|

|

|

Opus 159: Opus 159 (April

17, 2005). A long appreciation of Dale Messick is our featured event

this time, plus a review of the graphic novel The

Irregulars. A rundown of this installment's contents, in order,

by department: Nous R Us -Art

Spiegelman makes Time's most

influential list, Signe Wilkinson's Red Lake comment raises Indian ire,

Scott Stantis' Prickly City gets

yanked in Seattle, the psy-ops plan for winning hearts in the Mid-East,

Steve Geppi says he's a changed man (or a misunderstood one); Civilization's Last Outpost -More choice is not necessarily better,

how the Polish communists reacted to the election of John Paul II in

1978; Comic Strip Watch -Speed

Bump's caption contest garners 3,000 entries, Doonesbury proceeds to go to Fisher House, Get Fuzzy shoots beaver;

Editoonery -Nick Anderson wins Pulitzer's $10,000, R.J. Matson gets Post-Dispatch chair; Sin City reviews; Too Many Graphic Novels?

Dale Messick, and the review of The

Irregulars. Then a couple Bushwhacks and we're done. Finally, our

usual Solicitous Rejoinder: Remember, when you get to the Members' Section,

the useful "Bathroom Button" (also called the "print

friendly version") of this installment that can be pushed for a

copy that can be read later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without

further adieu- NOUS R US Two cartooners made

Time magazine's annual list of the world's

most influential people (April 18): Japan's Hayao Miyazaki and our own Art

Spiegelman. Miyazaki was extolled by no less a critical intelligence

than Stan Lee, who said the anime master "has

consistently pushed the creative envelope" and has "taken

the art of anime and brought it to new heights through an inimitable

vision and sense of storytelling." Spiegelman's rave writer is

Marjane Satrapi, who says the Maus man deserves the honor because

"he is the reference for any cartoonist"; for her anyhow,

"-he showed me that comics can be more than superhero stories."

But she spends the rest of the page in a comics and prose tribute to

the man who, during her visit with him, smoked three times more cigarettes

than she, another famous smoker, did: "He's a better man than even

I had expected," she concludes smugly. Spiegelman is one of the

few people in the 71-page section to get a full page to himself, joining

Barack Obama, Martha Stewart, Sony's Howard Stringer, SpacShipOne's

Burt Rutan, and Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko. Condoleezza Rice

and Jamie Foxx are the only ones to get more than a single full page:

they each got two, including giant photos. By comparison, most of the

100 run to half or third pages: GeeDubya got only a third page, Nelson

Mandela, half-a-page. While it's nice to see cartooning get all this dignifying

recognition, such accolade line-ups always make me wonder. Why Spiegelman

and not, say, Garry Trudeau? Trudeau is in the public square more often

with opinions that are, arguably, more powerfully put than Spiegelman's

occasional outbursts. The objective in compiling the list was, apparently,

to pick "men and women whose power, talent or moral example is

transforming the world." Rice, we may agree, qualifies; ditto George

W. ("Whopper") Bush and numerous others of the political persuasion

listed herein. But for the cartoonist, why not Aaron McGruder? He upsets

at least as many people every week as Trudeau-and many many times the

number outraged by Spiegelman, who, as I say, doesn't surface that often.

I'm afraid I suspect that Spiegelman, whose talent and influence are

undeniable-certainly by me-got the nod because they somehow felt they

needed a cartoonist on the list what with the surge of graphic novels.

Who to pick? Spiegelman is most often on the tips of people's tongues

in New York's media power centers whenever they talk about the new cultural

status of cartooning, or "comics," so why not Spiegelman?

Who else qualifies, given the presumed criterion here? Enough quibbling.

I don't seriously question the wisdom of the listers' choice: Spiegelman

is, indeed, an inspirational force in cartooning (not to mention being

brilliantly analytical and deeply knowledgeable about the history of

the medium). I'm nattering on here merely to show how readily lists

of this sort can be criticized-and invariably are. And in the last analysis,

apart from the Bushes and Rices and Yushchenkos, how can you, really,

make up any kind of genuinely meaningful list? Dan Brown made it to

this list, for instance- The DaVinci Code guy?-but not for his writing

ability; his novel, while tantalizingly constructed, was quite badly

written. Very little description, for instance, no characterization.

He's on the list, though, for writing a mystery story that "kept

the publishing industry afloat." Still, lists are a fun game, kimo

sabe. I love 'em. About 75 Indians (that's "Native Americans" but

I'm quoting from the Minneapolis

Star Tribune's Bob Von Sternberg) gathered outside the office of

the Duluth News Tribune on March 31 to protest a cartoon

the paper published about the recent Red Lake school killings. The cartoon,

a syndicated effort from Pulitzer-winning Signe Wilkinson of the Philadelphia

News, showed a man with a headband and a ponytail holding an "Indian

Tracking Guide" as he follows a path strewn with guns, skulls,

swastikas and a picture of Adolf Hitler. The man says, "I'm not

recognizing these signs." The Red Lake readers and their sympathizers

thought the portrayal of Indian culture was insensitive and stereotypical.

Wilkinson intended no offense: her point was that parents need to learn

to "read" (recognize) different signs these days in order

to understand where today's teenagers are coming from and thereby to

prevent such wholesale slaughter as 16-year-old Jeff Weise conducted.

But even for the American Indian, who has a reputation for "reading

sign," the task of self-education is daunting. This would be just

another instance of newspaper readers mis-reading an editorial cartoon

except for what the leader of the protest, Mike Sayers, said: "If

one of us did something similar, we'd be fired," he said. "We

thought [the newspaper] should ask for the resignation [of the person

responsible for the cartoon being printed]. It was really disturbing

that someone on the staff found

humor in it and put it in the paper" (my italics). Sayers has

helped identify the problem in virtually all such incidents. In most

citizens' minds, cartoons equate to comedy. They're supposed to be funny.

Editorial cartoons are cartoons and, so the reasoning runs, they are

therefore funny-to someone, somewhere. Most newspaper readers, I daresay,

think that editorial cartoons are supposed to be funny. And these readers

are easily outraged when an editorial cartoonist tries to make a point

that may be mildly amusing but is heavily freighted with seriously thought-provoking,

even disturbing, imagery. They think the cartoonist is ridiculing something,

making fun of something. And it's usually someone or something that

the offended readers don't think we should be laughing about. Like Native

American culture, especially when an entire community is in grief-stricken

shock as it is at Red Lake. Elsewhere, on another occasion (Washington Post's online cartoonist interview series), Wilkinson commented on the dearth of female

political cartoonists, saying, "Perhaps one reason women don't

go into this biz is that you need really thick skin." Wilkinson

is one of the profession's dryest wits, and later in the interview,

when asked what it was like to get the Pulitzer, she said: "It's

like having Ed MacMahon coming to your door with the publisher's sweepstakes.

YOU HAVE WON!" But then came the self-deprecating closer: "There

are so few cartoonists and so many prizes, if you stick around long

enough, you're sure to get one. Cartooning is so well-regarded in the

[journalism] profession that it's ranked right around the Pulitzer prize

for hair coloring." Growing up "on the Mad magazine sensibility-particularly Sergio Aragones," Wilkinson, while

valuing the function of the political cartoon, is not persuaded that

the genre can change the course of Western civilization. "It's

been my experience," she said, "that people don't pick up

a cartoon, smack themselves on the forehead, and say, 'Well, now I'm

going to vote the way this cartoon says I should.' Mostly, I think cartoons

reassure people who already agree with them that they aren't alone." In the New York Times,

meanwhile, Maureen Dowd speculated

about why there are so few women shaping the nation's opinions. "As

a female columnist," she wrote, "I can hazard a guess: Men

are utterly unnerved by opinionated women." Opinionated men are

clever and daring; opinionated women are castrating shrews. "Few

women, sadly, are willing to put up with these hostile reactions. ...

There are scores of brilliant, talented women out there who could join

the ranks of the nation's leading thinkers and pundits. First, though,

men will have to stop calling every women with strong opinions a bitch."

Or, perhaps, women will have to get used to being called whatever female

opinion mongers are called. If it's going to work both ways, it's gotta

work both ways. Meanwhile, the Washington

Post National Weekly reports (March 21-27) that laughter improves

health and lessens the chances of heart attacks. A study recently demonstrated

that laughter induced blood vessels to dilate, which improves blood

flow. A good thing, considering that heart attacks can be brought on

by constricted blood vessels that impede the flow of blood. According to David Astor at Editor & Publisher, the Seattle

Times dropped several of Scott

Stantis' Prickly City strips

recently during a sequence that alluded to the Terri Schiavo tragedy.

Carmen's favorite team in the NCAA tournament lost, so her "liberal"

buddy, Winslow the Coyote, says, "I know a way I can end your agony"

and takes away her food. In a subsequent strip, Winslow goes on to say,

"I'm doing it to stop your suffering, Carmen. Besides, suicide

and euthanasia are cool now. Hunter Thompson. Million Dollar Baby. It's

all the rage." I feel compelled, at this rhetorically convenient

juncture, to point out that if the "million dollar baby" had

asked her hospital attendants to pull the plug on her life support system,

they would have had to do it: that's the law. The patient can always

decline treatment or terminate it. But the makers of the movie wanted

an emotional crisis, so they, in effect, manufactured one where one

didn't need to exist. But I divaricate. Stantis said he received "dozens"

of critical e-mails on the sequence, many saying "how dare he make

light" of the Schiavo case. His syndicate, Universal Press, was

not aware of any other papers pulling the sequence. And even at the

Times, which ran the first strips in the

sequence before yanking the rest, there was no "huge outcry";

just "a handful of complaints, well within the range of what we

receive fairly often about Prickly

City," said Cynthia Nash, director of content development at

the paper. So the paper over-reacted by imagining a response that never

materialized. Typical timorous editing. And, once again, "cartoon"

means "funny," and the Schiavo situation wasn't funny. Stantis,

who realizes newspapers have a right to pull strips they don't like,

finds that behavior a little strange when considering that social and

political commentary reputedly bring highly prized but hard to reach

younger readers to newspapers. Stantis, who doubles as editorial cartoonist

at the Birmingham News (Alabama),

believes commentary is as legitimate on the comics page as it is on

the editorial page. "The comics section is the only part of the

paper we can't talk about Terri Schiavo?" he asked, rhetorically.

FOOTNIT: Stantis has launched a weekly podcast based upon the

strip, David Astor reports. Accessible via PricklyCity.com

(or http://images.ucomics.com/images/podcasts/pricklycity/pricklypodcast040205.mp3

) and lasting 5-10 minutes, the podcasts are "a lot like an audio

blog," Stantis explained. "To my knowledge, no other syndicated

daily comic strip artist has ever attempted this. It allows me to flesh

out the strip and explain the ideas behind it more fully. I'm keeping

it light and funny. I'll talk about either the strip that just appeared

or what's likely to come next and maybe get into why the characters

said or reacted the way they did." The U.S. Army hopes to win the hearts of young people in

the Mid-East by producing a comic book and is inviting applications

for the job. Special Operations Command is concocting the comic at Fort

Bragg, home to the army's 4th Psychological Operations Group

(the storied "psy-op warriors"), whose weapons, according

to BBC News, include radio transmitters, loudspeakers, and leaflets.

The initial character and plot development has already been completed

based upon the activities of security forces as envisioned for the near

future. A successful applicant to continue the work, according to the

advertisement, should have experience of law enforcement and small unit

military operations along with a knowledge of Arab language and cultures.

Walking on water is apparently not required; nor, it seems, is drawing

ability. "In order to achieve long-term peace and stability in

the Middle East," the ad reads, "the youth need to be reached."

The army's comic book will be in competition with a new Egyptian publishing

venture that has created a clutch of what it bills as the first Arab

superheroes: Zein aka the Last Pharaoh; Rakan, a hairy medieval warrior

in Mesopotamia; Jalila, a brainy Levantine scientist and fighter for

justice; and Aya, a North African "vixen who roams the region on

her supercharged motorbike confronting crime wherever it rears its ugly

head." The objective here is "to fill the cultural gap created

over the years by providing essentially Arab role models ... to become

a source of pride to our young generations." Ahh, success: the

humble comic book, until recently the flotsam in the cultural sea, is

now a weapon of mass instruction. Speaking of the Mid-East, freedom of expression is again

at risk in Turkey, where the prime minister, Tayyip Erdogan, once a

champion of free speech, is suing a satirical magazine, Penguen,

for publishing a cartoon that caricatures him as a frog, camel,

monkey, snake, duck and elephant. Helena Smith in the Guardian says Erdogan is incensed and demands sixteen thousand pounds

in compensation. This is the fourth time Erdogan has taken the media

to court for poking fun at him. The cartoon at issue was printed on

the cover of the magazine in defiance after Erdogan took legal action

against one of Turkey's most prominent political cartoonists. Said Penguen's editor: "We printed the drawings as a message to say

that cartoonists cannot be silenced. This was a test of the sincerity

of the prime minister, who says he wants Turkey to be a member of the

EU. Now he has shown his true face." Erdogan said he found the

cartoon "deeply humiliating." The court that threw out one

of his earlier suits commented that "a prime minister who was forced

to serve a jail term for reciting a poem should show more tolerance

to these kinds of criticisms." Erdogan's litigious inclination

fostered fears that the neo-Islamists are bent on stifling the press.

Burak Bekdil, a columnist, wrote: "Perhaps Erdogan has something

against animals. The late premier Adnan Menderes, who was hanged after

the 1960 military coup, was depicted as a belly dancer and he did not

sue. Can there be less free speech in EU-candidate Turkey than in a

semi-democratic Turkey of the 1950s?" Here's a switch: comics inspiring novels rather than novels

being adapted in comics (or comics in movies). Best-selling author Jonathan

Lethem has a three-book contract with Dark Horse to produce novels based

upon Carl Anderson's Henry, Ernie Bushmiller's Nancy, and

Dondi by Gus Edson and Irwin Hansen.

Lethem says his previous protagonists have typically been "conflicted

youth or developmentally arrested adults," so Henry and Nancy and

Dondi fall right in line. Mute Henry's plight is how to convey his deepest

frustrated urges; with Nancy, Lethem says, "I get to investigate

the limits of intelligence ... and the mysterious icon of the Three

Rocks"; and in Dondi, he will explore "the role of missing

parents in the development of a sensitive, artistic soul such as my

own." Working titles for the novels are:

Silent Utterances of Youth, The Thorny Hair of Girlhood, and Alone

with My Lonely Angst. Each will be illustrated- Frank Miller will do Henry, Bill

Griffith (Zippy) the Nancy

book, and Mike Mignola, Dondi.

My source for this startling information is dated April 1, if the novel

titles haven't already given the game away. At a memorial for Will

Eisner in New York on April 7, a who's who of cartooning gathered,

and many spoke of the personal and professional virtues of the man whose

example has guided so much of the profession's effort. "Through

it all," reported Heidi MacDonald, "the connecting thread

was the gift of Eisner's insistence on pushing his own boundaries while

recognizing the talent of others. How could you not feel like a slacker

when an 80-year-old man who had inspired everyone was proclaiming himself

still a beginner and trying to move on to the next thing?" Gary

Sassaman reported on his blog that he learned that Eisner's preferences

about a movie version of his Spirit was for Harlan Ellison to write,

William Friedkin to direct, and James Garner to play the leading role.

Bravo. In the latest issue of Busted, the news magazine of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, Steve Geppi, distributor Diamond's head,

who was recently appointed to the CBLDF Board of Directors, defends

his reputation. I observed here when he was appointed that he seemed

an unlikely champion for freedom of the press because of his earlier

reputation for censoring comics. His censorship, if I recall aright,

involved his refusing to distribute various titles that, for one reason

or another (sexual content, profanity, etc.), offended him. My impression

at the time was that his conservative (religious?) views drove his judgement

to extremes; but I may have that wrong. Still, the question remained:

How can a person who allegedly so willingly imposed his moral and political

views on the distribution system he controlled be a defender of freedom

of expression? Geppi spoke directly to that criticism in remarks addressed

to the Diamond's September Retailer Summit: "Some of you old timers who are probably

extremely shocked right now that I'm up here as a new member of the

Board because for those of you who go back far enough, you know that

I once had the reputation-not a truly valid reputation-but an accused

reputation of being a censor. That was at a time when I thought I was

doing the right thing because I was looking at some of the things that

were being sent out in the mail to us to solicit, and quite frankly

I didn't think the retailers should be exposed to them. And I'm not

talking about violence or sex. I just thought the quality was poor,

and then I got accused of being a censor. But I do very much believe

in free speech and I very much believe in what the CBLDF represents."

Earlier in the evening's agenda, Geppi had referred to the notorious

effects of Frederic Wertham's crusade against comics

in the mid-1950s, saying, in part, that "Wertham later recanted-not

that a lot of people know that." Geppi himself seemed to be recanting:

"Yes," he said, "there are comic books that have violence.

Yes, there are comic books that have sex. Yes, there are comic books

that have nudity. But there are other comic books, too. Like other entertainment

media, whether it be television or movies, comic books are a medium

that entertains. Comic books are in a unique position, and we're fortunate

enough to represent them." And he vowed to do his best to advance

the cause for which the CBLDF was created. Good enough. For now. Elsewhere in the same issue of Busted, CBLDF reports some success in opposing various incipient laws

that, while purporting to protect children, actually deny freedom of

expression. And Peter David reports

on the tattoo he acquired to raise money for the Fund. Wendy Pini drew a picture of one of her Elfquest characters on his

arm with a ballpoint pen, challenging David to get it tattooed. "If

someone will donate a thousand bucks to the fund, I'll have it made

permanent," David quipped. After a few hours of fruitless fund-raising

to get David disfigured permanently, Richard

Pini returned and said WaRP Graphics would donate the money because

it was WaRP's characters (that's "Wendy and Richard

Pini") that were being promoted. So David got branded for

life with a picture of Leetah on his upper left arm. Civilization's Last Outpost Barry Schwartz writes

in the April AARP Bulletin that

the greater the number of choices, the more dissatisfaction results.

The original notion about variety on the store shelves was that choices

underscore freedom: the more choices one has, the greater freedom exists

in making a selection. If there's only one brand of soup on the shelf,

you have no freedom when it comes to soup. By the same token, then,

the more choices we have, the greater our freedom, and since freedom

is one of America's iconic values, a vast array of choices must be good.

And so we have, Schwartz enumerates, 85 types of crackers, 285 types

of cookies, 80 pain relievers, thousands of mutual funds, hundreds of

cell phones, dozens of calling plans-and on and on and on. The variety

of screws, bolts, and nails available in the average hardware store

is so vast that you have to take the item you want to screw, bolt or

nail in with you to make sure what you purchase will fit. Even toilet

paper comes in scores of kinds. Studies have now determined that just

because some choice is good, more choice isn't necessarily better. Sometimes,

the more choices there are, the less likely we are to make any selection

at all. Stymied by the very abundance of possibilities, we refrain altogether

from action. I was watching the PBS News Hour the other night when Zbignieu

Brzezinski (Jimmy Carter's national security advisor) was on, being

interviewed about the Pope, who, by then, had died. Zbig knew the Pope

both before and while he was Pope; both are Poles, and they used to

have conversations, I gather. The interviewer asked if the Communists

in Poland were apprehensive about Karol Wojtyla when he became Pope,

and Zbig told a story that he said illustrated their attitude. Here's

the story: It seems there was a big Communist Party meeting going on

in Krakow while the cardinals in Rome were picking the new Pope in 1978,

and right in the middle of the party secretary's speech, someone burst

into the hall, shouting that Wojtyla had been chosen Pope. The party

secretary was stunned and sat down in mid-sentence. He didn't realize

that the microphone was still on when he leaned over to the assistant

party secretary sitting next to him and said tremulously: "My god,

Wojtyla is Pope! Now we'll have to kiss his ass!" And the assistant

leaned back and said with equal timorousness: "Yes-if he'll let

us." That, said Zbig, illustrates how the Polish Communists felt

about John Paul II. Then and thereafter, I assume. Might be a total

fabrication, of course; but this wouldn't be the first apocryphal event

to be celebrated in Christendom. Comic Strip Watch Celebrities often make

guest appearances in Rob Harrell's

Big Top; this week, Ellen DeGeneres shows

up. ... More than 3,000 people responded to Dave Coverly's challenge to supply a speech in an empty speech balloon

in his March 14 Speed Bump panel.

That day, Coverly depicted a gorilla in a diner apparently declining

the service of a cup of coffee, with a blank speech balloon hovering

over his head, an open invitation for creative souls everywhere to supply

a few pithy bon mots. The best entry, Coverly says,

will appear with an encore of the drawing to be published in late May.

John McCain has

supplied the introduction to the Doonesbury

reprint volume chronicling B.D.'s leg loss, The

Long Road Home: One Step at a Time, scheduled for May release. The

advance and all royalties from the sales of the book will go to the

Fisher House Foundation, which provides "comfort homes" in

the vicinity of major military and veteran's medical centers for the

use of relatives visiting recuperating service personnel. The April 4 installment of Darby Conley's Get Fuzzy was

doctored in various of its venues. Bucky Kat is raving on about the

animals associated with holidays-Christmas turkey, Thanksgiving turkey,

Valentine's Day beaver, Easter bunny. When Satchel, horrified, concludes

that means people eat leprechauns on St. Patrick's Day, Rob calls a

halt-then catches himself: "No-hold on, Valentine's Day what?"

Some papers deleted "beaver" and substituted "marmot."

It's not clear to me, though, whether the editorial adjustment was achieved

at individual newspapers or by Conley's syndicate, seeking to provide

client papers with "alternate" strips. Makes me wonder where

editors let their minds run. EDITOONERY Editoonist Nick Anderson of the Louisville Courier-Journal received the

2004 Pulitzer Prize "for his unusual graphic style that produced

extraordinarily thoughtful and powerful messages." Anderson was stunned

by his selection, given the caliber of the competition. Runners-up were

Garry Trudeau for Doonesbury "for provocative cartoons that used realistic characters

to dramatize social and political issues" and Don Wright (Palm Beach Post) "for his portfolio of wry but hard-hitting

cartoons that addressed a wide range of issues with unflinching honesty."

Trudeau won in 1975 and was nominated again last year. Said Anderson:

"It's an incredible honor. The first person I called was my wife,

and the second person I called was my dad. I'm glad this happened while

he is still around." (His mother died in 1971.) Anderson received

the news from one of his editors, who screamed at him to come to his

office. "I figured I must have done something really good or really

bad," Anderson said. Anderson, 38, joined the Courier-Journal

a month after graduating in 1991 as a political science major from

Ohio State University; in 1995, he became the paper's chief political

cartoonist. Anderson's drawing style combines a spidery line with an

unusual filagree shading technique that imparts to the final art the

quality of a fine etching. An unabashed critic of the Bush League, Anderson

said of his craft: "The rule, I think, is to provoke thought. In

the process of provoking thought, you often provoke anger, and that's

not a bad thing. In fact, it can be a very good thing because that's

the beginning of dialogue. Being funny is fine," he continued,

"but to what end if you're not going to have a point of view?"

Joel Pett, an

unflinching editoonist whose acerbic wit makes him a standup comedian

without peer, whom I (and Editor

& Publisher) listed a couple weeks ago as one of the three finalists,

was, in fact, not one of the trio. Sorry. And E&P

apologizes, too. But Pett, a 2000 Pulitzer winner, deserves to be

among the finalists in any year. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch

has finally hired a political cartoonist, R.J. (Robert John) Matson, who has been drawing a cartoon a week

for the New York Observer and

four cartoons a week for Roll

Call, the congressional newspaper in Washington. The position has

been vacant since late 2003 when John

Sherffius resigned for reasons that were not very well specified

but seemed, to various observers, to have something to do with his political

point of view not coinciding with that of his editors. And he got fed

up with his cartoons being rejected or modifications being suggested.

So he left. An online P-D

article supplies some background on Matson: His cartoons and illustrations

have appeared in numerous publications including

The New Yorker, The Nation, MAD Magazine, The Washington Post and

Rolling Stone. Born in Chicago in 1963,

Matson was raised in Brussels, Belgium, and Minneapolis. His artistic

gifts surfaced early, nudging aside his dreams of being a major league

pitcher or a race car driver. "I was a compulsive doodler,"

Matson said. "Being a cartoonist was the one dream I never outgrew."

In grade school he drew comic strips, which he photocopied and sold

for 25 cents, featuring his classmates. While a student at Columbia

University, his political cartoons and weekly comic strip for the campus

newspaper got enough positive feedback to persuade him that he had a

good shot at going pro. After graduating from Columbia in 1985, he worked

as a reporter, a bartender and a freelance artist. He was 25 before

he was able to scrape by solely on his income from drawing. "I

never would have found the drive and the perseverance to become a cartoonist

if I hadn't convinced myself that I would be a miserable failure as

a lawyer, doctor or an advertising executive," Matson said. "That's

been the secret of my success so far." Matson's taste in humor runs the gamut from the acerbic,

George Carlin, to the absurd, Monty Python. His artistic influences

are equally broad, and include the vitriolic 19th century political

cartoonist Thomas Nast, the whimsical George Herriman (Krazy

Kat) and Walt Kelly (Pogo),

R. Crumb's underground comix, and the popular French children's comic

book series "Asterix." Among contemporary editorial cartoonists,

Pulitzer prize-winners Pat Oliphant and the late Jeff MacNelly are two

Matson favorites. As for his political bent? He enjoys skewering "whoever

is in power," he said. "My biggest thrill will be setting

up shop in the same office that was home to great artists like Daniel

Fitzpatrick, Bill Mauldin, Tom Englehart and John Sherffius," Matson

said. "It's an honor to join a newspaper with such a rich cartoon

tradition." Most of the personages Matson names, I rush to point out,

were somewhat liberal in their leanings, and that, according to rumor,

was the undoing of Sherffius. And on the horizon looms Lee Enterprises,

a newspaper chain that is seeking to add the Pulitzer dailies, fourteen

of them including the P-D, to its holdings, bringing its roster up to

58 dailies in 23 states. Lee's honcho, an enterprising woman with an

ominous last name, Mary Junck, was recently named Publisher of the Year

by E&P, but the chain

has acquired a chorus of carping journalism school critics, who question

its dedication to journalism. It also has its defenders, also among

the academia of journalism schools. I'm scarcely in a position to have

an opinion one way or the other; the point of the digression, then,

is that when an acquisition hovers over any paper, the fate of its opinion-makers

can hang in the balance or dangle on tenterhooks, choose your metaphor. All Of Us Sinners Last weekend, I saw

"Sin City," that nearly exact translation into film of Frank Miller's highly stylized starkly

black-and-white graphic novel rendition of brutality and wickedness

in a town populated almost entirely by tough guys and gorgeous dames.

The most interesting aspect of the graphic novels is the manner in which

they are rendered. Miller drenches the pictures in solid black. It's

almost as if he's setting himself a test-to see how much of the drawing

he can shroud in black and still leave enough to tell the tale. It's

fascinating to see how he plays with light and shadow. Ditto the movie,

which, like the books, is mostly black-and-white, just a little color

here and there for accent. Miller was a co-director, and his cohort

Rob Rodriguez used the graphic novels as storyboards for the movie,

so it's understandable how closely the motion picture follows the books.

The movie led the weekend box office take April 1-3 with $28.1 million,

and sales of the re-issued graphic novels from Dark Horse increased

by 25 percent over the same period. By April 13, ten days later, when

Dan Rather interviewed Rodriguez and Miller as well as one of the movie's

stars, Bruce Willis, on "60 Minutes Wednesday," the box office

take was bumping $50 million, having earned more than its production

cost of about $40 million, an unusually low price tag because such vast

quantities of the footage was created in a computer after the actors

had done their acting in front of a green screen. By any commercial

measure-and that, alas, is often the only measure a capitalist society

offers-"Sin City" is a huge success. Can't quarrel with the

figures. And I don't. Moreover, as a transformation of Miller's fantasy

into celluloid, the movie is an aesthetic triumph. No question. It also

produced among the reviewing class a weekend of the most over-heated

prose I've ever seen-wonderful stuff. Here are a few gems mined from

the reviews that shuddered exquisitely over that weekend: From

Ella Taylor, L.A. Weekly: "Sin City," an exquisitely made, unbearably

faddish movie that will strike joy into the hearts of all who revere

amputation and apocalypse, opens with a swoony love scene culminating

in a murder for the heck of it. From there it moves smartly to the promise

of child molestation and, with the culprit having had both his face

and his balls shot off by Bruce Willis, steams merrily along toward

cannibalism, electrocution and the mounting of severed female heads

on walls. Had enough? If not, then you are in all likelihood an adult

male aging ungracefully, or a pimply youth with a pimply youth's fondness

for comic books about hell on Earth. If you're a woman of any age who

gets off on this stuff, even with its feeble stabs at feminist role

reversals, I throw up my hands. Still, given the current vogue for empty

aesthetics, I'm bracing for the laurels that middle-aged critics suffering

from hipster anxiety will heap on this fusion of comic-book art, Asian

combat anime and digital cinema. ... "Sin City" brings together

three of Miller's tales, in which ambiguous heroes, festering in the

same interstitial cracks of the city as their quarries, take revenge

as a means to redemption from their own failings. ... These three heroic

abstractions (no one in his right mind could call them characters) coalesce

into a gaga knightliness that only a virgin schoolboy could get behind.

... The product of three adolescent imaginations with a Sam Fuller fixation,

brilliant mastery of the toys in their digital sandbox, and next to

no grasp of life, "Sin City's" moral dilemmas are bogus and

engage no emotional response. Unlike the Spider-Man franchise, the movie

has no sense of fun beyond the filmmakers' high-pitched giggles at the

expense of audience stamina. ... Given the burgeoning market for their

work at home and abroad, in all likelihood [Quentin Tarantino] and Rodriguez

and their legion imitators will get better and better at what they do,

while having less and less to say. For those of us who like our movies

to show or tell us something about the way we live, that's both too

much, and not nearly enough. From Roger Moore,

Orlando Sentinel: Frank Miller's

"Sin City" is an episodic thriller about murders, thieves,

hookers, cops and ex-cons, loosely connected stories from his Sin City comic books. ... The hallmarks of Miller noir: expressionistic

jet-black streets of eternal night, unadulterated violence, tough guys,

tough broads and tough talk. ... [Said Miller:] "I look for characters

with an inner darkness to them. That's what makes noir. These stories

aren't noir because there isn't enough light on the set. They're not

just dimly lit movies. There's a darkness at the heart of the heroes,

men with big secrets, something terrible in their past." ... Miller's

other trademarks-his unblinking eye for violence and the sexism that

gives every shapely woman in his comics an excuse to lose her clothes-is

part and parcel of the world that he works in and the audience he commands:

comic-book-reading males. "Comic books are the last bastion of

rampant sexism, a place where women are not only the victims of graphic,

callous violence but are portrayed as enormous-breasted, tiny-waisted

caricatures who think clothes are something other people wear,"

wrote Robert Wilonsky in a widely published New Times screed on the genre a few years

back. Miller flinches at that criticism. He says he makes his women

"strong," and insists that the sexuality of "Sin City"

is like the violence-stylized, a fantasy. "And my fantasy is that,

in Sin City, there are all these women, hookers, who have overthrown

their pimps and who rule their own neighborhood," Miller says.

Strong, tough women, able to hold their own with men in a violent world.

But you can't help but notice that these strong women almost always

have their shirts off. "Hey, I'm a guy," Miller laughs in

protest. "Whaddaya want from me?" There's no debating that

Miller's fantasies, whether on the page or on the screen, sell. FOOTNITS: I understand that on Hugh Hewitt's conservative radio

show, someone said the movie embodied the "culture of death"

that is running rampant in American society. Wonderful. Another cultural

football to kick around. Perhaps the most fascinating of the reviews,

though, was by Slate's film critic, David

Edelstein, who began by saying how often he has often lamented the

amorality and opportunism of the vigilante genre as well as the sadism

and righteous torture on display in movies and tv in the wake of September

11-including the "explosion" of the comic book superhero genre

and other "cookie-cutter action thrillers" that "have

been crafted for a generation weaned on Game Boys" and computerized

special effects that "have taken cinema farther and farther from

the world that human beings actually inhabit." Then he saw "Sin

City" with "the most relentless display or torture and sadism

I've ever encountered in a mainstream movie." Then, the verdict:

"I loved it. Or, to put it another way, I loved it, I loved it,

I loved it. I loved every gorgeous sick disgusting ravishing overbaked

blood-spurting artificial frame of it. A tad hypocritical? Yes. But

sometimes you think, 'Well, I'll just go to hell.'" His point,

eventually, was, I think, that the movie was a movie-making triumph,

a stunning demonstration of what cinematography and editing can do up

there on the Big Screen. In short, he loves it, as he even says, as

"an art object." And that, I suspect, is what most movie critics

are lauding about the movie-its overwhelming achievement as motion picture

artistry. They are surely not celebrating the view of humanity that

it offers. Miller deliberately constructed the scariest most repulsive

ambiance he could imagine, the ultimate indulgence for the fan of noir

crime, and he did it to entertain himself and those of us who can lose

themselves in it for the nonce. He didn't do it in order to create role

models. And here, his art-his entertainment-takes place in motion. Mixed Notes about Graphic Novelz Big box office has

transformed book-length comics from the butt of the joke to the belle

of the ball, sez Erika Gonzalez of the Rocky

Mountain News. "It's hard to pinpoint exactly when graphic

novels made the move from castoff to cool," Gonzalez goes on. "But

publishers say the movie business certainly provided the genre with

more credibility." In this society, that is-"credibility"

equals "big money," the bigger, the more credible. "Ghost

World." "The Road to Perdition"-both movies made from

book-length comics. And then we have all the longjohn legions up on

the Big Screen. The consequences of all this excitement are not unalloyed

benefits. Gonzalez

quotes Dan Clowes: "I think this is bigger

than it's ever been before, but I kind of liked it back when everybody

hated us. There was no pressure. I used to send out my comics and hope

it would be reviewed by the Comics

Buyer's Guide." Clowes is being nostalgic, not analytical.

Seth goes a step further,

or deeper. Working on the next book in his Clyde Fans graphic novel series, Seth, aka Gregory Gallant (an even

phonier sounding name), claims to be somewhat baffled by all the attention

graphic novels are getting. "I'm not sure why it's happened,"

he said in a recent listserve note. "Ten years ago, using comic

books to tell a story was a stupid idea. Now it's a mundane fact. You

don't have to sell it to anyone anymore that you're not just an idiot

for working on this." The demand for product, however, is likely

to result in a surge of hastily produced material. "I think there's

going to be a pile of bad graphic novels in the next couple of years,"

said Seth. The flood of manga that has deluged the shelves in chain

bookstores is emblematic of a financial and marketplace breakthrough

that may not be quite the same as an artistic or cultural achievement.

The number of superior graphic novels that have appeared in the last

couple years is impressive: Jimmy

Corrigan: The Smartest boy on Earth, Blankets, Persepolis, In the Shadow

of No Towers, David Boring, Ghost World, Joe Sacco's reportorial

efforts from Bosnia to Palestine not to mention Maus

and the steady flow of innovative work from Will Eisner. And I'm just

scratching the surface here. But manga are produced out of a different

sensibility-a different culture, of course. They may satisfy the immediate

voracious appetite among publishers for product that can be moved onto

shelves for consumers-particularly young female consumers that the comics

industry has almost never appealed to before. But how many of these

tomes off an alien assembly-line with their wispy artwork and tedious

pacing will, for long, satisfy an American reader? For a time, they

will. For a time, they have. But that time may be passing. In short, the manga boom may be going bust. Publisher's Weekly reports that ADV, a

Houston-based manga publisher, has laid off as many as 40 staff from

its manga division because the marketplace is saturated with the product:

"Anyone can see there's only so much shelf space available [in

bookstores] for manga," said DVD president John Ledford, "-we've

adjusted our schedule to keep pace with the [limited] opportunities."

Just in time, I hope, to clear the beaches for a mounting

tide of domestically produced graphic novels. I don't want to sound

provincial or chauvinistic or ethnocentric, but if the bookstore shelves

are jammed with manga, few bookstore operators will want to risk more

shelf space and capital to stock even more of what they doubtless regard

as the "same thing"-drawn books. Manga have helped enormously

to establish among booksellers the market value of the graphic novel,

and for that, let us be everlastingly grateful. But there are other

breeds of graphic novel just waiting to be born-that is, to find readers

via bookstores. And these works may be more attuned to the American

sensibility. Maybe, in the rush to market, some of this material will

be pure unadulterated dross; but if none of it can find its way into

bookstores, we'll never be able to find the wheat amid the chaff because

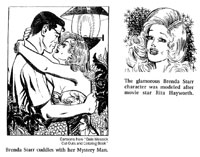

we'll see neither. ONE ADVENTUROUS LADY Dale Messick,

creator of Brenda Starr, arguably

the longest-lived newspaper adventure strip with an eponymous heroine,

died on April 5 just six days shy of her 99th birthday. Her

health had been in a long decline since she suffered a stroke on 1998;

she'd lived in a nursing facility for a time, but she died in the Penngrove,

California, home of her daughter, Starr Rohrman, who had been caring

for her through the last few years. Messick, who changed her first name to avoid being hit on

by male newspaper editors, was a thorough-going professional cartoonist

all her life. In her book The

Great Women Cartoonists, Trina

Robbins called Messick "one of the most seriously committed

and tenacious woman cartoonists of the century. In a 1973 newspaper

interview, Messick describes her pregnancy: 'It was throw up, draw Brenda,

throw up, draw Brenda.'"

The anecdote captures with succinct perfection not only Messick's dauntless

dedication but her irrepressible sense of the ridiculous-about herself

as well as the world around us. Messick was born in Indiana but left as soon as she could

for New York where she worked in greeting cards while conjuring up comic

strip ideas in her spare time. Before Messick came up with Brenda and

went on to become "the grande dame of comics," she tried to

sell four other strips, whose histories (with sample art) Robbins rehearses

in her book- Weegee ("drawn probably when the artist

was just out of high school" and drawn better, I might add, than

many contemporary strips of the mid-1920s) about a country girl coming

to the big city to earn a living (On

Stage anyone?), Mimi the Mermaid

and Peg and Pudy the Strugglettes, which "metamorphosed

into Streamline Babies."

None of them sold. Then in early 1940 she was dating C.D. Batchelor,

the editorial cartoonist at the New

York Daily News, and he told her that the newspaper was going to

launch a new publication, a comic book supplement to the Sunday comics

inspired by the recently invented newsstand comic book, which, by 1940,

was doing a booming business. For this purpose, Batchelor said, the

newspaper needed eight new comic strips. Messick promptly invented a

girl bandit strip and sent it in. By then Dahlia (or "Dalia," as it is usually spelled

these days), knowing that a woman cartoonist would have small chance

of success in the male-dominated world of the time, was signing her

strips with the gender ambiguous "Dale," thinking that most

editors to whom she submitted her work by mail wouldn't suspect she

was female. But Captain Joseph Patterson, publisher of the News

and head of the adjunct Chicago Tribune-New York Daily News Syndicate,

knew Dale was a woman. Messick's characters were undoubtedly the most

frilly-witted heroines in comics, and perhaps for that reason, Patterson

wanted nothing to do with them. Or perhaps the Captain had once before

tried, unsuccessfully, a strip by a woman cartoonist and had vowed never

to make that "mistake" again (although I don't know who that

cartoonist might have been, and it seems unlikely, as you'll see in

a trice, that he was prejudiced against women). In any event, Patterson

didn't like the strip. He might have been guilty of simple male chauvinism.

These days, we're tempted to accuse him of sexism. But anyone hoping

to make that charge stick will have to explain Mary King and Mollie

Slott. King was Patterson's first assistant on the Sunday Tribune, and he made no bones about

her contribution to the paper's success, giving her credit for "at

least half of every good idea I ever had." He eventually married

her. And Slott was Patterson's good right hand on Tribune-News Syndicate

matters. It is doubtful that a rampant sexist would give such power

and responsibility to women. When Slott saw the girl bandit, she saw possibilities, and

she convinced Messick to change the bandit into a newspaper reporter,

a red-headed beauty inspired by Hollywood star Rita Hayworth. For her

heroine's first name, Messick borrowed that of one of the day's glamorous

debutantes, Brenda Frazier, and picked "Starr" because Brenda

would be the "star reporter" of her newspaper, The

Flash, which was named by Slott.

And then, Slott prevailed upon the Captain to buy the strip. He agreed-but only so long as Brenda Starr would never appear in his newspaper, the New York Daily News. And it didn't. Not until after Patterson's death

in 1946. Messick's chronically romantic newspaperwoman first appeared

June 30, 1940, in the Chicago

Tribune's newly launched Sunday Comic

Book Magazine. The cut-out paper dolls that distinguished the Sunday

Brenda for so many years were not yet in

evidence, but in almost every other respect, the early adventures are

vintage Brenda-as Richard Severo says in the

New York Times, "a symphony of decolletage, good legs precariously

balanced on high-heeled shoes, and Dior-like clothing that no woman

would be likely to wear to a newspaper office." No self-respecting

professional journalist, that is. But Messick knew little about the

newspaper business and purposely avoided learning anything, believing

that actual knowledge would corrupt her imagination. And so Brenda Starr

flounced onto the comics page, festooned with fluffy nighties and

lounging pajamas, low-cut (for that day) gowns, and plots governed only

by the whim of Messick's breathless invention, which often ignored logic

and reason in favor of such purely feminine diversions (in the traditional

male chauvinist sense) as a fresh hairdo or a new pair of shoes. Yes,

I know: that sounds sexist. But consider the evidence. On March 30, 1941,

for instance, a doctor speculates that he'll have to amputate Brenda's

legs so badly have her feet been frozen in a Sun Valley winter storm.

The next week, we're still waiting for a verdict on the projected amputation.

But by the following week-happily, Easter Sunday-Brenda has miraculously

recovered so she can waltz down the avenue in her Easter finery. By the end of her first year, Brenda is the fashion plate

she'll be for the rest of her run under Messick, who stopped drawing

the strip in 1980. ("The syndicate pushed me out," she said,

with a sort of bittersweet chuckle, "or otherwise I would have

continued on.") In her first adventure, the redhead is a little

more fiery than she eventually became for the duration, but otherwise,

she lacks only those stars in her eyes to be the Brenda we've always

known (and, yes, loved). At the strip's peak circulation in the fifties,

it was in 250 newspapers-which, for that day, was a goodly number. The

stories are fast-moving adventures. Fast and even a little dizzying.

But that is always part of the pleasure of reading Messick's strip.

The woman with a man's name kept us on the edge of our chairs for forty

years, and you don't do that without being a teller of good, suspenseful

tales, however dizzy they sometimes are. As for Brenda, she was, from

the very start, independent and feisty as well as courageous and resourceful-not

only a suitable protagonist in an adventure story but, as it developed,

a thoroughly admirable role model for ambitious young women who could

find no others of their sex much worth admiring on the comics page.

CNN's Charlayne Hunter-Gault is reported to have said that as a teenager

aspiring to a journalism career, she hoped for the kind of "mystery

and romance" she saw in Brenda's big city newspaper career. Hunter-Gault

is surely not alone. Messick, like any convincing storyteller, lived her character's

life. She dyed her hair to match Brenda's. "I am Brenda Starr,"

she would tell interviewers. "Brenda is the glamorous girl I wished

I was. She's what most women wish they were and what most men wish their

women were, too," she'd add (with a laugh, unless I miss my guess).

"Whenever I hear from real reporters," she went on, "they

would all say their lives weren't as interesting as Brenda's. Who would

have read Brenda if it was real life?" Linda Feldman of the Los

Angeles Times visited Messick in early 1999 and observed that the

cartoonist didn't make small talk: she just said what was on her mind,

even offering unsolicited information. "I was married twice,"

Messick blurted out, "divorced twice, had a bad car accident and

a baby and never missed a deadline in 43 years. I mailed Brenda in before

I saw the baby. I was a terrible mother." "Not true," interrupted Starr, who was born a

year after her namesake's debut. "She was a fine mother, though

my life cerainly wasn't ordinary. I attended seven different schools

before the fifth grade because we traveled in the Brenda Starr rolling

studio-a silver streamer RV outfitted with its own water supply. Mother

was a vagabond who worked seven days a week. She and my father both

loved to travel, and she just had to have adventures. She eventually

would use the adventures in the strip. My father, Everett George, was

her business manager and the draftsman who did the lettering for the

strip." Her mother slipped back into the conversation: "That's

why we got married-we needed each other." Her second husband was

Oscar Strom. Brenda married only once, but it took 36 years to get to

the altar. Her life was forever haunted by her romance with her "mystery

man," Basil St. John, a manikin-beautiful male specimen who wore

an eye patch. He'd show up every so often to take Brenda into his arms.

The redhead would melt in ecstasy-but then, the guy would run off, usually

in pursuit of a rare black orchid from which he could extract a serum

that provided temporary respite from the effects of the exotic disease

he was dying of. Finally, in 1976, the love-lorn pair married. And then

St. John took off again on another wild orchid chase. Messick told Feldman that she rarely watched tv because

she "can't tell when the commercials begin and shows end."

And she never read fiction because she could always predict what's going

to happen next. She did, however, date. In her eighties, she managed

to juggle three boyfriends simultaneously. "All three wouldn't

make one good man," she told an interviewer, "but at my age,

you can't be too choosy," she concluded (probably with a short

laugh). Messick achieved her fame through talent and dedication-not

academic training. She spent two years in the third grade and repeated

that performance in the eighth. I met her only once, in the winter of

1998, when I was visiting Mark Cohen and his wife Rosie in Santa Rosa.

Mark arranged our meeting for dinner one evening, and after dinner,

we drove to Messick's home in a senior residential area. As we pulled

up outside her place, Messick asked if we wanted to come in and see

her "studio." We did, and we did. It was a spare bedroom and

lacked a drawingboard. But there were souvenirs of her years drawing

Brenda Starr all around. She

was still drawing: she took a tiny sketch pad with her to the mall almost

every day, and she sketched the people she saw. She showed me some sketches,

all very confidently executed work. And when I professed admiration

for one of them, she gave it to me (and I've posted it near here with

a self-portrait of the cartoonist as a little old lady). She said she

was working on an autobiography, Still

Stripping at Ninety (never finished), and she was drawing a panel

cartoon for a local newspaper called Granny

Glamor. She harbored, slightly but persistently I believe, some

resentment over the male chauvinism that had infected the profession

all her life. She felt that the National Cartoonists Society had never

quite accepted her-even then, in 1998 as NCS was poised to give her

the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award at its annual meeting that

spring in La Jolla, California. Messick, I think, felt a little more

comfortable with me, a stranger, as the evening wore on, and her talk

was increasingly enlivened by a satirical sense of humor, often self-deprecating,

punctuated, usually, by a short little hoot of laughter. "Ha,"

she might say at the end of a particularly cutting remark. She was,

in short, a delight. And I'm glad to have met her. FOOTNIT: Brenda is now being produced by a writer-artist team, Mary Schmich, a columnist at the Chicago Tribune, and June Brigman. They just completed a sequence

highly critical of the news media's celebrity journalists, whose egos,

in the strip, drive their careers, not their news sense. Written before

the pundit-payola scandals that surfaced with Armstrong Williams' getting

money from the government for promoting the Bush League agenda, the

sequence, which ran in February and March, understandably attracted

more attention than Brenda usually does in the 20 or so newspapers

that now run it. And this is not the first time Brenda has been critical

of the news media, but this time, thanks to the publicity attending

the pundit-payola scams, the strip earned two pages in the April issue

of Editor & Publisher. Said Schmich: "It's

always interesting to me that the way to get noticed by the media is

to write about the media." Interesting-even indicting. SHERLOCK FOREVER Graphic novelists continue

to find inspiration in the fictions of other media. The Irregulars (128 6x9-inch pages in black-and-white paperback, $12.95),

for instance, is taken from the Sherlockian canon of Arthur Conan Doyle.

The Baker Street Irregulars, to employ their full nom de guerre, are a gang of street arabs, orphaned waifs by definition,

who assist Sherlock Holmes occasionally in his detections. As Holmes

puts it in A Study in Scarlet:

"There's more work to be got out of one of these little beggars

than out of a dozen of the [police] force. The mere sight of an official-looking

person seals men's lips. These youngsters, however, go everywhere and

hear everything." In the Holmesian oeuvre, the Irregulars appear

rarely after their introduction in the first adventure, but the romantic

appeal of the notion of a raggedy band of unofficial agents of the "law"

is nearly irresistible. Writers Steven-Elliot

Altman and Michael Reaves,

in any case, were unable to resist it, and they've appropriated the

concept and Conan Doyle's principals for this tale of supernatural horror

and mystification. In addition to Holmes and Doctor John Watson, we encounter

Inspector Lestrade, Miss Irene Adler ("the woman" to Holmes), and Holmes' notorious nemesis, Professor

James Moriarty, the so-called "Napoleon of crime" who once

wrestled with Holmes to his death-Moriarty's, not Holmes'. Fed up with

his creation, Doyle tried to make it appear that Holmes had died so

he would never again have to contend with him and could spend the remainder

of his life writing serious works; but popular demand-and financial

need, I assume-finally prevailed, and Doyle, after almost ten years,

brought his once-dead armchair detective back from the grave, or, more

precisely, from the bottom of Reichenbach Falls, a picturesque cataract

in Switzerland, to which Doyle had brought the foes for a final confrontation

as related in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894). In the popular mind, Moriarty never died either. So compelling

was Doyle's portrait of this master criminal, to whom there are only

a couple of references in the canon, that he has lived on in the minds

of Sherlockians ever after. And he, and a few others of the Undead,

materialize again in this graphic novel. The game gets afoot when we

witness Watson committing a particularly untidy murder with a knife.

Others recognize him, too, so he is quickly arrested and jailed, pending

trial. Holmes summons the Irregulars, and, telling them he must leave

the country on another urgent matter, he gives them the responsibility

of finding out who really did the murder. For the purpose, Altman and

Reaves have recruited a miscellany of cockney urchins and given them

names: Wiggins, their leader; Molly, a clever matchstick girl; Patch,

a pickpocket and escapist; James, an accomplished artist; Puck, a "singular

child" with some sort of second sight; Burke, a protege of Watson's,

and a dog named Toby. Puck, as it turns out, is the most useful in tracking

down the murderer, but he's comforted and encouraged by Molly, who takes

a motherly interest in him, and the indefatigable Wiggins. Moriarty, of course, is behind it all. He's seeking to conquer

the world with the incantation of a cryptic mathematical formula (or

something very like it; it scarcely matters what, exactly, he's up to

since he and his ambition are present simply to get the pot boiling).

As one step towards his objective, Moriarty kidnaps Irene Adler, and

the Irregulars set out in pursuit. They've already interviewed various

witnesses (including a picturesque trollop) to the crime Watson is alleged

to have committed, and now they follow Miss Adler's kidnaper into the

sewers of London, which they find to be inhabited by an awe-inspiring

array of supernatural beings, most of which tower above them in this

nightmarish netherworld of brimstone monsters, shape-changers, and other

demonic vermin. From this point on, the tale assumes the dimensions

of a rousing Hollywood action flick, fraught with special effects of

the exploding and disintegrating sort: the earth trembles, belches smoke

and fire and falls apart in great chunks. How our heroes get out of

all this and rescue Miss Adler and clear Watson's name-that's the rest

of the story, which is best discovered in the pages of The Irregulars. Picturing all of this, from the foggy London streets to

the collapsing castles of the underground, is Angelo Ty "Bong" Dazo, an illustrator and graphic designer

who lives in Bulacan, a remote province of the Philippines. Dazo's work

is typical of Filipino artistry. Many of his cohorts have, over the

years, illustrated comic books and graphic novels for American publishers,

and their achievement is distinguished by copious detail, virtuoso draftsmanship,

and elegant brushwork. Dazo is no exception. His patchy deployment of

black shadow and feathering is sometimes distracting, but his line is

confident and bold as well as supple and sinuous where necessary. Among

his most affecting visual maneuvers-drawing characters walking off into

the fog, disappearing as they go. Page layouts and breakdowns are imaginative

and varied. Many pages are dominated by one large picture, with smaller

panels elaborating the ambiance and advancing the narrative. The pacing

is ingenious, controlled by layout as well as breakdowns, and the visuals

are highly atmospheric-from the teeming street scenes in London to the

steaming netherworld beneath. I suspect the first publication of these

pictures was on pages somewhat larger than we have here, but even at

this reduced dimension, the performance is impressive and a pleasure

to behold. In a well-done graphic novel, the pictures are the story,

as I've said before-and nowhere is that more evident than here. Under the Spreading Punditry The Bush League has

no shame. The Pope dies-one of the most majestic and beloved world figures-and

GeeDubya can't resist hooking his little neoconservative wagon to a

star. He trots right out with one of his many transparently self-serving

attempts to recruit new followers-Catholics this time-by praising the

Pope for championing "the culture of life," hoping, I suppose,

that everyone will believe the phrase originated with Bush. In fact,

however, John Paul II had introduced the expression to describe the

Church's opposition to abortion, contraception, and euthanasia, but

the Bushies mean something quite different when they invoke the "culture

of life": having appropriated the Pope's phrase, they now usurp

its meaning, attempting, by association, to make it apply to anti-stem

cell research, anti-AIDS aid, pro-torture, pro-death penalty, and so

on-the rest of the right-wing nut agenda. All of which, by exaggerating

association, fosters "a culture of life"-in much the same

way as killing terrorists fosters life among the terrorists' foes. But

the Pope, who opposed war (in Iraq or anywhere else) and the death penalty,

meant the expression to stand for something considerably more life-affirming

than isolated, special-interest appeal political causes. Stealing the

Pope's words was Bush's insidious attempt to bring the Pope in line

with Evangelical fundamentalist doctrine so the Republican "base"

could claim the Pontiff as one of theirs, and, by insinuation, the entire

Catholic population of the U.S. voting public. What a hideous slight

of hand. The British have a word for linguistic manipulation of this

sort: dogwhistle politics. By which they mean utterances that most people

don't even hear because they seem entirely vacuous; but the in-group

elite hears exactly what the speaker intends, and they recognize it

as embracing and extolling "their" beliefs. GeeDubya and his

gang effectively used the Pope's happy phrase to promote ideas the Holy

Father abhored. And now George W. ("Whopper") Bush is at it

again, this time hoping people see him and the Pope in a nimbus of celestial

accord when, in fact, their relationship was not quite so perfect. As

I say, they have no shame. I liked what Anna Quindlen wrote about the "culture

of life" in Newsweek

(April 4): "Arguments about Terri's case centered on something

described as a 'culture of life.' It is an empty suit of a phrase, absent

an individual to give it shape. There is no culture of life. There is

the culture of your life, and the culture of mine. There is what each

of us considers bearable, and what we will not bear. There are those

of us who believe that under certain conditions, the cruelest thing

you can do to people you love is to force them to live. There are those

of us who define living not by whether the heart beats and the lungs

lift but whether the spirit is there, whether the music box plays."

Let the band play on. And, yes, there's always a band. Former House Republican leader Dick Armey, now a lobbyist

in Washington, is co-chair of FreedomWorks, which is about to launch

a massive "disinformation" campaign, says AARP, the objective

of which is to paint AARP as "a tool of left-wing ideologues"

who want to turn America into a "socialist, welfare state"

because they object to GeeDubya's plan to dismantle Social Security,

beginning by establishing "personal" accounts. Disinformation

indeed: so what's new about that in the Bush League? If they follow

Karl Rove's strategy in such matters, they'll doubtless accuse the entire

membership of AARP of being homosexual thereby discrediting whatever

the organization says. Well, it worked in Texas with Ann Richards, in

South Carolina with John McCain, and in the midwest during the contest

with John Kerry. Why not? Metaphors be with you. Sigh.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |