez. But no one in the so-called news media notices. Instead, they remark endlessly about how far Obama has fallen in popular support. What? From 52% to 47%? How big a fall is that? And all those polls we keep hearing about? Says Littwin: “I can tell you everything you need to now about the upcoming mid-term elections in two sentences. One, according to the latest NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, only 24 percent of Americans have a positive view of Republicans. Two, according to virtually every poll, these are the guys who are winning [the election we haven’t had yet].” Makes no sense, of course. But what does lately? Just so we don’t let all this fall off the edge of the planet unobserved, here’s my prediction about the November election: teabaggers are a boon for Democrats. Teabaggers running as third party candidates will split the “conservative vote,” leaving the Democrat candidates in the victors’ circle. In those contests featuring Republican candidates who emerged victorious in party primaries due to the support of teabaggers, the GOP will also lose: in a general election, their candidates will be perceived as crazies because of the vociferous support of the crazies. In short, the Democrats will win more often than they’ll lose because the party remains (somewhat) united. I realize that this prognostication is diametrically opposed to every other gasbag prediction about the election, but, as usual, they’re all wrong.

SON OF QUOTES & QUIPS “Nostalgia is the death of hope.”—Artist Mark Kennedy “Sometimes we have to look reality in the eye and deny it.”—Garrison Keillor “Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up for work.”—Artist Chuck Close “The difference between school and life? In school, you’re taught a lesson and then given a test. In life, you’re give a test that teaches you a lesson.”—Broadcaster/author Tom Bodett

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions Later this month, TwoMorrows Publishing is releasing Carmine Infantino: Penciler, Publisher, Provocateur, a biography and appreciation of “the artistic and publishing visionary whose mark on the comic book industry pushed conventional boundaries. As a penciler and cover artist,” the TwoMorrows press release continues, “he was a major force in defining the Silver Age of comics, co-creating the modern Flash and resuscitating the Batman franchise in the 1960s. As art director and publisher, he steered DC Comics through the late 1960s and 1970s, one of the most creative and fertile periods in their long history. Join historian and inker Jim Amash (Alter Ego magazine, Archie Comics) and Eric Nolen-Weathington (Modern Masters book series) as they document the life and career of Carmine Infantino, in the most candid and thorough interview this controversial living legend has ever given, lavishly illustrated with the incredible images that made him a star.”

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH Sometimes happy, sometimes blue, But I’m so glad I ran into you--- We’re all brothers, and we’re only passin’ through.

Paul Conrad, 1924-2010: An American Treasure

EDITORIAL CARTOONIST PAUL CONRAD, one of the most ferocious, powerful, controversial and honored visual provocateurs of the last fifty years, died at his home in Rancho Palos Verdes in California on Saturday, September 4, of natural causes. He was 86. And he was probably angry: anger was his professional stance, and he was a consummate professional, up to the very end, I have no doubt. He won three Pulitzer Prizes for his anger. Only four other cartoonists have equaled this feat in the 89 years the Pulitzer has been awarded for editorial cartooning—Rollin Kirby, Edmund Duffy, Herbert Block (Herblock), and Jeff MacNelly. I last saw Conrad in the flesh at a symposium on the current state of editorial cartooning held at the University of Iowa in the fall of 1999. Conrad began his address for the opening general session with a typically blunt and impolite observation: “I haven’t seen a truly powerful editorial cartoon in years,” he said. Conrad was the guest of honor at the gathering: a graduate of the University of Iowa (with a degree in art, not political science or journalism), he was on the cusp of his fiftieth year as an editorial cartoonist. Standing at the podium, characteristically stoop-shouldered, his huge head looming like the bust of an Old Testament prophet, hair thin on top but shoulder-length at the back, Conrad recalled meeting when a youth with his idol, Jay “Ding” Darling, the legendary editorial cartoonist at the Des Moines Register: “I grew up with Ding’s work,” he said; “it appeared on the roof of my house or in the bushes every morning during my childhood and high school years in Cedar Rapids, and when I got into cartooning, I took some samples down to him and asked him what he thought. He said, ‘Con, I don’t see a thing here. You’d better get into something else.’” But Con didn’t go into something else. His first cartooning job after graduating from college was at the Denver Post. Had he been a more polite—or timid or even politic—he never would have landed the job. Bill Hosokawa, who joined the Post in 1946, became an editor, and, thirty years later, wrote a history of the paper —Thunder in the Rockies—tells the story of Conrad’s quest for gainful work at a drawing board. Con had drawn some editorial cartoons for the campus paper and he’d sent samples with job applications to a number of editors around the country, including the Post’s managing editor, Ed Dooley, who politely replied that he’d be happy to have Conrad come by for an interview if he happened to be in the neighborhood. Con wasn’t in the neighborhood for several months. He and his twin brother Jim, both commercial art majors, escaped the University of Iowa in February 1950, in the dead of winter, the plunging temperatures of which they sought to evade by traveling south with their sample portfolios, visiting newspapers along the way. “By the time they reached Florida,” Hosokawa wrote, “they had just about exhausted both money and job prospects. The brothers flipped a coin and Paul won. Then he sent a telegram to the Post saying he was on his way. Dooley wired back: ‘No jobs open. Don’t come now.’” That’s when Con proved that brashness wins the day. He tore up the telegram and bought a one-way ticket to Denver with what was left of his money and Jim’s. When Paul showed up at the Post, Dooley asked him if he hadn’t received the telegram, and Paul said, “What telegram?” At the time, Palmer Hoyt, publisher of the Post, had been trying to find a replacement for an editoonist who wasn’t working out. He looked over Con’s samples and said he’d hire him for six months as a retouch artist and they’d see what happened next. Conrad recalled his apprenticeship with an airbrush at the Post : “For the first half year, I was painting brassieres on photographs of native girls that photographer Wally Taber was sending back from his African safari and removing the offensive equipment off pictures of prize bulls.” Next, after six months, he graduated to the editorial page. Conrad credited one of his editors there, Bob Lucas, with setting his feet on the right path for any editorial cartoonist: “He said, ‘Con, any cartoon you can defend, we’ll print.’ And that’s when I started reading, reading, reading, and reading, researching everything. I’ve never forgotten that.” Reading, Conrad proclaimed, is what gives an editorial cartoonist the knowledge out of which ideas and opinions are formed. And an editorial cartoon must perforce make a statement of opinion. In Conrad’s case, reading also fuels the ire essential to the passion of his work. “I wake up angry every morning,” he said, “and start reading. Then I’m furious.” Conrad left the Post in 1964 and went to the Los Angeles Times, where he plied his pen and brush thereafter, the sledge hammer of the West. There are no grays in Conrad’s cartoons. Once arriving at an opinion, he brooks no alternative view. Nor does he shrink or hesitate: he drives his point home with stark imagery, visual metaphors often of stunning inventiveness. “At his drawing board, Conrad wields a pen like a stiletto dipped in vitriol,” wrote Hosokawa. “Subtlety was not one of his strengths—and that’s actually a compliment,” said Mike Keefe, the current editorial cartoonist at the Post. “He would hit really hard, and there was no doubt where he stood on an issue.” There is nothing tentative about a Conrad cartoon. He often breaks bones while drawing blood. And he had no doubts at that Iowa symposium in October 1999 about what was wrong with editorial cartooning in the closing decades of the century. And when he uttered his opinions, he boomed: Conrad’s voice originated down deep in his tall six-foot-two body, a cavernous rumble. The younger generation, he said, is “all sensibility and no sense.” After declaiming one of these sentiments, Conrad would pause, his mouth hanging open. With his massive visage and gaping jaw, he reminded me of a lion, surveying the landscape for prey—the king of beasts, killer eyes gazing into a distance none of us can see as clearly. “You can’t teach cartooning,” he announced. You can teach drawing, but not cartooning. Too many of today’s young editorial cartoonists lack “fire in the belly,” he bellowed. “They’re going for gags, just funny one-liners.” And

they don’t read. Funny cartoons are easy to do; they require no research, only

a flimsy grasp of current events, the day’s headlines. Conrad, in contrast, was

“all about facts.”

CONRAD’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY, published in 2006, is entitled I, Con: The Autobiography of Paul Conrad, Editorial Cartoonist. Clever title. Conrad’s friends (and a few of us harmless drudges) call him “Con,” hence, “I, Con,” which, with the egotistical twitch that all autobiographies indulge, becomes “Icon,” a running glimpse of Conrad’s opinion of himself. Or maybe not. “Conrad did have a giant ego,” said Clay Bennett of the Chattanooga Times Free Press, one of today’s most deft practitioners of the craft, “—but as one of the few true titans of editorial cartooning, perhaps justifiably so,” Bennett added, continuing with an account of his first professional encounter with Conrad: “As a young cartoonist, I was warned about the scathing critiques of just two cartoonists— Paul Conrad and Bill Sanders. Both had reputations for being brutally honest. Bill rendered his verdict on my work early on, and Conrad much later in my career. I was lucky enough to make it out of both critiques with my self esteem intact, but I never approached another cartoonist with such a conflict of emotions— the longing for his approval tempered by the shear dread of his possible rejection. “We all crave approval,” Bennett went on, “but that craving is directly proportionate to the respect we have for the one passing judgment. So, as I think back on the stomach-turning, sweat-inducing anxiety I felt when I approached Paul Conrad with a sampling of my work, I realize that it wasn't inspired by fear as much as respect. So, if respect is measured by a squeamish stomach, Paul Conrad had me closer to throwing up than any cartoonist I've ever met.” The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Tony Auth was just 22 when met Conrad. “I called him up and said, ‘Mr. Conrad, sir—I’m a young would be cartoonist. Would you look at my work?’ And this booming voice says, ‘Come on down, kid.’ So I traipsed down to the L.A. Times. He looked at my drawings and said, ‘They’re not bad, kid.’ But he also said, ‘You’re loving them to death. The cartoons have to look easy. They have to look like you got really pissed off and you sat down and drew this thing.’ When I got my job in Philadelphia in 1971, I called Conrad to share my excitement. He listened in silence, and then he said: ‘Philadelphia. What was the second prize?’” Ed Stein, who drew political cartoons at the Post’s rival newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News, for over three decades, said: “As a young cartoonist learning the craft, I studied Conrad’s work endlessly. I admired both his drawings—which were bold, spare and beautifully rendered, and like the work of all true artists, distinctively original—and his voice, direct, uncompromising and savagely critical. More than that, his work stood for something. A devout Catholic, he believed in and spoke for social justice, an ethical society and honest politics, and he was a fearless supporter of those causes and devastating critic of any who stood in the way. Like all great cartoonists, he had an unerring nose for the scoundrel, the cheat, the liar, the grandstander and the crook, and he was never shy about pointing out that the emperor had no clothes. Although politically liberal, he never hesitated to lampoon Lyndon Johnson, Ted Kennedy, Jimmy Carter and other Democrats when they offended his sensibilities. In short, he was everything that a political cartoonist should be, and in his prime, no cartoonist in America was better at his craft.” I studied Conrad, too, as a neophyte cartooner—and I had the dubious benefit of studying him while he looked over my shoulder. While still in high school, I took an evening course in cartooning that he taught one night a week, Mondays. On our second meeting, we were instructed to bring samples of our work. Conrad looked at mine and said he couldn’t teach me anything: I was already accomplished enough, he said, that I’d get better on my own, just by continuing to draw. But I learned something about caricature from him: most of his “lectures” were on the blackboard where he’d draw the politicians of the day—Eisenhower, John Foster Dulles, John L. Lewis, and other miscreants of the mid-1950s. At that 1999 Iowa University conclave, I went up to him after his presentation and told him I’d taken a course from him in Denver, lo those many years ago, and that he’d told me he couldn’t teach me anything. “I was right, too,” he thundered in response. And he almost always was. Still, while I’d normally hesitate to contradict Conrad, he wasn’t just “all about facts.” He was also very much about opinion. His. And he wasn’t hesitant about pontificating. The second day of the Iowa confabulation, he shared the platform with another liberal-leaning cartoonist, Jules Feiffer. Con, as you might expect, started the proceedings by observing that he’d cartooned eleven presidents of the U.S. and that none of them, with the single exception of John Kennedy, was worth anything at all. That was too much for Feiffer, who cleared his throat, and said, “Now, Con, I’m not sure I’d go that far.” Some evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, I suspect that “icon” in the autobiography’s title does not signal egotism: instead, it shouts the satisfied delight of the artist. In another Conrad collection, Paul Conrad: Drawing the Line (1999), the late fellow editooner Doug Marlette writes about the time he and some other cartoonists were dinner guests at Conrad’s: “As we stared at Conrad’s Pulitzer Prizes [three] on the wall and the Time magazine covers he had drawn, our host returned with our beverages, interrupting our oohs and aahs with his booming circus-ringmaster voice: ‘Yeah,’ he said, agreeing with our assessment, ‘Isn’t that great?’ No false modesty. No ‘Aw, shucks.’ Simple, uninhibited delight in what he had wrought. I remember telling a colleague afterwards, ‘That is the key to Conrad’s genius, and that is the key to greatness—authentic, unapologetic delight in oneself and one’s art.’ Conrad was showing us the secret of Picasso and Matisse, of Rilke and Joyce, of Dickens and Twain, the secret of every great artist—to be filled with awe and delight and wonder at the thoughts and images that flow from the darkest recesses and deepest cellars of your own soul.” My own acquaintance with Conrad, brief though it was, confirms Marlette’s judgement. Conrad delighted in his work—and he was thoroughly unabashed about it, and about what makes good editorial cartooning. A couple pages after Marlette’s remarks, Conrad lays in, denigrating the “illustrative” character of some political cartooning: “Illustrating in an editorial cartoon means to me that the person really doesn’t know, doesn’t have the background to say what he is saying. He or she only illustrates but doesn’t take a position—doesn’t say, ‘This is a crock,’ or ‘This is right on.’ You have to take a position. That’s what the whole thing is about,” he exclaimed. Then he continued: “There was a six-paneled cartoon in the Los Angeles Times recently. I have no idea what it was about, but I did start counting the words. There were 235. Can you imagine that? I mean, why doesn’t the man get into editorial writing? The thing was only 14 words shorter than Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. And I know what Lincoln was talking about!” About his autobiography, which reads like the transcription of an audio tape, Con said: “I guess there are what some other people might call ‘insights’ in here. I call ’em facts. I’m all about facts and I’m all about taking a stand once you know the facts. That’s what I’ve been doing for the last fifty-plus years.”

AT THE CALLOW AGE OF EIGHTEEN, having successfully completed high school, Con and his brother skipped graduation ceremonies and ran off to Alaska, where they found construction jobs, helping to build the Alaska-Canadian Highway. Con drove a truck. For recreation, Conrad tells us in I, Con, he played pool in a dive across the street from a whorehouse in Valdez (which is just on the other side of the Matanukska Glacier from landmark Wasilla), but he also wanted to play piano and the only piano in town was in that whorehouse. So Con traipsed across the street and introduced himself to Red, who, when he told her he was looking for a piano to play, invited him in, and he sat down and started to play. “Oh, God,” Conrad wrote, “—she was just thrilled. So when one of these clowns would go up the stairs with one of the floozies, I’d just drop what I was playing and do ‘A pretty girl is like a melody.’ As soon as the door slammed, I’d be back to whatever I was playing. I was eighteen years old, but I never went upstairs. Never did. Oh, I wouldn’t have touched those women with a ten-foot pole! I mean it. It didn’t happen. Whenever the Columbia or another vessel would come into port, there’d be a party. Red would tell me, she’d say: ‘Come over with your brother, get my piano and take it into this large tent.’ Then she’d take the red light off and put a white light on. Then she’d charge a dollar more.” Conrad’s brother died in 2006. Said Con: “Unless you are a twin, you can never understand how I felt when he passed.” They were identical, except that Jim had a gold front tooth. After serving in the Pacific during WWII (Conrad drove a truck again, this time with the Corps of Engineers during the invasions of Guam and Okinawa), Con and his brother enrolled in Iowa University on the G.I. Bill, and while matriculating, Conrad drew editorial cartoons for the campus paper. "I wasn't very good," Conrad recalled. "But Charlie [Carroll, who edited the paper,] took me over to see that first cartoon come off the press, a Franklin flatbed. And there it was, my cartoon! God, it was exciting! Just marvelous!" Conrad’s next professional stop, as we’ve seen, was the Denver Post. There he met and married another Post staffer, a new society reporter named Kay King. She briefly dated Jim, reports James Rainey at the Los Angeles Times, “but Jim persuaded Paul and Kay that the two of them were a match.” It was a match both personally and professionally: Kay was engaged in Con’s work as well as his life. She was, Rainey wrote, Con’s “enduring advocate, editor and critic. Many others would offer advice or suggestions, but the cartoonist once said that only Kay Conrad and Edwin O. Guthman, the Times’ national editor, could persuade him to kill an idea he had been set on.” Their marriage outlasted Con’s career; and she and their four children survive. In early 1964, the Los Angeles Times invited Con out for an interview. Otis Chandler, innovative and energetic, the ownership family’s more liberal black sheep, took control as publisher in 1960 and with the connivance of editor Nick Williams, set out to rescue the paper and its reputation by hiring top talent. They were determined to bring Conrad to Los Angeles, and they “impressed him with their resolve,” said Rainey. Conrad was leery about the conservative bent of the paper. "The one thing I said," Conrad recalled, "was, 'Nobody tells me what to draw.'" They agreed and offered him $100 more a week than the Post was paying him, plus favorable syndication terms with the Times Mirror Syndicate. The Post, which had a policy against engaging in bidding wars, was helpless to prevent his departure. In May, four months after he left, the Pulitzers gave Conrad the editorial cartooning prize for 1963. It was the first Pulitzer the Post had ever seen. Conrad won two more while at the L.A. Times, in 1971 and 1984. At

the Times, as at the Post, Con had all the freedom an editorial

cartoonist could want, and Con wanted a lot. "I decide who's right and

who's wrong, and go from there," he told Writer's Digest. The cartoonist explained: "Nobody can speak for the fetus. So, in that sense, I think the liberal stance should be against abortion." But by the late 1980s, his position had reversed. One day, driving his car and listening to the radio, he heard Justice William Brennan, a Catholic, talking about a woman having the right to control her body, not the government. “He changed my views about abortion,” Conrad wrote, “—in an instant. I really couldn’t believe it because his arguments were so clear: ‘I represent the Constitution, not the Catholic Church.’ ... That changed me.” As a Catholic, Conrad was against abortion, he says—personally, so to speak, but not as a matter of the law of the land. “Roe vs. Wade has to stay,” he said. Without it, “women don’t have a prayer. I think it’s up to the woman herself. ... A woman’s right to choose is more important than my own feelings about abortion.” When the U.S. Supreme Court allowed states to have more say in abortions, Conrad drew a naked woman with a sign, "State Government Property," posted over her womb. In I, Con, Conrad also tells about being sued by Bill Mauldin because he used facsimiles of Willie and Joe in a cartoon. “Other cartoonists eventually talked him out of it,” Conrad says. “Willie and Joe had become public domain.” Conrad was sued with some regularity. Los Angeles mayor Sam Yorty sued him in 1968 for libel; and so did Union Oil Company president Fred L. Hartley in 1974. Neither won. “Conrad loved making trouble,” Rainey wrote. “His righteous indignation was guided by a modest Midwestern upbringing, an abiding Catholic faith and what one chronicler called a ‘fanatic heart.’" Rainey goes on to quote “another elder statesman of the cartooning trade, Pat Oliphant,” who once said Conrad exhibited “the grandest example of consistently A-grade, blue-ribbon, USDA-prime righteous anger that I can ever remember seeing in a cartoonist's work in the 50-plus years that I have been doing this sort of thing." By the early 1990s, Conrad began to feel less comfortable at the Times. Otis Chandler, one of Con’s great supporters, had stepped down as publisher in 1980; he remained as editor-in-chief and chairman of the Times Mirror Company, but he was forced out of both positions a few years later. Old friendly editors left the paper, and the new ones moved Con’s cartoon from the Opinion page to Op-Ed, where papers traditionally consign divergent views. Some saw the move as a slap at Conrad, and he harbored the same idea but thought it an improvement: At the end of 1985's Drawn and Quartered collection, Conrad is interviewed by Richard C. Bergholz, who asks the cartoonist how he felt about being moved to the Op-Ed page. Conrad said: “Everybody here denies that I was intentionally moved because of any particular cartoon or cartoons. I still think I was. I don’t go to editorial conferences, but I am concerned about what positions the newspaper takes on issues. I think the move to Op-Ed was the best thing that ever happened because now there’s none of this nonsense about who speaks for the Times. And with the space created on the editorial page [where his cartoon used to appear], we’re getting more and better letters to the editor that we can publish. I think that’s to everyone’s advantage.” But Conrad felt the culture of the paper shifting. The culture of newspaper journalism was shifting all across the land: increasingly, newspapers were owned by stockholders who demanded profits in return for their investments, and increasingly, editors were persuaded that controversy interfered with making profits. They became passionate about avoiding controversy. And Conrad was all about controversy, provoking ire and indignation in order to make readers think about the chicanery of their political leadership. So his editors were quite so friendly as they had been. When the Times offered buyouts to the entire staff in January 1993, Con took his. Until then, he’d produced a cartoon every day for five days a week—and two on Friday (one of Sunday’s paper, the other for Monday’s)—for over 40 years. Every day. Never missing a deadline. He had something to say every day. He was, apparently, never at a loss for an idea that needed a visual metaphor for maximum impact. He didn’t exactly retire: he gave up his office at the paper, but he continued to draw four cartoons a week for syndication. And he kept that up until quite recently when he became too ill to work. Conrad also pursued other artistic endeavors—painting and sculpting in bronze (political figures, mostly—including Nixon making his famous “V” with his arms raised)—and he continued to participate in community activities.

AFTER THE FIRST EULOGISTIC WAVE of obituaries washed across the nation, Bill Boyarsky, author of a history of the Los Angeles Times, was compelled to add a footnote at laobserved.com. Because it completes the Conrad story in a way most of my other sources haven’t, I’m including it all herewith: In the Los Angeles Times obituary on Paul Conrad, editor Russ Stanton said, "we have missed him since the day he retired." But it wasn't quite like that. Conrad had been angry at the paper since his 1993 retirement—at the unforgivable way he had been treated and, most important, at the direction the paper had taken. First, a few words about the great cartoonist and what he meant to the Times staff. The workers on the newsroom floor admired his fierce independence, courage and idealism. We liked the way that our publishers, first Otis Chandler and then Tom Johnson, and editor Bill Thomas stood up against those who complained about Conrad's savage satirizing of the big shots' failings. We felt that if they stood behind Conrad and his excellent work, they would stand behind us and our journalism. And they did. I lived through that era and the downhill slide that followed it. Then I relived it when I wrote my book Inventing L.A.: The Chandlers and Their Times. Researching the book, I learned a lot about Conrad, how he came to the Times and of the circumstances that led to his departure and to what amounted to exile. After taking over as publisher in 1960, Chandler decided to hire Conrad, the liberal cartoonist for the Denver Post. Conrad would become the most visible symbol of the Otis Chandler Times, a daily signal that the paper was no longer a right wing Republican rag. Some lovers of the old Times hated his cartoons, among them Richard M. Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Nancy Reagan, Cardinal Roger Mahony and many powerful business tycoons. While he attacked those people with anger—and a satiric skill that drove them crazy—Conrad also was a man of considerable charm and humor capable of empathy with those who disagreed with him. At lunchtime, he ate in the Picasso Room, the executive dining room, sitting with the conservative Times business executives rather than the editors. They argued through lunch in a good-natured way, and it was obvious that the executives took great pleasure in his company. Conrad recalled a plane flight to Los Angeles with Norman Chandler, Otis Chandler's father, and publisher of the paper in its conservative days. "We were the only ones in first class," Conrad recalled. "I thought, what do I do now? Pretty soon I get, `Hey Paul, come on up. We can chat—.’ We talked kind of all the way, I with my vodka, he with his gin. He was just marvelous. Not putting me down but wondering where in a particular situation—why I'd go the way I went (in a cartoon). So I'd explain it to him. He just flat out didn't understand liberals. I don't blame him; there are a whole lot of conservatives who don't understand liberals." Otis Chandler steadfastly protected Conrad from criticisms from conservative Chandler family members and Times Mirror executives, who didn't feel the camaraderie that Conrad shared with his Times business-side luncheon companions. Tom Johnson said one person enraged by Conrad was Dr. Franklin Murphy, the chairman of Times Mirror: "He would come down to Otis's office with the tear sheet of Conrad's cartoon in hand. But to the best of my knowledge, Otis never, never told Paul Conrad he should back off." After Otis Chandler retired as publisher in 1980 and moved into the leadership of Times Mirror, Conrad's troubles began. In 1986, the conservative Chandler family members forced Otis out as editor-in-chief and chairman of Times Mirror. Three years later, Johnson, who had succeeded him as publisher, was ordered to fire the editor of the editorial pages, Tony Day, a moderate who was liberal on social issues and a steadfast Conrad supporter. Johnson refused and was fired. That year, Bill Thomas, who stood up for Conrad, retired as editor. The editorial page became bland and more conservative. Conrad, the opposite of bland and conservative, was out of place and out of highly placed friends and supporters. In 1993, Conrad accepted a buyout and was replaced by a conservative cartoonist, Michael Ramirez. Conrad and readers were told that [his syndicated cartoon] would continue to appear in the Times. But as it turned out, he ran only sporadically. The impact of his daily cartoons was gone. He was just another of the syndicated cartoonists the paper occasionally used. Readers didn't know when he would appear, or where on the pages his cartoons would run. Angry, he often called the editors, demanding to know why his cartoons weren't being run. He couldn't get straight answers. America's greatest political cartoonist was being treated as if he were a rookie freelancer. His last cartoon, according to the Times database, appeared in 2005. That same year, Robert Scheer, the popular liberal columnist, was dumped from the Op-Ed page. By then, the paper had long since turned away from the direction set by Otis Chandler. Gone was his commitment to a staff, including a crusading cartoonist, encouraged to pursue their craft and their obligation to society without interference, as long as they did their job well. "Take a look at the paper, read some editorials that we've been working on and some we've printed," Chandler told Conrad as he persuaded him to come to the Times. Conrad did. "It was marvelous, marvelous stuff," he said. That began a great partnership that ended long before Conrad's death. RCH: The Times editors may have “missed” Conrad after he “retired,” but they were glad he was missing.

THE DES MOINES REGISTER’S “DING” may have been the idol of Conrad’s youth, but he wrote in his autobiography that Herblock had the greatest influence on him. And the influence is apparent in Con’s earliest cartooning at the Post. In those days, Con did spot illustrations for the paper’s letter column and a couple gag cartoons that also sometimes dressed up the editorial page. Evidently, Hoyt thought a staff cartoonist with only a single editorial cartoon to do every day didn’t have enough to keep him sufficiently busy. (For samples of his work at this stage, re-visit Opus 219, which reviews I, Con and includes a vast assortment of the cartoonist’s work from all stages of his career.) In the latter part of his career, Conrad often abandoned the editorial cartoonist’s usual weapon, caricature, in favor of depicting some inanimate object and giving it potent symbolic value. Sometimes I think he went a bit overboard in this maneuver—he seemed to do it more and more as his ability to caricature deteriorated over the years—but his cartoons still have the uncompromising force of a sledge hammer, as does Conrad’s prose narrative. In neither does he pull any punches. His straight talk, in words and in pictures, is well-represented in his autobiography. “He believed the perfect cartoon had little or no text,” said Rainey. “To represent President Nixon's self-inflicted wound from his Oval Office taping system: an unraveled audiotape, formed into a hangman's noose. Depicting hawkish U.S. foreign policy: a beaming Reagan, sitting waist-deep in a bathtub filled with toy warships.” Rainey continued: “An exceptional single-mindedness made many of Conrad's cartoons jump off the page: Nixon, tied down like the giant, Gulliver, by reel after reel of his secret Oval Office audiotapes. Nancy Reagan's pricey new White House china captures the reflection of a stooped homeless woman, picking through the trash. President Carter ‘lusts after’ a voluptuous nude Statue of Liberty. A Northern Californian, opposed to the massive Peripheral Canal water project, urinates on a map of Southern California.” Nixon and Reagan, two California politicians who rose to occupy the White House, were Conrad’s favorite foils. “Nixon was Number One,” Conrad said. “But Reagan was a close second.”

In the New York Times obituary, Robert D. McFadden describes some of Con’s assaults on the nefarious California alumni: In 1968, Conrad drew California’s Governor Reagan on his knees retrieving papers marked "law and order," "patriotism," and "individual liberty," from under the feet of former Governor George Wallace of Alabama, a presidential candidate that year. "Excuse me, Mr. Wallace," he says, "you're stepping on my lines." As president, Mr. Reagan became Napoleon, "The War Powers Actor." Conrad also took aim at Democrats, McFadden points out. President Lyndon Johnson and Vice President Hubert Humphrey were cowboys riding a Dr. Strangelove bomb down to Vietnam in 1968. Years later, when Robert McNamara expressed regrets over the war, Conrad drew the former defense secretary at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington (beside the names of 58,000 dead) saying, "Sorry about that." In the 1976 and 1980 presidential campaigns, McFadden remembers, Conrad rendered Jimmy Carter with a toothy grin of vacuity. He portrayed yuppies as rich brats, reporters as backward donkey riders and himself as a scruffy artist—a lanky drudge in shirt sleeves with a jutting chin, horn-rimmed glasses and thinning hair. Missing

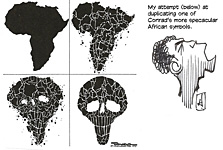

from the Conrad reprint compilations, though, is what I think may have been one

of his earliest and most powerful symbolic efforts—the head, in profile, of an

African who is screaming in agony, the outline of the picture evoking the map

of Africa. Here with some other of his African efforts, I’ve made a stab myself

in the direction of showing how he did it. Another cartoon missing in all the published collections is one he did during the 1980 hostage crisis in Iran. He depicted the famed Iwo Jima marines raising their usual American flag, but planting its staff in the rectum of a sprawling Ayatollah Khomeini. As soon as this gem was put into Conrad’s syndicate’s distribution system, it was withdrawn. Or so the story goes. I may be misremembering: without the physical evidence in hand, I could be mistakenly assigning this cartoon to Conrad; maybe it was somebody else. But if it was, it still could have been Conrad. “The

Watergate scandal created a perfect convergence,” Rainey wrote, “—Richard

Nixon's scheming and skullduggery pitted against Conrad's righteous indignation

and furious craft.” On the day after the illegal break-in, he drew Nixon

disguised as a phone company worker boring a hole in the wall at the Democratic

National Committee headquarters; with that, he nailed the president to the

crime at the very onset of the scandal, as cartoonist Steve Greenberg acutely

notes. Rainey concluded: “Others saw Nixon's 1994 death as occasion for absolution. Not Conrad. He drew the 37th president's grave with the words: ‘Here lies Richard Nixon.’" It made you think twice about the alternative meanings of the word “lies.” Of all of his laurels and other achievements in a longer career than most, Conrad was proudest of the most perverse of them. When he found out that he had made it to Nixon’s “enemies list,” he was delighted. He saw it as a signal distinction, a triumphant honor. Nothing, it seems, could have pleased him more, and he often bragged about it. And he relished the accolade even more in 1977. That year, Nixon’s alma mater, Whittier College in California, compounded Conrad’s delight: it named the cartoonist its Richard M. Nixon Scholar for the school year. (When he heard of the appointment, Conrad first thought it was a joke; later, occupying the Nixon Chair, he relished having the last laugh.)

HERE IS A SAMPLING of what a few of Conrad’s admirers said about him, through the years and at the time of his death: Author, essayist and cartooning fan Pete Hamill called Conrad "a voice. And the voice is his alone: alternately savage, compassionate, brutal and ironic." Writing the Conrad obit for Time, Tony Auth told a story to make his point: “A group of us cartoonists were once invited to have lunch with President George H.W. Bush. Somehow the subject of beach balls came up, and from the far end of the table came Paul Conrad’s voice: ‘Speaking of beach balls, Mrs. President, how’s Dan Quayle doing?’ Conrad was absolutely fearless—a volcano of opinion and assertion.” Politico’s editoonist Matt Wuerker said: “Conrad was a giant, with giant talents ... and a giant ego, and combined, these things let him take cartooning to truly great heights. He set such a fine example of what sharp, serious, passionate cartooning can attain. The power and impact of his cartoons has been matched by only a few in the field. Political cartooning lost a real lion today.” While many other cartoonists angled for whimsy or the easy one-off, Conrad "specialized in hair shirts and jeremiads and harpoons to the heart," former Times Editor Shelby Coffey III once wrote. “Otis [Chandler] and I would sometimes kind of talk, kid around, about how much trouble Conrad was," said William Thomas, who headed the Times’ editorial operations from 1971 to 1989. "We all caught hell for things, but you couldn't help but appreciate the artistry that he had, the intellect behind it and the punch that it packed." “The cartoonist, loud and often profane in person, viewed himself as a champion of the common man and relished combat with those he saw as protectors of the rich and privileged,” wrote James Rainey in the Times obit. Loyal opposition is vital to the democratic form of government: democracy cannot exist without a chorus of critics to help plot its course. And Conrad embodied that opposition. But he wasn’t just a liberal: he was a moralist. He was for what was right and against what was wrong, morally speaking. He championed human and civil rights, but it wasn’t only ordinary citizens who he was protecting: it was democracy itself. His crusade was against abuse of power in all its manifestations. Defender of the faith in democracy, Conrad was an American treasure in a distinctly American way. “Conrad is ... more than a legend in cartooning and an institution in American journalism," said the late Doug Marlette. "He is a force of nature. ... You measure Conrad on the Richter scale." And now, Conrad is gone—the earthquake subsided, the steady rumble of the booming voice stilled, the jubilant sarcasm silent, the sharply pointed pen laid aside, the bristles of the brush dry and stiff. But ever after, Paul Conrad will be revered and remembered with other furious towering giants of the craft’s storied past—Thomas Nast, Joseph Keppler, Homer Davenport, Daniel Fitzpatrick, Edmund Duffy, Herblock, and Bill Mauldin—who made us think with their righteous anger and outrageous pictures.

***** For a gallery of Conrad’s work, go to Opus 219 and the review of I, Con. For an insightful portrait of the man as well as the cartoonist, see the DVD of the PBS special, “Paul Conrad: Drawing Fire.” You can find it at Amazon.com, both new and used.

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY The Thing of It Is ... At the Augusta Chronicle, the editorial staff reported on Obama’s Oval Office speech about the departure of American “combat troops” from Iraq: “Ambivalence shone on his face and wove through his words as President Obama marked the end of the Iraq War. ... So ambiguous is the end of this war that it's not even being called the end of the war; it's the end of ‘combat operations.’ ... No doubt mindful that he's heralding an achievement he opposed at every turn as a senator and candidate, and that his far-left base was watching him closely, Obama's famous soaring rhetoric departed him Tuesday night.” Obama’s out-of-Iraq speech didn’t have any rhetorical ruffles or flourishes because he knew he’d have to lie in the speech, and he doesn’t like lying. Among the lies disguised as half-truths, this, about the “security” situation in Iraq: “Iraqi forces have moved into the land with considerable skill and commitment to their fellow citizens. Even as Iraq continues to suffer terrorist attacks, security incidents have been near the lowest on record since the war began.” But no one in the country is safe. And this, about the “democratic” government that the election five months ago couldn’t seem to elect: “A caretaker administration is in place as Iraqis form a government based on the results of that election.” But the whopper was this: “We have met our responsibility.” We wrecked the country, and we’re leaving before it can govern itself or provide security for its citizens. What sort of irresponsible behavior is that? But the U.S., never a nation for prolonged wars of any sort, is eager to escape the quagmire of Iraq, and Obama knows it, so he constructed a lackluster speech by stringing together exaggerations and oversimplifications, masked by a single undeniable truth: “The Americans who have served in Iraq completed every mission they were given.” Sometimes not so well (think of the billions of dollars spent that we can’t account for, the electricity that is available for fewer hours a day now than before our “rescue mission,” Iraqi civilians run down by marauding Blackwater juggernauts); sometimes as well as any reasonable person could expect. But still, Obama had to lie our way out. Okay: we lied to get into Iraq, so it’s fitting that we lie to get out of Iraq.

***** The electoral strategy of the Gigantic Obstructionist Pachyderm is based entirely upon an antique axiom in politics: just as the party in power takes the credit for good things, it must take the blame for bad things. And so the GOP has deliberately attempted to frustrate every legislative initiative by Obama and the Democrats—to delay or deny enactment. As a result, whatever could be fixed by legislation isn’t fixed; it’s still broken or otherwise nonfunctional. Ergo, the Obama administration will ipso facto take the blame for this tsunami of bad stuff, of unfixed economy, of unemployment, etc., and the GOP will win by default (not because it has any idea of what to do to fix anything). The question that should, at this point, arise is: what sort of patriots are these GOP jokers? Are they fellow citizens? (They certainly have no regard or compassion for their fellow citizens.) Hence, are they fit to govern at all? Are they even Americans?

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |